Abstract

Personal protective equipment (PPE) like single-use face masks is discarded after a single use and poses a significant danger to the environment, resulting in plastic pollution. Most of the face masks are made from synthetic polymers and are non-biodegradable to the environment; hence, concerns are being raised about polymers’ environmental impact. Most of the previous studies so far focus on polypropylene (PP) disposable masks and limited data related to environmental abiotic degradation behavior. There is a lack of studies aiming to understand the degradation behavior of different masks and the influence of physical-chemical factors. In this paper, we report on the environmental abiotic degradation of cloth, surgical and respirator filter facepiece 1 (FFP1) masks by accelerated artificial weathering. Furthermore, physical-chemical properties of masks were characterized by Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR), Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) and Thermo Gravimetric Analysis (TGA). The cloth and FFP1 masks are made from polyethylene terephthalate (PET) and surgical masks were made from polypropylene (PP). Masks were exposed to an accelerated weathering test, which simulates the effects of natural sunlight and reproduces the damage caused by weathering elements such as sunlight, rain and dew. Masks were exposed to Ultraviolet radiation (UV) for 120, 240 and 360 h followed by condensation at 50 °C for 4 h. The FTIR results show that PET cloth and FFP1 PET masks are not degrading with the 360 h maximum exposure duration, which is equivalent to ±180 days. The FTIR scan of the PP surgical mask after 120 h of exposure time shows that it was degraded and broken down into fragments. For the PET cloth mask, a 58% reduction in crystallinity and heat of enthalpy was observed after 120 h of exposure. UV exposure causes a chain scission reaction, breaking down the ester bond in the case of the PET cloth mask. In the case of the PET FFP1 mask exposed to UV for 120, 240 and 360 h, a drastic reduction in crystallinity was observed as compared to the neat (original) PET FFP1 mask. Neat PET cloth and FFP1 masks have higher onset and maximum degradation temperatures as compared to the 120, 240 and 360 h UV exposed masks. Neat PET cloth and FFP1 masks have better resistance to thermal degradation.

1. Introduction

Personal protective equipment (PPE) in the form of face masks, gloves and face shields plays an important role in the fight against transmissible diseases by acting as barriers, as the main primary mode of transmission of the infectious virus, airborne particles, are transmitted through contaminated respiratory droplets from heavy breathing, coughing, sneezing and talking. PPE acts as a barrier by blocking particles from entering or leaving. The barrier reduces the chance of contracting or transmitting infectious particles. Wearing masks in public and practicing social distancing are important in preventing the transmission of infectious diseases. There was high consumption of these items, which resulted in increased waste disposal. PPE-like single-use face masks and gloves are disposed of after a single use and pose a significant danger to the environment, resulting in plastic pollution [1,2,3].

Synthetic polymers are widely used to make PPE, and commonly used fibers are polyester, polypropylene (PP), polyurethane and polystyrene. PP fibers are dominant textile fibers used in surgical, respirator filter facepiece 1 (FFP1) and N95 masks. In gloves, the dominant polymer is high-density polyethylene. Cloth masks are made of cotton, polyester or a blend of different fibers. Most face masks are made from different synthetic polymers, and these polymers take ages to degrade in the environment. Hence, there remains concern about polymers’ impact on the environment. During the COVID-19 pandemic, it was estimated that around 4.3 billion masks and 2.17 million gloves were used every day. The use of individual masks and gloves is continuing in many places [2,4,5]. PPEs have been found in forests, rivers, oceans and streets. Less expensive PPE is more likely to be discarded than expensive PPE. Compared to other types of PPE, single-use masks and gloves have been found littered in public areas, beaches, shopping malls, parking lots, etc. Spennemann [6] reported that surgical masks (93.5%) are discarded more than N95 (1.6%) and cloth (4.2%) masks. It is estimated that about 250,000 tons of plastic are disposed of every day and only about 10–20% is recycled, 50–60% is sent to landfills and 20–30% is incinerated [7,8].

In many countries, the legislation encourages or forces communities to wear masks to minimize viral transmission; similar efforts are not seen when it comes to the environmental impact of these PPE when they are disposed of after use. Another problem with this slow degradation process is the release of micro- and nano-plastics impacting the environment as well as humans, as traces of them are seen in human cells and drinking water, leading to serious health concerns [9,10,11,12].

Physical and chemical degradation of PPE (PP face mask and low-density polyethylene gloves—LDPE) obtained from seawater under simulated environmental conditions for 60 days was reported (De-la-Torre et al., 2022) [13]. All experiments were performed outside of the laboratory and in environmental conditions from August to September 2021, with temperatures in August and September ranging from 34 to 40 °C and 32 to 38 °C, respectively. There was no rain during these two months at the place of study. The chemical structure of the materials was evaluated by Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR), X-ray diffraction (XRD) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Signs of physical degradation in PPE, such as ruptures and rough surfaces, were observed and increased as time progressed, along with changes in the PPE backbone. There were changes in the intensity of diffraction peaks, indicating shifts in the crystallinity of PPE and changes in the thermal behavior. Furthermore, there were traces of heavy metals like Molybdenum and Copper after degradation. The authors did not study the role of humidity and there was no information about thermal degradation.

In a study, Chou et al., 2025 reported the photolysis of PP face masks in facilitating manganese oxide nanoparticle formation in water surfaces [14]. They simulated water contamination as the face mask was in contact with water surfaces. The authors used a light intensity of 1.75 ± 0.1 kW/m2 for two weeks to stimulate photo aging and study the release of micro/nano-particles. The manganese oxide formed can alter the fate and transport of pollutants like organic compounds and heavy metals and affect the quality of surface water. The authors reported changes in the FTIR spectra after photoaging, but there was no data about other physicochemical parameters, like thermal and chemical degradations.

In another study, Lyu et al., 2023 reported aging of disposable PP face masks in landfill leachates [15]. The masks consisted of three layers, spun-bonded inner and outer layers and a melt-blown middle layer. The UV weathering of the masks was performed in a UV chamber with a wavelength of 302 nm and a UV intensity of 20 mW/cm2 at a distance of 0.5 inches. The duration of UV exposure was 4, 24, 36 and 48 h. The authors used FTIR and SEM for surface characterization and there was data related to the release of heavy metals. The authors reported that UV radiation caused oxidation and degradation in masks after UV exposure.

Yu et al., 2023 reported the weathering and degradation of polylactic acid (PLA) masks in a simulated environment for four weeks [16]. The authors reported that the weathering degradation of PLA fibers in water mainly occurs through the hydrolysis of ester bonds, leading to fiber breaking down and the release of microplastics. The exposure to UV light intensity was at 45 W, 254 nm and it was turned on every 12 h to simulate the day and night effect. The authors used FTIR for surface characterization but did not mention the weathering temperature used for the experiment. Furthermore, there was no information about chemical and thermal degradation.

Spennemann [17] reported environmental degradation of single-use surgical face masks under natural sunlight for 10 weeks and photographic images were taken as evidence every week. These masks were made-up of PP. Visible degradations were observed for the spun-bonded mask as compared to the melt-blown mask, with accelerated degradation observed in the spun-bonded mask after three weeks of exposure time. Knicker and Velasco-Molina [18] studied the degradation behavior of surgical face masks in soil for six months. The center of the mask degraded in 7 years, whereas the remaining sections degraded in between 19 and 28 years based on mean residence time in a carbon pool.

In another study, the degradation behavior of various types of face masks in an aquatic environment was studied [19] by using artificial weathering conditions for two weeks in substituted ocean water [19]. The authors used a UV lamp (UVA-340 nm) with an irradiance of 0.76 W/m2. They used different characterization techniques to understand the impact of degradation. The chemical structures of the mask samples do not change drastically due to the shorter time used for artificial aging, which was only two weeks. Oliveira et al. [20] emphasizes the importance of understanding the degradation and toxicity of face masks and future studies are required to understand the degradation behavior of masks.

In a recent paper, De Bigault De Cazanove et al., 2025 studied the influence of artificial weathering on the abiotic degradation of LDPE films, of which many are used as plastic carry/shopping bags [21]. The main aim of this study was to show how different artificial weathering protocols affect degradation behavior. Authors used three different weathering protocols: continuous UV-A irradiation, cyclic UV-dark exposure and sequential UV-dark phase. The exposure to UV light was at 0.78 W/m2 and temperatures were in between 50 °C and 60 °C. Authors highlighted the role of light in the degradation process and oxidative reactions continued during the dark phases. The authors did not mention duration and humidity was also not considered, which stimulates actual weather conditions. Furthermore, the degradation of film masks is not similar to that of fabric and nonwoven face masks.

From the summary of the existing literature related to the abiotic degradation of PPE, there are three major research gaps (Table 1). The first gap is the changes in the physical-chemical parameters that describe changes in the material’s structure and surface properties during the degradation phases that played an important role in environmental analysis. How do physical-chemical parameters change after artificial weathering? The second gap is the types of PPE material used for degradation studies. The majority of the studies focus on PP and only a few studies focus on other fibers, as shown in Table 1. To address this, we have used cloth, surgical and respirator filter facepiece 1 (FFP1) masks, subjected them to artificial weathering and studied the environmental degradation behavior of masks. The third gap is the duration of degradation tests, and the influence of humidity/dew/rainwater simulating real environment and types of degradation testing (artificial weathering, in soil, natural sunlight, laboratory conditions). We have considered three different durations, 120 h, 240 h and 360 h for the abiotic degradation test. The 120 h accelerated test is approximately equivalent to 55–60 days of real conditions in South Africa. We have tested masks from 55 days (120 h) to 180 days (360 h) in the accelerated weathering chambers in the presence of humidity/dew/rainwater, simulating actual weathering conditions.

