Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Antioxidant Compounds from Pomegranate Peels and Simultaneous Machine Learning Optimization Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents

2.2. Instrumentation

2.3. Pomegranate Peel Material Handling

2.4. Experimental Design

2.5. Bioactive Compounds Quantification

2.5.1. Determination of Total Polyphenol Content (TPC)

2.5.2. Determination of Total Flavonoid Content (TFC)

2.5.3. Determination of Total Anthocyanin Content (TAC)

2.5.4. Determination of Ascorbic Acid Content (AAC)

2.6. Antioxidant Assays

2.6.1. Ferric-Reducing Antioxidant Power (FRAP) Assay

2.6.2. DPPH• Antiradical Activity Assay

2.7. Statistical Analysis

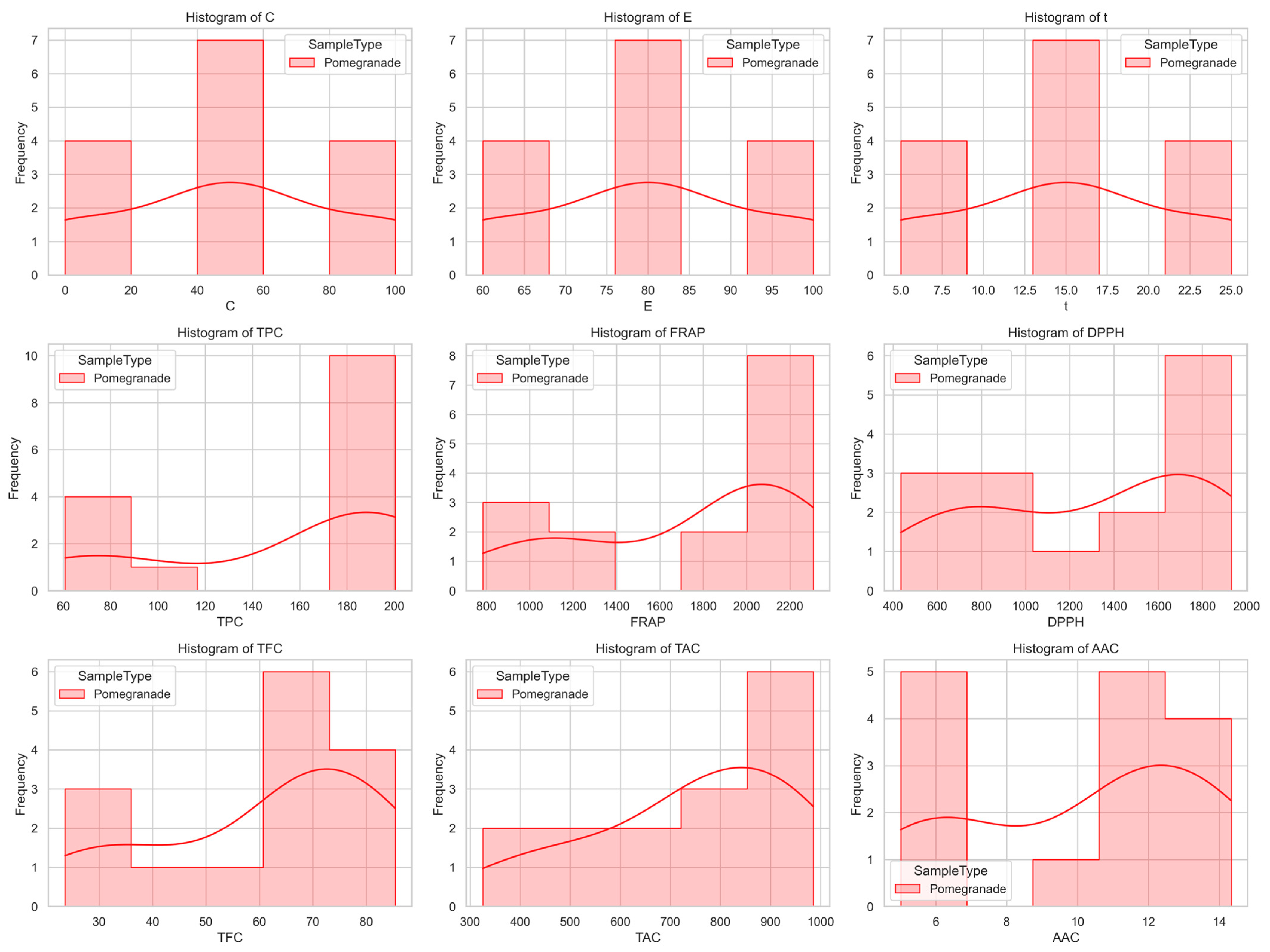

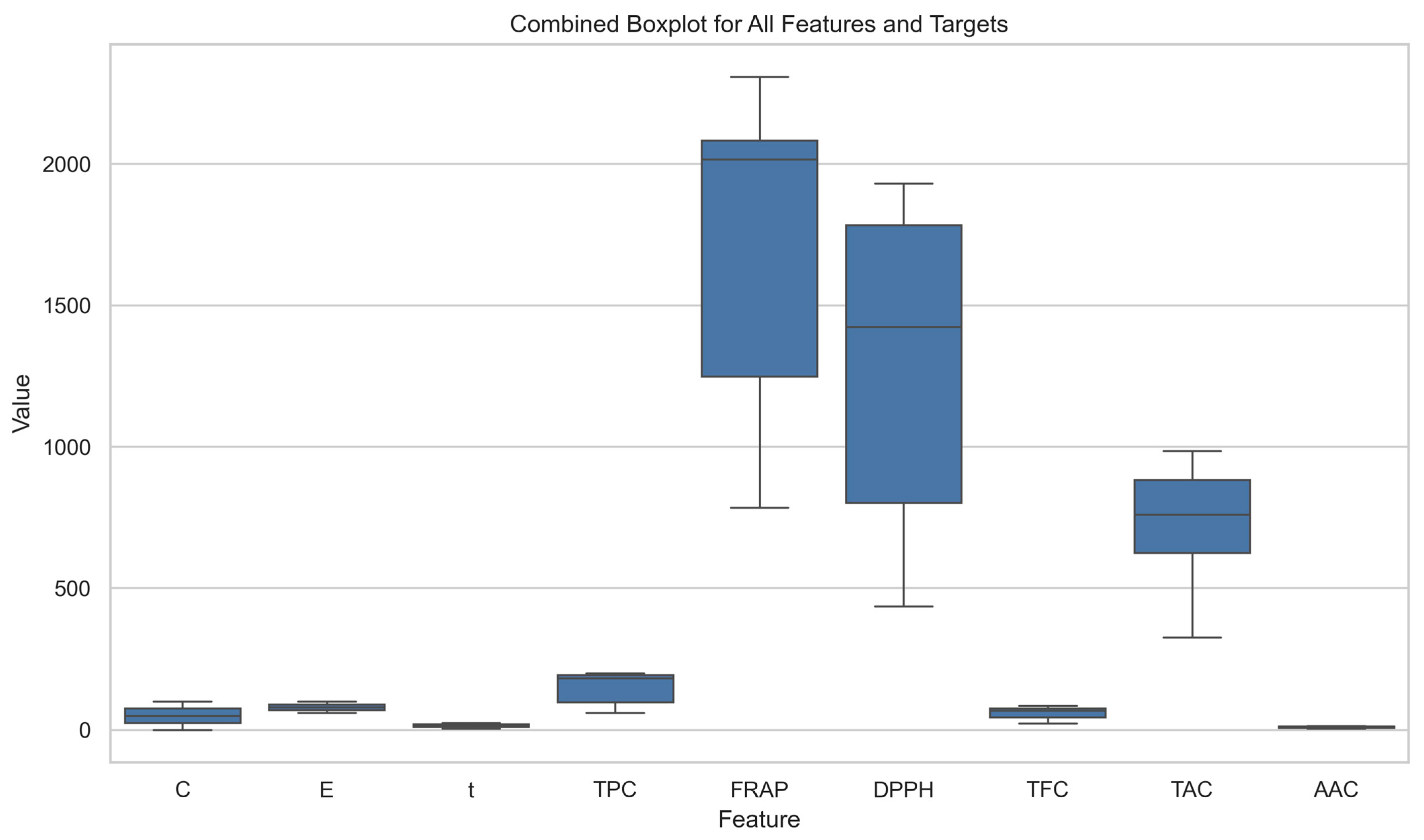

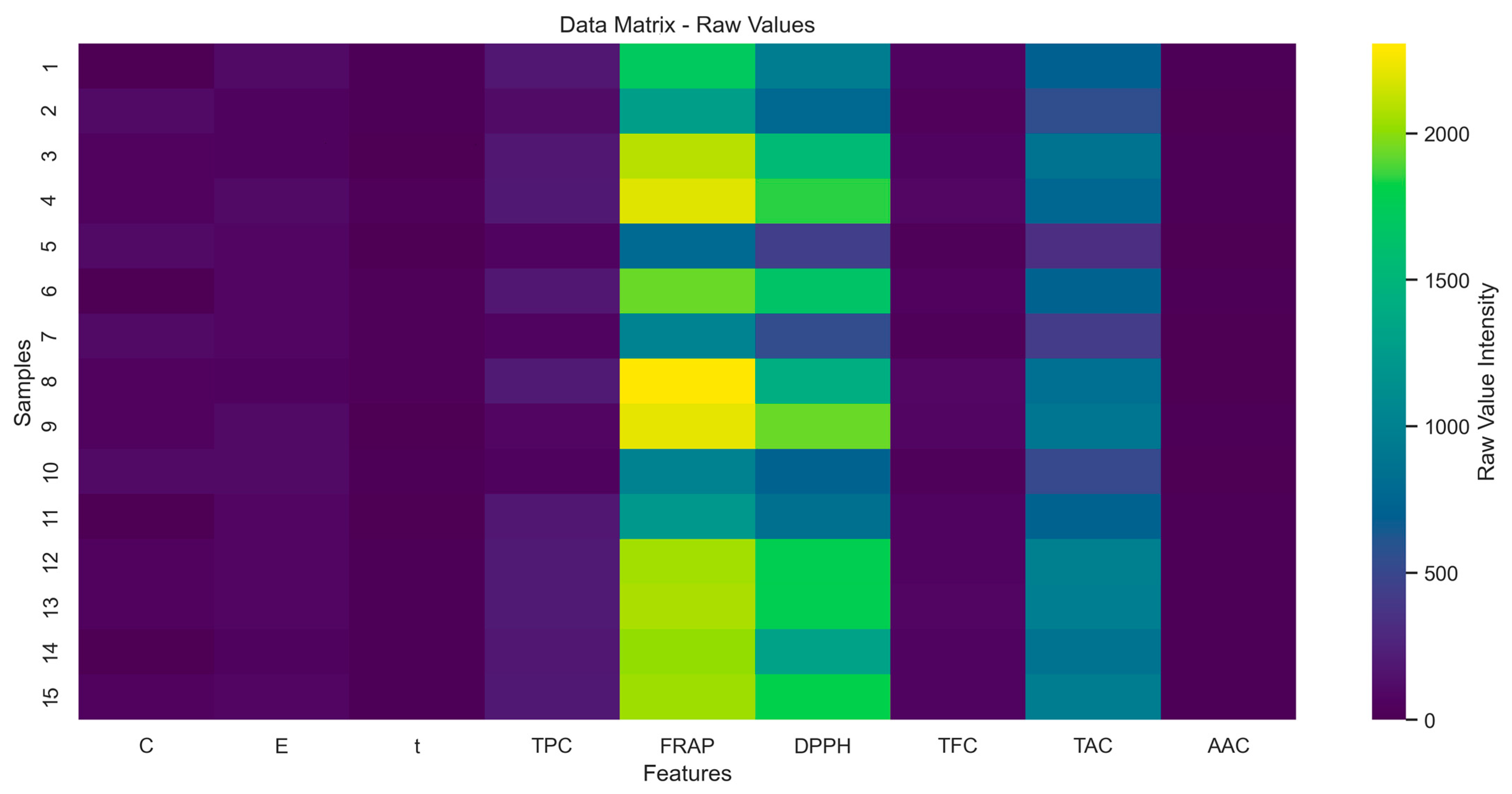

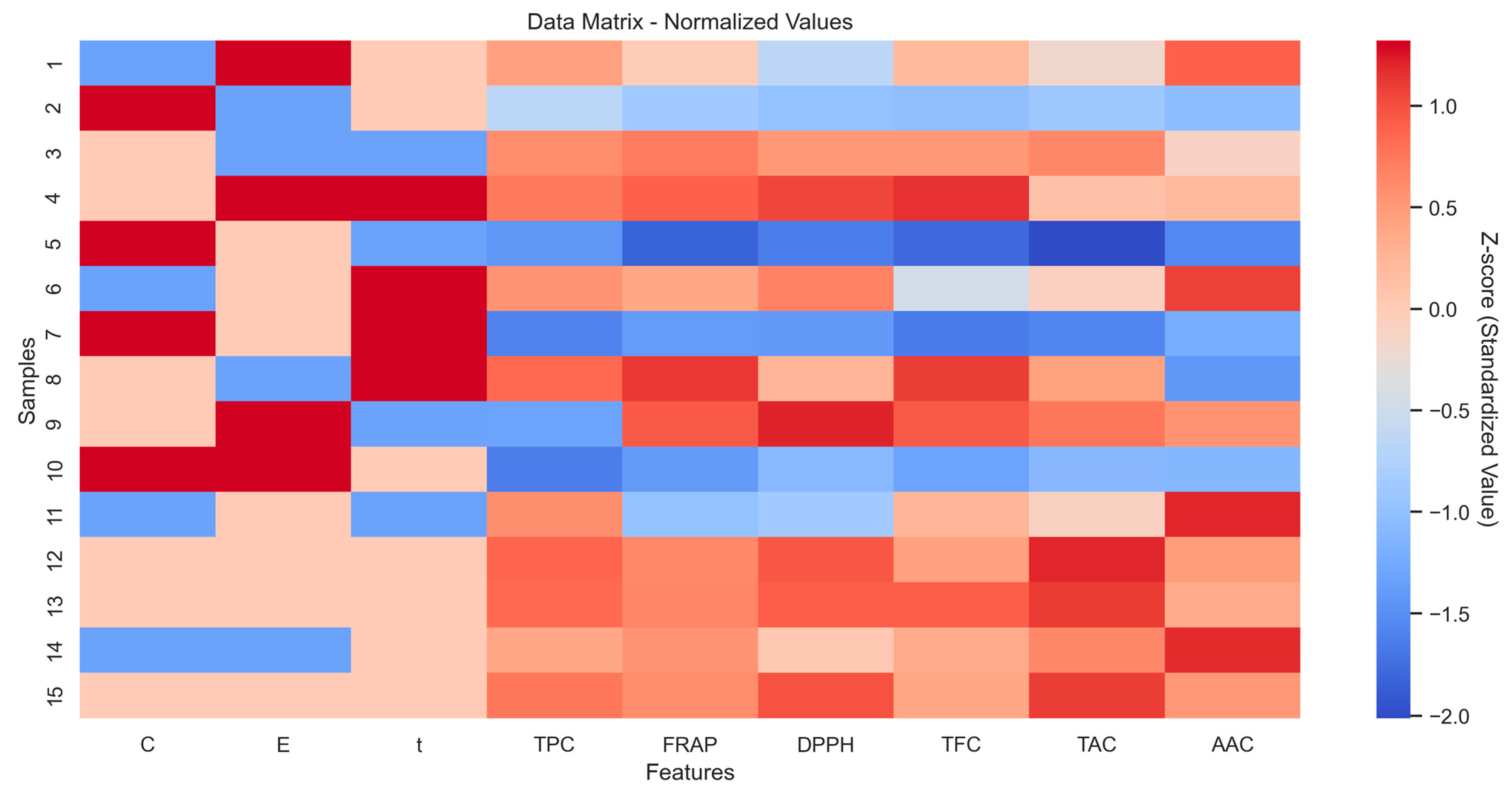

2.8. Initial Dataset Exploration and Visualization

2.9. Regression Modeling Framework

2.10. Candidate Regressors and Hyperparameter Grids

2.11. Training Augmentation by SMOTE Interpolation

2.12. Metrics

2.13. Rationale for the Final Regressor and Interpretability

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Optimization of UAE Parameters

