1. Introduction

Energy transfer mechanisms are fundamental to a vast array of biological and chemical processes. They provide critical insights into the molecular principles that govern signal transduction, biomolecular recognition, and diagnostic sensing [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Among these, resonance energy transfer (RET) techniques have emerged as powerful tools for probing biomolecular interactions at the nanometric scale, particularly in biosensing and medical diagnostics. The integration of nanotechnology with photophysics has accelerated the development of sophisticated RET-based sensors, which leverage the interactions between fluorophores and metallic nanostructures to achieve highly sensitive detection of biologically relevant targets.

Traditionally, Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) has been the most widely utilized RET mechanism [

5]. FRET operates through a non-radiative dipole–dipole coupling process, wherein an excited donor fluorophore transfers energy to a proximal acceptor fluorophore, typically within a distance range of 1–10 nm [

6]. This process requires both significant spectral overlap and a favorable dipole orientation. Despite its extensive application, FRET is constrained by its steep R

−6 distance dependence, resulting in diminished sensitivity beyond 10 nm. This limitation restricts its utility in investigating larger biomolecular assemblies or long-range conformational dynamics [

1,

5].

To address the inherent limitations of FRET, nanometal surface energy transfer (NSET) has been developed as a robust alternative. NSET describes the non-radiative energy transfer from a point dipole donor to a planar or spherical metal nanoparticle acceptor [

7,

8,

9]. Unlike FRET, which models the donor and acceptor as point dipoles, NSET treats the acceptor as a nanometal surface. This results in a more gradual R

−4 distance dependence, permitting efficient energy transfers over considerably longer distances—up to approximately 30–40 nm [

10]. Furthermore, NSET is not subject to the stringent orientation-factor constraints of FRET and benefits from the unique electromagnetic properties of metal nanoparticles, such as gold and silver. The localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) of these nanoparticles enables exceptionally efficient energy absorption and quenching.

The Surface Energy Transfer (SET) model was introduced as a refinement of the classical NSET theory to more accurately describe energy transfer efficiency at the nanoscale. While NSET models energy transfer between a dipole donor (such as a fluorescent dye or quantum dot) and an idealized infinite metal surface or large nanoparticle, the SET model incorporates the finite size of the metal nanoparticle, particularly for sizes in the range of 2–20 nm, where surface-to-volume effects significantly influence optical behavior. Importantly, reports have shown that SET efficiency is not only dependent on the donor-acceptor distance but also on the diameter, composition, and optical properties of the nanoparticle, as well as the emission wavelength of the donor [

7,

8,

9]. Smaller nanoparticles exhibit reduced quenching efficiency, while larger particles tend toward the classical behavior described by NSET [

4]. This model has been both theoretically and experimentally validated, especially in fluorescence quenching studies involving gold nanoparticles (AuNPs), providing a crucial theoretical framework for designing and optimizing nanomaterial-based biosensors [

4,

7,

8,

9].

NSET-based platforms have demonstrated exceptional utility in biosensing. These quenching platforms have been used to detect nucleic acids, proteins, small molecules, and whole cells with high sensitivity and selectivity. Such systems often involve conjugating a fluorophore-labeled probe to a target analyte, bringing the donor in proximity to a metal nanoparticle upon binding, and resulting in quantifiable fluorescence quenching. Applications include detecting DNA hybridization, aptamer–target binding, and antigen–antibody interactions using NSET-based strategies [

1,

4,

11].

Over the years, organic dyes have served as the primary fluorophores for energy transfer-based biosensing systems. Their widespread use in fluorescence spectroscopy and imaging is attributed to their ease of functionalization and predictable spectral characteristics [

4,

8]. However, organic dyes face several limitations, including low photostability, narrow absorption spectra, limited quantum yields, and susceptibility to photobleaching under prolonged excitation. These drawbacks significantly compromise their suitability for long-term, high-resolution multiplexed biosensing and bioimaging applications [

1].

To overcome these limitations, advances in nanotechnology have enabled the development of nanomaterial-based fluorophores with superior optical properties, tunable emission profiles, and greater stability. Semiconductor quantum dots (QDs) were among the first nanoscale alternatives. Unlike organic dyes, QDs can be excited by a single light source and emit over a broad wavelength range determined by their size and composition. This facilitates the multiplexed detection of multiple targets in a single assay—a significant advantage for diagnostic applications [

1,

12]. The core–shell structures of QDs also confer enhanced photostability and resistance to quenching.

In parallel, metal nanoclusters (MNCs), particularly Au and Ag NCs, have emerged as fluorophores with discrete electronic states, ultra-small sizes, and long fluorescence lifetimes. These properties allow them to behave like molecular fluorophores while providing superior photostability and biocompatibility [

13,

14]. NCs can be engineered to emit in the visible to near-infrared range, making them valuable for in vivo imaging and deep tissue biosensing. Additionally, carbon-based nanomaterials such as carbon dots (CDs) and graphene quantum dots (GQDs) further diversify the fluorophore landscape. CDs are particularly notable for their water solubility, low toxicity, and excitation-dependent emissions. Their cost-effective synthesis, surface modifiability, and resistance to photobleaching make them attractive candidates for biosensing applications [

15,

16]. When employed as donors in NSET systems, CDs exhibit strong fluorescence quenching in the presence of metal nanoparticles, aligning well with theoretical predictions and demonstrating their potential for scalable diagnostic platforms.

