Abstract

Background: Individualized care in veterinary practice optimizes pharmaceutical dose regimens, facilitates disease prevention, and supports animal health by considering the animal’s individual profile. Three-dimensional (3D) printing is a suitable technology for manufacturing both tailored drugs and supplements with enhanced efficacy and reduced adverse reactions. Zinc is used to correct deficiencies, support growth, boost the immune system, and treat specific conditions like zinc-responsive dermatosis in dogs. The purpose of the study was to develop and analyze tailored zinc-loaded filaments for the design of custom-made 3D-printed shapes. Methods: Zinc oxide (ZnO) and artificial beef flavor were incorporated into hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (HPMC) and hydroxypropyl cellulose (HPC), respectively, to produce tailored 5% or 10% ZnO-containing filaments for 3D printing. The obtained filaments and 3D-printed forms were characterized using sieve analysis, moisture determination, melting point, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), and X-ray diffraction analysis. Results: The characterization of two placebo and four custom-made 3D-printed ZnO supplements suggested that HPMC is a polymer with poor processability, whereas HPC is suitable for incorporating artificial beef flavor and ZnO. FTIR analysis indicated no interaction between the components. Conclusion: The HPC and 10% flavor mixture can be applied as a matrix for manufacturing 3D-printed forms with ZnO for individualized animal care.

1. Introduction

The mass production of drugs and supplements, especially in veterinary medicine often does not provide a satisfactory therapeutic effect, which is required for individual animals or specific veterinary conditions. Individualized dose intensity is dependent on the animal’s body size, adverse reactions, and pharmacokinetic data. Personalized medicine represents a transformative advancement in veterinary care, aiming to improve the effectiveness, safety, and individualization of treatments [1,2]. This approach allows for tailored dosing strategies, innovative drug combinations, and patient-specific selection or adjustment of therapies. Strategies for therapy tailored to individual animals require not only well-designed clinical studies but also the development of adjustable, affordable, and assessable pharmaceutical forms [3]. Compared to conventional drug preparation methods, three-dimensional (3D) printing offers unparalleled flexibility in designing pharmaceutical formulations, customizing dosages and drug combinations, and accelerating manufacturing and prototyping processes. Three-dimensional-printed forms allow for precise control over drug release profiles, support a wide range of clinical applications, and offer highly personalized pharmaceutical solutions [4]. Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM), where drug-loaded filaments of polymers are prepared by hot-melt extrusion (HME) and printed by 3D printers, is probably the most popular 3D printing method due to its available and simple equipment, the opportunity to develop a variety of 3D-printed structured forms, rapid prototyping, and low-volume production [5]. FDM works by applying thermoplastic materials layer by layer and thus creating a variety of geometrical shapes [6]. The mechanical properties of 3D-printed forms can be precisely adjusted by choosing appropriate materials and selecting adequate printing parameters. FDM produces 3D-printed forms with high mechanical stability, lower resolution, and a rougher surface finish [7]. In addition, FDM requires prefabricated drug-containing filaments with suitable mechanical properties. Low drug–polymer miscibility and limited stability on higher temperatures add to the challenge of producing drug-loaded filaments adequate for FDM [8]. Mixing drugs, additives, and polymers to form filaments for printing may lead to various interactions. Although generally regarded as pharmacologically inactive, excipients can initiate, contribute to, or exacerbate chemical and physical interactions with active drug compounds, potentially compromising the medication’s efficacy [9]. Thus, spectroscopic methods, including Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), often become crucial in determining the possible drug–additives, drug–polymer, or additives–polymer interactions that affect the obtained tailored filaments for custom-made 3D-printed forms [10].

Zinc is an essential trace element that functions as a cofactor for numerous enzymes and plays critical catalytic, structural, and regulatory roles. In dogs, zinc deficiency is known to decrease the activity of Zn-dependent enzymes in plasma and tissues and impair growth. Additionally, it can lead to skin lesions, behavioral disturbances, thymic atrophy, and compromised immune function. The causes of zinc deficiency include inadequate dietary intake, genetic disorders affecting Zn absorption, or interference from dietary components that hinder Zn bioavailability [11]. In pathological conditions such as dermatosis, adequate Zn supplementation is necessary. A study conducted on dogs indicated that half of the dogs supplemented with zinc developed recurrent lesions because the doses were missed or were lower than required [12], indicating the necessity for individualization of the therapy in veterinary practice.

FDM offers rapid development of new tailored zinc-loaded formulations, thus enabling a quick response to the specific health requirements of animals. The use of biocompatible and biodegradable materials ensures consumer (animal) safety, and at the same time, contributes to the reduction in plastic waste production [13]. However, the development of 3D custom-made pharmaceutical forms of both drugs and supplements is followed by challenges in establishing regulatory guidelines and ensuring compliance with safety and efficacy standards [14]. In addition, the flexibility of printing parameters and material characteristics can affect the final product, which requires constant control and monitoring [15,16]. Thus, introducing FTIR analysis as the standard method for the characterization of tailored drug- or supplement-loaded filaments obtained in hot-melt extrusion may be the key step in the quality control of custom-made 3D printed pharmaceutical forms.

In this study, tailored zinc-loaded filaments with and without artificial beef flavor (ABF) for the design of custom-made 3D-printed shapes were developed and compared to placebo forms. Sieve analysis, moisture determination, melting point, FTIR, DSC analysis, and visual inspection were applied for their characterization, with FTIR being essential for understanding the rationale behind the selection of the tailored zinc-loaded filaments.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The following raw materials were used to produce the filaments: hydroxypropyl cellulose (HPC, donation from Galenika, Belgrade, Serbia); hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (HPMC, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany); ABF (PF Inc., Melbourne, FL, USA); and zinc oxide (Centrochem, Stara Pazova, Serbia).

Accurate mass measurements were conducted on an analytical balance (Radwag, Radom, Poland). The filaments were prepared by using a NoztekTouch extruder (Noztek, Shoreham-by-Sea, UK). Loss on drying of the powders was performed using a moisture analyzer (Radwag, MA 50.R, Poland) with an automatic measurement of mass change during heating to achieve the constant mass. The Ultimaker 3s device (Ultimaker, Copenhagen, Denmark) was applied for the 3D printing. An inversion mixer (Pharmalabor, Milan, Italy) was used for the mixing of HPC, ABF, and ZnO. A melting point capillary device (Electrothermal, Basildon, UK) was used to determine the melting point of HPC and HPMC. Images of filaments and 3D-printed shapes were taken by using a ZEISS STEMI 508 stereo microscope with an AXIOMCAM ERc 5s camera (ZEISS EVO, Jena, Germany).

2.2. Sieve Analysis

Particle size distribution for HPC, HPMC, ABF, and zinc oxide was determined by size particle analysis on a vibrating sieve (Retsch, Haan, Germany). Sifting was performed using 355 μm, 250 μm, 180 μm, 125 μm, and 90 μm sieves. For each component, a sample of 25 g was placed on the coarsest sieve and constant sieving was carried out for 2 min at an amplitude of 1 mm. The test was performed in accordance with the requirements of the European Pharmacopoeia 11th Edition (Ph. Eur. 11) [17] for determining the bulk density of powders (Chapter 2.9.34).

2.3. Loss on Drying

The loss on drying test was carried out by transferring 1 g of powder on the vessel of the moisture analyzer (Radwag, MA 50.R, Poland) and spreading it evenly. The samples were dried at a temperature of 105 °C until a constant mass was obtained, in accordance with the guidelines of Ph. Eur. 11 [17] (Chapter 2.2.32).

2.4. Melting Point Determination

The melting point was determined by transferring the pure substance to a glass capillary that was placed on a melting point instrument (Electrothermal, Great Britain). The melting point was recorded when (i) melting begins and (ii) the melting of the entire mass in the capillary is completed. The precise determination of the melting point was a crucial step in setting the extrusion temperature slightly below the melting point (glass transition temperature).

