Multimodal Large Language Models vs. Human Authors: A Comparative Study of Chinese Fairy Tales for Young Children

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Evaluation on LLMs

- Accuracy: Exact match, quasi-exact match, F1 score, ROUGE score.

- Calibrations: Expected calibration error, area under the curve.

- Fairness: Demographic parity difference, equalized odds difference.

- Robustness: Attack success rate, performance drop rate.

- Accuracy: Assessing whether the information aligns with factual knowledge and avoids errors and inaccuracies.

- Relevance: Evaluating the appropriateness and significance of the generated content.

- Fluency: Examining the language model’s ability to produce content that flows smoothly, maintaining a consistent tone and style.

- Transparency: Determining how well the model communicates its thought processes, enabling users to understand how and why certain responses are generated.

- Safety: Ensuring the language model avoids producing content that may be inappropriate, offensive, or harmful, thus protecting the well-being of users and preventing misinformation.

- Human alignment: Measuring the degree to which the language model’s output aligns with human values, preferences, and expectations.

2.2. Story Generation

2.3. Parents’ Acceptance of AI-Based Storytelling

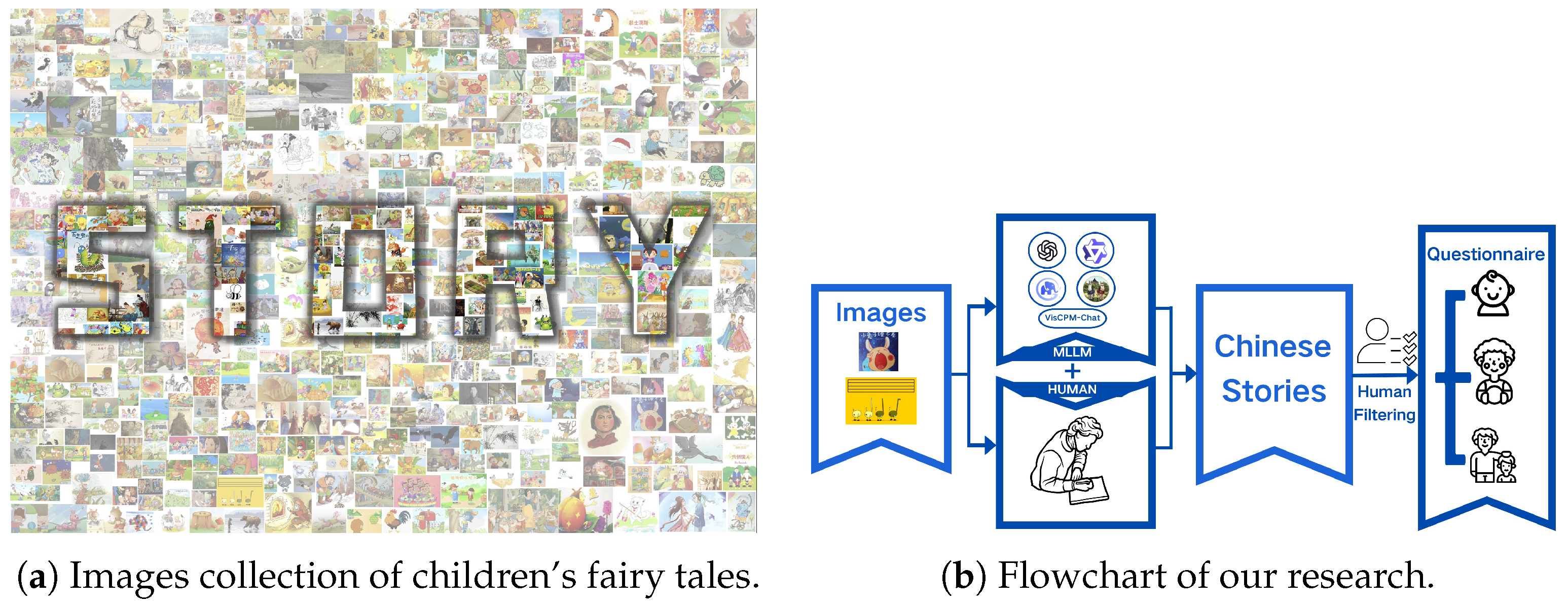

3. Research Method

- H1: For evaluators with relevant majors, there is no significant difference between Chinese children’s fairy tales written by humans and those generated by MLLMs for the same image prompt.