Table 1.

Summary of the literature.

Most of the previous studies so far focus on PP disposable masks with limited environmental abiotic degradation behaviors. There is a lack of studies to understand the degradation behavior of different masks and the influence of physical-chemical factors. In this study, we report on the environmental degradation of cloth, surgical and respirator filter facepiece 1 (FFP1) masks by artificial weathering. Furthermore, physical-chemical properties of masks were characterized by FTIR, Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) and Thermo Gravimetric Analysis (TGA).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

In this study, three different face masks, cloth, surgical and FFP1 masks, were studied (Figure 1). The fiber compositions and physical properties of the mask are given in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Different types of masks, (a) cloth; (b) surgical; and (c) FFP1.

Table 2.

Mask specifications.

2.2. Environmental Accelerated Weathering Testing

QUV accelerated weathering testing chamber (from Q-Lab, Westlake, OH, USA) simulates the effects of natural sunlight and reproduces the damage caused by weathering elements such as sunlight, rain and dew. QUV exposure using UVA-340 lamps as per ISO 4892-3:2024 [22]. In this method, mask test samples were exposed to fluorescent ultraviolet (UV) radiation and water in an apparatus designed to reproduce the weathering effects that occur when materials are exposed in actual end-use environments to daylight, or daylight through window glass. In this test, the test cycles were carried out in two steps: step 1: exposure to UV light at 0.79 W/m2 at 60 °C for 8 h; step 2: condensation at 50 °C for 4 h.

The experiment was performed for 360 h. The test materials were sampled after every 120 h of exposure for further characterization. To estimate the exposure time of the samples in the accelerated aging equipment that corresponds to the reported field period, the following considerations were made. The average solar radiation in South Africa is 16 MJ/m2/day [23]. In 230 days, the total radiation would be 3680 MJ/m2. Of this total, 6.3% (231.8 MJ/m2) constitutes UV A type radiation (UVA), which is responsible for the UV photo degradation of polymers. To estimate the test time, the expected radiation (231.8 MJ/m2) was divided by the daily radiation supplied by the equipment (14.4 MJ/m2). In this test, the test sample exposure in a QUV accelerated weathering for 120 h is approximately equivalent to 55–60 days of real conditions in South Africa.

2.3. Characterization

2.3.1. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

The FTIR technique was utilized to collect Infrared (IR) spectra of the test samples before and after environmental biodegradation. The total reflectance of the mask samples was analyzed on a PerkinElmer IR spectrometer (Shelton, CT, USA), which was obtained in the 500–4000 cm−1 range with 32 scans. After 120, 240 and 360 h QUV environmental weathering testing, test samples were taken for measuring the spectra. IR information of the samples was collected and processed with OMNIC software (version 9.0).

2.3.2. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

Approximately 5–10 mg of test samples were weighed and analyzed in the temperature range of −40 °C to 200 °C under a nitrogen atmosphere using DSC-8500 (PerkinElmer, Branford, CT, USA) for the determination of melting and cold crystallization temperatures, as well as corresponding enthalpies (ΔH’s). Each sample underwent three successive scans of heating, cooling and heating at a rate of 10 °C/min. Melting, crystallinity and heat of enthalpy of test samples were conducted before and after 120, 240 and 360 h of environmental degradation testing. The crystallinity is calculated by dividing the measured heat of crystallization or fusion by the heat of fusion for 100% crystalline PET [24] being 140 J/g and 207 J/g for PP [25].

2.3.3. Thermal Gravimetric Analysis (TGA)

The thermal properties of test samples were evaluated using TGA (Q600 TA Instruments, Eden Prairie, MN, USA). The samples (10–20 mg) were analyzed over a temperature range of 30 to 800 °C, at a heating rate of 10 °C/min by using a nitrogen gas atmosphere. The thermal properties of the test samples were measured before and after 120, 240 and 360 h of environmental degradation testing to determine the changes in onset, derivative degradation, maximum degradation temperature and residue % (by weight) after 600 °C.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. FTIR

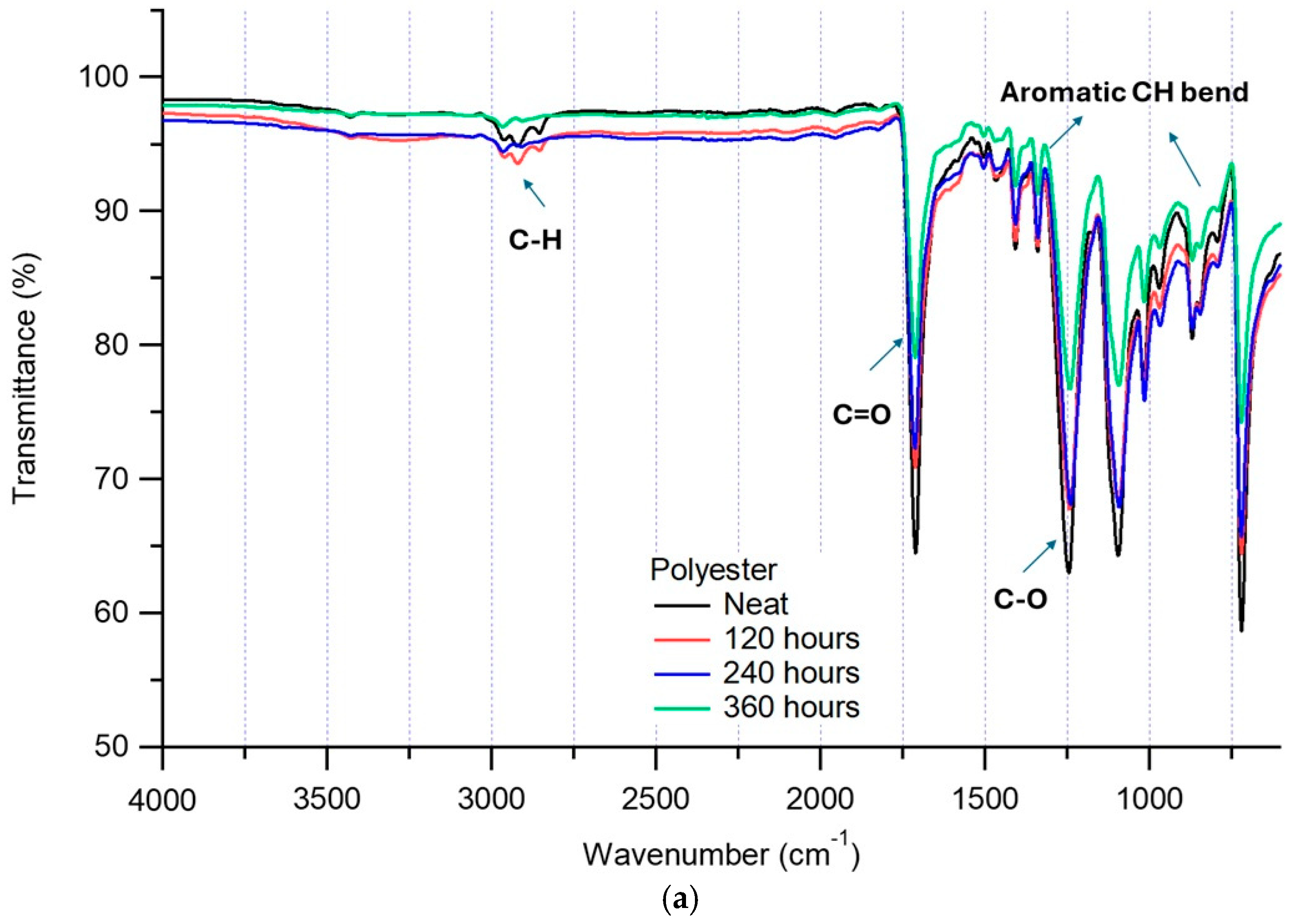

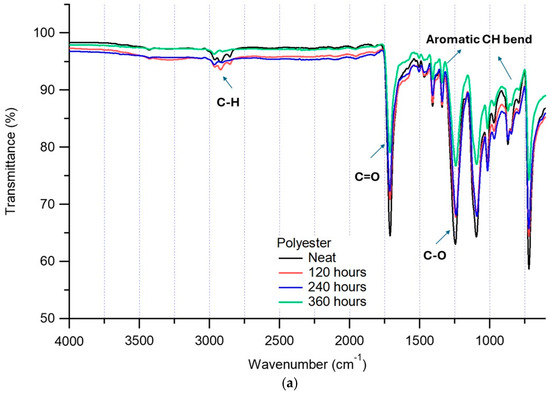

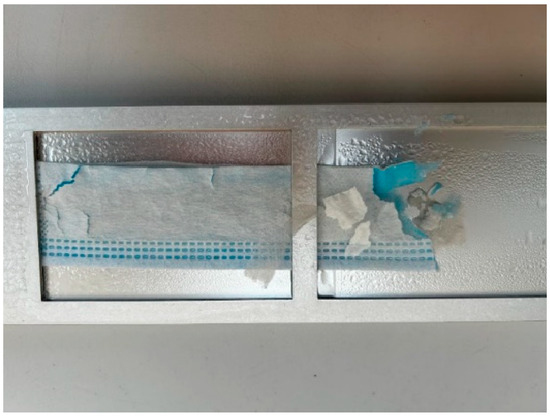

The FTIR results of cloth, surgical and FFP1 masks before and after 120, 240 and 360 h of exposure to the environmental weathering chamber are shown in Figure 2. For the PET cloth mask, there were no significant changes in FTIR spectra as compared to the neat (original) sample for different exposure hours (Figure 2a). The intensities of C-H stretching wavenumbers at 3000–2850, C-H bend 1470 and C-H rock at 1383 and 728 cm−1 did not show any changes after exposure. These results show that PET samples are not degrading with the current exposure hours, where maximum exposure time (360 h) equates to ±180 days. This can be attributed to the high ratio of cross-linked aromatic compounds as compared to the aliphatic compounds, making them resistant to UV degradation [26]. It is expected that the higher exposure of PET under environmental abiotic conditions may undergo chain scission, which leads to low molecular compounds. This mainly occurred at the carbonyl groups (C=O) at 1600–1800 cm−1, but the rate of degradation was mainly influenced by the physical-chemical factors of the PET materials in terms of molecular weight and highly cross-linked aromatic compounds [26].

