Abstract

To clarify the characteristics of CO2–formation water–rock reactions in tight sandstones and their effects on CO2-enhanced oil recovery (EOR) efficiency and storage efficiency, this study takes the tight oil reservoirs of the Changqing Jiyuan Oilfield as the research object. A variety of experimental techniques, including ICP-OES elemental analysis, powder X-ray diffraction, and scanning electron microscopy, were employed to systematically investigate the mechanisms and main influencing factors of water–rock reactions during CO2 geological storage. The study focused on analyzing the roles of mineral composition, reservoir pore structure, and formation water chemistry in the reaction process. It explored the potential impacts of reaction products on reservoir properties. Furthermore, based on the experimental results, a coupled reservoir numerical simulation of CO2 injection for EOR and storage was conducted to comprehensively evaluate the influence of mineralization processes on CO2 EOR performance and long-term storage efficiency. Results show that the tight sandstone reservoirs in Jiyuan Oilfield are mainly composed of calcite, quartz, and feldspar. The dominant water–rock reactions during CO2 formation–water interactions are calcite dissolution and feldspar dissolution. Among these, calcite dissolution is considered the controlling reaction due to its significant effect on the chemical composition of formation water, and the temporal variation in other elements shows a clear correlation with the calcite dissolution process. Further analysis reveals that water–rock reactions lead to permeability reduction in natural fractures near injection wells, thereby effectively improving CO2 EOR efficiency, enhancing sweep volume, and increasing reservoir recovery. At the end of the EOR stage, mineralized CO2 storage accounts for only 0.53% of the total stored CO2. However, with the extension of time, mineralized storage gradually increases, reaching a substantial 31.08% after 500 years. The study also reveals the effects of reservoir temperature, pressure, and formation water salinity on mineralization rates, emphasizing the importance of mineral trapping for long-term CO2 storage. These findings provide a theoretical basis and practical guidance for the joint optimization of CO2 EOR and geological sequestration. Future research may further focus on the dynamic evolution of water–rock reactions under different geological conditions to enhance the applicability and economic viability of CO2 storage technologies.

1. Introduction

As a key sector in unconventional oil and gas resource development, tight oil has attracted significant academic attention regarding its exploitation mechanisms and enhanced recovery technologies. Taking the Ordos Basin as an example, recovery factors under depletion development modes generally remain below 9%, while similar indicators in the North American Bakken Oilfield are also under 15% [1,2]. CO2-enhanced oil recovery technology has become a current research focus due to its dual benefits of improving crude oil recovery efficiency and sequestering greenhouse gases. It is noteworthy that after CO2 injection, multiphase interactions among the injected CO2, reservoir rock, and fluids significantly alter the pore structure characteristics of the reservoir, thereby affecting both oil displacement efficiency and storage stability [3,4,5,6]. CO2–water–rock interactions in tight sandstone reservoirs are fundamentally different from those in conventional reservoirs due to their unique pore structure. These reservoirs are characterized by a high abundance of nanopores, which results in extremely high capillary pressure and a large mineral surface-area-to-volume ratio. These features significantly restrict fluid flow and create distinct geochemical environments that can alter reaction kinetics and the transport of dissolved species [7]. Therefore, understanding these micro-scale phenomena is critical for accurately predicting reservoir behavior during CO2 injection.

Previous studies have shown that the CO2–water–rock interactions primarily manifest in three major geochemical reactions: (1) dynamic dissolution and reprecipitation of carbonate minerals; (2) non-equilibrium dissolution of feldspar minerals and structural evolution of clay minerals; and (3) selective formation of secondary minerals [6,7,8,9,10]. Bertier and colleagues [6] demonstrated through CO2 flooding experiments on Permian sandstones that mineral dissolution-driven optimization of the pore-throat network can increase reservoir permeability by one to two orders of magnitude. Bachu et al. [11], based on numerical simulation of conglomerate reservoirs, clarified the influence pathways of flow-reaction coupling on reservoir modification.

Mineral reactions exert bidirectional effects on reservoir modification, with related studies revealing their complex influence mechanisms. Hao Yongmao et al. [12] found that the alteration of plagioclase to kaolinite tends to degrade pore structure, significantly reducing reservoir permeability; this secondary mineral deposition particularly obstructs fluid flow in tight sandstones. Liu Li’s team [13], studying Illite/Smectite mixed-layer sandstone systems, pointed out that although dissolution of carbonate cements raises Ca2+ ion concentrations and temporarily improves pore connectivity, clay particle migration under fluid flow can induce pore-throat blockage, offsetting permeability gains. Wang Chen et al. [14] further revealed that pore blockage caused by asphaltene and CO2 reaction products significantly reduces effective pore connectivity, converting some pore space into inaccessible “dead pores,” thereby adversely affecting overall reservoir flow characteristics over the long term. Numerous studies have also deeply explored reservoir property changes induced by mineral reactions. Wegner et al. [15], through experimental studies of CO2–water–rock interactions in sandstone reservoirs, found that dissolution of carbonate minerals such as calcite and dolomite initially increases pore volume. Still, subsequent reprecipitation of secondary carbonate minerals may partially fill pores, affecting permeability stability. Shang et al. [16], investigating the long-term petrophysical evolution of tight reservoirs under CO2 exposure, noted that feldspar dissolution not only alters pore structure but also releases ions (e.g., K+, Na+) that influence formation water chemistry, indirectly promoting precipitation or dissolution of other minerals, exhibiting significant process sensitivity. Tang et al. [17] focused on clay mineral structural evolution under CO2 influence, discovering that illite and montmorillonite readily undergo crystal structure reorganization in acidic environments, forming new mineral phases; these changes can have dual impacts on reservoir mechanical properties and fluid permeability. Zhu et al. [18], through core flooding experiments under high temperature and pressure, systematically analyzed the dynamic balance between mineral dissolution and precipitation post-CO2 injection, revealing significant heterogeneity in mineral reaction impacts on reservoir porosity, especially in fractured and low-permeability zones. Ozório et al. [19] studied CO2 interactions with reservoir organic matter, finding that degradation products can couple with mineral reactions to exacerbate pore blockage, notably in reservoirs with high asphaltene content, where this effect poses a considerable negative impact on recovery. Based on these findings, it is evident that reservoir property evolution under CO2 exposure exhibits pronounced heterogeneity and process sensitivity. The bidirectional effects of mineral reactions vary significantly with geological conditions and timescales. Therefore, in practical applications of CO2-enhanced oil recovery and geological sequestration, comprehensive consideration of reservoir mineral composition, formation water chemistry, and reaction kinetics is essential to predict reservoir property changes accurately and to provide a scientific basis for optimizing injection strategies and ensuring long-term storage security.

Current research predominantly focuses on medium- to high-permeability reservoir systems, while the mechanisms of CO2–water–rock interactions and their dynamic impacts on the displacement and sequestration processes in tight sandstone reservoirs with more complex pore structures remain subject to three key knowledge gaps: (1) the kinetic characteristics of mineral reactions under extremely low-permeability conditions; (2) the regulatory mechanisms of temperature–pressure coupled fields on reaction pathways; and (3) the time-dependent effects of reservoir modification during long-term sequestration. To address these issues, this study concentrates on three critical scientific questions. First, calcite, acting as a “control valve” for mineral dissolution, significantly influences the dynamic evolution of reservoir pore structure by altering the pH and ionic composition of the pore fluid. However, the cross-scale coupling mechanisms linking its microscopic reaction pathways with macroscopic seepage characteristics remain unclear. Second, temperature and pressure exert dual regulatory effects on mineral dissolution kinetics, where temperature nonlinearly couples reaction rates and CO2 solubility through competitive influences; this complex mechanism urgently requires quantitative characterization models. Third, numerical simulations reveal significant spatiotemporal heterogeneity in mineralization-based sequestration. In the early injection stage (<30 years), calcite dissolution-driven ion release provides the material basis for secondary mineralization. In contrast, in the long term (>100 years), continuous dissolution of silicate minerals generates an alkaline environment that promotes exponential growth in CO2 mineralization rates. This dynamic process is crucial for evaluating the safety of long-term CO2 storage.

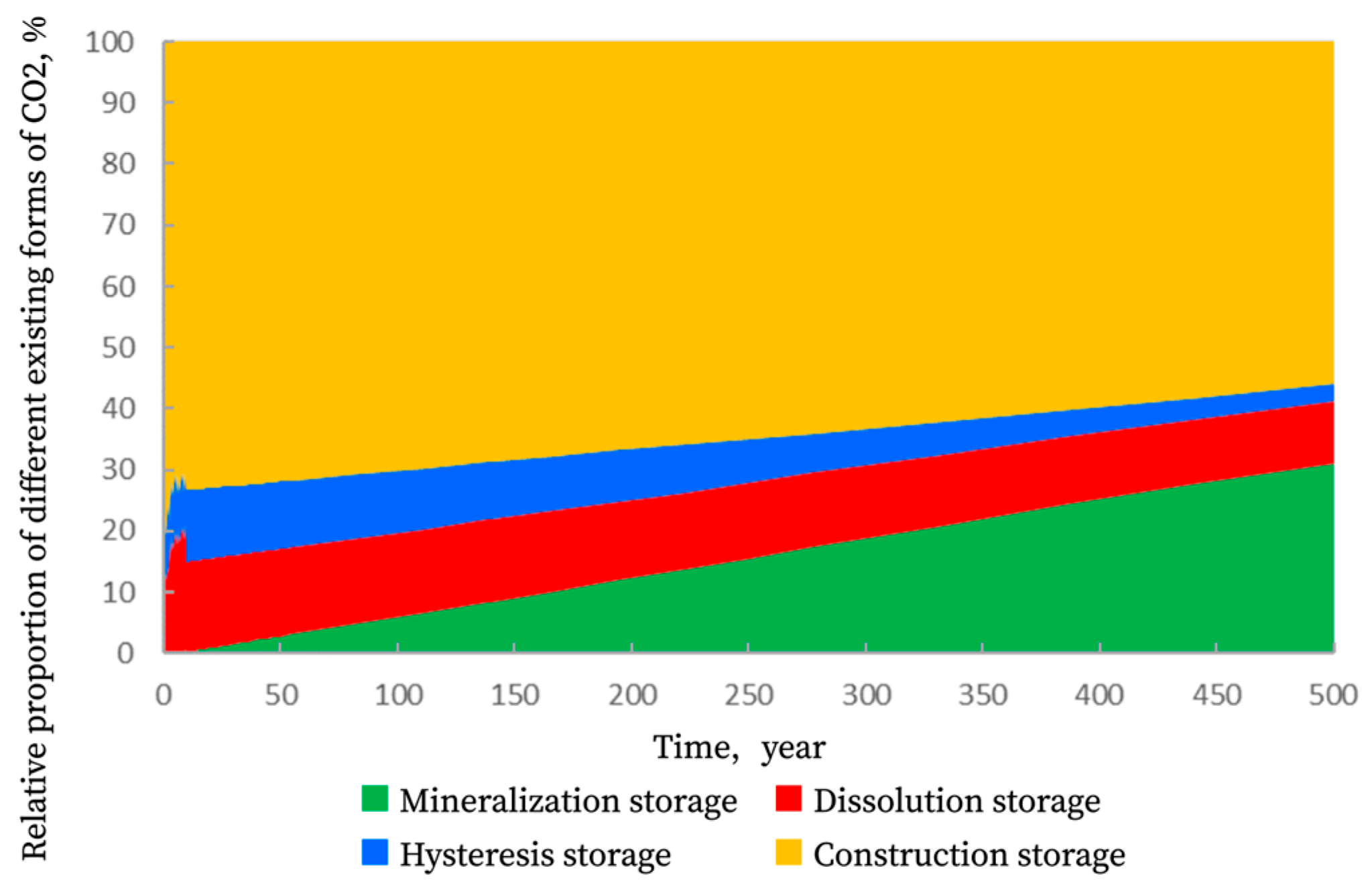

Focusing on the Changqing Jiyuan tight sandstone oil reservoir, this study addresses the aforementioned three key scientific questions through the following work: (1) Systematic experimental investigation: Static CO2–formation water–rock interaction experiments were conducted under various temperature and pressure conditions using high-temperature and high-pressure autoclaves. By employing a combination of modern analytical techniques, including ICP-OES, XRD, and SEM, the kinetic characteristics, dominant controlling factors of mineral reactions, and their mechanisms of microstructural alteration in tight sandstone were revealed. (2) Coupled numerical model development: Based on critical geochemical reaction parameters obtained from the experiments, a numerical simulation model coupling multiphase flow, relative permeability hysteresis, and geochemical reactions was established. This model can dynamically describe the effects of fluid–rock interactions on macroscopic reservoir properties such as porosity and permeability during CO2 enhanced oil recovery (EOR) and geological sequestration. (3) Integrated evaluation of EOR and sequestration: Utilizing the developed model, simulations of CO2 flooding performance and long-term (500 years) CO2 sequestration dynamics were performed. The contributions and temporal evolution of four sequestration mechanisms—structural trapping, dissolution trapping, residual trapping, and mineral trapping—were quantitatively analyzed, providing a theoretical foundation and data support for the integrated assessment of CO2-EOR and safe storage in tight oil reservoirs.

