Abstract

Identifying suitable catalyst types and efficient loading methods remains a key research challenge for implementing the in situ catalytic pyrolysis of tar-rich coal. This study investigated a lignite and a gas coal, employing NiCl2 solution for Ni2+ catalyst loading via room-temperature impregnation and hydrothermal treatment on coal particles sized 6–13 mm. The efficiency of Ni2+ loading through hydrothermal treatment and the characteristics of pyrolysis product distribution and composition before and after treatment were examined. The results indicated that after NiCl2 solution impregnation, the Ni2+ content in lignite increased from nearly undetectable to over 20 mg/g, whereas in gas coal, it only rose to less than 2 mg/g. Ion exchange is hypothesized to be a primary pathway for Ni2+ loading into coal. After hydrothermal treatment at 170 °C, the Ni2+ loadings in lignite and gas coal reached 33.6 and 1.45 mg/g, respectively. The loaded Ni2+ exhibited distinct catalytic effects on the two coals. For lignite, Ni2+ catalyzed the deoxygenation of oxygen-containing compounds and the aromatization of aliphatic hydrocarbons. For gas coal, hydrothermal treatment with NiCl2 solution at 170 and 220 °C promoted hydrogen transfer reactions, resulting in an increase in tar yield from 10.67% to 11.30% and 11.64%, respectively. Also, the H2 yield decreased, accompanied by a decrease in aromatic hydrocarbons and an increase in phenolic compounds within the tar.

1. Introduction

Tar-rich coal generally refers to coal with a tar yield greater than 7%. Tar-rich coal is an important energy resource for extracting oil and gas products [1]. In situ pyrolysis is a process that utilizes mining roadways or artificially created channels within the coal seam to generate oil and gas products by heating the coal seam in situ. This approach not only leaves most of the carbon as residual char underground, enabling the “low-carbon utilization” of high-carbon resources, but also offers several advantages, including the ability to operate at greater depths, reduced surface engineering, minimal surface subsidence and high safety factors. Therefore, in situ pyrolysis is considered a transformative direction for the future development of coal extraction and utilization technologies [2].

The in situ pyrolysis of tar-rich coal has not yet been industrialized, and there are a series of urgent issues that need to be addressed, one of which is the extraction of pyrolysis tar and gas [3]. Coal tar has a high content of resin and asphaltenes (the combined content of which usually exceeds 60%) and a high content of heteroatoms (mainly O and N), leading to high density and a high freezing point of coal tar. Given the long borehole length and large temperature gradient in in situ pyrolysis, coal tar tends to condense into viscous liquids or even solids when cooled, causing severe borehole blockages and extraction difficulties. Catalytic pyrolysis, which uses catalysts to promote or inhibit the interactions between free radicals or molecules, enables the directional regulation and quality optimization of tar and gas products. This process can reduce the content of heavy components and the freezing point of coal tar [4], offering the potential for the efficient extraction of tar from the in situ pyrolysis of tar-rich coal.

Catalyst loading in underground coal reservoir is a critical prerequisite for implementing catalytic pyrolysis. Research findings on coal catalytic pyrolysis demonstrate that transition metals such as Fe, Co and Ni exhibit significant catalytic effects on tar upgrading [5,6]. For example, Han et al. [5] investigated the catalytic upgrading of coal pyrolysis tar over char and metal-impregnated char (Co-char, Ni-char, Cu-char, Zn-char). It was found that when using Ni-char as the catalyst, the light tar yield and its content in the tar increased by 17.2% and 32.7%, respectively. For implementing in situ catalytic pyrolysis of tar-rich coal, aqueous solutions of these transition metals can be injected into coal seams under high pressure, enabling catalyst loading within the large-scale coal seam.

Besides catalytic pyrolysis, hydrothermal treatment was found to be an effective method to improve the quantity and quality of coal tar [7,8,9,10]. Zhang et al. [7] found that hydrothermal treatment of coal at 260 °C for 30 min raised the tar yield by about 18% for the treated brown coal and 5% for the treated sub-bituminous coal. They assumed that most of hydrogen radical formed by the interaction between water and coal is utilized to stabilization of free radical with medium molecular weight to hinder the second cleavage and cross-linking of free radical during pyrolysis [8]. Notably, the hydrothermal process inherently generates high-pressure conditions. Hydrothermal treatment of coal using aqueous transition metal salt solutions represents a potential method for catalyst loading in coal seams. However, no studies have yet systematically investigated either the catalyst loading efficiency in tar-rich coal or its influence on pyrolysis behavior under such conditions.

This study investigated two coal samples of different ranks (i.e., a lignite and a gas coal) as raw materials. These coal samples were hydrothermally treated using an aqueous NiCl2 solution to determine the catalyst loading efficiency. Fixed-bed reactor experiments were conducted to examine the pyrolysis characteristics and product distribution, with particular emphasis on the composition of oil and gas products. A comparative analysis between raw and hydrothermally treated coal samples was performed to explore the effects of hydrothermal treatment on NiCl2 loading capacity and its subsequent influence on pyrolysis behavior.

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Materials

Two types of coal samples, namely lignite and gas coal, were used in this study. The lignite was collected from the Zhanihe Coal Mine in Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, while the gas coal was obtained from the Xiegou Coal Mine in Shanxi Province. These samples were labeled as BC and GC, respectively. Table 1 presents the proximate and ultimate analyses of the two coal samples. As shown in the table, BC exhibits the highest oxygen content, with a dry ash-free basis value of 17.52%, which can be attributed to the presence of abundant oxygen-containing functional groups such as carboxyl, hydroxyl and carbonyl groups in lignite. To characterize the structural features of the coal samples, FTIR spectra of BC and GC were recorded in the mid-infrared range from 400 to 4000 cm−1 using a Fourier transform infrared spectrometer (Nicolet 6700, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The Omnic 8.2 software was used for baseline correction of infrared spectra and identification of peaks. The results will be presented and discussed in a subsequent section. Both coal samples were crushed and sieved to a particle size range of 6–13 mm, and then air-dried for subsequent experiments.

Table 1.

Proximate and ultimate analyses of tar-rich coal samples.

Nickel chloride hexahydrate (NiCl2·6H2O) with a purity of 99% was purchased from Shandong Keyuan Chemical Co., Ltd. (Jinan, China). Hydrochloric acid (HCl, 36 wt.%) was obtained from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). A nickel standard solution with a concentration of 1 mol/L was acquired from Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

2.2. Hydrothermal Treatment of Coal Samples

A 0.5 M NiCl2 solution was prepared using NiCl2·6H2O and employed for the hydrothermal treatment of coal samples with a particle size of 6–13 mm. The hydrothermal treatment was conducted in an autoclave (LC-HPR-C250, Lichen, Shaoxing, China) at a liquid-to-solid ratio of 4 mL/g of coal for a duration of 9 h, with temperatures set at 120, 170 and 220 °C, respectively. After the treatment, the coal samples were separated from the solution via filtration and dried at 100 °C for 12 h to remove moisture. The resulting samples were labeled by appending the treatment temperature to the original sample code (e.g., BC-120, BC-170 and BC-220 denote lignite treated at 120, 170 and 220 °C, respectively). It should be noted that, as a preliminary study, this work primarily investigates the effects of hydrothermal temperature on coal pyrolysis characteristics and nickel loading capacity under fixed NiCl2 concentration and treatment duration. For comparative purposes, an additional set of coal samples was impregnated at ambient temperature following the same subsequent processing steps as the hydrothermal treatment. These samples are identified as BC-A and GC-A, respectively.

