Modeling of Tar Removal in a Partial Oxidation Burner: Effect of Air Injection on Temperature, Tar Conversion, and Soot Formation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Mathematical Model and Data Evaluation

2.1. Combustion Model

2.1.1. Non-Premixed Combustion Model

2.1.2. Eddy-Dissipation Concept Model

2.2. Kinetic Model

2.3. Data Evaluation

3. Introduction of Research Objectives and Grid Validation

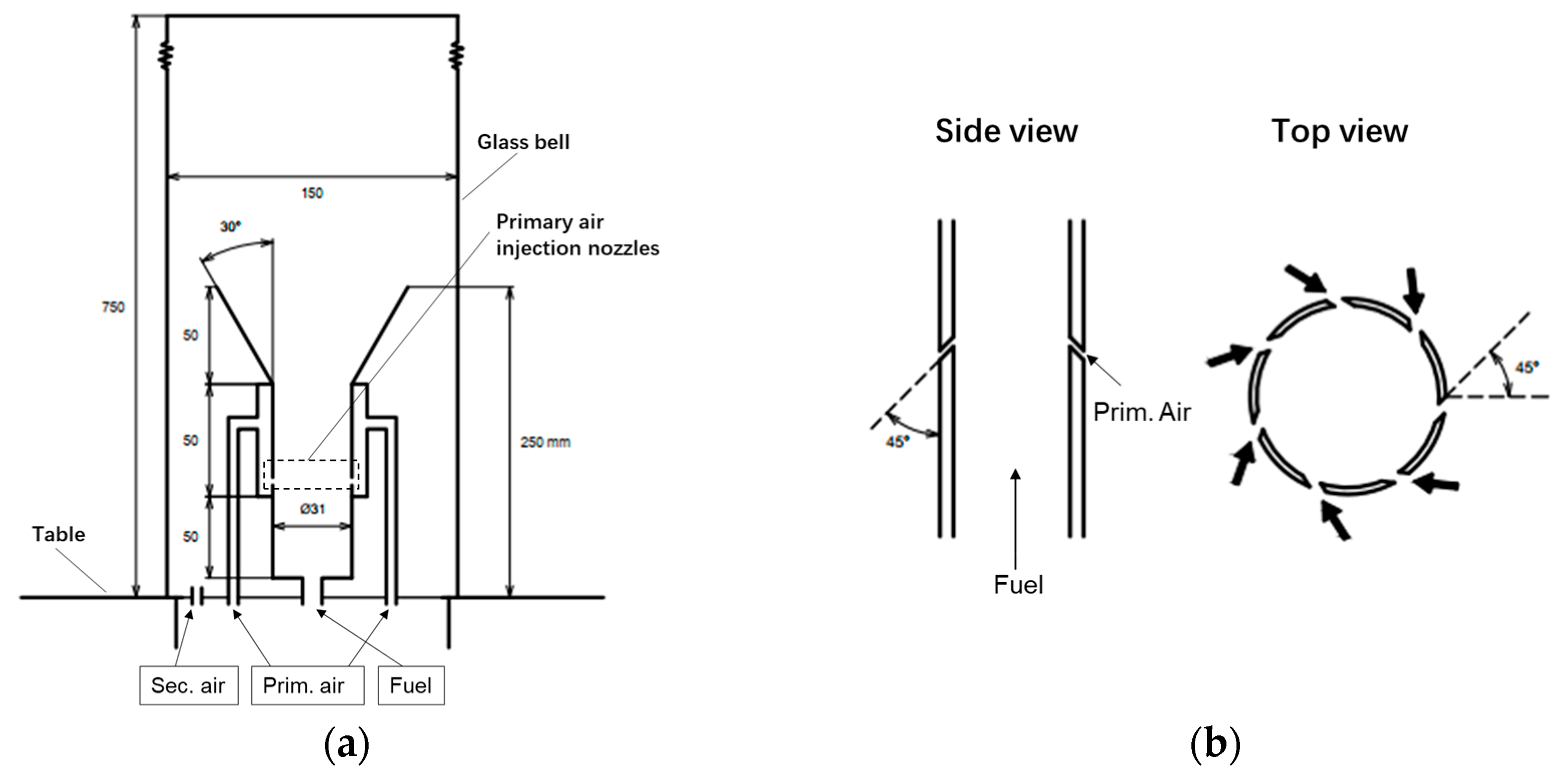

3.1. Introduction of the Combustion Equipment

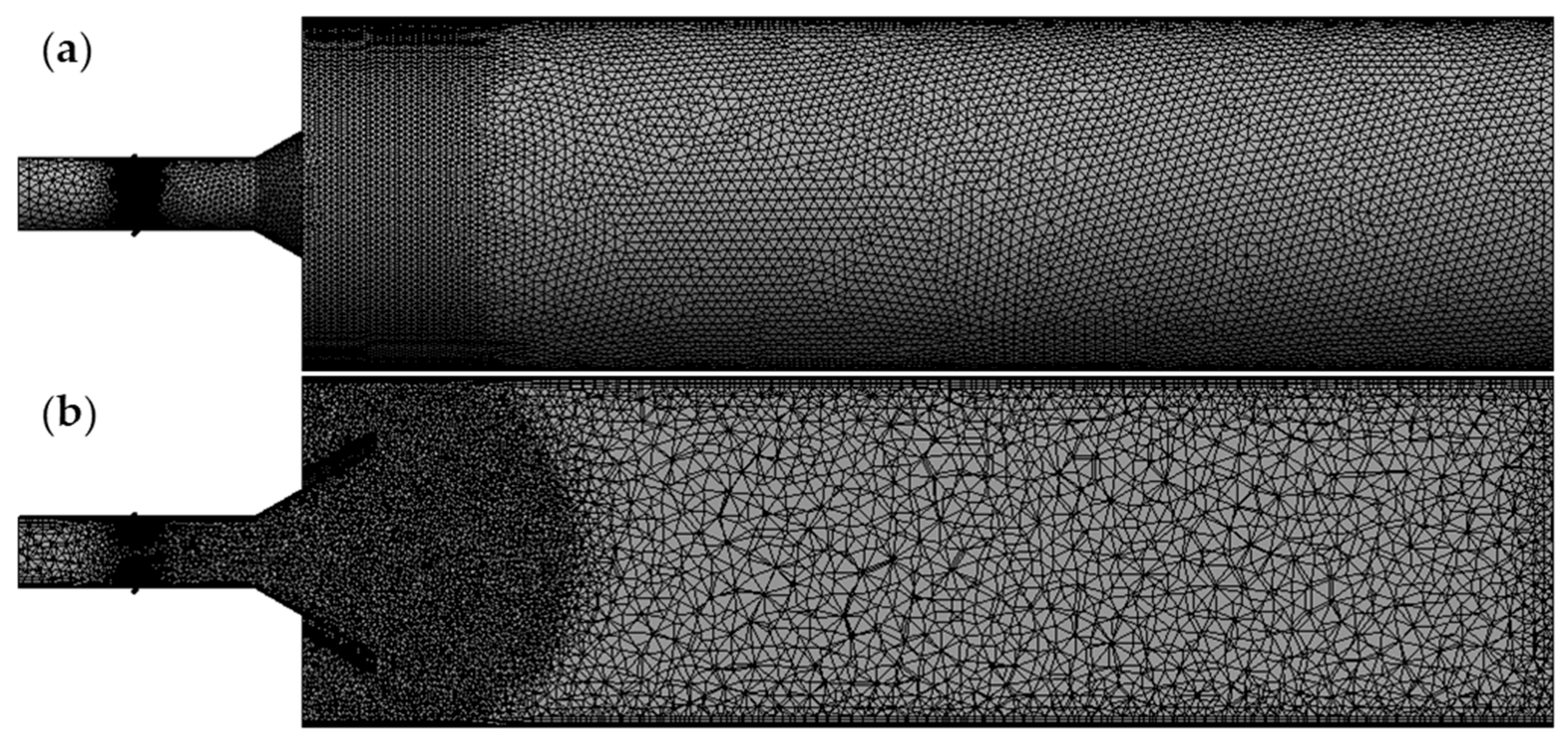

3.2. Introduction of the Combustion Equipment Grid Partitioning and Grid Independence Verification

3.3. Boundary Condition Setting

4. Results and Discussions

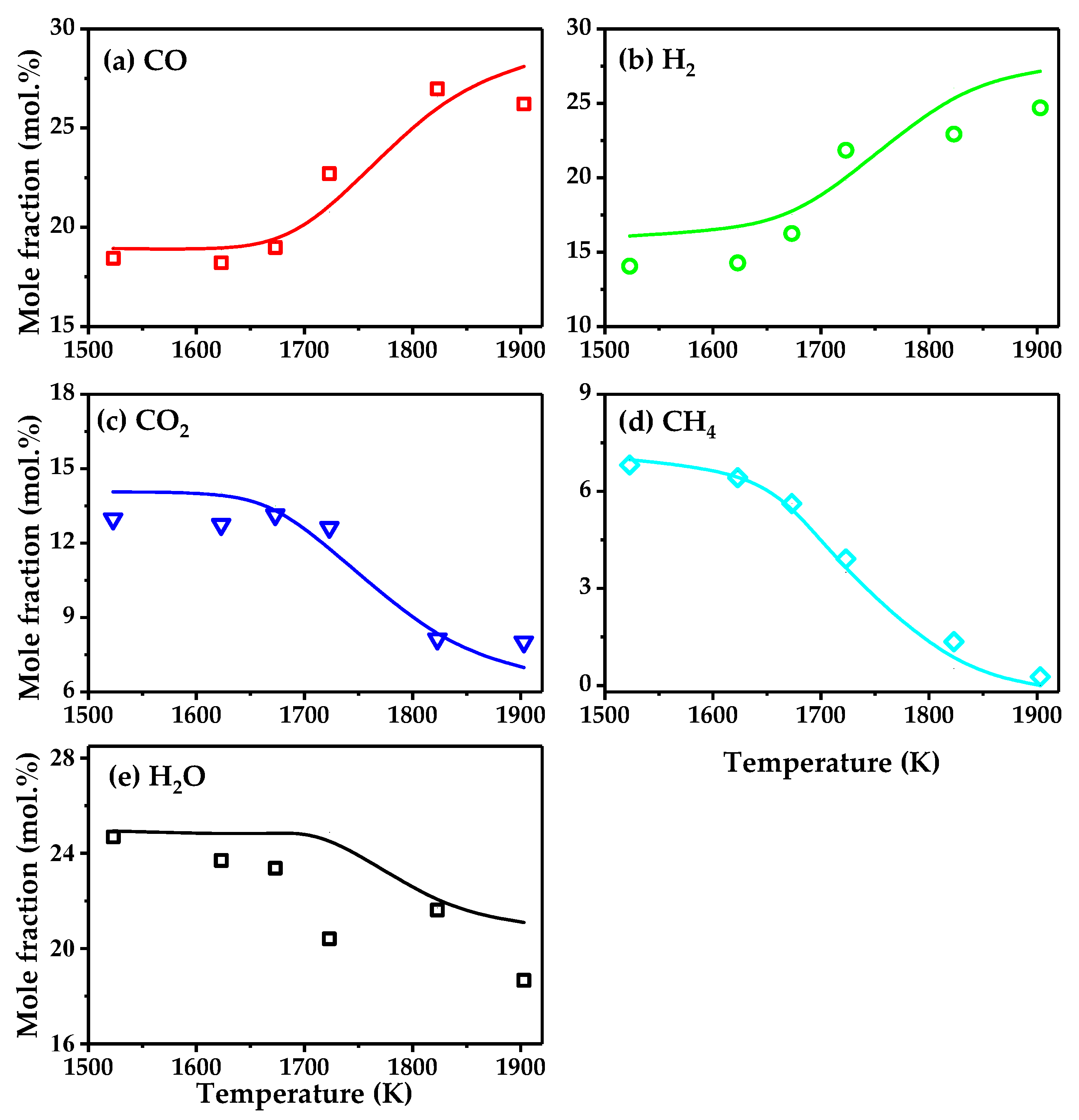

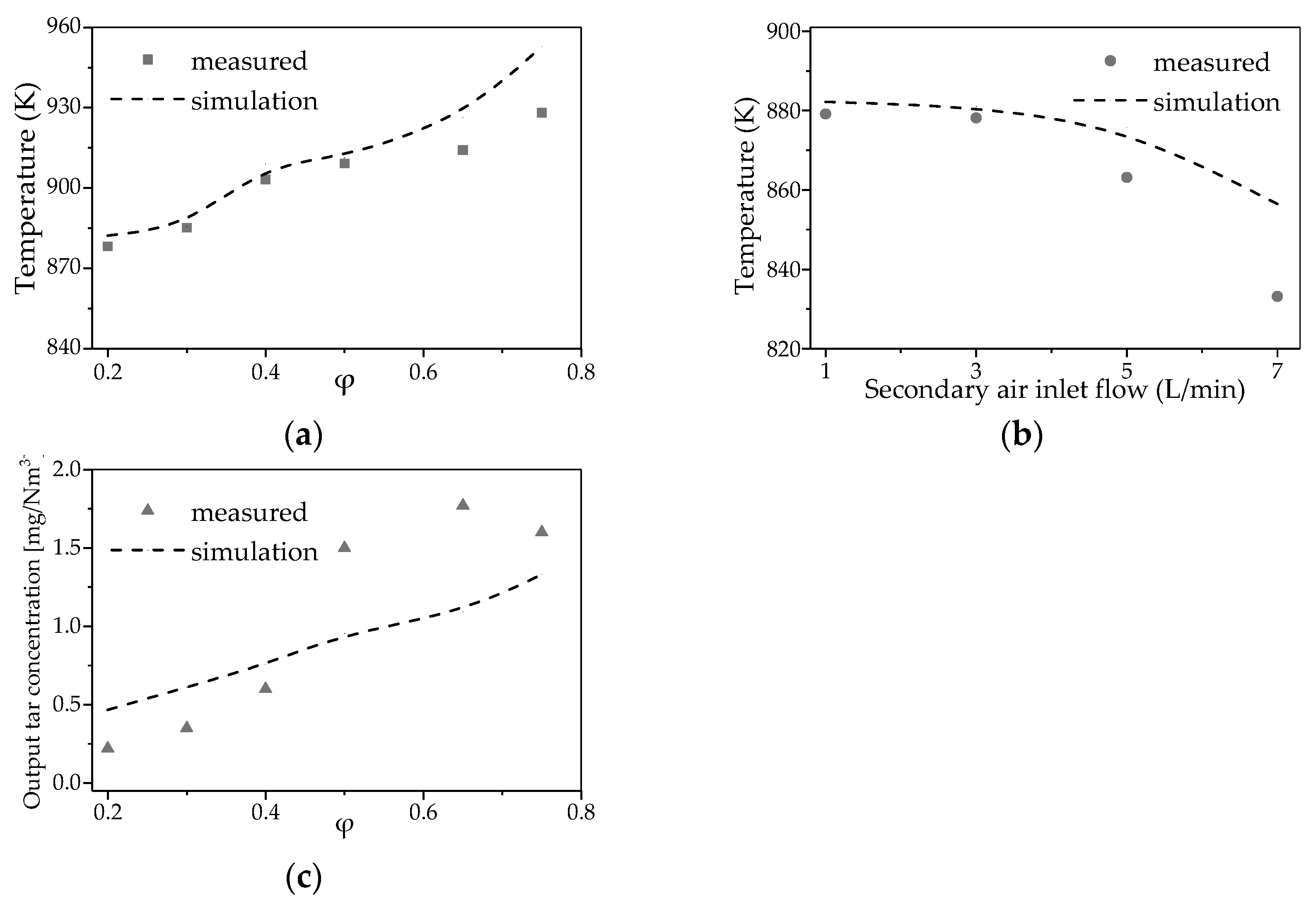

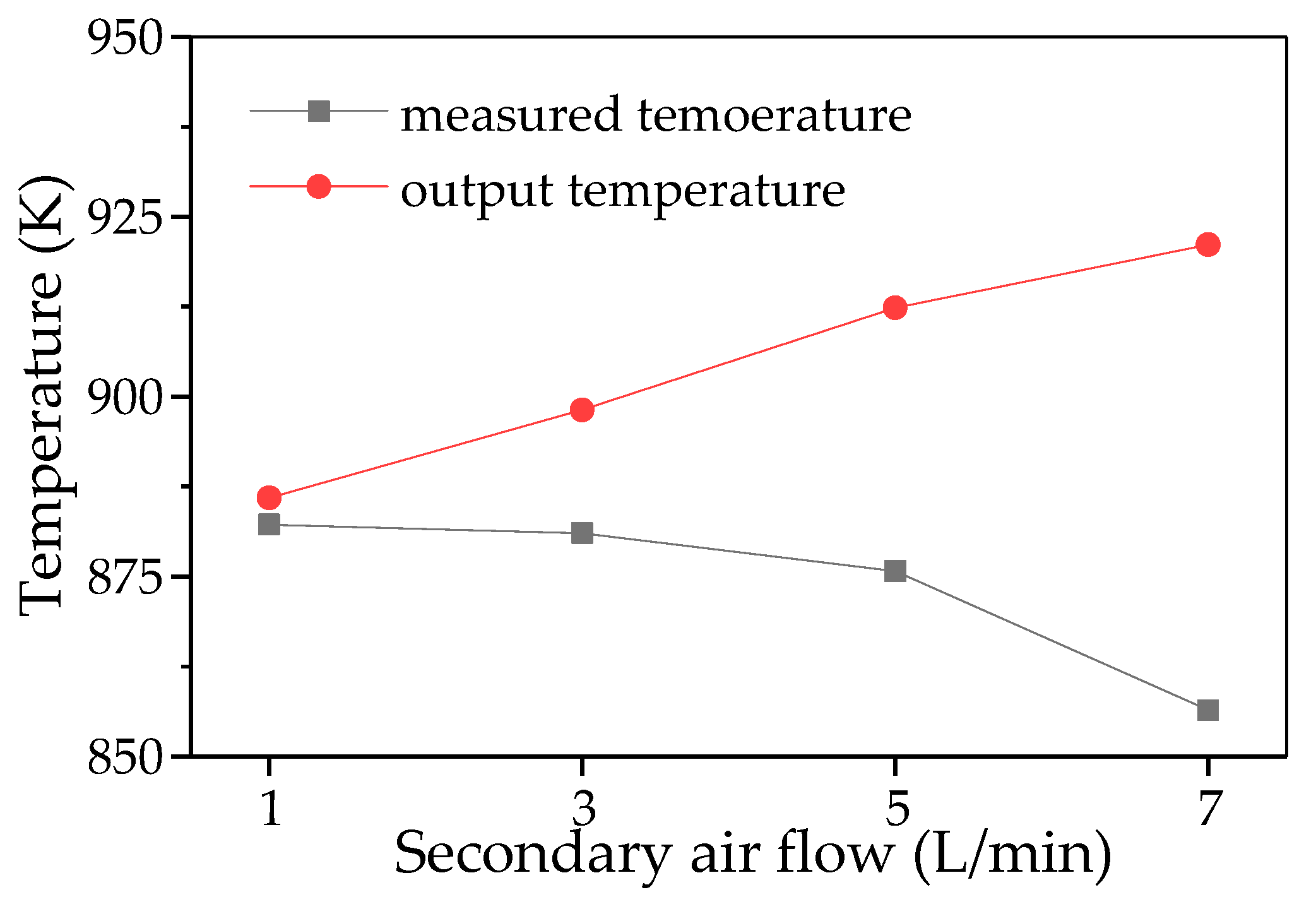

4.1. Model Validation

4.2. Influence of Air Inlet on Temperature Distribution and Tar Reduction in a Partial Oxidation Reactor

4.2.1. Influence of Primary Air Inlet on the Temperature Field Within the Reactor

4.2.2. Influence of Primary Air Inlet on the Chemical Reaction Dynamics Within in the Reactor

4.3. Influence of Secondary Air Inlet on Temperature Distribution and Tar Reduction in a Partial Oxidation Reactor

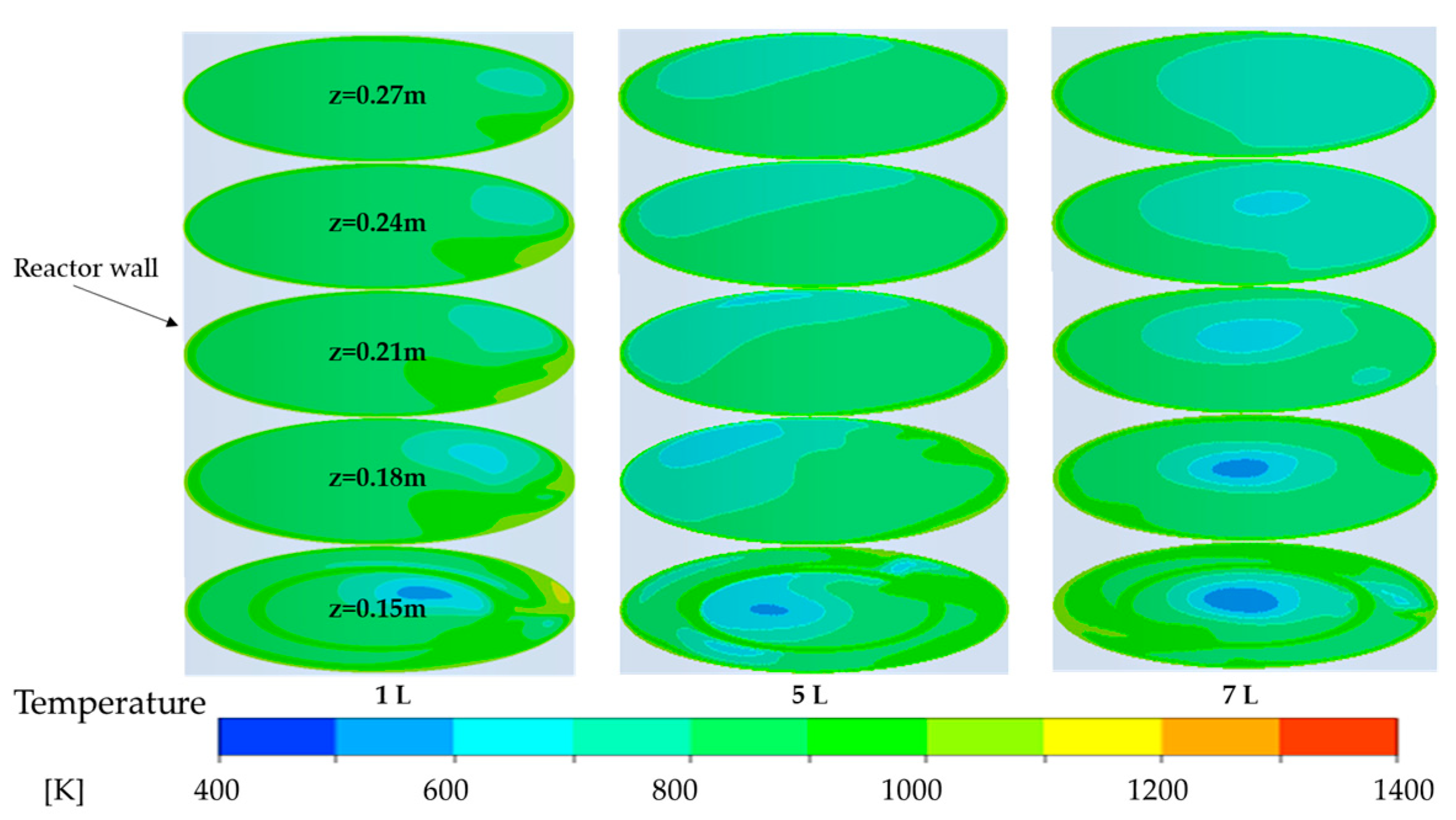

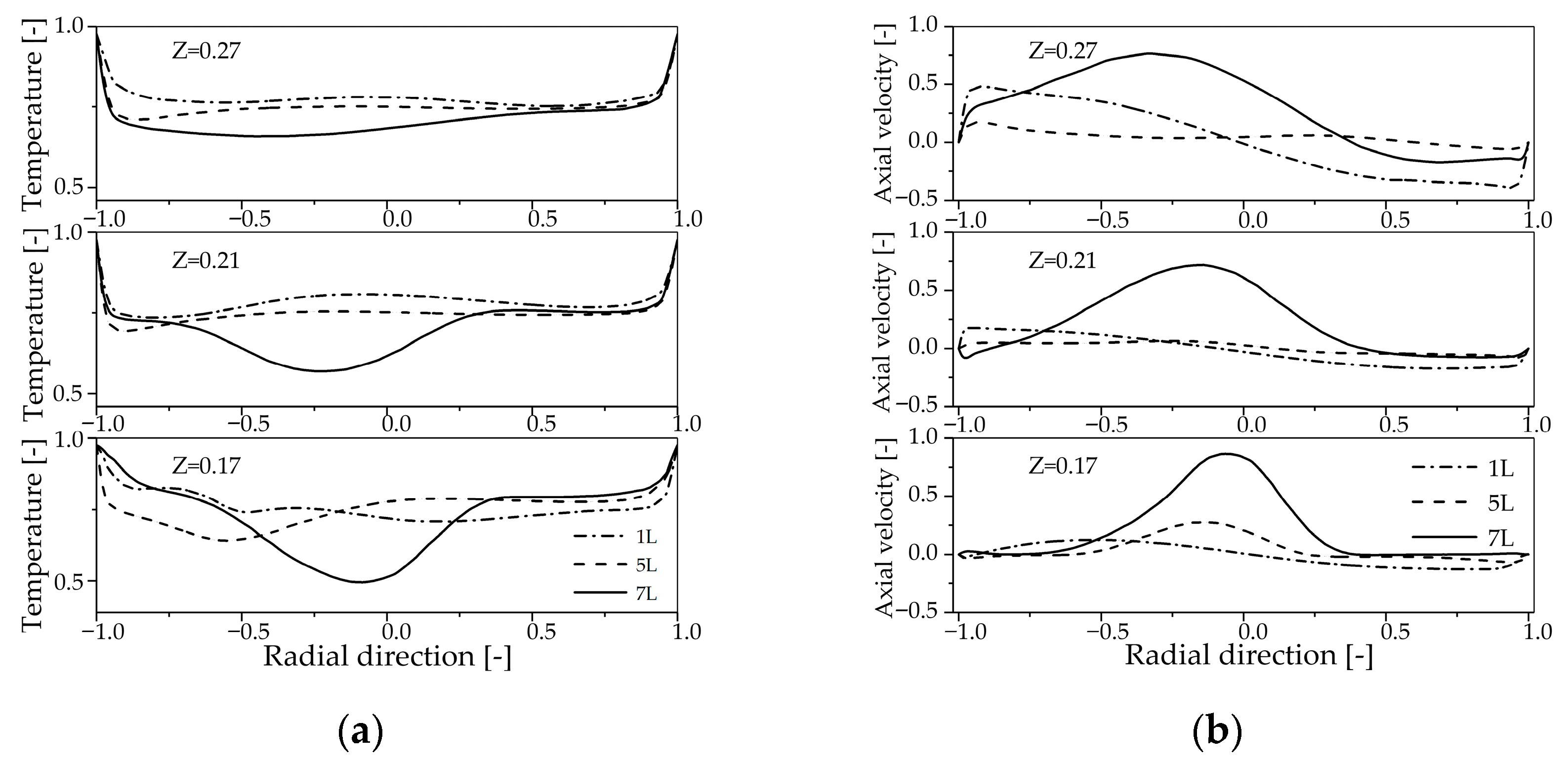

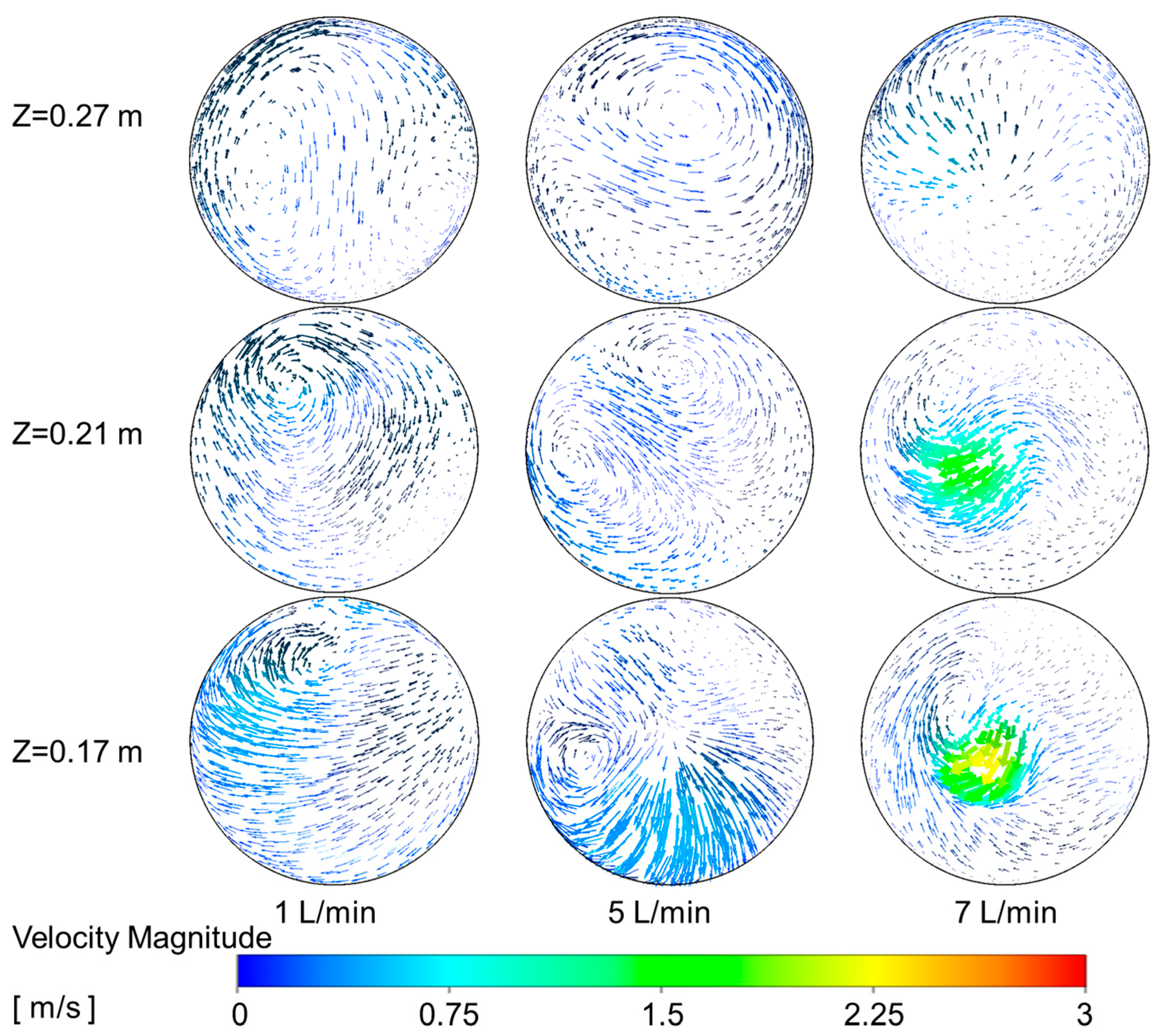

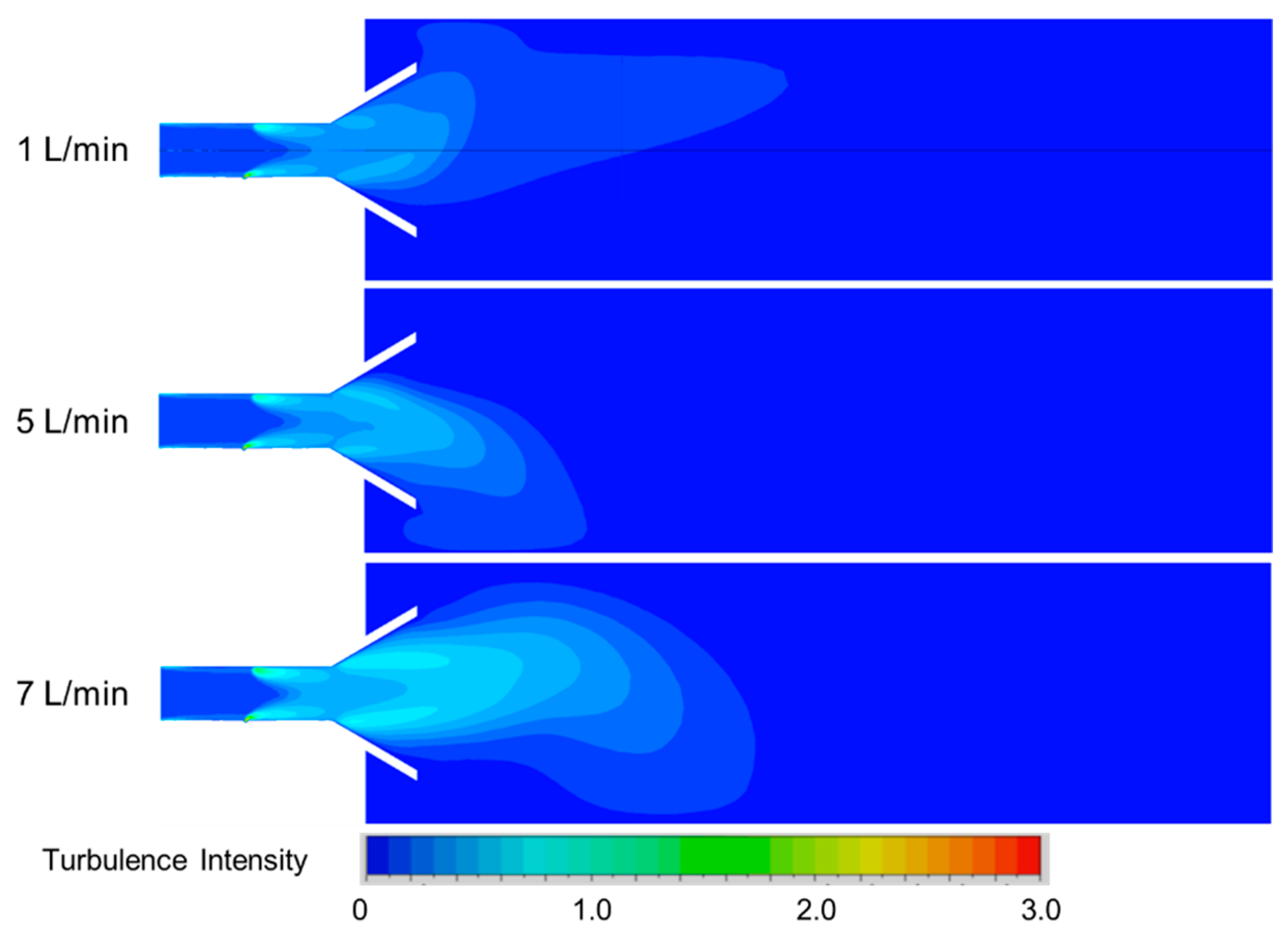

4.3.1. Subsubsection Influence of Secondary Air Inlet on the Temperature Field Within the Reactor

