Abstract

To enhance the sensitivity of graphene-DNA sensors for Hg2+ detection, a novel graphene nanoribbon-DNA sensor was fabricated using a template-assisted approach. Silicon nanowires served as templates to decorate the graphene device, followed by plasma etching to delineate graphene nanoribbons. After template removal, the resulting sensors based on silicon nanowire templates were successfully constructed. DNA sequences containing four guanine bases were conjugated with graphene sensors prepared using the templates. The carboxyl groups on the edges of the graphene nanoribbons were activated with EDC/NHS chemistry to facilitate covalent bonding with amino-modified DNA. The kinetic response and Hg2+ detection capability of the fabricated sensors were characterized using a semiconductor parameter analyzer. Results indicated that the silicon nanowire-templated graphene nanoribbon sensor exhibited high sensitivity, with a detection limit of 3.62 pM. This innovative approach further improved the sensitivity of graphene-DNA sensors for Hg2+ detection.

1. Introduction

A highly toxic heavy metal ion, mercury is widely present in the atmosphere, soil, and aquatic environments. Its toxic nature affects complex biological processes such as cellular metabolism, signal transduction, and gene expression, posing serious threats to human health and ecosystems. When exposed, mercury ions can cross the blood–brain barrier, damaging the central nervous system [1,2], and may also impair kidney function, leading to renal failure [3]. Long-term exposure can cause neurotoxicity, immune disorders, and multi-organ failure [2]. In ecosystems, mercury ions readily convert into methylmercury, accumulating in aquatic food chains, especially in fish [3,4], and disrupting aquatic life by inhibiting growth and disturbing ecological balance. Additionally, mercury contamination can impact terrestrial plants and soil microbes [4]. Due to these hazards, the World Health Organization (WHO, 5 nM) and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA, 2 ppb) have established exceedingly low safety thresholds [1,5]. Industrial processes risk abrupt release of high concentrations of mercury ions, resulting in environmental contamination and toxicity levels sufficient to cause significant health hazards, necessitating the detection sensitivity at the sub-micromolar or even nanomolar scale. Consequently, developing real-time, on-site visual detection methods for mercury ions is crucial [6,7]. Many countries have also established strict emission standards, requiring regular monitoring by industries [5]. Advances in detection technology have increased the potential for on-site, real-time measurement [1,8,9]. Consequently, creating highly sensitive, rapid, and portable visual detection systems for mercury ions is essential for early warning, risk assessment, and regulatory compliance, ultimately protecting human health and ecological stability.

The template method is a technique that precisely controls the morphology and structure of materials by introducing a tailored structure (template). Its main steps include template preparation, material synthesis, and template removal [10,11,12]. Depending on the type of template used, it can be classified into hard-template, soft-template, and composite template methods. Hard- and soft-template approaches are commonly used in sensor fabrication, with the hard template method especially employed for producing humidity sensors and composite piezoelectric materials. This involves using rigid templates, such as mesoporous silica or mesoporous carbon, which shape the material structure through filling or coating processes. Hard templates offer high stability and confinement, enabling precise control over the morphology and dimensions of the final materials [10,13,14,15,16]. The soft template method demonstrates excellent performance in the fabrication of high-frequency ultrasonic transducers and mesoporous materials. It employs non-rigid nanostructures as surfactants and polymers as templates, which facilitate the formation of materials through self-assembly or chemical reactions. The ease of template removal, mild processing conditions, and scalability make this approach highly suitable for large-scale production [13,16,17]. By integrating the advantages of both hard and soft templates, a synergistic effect is achieved that facilitates the formation of the material’s nanostructures [18]. Template methods are extensively employed in sensor fabrication, encompassing the synthesis of nanostructures [19,20], deposition of functional materials, preparation of molecularly imprinted polymers(MIPs) [21,22], and the development of specialized sensor types.

Silicon nanowires ingeniously integrate the material properties of silicon with the unique advantages of nanoscale structures, rendering them an ideal platform for the development of diverse biosensors [23]. In the field of biosensing, they are highly regarded for their high sensitivity, rapid response times, and exceptional electrical characteristics. Bai et al. successfully fabricated graphene nanoribbons (GNRs) with widths less than 10 nm by employing chemically synthesized silicon nanowires as physical protective masks during oxygen plasma etching. Atomic force microscopy analysis demonstrated that the resulting GNR patterns were a precise replication of the template’s nanowire morphology, enabling the formation of strip-like, branched, or intersecting graphene nanostructures [24]. Currently, GNRs, with a width controllable down to 6 nm, are successfully created. Additionally, GNR field-effect transistors (FETs) have been constructed, wherein the nanoribbons are directly connected to bulk graphene electrodes. This approach paved a novel pathway for the preparation of graphene nanostructures within the deep nanoscale regime, circumventing the need for complex lithographic techniques [25]. Consequently, it opened exciting new opportunities for the advancement of graphene nano-electronic device engineering.

