Abstract

Phase equilibrium calculations are crucial in chemical engineering design and optimization processes. The PC-SAFT equation of state (EoS) can precisely calculate phase equilibrium, but is relatively complex and computationally intensive. Surrogate models are mathematically simple models that map or regress the input–output relationships of more complex, computationally demanding models. This work employs XGBoost and a hybrid XGBoost-artificial neural networks (XGBoost-ANN) model as surrogate models to replace PC-SAFT EoS calculations for the vapor–liquid equilibrium (VLE) of binary associating systems. This work investigates the VLE of five binary associating systems using data generated by the PC-SAFT EoS. The surrogate models take temperature, pressure, liquid phase mole fractions, and the PC-SAFT parameters for binary associating systems as inputs, and predict the vapor phase mole fractions. Both surrogate models significantly reduce the computational time for calculating VLE data compared to the PC-SAFT EoS, while achieving good prediction results.

1. Introduction

The accuracy of phase equilibrium calculations using equations of state (EoS) is crucial for designing and optimizing processes in the process industries. Gross and Sadowski [1] proposed the perturbed-chain statistical associating fluid theory (PC-SAFT), which accurately predicts the phase equilibrium distribution of substances. However, the mathematical formulation of PC-SAFT is significantly more complex than that of the cubic EoSs commonly used in petrochemical processes, such as Soave–Redlich–Kwong (SRK) [2] and Peng–Robinson (PR) [3].

Surrogate models are mathematically simplified representations that map or regress the input–output relationships of more complex, computationally intensive models [4]. Surrogate models can be evaluated more rapidly than rigorous thermodynamic models, yielding a simplified thermodynamic model; however, this approach is applicable only within a limited physical range [5]. In process engineering, surrogate models are widely employed to simplify EoSs and predict thermodynamic parameters [6,7,8,9]. Sun et al. [10] employed graph neural networks (GNNs) to predict vapor–liquid phase equilibrium in binary mixtures (e.g., acid + water, water + ethylene glycol), achieving predictive performance comparable to that of NRTL and Wilson with their developed surrogate model. Ihunde and Olorode [11] employed Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINN), which are neural networks trained to solve supervised learning tasks while adhering to physical constraints described by general nonlinear partial differential equations [12], and standard deep learning models as surrogate models for the PR EoS, to predict the flash of the methane–propane–tetradecane system. They found that the PINN model achieved a root mean square error (RMSE) approximately two times lower than the standard deep learning model. Recent advances in PINN have largely focused on overcoming the loss-imbalance problem through sophisticated self-adaptive weighting strategies, such as maximum-likelihood-based Gaussian modelling of individual loss terms [13], dynamic minimax-trained weights that act as learnable attention-like masks [14], and the deliberate use of radial basis function activations to faithfully represent nonlocal integral operators in inverse problems [15]. These techniques have dramatically improved convergence, accuracy, and physical consistency for challenging equations, including Navier–Stokes, Allen–Cahn, and peridynamic models. Hakim et al. [16] investigated the liquid–liquid equilibrium of ternary systems composed of aliphatic compounds + aromatic compounds + ionic liquids using a hybrid artificial neural network (ANN) approach that combined backpropagation (BP) and the Group Method of Data Handling (GMDH). The data obtained from the trained neural network were compared with the calculated values from the NRTL and UNIQUAC. The results indicated that the predictions from the BP neural network were more accurate. Despite the promising results achieved by neural networks or machine learning methods in phase equilibrium calculations, most existing studies on surrogate models for phase equilibrium have primarily employed cubic EoSs and activity coefficient models [8,17,18,19,20,21,22], with relatively fewer investigations into SAFT-type EoSs.

Tree boosting is a widely applied and highly effective machine learning method. XGBoost is a scalable machine learning system for tree boosting, frequently integrated with neural networks [23]. In XGBoost, a novel sparsity-aware algorithm is employed to handle sparse data, and a built-in weighted quantile sketch is utilized for approximate learning. These algorithmic improvements have enabled its widespread adoption by data scientists. Despite the growing number of machine learning-based surrogate models for vapour–liquid equilibrium calculations, the vast majority of reported studies have focused on activity coefficient models (NRTL, UNIQUAC, etc.) and cubic EoS. Applications to advanced molecular-based equations such as SAFT-family models remain extremely scarce, primarily because of their considerably higher computational cost and complex residual thermodynamics. The present work fills this gap by developing highly efficient XGBoost- and XGBoost-ANN-based surrogate models trained exclusively on PC-SAFT calculated data. This work investigated the isotherm VLE of five binary associating systems (water + methanol, water + ethanol, water + 1-propanol, water + 2-propanol, and water + 1-butanol) using XGBoost and a hybrid XGBoost-ANN approach (hereafter referred to as XGBoost-ANN). Surrogate models were developed with temperature (T), pressure (P), the mole fraction of the liquid phase (), and the PC-SAFT parameters for binary associating systems (, , , , , , ) as inputs, and the mole fraction of the vapor phase as the output. The output is represented by . The data used for training and testing the PC-SAFT surrogate models were calculated using PC-SAFT and verified for thermodynamic consistency (comprising a total of 265 data points). Additional details regarding the data are provided in the Supplementary Materials. Furthermore, this work imposed the physical constraint that the output values should lie within the range [0, 1] and customized a loss function for the neural network training in XGBoost-ANN to incorporate this constraint.

2. Method

2.1. PC-SAFT

For the thermodynamic phase equilibrium of two phases (I and II),

In Equations (1) and (2), is the number of components, represents the chemical potential of component i, and denotes the fugacity of the i component. The phase equilibrium relationship expressed in terms of fugacity coefficients is given by

In Equation (3), is the fugacity coefficient of component i. For the binary associating systems investigated in this work, the residual Helmholtz energy () of the PC-SAFT EoS [1] can be expressed as

In Equation (4), represents the hard-chain reference contribution, is the dispersion contribution. denotes the association contribution.

