Abstract

This study emphasizes the role of magnetic separation as a novel pretreatment strategy for the recovery of indium from ITO coatings in LCD screen glass. Previous studies have primarily focused on the magnetic separation of leaching residues. In this work, a reverse approach is proposed, and for the first time, magnetic separation was systematically applied prior to leaching. Our results demonstrate that indium accumulates in the ferromagnetic fraction, indicating its association with Fe-rich phases. In addition to Fe, the behavior of Sr and Si was also evaluated, providing a broader understanding of elemental distribution within LCD glass. This finding offers new insights into the distribution and mobility of indium during hydrometallurgical processing and highlights magnetic separation as a valuable step for improving recovery efficiency. To establish optimal leaching conditions, preliminary experiments were performed on ground LCD glass using sulfuric acid at three concentrations (0.1, 1, and 5 M) and two temperatures (21 °C and 65 °C) for both coarse (>1 mm) and fine (<1 mm) particle fractions. All residues and solid-state analyses were performed using the XRF method. Acid molarity was found to be the dominant factor controlling indium dissolution, with 5 M H2SO4 selected as the most effective leaching medium. Statistical evaluation further clarified the dissolution trends of these elements and confirmed the significance of magnetic separation in enhancing the efficiency of indium recovery.

Keywords:

indium; ferromagnetic fraction; LCD; leaching; magnetic separation; recycling; sulfuric acid 1. Introduction

Indium is a strategically important metal, primarily utilized in the form of indium tin oxide (ITO) in liquid crystal displays (LCDs), touchscreens, flat panel displays (FPDs), and photovoltaic (PV) panels [1,2,3]. FPD (including touchscreens, smart windows, laptop monitors, and television screens) represents the largest application segment, accounting for approximately 60% of global indium consumption, predominantly in the form of ITO [4]. ITO, typically composed of 90:10 or 95:5 weight ratios of indium oxide to tin oxide, combines high electrical conductivity with excellent optical transparency [5,6], making it the material of choice for transparent electrodes in LCDs and smart window technologies. Industrially, ITO is most commonly produced by sputtering or electron-beam evaporation, yielding the material in powder form [7]. Despite its critical role in modern electronic and energy technologies, indium is a finite and unevenly distributed resource [8,9]. Its primary production as a byproduct of zinc ore mining not only limits global supply but also imposes significant environmental and economic burdens. With global digitalization and renewable energy expansion intensifying demand for displays and PV modules, pressure on primary indium sources continues to mount. This growing demand underscores the importance of developing sustainable secondary supply chains based on e-waste recycling. The indium concentration in certain waste streams, such as end-of-life PV panels or discarded LCD screens, can exceed that in primary ores, positioning the urban mining of e-waste as a viable and sustainable alternative. For instance, the indium content in LCD screen glass is typically 100–300 mg In/kg [10,11], but values can reach up to 1400 mg In/kg when the polymer film attached to the screen is removed before processing [12]. In contrast, primary sources such as sphalerite or chalcopyrite ores typically contain only 10–20 mg In/kg [11,13]. Table 1 presents the average indium content in various electronic equipment and PV.

Table 1.

Content of indium in electronic devices and PV.

In 2024, the global annual production of refined indium was approximately 920 tons [20]. It is predicted that indium, along with gallium, selenium, and tellurium, is one of the elements whose demand will increase up to 40-fold [21] in long-term forecasts until 2050. The main application sector for indium includes panel displays and screen manufacturing (≈60%) [4], where indium is used as ITO. The rapid expansion of electronics production and consumption continues to drive a steady increase in the demand for indium contained in FPDs, highlighting the urgent need for efficient recycling strategies for this waste stream. Given the nano-layered ITO coatings present on glass substrates [22,23], acid leaching is the most widely applied approach for releasing In3+ ions. The leaching efficiency was tested against various acid media using HCl [24,25], aqua regia [26,27], H2SO4 [27,28,29,30], HNO3 [31], or their combinations. These media have been shown to achieve an efficient dissolution of indium from ITO layers. Among them, H2SO4 remains one of the most widely employed leaching agents due to its unique combination of competitive advantages, i.e., high dissolution efficiency of the In2O3 phase, relatively low cost, moderate corrosivity, and compatibility with downstream indium separation and recovery processes [14,15,32]. These attributes make sulfuric acid particularly suitable for integration into closed-loop recycling schemes for ITO-bearing waste, where leaching is followed by selective indium recovery steps. The results obtained using sulfuric acid are promising—the recovery efficiency reaches 95–100% under appropriately optimized conditions of temperature, acid concentration, and reaction time. For example, Pu et al. [30] achieved 96.5% indium recovery using a pressure leaching technique with 2 M H2SO4 for 2 h at 135 °C. Similarly, studies on the optimization of leaching conditions showed 99.5% efficiency of indium solubilization under optimal operating parameters, including a leaching step of 30 min at 70 °C in the presence of 0.4 N H2SO4 and a pulp density of 50% (w/v) [28]. Even a 100% indium recovery in a one-step leaching process with 2 M H2SO4 at 80 °C in just 10 min has been reported [12]. Qin et al. [33] also confirmed the effectiveness of sulfuric acid in indium leaching from spent ITO targets, achieving a 99% leaching rate with a concentration of 5.3 mol/L and a temperature of 87 °C. H2SO4 remains a key leaching medium, providing compatibility with subsequent downstream separation, purification, and recovery steps. Processes such as solvent extraction [34], precipitation [35], cementation [25], and membrane separation processes (e.g., nanofiltration, reverse osmosis, membrane distillation, forward osmosis) [36] are employed, enabling efficient indium recovery rates of 95–99%. For example, H2SO4 proved to be an effective medium for leaching indium from TFT–LCD panels when combined with solvent extraction. Using H2SO4 at a 1:1 (v/v) concentration, an optimal liquid-to-solid ratio of 1:1, and solvent extraction with D2EHPA in 4 M HCl, a final indium extraction efficiency exceeding 97% was achieved [34]. Also, Lahti et al. [37] applied 1 M H2SO4 for leaching crushed LCD panels, obtaining an average yield of 97.4%. The downstream process included ultrafiltration to remove organic material, nanofiltration as a concentration step, liquid–liquid extraction for indium purification, and cementation, resulting in a 95.5% pure indium product with a 69.3% overall yield. These high efficiencies highlight the technical feasibility of transforming e-waste into a sustainable secondary indium resource. Table 2 presents an overview of the reagents used, recovery efficiencies, and supporting techniques applied for indium recovery.

Table 2.

Examples of reagents, recovery efficiencies, and supporting techniques applied for indium recovery.

Pre-treatment is a key step in the process of indium recovery from waste materials, as it directly affects the efficiency of subsequent leaching. Dismantling and separating glass layers from polymers (e.g., polarizers), followed by cutting and comminution, are the basic steps to obtain fractions with the desired particle size. Fine particles greatly increase the availability of the reaction surface and indium concentration [18,24]. However, alternative non-crushing approaches—such as ultrasonic treatment, pyrolysis, or thermal shock—can also achieve high performance while reducing energy consumption [24,38]. In parallel with these pre-treatment strategies, magnetic separation has become a well-established and increasingly applied technique in WEEE recycling [39,40,41,42]. Its main advantage lies in the ability to efficiently remove ferromagnetic components, thereby simplifying downstream processing and improving the quality of recovered fractions. Moreover, in studies on LCD waste streams, residual solids after acid leaching, when treated by magnetic separation, allow the isolation of ferromagnetic fractions while concentrating the remaining elements (In, Sn, Gd) in a magnetic solid [43,44].

However, previous studies have consistently treated magnetic separation as a final stage conducted after leaching. In this configuration, magnetic separation functions merely as an operation for removing dissolution residues rather than as a process step capable of influencing the leaching behavior itself. To date, no studies have systematically examined whether the preliminary removal of ferromagnetic phases—potentially associated with Fe oxides—could affect the subsequent selectivity of indium leaching. Moreover, it has remained unclear whether indium coexists with the magnetic fraction to an extent that would justify implementing magnetic separation prior to leaching. To the best of our knowledge, the present work directly addresses this knowledge gap by providing a systematic analysis of the direct application of magnetic separation prior to leaching, the behavior of indium during this step, and its potential distribution between magnetic and non-magnetic fractions and its association with ferromagnetic fractions. Addressing this unexplored aspect has therefore become a central objective of the present study.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the efficiency of chemical leaching of indium from LCD glass layers using sulfuric acid under various process conditions, with particular emphasis on magnetic separation as a novel pretreatment. Magnetic separation enabled the differentiation of ferromagnetic and non-magnetic fractions, clarifying the behavior of In, Fe, Sr, and Si. The influence of acid concentration, temperature, and particle size on In leaching efficiency was also evaluated. Statistical analyses were employed to elucidate dissolution trends and to confirm the significance of magnetic separation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Preparation

Mobile phones equipped with LCDs were manually disassembled, and the individual screen components—specifically the glass layers—were carefully separated for further processing. Manual disassembly was performed following standard practices reported in the LCD recycling literature [45,46]. While no specific cleaning step was applied, the subsequent grinding process ensured material homogenization, and potential organic residues do not interfere with sulfuric acid leaching or XRF analysis. The ITO-coated glass layers were then subjected to a two-stage mechanical comminution process. In the first stage, the material was coarse-crushed using a hammer crusher; in the second stage, it was finely ground in a ball mill. The ground material was subsequently dry-sieved into the following three particle size fractions (AS 200, Retsch GmbH, Haan, Germany): <1 mm, 1–1.5 mm, and >1.5 mm. Due to the minimal mass of the 1–1.5 mm fraction, it was combined with the >1.5 mm fraction. For the leaching experiments, the following two size classes were selected: (i) undersize fraction—particles smaller than 1 mm (<1 mm), (ii) oversize fraction—particles larger than 1 mm (>1 mm). It should be noted that the >1 mm fraction originated from coarse crushing in the hammer mill and consisted predominantly of large fragments (approximately 3 × 1 cm). Three representative samples from each fraction were analyzed before and after leaching using a handheld X-ray fluorescence spectrometer (Delta Professional, Evident, Atlanta, GA, USA) equipped with a Rh X-ray tube (up to 40 kV, 4 W) and a Silicon Drift Detector (SDD). The average compositions of the major components of the selected two fractions of LCD glass samples are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Percentage composition of the main elements in LCDs’ glass by XRF.

