Podocalyxin, Isthmin-1, and Pentraxin-3 Immunoreactivities as Emerging Immunohistochemical Markers of Fibrosis in Chronic Hepatitis B

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

- Participants were included in the study if they met all of the following conditions:

- Aged 18 years or older;

- Underwent liver biopsy for the diagnosis of chronic hepatitis B, with pretreatment histopathological evaluation of fibrosis by the pathology department;

- No co-infections known to affect liver fibrosis, such as hepatitis C virus (HCV) or hepatitis D virus (HDV);

- No evidence of acute hepatitis at the time of liver biopsy;

- No diagnosis of acute exacerbation of chronic hepatitis at the time of liver biopsy;

- Absence of any concurrent malignancy;

- Not receiving immunosuppressive therapy;

- No co-infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV);

- Not on medication for any chronic systemic illness (e.g., hypertension, diabetes mellitus);

- No additional condition that could contribute to chronic hepatic ischemia;

- No history of direct surgical intervention involving the liver.

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

- Younger than 18 years of age;

- Did not undergo liver biopsy for the diagnosis of chronic hepatitis B;

- Presence of co-infection affecting liver fibrosis (e.g., HCV or HDV);

- Diagnosis of acute hepatitis at the time of liver biopsy;

- Diagnosis of acute exacerbation of chronic hepatitis at the time of liver biopsy;

- Presence of concurrent malignancy;

- Currently receiving immunosuppressive therapy;

- Co-infection with HIV and undergoing treatment for it;

- Receiving medication for any chronic systemic illness (e.g., hypertension, diabetes mellitus);

- Presence of comorbidities that may contribute to chronic hepatic ischemia (e.g., congestive heart failure, cardiac arrhythmias, arterial ischemia);

- History of direct surgical intervention involving the liver.

2.4. Evaluation of Liver Fibrosis

- F0: No fibrosis;

- F1: Fibrous expansion in some portal areas;

- F2: Fibrous expansion in most portal areas;

- F3: Fibrous expansion in most portal areas with occasional portal–portal bridging;

- F4: Marked portal–portal and portal–central bridging;

- F5: Extensive bridging with occasional nodules (incomplete cirrhosis);

- F6: Cirrhosis.