This study reported the synthesis of graphene nanoribbons via chemical vapor deposition (CVD) [26,27,28]. Silicon nanowires served as templates, enabling plasma etching to pattern the graphene into ribbon structures. Subsequently, a brief ultrasonic treatment was employed to remove the masking layer, leaving behind the corresponding graphene nanoribbons. Gold electrodes were deposited using a resistance evaporation coating system, successfully fabricating a graphene nanoribbon-based sensor with silicon nanowires as templates. Four DNA sequences, comprising G bases, were subsequently functionalized onto the fabricated graphene nanoribbon sensor for downstream hybridization reactions. The sensor’s response to Hg2+ was characterized by monitoring its kinetic behavior and sensitivity using a semiconductor parameter analyzer (SPA).

2. Materials and Methods

Reagents and Experiments

DNA: 5′-CCACCACTTTTTTTTTGGGGTTTTTTTTT-3′, The DNA sequences used in the experiment were synthesized by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China) Co., Ltd., and their sequence accuracy was verified via HPLC purification and mass spectrometry. Ultrapure water (UP) used for HPLC was prepared using a laboratory ultrapure water system (UPF-10 L). All other solutions employed in the experiments were also prepared with UP water. The current profile was measured using a semiconductor parameter analyzer (SPA), and the data were processed with Origin software (Origin 2022, Northampton, MA, USA). For further details on other reagents and instruments, refer to Tables S1 and S2.

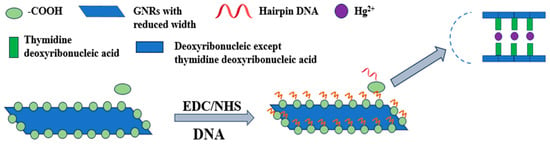

The prepared graphene nanoribbon sensors had edges functionalized with carboxyl groups (-COOH). After activation with EDC/NHS chemistry, a semi-stable Sulfo-NHS ester was generated, which could subsequently react with the amino groups (-NH2) to form amide bonds [29]. This enabled conjugation with NH2-terminated DNA strands, facilitating the fabrication of graphene nanoribbon-DNA biosensors (R-COOH + H2N-R′ → -C(O)-NH-R′ + H2O). These sensors were capable of detecting target analytes (e.g., Hg2+), with the underlying reaction mechanism illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the graphene nanoribbon-DNA biosensor for Hg2+ detection. Graphene nanoribbons possessed intrinsic carboxyl groups (-COOH) at their edges. Upon activation with EDC/NHS, these groups formed semi-stable Sulfo-NHS esters at the reaction sites. Amino-modified DNA then covalently attaches via nucleophilic attack, forming stable amide bonds. Subsequently, Hg2+ was selectively captured through the formation of T-Hg2+-T structures for detection purposes.

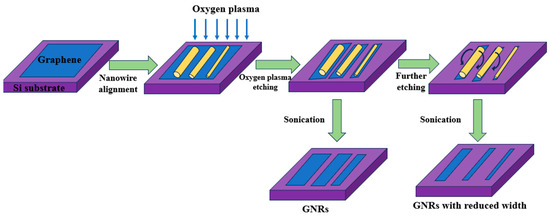

Based on the reported template method for silicon nanowire fabrication, and with reference to graphene nanoribbon preparation protocols, the process began by dispensing 200 μL of diluted silicon nanowire solution onto a pre-fabricated graphene device. To ensure intimate contact between the silicon nanowires and the graphene substrate, the substrate was briefly immersed in isopropanol (IPA) for 4–5 s, followed by nitrogen blow-dry to induce capillary forces. Subsequently, the devices were allowed to air dry naturally at room temperature. At this stage, the silicon nanowires were precisely positioned. The graphene device, now decorated with silicon nanowires, was then subjected to oxygen plasma etching, which introduced a high density of -COOH functional groups along the graphene edges. Final cleaning was performed via an ultrasonic bath to remove the silicon nanowire template, resulting in exposed graphene nanoribbons on the substrate. Electrical contacts were established through thermal evaporation of chromium and gold electrodes, ensuring a stable electrical connectivity for sensor operation. This process yielded graphene nanoribbon sensors, as illustrated in Figure 2. Utilizing this approach, graphene nanoribbon sensors templated with silicon nanowires were successfully fabricated.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the preparation of graphene nanoribbon sensors. Diluted silicon nanowires can physically be adsorbed onto graphene films, enabling oxygen ion plasma etching to remove graphene regions not protected by the template. Subsequently, brief ultrasonic treatment was employed to remove the silicon nanowire masking layer, resulting in graphene nanoribbons that precisely replicated the morphology of the original nanowires.