This paper adopts a combined approach of experimental study and numerical simulation to systematically investigate the interactions among CO2, formation water, and rock in tight sandstone reservoirs and their impacts. Static reaction experiments were conducted in high-temperature and high-pressure autoclaves, wherein pulverized tight sandstone core samples from Jiyuan oilfield were reacted with synthetic formation water at controlled temperatures (40–80 °C) and pressures (10–20 MPa). Periodic sampling was performed, and reaction products were analyzed using various analytical methods. Based on the experimental findings, an integrated numerical model was constructed to simulate the coupled process of CO2 flooding and sequestration, with the core functionality incorporating multiphase compositional flow, geochemical reactions, and dynamic changes in reservoir properties.

2. Experimental Preparation

2.1. Preparation of Sandstone and Formation Water Samples

Sandstone core samples from the Jiyuan Oilfield were first subjected to oil removal, followed by multiple-stage rinsing with ultrapure water to eliminate residual impurities. The cleaned samples were then placed in a vacuum drying oven at 30 °C for 24 h for dehydration. After drying, the rock samples were crushed using a ball mill and further ground with an agate mortar for fine processing. Particle size grading was performed using a 304 stainless steel standard sieve, and particles within the range of 0.075–0.6 mm were retained.

Based on the actual formation water analysis results from the Chang 8 reservoir section of the Jiyuan Oilfield (characterized as a calcium chloride-type water), an ion concentration calculation model was established using charge balance equations and mass conservation laws. This model was used to determine the molar concentrations of various dissolved components. Referring to the chemical composition ratios listed in Table 1, a simulated formation water system with equivalent physicochemical properties was prepared by mixing analytically pure reagents with deionized water.

Table 1.

Concentration of carious ion components in formation water.

Table 2 lists the mineral composition and petrophysical parameters of the target core samples.

Table 2.

Mineral composition and physical properties parameters of the target core.

2.2. CO2–Water–Rock Experimental Apparatus and Procedure

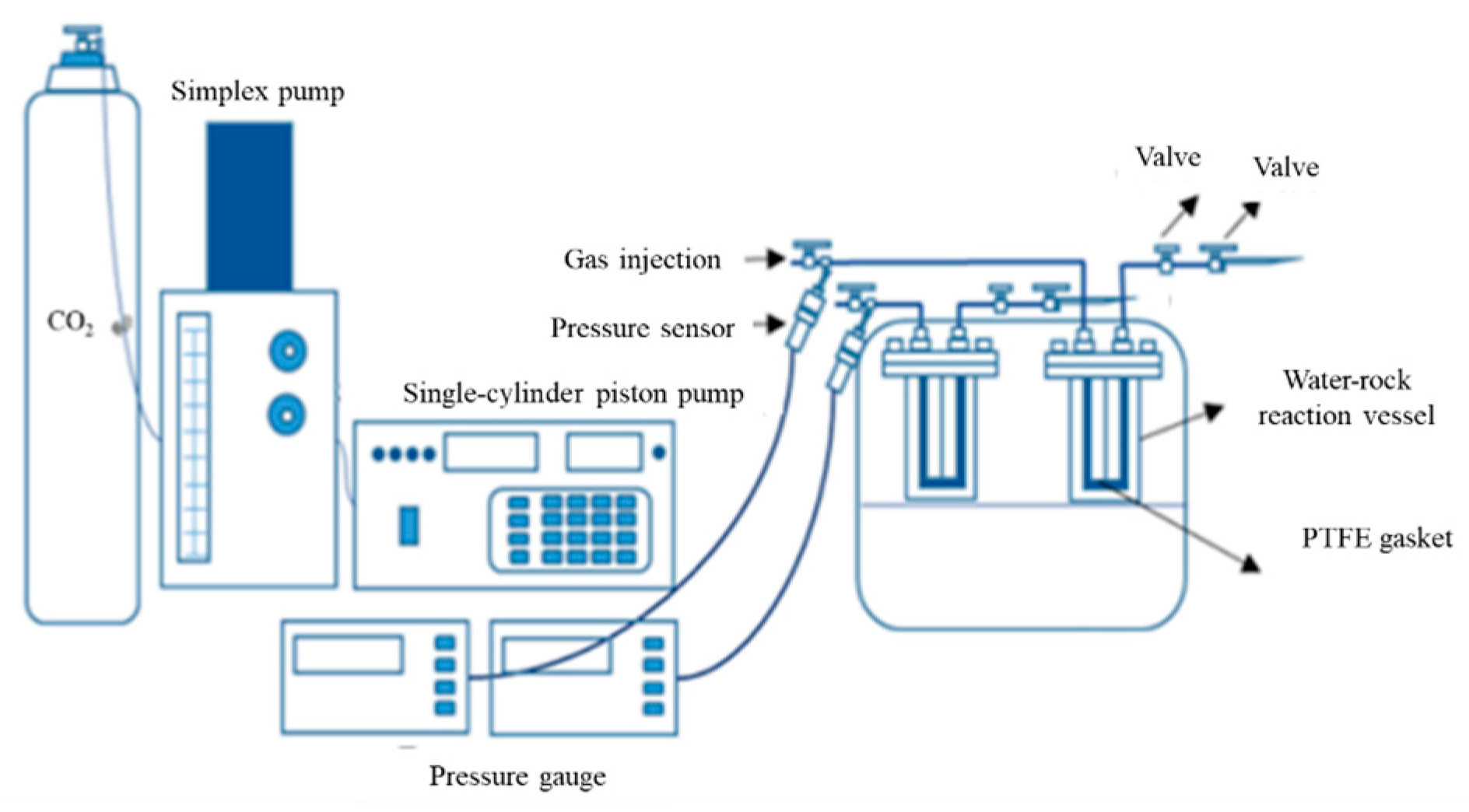

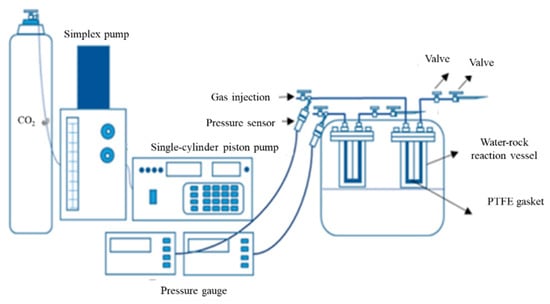

The experimental setup consists of a high-temperature and high-pressure reactor (operating temperature range: 20–150 °C, pressure range: 0–25 MPa), pressure sensors, a water bath heater (temperature range: 20–95 °C), a single-cylinder pump, a CO2 gas cylinder, and associated piping. A schematic diagram of the system components is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of static experimental setup for CO2–formation water–rock reactions.

Experimental Procedure for CO2–Formation Water–Sandstone Powder Interaction:

- (1)

- First, accurately weigh 1.0 g of sandstone powder with a particle size ranging from 0.075 to 0.6 mm.

- (2)

- Then, add the weighed sandstone powder and the prepared formation water solution into the reactor vessel at a ratio of 1 g sandstone powder to 20 mL formation water.

- (3)

- Seal the reactor, raise the temperature, and increase the pressure to the desired experimental conditions.

- (4)

- Once the temperature and pressure inside the reactor stabilize, record the start time of the reaction.

- (5)

- During the reaction, maintain stable temperature and pressure conditions throughout the experimental duration.

- (6)

- After the reaction completes, release the pressure from the reactor and retrieve the sample.

- (7)

- Filter the aqueous phase from the reactor, transfer it into centrifuge tubes, add 1–2 drops of approximately 2% nitric acid for acidification to prevent the precipitation of metal hydroxides and preserve the sample for analysis, then refrigerate and dilute the samples. Measure cation concentrations in the solution using inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES). Specifically, for each sample, prepare two parallel solutions diluted 10 times for the measurement of major elements K, Na, Ca, and Mg. Subsequently, take aliquots from these diluted solutions and dilute further by 25 times (i.e., 250 times total dilution relative to the original solution) to measure trace elements such as Al and Si. Four sets of tests are conducted under specific temperature, pressure, and time conditions to cover both major and trace element measurements in parallel. Calibration for major elements uses mixed standards of Na, K, Mg, and Ca, while trace elements are calibrated using mixed standards containing multiple trace elements. During measurement, sample injection intervals are controlled to avoid interference from high chloride concentrations.

- (8)

- Dry the powder samples, then analyze the mineralogical composition before and after reaction using X-ray diffraction (XRD), and characterize the rock surface micro-morphology by scanning electron microscopy (SEM). The procedure includes washing the samples three times with ultrapure water at a ratio of 1 g powder to 40 mL water. After discarding the wash water, place the wet solids in a vacuum drying oven at 40 °C for approximately 2 days to ensure complete drying of the sandstone powder. After drying, grind approximately 0.5 g of the sample in an agate mortar to pass through a 200-mesh sieve. During XRD testing, use a copper target as the X-ray source at 30 kV and 10 mA. The scanning angle range is set from 5° to 70°, covering the main diffraction peaks of the minerals, with a step size of 0.02°.

3. Experimental Results and Analysis

3.1. Analysis of ICP-OES Results

3.1.1. Changes and Reactions of Major Elements

In the solution, the main cationic elements include Na+, Ca2+, K+, and Mg2+, among which the variation of Ca2+ concentration is the most significant, primarily reflecting the dissolution of calcite. This phenomenon indicates that CO2 injection leads to a decrease in pH, causing calcite dissolution. The primary reaction process is as follows: first, CO2 reacts with H2O to form carbonic acid, represented by the equation CO2 + H2O ⇌ H2CO3; then, carbonic acid dissociates into bicarbonate and hydrogen ions, H2CO3 ⇌ H+ + HCO3−; finally, the release of H+ increases the acidity of the fluid, triggering the decomposition of carbonate minerals in the rock and releasing metal cations, represented by CaCO3 (calcite) + H+ → Ca2+ + HCO3−.

