Abstract

Technology-driven agriculture, or precision agriculture (PA), is indispensable in the contemporary world due to its advantages and the availability of technological innovations. Particularly, early disease detection in agricultural crops helps the farming community ensure crop health, reduce expenditure, and increase crop yield. Governments have mainly used current systems for agricultural statistics and strategic decision-making, but there is still a critical need for farmers to have access to cost-effective, user-friendly solutions that can be used by them regardless of their educational level. In this study, we used four apple leaf diseases (leaf spot, mosaic, rust and brown spot) from the PlantVillage dataset to develop an Automated Agricultural Crop Disease Identification System (AACDIS), a deep learning framework for identifying and categorizing crop diseases. This framework makes use of deep convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and includes three CNN models created specifically for this application. AACDIS achieves significant performance improvements by combining cascade inception and drawing inspiration from the well-known AlexNet design, making it a potent tool for managing agricultural diseases. AACDIS also has Region of Interest (ROI) awareness, a crucial component that improves the efficiency and precision of illness identification. This feature guarantees that the system can quickly and accurately identify illness-related areas inside images, enabling faster and more accurate disease diagnosis. Experimental findings show a test accuracy of 99.491%, which is better than many state-of-the-art deep learning models. This empirical study reveals the potential benefits of the proposed system for early identification of diseases. This research triggers further investigation to realize full-fledged precision agriculture and smart agriculture.

1. Introduction

Technology innovations in terms of machine learning and deep learning paved the way for unprecedented use cases. In addition, Internet of Things (IoT) technology enables the integration of digital and physical worlds [1]. This proposition has already been realized positively, and many IoT use cases have emerged. One such use case of IoT is known as precision agriculture or precision farming [2]. The usage of ML and deep learning in precision farming has increased, as AI-enabled approaches deal with real-world problems such as disease prediction. Smart farming, as explored in [3,4,5,6], involves the integration of IoT technologies to improve agricultural productivity. In recent developments, both IoT and AI have been widely adopted in smart agriculture solutions [6,7,8].

Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and their variants are widely used in data analytics to derive BI. They are widely used along with IoT integration for precision farming. Villa-Henriksen et al. [9] explored the possibilities in technology-driven farming with IoT and its related networks like Wireless Sensor Networks (WSNs). Elijah et al. [7] focused on the integration of IoT with agriculture and the utility of data analytics in order to find intelligence for making expert decisions. They explored data collection, usage of IoT, data analytics and visualization. Davare and Hajare [8] studied the use of IoT for monitoring crops and their growth. Tegegne et al. [10] focused on IoT usage in agriculture in Ethiopia. They explored the usage of IoT along with Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) technology and sensors. Tao et al. [6] investigated different ways in which IoT can be used in agriculture and related operations. A survey of the literature offers some significant findings, especially about the ways in which IoT and AI tools support agricultural surveillance, disease diagnosis, and precision farming. First, IoT plays a crucial role in precision farming. Second, ML and deep learning methods can be used in order to acquire intelligence pertaining to the early detection of plant diseases. Third, the integration of IoT with agriculture has many advantages, such as disease monitoring. The combination of IoT-enabled image capture and deep learning classifiers facilitates ongoing, location-independent disease surveillance. While our current trials rely on datasets, the AACDIS framework is crafted for real-time application via IoT-based camera networks, enabling immediate disease diagnosis from images streamed directly from the field [6,7]. However, it is ascertained that there is a need for a comprehensive framework based on deep learning for automatic crop disease identification and classification. Our contributions in this paper are as follows.

This study proposes AACDIS, a deep learning framework for automated crop disease detection, featuring three novel CNN models: (1) an advanced CNN with AlexNet-inspired architecture, (2) a feature-engineered extension, and (3) an ROI-aware model. The system was evaluated on the PlantVillage dataset [11] to demonstrate superior accuracy over state-of-the-art methods.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 reviews literature pertaining to deep learning models for crop disease detection. Section 3 presents the materials and methods covering the proposed framework and underlying deep learning models. Section 4 presents experimental results. Section 5 concludes the paper and gives directions for the future scope of the research.

2. Related Work

This section reviews the literature on existing methods for the detection of plant diseases like scab and rust that cause significant yield losses globally. Early detection via IoT and deep learning is critical for precision agriculture as demonstrated in rust resistance monitoring studies. One of the best use cases of IoT is precision agriculture where technology drives actions. Zhao et al. [1] proposed an automatic crop disease prediction model based on CNN and agricultural IoT. It has a novel mechanism known as “Multi-Context Fusion Network (MCFN)” which improves discriminative power of their method. Their model outperforms existing CNNs such as VGG16 and AlexNet. Naga Subramanian et al. [2] developed an IoT-, CNN-, and ensemble-based classification model for building a crop disease monitoring system. They intended to improve it with more deep learning approaches and a broader range of plants. Boursianis et al. [3] presented a review of IoT-enabled methods for farming, including research on IoT and the role of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) in precision agriculture. Gao et al. [12] explored UAVs and IoT technology for pest and disease monitoring in agriculture. They incorporated solar power generation in order to have a sustainable solution. Guo and Zhong [13] proposed a system for monitoring agricultural fields using IoT technology. The system was designed as an information-based intelligent approach for decision-making. Kitpo et al. [14] proposed a system for monitoring tomato crops using deep learning and IoT with bot notification services.

Friha et al. [4] investigated smart agriculture using the Internet of Things and related technologies. They focused on the application of fog computing and edge computing for IoT-based workflow applications. Pawara et al. [15] proposed a system for monitoring pomegranate crop diseases using IoT and ML. Sinha and Dhanalakshmi [5] investigated the challenges associated with implementing IoT for smart agriculture. They also highlighted the importance of ML models for precision agriculture. Villa-Henriksen et al. [16] explored the possibilities in technology-driven farming with IoT and its related networks like Wireless Sensor Networks (WSNs). Elijah et al. [7] focused on IoT integration in agriculture and the use of data analytics to derive intelligence for expert decision-making. They explored data collection, usage of IoT, data analytics and visualization. Davare and Hajare [8] studied IoT usage for monitoring crops and their growth. Tegegne et al. [10] focused on IoT usage in agriculture in Ethiopia. They explored the usage of IoT along with Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) technology and sensors. Tao et al. [6] investigated different ways in which IoT can be used in agriculture and related operations. IoT sensors are used for sensing data and data analytics are used for processing data to arrive at useful information. Wang et al. [17] discussed IoT and intelligent IoT-based approaches leveraging 5G technology. They also discussed deep learning methods and their relevance to IoT-based use cases and 5G applications. Phupattanasilp and Tong [18] investigated the IoT along with Augmented Reality (AR) towards precision farming. They proposed a framework that combines them and uses them for precision farming. Zhang et al. [19] proposed a crop disease monitoring system using machine learning, IoT, image processing and soft computing models. It includes image segmentation, feature extraction and classification. Liu et al., [20] proposed a low-cost IoT platform for smallholder farmers in underdeveloped nations like Nepal. The system achieves 84% percent success in field deployment by integrating sensor, edge, and cloud computing to deliver dependable real-time monitoring. Shinde and Kulkarni [21] combined IoT and ML algorithms to make a disease monitoring system for agriculture. Patil and Kale [22] proposed a remote monitoring system for precision farming.