2.3. Pyrolysis Experiments

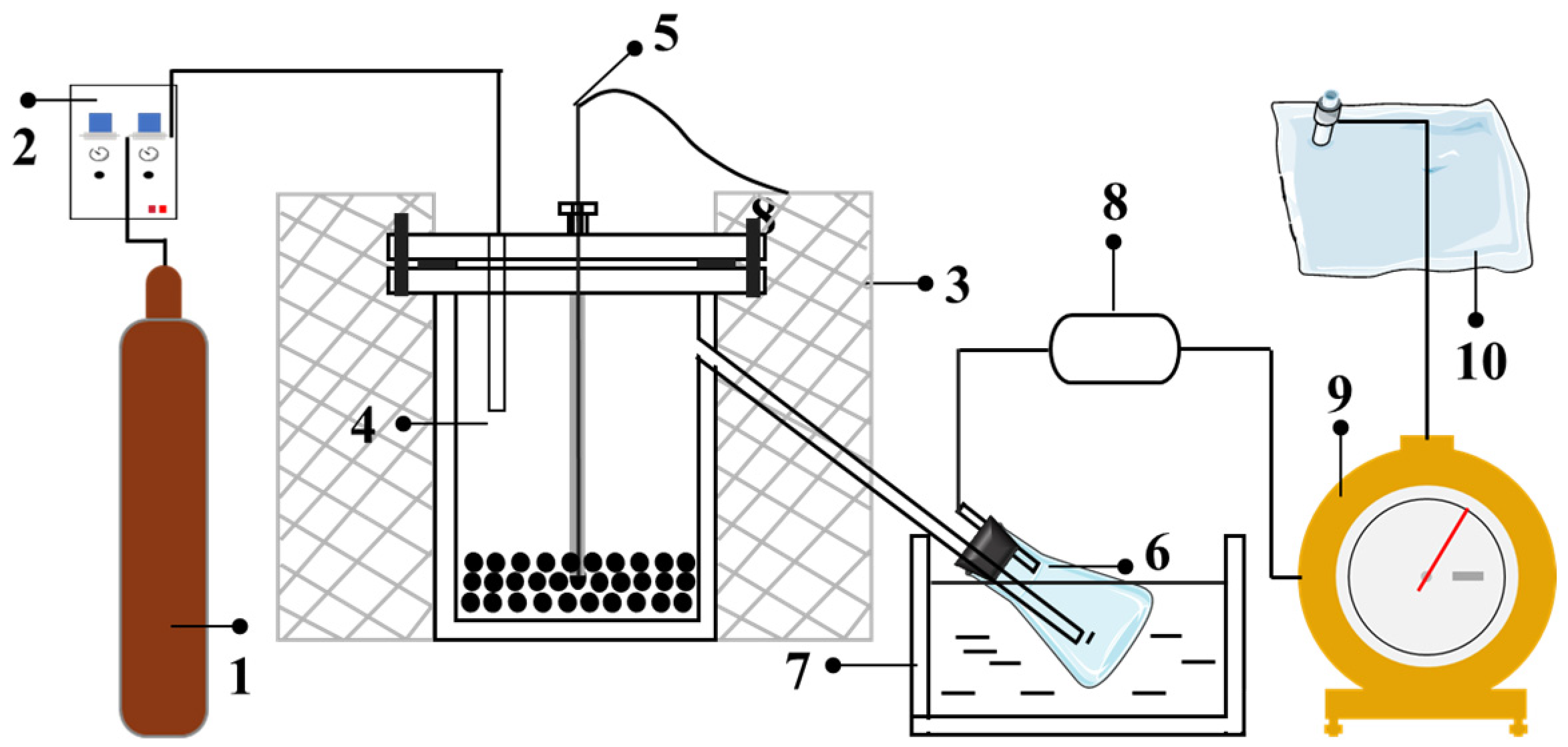

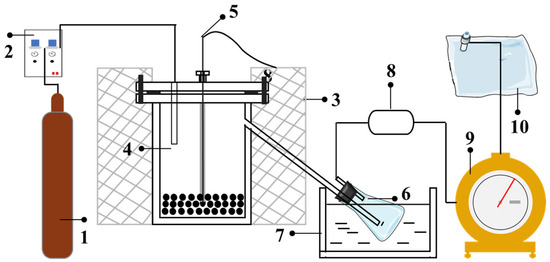

Pyrolysis experiments were conducted in a lab scale fixed-bed reactor (Figure 1), which was made of stainless steel [3,11]. The cylindrical reactor has a height of 950 mm and a diameter of 46 mm, and it was enclosed in an electric furnace. A thermocouple was installed in the coal bed to control the pyrolysis temperature. A tube was linked to the bottom of the reactor to introduce N2 to the reactor. The flow rate of N2 was controlled using a mass flow meter (D07-19B, Sevenstar, Beijing, China). For each experiment, approximately 50 g of coal particles was placed inside the reactor. The air inside the system was purged by N2, after which the coal was heated from room temperature to a final temperature of 550 °C by 5 °C/min, followed by an isothermal stage of 30 min.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the experimental pyrolysis system. (1. N2 cylinder; 2. Mass flow controller; 3. Electric-ring furnace; 4. Stainless steel reactor; 5. Thermocouple; 6. Conical flask; 7. Ice-water bath; 8. Drying tube; 9. Wet gas flow meter; 10. Gas sampling bag).

The produced volatile products were entrained by the carrier gas and passed through a conical flask immersed in a tank filled with ice and water. Most of the tar and water were condensed in the flask; the remaining part was retained and absorbed by a tube filled with silica gel and cotton. The volume of gas was recorded by a wet gas flow meter (LMF-1, Alpha, Changchun, China) and then collected in a sampling bag for gas chromatography analysis. When the set experiment time was over, the furnace was turned off and the reactor was cooled to room temperature. The semicoke mass was weighed after disassembling the device. The mass difference between the collection bottle before and after the reaction produced the tar–water mixture. Water and tar were separated by centrifugation, and the quantity of the water and tar was determined. The quantity of pyrolysis gas was obtained by difference. The yield of the product can be calculated based on the mass of the raw coal sample and the mass of the resulting product.

2.4. Characterization Methods

2.4.1. ICP-OES Analysis of Coal Samples

The nickel loading on the coal samples was determined using an inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (Optima 8300, PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA). The raw and hydrothermally treated coal samples were first pulverized to pass through an 80 mesh sieve. Subsequently, Ni2+ was eluted from the coal using 1 mol/L hydrochloric acid at a liquid-to-solid ratio of 20 mL per gram of coal. The mixture was agitated in an orbital shaker for 6 h. After agitation, the liquid and solid phases were separated by vacuum filtration, and the eluate was collected for analysis. A calibration curve was constructed using standard Ni2+ solutions with concentrations of 0, 1, 5, 10, 20, 30, 40, 60, 80 and 100 ppm, establishing the relationship between ion concentration and signal intensity. The concentration of Ni2+ in the eluate was then measured based on this calibration. The Ni loading on the coal was calculated taking into account the volume of the eluate, the measured Ni2+ concentration and the mass of the coal sample.

2.4.2. GC-MS Analysis of Tar Samples

The components of the tar samples were characterized by a gas chromatograph–mass spectrometer (Trace 1300-ISQ, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) equipped with a TG-5MS column (30 m × 0.25 mm ID × 0.25 μm). Briefly, tar was dissolved in chloroform to form a tar solution with a concentration of approximately 10 mg/mL. Approximately 1 μL of tar solution was introduced into the instrument using an automatic sampler with a split ratio of 50. The injector temperature was 280 °C. The oven temperature was kept at 40 °C for 3 min. The mixture was heated at a heating rate of 5 °C/min to 280 °C and maintained for 50 min. The transfer interface temperature and ion source temperature of the mass spectrometer were 280 °C and 200 °C, respectively. The solvent delay time was 3 min, and the scanning range was 40–600 m/z. The compounds were identified using the mass spectrometry library of the National Institute of Standards and Technology.

