Mapping the AI Surge in Higher Education: A Bibliometric Study Spanning a Decade (2015–2025)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Bibliometric Analysis

2.2. Selected Databases and Search Strategies

2.3. Merging and Mapping the Data Using Bibliometric Research Steps

3. Discussion of the Findings

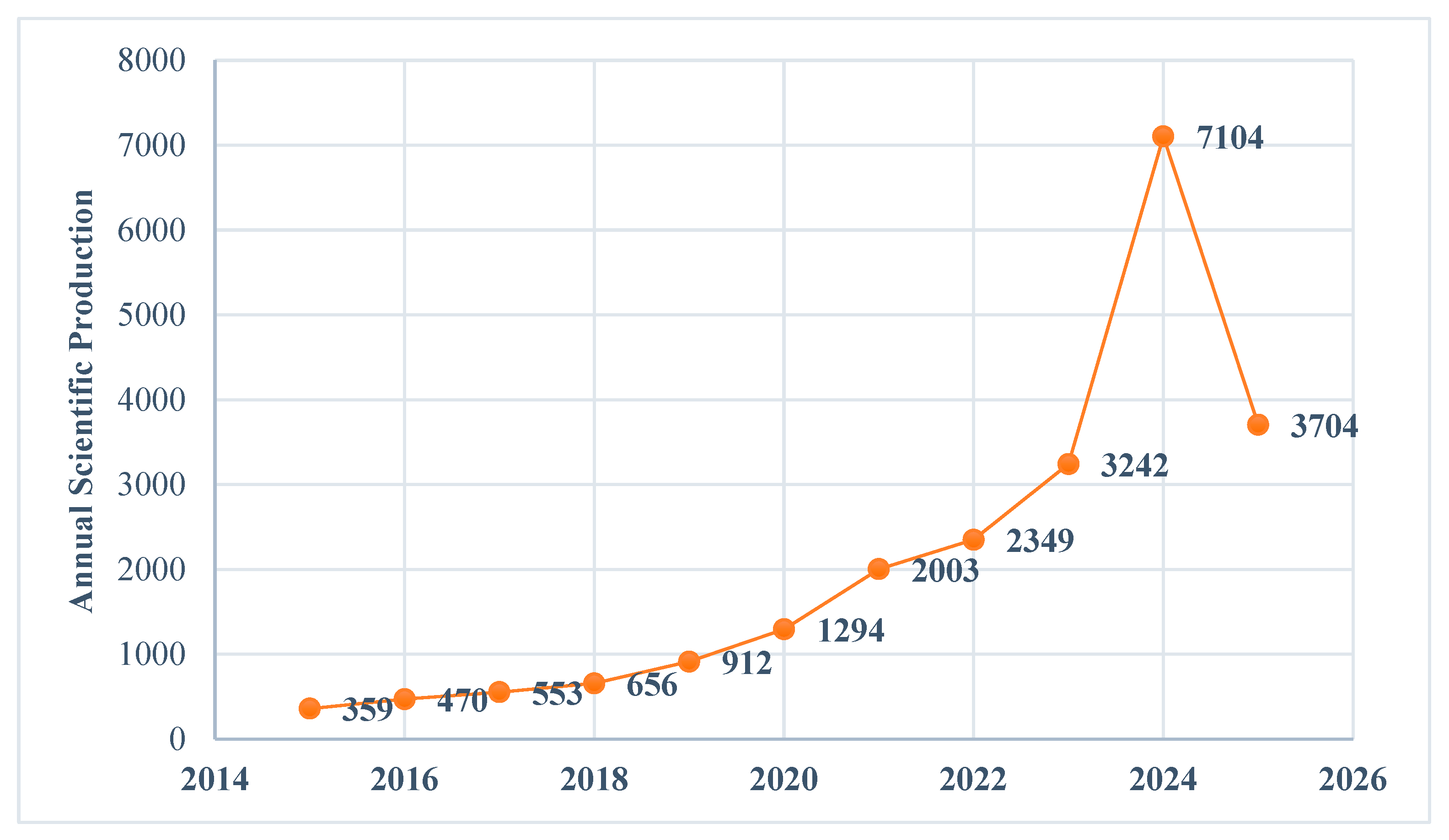

3.1. Publication Growth Trends and Annual Scientific Production (RQ1)

3.2. Leading Journals and Bradford’s Law (RQ2)

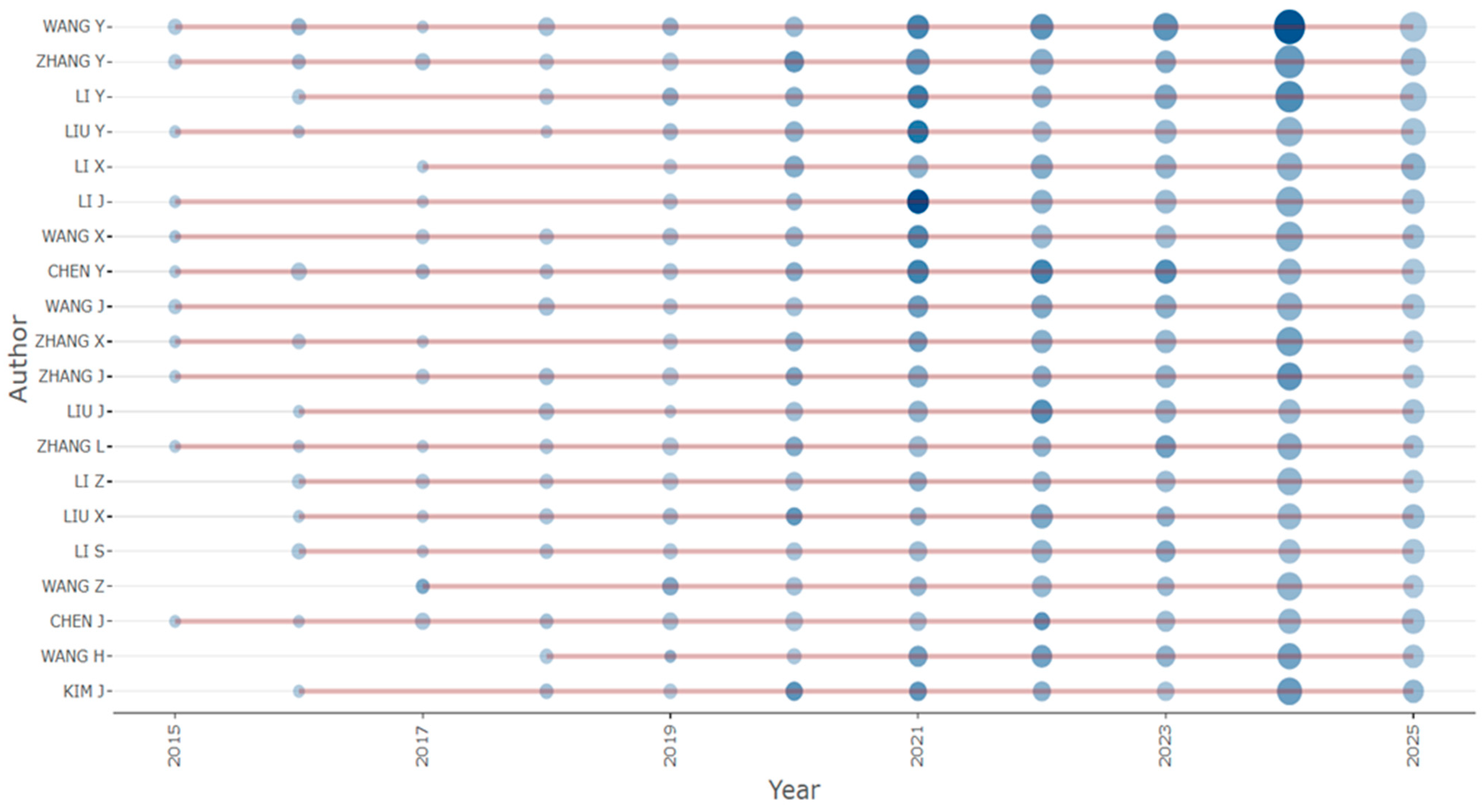

3.3. Impact of Authors on AI and HEIs (RQ3)

3.4. Authors’ Production on AI and HEIs (RQ3)

3.5. Most Local Cited References on AI and HEIs (RQ4)

3.6. Scientific Production and Countries (RQ1, RQ3)

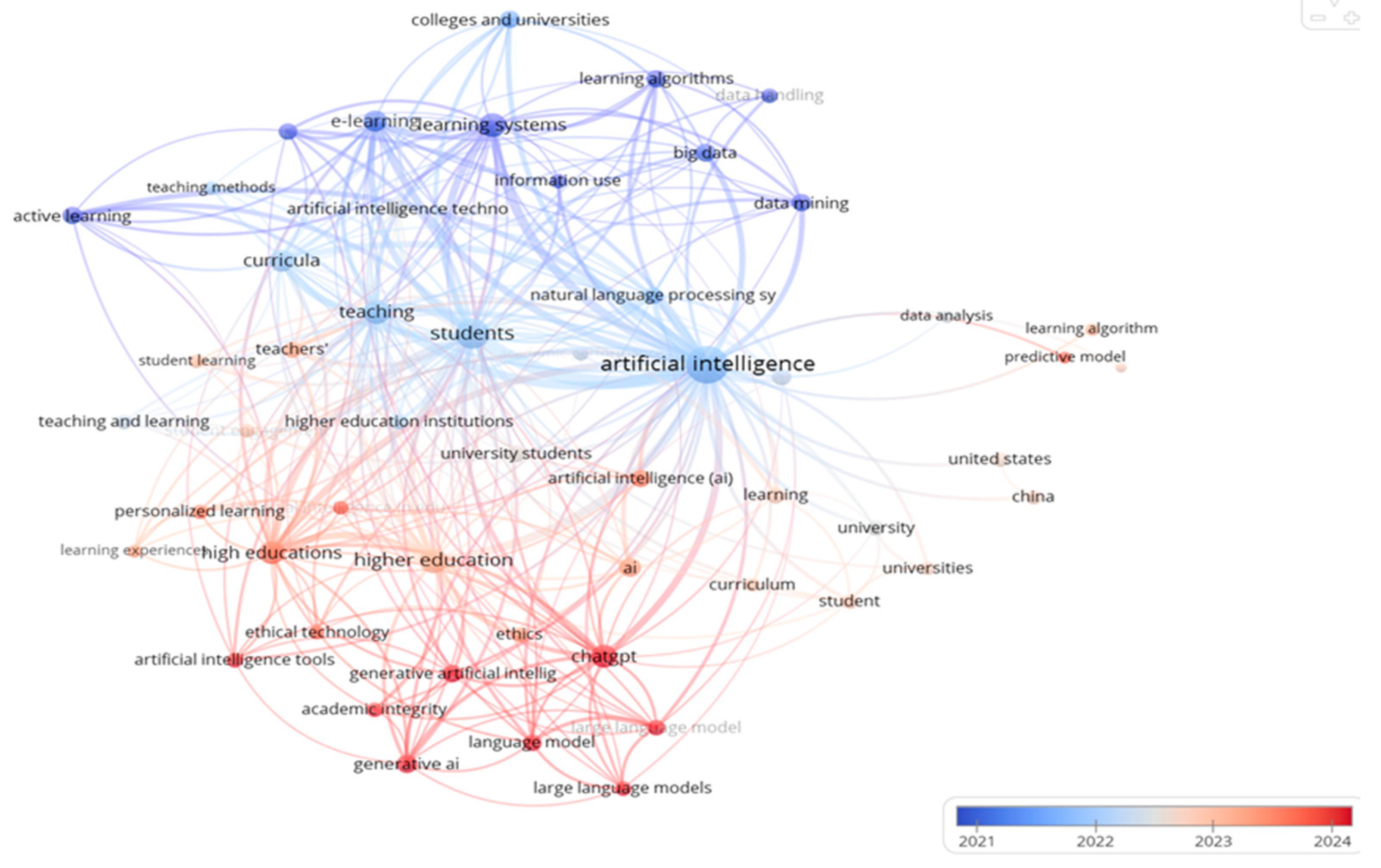

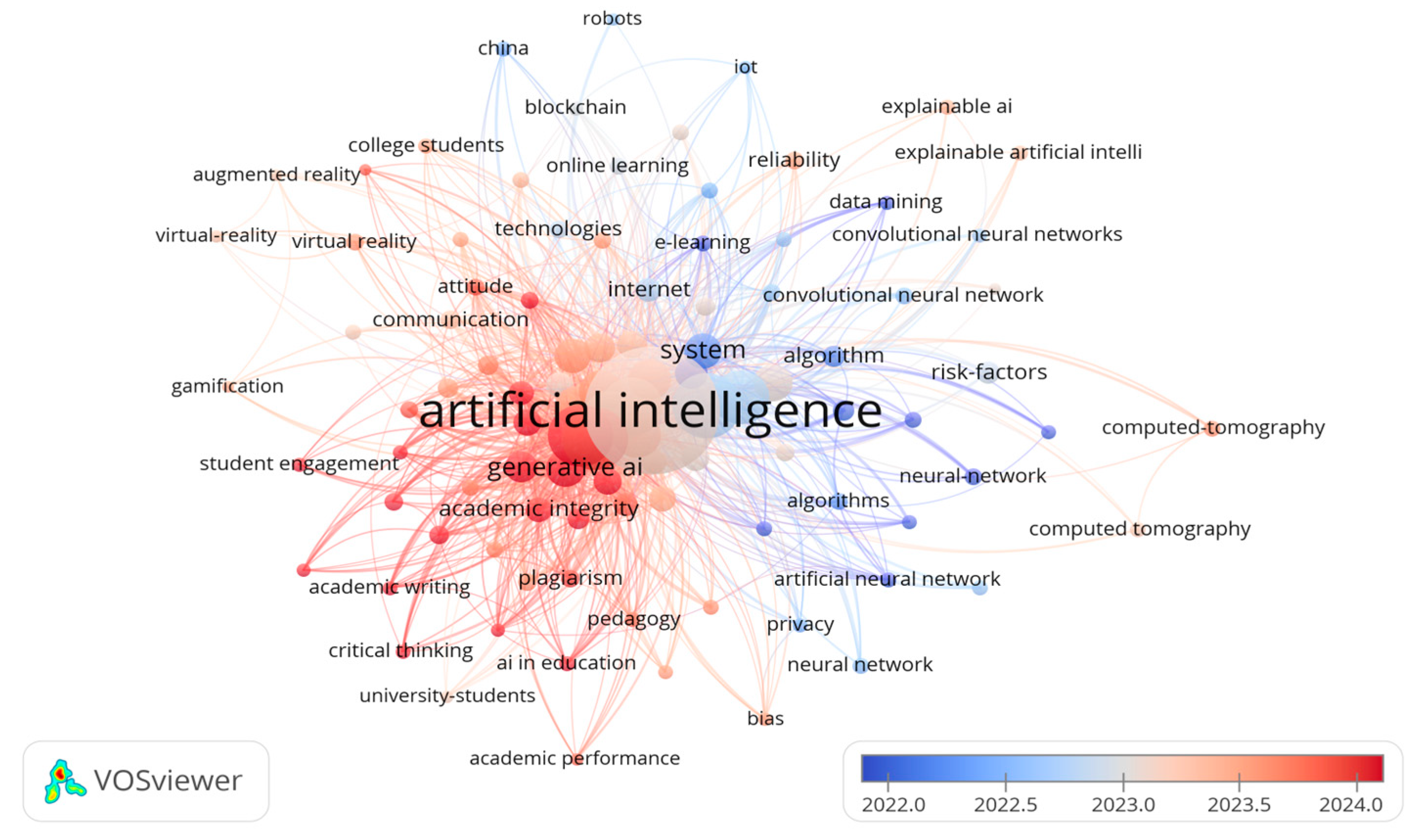

3.7. Keyword Co-Occurrence Analysis (RQ1)

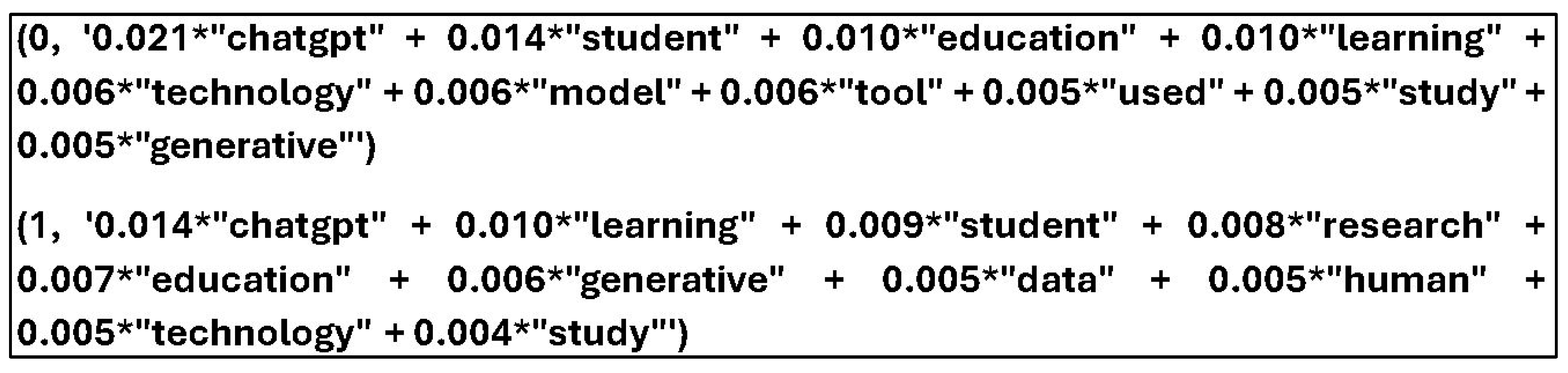

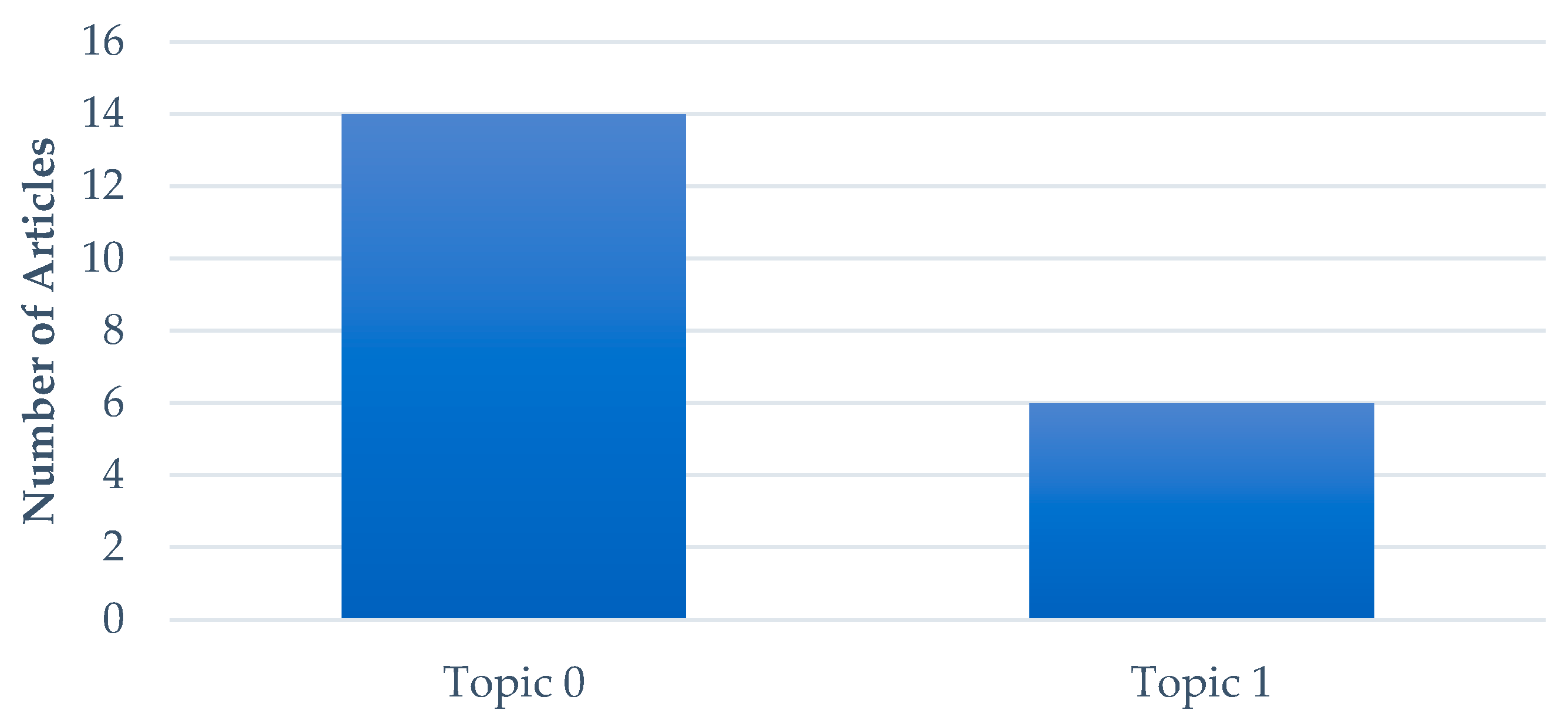

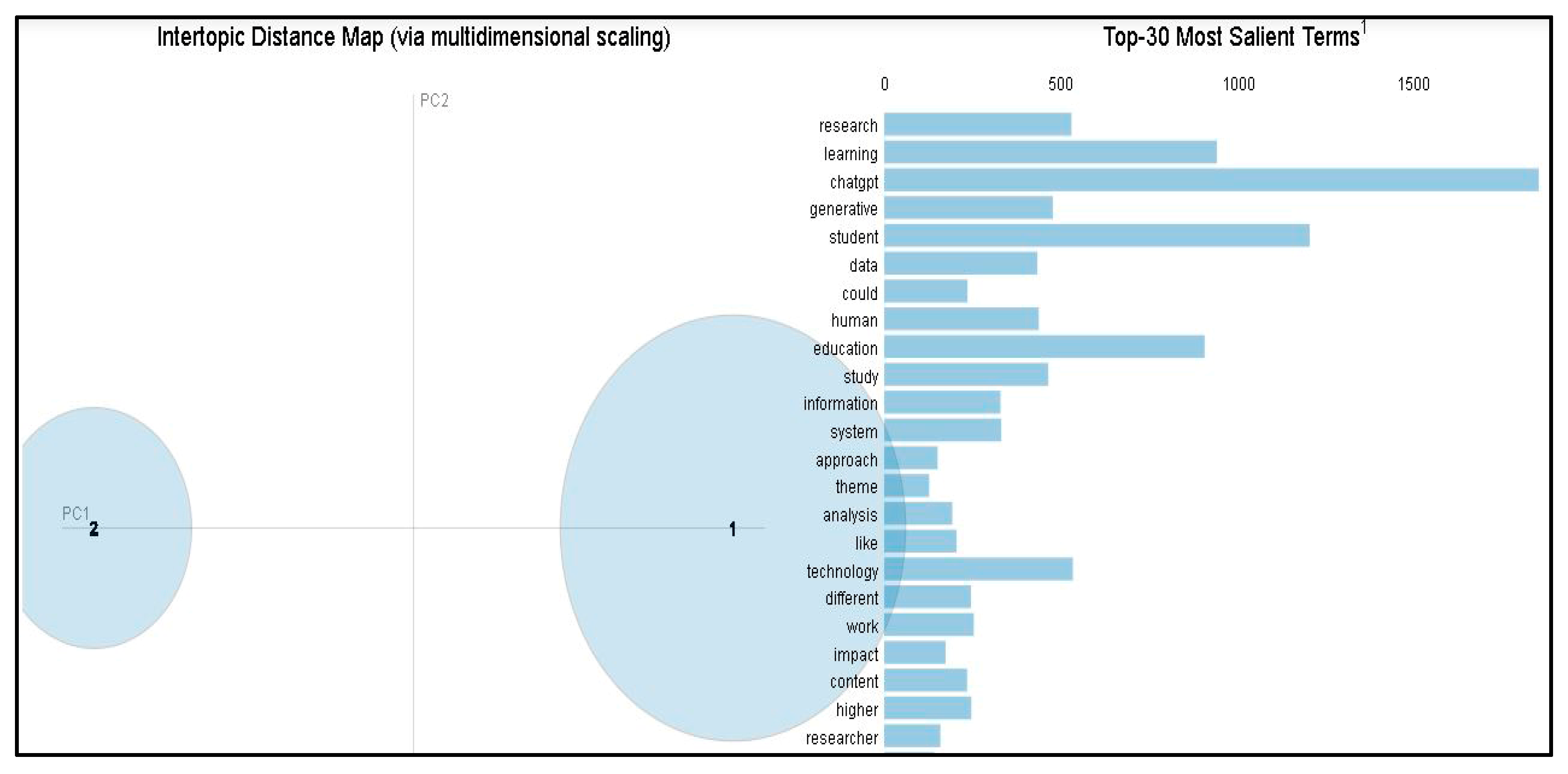

3.8. Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) Analysis (RQ1, RQ4)

4. Conclusions

5. Limitations and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| HE | Higher Education |

