Abstract

This work employed peach stones as the precursor material for producing activated carbon (AC-PS). AC-PS was impregnated with H3PO4 and carbonized using a pyrolysis reactor under a reducing atmosphere. The surface area, average pore size, and total pore volume of AC-PS were determined using the BET method. Morphological characteristics of AC-PS were observed through scanning electron microscopy (SEM), the surface composition was identified by energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS), and X-ray diffraction (XRD) analyses were conducted to determine the crystalline structure of carbon. The thermal stability of AC-PS and its interactions with lead and cadmium were analyzed by thermogravimetric analyses (TGA/DTG) and infrared spectra (FTIR), respectively. The Elovich model described the adsorption kinetics of both lead and cadmium, and the Weber and Morris model indicated intraparticle diffusion as the controlling mechanism of the adsorption process. The equilibrium study showed that the Freundlich model was adequate for both ions, with adsorption capacities increasing with temperature, reaching around 150 mg g−1 for lead and 80 mg g−1 for cadmium at 45 °C. Economic analysis indicated costs of $0.25 g−1 and $0.51 g−1 for the removal of lead and cadmium from the contaminated water, respectively.

1. Introduction

Industrial effluents containing heavy metals, particularly lead and cadmium, represent one of the main environmental concerns [1,2]. These metals are widely used in various industrial processes, such as electroplating, battery production, and pigment manufacturing. Inadequate regulation of these activities often results in their release into the environment through industrial effluents, resulting in water and soil contamination and serious risks to human health [3]. Exposure to lead and cadmium is associated with severe health risks, including cardiovascular problems, increased blood pressure, hypertension, reduced kidney function, and reproductive problems [1,4,5]. The World Health Organization establishes strict limits for their concentration in water, reflecting the urgency of effective removal methods. Inadequate wastewater treatment, especially in developing countries, further aggravates contamination, reinforcing the need for low-cost and sustainable technologies [6]. In this context, the present study explores the use of peach-stone-derived activated carbon as a sustainable adsorbent for the removal of Pb(II) and Cd(II).

Among the available methods, adsorption has been considered promising for removing contaminants in aqueous media at low concentrations due to its low cost, simplicity of operation, high efficiency, and the possibility of adsorbent regeneration [7,8,9]. Commercial activated carbon is the most widely used adsorbent because of its porous structure and high adsorption capacity [10,11,12]. However, it is typically derived from relatively expensive precursors, such as coal and wood [11,12].

Consequently, alternative precursors such as agro-industrial wastes and by-products have been studied for adsorbent production. Biochar derived from these materials has shown high removal efficiencies, ranging from 80 to 99% for Cr6+ and 94 to 99% for Pb2+, underscoring its potential as an effective sorbent [13]. Among these, fruit stones stand out due to their availability, low ash content, and suitable hardness [14]. To further enhance their performance, surface modifications have been explored, making biochar-based adsorbents an emerging field of research [15].

Beyond biochar, activated carbon can be produced using two main approaches: physical and chemical activation. Physical activation involves the partial gasification of a carbon-rich precursor with agents such as steam, CO2, or O2, which removes carbon atoms and generates porosity. In chemical activation, the precursor is impregnated with an activating agent and subsequently heated, promoting dehydration and oxidation reactions that induce simultaneous carbonization and activation. Common activating agents include H3PO4, ZnCl2, FeCl3, and KOH. Notably, phosphoric acid produces activated carbons with acidic surface characteristics, which can be advantageous for specific applications [16,17].

Within this context, the present work aimed to produce activated carbon from peach stones derived from food industry waste, employing H3PO4 treatment prior to carbonization. The adsorbent was evaluated for Pb(II) and Cd(II) removal in aqueous media, with adsorption kinetics, equilibrium modeling, and cost estimation analyzed to assess both technical performance and economic viability.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Material

The peach stones used in this study were supplied by food companies located in Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, and consisted of residues from peach processing. They represented a mixture of different peach cultivars. The reagents H3PO4 (98.00 g mol−1, 85%), lead acetate (379.30 g mol−1, purity 99%), and cadmium chloride (201.33 g mol−1, purity 99%) were purchased from Dinâmica (São Paulo, Brazil).

2.2. Preparation of Activated Carbon from Peach Stones (AC-PS)

Activated carbon from peach stones (AC-PS) was produced through a series of steps, including pre-treatment of the precursor material, impregnation with H3PO4, carbonization, washing, and drying. Initially, the peach stones underwent a pre-treatment in which the seeds were crushed in a knife mill using a 1 mm mesh. Then, the seeds were washed with distilled water at 80 °C under constant agitation for 2 h. The washing process was carried out to eliminate impurities and reduce the ash content. Subsequently, the material was dried in an oven at 40 °C for 24 h and sorted using sieves from the Tyler series. Only the fraction passing through a 35-mesh sieve (425 µm) and retained on a 48-mesh sieve (300 µm) was used for the production of the activated carbons.

The material was impregnated with H3PO4 and subsequently subjected to carbonization. For impregnation, 10 g of peach stones were added to 200 mL of H3PO4 solution (50% H3PO4/precursor material, w/w), and the samples were kept under constant agitation at room temperature for 6 h. Following impregnation, the material was filtered and then dried at 110 °C for 24 h. The impregnated samples were carbonized in a quartz tubular reactor (Sanchis, São Paulo, Brazil) under a nitrogen atmosphere at 400 °C for 2 h, using a heating rate of 5 °C min−1. The obtained carbons were treated with HCl (0.5 mol L−1) to remove excess H3PO4. Washing was performed in a reflux system at 95 °C under constant agitation for 30 min. Then, the charcoals were washed with distilled water until they reached a neutral pH and dried at 110 °C for 24 h.

2.3. Characterization of Activated Carbons

The surface area, average pore size, and total pore volume of the AC-PS were measured using nitrogen adsorption/desorption isotherms at 77 K with a high-speed gas sorption analyzer (Nova 4200e Quantachrome Instruments, Boyton Beach, FL, USA). Before the analyses, the samples underwent degassing for 12 h at 573 K. The morphological characteristics of AC-PS were determined using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis (JEOL, JSM 6610LV, Akishima, Tokyo, Japan) at 15 kV. To perform the analysis, the samples were deposited on a stub using double-sided adhesive tape. The elemental composition of the AC-PS surface was identified and mapped by energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS).

Thermal stability of the AC-PS was evaluated using a Shimadzu TGA-60 calorimeter (Kyoto, Japan) via thermogravimetric analysis. The samples were loaded into aluminum pan-type containers, with an empty container serving as the reference. Analysis was carried out in an N2 atmosphere with a gas flow rate of 50 mL min−1, at a temperature range of 25 °C to 500 °C at a heating rate of 10 °C min−1.