Figure 2.

(a). FTIR scan of neat (original) PET cloth mask being subjected to different exposure times in the weathering test chamber. (b). FTIR scan of neat (original) PP surgical mask being subjected to different exposure times in the weathering test chamber. (c). FTIR scan of neat (original) FFP1 mask being subjected to different exposure times in the weathering test chamber.

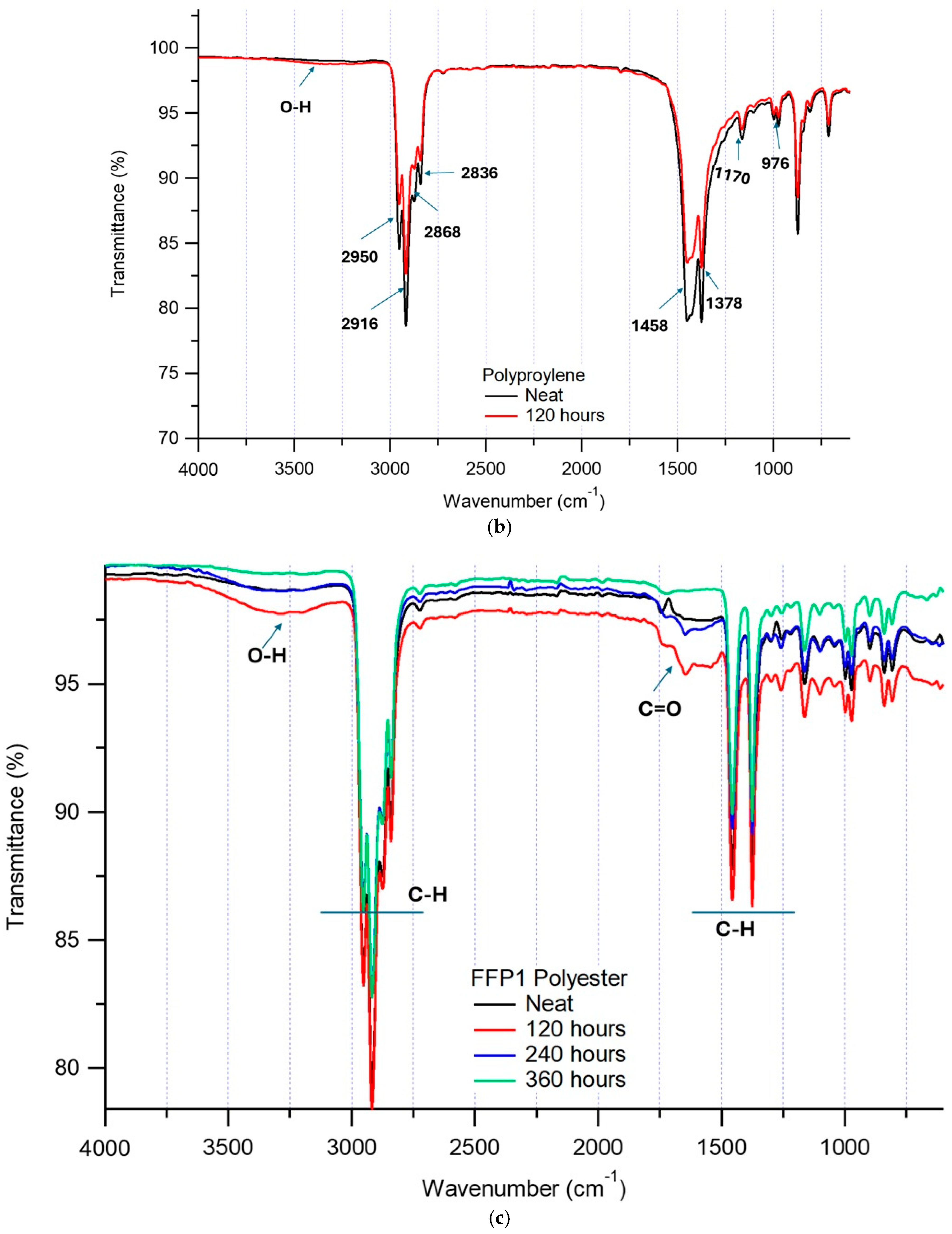

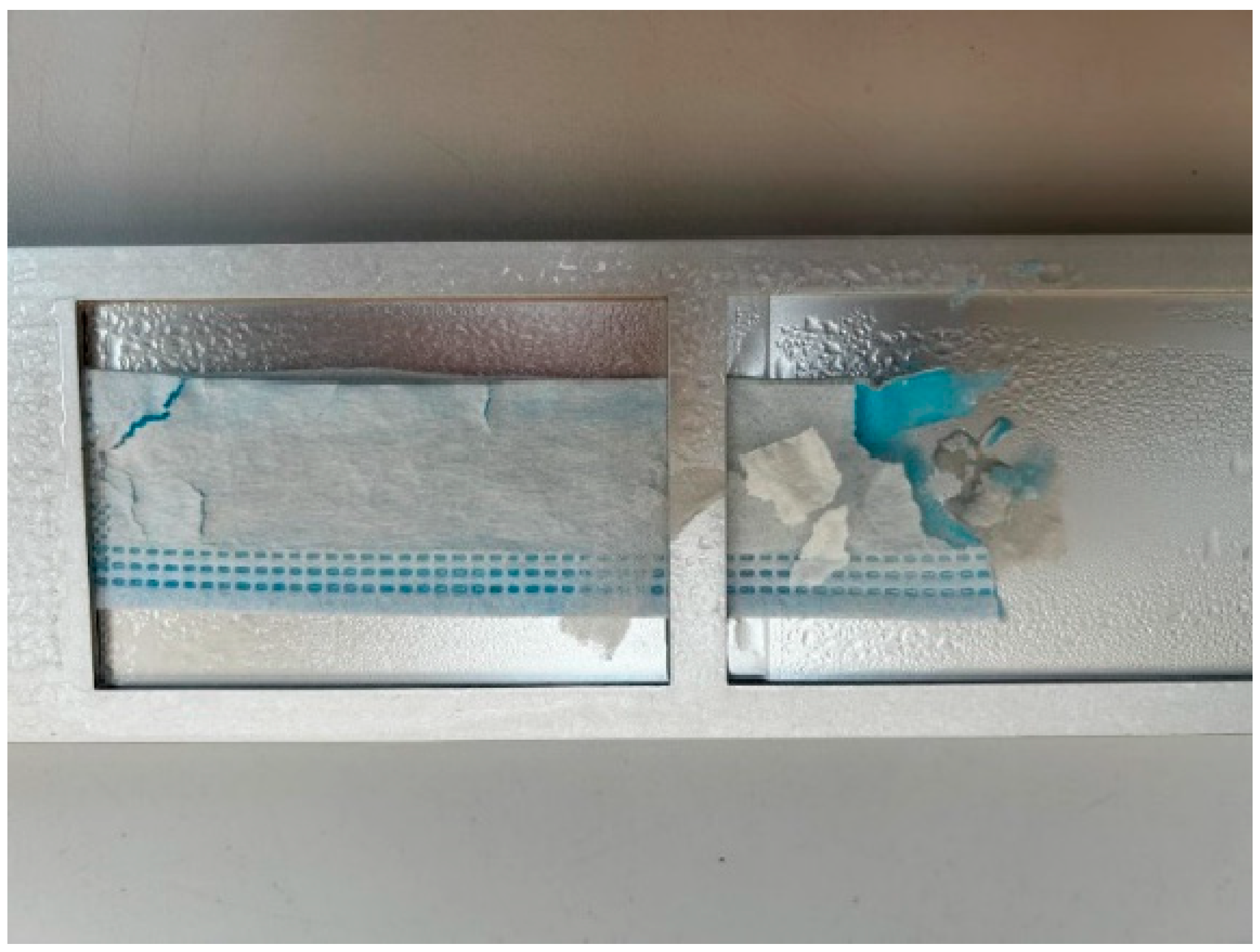

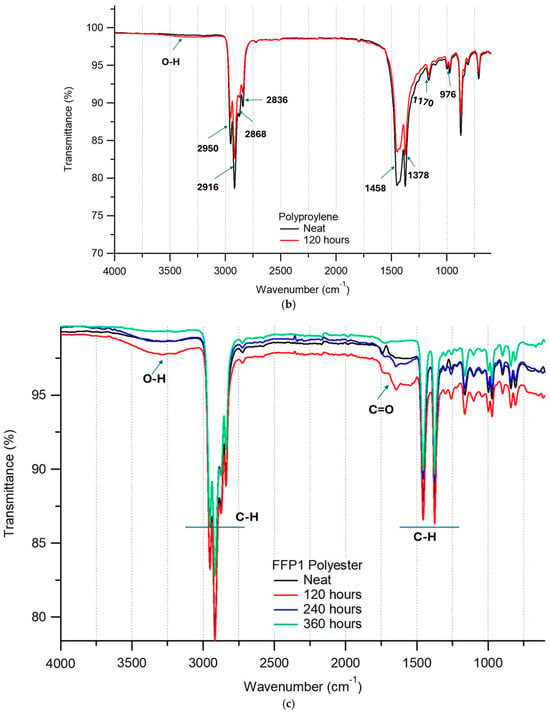

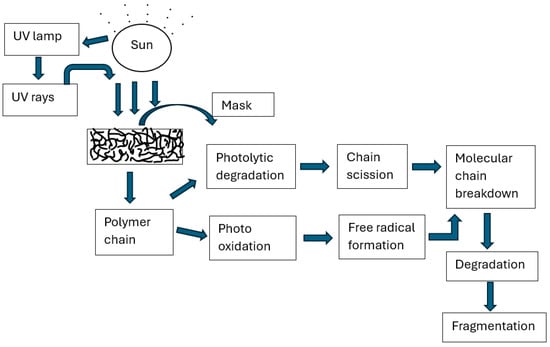

The FTIR scan of the PP surgical mask after 120 h of exposure time shows that it was degraded and broken down to fragments as compared to the neat mask (Figure 2b and Figure 3). It was not possible to conduct further weathering tests after 120 h, as samples were already broken into powder form. FTIR results of fragmented samples showed increase in the peak areas of functional groups, such as hydroxyl (-OH) (wavenumbers 3200–3000 cm−1) and C=O (wavenumbers 1600–1800 cm−1), due to the radical reaction with oxygen to form peroxy radicals. This radical reaction continues to abstract hydrogen from PP chains, creating hydroperoxides (ROOH) and new radical groups to form carbonyl derivatives like keto and esters [26,27].

Figure 3.

PP surgical mask after 120 h of exposure in the weathering test chamber.

Due to this catalytic activity of the photo-oxidation process, PP surgical material becomes brittle and subsequent fragmentation occurred as shown (Figure 2b and Figure 3). During these reactions, a more amorphous region is created as they are susceptible to oxygen and hydrolysis. During the photodegradation process, wavelengths above 290 nm in the UV region were absorbed by chromophores (or impurities). These chromophores release sufficient energy, resulting in chain scissions