| HEIs | Higher Education Institutions |

| LDA | Latent Dirichlet Analysis |

| WoS | Web of Science |

References

- Lytras, M.D.; Serban, A.C.; Alkhaldi, A.; Aldosemani, T.; Malik, S. Digital transformation in higher education in times of artificial intelligence: Setting the emerging landscape. In Digital Transformation in Higher Education, Part A; Lytras, M.D., Serban, A.C., Alkhaldi, A., Malik, S., Aldosemani, T., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2024; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Javed, F. The evolution of artificial intelligence in teaching and learning of english language in higher education: Challenges, risks, and ethical considerations. In The Evolution of Artificial Intelligence in Higher Education; Lytras, M.D., Alkhaldi, A., Malik, S., Serban, A.C., Aldosemani, T., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2024; pp. 249–276. [Google Scholar]

- Albareda-Tiana, S.; Fernandez-Borsot, G.; Berbegal-Mirabent, J.; Regadera González, E.; Mas-Machuca, M.; Graell, M.; Manresa, A.; Fernández-Morilla, M.; Fuertes-Camacho, M.T.; Gutiérrez-Sierra, A.; et al. Enhancing curricular integration of the SDGs: Fostering active methodologies through cross-departmental collaboration in a Spanish university. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2024, 25, 1024–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, B.; Wooden, O. Managing the strategic transformation of higher education through artificial intelligence. Adm. Sci. 2023, 13, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamalov, F.; Santandreu Calonge, D.; Gurrib, I. New era of artificial intelligence in education: Towards a sustainable multifaceted revolution. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Teo, T.S.; Janssen, M. Public and private value creation using artificial intelligence: An empirical study of AI voice robot users in Chinese public sector. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 61, 102401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Rao, P.; Singhania, S.; Verma, S.; Kheterpal, M. Will artificial intelligence drive the advancements in higher education? A tri-phased exploration. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2024, 201, 123258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, A.; Karadeniz, A.; Baneres, D.; Guerrero-Roldán, A.E.; Rodríguez, M.E. Artificial intelligence and reflections from educational landscape: A review of AI Studies in half a century. Sustainability 2021, 13, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisica, A.I.; Edu, T.; Zaharia, R.M.; Zaharia, R. Implementing artificial intelligence in higher education: Pros and cons from the perspectives of academics. Societies 2023, 13, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelletier, K.; Robert, J.; Muscanell, N.; McCormack, M.; Reeves, R.; Arbino, N.; Grajek, S. 2023 EDUCAUSE Horizon Report: Teaching and Learning Edition; Educause: Longmont, CO, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Eaton, S.E.; Keyhani, M. The pedagogical ethics: Navigating learning in a generative AI-augmented environment in a post-plagiarism era. In Navigating Generative AI in Higher Education: Ethical, Theoretical, and Practical Perspectives; Sabbaghan, S., Ed.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2025; pp. 160–178. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming, B. Artificial Intelligence: Threat or Opportunity. Available online: https://er.educause.edu/articles/2020/5/artificial-intelligence-threat-or-opportunity (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Weil, D. Digital Transformation 2.0: The Age of AI. Available online: https://er.educause.edu/articles/2024/2/digital-transformation-20-the-age-of-ai (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Sutton, R.S. John McCarthy’s definition of intelligence. J. Artif. Gen. Intell. 2020, 11, 66–67. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, D.K.; Kumar, A.; Sharma, K. Artificial Intelligence in Advance Manufacturing. Int. J. Multidiscip. Innov. Res. Methodol. 2024, 3, 77–79. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, E.V. The technological leap of AI and the Global South: Deepening asymmetries and the future of international security. In Research Handbook on Warfare and Artificial Intelligence; Geiß, R., Lahmann, H., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2024; pp. 370–387. [Google Scholar]

- Heleta, S.; Bagus, T. Sustainable development goals and higher education: Leaving many behind. High. Educ. 2021, 81, 163–177. [Google Scholar]