2.5. Immunohistochemistry

2.6. Evaluation of Immunoreactivity

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

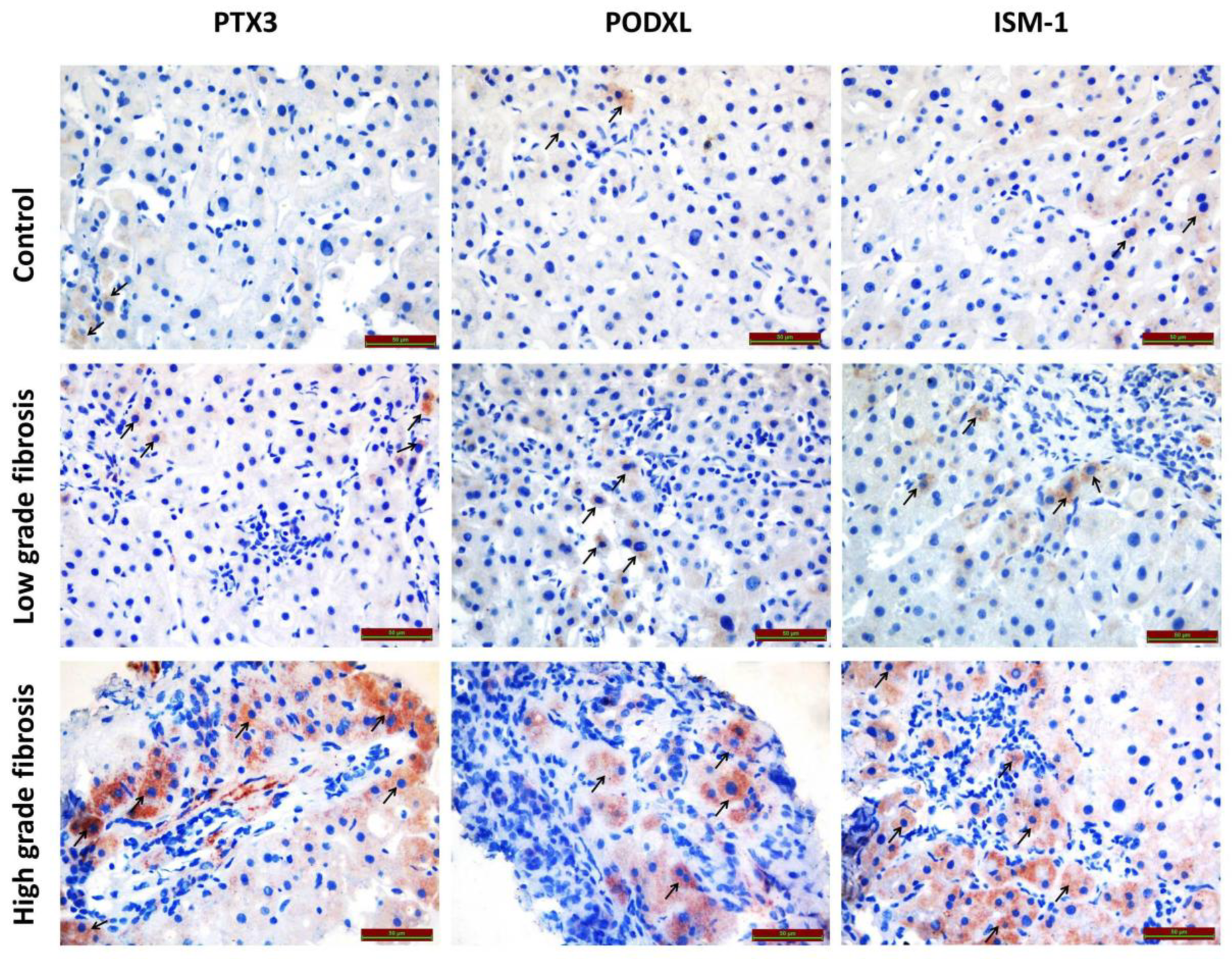

3.1. Immunohistochemical Findings

3.1.1. PODXL Immunoreactivity

3.1.2. PTX3 Immunoreactivity

3.1.3. ISM1 Immunoreactivity

4. Discussion

5. Limitation of Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Global Hepatitis Report 2024: Action for Access in Low- and Middle-Income Countries; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240091672 (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Higashi, T.; Friedman, S.L.; Hoshida, Y. Hepatic stellate cells as key target in liver fibrosis. Adv. Drug Deli.v Rev. 2017, 121, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koyama, Y.; Brenner, D.A. Liver inflammation and fibrosis. J. Clin. Investig. 2017, 127, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemoinne, S.; Thabut, D.; Housset, C. Portal myofibroblasts connect angiogenesis and fibrosis in liver. Cell Tissue Res. 2016, 365, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosselli, M.; MacNaughtan, J.; Jalan, R.; Pinzani, M. Beyond scoring: A modern interpretation of disease progression in chronic liver disease. Gut 2013, 62, 1234–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGlynn, K.A.; Petrick, J.L.; London, W.T. Global epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma: An emphasis on demographic and regional variability. Clin. Liver Dis. 2015, 19, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krenkel, O.; Tacke, F. Liver macrophages in tissue homeostasis and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2017, 17, 306–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novo, E.; Cannito, S.; Paternostro, C.; Bocca, C.; Miglietta, A.; Parola, M. Cellular and molecular mechanisms in liver fibrogenesis. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2014, 548, 20–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerjaschki, D.; Sharkey, D.J.; Farquhar, M.G. Identification and characterization of podocalyxin—the major sialoprotein of the renal glomerular epithelial cell. J. Cell Biol. 1984, 98, 1591–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Tran, N.; Wang, Y.; Nie, G. Podocalyxin in Normal Tissue and Epithelial Cancer. Cancers 2021, 13, 2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voltz, J.W.; Weinman, E.J.; Shenolikar, S. Expanding the role of NHERF, a PDZ-domain containing protein adapter, to growth regulation. Oncogene 2001, 20, 6309–6314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, H.; Fan, X.; Wang, X.; Zeng, L.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, X.; Li, N.; Han, Q.; Lv, Y.; Liu, Z. Serum pentraxin 3 as a biomarker of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 20276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boga, S.; Koksal, A.R.; Alkim, H.; Yilmaz Ozguven, M.B.; Bayram, M.; Ergun, M.; Sisman, G.; Tekin Neijmann, S.; Alkim, C. Plasma Pentraxin 3 Differentiates Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis (NASH) from Non-NASH. Metab. Syndr. Relat. Disord. 2015, 13, 393–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, D.G.; Lee, P.; Pryde, E.A.; Walker, S.W.; Beckett, G.J.; Hayes, P.C.; Simpson, K.J. Elevated levels of the long pentraxin 3 in paracetamol-induced human acute liver injury. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013, 25, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorka-Dynysiewicz, J.; Pazgan-Simon, M.; Zuwala-Jagiello, J. Pentraxin 3 Detects Clinically Significant Fibrosis in Patients with Chronic Viral Hepatitis, C. BioMed Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 2639248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmo, R.F.; Aroucha, D.; Vasconcelos, L.R.; Pereira, L.M.; Moura, P.; Cavalcanti, M.S. Genetic variation in PTX3 and plasma levels associated with hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with HCV. J. Viral Hepat. 