Abstract

Smoothed particle hydrodynamics (SPHs) is a Lagrangian meshless method with distinct strengths in managing unstable and complex interface behaviors. This study develops an integrated multiphase SPH framework by merging multiple algorithms and techniques to enhance stability and accuracy. The multiphase model is validated by several benchmark examples, including square droplet deformation, single bubble rising, and two bubbles rising. The selection of numerical parameters for multiphase simulations is also discussed. The validated model is then applied to simulate oil–water–gas bubbly flows. Interface behaviors, such as coalescence, fragmentation, deformation, etc., are reproduced, which helps to take into account multiphysics interactions in industrial processes. The rising processes of many oil droplets for oil–water separation are first simulated, showing the advantages and stability of the SPH model in dealing with complex interface behaviors. To fully explore the potential of the model, the model is further extended to the field of wax removal. The melting process of the wax layer due to heat conduction is simulated by coupling the thermodynamic model and the phase change model. Interesting behaviors such as wax layer cracking, droplet detachment, and thermally driven flow instabilities are captured, providing insights into wax deposition mitigation strategies. This study provides an effective numerical model for bubbly flows in petroleum engineering and lays a research foundation for extending the application of the SPH method in other engineering fields, such as multiphase reactor design and environmental fluid dynamics.

1. Introduction

Viscous bubbly flow is a critical phenomenon in various industrial applications, including chemical reactors [1], nuclear reactors [2], mining processes [3], and ocean engineering [4]. The study of viscous bubbly flow is essential for optimizing the efficiency and safety of these operations. In chemical engineering, for example, the mixing of gases with liquids is a common process that can be significantly influenced by the viscosity of the fluids involved [5,6]. The behavior of bubbles in a viscous medium is complex, as it is affected by factors such as bubble size, shape, and the relative motion between the phases [7,8]. Understanding the dynamics of viscous bubbly flow is also crucial for enhanced recovery techniques, where gases are injected into reservoirs to increase the extraction rate [9]. Mining flotation is a critical separation technique used to concentrate valuable minerals from ores by selectively attaching them to air bubbles in a slurry. The efficiency of this process is highly dependent on the behavior of these air bubbles within the viscous slurry [10]. All of these processes are inseparable from an understanding of the complex mechanisms of bubble flow, in which numerical simulation plays a significant role [11,12].

Despite its importance, the accurate modeling and prediction of viscous bubbly flow remain challenging due to the nonlinear interactions between the bubbles and the continuous phase [13,14]. Traditional computational methods, such as volume of fraction (VOF) [15] and the front tracking method [16], often struggle to capture the intricate details of these flows, particularly at the interface between the phases [17]. Therefore, research into viscous bubbly flow is driven by the need to develop robust models and simulation techniques that can accurately model the behavior of bubbles in viscous environments. In the simulation of bubble flow, traditional numerical methods such as VOF have certain limitations [18]. The VOF method is the fluid volume fraction as a step function [19], which leads to significant variations in physical quantities at the interface and inaccurate calculations of interface normals and curvatures, thus introducing substantial errors in surface tension calculations [20]. Additionally, the VOF method requires complex interface capturing or tracking algorithms at each time step, which can introduce additional computational errors [21]. These errors are exacerbated when bubbles undergo large deformations, posing challenges to the accuracy of the interface capture. The interface capture in the VOF method is grid-dependent, and the need for very fine grids to capture interfaces during intense bubble motion increases computational costs [22,23].

To address these challenges, mesh-free methods have been proposed for the simulation of bubble flows or multiphase flows [24,25]. Examples of mesh-free methods include Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamics (SPHs) [26] and the Moving Particle Semi-Implicit method [27]. These mesh-free methods, by avoiding the constraints of grids, can more naturally handle fluid interfaces and free surfaces, making them particularly suitable for complex multiphase flow simulations [28,29]. The study of viscous bubbly flow is intricately linked to the application of advanced computational methods, with SPH emerging as a particularly advantageous approach. SPH is a mesh-free, Lagrangian computational technique that inherently excels at simulating free-surface flows and complex fluid interactions, which are characteristic of viscous bubbly flows [30]. One of the primary advantages of SPH in this context is its ability to naturally handle large deformations and topological changes without the need for remeshing, a common limitation in Eulerian and mesh-based methods [31,32]. This is particularly beneficial when modeling the dynamic behavior of bubbles, which can undergo significant shape changes and interactions within a viscous medium [33]. Moreover, SPH’s particle-based nature allows for a straightforward isation of multiphase systems, where each phase can be modeled with its own set of particles. This makes it an ideal tool for studying the interactions between bubbles and the continuous phase, including the effects of viscosity on these interactions [34]. The method’s adaptability to parallel computing architectures further enhances its efficiency [35,36], enabling the simulation of large-scale systems with a high degree of computational accuracy. This is crucial for capturing the fine details of bubble dynamics in a viscous environment, which can be critical for applications such as the design of industrial reactors or the optimization of mixing processes. Additionally, SPH can be easily coupled with other models to account for additional physical phenomena, such as fluid–structure interaction [37]. This capability is invaluable for a comprehensive understanding of the complex processes involved in viscous bubbly flows.

However, it should be noted that SPH, being a Lagrangian particle method, is susceptible to numerical instability and accuracy issues due to the influence of particle distribution and is highly sensitive to the selection of numerical parameters. For bubble flow, which often involves a significant density difference between the bubble fluid and the surrounding fluid, SPH simulations can easily encounter stability issues without proper treatment [38]. Existing SPH models for multiphase flows struggle with accurate surface tension for three immiscible phases (oil, water, and gas), interfacial stability under large density ratios, and lack coupled thermodynamics for phase-change processes like wax melting. To address these gaps, this study develops a modified surface tension model for three-phase interactions, enhances interface stability via repulsive forces and particle shifting, and integrates thermodynamic/phase-change models, enabling the first SPH simulation of phenomena like wax layer melting, cracking, and droplet detachment.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 details the numerical framework of the multiphase SPH model, including governing equations, viscosity and surface tension formulations, and interface stabilization techniques for high-density-ratio flows. Section 3 validates the model through benchmark cases such as square droplet deformation, single-bubble rising, and multi-bubble coalescence, demonstrating its accuracy and robustness. Section 4 applies the validated model to simulate oil–water–gas bubbly flows, investigating interfacial dynamics in scenarios such as single and multiple oil droplet rising, coalescence, and separation processes. Section 5 extends the framework to wax removal simulations by coupling thermal dynamics and phase change models, capturing wax layer melting and droplet detachment behaviors. Finally, Section 6 summarizes key findings, discusses industrial implications, and outlines future research directions.

2. Methodology and Modeling

2.1. Fluid Dynamics Equations

In this model, fluids across the interface are defined as heavy and light phases. Incompressible fluid behavior is governed by Navier–Stokes equations, including continuity and motion equations:

where ρ is density, kg/m3; is velocity, m/s; t is time, s; p is pressure, Pa; is viscosity, N·s/m2; and and are surface tension and body forces, N/m3.

As the governing equations are unclosed, an equation of state (EOS) correlates pressure with density. Under weak compressibility, fluid pressure p is expressed as a function of density ρ, with the following EOS adopted herein [39]:

where c is sound speed; ρ0 is reference density; is a constant; and is defined as background pressure. The subscripts h, m, and l stand for heavy, medium, and light phases, respectively.

Hence, the EOS can be reformulated individually for each phase:

where , and .

The sound speed must be chosen carefully to ensure the fluid’s weak compressibility. Fluid compressibility is characterized by the Mach number:

where is so-called Mach number; Vb is characteristic velocity, m/s; and denotes the degree of compressibility of fluid. Here, the sound speed of the heavy phase is determined first, and the light phase is calculated according to the proportionality constant. is determined by

where is the maximum velocity, m/s; is the bubble or droplet radius, m. Then, is calculated with [7]:

The selected EOS is suitable for weakly compressible SPH, balancing computational efficiency and accuracy in density–pressure correlation. Surface tension causes negative pressure in interface-adjacent particles, particularly under large interface motion, leading to tension instability [40]. Thus, background pressure is typically used in SPH models with no free surface or multiple phases. Its selection is usually empirical, varying by problem: Insufficient pressure fails to eliminate negative pressure, while excess causes excessive particle resetting.

The background pressure is determined with

where the parameter takes the value from 10 to 60; is the surface tension coefficient, N/m.

2.2. SPH Formulation of Governing Equations

Since the governing equation (i.e., Equations (6) and (7)) is expressed in Lagrangian form, the discretized governing equations is directly derived in the form of the derivative of density and velocity of the particle:

where the subscript i is the index of the i-th particle. Thus, according to Equations (4) and (5), all items on the right side of Equations (15) and (16) can be transformed into the summation form of SPH particles, and then the discrete equation of the governing equation in Lagrangian form can be obtained. The general form of SPH formulation of governing equations is expressed as follows:

where , ,, and are the density and the mass of the i-th particle and j-th particle, respectively. and are indices for the Cartesian coordinates x and y, respectively. N is the total number of particles in the neighborhood of the concerned particle (i.e., the i-th particle). is , showing the vector characteristics of the kernel gradient. However, Equations (17) and (18) cannot be directly applied to multiphase flow simulations, especially when the density on both sides of the interface is large (i.e., the density ratio of 100.0). For the problem of multiphase flow with large density ratio, the sudden change in density and mass at the interface can result in numerical discontinuities at the interface and lead to numerical instability. To solve the density discontinuity problem in SPH multiphase simulations, Colagrossi et al. suggested a modified correction for the continuity equation:

where is used to replace in the particle summation equation. When i and j belong to different phases and the density ratio is large, the numerical interface calculated by Equation (19) is more stable. The established multiphase model was then used to simulate the bubble rising and dam-break multiphase flow, and the effectiveness of the model was verified.

This form of density derivative equation was also widely used in multiphase flow simulations with a large density ratio, such as underwater explosions. However, in the early multiphase model, a density correction scheme is needed to solve the problem of pressure noise caused by density fluctuation. Hence, the density dissipative scheme was proposed, but it has not been applied to the surface-tension-dominated multiphase flow.

To solve the problem of discontinuity of particle mass and density at the interface, the particle approximated equation based on particle volume was used to replace the continuity equation in the form of density derivative. This equation can guarantee the conservation of mass in the domain, which is derived according to the following procedure:

where is the volume of the particle i, m3; ρi is the density of particle i, kg/m3; mi is the mass of the particle, kg; and is the kernel function value, with as the spatial distance between particles i and j. In this study, the re-normalized Gaussian function is adopted as the kernel function because of its preferable propertied, and its expression is as follows:

where is the spatial distance between particles i and j; h is the smoothing length, taken to be 1.33 times the initial particle spacing; that is, h = 1.33∆x. The coefficients are and , and they are selected to make the Gaussian function no longer approach zero infinitely to ensure the compactness.

Similarly, for establishing the SPH discrete form of momentum equation, the sudden density changes across the interface should be considered. For the pressure gradient term, the particle density is replaced by the particle volume, and then the discrete form of the pressure gradient term can be written as

where , , , and denote the pressure and the volume of particles i and j, respectively.

The viscous force term in the discrete equation follows the form [41]:

where and are the dynamic viscosities of particles i and j. The parameter ε is to prevent the denominator from being zero, taking the value of 0.01.

In the SPH multiphase flow simulation considering fluid viscosity, two forms of viscous force terms are usually used. The viscous force term in the discrete equation follows two forms:

where and is the dynamic viscosity of particles i and j. The parameter ε is to prevent the denominator from being zero, taking the value of 0.01. The adopted viscosity formulation (type 2) better handles interactions between phases with varying viscosities, reducing numerical instability.

2.3. Surface Tension Modeling

2.3.1. Standard Algorithm

The continuum surface force (CSF) model is employed to simulate the impacts of surface tension. Within the CSF model, the surface tension force is described as a function that depends on the curvature and normal vector of the interface [42].

where ξ is curvature; n is normal.

For the purpose of computing the interface’s normal vector, a color function is defined in the following manner:

The color function is calculated with the following equation [43]:

In Equation (22), the color function is assigned weights based on the density ratio of the two interacting fluids. This weighting approach contributes to enhancing the prediction precision of both the normal vector and curvature. By computing the gradient of the color function, the unit normal vector corresponding to particle i can be derived as follows:

In calculating the interface curvature, an additional color function is adopted:

The curvature is finally calculated with

where d is the dimension of space.

2.3.2. Corrected Algorithm

The accuracy of curvature calculation is contingent upon the precision of the normal vector, which in turn relies on the accuracy with which the gradient of the color function is computed. Consequently, a modified kernel gradient operator is employed in place of the standard one for implementing the surface tension model. Equation (27) presents the expressions after the application of this corrected kernel gradient.

where denotes the corrected kernel gradient.

The interface tension force is calculated with

2.3.3. For Three Fluid Phases

When the multiphase flow contains fluids of three phases or more, such as a mixture of oil, gas, and water, some modifications to the multiphase SPH model are required to apply to the three-phase flow calculation. For the calculation of surface tension, when the calculation domain contains only two phases (such as gas–liquid), the surface tension of particles near the interface can be expressed as

where is the interface tension between light phase and heavy phase.

For the three-phase flow of oil, gas, and water, when calculating the interface tension, there may be three phases simultaneously in the supporting domain of particles. Assume that particle i belongs to the heavy phase, and there are both light phase and medium phase in its supporting domain, then the gradient of color functions is calculated separately for arbitrary two phases:

Substituting Equations (24) and (25) into Equation (18), the separated normal vectors and and the separated interface curvatures and can be obtained. Then, the interface tension acting on l-m interface and l-g interface can be expressed as

The total interfacial tension acting on particle i is the sum of the two forces:

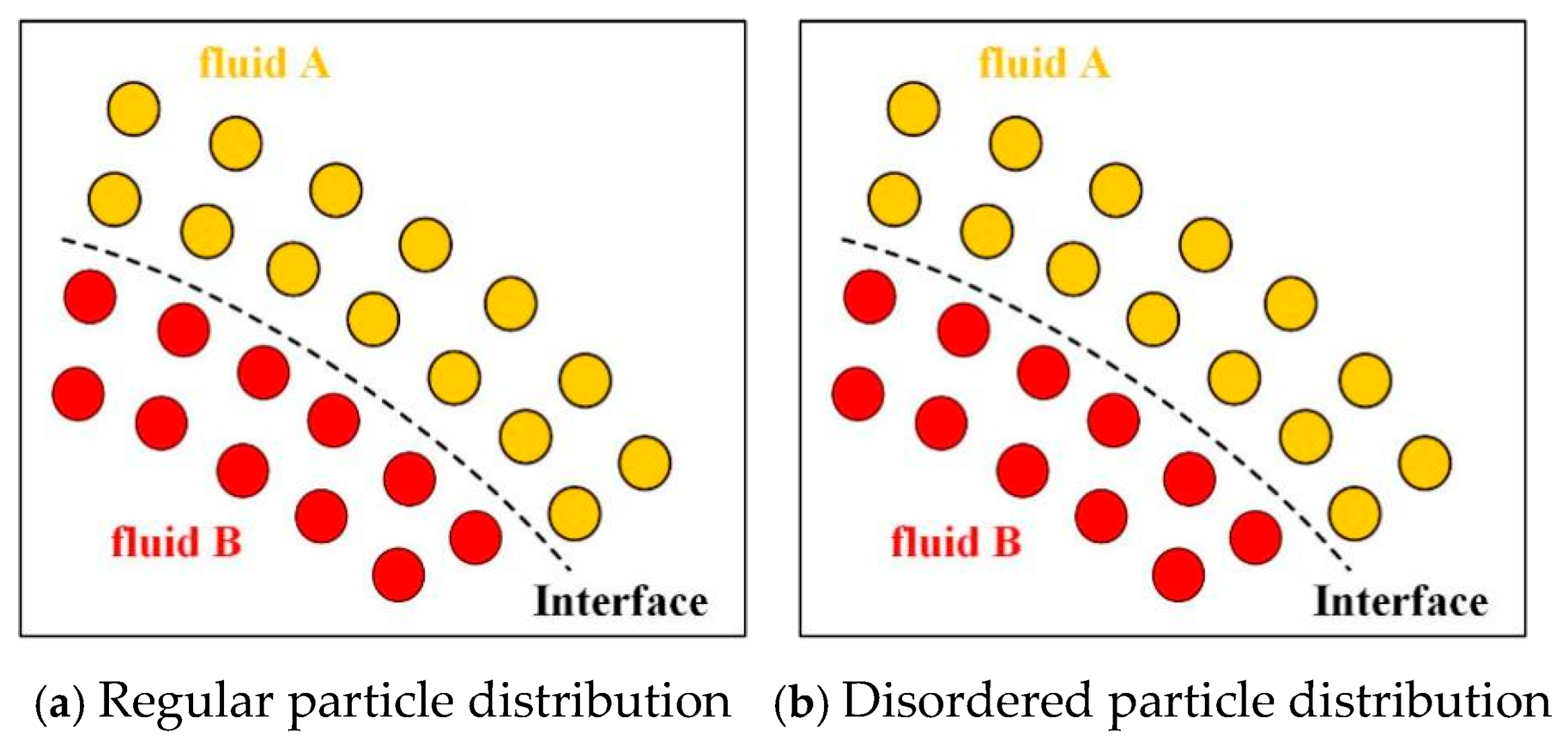

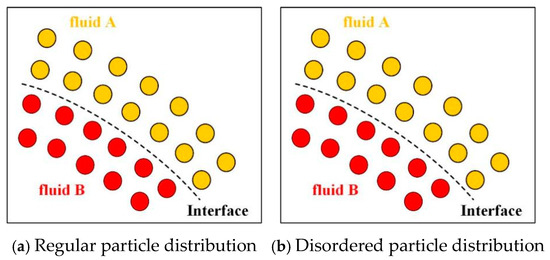

2.4. Interface Repulsive Force

In the multiphase SPH model featuring a sharp interface and a large density ratio, the handling of the interface is of vital significance for numerical stability. The interactive area between the two phases is illustrated in Figure 1. The interface always exists in an “explicit” manner, and its position can be identified based on the particle positions of the two distinct phases (fluid A and fluid B in Figure 1a). Nevertheless, when there is a large density ratio, the interface becomes unstable. This is because particles in the vicinity of the interface may be distributed in a disorderly way (as shown in Figure 1b), and particles from the two phases have a tendency to penetrate each other. This leads to an incorrect phase interface and numerical instability. Thus, specific techniques ought to be adopted to hinder particles from penetrating the interface.