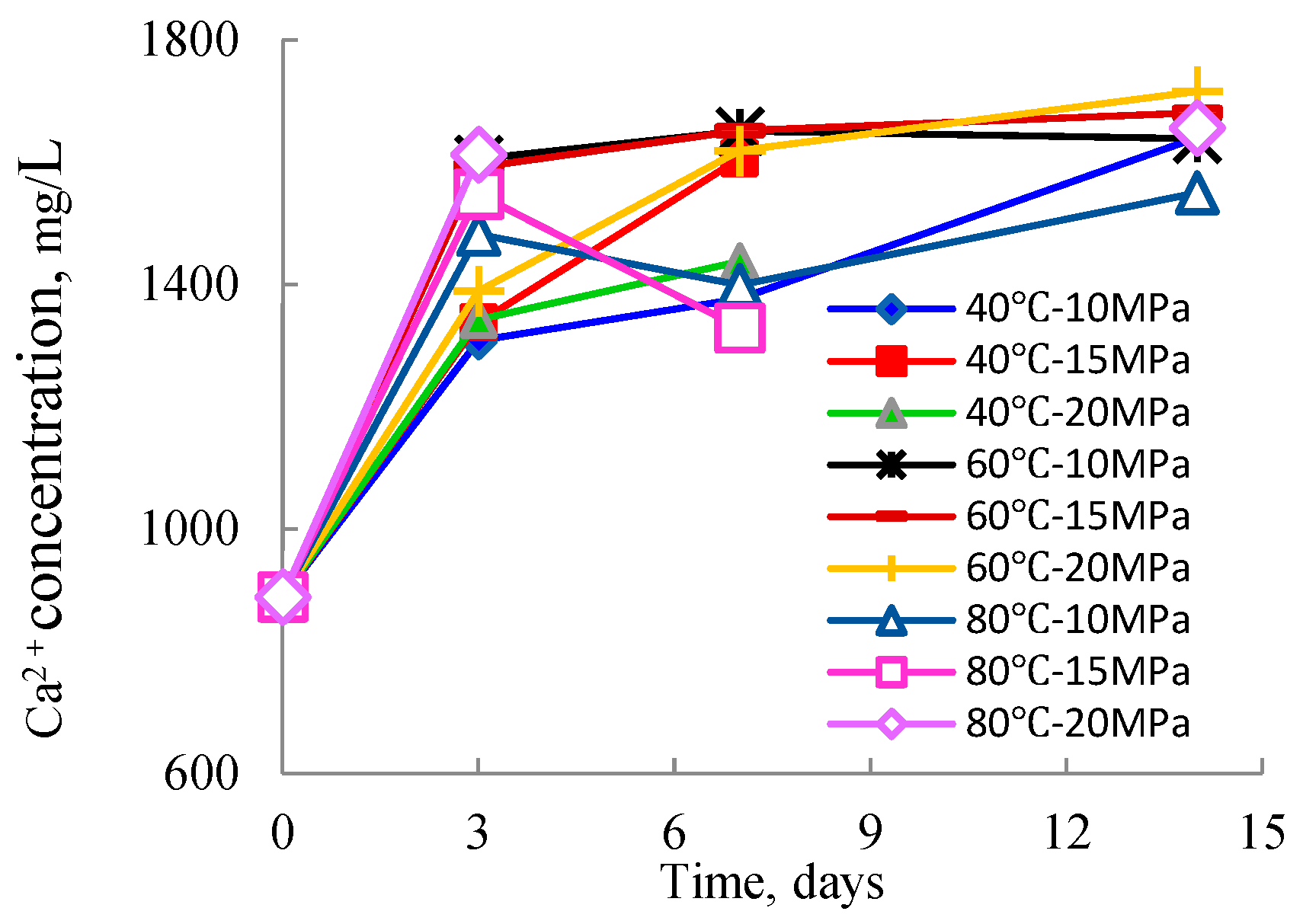

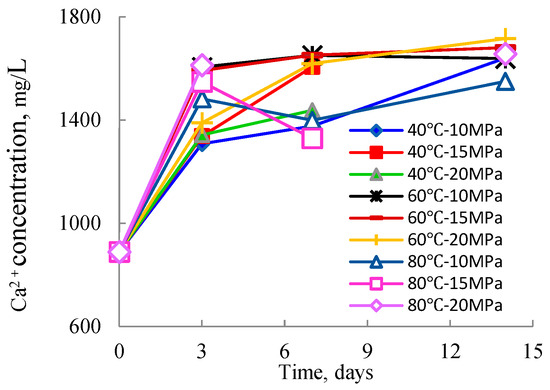

During the first three days of the experiment, the dissolution rate of calcite was relatively fast, especially under high temperature conditions, and it nearly reached dissolution equilibrium rapidly. Under other experimental conditions, the Ca2+ concentration increased slowly afterward and eventually reached equilibrium as well (see Figure 2). Temperature has a significant effect on the dissolution rate and the pH after CO2 dissolution; higher temperatures accelerate the reaction rate. Overall, the dissolution rate was fastest at 60 °C and slowest at 40 °C. Under all conditions, once dissolution equilibrium was reached, the Ca2+ concentration remained basically the same and no further changes occurred (i.e., the Ca2+ concentration curve stabilized in the later stage of the experiment, indicating that the Ca2+ in the solution had approached saturation).

Figure 2.

Variation in Ca2+ concentration over time under different conditions.

Since the dissolution reaction occurs in the liquid phase, the effect of pressure on the reaction is significantly less pronounced than that of temperature. Temperature variations notably influence the calcite dissolution process, as shown in Figure 2. Under 40 °C conditions, the concentration of Ca2+ is lower than at 60 °C and 80 °C, and the time to reach equilibrium is slower. At a low pressure of 10 MPa, the highest Ca2+ concentration and the fastest equilibrium are observed at 60 °C; whereas at a higher pressure of 20 MPa, the highest Ca2+ concentration and fastest equilibrium occur at 80 °C.

Different pressure conditions also exhibit varying effects on the equilibrium of the calcite dissolution reaction. At the low temperature of 40 °C, pressure has little influence on the reaction; at 60 °C, however, equilibrium is reached slowest under the high pressure of 20 MPa. Conversely, under 80 °C conditions, the equilibrium at 20 MPa is achieved the fastest.

3.1.2. Changes in Al and Si Concentrations and Their Reactions

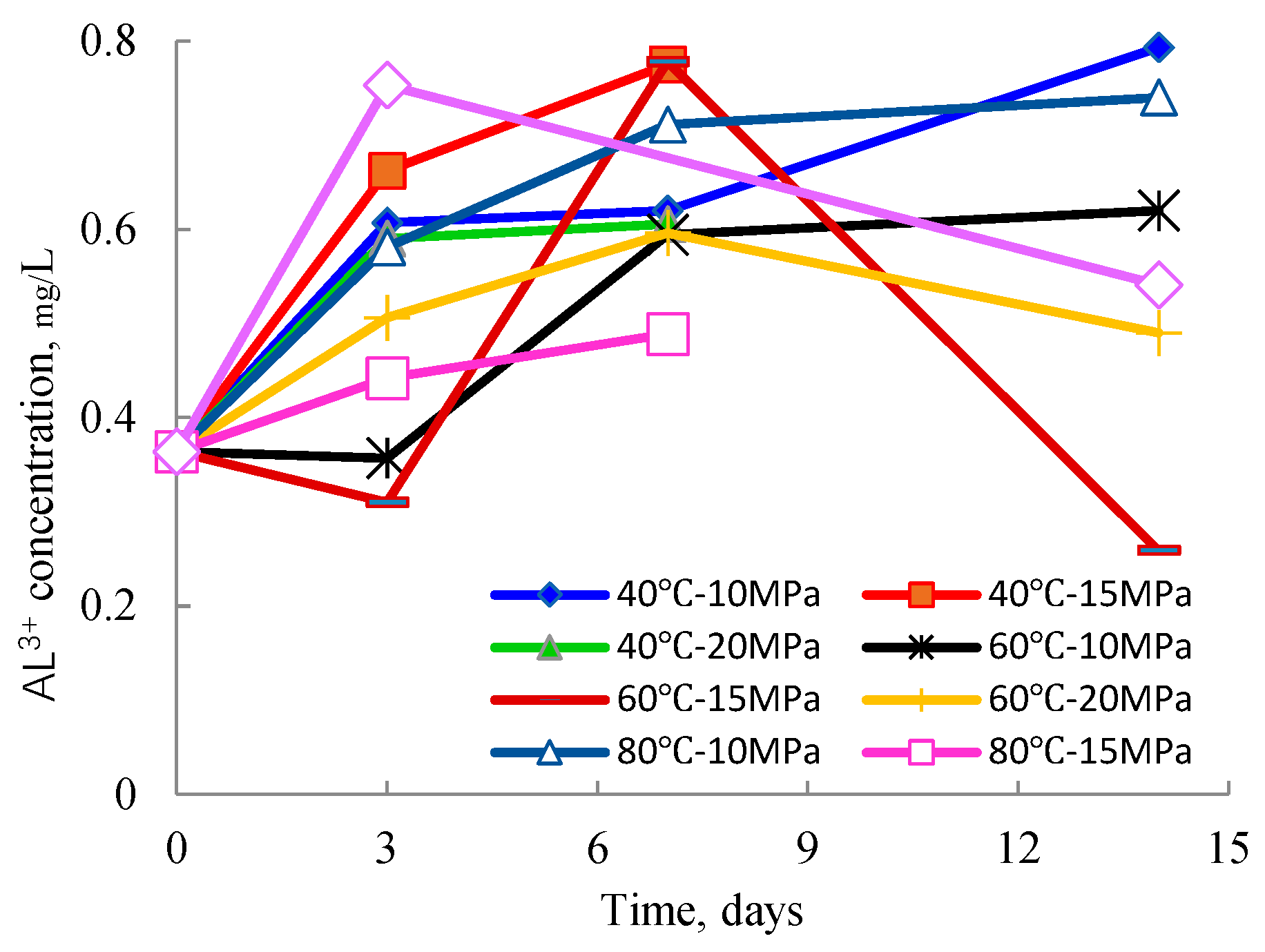

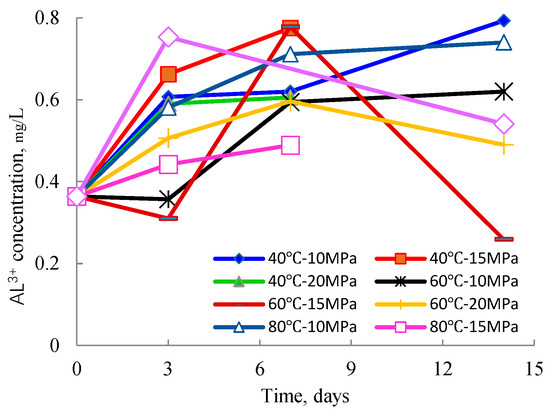

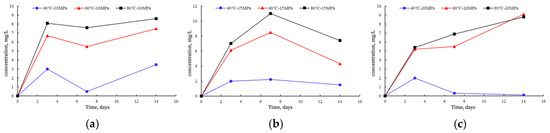

The dissolution of albite (sodium feldspar) occurs under acidic conditions, where the lowered pH environment promotes the dissolution reaction. The specific reaction can be expressed as: NaAlSi3O8 (albite) + 4H+ + 4H2O → Na+ + Al3+ + 3H4SiO4. Subsequently, H4SiO4 decomposes into SiO2 and H2O. Over time, the concentration of Al3+ initially increases and then stabilizes, indicating it is influenced by the equilibrium established in the calcite system. As the solution pH gradually stabilizes, the dissolution of feldspar ceases. Figure 3 shows that the concentration change of Al3+ during the reaction is minimal (<1 ppm), suggesting that in this experiment, albite and other aluminosilicate minerals remain relatively stable and exhibit insignificant dissolution.

Figure 3.

Variation in Al3+ concentration with reaction time under different temperature and pressure conditions.

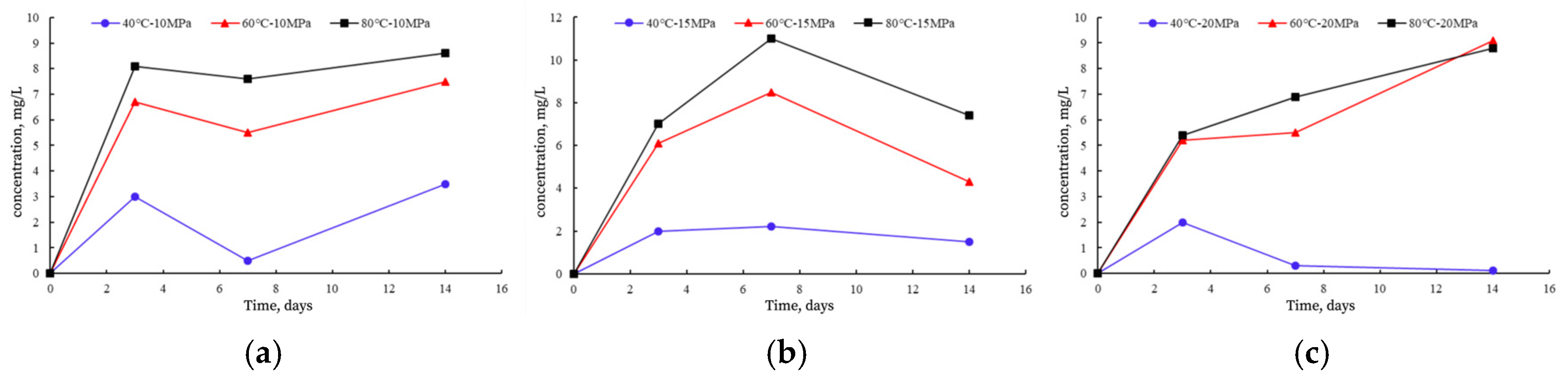

The reaction temperature has a significant impact on the concentration of Si. As shown in Figure 4a, under low-pressure conditions (10 MPa), higher temperatures correspond to faster Si dissolution rates and higher equilibrium concentrations; notably, dissolution is slower at the low temperature of 40 °C. Comparing Figure 4a–c, it can be seen that under high-pressure conditions (20 MPa), the dissolution level at 60 °C is comparable to that at 80 °C. The changes in Si concentration result from the interplay between the dissolution of quartz and feldspar and the precipitation of secondary silicates. Over time, Si concentration in the solution rapidly increases initially due to the quick dissolution of feldspar and quartz; subsequently, as secondary SiO2 gradually forms and precipitates, some of the dissolved silica is consumed, causing the Si concentration to approach a dynamic equilibrium or even decrease. Additionally, silicic acid exists in multiple dissociated and polymerized forms in aqueous solution, leading to some instability in Si concentration. Temperature has a pronounced effect on this process, with higher temperatures accelerating dissolution rates and maintaining higher Si concentrations, whereas lower temperatures slow dissolution, resulting in comparatively lower Si concentrations. In contrast, pressure has a weaker influence on Si concentration, indicating that temperature is the key controlling factor for Si dissolution and release. Overall, Si concentration shows a trend of initially increasing and then stabilizing over time, reflecting the dynamic balance between dissolution and precipitation reactions (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Influence of different reaction pressures and temperatures on the concentration of the Si element: (a) 10MPa, (b) 15MPa, (c) 20MPa.

