Dried Sourdough as a Functional Tool for Enhancing Carob-Enriched Wheat Bread

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ingredients

2.2. Fundamental Rheological Measurements

2.3. Bread Sample Preparation

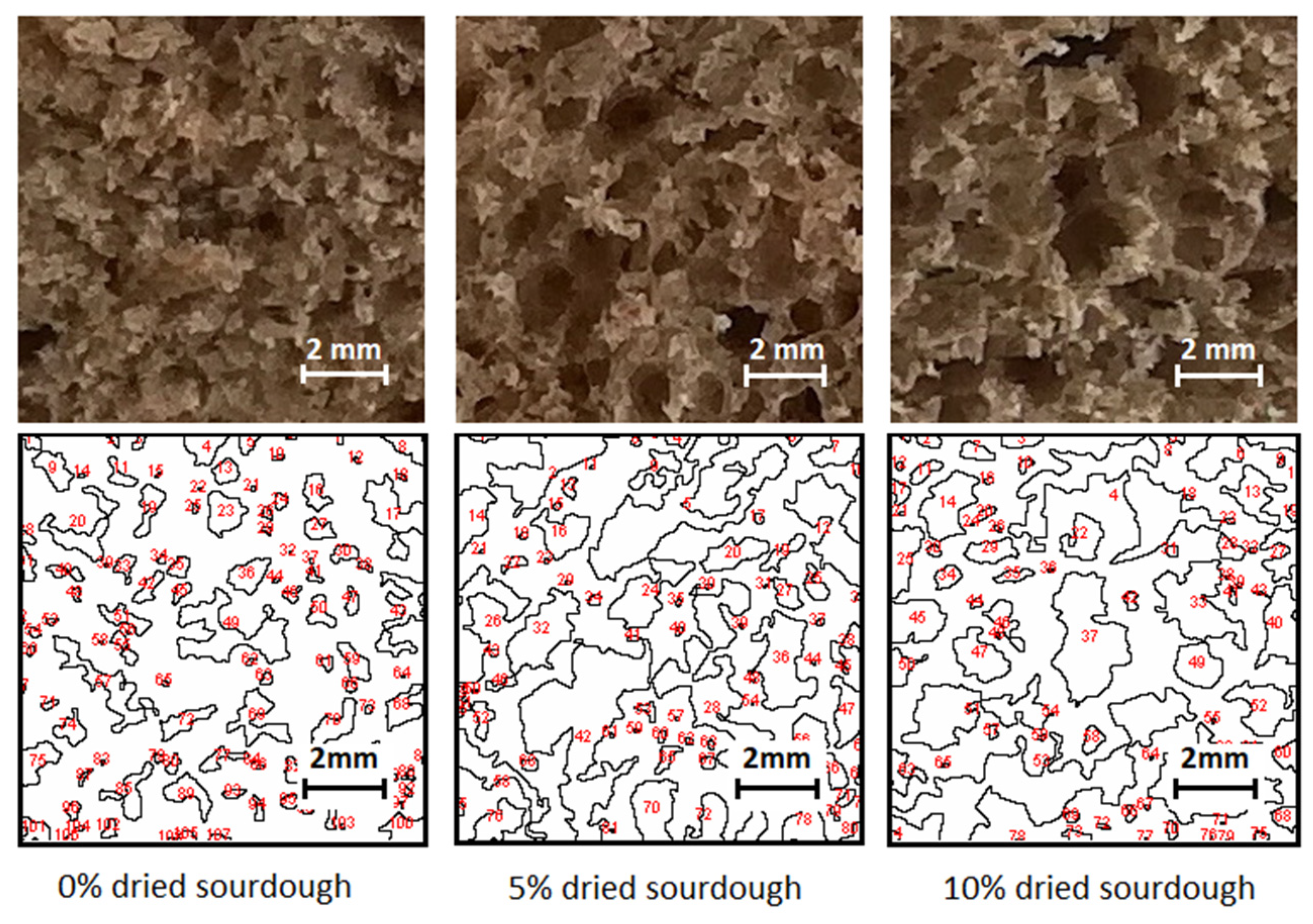

2.4. Crumb Pore Structure

2.5. Textural Properties