In the PC-SAFT EoS, the fugacity coefficient is expressed as

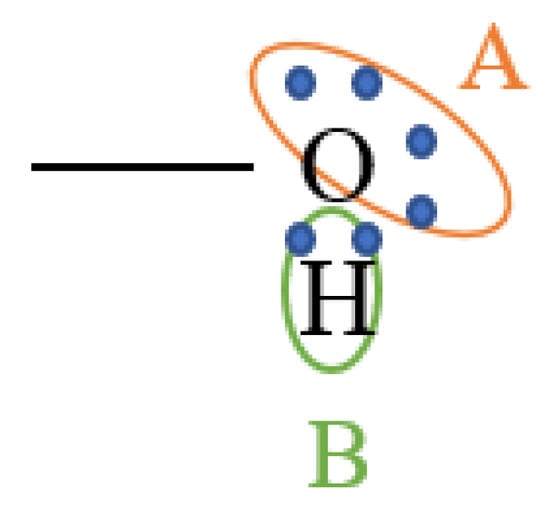

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the 2B association scheme for water and alcohols.

2.2. XGBoost

2.2.1. Tree Ensemble Model

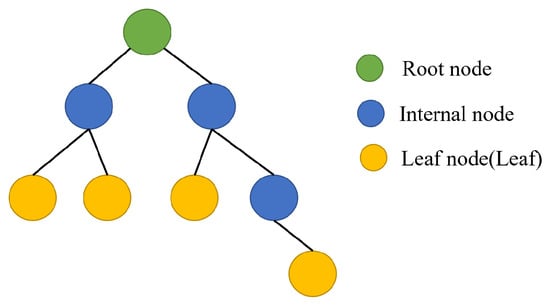

For regression problems, each regression tree assigns a continuous score to every leaf, with representing by the score associated with the ith leaf. The tree structure is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Tree structure.

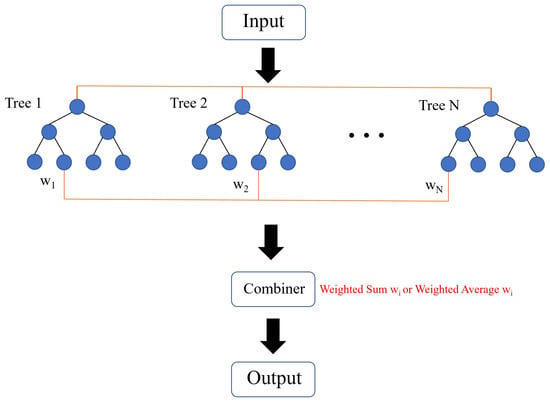

Figure 3 illustrates the flowchart of the tree ensemble model for regression problems. Initially, training data are input into each tree. The regression trees then assign the corresponding wi values to the combiner. The combiner performs a weighted sum or average of the wi values to produce the final output. The regularized objective function of the tree ensemble model is defined as

where

In Equation (8), and represent the true and predicted values, respectively. is the differentiable convex loss function quantifies the discrepancy between the and . is used to penalize the complexity of the tree ensemble model. In Equation (9), LeavesN is the number of leaves in the tree. and are penalization parameters.

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of the tree ensemble model.

2.2.2. Gradient Tree Boosting

The objective function in Equation (8) cannot be optimized using traditional optimization approaches in Euclidean space. In XGBoost, an iterative objective function based on Equation (8) is employed.

In Equation (10), is the predicted value of the ith instance at the tth iteration. represents an additional perturbation function introduced. To facilitate rapid optimization of the objective function, a second-order approximation is applied to the first term in Equation (10).

where

By further simplifying the constant term , the simplified objective function in XGBoost can be obtained.

If is set to , is the instance set of leaf j, Equation (14) can be rewritten as

replace in Equation (15) with

Hence, Equation (15) can be rewritten as

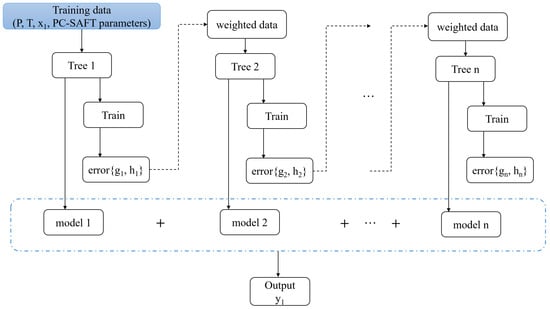

The schematic diagram of the XGBoost algorithm is presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of XGBoost in this work. The PC-SAFT parameters include , , , , , , .

2.3. Artificial Neural Networks

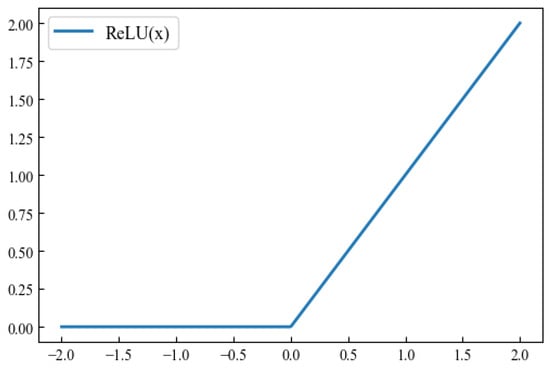

In this work, we constructed a custom loss function utilizing the ReLU function to address the scenario where the training data exceeds the physical constraint range of [0, 1]. The mathematical expression of the ReLU function is presented in Equation (18), while Figure 5 illustrates the graphical representation of the ReLU function.

Figure 5.

ReLU function.

In this work, the custom loss function is called ConstrainedMSE,

In Equation (19), N is the number of experimental data. represents the penalty weight. MSE is the mean squared error,

In this work, the ANN was constructed using PyTorch [26], with the Adam optimizer employed and a learning rate set at . L2 regularization was implemented with a weight decay coefficient of .