- H2: Elementary school students find stories generated by MLLMs to be as engaging as those written by humans.

- H3: Parents perceive stories generated by MLLMs to be acceptable and potentially usable for their children.

3.1. Study 1: Evaluating MLLM-Generated and Human-Written Stories

3.1.1. Participants and Materials for Study 1

3.1.2. Design and Procedure for Study 1

3.2. Study 2: Distinguishing MLLM-Generated from Human-Written Stories

3.2.1. Participants and Materials for Study 2

3.2.2. Design and Procedure for Study 2

4. Results

4.1. Human Evaluation of Human-Written and MLLM-Generated Stories

4.2. Response of Elementary School Students

4.3. Parents’ Distinguishing Ability and Evaluation of MLLM-Generated Stories

5. Discussion

5.1. The Impacts of AI Tools Represented by LLMs on Education

5.2. The Influence of AIGC on Cultural Innovation and Inheritance

5.3. Technological Breakthroughs and Ethical Considerations

5.4. Computational Cost Analysis of MLLM Story Generation

5.5. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

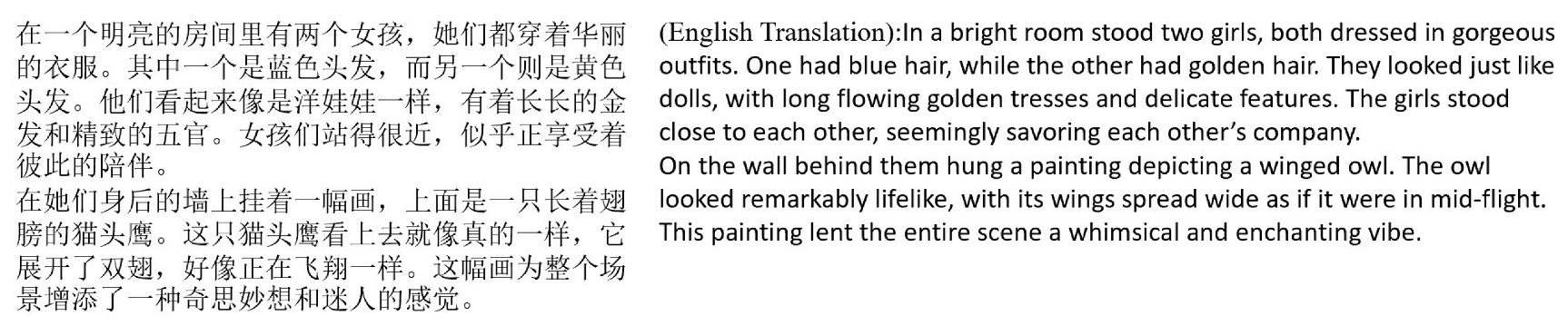

|  |  |

|---|---|---|

| Prompt: According to the above image, please tell a children’s fairy tale in English. | Prompt (English Translation): According to the above image, please tell a children’s fairy tale in Chinese. | Prompt (English Translation): Please tell a relatively long Chinese children’s fairy tale based on this picture, which includes several paragraphs. |

|  |  |

|  |

|---|---|

| Prompt (English Translation): According to the above image, please tell a children’s fairy tale in Chinese. | Prompt (English Translation): Please tell a relatively long Chinese children’s fairy tale based on this picture, which includes several paragraphs. |

|  |

|  |  |

|---|---|---|

| Prompt (English Translation): Please tell a relatively long Chinese children’s fairy tale based on this picture, which includes several paragraphs. | Prompt (English Translation): Please tell a relatively long Chinese children’s fairy tale based on this picture, which includes several paragraphs. | Prompt (English Translation): Please tell a relatively long Chinese children’s fairy tale based on this picture, which includes several paragraphs. |

|  |  |

References

- Zipes, J. Fairy Tales and the Art of Subversion, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Poole, C. The Importance of Fairy Tales for Children. 2022. Available online: https://thinkingwest.com/2022/04/25/importance-of-fairy-tales/ (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- Wang, S. Problems and Reflections on Children’s Literature Creation in the New Century. Chin. Lit. Crit. 2024, 2, 151–160. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, X. A Brief Discussion on Children’s Literature, 1st ed.; People’s Posts and Telecommunications Press: Beijing, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- VisikoKnox-Johnson, L. The Positive Impacts of Fairy Tales for Children. Hohonu 2016, 14, 77–81. [Google Scholar]