2.6. Crumb Sensory Quality

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

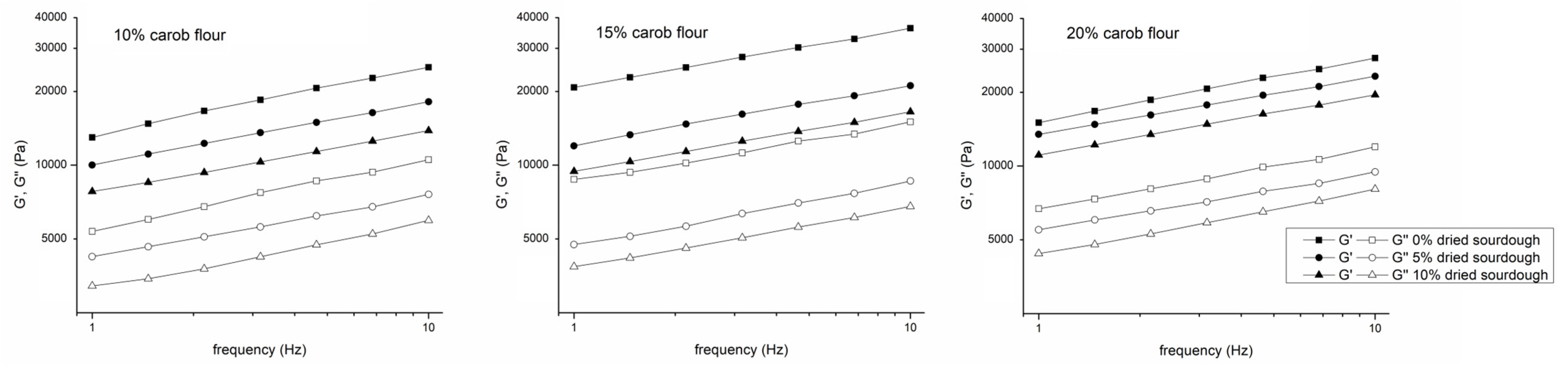

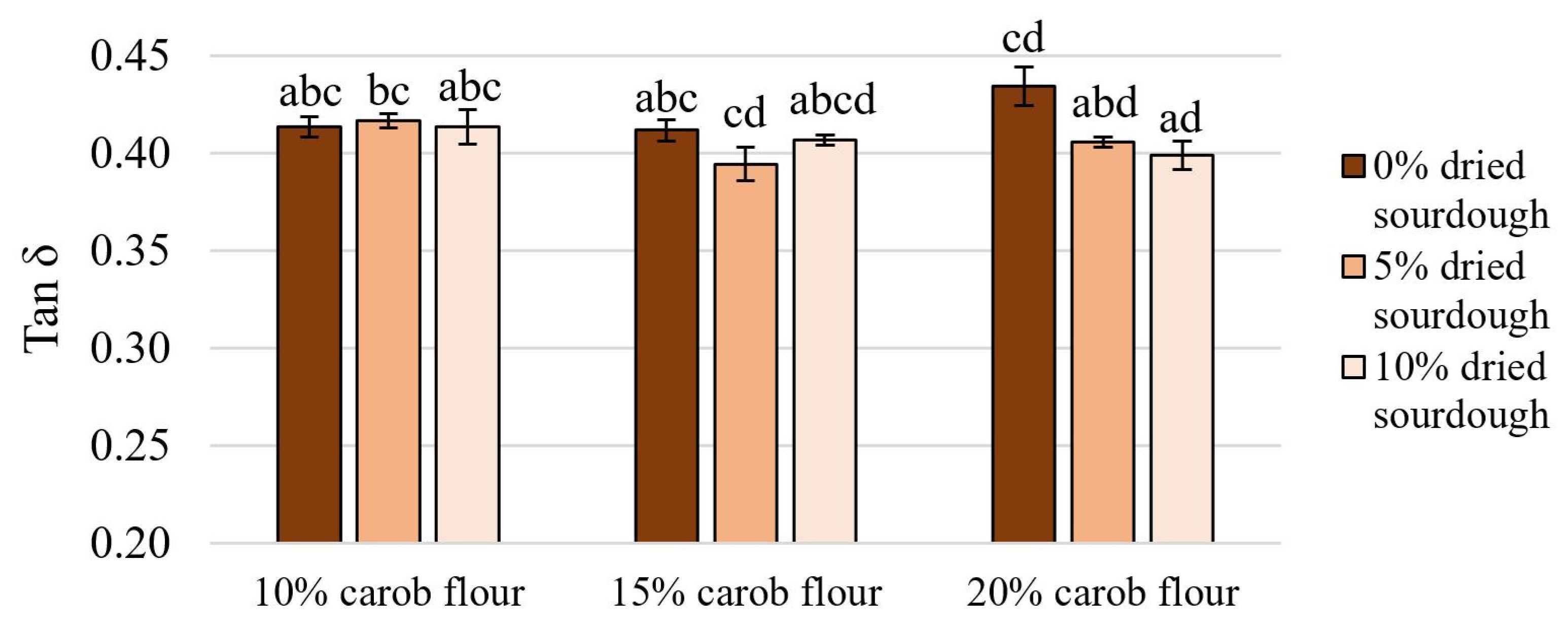

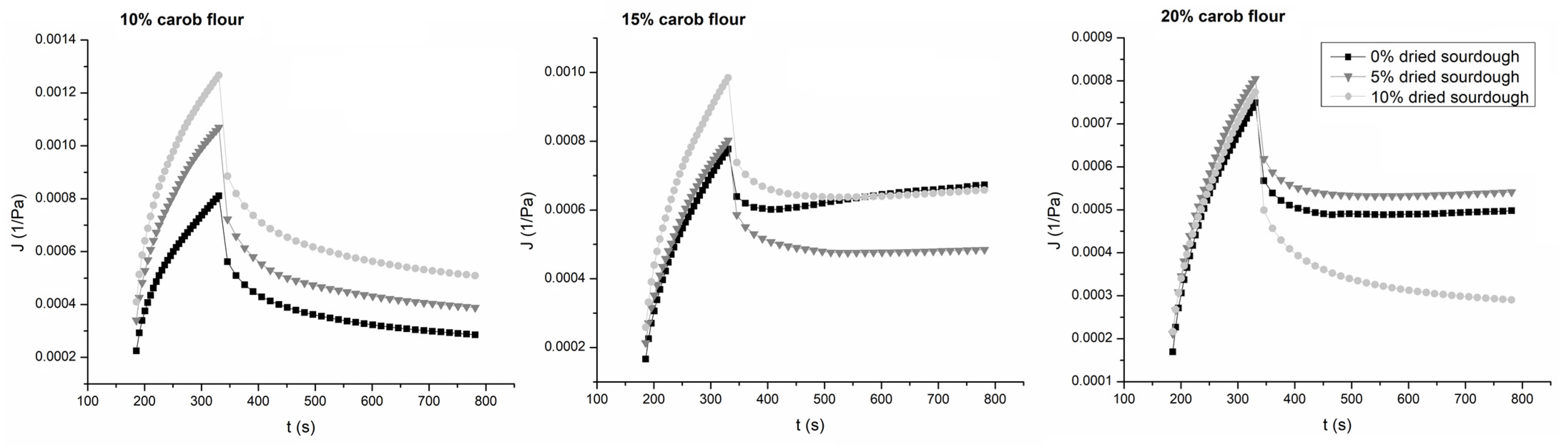

3.1. Rheological Parameters

3.2. Bread Quality Parameters