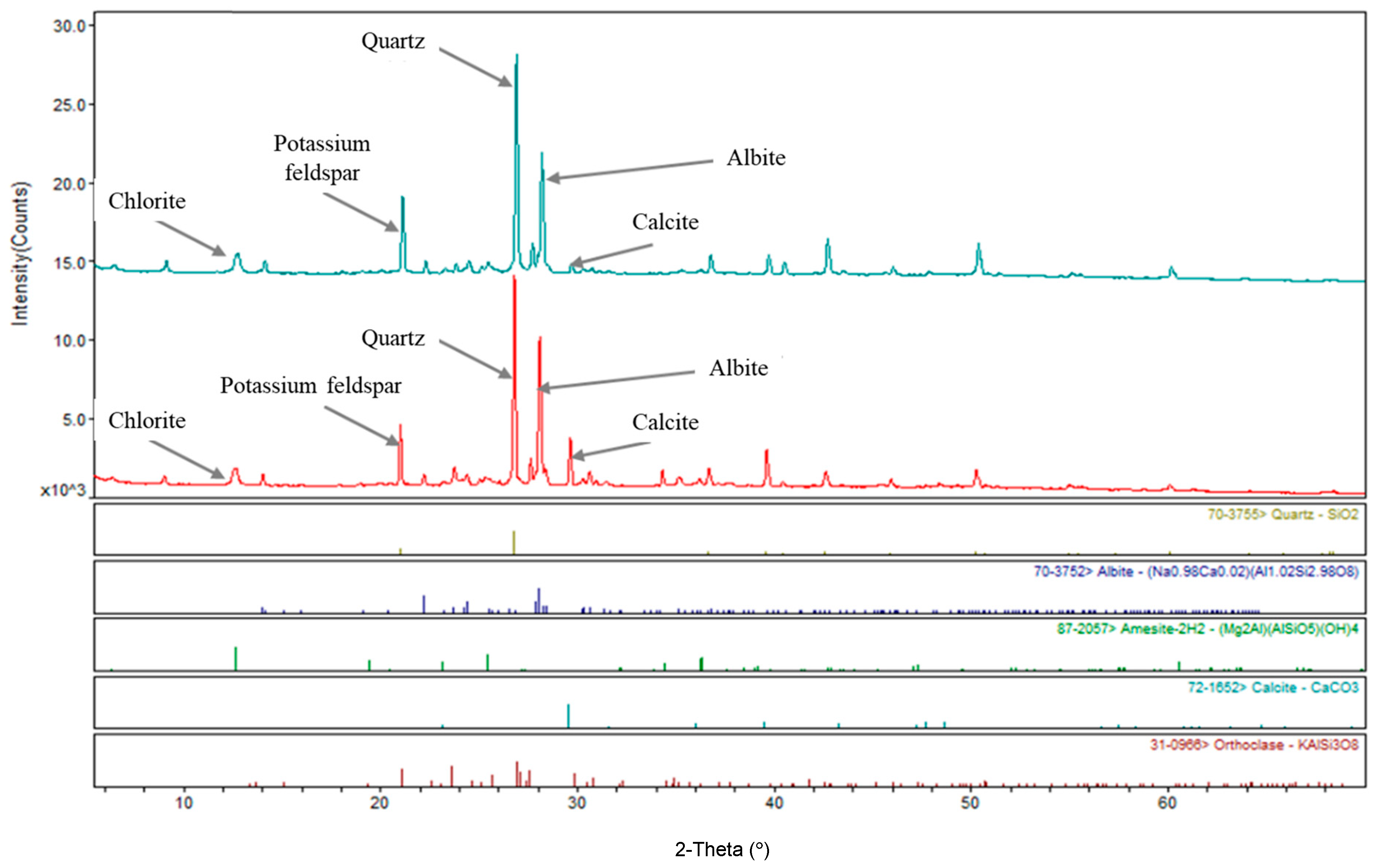

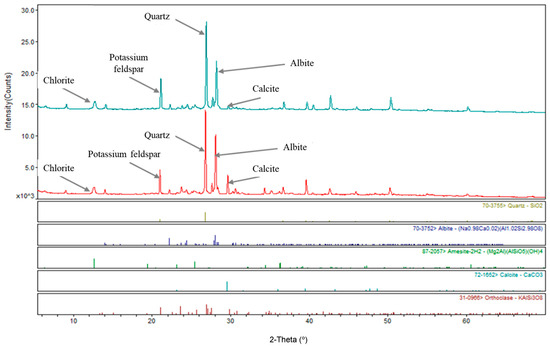

3.2. Powder X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) Analysis

XRD tests were conducted on rock samples before and after the reaction. The results (see Figure 5) indicate that the overall mineral types did not change significantly. However, the dissolution of carbonate minerals such as calcite was quite pronounced after the reaction, with its characteristic diffraction peaks being almost completely eliminated, consistent with the previously discussed ICP data. In addition, compared to the pre-reaction samples, the quartz content showed a slight increase, and some transformation among feldspar minerals was observed. During the reaction, sodium feldspar underwent partial dissolution and was partly transformed into minor amounts of potassium feldspar, transitional feldspar minerals, and carbonate minerals. It is noteworthy that clay minerals such as chlorite exhibited no significant changes, with only minor variations in diffraction peak intensity.

Figure 5.

Whole-rock XRD characteristic analysis of core inlet section before and after displacement reaction.