- Winick, S. Einstein’s Folklore|FolkLife Today. The Library of Congress. 2013. Available online: https://blogs.loc.gov/folklife/2013/12/einsteins-folklore/ (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- OpenAI; Achiam, J.; Adler, S.; Agarwal, S.; Ahmad, L.; Akkaya, I.; Aleman, F.L.; Almeida, D.; Altenschmidt, J.; Altman, S.; et al. GPT-4 Technical Report. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2303.08774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, C.; Zhang, A.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, J.; Yasunaga, M.; Yang, D. Is ChatGPT a General-Purpose Natural Language Processing Task Solver? In Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Singapore, 6–10 December 2023; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Makridis, G.; Oikonomou, A.; Koukos, V. FairyLandAI: Personalized Fairy Tales utilizing ChatGPT and DALLE-3. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.0946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.; Jiang, J.; Chang, D.; Liu, P. Storypark: Leveraging Large Language Models to Enhance Children Story Learning Through Child-AI collaboration Storytelling. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.06495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Cohn, T.; Lau, J.H. The Next Chapter: A Study of Large Language Models in Storytelling. In Proceedings of the 16th International Natural Language Generation Conference, Online, 13–15 September 2023; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2023; pp. 323–351. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.; Tang, C.; Loakman, T.; Guerin, F.; Lin, C. Improving Chinese Story Generation via Awareness of Syntactic Dependencies and Semantics. In Proceedings of the 2nd Conference of the Asia-Pacific Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 12th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 2: Short Papers), Taipei, Taiwan, 20–23 November 2022; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2022; pp. 178–185. [Google Scholar]

- Khurana, D.; Koli, A.; Khatter, K.; Singh, S. Natural language processing: State of the art, current trends and challenges. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2023, 82, 3713–3744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Hao, Q.; Zong, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Lan, X.; Gong, J.; Ouyang, T.; Meng, F.; et al. Towards Large Reasoning Models: A Survey of Reinforced Reasoning with Large Language Models. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.09686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Song, S.; Yang, J.; Niu, S.; Hu, J.; Liu, D.; Yao, S.; Xiong, F.; et al. Controllable Text Generation for Large Language Models: A Survey. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.12599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Tian, Y.; Zhou, W.; Xu, N.; Hu, Q.; Gupta, R.; Wieting, J.; Peng, N.; Ma, X. Evaluating Large Language Models on Controlled Generation Tasks. In Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Singapore, 6–10 December 2023; pp. 3155–3168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Singh, A.; Michael, J.; Hill, F.; Levy, O.; Bowman, S. GLUE: A Multi-Task Benchmark and Analysis Platform for Natural Language Understanding. In Proceedings of the 2018 EMNLP Workshop BlackboxNLP: Analyzing and Interpreting Neural Networks for NLP, Brussels, Belgium, 1 November 2018; Linzen, T., Chrupała, G., Alishahi, A., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2018; pp. 353–355. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, A.; Pruksachatkun, Y.; Nangia, N.; Singh, A.; Michael, J.; Hill, F.; Levy, O.; Bowman, S.R. SuperGLUE: A stickier benchmark for general-purpose language understanding systems. In Proceedings of the 33rd International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, New Orleans, LA, USA, 10–16 December 2023; Curran Associates Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 3266–3280. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Wu, Y.; Yang, L.; Zhu, K.; Chen, H.; Yi, X.; Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; et al. A Survey on Evaluation of Large Language Models. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 2024, 15, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Kishore, V.; Wu, F.; Weinberger, K.Q.; Artzi, Y. BERTScore: Evaluating Text Generation with BERT. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Learning Representations, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 26–30 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Novikova, J.; Dušek, O.; Cercas Curry, A.; Rieser, V. Why We Need New Evaluation Metrics for NLG. In Proceedings of the 2017 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Copenhagen, Denmark, 9–11 September 2017; Palmer, M., Hwa, R., Riedel, S., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2017; pp. 2241–2252. [Google Scholar]