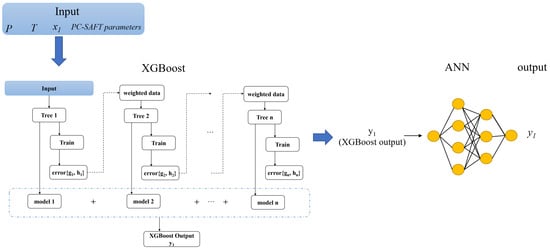

2.4. XGBoost-ANN

The other surrogate model in this work is XGBoost-ANN. The XGBoost-ANN first trains the input data (T, P, , PC-SAFT parameters) using XGBoost, and then employs the output from XGBoost as the input for ANN training to obtain the predicted values (). The algorithmic schematic of XGBoost-ANN is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram of XGBoost-ANN. The PC-SAFT parameters include , , , , , , .

Integrating ANN with ConstrainedMSE into XGBoost in the XGBoost-ANN ensures that the final trained results adhere to the physically constrained range of [0, 1]. Alternative and potentially more principled approaches to enforce the [0, 1] bounds include employing a sigmoid activation at the output layer or predicting logit-transformed targets. These strategies, which eliminate the need for an explicit penalty hyperparameter , will be systematically investigated in our future work.

2.5. Thermodynamic Consistency

Thermodynamic data measured under identical conditions may vary among different researchers. Conducting thermodynamic consistency tests on experimental values is essential [27]. At constant temperature, the Gibbs–Duhem equation for a binary system can be expressed as [28]

In Equation (21), represents the reduced molar volume, denotes the activity coefficient of component i, is the ideal gas constant, and is the mole fraction of component i. This work employed the PC-SAFT EoS to calculate VLE using the approach, and Equation (21) can be rewritten as [29,30]

In this work, we employed the integral form of Equation (22) to conduct thermodynamic consistency tests on isothermal vapor–liquid equilibrium data [27,31].

In Equation (23), the left-hand side term P represents the experimentally measured system pressure, and denotes the experimentally determined vapor-phase mole fraction. On the right-hand side, , Z and are calculated using the PC-SAFT EoS. The basis for deciding thermodynamic consistency is [27,31]

where

The Supplementary Materials provides additional details on the thermodynamic consistency tests.

3. Results and Discussion

This work optimized the hyperparameters n_estimators, max_depth, learning_rate, subsample, colsample_bytree, colsample_bylevel, colsample_bynode, reg_alpha, reg_lambda, min_child_weight, gamma, and max_delta_step of XGBoost using the randomized grid search method from the scikit-learn library [32]. The hyperparameter optimization range for XGBoost is presented in Table 1. Table 2 presents the optimized parameter values obtained through random grid search in this work. Moreover, the neural network architecture of the ANN was optimized using Optuna [33]. A detailed introduction to the Optuna library is provided in the Supplementary Materials. The optimization ranges were set as the number of neural network layers within [1, 5], the number of neurons per layer within [4, 64], with an optimization step size of 4, and the penalty weight within [1, 10,000]. The batch size was selected from the set {16, 32, 64, 128}. The hyperparameters of XGBoost in the XGBoost-ANN framework were adopted from the previously optimized XGBoost hyperparameters, while the optimized parameters for the ANN are presented in Table 3. We utilized thermodynamic consistency data from five binary mixture systems (water + methanol, water + ethanol, water + 1-propanol, water + 2-propanol, and water + 1-butanol) for training the XGBoost and XGBoost-ANN surrogate models. The complete dataset consists of 265 data points. To prevent data leakage and ensure fair evaluation across different binary systems, the dataset was split in a system-stratified manner. For each of the five binary associating systems, 80% of the data points were randomly selected for training (total: 212 points), and the remaining 20% were reserved as the test set (total: 53 points). This stratified splitting guarantees that both training and test sets contain data from all five binary systems in equal proportion.

Table 1.

Hyperparameter range for XGBoost optimization in this work.

Table 2.

The optimized parameters for XGBoost in this work.

Table 3.

The optimized parameters for ANN in this work.

Details of the data used for training and validating the surrogate model are provided in Table S3 of the Supplementary Materials. The binary interaction parameters were regressed based on the PC-SAFT EoS, and the average absolute percentage deviation (%AAD) is presented in Tables S4–S8 of the Supplementary Materials. The loss function for the ANN training set is presented in Figure S1 of the Supplementary Materials.

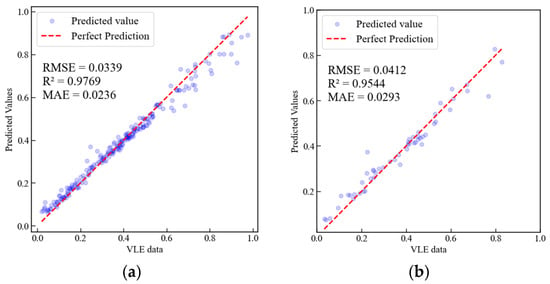

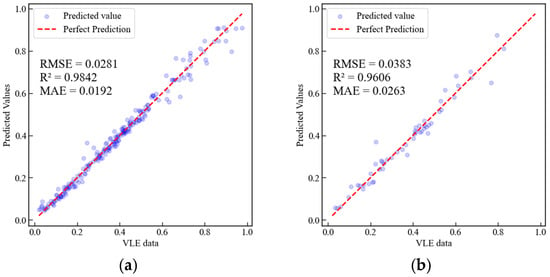

A comparison of Figure 7 and Figure 8 reveals that the surrogate model based on XGBoost-ANN outperforms the XGBoost surrogate model in terms of , RMSE, and MAE (Mean Absolute Error) for both the training and test sets. Additionally, we compared the computational time required to process all data points (265 points) using PC-SAFT, the surrogate model based on XGBoost, and the surrogate model based on XGBoost-ANN, with specific timings presented in Table 4. The computer configuration used for testing computational speed is detailed in Table S9 of the Supplementary Materials. As shown in Table 4, the computational time of the surrogate models is significantly reduced compared to that of the PC-SAFT EoS. The final computational time was determined by averaging the results of three independent measurements. The surrogate model based on XGBoost achieves a computational time reduction of 2918.5 times, while the surrogate model based on XGBoost-ANN achieves a computational time reduction of 973 times.