For sensors templated with silicon nanowires, 20 μL of activation solution containing 5 nM N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) and 500 nM 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) (EDC) (at a molar ratio of 1:100) was drop-cast onto the surface for pretreatment, followed by an overnight incubation at 4 °C. The devices were then rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) buffer and allowed to air-dry naturally. Subsequently, 20 μL of 40 nM DNA solution was drop-cast and incubated at 4 °C for 8 h to facilitate conjugation. After incubation, the surface was rinsed with PBS buffer to remove unreacted DNA strands, completing the fabrication of the graphene nanoribbon-DNA biosensor.

Finally, 20 μL of Hg2+ solutions with varying concentrations was added to the sensor surface, and the system was incubated at room temperature for 1 h. The resultant changes in electrical current were measured using a semiconductor parameter analyzer.

3. Results

In the initial phase, Raman spectroscopic characterization was conducted on graphene nanoribbon sensors fabricated using silicon nanowire templates. Analysis of the intensity ratio between the G and 2D peaks, along with peak position shifts, enabled the determination of the graphene layer number [30]. Monolayer graphene exhibited higher G and 2D peak intensities with a pronounced 2D peak near 2700 cm−1. Thus, confirming it was a monolayer graphene structure [31]. Relevant results were presented in Figure S1, confirming that the fabricated graphene nanoribbons were of monolayer nature. Figure S2 displayed the characterization of nanoribbons prepared using silicon nanowires as templates.

3.1. Optimization of DNA Concentration

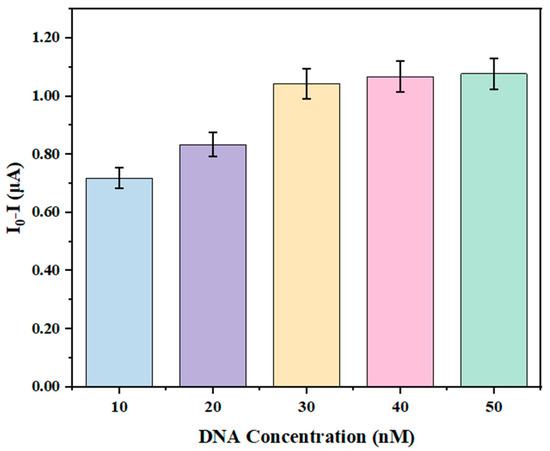

The concentration of DNA conjugated to graphene nanoribbon sensors fabricated with silicon nanowire templates was optimized. Initially, the baseline current I0 of the prepared graphene nanoribbon devices was measured. Following overnight activation of the sensor surface with EDC/NHS solution, varying concentrations of DNA solution (10 nM, 20 nM, 30 nM, 40 nM, and 50 nM) were drop-cast onto the surface and reacted at 4 °C for 8 h. Subsequently, the sensors were rinsed with PBS and air-dried naturally. The current I was measured using a semiconductor parameter analyzer, and the change in current (I0-I) was recorded.

As shown in Figure 3, the current change (I0-I) exhibited a gradual increase and approached a plateau with increasing DNA concentration for the silicon nanowire-templated sensors. When the DNA concentration reached 30 nM, the rate of current change became more gradual, stabilizing at this level. Therefore, a DNA concentration of 30 nM was selected for further studies involving silicon nanowire-templated graphene nanoribbon-DNA sensors.

Figure 3.

Optimization of DNA concentration in graphene nanoribbon-DNA sensors based on silicon nanowire templates.

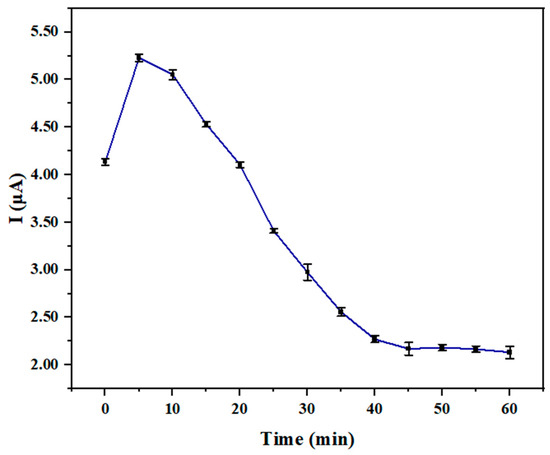

3.2. Optimization of Hg2+ Reaction Time

When Hg2+ interacted with a graphene nanoribbon-DNA sensor, it formed a T-Hg2+-T mismatch structure through coordinate bonding specifically with thymine (T) bases within the DNA molecule. This triggered a dual structural modulation: firstly, it induced intra- and inter-molecular folding of the DNA into dense hairpin-like or double-stranded conformations, significantly reducing steric hindrance and electrostatic repulsion among GNRs; secondly, the T-Hg2+-T mismatch acted as a molecular bridge, facilitating cross-linking between adjacent DNA-modified GNRs. This process ultimately drove the assembly of GNRs into microscale aggregates. The mechanism was directly mediated by conformational rearrangements of the DNA, representing the most fundamental structural response of GNRs to Hg2+ binding.