Collectively, these innovations mark a definitive transition in biosensor design from dye-based platforms to robust nanomaterial-based platforms with superior photophysical properties. This evolution has improved biosensor performance and expanded their performance scope to new domains, including super-resolution imaging, wearable diagnostics, photodynamic therapy, and environmental monitoring. NSET represents a superior alternative to FRET, particularly for applications requiring longer donor–acceptor distances, broader spectral compatibility, and heightened sensitivity. The synergy among nanotechnology, optical physics, and molecular biology within NSET-based platforms holds immense promise for next-generation biosensors and biomedical technologies.

This review explores the theoretical mechanisms of NSET, classifies various NSET platforms, details their biomedical applications, and examines emerging technologies that integrate NSET into advanced diagnostic systems (

Scheme 1).

4. Analytical Applications of NSET

NSET has emerged as a central technique in the evolution of biosensing platforms, particularly for biomedical diagnostic and therapeutic applications. Its superior distance sensitivity, tunability via nanoparticle size, and compatibility with a broad spectrum of nanomaterials and biomolecular probes establish NSET as an essential tool in nanobiotechnology. This section outlines the core biomedical applications of NSET, including nucleic acid detection, protein analysis, metal ion sensing, small-molecule and biomolecule identification, pathogen detection, disease diagnostics, and imaging technologies.

4.1. Nucleic Acid Detection

The precise detection of nucleic acids—such as DNA, RNA, and microRNAs (miRNAs)—is vital for disease diagnostics, genetic analysis, and biomedical research. NSET has recently gained recognition as a powerful biosensing mechanism, offering a longer operational range (up to approximately 30–40 nm) compared to conventional FRET, enhanced QE, and tunable properties based on nanoparticle size. The detection process in NSET-based assays is fundamentally dependent on the distance-dependent quenching of donor fluorescence in the presence of an acceptor. This has enabled widespread application of NSET in the detection of various forms of nucleic acids, spanning diagnostic assays to nucleic acid structural investigations.

For instance, a dual-channel biosensor was developed using CDs in combination with AuNPs for the simultaneous detection of

BRCA1 and

TK1 RNA/DNA sequences. In this system, a hairpin DNA structure modulates CD fluorescence via NSET-mediated quenching. If target sequences are absent, the CDs remain quenched; however, the presence of complementary sequences causes a conformational change, releasing fluorescent moieties and restoring the signal. The biosensor achieves detection limits of 1.5 nM and 2.1 nM for

BRCA1 RNA/DNA and 3.6 nM and 4.5 nM for

TK1 RNA/DNA, within their respective linear ranges [

32]. The design’s flexibility enables the detection of other gene sequences or aptamer complexes simply by modifying the DNA programming, demonstrating its adaptability as a diagnostic tool.

To address concerns regarding toxicity in QD-based systems, a novel electrochemiluminescence (ECL) RET platform was engineered using graphitic carbon nitride quantum dots (g-CNQDs) and AuNPs. In this system, hairpin DNA conjugated to AuNPs serves as a quencher, suppressing the ECL signal from the g-CNQDs. Upon hybridization with target DNA, the hairpin unfolds, spatially separating the quencher from the donor and restoring the ECL signal [

15]. This platform demonstrates an ultralow detection limit of 0.01 fM and a broad detection range from 0.02 fM to 0.1 pM, providing a highly sensitive and environmentally friendly alternative for nucleic acid detection.

Further advancements in NSET sensor design have been achieved by introducing 6-mercaptohexanol (MCH) to improve the signal-to-background ratio in AuNP–QD-based sensors. MCH stretches DNA adsorbed on the AuNP surface, modulating energy transfer efficiency and yielding more pronounced fluorescence recovery upon target recognition. The modified sensor covers a broad detection range (5–120 nM) and achieves a detection limit of 1.19 nM for nucleic acids [

33]. This sensing architecture has also been successfully adapted for detecting the cancer biomarker

MUC1, highlighting its versatility for genetic and protein-based diagnostics (

Figure 2A).

Another innovative, eco-friendly fluorescence-based method combines NSET with iodide-induced etching. In this technique, DNA strands labeled with a fluorescent FAM dye are conjugated to AuNPs, resulting in fluorescence quenching due to NSET between the fluorophore and gold core. The addition of a high concentration of iodide ions (6 M I

−) etches the AuNPs, releasing DNA–FAM into solution and restoring fluorescence [

34].

The recovered signal is directly correlated with the number of DNA molecules initially bound to the nanoparticle surface, enabling one-step quantification without harsh reagents or complex instrumentation (

Figure 2B). This iodide etching approach not only streamlines DNA quantification but also has broader applicability for assessing other biomolecules conjugated to AuNPs. Incorporating NSET into this strategy demonstrates its value in advancing nanoparticle-based detection systems and enhancing biosensor calibration in terms of sensitivity and safety.