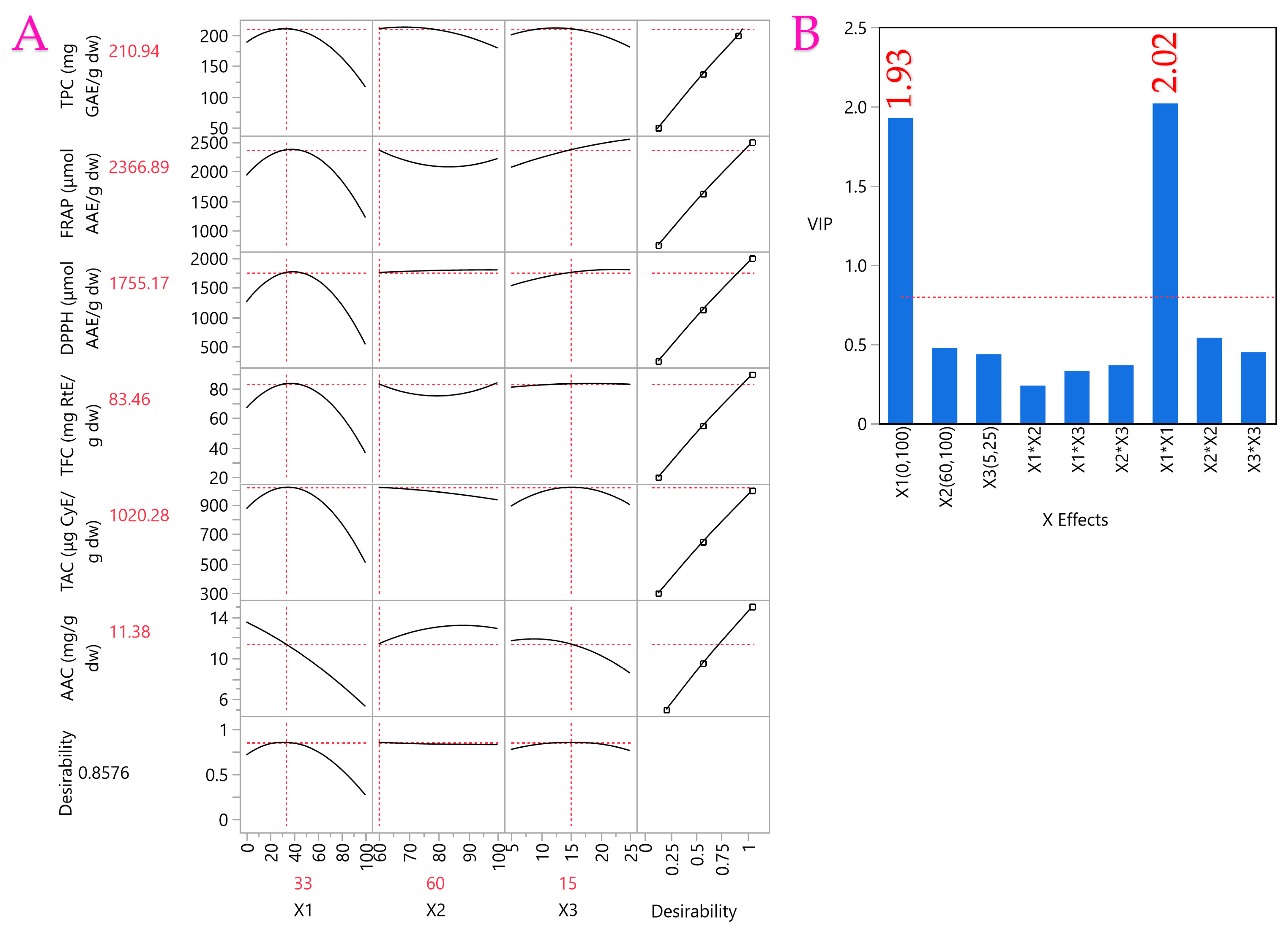

3.2. Model Analysis

3.3. Impact of Extraction Parameters to Assays Through Pareto Plot Analysis

3.4. PCA and MCA

3.5. Partial Least Squares (PLS) Analysis

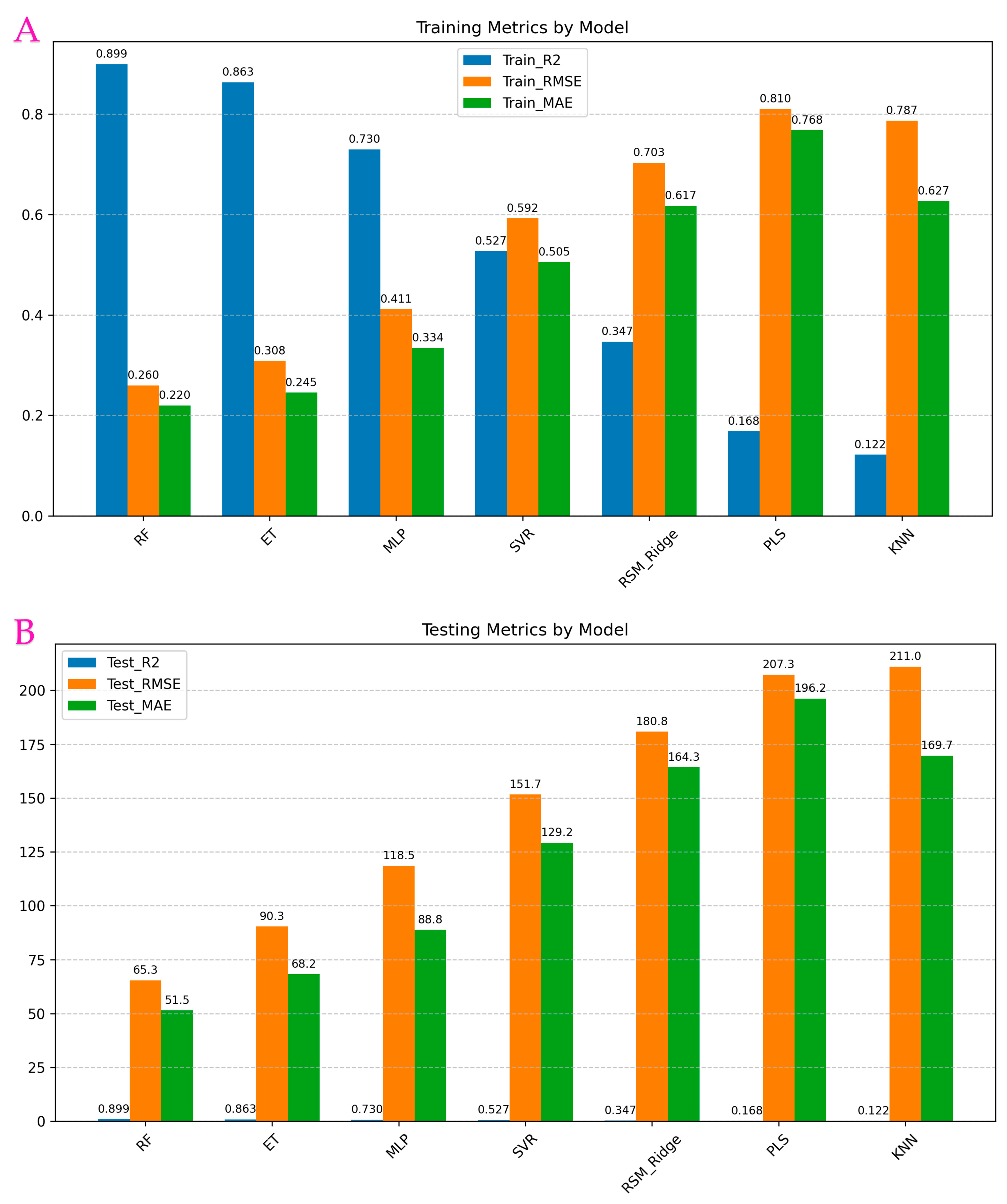

3.6. Performance of Machine Learning Regressors

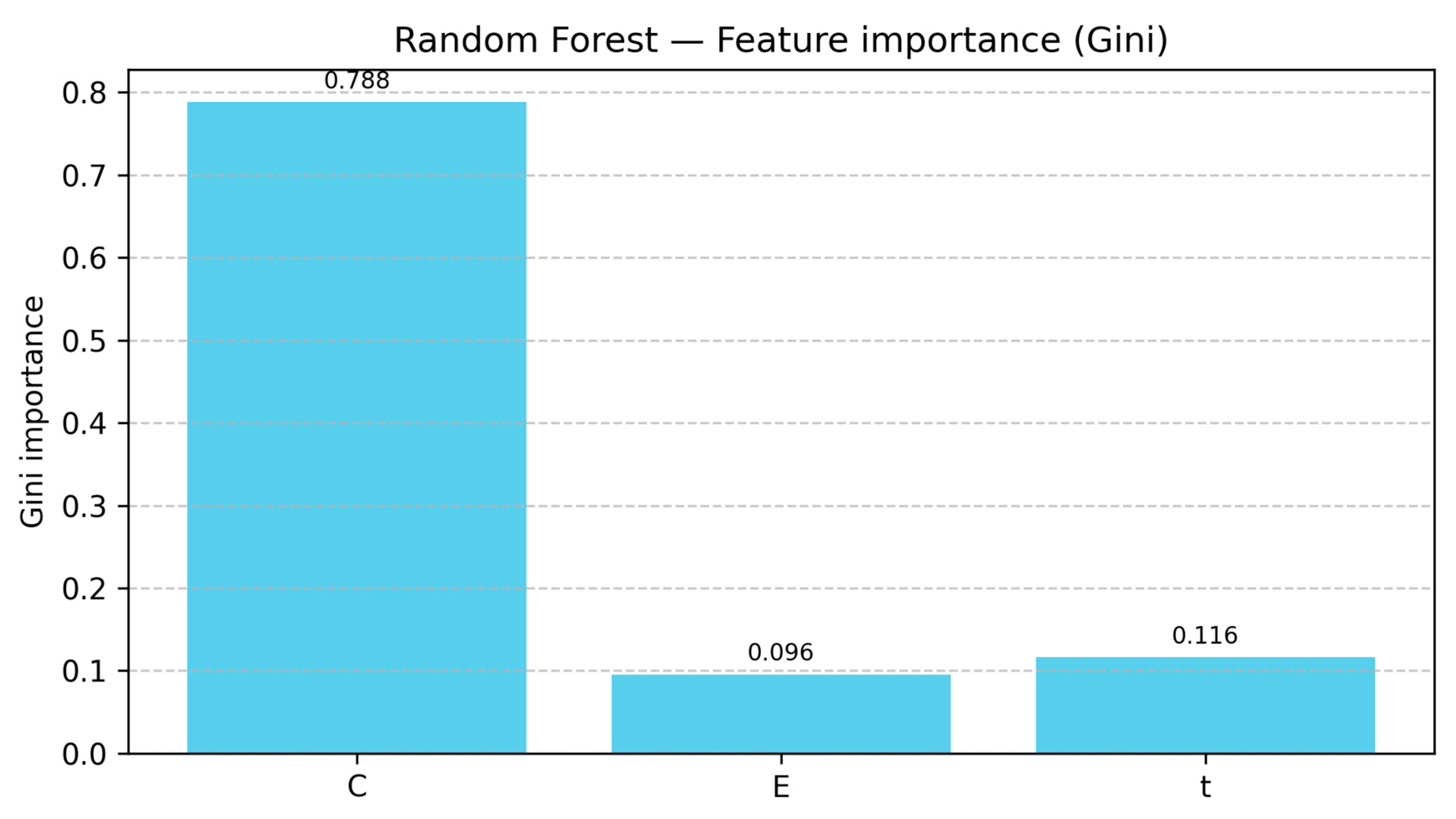

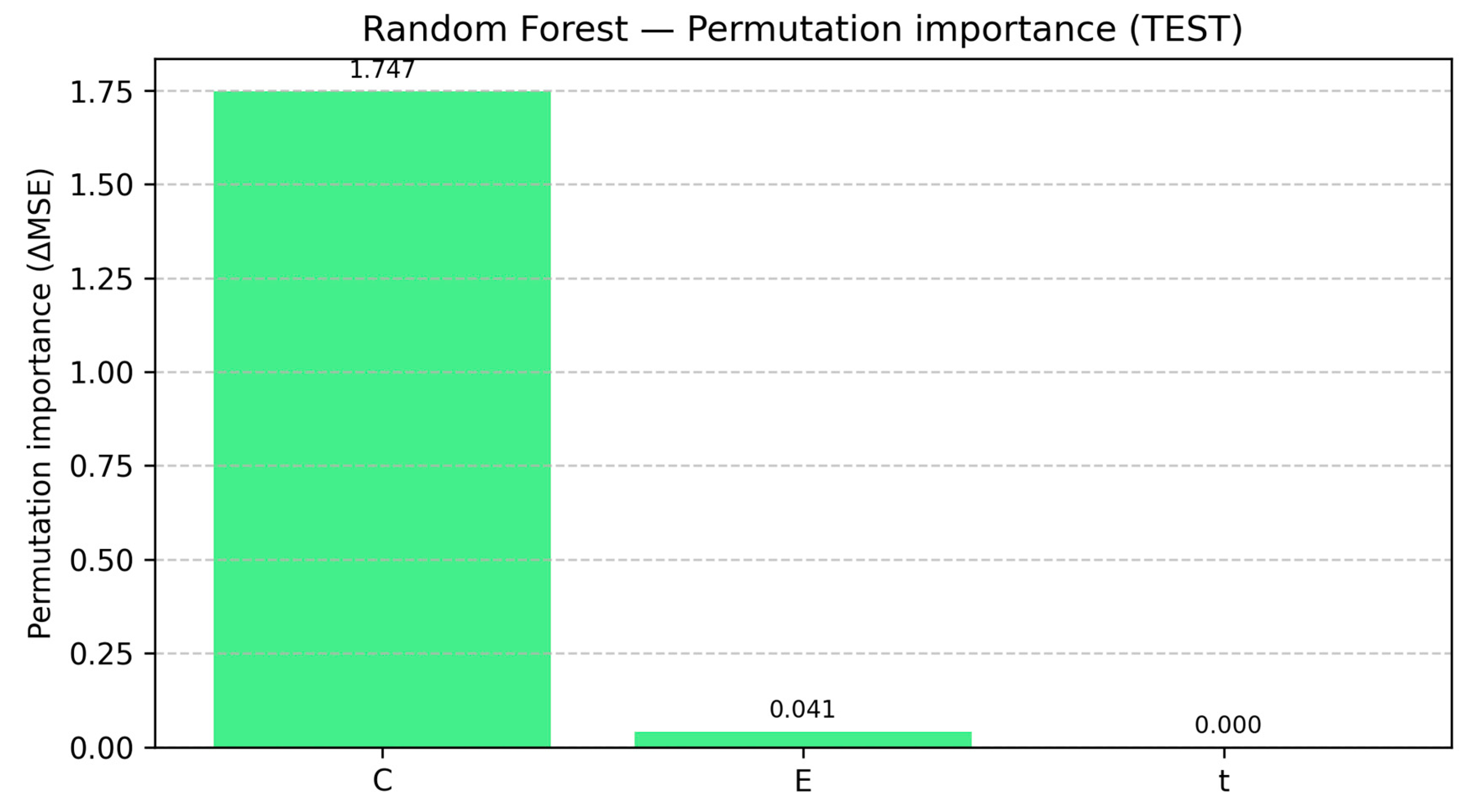

3.7. Feature Importance Analysis Across RF-Based Model

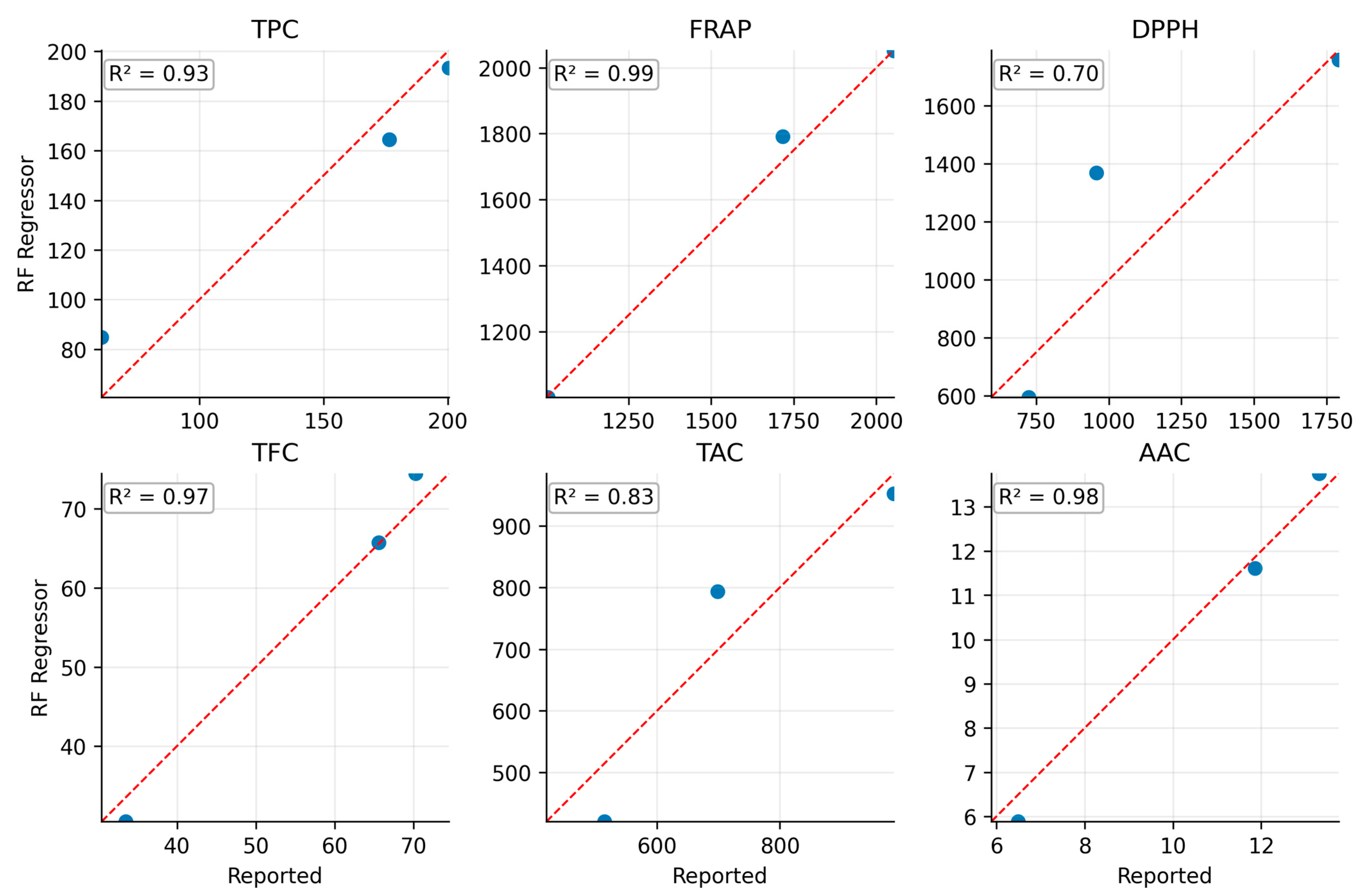

3.8. Actual vs. Predicted Performance RF-Based Model

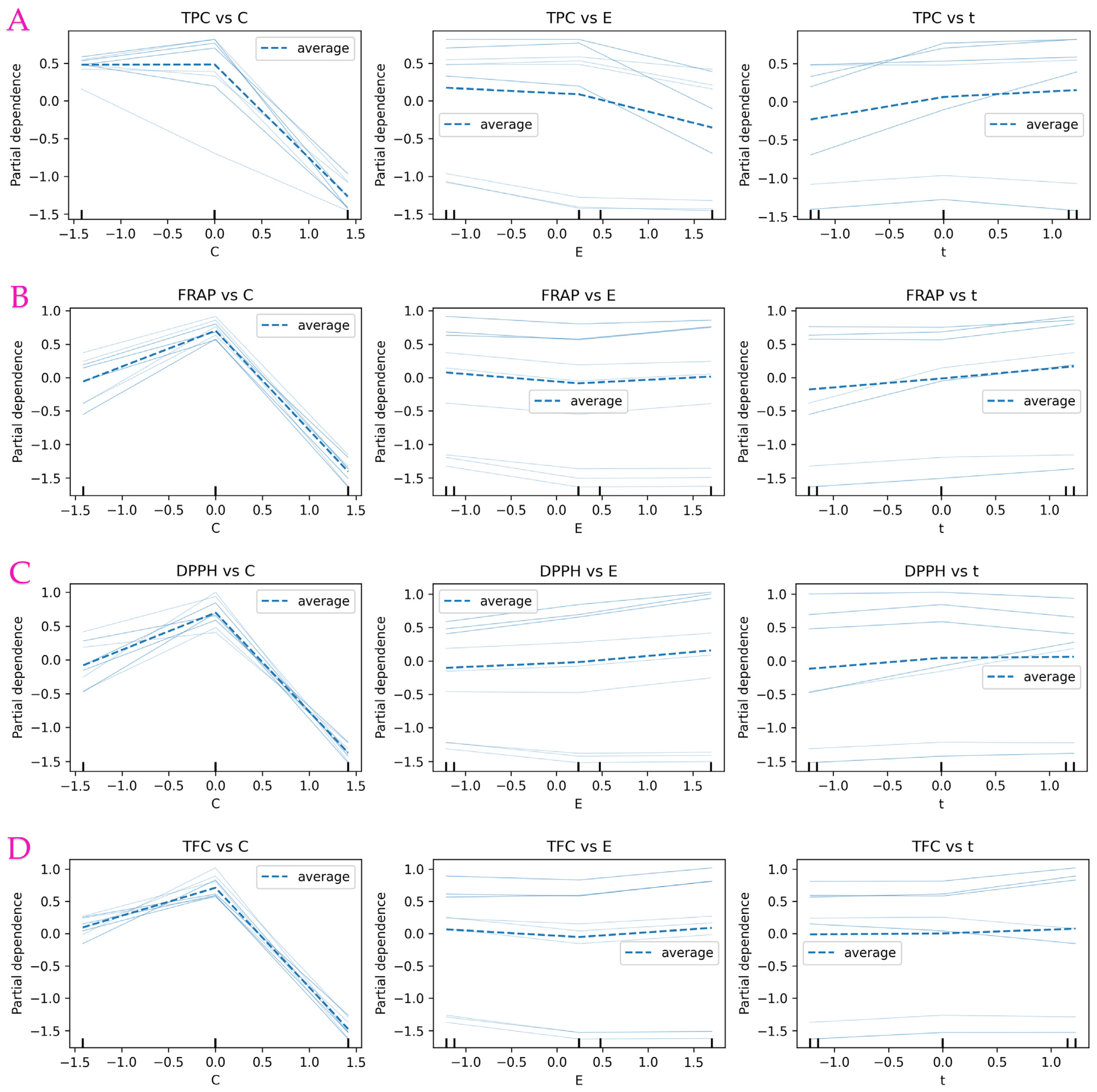

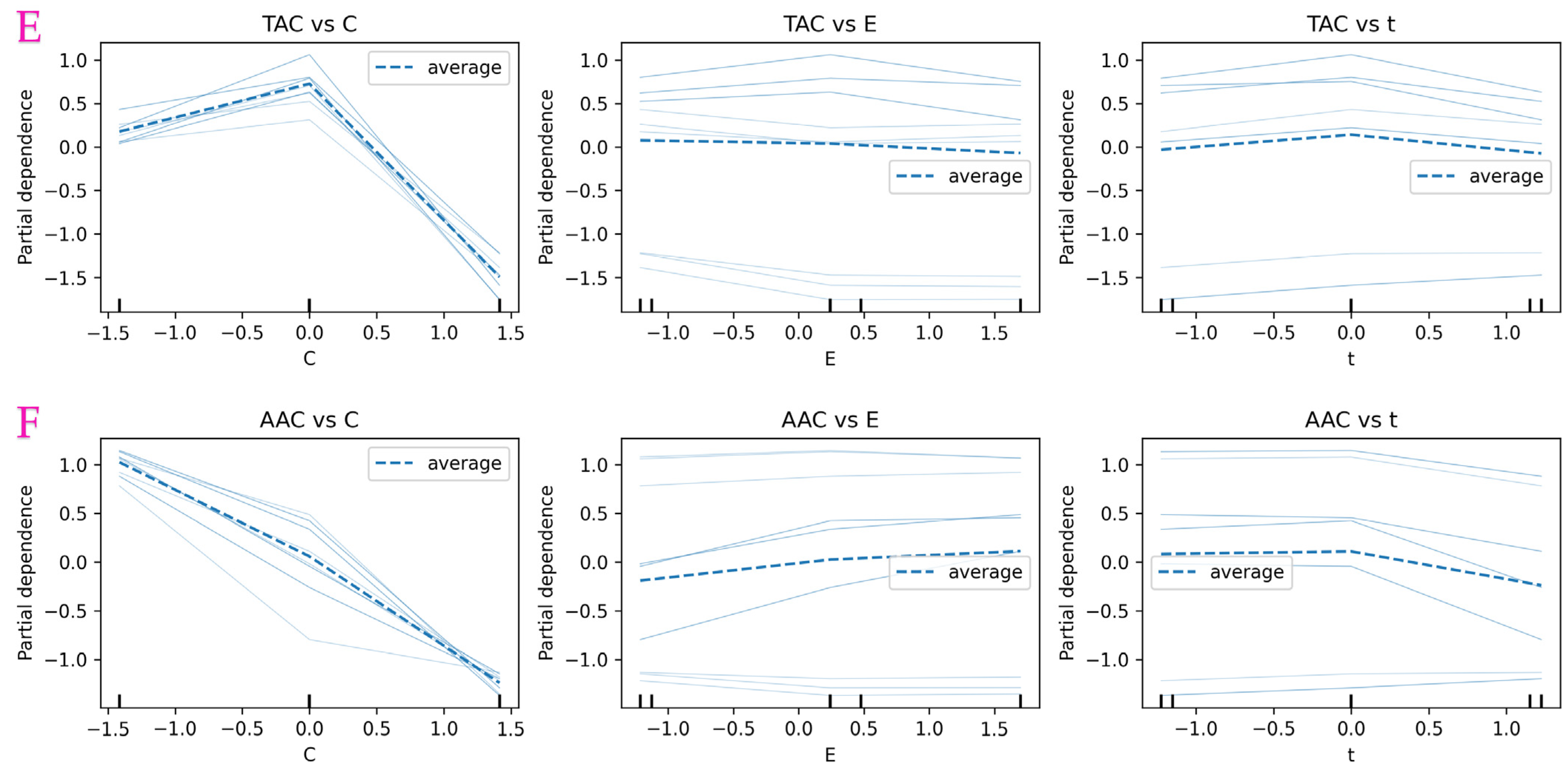

3.9. Partial Dependence Analysis of RF-Based Model

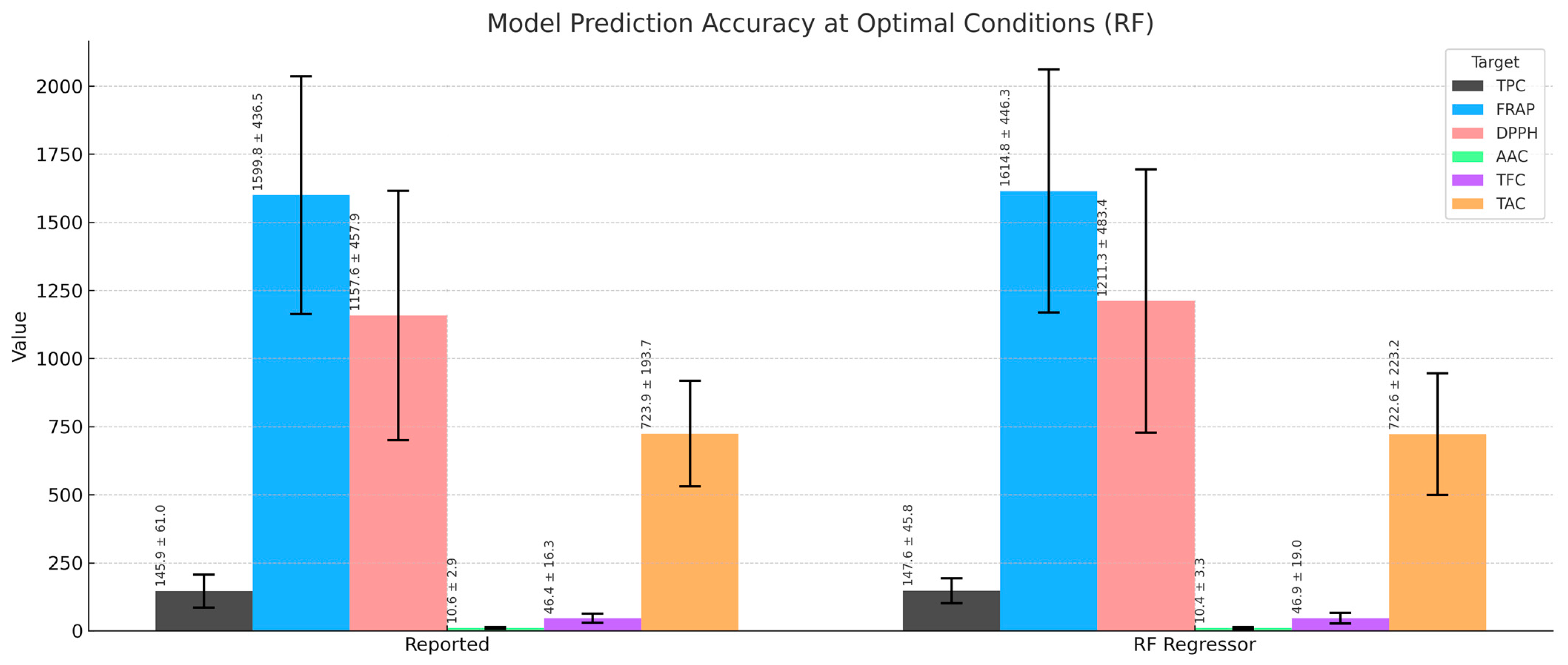

3.10. Model Prediction Accuracy at Optimal Conditions

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ain, H.B.U.; Tufail, T.; Bashir, S.; Ijaz, N.; Hussain, M.; Ikram, A.; Farooq, M.A.; Saewan, S.A. Nutritional Importance and Industrial Uses of Pomegranate Peel: A Critical Review. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 11, 2589–2598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Kady, A.M.; Abdel-Rahman, I.A.M.; Fouad, S.S.; Allemailem, K.S.; Istivan, T.; Ahmed, S.F.M.; Hasan, A.S.; Osman, H.A.; Elshabrawy, H.A. Pomegranate Peel Extract Is a Potential Alternative Therapeutic for Giardiasis. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drinić, Z.; Mudrić, J.; Zdunić, G.; Bigović, D.; Menković, N.; Šavikin, K. Effect of Pomegranate Peel Extract on the Oxidative Stability of Pomegranate Seed Oil. Food Chem. 2020, 333, 127501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaderides, K.; Kyriakoudi, A.; Mourtzinos, I.; Goula, A.M. Potential of Pomegranate Peel Extract as a Natural Additive in Foods. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 115, 380–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghadam, M.; Salami, M.; Mohammadian, M.; Khodadadi, M.; Emam-Djomeh, Z. Development of Antioxidant Edible Films Based on Mung Bean Protein Enriched with Pomegranate Peel. Food Hydrocoll. 2020, 104, 105735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azmat, F.; Safdar, M.; Ahmad, H.; Khan, M.R.J.; Abid, J.; Naseer, M.S.; Aggarwal, S.; Imran, A.; Khalid, U.; Zahra, S.M.; et al. Phytochemical Profile, Nutritional Composition of Pomegranate Peel and Peel Extract as a Potential Source of Nutraceutical: A Comprehensive Review. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 12, 661–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, N.; Daniloski, D.; Pratibha, N.; D’Cunha, N.M.; Naumovski, N.; Petkoska, A.T. Pomegranate Peel Extract–A Natural Bioactive Addition to Novel Active Edible Packaging. Food Res. Int. 2022, 156, 111378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Ali, S. Application of Raw and Modified Pomegranate Peel for Wastewater Treatment: A Literature Overview and Analysis. Int. J. Chem. Eng. 2021, 2021, 8840907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Q.; Li, M.; Wen, J.; Ren, F.; Yang, Z.; Jiang, X.; Chen, Y. The Bioactivity and Applications of Pomegranate Peel Extract: A Review. J. Food Biochem. 2022, 46, e14105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Niaaj, L.F.; Al-Daghistani, H.I.; Katampe, I.; Abu-Irmaileh, B.; Bustanji, Y.K. Pomegranate Peel: Bioactivities as Antimicrobial and Cytotoxic Agents. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 12, 2818–2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpentieri, S.; Soltanipour, F.; Ferrari, G.; Pataro, G.; Donsì, F. Emerging Green Techniques for the Extraction of Antioxidants from Agri-Food By-Products as Promising Ingredients for the Food Industry. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanasiadis, V.; Mantiniotou, M.; Kalompatsios, D.; Makrygiannis, I.; Alibade, A.; Lalas, S.I. Evaluation of Antioxidant Properties of Residual Hemp Leaves Following Optimized Pressurized Liquid Extraction. AgriEngineering 2025, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, T.C.; Souza, V.P.; Padilha, A.P.F.; Duarte, F.A.; Flores, E.M. Trends and Perspectives on the Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Bioactive Compounds Using Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 2025, 47, 101088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, M.V.; Sengar, A.S.; Rawson, A. Ultrasonication-A Green Technology Extraction Technique for Spices: A Review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 116, 975–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guddi, K.; Sarkar, A. Optimization of Green Extraction Technologies for Recovering Bioactive Compounds from Ixora coccinea Waste Flower Biomass: A Comparative Response Surface Methodology and Artificial Neural Network Modeling. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2024, 42, 101830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, S.; Kurtulbaş, E. Green Extraction and Valorization of By-Products from Food Processing. Foods 2024, 13, 1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harikrishnan, S.; Kaushik, D.; Rasane, P.; Kumar, A.; Kaur, N.; Reddy, C.K.; Proestos, C.; Oz, F.; Kumar, M. Artificial Intelligence in Sustainable Food Design: Technological, Ethical Consideration, and Future. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 163, 105152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, B.; Buehler, M.J.; Chow, Y.; Gligoric, K.; Jurafsky, D.; Kaplan, D.L.; Ledesma-Amaro, R.; Missier, G.D.; Neidhardt, L.; Pichara, K.; et al. AI for Sustainable Future Foods. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2509.21556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantiniotou, M.; Athanasiadis, V.; Liakos, K.G.; Bozinou, E.; Lalas, S.I. Artificial Intelligence and Extraction of Bioactive Compounds: The Case of Rosemary and Pressurized Liquid Extraction. Processes 2025, 13, 1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Bao, X.; Zhu, Y.; Dai, Z.; Shen, Q.; Xue, Y. Advances in Machine Learning Screening of Food Bioactive Compounds. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 150, 104578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Li, H.; Liu, J.; Du, S. Review of Intelligent Modeling for Sintering Process Under Variable Operating Conditions. Processes 2025, 13, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanasiadis, V.; Chatzimitakos, T.; Mantiniotou, M.; Kalompatsios, D.; Bozinou, E.; Lalas, S.I. Investigation of the Polyphenol Recovery of Overripe Banana Peel Extract Utilizing Cloud Point Extraction. Eng 2023, 4, 3026–3038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Durst, R.W.; Wrolstad, R.E. Collaborators: Determination of Total Monomeric Anthocyanin Pigment Content of Fruit Juices, Beverages, Natural Colorants, and Wines by the pH Differential Method: Collaborative Study. J. AOAC Int. 2005, 88, 1269–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanasiadis, V.; Chatzimitakos, T.; Mantiniotou, M.; Bozinou, E.; Lalas, S.I. Exploring the Antioxidant Properties of Citrus Limon (Lemon) Peel Ultrasound Extract after the Cloud Point Extraction Method. Biomass 2024, 4, 202–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemat, F.; Rombaut, N.; Sicaire, A.-G.; Meullemiestre, A.; Fabiano-Tixier, A.