Figure 7.

Comparison of predicted values from the surrogate model based on XGBoost with VLE data calculated using PC-SAFT. (a) Training set, (b) Test set.

Figure 8.

Comparison of predicted values from the surrogate model based on XGBoost-ANN with VLE data calculated using PC-SAFT. (a) Training set, (b) Test set.

Table 4.

Computational time required for processing all data points using PC-SAFT, the surrogate model based on XGBoost, and the surrogate model based on XGBoost-ANN.

3.1. Water + Methanol

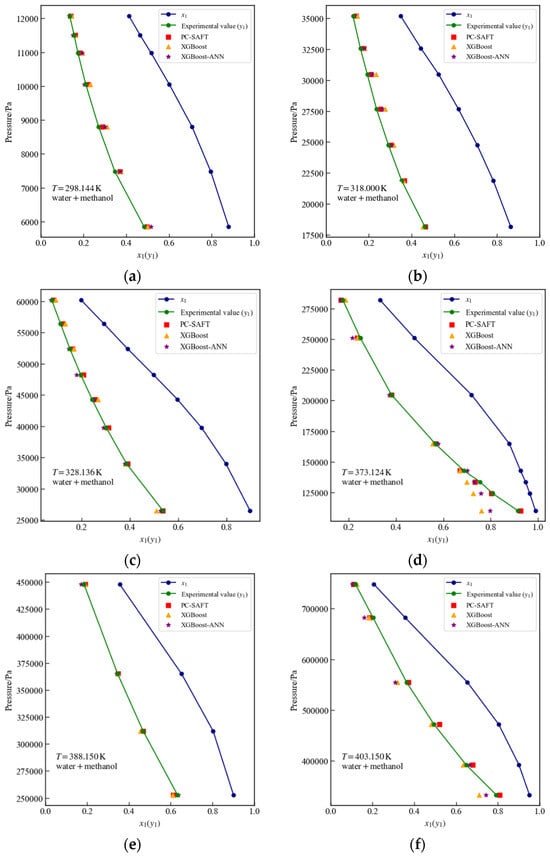

Figure 9 presents the experimental values (), PC-SAFT calculated values, and surrogate model predictions at temperatures of 298.144 K, 318 K, 328.126 K, 373.124 K, 388.150 K, and 403.15 K for the water + methanol system. As observed in Figure 9d,f, when the liquid-phase mole fraction () exceeds 0.7, the predictions of the surrogate model based on XGBoost and the surrogate model based on XGBoost-ANN are lower than the PC-SAFT calculated values, with the surrogate model based on XGBoost-ANN predictions being closer to the PC-SAFT values. Table 5 presents the and MSE values for the surrogate model and PC-SAFT calculated values at the temperatures shown in Figure 9. From Table 5, it can be observed that only at temperatures of 298.144 K, 328.136 K, and 388.150 K does the surrogate model based on XGBoost slightly outperform the surrogate model based on XGBoost-ANN, while at all other temperatures, the surrogate model based on XGBoost-ANN yields superior prediction results compared to XGBoost. Table 6 reports the %AAD achieved with PC-SAFT and with the surrogate model, respectively. The is the absolute deviation between the %AAD of the PC-SAFT calculations and the %AAD of the surrogate model predictions. It is evident from Table 6 that the for all systems displayed in Figure 9 remains below 5%.

Figure 9.

Vapor–liquid equilibrium data for the water + methanol system at different temperatures: comparison of PC-SAFT calculated values with predictions from XGBoost and XGBoost-ANN surrogate models. (a) 298.144 K, (b) 318 K, (c) 328.126 K, (d) 373.124 K, (e) 388.15 K, (f) 403.15 K.

Table 5.

Comparison of surrogate models and PC-SAFT calculated values at different temperatures for the water + methanol system.

Table 6.

The %AAD values of the PC-SAFT calculations and those of the surrogate models in Figure 9.

3.2. Water + Ethanol

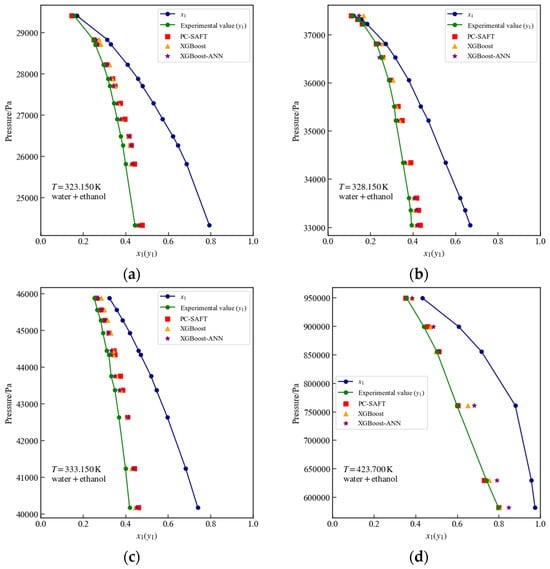

Figure 10 illustrates the liquid-phase mole fraction (), experimental values (), PC-SAFT calculated values, and surrogate models’ predictions at temperatures of 323.15 K, 328.15 K, 333.15 K, and 423.7 K. As observed in Figure 10d, the surrogate model based on XGBoost-ANN exhibits larger prediction deviations for three points where lies within the range [0.6, 0.8]. Table 7 indicates that at 423.7 K, the surrogate model based on XGBoost provides more accurate predictions, whereas at the other temperatures, the surrogate model based on XGBoost-ANN predictions is closer to the PC-SAFT calculated values. Table 8 indicates that all values associated with Figure 10 remain below 4%, with the only exception being the surrogate model based on XGBoost-ANN at 423.7 K, which shows substantially greater discrepancies relative to PC-SAFT and experimental data.