Hu et al. utilized the high quenching efficiency of core–shell Au@polydopamine nanocomposites to develop robust fluorescent nanoprobes for intracellular mRNA imaging [

35]. Through synergistic NSET and photoinduced electron transfer (PET) interactions, fluorescence quenching efficiencies exceeding 92% were achieved, enabling sensitive detection of tumor-related mRNAs. This platform exhibited excellent analytical performance, with detection limits as low as 0.43 nM and broad linear ranges (1.8–90 nM), while also supporting multiplexed mRNA detection in living cells (

Figure 2C). Similarly, Zou et al. developed polydopamine-embedded Cu

2-xSe nanoparticles (Cu

2−xSeNPs@pDA) coupled with dye-labeled DNA exhibited strong fluorescence quenching arising from the synergistic coupling of NSET and PET [

36]. Steady-state and time-resolved fluorescence measurements, supported by kinetic modeling, revealed that NSET dominates the quenching process, while PET provides an additional nonradiative decay pathway. Upon target binding, weakened interactions between the dye-labeled probes and nanoparticles led to fluorescence recovery, enabling DNA detection with a limit of detection (LOD) of ~0.5 nM (

Figure 2D).

NSET-based probes offer significant analytical advantages in nucleic acid sensing, including low detection limits, high selectivity, and excellent reproducibility. Despite these advancements, challenges remain, including the need to further improve signal-to-background ratios, enable absolute quantification without calibration, and integrate these sensitive systems into robust, user-friendly POCT devices.

Table 2 summarizes NSET-based probes for nucleic acid detection.

4.2. Protein Detection

Protein biomarkers are critical for clinical diagnostics and therapeutic monitoring, necessitating detection methods that are both sensitive and selective. NSET-based biosensors have emerged as robust platforms for this purpose, utilizing the energy transfer between fluorophores and nanometal surfaces to achieve high sensitivity and specificity. Continuous advancements in NSET have markedly enhanced the sensitivity and accuracy of protein biosensing, enabling early-stage diagnostics in complex biological systems.

For instance, Diriwari et al. integrated the terbium-based complex (CoraFluor-1) into NSET assays for quantifying protein–ligand interactions, specifically demonstrated with the streptavidin–biotin model. By bioconjugating CRF-1 to streptavidin and pairing it with biotin-functionalized nanoparticles, researchers have established nanoscale proximity between the donor (terbium) and acceptors such as AuNPs or QDs. This design enables dual-mode energy transfer: either terbium-to-AuNP NSET or terbium-to-QD FRET, resulting in high QE and a broad dynamic detection range [

39]. The unique photophysical properties of CRF-1, including its long emission lifetime and stable luminescence, ensure reliable signal transduction across various fluorescence plate reader platforms (

Figure 3A). Quantitative data show that this system can sensitively detect protein–ligand interactions at low to subpicomolar concentrations, highlighting its potential for diagnostic bioassays and real-time biomolecular sensing. Furthermore, this assay design demonstrates the adaptability of NSET platforms to accommodate various donor–acceptor pairs for robust protein detection.

In a recent study, PEG-functionalized AuNPs covalently coupled with dye-labeled peptide substrates have been demonstrated as effective NSET-based nanoprobes for monitoring the activity of metalloproteinase-14 (MMP-14) [

40]. In this system, three sets of tetramethylrhodamine (TAMRA)–labeled peptides, two enzyme-specific substrates and one control were immobilized on PEG-coated AuNPs. The strong spectral overlap between TAMRA emission and AuNP absorption enabled efficient NSET, resulting in pronounced fluorescence quenching of up to ~85%. Proteolytic cleavage of the surface-tethered peptides by MMP-14 disrupted NSET interactions, producing up to a fourfold fluorescence recovery and allowing real-time optical tracking of enzymatic activity. Systematic concentration- and time-dependent photoluminescence recovery measurements in the presence of MMP-14 revealed good sensitivity, with detection limits in the sub-nanomolar range (0.05–1.60 nM) (

Figure 3B). Another significant development was introduced by Kalkal et al., who designed a biosensing platform for the ultrasensitive quantification of carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), a critical oncological biomarker. In this system, GQDs functionalized with anti-CEA antibodies serve as donor probes, while a hybrid quencher comprising AuNPs conjugated with reduced graphene oxide (AuNPs@rGO) acts as a dual acceptor. This configuration exploits the synergistic quenching capabilities and large surface area of the nanocomposite, achieving a high QE of approximately 88% [

41]. The sensing mechanism relies on the competitive displacement of GQD–antibody conjugates from the quencher surface upon CEA binding, leading to concentration-dependent fluorescence recovery. This assay demonstrates a detection range from 1 pg/mL to 500 ng/mL and a detection limit of 0.35 pg/mL, underscoring the efficacy of the hybrid acceptor design in augmenting NSET-based biosensor performance.

Additionally, an ECL-based NSET sensor has been developed for detecting procalcitonin (PCT), using ferritin as a scaffold to conjugate both luminophores and AuNP acceptors. In this approach, ABEI-functionalized ferritin emits strong ECL in the presence of hydrogen peroxide (H

2O

2), which is efficiently quenched by proximal AuNPs via NSET [

42]. To ensure a consistent antibody orientation and enhance antigen capture, a heptapeptide (HWRGWVC) is incorporated for direct immobilization via specific Fc binding. This biosensor achieves a dynamic detection range of 100–50 ng/mL with a low detection limit of 41 fg/mL. It demonstrates high specificity and reproducibility, highlighting its potential for ultrasensitive protein diagnostics and exemplifying the advantages of combining oriented antibody conjugation with nanometal-based quenching platforms.