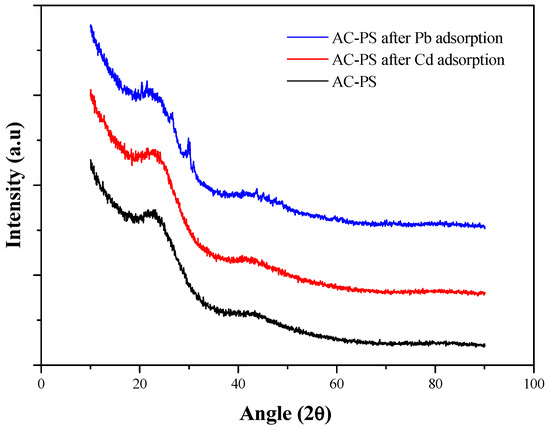

The adsorbent was characterized before and after adsorption by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT–IR) (Prestige 21, 210045, Kyoto, Japan) with KBr pellets and the diffuse reflectance technique, in the range of 500 to 4500 cm−1. Moreover, X-ray diffraction (XRD) analyses were carried out to determine the crystalline structure of carbon. For this, a D8 Advance Bruker diffractometer with copper tube (current of 40 mA, voltage of 40 kV, and wavelength of 1.5418 Å) was used with increments of 0.05° to 2θ between 10° and 90° at room temperature. The beam exposure time for each 0.05° increment was 500 ms. The 2θ angle and the intensity of the diffracted peaks were obtained as variables, and the results obtained were interpreted using a previously known database of diffractograms.

2.4. Adsorption Experiments

Kinetic tests were conducted at 25 °C with an initial concentration of 250 mg L−1 for both lead and cadmium, under agitation speeds of 100, 150, and 200 rpm (Nova Ética, 109-1, São Paulo, Brazil). Aliquots were collected at predetermined intervals (0, 30 s, 1 min, 5 min, 15 min, 30 min, 45 min, and 60 min). For equilibrium studies, experiments were performed at 150 rpm in a thermostatic shaker (Fanem, 315 SE, São Paulo, Brazil) until equilibrium was achieved. Tests were carried out at 15, 25, 35, and 45 °C with initial concentrations of 25, 50, 100, 200, and 300 mg L−1 of Pb(II) and Cd(II) [18].

Afterwards, the adsorbent was removed from the suspension by filtration, and the residual concentrations of lead and cadmium in the solution were determined. In all samples, the concentration was measured by voltammetry. Voltammetric analyses were conducted using a Potentiostat/Galvanostat M204 connected to a Multi-Autolab PGSTAT 204 with Interface IME 663 (Autolab, Utretch, The Netherlands) and Stand 663 VA (Metrohm, Herisau, Switzerland), operated with Nova Software 2.1.3. The setup employed a conventional three-electrode cell consisting of a hanging mercury drop electrode as the working electrode, a platinum rod as the auxiliary electrode, and an Ag/AgCl (3 mol L−1 KCl) electrode as reference [19].

All experiments were carried out in triplicate, with blanks included for control. The adsorption capacity at time t (qt) and equilibrium adsorption capacity (qe) were determined by Equations (1) and (2), respectively [18].

Here, C0 is the initial concentration of lead and cadmium (mg L−1), Ct is the concentration at time of lead and cadmium (mg L−1), Ce is the equilibrium concentration of lead and cadmium (mg L−1), m is the mass of adsorbent (g), and V is the volume of solution (L).

2.5. Kinetic Models

The lead and cadmium adsorption kinetics behavior onto AC-PS were evaluated at different agitation rates by pseudo-first order (PPO) (Equation (3)), pseudo-second order (PSO) (Equation (4)), and Elovich models (Equation (5)), respectively [20,21]:

where qt is the adsorption capacity at time t (mg g−1), k1 and k2 are the rate constants of pseudo-first (min−1) and pseudo-second orders (g mg−1 min−1) models, respectively, and q1 and q2 are the theoretical values for the adsorption capacity (mg g−1).

where a is the initial sorption rate (mg g−1 min−1), and b is the desorption constant (g mg−1).

To evaluate the mass transfer mechanisms involved in lead and cadmium adsorption onto AC-PS at the different agitation rates, the adsorption capacity was plotted against the square root of time. According to the Weber–Morris model, the multilinear profile obtained can be divided into distinct stages. The initial region corresponds to boundary layer diffusion (film diffusion), the second to intraparticle diffusion, and the final stage to equilibrium, in which diffusion slows due to the reduced adsorbate concentration in the solution. This model is given by Equation (6) [22,23].

where kWB is the diffusion rate constant (mg g−1 t−1/2), and C is related to the apparent thickness of the boundary layer of the film.

2.6. Isotherm Models

Equilibrium adsorption isotherms for lead and cadmium on AC-PS were obtained at 15, 25, 35, and 45 °C. The experimental data were fitted using the Henry, Freundlich, and Langmuir models. The Henry model (Equation (7)) is typically applied to dilute solutions and assumes a homogeneous adsorbent surface, where the amount of adsorbate in the solid phase increases linearly with its concentration in the liquid phase.

where qe is the adsorption capacity at equilibrium (mg g−1), is the Henry’s constant (L g−1), and Ce is the concentration of the liquid phase at equilibrium (mg L−1).

The Freundlich model assumes that the adsorbent surface is heterogeneous and can be represented by Equation (8).

where kF is the Freundlich constant ((mg g−1) (L mg−1)−1/n), and 1/n is the heterogeneity factor.

The Langmuir model (Equation (9)) assumes that the adsorbent surface is homogeneous, where the sites are characterized by equal affinity and energy, indicating a monolayer adsorption. Because the adsorbent has a finite number of active sites, saturation of the monolayer occurs as Ce → ∞.

Here, qm is the maximum adsorption capacity (mg g−1), and kL is the Langmuir constant (L mg−1).

2.7. Thermodynamic Parameters

Thermodynamic parameters, including Gibbs free energy change (ΔG, kJ mol−1), enthalpy change (ΔH, kJ mol−1), and entropy change (ΔS, kJ mol−1 K−1), were evaluated to investigate lead and cadmium adsorption onto AC-PS further. These values were calculated using Equations (10) and (11).

where R is the universal gas constant (8.314 J mol−1 K−1), T is the temperature (K), and ρw is the solution density (g L−1). The KD values were determined by qe/Ce ratios obtained by the equilibrium isotherm.