and formation of radicals that can either combine to form more chromophores or initiate photo-oxidation [27]. Due to the UV degradation, there are changes in the physical, mechanical and chemical properties of PP. On the other hand, there were no significant changes observed for the FFP1 mask, as compared to the neat sample for different exposure hours (Figure 2c). As compared to cloth masks, the functional groups of the FFP1 test sample showed a slight increase in the OH regions at 3000–3200 cm−1 and decreased intensity in the carbon groups at 1600–1800 cm−1 (Figure 2c). These results indicate that the test samples containing low molecular weight compounds of amorphous regions are degrading through the hydrolytic chain scission process [26,27].

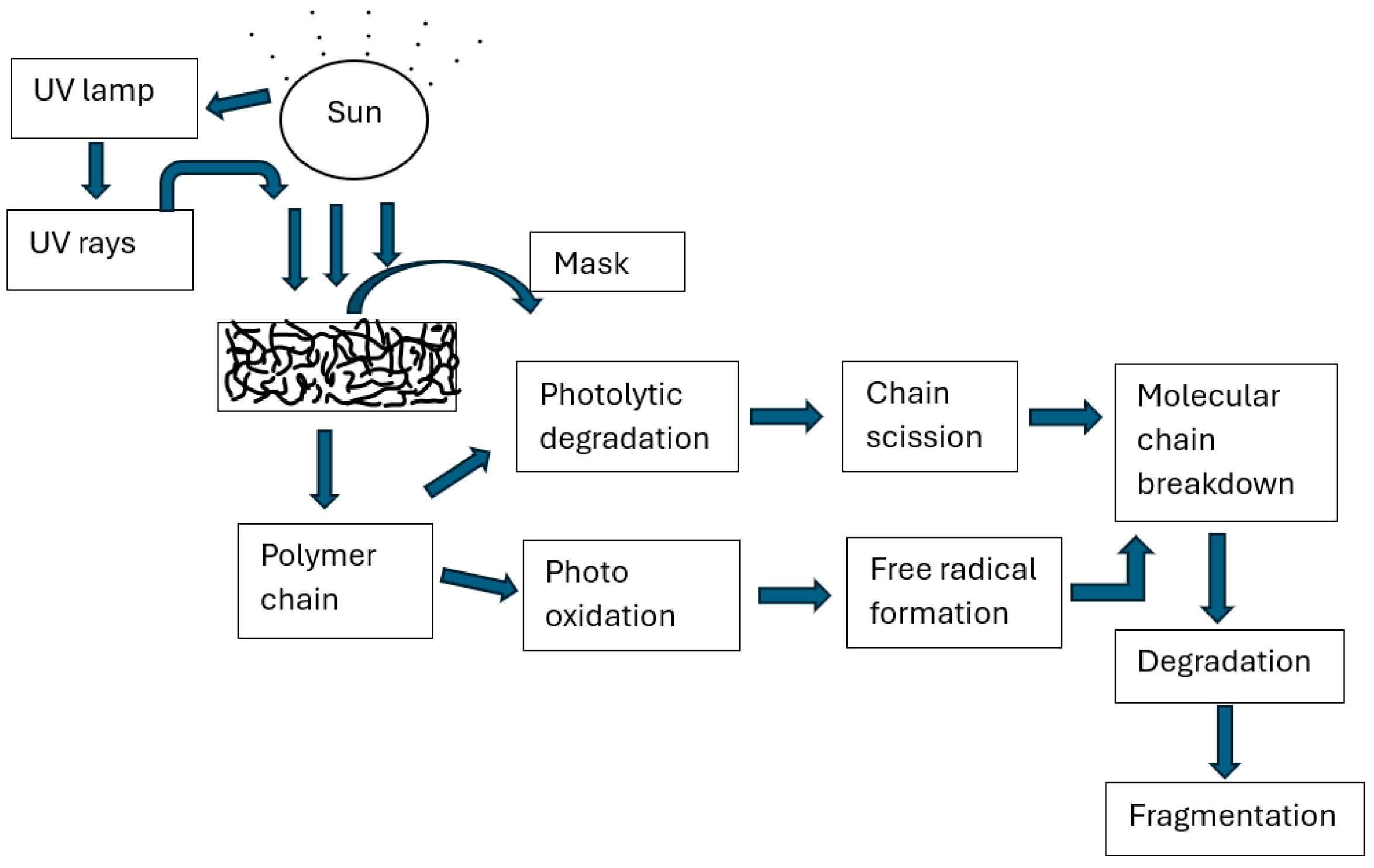

The degradation mechanism of a mask subjected to artificial weathering is depicted in Scheme 1. The mask was subjected to artificial weathering in the QUV chamber. The constituent fibers in the mask and associated polymer chains of the fibers undergo photolytic degradation and photo-oxidation as a result of UV exposure. During the photolytic degradation process, chromophores or impurities in a material absorb UV light at wavelengths above 290 nanometers. This absorption of energy leads to the breakdown of polymer chains and the formation of free radicals. These free radicals can either combine to form more chromophores or initiate photo-oxidation. Since the amorphous region of a material is more vulnerable to oxygen, these degradation reactions predominantly occur there. UV exposure causes chain scission and breaks down the main backbone of the polymer chain. As a result, the mask was brittle, degraded and broken down into fragments [27,28].

Scheme 1.

Degradation mechanism of a mask subjected to artificial weathering.