Figure 1.

Illustration of particles near the interface [44].

The interface force is added to the momentum equation as a volumetric force, which is expressed as

where is a constant, usually taking a value from 0.01 to 0.1.

Additionally, in order to address the issue of uneven particle distribution brought about by significant interface deformation, a particle shifting algorithm is utilized. This algorithm adjusts the particles’ positions during the simulation through the application of the equations listed below:

where the constant C is from 0 to 0.01.

3. Numerical Implementation of the Multiphase SPH Model

The complete version of discrete equations governing the multiphase flow dynamics is expressed as

The prediction correction scheme is used for time integration. Within a time step, the first step is used to predict the particle density , velocity , displacement , and temperature . On the basis of the new particle position obtained from the prediction step, field variables obtained from the prediction step are modified, and the density , velocity , displacement , and temperature of the correction step are obtained.

According to the CFL condition, the time step is calculated with the following relations:

where the coefficient CFL is set as . According to the four criteria, the minimum value among the four results is finally selected as the time integral step.

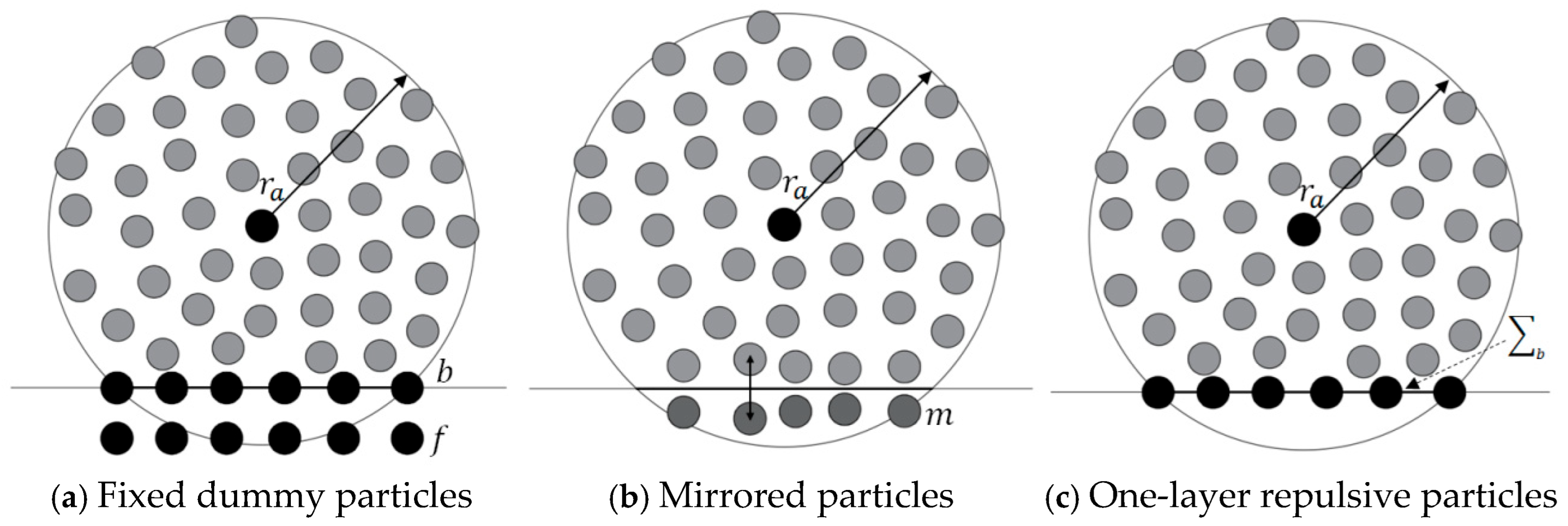

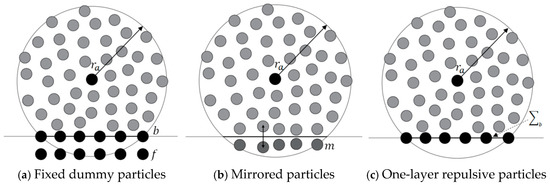

Figure 2 shows the three types of boundary conditions commonly used in the SPH method, which are fixed virtual particle boundary, mirrored particle boundary, and single-layer repulsive force boundary. Among them, the fixed virtual particle boundary and the mirrored particle boundary can realize the conditions of no-slip and free-slip. In addition, the periodic boundary is usually used for inflow and outflow condition. In the simulation of this study, the no-slip boundary and the free-slip boundary are realized by the mirrored particle technique. For the free-slip boundary condition, the field variable information of the mirrored particle can be given according to the following equations:

where the subscript i is the index of fluid particles, and g is the index of mirrored particles. vg,t and vi,t denote the tangential velocity of mirrored particles and fluid particles, respectively. vg,n and vi,n are the normal velocity.

Figure 2.

Boundary conditions.

In the SPH model, the computational domain of the flow field is characterized by a series of Lagrangian particles, which carry all the field variable information. When it is necessary to monitor the flow field information of a fixed point in the computational domain, the field variable value at that point needs to be calculated by interpolation. This study uses the kernel function to interpolate and calculate the value of field variable A at point i:

where is the value of field variable A at the point i. is the position vector of the point i; i.e., . N denotes the number of particles which are located inside the circle centered at the point i and with the radius of .

The vorticity vector of the flow field at any arbitrary point is calculated with the following equation:

where is the vortex at the position of . are the x and y coordinates of an arbitrary point in the fluid domain.

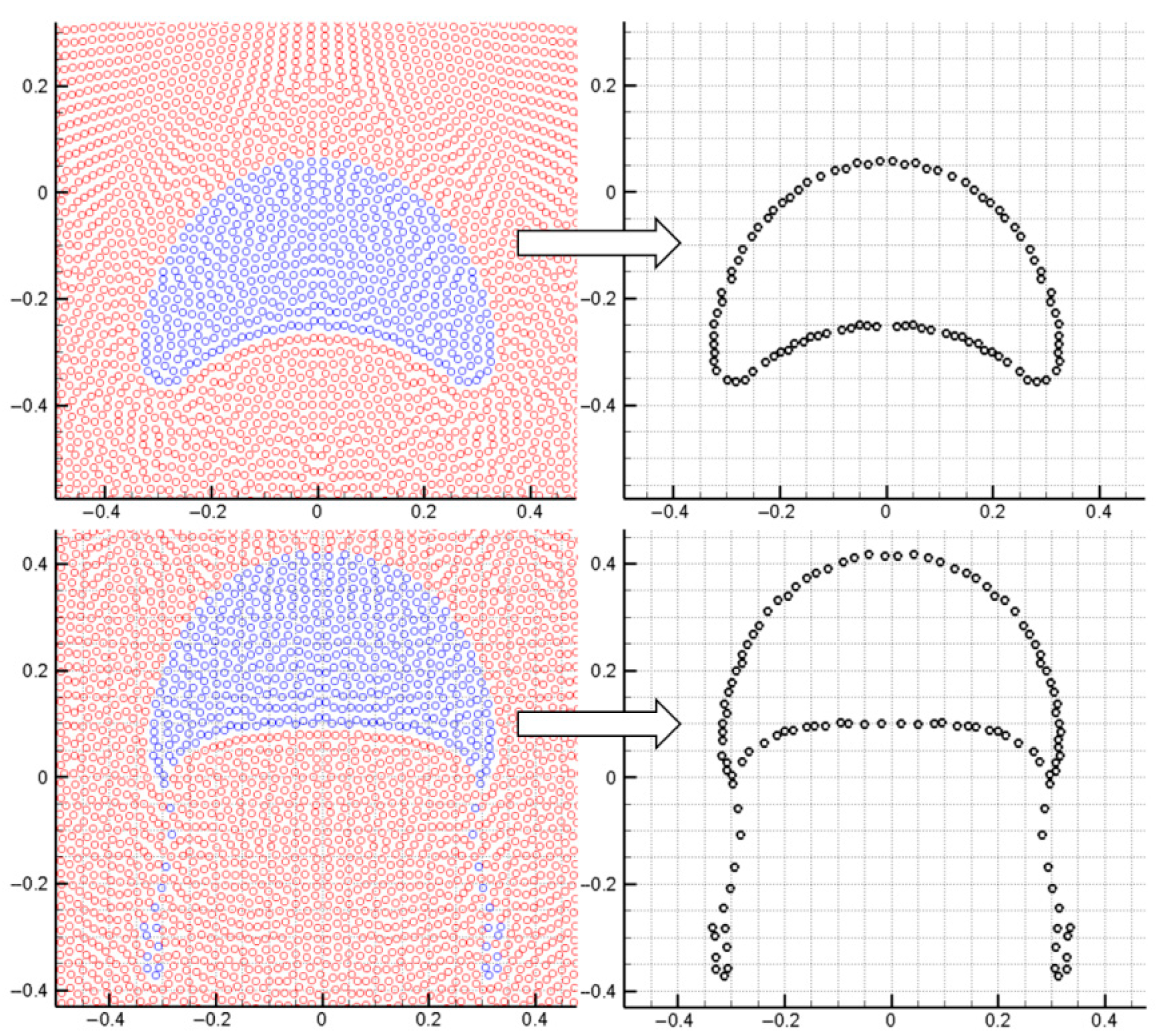

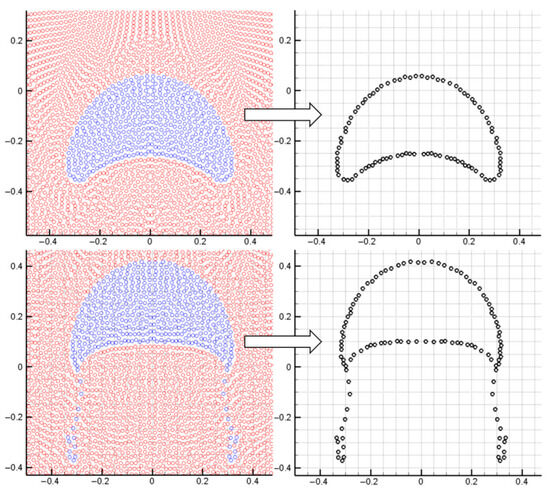

In bubbly multiphase flows, it is necessary to monitor the evolution process of bubble morphology. This study adopted an accurate boundary particle detection method to monitor the boundary particles of the bubble. The detailed procedure of detecting boundary particles can be referred to [45]. In the procedure, the first step is to take the concerned particle i as the center and establish an outer circle with radius h. Through scanning the neighboring particles of particle i, the intersection area between each neighboring particle and particle i can be determined. Then, the outer circle of particle i is flattened, a point (a, b) on the outer circle is used as the starting point, and each curve that crosses the outer circle of particle i is traversed and sorted according to the distance from the starting point. If all the intersecting areas can completely cover the outer circle of particle i, particle i is identified as an internal particle; otherwise, it is a boundary particle. By using this method, the boundary particles of the droplet can be accurately determined, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Detecting the surface particles of the bubble and reproducing the bubble profile.

Particle Searching Procedure

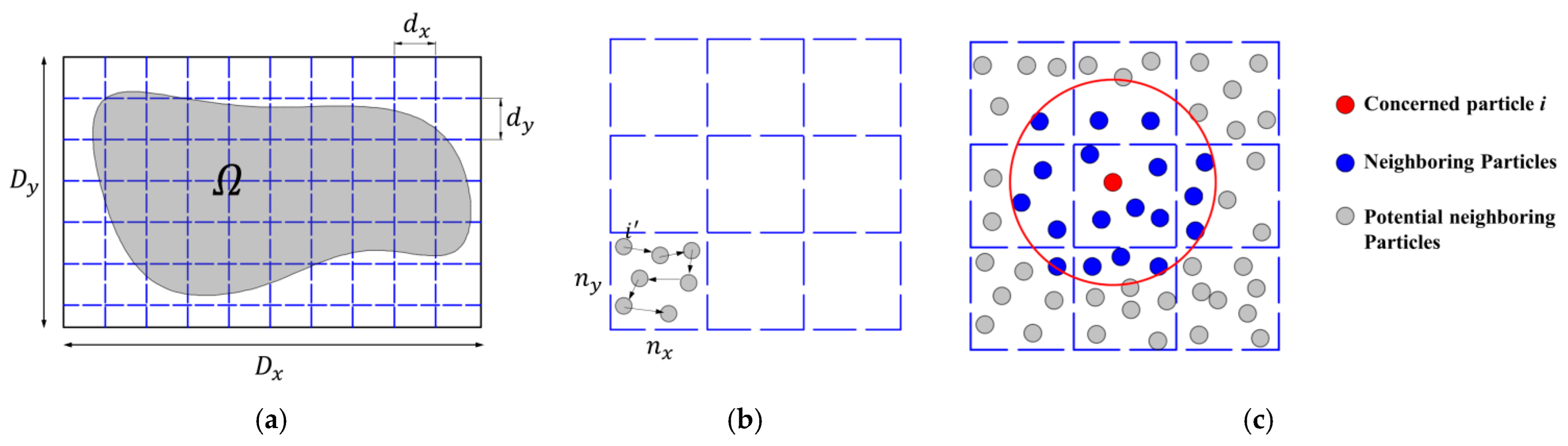

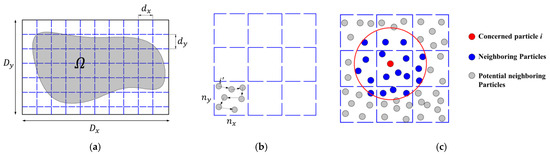

In the SPH method, the kernel function defines a compact supporting domain. When performing particle approximation, only a limited number of particles are in the supporting domain with a radius of κh. These particles, located in the supporting domain, are called “neighboring particles” of the particle to be evaluated. Commonly used neighboring particle search algorithms include the direct search method, linked-list method, and tree search method. The linked-list method is the most commonly used method, which is superior to the other two methods in terms of computational efficiency and difficulty of implementation. The first step of the linked-list method is the initialization of the background grid. The background grid is generated with the dimensions and . The grid domain should perfectly cover the computational domain . In addition, the grid cell length and must conform to the following criterion: , and , where is the radius of the smoothing domain. When the cubic spline smoothing function is used, has a relation with the smoothing length of . The number of grids in the x and y directions can be calculated with

where and are the number of grids in the x and y directions, respectively.

As shown in Figure 4, based on the generated background grid, the second step is to construct the linked list. The first substep is to traverse the particles in the computational domain to determine the grid to which each particle belongs. Then, the linked list is constructed for each grid cell. The detailed process refers to the following pseudo code:

where is the total particle number in the domain , and and are the cell numbers that the particle is located in. The array celldata() is the linked list, which connects all the particles in the same grid cell. The particle , which is the “first” particle in the cell <>, can be indexed by the array grid(). Once the first particle is identified, other particles in this cell (i.e., <>) can be indexed by using the list celldata().

Figure 4.

(a) Background grid covering the domain Ω, (b) particle-list in the grid cell <>, and (c) neighboring particles and adjacent grid cells [46].

Based on the background grid and the linked list, the NPS can be carried out for all particles in the domain. For the concerned particle i, we first locate the grid cell where the particle is located. Then, the NPS process is conducted on the associated cell and its eight adjacent grid cells. In each of nine cells, the list celldata() is used to dig out the individual particle for comparison, and the distance between the concerned particle and the extracted particle is calculated to judge whether the particle is a neighboring particle.