2.8. Regression Analysis

The model parameters were determined by fitting the models to the experimental data using nonlinear regression with the Quasi–Newton estimation method. Calculations were performed with Statistica 7.0 software (Statsoft, OK, USA). The goodness of fit was assessed by the coefficient of determination (R2) and average relative error (ARE).

2.9. Cost Estimation

The overall cost was calculated considering the energy consumed in addition to the cost of precursors. The direct production costs included raw materials, reagents, operating labor, and utilities (electricity), calculated using an adapted cost structure and parameters. Prices for AC-PS and reagents were based on local market values, assuming the material was available on-site. The raw material cost also included general cleaning of the AC-PS waste and transportation to the plant. The utility costs were calculated according to the energetic and process requirements, using an average electricity price of 0.19 $ kWh−1, while operating labor costs were estimated following the “operating labor requirements for chemical process” guidelines [24,25].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of the Obtained Activated Carbons

The raw peach stones were submitted to pyrolysis, resulting in a yield of 35.74%. Table 1 shows the AC-PS characteristics: specific surface area, average pore size, total pore volume, mean particle diameter, sphericity, and density. According to these results and the IUPAC classification, AC-PS can be characterized as a mesoporous material. Other studies have produced and characterized biochar from peach stones, reporting surface area values ranging from 0.3 to 4.4 m2·g−1 [13]. In contrast, activated carbon from peach stones prepared via chemical activation with H3PO4 showed significantly higher surface areas, ranging from 631 to 1180 m2·g−1 [16]. The pyrolysis conditions in this study were similar to those used in the present work; however, the chemical activating agent was applied at an impregnation ratio of up to 4.5:1, compared to a ratio of 1:2 in this study. Physical activation of peach stones with water vapor has been reported to yield activated carbon with a surface area of 846 m2·g−1, whereas using CO2 as the activating agent resulted in values below 500 m2·g−1 [26,27].

Table 1.

Properties of the AC-PS.

The activated carbon synthesized in this study exhibited a low specific surface area compared to typical commercial activated carbons, which generally have surface areas exceeding 1000 m2·g−1. The total pore volume of the synthesized material is lower than that reported for commercial carbons, which typically exhibit total pore volumes of 0.49–0.70 cm3·g−1 and micropore volumes of 0.32–0.50 cm3·g−1 [28]. This suggests that the synthesized material may be suitable for applications where lower adsorption capacities are adequate, such as the removal of heavy metals at lower concentrations or in systems with less stringent adsorption requirements.

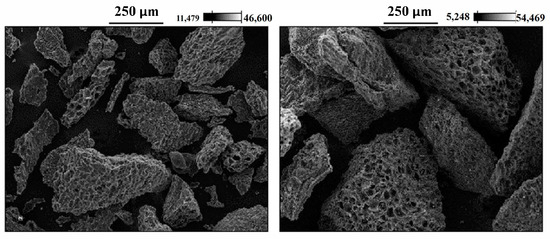

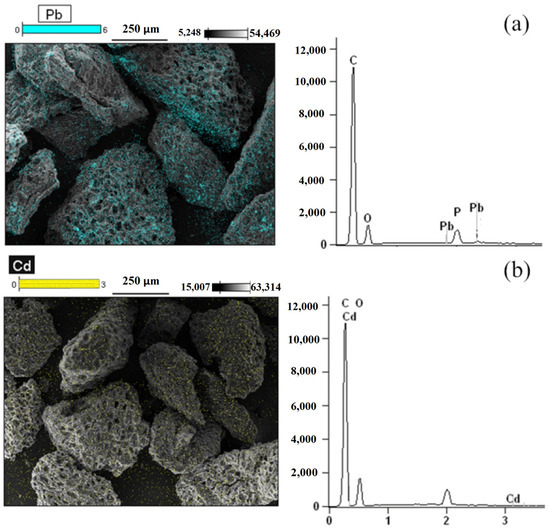

Figure 1 shows the SEM images of AC-PS obtained before adsorption. The figures show that the obtained AC-PS has a rough surface composed of cavities and protuberances. The presence of these protuberances and cavities favors the adsorption operation since they allow the penetration of ions into the solid surface. SEM was also used to identify the presence and the position of the adsorbate in AC-PS after adsorption. Analyzing the spectra presented in Figure 2a,b, it is possible to observe the presence of lead and cadmium, respectively. In all samples, there is also a presence of phosphorus, which remained after the activation step. Although its exact influence was not quantified in this study, the persistent presence of phosphorus may affect the adsorption performance of AC-PS, for instance, by competing with metal ions for active sites or modifying the surface chemistry. SEM images in Figure 2a,b show that the ions tend to deposit homogeneously on the carbon surface.

Figure 1.

SEM image of activated carbon from peach stones (AC-PS) before adsorption.

Figure 2.

SEM images and EDS spectra of activated carbon from peach stones (AC-PS) after adsorption of (a) lead and (b) cadmium.

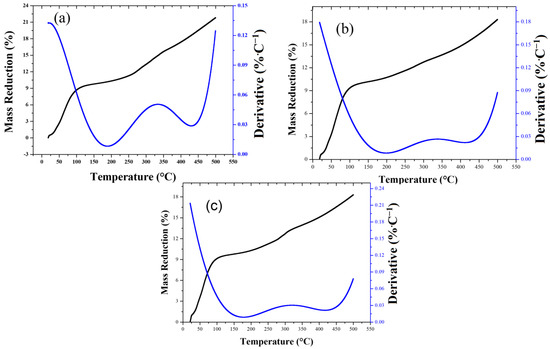

Figure 3 shows the thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) and derivative curves (DTGA) of AC-PS before and after lead and cadmium absorption. Mass loss occurred in distinct temperature ranges: moisture loss (15–150 °C), decomposition of light volatiles (150–300 °C), and decomposition of heavier volatiles and the carbon matrix (300–500 °C). All samples exhibited an initial mass reduction of ~12.5% up to 300 °C, primarily due to moisture and light volatiles. Between 300 and 500 °C, pristine AC-PS lost 21.8% of its mass, whereas AC-PS after metal adsorption showed slightly lower loss (18.3%), indicating that adsorbed Pb2+ and Cd2+ enhance thermal stability. This effect is likely due to interactions between metal ions and surface functional groups, making the carbon matrix more resistant to degradation. DTGA peaks support this interpretation, showing that the maximum rates of mass loss are slightly lower or shifted to higher temperatures for AC-PS after metal adsorption, consistent with enhanced resistance to thermal degradation. Similar behavior was reported by Kozyatnyk et al. [27] for biochars from wheat straw, softwood, and peach stones produced at 550 °C. They observed mass losses of 16 to 18.7%, which were attributed to incomplete carbonization during pyrolysis.