- Pradhan, P.; Subedi, D.R.; Khatiwada, D.; Joshi, K.K.; Kafle, S.; Chhetri, R.P.; Dhakal, S.; Gautam, A.P.; Khatiwada, P.P.; Mainaly, J. The COVID-19 pandemic not only poses challenges, but also opens opportunities for sustainable transformation. Earth’s Future 2021, 9, e2021EF001996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajaj, R.; Buheji, M.; Hassoun, A. Optimizing the readiness for industry 4.0 in fulfilling the Sustainable Development Goal 1: Focus on poverty elimination in Africa. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1393935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goralski, M.A.; Tan, T.K. Artificial intelligence: Poverty alleviation, healthcare, education, and reduced inequalities in a post-COVID world. In The Ethics of Artificial Intelligence for the Sustainable Development Goals; Mazzi, F., Floridi, L., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 97–113. [Google Scholar]

- Maja, P.W.; Meyer, J.; Von Solms, S. Development of smart rural village indicators in line with industry 4.0. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 152017–152033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, S.; Sanasam, R. Developmentalism, technocracy and legitimacy crises of humanities: A Third World perspective. Int. J. Comp. Educ. Dev. 2024, 26, 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Ahn, D. The Promise and Peril of ChatGPT in Higher Education: Opportunities, Challenges, and Design Implications. In Proceedings of the 2024 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honolulu, HI, USA, 11–16 May 2024; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Popenici, S. Artificial Intelligence and Learning Futures: Critical Narratives of Technology and Imagination in Higher Education; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Farrelly, T.; Baker, N. Generative artificial intelligence: Implications and considerations for higher education practice. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omarsaib, M. Integrating a digital pedagogy approach into online teaching: Are academic librarians at Universities of Technology in South Africa prepared? Inf. Learn. Sci. 2024, 126, 192–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aria, M.; Cuccurullo, C. Bibliometrix: An R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. J. Informetr. 2017, 11, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranckutė, R. Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus: The titans of bibliographic information in today’s academic world. Publications 2021, 9, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, A.F.; Laurindo, F.J.; Spínola, M.M.; Gonçalves, R.F.; Mattos, C.A. The strategic use of artificial intelligence in the digital era: Systematic literature review and future research directions. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 57, 102225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Liu, W. A tale of two databases: The use of Web of Science and Scopus in academic papers. Scientometrics 2020, 123, 321–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moral-Muñoz, J.A.; Herrera-Viedma, E.; Santisteban-Espejo, A.; Cobo, M.J. Software tools for conducting bibliometric analysis in science: An up-to-date review. Prof. Inf. 2020, 29, e290103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graven, O.H.; MacKinnon, L. Developing Higher Education—Post-Pandemic—Influenced by AI. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE), College Station, TX, USA, 18–21 October 2023; pp. 01–08. [Google Scholar]

- Crompton, H.; Burke, D. Artificial intelligence in higher education: The state of the field. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2023, 20, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilham, R.; Muhammad, I.; Aji, L.J.; Rizal, S.U.; Özbilen, F.M. Artificial intelligence research in education: A bibliometric analysis. J. Educ. Glob. 2023, 1, 45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Kavitha, K.; Joshith, V.; Rajeev, N.P.; Asha, S. Artificial Intelligence in Higher Education: A Bibliometric Approach. Eur. J. Educ. Res. 2024, 13, 1121–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Chila, R.; Llerena-Izquierdo, J.; Sumba-Nacipucha, N.; Cueva-Estrada, J. Artificial intelligence in higher education: An analysis of existing bibliometrics. Educ. Sci. 2023, 14, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maphosa, V.; Maphosa, M. Artificial intelligence in higher education: A bibliometric analysis and topic modeling approach. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 37, 2261730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawacki-Richter, O.; Marín, V.I.; Bond, M.; Gouverneur, F. Systematic review of research on artificial intelligence applications in higher education–where are the educators? Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2019, 16, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.S.; Umer, H.; Faruqe, F. Artificial intelligence for low income countries. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitriani, A.; Rosidah, R.; Zafrullah, Z. Biblioshiny: Implementation of artificial intelligence in education (1976–2023). J. Technol. Glob. 2023, 1, 11–25. [Google Scholar]