As shown in Figure 4, within the first 5 min after Hg2+ application, the graphene nanoribbon-DNA sensor prepared on a silicon nanowire template exhibited a sharp increase in current, which gradually declined with increasing reaction time. The emergence of this phenomenon was attributed to the enhancement of DNA’s affinity for Hg2+ by T-Hg2+-T base pair modifications, which directly influenced the electrochemical interface by altering the charge distribution at the electrode–solution boundary. Consequently, the stabilization of the DNA double helix promoted more effective electron transfer from the electrode through the DNA to the detection medium, which led to a marked increase in the peak current signal in electrochemical detection [32]. By 40 min, the current change plateaued and showed the saturation of the binding process. Due to the initial extensive chelation of Hg2+ with T-T, the available binding sites became saturated over time, leaving residual Hg2+ predominantly in weakly associated states. Concurrent surface passivation, thickening of the diffusion layer, and Hg2+ desorption/reoxidation collectively contribute to a decrease in electronically active transfer centers, resulting in an attenuation of the signal rather than further enhancement [33]. Therefore, 40 min was selected as the optimal reaction time for Hg2+-DNA interaction on this sensor. Leveraging this mechanism, the detection system could achieve rapid and sufficient accumulation of Hg2+ ions on the electrode surface within a short timeframe, effectively addressing the low target ion enrichment efficiency and lengthy analysis duration characteristic of conventional methods.

Figure 4.

The reaction time of graphene nanoribbon DNA sensors based on silicon nanowire template with Hg2+.

3.3. Sensitivity Testing

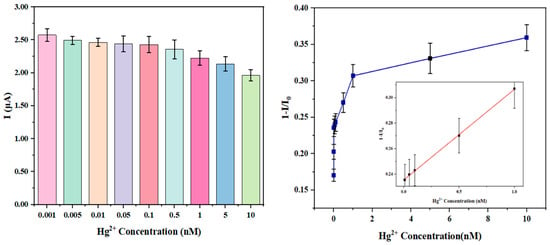

Graphene nanoribbon-DNA sensors fabricated with silicon nanowire templates were subjected to Hg2+ sensitivity analysis using a semiconductor parameter analyzer. The gate voltage was varied from −8 V to 8 V, while the source-drain voltage was maintained at −50 mV, and the initial current (I0) was recorded. Subsequently, solutions of Hg2+ at various concentrations (1 pM, 5 pM, 10 pM, 50 pM, 100 pM, 500 pM, 1 nM, 5 nM, and 10 nM) were drop-cast onto the sensor surface. The reaction was carried out at room temperature, with a reaction duration of 40 min. The semiconductor parameter analyzer was used to measure the current response under identical voltage conditions, recording the current values corresponding to each Hg2+ concentration.

In Figure 5, the correlation between Hg2+ ion concentration (ranging from 1 pM to 10 nM) and the sensor current was illustrated: as the Hg2+ concentration increased from 1 pM to 10 nM, the current exhibited a monotonic decline. Based on the specificity of the T-Hg2+-T coordination mechanism, this trend reflected the modulation of interfacial charge that suppresses charge carrier transport in the GNR. The sensor exhibited saturation beyond 1 nM during the response process; therefore, in order to ensure the reliability and linearity of the calibration curve, a fit was performed using the current response data at the first five characteristic points with concentrations ≤1 nM (0.01 to 1 nM), the ionic current response demonstrated a strong linear correlation with Hg2+ concentration (R2 = 0.997), described by the linear equation y = 0.07104x + 0.23555. This indicated that in the present concentration interval, the T-Hg2+-T coordination system remained unsaturated, with binding proportions increasing uniformly with concentration, and the signal response maintaining a stable concentration dependence. The maximum relative standard deviation (RSD) observed was 2.96%, which signified high reproducibility in mercury ion detection. Based on these findings, the detection limit was established at 3.62 pM, underscoring the sensor’s high precision in detecting trace levels of Hg2+. The LOD of this work had an advantage compared with that of other works, such as 1 nmol/L [1].

Figure 5.

Sensitivity analysis of Hg2+ detection using graphene nanoribbon-DNA sensors based on silicon nanowire template.

The selection of analytical methods required balancing sensitivity, selectivity, cost, portability, and analysis throughput. Table 1 provides synthesized data for a comprehensive comparison of the principal techniques. In comparison with the existing mainstream biosensor detection technologies, the graphene nanoribbon-DNA sensor developed in this study demonstrated a superior detection sensitivity. Conventional methods, such as fluorescence sensing, electrochemical sensing, and colorimetric detection, typically achieve detection limits for Hg2+ in the nanomolar (nM) to micromolar (μM) range. Although electrochemical techniques based on differential pulse anodic stripping voltammetry (DPASV) can analyze trace amounts of Hg2+, the graphene nanoribbon-DNA sensing system employed in this research further overcame sensitivity bottlenecks through its unique interfacial charge regulation mechanisms, including the inductive effects of T-Hg2+-T coordination and the modulation of carrier transport at GNR edge states. This approach enabled the sensor to exhibit enhanced trace detection performance while simultaneously surpassing the capabilities of traditional methods.