3.2. DSC

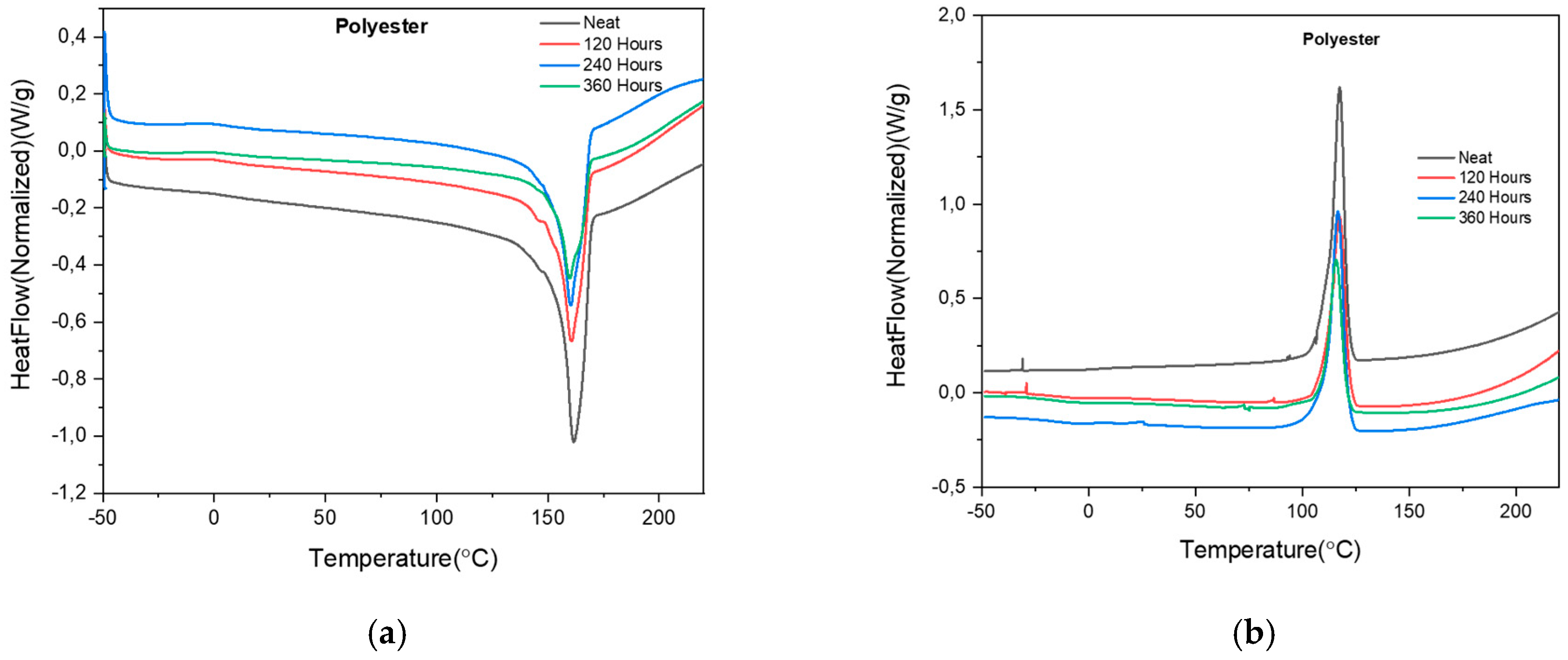

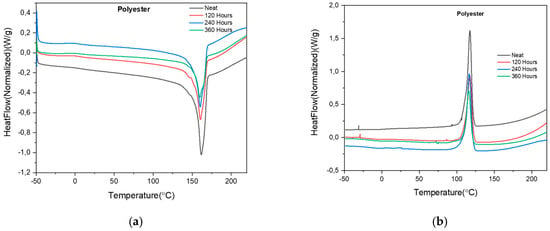

The DSC results of the neat PET cloth mask and mask exposed to 120, 240 and 360 h in the QUV weathering chamber are shown in Table 3. There is not much difference in the melting temperature (Tm), as shown in Figure 4a and the first cold crystallization temperature of the neat PET cloth mask and QUV exposed masks, Figure 4b. There was a 58% decrease in the crystallinity and heat of enthalpy after 120 h of QUV exposure. UV degradation breaks down the orderly polymer chain and induces defects in the molecular chain, resulting in lower crystallinity [28]. These changes indicate that more amorphous regions were created after exposure to UV light and causing chemical degradation in the material [29,30]. Exposure to UV causes chain scission and breaks down the ester bond, which is the backbone of the PET. It further affects by reducing molecular weight and forming more amorphous regions [31,32]. There is not much change in the 240 h QUV exposure as compared to the 120 h exposure. In the 360 h QUV exposure, there were further degradations in the mask samples, with further decreases in the crystallinity and heat of enthalpy. A different glass transition temperature (Tg °C) was observed for both the PET cloth mask and the mask exposed to different hours in QUV. This could be attributed to the different phase shifts in the material, with an initial higher Tg for the neat material and further reduction in Tg as there are continuous changes in the material phases.

Table 3.

DSC results of the neat PET cloth mask and 120, 240 and 360 h QUV exposed masks.

Figure 4.

(a) DSC scan of PET cloth masks showing melting temperature, Tm (°C); (b) DSC scan of PET cloth masks showing first cold crystallization temperature, Tcc1st (°C).

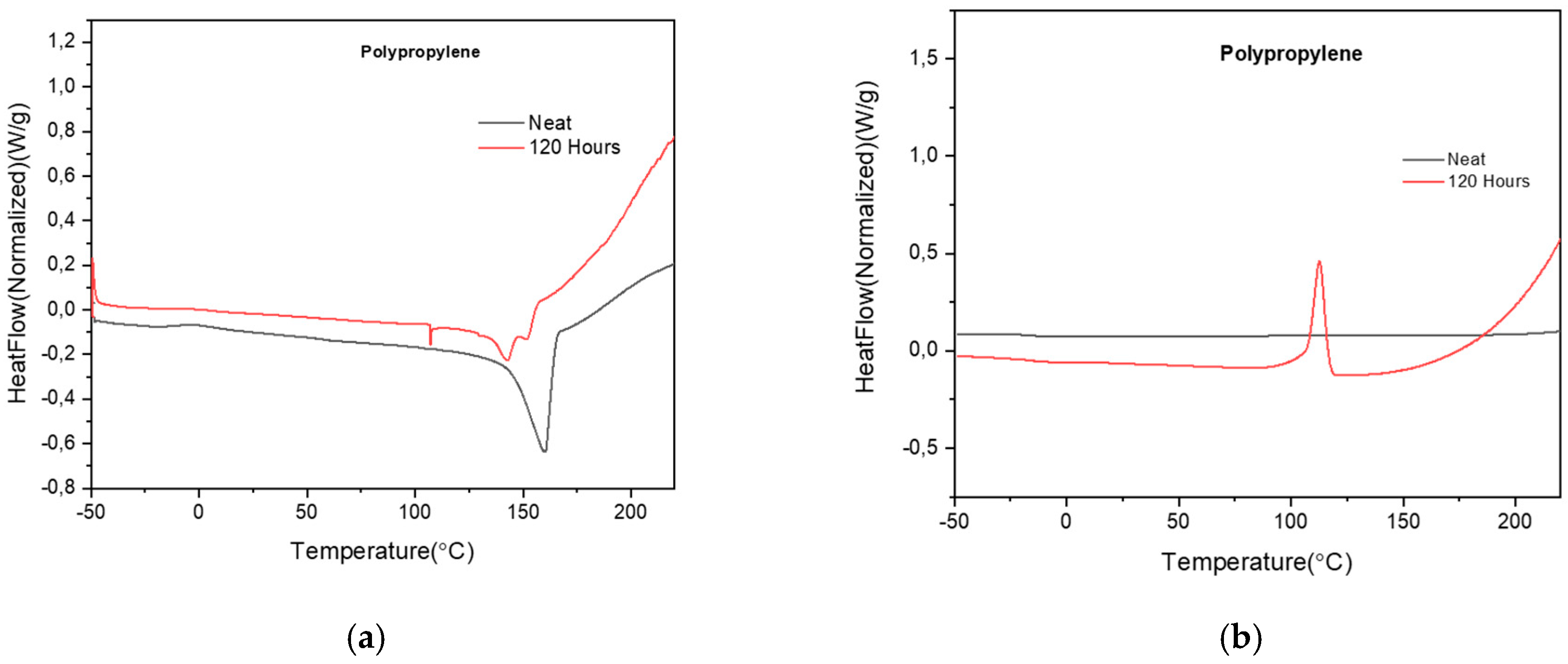

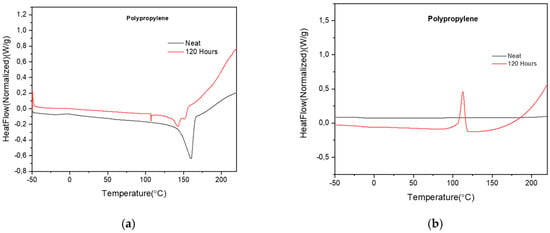

The DSC results of the neat PP surgical mask and the mask exposed to 120, 240 and 360 h in the QUV weathering chamber are shown in Table 4. There is not much difference in the melting temperature (Tm) and first cold crystallization temperature (Tcc1st) of the neat PP surgical masks and the QUV exposed masks (Figure 5a,b), but a significant drop in the crystallinity (88%) and heat of enthalpy (88%) after 120 h of QUV exposure is observed and masks are brittle and fragmented, with some portions of the QUV exposed masks having disintegrated into powder form. The reason is due to both photolytic degradation and the photo-oxidation process happening in the amorphous region, causing chemical degradation (chain scission and free radical formation) in the material and breaking down the carbon-methyl backbone of the polymer chain [33,34]. The breaking down of molecular chains results in a significant decrease in molecular weight [31,32]. These results are similar to the FTIR result as explained in the previous section. Since there was a difference in crystallinity between the neat PP surgical mask and the 120 h QUV exposed mask, it led to different Tg (°C) in different layers.

Table 4.

DSC results of neat PP surgical mask and 120, 240 and 360 h QUV exposed masks.

Figure 5.

(a) DSC scan of PP surgical masks showing melting temperature, Tm (°C); (b) DSC scan of PP surgical masks showing first cold crystallization temperature, cold crystallization Tcc 1st (°C).