Table 3 provides a summary of the NSET-based probes used for protein detection.

4.3. Biomolecule Detection

Accurate and highly sensitive detection of biologically significant molecules, including glutathione, dopamine, spermine, sialic acid, and mycotoxins, is vital for effective biomedical diagnostics. NSET-based fluorescence assays have emerged as powerful tools in this field, offering enhanced quenching ranges and reliable performance within complex biological matrices.

For instance, an NSET system was developed that combines copper nanoparticles (CuNPs) with 2D molybdenum disulfide (MoS

2) nanosheets for detecting glutathione, a tripeptide with a central role in cellular redox homeostasis [

31]. In this system, MoS

2 serves as the fluorescent donor, while CuNPs act as quenchers. Steady-state and time-resolved fluorescence studies have revealed substantial quenching of MoS

2 emissions upon the addition of CuNPs. The fluorescence lifetime measurements support the NSET mechanism, indicated by the observed 1/d

4 distance dependence, distinguishing it from conventional FRET. The sensing principle is based on GSH-mediated chelation and removal of CuNPs from the MoS

2 surface, thereby restoring the fluorescence signal [

31]. This sensor exhibits a robust linear response to GSH concentrations from 10 to 500 nM, with an LOD of 7.4 nM. It also displays high specificity for other thiol-containing and biologically relevant molecules, underscoring its potential applicability in physiological conditions.

For spermine detection—a biogenic polyamine and important biomarker for malignancies—a novel NSET-based biosensor was developed utilizing tetrakis(4-sulfonatophenyl)porphyrin (TPPS

4) as the fluorescent donor and positively charged AuNRs as the acceptor. The assay operates via electrostatic interactions: under acidic conditions, spermine binds strongly to calf thymus DNA (ctDNA), altering the proximity between TPPS

4 and AuNRs. This structural change reinstates the fluorescence previously quenched by NSET. The fluorescence intensity displays a linear correlation with spermine concentrations ranging from 0.5 to 7.5 μM, achieving an LOD of 0.04 μM [

46]. The sensor’s effectiveness was validated in human urine samples, demonstrating its practical utility in clinical diagnostics.

Dopamine (DA), a critical neurotransmitter, has also been targeted using NSET-based sensors. In one design, CDs labeled with DA-specific aptamers serve as both the recognition element and fluorescent reporter, while nitrogen-doped graphene (NG) acts as the nanoquencher due to its extended π-conjugated structure. In the absence of DA, the aptamer–CDs are adsorbed onto the NG surface, leading to fluorescence quenching via NSET. Upon DA binding, the aptamer undergoes a structural rearrangement, detaching from the NG surface and restoring fluorescence. This sensor demonstrates high sensitivity and selectivity for DA, achieving an LOD of 0.055 nM [

47] and has been successfully applied to spiked human serum and urine samples, emphasizing its potential for clinical diagnostics for neurological and psychiatric disorders.

For environmental monitoring, an NSET-based fluorescent sensor was developed for the selective and sensitive detection of trichloroacetic acid (TCAA), a common disinfection byproduct. This system integrates silver nanoprisms (AgNPRs) with europium-based metal–organic frameworks (EuMOFs) synthesized from 5-boronoisophthalic acid, creating a hybrid AgNPR@EuMOF nanostructure via Ag–S bonding. Exposure to TCAA induces a substantial blue shift in the plasmonic absorption of AgNPRs, resulting in fluorescence recovery of the quenched EuMOFs due to NSET disruption [

48]. The sensor achieves a broad linear detection range of 0.1–40 µM and an LOD of 0.033 µM (

Figure 4A). Its performance has been validated in real water samples, such as tap and swimming pool water, demonstrating strong potential for practical environmental monitoring of trace disinfection byproducts.

Mycotoxins, including aflatoxin B1 (AFB1) and T-2 toxin, represent highly toxic secondary metabolites produced by fungi that commonly contaminate food and agricultural products. Even at trace concentrations, these toxins pose significant risks to human and animal health, including immunosuppression, hepatotoxicity, and carcinogenesis, necessitating the development of rapid, highly sensitive detection platforms to ensure food safety and regulatory compliance. In this context, NSET offers a versatile quenching mechanism for various optical biosensors, including ECL, fluorescence, and lateral flow-based formats. For instance, a fluorescence-quenching-based immunochromatographic test strip (FQ-ICTS) for T-2 toxin detection was developed using time-resolved fluorescent microspheres (TRFMs) as energy donors and engineered AuNPs with enhanced plasmonic overlap as acceptors [

49].

By optimizing the donor–acceptor spectral overlap, the QE reached 92.7% with AuNPs optimized at 605 nm. This translated to a highly sensitive test strip with an LOD of 0.034 ng/mL for T-2 toxin, which was over 13-fold more sensitive than conventional colloidal gold test strips (

Figure 4B). The sensor performs robustly in real sample matrices, including maize and wheat, with recovery rates of 95.5–108.7% and strong correlation with reference high-performance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC–MS/MS) methods.