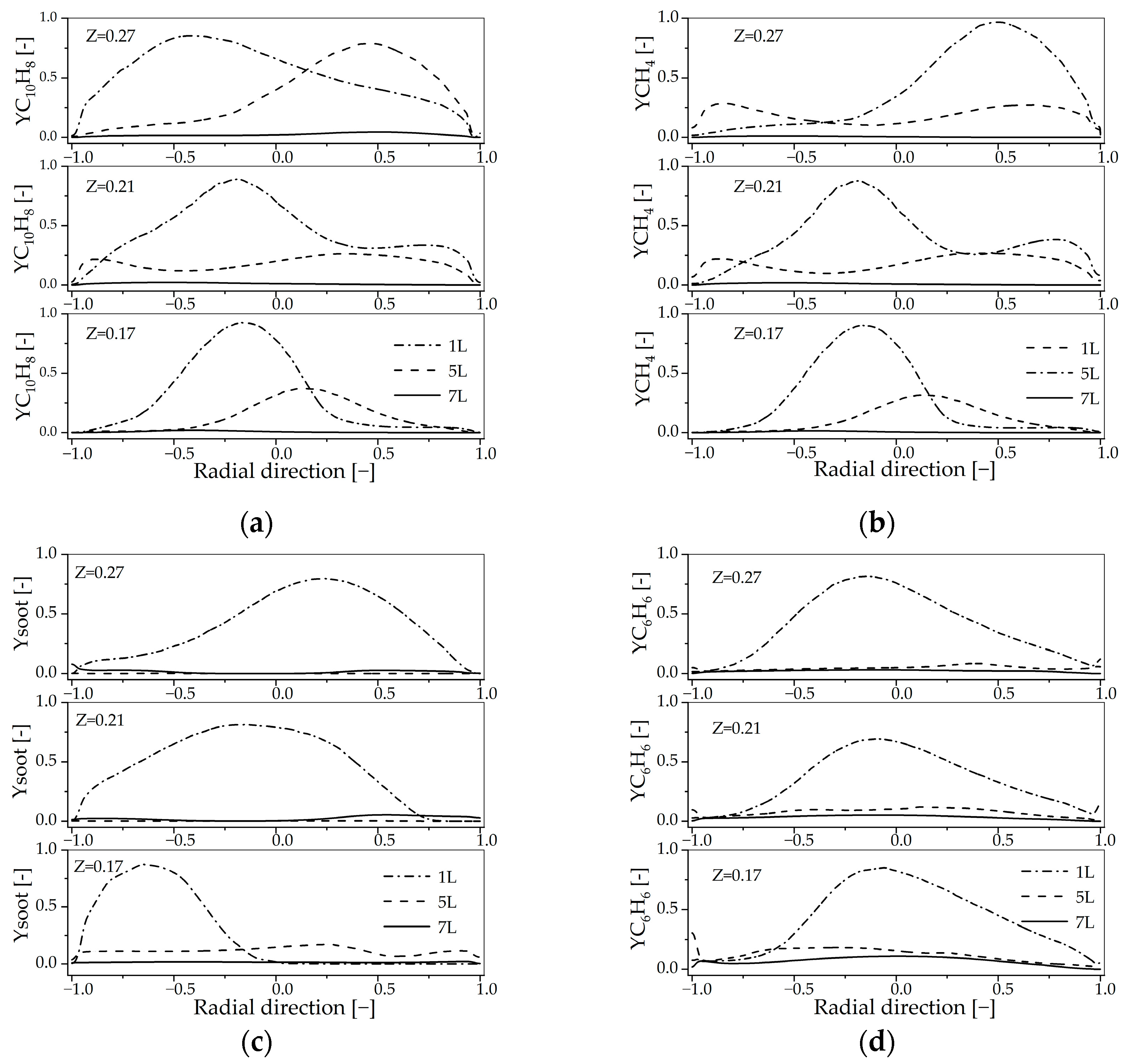

4.3.2. Influence of Secondary Air Inlet on the Chemical Reaction Dynamics Within the Reactor

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nikolina, S. International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA). 2024. Available online: https://www.irena.org/Energy-Transition/Outlook (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Sher, F.; Hameed, S.; Omerbegović, N.S.; Chupin, A.; Hai, I.U.; Wang, B.; Teoh, Y.H.; Yildiz, M.J. Cutting-edge biomass gasification technologies for renewable energy generation and achieving net zero emissions. Energy Convers. Manag. 2025, 323, 119213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reina-Guzmán, S.; Ayabaca-Sarria, C.; Tipanluisa-Sarchi, L.; Venegas-Vásconez, D. Thermochemical Conversion of Biomass: Aspen Plus® Modeling of Sugarcane Bagasse Gasification for Syngas Integration. Processes 2025, 13, 3037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.F.; Wang, L.; Sadeq, A.M.; Alsenani, T.R.; Muhammad, T. Biomass gasification combined with a novel heat integration design for sustainable energy supply programs: Comprehensive thermodynamic, environmental, and economic evaluations. Energy 2025, 337, 138560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paramasivam, P.; Alruqi, M.; Ağbulut, Ü. Experimental simulation and analysis of Acacia Nilotica biomass gasification with XGBoost and SHapley Additive Explanations to determine the importance of key features. Energy 2025, 327, 136291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y. Biomass pretreatment for steam gasification toward H2-rich syngas production–An overview. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2024, 66, 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, L.; Guo, S.; Feng, Z.; Shao, H.; He, X.; Wu, A. The effects of conventional and microwave torrefaction on waste distiller’s grains and its steam gasification characteristics. Fuel 2025, 380, 133163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, S.; Tahir, M.H.; Chen, D.; Hong, L.; Feng, Y.; Huang, Z. MSW pyro-gasification using high-temperature CO2 as gasifying agent: Influence of contact mode between CO2, char and volatiles on final products. Waste Manag. 2023, 170, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, F.; Raashid, M.; Rehman, A.; Khoja, A.H.; Abbas, A.; Gul, S. Dielectric barrier discharge reactor application in biomass gasification tar removal. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 208, 114963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díez, D.; Urueña, A.; Antolín, G. Investigation of Ni–Fe–Cu-Layered Double Hydroxide Catalysts in Steam Reforming of Toluene as a Model Compound of Biomass Tar. Processes 2021, 9, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.; Zhang, T.; Wang, Y.; Labidi, A.; Leus, K.; De Geyter, N. Plasma-catalytic reforming of toluene over Ni/HZSM-5 catalysts: Synergistic effect and reaction mechanism. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 520, 166113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talero, G.; Kansha, Y. Atom economy or product yield to determine optimal gasification conditions in biomass-to-olefins biorefinery. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2023, 199, 689–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liang, W.; Cao, G.; Li, C.; Zhao, J.; Fang, Y. Kinetic Analysis of Biomass Gasification Coupled with Non-Catalytic Reforming to Syngas Production. J. Fuel Chem. Technol. 2023, 51, 921–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Errekatxo, A.; Ibarra, A.; Gutierrez, A.; Bilbao, J.; Arandes, J.M.; Castaño, P. Catalytic deactivation pathways during the cracking of glycerol and glycerol/VGO blends under FCC unit conditions. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 307, 955–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anis, S.; Zainal, Z.A. Tar reduction in biomass producer gas via mechanical, catalytic and thermal methods: A review. Renew. Sust. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 2355–2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Du, J.; Luo, Z.; He, D.; Ma, W.; Zhou, X.; Liang, S.; Yuan, L. Kinetic study on biomass gasification coupled with tar reforming for syngas production. Biomass Conv. Bioref. 2023, 14, 28377–28385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Luo, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wu, W.; Zhang, Y. Experimental and numerical investigation of tar destruction under partial oxidation environment. Fuel Process. Technol. 