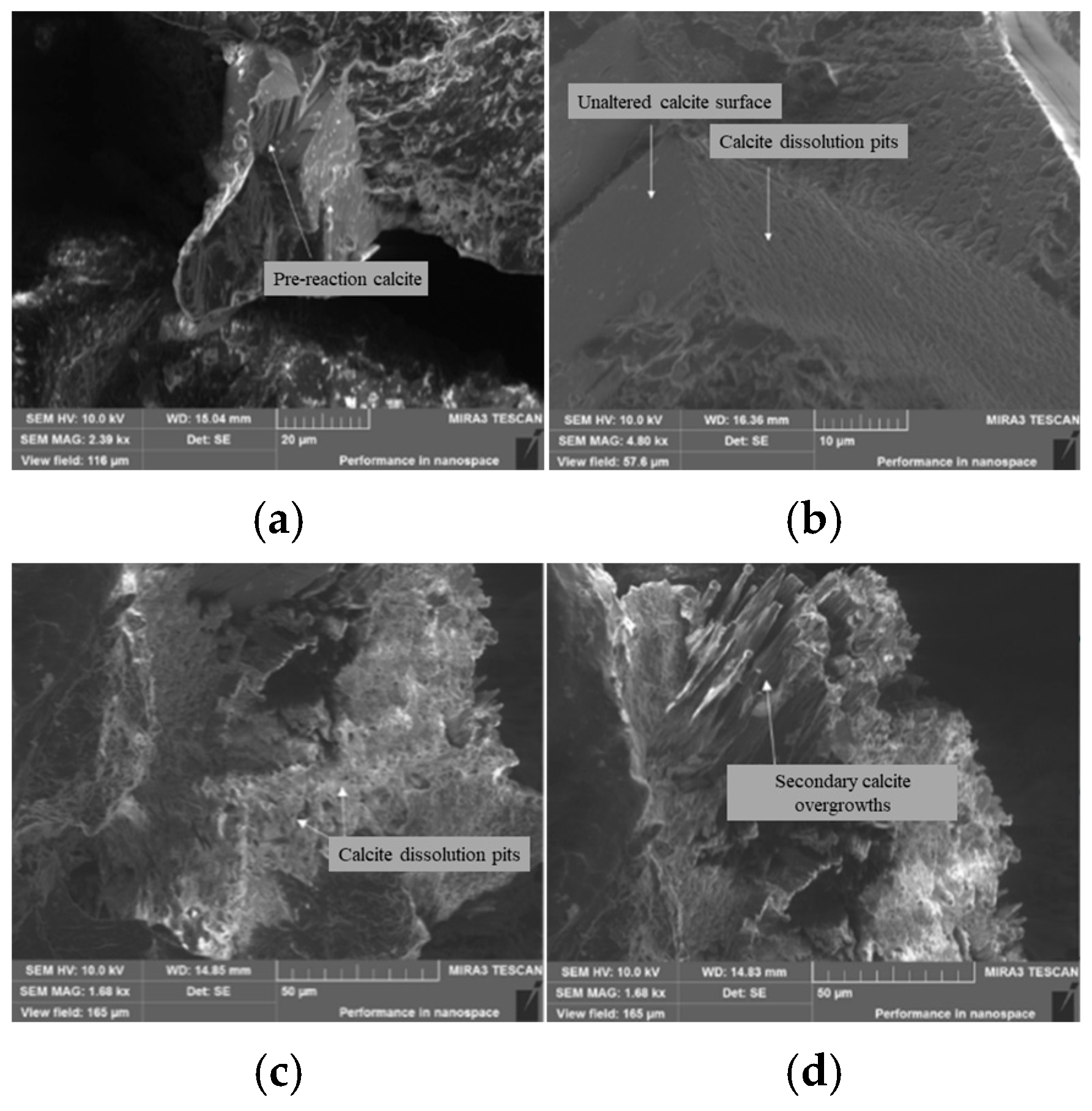

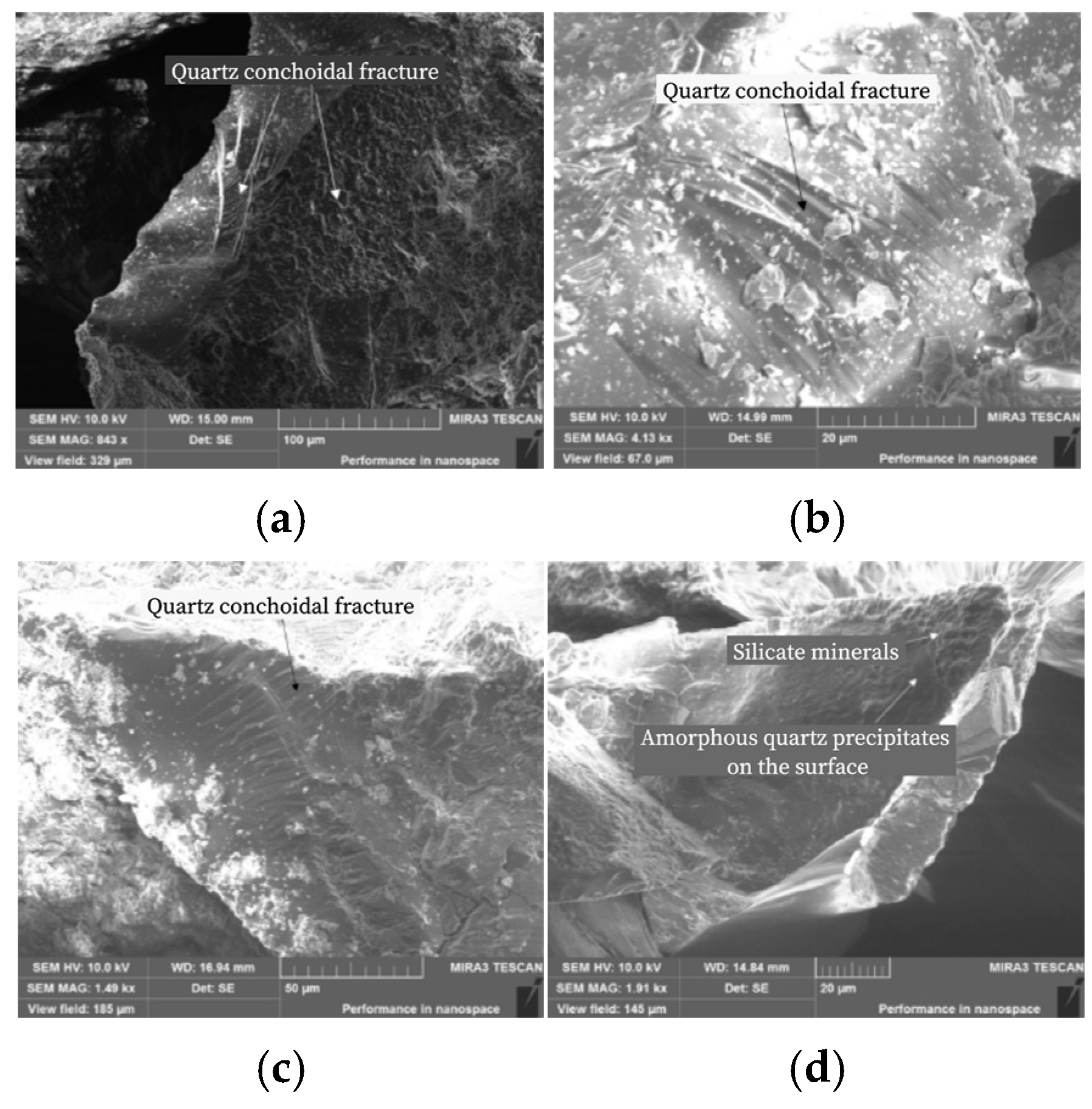

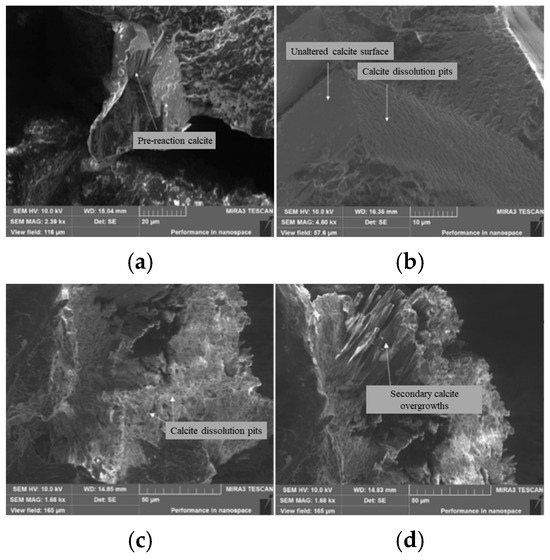

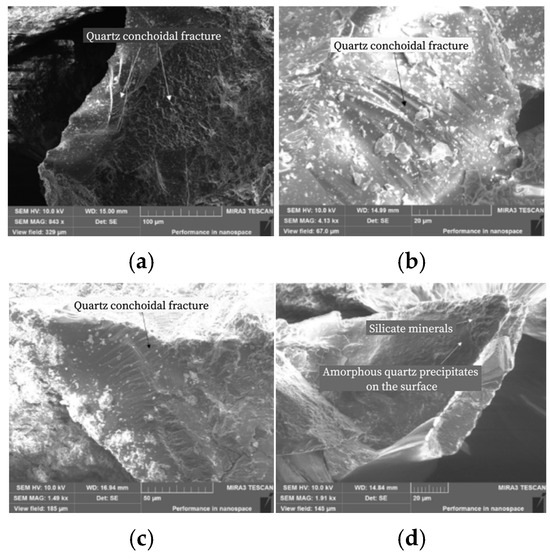

3.3. Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) Analysis

Observations from the scanning electron microscope reveal that, in addition to undergoing primary dissolution, qualitative evidence from SEM micrographs suggests the formation of secondary calcite (see Figure 6d). While the total volume of this reprecipitation was too small for accurate quantification via bulk XRD analysis, its localized presence on mineral surfaces indicates that the system was approaching a dynamic equilibrium involving both dissolution and precipitation. Under low-temperature conditions, quartz showed no significant dissolution; however, at higher temperatures, secondary quartz growth was observed (see Figure 7). This finding supports the inference of secondary quartz growth made from the XRD data. The experiments indicate that, beyond the main reactions, several secondary processes occur, influenced collectively by temperature, pressure, and other conditions. The simultaneous occurrence of dissolution and secondary precipitation of similar minerals highlights the complexity of these interactions.

Figure 6.

Surface morphology of calcite before and after reaction: (a) before reaction, (b) after reaction, (c) react at 40 °C and 10 MPa for 14 days, (d) react at 80 °C and 10 MPa for 14 days.

Figure 7.

Surface morphology of quartz before and after reaction: (a) before reaction, (b) after reaction, (c) react at 40 °C and 20 MPa for 14 days, (d) react at 80 °C and 20 MPa for 14 days.

Through ICP-OES elemental analysis, powder X-ray diffraction, and scanning electron microscopy, the mechanisms and influencing factors of water–rock reactions during CO2 sequestration were investigated. These experimental data provided essential baseline parameters for numerical modeling, including reaction kinetic parameters, initial mineral contents, and characteristics of reaction products. Furthermore, the observed features of water–rock interactions and the conclusion that calcite dissolution serves as the controlling reaction help validate and calibrate the numerical model. It is important to note that these static batch experiments, conducted on powdered samples to obtain intrinsic kinetic data, represent an idealized system. The upscaling of these findings to dynamic, field-scale conditions, where fluid flow and pore structure limit reaction rates, is addressed in the subsequent numerical simulation section. It was also found that water–rock reactions lead to a reduction in the permeability of natural fractures near the injection well, which is critical for guiding the dynamic update of permeability in the model as reactions progress. Experimental studies on the mineralization process revealed an increasing trend in the amount of mineralized CO2 over time, offering a foundation for long-term predictions in numerical simulations.

4. Coupled Numerical Simulation of CO2 EOR and Sequestration

4.1. Water–Rock Reaction Mechanism

To upscale the kinetic insights gained from the static batch experiments to dynamic reservoir conditions, a comprehensive numerical simulation model was developed. Based on the previously established water–rock reaction mechanisms and the reservoir characteristics of the Jiyuan tight oil reservoir, a comprehensive numerical simulation model was developed. This model simultaneously incorporates the effects of CO2 EOR, capillary pressure hysteresis, and water–rock reactions. The purpose of the model is to analyze the impact of water–rock interactions on both CO2 EOR performance and its subsequent long-term sequestration.

Henry’s law is used within the model to calculate the solubility of CO2 in formation water [20]. It is assumed that aqueous-phase reactions reach instantaneous equilibrium, whereas mineral reactions, due to their slower kinetics, are described by kinetic partial equilibrium equations. Based on previous experimental results of water–rock interactions, the model primarily focuses on the following reaction processes:

CO2 (g) ⇌ CO2 (aq),

CO2 (aq) + H2O ⇌ H2CO3,

H2CO3 ⇌ H+ + HCO3,

HCO3− ⇌ H+ + CO32−,

Meanwhile, partial minerals in the rock further undergo the following dissolution reactions:

CaCO3 + H+ ⇌ Ca2+ + HCO3−,

2NaAlSi3O8 + 2H+ + 9H2O ⇌ Al2Si2O5(OH)4 + 2Na+ + 4H4SiO4,

CaAl2Si2O8 + 2H+ + H2O ⇌ Al2Si2O5(OH)4 + Ca2+ + 2H4SiO4,

SiO2 + 4H+ ⇌ Si4+ + 2H2O,

4.2. CO2 Geochemical Reaction Model

The kinetic parameters for the mineral reactions (e.g., activation energy, pre-exponential factor) listed in Table 3 are derived from established geochemical literature. The role of our laboratory ICP-OES experiments was to validate this model and calibrate it for the specific mineralogy of the Jiyuan Oilfield. By comparing the simulated short-term ion concentration trends with our measured Ca2+ and Si data, we confirmed that the chosen kinetic framework could plausibly reproduce the observed reaction rates, thereby providing confidence in its application for long-term forecasting.

Table 3.

Various Ionic components concentration in formation water.

In the model, it is assumed that aqueous phase reactions rapidly reach equilibrium, whereas mineral reactions proceed at slower rates and are thus described using kinetic partial equilibrium equations. The aqueous phase reaction equations are given as follows [9]:

where

where aj represents the ion size parameter of ion j, indicating the effective diameter or hydrated radius of the ion in solution, reflecting the spatial occupation of the ion in the medium; zj is the charge number of ion j; Qa denotes the ion activity product of aqueous phase reaction a; I is the ionic strength; Keq,a is the chemical equilibrium constant of aqueous phase reaction a; Cjw represents the concentration of ion j in the aqueous phase; vja is the stoichiometric coefficient of ion j in aqueous phase reaction a; naq is the number of ions involved in aqueous phase reaction a; γj denotes the ion activity coefficient; Ay, By, and BI are temperature-dependent parameters; I is the ionic strength.

The mineral reaction equation is expressed as follows:

where N0,β is the amount of substance of mineral β in a unit volume of rock at the initial moment; Qβ is the ion activity product for mineral reaction β, calculated in the same way as for aqueous phase reactions; Keq,β is the chemical equilibrium constant for mineral reaction β; K0,β is the rate constant at the reference temperature T0; rβ is the dissolution/precipitation reaction rate of mineral β; Eβ is the activation energy of mineral reaction β; T is the actual reservoir temperature; A0 is the initial reactive surface area of mineral β; A is the reactive surface area of mineral β per unit volume of rock at the current time, which changes dynamically with mineral dissolution or precipitation; Kβ is the reaction rate constant for mineral reaction β; Nβ is the current amount of mineral β per unit volume of rock.

4.3. Porosity-Permeability Mode

Mineral dissolution and precipitation caused by CO2 mineralization reactions, along with changes in reservoir pressure, lead to variations in reservoir porosity and permeability. The method for calculating the impact of geochemical reactions on reservoir porosity is detailed in reference [21]. The effect of geochemical reactions on reservoir porosity is expressed as:

The relationship between reservoir porosity and permeability can be described by the Kozeny–Carman equation [21,22]. This model was selected because it provides a widely accepted, physically based framework for relating permeability changes to the evolution of porosity, which is essential for simulating the effects of mineral dissolution and precipitation. While core-specific empirical correlations can also be used, the Kozeny–Carman model offers a more generalized and robust approach for reactive transport modeling.

where ϕ is the current reservoir porosity; ϕ0 is the initial porosity; ρβ is the molar concentration of mineral β; cϕ is rock compression coefficient; p is the reservoir pressure; p0 is the reference pressure; k is the current reservoir permeability; k0 is the initial permeability; n is the empirical exponent, generally taken as an integer; Rmn denotes the number of mineral reactions considered.