2016, 23, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osório, L.; Wu, X.; Zhou, Z. Distinct spatiotemporal expression of ISM1 during mouse and chick development. Cell Cycle 2014, 13, 1571–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valle-Rios, R.; Maravillas-Montero, J.L.; Burkhardt, A.M.; Martinez, C.; Buhren, B.A.; Homey, B.; Gerber, P.A.; Robinson, O.; Hevezi, P.; Zlotnik, A. Isthmin 1 is a secreted protein expressed in skin, mucosal tissues, and NK, NKT, and th17 cells. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 2014, 34, 795–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishak, K.; Baptista, A.; Bianchi, L.; Callea, F.; De Groote, J.; Gudat, F.; Denkg, H.; Desmeth, V.; Korbi, G.; MacSween, R.N.M.; et al. Histological grading and staging of chronic hepatitis. J. Hepatol. 1995, 22, 696–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydın, M.M.; Akçalı, K.C. Liver fibrosis. Turk. J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 29, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poisson, J.; Lemoinne, S.; Boulanger, C.; Durand, F.; Moreau, R.; Valla, D.; Rautou, P.E. Liver sinusoidal endothelial cells: Physiology and role in liver diseases. J. Hepatol. 2017, 66, 212–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Hu, M.; Chen, Z.; Ling, Z. The roles and mechanisms of hypoxia in liver fibrosis. J. Transl. Med. 2021, 19, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyonnas, R.; Kershaw, D.B.; Duhme, C.; Merkens, H.; Chelliah, S.; Graf, T.; McNagny, K.M. Anuria, omphalocele, and perinatal lethality in mice lacking the CD34-related protein podocalyxin. J. Exp. Med. 2001, 194, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paule, S.G.; Heng, S.; Samarajeewa, N.; Li, Y.; Mansilla, M.; Webb, A.I.; Nebl, T.; Young, S.L.; Lessey, B.A.; Hull, M.L.; et al. Podocalyxin is a key negative regulator of human endometrial epithelial receptivity for embryo implantation. Hum. Reprod. 2021, 36, 1353–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sizemore, S.; Cicek, M.; Sizemore, N.; Ng, K.P.; Casey, G. Podocalyxin increases the aggressive phenotype of breast and prostate cancer cells in vitro through its interaction with ezrin. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 6183–6191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cipollone, J.A.; Graves, M.L.; Köbel, M.; Kalloger, S.E.; Poon, T.; Gilks, C.B.; McNagny, K.M.; Roskelley, C.D. The anti-adhesive mucin podocalyxin may help initiate the transperitoneal metastasis of high grade serous ovarian carcinoma. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 2012, 29, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maltby, S.; Freeman, S.; Gold, M.J.; Baker, J.H.; Minchinton, A.I.; Gold, M.R.; Roskelley, C.D.; McNagny, K.M. Opposing roles for CD34 in B16 melanoma tumor growth alter early stage vasculature and late stage immune cell infiltration. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e18160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heukamp, L.C.; Fischer, H.P.; Schirmacher, P.; Chen, X.; Breuhahn, K.; Nicolay, C.; Büttner, R.; Gütgemann, I. Podocalyxin-like protein 1 expression in primary hepatic tumours and tumour-like lesions. Histopathology 2006, 49, 242–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Téllez, T.N.; Lopez, T.V.; Vásquez Garzón, V.R.; Villa-Treviño, S. Co-Expression of Ezrin-CLIC5-Podocalyxin Is Associated with Migration and Invasiveness in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0131605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Higgins, J.; Cheung, S.T.; Li, R.; Mason, V.; Montgomery, K.; Fan, S.T.; van de Rijn, M.; So, S. Novel endothelial cell markers in hepatocellular carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2004, 17, 1198–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishayee, A. The role of inflammation and liver cancer. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2014, 816, 401–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.W.; Lee, T.H.; Vilcek, J. TSG-14, a tumor necrosis factor- and IL-1-inducible protein, is a novel member of the pentaxin family of acute phase proteins. J. Immunol. 1993, 150, 1804–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxena, R.; Chawla, Y.K.; Verma, I.; Kaur, J. Interleukin-1 polymorphism and expression in hepatitis B virus-mediated disease outcome in India. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 2013, 33, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doni, A.; Michela, M.; Bottazzi, B.; Peri, G.; Valentino, S.; Polentarutti, N.; Garlanda, C.; Mantovani, A. Regulation of PTX3, a key component of humoral innate immunity in human dendritic cells: Stimulation by IL-10 and inhibition by IFN-gamma. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2006, 79, 797–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxena, R.; Chawla, Y.K.; Verma, I.; Kaur, J. Association of interleukin-10 with hepatitis B virus (HBV) mediated disease progression in Indian population. Indian J. Med. Res. 2014, 139, 737–745. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Xue, H.; Lin, F.; Tan, H.; Zhu, Z.Q.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Zhao, L. Overrepresentation of IL-10-Expressing B Cells Suppresses Cytotoxic CD4+ T Cell Activity in HBV-Induced Hepatocellular Carcinoma. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0154815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, T.; Wang, C.; Guo, C.; Liu, Q.; Zheng, X. Pentraxin 3 overexpression accelerated tumor metastasis and indicated poor prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma via driving epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J. Cancer 2018, 9, 2650–2658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoneda, M.; Uchiyama, T.; Kato, S.; Endo, H.; Fujita, K.; Yoneda, K.; Mawatari, H.; Iida, H.; Takahashi, H.; Kirikoshi, H.; et al. Plasma Pentraxin3 is a novel marker for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). BMC Gastroenterol 2008, 8, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.Y.; Wei, H.J.; Tang, Y.Y. Isthmin: A multifunctional secretion protein. Cytokine 2024, 173, 156423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Zhao, M.; Voilquin, L.; Jung, Y.; Aikio, M.A.; Sahai, T.; Dou, F.Y.; Roche, A.M.; Carcamo-Orive, I.; Knowles, J.W.; et al. Isthmin-1 is an adipokine that promotes glucose uptake and improves glucose tolerance and hepatic steatosis. Cell Metab. 2021, 33, 1836–1852.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menghuan, L.; Yang, Y.; Qianhe, M.; Na, Z.; Shicheng, C.; Bo, C.; XueJie, Y.I. Advances in research of biological functions of Isthmin-1. J. Cell Commun. Signal. 2023, 17, 507–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, V.C.; Chong, Y.S.; Yoshioka, T.; Ge, R. Isthmin targets cell-surface GRP78 and triggers apoptosis via induction of mitochondrial dysfunction. Cell Death Differ. 2014, 21, 797–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, B.; Xian, R.; Ma, J.; Chen, Y.; Lin, C.; Song, Y. Isthmin inhibits glioma growth through antiangiogenesis in vivo. J. Neuro-Oncol. 2012, 109, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harada, H.; Sato, T.; Nakamura, H. Fgf8 signaling for development of the midbrain and hindbrain. Dev. Growth Differ. 2016, 58, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pera, E.M.; Kim, J.I.; Martinez, S.L.; Brechner, M.; Li, S.Y.; Wessely, O.; De Robertis, E.M. Isthmin is a novel secreted protein expressed as part of the Fgf-8 synexpression group in the Xenopus midbrain-hindbrain organizer. Mech Dev. 2002, 116, 169–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kesavan, G.; Raible, F.; Gupta, M.; Machate, A.; Yilmaz, D.; Brand, M. Isthmin1, a secreted signaling protein, acts downstream of diverse embryonic patterning centers in development. Cell Tissue Res. 2021, 383, 987–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Liang, X.; Ni, J.; Zhao, R.; Shao, S.; Lu, S.; Han, W.; Yu, L. Effect of ISM1 on the Immune Microenvironment and Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Colorectal Cancer. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 681240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Low-Grade Fibrosis (n = 21) (Mean ± STD) | High-Grade Fibrosis (n = 21) (Mean ± STD) | Total (Mean ± STD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Mean) | 36.7 ± 10.2 | 47.5 ± 15.4 | 42.1 ± 14.0 |