2011, 92, 1513–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demol, R.; Ruiz, M.; Schnitzer, A.; Herbinet, O.; Mauviel, G. Experimental and modeling investigation of partial oxidation of gasification tars. Fuel 2023, 351, 128990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoeven, T. Partial Product Gas Combustion for Tar Reduction. Ph.D. Thesis, Eindhoven University of Technology, Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, W.G.; Luo, Y.H.; Chen, Y.; Su, Y.; Zhang, Y.L.; Zhao, S.H.; Wang, Y. Experimental investigation of tar conversion under inert and partial oxidation conditions in a continuous reactor. Energy Fuel 2011, 25, 2721–2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houben, M.; De Lange, H.; Van Steenhoven, A. Tar reduction through partial combustion of fuel gas. Fuel 2005, 84, 817–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jess, A. Mechanisms and kinetics of thermal reactions of aromatic hydrocarbons from pyrolysis of solid fuels. Fuel 1996, 75, 1441–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, H.; Tunå, P.; Hulteberg, C.; Brandin, J. Modeling of soot formation during partial oxidation of producer gas. Fuel 2013, 106, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongchang, T.; Patumsawad, S.; Fungtammasan, B. An analysis of wood pyrolysis tar from high temperature thermal cracking process. Energy Sources Part A Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. 