4. Model Validations

4.1. Numerical Parameter Settings

Moreover, the SPH method involves numerous computational parameters that must be configured, exerting a vital impact on accuracy, stability, and efficiency. Several such parameters warrant attention, as presented in Table 1, including particle interval, smoothing length, synthetic sound velocity, and others. Of these, the synthetic sound velocity and unit time step can be selected based on relevant equations. The particle interval stands as the initial parameter to be set in SPH simulations, correlating with total particle count and particle resolution, while exerting a significant effect on computational efficiency and precision. In the simulations conducted herein, the particle interval value is chosen according to the bubble radius. The smoothing length scales with the particle interval; a larger scaling factor leads to greater smoothing length and support domain radius, increasing the number of particles within the support domain and thus prolonging the computational time for particle searching. As given in Table 1, the smoothing length is set to 1.4 times the particle interval, with the associated support domain radius being 4.2 times the particle interval. Background pressure and interface numerical force are critical parameters determining the stability of interfaces with high density ratios. Yet overly high background pressure can amplify pressure noise in the computational domain, and excessive interface numerical force may enhance non-physical repulsive forces between interface particles, resulting in inaccurate interface calculations.

Table 1.

Parameter settings for general applications.

Building upon the multiphase SPH model presented in Section 2 and the model validation results in Section 3, the interface behaviors of oil droplets and gas bubbles during their ascent in various viscous fluids are examined. Prior to presenting the SPH simulation outcomes, several dimensionless numbers need to be defined, including the Reynolds number (Re), Bond number (Bo), and Morton number (Mo):

where is the fluid density of the heavy phase, and is the characteristic velocity or terminal velocity of the rising bubble. denotes the diameter of the bubble.

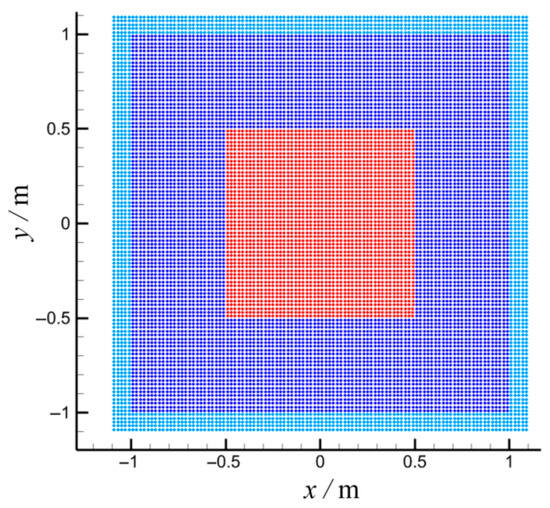

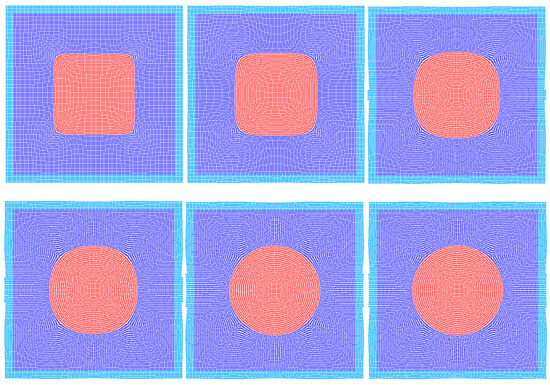

4.2. Square Droplet Evolution

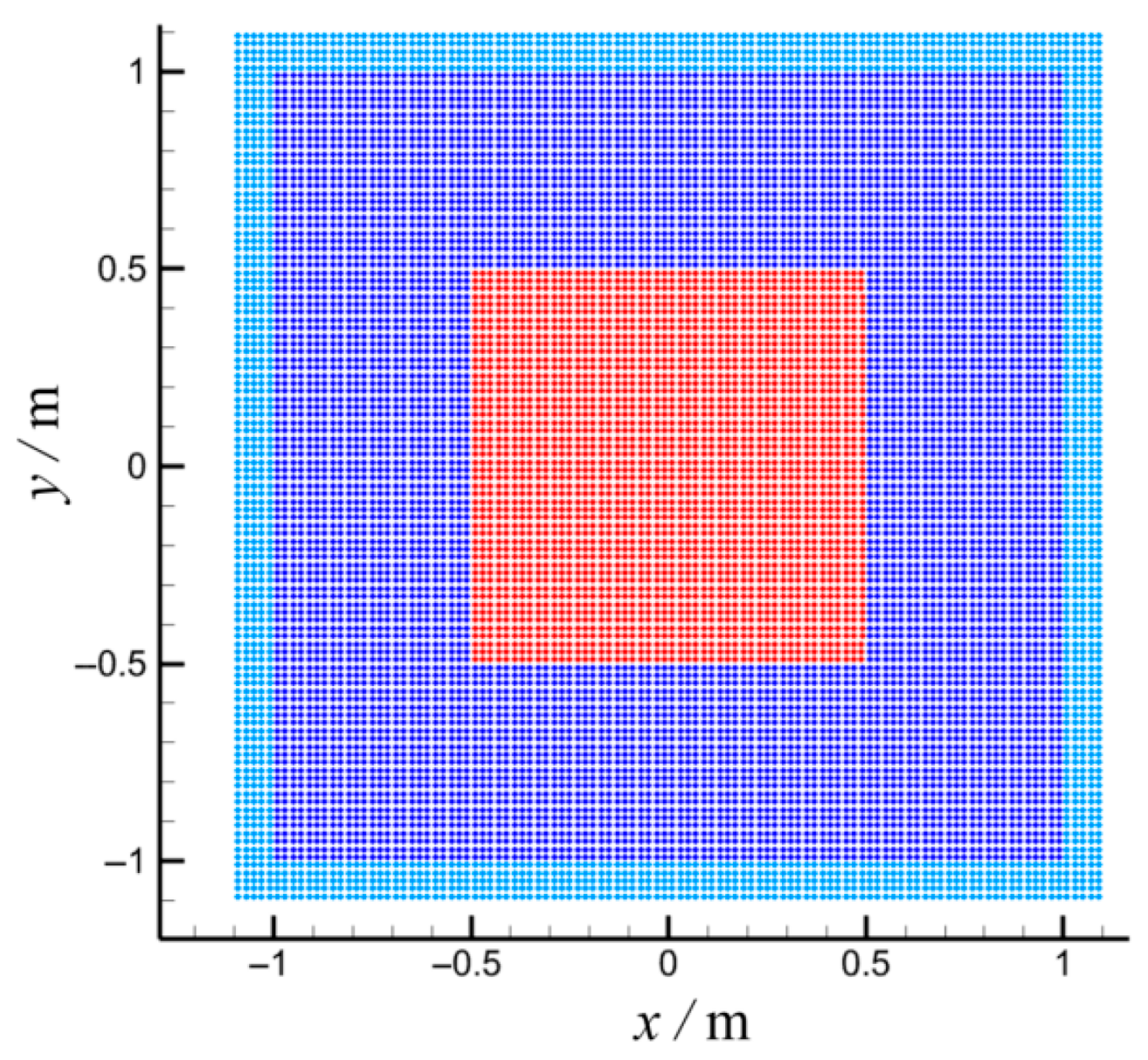

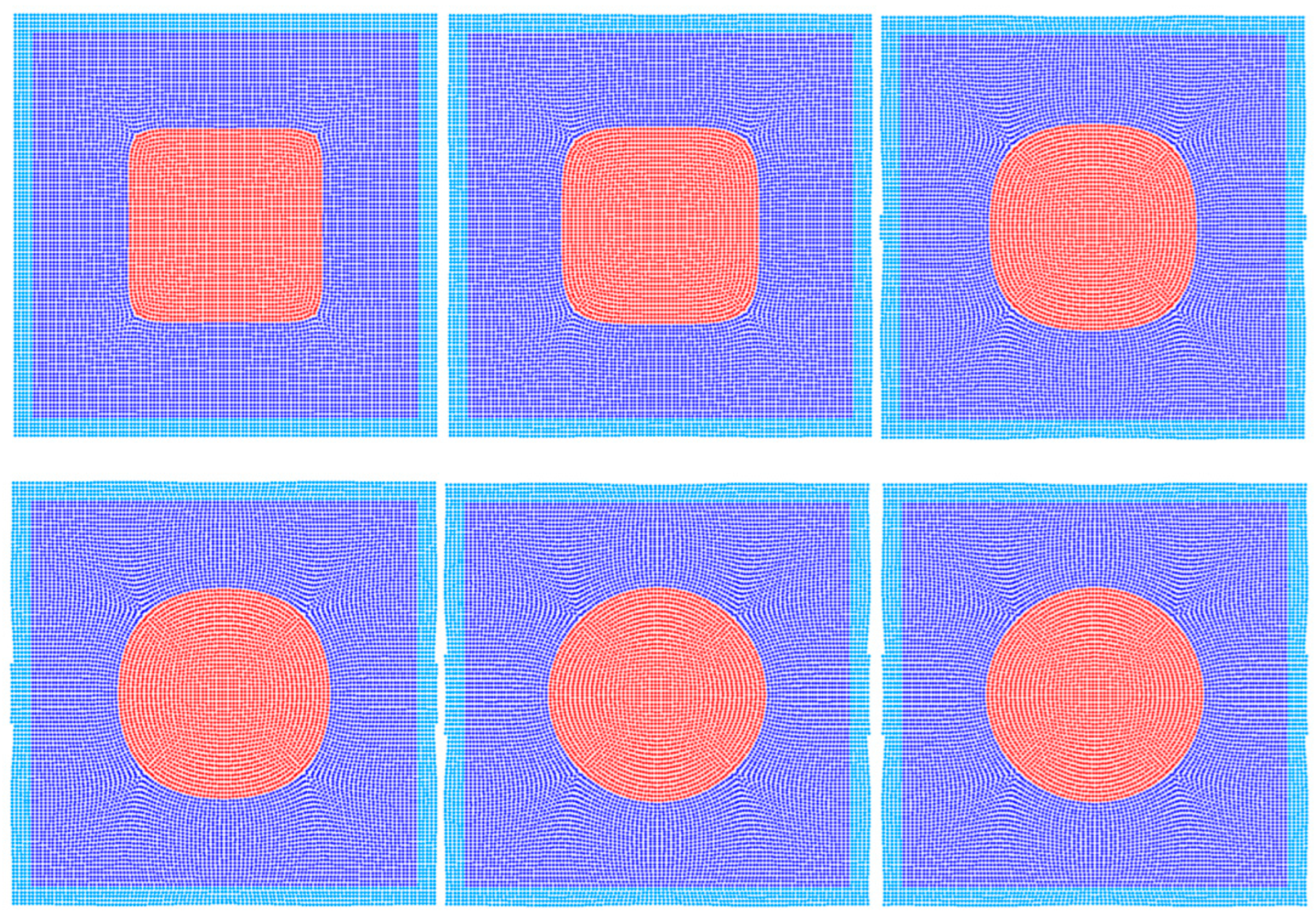

In this section, we simulate an initially square-shaped bubble in the absence of gravitational forces. The bubble undergoes deformation, contraction, and oscillation due to surface tension, ultimately transforming into a circular and stable bubble. The discrepancy in pressure across the bubble’s interface is referred to as the Laplace pressure difference and is derivable using the theoretical formula Pa, where is the surface tension, and is the bubble’s radius. This serves as a test case for validating the accuracy of the surface tension model. The material parameters are given in Table 2. Figure 5 presents the initial model of the square bubble oscillation simulation. Red particles are the bubble, blue particles are the fluid surrounding the bubble, and light blue particles are the boundary mirror particles. The initial spacing of the particles shown in Figure 5 is R/100. In addition to this, this paper also investigates the effect of particle spacing on the computational results, including R/50 and R/150. Figure 6 displays the simulation results of the deformation process of an initially square bubble under the action of surface tension.

Table 2.

Physical parameters for square droplet evolution.

Figure 5.

The initial SPH model for square bubble oscillation.

Figure 6.

SPH simulation results of initially square bubble deformation process.

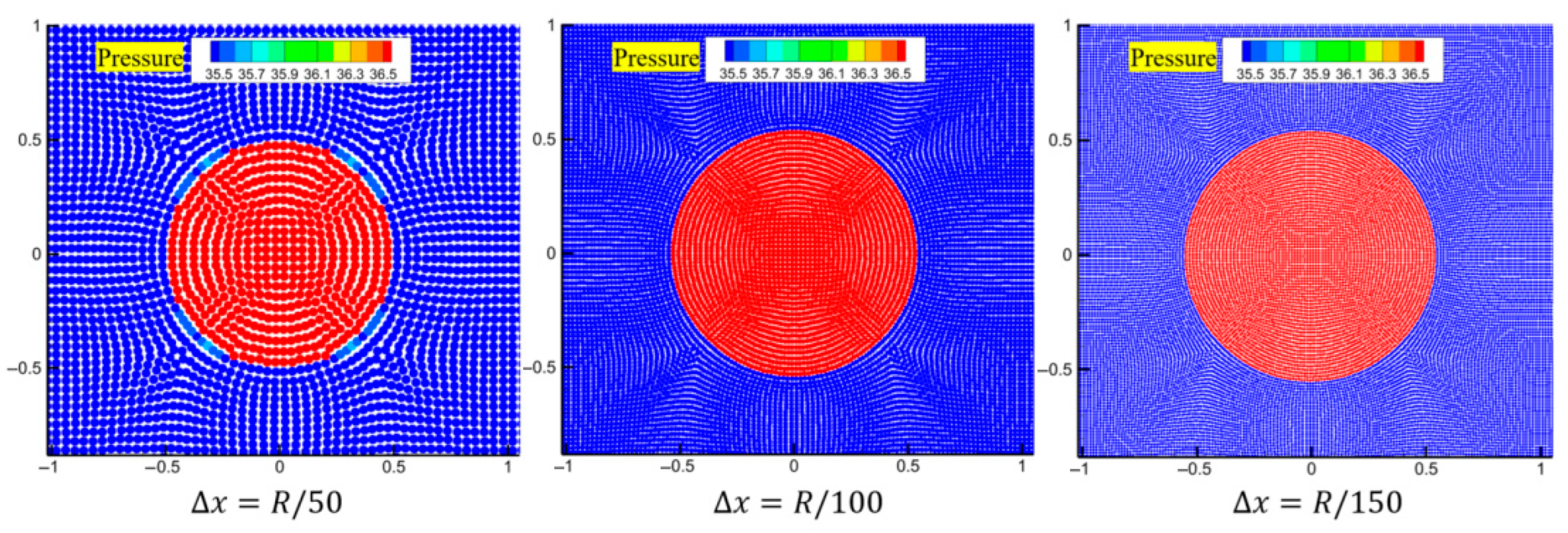

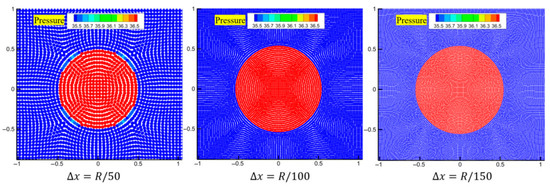

At the initial moment, due to the high curvature at the corners of the square bubble, it begins to contract under the action of surface tension. The curvature gradually decreases, and the bubble evolves into a circular shape, which is the state of minimum surface energy. Figure 7 shows the pressure distribution results after the bubble has stabilized. As can be seen from the figure, once the bubble reaches a quasi-static circular shape, the pressure inside the bubble is higher than the pressure outside the bubble. The difference between these two pressures is also known as the Laplace pressure difference.

Figure 7.

The pressure distributions obtained after reaching stability for three different particle resolutions.