- Alabdulkarim, A.; Li, S.; Peng, X. Automatic Story Generation: Challenges and Attempts. In Proceedings of the Third Workshop on Narrative Understanding, Online, 11 June 2021; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2021; pp. 72–83. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, NIPS’17, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; Curran Associates Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 6000–6010. [Google Scholar]

- Radford, A.; Narasimhan, K.; Salimans, T.; Sutskever, I. Improving Language Understanding by Generative Pre-Training. 2018. Available online: https://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/openai-assets/research-covers/language-unsupervised/language_understanding_paper.pdf (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- Radford, A.; Wu, J.; Child, R.; Luan, D.; Amodei, D.; Sutskever, I. Language Models Are Unsupervised Multitask Learners. 2019. Available online: https://d4mucfpksywv.cloudfront.net/better-language-models/language_models_are_unsupervised_multitask_learners.pdf (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- Lewis, M.; Liu, Y.; Goyal, N.; Ghazvininejad, M.; Mohamed, A.; Levy, O.; Stoyanov, V.; Zettlemoyer, L. BART: Denoising Sequence-to-Sequence Pre-training for Natural Language Generation, Translation, and Comprehension. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Online, 5–10 July 2020; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 7871–7880. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.D.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; et al. Language models are few-shot learners. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Virtual, 6–12 December 2020; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2020; Volume 33, pp. 1877–1901. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Shu, R.; Takamura, H.; Nakayama, H. GraphPlan: Story Generation by Planning with Event Graph. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Natural Language Generation, Aberdeen, UK, 20–24 September 2021; Association for Computational Linguistic: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2021; pp. 377–386. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, L.; Peng, N.; Weischedel, R.; Knight, K.; Zhao, D.; Yan, R. Plan-and-write: Towards better automatic storytelling. In Proceedings of the Thirty-Third AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Thirty-First Innovative Applications of Artificial Intelligence Conference and Ninth AAAI Symposium on Educational Advances in Artificial Intelligence, Honolulu, HI, USA, January–1 February 2019; AAAI Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; pp. 7378–7385. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, D.; Greenwood, C.; Hart, B.; Carta, J. Prediction of school outcomes based on early language production and socioeconomic factors. Child Dev. 1994, 65, 606–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valentini, M.; Weber, J.; Salcido, J.; Wright, T.; Colunga, E.; von der Wense, K. On the Automatic Generation and Simplification of Children’s Stories. In Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Singapore, 6–10 December 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bhandari, P.; Brennan, H. Trustworthiness of Children Stories Generated by Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the 16th International Natural Language Generation Conference, Prague, Czechia, 11–15 September 2023; Keet, C.M., Lee, H.Y., Zarrieß, S., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2023; pp. 352–361. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, J. Usability Engineering; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Driessen, G.; Smit, F.; Sleegers, P. Parental Involvement and Educational Achievement. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2005, 31, 509–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nastasiuk, A.; Courteau, E.; Thomson, J.; Deacon, S.H. Drawing attention to print or meaning: How parents read with their preschool-aged children on paper and on screens. J. Res. Reading 2024, 47, 412–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Šabanović, S.; Dombrowski, L.; Miller, A.D.; Brady, E.; MacDorman, K.F. Parental Acceptance of Children’s Storytelling Robots: A Projection of the Uncanny Valley of AI. Front. Robot. AI 2021, 8, 579993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Chen, J.; Yao, B.; Liu, J.; Wang, D.; Ma, X.; Lu, Y.; Xu, Y.; He, L. Exploring Parent’s Needs for Children-Centered AI to Support Preschoolers’ Interactive Storytelling and Reading Activities. Proc. ACM-Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2024, 8, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenAI. ChatGPT. 2023. Available online: https://chat.openai.com.chat (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- Hu, J.; Yao, Y.; Wang, C.; Wang, S.; Pan, Y.; Chen, Q.; Yu, T.; Wu, H.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, H.; et al. Large Multilingual Models Pivot Zero-Shot Multimodal Learning across Languages. In Proceedings of the Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations, Vienna, Austria, 7 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Y.; Yang, Z.; Yao, X. Efficient and Effective Text Encoding for Chinese LLaMA and Alpaca. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.08177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; Qian, Y.; Liu, X.; Ding, M.; Qiu, J.; Yang, Z.; Tang, J. GLM: General Language Model Pretraining with Autoregressive Blank Infilling. In Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Dublin, Ireland, 22–27 May 2022; Volume 1: Long Papers, pp. 320–335. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, J.; Bai, S.; Yang, S.; Wang, S.; Tan, S.; Wang, P.; Lin, J.; Zhou, C.; Zhou, J. Qwen-VL: A Versatile Vision-Language Model for Understanding, Localization, Text Reading, and Beyond. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.12966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S. Research on Teaching Strategies for Picture-Based Writing in Primary School Chinese Language Education. Educ. Adv. 2024, 13, 7218–7223. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, Y.; Zhou, X.; Li, Y.; De, X.; Li, H.; Liu, X. Developmental Trends of Literacy Skills of Chinese Lower Graders: The Predicting Effects of Reading-related Cognitive Skills. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2018, 34, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riskin, J. The Restless Clock: A History of the Centuries-Long Argument Over What Makes Living Things Tick; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Castellano, G.; Vessio, G. Deep learning approaches to pattern extraction and recognition in paintings and drawings: An overview. Neural Comput. Appl. 2021, 33, 12263–12282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Olivan, C.; Hernandez-Olivan, J.; Beltran, J.R. A Survey on Artificial Intelligence for Music Generation: Agents, Domains and Perspectives. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2210.13944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarty, T.; Padmakumar, V.; He, H. Help me write a Poem - Instruction Tuning as a Vehicle for Collaborative Poetry Writing. In Proceedings of the 2022 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 7–11 December 2022; pp. 6848–6863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirowski, P.; Mathewson, K.W.; Pittman, J.; Evans, R. Co-Writing Screenplays and Theatre Scripts with Language Models: Evaluation by Industry Professionals. In Proceedings of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, New York, NY, USA, 23–28 April 2023. CHI ’23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Wu, H.; Jiang, L.; Liu, X.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, M. From Role-Play to Drama-Interaction: An LLM Solution. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2024, Bangkok, Thailand, 11–16 August 2024; pp. 3271–3290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egg, A. An AI Learning Robot for Children, That Follows Along and Reads Whatever You Point at. 2016. Available online: https://www.toycloud.com (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- Zhao, Z.; McEwen, R. Luka—Investigating the Interaction of Children and Their Home Reading Companion Robot: A Longitudinal Remote Study. In Proceedings of the Companion of the 2021 ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction, New York, NY, USA, 8–11 March 2021; HRI ’21 Companion. pp. 141–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codi, M. An Interactive, AI-Enabled Smart Toy for Kids. 2021. Available online: https://www.pillarlearning.com/ (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- Dietz, G.; Le, J.K.; Tamer, N.; Han, J.; Gweon, H.; Murnane, E.L.; Landay, J.A. StoryCoder: Teaching Computational Thinking Concepts Through Storytelling in a Voice-Guided App for Children. In Proceedings of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, New York, NY, USA, 8–13 May 2021. CHI ’21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Xu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yao, B.; Ritchie, D.; Wu, T.; Yu, M.; Wang, D.; Li, T.J.J. StoryBuddy: A Human-AI Collaborative Chatbot for Parent-Child Interactive Storytelling with Flexible Parental Involvement. In Proceedings of the 2022 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, New York, NY, USA, 29 April–5 May 2022. CHI ’22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, R. Text and Image Studies on AIGC Productivity in the Age of Humanity 3.0; China Social Sciences Press: Beijing, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Gu, H.; Zheng, T.; Xiang, L.; Wu, H.; Fu, J.; He, Z. Dynamic Generation of Personalities with Large Language Models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.07084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, B.; Machery, E. AI-generated poetry is indistinguishable from human-written poetry and is rated more favorably. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 26133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Li, Y.; Cao, Q.; Chen, J.; Yang, T.; Wu, Z.; Hale, J.; Gibbs, J.; Rasheed, K.; Liu, N.; et al. Transformation vs Tradition: Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) for Arts and Humanities. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.19626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.; Mahir, S.H.; Tashrif, M.T.A.; Aishi, A.A.; Karim, M.A.; Kundu, D.; Debnath, T.; Moududi, M.A.A.; Eidmum, M.Z.A. Comparative Analysis Based on DeepSeek, ChatGPT, and Google Gemini: Features, Techniques, Performance, Future Prospects. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.04783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Hu, Z.; Wang, C. Empowering education development through AIGC: A systematic literature review. Educ. Inf. Technol.s 2024, 29, 17485–17537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelghani, R.; Wang, Y.H.; Yuan, X.; Wang, T.; Lucas, P.; Sauzéon, H.; Oudeyer, P.Y. GPT-3-Driven Pedagogical Agents to Train Children’s Curious Question-Asking Skills. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ.n 2023, 34, 483–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerneža, M. Fundamental and basic cognitive skills required for teachers to effectively use chatbots in education. In Science And Technology Education: New Developments And Innovations; Scientia Socialis, UAB: Siauliai, Lithuani, 2023; pp. 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, W.; Kay, J. AI in Education. Coming of Age? The Community Voice. In Proceedings of the Artificial Intelligence in Education. Posters and Late Breaking Results, Workshops and Tutorials, Industry and Innovation Tracks, Practitioners, Doctoral Consortium and Blue Sky, Tokyo, Japan, 3–7 July 2023; pp. 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Method | Fluency ↑ | Coherence ↑ | Relevance ↑ | Logic ↑ | Enjoyment ↑ | Rank ↓ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human | 3.94 | 4.20 | 3.94 | 4.10 | 3.38 | 1.86 |