Table 1.

Comparison of mercury ion detection using various sensors.

To evaluate the reproducibility and storage stability of the graphene nanoribbon-DNA sensor for trace Hg2+ detection, targeted testing was carried out. Under identical experimental conditions at room temperature, the same sensor was used to perform no less than ten repeated measurements of the target analyte. The calculated RSD averaged approximately 2.8%, satisfying the reproducibility criteria for biosensors used in trace analysis. Additionally, the sensors used were stored at 4 °C within a vacuum chamber for 30 days, after which their current response was remeasured. The results demonstrated a signal retention rate of 93%, effectively ensuring the accuracy of detection. Collectively, the graphene nanoribbon-DNA sensor designed in this study exhibited outstanding performance characteristics.

3.4. Selectivity Analysis

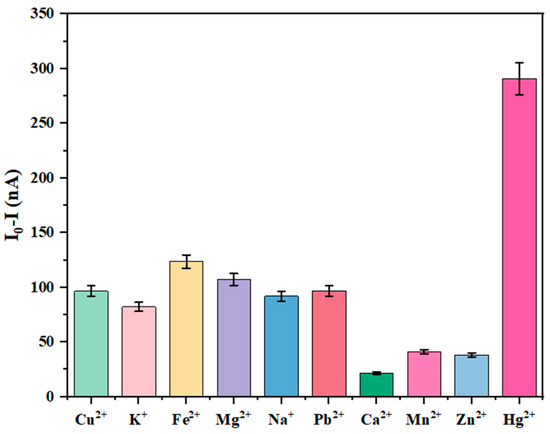

Various metal ions for selective analysis were selected. Under the optimal conditions described above, identical concentrations (1 nM) of different metal ions were introduced into graphene nanoribbon-DNA sensors fabricated with silicon nanowire templates. The sensors were incubated at room temperature for 40 min. The resulting current responses were measured using a semiconductor parameter analyzer, with the results depicted in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Selective analysis of Hg2+ using graphene nanoribbon DNA sensors based on silicon nanowire template.

Figure 6 illustrates the influence of different metal ions at an identical concentration (1 nM) on the current response of the graphene nanoribbon-DNA sensor: it was evident that only Hg2+ elicited a significant current response, far exceeding that of other ions, while responses from interfering ions such as Cu2+, K+, and Fe2+ were minimal. This disparity arose from the specificity of T-Hg2+-T coordination bonds and the charge modulation of GNR. Specifically, other metal ions (e.g., Cu2+, Fe2+, Pb2+) lacked the capacity for selective coordination with thymine bases; for example, Cu2+ interacted with DNA predominantly through non-specific electrostatic forces, preventing stable complex formation. Even weak interactions induced minimal interfacial charge changes, such as positive charge accumulation, which were substantially lower than those caused by Hg2+. As a result, Cu2+ maintained the sensor’s low-current response. Conversely, Hg2+ induced substantial positive charge accumulation at the GNR edges, effectively modulating the edge state carrier concentration and amplifying the current response. The weak electrostatic influence of interfering ions failed to induce notable changes in the edge states, resulting in a filtered response signal and conferring high selectivity of the sensor for Hg2+.

The observed decrease in current intensity upon addition of Hg2+ was remarkably greater than that caused by other metal ions. This showed that graphene nanoribbon-DNA sensors fabricated with silicon nanowire templates exhibited high selectivity and a significant response specifically to Hg2+. In summary, the results in Figure 6 confirmed that the selective recognition of Hg2+ by the graphene nanoribbon-DNA sensor was fundamentally mediated by the specific T-Hg2+-T coordination chemistry, with the charge-sensitive properties of GNR edge states further enhancing this selectivity, enabling precise detection of Hg2+ within complex ion matrices.

The introduction of Hg2+ ions promoted the formation of a stable “T-Hg2+-T” hairpin structure within the DNA, thereby impeding electron conduction and resulting in a significant reduction in current. Dithiothreitol (DTT) adsorbs Hg2+ effectively through its thiol (-SH) groups via strong coordination, restoring the electron transfer pathway and causing the current to increase. Upon subsequent addition of Hg2+, it bound to the thiol groups of DTT, forming a stable complex that reinhibited electron conduction and led to a decrease in current. This sensing system exhibited reversibility due to these mechanisms, as illustrated in Figure S3.