-S.; Abert-Vian, M. Ultrasound Assisted Extraction of Food and Natural Products. Mechanisms, Techniques, Combinations, Protocols and Applications. A Review. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2017, 34, 540–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frosi, I.; Montagna, I.; Colombo, R.; Milanese, C.; Papetti, A. Recovery of Chlorogenic Acids from Agri-Food Wastes: Updates on Green Extraction Techniques. Molecules 2021, 26, 4515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalompatsios, D.; Athanasiadis, V.; Mantiniotou, M.; Lalas, S.I. Optimization of Ultrasonication Probe-Assisted Extraction Parameters for Bioactive Compounds from Opuntia macrorhiza Using Taguchi Design and Assessment of Antioxidant Properties. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picot-Allain, C.; Mahomoodally, M.F.; Ak, G.; Zengin, G. Conventional versus Green Extraction Techniques—a Comparative Perspective. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2021, 40, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdu, O.H.; Saeed, A.A.M.; Fdhel, T.A. Polyphenols/Flavonoids Analysis and Antimicrobial Activity in Pomegranate Peel Extracts. Electron. J. Univ. Aden Basic Appl. Sci. 2020, 1, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanlayavattanakul, M.; Chongnativisit, W.; Chaikul, P.; Lourith, N. Phenolic-Rich Pomegranate Peel Extract: In Vitro, Cellular, and In Vivo Activities for Skin Hyperpigmentation Treatment. Planta Med. 2020, 86, 749–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rababah, T.M.; Banat, F.; Rababah, A.; Ereifej, K.; Yang, W. Optimization of Extraction Conditions of Total Phenolics, Antioxidant Activities, and Anthocyanin of Oregano, Thyme, Terebinth, and Pomegranate. J. Food Sci. 2010, 75, C626–C632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfalleh, W.; Hannachi, H.; Tlili, N.; Yahia, Y.; Nasri, N.; Ferchichi, A. Total Phenolic Contents and Antioxidant Activities of Pomegranate Peel, Seed, Leaf and Flower. J. Med. Plants Res. 2012, 6, 4724–4730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaderides, K.; Papaoikonomou, L.; Serafim, M.; Goula, A.M. Microwave-Assisted Extraction of Phenolics from Pomegranate Peels: Optimization, Kinetics, and Comparison with Ultrasounds Extraction. Chem. Eng. Process.-Process Intensif. 2019, 137, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Guo, C.; Yang, J.; Wei, J.; Xu, J.; Cheng, S. Evaluation of Antioxidant Properties of Pomegranate Peel Extract in Comparison with Pomegranate Pulp Extract. Food Chem. 2006, 96, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Independent Variables | Coded Units | Coded Levels | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| −1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Ethanol concentration (C, % v/v) | X1 | 0 | 50 | 100 |