2.5. Filaments Production by Hot-Melt Extrusion

The production of filaments was conducted in two phases. In the first phase, two cellulose derivatives, HPC and HPMC, were tested for their features when combined with ABF to produce tailored filaments. In the second phase, the polymer that showed better extrudability with flavoring was selected for designing zinc oxide-containing filaments for the production of solid 3D-printed shapes.

2.5.1. The Composition of the Mixture for Filaments Production

The powders were measured into a box in a manner to occupy a maximum of 70% of the box’s volume. The powders were mixed using the shuffling technique with a mixer (Pharmalabor, Italy).

The placebo filament formulations contained either pure polymer or a mixture of polymer with 10 or 20% ABF. The composition of the placebo filaments is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

The composition of the placebo filaments.

After the testing of placebo filaments was carried out, a polymer was selected and formulations with zinc oxide with ABF were produced. The composition of zinc oxide-containing mixtures used for filaments production is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

The composition of zinc oxide-containing tailored filaments.

2.5.2. Filaments’ Extrusion and Extrudability Evaluation

Extrudability of two placebo and four zinc oxide-containing filaments was assessed based on their physical features: color, surface appearance, ability to curl, and expandability of the filament diameter at the exit of the extruder nozzle. Filament extrusion was performed on a single-screw extruder (NoztekTouc, Great Britain). The heaters of the extruder melted the mixture into a viscous thermoplastic mass, which hardened at the exit from the extruder screw. The extrusion temperature was adjusted to achieve filament constant and non-expansive rate output at the exit of the extruder nostril. The details of the filaments during the extrusion process were monitored and recorded by a ZEISS STEMI 508 stereo microscope with an AXIOMCAM ERc 5s camera.

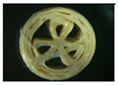

2.6. Three-Dimensional Printing of the Tailored Filaments

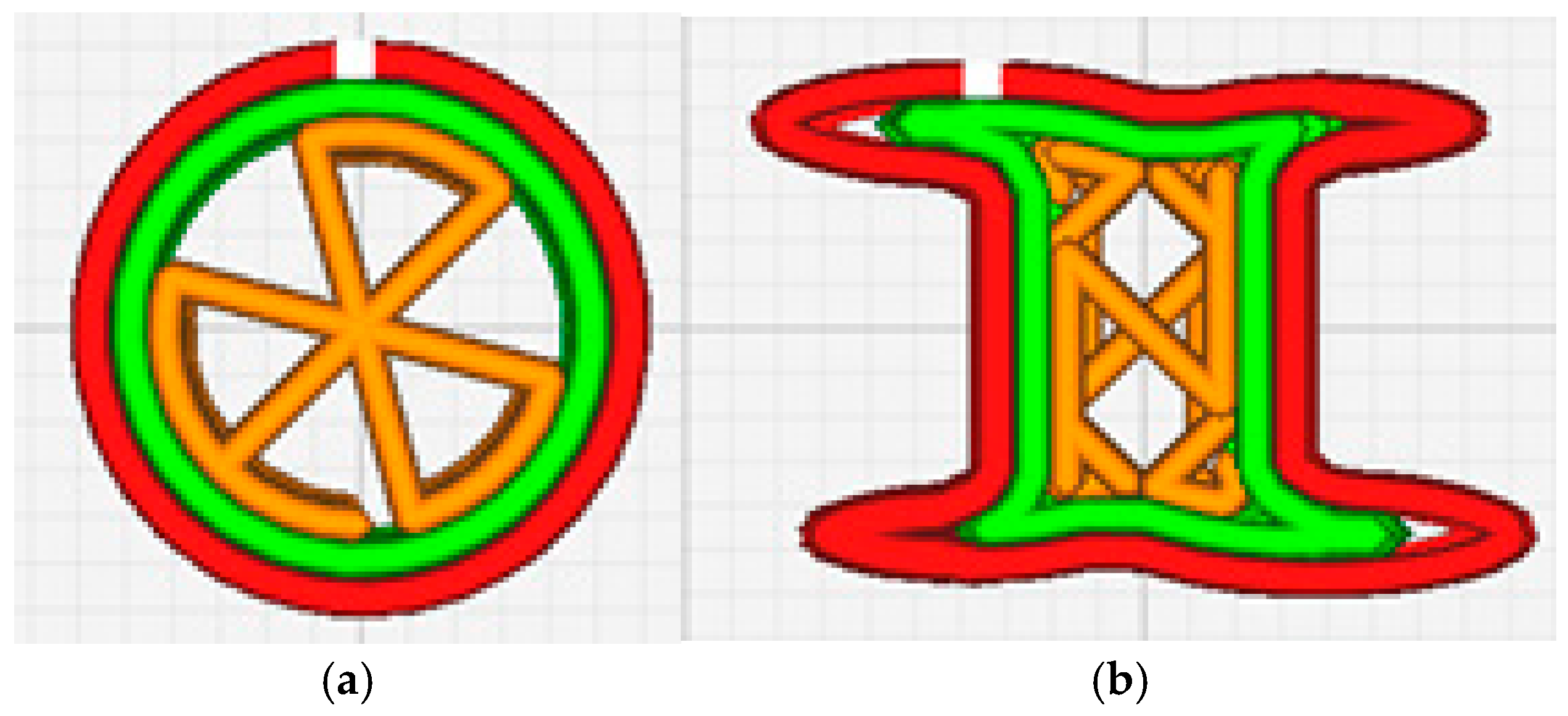

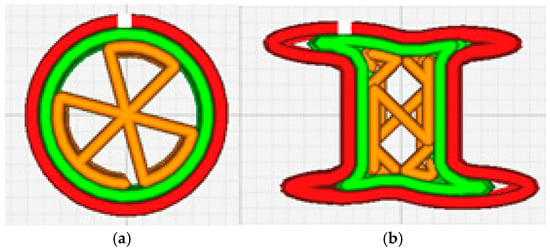

The UltiMaker model 3s (Ultimaker, Denmark) was used for printing 3D shapes of zinc oxide containing tailored veterinary forms by adjusting the printing parameters in the UltimakerCura program (v5.9, Ultimaker, Denmark). Two shapes were arranged in the 3D Bullider software (V20.0.4.0) and printed: a cylinder and a bone. The cylinder was selected as the most common pharmaceutical oral form, while bone-shaped pellets were considered as the form most often used for treats or snacks for dogs. A 25% fill and a triangle pattern for the cylinder and a zig-zag pattern for the bone were applied in the 3D printing process of the veterinary forms (Figure 1a,b). The temperature was adjusted by 5% successive increments until the constant and non-expansive rate output of the melted filament through the nostril was obtained. A BB0.8 nozzle and a printing speed of 25 mm/s were used. The thickness of the layer was 0.2 mm, and the temperature of the plate was 60 °C. The images of the printed 3D shapes were taken using a ZEISS STEMI 508 stereo microscope with an AXIOMCAM ERc 5s camera.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of 3D-printed shapes (a) cylinder and (b) bone.

2.7. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

The pure substances (ZnO, ABF, and HPC), as well as the tailored filaments and custom-made 3D-printed shapes were subjected to Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR). An FTIR spectrophotometer (Nicolet IS10, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) was used for the analysis of the samples and the results obtained were processed with Omnic 8.1 software (Thermo Scientific, USA). The spectral range was set between 4000 cm−1 to 400 cm−1 with a resolution of 4 cm−1. A blank was recorded before each sample was set for analysis and 32 separate interferograms were measured for each sample.

2.8. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) was applied to determine the glass transition temperature (Tg) for HPC. Analysis was performed on a differential scanning calorimetry device (Q20, TA instruments, New Castle, DE, USA). A sample mass of 3 mg to 5 mg was transferred in hermetically sealed aluminum containers and heated at a temperature of 30 °C to 180 °C, at a heating rate of 10 °C min−1. Calibration was performed with indium. The sensitivity of the instrument was 10 mV cm−1.