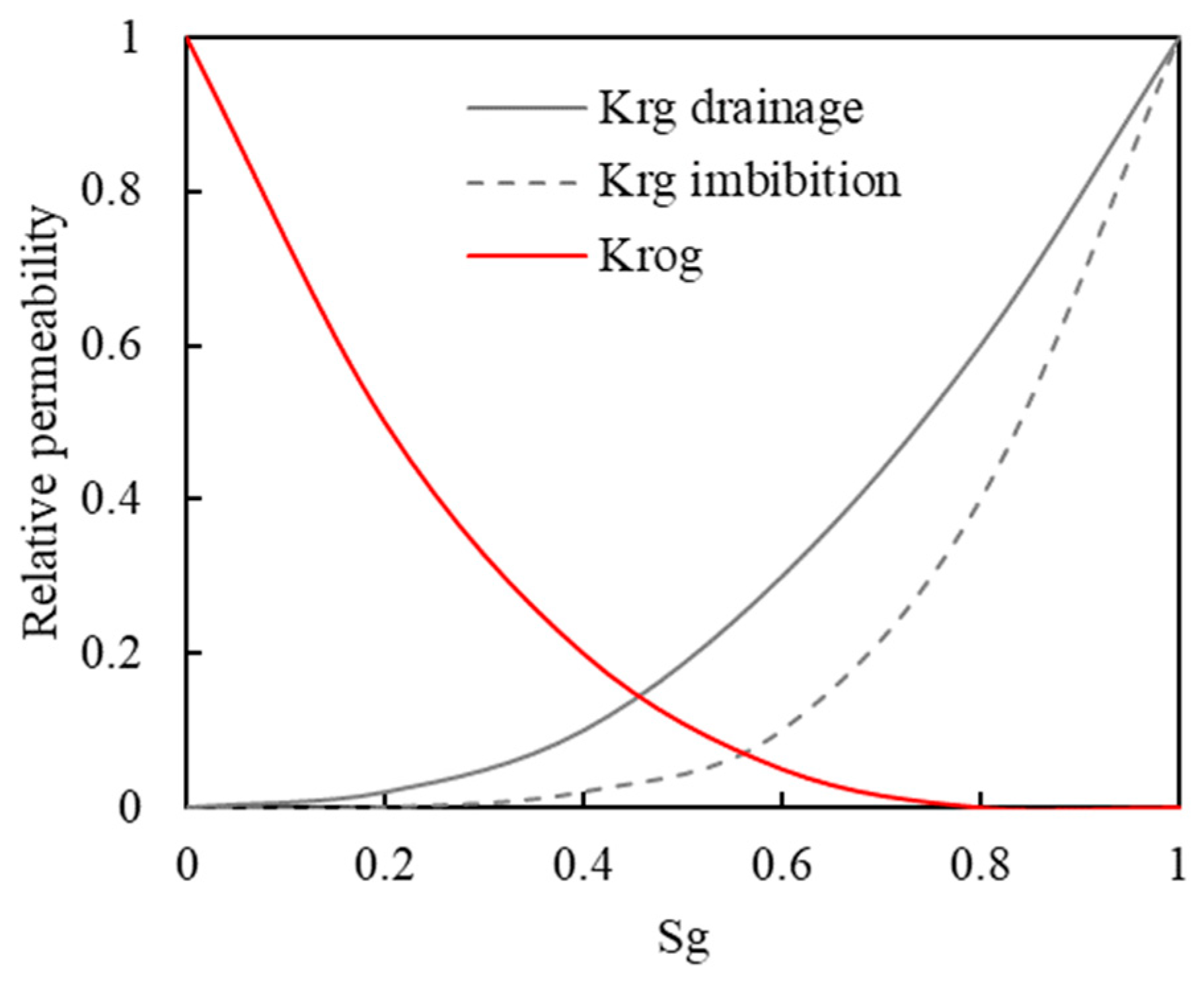

4.4. Relative Permeability Hysteresis Model

Given that the target reservoir is of tight lithology, the strong capillary forces play a significant role. Under the action of capillary forces, the liquid–gas interfaces within the reservoir pores develop interfacial tension. This tension restricts the free movement of CO2 in the pore space, causing it to become trapped in micro-pores or fractures—a phenomenon known as capillary trapping. Furthermore, during CO2 injection and migration, the complexity of the pore structure and the fluid dynamic characteristics lead to flow hysteresis. In other words, the migration rate of CO2 is slowed by pore resistance, interfacial tension between phases, and viscosity differences between fluids, resulting in a portion of CO2 remaining trapped in the reservoir. The combined effect of capillary trapping and flow hysteresis allows the injected CO2 to be effectively stored within the pore space of the reservoir, achieving long-term sequestration.

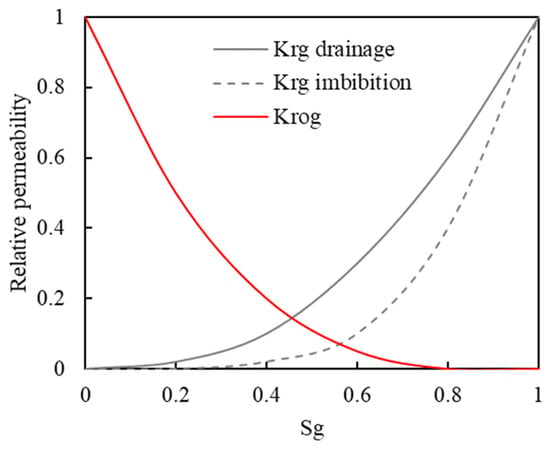

Based on field test results, the relative permeability curves for gas-phase displacement and imbibition need to be defined separately, as shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Consider the relative permeability curve with gas phase hysteresis.

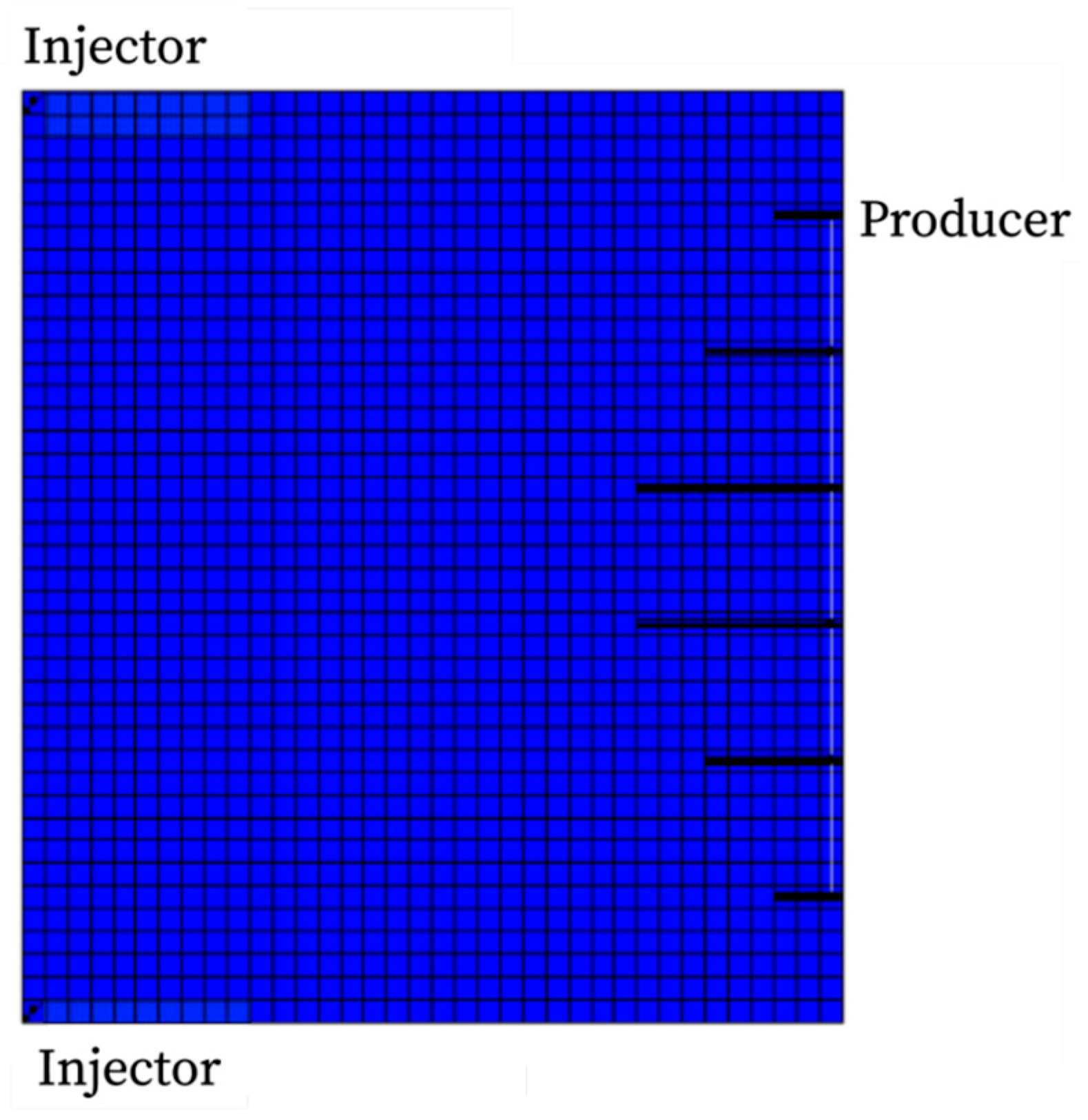

4.5. Field Model Application

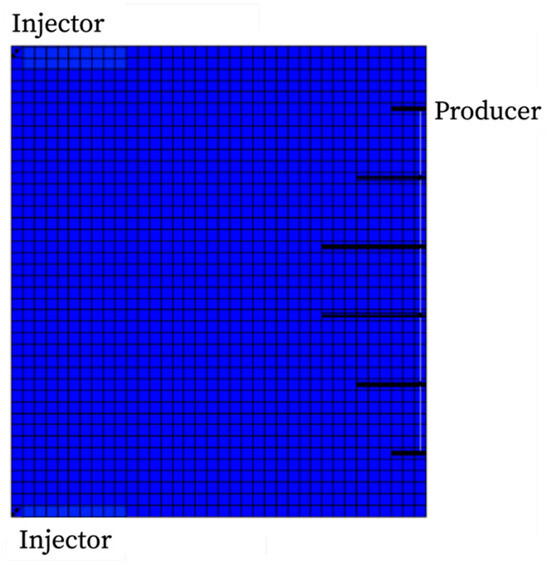

The model employs a configuration with two vertical wells for CO2 injection and a multistage fractured horizontal well for oil production, where the fractured horizontal well is simulated using a locally refined grid with a conductivity of 30 Dc·cm. The model dimensions are 520 × 820 × 10 m with a grid of 26 × 41 × 1 in Figure 9. A Warren–Root dual-porosity model is adopted, with the fracture system having a porosity of 0.2% and a permeability of 10 mD, and the matrix system having a porosity of 10% and a permeability of 0.05 mD. The initial oil saturation of the reservoir is 50%, with an initial pressure of 17 MPa and a temperature of 65 °C. The Peng–Robinson equation of state combined with a two-phase flash calculation method is used to determine oil–gas phase equilibrium in the model. During simulation, the CO2 injection rate is 5 t/d per well, with a water injection rate of 10 t/d during water–gas alternating injection. The oil displacement stage lasts for 10 years, followed by one year of continuous CO2 injection, with the total simulation period extending to 500 years.

Figure 9.

Typical model of a schematic diagram.

The crude oil in the Chang 812 sublayer of the Jiyuan Oilfield has a viscosity of 2.2 cp and a density of 0.782 g/cm3. In the simulation, the crude oil is divided into nine pseudo-components, with the composition and thermodynamic parameters of each component obtained through phase behavior matching; the molar contents and related parameters of these components are presented in Table 4. Considering the complexity of water–rock interactions, three representative minerals are included in the simulation: calcite, kaolinite, and feldspar, with initial volume fractions of 0.0025, 0.0008, and 0.007, respectively. The corresponding reaction equilibrium constants are taken as classical values, and the kinetic parameters for the reactions are provided in Table 3.

Table 4.

Crude oil composition and thermodynamic parameters of each pseudo-component.