2.2. Leaching Experiments

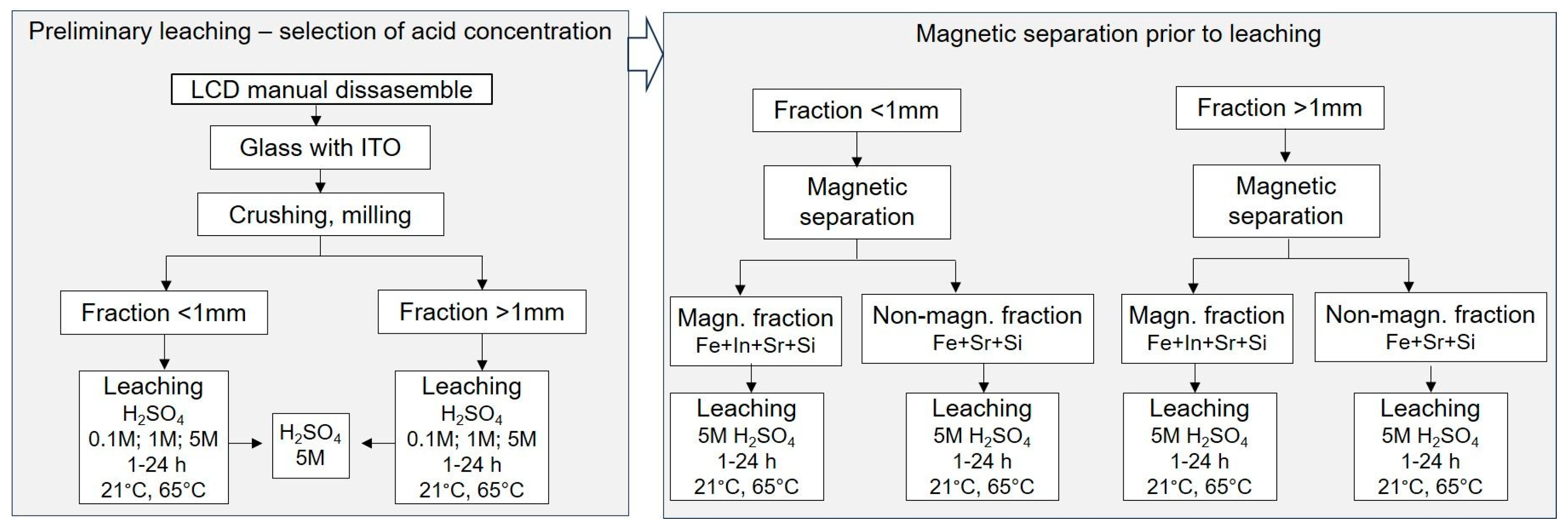

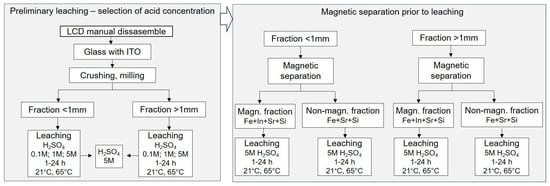

Preliminary leaching of ITO layers from ground LCD materials was carried out using sulfuric acid (Penta, Czech Republic; purity 96%) as the leaching agent. Experiments were performed under the following process conditions: temperatures of 21 °C (ambient) and 65 °C; acid concentrations of 0.1 M, 1 M, and 5 M; and a solid-to-liquid ratio of 1:5 (w/v), based on literature precedents [12,31,34,46]. Two particle size fractions of glass samples (<1 mm and >1 mm) were tested. For each run, 20 g of material was placed in a 300 mL glass beaker, and 100 mL of H2SO4 at the designated concentration was added. For the >1 mm fraction, 30 g of material and 150 mL of acid solution were used to compensate for the larger bulk volume. All beakers were placed in a Multitron Standard orbital shaker (Infors HT, Bottmingen, Switzerland) and agitated at 80 rpm under the specified temperature conditions. Leaching was conducted in independent single-cycle experiments with durations of 1 h, 2 h, 4 h, and 24 h. After leaching, the solid residues were separated from the solution, dried, and analyzed by XRF to assess changes in indium content. For each experiment, the final indium concentration in the solid samples was calculated as the average value of three randomly collected residues from each particle size fraction (<1 mm and >1 mm). These initial tests were designed to identify the most favorable and efficient leaching conditions in terms of acid concentration, temperature, and reaction time. These parameters provided a basis for subsequent experiments performed on fractions obtained after magnetic separation, ensuring that the influence of magnetic pre-treatment on indium recovery in leaching could be reliably assessed. The following steps of the experiment are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of sequential stages of the experimental procedure, leaching and magnetic separation.

2.3. Magnetic Separation Analysis

Before performing the final leaching experiments, magnetic separation was introduced as an additional step to assess the influence of removing ferromagnetic and paramagnetic components on subsequent chemical leaching (Figure 1). The crushed LCD samples were divided into two size fractions. The >1 mm fraction was processed using the laboratory magnetic separator LSV (Sollau, Velky Orechov, Czech Republic), a compact version of the multi-stage drum VMSV. The magnetic drum operates with a surface induction of up to 1.2 T, which enables an efficient retention of ferromagnetic and weakly paramagnetic particles. The separator was operated with a feed rate of 50 g per pass, and a total of approximately 200 g of material was processed per experiment through multiple passes to ensure complete separation into ferromagnetic and non-magnetic fractions. The <1 mm fraction was processed using the laboratory matrix magnetic separator MX-L (Sollau, Czech Republic). This separator employs a stainless-steel wool matrix magnetized by permanent neodymium magnets with a field intensity of up to 0.8 T. The fine fraction was dispersed in water at a solid concentration of 10% (w/v) and passed through the matrix by gravity. A total of approximately 100 g of material was processed through multiple cycles to achieve complete separation. Magnetic and paramagnetic particles were retained in the matrix, while diamagnetic material was discharged. The matrix was manually cleaned after each separation cycle. Following magnetic separation, all fractions were subjected to chemical leaching under identical conditions (5 M H2SO4 at 21 °C and 65 °C) as described in Section 2.2 to allow direct comparison with the results obtained prior to magnetic separation.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical evaluation was applied to clarify the dissolution patterns of In and its accompanying elements (Fe and Sr) and to determine the significance of magnetic separation as a preparatory step. Also, to verify the effects of acid concentration, temperature, and particle size on In leaching. R software version 4.4.1 [47] was used for plotting, correlation, and statistical analyses. Exploratory factor analyses were conducted using PCA for extraction, followed by Oblimin rotation, to identify the dominant variables influencing indium recovery using the psych package [48].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Effect of H2SO4 Concentration and Temperature

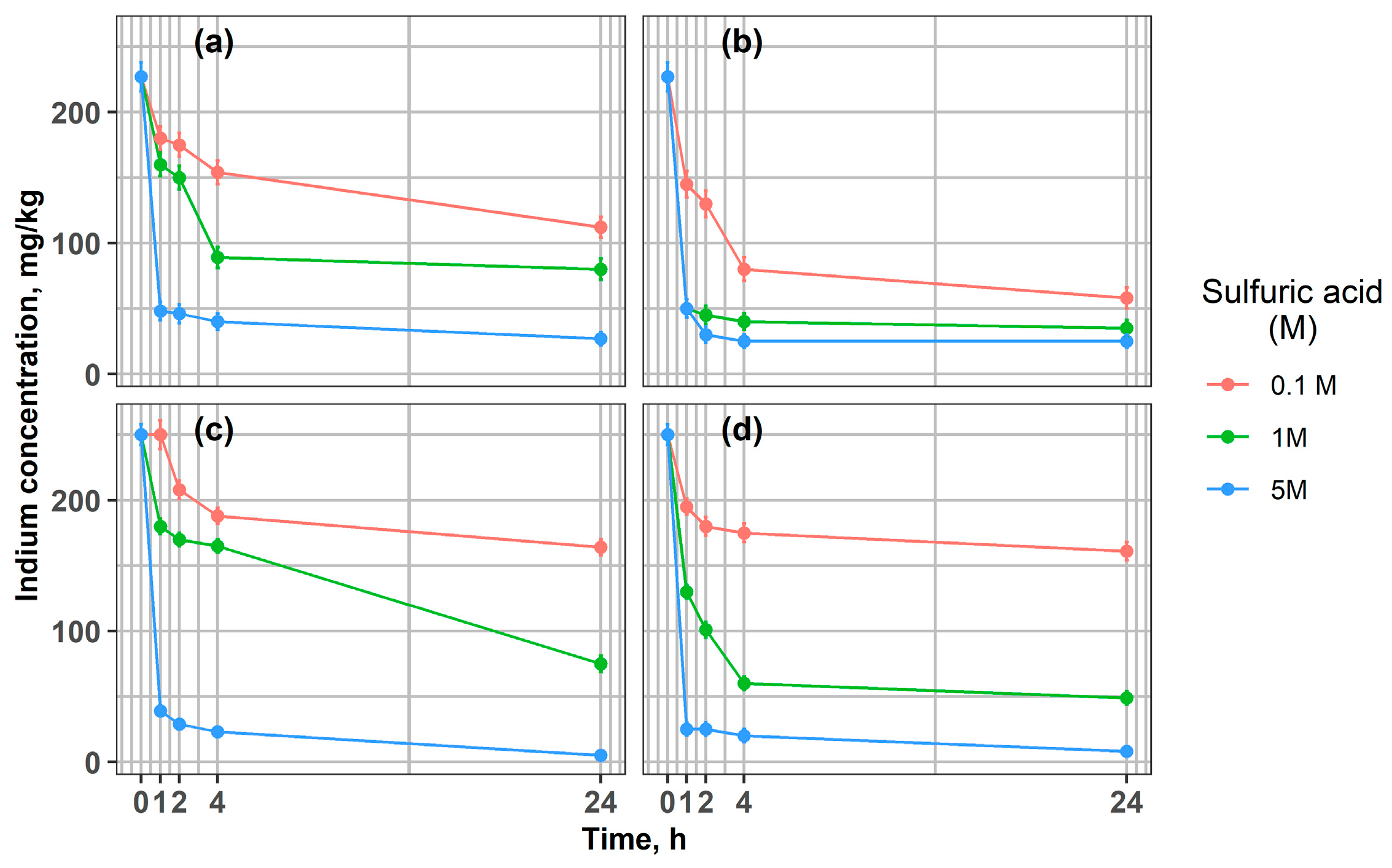

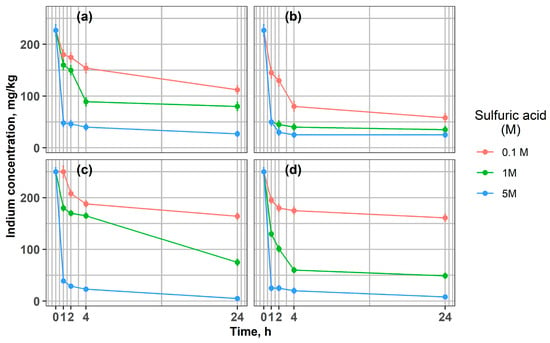

Figure 2 presents the indium concentration in the solid phase during the leaching of ground glass particles (<1 mm and >1 mm) at 21 °C and 65 °C. In all experimental conditions, indium concentrations decreased with increasing leaching time. This trend confirms that sulfuric acid efficiently dissolves indium from the ITO layers after more than one hour of leaching, with the effect being particularly pronounced at higher acid concentrations and elevated temperatures.

Figure 2.

Changes in indium concentration during leaching of LCD glass at different acid concentrations, 0.1 M, 1 M, and 5 M: (a) 21 °C, fraction > 1 mm; (b) 65 °C, fraction > 1 mm; (c) 21 °C, fraction < 1 mm; (d) 65 °C, fraction < 1 mm.

Coarser fractions (>1 mm) were leached to evaluate the potential to minimize energy-intensive grinding processes. Since mechanical pre-treatment on an industrial scale involves substantial operational and maintenance costs, this study examined whether effective indium extraction could be achieved without fine grinding. The efficiency of indium leaching from ITO layers exhibited a strong dependence on the concentration of sulfuric acid used (Figure 2). Higher H2SO4 concentrations (1 M and 5 M) markedly increased the amount of dissolved indium compared with the low-acid condition (0.1 M) for both <1 mm and >1 mm fractions. These results confirm that acid concentration is a key factor influencing extraction efficiency, consistent with previous literature. Our results indicate that it is possible to reduce In’s concentration in fraction < 1 mm from 250 mg/kg to 25 mg/kg after 1 h using 5 M H2SO4 and to 8 mg/kg after 24 h at 65 °C (Figure 2c,d). Similar results were reported by Shuster and Ebin [14]. Also, Silveira et al. [12] showed the influence of sulfuric acid concentration (0.1 M, 0.5 M, 1 M) on the efficiency of indium dissolution from LCD screens, achieving the best results using H2SO4 1 M and obtaining an average indium concentration of 554 mg/kg, significantly higher than in the case of 0.1 M (250 mg/kg). It was confirmed [28] that acid concentration and temperature are the most important parameters of the indium leaching process. Higher temperatures favored the extraction of indium from the LCD material, as reported in many studies [12,28,49,50]. The effect of higher temperature (65 °C) was evident for both <1 mm and >1 mm fractions. Notably, for the coarser fraction (>1 mm) leached with 1 M H2SO4, the highest extraction efficiency was achieved (Figure 2b). Indium concentration in the solid fraction was comparable with the results for 5 M acid, which resulted in an In concentration of 50 mg/kg after 1 h in the solid material. Even at ambient temperature (21 °C), fine grinding (<1 mm) enabled nearly complete indium removal, leaving only 3 mg/kg in the residue with 5 M sulfuric acid, compared with 27 mg/kg for the >1 mm fraction.