2.9. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

The crystallinity of the starting materials, ZnO, ABF, and HPC, the zinc-loaded filaments with and without ABF, and the 3D-printed forms were evaluated with X-ray Diffraction (XRD). A Rigaku MiniFlex 600 diffractometer (Rigaku, Tokyo, Japan) with monochromatic CuKα radiation was used for the measurements of the samples. The diffractograms were obtained under operating conditions set to 40 kV and 15 mA, with scanning parameters of 2θ in the range of 5–75° (sequence of 0.05°). The recording time for each sample was 5 s. FullProf Suite software (January 2021 version) was applied to process the obtained diffractograms.

3. Results

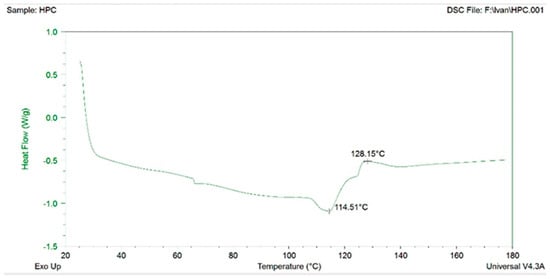

3.1. Sieve Analysis of Components Used for Filaments Production

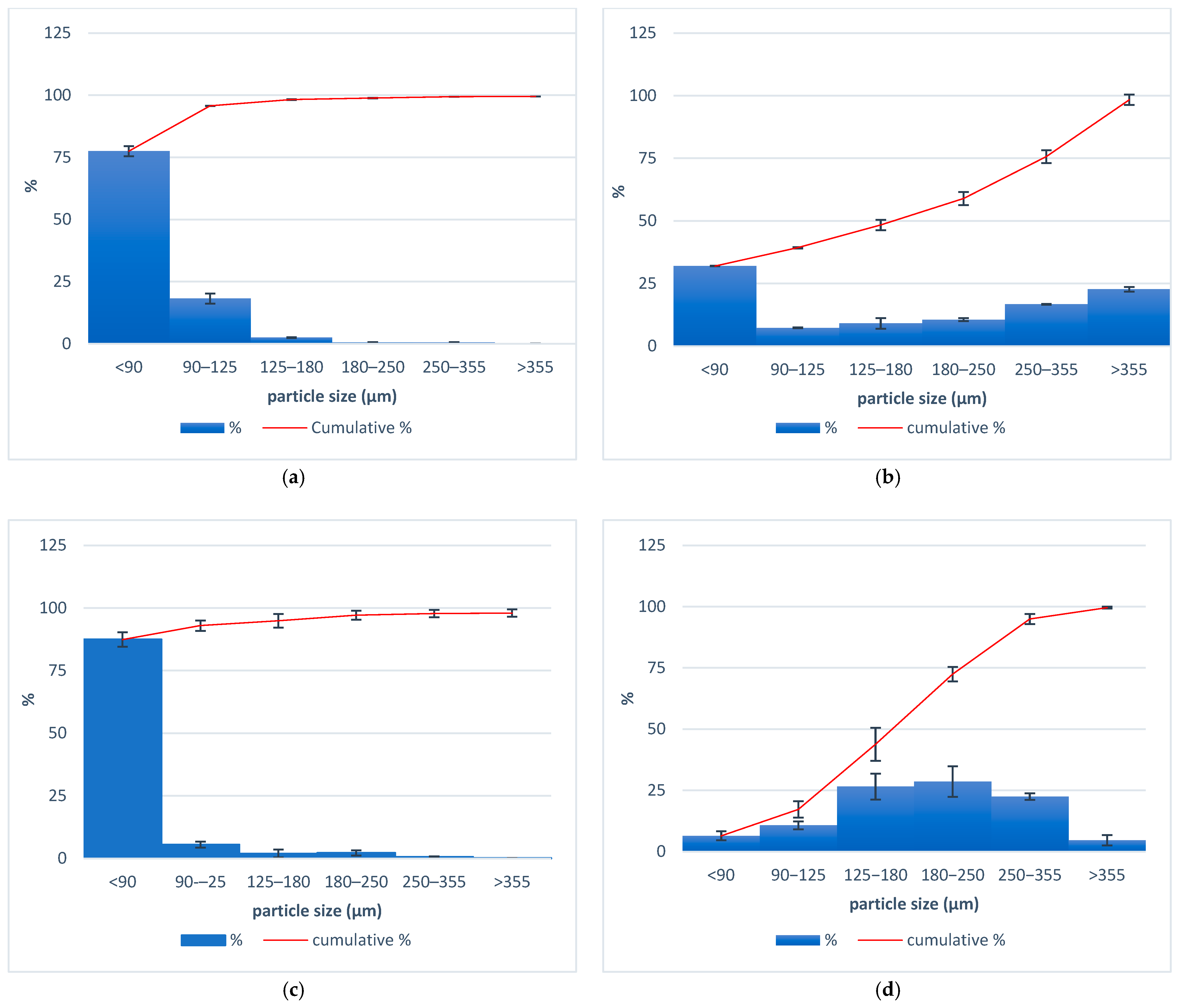

The particle size distribution of the components applied for the tailored filaments production for 3D printing custom-made zinc supplement forms is presented in Figure 2. It is observed that with HPC, HPMC, and ABF, most of the particles were smaller than 90 µm. The average size of zinc oxide particles varied between 180 and 250 µm.

Figure 2.

Particle size distributions for (a) HPMC, (b) HPC, (c) ABF, and (d) zinc oxide.