To further improve T-2 toxin detection, NSET was applied in a lateral flow immunoassay (LFIA) format, systematically screening combinations of AuNP acceptors and QDM donors [

50]. Among 27 donor–acceptor configurations, the combination of QDMs emitting at 610 nm and AuNPs absorbing at 605 nm yields optimal spectral overlap and the highest QE (91.0%). This NSET–LFIA sensor achieves a tenfold increase in sensitivity compared to conventional AuNPs–LFIA, with an LOD of 0.04 ng/mL for T-2 toxin. Additionally, an aggregation-induced electrochemiluminescence (AIECL)–NSET platform was developed to detect AFB1, a potent mycotoxin commonly found in foodstuffs [

51]. The system utilizes a metal–organic gel (MOG) matrix synthesized from 1,1,2,2-tetra(4-carboxylphenyl)ethylene (TPE) coordinated with indium ions. This configuration restricts the intramolecular rotation of TPE, facilitating intense photon emission via AIECL. The AuNPs embedded within the triangular DNA structure act as quenchers and are positioned at precise distances from the luminescent donor. NSET-induced quenching, governed by spectral overlap and spatial proximity, efficiently suppresses the ECL signal in the absence of AFB1. Upon analyte introduction, the donor–acceptor configuration is disrupted, restoring the signal proportionally to the analyte concentration. This sensor achieves a wide detection range of 0.50–200 ng/mL and a LOD of 0.17 ng/mL, providing a robust solution for trace-level toxin analysis in food matrices.

Overall, these advances validate NSET-based LFIA as a versatile and scalable approach for ultrasensitive toxin monitoring, particularly in resource-limited settings requiring rapid screening.

Table 4 summarizes the NSET-based probes utilized for the detection of various biomolecules.

4.4. Biomedical Applications of NSET

The advent of NSET technology has revolutionized bioimaging and therapeutic monitoring, providing precise spatial resolution and enabling real-time tracking of molecular events within biological systems. The extended range of NSET and flexibility in designing nanostructures have spurred innovative solutions for optical rulers, apoptosis monitoring, and drug delivery systems.