Figure 3.

TGA and derivative (DTGA) curves of activated carbon from peach stones (AC-PS) before (a) and after lead (b) and cadmium (c) adsorption.

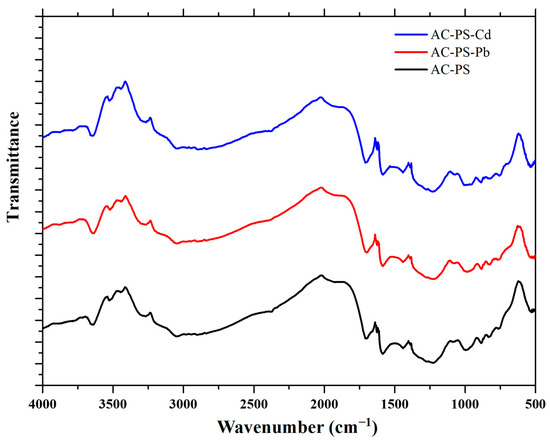

FTIR analysis was performed to verify changes in functional groups caused by the adsorption process and to identify the functional groups on the AC-PS surface that can interact with the ions. Figure 4 shows the FTIR spectra of the AC-PS before and after adsorption. The band at 3300 cm−1 corresponds to O-H stretching and can be attributed to the remaining lignocellulosic material after pyrolysis. The band at 1560 cm−1 is characteristic of quinone groups’ C–O stretching. The bands between 700 cm−1 and 1100 cm−1 may indicate the presence of aromaticity due to the carbonization process [18,29].

Figure 4.

FTIR of activated carbon from peach stones (AC-PS) before ( and after lead (AC-PS-Pb) and cadmium (AC-PS-Cd) adsorption.

No noticeable spectral changes were observed after adsorption. This is not uncommon in studies of heavy metal adsorption and may suggest that the adsorption process is primarily governed by physical interactions, such as electrostatic forces, hydrogen bonding, and cation–π interactions, rather than strong chemical bond formation. This interpretation aligns with previous studies on biochars and polymeric adsorbents, where small or undetectable changes in FTIR spectra were reported [30,31]. In such cases, the proportion of functional groups directly involved in adsorption may be small relative to the total, or the interactions may be too weak to produce detectable shifts.

Figure 5 presents the X-ray diffractograms for AC-PS before and after adsorption. Although there is a slight difference in intensity observed in the region between approximately 10° and 25°, the diffractometric data obtained after the adsorption process for both lead and cadmium show great similarity with those obtained before the process, suggesting that there were no changes in the carbon structure; the diffractograms presented two prominent closely situated in the same region (22° and 42°), corresponding to the crystallographic planes (002) and (101), respectively, observed in similar materials [32,33]. The crystalline structure of the AC-PS obtained in this work can be attributed to a hexagonal structure typical of carbon-based materials. In this structure, the adjacent crystallographic planes (002) and (101) are separated by interplanar distances equal to 3.827 Å and 2.107 Å, respectively.

Figure 5.

X-ray diffraction of activated carbon from peach stones (AC-PS) before and after lead and cadmium adsorption.

3.2. Kinetic Study

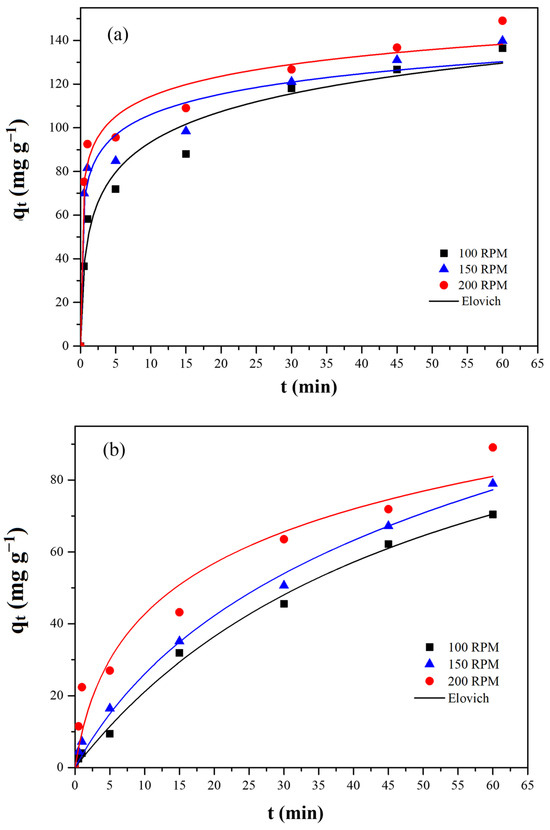

The kinetic curves obtained for lead and cadmium adsorption are shown in Figure 6a and Figure 6b, respectively. For lead, it was observed that the adsorption was initially fast, reaching about 60% of the adsorbent saturation in the first 5 min of the experiment for all absorption rates studied. After this time, a gradual decrease in the adsorption rate was observed. For cadmium (Figure 6b), on the other hand, a slower adsorption rate was observed at the beginning of the operation, with a gradual reduction in the adsorption rate throughout the experiment. It can be observed that 60% of adsorbent saturation occurred at 25 min of the experiment at 200 rpm.

Figure 6.

Adsorption capacity of activated carbon from peach stones (AC-PS) for (a) lead and (b) cadmium over time under various agitation rates.

This significant difference in adsorption speed between Pb(II) and Cd(II) can be attributed to their ionic properties and interaction mechanisms with the AC-PS surface. Pb(II) typically has a smaller hydrated radius and lower hydration energy than Cd(II) [34,35], which facilitates faster diffusion into the porous structure and stronger interactions with active sites. Electrostatic interactions and surface polarization effects, as well as residual phosphorus groups on AC-PS, may further enhance the preferential adsorption of Pb(II) [36]. According to the Hard and Soft Acids and Bases principle, Cd(II) is classified as a soft Lewis acid, whereas Pb(II) is borderline or soft due to its polarizability [37], suggesting a stronger affinity of Pb(II) for electron-donating functional groups on AC-PS, such as hydroxyl, carboxyl, and phosphorus residues [38].

The influence of agitation rate was also evident, particularly for cadmium. An increase in agitation from 100 rpm to 200 rpm significantly enhanced the adsorption rate for Cd(II), reducing the time to reach 60% saturation. This observation confirms that increasing the agitation rate effectively decreases the thickness of the external mass transfer boundary layer, thereby reducing resistance to external mass transfer and facilitating the migration of adsorbate molecules to the AC-PS surface [39].