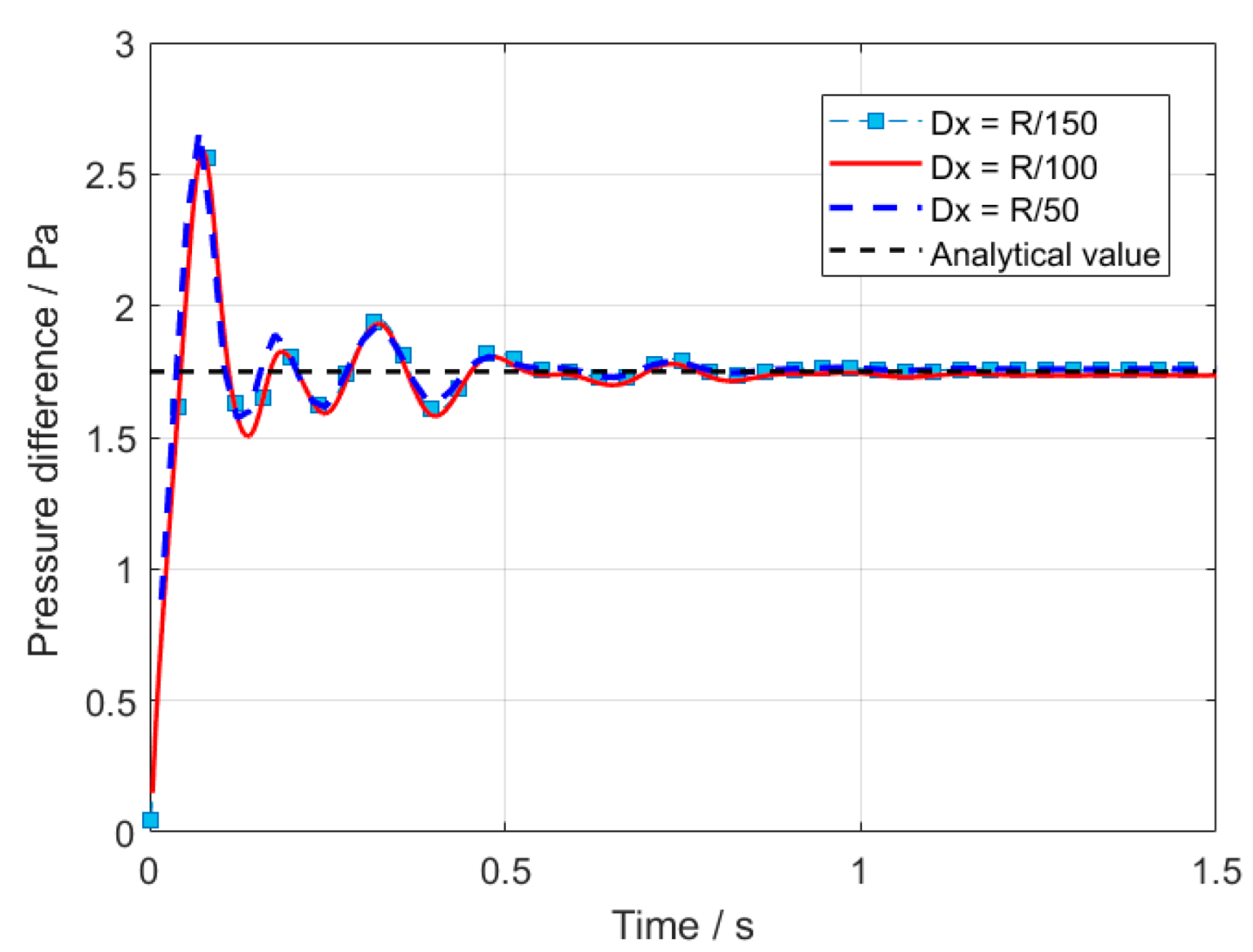

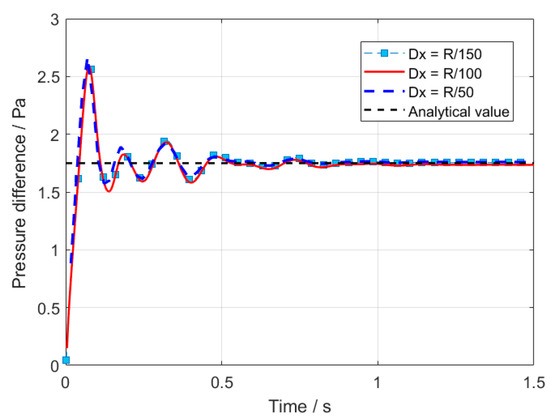

As depicted in Figure 8, the pressure difference curves for the three different particle resolutions all approach the theoretical solution; however, the smaller the initial spacing of the particles, the greater the fluctuations in the pressure difference. Additionally, we conducted observations on the pressure distribution once the bubble had reached a stable shape.

Figure 8.

Time history of pressure difference between inside bubble and outsider bubble.

4.3. Single Bubble Rising

Within this section, the scenario of a solitary bubble ascending is employed to affirm the numerical model’s convergence. The simulation parameters are detailed in Table 3. During the ascent of a bubble, its deformation and motion are primarily influenced by fluid viscosity, buoyancy, and surface tension. Buoyancy is the predominant force during the bubble’s acceleration stage, while viscosity dictates the bubble’s terminal velocity. The final shape of the bubble is a result of the interplay between viscous forces and surface tension. Surface tension, which aims to minimize the bubble’s surface energy, significantly affects its shape.

Table 3.

Parameters for the rising process of single bubble.

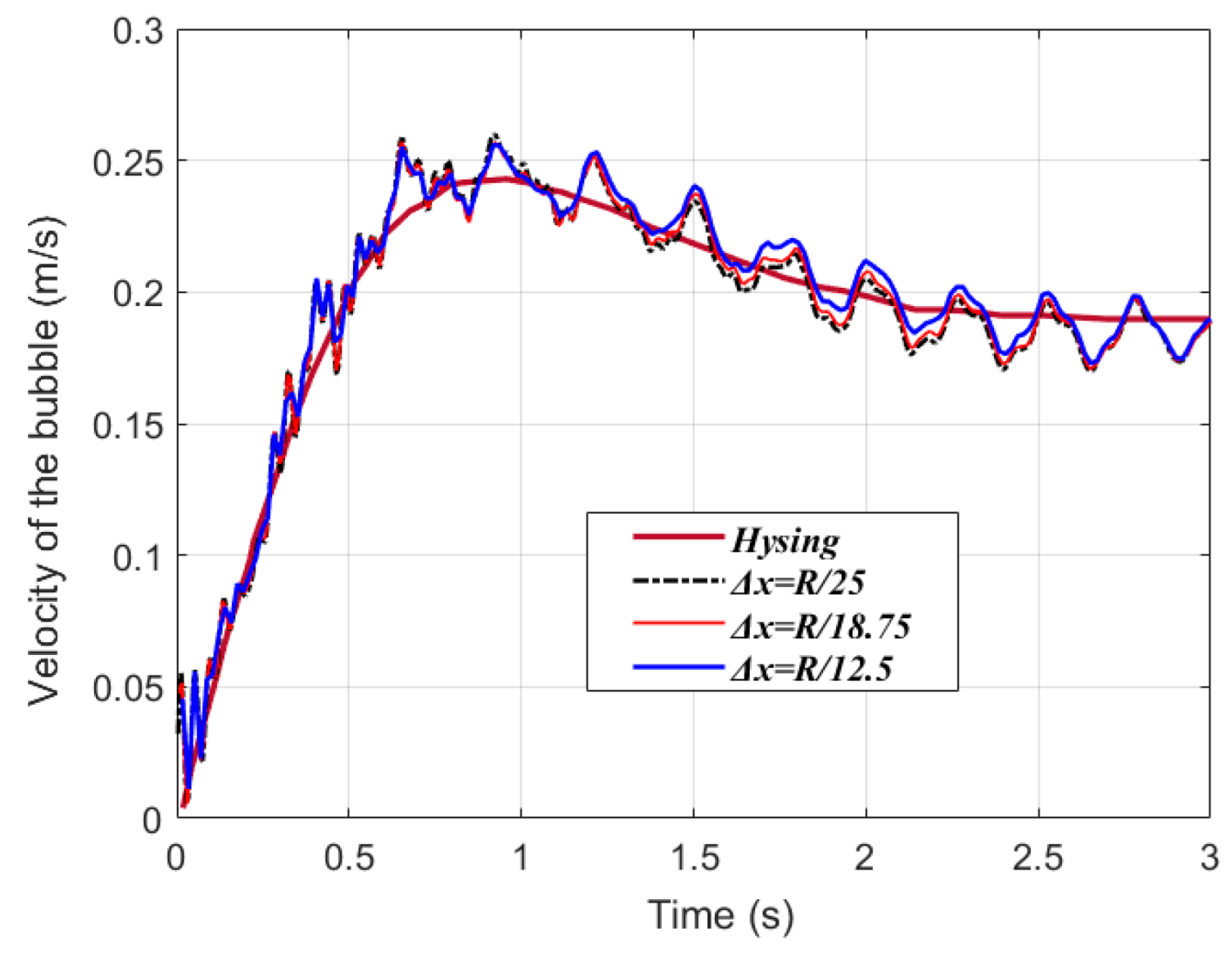

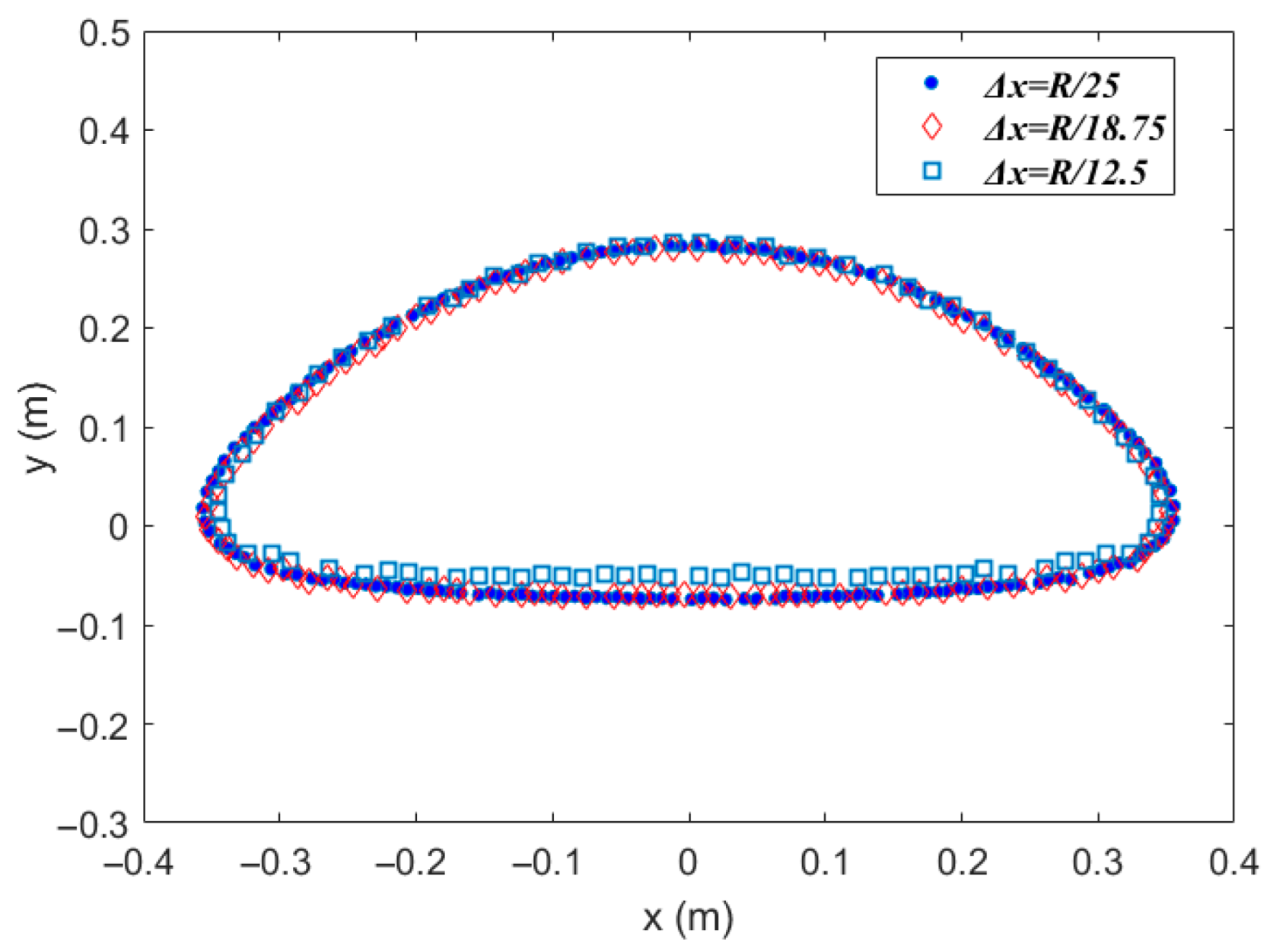

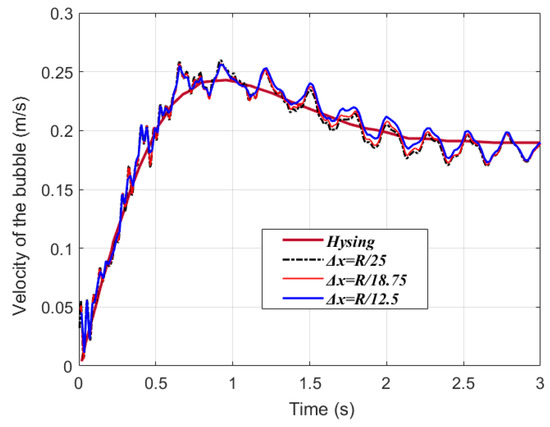

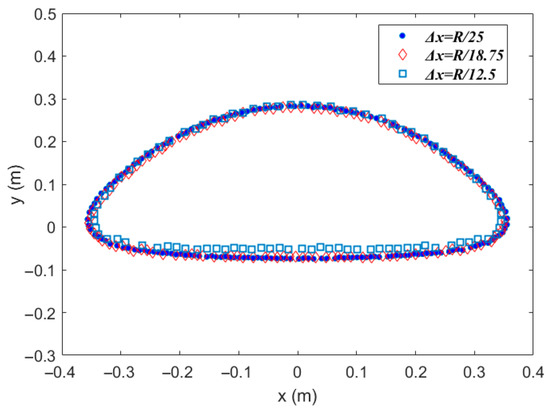

Figure 9 depicts the bubble’s velocity as a function of time. Initially, the bubble experiences an acceleration phase; after reaching its peak velocity, there is a slight decrease, followed by the attainment of a relatively constant velocity. A comparison between the SPH model’s predictions with varying particle spacings and the theoretical models reveals that, despite some fluctuations in the SPH-modeled curve, the overall trend closely matches the published data. The bubble’s velocity, derived from different particle spacings, is essentially indistinguishable, suggesting a level of convergence in the numerical simulations. Figure 10 presents the predicted bubble shapes, indicating that the morphologies derived from the three different particle spacings are largely consistent.

Figure 9.

Time history of rising velocity of the bubble.

Figure 10.

Comparison of the bubble profile for different particle spacings.

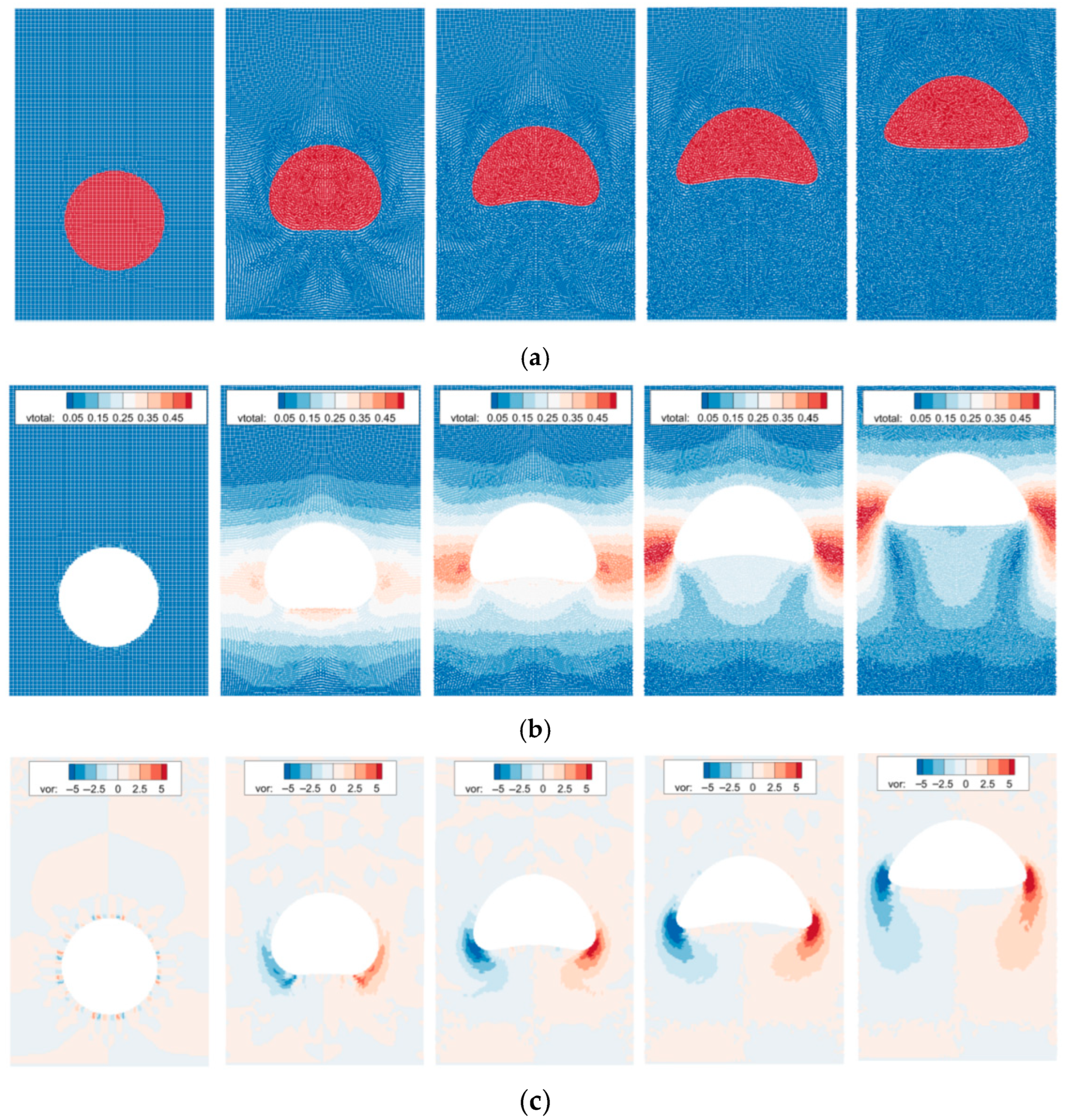

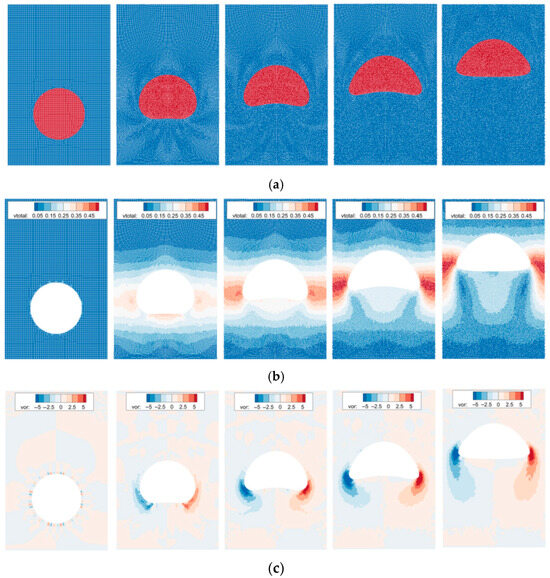

Figure 11 presents the SPH simulation outcomes of a bubble rising at various time intervals. The Figure 11a displays the distribution of SPH particles at different moments, with red particles being the bubble and blue particles being the surrounding water. The deformation and evolution of the bubble’s morphology can be observed through the particle distribution at these various times. Figure 11b,c illustrate the simulated results for the velocity and vorticity fields, respectively. For clarity, the bubble particles are excluded, and only the particles of the fluid surrounding the bubble are shown.