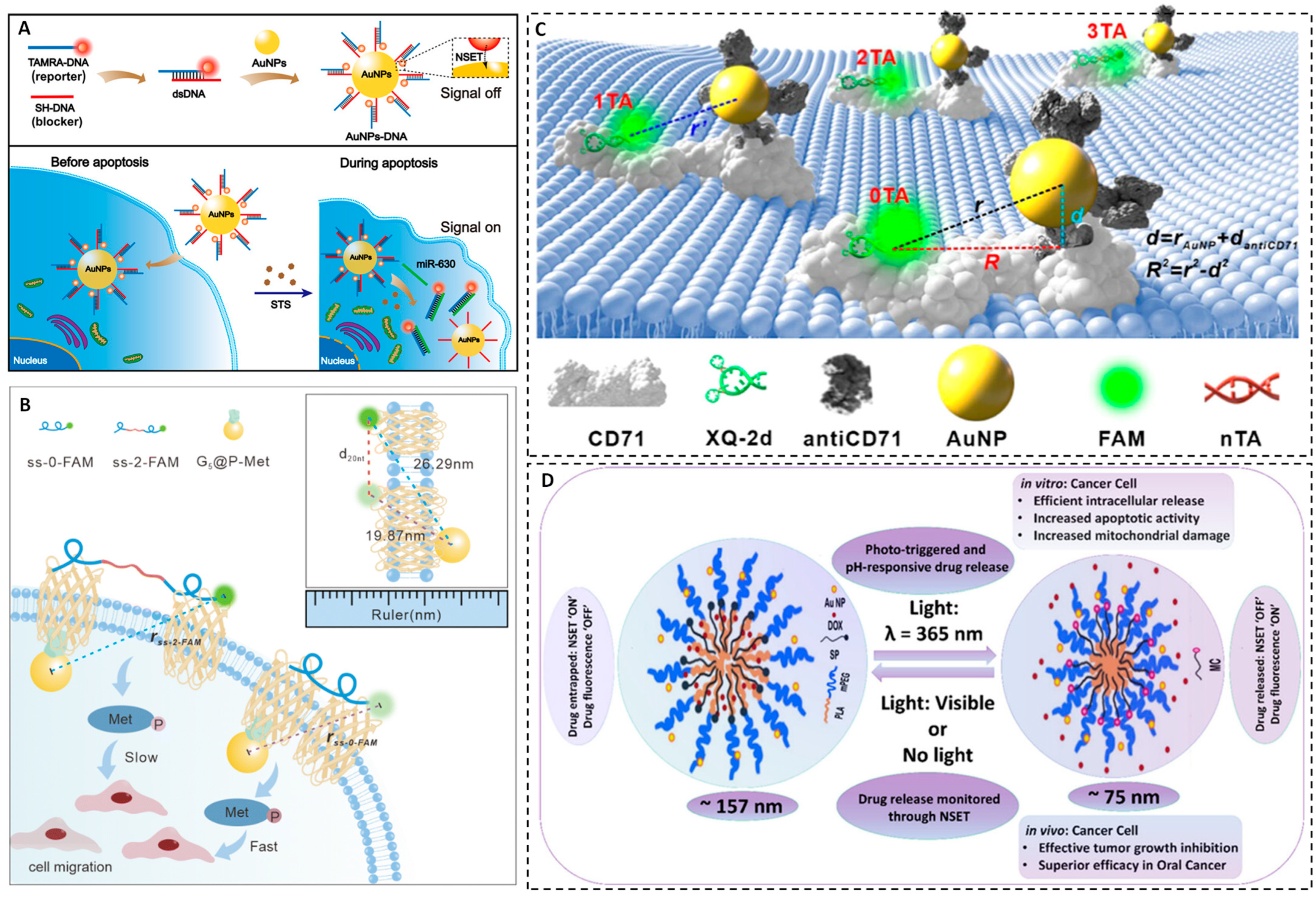

For example, Lin et al. engineered a AuNPs-based NSET “turn-on” fluorescent nanoprobe for real-time imaging of microRNA-630 (miR-630) expression during apoptosis in A549 cancer cells. In this system, a TAMRA-labeled DNA strand is hybridized with thiol-terminated DNA-functionalized AuNPs. The proximity of TAMRA to the AuNPs results in fluorescence quenching via NSET. Upon interaction with miR-630, the labeled DNA is released from the nanoparticle surface, which restores the fluorescence signal. This approach enables quantitative detection of miR-630 across a concentration range of 0.5–120 nM, with an LOD of 0.36 nM [

54]. The probe demonstrates high biocompatibility, nuclease stability, and selectivity, allowing real-time tracking of miR-630 levels during apoptosis induced by various chemotherapeutic agents (

Figure 5A).

Fang et al. introduced a transmembrane NSET ruler (T-Nanoruler) to synchronize the mapping of receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) dimerization geometry with intracellular phosphorylation activity in living cells [

55]. The T-Nanoruler consists of an extracellular single-stranded DNA aptamer (ss-n-FAM) to determine dimer spacing and intracellular antibody-conjugated AuNPs that target phosphorylated sites. Fluorescence quenching by AuNPs provides a direct readout of the nanoscale distance between receptor monomers and their phosphorylation status. This system enables real-time quantification of Met receptor activation, highlighting how tight receptor dimerization induces maximal phosphorylation and cell migration, while extended spacing suppresses these outcomes. The T-Nanoruler overcomes limitations of conventional FRET-based tools by offering longer detection distances and real-time resolution of both structural and functional receptor states (

Figure 5B).

Huang et al. developed a single-nucleobase-resolved NSET system to measure

R0 values between fluorescent dyes and AuNPs within living cell membranes [

56]. Their platform uses an aptamer–fluorophore complex that targets CD71 membrane receptors, with a variable nucleotide spacer controlling the distance between the fluorophore and the AuNP–antibody conjugate. This approach enables real-time determination of NSET radii in cellular environments, enhancing the precision of NSET probe design by optimizing AuNP–dye combinations for specific cellular targets (

Figure 5C). This represents a critical advancement in the rational construction of NSET biosensors, particularly for membrane-bound molecular events.

NSET-based strategies have also been translated into theranostic drug-delivery platforms. A recent study introduced a pH-responsive, photo-triggered micellar drug delivery system capable of releasing anticancer drugs while providing simultaneous, real-time tracking using NSET [

57]. This system incorporates an amphiphilic copolymer (mPEG-PLA), a spiropyran photoswitch, and doxorubicin (DOX) as the therapeutic cargo. In situ-synthesized AuNPs serve as NSET quenchers of DOX fluorescence, providing a readout of drug release. Under UV (365 nm) exposure and acidic conditions (pH 5.5) that mimic tumor microenvironments, the system demonstrates sustained DOX release, achieving up to 73.16% encapsulation efficiency (

Figure 5D). Time-resolved fluorescence studies confirm effective energy transfer during drug release, whereas in vitro and in vivo studies indicate high therapeutic efficacy in breast and oral cancer models. This platform exemplifies how NSET can integrate therapeutic delivery with dynamic feedback monitoring, a crucial feature of next-generation cancer nanomedicine.

Milad et al. developed a dual-excitation plasmonic surface energy transfer (PSET)-based biosensor for the simultaneous detection of

Escherichia coli and

Salmonella typhimurium. This system uses aptamer-functionalized AuNPs as capture probes and luminescent nanoparticles labeled with complementary DNA strands as signal reporters. Distinct luminescent signals from CdSe/ZnS QDs (excited at 350 nm) and NaYF

4:Yb,Er upconversion nanoparticles (excited at 980 nm) enabled precise, interference-free detection, with cross-talk eliminated using a dual-excitation strategy. The biosensor demonstrates high sensitivity, achieving LODs of 7.38 CFU/mL for

E. coli and 9.31 CFU/mL for

S. typhimurium [

58]. Validation using real lake water samples confirms its strong applicability for real-time environmental monitoring.

4.5. Metal Ion Detection

NSET-based sensors have demonstrated superior performance in detecting heavy metal ions such as mercury (Hg2+) and lead (Pb2+) using fluorescence and colorimetric readouts. These sensors typically employ nanoparticle–fluorophore assemblies, where the efficiency of energy transfer is modulated by analyte-induced conformational or aggregation changes.