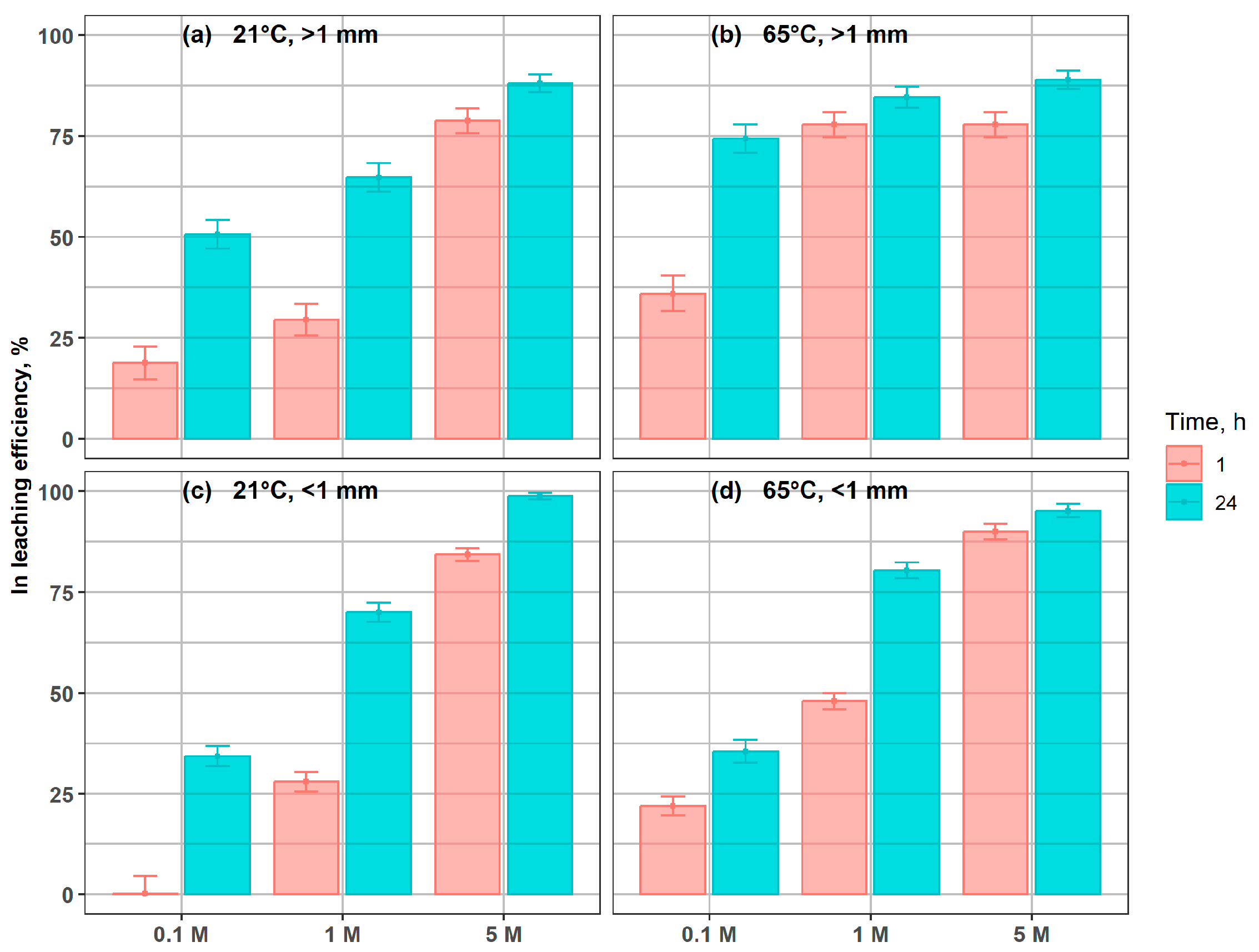

3.2. Indium Leaching Efficiency

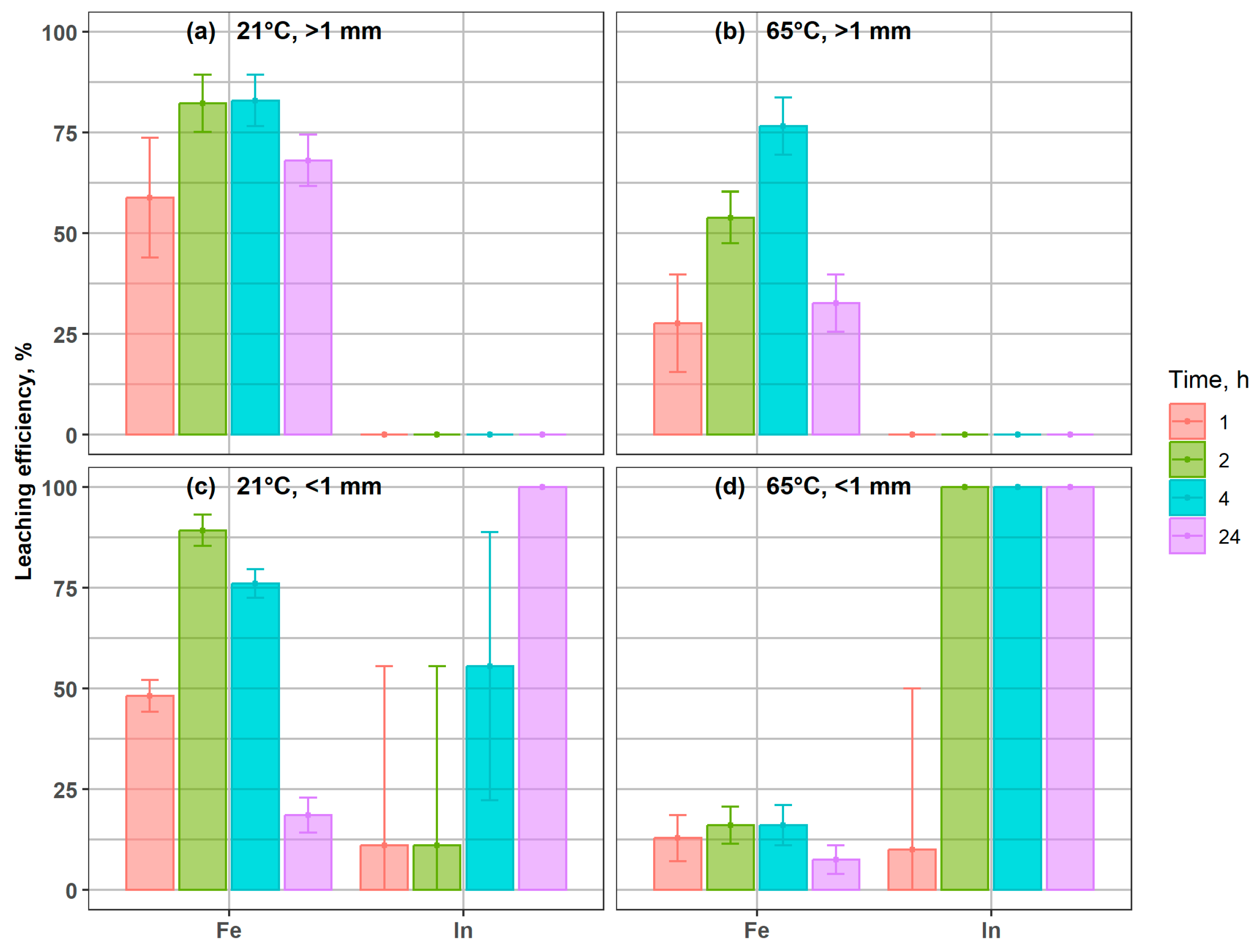

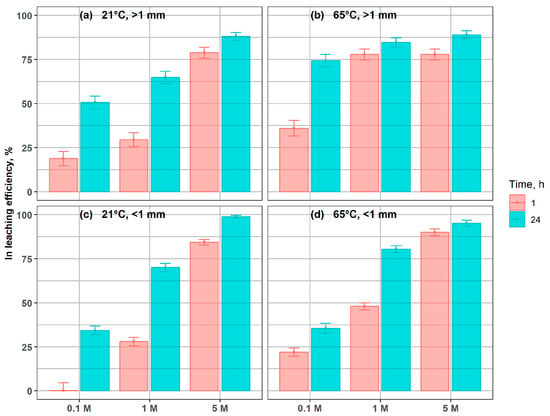

Indium leaching efficiencies are presented in Figure 3. Increasing grinding intensity did not substantially improve indium dissolution from the glass material. After 24 h of leaching with 5 M H2SO4, the differences in residual indium content between the particle-size fractions did not exceed 10%. For the fine fraction (<1 mm), leaching efficiencies of 98% and 95% were obtained at 21 °C and 65 °C, respectively, after 24 h in 5 M acid (Figure 3c,d). Under the same conditions, the coarser fraction (>1 mm) reached efficiencies of 88% and 89%, respectively. Notably, high leaching efficiencies (77–90%) were already achieved after just 1 h of treatment with 5 M H2SO4, depending on particle size and temperature.

Figure 3.

Indium leaching efficiency in coarse and fine fractions, under different conditions, after 1 h and 24 h, at: (a) 21 °C, >1 mm; (b) 65 °C, >1 mm; (c) 21 °C, < 1 mm; (d) 65 °C, <1 mm.

From an industrial perspective, these findings suggest that extensive comminution may not be strictly necessary, provided that leaching parameters—such as acid concentration, temperature, and contact time—are carefully optimized. This aligns with the observations of Silveira et al. [12] and Houssaine Moutiy et al. [28], who demonstrated that indium leaching efficiency depends more strongly on acid concentration and temperature than on particle size alone. Similarly, Yang et al. [31] reported that high surface exposure achieved through basic mechanical shredding—without removing polarizing films from the glass prior to shredding—was sufficient to obtain nearly complete indium dissolution in 1 M H2SO4 within less than 8 h at room temperature. Moreover, the use of higher acid concentrations consistently enhanced indium recovery, confirming that acid concentration is a more critical factor than particle size for rapid and effective leaching. Even for the coarse fraction, indium recovery at 5 M H2SO4 reached >88%, indicating that surface area limitations are likely mitigated by high proton availability and reaction kinetics at elevated molarity. Vučinić et al. [50] demonstrated that during indium recovery from LCD glass with a particle size of 10 × 10 mm, temperature was a critical factor; higher temperatures, combined with shorter leaching times, markedly improved indium extraction efficiency. It should be noted, however, that their leaching process was assisted by ultrasound, which substantially modifies mass transfer dynamics and accelerates leaching kinetics. Under these conditions, they achieved an indium leaching efficiency of up to 98% using an H2O:HCl:HNO3 mixture (6:2:1, v/v/v) at 40 °C for 40 min. The observed increase in leaching efficiency with temperature and acid concentration may be attributed to the intensification of surface reactions between H+ ions and the LCD matrix, leading to a loosening of the silica network and facilitated metal release. Under milder conditions, the process could be partially limited by reagent diffusion through the reaction product layer or the remaining glass phase, which may indicate a shift from chemical to diffusion control. Similar effects were reported by Cao et al. [51] and Swain et al. [52], emphasizing the importance of glass surface reactivity and diffusion barriers in the leaching kinetics of LCD materials. Selection of an appropriate processing strategy for indium recovery should begin at the comminution stage, where a balance must be struck between energy-intensive grinding and chemical process optimization. Grinding to fine particle sizes increases energy costs and dust generation, while moderate fragmentation combined with optimized leaching conditions (e.g., ≥1 M H2SO4, T ≥ 60 °C, t ≥ 1 h) may provide a more sustainable compromise, both economically and environmentally. Furthermore, the relatively high leaching efficiency observed for fractions > 1 mm (compared to fractions < 1 mm) may be due to differences in the morphology and degree of release of the metalliferous phase, where larger particles may contain more exposed or fractured reactive phases and exhibit better leaching efficiency. According to the observations of Crundwell [53] and Winardhi et al. [54], mineral phase morphology and release can significantly determine leaching kinetics, sometimes to a greater extent than particle size alone, suggesting the need for more detailed consideration of this phenomenon in future analyses and interpretations of the processes. Therefore, it should be noted that the presented study presents certain limitations that should be carefully addressed in further work, including modeling of long-term leaching kinetics, characterization of particle surface and morphology, and variations in glass composition. These factors can significantly influence mass transport mechanisms, surface reactions, and ultimately the efficiency of the indium leaching process.