| ChatGPT-4.0 | 4.38 | 4.30 | 3.56 | 4.02 | 3.46 | 2.48 |

| VisCPM-10B | 4.30 | 4.14 | 3.02 | 3.40 | 1.94 | 4.58 |

| VCLA-7B | 4.28 | 3.68 | 2.64 | 3.06 | 2.02 | 4.76 |

| VisualGLM-6B | 4.28 | 4.04 | 2.96 | 2.92 | 1.90 | 4.44 |

| QWen-VL-7B | 4.36 | 4.24 | 3.34 | 3.60 | 3.28 | 2.88 |

| Mean | 95% CI | 95% CI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (I) Group | (J) Group | Difference (I-J) | Std. Error | Sig. | Lower Bound | Upper Bound |

| Human | ChatGPT-4.0 | −0.62 | 0.26 | 0.329 | −1.48 | 0.24 |

| VisCPM-10B | −2.72 | 0.26 | <0.001 | −3.58 | −1.86 | |

| VCLA-7B | −2.90 | 0.26 | <0.001 | −3.76 | −2.04 | |

| VisualGLM-6B | −2.58 | 0.26 | <0.001 | −3.44 | −1.72 | |

| QWen-VL-7B | −1.02 | 0.26 | 0.009 | −1.88 | −0.16 |

| Group | Num | Mean | SD | 95% CI | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| top-one | 0 | 6 | 3.33 | 2.58 | [0.62, 6.04] | |

| 1 | 20 | 2.35 | 2.18 | [1.33, 3.37] | ||

| 2 | 24 | 1.46 | 0.93 | [1.07, 1.85] | ||

| Total | 50 | 2.04 | 1.83 | [1.52, 2.56] | ||

| 0.046 (Between Groups) | ||||||

| top-two | 0 | 6 | 2.00 | 0.63 | [1.34, 2.66] | |

| 1 | 20 | 2.80 | 1.74 | [1.99, 3.61] | ||

| 2 | 24 | 3.17 | 1.99 | [2.33, 4.01] | ||

| Total | 50 | 2.88 | 1.79 | [2.37, 3.39] | ||

| 0.357 (Between Groups) |

| Reason | Frequency |

|---|---|

| “Rich in content.” | 1 |

| “Very suitable for children to read before going to bed. Mentioning sleep many times implies that children should go to sleep.” | 1 |