2013, 35, 926–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhao, S.; Luo, Y. Experimental and modeling investigation on the effect of intrinsic and extrinsic oxygen on biomass tar decomposition. Energy Fuels 2017, 31, 8665–8673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houben, M.P. Analysis of Tar Removal in a Partial Oxidation Burner. Ph.D. Thesis, Eindhoven University of Technology, Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, F.A. Combustion Theory; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Putra, B.A.; Ertesvåg, I.S. Eddy Dissipation Concept (EDC) with Batch Reactor Fine Structures Model for Flames Toward Low Turbulence. Combust. Sci. Technol. 2025, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Du, M.; Xiao, Z.; Zhu, X. Simulation of Soot Formation in Pulverized Coal Combustion under O2/N2 and O2/CO2 Atmospheres. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 22051–22064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freitas, C.J. The issue of numerical uncertainty. Appl. Math. Model. 2002, 26, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manna, P.; Dharavath, M.; Sinha, P.; Chakraborty, D. Optimization of a flight-worthy scramjet combustor through CFD. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2013, 27, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valin, S.; Cances, J.; Castelli, P.; Thiery, S.; Dufour, A.; Boissonnet, G.; Spindler, B. Upgrading biomass pyrolysis gas by conversion of methane at high temperature: Experiments and modelling. Fuel 2009, 88, 834–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseri, A.; Kholghy, M.R.; Juan, N.A.; Thomson, M.J. Simulating yield and morphology of carbonaceous nanoparticles during fuel pyrolysis in laminar flow reactors enabled by reactive inception and aromatic adsorption. Combust. Flame 2022, 237, 111721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Number of Grids (Million) | hi (mm) | r | F(T) (K) | ε | GCI (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.13 | 11.011 | 0.9666 | 733.56 | 0.00018 | 0.34 |

| 2.82 | 10.643 | 1.1310 | 733.69 | 0.00095 | 0.43 |

| 3.31 | 9.736 | 1.2710 | 734.39 | 0.00002 | 0.06 |

| 3.96 | 7.660 | 734.41 |

| Wall Name | Boundary Setting |

|---|---|

| upper reactor wall | T = 773.15 K, ε = 0.6, thermal boundary |

| nozzle wall | T = 973.15 K, ε = 0.6, thermal boundary |

| lower burner wall | T = 473.15 K, ε = 0.6, thermal boundary |

| Items | Parameters | Units |

|---|---|---|

| Fuel inlet flow | 40 | L/min |

| Primary air inlet flow | 8.0022~30.0008 | L/min |

| Secondary air inlet flow | 1~7 | L/min |

| Tar inlet temperature | 473.15 | K |

| Nozzle inlet temperature | 473.15 | K |

| Reactor inlet temperature | 473.15 | K |

| Temperature of reactor wall | 473.15 | K |

| Turbulence model | Realizable k-ε model |

| Composition | CH4 (%) | H2 (%) | N2 (%) | C10H8 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content | 2 | 32 | 65.995 | 0.005 |