Further research is needed to assess the threshold particle size below which no significant increase in leaching efficiency is observed, particularly for mixed or layered FPD. The choice of downstream separation and purification methods is equally critical to achieving high product purity and enabling the recirculation of process solutions, thereby further reducing operating costs and minimizing environmental impact. In this context, in addition to conventional solvent extraction and ion exchange, membrane separation processes appear particularly promising within the indium recycling chain. These technologies offer high retention rates for indium (>98%) and other metals (e.g., Ga, Ge, Mo, Sn, Sr), while enabling the recovery of up to 80% of water and more than 95% of purified acid for reuse [36]. It should be emphasized that the use of high-concentration acids (e.g., 5 M H2SO4) is associated with the risk of acidic wastewater generation, environmental chemical pollution, and infrastructure corrosion. Therefore, the recovery of acids is a significant factor in the recycling chain, and reusing the acidic solution in subsequent leaching cycles reduces reagent consumption and associated emissions [55]. Furthermore, it is possible to use membrane or ion-exchange techniques that can significantly reduce the environmental impact of acids [56]. Preliminary leaching experiments determined that the most effective indium recovery was achieved using 5 M H2SO4. Therefore, in further studies, preceded by magnetic separation, sulfuric acid at this concentration was used.

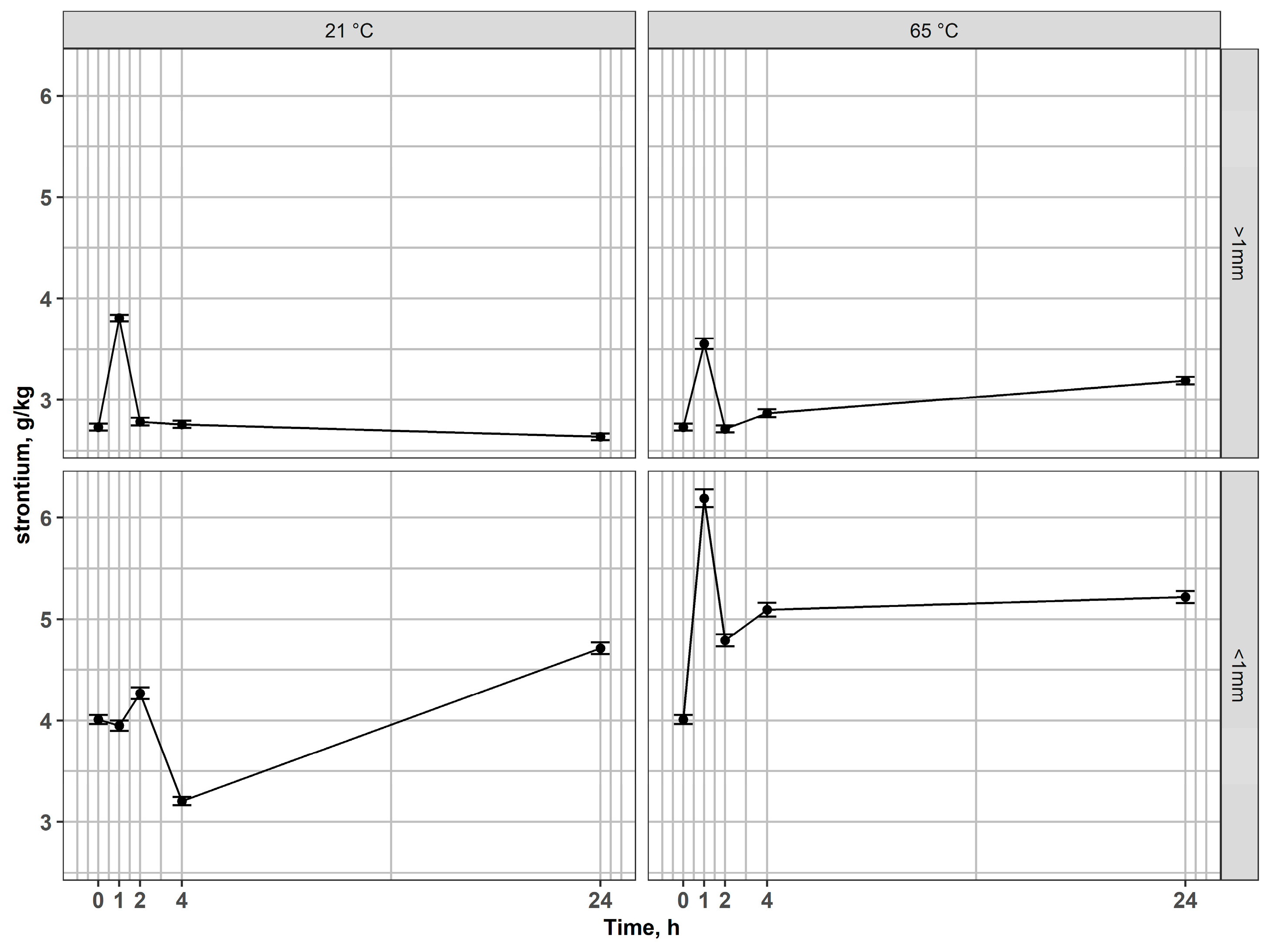

3.3. Magnetic Separation—Analysis of Input Material

The wet magnetic separation proved effective in concentrating elements into the studied fractions. The magnetic fraction > 1 mm demonstrated significantly higher concentrations of Fe, In, and Sr compared to the non-magnetic fraction (Table 4). This substantial enrichment, particularly the 3190-fold increase in iron content, confirms the successful separation of ferromagnetic components. The indium distribution is particularly noteworthy, as this critical element was exclusively detected in the magnetic fraction, suggesting its association with iron-bearing compounds in the LCD matrix. This finding has significant implications for indium recovery strategies from electronic waste, as magnetic separation can effectively pre-concentrate this valuable element prior to chemical processing.

Table 4.

Concentration of metals in different fractions of LCD materials after magnetic separation.

The magnetic separation of the fine fraction (<1 mm) showed different characteristics compared to coarser materials. The magnetic fraction contained enriched concentrations of Fe, In, and Sr, while the non-magnetic fraction exhibited substantially lower values (Table 4). The enrichment factors were considerably lower than observed for coarser fractions (>1 mm), with iron showing only a 113-fold concentration difference compared to the non-magnetic fraction. The indium distribution exhibited different behavior in the fine fraction (<1 mm). Indium was present in the magnetic fraction; however, its concentration was significantly lower overall, at 71 mg/kg, compared to the fraction > 1 mm, and was at undetectable levels in the non-magnetic fraction. This enrichment suggests that fine grinding may have liberated indium-bearing phases, making them less exclusively associated with magnetic components.

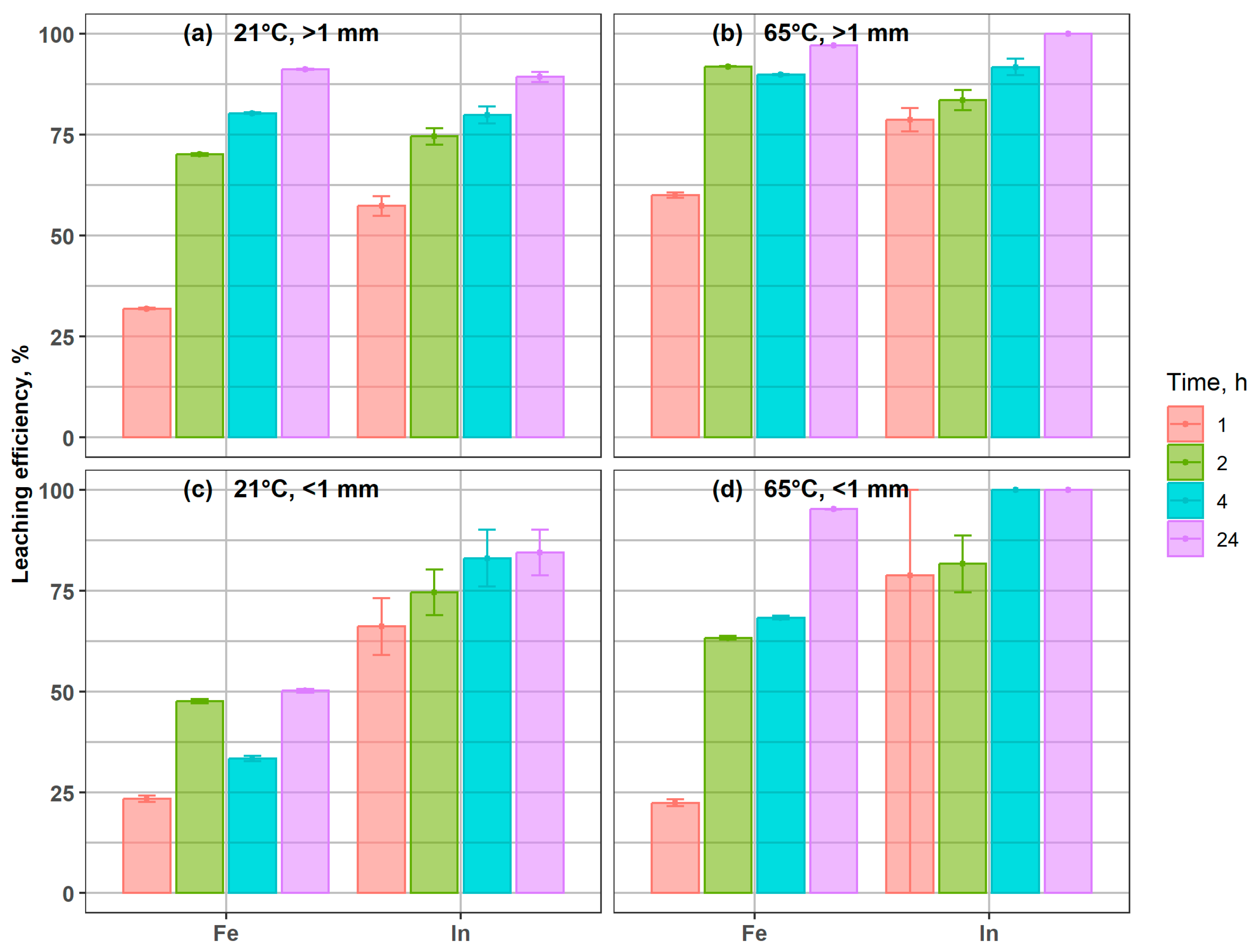

3.4. Magnetic Separation—Analysis of Magnetic Fractions

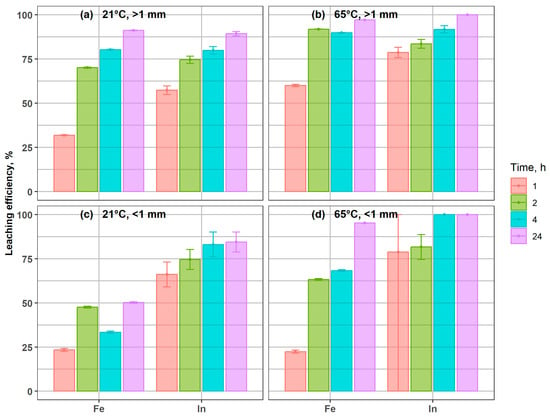

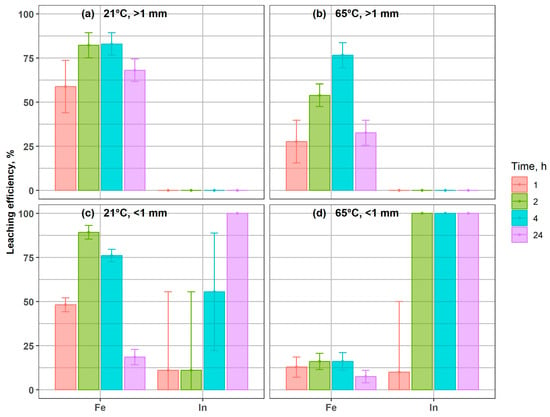

Figure 4 presents the extraction efficiency of Fe and In from magnetic coarse and fine fractions (>1 mm and <1 mm). In both cases, indium and iron exhibited a clear trend of progressive dissolution, and the temperature markedly influenced both leaching kinetics and yields. At 65 °C, the > 1 mm fraction reached nearly complete Fe extraction (97%) and full In recovery within 24 h (Figure 4b), compared to 91% and 89%, respectively, at 21 °C (Figure 3a), confirming the high leachability of In bound to magnetic carriers. In the fine magnetic fraction < 1 mm, Fe recovery increased from 50% at 21 °C to 95% at 65 °C after 24 h. Indium leaching was particularly accelerated at elevated temperature, with almost complete dissolution within 4 h at 65 °C, while residual In (11–24 mg/kg) remained in solids even after 24 h at 21 °C.

Figure 4.

Indium and iron leaching efficiency from coarse and fine magnetic fractions under different conditions: (a) 21 °C, >1 mm; (b) 65 °C, >1 mm; (c) 21 °C, <1 mm; (d) 65 °C, <1 mm.