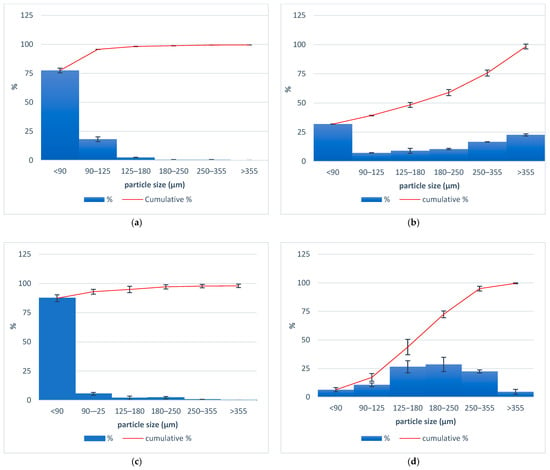

3.2. Melting Point of HPC and HPMC

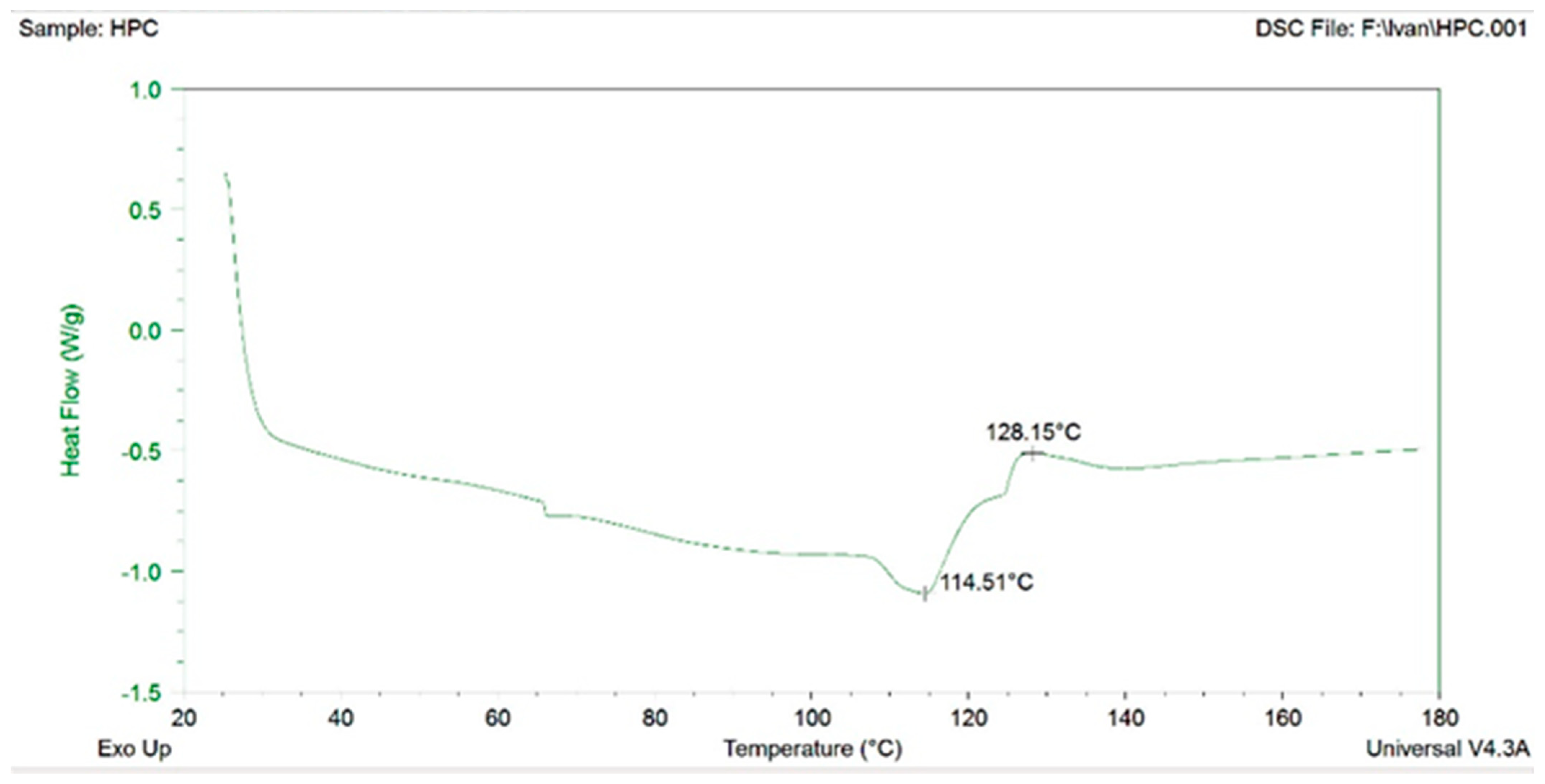

The melting points for HPC and HPMC were 234–236 °C and 224–230 °C, respectively, and were used to evaluate the extrusion temperature of the materials. HPMC was unsuitable for extrusion in the mixture with ABF. Despite the lower melting temperature, HPMC exhibited limited extrudability. The filaments V3 and V4 with HPMC after extrusion varied in diameter and were also heterogeneous and twisted. Thus, HPC was selected as the polymer for filaments production. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) was performed for HPC and the first transition was recorded at 114 °C (Figure 3). The transition temperature of HPC recorded with DSC coincided with an extrusion temperature of 120/110 °C. However, filaments with more favorable features were produced at slightly higher temperatures, 125/115 °C.

Figure 3.

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) for HPC.

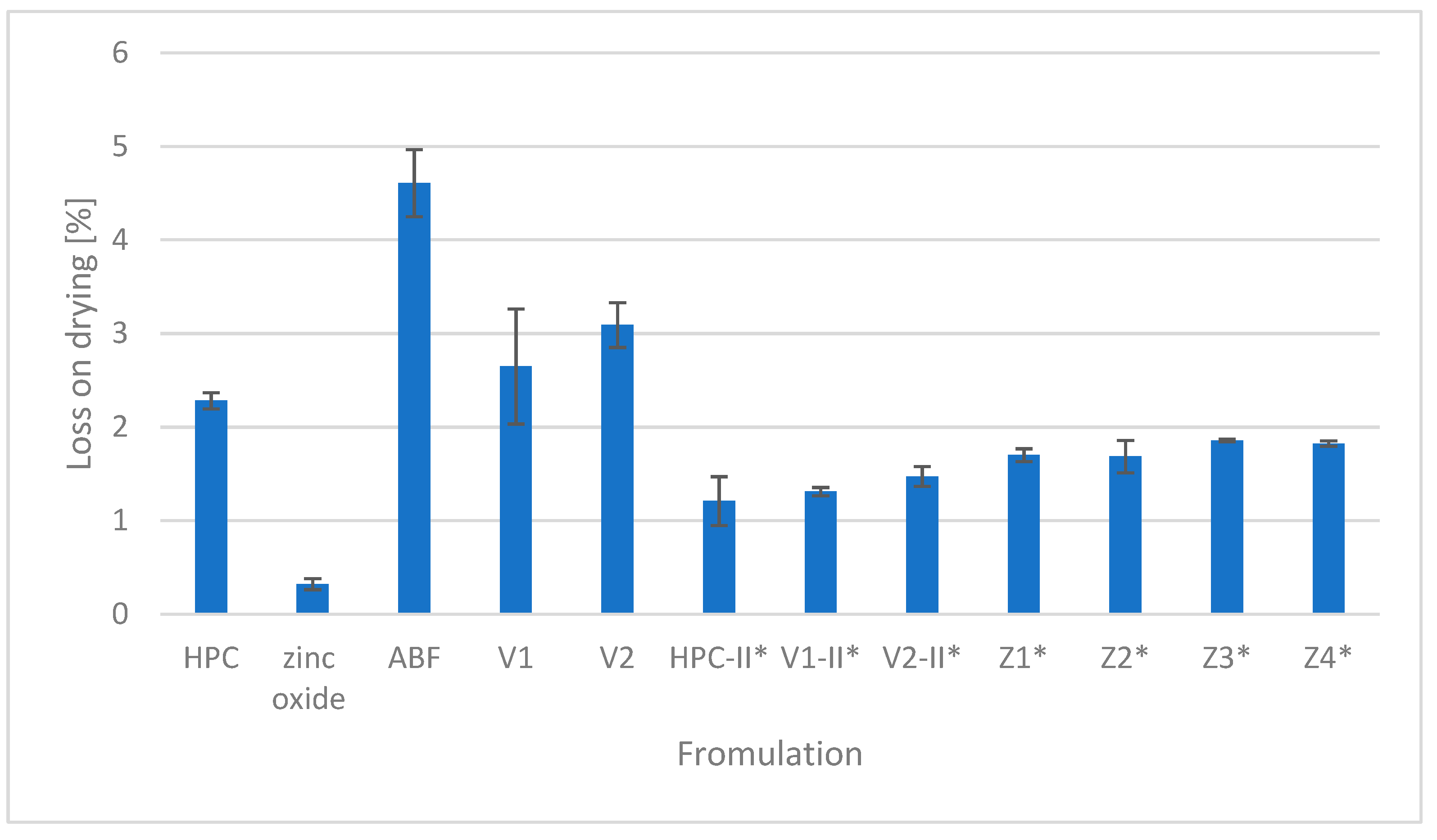

3.3. Loss on Drying

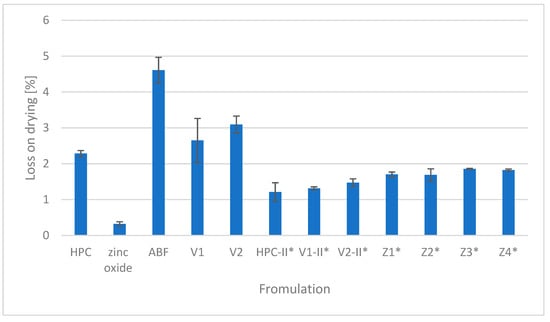

The percentage of the loss of drying of HPC, ZnO, and ABF as components used for tailored filament production as well as the obtained placebo filaments (V1 and V2) and zinc oxide-containing filaments (Z1, Z2, Z3, and Z4) is presented in Figure 4. The highest moisture content was recorded in the second version of the placebo filament (V2) while zinc oxide had the lowest loss on drying.