To better understand the kinetic behavior of the adsorption, the pseudo-first order, pseudo-second order, and Elovich models were fitted to experimental data (Figure 5). The kinetic parameters for lead and cadmium adsorption are shown in Table 2 and Table 3, respectively. For lead (Table 2), the only model that presented a good fit to experimental data was the Elovich model. For cadmium (Table 3), on the other hand, all the kinetic models used presented a good fit. However, due to the lower relative average error values, the Elovich model was chosen to describe experimental data. Elovich parameters show that the initial adsorption rate (a) of Pb(II) at 200 rpm is higher than that of Cd(II), confirming the faster uptake of lead. Similarly, the b parameter, which reflects the extent of surface coverage, is substantially larger for Pb(II) than for Cd(II). Regarding the effect of agitation, both a and b increase with increasing stirring rate, demonstrating that higher agitation (200 rpm) favors adsorption by reducing the external mass transfer resistance.

Table 2.

Kinetic parameters of lead adsorption onto activated carbon from peach stones (AC-PS).

Table 3.

Kinetic parameters of cadmium adsorption onto AC-PS.

Inyang et al. [40] also concluded that the Elovich model adequately describes the sorption of lead and cadmium onto minerals. However, other authors concluded that other models were more suitable to describe experimental data. These differences may be explained mainly by the different types of adsorbents. Gao et al. [41] and Kavisri et al. [42] evaluated the pseudo-first order and the pseudo-second order models to predict the cadmium adsorption kinetics of biochar derived from selenium-rich straw and chitosan, respectively. According to the authors, both models exhibited a good fit with experimental data. Xu et al. [20] and Chukwu Onu et al. [43] evaluated different adsorption kinetics models for lead and cadmium adsorption and concluded that the pseudo-second order model was the most adequate one to represent experimental data.

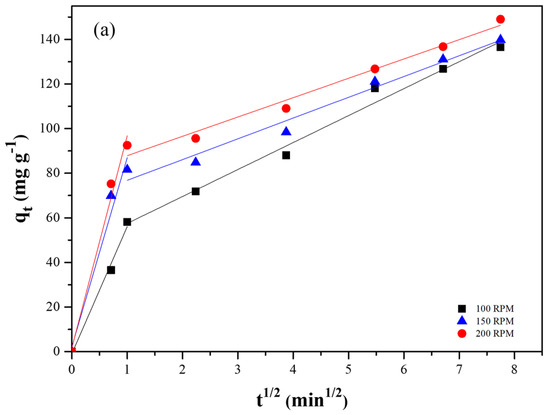

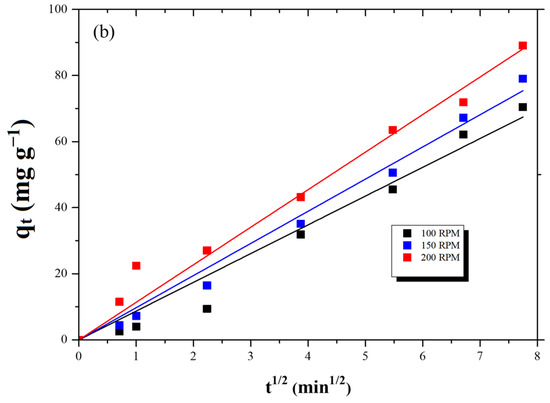

3.3. Weber–Morris Analysis

The Weber–Morris model was used to evaluate the film and intraparticle diffusion steps of adsorption over time, and the effect of the stirring rate on each step. Weber and Morris graphs for the adsorption of lead and cadmium at the three agitation rates studied are shown in Figure 7a and Figure 7b, respectively. For Pb(II), the plots clearly exhibit two distinct linear regimes, indicating that both film diffusion (external mass transfer) and intraparticle diffusion contribute to the overall adsorption process. The initial, steeper linear segment corresponds to film diffusion, where Pb(II) ions are transported from the bulk solution to the external surface of the AC-PS. For Cd(II), however, for each agitation rate, only one dominant linear segment was verified. This suggests that for cadmium, intraparticle diffusion is the primary rate-controlling step throughout the adsorption operation, or that film diffusion is so rapid that it does not present a distinct rate-limiting phase compared to intraparticle diffusion.

Figure 7.

Weber and Morris model plot for (a) lead and (b) cadmium adsorption.

The Weber and Morris model was adjusted to the experimental data, and the film and intraparticle diffusion constants (KWB1 and KWB2, respectively) are presented in Table 4. The values of the coefficient of determination indicate that the model provides a good fit for the portions at all agitation rates for both adsorbates (R2 > 0.9). The increase in the agitation rate led to an increase in the diffusion constant of the film region (KWB1) for lead. This occurred because higher agitation rates decreased the external mass transfer resistance, facilitating the diffusion of adsorbate molecules to the adsorbent surface, leading to an increase in the adsorption rate.

Table 4.

Weber and Morris parameters for the adsorption of lead and cadmium.

Regarding the intraparticle diffusion constant (KWB2), the values presented in Table 4 for lead show that this parameter was independent of the agitation rate. This result was expected since the intraparticle diffusion depends mainly on the surface properties of the adsorbent. Therefore, it can be inferred that the adsorption of lead was controlled by intraparticle diffusion (KWB1 > KWB2). This conclusion finds support in the observation that the initial linear segment of the Weber and Morris plot intersects the origin, as depicted in Figure 6 [22,44].

The differences in adsorption kinetics between Pb(II) and Cd(II) can be directly linked to their ionic properties and interactions with the AC-PS surface. Pb(II), with a smaller hydrated radius and stronger affinity for electron-donating surface groups, diffuses more readily both along the pore surfaces and within the pores, resulting in a clear distinction between film and intraparticle diffusion. In contrast, Cd(II) exhibits a larger hydrated radius and weaker interactions with surface functional groups, which slows intraparticle diffusion and makes it the predominant rate-limiting step, leading to slower overall adsorption.