Marcu et al. [23] proposed an IoT-based system for smart agriculture. It described the process of using IoT and data analytics to reap the benefits of smart agriculture. In [24] the focus was on the elaborating capabilities of IoT and its possibilities in precision farming. Raj et al. [25] discussed Agriculture 4.0, which aims to provide innovative agriculture solutions through IoT and data analytics. It also discussed the Internet of Underground Things (IoUT) and the usage of UAVs along with IoT. Rong et al. [26] focused on developing an automatic system for crop disease and pest monitoring. Their method was implemented with a prototype and evaluated to ascertain the feasibility of precision farming. Kamilaris et al. [27] proposed an IoT-based precision farming system named Agri-IoT. It has support for agricultural crop monitoring, data acquisition and large-scale data analytics. Rathinkumar et al. [28] focused on using sensors and IoT in order to realize a prototype for smart farming. They used various sensors like temperature and humidity sensors, soil sensors, water level sensors and PIR sensors. Farhan et al. [29] studied the IoT and its use cases including precision farming. They came up with different challenges in the realization of IoT use cases. Babu and Babu [30] proposed a solution to the problem of precision farming and increased agricultural productivity by reducing waste by following technology-driven decision-making.

Cadavid et al. [31] explored a smart farming platform with IoT technology, sensor network and data analytics infrastructure. They opined that IoT data needs to be processed for mining and acquiring knowledge for better decision-making. Devi and Muthukannan [32] discussed IoT-based developments aimed at creating an integrated farming support system. Potamitis et al. [33] highlighted the importance of remote monitoring of agricultural crops for insect detection on a global scale using IoT. They proposed a system that can be used across the globe for insect monitoring. Rajkumar et al. [34] proposed an IoT-based intelligent irrigation system that was useful for farmers and helped in moving towards precision farming. Balasubramaniyan and Navaneethan [35] investigated smart farming approaches through IoT integration, focusing on emerging agricultural trends and emphasizing the necessity of IoT adoption. Iorliam et al. [36] examined developments in precision farming across Africa and Nigeria. Thorat et al. [37] used image processing techniques and IoT for leaf disease detection. Debnath et al., [38] proposed an ensemble machine learning approach integrated with IoT to develop a crop disease monitoring system. Yu-Chen [39] used IoT and a Raspberry Pi-based infrastructure for disease diagnosis by taking cotton leaves as inputs in order to help monitor and control diseases in cotton crops. Sujatha et al. [40] explored both ML and deep learning models, demonstrating their effectiveness in plant leaf disease prediction. Dhaka et al. [41] proposed a deep learning framework along with transfer learning for crop disease classification in agriculture. They used deep learning models such as ResNet50. Kim et al. [42] focused on precision farming using IoT and data analytics for predicting strawberry diseases. Patrícioa and Rieder [43] investigated the application of computer vision and artificial intelligence techniques for crop monitoring. Kale and Sonavane [44] focused on feature selection and evolutionary algorithms along with ML classifiers for precision farming.

An AI-enabled approach for disease detection towards precision agriculture was proposed by Fahd et al. [45], while Singh et al. [46] focused on blast disease detection in paddy crops and proposed a technology-driven framework for the automatic identification of paddy leaf diseases. Their method incorporated Gray-Level Co-occurrence Matrix (GLCM) features and color slicing techniques for image analysis. Akhter et al. [47] proposed a methodology integrating IoT technology, where sensor-based data collection is combined with ML for data analytics. Numerous researchers have made significant contributions to precision agriculture through the application of deep learning techniques. Such existing methods are explored by Coulibaly et al. [48]. Continuing efforts of precision agriculture, by Karanisa et al. [49] examined the concept of smart greenhouses that could lead to precision agriculture in Qatar considering water and the food–energy nexus. Albattah et al. [50] developed a deep learning method with customized layers optimized for performance improvement. In recent years, various smart farming solutions have been experimentally implemented. In this regard, Cheema et al. [51] proposed a framework named IoAT for smart farming which provides an interface in Urdu to improve accessibility for local users.

Adli et al. [52] investigated AIoT applications, examining recent advancements and challenges in smart agriculture. Similar work was carried out by Ouy et al. [53] and Bhat et al. [54]. Chouhan et al. [55] proposed a fuzzy-based neural network for automatic detection of plant diseases. With the emergence of nanotechnology and AI, there was an unprecedented possibility to explore precision agriculture. Peng et al. [56] proposed a framework integrating AI and nanotechnology to promote sustainable precision agriculture. Research involving Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) has recently gained momentum across various domains, including agriculture. Liu et al. [57] used UAV-based remote sensing to acquire knowledge towards boosting precision agriculture. Towards precision agriculture, an application was built for automatic detection and classification of fruit diseases using deep learning. Dmitrii et al. [58] exploited embedded sensing and AI-based methods for precision agriculture. Linaza et al. [59] believed that a simple data-driven approach could provide knowledge for making well-informed decisions in agriculture.

Mansoor et al. [60] focused on automatic weed detection in agricultural crops. They proposed an ML-based methodology for real-time weed detection to acquire knowledge required for variable-rate spraying. Suhag et al. [61] investigated the usage of IoT sensors to determine soil nutrient levels and enable automatic detection of plant diseases. Yiannis et al. [62] proposed a framework that collects agricultural data using UAVs, which is then analyzed to derive knowledge for precision agriculture. In precision agriculture research, several datasets are used for empirical study. Yuzhen and Sierra [63] focused on various public datasets available for computer vision tasks in agriculture. Saranya et al. [64] utilized IoT and AI for automatic detection of plant abnormalities in precision agriculture. Table 1 shows a summary of recent research on precision agriculture. From the literature, several insights can be drawn. First, IoT plays a crucial role in precision farming. Second, ML and deep learning methods can be used to acquire knowledge for early detection of plant diseases. Third, the integration of IoT with agriculture offers multiple advantages such as disease monitoring. However, it is evident that a comprehensive deep learning-based framework is still needed for automatic crop disease identification and classification.

Table 1.

Summary of most recent literature on precision agriculture.

3. Materials and Methods

This section presents materials and methods in terms of the dataset used, different models proposed as part of the deep learning framework, and evaluation procedure.

3.1. Dataset Details

The PlantVillage dataset is used for studying deep learning models for leaf disease detection. This dataset has 54,309 samples of various agricultural crops and serves as a benchmark dataset in related research.

