ZnO/rGO/ZnO Composites with Synergic Enhanced Gas Sensing Performance for O3 Detection with No Ozonolysis Process

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis of ZnO Nanoparticles

2.2. Sensor Manufacturing

2.3. Gas Sensor Measurements

2.4. Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Structural Characterization

3.2. Optical Characterization

3.3. Morphological Characterization

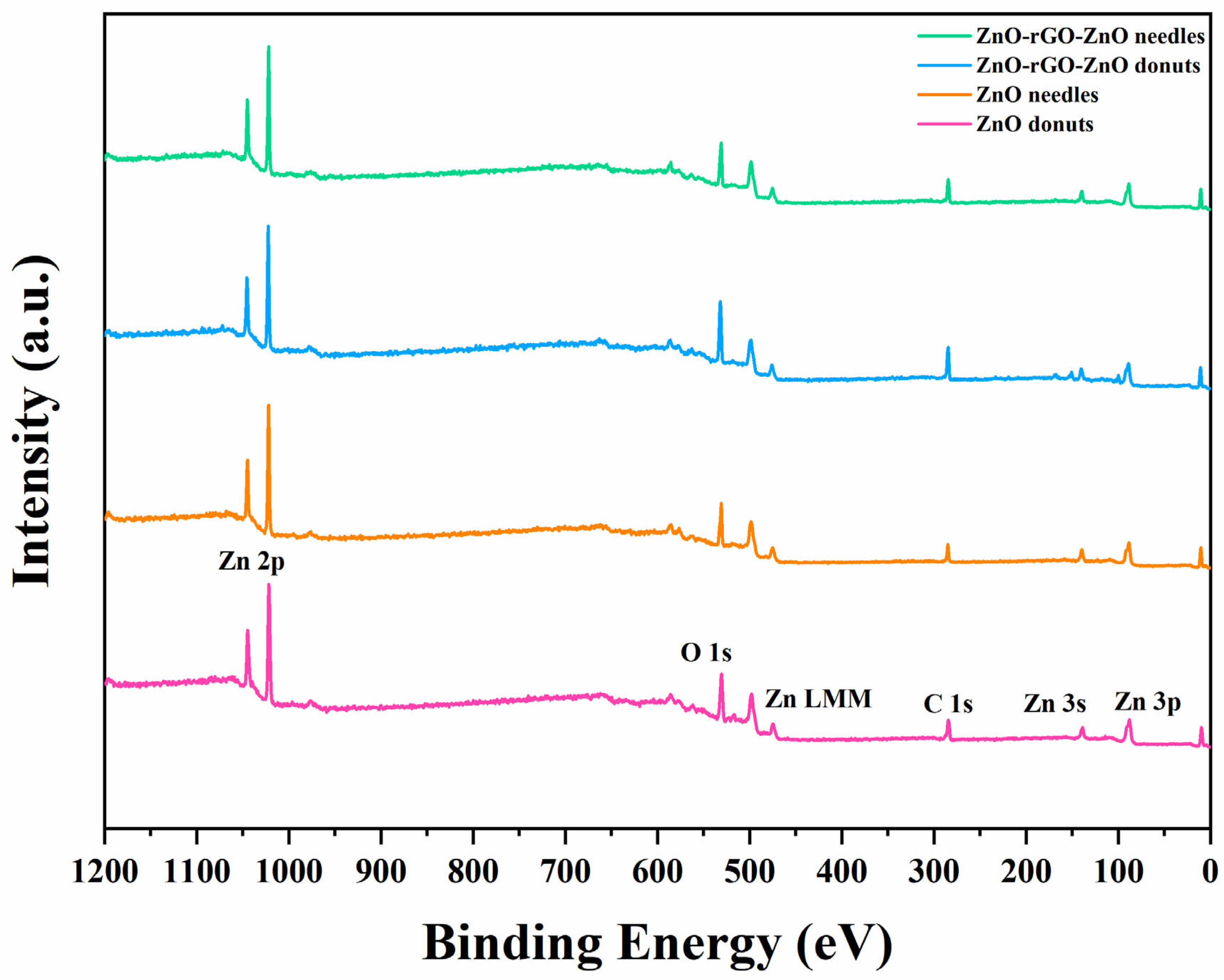

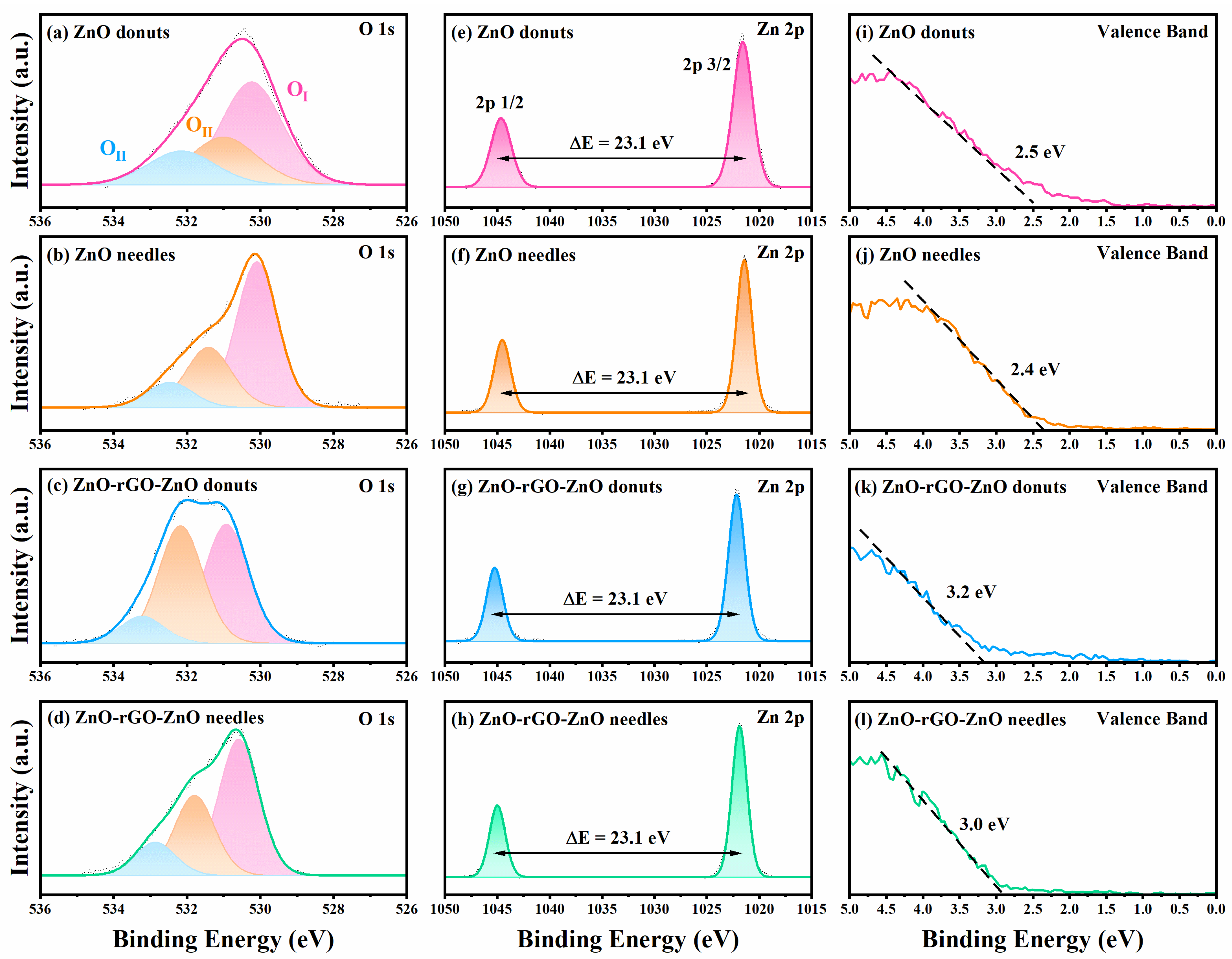

3.4. Chemical and Surface Characterization

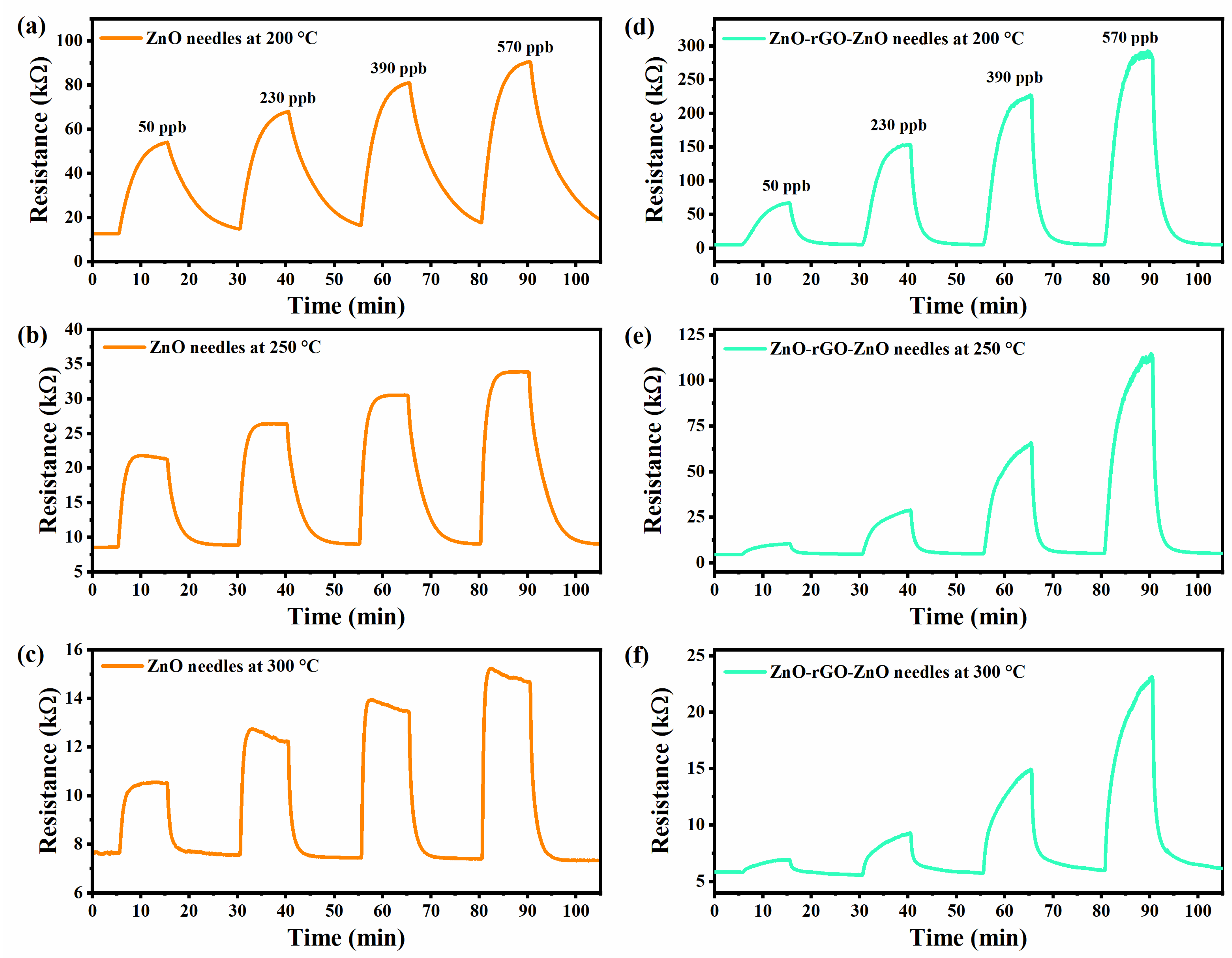

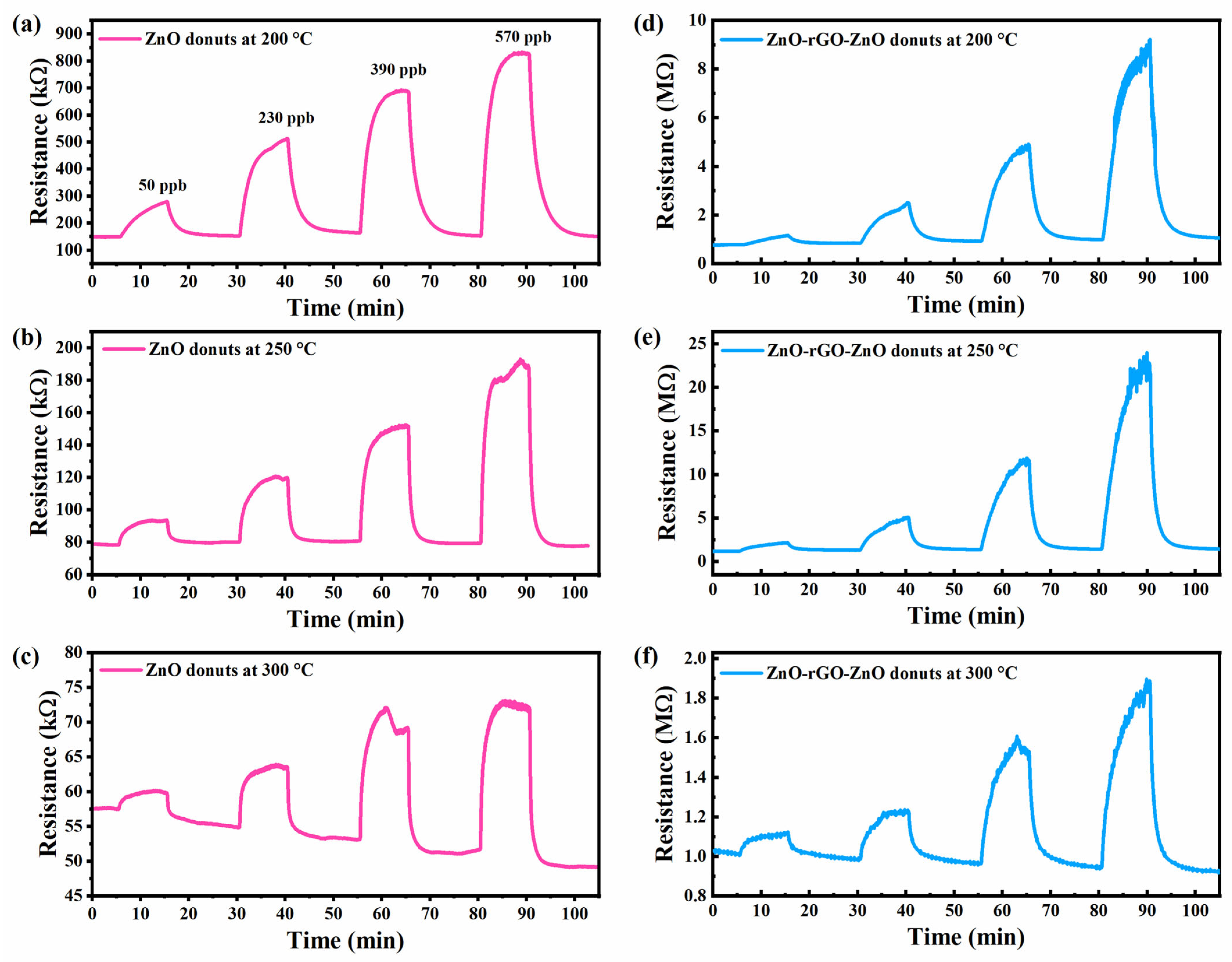

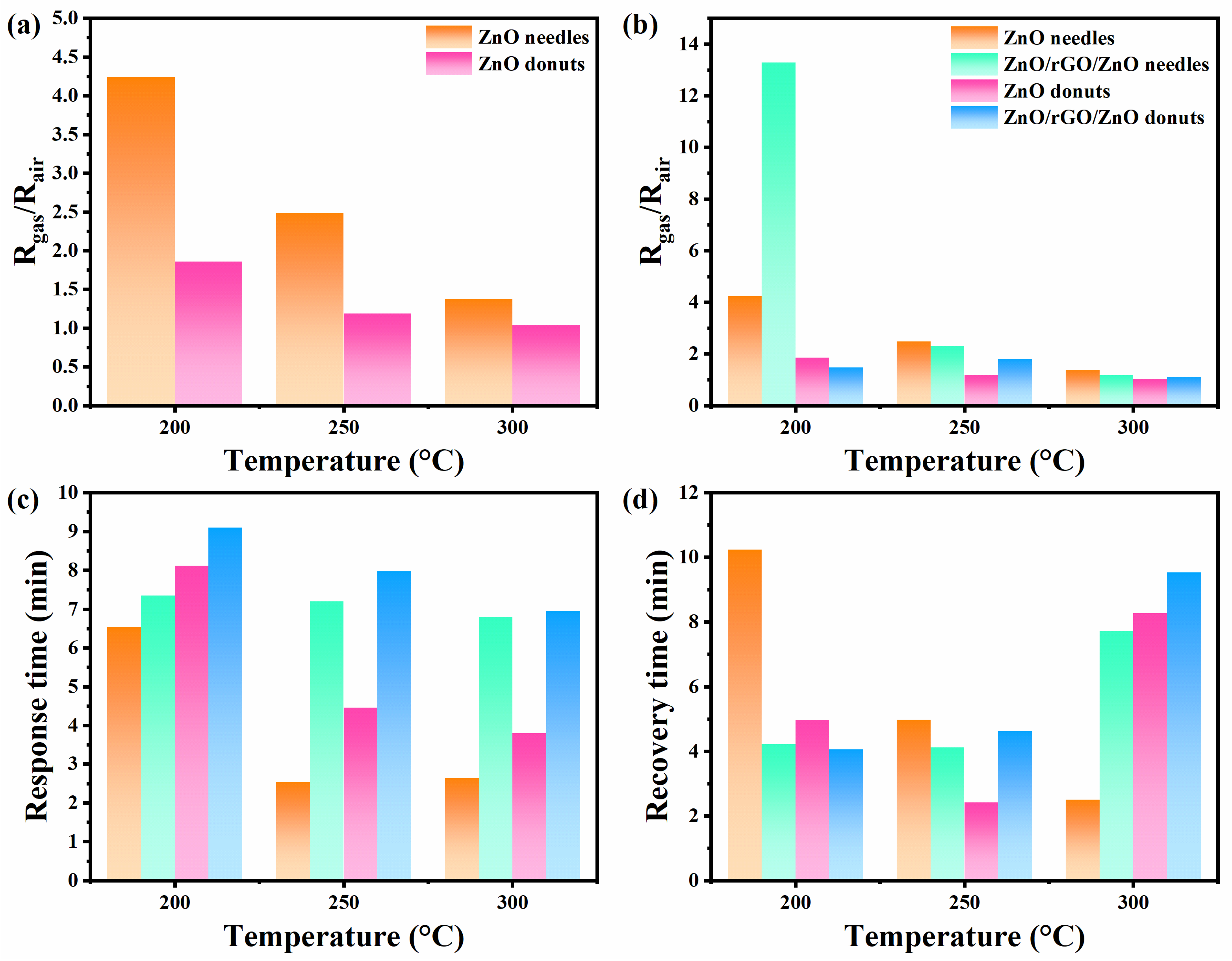

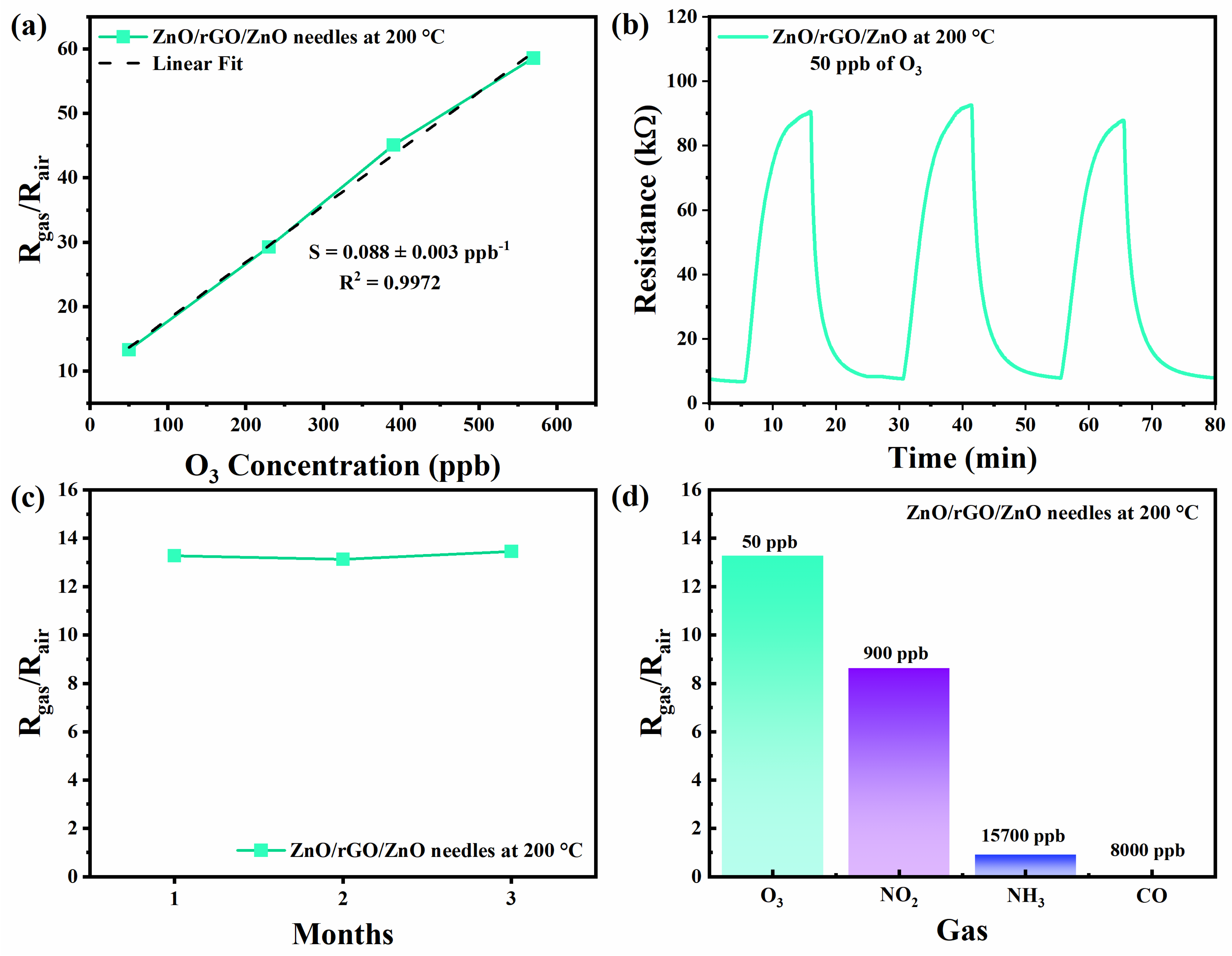

3.5. Gas Sensors

3.6. Gas Sensing Mechanisms

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ying, S.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Z.; Huang, M.; Dong, L.; Zhao, J.; Peng, C. Highly-Sensitive NO2 Gas Sensors Based on Three-Dimensional Nanotube Graphene and ZnO Nanospheres Nanocomposite at Room Temperature. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 566, 150720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakosta, E.S.; Karabagias, I.K.; Riganakos, K.A. Shelf Life Extension of Greenhouse Tomatoes Using Ozonation in Combination with Packaging under Refrigeration. Ozone Sci. Eng. 2019, 41, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandiselvam, R.; Subhashini, S.; Banuu Priya, E.P.; Kothakota, A.; Ramesh, S.V.; Shahir, S. Ozone Based Food Preservation: A Promising Green Technology for Enhanced Food Safety. Ozone Sci. Eng. 2019, 41, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onofre, Y.J.; Catto, A.C.; Bernardini, S.; Fiorido, T.; Aguir, K.; Longo, E.; Mastelaro, V.R.; da Silva, L.F.; de Godoy, M.P.F. Highly Selective Ozone Gas Sensor Based on Nanocrystalline Zn0.95 Co0.05O Thin Film Obtained via Spray Pyrolysis Technique. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 478, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, P.P.; Palma, J.V.N.; Doimo, A.L.; Líbero, L.; Yamakawa, G.F.; Merízio, L.G.; Aguiar, E.C.; Silva, L.F.; Longo, E. Influence of Different Synthesis Methods on the Defect Structure, Morphology, and UV-Assisted Ozone Sensing Properties of Zinc Oxide Nanoplates. Chemosensors 2025, 13, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos Silva, W.A.; de Lima, B.S.; Bernardi, M.I.B.; Mastelaro, V.R. Enhancement of the Ozone-Sensing Properties of ZnO through Chemical-Etched Surface Texturing. J. Nanoparticle Res. 2022, 24, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paralikis, A.; Gagaoudakis, E.; Kampitakis, V.; Aperathitis, E.; Kiriakidis, G.; Binas, V. Study on the Ozone Gas Sensing Properties of Rf-Sputtered Al-Doped NiO Films. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belaqziz, M.; Amjoud, M.; Gaddari, A.; Rhouta, B.; Mezzane, D. Enhanced Room Temperature Ozone Response of SnO2 Thin Film Sensor. Superlattices Microstruct. 