Figure 11.

SPH simulation results of bubble ascending process. (a) particle distribution, (b) velocity distribution, and (c) vorticity distribution.

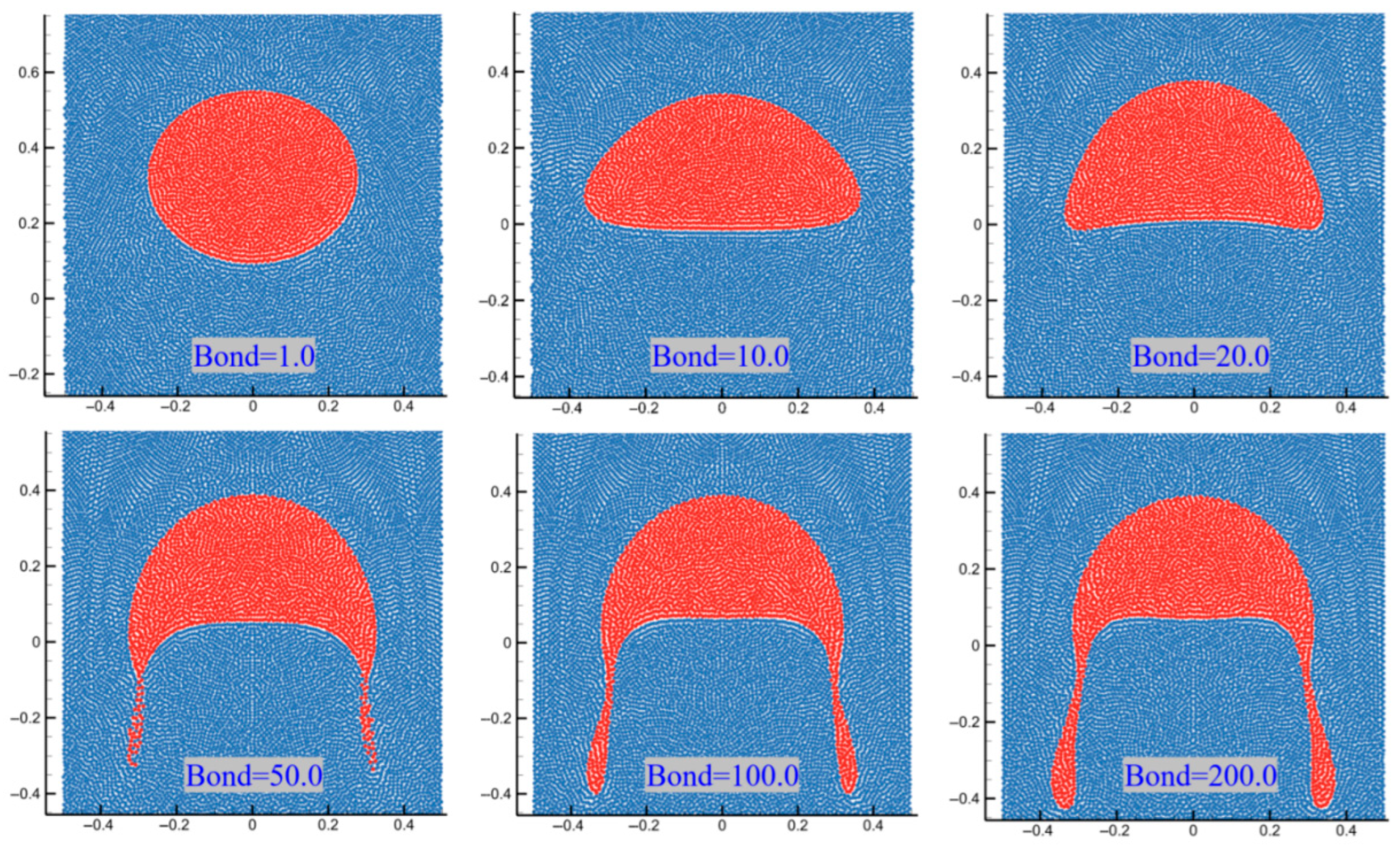

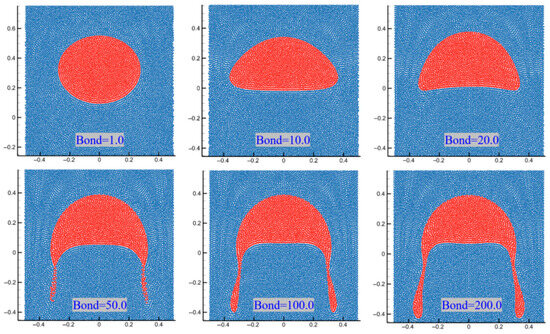

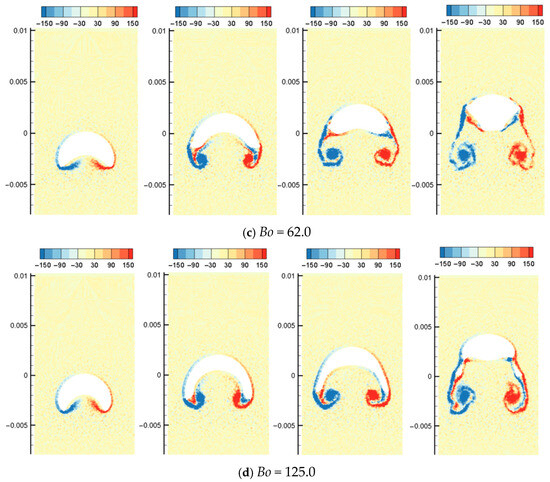

As shown in Figure 11, the initial bubble is circular and begins to rise due to buoyancy. During the initial acceleration stage, the bubble gradually deforms, taking on an overall shape that is concave upwards. As the velocity continues to increase, the resistance to rising due to viscosity also increases, eventually reaching a stable value. During the rising process, the greater the rising velocity, the more severe the deformation of the bubble’s shape. Surface tension acts to restore the bubble’s deformation, maintaining a relatively stable morphology. It can be considered that the morphology of the bubble after it stabilizes is related to surface tension. We introduce a dimensionless number, the Bond number, to analyze the effect of surface tension on the bubble’s rising behavior. The smaller the Bond number, the greater the effect of surface tension. Figure 12 presents the simulation results of bubble morphology under different Bond numbers. As shown, as the Bond number increases, the deformation of the bubble becomes more severe; when the Bond number exceeds 50, the rising bubble will experience wake detachment.

Figure 12.

Simulation results of the morphology of floating bubbles stabilized with different bond numbers.

4.4. Two Bubbles Rising and Coalescence

Table 4 shows the parameters selected for the rising and coalescence of two bubbles. By adjusting the value of the surface tension coefficient, different Bond numbers can be obtained. Figure 13 shows the simulation results of the rising and coalescence of two coaxial bubbles, and Figure 14 shows the simulation results of the rising and coalescence of two eccentric bubbles. The initial vertical distance between the two bubbles is 5.0 mm. At the beginning of the calculation, two bubbles float up under the action of buoyancy. The wake of the upper bubble produces an adsorption effect on the lower bubble. At low Bond numbers, the lower bubble presents a nearly triangular shape. As the Bond number increases, as shown in Figure 13c,d, the lower bubble presents a horseshoe shape at time 6.79. The adsorption effect of the upper bubble makes the lower bubble rise faster than the upper bubble, and finally, the two bubbles merge at time 13.51. With a lower Bond number, as shown in Figure 13a,b, at time 16.83, two bubbles merge into a bubble with a larger diameter, and the Bond number also increases. Therefore, the overall floating topography presents an approximately triangular shape.

Table 4.

Physical parameters for two rising bubbles.

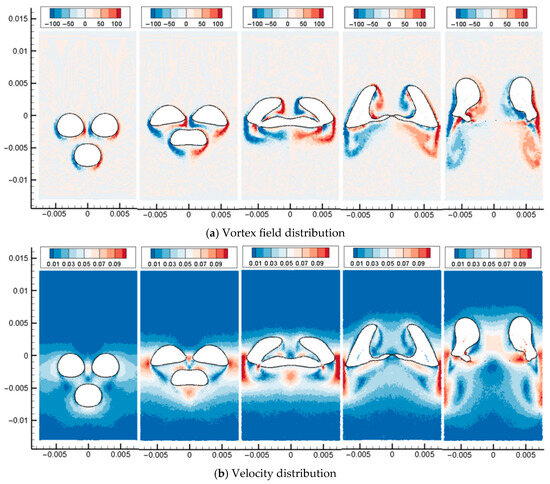

Figure 13.

Results of the coalescence of two coaxial bubbles during the rising process (density ratio = 10.0).

Figure 14.

Simulation results of the inclined coalescence process of two bubbles.

Figure 14 shows the bubble morphology and vortex structure of the inclined coalescence of two floating bubbles. Due to the adsorption of the upper bubble to the lower bubble, the lower bubble accelerates and forms a trailing edge. Due to the movement of the trailing edge (Figure 14a,c) or shedding (Figure 14c,d), a shedding vortex is formed at the lower right of the lower bubble.

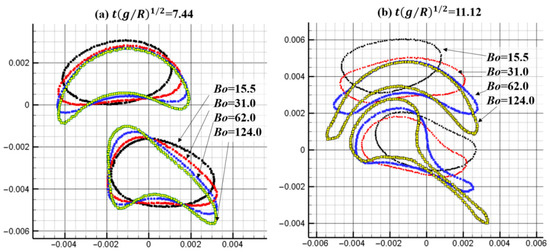

It can be seen from Figure 15 that as the bond number increases, the deformation of the two bubbles becomes more obvious. The upper bubble produces an adsorption effect on the lower bubble so that the top of the lower bubble stretches along the upper left, and the bubble moves to the upper left. As the bond number increases, the trailing edge of the lower bubble becomes more obvious.

Figure 15.

Comparison of bubble profiles for different Bond numbers.

The multiphase flow SPH model is then used to simulate the floating and coalescence process of three bubbles. At the initial moment, the computational domain contains three bubbles with the same diameter, two of which are located above, and one bubble is located below the center points of the two bubbles. After the calculation starts, the three bubbles move upward under the action of buoyancy. As shown in Figure 15, the upper two bubbles each produce an outward turning angular velocity under the action of the lower bubble. The two upper bubbles adsorb the lower bubbles, making the lower bubbles flat. As the two upper bubbles rotate and the lower bubble is further elongated under the action of adsorption, the lower end of the upper bubble contacts and merges with the two sides of the lower bubble. Since the overturning of the bubble makes the upper two bubbles have a tendency to move away from each other, the lower bubble is gradually torn into two bubbles under the action of the two bubbles. Finally, the three bubbles merge to form two separated bubbles and continue to move upward under the action of buoyancy, surface tension, and viscous force.

5. Application to Oil–Water–Gas Bubbly Flows

5.1. Single Oil Droplet Rising in Still Water

The two non-dimensional numbers also determine the bubble terminal shape and the Reynolds number. Most of the previous studies focused on the bubble rising process under the condition of a high-density ratio (such as liquid–air). The results show that the morphology of rising bubbles is mainly affected by the surface tension, while the density ratio has little effect on the surface morphology when it is in a certain range (i.e., ). This section is concerned with the rising process of oil droplets in water. The material parameters are listed in Table 5. In petroleum engineering, the oil from the formation is usually a mixture of oil, gas, and water. The gas is usually pumped out and lifted separately, and the remaining mixture of oil and water is lifted through another lift channel. When the moisture content of crude oil is very high, the oil droplets generally exist in the water in the form of a dispersed phase. At this time, due to the influence of the density difference, the oil droplets float up in the water under the action of buoyancy.

Table 5.

Material parameters for single oil-drop rising (effect of Bond number).

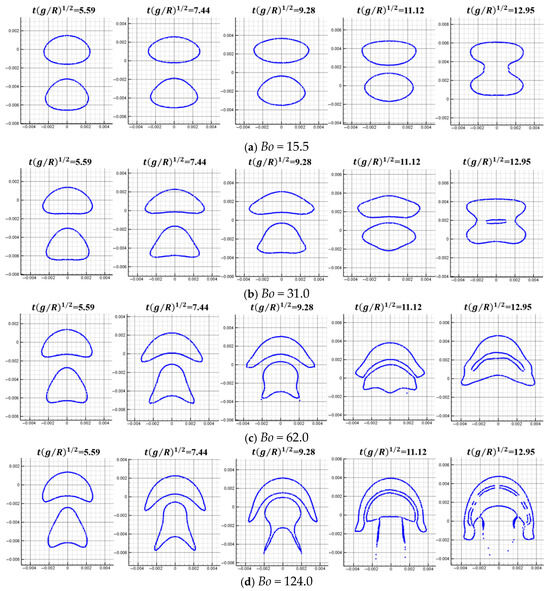

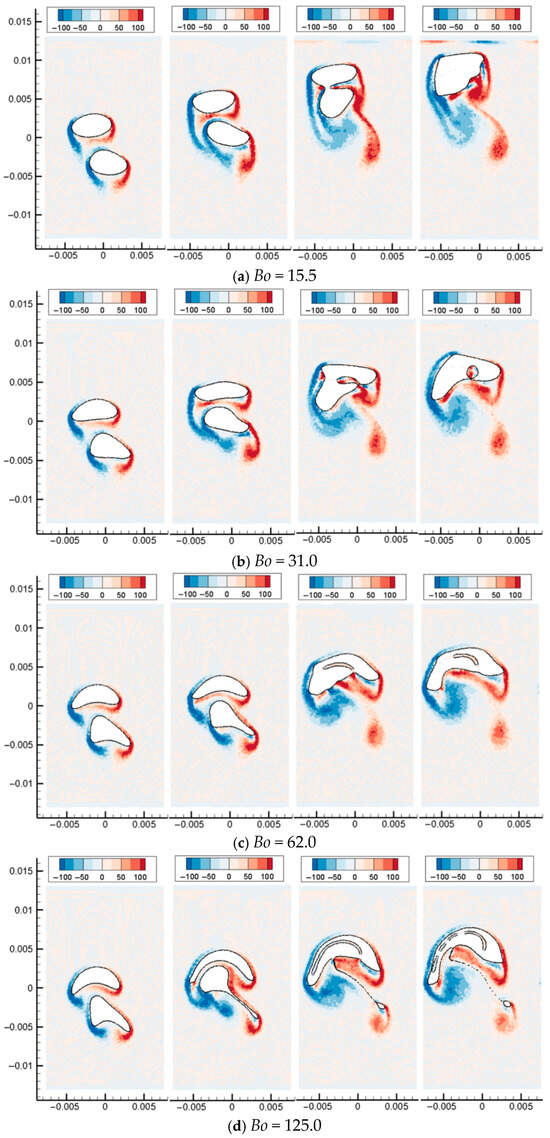

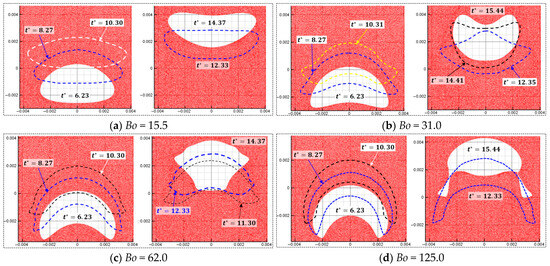

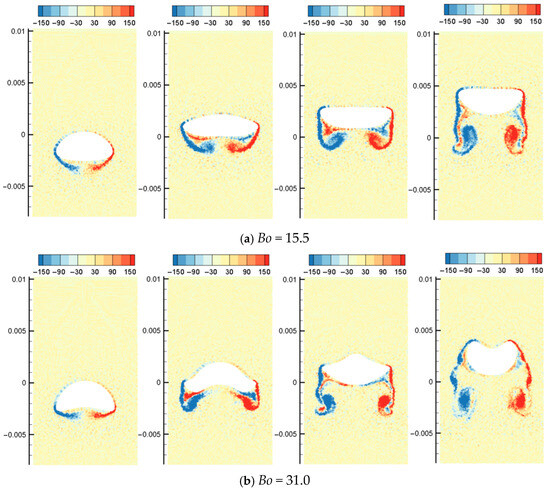

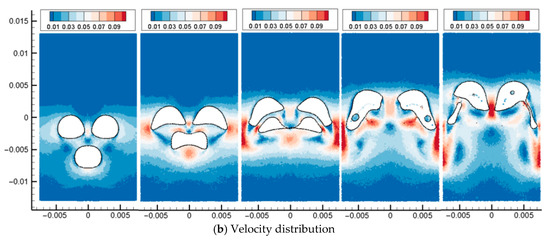

The multiphase SPH model is used to simulate the upward rising process of oil droplets in still water, where the viscosity, surface tension, and gravity dominate the process. The physical parameters of the heavy phase are set according to water, having a density of 1000 kg/m3 and a viscosity of 0.001 Pas. The parameters of the light phase are set according to oil with a density of 800 kg/m3 and a viscosity of 0.01 Pas. Thus, the density ratio is 1.25, and the viscosity ratio is 0.1. The rising patterns for various Bo numbers (15.5, 31.0, 62.0, and 125.0) are predicted and analyzed, as shown in Figure 16.