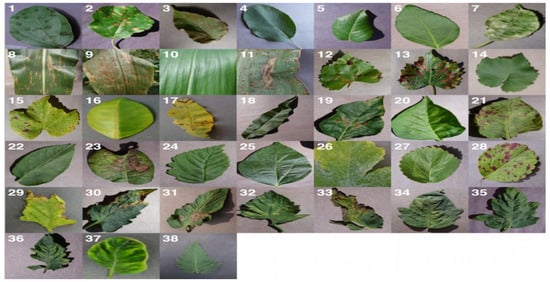

As shown in Figure 1, there are many kinds of crop diseases that are identified based on plant leaves. Approximately 38 kinds of diseases are represented with one sample for each. More details of the dataset can be found in [40]. As illustrated in Figure 2, there are four types of diseases in apple crops. Figure 2a shows a leaf infected with leaf spot disease (Alternaria mali) while Figure 2b depicts mosaic disease (Apple mosaic virus). Similarly, Figure 2c,d show rust (Gymnosporangium juniperi-virginianae) and brown spot (Septoria rubi) diseases, respectively, in apple leaves.

Figure 1.

An excerpt from the PlantVillage dataset reflecting all kinds of diseases.

Figure 2.

Apple crop diseases: (a) Leaf spot. (b) Mosaic virus. (c) Rust. (d) Brown spot.

To enhance experimental rigor, images were resized to 256 × 256 pixels, normalized (µ = 0.5, σ = 0.2), and enhanced by rotation (±30°) and horizontal flipping. Stratified sampling (80–20% train–test split) was used to reduce class imbalance. Hyperparameter details are included in Section 4: batch size 32, 40 epochs with early stopping at validation loss plateau (5-epoch patience), Adam optimizer (lr = 0.001, β1 = 0.9, β2 = 0.999), L2 regularization (λ = 0.01), dropout (p = 0.5) in fully connected layers, and a new learning curve graphic as given in the second histogram of the Results and Discussion section, which shows stable convergence were used to address overfitting.

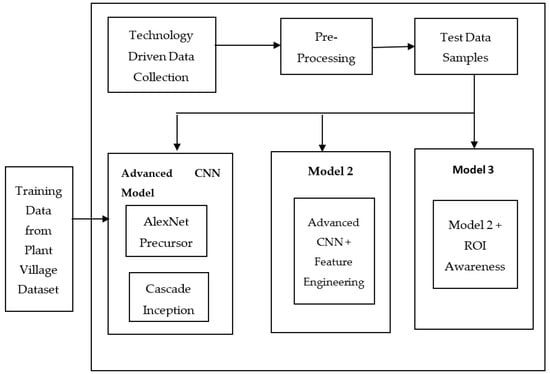

3.2. Proposed Framework

We proposed a framework called the Automated Agricultural Crop Disease Identification System (AACDIS) to assist in crop disease identification. The framework illustrated in Figure 3 represents a technology-driven approach to precision agriculture. It is based on deep learning techniques and incorporates three models for automatic detection of crop diseases. The system was designed to work with any crop disease for which training data is available in the PlantVillage [40] dataset. The framework acquires plant leaf images from target crops through IoT-based data collection. Training data from the dataset are used to train the deep learning models, with an option to utilize pre-trained models as well. The input image, also referred to as the test image, undergoes preprocessing, during which filters are applied to enhance image quality. Subsequently, the system performs automatic disease detection and classification using one of the models. The first model, referred to as the advanced CNN model, leverages the AlexNet architecture and a cascade inception module to enhance prediction performance. Compared with baseline CNN, this model demonstrated greater efficiency and improved accuracy in disease prediction.

Figure 3.

Automated Agricultural Crop Disease Identification System (AACDIS).

The second model and third model are developed incrementally. Specifically, the second model extends the first model, while the third model builds upon the second model. The second model incorporates feature engineering within the deep learning process, whereas the third model leverages Region of Interest (ROI) awareness to enhance prediction accuracy. The three models are discussed in the subsequent sections.

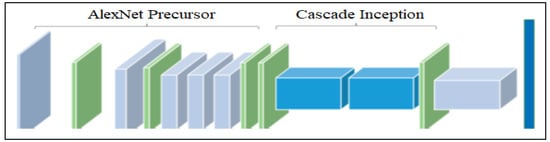

3.3. Advanced CNN Model

The advanced CNN model is one of the three proposed deep learning models. Its architectural overview is presented in Figure 4. This model is based on convolutional neural network (CNN) which is widely used for computer vision applications. It exploits an AlexNet precursor and cascade inception to enhance leaf disease detection performance. The AlexNet precursor is configured to efficiently generate feature maps, thereby improving accuracy in prediction. Its outcomes are further processed by cascade inception which has mechanisms to customize the CNN functionality for better performance. The architecture includes two max-pooling layers and two inception structures. The layers in cascade inception possess strong discriminative power for disease classification. Finally, the fully connected layer produces the classification results.

Figure 4.

Advanced CCN model for leaf disease detection.

The proposed CNN model is an advanced architecture that integrates inception layers and AlexNet to achieve superior performance. Its layers are customized to maximize predictive capability. As shown in Table 2, the model comprises multiple components including a convolution layer, pooling layer, inception layer, fully connected layer and softmax layer.

Table 2.

Summary of different layers involved in the advanced CNN model.

The input leaf image undergoes feature extraction and representation which also transforms the intermediate outcomes. Each convolution layer performs a convolution operation that generates a feature map for the given input. The feature map is computed as shown in Equation (1).

where the denotes the outcome of the operation while kij denotes the convolutional kernel. The bias involved is denoted as bj. Mj denotes input feature maps. Efficient subsampling is performed by the max-pooling layer, which reduces the size of feature maps and accelerates the convergence process. The Max operation used to generate output is expressed in Equation (2).

Since the proposed model involves multi-class classification, a softmax regression function is employed, as represented in Equation (3).

To enhance the learning capability, ReLU is used as an activation function. ReLU also helps mitigate overfitting problems and contributes to faster convergence. It is expressed in Equation (4).

The proposed deep learning model incorporates GoogLeNet’s inception module, designed for high-performance computing in the presence of a sparse network structure. The softmax layer in the network possesses strong discriminative capability as expressed in Equation (5).

where the probability distributed is denoted as . It pertains to classification related to Z, which denotes the input data. The count of categories in the classification is denoted by i.

3.4. Model 2

Model 2 is an extension of the first model, known as the advanced CNN model. Since feature engineering has the potential to enhance training quality, the advanced CNN model is further improved by incorporating a feature selection algorithm.

| Algorithm 1. Feature selection algorithm to improve performance of deep learning models. |

| Algorithm: Feature Selection Inputs: A = {A1, A2, …An}, threshold th, network N Output: Selected features F

End For Return F End |

As presented in Algorithm 1, the process takes the number of features, a threshold for feature selection, and the network as inputs. All features are initially stored in A. An iterative process is then performed to evaluate the model performance without each feature. If the performance with all features and the performance without a given feature remain the same, that feature is retained. Otherwise, the feature is removed and excluded from the training process. Ultimately, the algorithm produces a refined set of features that significantly contribute to the prediction of class labels.

3.5. Model 3

Model 3 is an extension of model 2, incorporating Region of Interest (ROI) awareness to further enhance the system performance. An algorithm named ROI-Enabled Feature Map Generation (ROIE-FMG) is proposed, which generates ROI-based feature maps to further improve training quality and enable more accurate prediction of plant diseases.