| “Rich in language and more suitable for children to read.” | 1 |

| “Familiar plot and interesting.” | 1 |

| “Described in detail.” | 1 |

| “Vivid and clearer description.” | 1 |

| “Detailed plot.” | 1 |

| “Her description is very suitable for children’s reading.” | 1 |

| “Suitable for children’s reading.” | 1 |

| “There is a plot and a revelation.” | 1 |

| “Human thought and creativity are above artificial intelligence.” | 1 |

| “Suitable for children’s cognitive levels.” | 1 |

| “Ups and downs in the plot.” | 1 |

| “Wisdom with underlying philosophical insights.” | 1 |

| “Quite reasonable, like the stories we often heard in childhood.” | 1 |

| “Cows like to eat various fruits and can produce milk with various fruit flavors. It’s interesting.” | 1 |

| “More humane language.” | 1 |

| “Interesting.” | 2 |

| “Interesting. Conform to logic.” | 1 |

| “Rich in plot.” | 1 |

| “Realistic.” | 1 |

| “Good imagination.” | 1 |

| “Beautiful language and strong logical coherence.” | 1 |

| “Somewhat absurd yet interesting.’ | 1 |

| “The language is suitable for children’s reading.” | 1 |

| “The human stories have good logical coherence, use relatively simple language, and are suitable for young children to read.” | 1 |

| “No reason.” | 6 |

| Reason | Frequency |

|---|---|

| “Good imagination.” | 1 |

| “The story is coherent, with rhetorical techniques and vivid language description. There is a sense of picture in detailed description.” | 1 |

| “Logical, simple and clear language with profound value.” | 1 |

| “The story is relatively smooth.” | 1 |

| “More lively and vivid.” | 1 |

| “The story plot is relatively reasonable, the language description is vivid and uses personification rhetorical techniques. The detailed description has a sense of picture.” | 1 |

| “Innovative.” | 1 |

| Reason | Frequency |

|---|---|

| “Read smoothly and is also relatively interesting.” | 1 |

| Reason | Frequency |

|---|---|

| “Cute.” | 1 |

| “More story plots.” | 1 |

| Reason | Frequency |

|---|---|

| “A snowman can build a snowman. That’s so fun.” | 1 |

| “Innovative” | 1 |

| “I like.” | 1 |

| “Vivid” | 1 |

| “Full of imagination and not a dull statement of pictures.” | 1 |

| “Full plot.” | 1 |

| “No reason.” | 1 |

| Method | Enjoyment ↑ | Rank ↓ |

|---|---|---|

| Human | 2.47 | 1.87 |

| ChatGPT-4.0 | 2.47 | 2.10 |

| QWen-VL | 2.47 | 2.00 |

| Method | Enjoyment ↑ | Rank ↓ |

|---|---|---|

| Human | 2.53 | 1.84 |

| ChatGPT-4.0 | 2.40 | 2.00 |

| QWen-VL-7B | 2.24 | 2.15 |

| Quality ↑ | Enjoyment ↑ | Plot ↑ | Popularity ↑ | Appeal ↑ | Assistance ↑ | Favorite ↓ | Willingness ↑ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3.93 | 3.83 | 4.01 | 3.93 | 3.89 | 4.00 | 1.62 | 3.78 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Du, J.; Liu, W.; Zhou, D.; Hong, S.; Liu, F. Multimodal Large Language Models vs. Human Authors: A Comparative Study of Chinese Fairy Tales for Young Children. Informatics 2025, 12, 139. https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics12040139

Du J, Liu W, Zhou D, Hong S, Liu F. Multimodal Large Language Models vs. Human Authors: A Comparative Study of Chinese Fairy Tales for Young Children. Informatics. 2025; 12(4):139. https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics12040139

Chicago/Turabian StyleDu, Jing, Wenhao Liu, Dibin Zhou, Seongku Hong, and Fuchang Liu. 2025. "Multimodal Large Language Models vs. Human Authors: A Comparative Study of Chinese Fairy Tales for Young Children" Informatics 12, no. 4: 139. https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics12040139

APA StyleDu, J., Liu, W., Zhou, D., Hong, S., & Liu, F. (2025). Multimodal Large Language Models vs. Human Authors: A Comparative Study of Chinese Fairy Tales for Young Children. Informatics, 12(4), 139. https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics12040139

_Bryant.png)