Figure 10.

Vapor–Liquid equilibrium data for the water + ethanol system at different temperatures: comparison of PC-SAFT calculated values with predictions from XGBoost and XGBoost-ANN surrogate models. (a) 323.15 K, (b) 328.15 K, (c) 333.15 K, (d) 423.7 K.

Table 7.

Comparison of surrogate models and PC-SAFT calculated values at different temperatures for the water + ethanol system.

Table 8.

The %AAD values of the PC-SAFT calculations and those of the surrogate models in Figure 10.

3.3. Water + 1-Propanol

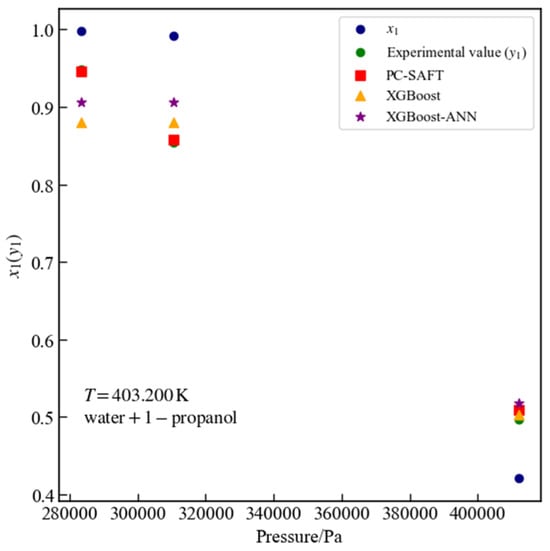

Figure 11 presents three data points for the water + 1-propanol system at a temperature of 403.2 K that passed thermodynamic consistency tests. For these points, the surrogate model based on XGBoost yields an MSE of 0.0016 and an of 0.9547, while the surrogate model based on XGBoost-ANN yields an MSE of 0.0013 and an of 0.9627. For all experimental data points of the water + 1-propanol system, the surrogate model based on XGBoost achieves an MSE of 0.0016 and an of 0.9482, whereas the surrogate model based on XGBoost-ANN achieves an MSE of 0.0012 and an of 0.9586. For the water + 1-propanol binary system across all data points, the %AAD values are 4.3023% for PC-SAFT, 4.9932% for the surrogate model based on XGBoost, and 5.1969% for the surrogate model based on XGBoost-ANN, respectively.

Figure 11.

Vapor–liquid equilibrium data for the water + 1-propanol system at 403.2 K: comparison of PC-SAFT calculated values with predictions from XGBoost and XGBoost-ANN surrogate models.

3.4. Water + 2-Propanol

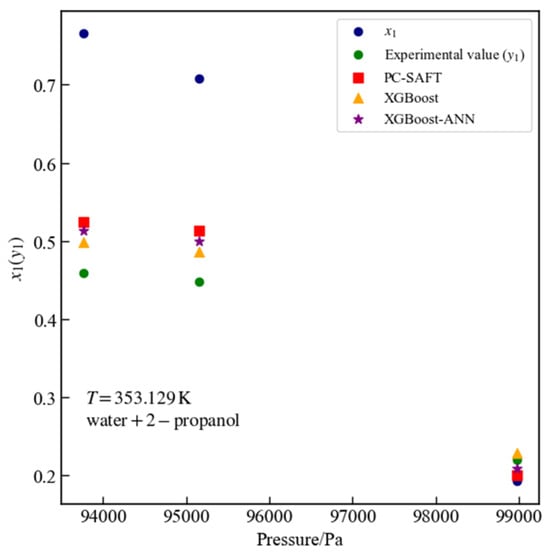

Figure 12 presents three data points for the water + 2-propanol system at a temperature of 353.129 K that passed thermodynamic consistency tests. For these points, the surrogate model based on XGBoost yields an MSE of 0.0007 and an of 0.9669, while the surrogate model based on XGBoost-ANN yields an MSE of 0.0001 and an of 0.9943. For all experimental data points of the water + 2-propanol system, the surrogate model based on XGBoost achieves an MSE of 0.0027 and an of 0.8778, whereas the surrogate model based on XGBoost-ANN achieves an MSE of 0.0025 and an of 0.8865. For the water + 2-propanol binary system across all data points, the %AAD values are 11.7714% for PC-SAFT, 13.2330% for the surrogate model based on XGBoost, and 14.8303% for the surrogate model based on XGBoost-ANN, respectively. Both PC-SAFT and the surrogate models show considerably larger deviations for the VLE experimental data of the water + 2-propanol system.

Figure 12.

Vapor–Liquid equilibrium data for the water + 2-propanol system at 353.129 K: comparison of PC-SAFT calculated values with predictions from XGBoost and XGBoost-ANN surrogate models.

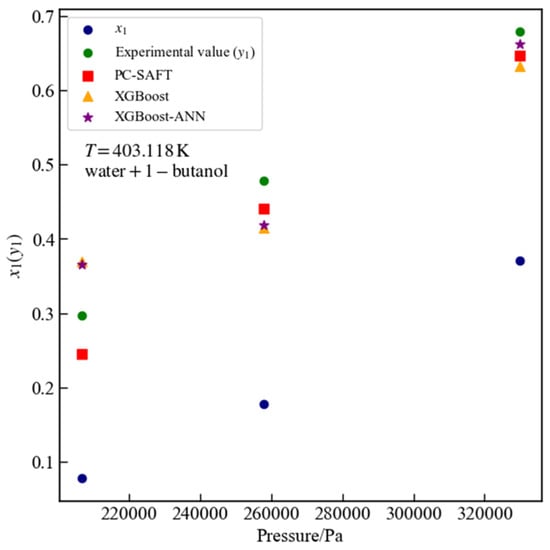

3.5. Water + 1-Butanol

Figure 13 presents three data points for the water + 1-butanol system at a temperature of 403.118 K that passed thermodynamic consistency tests. For these points, the surrogate model based on XGBoost yields an MSE of 0.0055 and an of 0.7970, while the surrogate model based on XGBoost-ANN yields an MSE of 0.0051 and an of 0.8098. For all experimental data points of the water + 1-butanol system, the surrogate model based on XGBoost achieves an MSE of 0.0057 and an of 0.8670, whereas the surrogate model based on XGBoost-ANN achieves an MSE of 0.0040 and an of 0.9071. For all data of the water + 1-butanol system, the predictions of the surrogate model based on XGBoost-ANN are significantly closer to the PC-SAFT calculated values. For the water + 1-butanol binary system across all data points, the %AAD values are 7.1175% for PC-SAFT, 11.6284% for the surrogate model based on XGBoost, and 9.7374% for the surrogate model based on XGBoost-ANN, respectively.