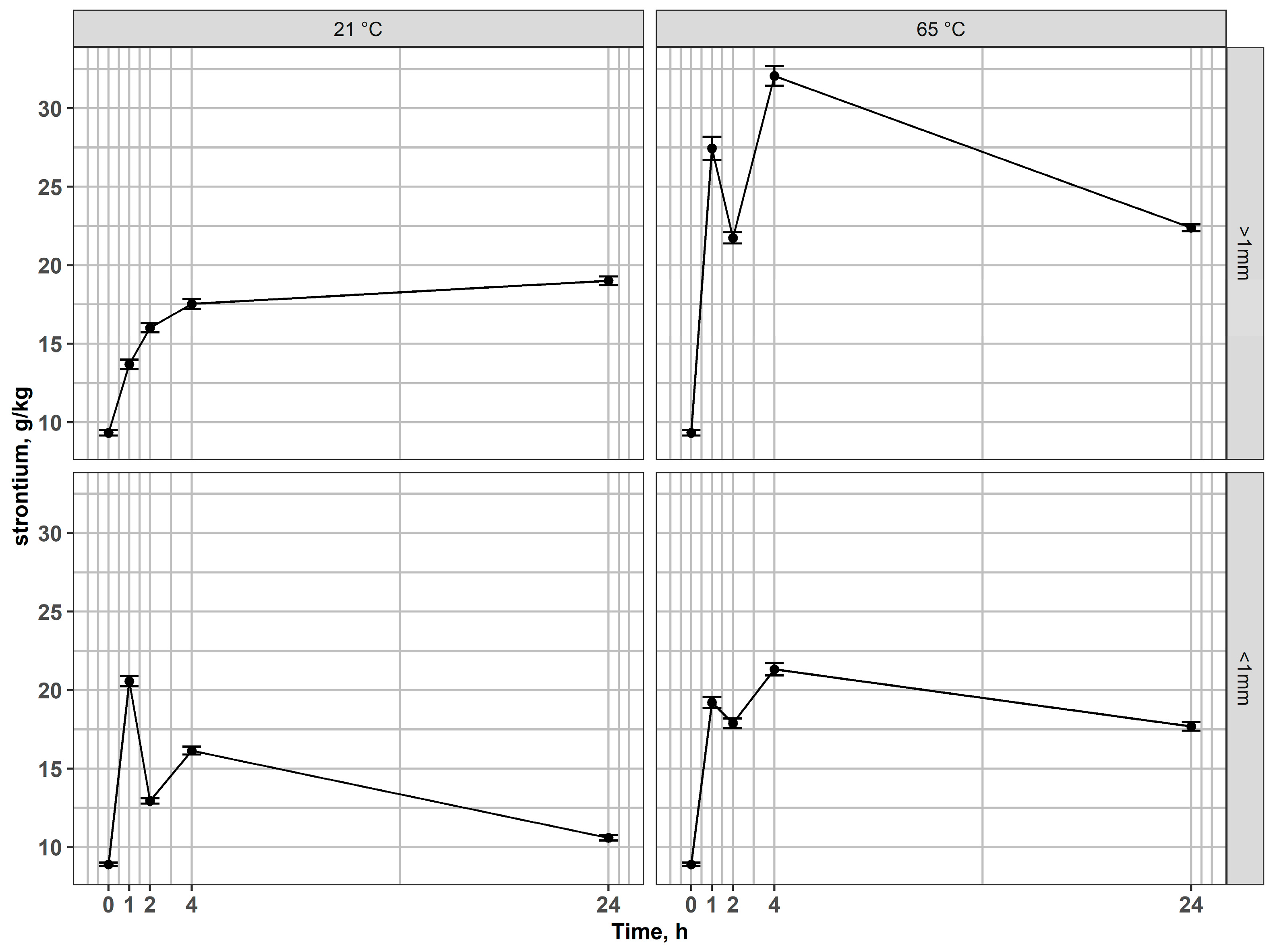

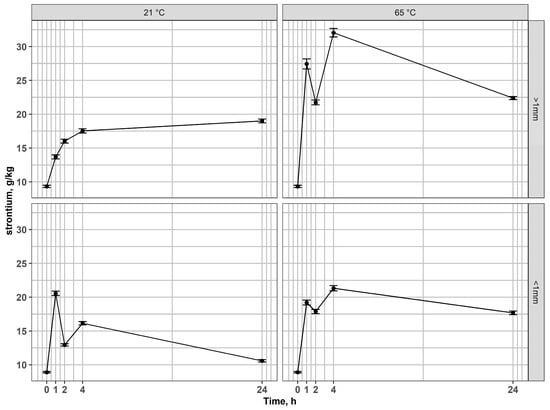

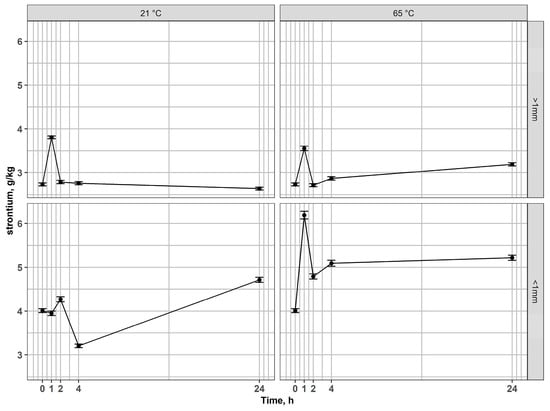

Studies by Toache-Pérez et al. [43,44] demonstrated that, following acid leaching of LCD waste, subsequent magnetic separation of the solid residues could lead to partial association of indium with ferromagnetic phases. Although indium is not inherently ferromagnetic, its presence in the magnetic fraction was attributed to the co-precipitation or co-sorption onto Fe-bearing phases (such as iron oxides or hydroxides) formed during leaching. This indicated that Fe could act as a carrier for In, explaining its measurable levels in the magnetic fraction. However, our study shows that In is probably entrapped within ferromagnetic phases in the original material, and co-precipitation or co-sorption during leaching is not necessarily the reason why it can be found in magnetic fractions. This finding emphasizes the importance of considering magnetic pre-treatment in designing efficient indium recovery strategies. In the coarse magnetic fraction (>1 mm), Sr concentrations increased relative to the input during leaching, reaching the highest values after 4 h at 65 °C (Figure 5). This indicates that Sr was not effectively leached, but rather became enriched in the solid residue, most likely due to the preferential dissolution of Fe- and In-bearing phases, which reduced the overall mass and led to a relative concentration effect. In the fine magnetic fraction (<1 mm), Sr showed a similar tendency toward enrichment, confirming its low solubility and persistence in the solid phase.

Figure 5.

Changes of strontium content in residues after leaching of magnetic fractions at 21 °C and 65 °C for coarse and fine fractions.