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

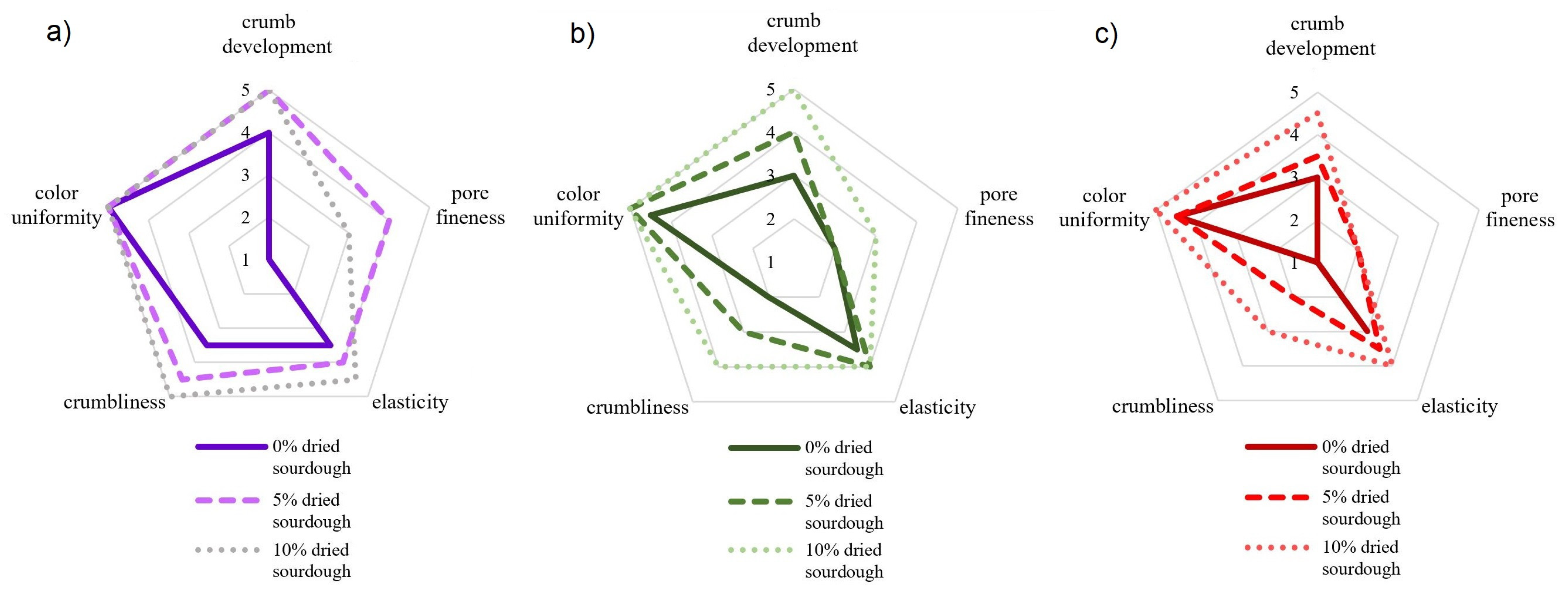

Appendix A

| Attribute | Descriptive Scores | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Crumb development | very dense crumb | rather dense crumb | slightly dense crumb | moderately developed crumb | well-developed crumb |