2.4.3. GC Analysis of Gaseous Products

Gas products were analyzed using gas chromatography (GC-8600, Beifentianpu Instrument, Beijing, China). The identification and quantification of CH4, H2 and CO were performed using a packed 5A molecular sieve column (4.5 m × 2 mm ID). The column temperature was 50 °C, and a thermal conductivity detector was used. CO2 was analyzed using a packed silica gel column (1 m × 2 mm ID) under the same operating conditions as for the detection of H2. The volume fractions of CH4, H2, CO and CO2 were determined using the external standard method. Based on the total volume of gaseous products and volume percentages of CH4, H2, CO and CO2, the gas component yield can be calculated.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Structural Properties of Coal Samples

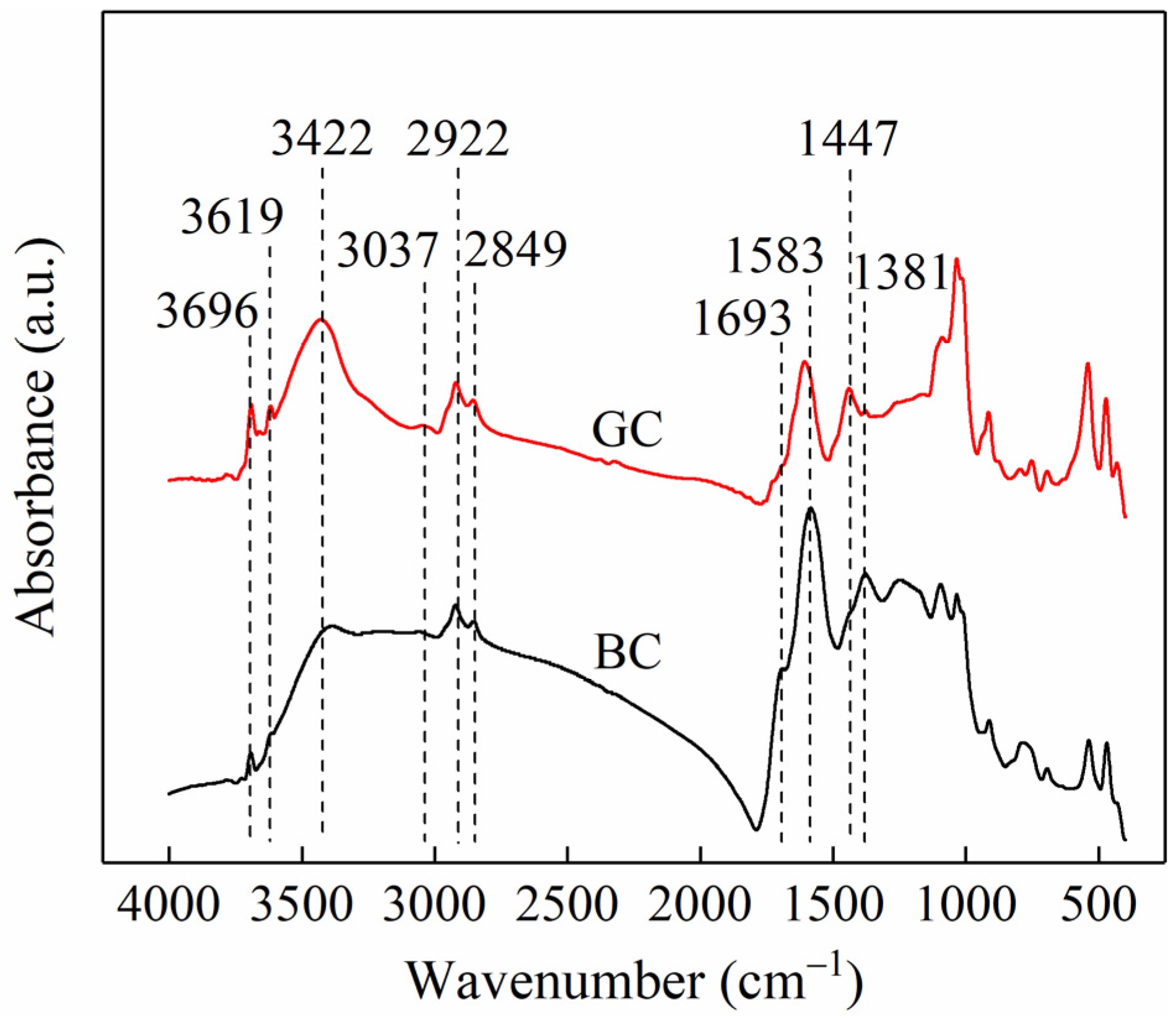

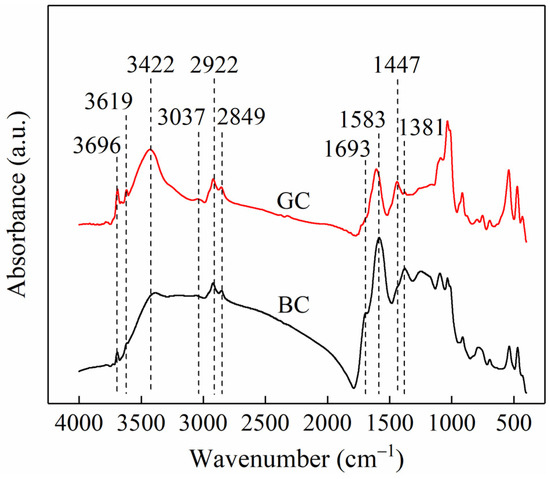

Figure 2 shows the FTIR spectra of the two coal samples. Based on assignments reported in the literature [12,13], the absorption peaks at 3629 and 3621 cm−1 are attributed to hydroxyl groups in the lattice of clay minerals. The peak at 3422 cm−1 corresponds to O-H stretching vibrations, while the band at 3037 cm−1 is assigned to aromatic C-H stretching. The peaks at 2922 and 2849 cm−1 are attributed to asymmetric and symmetric C-H stretching of methylene groups, respectively. A shoulder peak observed at 1693 cm−1 is associated with C=O stretching vibrations. The absorption at 1583 cm−1 is ascribed to aromatic C=C vibrations, the band at 1447 cm−1 to CHx bending vibrations, and the peak at 1381 cm−1 to C-H deformation in methyl groups. A comparison of the spectra of the two coal samples reveals that the absorption peaks at 3696 and 3619 cm−1 are more intense in GC than in BC, indicating a higher content of clay minerals in GC. This observation is consistent with its higher ash content. In contrast, the shoulder peak at 1693 cm−1 is more pronounced in BC than in GC, suggesting a greater abundance of C=O functional groups in the lignite sample.

Figure 2.

FTIR spectra of BC and GC samples.