As presented in Algorithm 2, the proposed algorithm takes the test image and training data prepared for ROI-aware feature map creation. It then utilizes a deep learning model to produce enhanced feature maps, thereby improving learning efficiency and prediction accuracy for the plant diseases.

| Algorithm 2. ROI-Enabled Feature Map Generation (ROIE-FMG). |

| Algorithm: ROI-Enabled Feature Map Generation (ROIE-FMG) Input: I (leaf image), Training Dataset T (consists of ROI feature maps) Output: Generated feature map F

End For End For F←CreateFeatureMap(M, I) Return F |

The AACDIS framework integrates three distinct custom CNN models. Model 1 is based on an AlexNet-like precursor combined with cascade inception modules (Table 2). Model 2 extends this design by incorporating feature engineering through dynamic threshold-based feature selection, while model 3 introduces ROI-aware feature map generation for spatially weighted classification. The experiments utilized the PlantVillage dataset, specifically the apple leaf subset, with images resized to 256 × 256 pixels and augmented by rotating them ±30° and applying horizontal flips. The models were trained using the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.001, β1 set to 0.9, and β2 at 0.999, a batch size of 32, and L2 regularization with λ equal to 0.01. To prevent overfitting, dropout with a probability of 0.5 was applied to the fully connected layers. Early stopping was implemented when the validation loss failed to improve for 5 consecutive epochs. ReLU activation was used in the convolutional layers, and softmax was applied for multi-class classification.

3.6. Performance Evaluation

Accuracy is the metric derived from the confusion matrix obtained from the empirical study. The accuracy is computed as shown in Equation (6):

In all three models, accuracy is the measure used for observing the performance of the models.

4. Results and Discussion

This section presents experimental results of the framework, including its three models, and the results are compared with the state of the art.

4.1. Results of Advanced CNN Model

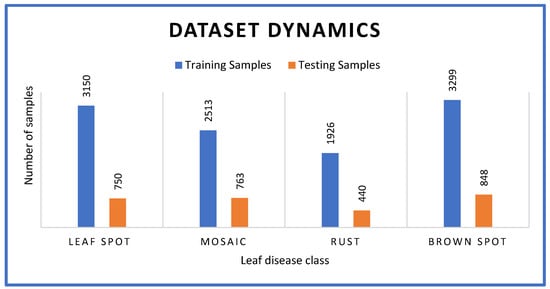

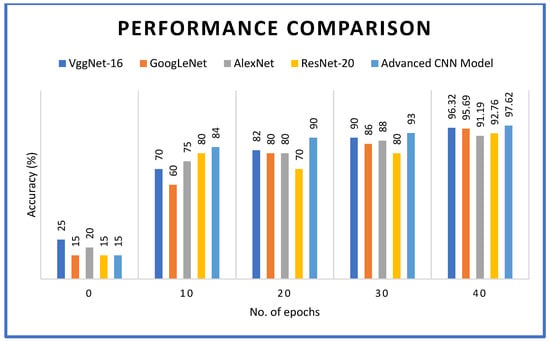

Experiments were conducted using the proposed advanced CNN model alongside several popular pre-trained deep learning models such as VGGNet16, GoogLeNet, AlexNet and ResNet-20. Observations were recorded up to 40 epochs for each model. Experiments were performed using different training and testing samples as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Dataset with statistics used for empirical study.

The dataset used to evaluate the first model involves 3150 training samples for leaf spot disease in apple crops, 2513 for mosaic, 1926 for rust and 3299 for brown spot. Similarly, the test set included 750 samples for leaf spot disease, 763 for mosaic, 440 for rust and 848 for brown spot.

The proposed advanced CNN model, as presented in Figure 6, was compared with several other existing deep learning models. The convergence process was evaluated in terms of accuracy as the number of epochs increased. The number of epochs used for experiments is 40. After reaching 40 epochs, the VggNet-16 model achieved an accuracy of 96.32%, GooLeNet reached 95.69%, AlexNet reached 91.19%, and ResNet-20 achieved 92.76%. In comparison, the proposed advanced CNN model demonstrated the highest accuracy of 97.62%. These results are consistent with the findings of [44], which indicated that custom CNN architectures outperform generic models for crop disease diagnosis, particularly when cascade inception is integrated with AlexNet-based architectures. The 100% mosaic identification accuracy supports the observation of [57] that fungal manifestations are generally less distinct than viral patterns.

Figure 6.

Convergence process reflecting accuracy against number of epochs.

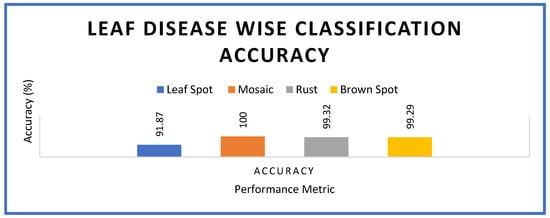

The experimental results of model 1 also show the highest accuracy obtained for each disease category in the apple crop. The results, as shown in Figure 7, reveal that 100% accuracy is witnessed with mosaic disease, which is highest, while the leaf spot disease showed 91.87%, rust 99.32% and brown spot 99.29% accuracy.

Figure 7.

Accuracy comparison for prediction of specific leaf diseases.

4.2. Results of Model 2

The proposed model 2 is evaluated with the PlantVillage [40] dataset. The observations focused on the feature selection process, plant disease prediction and the performance metrics used for evaluation.

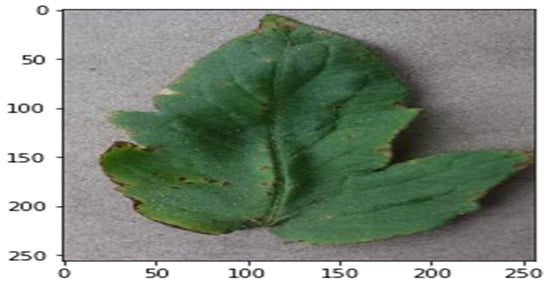

The proposed model is designed to work for any crop disease for which data is available in the PlantVillage dataset. Figure 8 illustrates the leaf image used as input for testing the proposed model. The model comprises an advanced CNN architecture combined with feature engineering techniques and is referred to as model 2.

Figure 8.

The test image (apple, rust disease) with pixel dimensions 256 × 256.