| Pore fineness | coarse pores | slightly coarse pores | nearly fine pores | fine pores | spongy pores |

| Elasticity | unsatisfactory elasticity | satisfactory elasticity | good elasticity | very good elasticity | excellent elasticity |

| Crumbliness | extremely crumbly | rather crumbly | partly crumbly | slightly crumbly | not crumbly |

| Color uniformity | non-uniform color | rather non-uniform color | partly uniform color | fairly uniform color | uniform color |

References

- Qi, W.; Shen, H.; Jiao, Y.; Li, T.; Rivadeneira, J.; Shu, Y.; Zhao, K.; Wu, F.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Z. Donkey myofibrillar protein/sodium alginate-stabilized high internal phase Pickering emulsion as fat substitutes in emulsion-type sausages: Physicochemical, sensory properties and freeze-thaw stability. Food Res. Int. 2025, 221, 117284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, T.; Gong, J.; Lin, J.; Palanisamy, C.P.; Pei, J. Machine learning-driven multimodal optimization of selenium biotransformation and flavor profiling in fermented apple–Yacon functional beverages. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2025, 105, 104198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wang, K.; Lin, S.; Zhang, Z.; Cheng, M.; Hu, S.; Hu, H.; Xiang, J.; Chen, F.; Li, G.; et al. Comparison of the effects between tannins extracted from different natural plants on growth performance, antioxidant capacity, immunity, and intestinal flora of broiler chickens. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins-Loução, M.A.; Correia, P.J.; Romano, A. Carob: A Mediterranean Resource for the Future. Plants 2024, 13, 1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brassesco, M.E.; Brandão, T.R.S.; Silva, C.L.M.; Pintado, M. Carob Bean (Ceratonia siliqua L.): A New Perspective for Functional Food. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 114, 310–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, G.D.; Savva, I.K.; Christou, A.; Stavrou, I.J.; Kapnissi-Christodoulou, C.P. Phenolic profile, antioxidant activity, and chemometric classification of carob pulp and products. Molecules 2023, 28, 2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas, M.V.; Carbas, B.; Brites, C.; Puppo, M.C. Influence of Different Carob Fruit Flours (Ceratonia siliqua L.) on Wheat Dough Performance and Bread Quality. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2015, 8, 1561–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šoronja-Simović, D.; Zahorec, J.; Šereš, Z.; Griz, A.; Sterniša, M.; Smole Možina, S. The Food Industry By-Products in Bread Making: Single and Combined Effect of Carob Pod Flour, Sugar Beet Fibers and Molasses on Dough Rheology, Quality and Food Safety. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 59, 1429–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issaoui, M.; Flamini, G.; Delgado, A. Sustainability Opportunities for Mediterranean Food Products through New Formulations Based on Carob Flour (Ceratonia siliqua L.). Sustainability 2021, 13, 8026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mordor Intelligence Research & Advisory. Sourdough Market Size & Share Analysis—Growth Trends & Forecasts (2025–2030). Available online: https://www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/sourdough-market (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Alkay, Z.; Falah, F.; Cankurt, H.; Dertli, E. Exploring the Nutritional Impact of Sourdough Fermentation: Its Mechanisms and Functional Potential. Foods 2024, 13, 1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dapčević-Hadnađev, T.; Tomić, J.; Škrobot, D.; Šarić, B.; Hadnađev, M. Processing strategies to