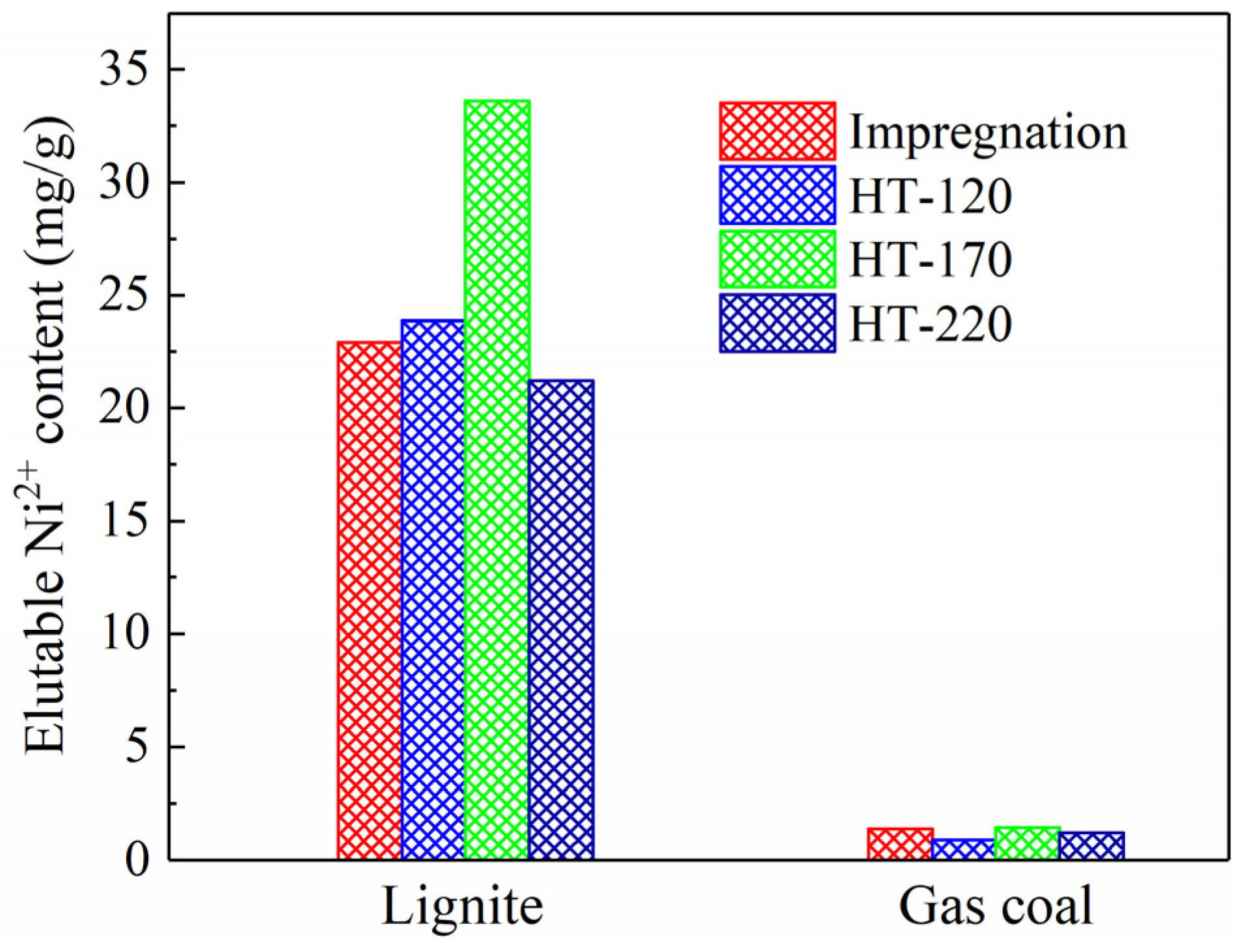

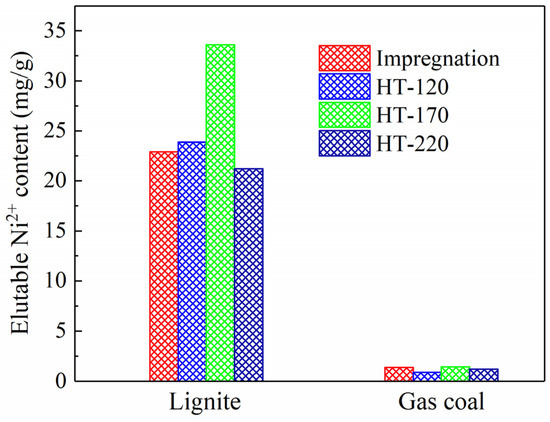

3.2. Ni2+ Loading Amount of Coal Samples

Figure 3 shows the loadings of Ni2+ on the coal samples after impregnation at room temperature and hydrothermal treatment. Almost no Ni2+ was eluted from the two types of raw coal. As shown in Figure 3, the elutable Ni2+ content increased significantly after impregnation and hydrothermal treatment. The elutable Ni2+ content in the lignite samples exceeded 20 mg/g, whereas that in the gas coal samples was considerably lower, not exceeding 2 mg/g. It is hypothesized that ion exchange is the primary mechanism for Ni2+ loading onto the coal, whereby Ni2+ replaces ions such as H+ and Na+ in the coal structure. As mentioned previously, lignite has the lowest coal rank, contains the highest abundance of carboxyl functional groups, thereby providing the largest number of ion exchange sites. This explains why the Ni loading exceeded 2% (20 mg/g) in the lignite samples.

Figure 3.

Elutable Ni2+ content in coal samples after impregnation at room temperature and hydrothermal treatment at 120, 170 and 220 °C.

Figure 3 also illustrates the variation in Ni2+ loading with treatment temperature. For the lignite samples, the Ni2+ loading initially increased and then decreased with rising hydrothermal temperature, reaching a maximum of 33.6 mg/g at 170 °C. In this study, coal particles sized 6–13 mm were used for the loading process. The Ni2+ loading is influenced not only by the number of available ion exchange sites but also by the development of pores and fractures during hydrothermal treatment. Theoretically, increasing the hydrothermal temperature from 120 to 220 °C raised the pressure inside the autoclave from approximately 0.20 to about 2.32 MPa, assuming no contribution from air pressure. Lignite, which is inherently rich in pores and has relatively low mechanical strength [14,15], exhibited more pronounced pore development under high pressure, facilitating the penetration of NiCl2 solution into the particle interior and thereby enhancing Ni2+ loading. On the other hand, higher temperatures promoted the decomposition of thermally unstable carboxyl functional groups in lignite [16], reducing the number of exchange sites and consequently decreasing the loading capacity. Additionally, under high temperature and pressure, the extractive capability of water was enhanced [17,18], which may improve the solubility of previously exchanged Ni2+, leading to their removal and a subsequent reduction in overall loading. A similar trend was observed for the gas coal samples, where Ni2+ loading reached a maximum of 1.45 mg/g at 170 °C.

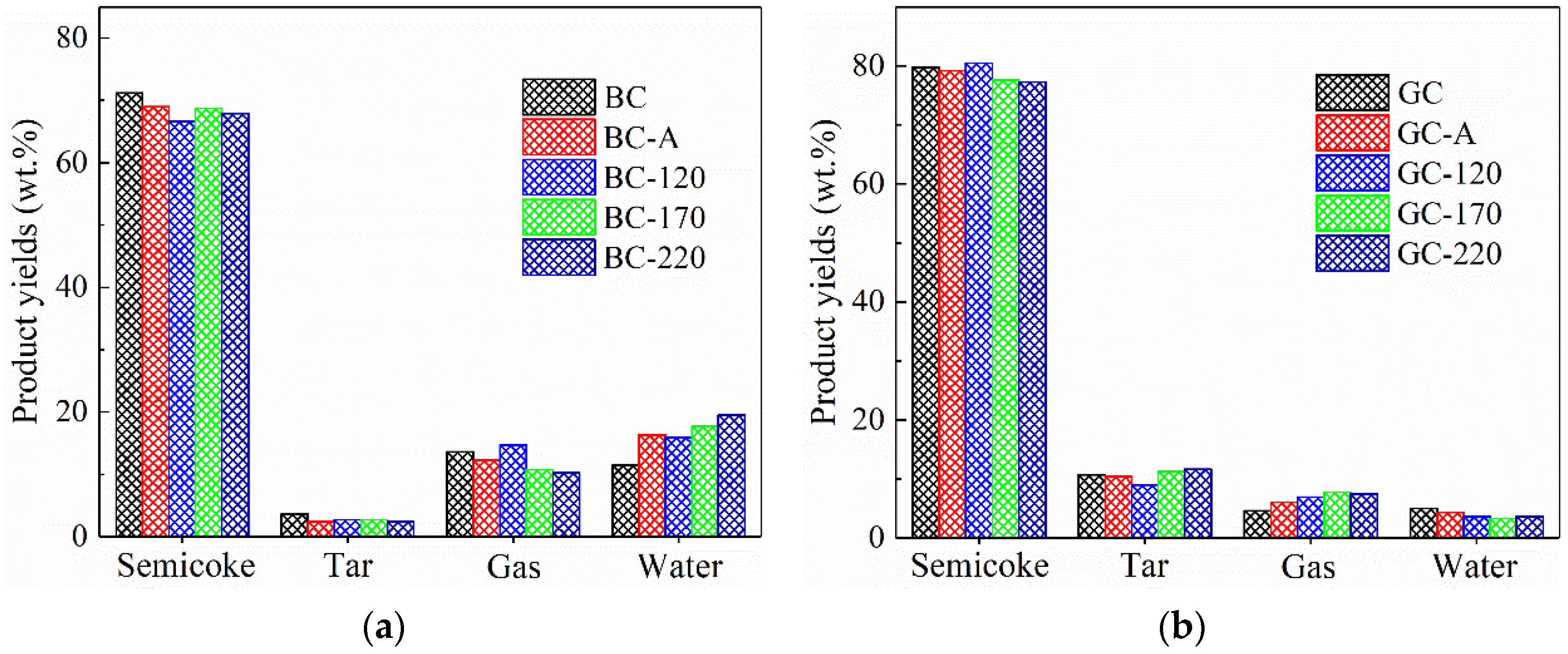

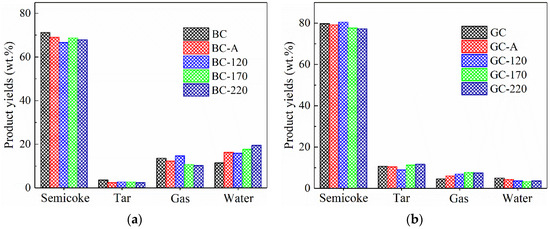

3.3. Pyrolysis Products Distribution

Figure 4 illustrates the distribution of pyrolysis products for the two coal samples. As shown in Figure 4a, after either impregnation or hydrothermal treatment, the yields of semicoke, tar and gas from lignite decreased, while the water yield increased significantly and rose further with higher hydrothermal temperature. In fact, hydrothermal treatment was typically employed for non-evaporative dewatering of lignite [7,8,9,10], which would theoretically lead to a reduction in water content. However, the coal samples used in this study were in granular form (6–13 mm). Due to the abundance of hydrophilic functional groups in lignite, the NiCl2 solution was forced into the internal pores and fractures of the particles during hydrothermal treatment. Even subsequent drying at 100 °C failed to completely remove this moisture, resulting in a notable increase in water yield during pyrolysis. This mechanism may also serve as an additional factor contributing to the high Ni2+ loading observed in the lignite samples.