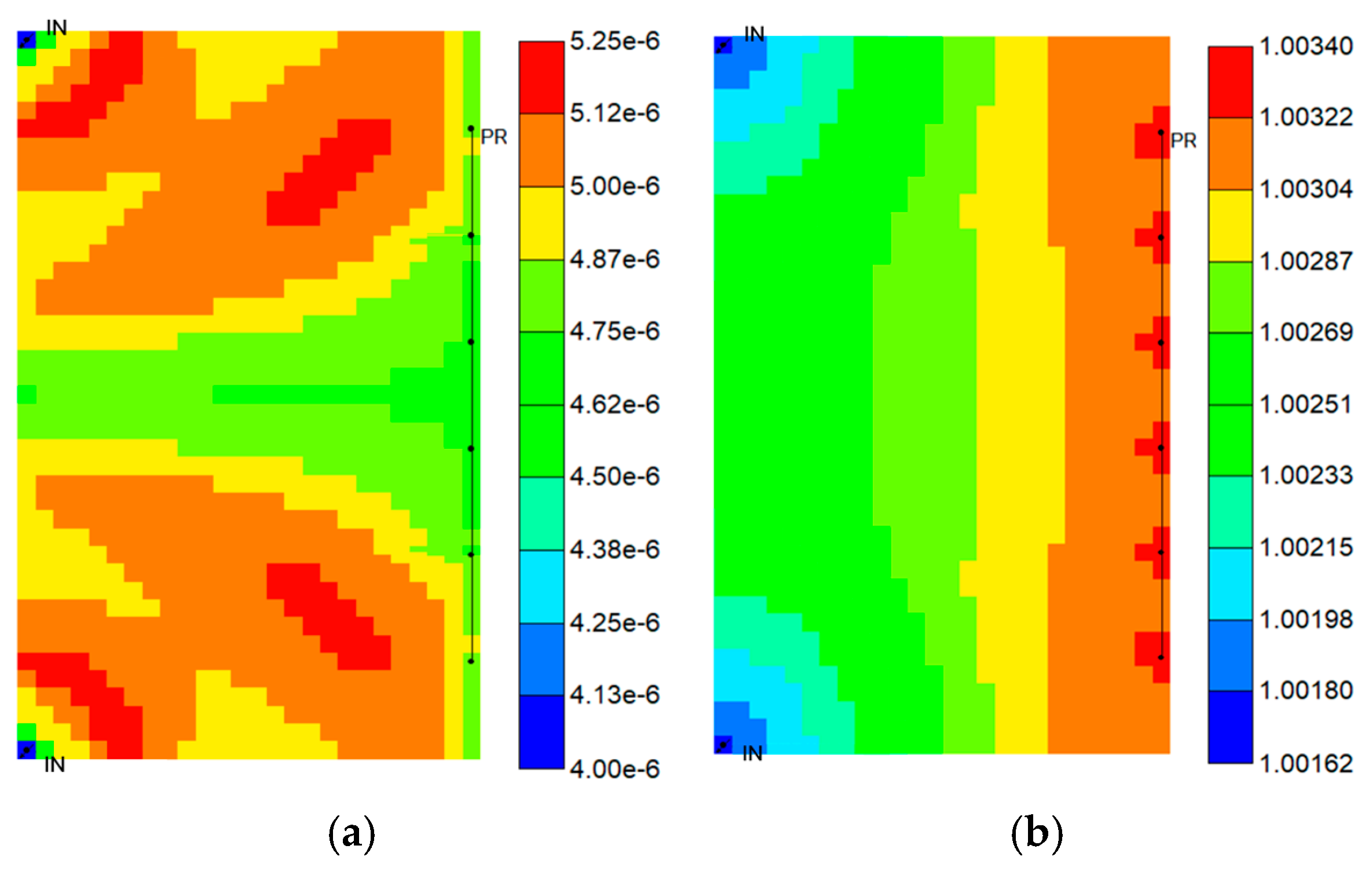

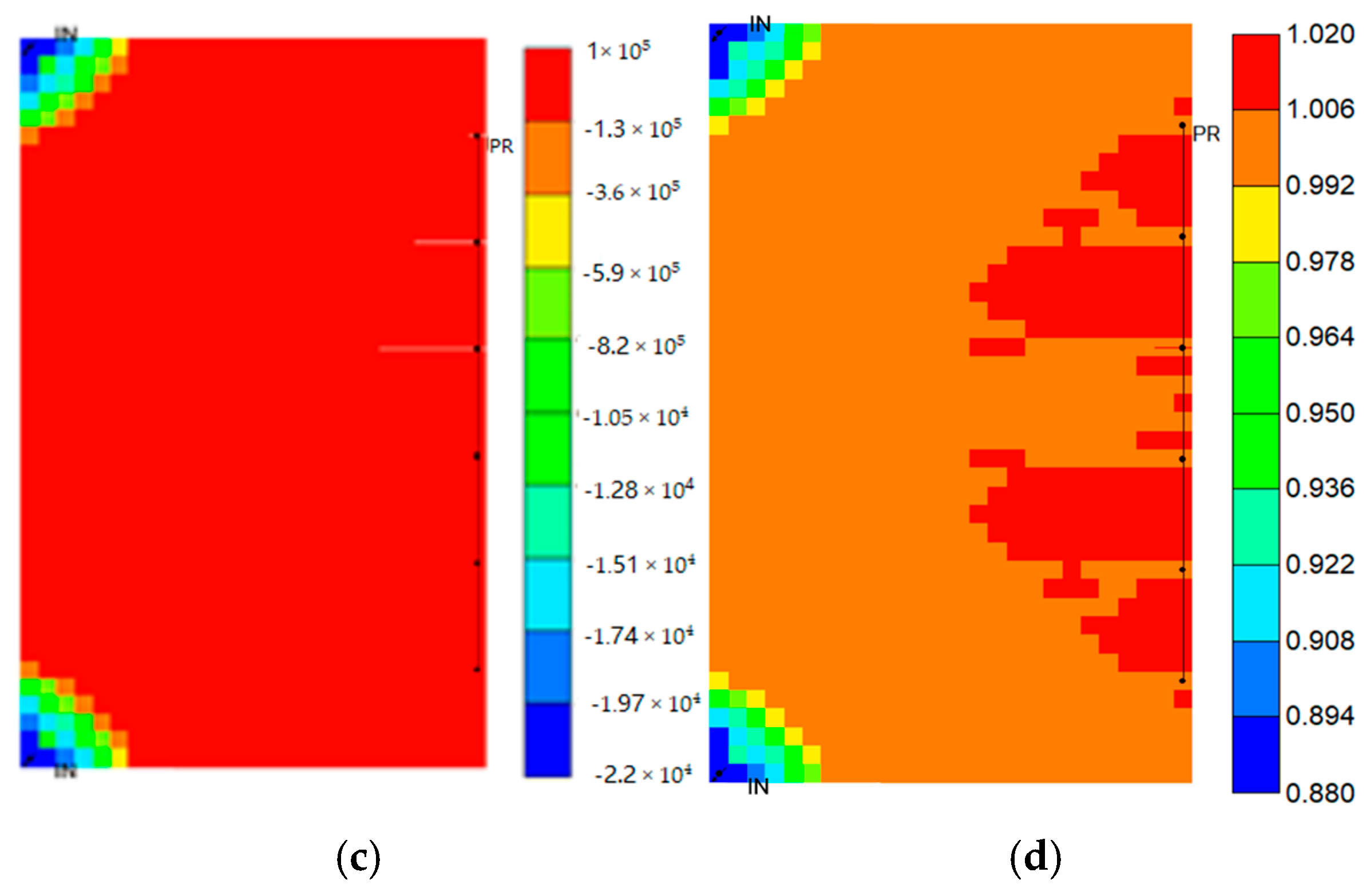

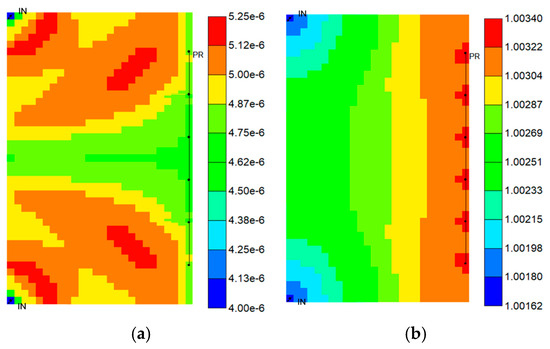

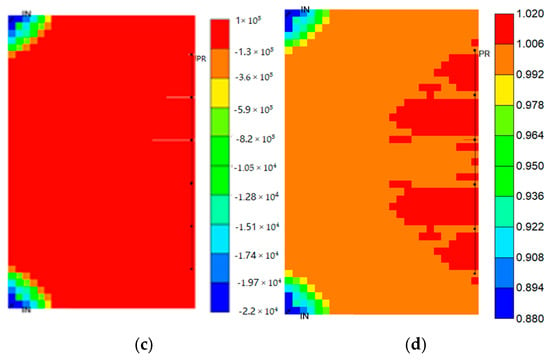

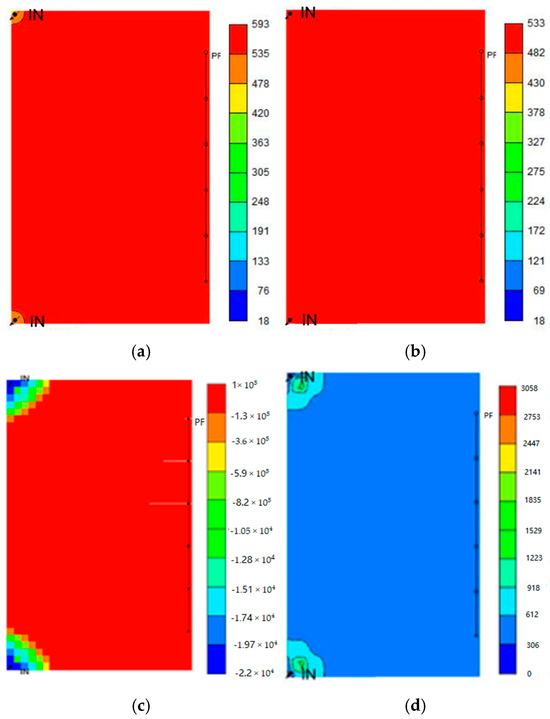

Figure 10 shows the simulated changes in permeability and porosity at the end of CO2 flooding when water–rock interactions are considered. It can be seen that due to water–rock reactions, the porosity and permeability of the fracture system within about 100 m of the injection well are significantly reduced, while those of the matrix system change only slightly, indicating a low degree of alteration in the matrix. This reduction in fracture system mobility is beneficial for increasing the bottomhole flowing pressure of the injection well and the average reservoir pressure, thereby enhancing the CO2 flooding mechanism. In terms of cumulative oil production, incorporating the storage mechanism increases total production from 5539 t (without considering the storage mechanism) to 5811 t, representing a 4.91% improvement. From the geochemical reaction results (Figure 11), the changes in calcite and kaolinite content in the fracture system are an order of magnitude greater than those in the matrix system. Furthermore, after CO2 injection, its reaction with formation water generates H+, which disrupts the original water–rock chemical equilibrium in the reservoir, causing the dissolution of calcite and anorthite. This dissolution raises the concentrations of Ca2+ and dissolved SiO2 in formation water, driving the kaolinite reaction to the left and resulting in precipitation. Overall, the intensity of mineral reactions is highest near the injection well, because the closer the location to the well, the earlier formation water comes into contact with CO2, and the longer the geochemical reactions persist, leading to more pronounced mineralogical changes. Therefore, water–rock interactions after CO2 injection are favorable for CO2 flooding.

Figure 10.

Changes in porosity and permeability at the end of water gas alternation oil recovery: (a) porosity variation in the matrix system; (b) permeability variation in the matrix system; (c) porosity variation in the fracture system; (d) permeability variation in the fracture system.

Figure 11.

Changes in calcite and kaolinite after completion of water-alternating-gas displacement: (a) amount of calcite change in the matrix system; (b) amount of kaolinite change in the matrix system; (c) amount of calcite change in the fracture system; (d) amount of kaolinite change in the fracture system.