improve the breadmaking potential of whole-grain wheat and non-wheat flours. Discov. Food 2022, 2, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pontonio, E.; Verni, M.; Montemurro, M.; Rizzello, C.G. Sourdough: A Tool for Non-Conventional Fermentations and to Recover Side Streams. In Handbook on Sourdough Biotechnology; Gobbetti, M., Gänzle, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 257–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspri, M.; Čukelj Mustač, N.; Tsaltas, D. Non-cereal and Legume Based Sourdough Metabolites. In Sourdough Innovations: Novel Uses of Metabolites, Enzymes, and Microbiota from Sourdough Processing, 1st ed.; Garcia-Vaquero, M., Rocha, J.M.F., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2023; pp. 63–86. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, Z.E.; Pinho, O.; Ferreira, I.M.P.L.V.O. Food Industry By-Products Used as Functional Ingredients of Bakery Products. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 63, 106–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanmartín, G.; Prieto, J.A.; Morard, M.; Estruch, F.; Blasco-García, J.; Randez-Gil, F. The Effects of Sourdough Fermentation on the Biochemical Properties, Aroma Profile and Leavening Capacity of Carob Flour. Foods 2025, 14, 1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novotni, D.; Mutak, N.; Nanjara, L.; Drakula, S.; Čukelj Mustač, N.; Voučko, B.; Ćurić, D. Sourdough Fermentation of Carob Flour and Its Application in Wheat Bread. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2020, 58, 465–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlıdağ, S.; Arıcı, M.; Özülkü, G. Carob Flour Addition to Sourdough: Effect of Sourdough Fermentation, Dough Rheology and Bread Quality. J. Tekirdag Agric. Fac. 2022, 19, 541–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voučko, B.; Vuković, S.; Kovačević, D.; Jovanović, M.; Đorđević, V.; Jovanović, J.; Ristić, M.; Mitić, S.; Jovanović, J.; Mitić, M.; et al. Fermentation Performance of Carob Flour, Proso Millet Flour and Bran for Gluten-Free Flat-Bread. Foods 2024, 13, 3458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-Figueroa, R.H.; Mani-López, E.; Palou, E.; López-Malo, A. Sourdoughs as Natural Enhancers of Bread Quality and Shelf Life: A Review. Fermentation 2024, 10, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albagli, G.; Schwartz, I.M.; Amaral, P.; Ferreira, T. How dried sourdough starter can enable and spread the use of sourdough bread. LWT 2021, 149, 111888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pétel, C.; Onno, B.; Prost, C. Sourdough volatile compounds and their contribution to bread: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 59, 105–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahorec, J.; Šoronja-Simović, D.; Petrović, J.; Šereš, Z.; Pavlić, B.; Božović, D.; Perović, L.; Martić, N.; Bulut, S.; Kocić-Tanackov, S. Development of Functional Bread: Exploring the Nutritional, Bioactive and Microbial Potential of Carob (Ceratonia siliqua L.) Pulp Powder. Processes 2024, 12, 2882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selaković, A.; Nikolić, I.; Dokić, L.; Šoronja-Simović, D.; Šimurina, O.; Zahorec, J.; Šereš, Z. Enhancing Rheological Performance of Laminated Dough with Whole Wheat Flour by Vital Gluten Addition. LWT–Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 138, 110604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verni, M.; Rizzello, C.G. Image Analysis. In Basic Methods and Protocols on Sourdough. Methods and Protocols in Food Science; Gobbetti, M., Rizzello, C.G., Eds.; Humana: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 111–118. [Google Scholar]