Figure 4.

Product distribution of pyrolysis of coal samples. (a) Lignite. (b) Gas coal.

Figure 4b shows the pyrolysis product distribution of GC. After impregnation with NiCl2 solution at ambient temperature or hydrothermal treatment, the semicoke yield decreased while the yield of pyrolysis gas increased, indicating that the loaded Ni catalyst promotes the formation of gaseous products. This is consistent with reports in the literature that Ni, acting as a Lewis acid, facilitates cracking reactions [19,20]. After hydrothermal treatment at 170 and 220 °C, the tar yield increased from 10.67% to 11.30% and 11.64%, respectively, suggesting that hydrothermal treatment with NiCl2 solution enhances tar production. It is worth noting that the GC sample used in this study exhibited certain caking properties [3]. During pyrolysis, it forms a metaplast—a gas–liquid-solid three-phase colloidal system. As a transition metal, Ni can catalyze hydrogen transfer reactions, promoting the combination of hydrogen radicals with free radicals generated from BC pyrolysis, thereby facilitating tar formation. Furthermore, it has been reported that hydrothermal treatment can suppress cross-linking reactions during pyrolysis [8,9], which may also contribute to the increased tar yield observed.

3.4. Analysis of Tar Samples

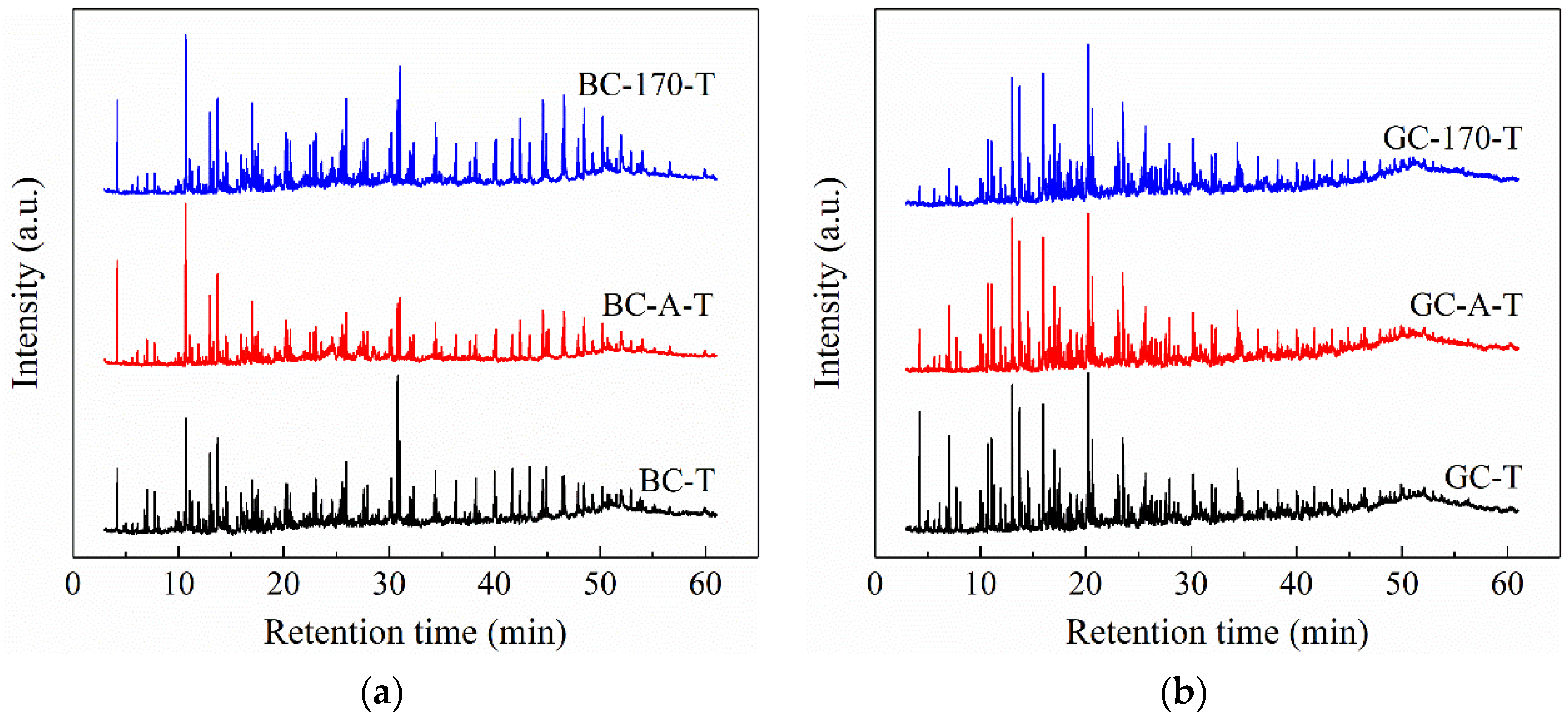

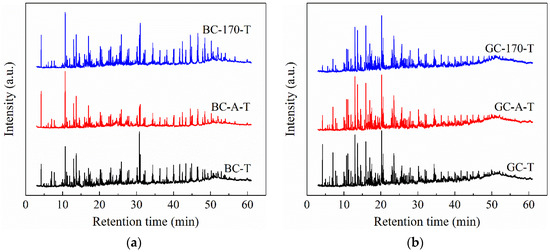

As previously described, the highest Ni2+ loadings on both BC and GC were achieved after hydrothermal treatment with NiCl2 solution at 170 °C, accompanied by an increased tar yield during GC pyrolysis. To evaluate the influence of different catalyst loading methods on tar composition, the primary components of the pyrolysis tar derived from the raw coal, room-temperature impregnated coal samples and 170 °C hydrothermally treated coal samples were analyzed by GC–MS. Figure 5 displays the total ion chromatograms (TICs) of the obtained tar samples. The letter “T” appended to the coal sample name denotes the tar derived from pyrolysis of the corresponding coal sample. For instance, BC-170-T refers to the tar produced from the pyrolysis of BC-170. The major constituents of the tar were identified by matching the acquired mass spectra against the NIST mass spectral database.

Figure 5.

Total ion chromatograms of tar samples derived from pyrolysis of coal samples. (a) Lignite. (b) Gas coal.