Figure 16.

SPH results of rising patterns of single oil droplets for various Bo numbers.

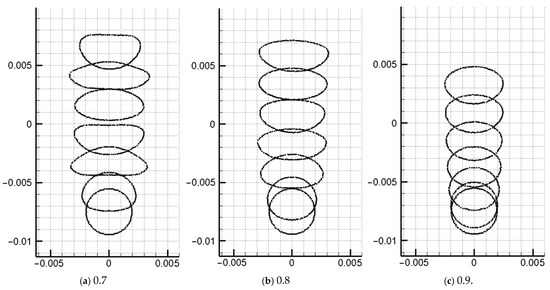

Figure 16 shows the simulation results of the morphology evolution of oil droplets under different Bond numbers. Figure 17 shows the vorticity distribution at different times during the rising process of oil droplets. Figure 18 shows droplet morphologies for three density ratios between oil and water. At small Bond numbers, the effect of surface tension is obvious, causing the oil droplets to flatten during the rising process. As the Bond number increases, the droplet deforms more, and the trailing edge of the droplet becomes sharper (). The selected density ratio between water and oil is 1.25, which is far less than the density ratio that was selected to study the bubble rising in the literature. Researchers have pointed out that when the density ratio is greater than 10.0, the density ratio has little effect on the morphology of bubbles. In addition, the bubble rising under the high-density ratio can reach a stable morphology, which is different from the situation of oil droplets simulated in this paper. Due to the small density ratio of oil and water, surface tension and buoyancy compete in the rising process. The buoyancy deforms the oil droplets at the initial moment, and the trailing edge is generated (). The sharpness of the trailing edge increases with the Bond number. The large curvature of the trailing edge increases the surface tension force. Hence, the deformed oil droplet has a tendency to shrink toward the center, and this tendency and the bulk velocity have a combined effect on the transient morphology of the oil droplet.

Figure 17.

SPH results of the rising process of single oil droplets for various Bo numbers ().

Figure 18.

Comparison of droplet morphologies for three density ratios between oil and water (Bo = 15.0).

As shown in Figure 16a, surface tension inhibits the initial deformation of the oil droplets, and subsequent droplet oscillation is not apparent. As shown in Figure 16b, at , the surface tension at the trailing edge provides additional driving force for upward movement. The upward velocity of the trailing edge is greater than the bulk velocity of the oil droplets (). As the Bond number further increases, as shown in Figure 16c, although the trailing edge of the oil droplets at the initial moment becomes sharper, the surface tension coefficient also decreases, thus weakening the surface tension effect in the process of rising. The morphology of the oil droplets obtained at is irregular and not smooth. For Bo = 125, the surface tension is not enough to make the oil droplet evolve from the sharper trailing edge to the quasi-circular shape. Finally, the trailing edge detaches from the oil droplet because of the lower velocity and the capillary force. For each case of Bond numbers, the rising oil droplet forms an angular vortex at the time , and the wake generated by the vortex shed will affect the interaction process among multiple oil droplets, such as the adsorption effect of oil droplets on adjacent oil droplets.

Crude oil viscosity is an important material parameter in petroleum engineering. The viscosity of crude oil is affected by temperature, pressure, and composition and has a wide span ranging from 1 mPas to 10,000 mPas. Compared to the oil phase, the physical properties of water are more consistent. Therefore, in this section, the influence of oil phase viscosity on the floating movement of oil droplets is studied by changing the oil phase viscosity. Three oil phase viscosities are set, respectively, to 0.1, 0.01, and 0.005. Considering the low Bo number (Bo = 15.5) and high Bo number (Bo = 125.0), the floating speed and morphological evolution of oil droplets are obtained by a simulation process. The viscosity of the oil phase has little effect on the buoyancy speed and the buoyancy distance.

The density of crude oil is slightly lower than that of water, and the density ratio of water to oil is much smaller than that of water to gas. Therefore, in the field of oil–water separation, the density difference or relative density is generally used to describe the density relationship between oil and water. Relative density is the ratio of the density of crude oil to water. Under normal temperature and pressure conditions, the density of water is about 100 kg/m3. According to the density of oil, oil can be divided into heavy crude oil and light crude oil, and the corresponding relative density ranges are 0.9~1.0 and 0.75~0.9, respectively.

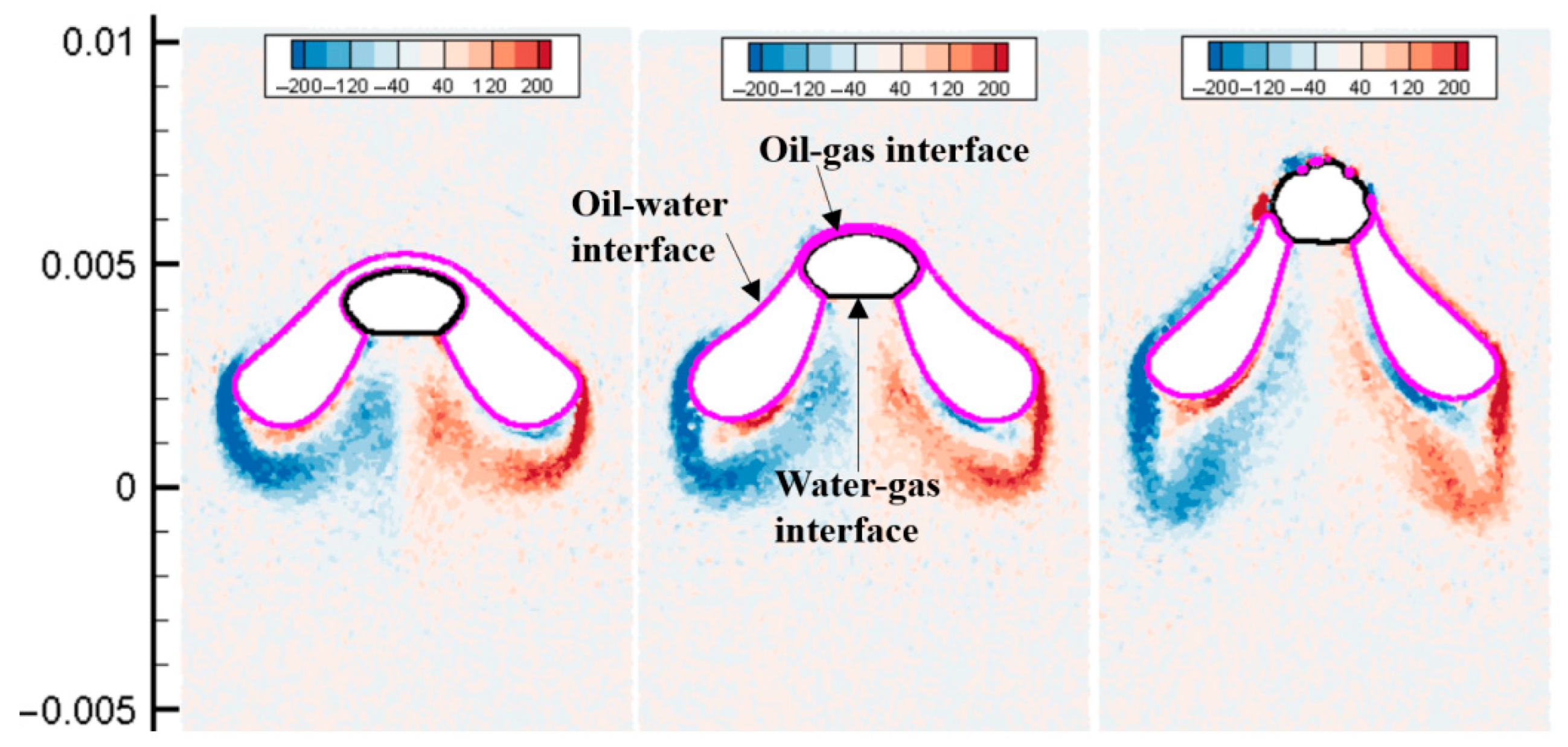

5.2. Oil Droplets Rising and Coalescence

5.2.1. Three Oil Droplets

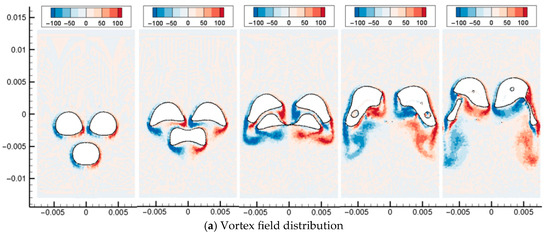

In this section, the multiphase flow SPH model is used to simulate the floating and coalescence process of three bubbles. At the initial moment, the computational domain contains three oil droplets with the same diameter, two of which are located above, and one oil drop is located below the center points of the two oil droplets. After the calculation starts, the three oil droplets move upward under the action of buoyancy. As shown in Figure 19 and Figure 20, the upper two oil droplets each produce an outward turning angular velocity under the action of the lower oil droplet. The two upper oil droplets adsorb the lower oil droplets, making the lower oil droplets flat. As the two upper oil droplets rotate and the lower oil droplet is further elongated under the action of adsorption, the lower end of the upper oil droplet contacts and merges with the two sides of the lower oil droplet. Since the overturning of the oil droplet makes the upper two oil droplets have a tendency to move away from each other, the lower oil droplet is gradually torn into two oil droplets under the action of the two oil droplets. Finally, the three oil droplets merge to form two separated oil droplets and continue to move upward under the action of buoyancy, surface tension, and viscous force.

Figure 19.

Three bubbles rising and coalescence (Bo = 31).

Figure 20.

Three bubbles rising and coalescence (Bo = 62).

5.2.2. A Set of Oil Droplets

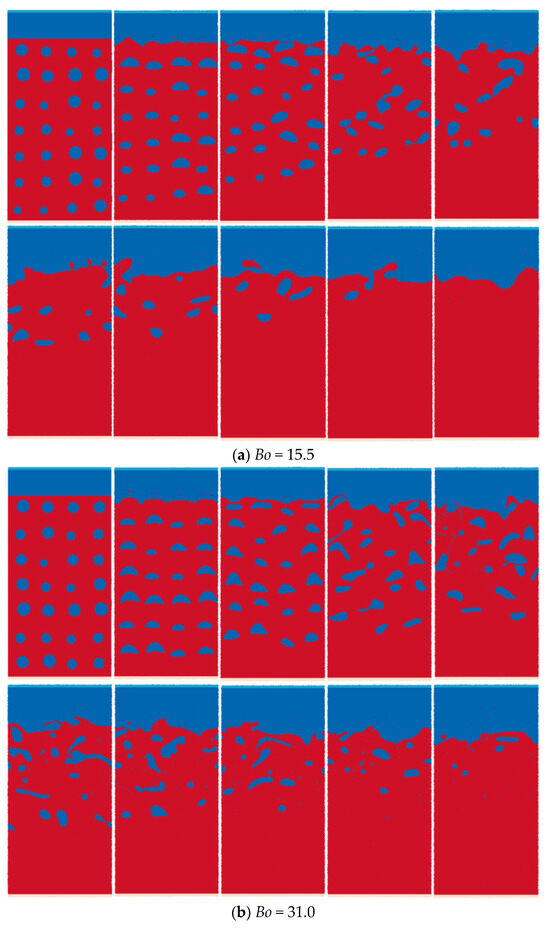

Considering that the phase exists in the bubble–water mixture in the form of dispersed bubbles, the size and distribution of the bubbles need to be described in order to establish the numerical model. Assuming that the bubble is initially spherical, the initial position of a single bubble can be described by the center of the sphere and the particle size. Hence, for a computational domain containing a large number of bubbles, the geometric description of the bubble distribution can be obtained. Given a random number, under the premise of uniform distribution, the initial position and radius of the bubbles are adjusted. In this section, the multiphase SPH model is used to simulate the separation process of dispersed bubbles in water.

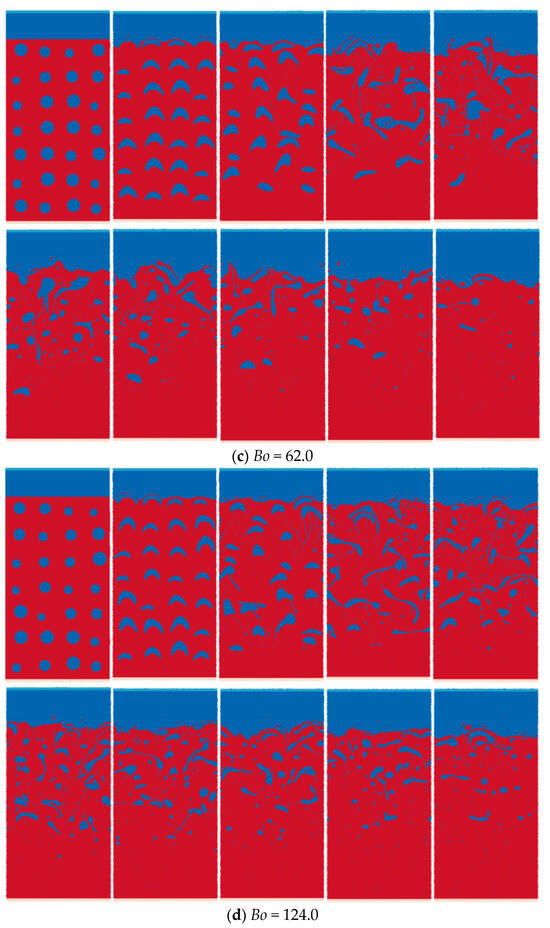

At the initial moment, a set of bubbles with a certain size and spatial distribution is generated in the computational domain. The density of is set to 100 kg/m3, and the density of water is set to 1000 kg/m3. The dynamic viscosity of is set to 0.0065, and the viscosity of water is 0.007. The initial particle spacing is 0.01, five layers of dummy particles are used for the upper and lower solid wall boundaries, and the total number of particles is 80,000. Periodic boundaries are used on the left and right sides of the computational domain.

As shown in Figure 21, a set of bubbles is arranged in the static water at the initial moment. The reference diameter of the bubble is 0.003, and the diameter and position of the bubble are randomly processed on the basis of the reference diameter. The bubbles move upward under the action of buoyancy, and after a certain period of time, they finally rise to the water interface and dissolve in the upper layer. When the bubbles float up, they will deform and coalesce with different bubbles. With the increase in the bond number, the interaction effect between bubbles gradually increases, making the bubble–water separation process slower.

Figure 21.

Simulation results of rising process of a set of randomly distributed bubbles.