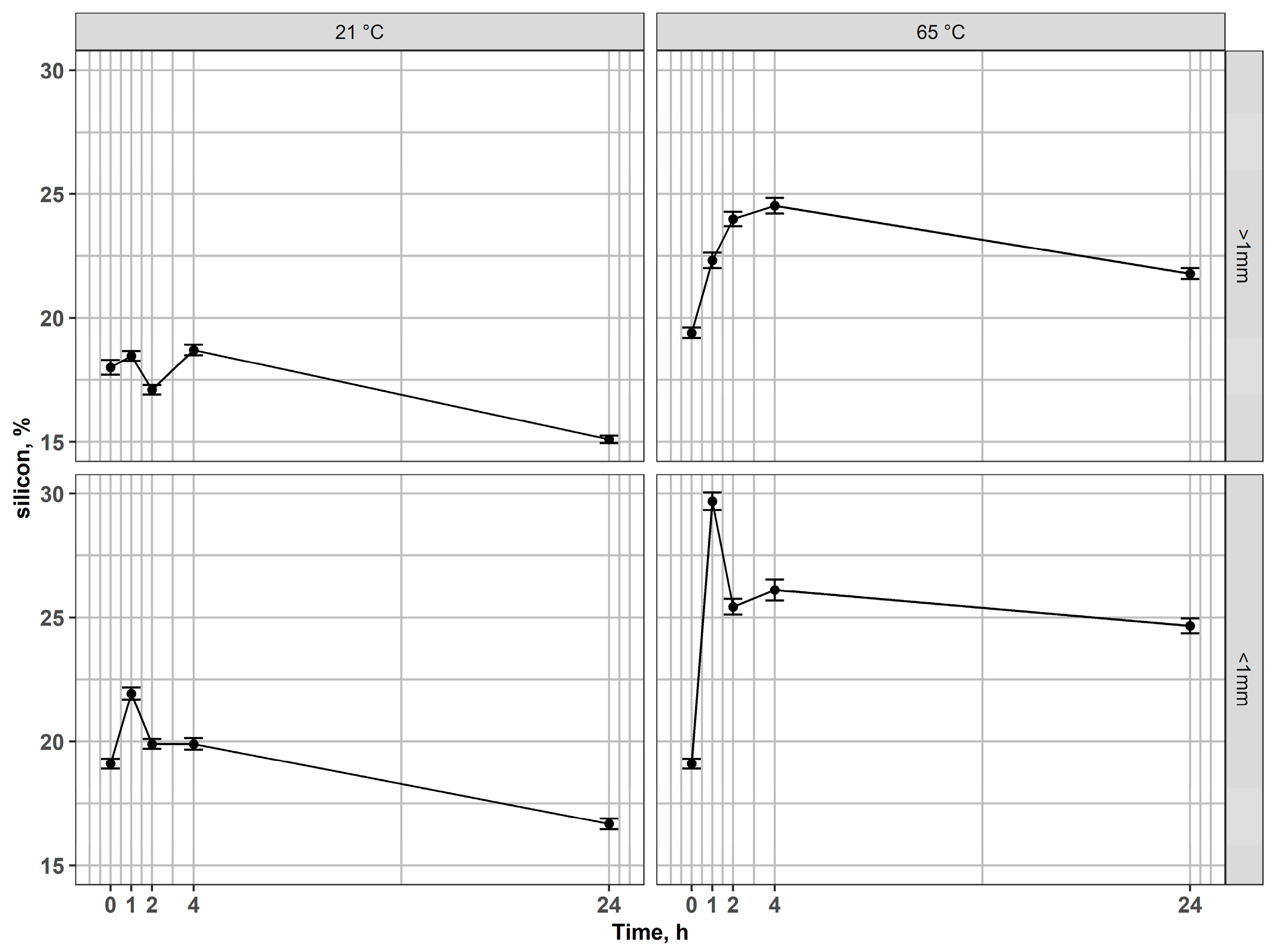

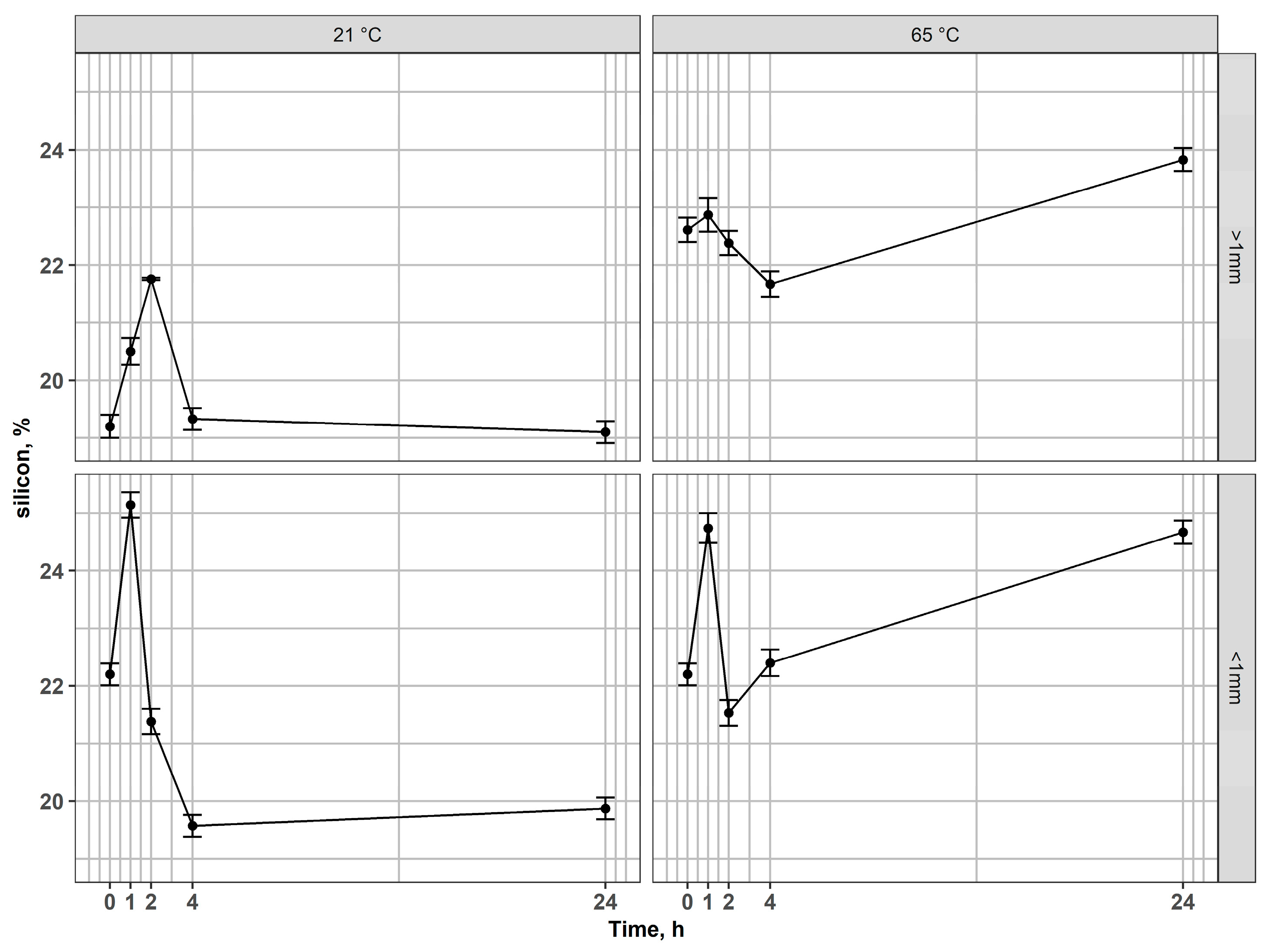

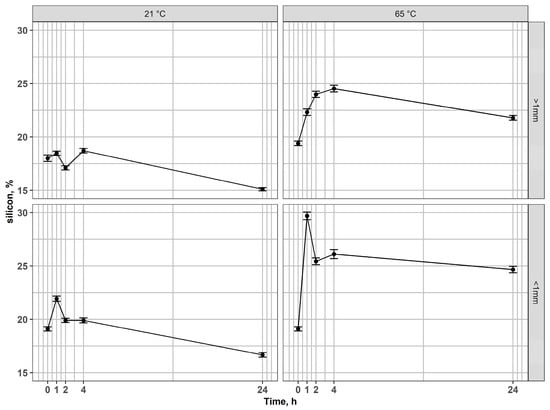

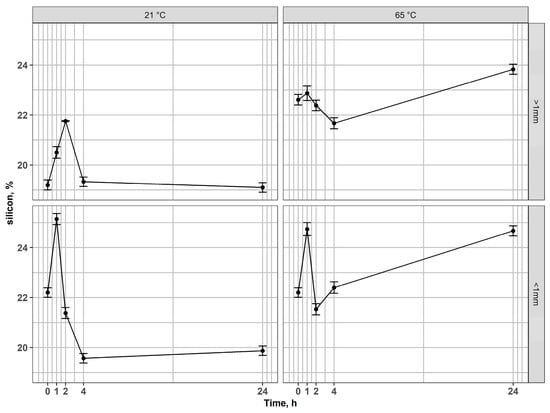

In the case of silicon, an interesting behavior of this element has been observed (Figure 6). In both fractions, Si percentages in the solid phase increased during the early leaching stages, reflecting preferential dissolution of other phases (Fe and In). Next, after long-term leaching (24 h), the percentage of Si in the residues decreased, compared to the values achieved in the earlier stages of leaching or compared to the input value. This behavior reflects a two-step mechanism. At early leaching stages, the removal of mobile modifiers (alkali/alkaline earth cations like Na, Ca, B, or Fe, In) from the glassy network reduces the overall mass of the residue, resulting in an apparent enrichment of Si expressed. At prolonged contact times in acid, however, the silicate network itself undergoes hydrolysis and bond cleavage (Si–O–Si), leading to the dissolution of silica into the leachate in the form of monomeric silicic acid (H4SiO4) [57,58,59,60], which explains the final decrease in Si concentration in residues after 24 h. Additionally, difficulties with the filtration of post-leaching solutions indicate the presence of dissolved silica. However, for a full understanding of the underlying mechanisms and the behavior of Si during leaching, further experimental investigations are required.

Figure 6.

Changes of silicon content in residues after leaching of magnetic fractions at 21 °C and 65 °C for coarse and fine fractions.

3.5. Magnetic Separation—Analysis of Non-Magnetic Fractions

Figure 7 shows the leaching efficiency of Fe and In from the non-magnetic fractions (>1 mm and <1 mm). Indium was undetected in the input of the coarse non-magnetic fraction > 1 mm (Table 4) and remained unreleased across all leaching experiments, confirming its association with the magnetic fraction. Measurable indium (9 mg/kg) was present initially in the fine fraction and fully dissolved within 2 h at 65 °C (Figure 7d) and within 24 h at 21 °C (Figure 7c), indicating a higher leachability of indium due to the increased surface area and finer particle size. Iron showed strong variability in both fractions, with a decrease at early stages and partial recovery at longer times, suggesting reprecipitation or matrix redistribution.

Figure 7.

Indium and iron leaching efficiency from coarse and fine non-magnetic fractions under different conditions: (a) 21 °C, >1 mm; (b) 65 °C, >1 mm; (c) 21 °C, <1 mm; (d) 65 °C, <1 mm.

In the non-magnetic fraction > 1 mm, strontium remained essentially stable across all conditions (Figure 8), while Si content exhibited only minor fluctuations (Figure 9), reflecting the inert nature of the silicate matrix and its acid-resistance. However, in fractions < 1 mm, Sr concentrations increased markedly at elevated temperatures, pointing to an enhanced release of elements from associated phases. Si content varied moderately, reflecting partial structural destabilization of the glass matrix during prolonged leaching.

Figure 8.

Changes of strontium content in residues after leaching of non-magnetic fractions at 21 °C and 65 °C for coarse and fine fractions.

Figure 9.

Changes of silicon content in residues after leaching of non-magnetic fractions at 21 °C and 65 °C for coarse and fine fractions.

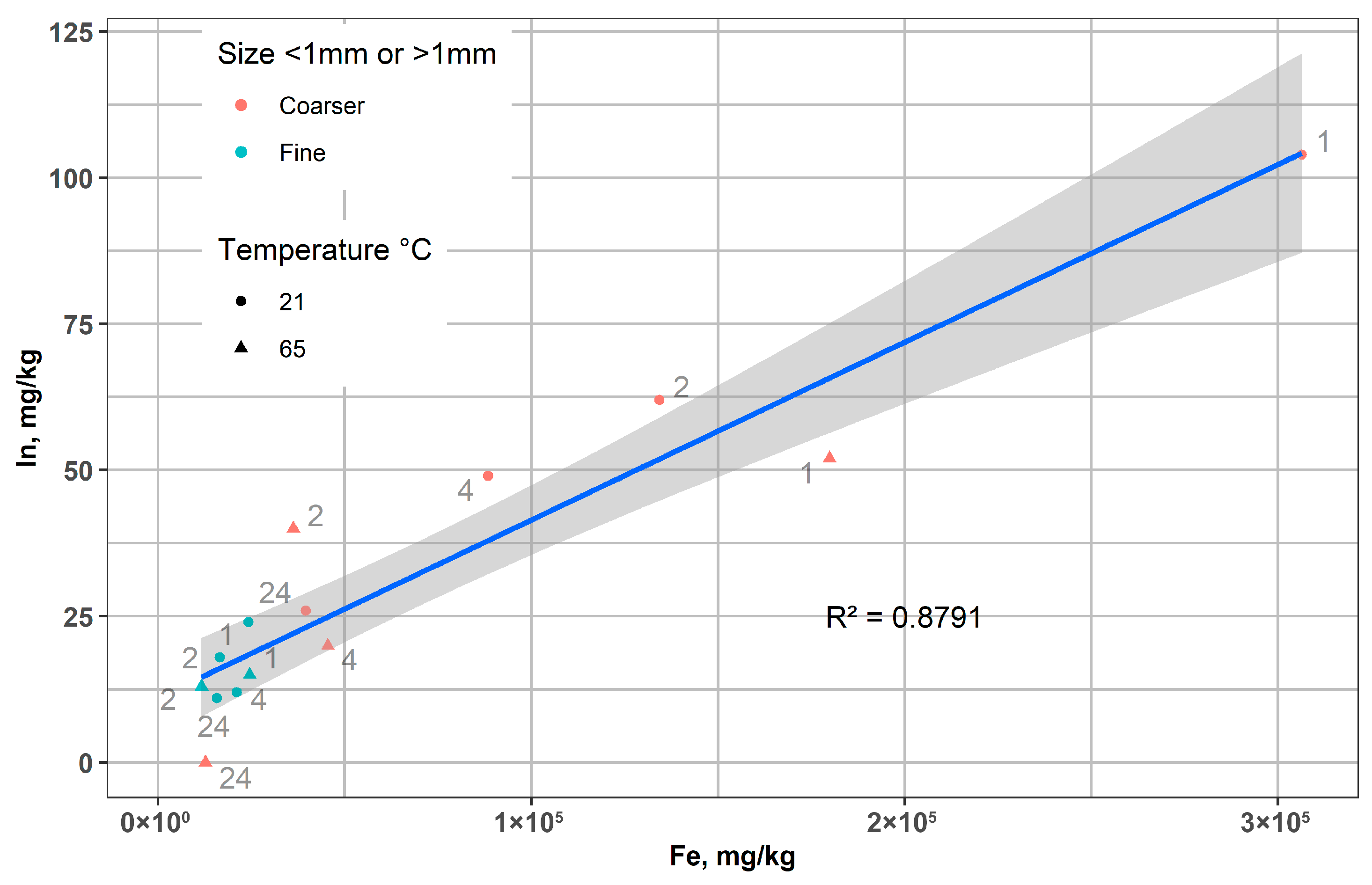

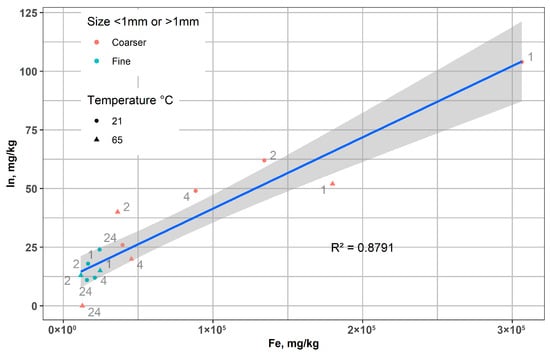

3.6. Relationship Between in and Fe in LCD Glass Residue

Figure 10 shows a significant positive correlation between the concentrations of In and Fe in the leached LCD glass residues after magnetic separation, which varied under different conditions (time, fraction size, and temperature). The linear trend indicates that indium is closely associated with Fe-rich phases, irrespective of particle size, leaching temperature, or time. Variability between coarse and fine fractions, as well as between experimental conditions, reflects differences in leaching progress, but the overall proportionality confirms the coupled behavior of In and Fe during the process.

Figure 10.

The relationship between the concentrations of In and Fe in the leached LCD glass after magnetic separation.