Figure 13.

Vapor–liquid equilibrium data for the water + 1-butanol system at 403.118 K: comparison of PC-SAFT calculated values with predictions from XGBoost and XGBoost-ANN surrogate models.

The present study is restricted to binary mixtures. Validation on multicomponent and reactive systems, which is essential for real industrial applications, remains to be conducted and is highlighted as the most important direction for future work. Another important limitation of the current work is the absence of uncertainty quantification. In future work, we will conduct a more comprehensive investigation of PC-SAFT surrogate models by incorporating a broader range of machine learning algorithms as well as uncertainty quantification and analysis. The surrogate models presented in this paper are trained and validated on only five binary associating systems. Defining the precise domain of applicability and safe extrapolation boundaries of the proposed framework will therefore constitute a major focus of our future work, in which a significantly larger and more diverse set of binary and multicomponent systems will be incorporated.

4. Conclusions

This work constructed surrogate models for the VLE of the water + methanol, water + ethanol, water + 1-popanol, water + 2-propanol, and water + 1-butanol binary systems using XGBoost and XGBoost-ANN methods. The models were optimized using randomized grid search and the Optuna library. Both surrogate models significantly reduce the computational time for calculating VLE data compared to the PC-SAFT EoS, while achieving good prediction results. Among the systems investigated, the water + 2-propanol and water + 1-butanol binary mixtures exhibit the largest deviations for both PC-SAFT and all surrogate models. These two systems possess only limited thermodynamically consistent experimental VLE data points 13 for water + 2-propanol and 14 for water + 1-butanol after application of rigorous thermodynamic consistency tests. Even when the binary interaction parameters kij of PC-SAFT were regressed against these experimental data, substantial deviations from the measurements persist. Consequently, the relatively poor performance of the surrogate models for these two systems is largely attributable to the scarcity or questionable quality of the underlying experimental database. Improved predictive accuracy of the surrogate models is expected in the future once more reliable and extensive VLE measurements become available for these two challenging binary systems.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/pr13123918/s1. The supplementary materials are in the supplementary_material.docx [34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65]. The raw data is available at: https://github.com/ywpang-ren/XGb_pang_paper/tree/main/paper_data (accessed on 26 November 2025).

Author Contributions

Y.P.: Conceptualization, Data Curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing—original draft. Z.D.: Data Curation, Writing—review and editing, Resource. Q.L.: Writing—review and editing, Resource. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is in part supported by the Research Fund from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2022YFC2106300). The APC was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no competing financial interests.

Nomenclature

| %AAD | average absolute percentage deviation |

| the association contribution term | |

| the dispersion contribution term | |

| the hard-chain reference contribution term | |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| Ap | pressure integral term |