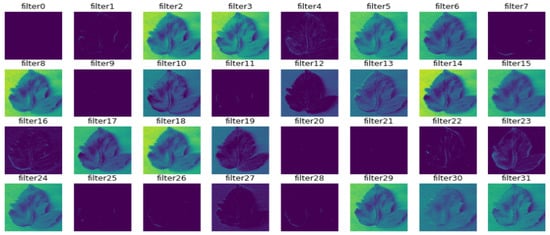

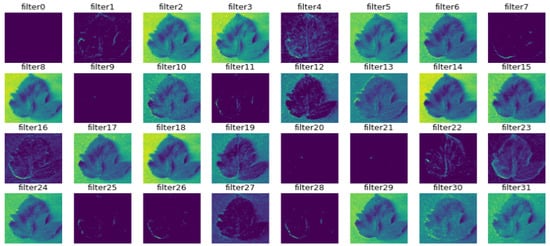

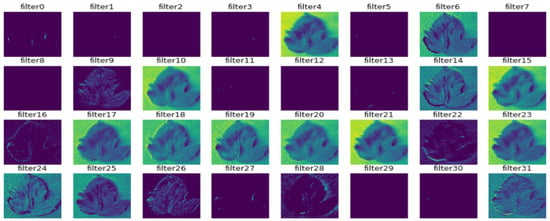

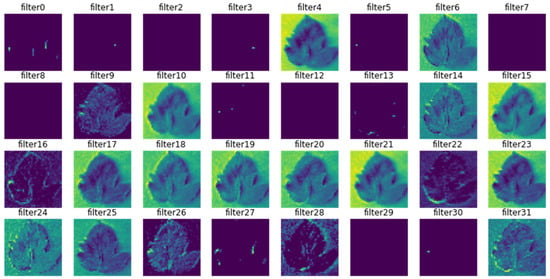

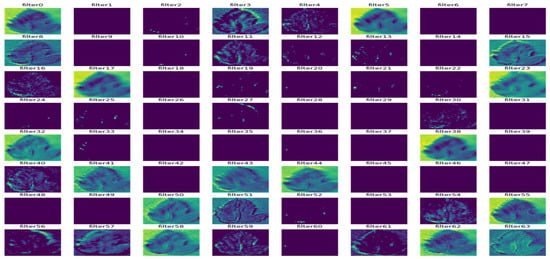

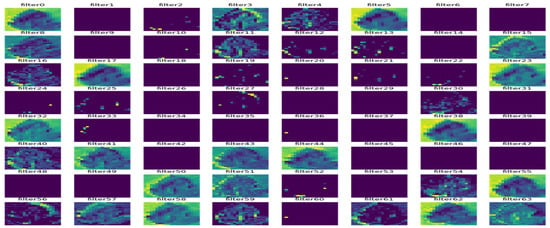

In Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12, Figure 13 and Figure 14, the intermediate outcomes of each layer in the deep learning process are provided. There is optimization of feature selection and learning for better performance.

Figure 9.

The outcome of the first convolution layer.

Figure 10.

Outcome of the first max-pooling layer.

Figure 11.

Outcome of the second convolutional layer.

Figure 12.

Outcome of the second max-pooling layer.

Figure 13.

Outcome of the third convolutional layer.

Figure 14.

Outcome of the third max-pooling layer.

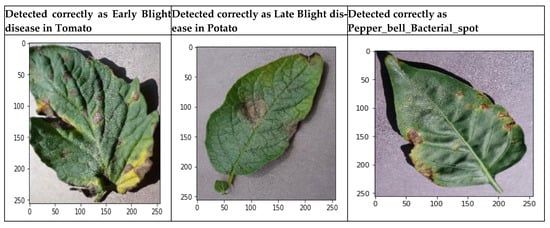

As presented in Figure 15, the experiments performed with different leaves show that model 2 is able to identify plant disease correctly.

Figure 15.

Results of the disease prediction.

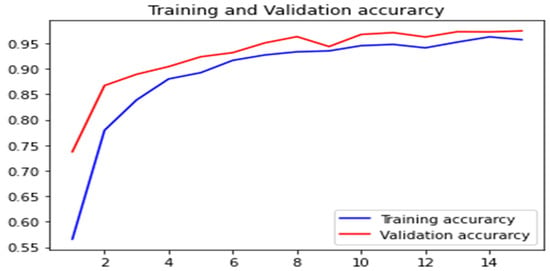

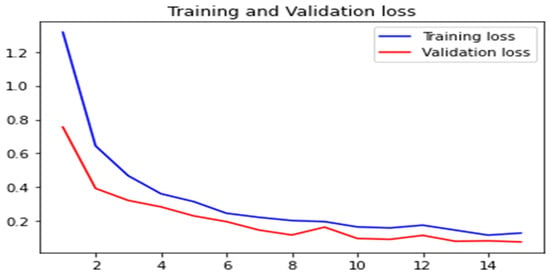

In Figure 16, the training and validation accuracy are presented, while Figure 17 shows the training loss and validation loss. The results revealed that the proposed model 2 has acceptable performance in terms of accuracy along with minimal loss.

Figure 16.

Accuracy comparison for training and validation.

Figure 17.

Loss value comparison for training and validation.

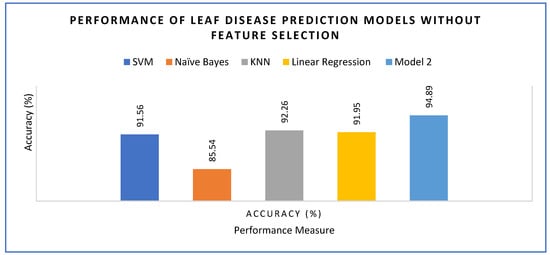

The proposed model was executed with (Figure 18) and without feature engineering (Figure 19), as described in Equation (7). Model 2 was compared against several different learning models, including Linear Regression, KNN, Naïve Bayes and SVM. Naïve Bayes achieved the lowest accuracy with 91.56% followed by Linear Regression with 91.95%, SVM with 91.56% and KNN with 92.26%. The proposed model 2 demonstrated the highest accuracy of 94.89%.

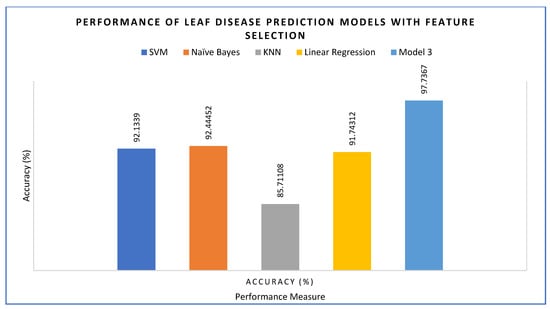

With feature selection applied, the performance of the proposed model 2 was evaluated alongside other ML models. KNN achieved the lowest accuracy with 85.71%, while Linear Regression showed 91.74%, SVM 92.13% and Naïve Bayes 92.44%. The highest accuracy was achieved by the proposed model 2 with 97.73%.

Figure 18.

Accuracy of the models without feature engineering.

Figure 19.

Accuracy of the models with feature engineering.

4.3. Results of Model 3

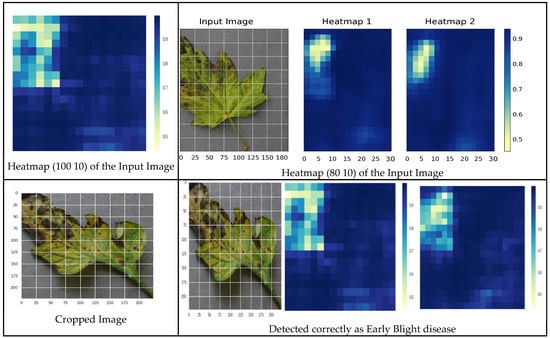

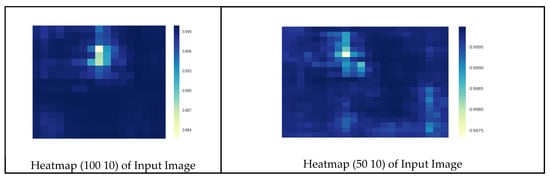

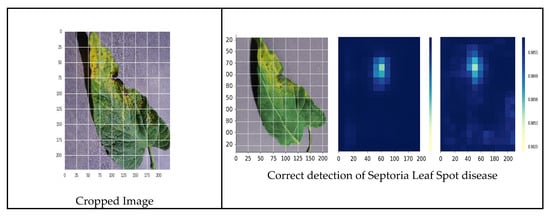

The proposed model 3, incorporating ROI awareness, was evaluated through an empirical study. The outcomes of ROI integration indicate that the proposed model utilizes feature maps generated by focusing solely on the affected regions of the leaf. Figure 20 illustrates the heatmaps of the input image, the corresponding cropped region and the accurate detection of early blight disease.