3.5. Detection in Actual Water Samples

Based on the sensitivity analysis, graphene nanoribbon-DNA sensors constructed using the templates demonstrated that those prepared with silicon nanowire as templates exhibited significantly higher sensitivity to Hg2+. The developed graphene nanoribbon-DNA sensor was systematically evaluated for its detection performance of target analytes, with Hg2+ serving as the model pollutant, in real-world samples. Standard solutions of Hg2+ at concentrations of 0.01 nM, 0.05 nM, 0.1 nM, 0.5 nM, and 1 nM were prepared, while simultaneously collecting Yangtze River water samples to simulate environmental water testing scenarios. To ensure analytical accuracy, the river samples underwent pre-treatment via filtration through 0.22 μm membrane filters to effectively remove particulate impurities, thus minimizing interference in detection outcomes. The sensor demonstrated excellent performance in detecting known Hg2+ concentrations; recovery rates ranged stably from 97.38% to 114.69% (Table 2), indicating its capability to accurately quantify the true Hg2+ levels in solutions. Relative standard deviations (RSD) were maintained between 2.87% and 3.25%, further confirming the stability and reliability of the measurements. After applying the sensor to Yangtze River water samples, the Hg2+ concentration was measured at 142.35 pM. Consequently, this validated the sensor’s reliability, accuracy, and potential utilization for in situ environmental surveillance.

Table 2.

The detection results of Hg2+ solution with known concentrations.

To address the insufficiency of real-sample validation, we supplemented gold-standard inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) cross-validation, which systematically verified the accuracy and reliability of the quantitative results of the graphene nanoribbon-DNA sensor. The results showed that the ICP-MS detection value was 138.67 pM, and the relative deviation from the sensor’s measured value (142.35 pM) was only 2.65%, falling within the acceptable error range (<5%) for trace heavy metal analysis in environmental samples. This high consistency confirmed that the sensor’s quantitative results were highly comparable to the gold-standard ICP-MS method, validating both the accuracy of the measured Hg2+ concentration in the Yangtze River sample and the sensor’s reliability for detecting trace Hg2+ in complex environmental matrices.

This sensor offered high sensitivity combined with field-deployable capabilities, with analysis completed within 40 min using a label-free, single-step incubation mode, and required minimal sample preparation. The custom-designed portable device maintained low manufacturing costs, enabling deployment in remote regions. The detection relied on DNA-specific recognition via T-Hg2+-T base pairing, providing robust anti-interference in complex environmental matrices. However, its linear detection range was narrow (0.01–1 nM), limiting its applicability for high-concentration Hg2+ detection. Future improvements could involve optimizing DNA grafting density or graphene nanoribbon aspect ratios or integrating standardized portable readout devices. The method achieved a favorable balance among sensitivity, detection speed, cost, and on-site usability, establishing itself as a highly competitive practical alternative for environmental mercury ion monitoring, particularly suited to rapid, low-cost, and in-field testing scenarios.

4. Conclusions

In this study, a template-assisted fabrication approach was used to develop a type of graphene nanoribbon-based DNA sensor, utilizing silicon nanowires as templates. The templates were physically adsorbed onto the graphene device surface and subsequently patterned through oxygen plasma etching, precisely producing GNRs with shapes conforming to that of the templates. The edges of etched GNRs were functionalized with abundant carboxyl groups. Chromium and gold electrodes were deposited via high-vacuum resistance evaporation, with the two gold electrodes serving as the source and drain, respectively. Thereby, GNR-based sensors were constructed. The fabricated sensors were activated using EDC/NHS chemistry, followed by conjugation with amino-modified DNA through amide bond formation with Sulfo-NHS ester-activated carboxyl groups. The response kinetics of these sensors to Hg2+ were characterized using a semiconductor parameter analyzer, revealing a detection limit of 3.62 pM for sensors fabricated with silicon nanowire. The graphene nanoribbon-DNA sensor designed in this study exhibited several key advantages for Hg2+ detection: it offered straightforward operation, rapid response times, visual readouts, and ease of integration into existing systems. More importantly, its sensitivity surpassed that of current comparable detection methodologies.