- Metli, A. Articles on education and artificial intelligence: A bibliometric analysis. J. Soc. Sci. Educ. 2023, 6, 279–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, M.; Silva, R.; Borges, A.P.; Franco, M.; Oliveira, C. Artificial intelligence: Threat or asset to academic integrity? A bibliometric analysis. Kybernetes 2024, 54, 2939–2970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannan, E.; Liu, S. AI: New source of competitiveness in higher education. Compet. Rev. Int. Bus. J. 2023, 33, 265–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, F.; Keykha, A. Identifying the opportunities and challenges of artificial intelligence in higher education: A qualitative study. J. Appl. Res. High. Educ. 2024, 16, 1228–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, F.; Zheng, L.; Jiao, P. Artificial intelligence in online higher education: A systematic review of empirical research from 2011 to 2020. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 27, 7893–7925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasara, M.T.; Mhlanga, D. Accelerating sustainable development goals in the wake of COVID-19: The role of higher education institutions in South Africa. Emerald Open Res. 2023, 1, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Kanaujia, A.; Lathabai, H.H.; Singh, V.K.; Mayr, P. Patterns in the growth and thematic evolution of Artificial Intelligence research: A study using Bradford distribution of productivity and Path Analysis. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 2024, 2024, 5511224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summers, E.G. Bradford’s law and the retrieval of reading research journal literature. Read. Res. Q. 1983, 19, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarathunga, P.A.B.H. Mapping social capital and unveiling emerging trends through systematic literature review and bibliometric analysis. J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Rev. 2025, 9, 133–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Singh, V.K. Quantitative estimation of trends in artificial intelligence research: A study of Bradford distributions using Leimkuhler model. J. Scientometr. Res. 2023, 12, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamrani, P.; Dorsch, I.; Stock, W.G. Do researchers know what the h-index is? And how do they estimate its importance? Scientometrics 2021, 126, 5489–5508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, J.E. An index to quantify an individual’s scientific research output. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 16569–16572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, U.; Shah, A. Topic modeling using latent Dirichlet allocation: A survey. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 2021, 54, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelodar, H.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, C.; Feng, X.; Jiang, X.; Li, Y.; Zhao, L. Latent Dirichlet allocation (LDA) and topic modeling: Models, applications, a survey. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2019, 78, 15169–15211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Commun. ACM 2017, 60, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteva, A.; Kuprel, B.; Novoa, R.A.; Ko, J.; Swetter, S.M.; Blau, H.M.; Thrun, S. Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer with deep neural networks. Nature 2017, 542, 115–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qual. Res. Psychol. 2021, 18, 328–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasneci, E.; Sessler, K.; Küchemann, S.; Bannert, M.; Dementieva, D.; Fischer, F.; Gasser, U.; Groh, G.; Günnemann, S.; Hüllermeier, E.; et al. ChatGPT for good? On opportunities and challenges of large language models for education. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2023, 103, 102274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Chen, P.; Lin, Z. Artificial Intelligence in Education: A Review. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 75264–75278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, Y.K.; Kshetri, N.; Hughes, L.; Slade, E.L.; Jeyaraj, A.; Kar, A.K.; Baabdullah, A.M.; Koohang, A.; Raghavan, V.; Ahuja, M.; et al. Opinion Paper: “So what if ChatGPT wrote it?” Multidisciplinary perspectives on opportunities, challenges and implications of generative conversational AI for research, practice and policy. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2023, 71, 102642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baidoo-Anu, D.; Ansah, L.O. Education in the era of generative artificial intelligence (AI): Understanding the potential benefits of ChatGPT in promoting teaching and learning. J. AI 2023, 7, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotton, D.R.E.; Cotton, P.A.; Shipway, J.R. Chatting and cheating: Ensuring academic integrity in the era of ChatGPT. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2024, 61, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, J.; Tan, S.; Tan, S. ChatGPT: Bullshit spewer or the end of traditional assessments in higher education? J. Appl. Learn. Teach. 2023, 6, 342–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popenici, S.A.D.; Kerr, S. Exploring the impact of artificial intelligence on teaching and learning in higher education. Res. Pract. Technol. Enhanc. Learn. 2017, 12, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, C.K. What Is the Impact of ChatGPT on Education? A Rapid Review of the Literature. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tlili, A.; Shehata, B.; Adarkwah, M.A.; Bozkurt, A.; Hickey, D.T.; Huang, R.; Agyemang, B. What if the devil is my guardian angel: ChatGPT as a case study of using chatbots in education. Smart Learn. Environ. 2023, 10, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.K.Y.; Hu, W. Students’ voices on generative AI: Perceptions, benefits, and challenges in higher education. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2023, 20, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W.M.; Gunasekara, A.; Pallant, J.L.; Pallant, J.I.; Pechenkina, E. Generative AI and the future of education: Ragnarök or reformation? A paradoxical perspective from management educators. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2023, 21, 100790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrokhnia, M.; Banihashem, S.K.; Noroozi, O.; Wals, A. A SWOT analysis of ChatGPT: Implications for educational practice and research. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2024, 61, 460–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, G. Examining Science Education in ChatGPT: An Exploratory Study of Generative Artificial Intelligence. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 2023, 32, 444–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, M.; Kelly, A.; McLaughlan, P. ChatGPT in higher education: Considerations for academic integrity and student learning. J. Appl. Learn. Teach. 2023, 6, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avelar, A.B.A.; da Silva Oliveira, K.D.; Farina, M.C. The integration of the Sustainable Development Goals into curricula, research and partnerships in higher education. Int. Rev. Educ. 2023, 69, 299–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Citation-based clustering of publications using CitNetExplorer and VOSviewer. Scientometrics 2017, 111, 1053–1070. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Z.; Amayri, M.; Fan, W.; Ihou, K.E.; Bouguila, N. Parallel inference for cross-collection latent generalized Dirichlet allocation model and applications. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 238, 121720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, C.; Batra, I.; Sharma, S.; Malik, A.; Hosen, A.S.; Ra, I.-H. Predicting trends and research patterns of smart cities: A semi-automatic review using latent dirichlet allocation (LDA). IEEE Access 2022, 10, 121080–121095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayan, R. Teaching and learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: A topic modeling study. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Mara-Eves, A.; Thomas, J.; McNaught, J.; Miwa, M.; Ananiadou, S. Using text mining for study identification in systematic reviews: A systematic review of current approaches. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulkarnain; Putri, T.D. Intelligent transportation systems (ITS): A systematic review using a Natural Language Processing (NLP) approach. Heliyon 2021, 7, e08615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacinger, F.; Boticki, I.; Mlinaric, D. System for semi-automated literature review based on machine learning. Electronics 2022, 11, 4124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswanathan, M.; Patnode, C.D.; Berkman, N.D.; Bass, E.B.; Chang, S.; Hartling, L.; Murad, M.H.; Treadwell, J.R.; Kane, R.L. Assessing the risk of bias in systematic reviews of health care interventions. In Methods Guide for Effectiveness and Comparative Effectiveness Reviews; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- De Jong, R.; Bus, D. VOSviewer: Putting Research into Context. Available online: https://researchsoftware.pubpub.org/pub/j3sr4bo9/release/2 (accessed on 5 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Huo, R.; Yao, J. Evaluation of stability and similarity of latent dirichlet allocation. In Proceedings of the 2013 Fourth World Congress on Software Engineering, Hong Kong, China, 3–4 December 2013; pp. 78–83. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Chau, K.Y.; Chan, H.S.; Wan, Y. A visualisation analysis using the vosviewer of literature on virtual reality technology application in healthcare. In Cases on Virtual Reality Modeling in Healthcare; Tang, Y.M., Lun, H.H., Chau, K.Y., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2022; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Rowley, M.; Barfield, W.; Rivas, G.; Reid, K.; Hartsock, L. Analysis of the orthopaedic trauma literature utilizing machine learning and latent dirichlet allocation. Curr. Orthop. Pract. 2024, 35, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Concept one—AI and related terms | AI OR “artificial intelligence” |