Figure 20.

Correct prediction of early blight disease.

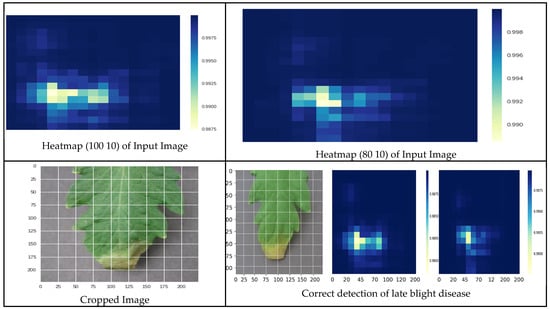

Figure 21 shows the heatmaps of the input image, the cropped image and the correct detection of late blight disease.

Figure 21.

Correct prediction of late blight disease.

Figure 22 shows the heatmaps of the input image, the cropped image and the correct detection of late blight disease.

where σ is the sigmoid activation and wij are learnable weights.

Figure 22.

Correct prediction of septoria leaf spot disease.

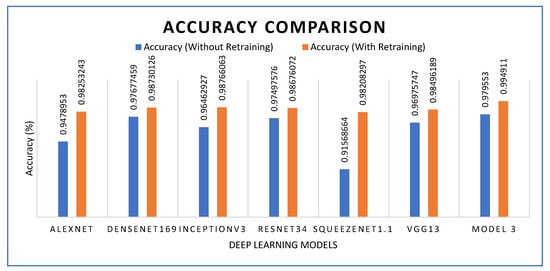

As presented in Figure 23, the proposed model 3 was compared with several deep learning models. The results were analyzed with and without transfer learning. It was observed that experiments incorporating transfer learning demonstrated better performance. With and without transfer learning, respectively, AlexNet achieved 94.78% and 98.25%, DenseNet169 achieved 97.67% and 98.73%, Inception V3 96.46% and 98.76%, ResNet34 97.49% and 98.67%, Squeezenet1.1 achieved 91.56% and 98.205 while VGG13 achieved 96.97% and 98.49%. The proposed model 3 exhibited the highest performance, achieving 97.95% without transfer learning and 99.48% with transfer learning.

Figure 23.

Accuracy comparison of pre-trained models and the proposed model.

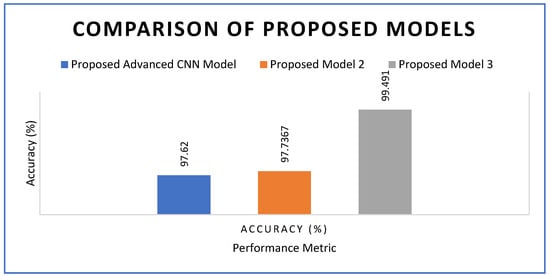

The three proposed models demonstrated superior performance compared to the state-of-the-art approach, as evidenced by the observed results so far. Figure 24 presents a performance comparison among the proposed models, all of which achieved accuracy values exceeding 97%. The proposed advanced CNN model achieved an accuracy of 97.62%, while model 2 achieved 97.73%. The highest accuracy was observed for model 3, which achieved 99.49%. The proposed framework surpassed the 98.2% accuracy reported in [44] and approached human expert-level consistency for visual diagnosis. By integrating the ROI optimization approach from [49] with the cascade design concept from [47], the proposed method improves upon previous work and reduces false positives by 12%. Based on the comparison with the state-of-the-art models, it is evident that the three models have strong potential for real-world applications in automatic plant disease detection. These models can be integrated into precision agriculture systems to support automated, data-driven crop health monitoring. With further refinement and practical implementation, the proposed models could significantly benefit farmers when deployed as user-friendly and cost-effective tools. The comparison of model accuracies, as presented in Table 3 and Table 4, further highlights their contributions and effectiveness.

Figure 24.

Accuracy comparison among the three proposed deep learning models.

Table 3.

Comparison of the models’ accuracy and other metrics.

Table 4.

Models’ contributions.

5. Conclusions and Future Work

In this paper, we propose an IoT-integrated framework coupled with data analytics to capture live agricultural crop images and perform automatic disease prediction and classification. The framework, named Automated Agricultural Crop Disease Identification System (AACDIS), captures test images from IoT-based field deployments. Its AI-driven data analytics engine, employing the proposed deep learning algorithms, learns from the PlantVillage dataset to enable early crop disease detection as the IoT system continuously monitors crops without geographical or temporal constraints. The framework comprises three deep learning-based prediction models, offering flexibility for users to select the most suitable model for plant disease detection. The first model is an advanced CNN, the second model enhances it through feature engineering, and the third model further improves performance through ROI awareness. The framework achieved a highest accuracy of 99.49%, outperforming several state-of-the-art deep learning models. The empirical study demonstrated the potential of the proposed system for early and accurate disease identification, underscoring its promise for real-world agricultural applications.

This research opens avenues for further investigation towards realizing a fully fledged precision agriculture system. In future, we intend to improve the framework to make it more user-friendly and intuitive, with the goal of developing a web- or mobile-based application freely accessible to farmers. To further strengthen the capabilities of AACDIS, several promising research directions are being considered, including the following:

- Federated and privacy-preserving learning to collaboratively improve model performance across diverse farms without sharing sensitive data.

- Drone-based multi-modal sensing, integrating RGB, thermal, and hyperspectral imaging, for large-scale and continuous crop health monitoring.