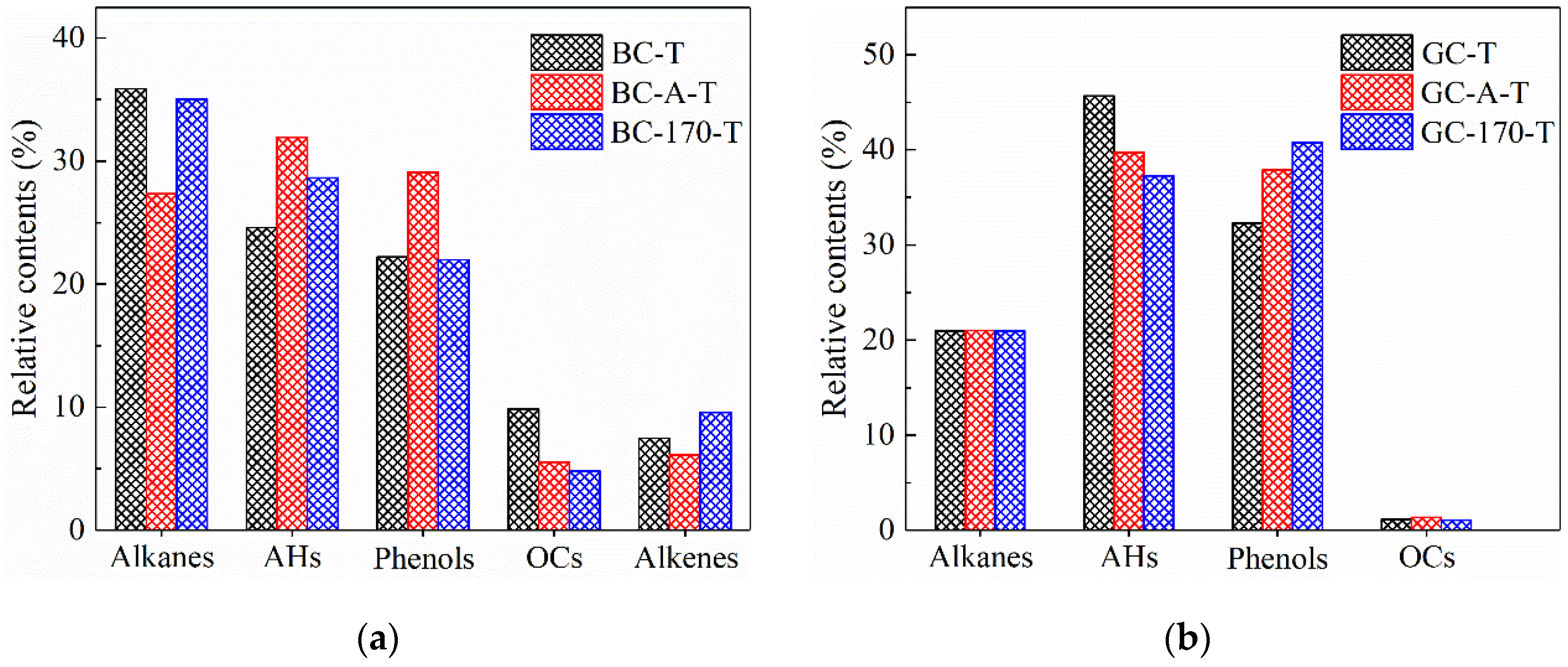

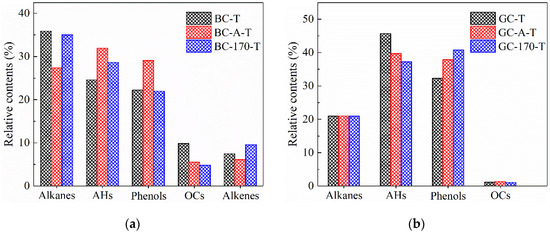

The main components of BC-T can be categorized as alkanes, alkenes, aromatic hydrocarbons (AHs), phenols and oxygen-containing compounds (OCs, primarily ketones, esters and alcohols). The major constituents of GC-T are similar to those of BC-T, with the exception that no alkenes were detected. Figure 6 illustrates the relative abundance of each compound class. As shown in the figure, alkanes, AHs and phenols constitute the predominant components of the tar, collectively accounting for more than 80% of the detectable compounds in BC-T and over 95% in GC-T. Compared to BC-T, GC-T exhibits a lower abundance of alkanes but higher proportions of AHs and phenols, along with a notably lower content of OCs. These trends are consistent with the H/C and O/C atomic ratios of the two coal samples, as presented in Table 1. This compositional difference can be attributed to the higher degree of coalification of GC, which results in a molecular structure richer in aromatic rings and poorer in aliphatic chains, accompanied by a gradual decrease in oxygen content [21,22].

Figure 6.

Peak area percentages of major components present in tar samples. (a) Tar samples of lignite. (b) Tar samples of gas coal.

Figure 6a shows that after Ni2+ loading via impregnation and hydrothermal treatment, the content of alkanes and OCs in the tar samples of lignite decreased, while the content of AHs increased. Notably, these changes were more pronounced after impregnation. Specifically, the relative contents of alkanes and OCs decreased from 35.9% and 9.8% to 27.3% and 5.5%, respectively, whereas the AHs content increased from 24.6% to 31.9%. These results indicate that Ni2+ promoted both the deoxygenation of oxygen-containing compounds and the aromatization of aliphatic hydrocarbons, consistent with previous reports on the catalytic role of Ni in aromatization reactions [23,24]. Although the amount of Ni2+ loaded via impregnation was lower than that achieved through hydrothermal treatment, its catalytic effect appears more pronounced. A possible explanation is that the hydrothermal process may cleave weak bonds within the macromolecular structure of coal, resulting in a more loosely organized architecture. This structural alteration could reduce the likelihood of aromatization reactions and thereby attenuate the catalytic efficiency of Ni2+ in promoting aromatization [8,10].

Figure 6b reveals that after impregnation and hydrothermal treatment with NiCl2 solution, the tar samples derived from gas coal pyrolysis exhibited a decrease in aromatic hydrocarbons and an increase in phenolic compounds, with the hydrothermal treatment showing a more pronounced effect. In contrast, the relative contents of alkanes and OCs remained largely unchanged. These observations suggest that the catalytic effect of Ni2+ on the pyrolysis of gas coal differs from that on lignite. According to the study by Le et al. [25], it is speculated that Ni2+ exhibits a high affinity for the electronegative oxygen atoms within C–O bonds of aromatic structures. The adsorption of metal ions weakened the C–O bond strength, facilitating the cleavage of various weak linkages—such as ether bonds—that connect condensed aromatic units within the macromolecular framework of coal, thereby promoting the release of phenolic compounds. Furthermore, the introduction of Ni2+ disrupted the self-associating hydrogen bonds among pre-existing phenolic species. As a result, low-temperature cross-linking reactions mediated by such hydrogen bonding were inhibited, leading to an increased yield of free phenolic compounds during thermal treatment [26].