- Mastilović, J.; Torbica, A.; Kevrešan, Ž.; Pojić, M.; Živančev, D.; Hadnađev, M.; Dapčević Hadnađev, T.; Janić Hajnal, E.; Tomić, J.; Rakita, S.; et al. Standardizovani Postupak Probnog Pečenja i Instrumentalne Ocene Parametara Pecivosti; Tehničko Rešenje; Naučni Institut za Prehrambene Tehnologije u Novom Sadu: Novi Sad, Serbia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- American Association of Cereal Chemists. Approved Methods of the AACC; Method 74-09; The Association: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 13299:2016; Sensory Analysis—Methodology—General Guidance for Establishing a Sensory Profile. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- Sipos, L.; Nyitrai, Á.; Hitka, G.; Friedrich, L.F.; Kókai, Z. Sensory Panel Performance Evaluation—Comprehensive Review of Practical Approaches. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 11977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, H.; Sidel, J.L. Sensory Evaluation Practices; Academic Press: Redwood City, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S.; Singh, N. Relationship of polymeric proteins and empirical dough rheology with dynamic rheology of dough and gluten from different wheat varieties. Food Hydrocoll. 2013, 33, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortolan, F.; Corrêa, G.P.; da Cunha, R.L.; Steel, C.J. Rheological properties of vital wheat glutens with water or sodium chloride. LWT 2017, 79, 647–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroy, V.; Pitura, K.M.; Scanlon, M.G.; Page, J.H. The complex shear modulus of dough over a wide frequency range. J. Non-Newton. Fluid Mech. 2010, 165, 475–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alioğlu, T.; Özülkü, G. Evaluation of whole wheat flour sourdough as a promising ingredient in short dough biscuits. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 41, 1009–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, W.; Ma, G.; Ma, N.; Hu, Q.; Pei, F. A novel lactic acid bacterium for improving the quality and shelf life of whole wheat bread. Food Control 2020, 109, 106914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miś, A.; Dziki, D. Extensograph curve profile model used for characterising the impact of dietary fibre on wheat dough. J. Cereal Sci. 2013, 57, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarabhai, S.; Sudha, M.L.; Prabhasankar, P. Rheological characterization and biscuit making potential of gluten free flours. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2017, 11, 1449–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Horra, A.E.; Steffolani, E.M.; Barrera, G.N.; Ribotta, P.D.; León, A.E. The Role of Cyclodextrinase and Glucose Oxidase in Obtaining Gluten-Free Laminated Baked Products. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2018, 244, 1341–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mironeasa, S.; Codină, G.G. Dough Rheological Behavior and Microstructure Characterization of Composite Dough with Wheat and Tomato Seed Flours. Foods 2019, 8, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnand-Ducasse, M.; Della Valle, G.; Lefebvre, J.; Saulnier, L. Effect of wheat dietary fibres on bread dough development and rheological properties. J. Cereal Sci. 2010, 52, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghannam, M.T.; Esmail, M.N. Rheological Properties of Carboxymethyl Cellulose. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1997, 64, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Wang, Z.; Guo, X.; Wang, F.; Huang, J.; Sun, B.; Wang, X. Sourdough improves the quality of whole-wheat flour products: Mechanisms and challenges—A review. Food Chem. 2021, 360, 130038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graça, C.; Lima, A.; Raymundo, A.; Sousa, I. Sourdough Fermentation as a Tool to Improve the Nutritional and Health-Promoting Properties of Its Derived-Products. Fermentation 2021, 7, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutter, J.; Saiz, A.I.; Iurlina, M.O. Microstructural and conformational changes of gluten proteins in wheat-rye sourdough. J. Cereal Sci. 2019, 87, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angioloni, A.; Collar, C. Bread Crumb Quality Assessment: A Plural Physical Approach. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2009, 229, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angioloni, A.; Collar, C. Physicochemical and Nutritional Properties of Reduced-Caloric Density High-Fibre Breads. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 44, 747–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naji-Tabasi, S.; Shahidi-Noghabi, M.; Hosseininezhad, M. Improving the quality of traditional Iranian bread by using sourdough and optimizing the fermentation conditions. SN Appl. Sci. 2022, 4, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, M.; Ronda, F.; Blanco, C.A.; Caballero, P.A.; Apesteguía, A. Effect of Dietary Fibre on Dough Rheology and Bread Quality. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2003, 216, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skendi, A.; Biliaderis, C.G.; Papageorgiou, M.; Izydorczyk, M.S. Effects of Two Barley β-Glucan Isolates on Wheat Flour Dough and Bread Properties. Food Chem. 2010, 119, 1159–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gueven, A.; Hicsasmaz, Z. Pore Structure in Food: Simulation, Measurement and Applications; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ozgolet, M.; Kasapoglu, M.Z.; Avcı, E.; Karasu, S. Enhancing Gluten-Free Muffins with Milk Thistle Seed Proteins: Evaluation of Physicochemical, Rheological, Textural, and Sensory Characteristics. Foods 2024, 13, 2542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simić, M.Z.; Šimurina, O.D.; Nježić, Z.B.; Vančetović, J.P.; Kandić, V.G.; Nikolić, V.V.; Žilić, S.M. Effects of Ascorbic Acid and Sugar on Physical, Textural and Sensory Properties of Composite Breads. Food Feed Res. 2021, 48, 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, K.M.; Coffey, A.; Arendt, E.K. Exopolysaccharide producing lactic acid bacteria: Their techno-functional role and potential application in gluten-free bread products. Food Res. Int. 2018, 110, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Yao, Y.; Li, J.; Ju, X.; Wang, L. Impact of exopolysaccharides-producing lactic acid bacteria on the chemical, rheological properties of buckwheat sourdough and the quality of buckwheat bread. Food Chem. 2023, 425, 136369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakić, N.; Grubačić, M. Uticaj dodatka kiselog tijesta na mrvljivost hljeba od pšeničnog brašna. Agroznanje 2012, 13, 431–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhang, H.; Lyu, L.; Deng, Q.; Fan, H.; Xu, X.; Xu, D. Effects of sourdough on bread staling rate: From the perspective of starch retrogradation and gluten depolymerization. Food Biosci. 2024, 59, 103877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Wheat Flour (g) | Carob Flour (g) | Dried Sourdough (%) 1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 90 | 10 | 0 |