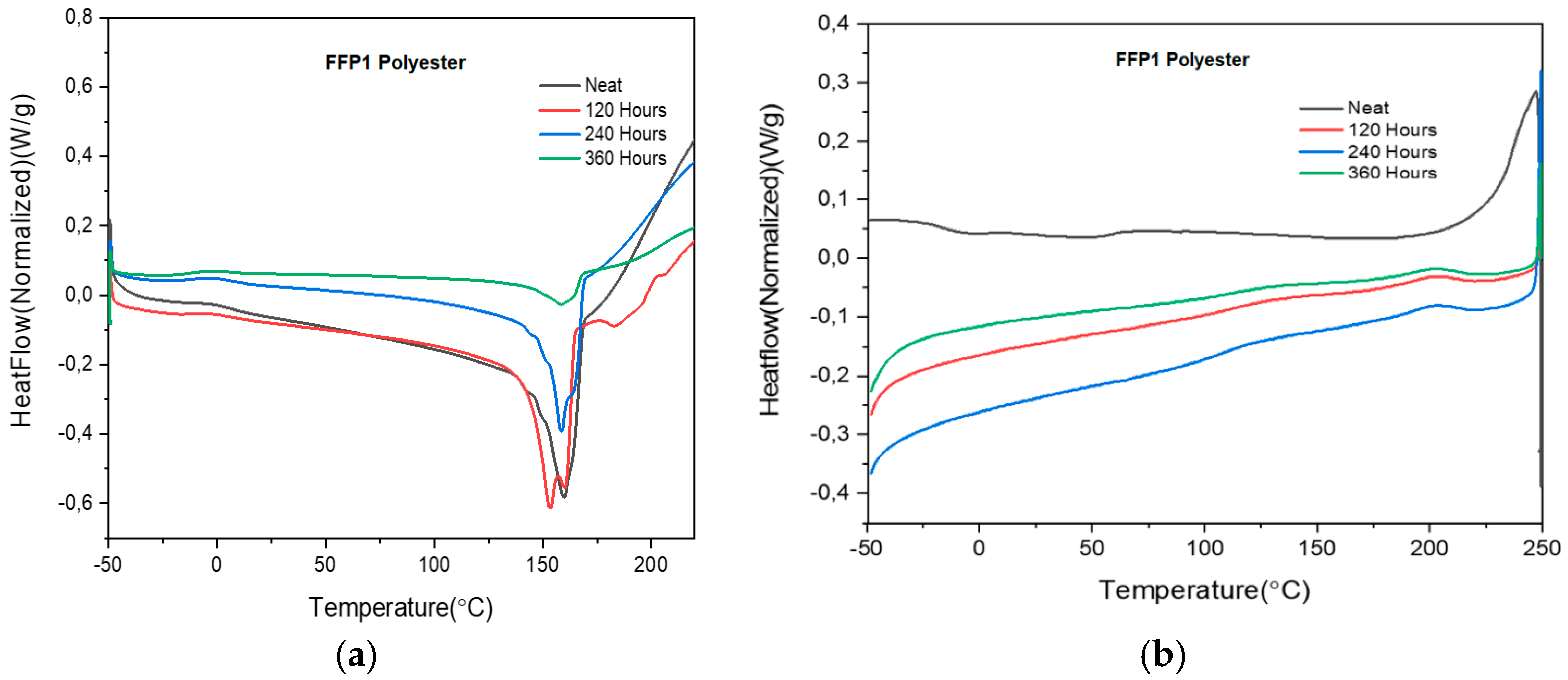

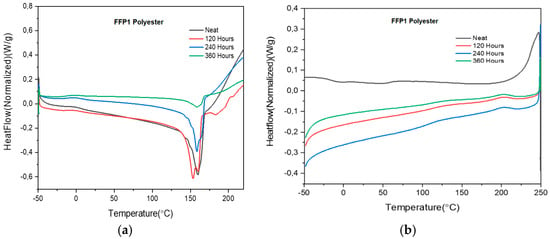

The chemical degradation trends of the PET FFP1 mask and 120, 240 and 360 h QUV exposed masks are like that of the PET cloth mask (Table 5). The notable difference between them is the difference in crystallinity in the neat material which subsequently affects degradation behavior (Table 5). As the PET FFP1 masks were exposed to 120, 240 and 360 h in QUV, the reduction in crystallinity as compared to the neat mask is 48%, 56% and 90%, respectively. As a result of it, subsequent changes are observed in the Tm (Figure 6a,b); particularly, there was a drastic reduction in enthalpy at 360 h of QUV exposure.

Table 5.

DSC results of neat PET FFP1 mask and 120, 240 and 360 h QUV exposed masks.

Figure 6.

(a) DSC scan of PET FFP1 mask showing melting temperature, Tm (°C); (b) DSC scan of PET FFP1 mask showing cold crystallization, Tcc (°C).