3.4. Equilibrium and Thermodynamic Studies

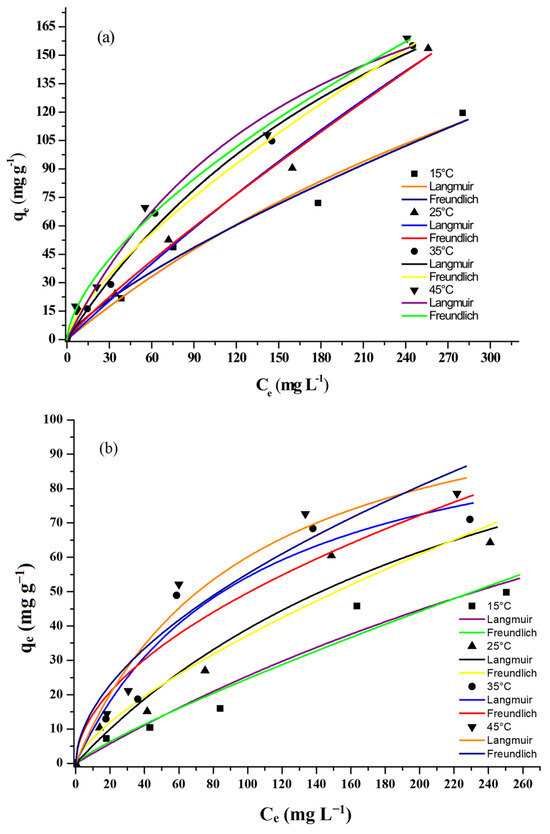

The equilibrium adsorption isotherms for lead and cadmium on AC-PS were determined at 15 °C, 25 °C, 35 °C, and 45 °C, employing initial solution concentrations of 25, 50, 100, 200, and 300 mg L−1 for both lead and cadmium. The corresponding curves are illustrated in Figure 8a,b. The results show that equilibrium adsorption capacity values increased with the increase in temperature. The highest values were around 150 mg g−1 and 80 mg g−1 for lead and cadmium, respectively, and were obtained at 45 °C. These results suggest that the adsorption of both lead and cadmium on AC-PS was endothermic. This increase in adsorption capacity with temperature is related to the diffusion and accessibility of ions into the porous structure, as well as their interactions with surface functional groups.

Figure 8.

Equilibrium adsorption capacity of activated carbon from peach stones (AC-PS) for (a) lead and (b) cadmium.

The Henry, Freundlich, and Langmuir isotherm models were fitted to the experimental equilibrium data, and the obtained parameters are presented in Table 5 and Table 6. The highest coefficient of determination (R2) and the lowest average relative error (ARE) values were obtained for the Freundlich model. Thus, this model was chosen to represent the adsorption equilibrium data for lead and cadmium on AC-PS, indicating that the adsorption likely occurs on a heterogeneous surface with sites of varying affinities [15,44,45]. The higher maximum adsorption capacity for Pb(II) compared to Cd(II) across all temperatures highlights a stronger affinity of the AC-PS for lead ions, which is consistent with the faster diffusion and intraparticle transport observed in the Weber–Morris analysis.

Table 5.

Equilibrium parameters of lead adsorption on activated carbon from peach stones (AC-PS).

Table 6.

Equilibrium parameters of cadmium adsorption on activated carbon from peach stones (AC-PS).

To understand the thermodynamic behavior of lead and cadmium adsorption on AC-PS, the thermodynamic parameters of Gibbs free energy variation (ΔG°), enthalpy variation (ΔH°), and entropy variation (ΔS°) were determined and are presented in Table 7. The negative values of Gibbs free energy variation show that the adsorption of lead and cadmium was a spontaneous phenomenon. The most negative value of Gibbs free energy variation found for the temperature of 45 °C indicates that adsorption was favored with the increase in temperature.

Table 7.

Thermodynamic parameters of lead and cadmium adsorption on AC-PS.

The positive values of adsorption enthalpy change indicate that the adsorption of both lead and cadmium was endothermic. The order of magnitude of these values suggests physisorption, as chemically mediated adsorption typically leads to more significant changes in internal energy. The difference in ΔH° values between Pb(II) and Cd(II) further underscores their distinct energetic requirements for adsorption, with Cd(II) requiring more energy input, which may be linked to its larger hydrated ionic radius and potentially weaker interactions with the AC-PS surface compared to Pb(II).

The positive adsorption entropy changes indicate that a disorder at the solid–liquid interface increased after adsorption. It is verified that only entropy contributes to obtaining negative values of the Gibbs free energy variation, which shows that the adsorption of lead and cadmium in the obtained AC-PS is entropically controlled. Similar results were found by other authors who evaluated lead and cadmium adsorption by modified biochar [46,47,48]. The higher ΔS° for Cd(II) compared to Pb(II) might imply a greater degree of disorder created during Cd(II) adsorption, possibly due to the displacement of a larger number of water molecules from its hydration shell or a more significant rearrangement of the adsorbent–adsorbate system.

3.5. Cost Estimation

The results showed that 0.05 kg of AC-PS was used to prepare 0.178 kg of adsorbent with the consumption of 0.14 kg of H3PO4 and 0.04 kg of nitrogen. The direct product cost obtained for the preparation of AC-PS adsorbent was $0.039 g−1. Therefore, based on the results of adsorption capacity, the economic analysis revealed a cost of $0.25 g−1 and $0.51 g−1 for lead and cadmium removal from the contaminated water. This difference reflects the lower adsorption capacity (Figure 6) of AC-PS for Cd2+. While Pb2+ removal appears economically more promising for large-scale applications, Cd2+ removal shows higher costs, requiring process and/or adsorbent optimization to become more competitive.