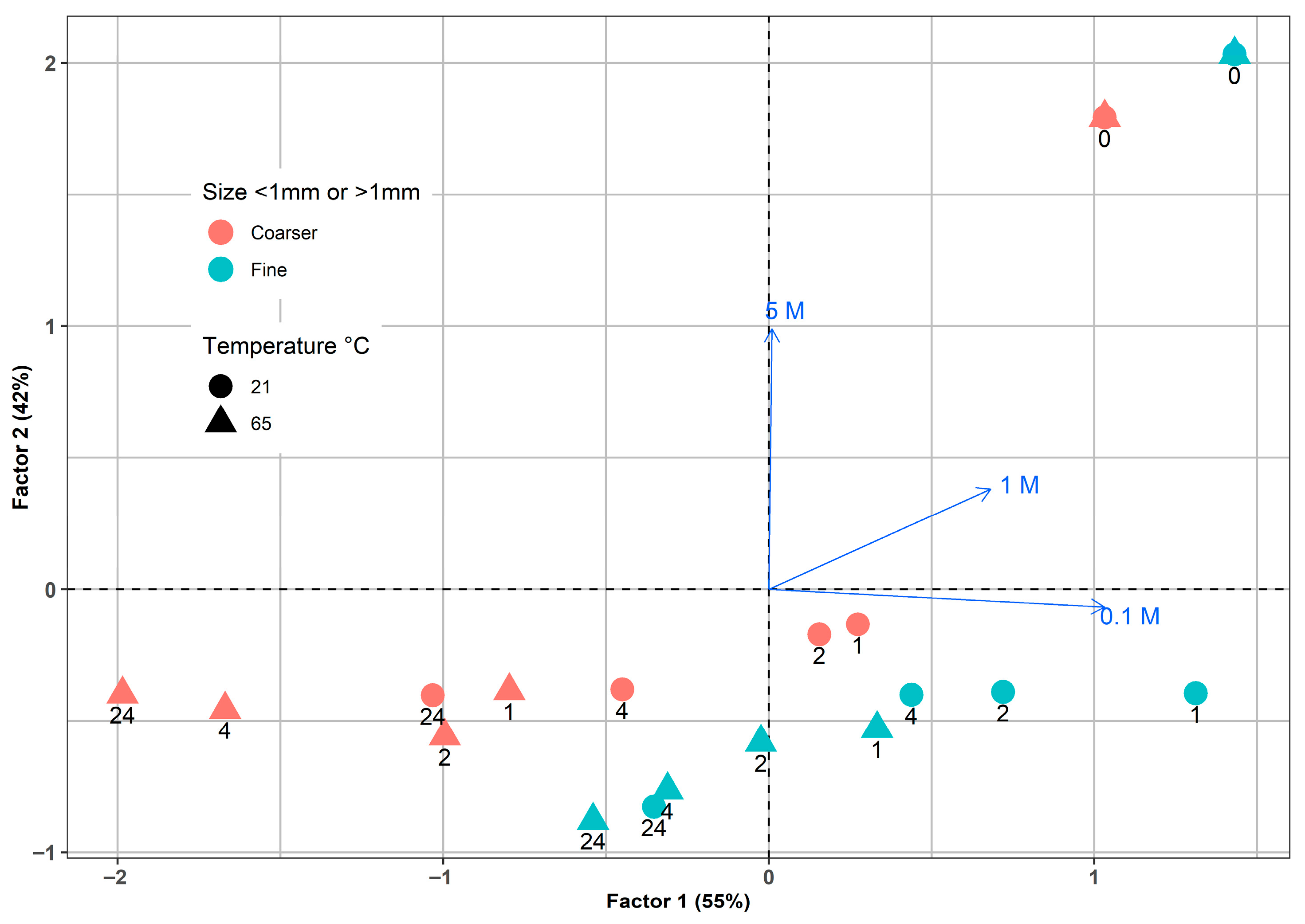

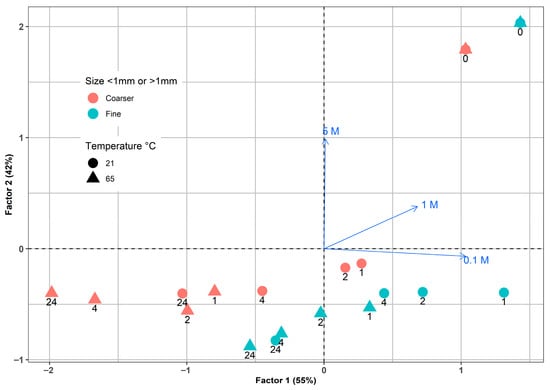

Factorial analysis was conducted on the In concentrations found in LCD glass residues, which were subjected to various leaching conditions. These conditions included temperature, particle size, leaching time, and sulfuric acid concentrations. The analysis captured a total variance of 97%, which is almost evenly distributed between the first and second factors, as illustrated in Figure 11. Notably, a strong correlation was observed between the 0.1 M H2SO4 and Factor 1, while Factor 2 was closely associated with 5 M H2SO4. The strongest separation effect was obtained for 5 M H2SO4, which confirms the dominant role of acid concentration in controlling the extraction process.

Figure 11.

Factorial analysis for In leaching by different sulfuric acid concentrations from LCD glass.

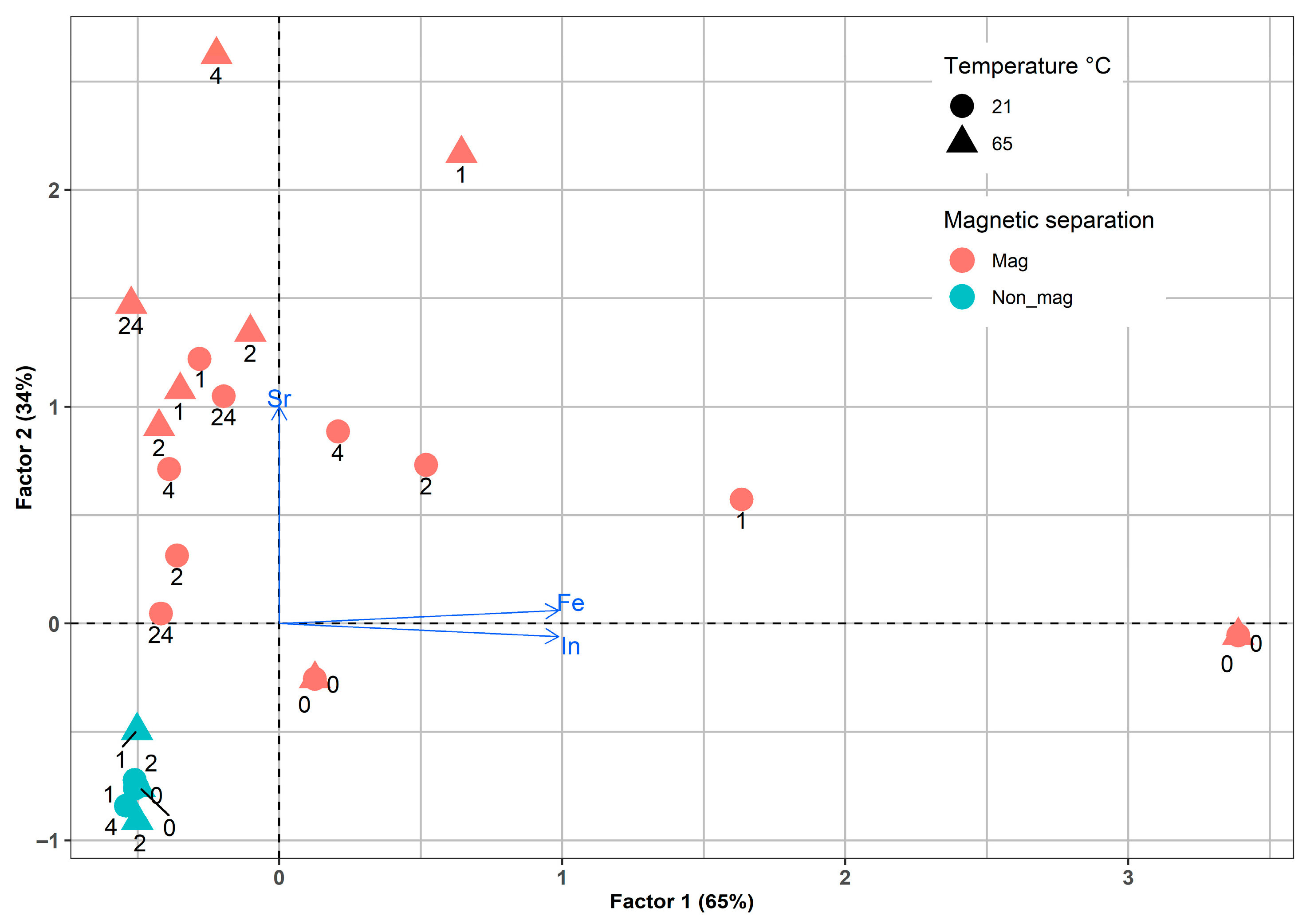

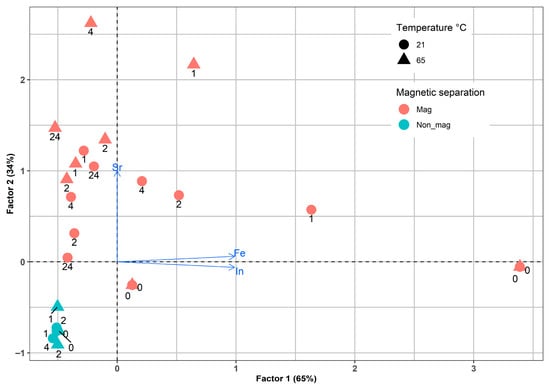

A second factorial analysis was conducted on the concentrations of In, Fe, and Sr obtained from LCD residues after leaching with 5 M H2SO4 under various conditions, including temperature, particle size, leaching time, and magnetic separation. This analysis accounted for a significant portion of the total variance, specifically 99% and the PCA plot (Figure 12) shows a clear separation of the fraction samples after magnetic separation. Factor 1 explained 65% of the variance and was primarily associated with changes in the concentrations of two metals, In and Fe, throughout the leaching experiment, which are strongly correlated and indicate their relationship with the magnetic fraction. Additionally, a distinct scatter pattern was observed in the variance space for samples subjected to magnetic separation, which supports the magnetic treatment’s effectiveness. Factor 2 is related exclusively to changes in Sr concentrations, which has almost half the influence of Factor 1. Finally, the point pattern confirms the key role of magnetic separation in controlling the distribution of elements in LCD glass.

Figure 12.

Factorial analysis of the In, Fe, and Sr leaching by sulfuric acid.

4. Conclusions

This study investigated the distribution and leaching behavior of In, Fe, Sr, and Si in LCD glass waste using a combined magnetic separation–sulfuric acid leaching approach. Our results provide direct experimental evidence that ferromagnetic carriers represent the primary In reservoir in LCD glass waste. The key findings were the following:

- magnetic separation prior to leaching clearly demonstrated that indium accumulates in ferromagnetic fractions, confirming its association with Fe-bearing phases.

- the coarse magnetic fraction (>1 mm) showed the highest In concentration (244 mg/kg) together with extremely elevated Fe content (450,000 mg/kg), whereas In was undetected in the non-magnetic counterpart.

- In the fine fraction, In was present in the magnetic part (71 mg/kg) but absent in the non-magnetic residue, further supporting an Fe-controlled distribution.

- Sr remained largely immobile and accumulated in solid residues during leaching, indicating low solubility and minor interaction with Fe- and In-bearing phases.

- Si exhibited partial mobility, showing initial enrichment followed by depletion during extended leaching, suggesting glass matrix restructuring and possible secondary reactions.

- Leaching tests confirmed that 5 M H2SO4 at 65 °C yields the highest In dissolution efficiency.

- Particle size showed limited influence, implying potential for reduced energy use in mechanical pretreatment.