2014, 71, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Palma, J.V.N.; Catto, A.C.; de Oliveira, M.C.; Ribeiro, R.A.P.; Teodoro, M.D.; da Silva, L.F. Light-Assisted Ozone Gas-Sensing Performance of SnO2 Nanoparticles: Experimental and Theoretical Insights. Sens. Actuators Rep. 2022, 4, 100081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguir, K.; Lemire, C.; Lollman, D.B. Electrical Properties of Reactively Sputtered WO3 Thin Films as Ozone Gas Sensor. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2002, 84, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Xie, M.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y. Fabrication of WO3 Nanosheets with Hexagonal/Orthorhombic Homojunctions for Highly Sensitive Ozone Gas Sensors at Low Temperature. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1010, 178228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resende Leite, R.; Komorizono, A.A.; Basso Bernardi, M.I.; Carvalho, A.J.F.; Mastelaro, V.R. Environmentally Friendly Synthesis of In2O3 Nano Octahedrons by Cellulose Nanofiber Template-Assisted Route and Their Potential Application for O3 Gas Sensing. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 10192–10202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, N.; Zhang, P.; Zhou, T.; Zhang, T. Selective Ppb-Level Ozone Gas Sensor Based on Hierarchical Branch-like In2O3 Nanostructure. Sens. Actuators B. Chem. 2021, 336, 129612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bejaoui, A.; Guerin, J.; Zapien, J.A.; Aguir, K. Theoretical and Experimental Study of the Response of CuO Gas Sensor under Ozone. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2014, 190, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, L.S.R.; Foschini, C.R.; Silva, C.C.; Longo, E.; Simões, A.Z. Novel Ozone Gas Sensor Based on ZnO Nanostructures Grown by the Microwave-Assisted Hydrothermal Route. Ceram. Int. 2016, 42, 4539–4545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A.; Jeyaprakash, B.G. Selective Detection of Ammonia by RGO Decorated Nanostructured ZnO for Poultry and Farm Field Applications. Synth. Met. 2022, 290, 117140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, M.A.; Conti, P.P.; Andre, R.S.; Correa, D.S. A Review on Chemiresistive ZnO Gas Sensors. Sens. Actuators Rep. 2022, 4, 100100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Qiao, G.; Chen, X.; Wang, X.; Cui, H. Synthesis of ZnO Hollow Microspheres and Analysis of Their Gas Sensing Properties for N-Butanol. Crystals 2020, 10, 1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero-Muñoz, M.; Ramos-Ibarra, J.E.; Rodríguez-Páez, J.E.; Marques, G.E.; Teodoro, M.D.; Coaquira, J.A.H. Growth and Formation Mechanism of Shape-Selective Preparation of ZnO Structures: Correlation of Structural, Vibrational and Optical Properties. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2020, 22, 7329–7339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolli, E.; Fornari, A.; Bellucci, A.; Mastellone, M.; Valentini, V.; Mezzi, A.; Polini, R.; Santagata, A.; Trucchi, D.M. Room-Temperature O3 Detection: Zero-Bias Sensors Based on ZnO Thin Films. Crystals 2024, 14, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Ravikant, C.; Kaur, A. Facile Synthesis of Nitrogen-Doped Reduced Graphene Oxide/Zinc Oxide Nanocomposites for Enhanced Room-Temperature Ammonia Gas Detection. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2024, 35, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, A.; Samanta, S.; Bhangare, B.; Rajan, S.K.; Bahadur, J.; Ramgir, N.S.; Kaur, M.; Singh, A.; Debnath, A.K. Nanocomposites of ZnO Nanostructures and Reduced Graphene Oxide Nanosheets for NO2 Gas Sensing. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2023, 6, 7649–7657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Lu, J.; Zhang, X.; Peng, X.; Li, J.; Yang, Y.; Hong, B.; Wang, X.; Jin, D.; Jin, H. Reversible Switching from P- to N-Type NO2 Sensing in ZnO Rods/RGO by Changing the NO2 Concentration, Temperature, and Doping Ratio. J. Phys. Chem. C 2022, 126, 14470–14478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budhiraja, N.; Sapna; Kumar, V.; Tomar, M.; Gupta, V.; Singh, S.K. Facile Synthesis of Porous CuO Nanosheets as High-Performance NO2 Gas Sensor. Integr. Ferroelectr. 2018, 193, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Guo, H.; Zhang, F.; Li, X.; Yu, J.; Chen, X. Porous ZnO/RGO Nanosheet-Based NO2 Gas Sensor with High Sensitivity and Ppb-Level Detection Limit at Room Temperature. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 8, 2101511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.; Peng, C.; Fu, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, Z.; Xu, S.; Cui, S. High Surface Area ZnO/RGO Aerogel for Sensitive and Selective NO2 Detection at Room Temperature. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 908, 164567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Bian, H.; Guo, M.; Tao, Z.; Luo, X.; Cui, Y.; Huang, J.; Tu, P. Low Temperature and High Sensitivity H2S Gas Sensor Based on Ag/RGO/ZnO Ternary Composite Material. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2025, 180, 114946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundaramoorthy, A.; Vivekananthan, V.; Hajra, S.; Panda, S.; Kim, H.J.; Nagarajan, N. A Flexible Nanocomposite Film Based on PVDF/ZnO-RGO for Energy Harvesting and Self-Powered Carbon Dioxide Gas Sensing. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2025, 32, 24325–24335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayachandiran, J.; Raja, A.; Arivanandhan, M.; Jayavel, R.; Nedumaran, D. A Facile Synthesis of Hybrid Nanocomposites of Reduced Graphene Oxide/ZnO and Its Surface Modification Characteristics for Ozone Sensing. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2018, 29, 3074–3086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lima, B.S.; Komorizono, A.A.; Silva, W.A.S.; Ndiaye, A.L.; Brunet, J.; Bernardi, M.I.B.; Mastelaro, V.R. Ozone Detection in the Ppt-Level with RGO-ZnO Based Sensor. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2021, 338, 129779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komorizono, A.A.; de Lima, B.S.; Mastelaro, V.R. Assessment of the Ozonolysis Effect of RGO-ZnO-Based Ozone Sensors. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2023, 397, 134621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groveman, S.; Peng, J.; Itin, B.; Diallo, I.; Pratt, L.M.; Greer, A.; Biddinger, E.J.; Greenbaum, S.G.; Drain, C.M.; Francesconi, L.; et al. The Role of Ozone in the Formation and Structural Evolution of Graphene Oxide Obtained from Nanographite. Carbon 2017, 122, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagliaferro, J.C.; Komorizono, A.A.; Pessoa, N.C.S.; Correia, R.S.; Bernardi, M.I.B.; Mastelaro, V.R. Influence of Morphology and Heterostructure Formation on the NO2 Gas Sensing Properties of the ZnO-NiO System. Talanta Open 2024, 10, 100388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, P.; Cai, Y.; Pawar, D.; Navale, S.T.; Rao, C.N.; Han, S.; Lu, Y. Down to Ppb Level NO2 Detection by ZnO/RGO Heterojunction Based Chemiresistive Sensors. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 401, 125491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stobinski, L.; Lesiak, B.; Malolepszy, A.; Mazurkiewicz, M.; Mierzwa, B.; Zemek, J.; Jiricek, P.; Bieloshapka, I. Graphene Oxide and Reduced Graphene Oxide Studied by the XRD, TEM and Electron Spectroscopy Methods. J. Electron Spectros. Relat. Phenomena 2014, 195, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beams, R.; Gustavo Cançado, L.; Novotny, L. Raman Characterization of Defects and Dopants in Graphene. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2015, 27, 083002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimenta, M.A.; Dresselhaus, G.; Dresselhaus, M.S.; Cançado, L.G.; Jorio, A.; Saito, R. Studying Disorder in Graphite-Based Systems by Raman Spectroscopy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2007, 9, 1276–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudin, K.N.; Ozbas, B.; Schniepp, H.C.; Prud’homme, R.K.; Aksay, I.A.; Car, R. Raman Spectra of Graphite Oxide and Functionalized Graphene Sheets. Nano Lett. 2008, 8, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, A.C. Raman Spectroscopy of Graphene and Graphite: Disorder, Electron-Phonon Coupling, Doping and Nonadiabatic Effects. Solid State Commun. 