3.3. TGA

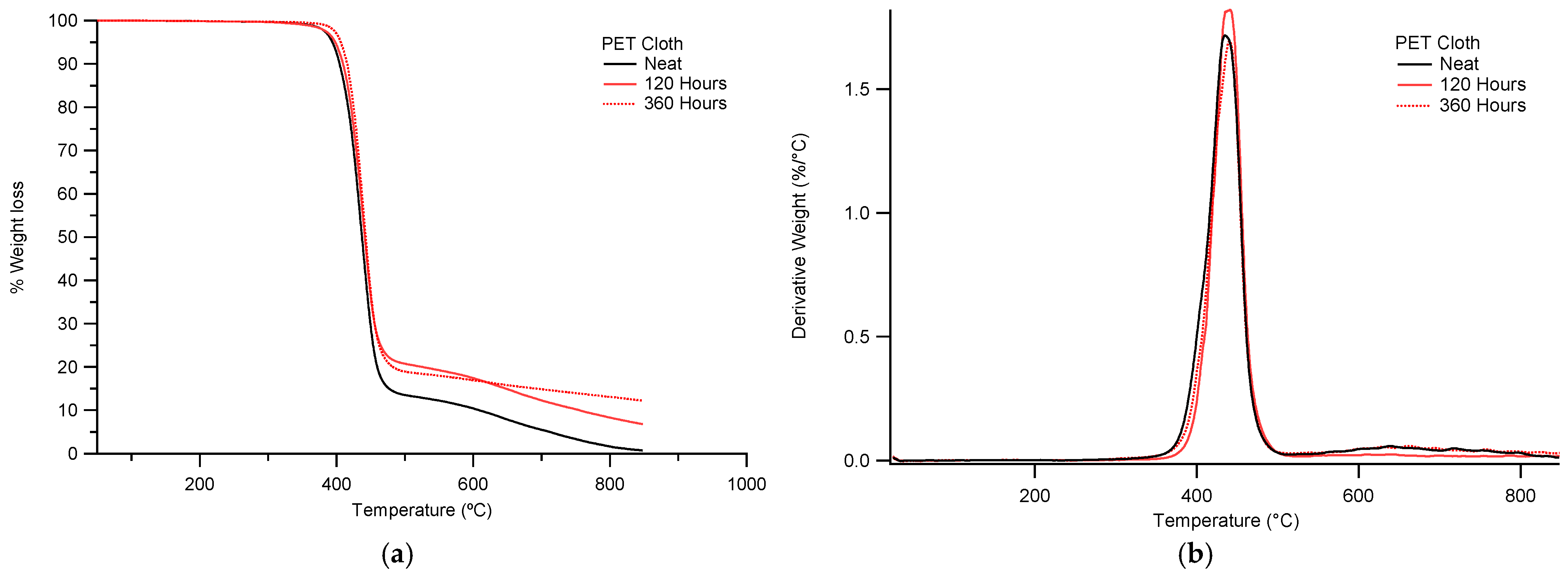

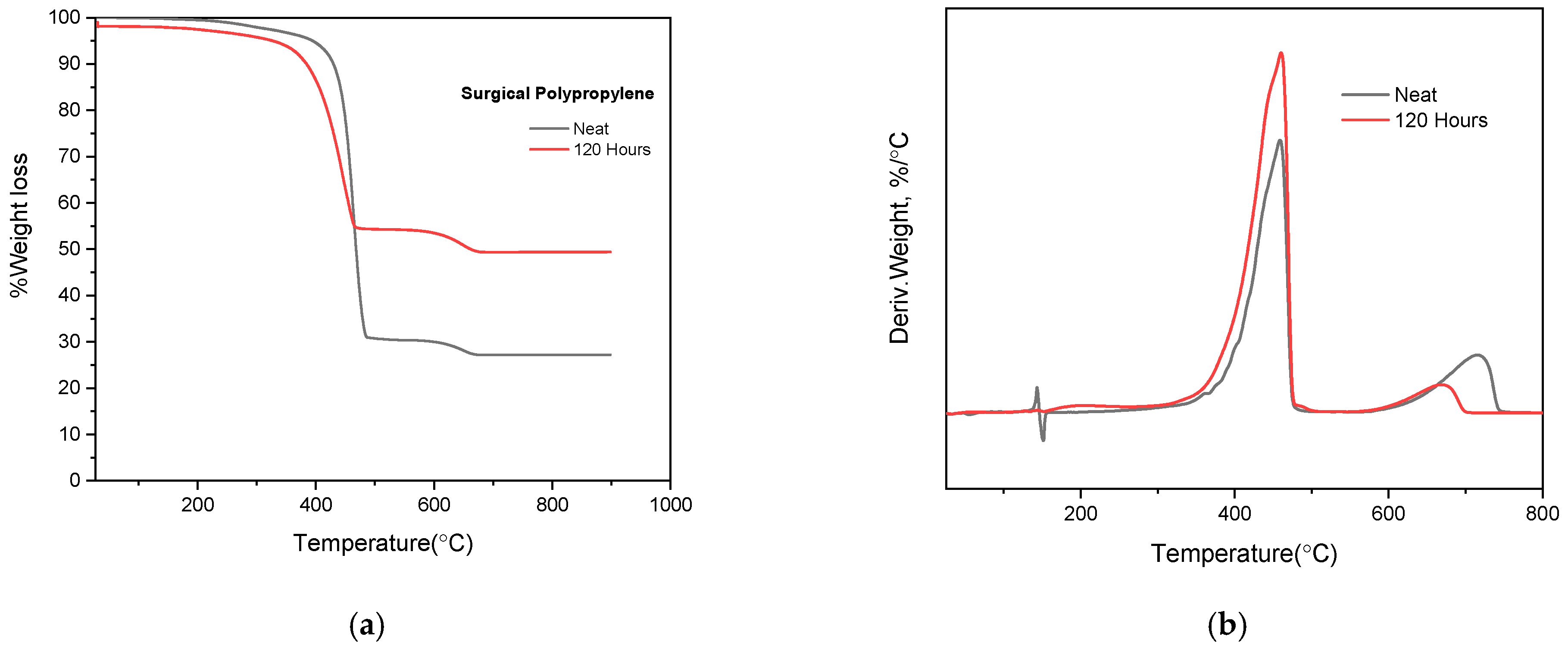

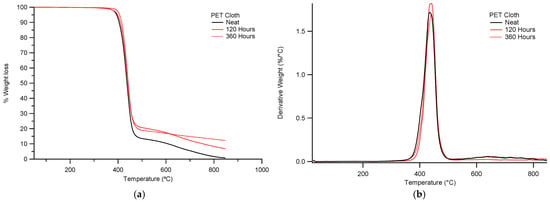

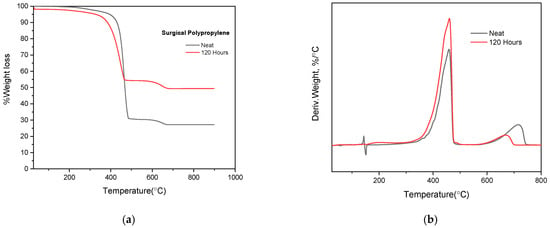

The TGA results of neat PET cloth masks subjected to 120, 240 and 360 h are depicted in Table 6. The weight loss and TGA derivatives curves are shown in Figure 7a,b.

Table 6.

TGA results of the neat PET cloth mask and 120, 240 and 360 h QUV exposed masks.

Figure 7.

(a) TGA weight loss degradation behaviors of PET cloth mask before and after 120, 240 and 360 h of QUV exposure, (b) TGA derivative graphs of PET cloth mask before and after 120, 240 and 360 h QUV exposure.

The cloth masks TGA results showed higher Tonset temperatures of 361.71 °C, 397.71 °C and 404.66 °C, respectively, before and after 120 and 240 h of QUV exposure. The increased Tonset temperatures could be due to the degradation of low molecular compounds where minor amorphous groups were present (Table 6 and Figure 7a,b). The highest degradation temperatures of cloth mask showed decreases at 472.5 °C, 469.5 °C and 452.6 °C, respectively. These findings show that the bulk materials have undergone some hydrolytic breakdown. The cloth mask Tonset and maximum degradation temperatures, however, were nearly identical after 360 h of QUV exposure as opposed to 240 h. These findings show that the photo-oxidation process is hampered by the high ratio of cross-linked aromatic molecules (Table 6 and Figure 7a,b). The Derivative of the Thermo Gravimetric (DTG) curve and its peak height represent the rate of thermal decomposition at specific temperatures (Figure 7b and Figure 8b). The PET cloth mask test sample after 120 h of QUV exposed testing showed a higher peak height at 400–500 °C as compared to untreated and 360 h QUV exposed test samples (Figure 7b). These results indicate that a higher rate of thermal decomposition occurs at 120 h QUV exposure due to the mass loss of amorphous groups of the PET cloth mask during the photo-oxidation process. On the other hand, after 360 h QUV exposure, derivative peak height is slightly lower than after 120 h QUV exposure, which indicates that after 120 h of QUV exposure test samples became crystalline groups more so than amorphous. It is known that amorphous groups undergo higher rates of decomposition than crystalline groups. A similar degradation mechanism was observed for the PP surgical mask after 120 h QUV exposure (Figure 8a,b).

Figure 8.

(a) TGA weight loss degradation behaviors of the PP surgical mask before and after 120 h QUV exposure, (b) TGA derivative graphs of the neat PP surgical mask before and after 120 h QUV exposure.

The TGA results of the neat PP surgical mask and 120 h QUV exposed mask are depicted in Table 7. As expected, the neat PP surgical mask has higher Tonset (°C) and Tmax (°C) temperatures as compared to the 120 h QUV exposed mask (Figure 8a,b) due to its higher crystallinity. It creates a stronger bond among the molecular chain and resists thermal degradation. Once masks are exposed to 120 h in QUV, there was a shift in Tonset (°C) and Tmax (°C) temperature values, resulting in lower temperatures due to the thermal degradation of the molecular chains [35]. At 600 °C, 32% residue (by weight %) was left in the case of a neat PP surgical mask and 55% residue was left in the case of 120 h QUV exposed mask. It can be attributed to the presence of additives or fillers in the PP polymer [36].

Table 7.

TGA results of the neat PP surgical mask and 120 h QUV exposed mask.

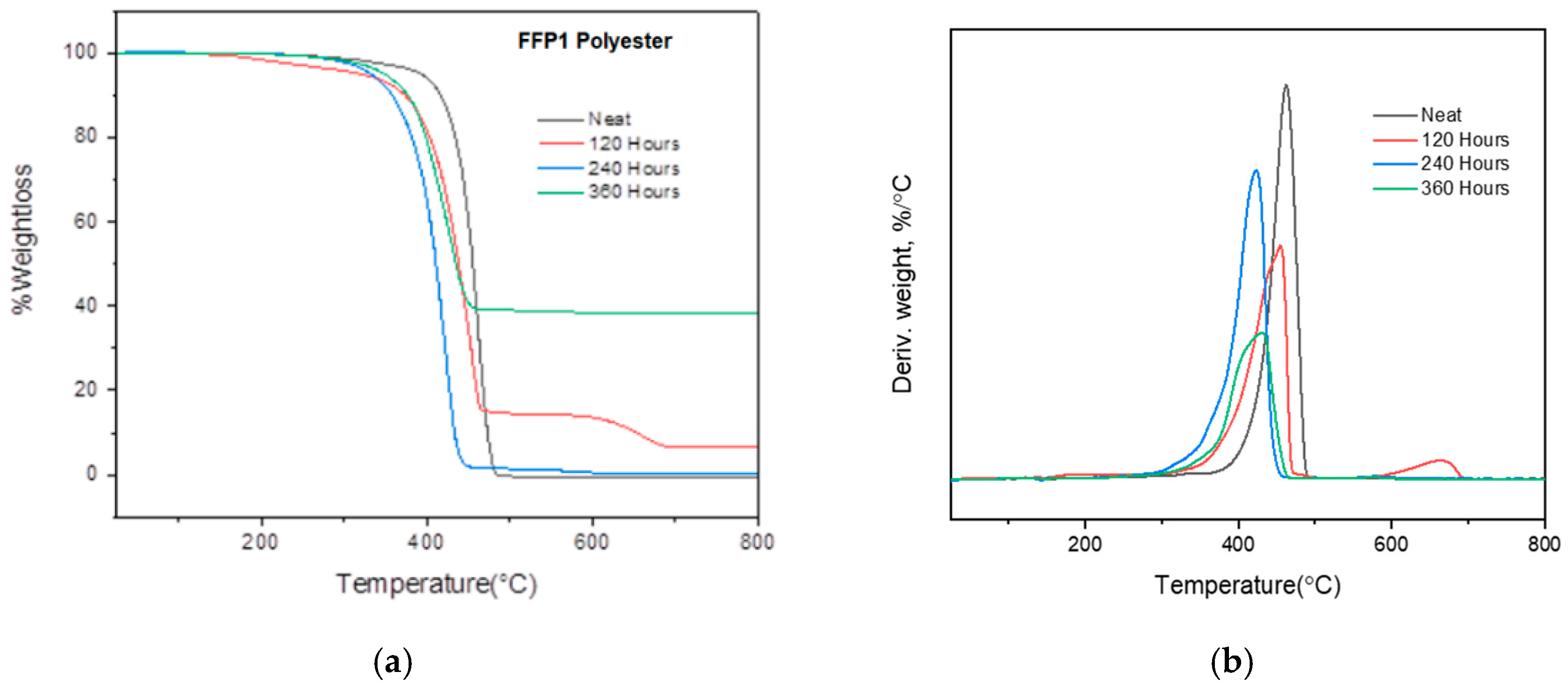

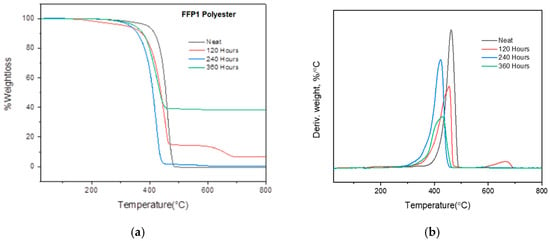

The TGA results of the neat PET FFP1 mask and 120, 240 and 360 h QUV exposed masks are depicted in Table 8. As compared to other PP and cloth mask test samples, neat PET FFP1 masks have higher Tonset (°C) and Tmax (°C) temperatures as compared to the 120, 240 and 340 h QUV exposed masks (Figure 9a,b) due to their higher crystallinity. As a result, neat PET FFP1 masks have better resistance to thermal degradation. After exposing masks to different hours in QUV, Tonset (°C) and Tmax (°C) temperatures decrease for all exposing hours due to chain scission, except Tmax (°C) for 360 h, which could be due to the presence of any additives/impurities [21]. At 600 °C, 5–18% residues (by weight %) were left in the case of the neat PET FFP1 masks and the 120, 240 h QUV exposed masks. About 55% residue left in the case of the 360 h QUV exposed mask, which could be attributed to the presence of additives/fillers in the polymer.