| 2 | 85 | 15 | 0 |

| 3 | 80 | 20 | 0 |

| 4 | 90 | 10 | 5 |

| 5 | 85 | 15 | 5 |

| 6 | 80 | 20 | 5 |

| 7 | 90 | 10 | 10 |

| 8 | 85 | 15 | 10 |

| 9 | 80 | 20 | 10 |

| Independent Variables | G0′ (kPa) | n | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10% carob flour | |||

| 0% dried sourdough | 13.31 ± 0.08 a | 0.279 ± 0.002 f | 0.9989 |

| 5% dried sourdough | 10.06 ± 0.04 d | 0.256 ± 0.001 d | 0.9999 |

| 10% dried sourdough | 7.73 ± 0.11 b | 0.252 ± 0.001 de | 0.9998 |

| 15% carob flour | |||

| 0% dried sourdough | 20.84 ± 0.17 h | 0.240 ± 0.003 bc | 0.9997 |

| 5% dried sourdough | 12.16 ± 0.14 f | 0.241 ± 0.005 bc | 0.9994 |

| 10% dried sourdough | 9.45 ± 0.08 c | 0.243 ± 0.002 bc | 0.9999 |

| 20% carob flour | |||

| 0% dried sourdough | 15.22 ± 0.10 g | 0.259 ± 0.001 d | 0.9994 |

| 5% dried sourdough | 13.49 ± 0.18 a | 0.236 ± 0.002 b | 0.9999 |

| 10% dried sourdough | 11.14 ± 0.05 e | 0.245 ± 0.004 bcd | 0.9998 |

| Power Law Parameters | Factors | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| G0′ | carob flour, C | <0.001 * |

| dried sourdough, S | <0.001 * | |

| C × S | <0.001 * | |

| n | carob flour, C | <0.001 * |

| dried sourdough, S | <0.001 * | |

| C × S | 0.001 * | |

| Tan δ | carob flour, C | 0.097 |

| dried sourdough, S | 0.056 | |

| C × S | 0.146 |

| Independent Variable | Jmax (10−4·Pa−1) | J0 (10−4·Pa−1) | J1 (10−4·Pa−1) | η0 (105·Pas) | λ (s) | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Creep phase | ||||||

| 10% carob flour | ||||||

| 0% dried sourdough | 8.11 ± 0.12 a | 2.25 ± 0.18 ab | 2.68 ± 0.13 ab | 4.08 ± 0.10 a | 143.7 a | 0.9956 |

| 5% dried sourdough | 10.69 ± 0.66 c | 3.40 ± 0.10 a | 3.53 ± 0.11 b | 3.10 ± 0.21 d | 143.8 a | 0.9953 |

| 10% dried sourdough | 12.67 ± 0.37 b | 4.10 ± 0.15 d | 4.18 ± 0.13 c | 2.61 ± 0.12 c | 143.8 a | 0.9933 |

| 15% carob flour | ||||||

| 0% dried sourdough | 7.77 ± 0.40 a | 1.66 ± 0.01 c | 2.56 ± 0.02 ab | 4.26 ± 0.09 ab | 143.8 a | 0.9977 |

| 5% dried sourdough | 8.02 ± 0.06 a | 2.14 ± 0.12 ab | 2.65 ± 0.10 ab | 4.12 ± 0.14 ab | 143.8 a | 0.9979 |

| 10% dried sourdough | 9.84 ± 0.28 b | 2.59 ± 0.02 ab | 3.25 ± 0.01 b | 3.96 ± 0.35 a | 143.8 a | 0.9961 |

| 20% carob flour | ||||||

| 0% dried sourdough | 7.49 ± 0.35 a | 1.69 ± 0.13 c | 2.47 ± 0.11 ab | 4.42 ± 0.15 b | 143.8 a | 0.9968 |

| 5% dried sourdough | 7.74 ± 0.09 a | 2.12 ± 0.01 ab | 2.66 ± 0.02 ab | 4.27 ± 0.21 ab | 143.8 a | 0.9975 |

| 10% dried sourdough | 8.05 ± 0.13 a | 2.17 ± 0.01 ab | 2.55 ± 0.03 ab | 4.11 ± 0.19 ab | 143.8 a | 0.9993 |

| Recovery phase | ||||||

| 10% carob flour | ||||||

| 0% dried sourdough | N/A | 5.62 ± 0.12 ab | 0.94 ± 0.18 b | 2.73 ± 0.13 cd | 339.5 | 0.9560 |

| 5% dried sourdough | N/A | 7.23 ± 0.18 c | 1.28 ± 0.12 d | 2.01 ± 0.03 c | 339.7 | 0.9921 |

| 10% dried sourdough | N/A | 8.85 ± 0.20 d | 1.68 ± 0.10 c | 1.53 ± 0.01 b | 339.7 | 0.9472 |

| 15% carob flour | ||||||

| 0% dried sourdough | N/A | 6.39 ± 0.05 b | 2.22 ± 0.20 e | 1.16 ± 0.01 a | 339.6 | 0.9755 |

| 5% dried sourdough | N/A | 5.86 ± 0.02 ab | 1.60 ± 0.01 c | 1.61 ± 0.00 b | 339.7 | 0.9966 |

| 10% dried sourdough | N/A | 7.38 ± 0.15 c | 2.17 ± 0.10 e | 1.19 ± 0.12 a | 339.7 | 0.9954 |

| 20% carob flour | ||||||

| 0% dried sourdough | N/A | 5.68 ± 0.08 ab | 1.64 ± 0.12 c | 1.57 ± 0.16 b | 339.5 | 0.9884 |