Figure 4.

Loss on drying. * Samples dried at 40 °C for 24 h prior to HME.

3.4. Filaments Production by Hot-Melt Extrusion

Two placebo and four zinc oxide-containing filaments were produced by hot-melt extrusion. The parameters of the tailored filaments are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Parameters of the filament’s production by hot-melt extrusion.

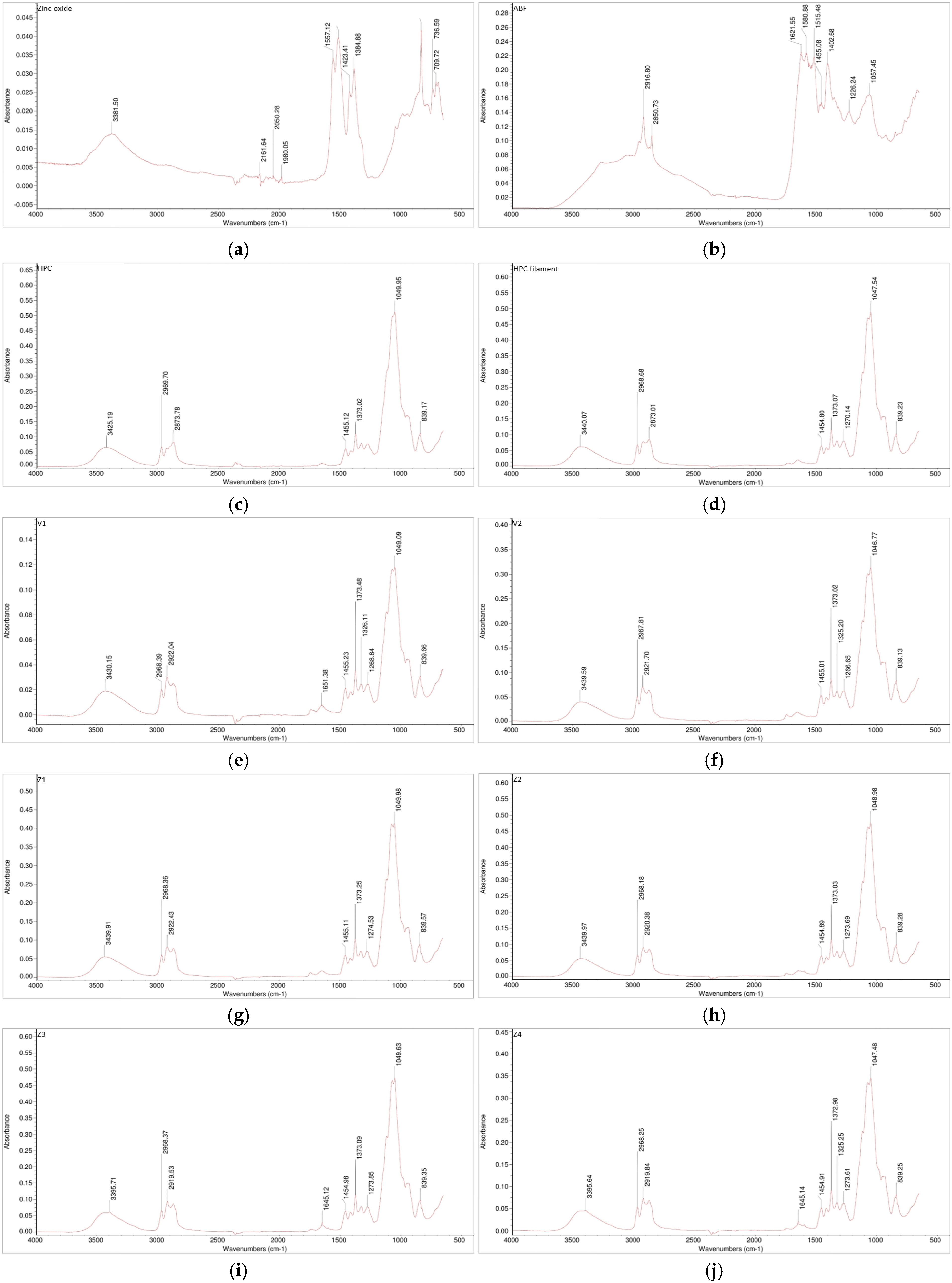

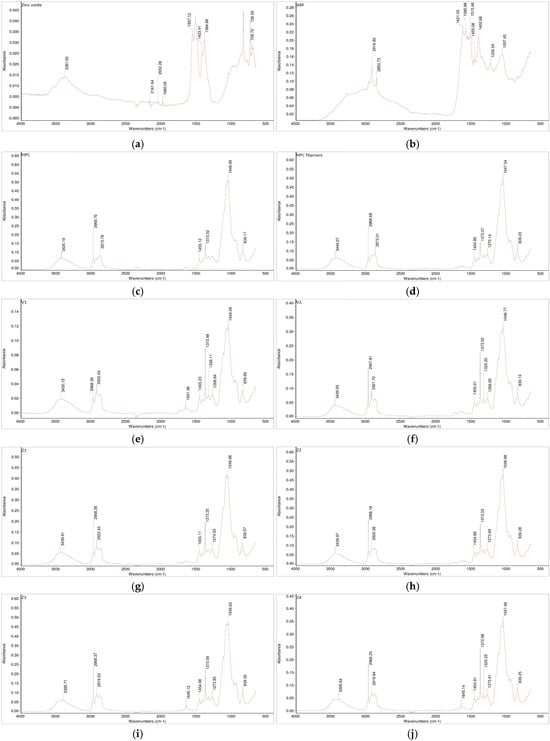

The results in Table 3 indicate that the 10% ABF formulation (V1) did not affect the change in extrusion temperature in comparison to pure HPC, while the 20% ABF formulation (V2) increased the extrusion temperature. The effect of ABF on the extrusion temperature could be attributed to a possible interaction with HPC. However, FTIR analysis indicated no chemical interaction between HPC and ABF, as presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

FTIR spectra of the investigated samples: (a) zinc oxide, (b) ABF, (c) HPC, (d) HPC filament, (e) V1, (f) V2, (g) Z1, (h) Z2, (i) Z3, and (j) Z4.

It can be assumed that the viscosity of the formulation increased after ABF was added to HPC. On the other hand, since the addition of zinc oxide is known to affect the viscosity of the system, it can be presumed that it would also increase the viscosity of the filaments. Therefore, the Z1 formulation with only 5% zinc oxide and HPC required a higher extrusion temperature of 130/125 °C. Yet, when 10% zinc oxide was included in formulation Z2, the extrusion temperature was not affected when compared to formulation Z1 with 5% zinc oxide. Also, when 10% ABF was added to the 5 or 10% zinc oxide formulations with HPC, formulation Z3 and Z4, respectively, the extrusion temperature remained unchanged, as for formulations without ABF with 5 and 10% zinc oxide, i.e., Z1 and Z2, respectively (Table 3).

Each filament was subjected to visual inspection, determining their color, diameter consistency, surface texture, waviness, and minor irregularities. The diameter of each filament was measured on three different randomly chosen spots. The visual appearance of the tailored filaments and their diameters in mm are presented in Table 4. It should be emphasized that the addition of zinc oxide to the mixture with HPC (with or without) led to production of filaments with a smoother surface and smaller diameter (Table 4).

Table 4.

Diameter of the tailored filaments and their visual features.