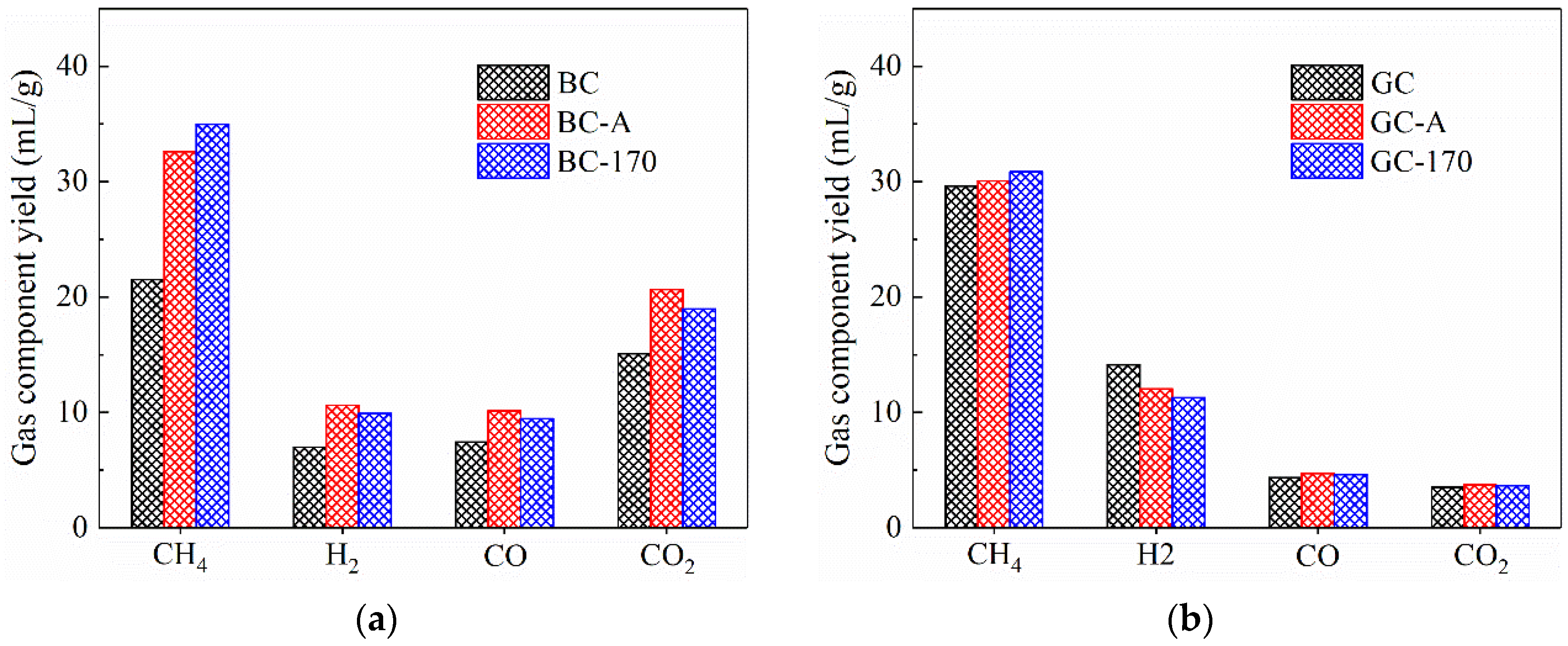

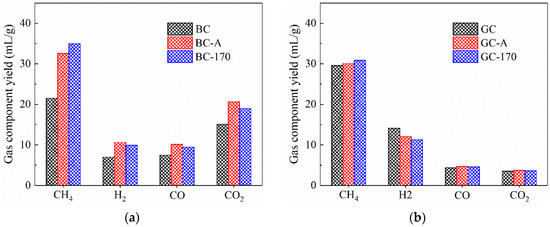

3.5. Analysis of Pyrolytic Gases

Figure 7 shows the yields of gaseous products from coal pyrolysis. As illustrated in Figure 7a, both impregnation at room temperature and hydrothermal treatment resulted in increased yields of methane and hydrogen compared to the original BC sample. It is generally accepted that during coal pyrolysis, methane is primarily generated through the cleavage of alkyl side chains attached to aromatic rings, while hydrogen is mainly produced via aromatization of aliphatic chains and condensation of aromatic rings [27]. Analysis of the tar composition indicated that Ni2+ promotes the aromatization of alkanes, thereby enhancing hydrogen formation. Furthermore, previous studies have reported that Ni can facilitate the condensation of aromatic rings, leading to increased methane release [23,24]. In addition, Ni is known to catalyze deoxygenation reactions of oxygen-containing compounds [28,29], which contributed to the observed increases in the yields of both CO and CO2.

Figure 7.

Yields of gas components derived from pyrolysis of coal samples. (a) Lignite. (b) Gas coal.

Figure 7b indicates that for the pyrolysis of GC, neither impregnation nor hydrothermal treatment had a significant effect on CH4 yield; however, the H2 yield decreased from 14.13 mL/g to 12.02 and 11.27 mL/g, respectively. A possible explanation is that during the pyrolysis of GC, a metaplast—a three-phase gas–liquid–solid intermediate—is formed. This suggests that the loaded Ni2+ was tightly encapsulated within the metaplast, meaning that Ni2+ primarily catalyzed the primary reactions of GC pyrolysis. It is proposed that Ni2+ facilitates the transfer of hydrogen radicals to nearby medium-molecular-weight free radicals [30], promoting tar formation through radical termination reactions, which aligns with the slight increase in tar yield. In contrast, during the catalytic pyrolysis of BC, Ni2+ is dispersed within the porous matrix of the coal, where it mainly catalyzed secondary reactions of tar vapors passing through the porous char, resulting in a different catalytic behavior. Furthermore, the yields of CO and CO2 remained almost unchanged under Ni2+ catalysis, which is consistent with the minimal variation in oxygen-containing compounds observed in the tar, as shown in Figure 6b.

3.6. Limitations and Implications of This Study

This study demonstrated the loading of Ni2+ catalysts onto 6–13 mm particles of lignite and gas coal via hydrothermal treatment with a NiCl2 solution. After treatment at 170 °C, the Ni2+ loading in lignite reached 33.6 mg/g. The incorporated Ni2+ effectively catalyzed deoxygenation and aromatization reactions during pyrolysis, promoting the formation of aromatic hydrocarbons and H2. In contrast, the maximum Ni2+ loading achieved in gas coal was only 1.45 mg/g, although the loaded Ni2+ still exhibited catalytic activity toward the formation of phenolic compounds. These findings provide preliminary evidence supporting the feasibility of using hydrothermal treatment to load water-soluble catalysts onto coal, offering a potential reference for the in situ catalytic pyrolysis of coal to produce aromatic and phenolic chemicals as well as hydrogen-rich gas.

This study was limited to a fixed NiCl2 concentration (0.5 M) and a constant treatment duration (9 h), with the hydrothermal temperature (120, 170 and 220 °C) as the only variable. Future investigations should explore the effects of varying solution concentrations, treatment times and higher temperatures, as well as different metal ion species, on both catalysts loading efficiency and subsequent catalytic behaviors during pyrolysis. Furthermore, since ion exchange at carboxyl sites is considered a crucial mechanism for metal ion loading, pretreatments such as mild oxidation (e.g., using air or H2O2) could be applied to introduce additional oxygen-containing functional groups [31]. Additionally, permeability-enhancing methods including hydraulic fracturing or acid etching may help create fractures and pores within the coal matrix, thereby facilitating higher catalyst loading and improving catalytic performance [32]. A potential alternative is to integrate acid treatment and mild oxidation into a single-step process. For instance, Qin et al. [33] employed piranha solution (H2O2/H2SO4) as the oxidant to mildly oxidize coal liquefaction residue for the preparation of functional carbon dots, during which mineral matter was simultaneously removed. Further research is needed to explore pretreatment strategies that combine acid treatment with mild oxidation.

4. Conclusions

This study examines the efficacy of Ni2+ catalyst loading via room-temperature impregnation and hydrothermal treatment using NiCl2 solution on 6–13 mm particles of lignite and gas coal. The distribution and composition of pyrolysis products were systematically characterized before and after treatment to evaluate the influence of Ni2+ incorporation. The main results can be summarized as follows:

- The loading of Ni2+ increased from nearly undetectable levels to over 20 mg/g in lignite after impregnation with NiCl2 solution, while in gas coal it remained below 2 mg/g. Ion exchange is proposed as a key mechanism for Ni2+ incorporation into coal, with the abundant carboxyl functional groups in lignite providing favorable exchange sites. The high pressure generated during hydrothermal treatment further enhanced Ni2+ diffusion and loading within the coal particles. After hydrothermal treatment at 170 °C, the Ni2+ loadings reached 33.6 mg/g in lignite and 1.45 mg/g in gas coal, respectively.

- The loaded Ni2+ exerted distinct catalytic effects during the pyrolysis of lignite and gas coal. In lignite, Ni2+ catalyzed deoxygenation of oxygen-containing compounds and aromatization of aliphatic hydrocarbons, leading to a decrease in tar yield, a reduction in oxygenates and alkanes, and an increase in aromatic hydrocarbons in the tar. In contrast, in gas coal, Ni2+ primarily promoted cracking reactions, resulting in increased gas yield. Additionally, hydrothermal treatment with NiCl2 at 170 and 220 °C enhanced hydrogen transfer reactions, which increased tar yield while decreasing aromatic hydrocarbons and increasing phenolic compounds in the tar.