A representative example is a label-free, cost-efficient “signal-on” fluorescence probe that combines functional nucleic acids (FNAs) and DNA-templated silver nanoclusters (DNA–AgNCs) with AuNRs serving as NSET acceptors [

14]. In this design, a DNAzyme–substrate complex incorporates AgNCs into the DNA strand. When Pb

2+ is absent, the DNAzyme maintains a duplex structure, positioning AgNCs close to the AuNRs and resulting in fluorescence quenching via NSET. Upon Pb

2+ binding, the DNAzyme is activated and cleaves its substrate, leading to a conformational change that separates the AgNCs from the AuNRs. This increased distance diminishes NSET efficiency and restores the fluorescence signal, following a “signal-on” detection mechanism. The sensor demonstrates high specificity for Pb

2+ over other metal ions and achieves an LOD of 1.416 nM in real river water samples (

Figure 6A).

Similarly, another NSET-based sensor utilizes S,N co-doped CDs (S,N–CDs) and AgNPs for sensitive detection of Hg

2+ [

59]. In this system, the fluorescence of S,N–CDs is quenched by AgNPs via both NSET and the inner-filter effect (IFE). Hg

2+ addition induces aggregation of AgNPs, increasing the interparticle distance and restoring the fluorescence of the S,N–CDs. This platform offers a broad linear detection range (1.5–2000 nM), with an LOD of 0.51 nM, and has been validated using environmental water samples.

Another innovative approach involves using PVA-capped 4-nitrophenylanthranilate (PVA-NPA) doped with AgNPs as a dynamic “turn-on” sensor for Hg

2+ detection based on NSET [

60]. The fluorescence of NPA is quenched by NSET in the presence of AgNPs; however, the introduction of Hg

2+ initiates amalgam formation with AgNPs, disrupting energy transfer and leading to fluorescence recovery. This method enabled ultrasensitive detection of Hg

2+ down to 0.5 nM, with a linear range of 0–1 ppb and demonstrates compatibility with real sample matrices (

Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

(

A) Schematic of DNAzyme-based Pb

2+ sensor via NSET between substrate-templated AgNCs and AuNRs, reproduced with permission from ref. [

14] Copyright 2022 American Chemical Society. (

B) Schematic representation of NSET-based fluorescence Hg

2+ sensor involving PVA–NPA and Ag NPs, reproduced with permission from ref. [

60] Copyright 2016 American Chemical Society.

Figure 6.

(

A) Schematic of DNAzyme-based Pb

2+ sensor via NSET between substrate-templated AgNCs and AuNRs, reproduced with permission from ref. [

14] Copyright 2022 American Chemical Society. (

B) Schematic representation of NSET-based fluorescence Hg

2+ sensor involving PVA–NPA and Ag NPs, reproduced with permission from ref. [

60] Copyright 2016 American Chemical Society.

Additionally, a QD–DNA–AuNP sensor has been developed for Hg

2+ detection. In this system, thymine–thymine mismatches in the DNA strand selectively bind Hg

2+ via the formation of T–Hg

2+–T bridges [

28]. This conformational change brings QDs and AuNPs into proximity, triggering NSET-based fluorescence quenching and producing a “turn-off” signal. The system achieves a detection limit of 2 nM in buffer and 1.2 ppb in river water, with strong selectivity against other metal ions such as Pb

2+, Cd

2+, and Ag

+.

For Pb

2+ detection, another fluorescence “turn-on” sensor was designed by suppressing NSET between acridine orange (AO) and AuNPs [

61]. In this system, AO fluorescence is quenched via energy transfer to AuNPs; however, the presence of Pb

2+ inhibits this interaction, thereby restoring fluorescence. This system achieves an LOD of 13 nM, demonstrates high reproducibility (RSD ≤ 1.75%), and has been validated for use in environmental matrices, confirming its suitability for field-level monitoring [

61].

Across these platforms, NSET acts as a versatile optical readout mechanism that translates analyte-induced structural changes in nanoprobes into measurable spectroscopic signals. Noble metal nanoparticles, especially AuNPs, are favored for their exceptional QE, which stems from their large extinction coefficients and SPR properties. Moreover, the R

−4 distance dependence of NSET allows for energy transfer over longer ranges than FRET, accommodating diverse probe geometries and conformational changes. A comprehensive list of NSET-based probes used for metal ion detection is provided in

Table 5.

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

NSET has emerged as a foundational technique for biosensing, enabling distance-sensitive detection of biomolecular interactions with nanoscale resolution. Its practical application in biomedical contexts has resulted in significant advancements; however, effective deployment requires a thorough understanding of its operational constraints and performance characteristics.

A principal advantage of NSET lies in its long-range sensing capability. Unlike FRET, which operates with a 1/R6 dependence and is effective over 1–10 nm, NSET follows a 1/d4 dependence, facilitating energy transfer over 30–40 nm. This extended range supports the detection of conformational changes in macromolecular complexes, membrane receptors, and long nucleic acid strands. The introduction of size-dependent refinements via the SET model further enhances the accuracy of energy-transfer predictions at the nanoscale, fostering the development of novel biosensor architectures that function under physiologically relevant conditions, including complex biological fluids and living systems. NSET also enables the monitoring of dynamic processes, such as telomere elongation and aptamer reconfiguration, with high spatial tolerance.