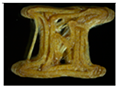

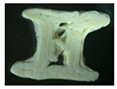

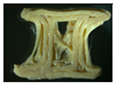

3.5. Three-Dimensional Printing of Custom-Made Zinc Oxide Supplements

Two placebo (V1 and V2) and four zinc oxide-containing supplements were printed using a 3D printer, Ultimaker 3s device (in two different forms: a cylinder (tablet) and a bone. The custom-made forms obtained were photographed using a ZEISS STEMI 508 stereo microscope with an AXIOMCAM Erc 5s camera. The obtained images for all the observed 3D custom-made forms are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Images of the filaments and custom-made 3D-printed forms.

Formulation V1 has similar properties to the pure form of HPC, and the 3D-printed forms were obtained with a printing temperature of 140 °C. However, with V2, the printing temperature was increased to 170 °C, which indicates, as previously suggested, a possible increase in viscosity. Moreover, when visually inspecting the placebo V2, which contains 20% ABF when printed in a custom-made 3D form, it had layers which were more clearly visible. Also, the addition of zinc oxide to the formulation required raising the temperature from 140 °C for pure HPC and V1 (HPC plus 10% ABF) to 145 °C. All zinc oxide-containing formulations were printed under the same conditions and at the same temperature of 145 °C. Visually, the best features of the printed objects were recorded for the formulation Z1, which contained HPC with 5% ZnO and without ABF.

The HPC cylinder and the HPC bone were transparent and homogeneous with smooth surfaces and uniform material distribution. There were no visible deformations or irregularities in the layers. The V1 cylinder and the V1 bone were darker, relatively homogeneous with smooth surfaces, and had uniform material distribution. There were no visible deformations or irregularities in the layers. Both forms, the cylinder and the bone, had similar features to the corresponding 3D shapes obtained only with HPC. The V2 cylinder and the V2 bone were dark brown, heterogeneous, with a rough surface, and had pores in the material. In addition, visible deformations and slight wavy transitions on certain spots in the layers were observed. The printer had difficulty printing the bone shape, thus the movements of the printer were more clearly visible on the bone.

The Z1 cylinder and the Z1 bone were white with a homogeneous surface. Barely visible uneven defects were present in the structure of the 3D-printed forms. The cross-section of the cylinder showed the sealing of a certain number of layers. As a result, the shape of the bone appeared as though it was spilling out. The Z2 cylinder and the Z2 bone were pale-yellow, clearly defined in shape, but the individual layers were spilled. The outer surface was relatively smooth, while visible irregularities, unconnected layers, and deformed bridges in the interior were observed. The Z3 cylinder and the Z3 bone had a more inhomogeneous mesh structure of yellow color with noticeable internal pores in the material. The outer surface was rough, with certain points at which the material was accumulated. The dimensions, as well as the shape, were preserved with visible deformations. Finally, the Z4 cylinder and the Z4 bone had a more homogenous pale-yellow structure with less porosity than both Z3 forms. The outer surface was rough, with irregularly distributed threads of material. The shape was preserved with less deformation.

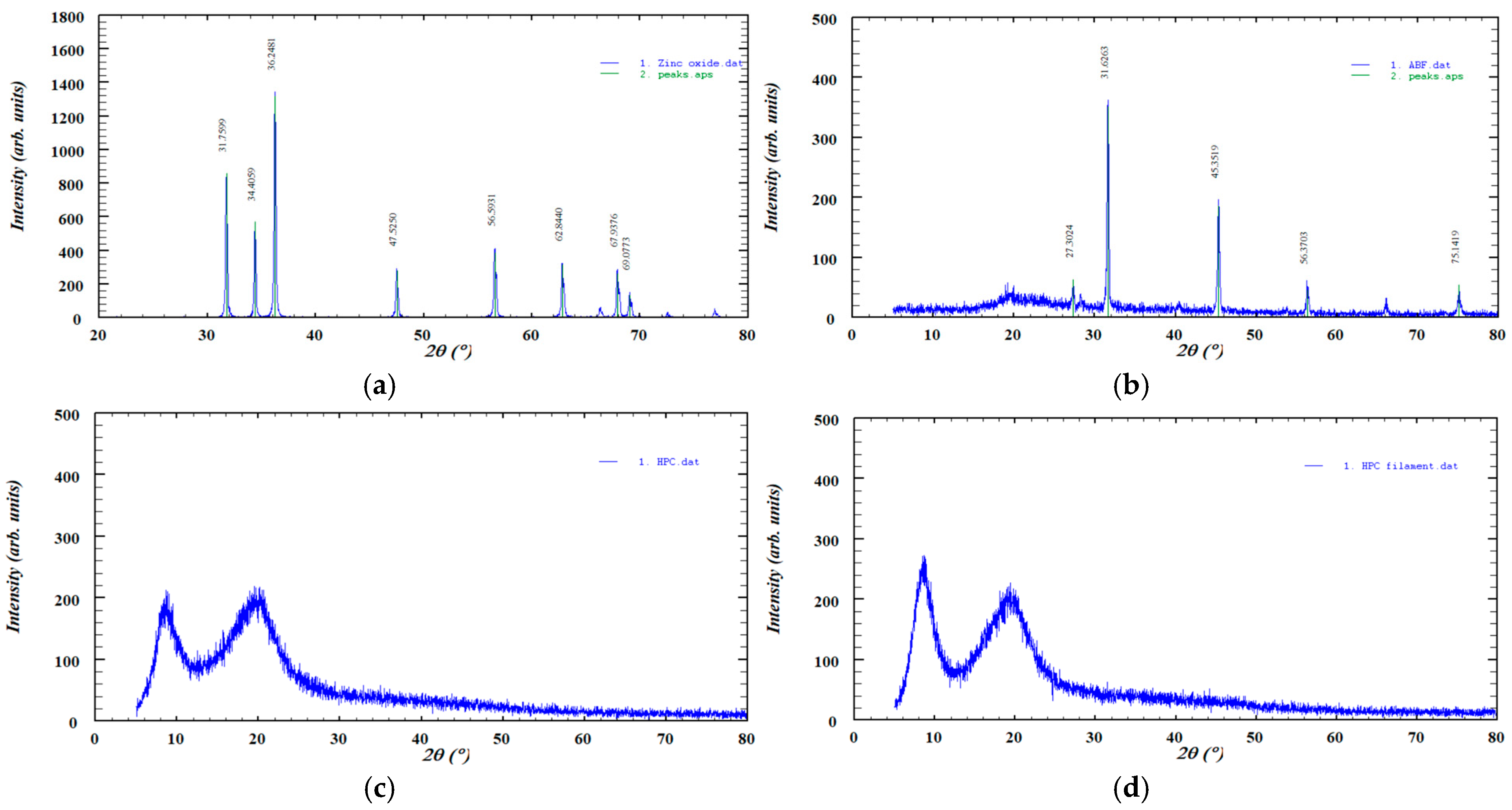

3.6. X-Ray Diffraction of Pure Substances, Tailored Filaments, and Custom-Made 3D Zinc Oxide Supplements

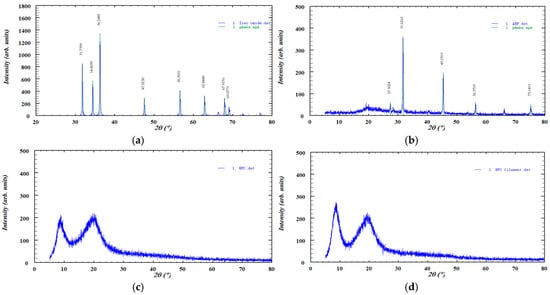

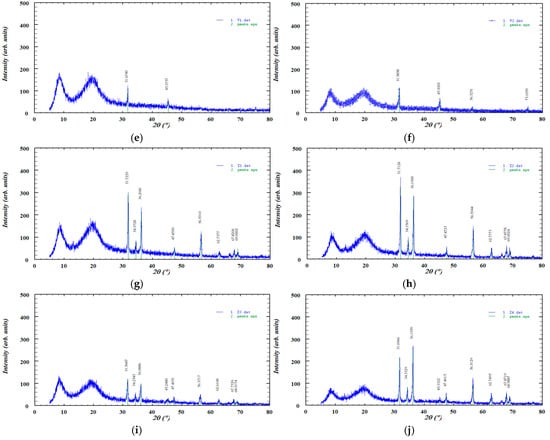

The XRD pattern of pure zinc oxide displayed sharp, high-intensity diffraction peaks, characteristic of its crystalline structure, while ABF exhibited several distinct peaks indicative of its crystalline phases. In contrast, HPC showed two broad, low-intensity peaks typical of a predominantly amorphous material and no significant changes were observed after hot-melt extrusion. These patterns are presented in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

XRD diffractograms of the investigated samples: (a) ZnO, (b) ABF, (c) HPC, (d) HPC filament, (e) V1, (f) V2, (g) Z1, (h) Z2, (i) Z3, and (j) Z4.

4. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first original study to investigate the design of zinc-loaded filaments for the 3D printing of zinc oxide-containing custom-made forms for veterinary practice. The idea of designing customized 3D-printed forms with micronutrients in the form of gummies for the human population has recently been introduced [18] and opened the possibility for an individualized approach not only in therapeutics but also in dietary supplementation. Two 3D-shaped forms, a bone and a cylinder (Figure 1), were designed in this study.

The first challenge in designing the original 3D-printed forms of zinc supplements was the tailoring of adequate filaments. The particle size, drug crystallinity, melting point, thermal stability of both the polymer and active ingredient, molecular interactions between polymer and drug, as well as the hydrophilic/hydrophobic balance and pH responsiveness of the matrix, are critical considerations when selecting materials and assessing the feasibility of a specific formulation [19,20]. Hot-melt extrusion requires homogeneous mixing of the materials: polymers, active pharmaceutical ingredients, and additives like plasticizers, followed by extrusion at elevated temperatures to produce polymeric filaments. The subsequent printing process is typically conducted at temperatures ranging from 150 °C to 230 °C, which are above the glass transition temperature (Tg) of the polymeric materials, to facilitate molecular-level intermixing of the components [21]. Thus, adding a flavor that is stable at higher temperatures and can undergo the hot-melt extrusion without interactions with the polymer is the fundamental step for further decisions in the design.

The polymer hydroxypropyl cellulose (HPC) can effectively convert the crystalline form of the drug into its amorphous form, enhancing dissolution and enabling sustained drug release [22]. The polymer hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (HPMC) acts as a binder, providing structural integrity to the printed dosage form but also, due to its ability to swell, enables a sustained release of drugs [23]. The particle size, or rather the uniformity of the particle size of all components, is important for the uniformity of mixing during extrusion. In the case of a larger difference in particle size, less uniformity of the extrudate may cause possible segregation of the powder in the device. The sizes of the HPC, HPMC, and ABF were predominantly below 90 µm, and the size distribution curve was shifted to the left (Figure 2a–c). For zinc oxide, the particle size distribution was between 180 and 250 µm (Figure 2d). A smaller particle size of the components contributes to the uniform appearance of the filament, without any irregularities. A homogenous material is considered critical for maintaining a consistent filament diameter [24].

The melting point of HPMC and HPC in our research was lower than in the literature [25], for several reasons. Hydroxypropyl cellulose is a nonionic polymer that dissolves in both water and ethanol. Its molecular structure is composed of β-(1 → 4) linked D-glucopyranose units, where the hydroxyl groups located at the C2, C3, and C6 positions of the glucose ring are chemically modified by etherification with hydroxypropyl groups, -CH2CH(OH)CH3 [26]. The molecular chains are arranged randomly, without an ordered structure. This disordered arrangement contributes to the amorphous features of the polymer, which soften gradually as the temperature increases. The molecular weight and degree of substitution affect the melting point as well [27]. Hydroxypropyl methylcellulose is produced by chemically modifying natural cellulose through etherification, where hydroxyl groups in the cellulose are substituted with hydroxypropyl and methyl groups. This modification enhances the cellulose’s solubility, viscosity, film-forming ability, and soothing properties. For HPMC, the degree of substitution indicates the number of methoxy groups attached per repeating unit, while the molar substitution refers to the average number of hydroxypropyl groups per unit. The balance between the methoxy (hydrophobic) and hydroxypropyl (hydrophilic) groups determines the features of HPMC, such as solubility, swelling capacity, and thermal gelation temperature, etc. A higher methoxy content causes a reduction in the number of hydrogens which can donate their electron pair to build intramolecular hydrogen bonds and thus enhances hydrophobic interactions, reduces hydration, swelling, and gel strength by limiting the accessibility of hydrophilic groups [28]. Therefore, the molecule is less stable and melts at lower temperatures even if it has a higher molecular weight. After repeated drying, it is not possible to remove complete moisture from the material, i.e., HPC and HPMC. HPC is more hygroscopic than HPMC due to the free hydroxyl groups [8]. Residual solvents and impurities also lower the melting point, as they act as plasticizers. In addition, they make the amorphous polymer even more disordered [29].

The glass transition temperature (Tg) is a key parameter for amorphous polymers, marking the temperature above which the polymer changes from a hard, glassy state to a soft, rubbery state. When the polymer is below the Tg, it is stiff, brittle, and less flexible. When the temperature exceeds the Tg, the polymer becomes elastic, softer, and capable of deformation [30]. The complex morphological structure of HPC likely contributes to the challenges in the accurate determination of its Tg. The reported Tg values in the literature for HPC vary widely, from 19 °C to up to 124 °C, with some of the literature reporting that the Tg for HPC could not be obtained [31]. In addition, HPC also has a wide extrusion-processing window of >20 °C [32]. We have experimentally determined that the temperature transition for HPC is between 114 and 129 °C (Figure 3), which corresponds to the Tg of 124 °C for HPC reported by Sakellariou et al. [33]. The glass transition and/or melting temperature, the degradation temperature, and the extrusion temperature range for HPMC varies in the literature data as well but with a narrower temperature window [32]. In this study, HPMC was unsuitable for extrusion when mixed with ABF. HPMC is generally a challenging polymer to process by hot-melt extrusion because of its wide glass transition temperature range (160–210 °C), low degradation temperature, and high melt viscosity. These factors often necessitate the use of plasticizers to improve HPMC’s processability. Adding plasticizers on the other hand, can lead to issues such as drug crystallization during storage due to interactions with other additives [34].

Moisture of the components can affect the quality of the filaments formed in the hot-melt extrusion process. The absorbed moisture can evaporate in the process of heating and extrusion, creating voids within the molten material, resulting in surface irregularities and reduced structural integrity of the product. The polymer hydrolysis stimulated by the moisture in the components contributes to the material’s degradation and results in a consequent reduction in the mechanical properties of the filament, such as strength and elasticity. The extrusion process can also be disrupted because wet materials can cause unstable flow followed by nozzle clogging, which makes extrusion demanding and uncontrollable. Finally, water acts as a plasticizer, facilitating active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) recrystallization and compromising structural integrity [35,36]. The loss on drying was 2.28% for hydroxypropyl cellulose, 0.32% for zinc oxide, 2.64 for V1, 3.09% for V2, 1.13% for Z1, 1.61% for Z2, 1.23% for Z3, and 1.73% for Z4 (Figure 4). A moisture content of up to 5% is considered a critical threshold for HPC, as it significantly influences its physical properties. Although HPC has a relatively low affinity for moisture, exceeding this 5% limit results in notable changes in the powder’s behavior [37]. The moisture of all of the ingredients was appropriate.