Table 8.

TGA results of the PET FFP1 mask before and after 120, 240 and 360 h QUV exposure.

Figure 9.

(a) TGA weight loss degradation behaviors of the PET FFP1 mask before and after 120, 240 and 340 h QUV exposure, (b) TGA derivative degradation of the PET FFP1 mask before and after 120, 240 and 340 h QUV exposure.

4. Conclusions

Environmental degradation of cloth, surgical and FFP1 masks by accelerated artificial weathering was studied in this paper. The physical-chemical properties of the masks were characterized by FTIR, DSC and TGA. FTIR results showed that the PET cloth mask and the FFP1 PET mask were not degraded after 360 h of UV exposure, whereas the PP mask was degraded into fragments after 120 h of UV exposure. UV exposure causes a chain scission reaction and free radical formation, breaking down the carbon-methyl backbone in the PP mask. A drastic reduction in crystallinity was observed when comparing original PET FFP1 masks with FFP1 masks exposed to different UV hours. After 120 h of UV exposure, the PET cloth mask showed a 58% reduction in crystallinity and heat of enthalpy. Neat PET cloth and FFP1 masks have better resistance to thermal degradation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.M. and A.P.; methodology, S.M.; validation, A.P. and S.M.; formal analysis, A.P.; investigation, S.M.; resources, A.P.; data curation, S.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.P.; writing—review and editing, S.M.; project administration, A.P.; funding acquisition, A.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Research Foundation, NRF, South Africa, grant number 132153.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rowan, N.J.; Laffey, J.G. Unlocking the surge in demand for personal and protective equipment (PPE) and improvised face coverings arising from coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic–implications for efficacy, re-use and sustainable waste management. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 752, 142259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordova, M.R.; Nurhati, I.S.; Riani, E.; Iswari, M.Y. Unprecedented plastic-made personal protective equipment (PPE) debris in river outlets into Jakarta Bay during COVID-19 pandemic. Chemosphere 2021, 268, 129360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maduna, L.; Patnaik, A. The use of fibrous face masks as a barrier against infectious biological airborne particles. J. Ind. Text. 2023, 53, 15280837221148464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhbarizadeh, R.; Dobaradaran, S.; Nabipour, I.; Tangestani, M.; Abedi, D.; Javanfekr, F.; Jeddi, F.; Zendehboodi, A. Abandoned Covid-19 personal protective equipment along the Bushehr shores, the Persian Gulf: An emerging source of secondary microplastics in coastlines. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 168, 112386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejjad, N.; Cherif, E.K.; Rodero, A.; Krawczyk, D.A.; El Kharraz, J.; Moumen, A.; Laqbaqbi, M.; Fekri, A. Disposal behavior of used masks during the COVID-19 pandemic in the Moroccan community: Potential environmental impact. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spennemann, D.H. COVID face masks: Policy shift results in increased littering. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De-la-Torre, G.E.; Aragaw, T.A. What we need to know about PPE associated with the COVID-19 pandemic in the marine environment. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 163, 111879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, P.; Pradhan, I.P.; Kumar, D. Redefining bio medical waste management during COVID-19 in India: A way forward. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 60, 849–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaur, V.K.; Sirohi, R.; Bhat, M.I.; Gautam, K.; Sharma, P.; Srivastava, J.K.; Pandey, A. A review on the effect of micro-and nano-plastics pollution on the emergence of antimicrobial resistance. Chemosphere 2023, 311, 136877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, T.; Li, Y.; Rob, M.M.; Cheng, H. Microplastic pollution in Bangladesh: Research and management needs. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 308, 119697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Wang, J.; Wu, F.; Xu, S.; Liu, J.; Chen, J. Extensive abundances and characteristics of microplastic pollution in the karst hyporheic zones of urban rivers. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 857, 159616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, L.; Li, L.; Xiao, J.; Zhou, P.; Han, X.; Shen, B.; Dai, L. Microplastics in the Environment: A Review Linking Pathways to Sustainable Separation Techniques. Separations 2025, 12, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De-la-Torre, G.E.; Dioses-Salinas, D.C.; Dobaradaran, S.; Spitz, J.; Keshtkar, M.; Akhbarizadeh, R.; Abedi, D.; Tavakolian, A. Physical and chemical degradation of littered personal protective equipment (PPE) under simulated environmental conditions. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2022, 178, 113587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, P.-I.; Gao, Z.; Jung, M.; Song, M.; Jun, Y.-S. Photolysis of disposable face masks facilitates abiotic manganese oxide formation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 493, 138246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, L.; Wang, Z.; Bagchi, M.; Ye, Z.; Soliman, A.; Bagchi, A.; Markoglou, N.; Yin, J.; An, C.; Yang, X.; et al. An investigation into the aging of disposable face masks in landfill leachate. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 446, 130671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Pei, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ma, J. Weathering and degradation of polylactic acid masks in a simulated environment in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and their effects on the growth of winter grazing ryegrass. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 448, 130889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spennemann, D.H. Environmental decay of single use surgical face masks as an agent of plastic micro-fiber pollution. Environments 2022, 9, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knicker, H.; Velasco-Molina, M. Biodegradability of disposable surgical face masks littered into soil systems during the COVID 19 pandemic—A first approach using microcosms. Soil Syst. 2022, 6, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Shi, W. Post-Pandemic: Investigation of the Degradation of Various Commercial Masks in the Marine Environment. Langmuir 2023, 39, 10553–10564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A.M.; Silva, A.L.P.; Soares, A.M.; Barceló, D.; Duarte, A.C.; Rocha-Santos, T. Current knowledge on the presence, biodegradation, and toxicity of discarded face masks in the environment. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 109308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bigault De Cazanove, P.F.; Vdovchenko, A.; Rose, R.S.; Resmini, M. The role of artificial weathering protocols on abiotic and bacterial degradation of polyethylene. Polymers 2025, 17, 1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ISO 4892-3:2016; Plastics-Methods of Exposure to Laboratory Light Sources Part 3: Fluorescent UV Lamps. ISO Central Secretariat: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024.

- Clean Energy. 2025. Available online: https://www.dmre.gov.za/Portals/0/Energy_Website/files/media/Pub/CleanEnergy_A5booklet.pdf (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Thomsen, T.B.; Hunt, C.J.; Meyer, A.S. Influence of substrate crystallinity and glass transition temperature on enzymatic degradation of polyethylene terephthalate (PET). New Biotechnol. 2022, 69, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanyi, F.J.; Wenzke, N.; Kaschta, J.; Schubert, D.W. On the determination of the enthalpy of fusion of α-crystalline isotactic polypropylene using differential scanning calorimetry, x-ray diffraction, and fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy: An old story revisited. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2020, 22, 1900796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swamy, T.C.; Nagarathna, S.; Reddy, P.V.; Nayak, A.S. Efficient biodegradation of Polyethylene terephthalate (PET) plastic by Gordonia sp. CN2K isolated from plastic contaminated environment. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 281, 116635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massardier, V.; Louizi, M. Photodegradation of a polypropylene filled with lanthanide complexes. Polímeros 2015, 25, 515–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gok, A.; Fagerholm, C.L.; Gordon, D.A.; Bruckman, L.S.; French, R.H. Degradation of poly (ethylene-terephthalate) under accelerated weathering exposures. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE 42nd Photovoltaic Specialist Conference (PVSC), New Orleans, LA, USA, 14–19 June 2015; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Falkenstein, P.; Gräsing, D.; Bielytskyi, P.; Zimmermann, W.; Matysik, J.; Wei, R.; Song, C. UV pretreatment impairs the enzymatic degradation of polyethylene terephthalate. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhoodi, M.; Mousavi, S.; Sotudeh-Gharebagh, R.; Emam-Djomeh, Z.; Oromiehie, A.; Mansour, H. A study on physical aging of semicrystalline polyethylene terephthalate below the glass transition point. J. Appl. Res. Technol. 2012, 10, 698–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kteeba, S.M.; Guo, L. UV-induced release and characterization of dissolved organic matter from disposable face mask layers and polypropylene. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 496, 139438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Chen, F.; Xu, H.; Liu, J.; Chen, C.C.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, H.; Li, Y.; Pan, K. Fate of face masks after being discarded into seawater: Aging and microbial colonization. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 436, 129084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogotov, I.; Barazov, S.K. The effect of ultraviolet light and temperature on the degradation of composite polypropylene. Int. Polym. Sci. Technol. 2014, 41, 55–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meides, N.; Mauel, A.; Menzel, T.; Altstädt, V.; Ruckdäschel, H.; Senker, J.; Strohriegl, P. Quantifying the fragmentation of polypropylene upon exposure to accelerated weathering. Microplastics Nanoplastics 2022, 2, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmizadeh, E.; Tzoganakis, C.; Mekonnen, T.H. Degradation behavior of polypropylene during reprocessing and its biocomposites: Thermal and oxidative degradation kinetics. Polymers 2020, 12, 1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nugroho, R.A.A.; Alhikami, A.F.; Wang, W.-C. Thermal decomposition of polypropylene plastics through vacuum pyrolysis. Energy 2023, 277, 127707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).