2007, 143, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Díaz, D.; Delgado-Notario, J.A.; Clericò, V.; Diez, E.; Merchán, M.D.; Velázquez, M.M. Towards Understanding the Raman Spectrum of Graphene Oxide: The Effect of the Chemical Composition. Coatings 2020, 10, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caņado, L.G.; Takai, K.; Enoki, T.; Endo, M.; Kim, Y.A.; Mizusaki, H.; Jorio, A.; Coelho, L.N.; Magalhães-Paniago, R.; Pimenta, M.A. General Equation for the Determination of the Crystallite Size La of Nanographite by Raman Spectroscopy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2006, 88, 163106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arul, R.; Oosterbeek, R.N.; Robertson, J.; Xu, G.; Jin, J.; Simpson, M.C. The Mechanism of Direct Laser Writing of Graphene Features into Graphene Oxide Films Involves Photoreduction and Thermally Assisted Structural Rearrangement. Carbon 2016, 99, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrabet, S.; Ihzaz, N.; Bessadok, M.N.; Vázquez-Vázquez, C.; Alshammari, M.; El Mir, L. Microstructural, Raman, and Magnetic Investigations on Ca-Doped ZnO Nanoparticles. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2024, 34, 2064–2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achehboune, M.; Khenfouch, M.; Boukhoubza, I.; Leontie, L.; Doroftei, C.; Carlescu, A.; Bulai, G.; Mothudi, B.; Zorkani, I.; Jorio, A. Microstructural, FTIR and Raman Spectroscopic Study of Rare Earth Doped ZnO Nanostructures. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 53, 319–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Srivastava, A.K.; Patel, H.S.; Gupta, B.K.; Varma, G. Das Facile Synthesis of ZnO-Reduced Graphene Oxide Nanocomposites for NO2 Gas Sensing Applications. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2015, 2015, 1912–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saikia, L.; Bhuyan, D.; Saikia, M.; Malakar, B.; Dutta, D.K.; Sengupta, P. Photocatalytic Performance of ZnO Nanomaterials for Self Sensitized Degradation of Malachite Green Dye under Solar Light. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2015, 490, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldeen, T.S.; Ahmed Mohamed, H.E.; Maaza, M. ZnO Nanoparticles Prepared via a Green Synthesis Approach: Physical Properties, Photocatalytic and Antibacterial Activity. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2022, 160, 110313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdolhosseinzadeh, S.; Asgharzadeh, H.; Sadighikia, S.; Khataee, A. UV-Assisted Synthesis of Reduced Graphene Oxide–ZnO Nanorod Composites Immobilized on Zn Foil with Enhanced Photocatalytic Performance. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2016, 42, 4479–4496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jogi, A.; Ayana, A.; Rajendra, B.V. Modulation of Optical and Photoluminescence Properties of ZnO Thin Films by Mg Dopant. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2023, 34, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murlidhar, G.; Kumar, R.; Kharat, P.B.; Khirade, P. Structural, Microstructural and Optical Characteristics of RGO-ZnO Nanocomposites via Hydrothermal Approach. Opt. Mater. 