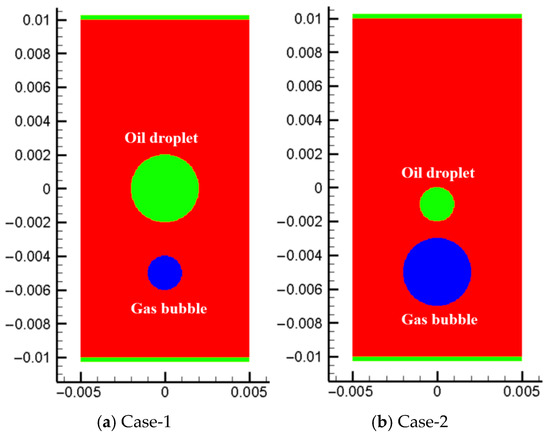

5.3. Interaction Between Single Oil Droplets and Gas Bubbles

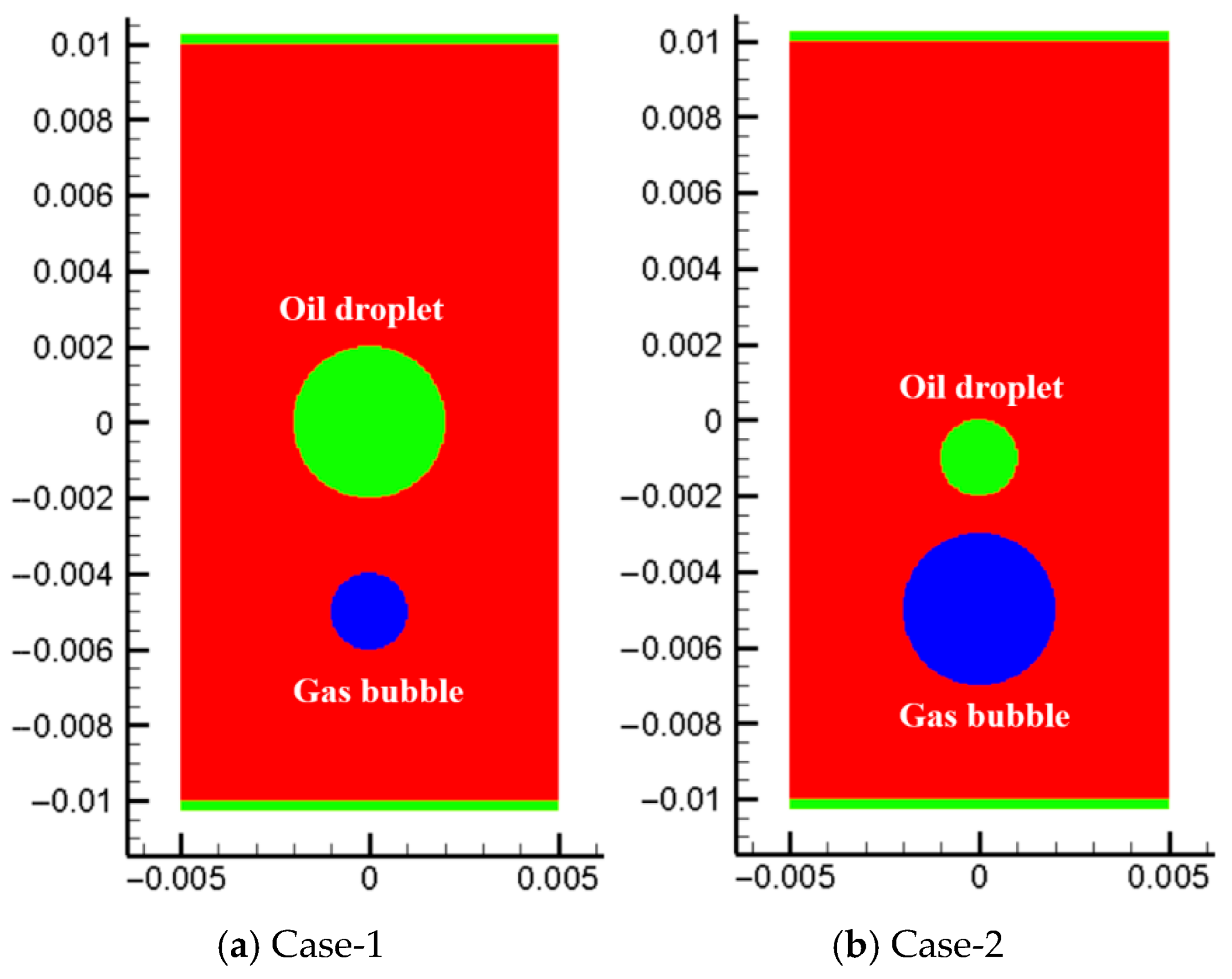

In the three-phase flow containing air bubbles and oil droplets, there exist interactions between air bubbles and oil droplets. In this paper, bubbles and oil droplets are regarded as two incompatible fluids. Based on this hypothesis, the interaction behavior of bubbles and oil droplets in the process of rising in water is investigated. This section considers the rising process of a single oil drop and a single bubble. Figure 22 shows the model parameters used in the two cases. In case-1, the diameters of bubbles and oil droplets are 0.002 m and 0.004 m, respectively, and the initial vertical distance between the two is 0.005 m. In calculation example 2, the diameters of bubbles and oil droplets are 0.004 m and 0.002 m, respectively, and the initial vertical distance between the two is 0.004 m. The particle spacing used in the simulation is 0.00005 m, and the number of particles is 80,000.

Figure 22.

Model parameters of single oil droplet and gas bubble.

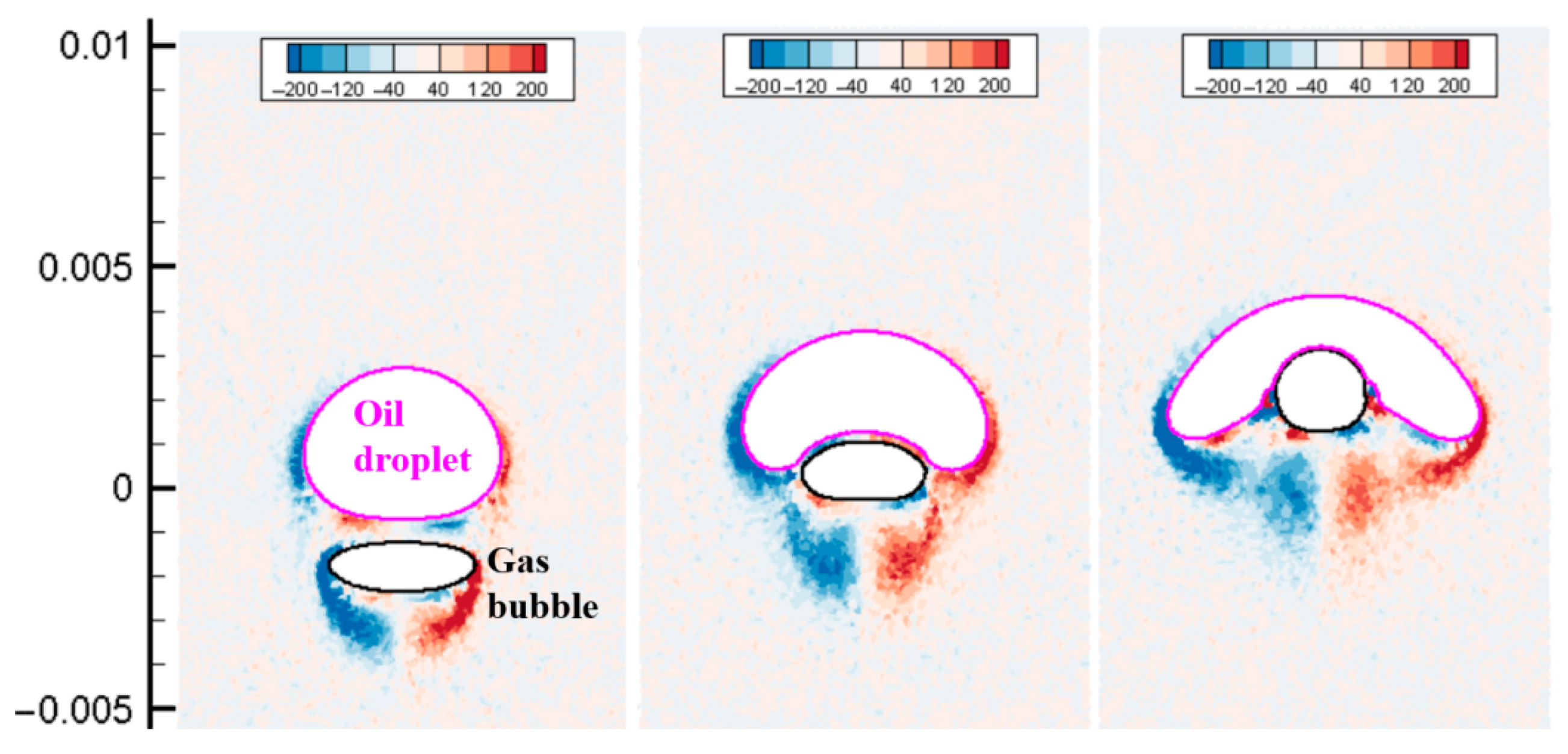

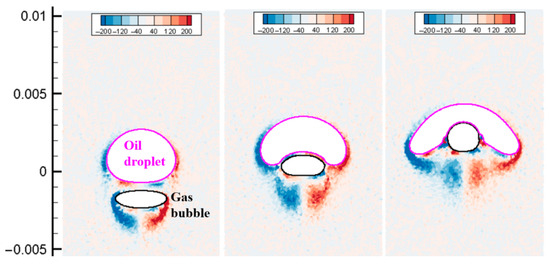

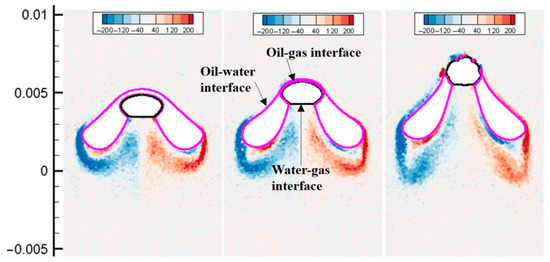

As shown in Figure 23, at the initial moment, the bubbles with the smaller diameter are located below the oil droplets with the larger diameter. Because the bubbles rise faster, the bubbles quickly contact the oil droplets. Oil droplets deform under the action of bubbles, and a certain contact angle is gradually formed between oil droplets, bubbles, and water. The bubbles gradually enter the inside of the oil droplet, and the oil droplet is forcibly separated into two parts. Eventually, the bubbles pass through the oil drop and continue to float up, and the oil drop is cut into two parts. As shown in the figure, particle penetration occurs in the three-phase simulation. When the bubbles pass through the oil droplets, the oil film gradually becomes thinner, and a certain amount of oil phase particles are interspersed between the upper surface of the bubbles and the water, making the shape of the bubbles become irregular. The dotted line shows the speed curves of bubbles and oil droplets floating alone. It can be seen from the figure that the floating speed of oil droplets under the action of air bubbles is higher than when floating alone. However, as the bubbles pass through the oil droplets and the oil droplets are divided into two, the overall floating speed of the oil droplets decreases significantly. The floating speed of the bubble is not much different from the speed when floating alone; the difference is that the fluctuation degree of the bubble speed is weakened. This is because after the bubbles enter the oil droplets, the wrapping effect of the oil droplets limits the vibration of the bubble shape.

Figure 23.

Interaction of the rising oil droplet and bubble (case-1).