| 5% dried sourdough | N/A | 6.19 ± 0.11 b | 1.79 ± 0.01 c | 1.44 ± 0.20 b | 339.6 | 0.9924 |

| 10% dried sourdough | N/A | 4.99 ± 0.02 a | 0.96 ± 0.10 b | 2.69 ± 0.11 d | 339.7 | 0.9955 |

| Independent Variables | Pore Density (1/cm2) | Average Pore Surface Area (mm2) | Proportion of Pore Surface Area (%) | Proportion of Pore Walls Surface Area (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10% carob flour | ||||

| 0% dried sourdough | 17.0 | 3.02 | 51.35 | 48.65 |

| 5% dried sourdough | 13.0 | 3.86 | 49.88 | 50.12 |

| 10% dried sourdough | 11.8 | 4.15 | 54.59 | 45.41 |

| 15% carob flour | ||||

| 0% dried sourdough | 25.0 | 1.62 | 37.36 | 62.64 |

| 5% dried sourdough | 20.8 | 4.28 | 47.93 | 52.07 |

| 10% dried sourdough | 19.8 | 4.97 | 48.46 | 51.54 |

| 20% carob flour | ||||

| 0% dried sourdough | 27.0 | 0.88 | 23.64 | 76.36 |

| 5% dried sourdough | 12.5 | 2.07 | 43.03 | 56.97 |

| 10% dried sourdough | 10.5 | 2.17 | 42.85 | 57.15 |

| Independent Variables | Hardness (kg) | Springiness | Resilience | Cohesiveness | Chewiness (kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10% carob flour | |||||

| 0% dried sourdough | 0.94 ± 0.29 abc | 0.61 ± 0.09 a | 0.41 ± 0.03 ab | 0.83 ± 0.02 bcd | 0.48 ± 0.19 ab |

| 5% dried sourdough | 0.50 ± 0.06 a | 0.60 ± 0.17 a | 0.43 ± 0.06 ab | 0.81 ± 0.03 abcd | 0.24 ± 0.07 a |

| 10% dried sourdough | 0.77 ± 0.18 ab | 0.60 ± 0.16 a | 0.46 ± 0.07 b | 0.85 ± 0.03 cd | 0.41 ± 0.16 a |

| 15% carob flour | |||||

| 0% dried sourdough | 1.75 ± 0.29 ef | 0.76 ± 0.10 a | 0.36 ± 0.03 ab | 0.75 ± 0.04 ab | 1.00 ± 0.21 c |

| 5% dried sourdough | 1.04 ± 0.18 abcd | 0.76 ± 0.08 a | 0.40 ± 0.03 ab | 0.76 ± 0.03 ab | 0.59 ± 0.13 ab |

| 10% dried sourdough | 1.10 ± 0.18 bcd | 0.67 ± 0.16 a | 0.42 ± 0.06 ab | 0.76 ± 0.06 abc | 0.58 ± 0.19 ab |

| 20% carob flour | |||||

| 0% dried sourdough | 2.11 ± 0.60 f | 0.64 ± 0.10 a | 0.33 ± 0.05 a | 0.76 ± 0.07 abc | 1.02 ± 0.31 c |

| 5% dried sourdough | 1.55 ± 0.25 def | 0.71 ± 0.09 a | 0.35 ± 0.03 ab | 0.73 ± 0.04 a | 0.80 ± 0.14 bc |

| 10% dried sourdough | 1.51 ± 0.26 cde | 0.71 ± 0.10 a | 0.38 ± 0.04 ab | 0.75 ± 0.05 ab | 0.79 ± 0.17 bc |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zahorec, J.; Šoronja-Simović, D.; Petrović, J.; Dokić, L.; Lončarević, I.; Nikolić, I. Dried Sourdough as a Functional Tool for Enhancing Carob-Enriched Wheat Bread. Processes 2025, 13, 3699. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13113699

Zahorec J, Šoronja-Simović D, Petrović J, Dokić L, Lončarević I, Nikolić I. Dried Sourdough as a Functional Tool for Enhancing Carob-Enriched Wheat Bread. Processes. 2025; 13(11):3699. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13113699

Chicago/Turabian StyleZahorec, Jana, Dragana Šoronja-Simović, Jovana Petrović, Ljubica Dokić, Ivana Lončarević, and Ivana Nikolić. 2025. "Dried Sourdough as a Functional Tool for Enhancing Carob-Enriched Wheat Bread" Processes 13, no. 11: 3699. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13113699

APA StyleZahorec, J., Šoronja-Simović, D., Petrović, J., Dokić, L., Lončarević, I., & Nikolić, I. (2025). Dried Sourdough as a Functional Tool for Enhancing Carob-Enriched Wheat Bread. Processes, 13(11), 3699. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13113699