| Ultrasonic power (E, %) | X2 | 60 | 80 | 100 |

| Extraction time (t, min) | X3 | 5 | 15 | 25 |

| Model | Tuned Parameters | Values Tested |

|---|---|---|

| RSM_Ridge | ridge_alpha | 0.1, 1.0, 10, 100 |

| PLS | n_components | 1, 2, 3 |

| KNN | n_neighbors|weights | 3, 5, 7|uniform, distance |

| SVR | C|epsilon|γ | 1, 10|0.1, 0.2|scale |

| MLP | hidden_layer_sizes|alpha | (64), (64,64), (128)| 1 × 10−4, 1 × 10−3 |

| RF | max_depth|min_samples_leaf | None, 6, 10|1, 2, 4 |

| ET | max_depth|min_samples_leaf | None, 6, 10|1, 2, 4 |

| XGB | n_estimators|max_depth|learning_rate|subsample|colsample_bytree|min_child_weight|reg_lambda|reg_alpha | 300, 600|3, 6|0.03, 0.10|0.7, 1.0|0.7, 1.0|1, 5|1.0, 5.0|0.0, 0.1 |

| Parameter | Values Tested | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Number of synthetic samples | 200, 1000 | Total number of synthetic points generated per training split |

| Nearest neighbors | 5, 7 | Number of neighbors considered in predictor space for interpolation |

| Target noise | 0.02, 0.05 | Gaussian noise added to interpolated targets |

| Clamping of predictors | True | Prevented extrapolation beyond empirical design space |

| Grouping in cross-validation | True | Synthetic samples inherited anchor index; all members retained in the same fold during GroupKFold |

| Synthetic sample weight | 0.2 | Reduced influence of synthetic points relative to real samples |

| Generation space | Standardized predictors and targets | Interpolation and perturbation applied after scaling |

| Design Point | Independent Variables | Actual UAE Responses * | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C (%) (X1) | E (%) (X2) | t (min) (X3) | TPC | TFC | TAC | AAC | FRAP | DPPH | |

| 1 | 0 | 100 | 15 | 176.51 ± 2.86 | 65.57 ± 0.55 | 698.61 ± 37.91 | 13.32 ± 0.21 | 1717.18 ± 6.98 | 956.75 ± 18.97 |

| 2 | 100 | 60 | 15 | 115.83 ± 1.57 | 39.57 ± 1.62 | 552.49 ± 15.12 | 6.75 ± 0.48 | 1274.7 ± 5.27 | 771.48 ± 18.26 |

| 3 | 50 | 60 | 5 | 185.15 ± 3.49 | 71.8 ± 0.1 | 870.6 ± 50.64 | 9.91 ± 0.1 | 2099.51 ± 8.35 | 1558 ± 18.36 |