| the integral of the fugacity coefficient | |

| the residual Helmholtz energy | |

| EoS | Equation of State |

| ft | additional perturbation function |

| the fugacity of the component i | |

| kB | Boltzmann constant |

| kij | binary interaction parameters |

| L | the objective function of XGBoost |

| LeavesN | the number of leaves in the tree |

| MAE | mean absolute error |

| mi | the number of segments |

| MSE | mean square error |

| NAi, NBi | the number of association sites |

| nc | the number of components |

| P | pressure |

| PINN | Physics-Informed Neural Network |

| RMSE | root mean square error |

| T | temperature |

| VE | reduced molar volume |

| VLE | vapor–liquid equilibrium |

| wi | the score associated with the ith leaf |

| yi | true value |

| predict value | |

| Z | compression factor |

| segment dimeter | |

| depth of pair potential, K | |

| associative volume | |

| associative energy | |

| penalty weight | |

| the residual chemical potential | |

| the chemical potential of component i | |

| the fugacity coefficient of the component i | |

| packing fraction | |

| penalize function | |

| penalization parameters | |

| activity coefficient of component i |

References

- Gross, J.; Sadowski, G. Perturbed-Chain SAFT: An Equation of State Based on a Perturbation Theory for Chain Molecules. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2001, 40, 1244–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soave, G. Equilibrium constants from a modified Redlich-Kwong equation of state. Chem. Eng. Sci. 1972, 27, 1197–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, D.; Robinson, D.B. A rigorous method for predicting the critical properties of multicomponent systems from an equation of state. AIChE J. 1977, 23, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBride, K.; Sundmacher, K. Overview of Surrogate Modeling in Chemical Process Engineering. Chem. Ing. Tech. 2019, 91, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winz, J.; Engell, S. Data-efficient surrogate modeling of thermodynamic equilibria using Sobolev training, data augmentation and adaptive sampling. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2024, 299, 120461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rittig, J.G. Gibbs–Duhem-informed neural networks for binary activity coefficient prediction. Digit. Discov. 2023, 2, 1752–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, T.; Sun, S.; Gao, X. Accelerating flash calculation through deep learning methods. J. Comput. Phys. 2019, 394, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottaiano, G.Y.; Martins, T.D. Machine learning models for vapor-liquid equilibrium of binary mixtures: State of the art and future opportunities. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2024, 211, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Sobecki, N.; Ding, D.; Zhu, L.; Wu, Y.-S. Accelerating and stabilizing the vapor-liquid equilibrium (VLE) calculation in compositional simulation of unconventional reservoirs using deep learning based flash calculation. Fuel 2019, 253, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Xue, J.; Yang, G.; Li, J.; Zhang, W. Vapor–liquid phase equilibrium prediction for mixtures of binary systems using graph neural networks. AIChE J. 2025, 71, e18637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihunde, T.A.; Olorode, O. Application of physics-informed neural networks to compositional modeling. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2022, 211, 110175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raissi, M.; Perdikaris, P.; Karniadakis, G.E. Physics-informed neural networks: A deep learning framework for solving forward and inverse problems involving nonlinear partial differential equations. J. Comput. Phys. 2019, 378, 686–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Z.; Peng, W.; Liu, X.; Yao, W. Self-adaptive loss balanced Physics-informed neural networks. Neurocomputing 2022, 496, 11–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Feng, X. Dynamic Weight Strategy of Physics-Informed Neural Networks for the 2D Navier–Stokes Equations. Entropy 2022, 24, 1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Difonzo, F.V.; Lopez, L.; Pellegrino, S.F. Physics informed neural networks for an inverse problem in peridynamic models. Eng. Comput. 2024, 5, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakim, M.; Behmardikalantari, G.; Abedini Najafabadi, H.; Pazuki, G.; Vosoughi, A.; Vossoughi, M. Prediction of liquid–liquid equilibrium behavior for aliphatic+aromatic+ionic liquid using two different neural network-based models. Fluid Phase Equilibria 2015, 394, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, R.; Fredenslund, A.; Rasmussen, P. Artificial neural networks as a predictive tool for vapor-liquid equilibrium. Comput. Chem. Eng. 1994, 18, S63–S67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanadzadeh, H.; Ahmadifar, H. Estimation of (vapour+liquid) equilibrium of binary systems (tert-butanol+2-ethyl-1-hexanol) and (n-butanol+2-ethyl-1-hexanol) using an artificial neural network. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 2008, 40, 1152–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urata, S.; Takada, A.; Murata, J.; Hiaki, T.; Sekiya, A. Prediction of vapor–liquid equilibrium for binary systems containing HFEs by using artificial neural network. Fluid Phase Equilibria 2002, 199, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, H.; Tochigi, K. Prediction of vapor–liquid equilibria using reconstruction—Learning neural network method. Fluid Phase Equilibria 2007, 257, 169–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyhani, S.Z.; Ghanadzadeh, H.; Puigjaner, L.; Recances, F. Estimation of Liquid−Liquid Equilibrium for a Quaternary System Using the GMDH Algorithm. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2009, 48, 2129–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghadam, M.; Asgharzadeh, S. On the application of artificial neural network for modeling liquid-liquid equilibrium. J. Mol. Liq. 2016, 220, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. In Proceedings of the KDD’16: The 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehner, P.; Bauer, G.; Gross, J. FeOs: An Open-Source Framework for Equations of State and Classical Density Functional Theory. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2023, 62, 5347–5357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontogeorgis, G.M. Thermodynamic Models for Industrial Applications: From Classical and Advanced Mixing Rules to Association theories; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Paszke, A.; Gross, S.; Massa, F.; Lerer, A.; Bradbury, J.; Chanan, G.; Killeen, T.; Lin, Z.; Gimelshein, N.; Antiga, L.; et al. PyTorch: An Imperative Style, High-Performance Deep Learning Library. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1912.01703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arce, P.F.; Vieira, N.F.; Igarashi, E.M.S. Thermodynamic Modeling and Simulation of Biodiesel Systems at Supercritical Conditions. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2018, 57, 751–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.M.; Van Ness, H.C.; Abbott, M.M. Introduction to Chemical Engineering Thermodynamics, 6th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Valderrama, J.O.; Zavaleta, J. Thermodynamic consistency test for high pressure gas–solid solubility data of binary mixtures using genetic algorithms. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2006, 39, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saali, A.; Shokouhi, M.; Sakhaeinia, H.; Kazemi, N. Thermodynamic Consistency Test of Vapor–liquid Equilibrium Data of Binary Systems Including Carbon Dioxide (CO2) and Ionic Liquids Using the Generic Redlich–Kwong Equation of State. J. Solut. Chem. 2020, 49, 383–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, V.H.; Aznar, M. Application of a Thermodynamic Consistency Test to Binary Mixtures Containing an Ionic Liquid. Open Thermodyn. J. 2008, 2, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V.; et al. Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Akiba, T.; Sano, S.; Yanase, T.; Ohta, T.; Koyama, M. Optuna: A Next-generation Hyperparameter Optimization Framework. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1907.10902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.; Sadowski, G. Application of the perturbed-chain SAFT equation of state to associating systems. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2002, 41, 5510–5515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.H.; Radosz, M. Equation of state for small, large, polydisperse, and associating molecules. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 1990, 29, 2284–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, D.J.; Mash, C.J.; Pemberton, R.C. NPL Report Chemistry; National Physical Laboratory: Middlesex, UK, 1979.

- McGlashan, M.L.; Williamson, A.G. Isothermal Liquid-Vapor Equilibriums for System Methanol-Water. J. Chem. Eng. Data 1976, 21, 196–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, J.B.; Funnel, W.S. The Determination of Vapor and Liquid Compositions in Binary Systems. I. Methyl Alcohol-Water. J. Phys. Chem. 1929, 33, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Li, H.; Han, S. Vapor–Liquid Equilibrium Data for Methanol–Water–NaCl at 45 °C. Fluid Phase Equilibria 1999, 4, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Wang, K.; Hu, Y. Studies on vapor-liquid and liquid-liquidvapor equilibria for the ternary system methanol-methyl methacrylatewater (Ⅱ) ternary system. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 1989, 4, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Broul, M.; Hlavaty, K.; Linek, J. Liquid-Vapour Equilibrium in Systems of Electrolytic Components: V the System Methanol + Water + Lithium Chloride at 60 c. Collect Czech Chem. Commun. 1969, 34, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuberth, H. Schuberth H. Influence of Simple Salts on the Isothermal Vapor-Liquid Equilibrium Behavior of the Methanol-Water System. Z. Fuer Phys. Chem. 1974, 255, 165–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Z.; Liu, M.; Yang, J. Measurement and Correlation of Moderate Pressure Vapor-Liquid Equilibrium Data for Methanol-Water Binary System. J. Chem. Ind. Eng. China 1995, 46, 230. [Google Scholar]