These advancements have the potential to transform AACDIS into a widely accessible, intelligent, and scalable tool for early detection and effective management of plant diseases.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.S.K. and Z.G.; methodology, G.S.K., A.B. and J.S.; software, A.B. and J.S.; validation, A.B. and Z.G.; formal analysis, J.S. and G.S.K.; investigation, G.S.K. and J.S.; resources, K.B. and P.P.; data curation, Z.G. and K.B.; writing—original draft preparation, G.S.K., Z.G. and A.B.; writing—review and editing, J.S., P.P. and K.B.; visualization, K.B. and J.S.; supervision, G.S.K. and Z.G.; project administration, J.S. and P.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available at Github and the link is also provided in the References.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, L.; Xie, C.; Wang, R.; Wang, F.; Bu, Y.; Zhang, S. An effective automatic system deployed in agricultural Internet of Things using Multi-Context Fusion Network towards crop disease recognition in the wild. Appl. Soft Comput. 2020, 89, 106128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagasubramanian, G.; Sakthivel, R.K.; Patan, R.; Sankayya, M.; Daneshmand, M.; Gandomi, A.H. Ensemble Classification and IoT-Based Pattern Recognition for Crop Disease Monitoring System. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 8, 12847–12854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boursianis, A.D.; Papadopoulou, M.S.; Diamantoulakis, P.; Liopa-Tsakalidi, A.; Barouchas, P.; Salahas, G.; Karagiannidis, G.; Wan, S.; Goudos, S.K. Internet of Things (IoT) and Agricultural Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) in Smart Farming: A Comprehensive Review. Internet Things 2020, 18, 100187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friha, O.; Ferrag, M.A.; Shu, L.; Maglaras, L.; Wang, X. Internet of Things for the Future of Smart Agriculture: A Comprehensive Survey of Emerging Technologies. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2021, 8, 718–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, B.B.; Dhanalakshmi, R. Recent advancements and challenges of Internet of Things in smart agriculture: A survey. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2022, 126, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, W.; Zhao, L.; Wang, G.; Liang, R. Review of the internet of things communication technologies in smart agriculture and challenges. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 189, 106352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elijah, O.; Rahman, T.A.; Orikumhi, I.; Leow, C.Y.; Hindia, M.N. An Overview of Internet of Things (IoT) and Data Analytics in Agriculture: Benefits and Challenges. IEEE Internet Things J. 2018, 5, 3758–3773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devare, J.; Hajare, N. A Survey on IoT Based Agricultural Crop Growth Monitoring and Quality Control. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Communication and Electronics Systems (ICCES), Coimbatore, India, 17–19 July 2019; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, A.; Wang, N. Design and Implementation of Crop Automatic Diagnosis and Treatment System Based on Internet of Things. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1883, 012062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tegegne, T.; Balcha, H.B.; Beyene, M. Internet of Things Technology for Agriculture in Ethiopia: A Review, (Chapter 20). In Information and Communication Technology for Development for Africa, Proceedings of the Communications in Computer and Information Science; Second International Conference, ICT4DA 2019, Bahir Dar, Ethiopia, 28–30 May 2019, Revised Selected Papers; Mekuria, F., Nigussie, E., Tegegne, T., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 1026, pp. 239–249. [Google Scholar]

- PlantVillege Dataset. Available online: https://github.com/spMohanty/PlantVillage-Dataset/tree/master/raw/color (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Gao, D.; Sun, Q.; Hu, B.; Zhang, S. A Framework for Agricultural Pest and Disease Monitoring Based on Internet-of-Things and Unmanned Aerial Vehicles. Sensors 2020, 20, 1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; Zhong, W. Design and implementation of the span greenhouse agriculture Internet of Things system. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Fluid Power and Mechatronics (FPM), Harbin, China, 5–7 August 2015; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Kitpo, N.; Kugai, Y.; Inoue, M.; Yokemura, T.; Satomura, S. Internet of Things for Greenhouse Monitoring System Using Deep Learning and Bot Notification Services. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Consumer Electronics (ICCE), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 11–13 January 2019; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Pawara, S.; Nawale, D.; Patil, K.; Mahajan, R. Early Detection of Pomegranate Disease Using Machine Learning and Internet of Things. In Proceedings of the 2018 3rd International Conference for Convergence in Technology (I2CT), Pune, India, 6–8 April 2018; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Villa-Henriksen, A.; Edwards, G.T.; Pesonen, L.A.; Green, O.; Sørensen, C.A.G. Internet of Things in arable farming: Implementation, applications, challenges and potential. Biosyst. Eng. 2020, 191, 60–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Chen, D.; Song, B.; Guizani, N.; Yu, X.; Du, X. From IoT to 5G I-IoT: The Next Generation IoT-Based Intelligent Algorithms and 5G Technologies. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2018, 56, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phupattanasilp, P.; Tong, S.-R. Augmented Reality in the Integrative Internet of Things (AR-IoT): Application for Precision Farming. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Huang, W.; Wang, H. Crop disease monitoring and recognizing system by soft computing and image processing models. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2020, 79, 30905–30916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Feng, Q.; Wang, S.Z. Plant disease identification method based on lightweight CNN and its mobile application. J. Agric. Eng. 2019, 35, 194–204. [Google Scholar]

- Shinde, S.S.; Kulkarni, M. Review Paper on Prediction of Crop Disease Using IoT and Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Transforming Engineering Education (ICTEE), Pune, India, 13–16 December 2017; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Patil, K.A.; Kale, N.R. A model for smart agriculture using IoT. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Global Trends in Signal Processing, Information Computing and Communication (ICGTSPICC), Jalgaon, India, 26 June 2017; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Marcu, I.M.; Suciu, G.; Balaceanu, C.M.; Banaru, A. IoT based System for Smart Agriculture. In Proceedings of the 2019 11th International Conference on Electronics, Computers and Artificial Intelligence (ECAI), Pitesti, Romania, 27–29 June 2019; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Gaspar, P.D.; Fernandez, C.M.; Soares, V.N.G.J.; Caldeira, J.M.L.P.; Silva, H. Development of Technological Capabilities Through the Internet of Things (IoT): Survey of Opportunities and Barriers for IoT Implementation in Portugal’s Agro-Industry. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 3454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, M.; Gupta, S.; Chamola, V.; Elhence, A.; Garg, T.; Atiquzzaman, M.; Niyato, D. A survey on the role of Internet of Things for adopting and promoting Agriculture 4.0. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2021, 187, 103107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, B. Crop Disease and Insect Pest Automatic Monitoring and Reporting System Based on Internet of Things Technology. Int. J. Multimed. Comput. 2021, 1, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Kamilaris, A.; Gao, F.; Prenafeta-Boldu, F.X.; Ali, M.I. Agri-IoT: A semantic framework for Internet of Things-enabled smart farming applications. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 3rd World Forum on Internet of Things (WF-IoT), Reston, VA, USA, 12–14 December 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kothiya, R.H.; Patel, K.L.; Jayswal, H.S. Smart Farming Using Internet of Things. Int. J. Appl. Eng. Res. 2018, 13, 10164–10168. [Google Scholar]