| 4 | 50 | 100 | 25 | 193.3 ± 5.65 | 85.45 ± 1.01 | 759.66 ± 48.41 | 10.9 ± 0.3 | 2193.96 ± 6.05 | 1843.73 ± 18.48 |

| 5 | 100 | 80 | 5 | 72.03 ± 1.41 | 23.61 ± 0.26 | 325.59 ± 51.03 | 5.01 ± 0.51 | 784.22 ± 8.33 | 435.21 ± 1.5 |

| 6 | 0 | 80 | 25 | 182.19 ± 3.96 | 51.15 ± 0.27 | 723.76 ± 36.97 | 13.9 ± 0.52 | 1931.04 ± 6.99 | 1650.79 ± 13.87 |

| 7 | 100 | 80 | 25 | 63.61 ± 2.98 | 26.2 ± 0.11 | 417.88 ± 49.26 | 6.11 ± 0.02 | 1010.61 ± 3.88 | 547.7 ± 24.67 |

| 8 | 50 | 60 | 25 | 199.09 ± 1.1 | 84.08 ± 0.31 | 827.3 ± 93.55 | 5.46 ± 0.07 | 2307.56 ± 1.47 | 1423.61 ± 18.43 |

| 9 | 50 | 100 | 5 | 78.8 ± 0.33 | 80.69 ± 1.46 | 893.78 ± 43.88 | 12.1 ± 0.16 | 2213.82 ± 8.4 | 1930.47 ± 19.6 |

| 10 | 100 | 100 | 15 | 60.73 ± 0.5 | 33.48 ± 0.63 | 514.63 ± 77.19 | 6.49 ± 0.44 | 1005.78 ± 6.68 | 724.91 ± 7.05 |

| 11 | 0 | 80 | 5 | 184.56 ± 5.1 | 66.15 ± 0.5 | 719.42 ± 19.06 | 14.33 ± 0.55 | 1222.61 ± 9.45 | 832.06 ± 15.53 |

| 12 | 50 | 80 | 15 | 200.46 ± 0.19 | 70.25 ± 0.66 | 985.33 ± 83.2 | 11.86 ± 0.26 | 2052.75 ± 7.6 | 1791.2 ± 44.31 |

| 13 | 50 | 80 | 15 | 198.98 ± 3.2 | 80.16 ± 0.15 | 968.04 ± 69.61 | 11.44 ± 0.22 | 2067.99 ± 5.76 | 1776.7 ± 27.09 |

| 14 | 0 | 60 | 15 | 174.05 ± 1.75 | 68.6 ± 0.41 | 869.74 ± 82.67 | 14.26 ± 0.12 | 2015.99 ± 7.39 | 1313.83 ± 14.49 |

| 15 | 50 | 80 | 15 | 194.15 ± 1.01 | 69.24 ± 0.5 | 963.58 ± 5.12 | 11.99 ± 0.11 | 2039.07 ± 7.96 | 1803.34 ± 30.98 |

| Factor | TPC | TFC | TAC | AAC | FRAP | DPPH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Least squares regression | ||||||

| Intercept | 197.9 * | 73.22 * | 972.3 * | 11.76 * | 2053 * | 1790 * |

| X1—ethanol concentration | −50.6 * | −16.1 * | −150 * | −3.93 * | −351 * | −284 * |

| X2—ultrasonic power | −20.6 | 0.143 | −31.7 | 0.804 | −70.9 | 48.62 |

| X3—extraction time | 14.71 | 0.579 | −10.1 | −0.62 | 140.4 * | 88.76 |

| X1X2 | −14.4 | −0.77 | 33.32 | 0.17 | 7.472 | 77.63 |

| X1X3 | −1.51 | 4.398 | 21.99 | 0.383 | −121 | −177 |

| X2X3 | 25.14 | −1.88 | −22.7 | 0.813 | −57 | 11.91 |

| X12 | −52.3 * | −30.1 * | −302 * | −0.66 | −758 * | −836 * |

| X22 | −13.8 | 8.658 | −11.1 | −0.9 | 208.4 * | −13.1 |

| X32 | −20 | −1.37 | −123 * | −1.27 | −57.9 | −88.4 |

| ANOVA | ||||||

| F-value (model) | 6.798 | 14.17 | 17.74 | 5.062 | 18.15 | 4.688 |

| F-value (lack of fit) | 100.2 | 1.469 | 44.69 | 63.32 | 177.1 | 769.6 |

| p-Value (model) | 0.0241 * | 0.0047 * | 0.0028 * | 0.0444 * | 0.0026 * | 0.0518 |

| p-Value (lack of fit) | 0.0099 * | 0.4296 | 0.0220 * | 0.0156 * | 0.0056 * | 0.0013 * |

| R2 | 0.924 | 0.962 | 0.97 | 0.901 | 0.97 | 0.894 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.788 | 0.894 | 0.915 | 0.723 | 0.917 | 0.703 |

| RMSE | 25.67 | 6.83 | 59.93 | 1.781 | 149.4 | 286.7 |

| CV | 35.32 | 33.76 | 27.8 | 31.33 | 29.51 | 38.56 |

| DF (total) | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 |

| Parameters | Independent Variables | Desirability | Least Squares Regression | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C (%) (X1) | E (%) (X2) | t (min) (X3) | |||

| TPC (mg GAE/g dw) | 28 | 72 | 16 | 0.9201 | 213.85 ± 35.21 |

| FRAP (μmol AAE/g dw) | 36 | 60 | 24 | 0.9912 | 2536.63 ± 315.81 |

| DPPH (μmol AAE/g dw) | 40 | 100 | 22 | 0.9186 | 1885.74 ± 526.97 |

| TFC (mg RtE/g dw) | 39 | 60 | 20 | 0.8994 | 84.05 ± 11.67 |

| TAC (μg CyE/g dw) | 34 | 60 | 15 | 0.9930 | 1020.6 ± 98.31 |

| AAC (mg/g dw) | 0 | 84 | 11 | 0.9920 | 15.26 ± 2.97 |

| Responses | TPC | FRAP | DPPH | TFC | TAC | AAC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TPC | - | 0.7900 | 0.7392 | 0.7607 | 0.8166 | 0.6960 |

| FRAP | - | 0.9416 | 0.9444 | 0.8918 | 0.4622 | |

| DPPH | - | 0.8941 | 0.8941 | 0.4742 | ||

| TFC | - | 0.9188 | 0.5837 | |||

| TAC | - | 0.6240 | ||||

| AAC | - |

| Parameters | Independent Variables | Desirability | PLS Regression | Experimental Values | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C (%) (X1) | E (%) (X2) | t (min) (X3) | ||||

| TPC (mg GAE/g dw) | 33 | 60 | 15 | 0.8576 | 210.94 | 195.55 ± 4.11 |

| FRAP (μmol AAE/g dw) | 2366.89 | 2627.78 ± 94.6 | ||||

| DPPH (μmol AAE/g dw) | 1755.17 | 1516.56 ± 78.86 | ||||

| TFC (mg RtE/g dw) | 83.46 | 74.78 ± 3.59 | ||||

| TAC (μg CyE/g dw) | 1020.28 | 992.87 ± 62.55 | ||||

| AAC (mg/g dw) | 11.38 | 15.68 ± 0.93 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mantiniotou, M.; Athanasiadis, V.; Liakos, K.G.; Bozinou, E.; Lalas, S.I. Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Antioxidant Compounds from Pomegranate Peels and Simultaneous Machine Learning Optimization Study. Processes 2025, 13, 3700. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13113700

Mantiniotou M, Athanasiadis V, Liakos KG, Bozinou E, Lalas SI. Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Antioxidant Compounds from Pomegranate Peels and Simultaneous Machine Learning Optimization Study. Processes. 2025; 13(11):3700. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13113700

Chicago/Turabian StyleMantiniotou, Martha, Vassilis Athanasiadis, Konstantinos G. Liakos, Eleni Bozinou, and Stavros I. Lalas. 2025. "Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Antioxidant Compounds from Pomegranate Peels and Simultaneous Machine Learning Optimization Study" Processes 13, no. 11: 3700. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13113700

APA StyleMantiniotou, M., Athanasiadis, V., Liakos, K. G., Bozinou, E., & Lalas, S. I. (2025). Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Antioxidant Compounds from Pomegranate Peels and Simultaneous Machine Learning Optimization Study. Processes, 13(11), 3700. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13113700