- Griswold, J. Phase-Equilibria of the Acetone-Methanol-Water System from 100℃ into the Critical Region. Chem. Eng. Progr., Symp. Syr. 1952, 48, 18–34. [Google Scholar]

- Schröder, W. Messungen von Siedegleichgewichten Bei Überdruck. Chem. Ing. Tech. 1958, 30, 523–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phutela, R.; Kooner, Z.; Fenby, D. Vapour Pressure Study of Deuterium Exchange Reactions in Water-Ethanol Systems: Equilibrium Constant Determination. Aust. J. Chem. 1979, 32, 2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, H.; Terano, T.; Nishi, Y.; Tokunaga, J. Vapor-Liquid Equilibria for Methanol + Ethanol + Calcium Chloride, + Ammonium Iodide, and + Sodium Iodide at 298.15 K. J. Chem. Eng. Data 1995, 40, 472–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herraiz, J.; Shen, S.; Coronas, A. Vapor−Liquid Equilibria for Methanol + Poly(Ethylene Glycol) 250 Dimethyl Ether. J. Chem. Eng. Data 1998, 43, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, D.T.; Lira, C.T.; Asthana, N.S.; Kolah, A.K.; Miller, D.J. Vapor−Liquid Equilibria in the Systems Ethyl Lactate + Ethanol and Ethyl Lactate + Water. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2006, 51, 1220–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurihara, K.; Minoura, T.; Takeda, K.; Kojima, K. Isothermal Vapor-Liquid Equilibria for Methanol + Ethanol + Water, Methanol + Water, and Ethanol + Water. J. Chem. Eng. Data 1995, 40, 679–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.W.; Diky, V.; Chirico, R.D.; Magee, J.W.; Muzny, C.D.; Abdulagatov, I.; Kazakov, A.F.; Frenkel, M. Quality Assessment Algorithm for Vapor−Liquid Equilibrium Data. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2010, 55, 3631–3640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuberth, H. Isothermic behavior of phase-equilibrium in the system N-alcohol-water-urea at 60-degrees Celsius. Z. Phys. Chem.-Leipz. 1980, 261, 777–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arango, I.C.; Villa, A.L. Isothermal Vapor–Liquid and Vapor–Liquid–Liquid Equilibrium for the Ternary System Ethanol+water+diethyl Carbonate and Constituent Binary Systems at Different Temperatures. Fluid Phase Equilibria 2013, 339, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristino, A.F.; Rosa, S.; Morgado, P.; Galindo, A.; Filipe, E.J.M.; Palavra, A.M.F.; Nieto De Castro, C.A. High-Temperature Vapour–Liquid Equilibrium for the Water–Alcohol Systems and Modeling with SAFT-VR: 1. Water–Ethanol. Fluid Phase Equilibria 2013, 341, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niesen, V.; Palavra, A.; Kidnay, A.J.; Yesavage, V.F. An Apparatus for Vapor—Liquid Equilibrium at Elevated Temperatures and Pressures and Selected Results for the Water—Ethanol and Methanol—Ethanol Systems. Fluid Phase Equilibria 1986, 31, 283–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr-David, F.; Dodge, B.F. Vapor-Liquid Equilibrium at High Pressures. The Systems Ethanol-Water and 2-Propanol-Water. J. Chem. Eng. Data 1959, 4, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murti, P.; Van Winkle, M. Vapor-Liquid Equilibria for Binary Systems of Methanol, Ethyl Alcohol, 1-Propanol, and 2-Propanol with Ethyl Acetate and 1-Propanol-Water. Ind. Eng. Chem. Chem. Eng. Data Ser. 1958, 3, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, E.; Schüttau, E.; Rant, D.; Schuberth, H. Die Beeinflußbarkeit des isothermen Phasengleichgewichtsverhaltens der Systeme 11-Propanol/Wasser und n-Butanol/Wasser durch einige Metallchloride. Z. Für Phys. Chem. 1971, 247, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woerpel, U.; Vohland, P.; Schuberth, H. The Effect of Urea on the Vapor-Liquid Equilibrium Behavior of n-Propanol/Water at 60 °C. Z. Phys. Chem. 1977, 258, 905–912. [Google Scholar]

- Wrewsky, M.Z. Composition and Vapor Pressure of Binary Mixtures. Phys. Chem. Stoechiom. Verwandschaftsl. 1913, 81, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliff, G.A.; Chao, K.C. Prediction of Thermodynamic Properties of Polar Mixtures by a Group Solution Model. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 1969, 47, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udovenko, V.V.; Mazanko, T.F. Liquid-Vapour Equilibrium in Propan-2-Ol-Water and Propan-2-Ol-Benzene Systems. Russ. J. Phys. Chem. USSR. 1967, 41, 863. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.S.; Hagewiesche, D.; Sandler, S.I. Vapor—Liquid Equilibria of 2-Propanol + Water + N,N-Dimethyl Formamide. Fluid Phase Equilibria 1988, 43, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyzlova, R.V.; Zaiko, L.N.; Susarev, M.P. Experimental Investigation and Calculation of Liquid-Vapor Equilibrium in the Ternary System n-Butyl Alcohol + Isobutyl Alcohol + Water at 35 c. Zhurnal Prikl. Khimii 1979, 52, 551–555. [Google Scholar]

- Kharin, S.E.; Perelygin, V.M. Liquid-Vapor Phase Equilibrium in Ethanol-n-Butanol and Water-n-Butanol Systems. Izv. Vyssh. Ucheb. Zaved Khim. Khim. Tekhnol. 1969, 12, 424–428. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).