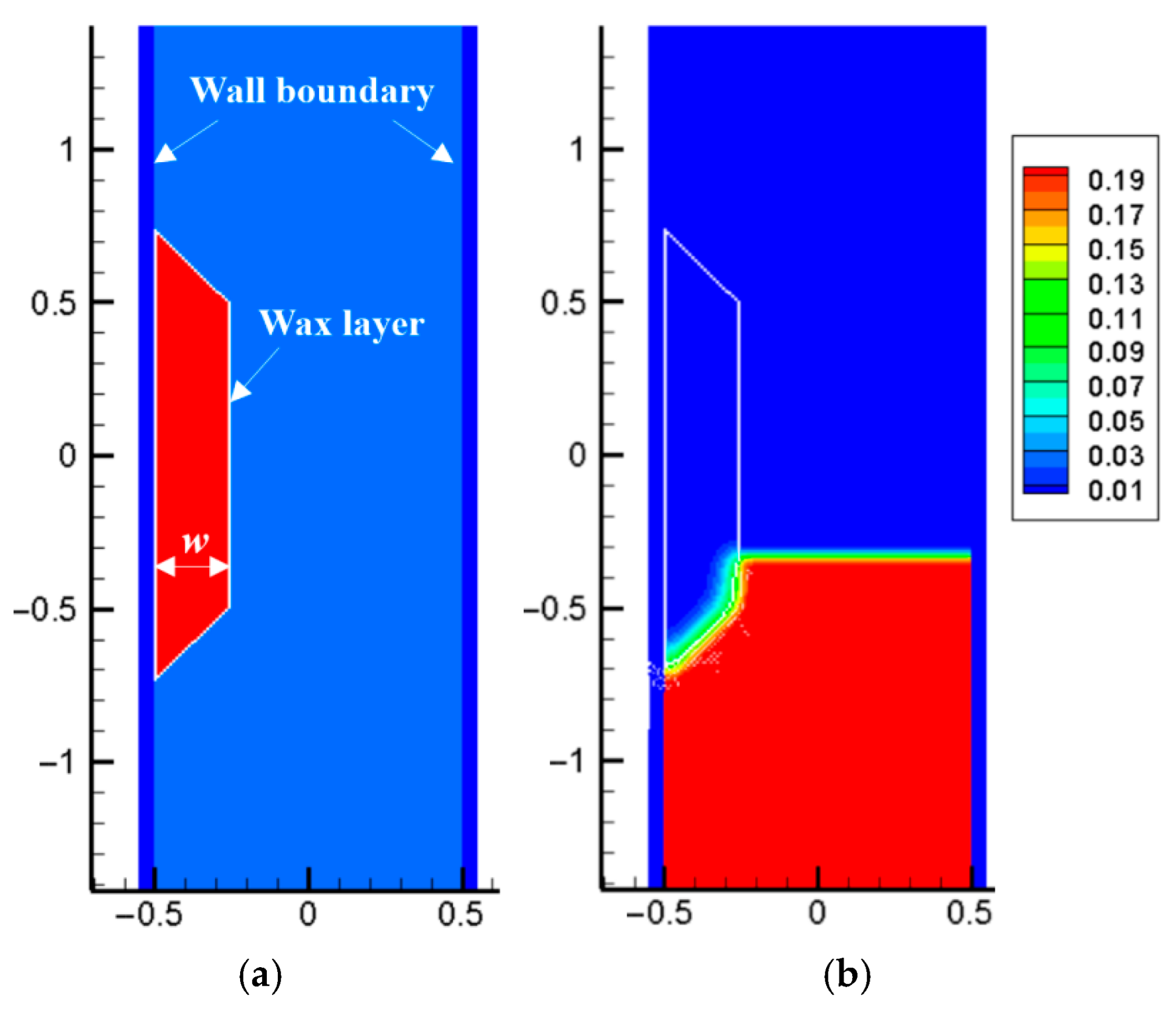

6. Extension to Wax Removal Process

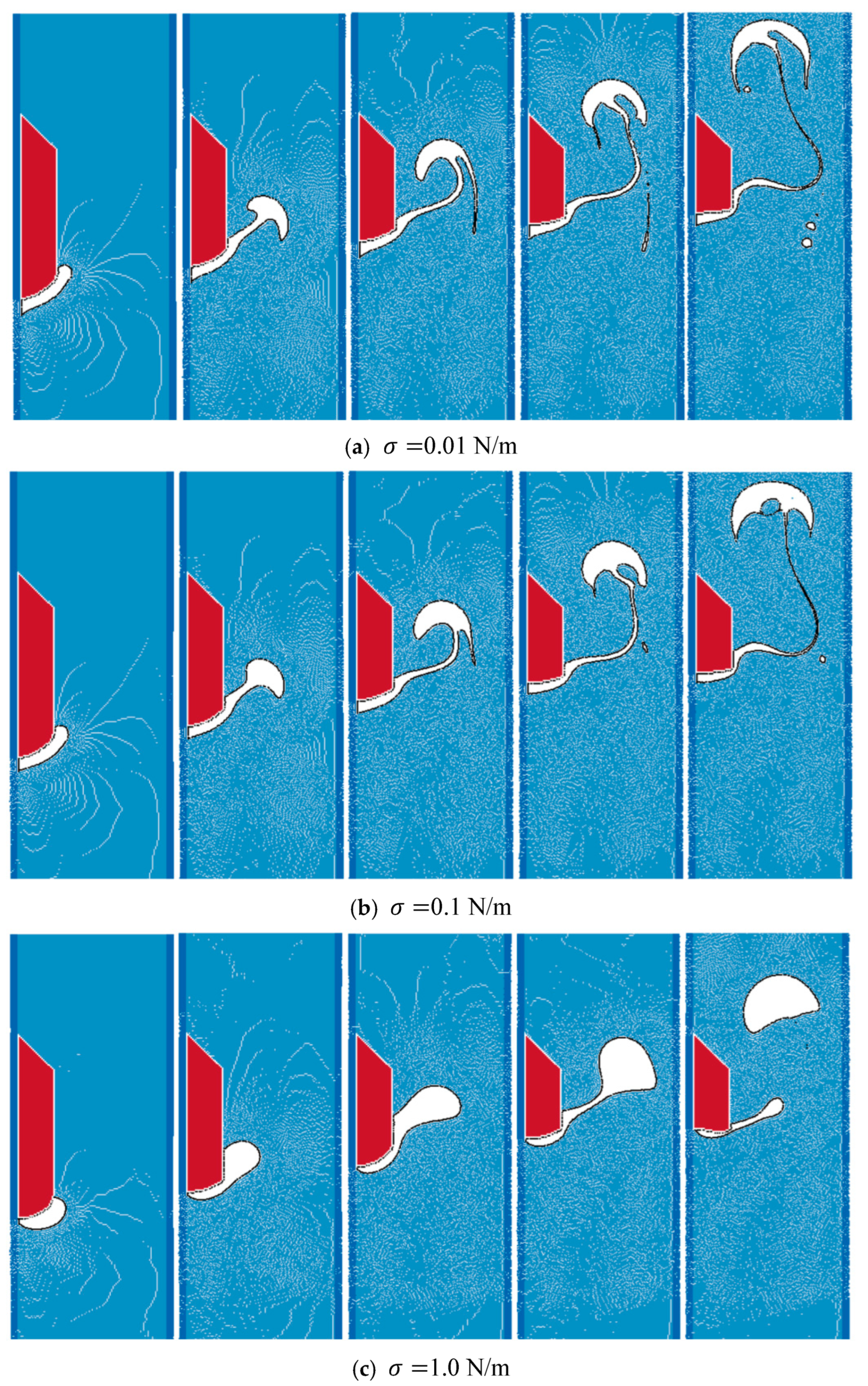

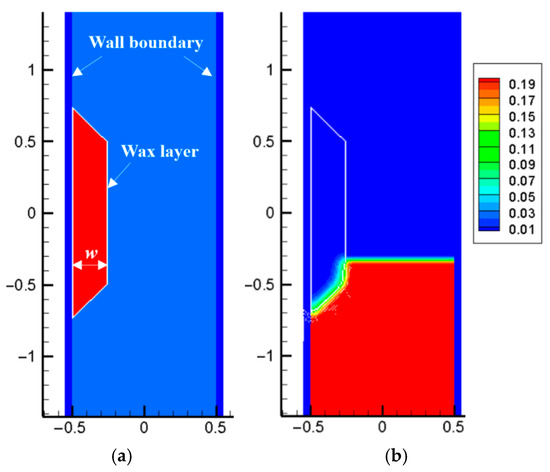

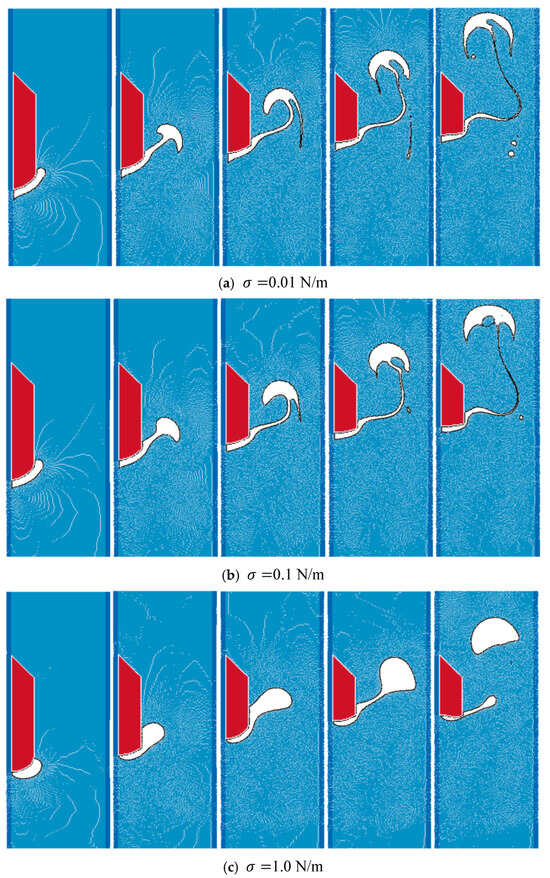

This study employs the multiphase SPH framework to simulate the phase transition of a solid wax layer under thermal loading. The computational model integrates fluid dynamics and thermal solvers, with initial temperature conditions illustrated in Figure 24. A rectangular wax deposit is initialized on a rigid substrate. The solid wax is assigned an initial temperature of 0.0 K, with a phase transition threshold set at 0.2 K. Initially, the solid wax layer (0.0 K) is on a rigid substrate with surrounding water at 0.2 K; boundary conditions include no-slip rigid walls (substrate and top/bottom boundaries) with constant temperature and periodic side boundaries. Material properties include a thermal conductivity of 1.0 W/m/K and a specific heat capacity of 20.0 J/kg/K for the wax. The density contrast between water (10.0 kg/m3) and wax (1.0 g/cm3) yields a ratio of 10:1, while both phases share a dynamic viscosity of 0.2 Pas. The simulation domain comprises 44,100 particles (40,000 ising fluid/solid phases; 4100 as boundary markers), with surface tension coefficients tested at 1.0, 0.1, and 0.01 N/m to assess interfacial stability.

Figure 24.

Initial model of wax melting.

Figure 25 demonstrates the thermally driven melting process. Heat conduction elevates the wax temperature, initiating localized phase change at the substrate interface. As molten wax accumulates, its motion is governed by competing forces: Buoyancy drives upward migration, while surface tension preserves interfacial integrity against viscous dissipation. Progressive droplet growth and detachment are observed, with buoyant wax parcels ascending through the continuous phase. The interplay of these forces dictates the transient morphology of the molten phase. Notably, convective heat transfer induced by rising droplets enhances thermal redistribution, accelerating the overall melting rate. This coupling between hydrodynamic and thermodynamic phenomena underscores the model’s capability to resolve multiphysics interactions in phase-change-dominated systems.

Figure 25.

Effect of surface tension on interface behaviors of melted wax.

7. Summary

In this study, the multiphase SPH model is established and is applied to simulate viscous bubbly flows containing oil, water, and gas, three fluid phases, where dispersed oil droplets and gas bubbles rising in water can cause complex and unstable interface behaviors. The model is validated by several benchmark examples, including square droplet deformation, single bubble rising, and two bubble rising. The validated model is then used to investigate the interface behaviors of oil–water–gas bubbly flows. The potential use of the present model on the wax removal process is also presented in this study by incorporating the model with the thermal dynamics and phase change models. Some of the findings are summarized as follows:

(1) The interface repulsive force is effective in preventing the interface particles from penetrating the interface. Both the conditions of the two phases and three phases are considered. However, proper selection of the parameter is essential to obtain correct results and maintain the stability of the interface, especially for a large density ratio and three fluid phases. For the simulation in this study, the parameter a = 0.02 is shown to be effective in preventing the penetration of particles and obtaining a good convergence of the numerical simulation. The Laplace pressure difference and pressure noise are obtained by testing different smoothing lengths, and finally, 1.4 Dx is selected as the value of smoothing length. Sensitivity to key parameters requires careful tuning and increased computational cost for large-scale simulations with numerous particles.

(2) A geometric processing method for monitoring the morphology of bubbles and droplets is proposed. By detecting the single-layer boundary particles of the bubble, the transient bubble contour evolution result is obtained. The calculation examples of bubble floating and oil droplet fusion show that the proposed method can not only accurately restore the complete bubble contour but also capture wakes, fusion boundaries, satellite droplets, etc. caused by complex interface behavior.

(3) The rising process of oil droplets and bubbles under different bond numbers (Bo = 15.5, 31, 62, 124) is investigated. Results show that the bond number has a significant influence on the rising pattern of the oil droplet, while the viscosity ratio and density difference between oil and water have little effect.

(4) The multiphase flow model proposed in this paper can simulate the transient behaviors of mutual interference, coalescence, and fragmentation caused by the floating process of a large number of oil droplets, which is superior to the results of current mature commercial software. Through the floating simulation of a large number of oil droplets, the oil droplets finally mixed into the upper oil layer, realizing the transient simulation of the oil–water separation process, and obtaining a stable oil–water interface. In oil–water separation, it simulates the rising and coalescence of numerous oil droplets, aiding in optimizing separator design and efficiency.

(5) In this paper, the thermodynamic model and phase transition model are introduced into the multiphase flow model, and the wax layer melting process under the action of temperature gradient is simulated for the first time. The wax layer, which is initially solid, gradually melts as the temperature increases, and the heat conduction proceeds. The melted liquid wax forms a new interface with the surrounding water and moves upward under the action of interfacial tension and buoyancy and finally forms separated droplets, completing the wax melting and clearing process. The model captures wax layer melting and droplet detachment, providing insights for pipeline cleaning strategies (e.g., heating parameter optimization).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.L. and L.S.; methodology, Z.L.; software, L.S.; validation, X.Z., Y.L. and Y.W.; formal analysis, Y.W.; investigation, Q.L.; resources, Q.L.; data curation, L.S.; writing—original draft preparation, L.S.; writing—review and editing, Z.L.; visualization, Z.L.; supervision, Y.L.; project administration, X.Z.; funding acquisition, Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Qingzhen Li was employed by the company Shale Oil Project Department of Shengli Oilfield. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Yu, H.; Yang, S.; Wang, H. Investigation of multi-inlet arrangement effect on mesoscale bubble dynamics in the gas–liquid-solid reactor via VOF-DEM. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2024, 301, 120710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cai, J.; Li, Q. Numerical simulation of large bubble-rising behavior in nuclear reactor using diffuse interface method. Int. J. Energy Res. 2018, 42, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhondayi, C. Flotation froth phase bubble size measurement. Miner. Process. Extr. Metall. Rev. 2022, 43, 251–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.L.; Colagrossi, A.; Wang, P.P.; Zhang, A.M. An accurate and robust axisymmetric SPH method based on Riemann solver with applications in ocean engineering. Ocean Eng. 2022, 244, 110369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laupsien, D.; Le Men, C.; Cockx, A.; Liné, A. Effects of liquid viscosity and bubble size distribution on bubble plume hydrodynamics. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2022, 180, 451–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chekifi, T. Computational study of droplet breakup in a trapped channel configuration using volume of fluid method. Flow Meas. Instrum. 2018, 59, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szewc, K.; Pozorski, J.; Minier, J.P. Simulations of single bubbles rising through viscous liquids using smoothed particle hydrodynamics. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 2013, 50, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chekifi, T. Droplet Breakup Regime in a Cross-Junction Device with Lateral Obstacles. Fluid Dyn. Mater. Process. 2019, 15, 545–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, J.J. Enhanced oil recovery in shale reservoirs by gas injection. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2015, 22, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazari, S.; Hassanzadeh, A.; He, Y.; Khoshdast, H.; Kowalczuk, P.B. Recent developments in generation, detection and application of nanobubbles in flotation. Minerals 2022, 12, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chekifi, T.; Boukraa, M.; Aissani, M. DNS using CLSVOF method of single micro-bubble breakup and dynamics in flow focusing. J. Vis. 2021, 24, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chekifi, T.; Dennai, B.; Khelfaoui, R. Computational Investigation of Droplets Behaviour inside Passive Microfluidic Oscillator. Fluid Dyn. Mater. Process. 2017, 13, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grenier, N.; Le Touzé, D.; Colagrossi, A.; Antuono, M.; Colicchio, G. Viscous bubbly flows simulation with an interface SPH model. Ocean Eng. 2013, 69, 88–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chekifi, T.; Dennai, B.; Khelfaoui, R. Numerical simulation of droplet breakup, splitting and sorting in a microfluidic device. Fluid Dyn. Mater. Process. 2015, 11, 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulbah, C.; Kang, C.; Mao, N.; Zhang, W.; Shaikh, A.R.; Teng, S. A review of VOF methods for simulating bubble dynamics. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2022, 154, 104478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, K.L.; Chen, Z.J. Simulation of bubble dynamics in a microchannel using a front-tracking method. Comput. Math. Appl. 2014, 67, 290–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.X.; Sun, L.; Yu, P. A novel interface method for two-dimensional multiphase SPH: Interface detection and surface tension formulation. J. Comput. Phys. 2021, 431, 110119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.W.; Hao, G.N.; Yu, R. Two-dimensional smoothed particle hydrodynamics (SPH) simulation of multiphase melting flows and associated interface behavior. Eng. Appl. Comput. Fluid Mech. 2022, 16, 588–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, B.L.; Nguyen-Xuan, H.; Wahab, M.A. An effective approach for VARANS-VOF modelling interactions of wave and perforated breakwater using gradient boosting decision tree algorithm. Ocean Eng. 2023, 268, 113398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zong, Z.; Liu, M.B.; Zou, L.; Li, H.T.; Shu, C. An SPH model for multiphase flows with complex interfaces and large density differences. J. Comput. Phys. 2015, 283, 169–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.M.; Sun, P.N.; Ming, F.R. An SPH modeling of bubble rising and coalescing in three dimensions. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2015, 294, 189–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Liu, X. Improved mesh-free SPH approach for loose top coal caving modeling. Particuology 2024, 95, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.W.; Hao, G.N.; Liu, Y. Efficient mesh-free modeling of liquid droplet impact on elastic surfaces. Eng. Comput. 2023, 39, 3441–3471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.N.; Pilloton, C.; Antuono, M.; Colagrossi, A. Inclusion of an acoustic damper term in weakly-compressible SPH models. J. Comput. Phys. 2023, 483, 112056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Hu, C.; An, Y.; Shi, C.; Feng, C.; Wang, H.; Liu, Q.; Wang, X. Numerical simulation of the large-scale Huangtian (China) landslide-generated impulse waves by a GPU-accelerated three-dimensional soil–water coupled SPH model. Water Resour. Res. 2023, 59, e2022WR034157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Sun, Y.; An, Y.; Shi, C.; Feng, C.; Liu, Q.; Yang, X.; Wang, X. Three-dimensional simulations of large-scale long run-out landslides with a GPU-accelerated elasto-plastic SPH model. Eng. Anal. Bound. Elem. 2022, 145, 132–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Q.; Chen, R.; Guo, K.; Tian, W.; Qiu, S.; Su, G.H. An enhanced moving particle semi-implicit method for simulation of incompressible fluid flow and fluid-structure interaction. Comput. Math. Appl. 2023, 145, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, G.; Feng, S.; Sun, Z. Simulating multi-phase sloshing flows with the SPH method. Appl. Ocean Res. 2022, 118, 102989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Zhang, H.; Qian, Z.; Liu, M. Smoothed-Interface SPH Model for Multiphase Fluid-Structure Interaction. J. Comput. Phys. 2024, 518, 113336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.K.; Zhang, A.M.; Ming, F.R.; Sun, P.N.; Peng, Y.X. An axisymmetric multiphase SPH model for the simulation of rising bubble. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2020, 366, 113039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S.; Franc, J.P.; Ghigliotti, G.; Fivel, M. SPH modelling of a cavitation bubble collapse near an elasto-visco-plastic material. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2019, 125, 420–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Liu, X.; Dong, X.; Yin, L.; Cheng, Z. A volume-adaptive mesh-free model for FSI Simulation of cavitation erosion with bubble collapse. Comput. Part. Mech. 2024, 11, 2325–2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmat, A.; Tofighi, N.; Yildiz, M. Numerical simulation of the electrohydrodynamic effects on bubble rising using the SPH method. Int. J. Heat Fluid Flow 2016, 62, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patino-Narino, E.A.; Galvis, A.F.; Sollero, P.; Pavanello, R.; Moshkalev, S.A. A consistent multiphase SPH approximation for bubble rising with moderate Reynolds numbers. Eng. Anal. Bound. Elem. 2019, 105, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cen, C.; Fourtakas, G.; Lind, S.; Rogers, B.D. A single-phase GPU-accelerated surface tension model using SPH. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2024, 295, 109012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.X.; Bilotta, G.; Yuan, Q.E.; Gong, Z.X.; Liu, H. Multi-GPU multi-resolution SPH framework towards massive hydrodynamics simulations and its applications in high-speed water entry. J. Comput. Phys. 2023, 490, 112339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.S.; Sun, P.N.; Xu, Y.; Lyu, H.G.; Geng, L.M. Numerical studies of complex fluid-solid interactions with a six degrees of freedom quaternion-based solver in the SPH framework. Ocean Eng. 2024, 291, 116484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, F.R.; Sun, P.N.; Zhang, A.M. Numerical investigation of rising bubbles bursting at a free surface through a multiphase SPH model. Meccanica 2017, 52, 2665–2684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colagrossi, A.; Landrini, M. Numerical simulation of interfacial flows by smoothed particle hydrodynamics. J. Comput. Phys. 2003, 191, 448–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Yu, P. A technique to remove the tensile instability in weakly compressible SPH. Comput. Mech. 2018, 62, 963–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, J.P.; Fox, P.J.; Zhu, Y. Modeling Low Reynolds Number Incompressible Flows Using SPH. J. Comput. Phys. 1997, 136, 214–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brackbill, J.U.; Kothe, D.B.; Zemach, C. A continuum method for modeling surface tension. J. Comput. Phys. 1992, 100, 335–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adami, S.; Hu, X.Y.; Adams, N.A. A new surface-tension formulation for multi-phase SPH using a reproducing divergence approximation. J. Comput. Phys. 2010, 229, 5011–5021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, T.; Wu, J.; Zhang, T.; Dong, X. A weakly compressible smoothed particle hydrodynamics framework for melting multiphase flow. AIP Adv. 2022, 12, 025329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Liu, J.; Liu, S.; Li, Z. Quasi-static simulation of droplet morphologies using a smoothed particle hydrodynamics multiphase model. Acta Mech. Sin. 2019, 35, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zhuang, T.; Gao, C.; Dong, X. Numerical modeling and simulation of underwater explosions interacting with discrete rigid bodies. AIP Adv. 2023, 13, 105003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).