| AND | |

| Concept two—Higher education and related terms | universit* OR “academic institution*” OR college* OR “higher education” OR “tertiary institution*” |

| NOT | |

| Concept three | “Apnea index” OR “American Indian*” OR “Aromatase inhibitors” OR “acetabular index” OR “ai ha” |

| Journals | Freq | cumFreq | Zone |

|---|---|---|---|

| Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing | 197 | 1949 | Zone 1 |

| Communications in Computer and Information Science | 193 | 2142 | Zone 1 |

| Education and Information Technologies | 191 | 2333 | Zone 1 |

| Clinical Radiology | 181 | 2514 | Zone 1 |

| Applied Mathematics and Nonlinear Sciences | 143 | 2811 | Zone 1 |

| Radiography | 129 | 2940 | Zone 1 |

| Sustainability | 129 | 3069 | Zone 1 |

| Education Sciences | 115 | 3301 | Zone 1 |

| Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence | 106 | 3515 | Zone 1 |

| Procedia Computer Science | 99 | 3614 | Zone 1 |

| Scientific Reports | 96 | 3710 | Zone 1 |

| Applied Sciences-Basel | 85 | 3795 | Zone 1 |

| Egyptian Informatics Journal | 83 | 3878 | Zone 1 |

| Business Horizons | 78 | 3956 | Zone 1 |

| Clinical Oncology | 77 | 4033 | Zone 1 |

| Frontiers in Education | 77 | 4110 | Zone 1 |

| Frontiers in Psychology | 69 | 4395 | Zone 1 |

| Engineering | 68 | 4463 | Zone 1 |

| PLOS One | 68 | 4531 | Zone 1 |

| Academic Radiology | 62 | 4726 | Zone 1 |

| Author | H-Index | Total Citations | Net Production | Publication Year Start |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wang Y | 26 | 2576 | 261 | 2015 |

| Li Y | 22 | 1854 | 192 | 2016 |

| Chen Y | 21 | 2208 | 152 | 2015 |

| Zhang Y | 21 | 1989 | 225 | 2015 |

| Li J | 19 | 1751 | 157 | 2015 |

| Khan M | 18 | 1228 | 58 | 2018 |

| Kim J | 18 | 1608 | 100 | 2016 |

| Liu C | 18 | 1221 | 62 | 2015 |

| Wang J | 18 | 1165 | 149 | 2015 |

| Zhang J | 18 | 1302 | 130 | 2015 |

| Kim Y | 17 | 1103 | 73 | 2016 |

| Lee J | 17 | 1050 | 86 | 2016 |

| Liu J | 17 | 1003 | 120 | 2016 |

| Liu X | 17 | 1374 | 113 | 2016 |

| Wang H | 17 | 1312 | 105 | 2018 |

| Wang X | 17 | 1345 | 157 | 2015 |

| Zhang L | 17 | 1049 | 118 | 2015 |

| Li X | 16 | 975 | 162 | 2017 |

| Liu Y | 16 | 1468 | 164 | 2015 |

| Zhang X | 16 | 1110 | 135 | 2015 |

| Chen J | 15 | 991 | 105 | 2015 |

| Li H | 15 | 813 | 98 | 2016 |

| Wang Z | 15 | 1496 | 110 | 2017 |

| Huang Y | 14 | 920 | 74 | 2017 |

| Kim H | 14 | 908 | 64 | 2016 |

| Topic | Theme | Keywords |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Generative AI Tools and Their Pedagogical Integration in Higher Education | chatgpt, student, education, learning, technology, model, tool, used, study, generative |

| 1 | Generative AI in Higher Education Research and Ethical Implications | chatgpt, learning, student, research, education, generative, data, human, technology, study |

| Study Identity | Dominant Topic | Topic Percentage Contribution |

|---|---|---|

| SI1 | 1 | 0.9833 |

| SI2 | 1 | 0.8040 |

| SI3 | 1 | 0.9990 |

| SI4 | 1 | 0.9998 |

| SI5 | 0 | 0.9971 |

| SI6 | 1 | 0.8574 |

| SI7 | 0 | 0.9668 |

| SI8 | 0 | 0.7909 |

| SI9 | 0 | 0.9985 |

| SI10 | 0 | 0.9966 |

| SI11 | 0 | 0.9989 |

| SI12 | 1 | 0.7459 |

| SI13 | 0 | 0.9992 |

| SI14 | 0 | 0.8610 |

| SI15 | 0 | 0.9454 |

| SI16 | 0 | 0.6592 |

| SI17 | 0 | 0.9954 |

| SI18 | 0 | 0.9193 |

| SI19 | 0 | 0.9228 |

| SI20 | 0 | 0.9991 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Omarsaib, M.; Mitha, S.B.; Vahed, A.; Mohamed, G.M. Mapping the AI Surge in Higher Education: A Bibliometric Study Spanning a Decade (2015–2025). Informatics 2025, 12, 137. https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics12040137

Omarsaib M, Mitha SB, Vahed A, Mohamed GM. Mapping the AI Surge in Higher Education: A Bibliometric Study Spanning a Decade (2015–2025). Informatics. 2025; 12(4):137. https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics12040137

Chicago/Turabian StyleOmarsaib, Mousin, Sara Bibi Mitha, Anisa Vahed, and Ghulam Masudh Mohamed. 2025. "Mapping the AI Surge in Higher Education: A Bibliometric Study Spanning a Decade (2015–2025)" Informatics 12, no. 4: 137. https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics12040137

APA StyleOmarsaib, M., Mitha, S. B., Vahed, A., & Mohamed, G. M. (2025). Mapping the AI Surge in Higher Education: A Bibliometric Study Spanning a Decade (2015–2025). Informatics, 12(4), 137. https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics12040137