- This study preliminarily demonstrates the feasibility of loading Ni2+ catalysts into lignite via hydrothermal treatment. However, the relatively low Ni2+ loading in gas coal suggests the need for further research. Future work should focus on pretreatment methods such as mild oxidation or fracturing to enhance permeability and introduce additional oxygen-containing functional groups. These approaches are expected to improve both the Ni2+ loading capacity and catalytic efficiency in coal samples.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, writing—original draft preparation, L.X. and X.W.; methodology, investigation, L.X., X.W., Y.T. and C.W.; validation, writing—review and editing, L.X., Y.L., Y.Z., S.J., J.C. and Z.C.; resources, supervision, project administration, X.W. and Z.C.; data curation, X.W. and C.W.; visualization, X.W.; funding acquisition, Z.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Open Fund of CNOOC key laboratory of liquefied natural gas and low-carbon technology (QDKJZH-2024-65) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2024ZKPYHH04).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Li Xiao, Xiaodan Wu, Youwu Li, Ying Tang, Yue Zhang, Shixin Jiang, and Jingyun Cui were employed by the company China National Offshore Oil Corporation. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The China National Offshore Oil Corporation had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Wang, S.; Shi, Q.; Wang, S.; Shen, Y.; Sun, Q.; Cai, Y. Resource property and exploitation concepts with green and low-carbon of tar-rich coal as coal-based oil and gas. J. China Coal Soc. 2021, 46, 1365–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Shi, Q.; Sun, Q.; Cui, S.; Kou, B.; Qiao, J.; Geng, J.; Zhang, L.; Tian, H.; Jiang, P.; et al. Strategic value and scientific exploration of in-situ pyrolysis of tar-rich coals. Coal Geol. Explor. 2024, 52, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Z.; Wang, C.; Kuang, W.; Ying, T.; Wu, X.; Liu, S. Product characterization and pore structure evolution of a tar-rich coal following pyrolysis under nitrogen, steam/nitrogen, and oxygen/nitrogen atmospheres. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 2024, 180, 106563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Lang, W.; Ouyang, J.; Zhao, L.; Shen, Y. Catalytic upgrading of coal tar to produce value-added chemicals and fuels: A review on processes, catalytic mechanisms and catalysts. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 500, 157420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Wang, X.; Yue, J.; Gao, S.; Xu, G. Catalytic upgrading of coal pyrolysis tar over char-based catalysts. Fuel Process. Technol. 2014, 122, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, W.; Yang, L.; Gu, W.; Zhu, J.; Yang, H.; Jin, L.; Hu, S.; Hu, H. In-situ catalytic upgrading of coal pyrolysis volatiles over red mud-supported nickel catalysts. Fuel 2022, 324, 124742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Liu, P.; Lu, X.; Lan, W.; Tie, P. Upgrading of low rank coal by hydrothermal treatment: Coal tar yield during pyrolysis. Fuel Process. Technol. 2016, 141 Pt 1, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Le, J.; Zhang, D.; Wang, S.; Pan, T. Free radical reaction mechanism on improving tar yield and quality derived from lignite after hydrothermal treatment. Fuel 2017, 207, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhao, H.; Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Zhao, G.; Wang, Y.; Zeng, M. Effect of hydrothermal upgrading on the pyrolysis and gasification characteristics of baiyinhua lignite and a mechanistic analysis. Fuel 2020, 276, 118081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhao, H.; Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Zhao, G.; Wang, Y.; Zeng, M. Effect of a combined process on pyrolysis behavior of Huolinhe lignite and its kinetic analysis. Fuel 2020, 279, 118485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Chang, Z.; Ma, Y.; Wang, C.; Hang, H.; Wang, X.; Liu, S. Enhancing light tar production from tar-rich coal through low-temperature oxidation-assisted pyrolysis. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 2025, 191, 107232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Bao, Y.; Wang, C.; Hu, Y. Study on the Extraction Mechanism of Metal Ions on Small Molecular Phase of Tar-Rich Coal under Ultrasonic Loading. Processes 2024, 12, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Wu, C.; Gao, B.; Lu, X.; Bei, W.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Z. Structural Characterization of Low-Rank Coals in the Ningdong Coalfield Under the Control of the First Coalification Jump. Processes 2025, 13, 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Niu, S.; He, J.; Kai, Z.; Qin, Z. Deformation and Pore Structure Characteristics of Lignite Pyrolysis with Temperature Under Triaxial Stress. Processes 2025, 13, 1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Ting, L.; Bai, L. Micromechanical Properties of Different Rank Coal and Their Impact on Fracture Compressibility. Energ. Fuel. 2024, 38, 9515–9528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Li, S.; Shi, X.; Hao, M.; Zhang, Y.; Jiao, T.; Liang, P. Study on the bond cleavage behavior of oxygen-containing structure during pyrolysis upgrading of Zhaotong lignite. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 2024, 182, 106709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, L.; Hao, Y.; Yi, Z.; Qing, Z.; Fu, L.; Ke, Z.; Jun, Z.; Hong, Z.; Ming, Z. Multi—Scale perspective on hydrothermal treatment dewatering of lignite: Synergistic regulation of structural evolution and lightening of pyrolysis tar. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 2025, 192, 107247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiu, R.; Du, J.; Chen, Y.; Xin, L.; Ying, Q. High-efficiency co-liquefaction of brominated epoxy resin and low rank coal in supercritical water: Waste recycling and products upgrading. Process. Saf. Environ. 2024, 192, 1444–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Q.; Wang, L.; Ma, M.; Li, M.; He, L.; Duo, M.; Sun, M. A quantitative investigation on pyrolysis behaviors of metal ion-exchanged coal macerals by interpretable machine learning algorithms. Energy 2024, 300, 131614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tursun, Y.; Wang, K.; Yi, R.; Hairat, A.; Zheng, D.; Mei, Z.; Li, J.; Jian, L.; Yang, L. Catalytic Pyrolysis of Naomaohu Coal Using Combined CaO and Ni/Olivine Catalysts for Simultaneously Improving the Tar and Gas Quality. Energies 2024, 17, 1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Song, H.; Jia, P.; Wang, D. Construction of molecular structure of low/middle coal rank and its adsorption mechanism of CO2 after N/S/P doping. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 112741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Cui, M.; Li, J.; Du, z.; Zhan, X. Experimental investigation and ReaxFF simulation on pore structure evolution mechanism during coalification of coal macromolecules in different ranks. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 30768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luan, P.; Chen, J.; Liu, T.; Wang, J.; Yan, B.; Li, N.; Cui, X.; Chen, G.; Cheng, Z. Ex-situ catalytic fast pyrolysis of waste polycarbonate for aromatic hydrocarbons: Utilizing HZSM-5/modified HZSM-5. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 2024, 182, 106667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhong, Z.; Zheng, X.; Ye, Q.; Li, Y.; Yang, Y. Catalytic pyrolysis of hydrolyzed lignin using HZSM-5/MCM-41 supported transition-metal to produce monocyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 2024, 183, 106819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, J.; Liu, P.; Liu, D.; Lu, X.; Pan, T.; Zhang, D. Effect of Catalysts on the Yields of Light Components and Phenols Derived from Shenmu Coal Low Temperature Pyrolysis. Energy Fuel. 2017, 31, 7033–7041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Bai, Y.; Zhao, R.; Li, F.; Xie, K. Correlation between coal structure and release of the two organic compounds during pyrolysis. Fuel 2015, 145, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Li, Z.; Huang, W.; Yang, J.; Xue, H. Coal pyrolysis characteristics by TG–MS and its late gas generation potential. Fuel 2015, 156, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.; Pereira, A.; Queiróz, D.; Adriana, P.; Vinícius, P.; Amanda, D.; Anne, G. Renewable hydrocarbons via catalytic pyrolysis of sunflower oil using in situ metal-modified MCM-41. J. Porous Mat. 2025, 32, 867–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, H.; Alsaiari, M.; Thao, T.; Nguyen, H.; Nguyen, P.; Dai, V.; Thongthai, W.; Van, C.; Suwadee, K.; Chanatip, S.; et al. High selective hydrocarbon and hydrogen products from catalytic pyrolysis of rice husk: Role of the ordered mesoporous silica derived from rice husk ash for Ni-nanocatalyst performance. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 2024, 178, 106383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, R.; Zheng, X.; Xie, J.; Tang, B.; Li, Z.; Guo, E.; Hu, H.; Jin, L. Hydrogen-donating behavior and hydrogen-shuttling mechanism of liquefaction solvents under Fe- and Ni-based catalysts. Fuel 2024, 368, 131586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Wu, T.; Li, Z.; Yan, J.; Pan, C.; Kang, S.; Lei, Z.; Ren, S.; Shui, H. Boosting conversion efficiency of lignite to oxygen-containing chemicals by thermal extraction and subsequent oxidative depolymerization. Fuel 2022, 308, 122043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Z.; Li, L.; Li, K.; Zuo, S.; Jiang, Z. Study on the effect of acid fracturing fluid on pore structure of middle to high rank coal. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, F.; Li, Q.; Tang, T.; Zhu, J.; Gan, X.; Chen, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S.; Huang, X.; Jia, D. Functional carbon dots from a mild oxidation of coal liquefaction residue. Fuel 2022, 322, 124216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).