| Sex (F/M) | 8/13 | 4/17 | 12/30 |

| AST (U/L) | 27.4 ± 9.4 | 63.0 ± 51.4 | 45.2 ± 41.0 |

| ALT (U/L) | 35.4 ± 26.0 | 91.8 ± 93.9 | 63.6 ± 74.5 |

| Total protein (g/L) | 71.5 ± 3.3 | 71.5 ± 5.8 | 72.0 ± 4.7 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 42.8 ± 2.1 | 41.5 ± 4.7 | 42.1 ± 3.7 |

| INR | 1.03 ± 0.07 | 1.05 ± 0.09 | 1.04 ± 0.08 |

| ALP (U/L) | 82.5 ± 29.3 | 86.1 ± 23.8 | 84.3 ± 26.8 |

| GGT (U/L) | 16.0± 4.9 | 24.9 ± 16.3 | 20.7 ± 12.7 |

| Platelet count (109/L) | 239 ± 37 | 194 ± 42.9 | 216 ± 45 |

| HBV DNA IU/mL | 200,265 ± 702,864 | 76,300,956 ± 120,670,886 | 38,250,611 ± 93,428,085 |

| HBeAg positive/negative | 1/20 | 6/15 | 7/35 |

| Immunoreactivity Histoscore | Control (n = 21) | Low-Grade Fibrosis (n = 21) | High-Grade Fibrosis (n = 21) | p Value * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PODXL | 0.29 ± 0.10 | 0.78 ± 0.21 a | 1.20 ± 0.63 b | <0.001 |

| PTX3 | 0.40 ± 0.08 | 0.74 ± 0.19 a | 1.01 ± 0.48 b | <0.001 |

| ISM1 | 0.46 ± 0.07 | 0.88 ± 0.47 a | 1.35 ± 0.75 b | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Özgüler, M.; Hançer, S.; Solmaz, Ö.A.; Kuloğlu, T. Podocalyxin, Isthmin-1, and Pentraxin-3 Immunoreactivities as Emerging Immunohistochemical Markers of Fibrosis in Chronic Hepatitis B. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2958. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122958

Özgüler M, Hançer S, Solmaz ÖA, Kuloğlu T. Podocalyxin, Isthmin-1, and Pentraxin-3 Immunoreactivities as Emerging Immunohistochemical Markers of Fibrosis in Chronic Hepatitis B. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(12):2958. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122958

Chicago/Turabian StyleÖzgüler, Müge, Serhat Hançer, Özgen Arslan Solmaz, and Tuncay Kuloğlu. 2025. "Podocalyxin, Isthmin-1, and Pentraxin-3 Immunoreactivities as Emerging Immunohistochemical Markers of Fibrosis in Chronic Hepatitis B" Biomedicines 13, no. 12: 2958. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122958

APA StyleÖzgüler, M., Hançer, S., Solmaz, Ö. A., & Kuloğlu, T. (2025). Podocalyxin, Isthmin-1, and Pentraxin-3 Immunoreactivities as Emerging Immunohistochemical Markers of Fibrosis in Chronic Hepatitis B. Biomedicines, 13(12), 2958. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122958