| O2 Injection Methods | Tmax (K) | ηtar (%) | Ysoot (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary air input | 1398.63 | 99.13 | 0.0504 |

| Secondary air input | 1279.17 | 99.98 | 0.0460 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Cao, G.; Wang, S.; Hu, D.; Ba, Z.; Li, C.; Zhao, J.; Fang, Y. Modeling of Tar Removal in a Partial Oxidation Burner: Effect of Air Injection on Temperature, Tar Conversion, and Soot Formation. Processes 2025, 13, 3903. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123903

Wang Y, Cao G, Wang S, Hu D, Ba Z, Li C, Zhao J, Fang Y. Modeling of Tar Removal in a Partial Oxidation Burner: Effect of Air Injection on Temperature, Tar Conversion, and Soot Formation. Processes. 2025; 13(12):3903. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123903

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yongbin, Guoqiang Cao, Sen Wang, Donghai Hu, Zhongren Ba, Chunyu Li, Jiantao Zhao, and Yitian Fang. 2025. "Modeling of Tar Removal in a Partial Oxidation Burner: Effect of Air Injection on Temperature, Tar Conversion, and Soot Formation" Processes 13, no. 12: 3903. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123903

APA StyleWang, Y., Cao, G., Wang, S., Hu, D., Ba, Z., Li, C., Zhao, J., & Fang, Y. (2025). Modeling of Tar Removal in a Partial Oxidation Burner: Effect of Air Injection on Temperature, Tar Conversion, and Soot Formation. Processes, 13(12), 3903. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123903