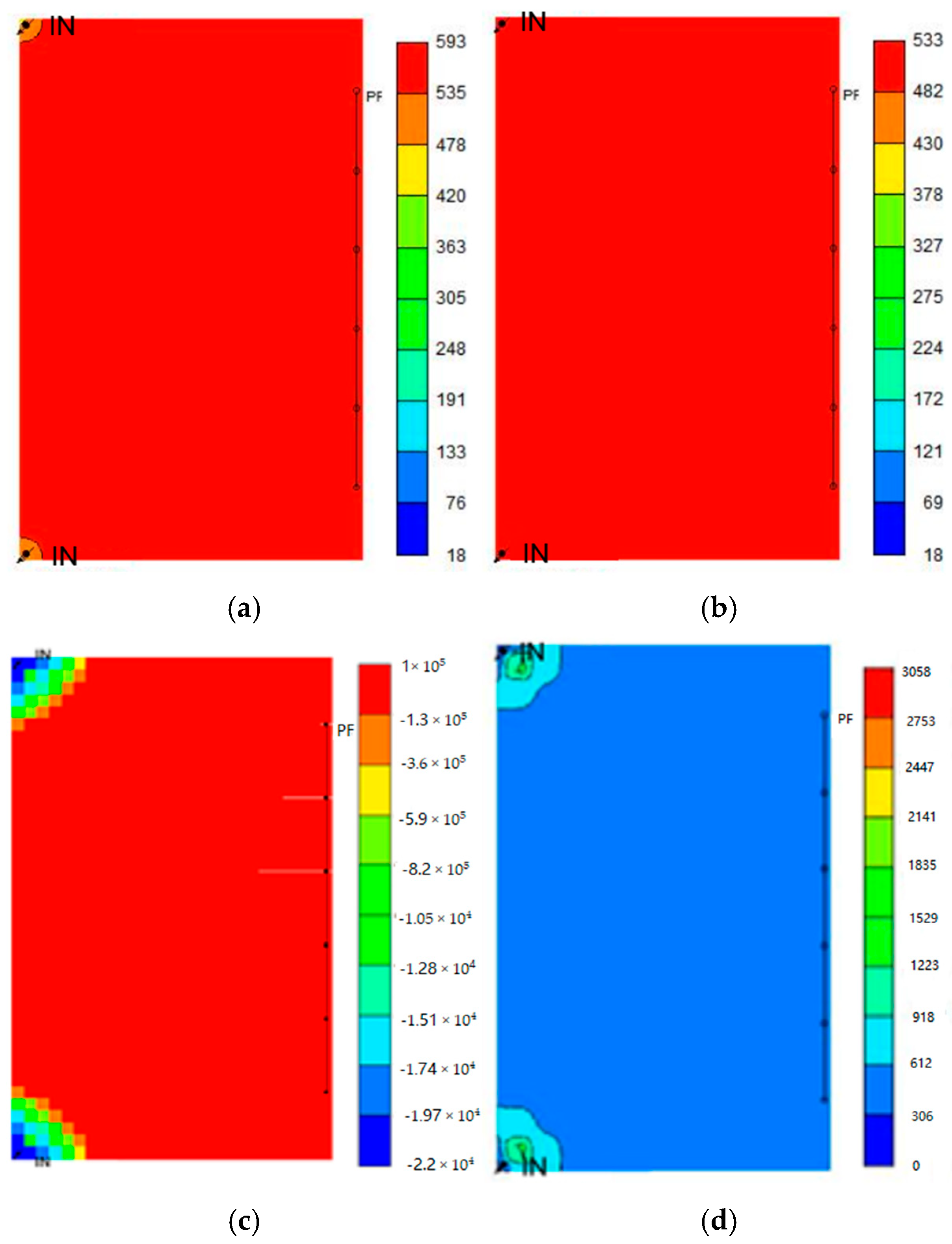

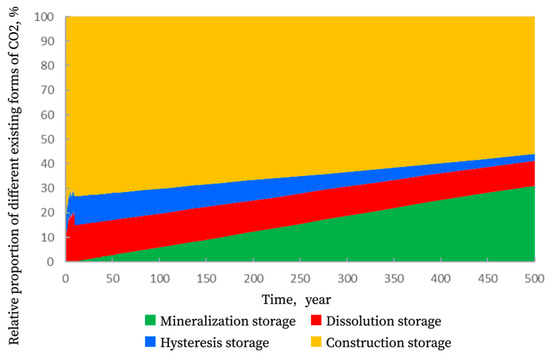

4.6. Time-Dependent Analysis of Different Trapping Mechanisms

Building on the earlier analysis of mineralogical changes and their impact on oil recovery, the long-term effects of CO2–water–rock reactions on the storage state of CO2 were further examined. It is generally accepted that after CO2 is injected into a reservoir, it exists mainly in four forms: free gas (structural trapping), residual gas (capillary trapping), dissolved gas (solubility trapping), and mineralized products from water–rock reactions (mineral trapping) [23,24]. Krevor [25] and Cui [26], among others, have conducted in-depth studies on this topic. In this work, we focus on the time dependence of different CO2 trapping mechanisms in the Jiyuan tight oil reservoir. Figure 12 shows the temporal variation in storage states for scenario 4. During the oil recovery stage, the order of storage capacity from largest to smallest is structural, solubility, residual, and mineral trapping, with proportions of 69.73%, 20.81%, 8.92%, and 0.53%, respectively. As water–rock reactions proceed, free and residual CO2 gradually convert into mineral forms stored within the reservoir [27]. After 500 years, the order of storage capacity changes to structural, mineral, solubility, and residual trapping, with proportions of 55.91%, 31.08%, 10.12%, and 2.89%, respectively. This indicates that about 15% of the free CO2 and 6% of the residual CO2 are transformed into mineralized CO2, contributing to the permanent and secure storage of CO2. It is crucial to highlight that this substantial long-term increase in mineral trapping is primarily governed by the slower kinetics of silicate mineral reactions. While initial calcite dissolution facilitates the process by altering the brine chemistry, the sustained dissolution of feldspar and subsequent precipitation of secondary carbonate and clay minerals are the dominant mechanisms for permanent CO2 sequestration over multi-century timescales.

Figure 12.

CO2 storage variation at different states.

5. Conclusions

In the tight sandstone reservoir of the Jiyuan Oilfield, the primary mineral components include calcite, quartz, and feldspar. When these minerals interact with CO2-saturated formation water, the dominant water–rock reaction processes involve the dissolution of calcite and feldspar, along with the dissolution and precipitation of quartz. Among these reactions, calcite dissolution plays a key role because the dissolution of CO2 in water generates a weak acid, lowering the pH. This decrease in pH disrupts the original chemical equilibrium between water and rock in the reservoir, making calcite more prone to dissolution. As calcite dissolution significantly alters the chemical composition of the water, it is regarded as the controlling reaction, with potential implications for the pore structure and permeability of the reservoir. The reactions are influenced by temperature and pressure, with both factors jointly affecting the dissolution of calcite and feldspar. An increase in temperature accelerates reaction rates but reduces CO2 solubility, thereby slowing the process, while higher pressure increases CO2 solubility but has no major effect on the overall reaction process. Coupled numerical simulations of CO2 flooding and sequestration indicate that water–rock reactions reduce natural fracture permeability near the injection well, which is favorable for CO2 flooding. At the end of the flooding stage, the proportion of CO2 stored via mineralization accounts for only 0.53% of the total stored CO2, but this proportion gradually increases over time, reaching 31.08% after 500 years.

Furthermore, while this study provides a deterministic forecast, it is important to acknowledge the inherent uncertainties in long-term predictions. The rates of mineralization and ultimate storage efficiency are sensitive to a range of geological and operational parameters. Key sources of uncertainty include the initial mineralogical composition of the reservoir (e.g., the relative fractions of calcite versus feldspar), the salinity of the formation water, and the long-term evolution of reservoir pressure and temperature. Future work should focus on comprehensive uncertainty quantification and sensitivity analysis to assess the range of possible outcomes and to develop more robust risk assessments for CO2 geological sequestration projects. Finally, we acknowledge the limitations of this study, which suggest avenues for future research. The experimental duration of 14 days was designed to capture the kinetics of fast-acting reactions like calcite dissolution for model calibration; long-term behavior was assessed via simulation. The use of powdered samples maximizes reactive surface area to measure intrinsic kinetics, but differs from intact cores where flow is constrained; our dual-porosity model is an attempt to bridge this gap. Additionally, this study focused on a pure CO2 system. The presence of impurities such as SO2 or H2S in the injected gas stream would introduce additional, complex geochemical reactions and could significantly alter the outcomes. Future work should aim to incorporate these factors for a more comprehensive assessment of CO2 sequestration in tight reservoirs.

Author Contributions

Methodology, J.J., W.F. and Y.L.; Software, M.Q.; Validation, J.J. and W.F.; Formal analysis, Y.L. and M.Q.; Resources, W.F.; Data curation, Y.L.; Writing—original draft, J.J. and Y.L.; Writing—review and editing, J.J. and M.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Junhong Jia, Wei Fan, Yao Lu were employed by Exploration and Development Research Institute of PetroChina Changqing Oilfield Branch. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Li, S.; Wang, Y.; Deng, X.; Sun, D.; Yang, Z. Study on water displacement and imbibition features of Chang 6 & Chang 8 tight oil reservoir in Ordos Basin. Unconv. OilGas 2024, 11, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Hamidreza, L.; Kamy, S. Simulation study of CO2 huff-n-puff process in Bakken tight oil reservoirs. In SPE Western Regional Meeting; SPE Denver: Denver, CO, USA, 2014; p. SPE-169575. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, Q.; Lu, M.; Zhong, A. Study on fracture morphology of CO2 energized fracturing of continental shale oil in Dongying Sag. Pet. Drill. Tech. 2023, 51, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Qi, Y.; Xue, X.; Tao, L.; Chen, W.; Wu, A. CO2 regional enhanced volumetric fracturing technology for shale oil horizontal wells in Ordos Basin. Pet. Drill. Tech. 2023, 51, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, T.; Xu, Z.; Liu, X.; Cai, X.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, W.; Li, X. Wenjian Zhu Research and Application of Pre-CO2 Energy Storage Fracturing Technology in Ultra-Low Permeability Reservoirs. In Proceedings of the International Field Exploration and Development Conference 2024, IFEDC 2024, Xi’an, China, 12–14 September 2024; Springer: Singapore, 2025; pp. 1665–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertier, P.; Swennen, R.; Laenen, B.; Lagrou, D.; Dreesen, R. Experimental identification of CO2-water-rock interactions caused by equestration of CO2 in Westphalian and Buntsandstein sandstones of the Campine Basin (N E-Belgium). Geochem. Explor. 2006, 89, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, J. Influencing factors and application prospects of CO2 flooding in heterogeneous glutenite reservoirs. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, A.; Yang, D.; Eshiet, K.I.I.I.; Sheng, Y. A review of the studies on CO2–brine–rock interaction in geological storage process. Geosciences 2022, 12, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaus, I. Role and impact of CO2-rock interactions during CO2 storage in sedimentary rocks. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2010, 4, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. Technical advancement and prospect for CO2 flooding enhanced oil recovery in low permeability reservoirs. Pet. Geol. Recovery Effic. 2020, 27, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachu, S.; Gunter, W.D.; Perkins, E.H. Aquifer disposal of CO2: Hydrodynamic and mineral trapping. Energy Convers. Manag. 1994, 35, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Bo, Q.; Chen, Y. Laboratory investigation of CO2 flooding. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2005, 32, 110–112. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; Liu, L.; Qu, X. Mechanism of CO2-sandstone interaction and formative authigenic mineral assemblage. Xinjiang Pet. Geol. 2007, 28, 579–584. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Li, T.; Gao, H.; Gao, Y.; Zhao, J.; Dou, L. Study on influencing mechanism of asphaltene precipitation on oil recovery during CO2 flooding in tight sandstone reservoirs. Pet. Geol. Recovery Effic. 2018, 25, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegner, L.; Pohlmeier, A.; Wang, Y.; Klinkenberg, M.; Bosbach, D.; Poonoosamy, J. In Situ Study of Coupled Mineral Dissolution and Precipitation Processes With Gas Production in Porous Media Using Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Water Resour. Res. 2025, 61, e2025WR040035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wei, D.; Chen, L. Mechanism Analysis and Evaluation of Formation Physical Property Damage in CO2 Flooding in Tight Sandstone Reservoirs of Ordos Basin, China. Processes 2025, 13, 2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, R.; Ou, C.; Lyu, D.; Liu, C.; Wu, H. Effect of isomorphic substitution of clay mineral layers on CO2 hydrate formation: Insights from molecular dynamics simulation study. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2025, 250, 213843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Wang, X.; Kang, Y.; Guo, C.; He, Q.; Li, C. Characterization of Stages of CO2-Enhanced Oil Recovery Process in Low-Permeability Oil Reservoirs Based on Core Flooding Experiments. Energies 2024, 17, 5469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozório, B.M.J.; Rosset, S.J.; Carvalho, D.A.L.; Concalves, S.D.A.; Santos, D.V.W.; Souza, S.D.B.C.; Farias, S.D.G.P. Influence of Agricultural Systems on the Physical-Granulometric Fractions of Soil Organic Matter and CO2 Emission in the Subtropical Region of Brazil. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2025, 56, 2459–2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunter, W.D.; Perkins, E.H.; Hutcheon, I. Aquifer disposal of acid gases: Modelling of water-rock reactions for trapping of acid wastes. J. Geochem. Explor. 2000, 69, 509–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nghiem, L.; Sammon, P.; Grabenstetter, J.; Ohkuma, H. Modeling CO2 storage in aquifers with a fully-coupled geochemical EOS compositional simulator. In Proceedings of the SPE/DOE Symposium on Improved Oil Recovery, Tulsa, OK, USA, 17–21 April 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lzgec, O.; Demiral, B.; Bertin, H.; Akin, S. Experimental and numerical modeling of direct injection of CO2 into carbonate formations. In Proceedings of the SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, San Antonio, TX, USA, 24–27 September 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, T.; Cui, C. Method for determining potential of dissolved CO2 storage in brine layers. Pet. Geol. Recovery Effic. 2023, 30, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, X.; Xu, C.; Zhang, C. CO2 sequestration morphology and distribution characteristics based on NMR technology and microscopic numerical simulation. Pet. Reserv. Eval. Dev. 2023, 13, 296–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krevor, S.C.M.; Pini, R.; Zuo, L.; Benson, S.M. Relative permeability and trapping of CO2 and water in sandstone rocks at reservoir conditions. Water Resour. Res. 2012, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, G.; Zhang, L.; Ren, S.; Zhang, Y. Geochemical reactions and CO2 storage efficiency during CO2 EOR process and subsequent storage. J. China Univ. Pet. (Ed. Nat. Sci.) 2017, 41, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Li, R.; Yang, S.; Qin, Y.; Gong, L.; Zhang, D. A novel algorithm for asphaltene precipitation modeling in shale reservoirs with the consideration of capillary pressure during the CCUS processes. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 248, 123217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).