Mercury ion detection has evolved from traditional large-scale analytical instruments to a modern sensing era centered on innovative materials and new detection principles. The application of fluorescence, electrochemical, and other techniques demonstrated significant potential for real-time, on-site monitoring across various fields. Future research should address challenges related to stability, interference resistance, and cost efficiency. Through interdisciplinary integration, the goal was to advance technological industrialization and system integration, thereby supporting mercury pollution control and safeguarding public health.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/chemosensors13120431/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.D. and L.G.; methodology, J.D.; validation, H.S.; formal analysis, V.A.; investigation, M.B.; data curation, B.X.; writing—original draft preparation, J.D.; writing—review and editing, V.A. and B.X.; supervision, L.G.; project administration, L.G.; funding acquisition, B.X. and L.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSAF, No. U2230132), General Research Projects of Jiangsu Provincial Health Commission (M2024099), Guiding Science and Technology Plan Project for Social Development in Zhenjiang City (FZ2022052), and Zhenjiang Science and Technology Plan (Social development, SH2024098 and SH2024030), and the National Foreign Experts Program Project of China (H20240553).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Xing, X.; Zhang, Y.; Tan, Y.; Hu, T.; Chen, Z.; Liu, B. A multi-Well SERS chip for the detection of Hg2+. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2024, 7, 17287–17294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Chang, W.; Cai, Z.; Yu, C.; Lai, L.; Zhou, Z.; Li, P.; Yang, Y.; Zeng, C. Hg2+ detection and information encryption of new [1+1] lanthanide cluster. Talanta 2024, 26, 125105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, P.; Liu, J.; Xia, C.; Liu, B.; Zhu, H.; Niu, X. Matrix redox interference-free nanozyme-amplified detection of Hg2+ using thiol-modified phosphatase-mimetic nanoceria. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2024, 401, 135030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poornima, V.; Alexandar, V.; Iswariya, S.; Perumal, P.T.; Uma, T.S. Gold nanoparticle-based nanosystems for the colorimetric detection of Hg2+ ion contamination in the environment. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 46711–46722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres Landa, S.D.; Reddy Bogireddy, N.K.; Kaur, I.; Batra, V.; Agarwal, V. Heavy metal ion detection using green precursorderived carbon dots. iScience 2022, 25, 103816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleem, M.; Lee, K.H. Optical sensor: A promising strategy for environmental and biomedical monitoring of ionic species. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 72150–72287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiva Prasad, K.; Shruthi, G.; Shivamallu, C. Functionalized silver nano-sensor for colorimetric detection of Hg2+ ions: Facile synthesis and docking studies. Sensors 2018, 18, 2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, W.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, R.; Xiong, Q.; Shen, X.; Guo, J.; Chen, X. A benzoxazole-based fluorescent probe for visual detection of Hg2+. Acta Chim. Sin. 2013, 71, 1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.N.; Ren, W.X.; Kim, J.S.; Yoon, J. Fluorescent and colorimetric sensors for detection of lead, cadmium, and mercury ions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 3210–3244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, K.M.; Nekoba, D.T.; Viernes, K.L.; Zhou, J.; Ray, T.R. Fabrication of high-resolution, flexible, laser-induced graphene sensors via stencil masking. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2024, 264, 116649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, R.; Ohno, T.; Ozaki, J. Efficient preparation of carbon materials composed of warped graphene layers via in-situ nano-templating and estimation of oxygen reduction reaction activity. Carbon 2024, 221, 118910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Su, X.; Esmail, D.; Buck, E.; Tran, S.D.; Szkopek, T.; Cerruti, M. Dual-templating strategy for the fabrication of graphene oxide, reduced graphene oxide and composite scaffolds with hierarchical architectures. Carbon 2022, 189, 186–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoshal, T.; Senthamaraikannan, R.; Shaw, M.T.; Lundy, R.; Selkirk, A.; Morris, M.A. Fabrication of graphoepitaxial gate-all-around Si circuitry patterned nanowire arrays using block copolymer assisted hard mask approach. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 9550–9558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrio, J.; Volokh, M.; Shalom, M. Polymeric carbon nitrides and related metal-free materials for energy and environmental applications. J. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 8, 11075–11116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, M.; Goto, S.; Tang, R.; Yamazaki, K. Toward three-dimensionally ordered nanoporous graphene materials: Template synthesis, structure, and applications. Chem. Sci. 2024, 15, 1953–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, F.; Neshumayev, D.; Konist, A. Synthesis strategies and hydrogen storage performance of porous carbon materials derived from bio-oil. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 505, 159381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Shang, Q.; Li, J.; Qiu, J.; Tu, M.; Tong, Y.; Gu, J. Archetype mesoporous UiO-66(Zr) enabled by the salt–oil synergetic mechanism. J. Am. Chem. Soc. Au 2025, 5, 3299–3310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Chen, Y.; Yan, L.; Gong, Q.; Chen, G.; Yang, L.; Wu, Q.; Wang, X.; Hu, Z. The composite-template method to construct hierarchical carbon nanocages for supercapacitors with ultrahigh energy and power densities. Small 2022, 18, 2107082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahal, R.; Rathee, R.; Dahiya, S.; Punia, R.; Maan, A.S.; Singh, K.; Tripathi, R.; Manthrammel, M.A.; Shkir, M.; Ohlan, A. Mesoporous Ni0.5Cu0.5Co2O4@Co3O4 Nanostructures: Template-assisted synthesis and RGO hybridization for high-performance electromagnetic shielding. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 520, 165715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Sun, J.; Khade, R.L.; Chou, T.; An, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H. Liposome-templated green synthesis of mesoporous metal nanostructures with universal composition for biomedical application (Small 46/2023). Small 2023, 19, 2370383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, A.S.; Ramos, M.P.; Herrero, R.; Vilariño, J.M.L. Design, synthesis and HR–MAS NMR characterization of molecular imprinted polymers with emerging contaminants templates. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 257, 117860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begum, S.; Hassan, Z.; Bräse, S.; Wöll, C.; Tsotsalas, M. Metal-organic framework-templated biomaterials: Recent progress in synthesis, functionalization, and applications. Acc. Chem. Res. 2019, 52, 1598–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, M.; Hu, J.; Li, X.; Liu, J.; Jiang, R.; Shi, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Gao, H.; et al. Exosomal membrane proteins analysis using a silicon nanowire field effect transistor biosensor. Talanta 2024, 278, 126534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, J.; Duan, X.; Huang, Y. Rational fabrication of graphene nanoribbons using a nanowire Etch Mask. Nano Lett. 2009, 9, 2083–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izquierdo, N.; Li, R.; Christenson, P.R.; Oh, S.-H.; Koester, S.J. Dielectrophoresis-enhanced graphene field-effect transistors for nano-analyte sensing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 32764–32772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, D.; Cai, C. Synthesis and characterization of graphene on copper foil via atmospheric pressure chemical vapor deposition method and its impact on electrical properties. Carbon 2024, 230, 119640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Yuan, G.; Gao, L.; Yang, J.; Chhowalla, M.; Gharahcheshmeh, M.H.; Gleason, K.K.; Choi, Y.S.; Hong, B.H.; Liu, Z. Chemical vapour deposition. Nat. Rev. Methods Prim. 2021, 1, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Cui, G.; He, Y.; Ci, H. Guiding graphene growth on insulators via energy strategies in chemical vapor deposition. Small 2025, 21, 2502798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virdi, J.K.; Dusunge, A.; Handa, S. Aqueous micelles as solvent, ligand, and reaction promoter in catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. Au 2024, 4, 301–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandee, R.; Chowdhury, M.A.; Hossain, N.; Rana, M.M.; Mobarak, M.H.; Islam, M.A.; Aoyon, H. Experimental characterization of defect-induced raman spectroscopy in graphene with BN, ZnO, Al2O3, and TiO2 Dopants. Results Eng. 2024, 21, 101738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrowolski, A.; Jagiełło, J.; Czołak, D.; Ciuk, T. Determining the number of graphene layers based on raman response of the Si Csubstrate. Phys. E Low-Dimens. Syst. Nanostruct. 2021, 134, 114853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, J.; Gan, Y.; Liang, T.; Hu, Q.; Wang, Q.; Ren, T.; Sun, Q.; Wan, H.; Wang, P. Graphene FET array biosensor based on ssDNA aptamer for ultrasensitive Hg2+ detection in environmental pollutants. Front. Chem. 2018, 6, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saha, K.K.; Drndic, M.; Nikolic, B.K. DNA nucleotide-specific modulation of μAtransverse edge currents through a metallic graphene nanoribbon with a nanopore. Nano Lett. 2012, 12, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, Y.; Shen, J.; Fan, A. Colorimetric method for the detection of mercury ions based on gold nanoparticles and mercaptophenylboronic Acid. Anal. Sci. 2017, 33, 925–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tlized Silver Nanoparticlealodthaisong, C.; Sangiamkittikul, P.; Chongwichai, P.; Saenchoopa, A.; Thammawithan, S.; Patramanon, R.; Kosolwattana, S.; Kulchat, S. Highly selective colorimetric sensor of mercury(II) ions by and rographolide-stabis in water and antibacterial evaluation. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 41134–41144. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, J.; Zhu, W.; Du, X.; Din, Z.; Xie, F.; Zhou, J.; Cai, J. Robust synthesis of GO-Pt NPs nanocomposites: A highly selective colorimetric sensor for mercury ion (II) detection. Am. Chem. Soc. Omega 2023, 8, 46292–46299. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Wu, Y.; An, S.; Yan, Z. Au NP-decorated g-C3N4-based photoelectochemical biosensor for sensitive mercury ions analysis. Am. Chem. Soc. Omega 2022, 7, 19622–19630. [Google Scholar]

- Sibit, N.H.; Roushani, M.; Karazan, Z.M. Electrochemical determination of mercury ions in various environmental samples using glassy carbon electrode modified with poly (L-tyrosinamide). Ionics 2024, 30, 1101–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Wang, J.; Xue, X.; Jiang, H. Colorimetric detection of Hg2+ based on the enhanced oxidase-mimic activity of CuO/Au@Cu3(BTC)2 Triggered by Hg2+. R. Soc. Chem. Adv. 2024, 14, 13808–13816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Wang, S.; Azad, F.; Su, S.C.J.E.; Safety, E. Single-step synthesis of polychromatic carbon quantum dots for macroscopic detection of Hg2+. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 190, 110141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, U.; Manickam, S.; Iyer, S.K. Turn-off fluorescence of imidazole-based sensor probe for mercury ions. Sens. Diagn. 2024, 3, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, S.; Swamy, K.M.K.; Zan, W.-Y.; Yoon, J.; Liu, S. An excimer process induced a turn-on fluorescent probe for detection of ultra-low concentration of mercury ions. J. Mater. Chem. B 2024, 12, 8376–8382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).