2024, 154, 115720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhter, S.; Lui, K.; Kung, H.H. Comparison of the Chemical Properties of the Zinc-Polar, the Oxygen-Polar, and the Nonpolar Surfaces of ZnO. J. Phys. Chem. 1985, 89, 1958–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, G.; Asif, M.H.; Zainelabdin, A.; Zaman, S.; Nur, O.; Willander, M. Influence of PH, Precursor Concentration, Growth Time, and Temperature on the Morphology of ZnO Nanostructures Grown by the Hydrothermal Method. J. Nanomater. 2011, 2011, 269692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Zhao, M.; Wang, Z.; Ji, H.; Zheng, B.; Xiao, D. The Role of Ozone in the Ozonation Process of Graphene Oxide: Oxidation or Decomposition? RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 58325–58328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadaki, D.; Mhlongo, G.H.; Motaung, D.E.; Nkosi, S.S.; Panagiotaki, K.; Christaki, E.; Assimakopoulos, M.N.; Papadimitriou, V.C.; Rosei, F.; Kiriakidis, G.; et al. Hierarchically Porous Cu-, Co-, and Mn-Doped Platelet-Like ZnO Nanostructures and Their Photocatalytic Performance for Indoor Air Quality Control. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 16429–16440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.; Guler, A.C.; Masar, M.; Antos, J.; Hanulikova, B.; Urbanek, P.; Yasir, M.; Sopik, T.; Machovsky, M.; Kuritka, I. Structural Factors Influencing Photocatalytic and Photoelectrochemical Performance of Low-Dimensional ZnO Nanostructures. Catal. Today 2025, 445, 115088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, J.; Liu, X. Ternary Nanocomposite ZnO-g–C3N4–Go for Enhanced Photocatalytic Degradation of RhB. Opt. Mater. 2021, 119, 111351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, J. The Oxygen Vacancy Defect of ZnO/NiO Nanomaterials Improves Photocatalytic Performance and Ammonia Sensing Performance. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Platonov, V.; Malinin, N.; Vasiliev, R.; Rumyantseva, M. Room Temperature UV-Activated NO2 and NO Detection by ZnO/RGO Composites. Chemosensors 2023, 11, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Myung, N.V.; Tran, T.T. 1D Metal Oxide Semiconductor Materials for Chemiresistive Gas Sensors: A Review. Adv. Electron. Mater. 2021, 7, 2100271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Li, D.; Chen, X.; Peng, X.; Li, J.; Yang, Y.; Hong, B.; Wang, X.; Jin, D.; Jin, H. ZnO/Reduced Graphene Oxide Nanocomposite with Synergic Enhanced Gas Sensing Performance for the Effective Detection of NO2 at Room Temperature. J. Nanoparticle Res. 2022, 24, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sett, A.; Majumder, S.; Bhattacharyya, T.K. Flexible Room Temperature Ammonia Gas Sensor Based on Low-Temperature Tuning of Functional Groups in Grapheme. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2021, 68, 3181–3188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariyoshi, K.; Tanimoto, M.; Yamada, Y. Electrochimica Acta Impact of Particle Size of Lithium Manganese Oxide on Charge Transfer Resistance and Contact Resistance Evaluated by Electrochemical Impedance Analysis. Electrochim. Acta 2020, 364, 137292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishna, G.; Ghosh, H.N. Effect of Particle Size on the Reactivity of Quantum Size ZnO Nanoparticles and Charge-Transfer Dynamics with Adsorbed Catechols. Langmuir 2003, 19, 3006–3012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Dai, M.; Li, Y.; Bai, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, C.; Liu, F.; Lu, G. The Influence of Different ZnO Nanostructures on NO2 Sensing Performance. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2021, 329, 129145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.S.; Chen, F.K.; Tsai, D.C.; Kuo, B.H.; Shieu, F.S. N-Doped Reduced Graphene Oxide for Room-Temperature NO Gas Sensors. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 20719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modak, M.; Jagtap, S. Low Temperature Operated Highly Sensitive, Selective and Stable NO2 Gas Sensors Using N-Doped SnO2-RGO Nanohybrids. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 19978–19989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, L.T.; Hsueh, H.T.; Chiu, C.H.; Cheng, T.C.; Chang, S.J. Thermal Oxidation CuO Nanowire Gas Sensor for Ozone Detection Applications. Sens. Actuators Rep. 2024, 8, 100228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catto, A.C.; Bernardini, S.; Aguir, K.; Longo, E.; da Silva, L.F. In-Situ Hydrothermal Synthesis of Oriented Hematite Nanorods for Sub-Ppm Level Detection of Ozone Gas. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 947, 169444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagarjuna, Y.; Hsiao, Y.J.; Wang, S.C.; Shao, C.Y.; Huang, Y.C. Nanoporous ZnO Structure Prepared by HiPIMS Sputtering for Enhanced Ozone Gas Detection. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 35, 106024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, N.; Zhang, P.; Cao, S.; Zhou, T.; Zhang, T. Nanosheet-Assembled In2O3 for Sensitive and Selective Ozone Detection at Low Temperature. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 888, 161430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souissi, R.; Bouguila, N.; Bendahan, M.; Aguir, K.; Fiorido, T.; Abderrabba, M.; Halidou, I.; Labidi, A. Ozone Sensing Study of Sprayed β-In2S3 Thin Films. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 900, 163513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khomarloo, N.; Mohsenzadeh, E.; Bagherzadeh, R.; Latifi, M.; Debliquy, M.; Ly, A.; Lahem, D.; Gidik, H. Fabrication of Gas Sensors for Detecting NO and NO2 by Synthesizing RGO/ZnO Nanofibers. J. Text. Inst. 2025, 116, 3172–3182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | ID/IG | I2D/IG | La |