Overall, these findings highlight the importance of coupling magnetic separation with optimized leaching conditions to support sustainable indium recycling from electronic waste streams. Future research is necessary to optimize magnetic separation for fine particle fractions and implement acid recycling strategies, together with scale-up considerations, to facilitate industrial application potential.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.J.; methodology, I.J. and D.H.; software, J.W. and G.Y.; validation, J.W., I.J. and J.S.-K.; formal analysis, M.J.-C.; investigation, I.J. and D.H.; resources, J.W.; data curation, I.J. and J.W.; writing—original draft preparation, J.W. and I.J.; writing—reviewing and editing, M.J.-C. and J.S.-K.; visualization, J.W. and G.Y.; supervision, M.J.-C.; project administration, M.J.-C. and J.S.-K.; funding acquisition, I.J., J.S.-K., J.W. and M.J.-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Interreg Danube Region, co-funded by the European Union, within the project DRP0401069—BioPrep, Biotechnological Innovations for Sustainable Flat Panel Display Recycling.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Jana Sedlakova-Kadukova was employed by the company ALGAJAS s.r.o. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The company had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, or interpretation of data; in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Ueberschaar, M.; Schlummer, M.; Jalalpoor, D.; Kaup, N.; Rotter, V.S. Potential and Recycling Strategies for LCD Panels from WEEE. Recycling 2017, 2, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becci, A.; Amato, A.; Merli, G.; Beolchini, F. The Green Indium Patented Technology SCRIPT, for Indium Recovery from Liquid Crystal Displays: Bench Scale Validation Driven by Sustainability Assessment. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souada, M.; Louage, C.; Doisy, J.-Y.; Meunier, L.; Benderrag, A.; Ouddane, B.; Bellayer, S.; Nuns, N.; Traisnel, M.; Maschke, U. Extraction of Indium-Tin Oxide from End-of-Life LCD Panels Using Ultrasound Assisted Acid Leaching. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2018, 40, 929–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Study on the EU’s List of Critical Raw Materials—Final Report; European Commission: Luxembourg, 2020. Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2873/24089 (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Toikka, A.; Ilin, M.; Kamanina, N. Perspective Coatings Based on Structured Conducting ITO Thin Films for General Optoelectronic Applications. Coatings 2024, 14, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.; Guo, L.J. Nanoimprinted semitransparent metal electrodes and their application in organic light-emitting diodes. Adv. Mater. 2007, 19, 1391–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, J.; Sharme, R.K.; Quijada, M.A.; Rana, M.M. A Review of Transparent Conducting Films (TCFs): Prospective ITO and AZO Deposition Methods and Applications. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ylä-Mella, J.; Pongrácz, E. Drivers and Constraints of Critical Materials Recycling: The Case of Indium. Resources 2016, 5, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sverdrup, H.; Allen, O.; Haraldsson, H. Modeling Indium Extraction, Supply, Price, Use and Recycling 1930–2200 Using the WORLD7 Model: Implication for the Imaginaries of Sustainable Europe 2050. Nat. Resour. Res. 2024, 33, 539–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.Y. A Study of the Effects of LCD Glass Sand on the Properties of Concrete. Waste Manage. 2009, 29, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Wu, Y.; Wang, W.; Li, B.; Zhang, Y.; Zuo, T. Recycling Indium from Waste LCDs: A Review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2015, 104, 276–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, A.V.M.; Fuchs, M.S.; Pinheiro, D.K.; Tanabe, E.H.; Bertuol, D.A. Recovery of Indium from LCD Screens of Discarded Cell Phones. Waste Manage. 2015, 45, 334–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J. Recovery of Indium from End-of-Life Liquid Crystal Displays. Bachelor’s Thesis, Chalmers University of Technology, Gothenburg, Sweden, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Schuster, J.; Ebin, B. Investigation of Indium and Other Valuable Metals Leaching from Unground Waste LCD Screens by Organic and Inorganic Acid Leaching. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 279, 119659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocchetti, L.; Amato, A.; Fonti, V.; Ubaldini, S.; De Michelis, I.; Kopacek, B.; Veglio, F.; Beolchini, F. Cross-Current Leaching of Indium from End-of-Life LCD Panels. Waste Manag. 2015, 42, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jowkar, M.J.; Bahaloo-Horeh, N.; Mousavi, S.M.; Pourhossein, F. Bioleaching of Indium from Discarded Liquid Crystal Displays. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 180, 417–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willner, J.; Fornalczyk, A.; Saternus, M.; Sedlakova-Kadukova, J.; Gajda, B. LCD Panels Bioleaching with Pure and Mixed Culture of Acidithiobacillus. Physicochem. Probl. Miner. Process. 2022, 58, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Ning, S.; Fujita, T.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, S.; Lu, S. Leaching of Indium and Tin from Waste LCD by a Time-Efficient Method Assisted Planetary High Energy Ball Milling. Waste Manag. 2021, 120, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajec, M.; Król, A.; Holewa-Rataj, J.; Kukulska-Zając, E.; Kuchta, T. Electrolytic Recovery of Indium from Copper Indium Gallium Selenide Photovoltaic Panels: Preliminary Investigation of Process Parameters. Recycling 2025, 10, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Geological Survey. Mineral Commodity Summaries 2024; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Carrara, S.; Alves Dias, P.; Plazzotta, B.; Pavel, C. Raw Materials Demand for Wind and Solar PV Technologies in the Transition Towards a Decarbonised Energy System; European Commission: Luxembourg, 2020.

- Techinstro. ITO Coated Glass. Available online: https://www.techinstro.com/ito-coated-glass/ (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Park, G.; Kim, D.; Kim, G.; Jeong, U. High-Performance Indium–Tin Oxide (ITO) Electrode Enabled by a Counteranion-Free Metal–Polymer Complex. ACS Nanosci. Au 2022, 2, 527–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savvilotidou, V.; Hahladakis, J.N.; Gidarakos, E. Leaching Capacity of Metals-Metalloids and Recovery of Valuable Materials from Waste LCDs. Waste Manag. 2015, 45, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, Z.; Li, Q.; Liu, Z.; Zeng, L. Recovery of Indium from Used Indium-Tin Oxide (ITO) Targets. Hydrometallurgy 2011, 105, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinnam, R.K.; Ujaczki, É.; O’Donoghue, L. Leaching Indium from Discarded LCD Glass: A Rapid and Environmentally Friendly Process. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 277, 122868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, A.P.; Kasper, A.C.; Veit, H.M. Acid Leaching of Indium from the Screens of Obsolete LCD Monitors. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 103758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houssaine Moutiy, E.; Tran, L.H.; Mueller, K.K.; Coudert, L.; Blais, J.F. Optimized Indium Solubilization from LCD Panels Using H2SO4 Leaching. Waste Manag. 2020, 114, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willner, J.; Krzymińska, N. Possibilities for Recovering Indium from Electronic Devices. Proceedings 2024, 108, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, Q.; Zhang, B.; Zhou, S.; Wei, Y.; Li, B.; Wang, H. Efficient Recovery of Indium from Waste Indium Tin Oxide (ITO) Targets by Pressure Leaching with Sulfuric Acid. React. Chem. Eng. 2023, 8, 2332–2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Retegan, T.; Ekberg, C. Indium Recovery from Discarded LCD Panel Glass by Solvent Extraction. Hydrometallurgy 2013, 137, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferella, G.; Belardi, A.; Marsilii, I.; De Michelis, I.; Veglio, F. Separation and recovery of glass, plastic and indium from spent LCD panels. Waste Manag. 2017, 60, 569–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, K.; Mei, F.; Yuan, T.; Li, R.; Jiang, J.; Niu, P.; Chen, H. Effects of Sintering Processes on the Element Chemical States of In, Sn and O in ITO Targets. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2018, 29, 7931–7940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, J.; Guo, Y.; Qiao, Q. Recovery of Indium from Scrap TFT-LCDs by Solvent Extraction. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2012, 16, 545–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Liang, D.; Zhong, Q. Precipitation of indium using sodium tripolyphosphate. Hydrometallurgy 2011, 106, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortot Coelho, F.E.; Moreira, V.R.; Majuste, D.; Ciminelli, V.S.T.; Amaral, M.C.S. Sustainable indium recovery from e-waste and industrial effluents: Innovations and opportunities integrating membrane separation processes. Desalination 2025, 612, 118900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahti, J.; Vazquez, S.; Virolainen, S.; Mänttäri, M.; Kallioinen, M. Membrane filtration enhanced hydrometallurgical recovery process of indium from waste LCD panels. J. Sustain. Metall. 2020, 6, 576–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Li, B.; Wu, Y.; Wang, W.; Li, R.; Zhang, Y.N.; Zuo, T. Recycling of Indium from Waste LCD: A Promising Non-Crushing Leaching with the Aid of Ultrasonic Wave. Waste Manag. 2017, 64, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, J.; Wang, K.; Wang, Q.; Lei, Z. Application of Magnetic Separation Technology in Resource Utilization and Environmental Treatment. Separations 2024, 11, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulliani, S.; Volpe, M.; Messineo, A.; Volpe, R. Recovery of Metals and Valuable Chemicals from Waste Electric and Electronic Materials: A Critical Review of Existing Technologies. RSC Sustain. 2023, 1, 1085–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Forssberg, E. Mechanical Recycling of Waste Electric and Electronic Equipment: A Review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2003, 99, 243–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veit, H.M.; Diehl, T.R.; Salami, A.P.; Rodrigues, J.S.; Bernardes, A.M.; Tenório, J.A.S. Utilization of Magnetic and Electrostatic Separation in the Recycling of Printed Circuit Boards Scrap. Waste Manag. 2005, 25, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toache-Pérez, A.D.; Bolarín-Miró, A.M.; Sánchez-De Jesús, F.; Lapidus, G.T. Facile Method for the Selective Recovery of Gd and Pr from LCD Screen Wastes Using Ultrasound-Assisted Leaching. Sustain. Environ. Res. 2020, 30, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toache-Pérez, A.D.; Lapidus, G.T.; Bolarín-Miró, A.M.; De Jesús, F.S. Selective Leaching and Recovery of Er, Gd, Sn, and In from Liquid Crystal Display Screen Waste by Sono-Leaching Assisted by Magnetic Separation. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 31897–31904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsa, A.; Bahaloo Horeh, N.; Mousavi, S.M. A Hybrid Thermal-Biological Recycling Route for Efficient Extrac-tion of Metals and Metalloids from End-of-Life Liquid Crystal Displays (LCDs). Chemosphere 2024, 352, 141408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, M.; Grimes, S.; Yang, L.; Pornsirianant, T.; Fowler, G. Novel Resource-Efficient Recovery of High Purity Indium Products: Unlocking Value from End-of-Life Mobile Phone Liquid Crystal Display Screens. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 111327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Software R Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Revelle, W. Procedures for Psychological, Psychometric, and Personality Research, R Package Version 1.9.12; Northwestern University: Evanston, IL, USA, 2019. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=psych (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Gu, S.; Fu, B.; Dodbiba, G.; Fujita, T.; Fang, B. A Sustainable Approach to Separate and Recover Indium and Tin from Spent Indium–Tin Oxide Targets. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 52017–52023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anić Vučinić, A.; Šimunić, S.; Radetić, L.; Presečki, I. Indium Recycling from Waste Liquid Crystal Displays: Is It Possible? Processes 2023, 11, 1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Li, F.; Li, G.; Huang, J.; Zhu, H.; He, W. Leaching and Purification of Indium from Waste Liquid Crystal Display Panel after Hydrothermal Pretreatment: Optimum Conditions Determination and Kinetic Analysis. Waste Manag. 2020, 102, 635–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swain, B.; Lee, C.G.; Hong, H.S. Value Recovery from Waste Liquid Crystal Display Glass Cullet through Leaching: Understanding the Correlation between Indium Leaching Behavior and Cullet Piece Size. Metals 2018, 8, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crundwell, F.K. The Dissolution and Leaching of Minerals: Mechanisms, Myths and Misunderstandings. Hydrometallurgy 2013, 139, 132–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winardhi, C.W.; Godinho, J.R.A.; Gutzmer, J. The Effect of Macroscopic Particle Features on Mineral Dissolution. Minerals 2023, 13, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toli, A.; Panias, D.; Tsakiridis, P.E. The Efficient Use of Sulfuric Acid in Bauxite Residue Leaching: Towards Sustainable Processing. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2023, 3, 53. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, C.; Sharma, N.; Singh, S.; Chandra, R. Remediation and Recycling of Inorganic Acids and Their Green Applications. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 24454–24475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gin, S.; Jollivet, P.; Fournier, M.; Angeli, F.; Frugier, P.; Charpentier, T. Origin and Consequences of Silicate Glass Passivation by Surface Layers. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gin, S.; Delaye, J.M.; Angeli, F.; Schuller, S. Aqueous Alteration of Silicate Glass: State of Knowledge and Perspectives. npj Mater. Degrad. 2021, 5, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auyeshov, A.; Arynov, K.; Yeskibayeva, C.; Dikanbayeva, A.; Auyeshov, D.; Raiymbekov, Y. Transformation of Silicate Ions into Silica under the Influence of Acid on the Structure of Serpentinite. Molecules 2024, 29, 2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazadi, D.M.; Groot, D.R.; Steenkamp, J.D.; Pöllmann, H. Control of Silica Polymerisation during Ferromanganese Slag Sulphuric Acid Digestion and Water Leaching. Hydrometallurgy 2016, 166, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).