NSET offers greater spectral flexibility than FRET, as it does not require significant overlap between the donor emission and the acceptor absorption spectra. This allows a broader selection of donor–acceptor pairs, including fluorescent dyes, QDs, CDs, and noble-metal nanoparticles (e.g., gold and silver). The expanded compatibility enhances the versatility of NSET-based molecular probes and detection platforms. Moreover, NSET’s independence of dipole orientation simplifies sensor design and improves reproducibility in heterogeneous or fluidic biological environments.

Nanoparticle integration is central to the NSET design. AuNPs and AgNPs are commonly used due to their high extinction coefficients, plasmonic properties, and chemical tunability. These features facilitate high energy-transfer efficiencies and signal amplification. When conjugated to aptamers or antibodies, these nanoparticles create highly selective biosensing complexes capable of detecting a wide range of targets, from small ions to entire pathogens.

Despite these advantages, several limitations persist. Biocompatibility and cytotoxicity of metal nanoparticles are major concerns, particularly for in vivo imaging or therapeutic use. Although AuNPs are generally considered safe, prolonged exposure to high concentrations or the use of less inert metals (e.g., silver and copper) can induce oxidative stress and cell damage. Additionally, background quenching and signal interference are notable challenges in biological fluids, which contain numerous autofluorescent molecules and nonspecific quenchers that can obscure NSET signals. Strategies to mitigate these issues, such as surface passivation, ratiometric sensing, and time-gated fluorescence detection, add complexity to sensor design. Nanoparticle heterogeneity, including variations in size, shape, and surface chemistry, affects QE and distance calibration, impacting the accuracy of NSET-based rulers or quantitative assays. Addressing these inconsistencies may require advanced mathematical modeling or computational correction. Moreover, donor photostability can limit the duration of long-term measurements. For example, organic dyes are susceptible to photobleaching, while QDs may exhibit blinking or oxidative degradation under prolonged illumination. Additionally, fabricating stable, functional nanoconjugates, particularly for multiplexed or microfluidic platforms, poses engineering challenges that must be resolved for scalable clinical deployment. Moreover, NSET cannot be reliably used in ratiometric fluorescence experiments in the same manner as FRET. Ratiometric quantification in FRET relies on a specific photophysical condition in which the energy transferred from an excited donor to a discrete fluorescent acceptor, leading to a decrease in donor emission intensity accompanied by a proportional increase in acceptor emission intensity. This reciprocal relationship allows the donor-to-acceptor emission intensity ratio to serve as internally referenced metric for energy transfer efficiency. However, in NSET, the excited donor does not transfer energy to a fluorescent acceptor. Instead, it couples to the electronic continuum of a metal nanoparticle, where the excitation energy is dissipated non-radiatively through processes such as electron–hole pair generation. As a result, donor fluorescence quenching occurs without sensitized acceptor emission, and there is no corresponding emission channel that can be monitored for ratiometric analysis.

The future of NSET in biomedical sciences is oriented toward developing next-generation hybrid biosensors that combine NSET with other modalities, such as electrochemical, plasmonic, or magnetoresistive sensing. These multimodal platforms offer synergistic enhancements in sensitivity, selectivity, and real-time feedback. In addition, smart NSET systems, featuring stimuli-responsive linkers or switchable nanoparticle assemblies, are expected to improve spatiotemporal control in both diagnostics and therapeutics. Recent studies demonstrate that NSET is increasingly used beyond sensing, particularly for investigating fundamental photophysical and materials properties. For example, NSET has been exploited to enhance the antimicrobial activity of AgNPs against Gram-positive bacteria by facilitating efficient energy transfer from photoexcited ligands to the metal surface, thereby promoting nonradiative energy dissipation pathways [

64]. In addition, NSET has been explored as a strategy for controlling fluorescence brightness, photostability, and energy redistribution in nano-optical systems. By tuning emitter–metal separation, nanoparticle size, and surface chemistry, researchers have used NSET to systematically modulate nonradiative decay rates and probe how metallic nanostructures influence excited-state relaxation processes [

24,

65]. These studies highlight the utility of NSET not only as a signal transduction mechanism but also as a versatile tool for understanding and engineering light–matter interactions and energy dissipation pathways in nanoscale materials.

The convergence of NSET with machine learning and artificial intelligence holds tremendous potential in data-rich environments, where pattern recognition and predictive analytics can be used to interpret complex quenching profiles and biomolecular interactions. In parallel, the development of wearable and implantable devices that integrate NSET-based biosensors may revolutionize continuous health monitoring and personalized medicine.

Although NSET biosensors have transformative potential for biomedical diagnostics, their optimal deployment requires balancing design simplicity, biological compatibility, and signal fidelity. Continued research is necessary to develop biocompatible and biodegradable nanomaterials and to establish regulatory frameworks for clinical translation of NSET-based technologies. Advances in materials engineering, signal amplification, and surface modification will be pivotal for overcoming current limitations and advancing clinical translation. Ultimately, as fabrication techniques become more refined and cross-disciplinary collaborations expand, NSET is poised to play a central role in next-generation molecular diagnostics, targeted therapies, and precision healthcare.