|---|---|---|---|

| rGO | 1.84 | 0.15 | 9.12 |

| ZnO-rGO-ZnO needles | 1.72 | 0.21 | 9.75 |

| ZnO-rGO-ZnO donuts | 1.59 | 0.17 | 10.56 |

| Samples | C 1s (% at) | O 1s (% at) | Zn 2p (% at) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ZnO needle-like | 43.29 | 45.42 | 11.29 |

| ZnO donut-like | 53.40 | 27.20 | 19.40 |

| ZnO-rGO-ZnO needles | 57.91 | 35.00 | 7.09 |

| ZnO-rGO-ZnO donuts | 56.63 | 38.09 | 5.28 |

| Components | ZnO Donuts (% at) | ZnO/rGO/ZnO Donuts (% at) | ZnO Needles (% at) | ZnO/rGO/ZnO Needles (% at) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OI | 53.40 | 44.51 | 60.79 | 54.56 |

| OII | 27.22 | 45.02 | 27.64 | 32.09 |

| OIII | 19.38 | 10.47 | 11.57 | 13.35 |

| Sensing Materials | Concentration (ppb) | T (°C) | Response | Response/Recovery Time | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZnO/rGO/ZnO needles | 50 | 200 °C | 13.3 a | 442/253 | This work |

| rGO-ZnO | 100 | 300 °C | 49.6 a | - | [30] |

| ZnO-rGO-ZnO | 135 | 250 °C | ~37 a | 498/360 | [31] |

| CuO NWs | 50 | 100 °C | 40% b | - | [67] |

| In2O3 | 200 | 70 °C | 5 a | - | [13] |

| A-Fe2O3 | 10 | 150 °C | ~3.5 a | - | [68] |

| ZnO nanoporous | 200 | 200 °C | 216% b | 300/600 | [69] |

| In2O3-12 | 100 | 80 °C | 16.7 a | 707/422 | [70] |

| β-In2O3 | 40 | 160 °C | 1.5 a | 147/414 | [71] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Correia, R.S.; Komorizono, A.A.; Tagliaferro, J.C.; Pessoa, N.C.S.; Mastelaro, V.R. ZnO/rGO/ZnO Composites with Synergic Enhanced Gas Sensing Performance for O3 Detection with No Ozonolysis Process. Chemosensors 2026, 14, 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors14010010

Correia RS, Komorizono AA, Tagliaferro JC, Pessoa NCS, Mastelaro VR. ZnO/rGO/ZnO Composites with Synergic Enhanced Gas Sensing Performance for O3 Detection with No Ozonolysis Process. Chemosensors. 2026; 14(1):10. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors14010010

Chicago/Turabian StyleCorreia, Rayssa Silva, Amanda Akemy Komorizono, Julia Coelho Tagliaferro, Natalia Candiani Simões Pessoa, and Valmor Roberto Mastelaro. 2026. "ZnO/rGO/ZnO Composites with Synergic Enhanced Gas Sensing Performance for O3 Detection with No Ozonolysis Process" Chemosensors 14, no. 1: 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors14010010

APA StyleCorreia, R. S., Komorizono, A. A., Tagliaferro, J. C., Pessoa, N. C. S., & Mastelaro, V. R. (2026). ZnO/rGO/ZnO Composites with Synergic Enhanced Gas Sensing Performance for O3 Detection with No Ozonolysis Process. Chemosensors, 14(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors14010010