4. Conclusions

The obtained AC-PS exhibited favorable characteristics for use as an adsorbent, with a surface area of 50 m2 g−1 and an average pore size of 23 Å. These features indicated a mesoporous structure with rough surface comprising cavities and protuberances. The adsorption of lead by AC-PS reached approximately 60% saturation within 5 min, while cadmium achieved the same level after 25 min. Experimental data analysis using the Weber and Morris model demonstrated that film and intraparticle diffusion occur in the adsorption of lead and cadmium. Moreover, an increase in agitation rate caused an increase in the film diffusion constant, underlining the influence of agitation on the adsorption process. The equilibrium study revealed an enhancement in lead and cadmium adsorption capacities with the increase in temperature, reaching around 150 mg g−1 and 80 mg g−1 for lead and cadmium, respectively, at 45 °C. The Freundlich model provided the best fit for the experimental data, and the adsorption of both lead and cadmium was spontaneous and endothermic. The values of enthalpy suggested the occurrence of physical adsorption, while the positive entropy values indicated an entropically controlled adsorption process. Based on the results of the adsorption capacity, the economic analysis revealed that the cost for lead and cadmium removal was $0.25 g−1 and $0.51 g−1, respectively, emphasizing the cost-effectiveness of the developed AC-PS for environmental remediation purposes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.M.C. and T.R.S.C.J.; methodology, G.M.C. and A.P.O.; validation, G.M.C., L.A., A.P.O., D.P.J., N.S.J., D.D., and R.P.; formal analysis, G.M.C., L.A., A.P.O., D.P.J., N.S.J., D.D., and R.P.; investigation, G.M.C. and T.R.S.C.J.; resources, L.A.d.A.P.; data curation, G.M.C., N.S.J.; writing—original draft preparation, G.M.C.; writing—review and editing, D.P.J., A.I., and T.R.S.C.J.; visualization, T.R.S.C.J.; supervision, T.R.S.C.J.; project administration, T.R.S.C.J.; funding acquisition, L.A.d.A.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES)/Brazil, Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq)/Brazil, Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do RS (FAPERGS)/Brazil, Secretaria de Desenvolvimento, Ciência e Tecnologia/RS/Brazil (projects DCIT 70/2015 and DCIT 77/2016).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the results of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Nanosul/FURG of the Associate Laboratory of the National System of Laboratories in Nanotechnology (SisNANO)/Brazil and Integrated Analysis Center of the Federal University of Rio Grande (CIA)/FURG/Brazil for research support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Howard, J.A.; David, L.; Lux, F.; Tillement, O. Low-Level, Chronic Ingestion of Lead and Cadmium: The Unspoken Danger for at-Risk Populations. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 478, 135361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeschke, D.P.; Merlo, E.A.; Mercali, G.D.; Rech, R.; Marczak, L.D.F. The Effect of Temperature and Moderate Electric Field Pre-Treatment on Carotenoid Extraction from Heterochlorella Luteoviridis. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 54, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djulejic, V.; Petrovic, B.; Jevtic, J.; Vujacic, M.; Clarke, B.L.; Cirovic, A.; Cirovic, A. The Role of Cadmium in the Pathogenesis of Myeloid Leukemia in Individuals with Anemia, Deficiencies in Vitamin D, Zinc, and Low Calcium Dietary Intake. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2023, 79, 127263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiek, S.S.; Mani, M.S.; Kabekkodu, S.P.; Dsouza, H.S. Health Repercussions of Environmental Exposure to Lead: Methylation Perspective. Toxicology 2021, 461, 152927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaefer, H.R.; Flannery, B.M.; Crosby, L.; Jones-Dominic, O.E.; Punzalan, C.; Middleton, K. A Systematic Review of Adverse Health Effects Associated with Oral Cadmium Exposure. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2022, 134, 105243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solhtalab, M.; Majdinasab, M.; Zarei, S.; Majdinasab, E. Development of a Simple and Rapid Paper-Based Dipstick Test Strip for the Colorimetric Detection of Lead and Cadmium in Water. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2025, 19, 100867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, M.; Rownok, M.H.; Sabrin, M.; Rahaman, M.H.; Alam, S.M.N. A Review on Experimental Chemically Modified Activated Carbon to Enhance Dye and Heavy Metals Adsorption. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2022, 6, 100382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Wu, B.; Wang, T.; Yılmaz, M.; Sharma, G.; Kumar, A.; Shi, H. Multi-Mechanism Synergistic Adsorption of Lead and Cadmium in Water by Structure-Functionally Adapted Modified Biochar: A Review. Desalination Water Treat. 2025, 322, 101156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhshandeh, A.; Segala, M. Adsorption of Polyelectrolytes on Charged Microscopically Patterned Surfaces. J. Mol. Liq. 2019, 294, 111673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somasundaram, S.; Sekar, K.; Gupta, V.K.; Ganesan, S. Synthesis and Characterization of Mesoporous Activated Carbon from Rice Husk for Adsorption of Glycine from Alcohol-Aqueous Mixture. J. Mol. Liq. 2013, 177, 416–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dizbay-Onat, M.; Vaidya, U.K.; Lungu, C.T. Preparation of Industrial Sisal Fiber Waste Derived Activated Carbon by Chemical Activation and Effects of Carbonization Parameters on Surface Characteristics. Ind. Crops Prod. 2017, 95, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bind, A.; Goswami, L.; Prakash, V. Comparative Analysis of Floating and Submerged Macrophytes for Heavy Metal (Copper, Chromium, Arsenic and Lead) Removal: Sorbent Preparation, Characterization, Regeneration and Cost Estimation. Geol. Ecol. Landsc. 2018, 2, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cârjilă (Mihalache), E.R.; Orbuleț, O.D.; Bosomoiu, M.; Modrogan, C.; Tanasă, E.; Dăncilă, A.M.; Gârleanu, G. Agrifood Waste Valorization: Development of Biochar from Peach Kernel or Grape Pits for Cr6+ Removal from Plating Wastewater. Materials 2025, 18, 4151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uysal, T.; Duman, G.; Onal, Y.; Yasa, I.; Yanik, J. Production of Activated Carbon and Fungicidal Oil from Peach Stone by Two-Stage Process. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2014, 108, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Lawluvy, Y.; Shi, Y.; Ighalo, J.O.; He, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yap, P.S. Adsorption of Cadmium and Lead from Aqueous Solution Using Modified Biochar: A Review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 106502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harabi, S.; Guiza, S.; Álvarez-Montero, A.; Gómez-Avilés, A.; Bagané, M.; Belver, C.; Bedia, J. Adsorption of Pesticides on Activated Carbons from Peach Stones. Processes 2024, 12, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinzaei, B.; Hadianfard, M.J.; Ruiz-Rosas, R.; Rosas, J.M.; Rodríguez-Mirasol, J.; Cordero, T. Effect of Heating Rate and H3PO4 as Catalyst on the Pyrolysis of Agricultural Residues. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2022, 168, 105724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadaval, T.R.S.; Dotto, G.L.; Seus, E.R.; Mirlean, N.; de Almeida Pinto, L.A. Vanadium Removal from Aqueous Solutions by Adsorption onto Chitosan Films. Desalination Water Treat. 2016, 57, 16583–16591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerhardt, R.; Farias, B.S.; Moura, J.M.; de Almeida, L.S.; da Silva, A.R.; Dias, D.; Cadaval, T.R.S.; Pinto, L.A.A. Development of Chitosan/Spirulina sp. Blend Films as Biosorbents for Cr6+ and Pb2+ Removal. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 155, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, D.; Ni, X.; Kang, J.; He, B.; Zuo, Y.; Mosa, A.A.; Yin, X. Mechanisms of Cadmium Adsorption by Ramie Nano-Biochar with Different Aged Treatments. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2023, 193, 105175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, C.P.; Moreira, L.M.K.; Alves, S.S.; Cadaval, T.R.S., Jr.; Pinto, L.A.A. Anthocyanins Concentration by Adsorption onto Chitosan and Alginate Beads: Isotherms, Kinetics and Thermodynamics Parameters. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 166, 934–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, W.J., Jr.; Morris, J.C. Kinetics of Adsorption on Carbon from Solution. J. Sanit. Eng. Div. 1963, 89, 31–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dotto, G.L.; Cadaval, T.R.S.; Pinto, L.A.A. Preparation of Bionanoparticles Derived from Spirulina platensis and Its Application for Cr (VI) Removal from Aqueous Solutions. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2012, 18, 1925–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piasecki, W.; Rudziński, W. Application of the Statistical Rate Theory of Interfacial Transport to Investigate the Kinetics of Divalent Metal Ion Adsorption onto the Energetically Heterogeneous Surfaces of Oxides and Activated Carbons. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2007, 253, 5814–5817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalvand, A.; Gholami, M.; Joneidi, A.; Mahmoodi, N.M. Dye Removal, Energy Consumption and Operating Cost of Electrocoagulation of Textile Wastewater as a Clean Process. CLEAN—Soil Air Water 2011, 39, 665–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Rodríguez, S.; Sebastián, D.; Alegre, C.; Tsoncheva, T.; Petrov, N.; Paneva, D.; Lázaro, M.J. Biomass Waste-Derived Nitrogen and Iron Co-Doped Nanoporous Carbons as Electrocatalysts for the Oxygen Reduction Reaction. Electrochim. Acta 2021, 387, 138490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozyatnyk, I.; Oesterle, P.; Wurzer, C.; Mašek, O.; Jansson, S. Removal of Contaminants of Emerging Concern from Multicomponent Systems Using Carbon Dioxide Activated Biochar from Lignocellulosic Feedstocks. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 340, 125561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morlay, C.; Joly, J.-P. Contribution to the Textural Characterisation of Filtrasorb 400 and Other Commercial Activated Carbons Commonly Used for Water Treatment. J. Porous Mater. 2010, 17, 535–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lütke, S.F.; Igansi, A.V.; Pegoraro, L.; Dotto, G.L.; Pinto, L.A.A.; Cadaval, T.R.S. Preparation of Activated Carbon from Black Wattle Bark Waste and Its Application for Phenol Adsorption. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 103396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Jin, F.; McMillan, O.; Al-Tabbaa, A. Qualitative and Quantitative Characterisation of Adsorption Mechanisms of Lead on Four Biochars. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 609, 1401–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tenea, A.-G.; Dinu, C.; Rus, P.A.; Ionescu, I.A.; Gheorghe, S.; Iancu, V.I.; Vasile, G.G.; Pascu, L.F.; Chiriac, F.L. Exploring Adsorption Dynamics of Heavy Metals onto Varied Commercial Microplastic Substrates: Isothermal Models and Kinetics Analysis. Heliyon 2024, 10, e35364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, G.H.; Lee, J.W.; Choi, J.H.; Kang, Y.C.; Roh, K.C. Efficient Utilization of Lignin Residue for Activated Carbon in Supercapacitor Applications. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2022, 284, 126073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, J.M.; Lütke, S.F.; Igansi, A.V.; Franco, D.S.P.; Vicenti, J.R.M.; Dotto, G.L.; Pinto, L.A.A.; Cadaval, T.R.S.; Felipe, C.A.S. Mass Transfer and Equilibrium Modelings of Phenol Adsorption on Activated Carbon from Olive Stone. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2024, 680, 132628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslova, M.; Ivanenko, V.; Yanicheva, N.; Gerasimova, L. The Effect of Heavy Metal Ions Hydration on Their Sorption by a Mesoporous Titanium Phosphate Ion-Exchanger. J. Water Process Eng. 2020, 35, 101233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheela, T.; Nayaka, Y.A. Kinetics and Thermodynamics of Cadmium and Lead Ions Adsorption on NiO Nanoparticles. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 191, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhshandeh, A. Theoretical Investigation of a Polarizable Colloid in the Salt Medium. Chem. Phys. 2018, 513, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, R.G. Hard and Soft Acids and Bases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1963, 85, 3533–3539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Chen, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; Yang, K.; Chen, L. The Adsorption Characteristics of Phosphorus-Modified Corn Stover Biochar on Lead and Cadmium. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen Gupta, S.; Bhattacharyya, K.G. Kinetics of Adsorption of Metal Ions on Inorganic Materials: A Review. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2011, 162, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inyang, H.I.; Onwawoma, A.; Bae, S. The Elovich Equation as a Predictor of Lead and Cadmium Sorption Rates on Contaminant Barrier Minerals. Soil Tillage Res. 2016, 155, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Shan, D.; He, J.; Huang, T.; Mao, Y.; Tan, H.; Shi, H.; Li, T.; Xie, T. Effects and Mechanism on Cadmium Adsorption Removal by CaCl2-Modified Biochar from Selenium-Rich Straw. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 370, 128563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavisri, M.; Abraham, M.; Namasivayam, S.K.R.; Aravindkumar, J.; Balaji, D.; Sathishkumar, R.; Sigamani, S.; Srinivasan, R.; Moovendhan, M. Adsorption Isotherm, Kinetics and Response Surface Methodology Optimization of Cadmium (Cd) Removal from Aqueous Solution by Chitosan Biopolymers from Cephalopod Waste. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 335, 117484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chukwu Onu, D.; Kamoru Babayemi, A.; Chinedu Egbosiuba, T.; Onyinye Okafor, B.; Jacinta Ani, I.; Mustapha, S.; Oladejo Tijani, J.; Chukwuemeke Ulakpa, W.; Eguono Ovuoraye, P.; Saka Abdulkareem, A. Isotherm, Kinetics, Thermodynamics, Recyclability and Mechanism of Ultrasonic Assisted Adsorption of Methylene Blue and Lead (II) Ions Using Green Synthesized Nickel Oxide Nanoparticles. Environ. Nanotechnol. Monit. Manag. 2023, 20, 100818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Xing, Y.; Liu, S.; Tan, S.; Huang, Q.; Luo, X.; Chen, W. A Longer Biodegradation Process Enhances the Cadmium Adsorption of the Biochar Derived from a Manure Mix. Biomass Bioenergy 2023, 173, 106787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Zhao, X.; Jiao, J.; Li, Y.; Wei, M. Surface-Modified Biochar with Polydentate Binding Sites for the Removal of Cadmium. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Zeng, G.; Liang, J.; Song, B.; Wei, X. Alginate-Modified Biochar Derived from Ca(II)-Impregnated Biomass: Excellent Anti-Interference Ability for Pb(II) Removal. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2018, 165, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Lin, H.; He, Y.; Li, B.; Dong, Y.; Wang, L. Efficient Simultaneous Removal of Cadmium and Arsenic in Aqueous Solution by Titanium-Modified Ultrasonic Biochar. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 284, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yue, X.; Xu, W.; Zhang, H.; Li, F. Amino Modification of Rice Straw-Derived Biochar for Enhancing Its Cadmium (II) Ions Adsorption from Water. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 379, 120783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).