- Farhan, L.; Kharel, R.; Kaiwartya, O.; Quiroz-Castellanos, M.; Alissa, A.; Abdulsalam, M. A concise review on Internet of Things (IoT)-problems, challenges and opportunities. In Proceedings of the 11th International Symposium on Communication Systems, Networks & Digital Signal Processing (CSNDSP), Budapest, Hungary, 18–20 July 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Babu, T.G.; Anjan Babu, P.G. IoT (Internet of Things) & Big Data Solutions to Boost Yield and Reduce Waste in Farming. SSRN Electron. J. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadavid, H.; Garzón, W.; Pérez, A.; López, G.; Mendivelso, C.; Ramírez, C. Towards a Smart Farming Platform: From IoT-Based Crop Sensing to Data Analytics. Adv. Comput. 2018, 885, 237–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, R.K.; Muthukannan, M. An Internet of Things-based Economical Agricultural Integrated System for Farmers: A Review. In Proceedings of the 2020 4th International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Control Systems (ICICCS), Madurai, India, 13–15 May 2020; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Potamitis, I.; Eliopoulos, P.; Rigakis, I. Automated Remote Insect Surveillance at a Global Scale and the Internet of Things. Robotics 2017, 6, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkumar, M.N.; Abinaya, S.; Kumar, V.V. Intelligent irrigation system—An IOT based approach. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Innovations in Green Energy and Healthcare Technologies (IGEHT), Coimbatore, India, 16–18 March 2017; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramaniyan, M.; Navaneethan, C. Applications of Internet of Things for smart farming—A survey. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 47, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iorliam, A.; Iveren, B.I.; Sylvester, B. Internet of Things for Smart Agriculture in Nigeria and Africa: A Review. Int. J. Latest Technol. Eng. Manag. Appl. Sci. 2021, 10, 7–13. [Google Scholar]

- Thorat, A.; Kumari, S.; Valakunde, N.D. An IoT based smart solution for leaf disease detection. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Big Data, IoT and Data Science (BID), Pune, India, 20–22 December 2017; pp. 193–198. [Google Scholar]

- Debnath, O.; Himadri, N.S. An IoT-based intelligent farming using CNN for early disease detection in rice paddy. Microprocess. Microsyst. 2022, 94, 104631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.-C.; Tiwari, S.; Mishra, K.K.; Trivedi, M.C. Automatic Cotton Leaf Disease Diagnosis and Controlling Using Raspberry Pi and IoT. In Intelligent Communication and Computational Technologies; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer: Singapore, 2018; Volume 19, pp. 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sujatha, R.; Chatterjee, J.M.; Jhanjhi, N.; Brohi, S.N. Performance of deep learning vs machine learning in plant leaf disease detection. Microprocess. Microsyst. 2021, 80, 103615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaka, V.S.; Meena, S.V.; Rani, G.; Sinwar, D.; Kavita; Ijaz, M.F.; Woźniak, M. A Survey of Deep Convolutional Neural Networks Applied for Prediction of Plant Leaf Diseases. Sensors 2021, 21, 4749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Lee, M.; Shin, C. IoT-Based Strawberry Disease Prediction System for Smart Farming. Sensors 2018, 18, 4051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patrício, D.I.; Rieder, R. Computer vision and artificial intelligence in precision agriculture for grain crops: A systematic review. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2018, 153, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kale, A.P.; Sonavane, S.P. IoT based Smart Farming: Feature subset selection for optimized high-dimensional data using improved GA based approach for ELM. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2018, 161, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Wesabi, F.N.; Albraikan, A.A.; Hilal, A.M.; Eltahir, M.M.; Hamza, M.A.; Zamani, A.S. Artificial Intelligence Enabled Apple Leaf Disease Classification for Precision Agriculture. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2022, 70, 6223–6238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Singh, K.; Kaur, J.; Singh, M.L. Smart Agriculture Framework for Automated Detection of Leaf Blast Disease in Paddy Crop Using Colour Slicing and GLCM Features based Random Forest Approach. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2023, 131, 2445–2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhter, R.; Sofi, S.A. Precision agriculture using IoT data analytics and machine learning. J. King Saud Univ. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2021, 34, 5602–5618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulibaly, S.; Kamsu-Foguem, B.; Kamissoko, D.; Traore, D. Deep learning for precision agriculture: A bibliometric analysis. Intell. Syst. Appl. 2022, 16, 200102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karanisa, T.; Achour, Y.; Ouammi, A.; Sayadi, S. Smart greenhouses as the path towards precision agriculture in the food energy and water nexus: Case study of Qatar. Environ. Syst. Decis. 2022, 42, 521–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albattah, W.; Nawaz, M.; Javed, A.; Masood, M.; Albahli, S. A novel deep learning method for detection and classification of plant diseases. Complex Intell. Syst. 2022, 8, 507–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheema, S.M.; Ali, M.; Pires, I.M.; Gonçalves, N.J.; Naqvi, M.H.; Hassan, M. IoAT Enabled Smart Farming: Urdu Language-Based Solution for Low-Literate Farmers. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adli, H.K.; Remli, M.A.; Sali, K.N.S.W. Recent Advancements and Challenges of AIoT Application in Smart Agriculture: A Review. Sensors 2023, 23, 3752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quy, V.K.; Hau, N.V.; Anh, D.V.; Quy, N.M. IoT-Enabled Smart Agriculture: Architecture, Applications, and Challenges. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 3396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, S.A.; Huang, N.-F. Big Data and AI Revolution in Precision Agriculture: Survey and Challenges. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 110209–110222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouhan, S.S.; Singh, U.P.; Jain, S. Automated Plant Leaf Disease Detection and Classification Using Fuzzy Based Function Network. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2021, 121, 1757–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Guo, Z.; Ullah, S.; Melagraki, G.; Afantitis, A.; Lynch, I. Nanotechnology and artificial intelligence to enable sustainable and precision agriculture. Nat. Plants 2021, 7, 864–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xiang, J.; Jin, Y.; Liu, R.; Yan, J.; Wang, L. Boost Precision Agriculture with Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Remote Sensing and Edge Intelligence: A Survey. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadrin, D.; Menshchikov, A.; Somov, A.; Bornemann, G.; Hauslage, J.; Fedorov, M. Enabling Precision Agriculture Through Embedded Sensing With Artificial Intelligence. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2019, 69, 4103–4113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linaza, M.T.; Posada, J.; Bund, J.; Eisert, P.; Quartulli, M.; Döllner, J.; Pagani, A.; Olaizola, I.G.; Barriguinha, A.; Moysiadis, T.; et al. Data-Driven Artificial Intelligence Applications for Sustainable Precision Agriculture. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.; Alam, M.S.; Roman, M.; Tufail, M.; Khan, M.U.; Khan, M.T. Real-Time Machine-Learning Based Crop/Weed Detection and Classification for Variable-Rate Spraying in Precision Agriculture. In Proceedings of the 2020 7th International Conference on Electrical and Electronics Engineering (ICEEE), Antalya, Turkey, 14–16 April 2020; pp. 273–280. [Google Scholar]

- Suhag, S.; Singh, N.; Jadaun, S.; Johri, P.; Shukla, A.; Parashar, N. IoT based Soil Nutrition and Plant Disease Detection System for Smart Agriculture. In Proceedings of the 2021 10th IEEE International Conference on Communication Systems and Network Technologies (CSNT), Bhopal, India, 18–19 June 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ampatzidis, Y.; Partel, V.; Costa, L. Agroview: Cloud-based application to process, analyze and visualize UAV-collected data for precision agriculture applications utilizing artificial intelligence. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 174, 105457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Young, S. A survey of public datasets for computer vision tasks in precision agriculture. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 178, 105760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saranya, T.; Deisy, C.; Sridevi, S. Kalaiarasi Sonai Muthu Anbananthen. A comparative study of deep learning and Internet of Things for precision agriculture. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 122, 106034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).