To test the processability, extrusion was started with optimization of the temperature, screw rotation rate, and variations in the formulation’s composition, to ensure homogeneous mixing and stability of the extrudate. As previously mentioned, HPMC filament had limited processability properties. The filament after extrusion was heterogeneous, tortuous, and with variations in the diameter. Although HPMC (Figure 2a) had smaller particle sizes in comparison to HPC (Figure 2b), the extrusion process was in favor of HPC. Particle size distribution affects a material’s miscibility, agglomeration, and flow properties [38], and can probably influence the characteristics of the obtained filaments. Namely, particles with a smaller size have a larger specific surface area, which can lead to increased cohesive forces, surface-to-surface interactions, and a higher tendency for agglomeration. Larger particle sizes generally enhance flowability because they create more space between particles, allowing them to move past one another more easily [39]. On the contrary, smaller particles add to the poor flowability, which may adversely affect the extrusion process. Therefore, HPMC was not further considered to be an appropriate matrix for tailoring the filaments. On the other hand, HPC was suitable for the filament’s production at an average extrusion speed of 15 revolutions per minute and the lowest temperature of 125 °C (Table 3). The obtained HPC filament was transparent and elastic, with a rough surface and slight wavy transitions at certain points. Variations in diameter were less than 10% (Table 4). The placebo mixture V1 (consisting of 10% ABF and 90% HPC) showed almost identical processability to pure HPC (Table 3), but the filament was brown (Table 4). The placebo V2 formulation containing 20% ABF and 80% HPC was difficult to process. The extrusion temperature for V2 was raised to 140 °C and the speed was increased to 20 revolutions per minute (Table 3). It was estimated that at least 80% HPC is required for the filaments to exhibit satisfactory printability. Taking that into account, 10% of the ABF was selected for further design of zinc-loaded filaments.

The zinc-loaded filaments without ABF, Z1 and Z2, were designed by adding 5% and 10% zinc oxide, respectively, to HPC. Compared to Z1, the obtained Z2 filament was light-yellow with thinned bends at specific points (Table 4 and Table 5). Filaments Z3 and Z4 were a combination of 10% ABF with 5% and 10% zinc oxide added to HPC, respectively. The Z3 filament, as well as the Z2, was characterized by uneven transitions, and thus, varying diameters (Table 4). Surprisingly, the Z4 filament with 10% zinc oxide and ABF had a uniform diameter with no voids or irregularities (Table 4).

All tailored filaments were examined by FTIR to assess whether any chemical interactions occurred between the excipients and incorporated substances during hot-melt extrusion and filament formation. Spectroscopy can be used to obtain real-time insights into the process and filament properties during filament preparation [40]. FTIR analysis became the “golden standard” for the characterization of 3D-printed forms [41,42,43,44]. Its ability to identify functional groups and detect potential molecular interactions or chemical modifications makes it essential for confirming the compatibility and stability of formulation components processed under heat and shear stress.

The FTIR analysis indicated no appearance of new bands in the spectrum, which suggests that there were no formations of new chemical bonds in either the placebo formulations (V1 and V2) or in the zinc-loaded formulations (Z1–Z4) in comparison to the spectrogram of pure HPC (Figure 5). Based on the obtained spectroscopic analysis, no interactions were observed. The absence of additional peaks or significant spectral shifts suggests that the structural integrity of the polymer and additives was preserved.

The combination of HPC with ABF (V1 and V2) as well as the combinations of different fractions of zinc oxide with HPC with or without ABF (Z1–Z4) did not exhibit polymer–additive–supplement interactions. The characteristic peaks corresponding to hydroxyl (–OH), ether (C–O–C), and carbonyl (C=O) stretching vibrations remained unchanged, further indicating that the materials underwent only physical mixing without chemical transformation. This step was fundamental for the further development of 3D-printed forms. Any type of interaction, polymer–additive, polymer–supplement, additive–supplement, may affect the quality of the product as well as the release-time of the API (drug or supplement) [45,46].

This finding is fundamental for further development of 3D-printed forms, as polymer–additive or polymer–supplement interactions could significantly affect filament quality, thermal stability, and ultimately, the release profile of the active substance. Maintaining chemical compatibility ensures predictable mechanical behavior during extrusion and printing, as well as consistent release characteristics of the active ingredient or supplement. Conversely, the formation of new chemical entities could lead to undesired alterations in viscosity, thermal transitions, or dissolution kinetics [47].

FTIR analysis (Figure 5) revealed that pure zinc oxide exhibited low-intensity absorption bands, which are expected for an inorganic oxide. In addition to the characteristic fingerprint region associated with Zn–O lattice vibrations, several additional bands of a similarly low-intensity were observed. The absorptions around ~1400 cm−1 can be attributed to surface-adsorbed carbonate species formed through CO2 interactions with zinc oxide [48], whereas the broad band near ~3400 cm−1 corresponds to adsorbed moisture and surface hydroxyl groups [49]. The FTIR spectrum of the ABF confirmed the presence of a complex mixture of organic compounds. The dominant bands included aliphatic C–H stretching (~2900 cm−1), conjugated C=C stretching (~1620 cm−1), C=C stretching (~1580 cm−1), and C–H bending absorptions at ~1400 and ~1450 cm−1, all characteristic of multi-component flavoring systems [50]. The FTIR spectrum of HPC showed a broad O–H stretching band at 3425 cm−1, together with C–H stretching bands at 2969 and 2874 cm−1 from the hydroxypropyl groups. In the fingerprint region, the absorptions at 1455 and 1373 cm−1 corresponded to CH2 vibrations. The strong band at 1050 cm−1 was attributed to C–O stretching of ether linkages, while the signal at 839 cm−1 reflected C–O deformation and CH2 rocking. These features are characteristic of HPC. Moreover, HPC after extrusion showed a broad-peak small shift from 3425 cm−1 to 3440 cm−1, which can be attributed to changes in hydrogen bonding [51]. Despite this shift, the FTIR spectrum showed no significant differences, indicating that the polymer structure was preserved after the extrusion process. Furthermore, the mixtures, including HPC combined with ABF or ABF and zinc oxide, did not show any additional peaks or significant shifts in existing bands in the FTIR spectra. This observation indicates that the interactions between HPC, ABF, and zinc oxide did not alter the polymer structure or induce chemical changes, confirming the overall stability of the formulations. Overall, these results suggest that the extrusion process and incorporation of additives maintained the integrity of HPC while accommodating the other components without detectable structural modifications.

Therefore, the FTIR results confirm that the selected combination of hydroxypropyl cellulose with ABF (V1 and V2) and the different zinc oxide fractions (Z1–Z4) represents a chemically compatible system. This stability under extrusion conditions supports the suitability of these formulations for subsequent 3D printing and performance testing. The absence of interactions between the polymer, additive, and supplement components provides a strong basis for reliable product reproducibility and controlled release behavior.

The XRD pattern of pure zinc oxide (Figure 6) displayed a series of sharp, high-intensity diffraction peaks characteristic of its crystalline wurtzite structure. The most prominent reflections were observed at approximately 31.76°, 34.41°, 36.25°, 47.52°, 56.59°, 62.84°, 67.94°, and 69.07° (2θ), corresponding to the (100), (002), (101), (102), (110), (103), (112), and (201) lattice planes, respectively. The diffractogram also showed reflections corresponding to the (200), (004), and (202) lattice planes, although these peaks appeared with lower intensity. The presence of narrow and well-defined peaks confirms the high crystallinity of the zinc oxide sample, with no detectable secondary phases or impurities [52]. The diffractogram of pure ABF exhibits several distinct diffraction peaks at 2θ values of approximately 27.30°, 31.62°, 45.35°, 56.37°, and 75.14°, indicating the presence of crystalline phases within the sample. The highest intensity peak appears at 31.60°, suggesting a dominant crystalline component. The XRD diffractogram of HPC displayed the characteristic broad amorphous halo described in the literature. No new diffraction peaks or intensity changes were observed after extrusion, indicating that the process did not induce crystallization. This finding is consistent with the FTIR analysis, which similarly showed no significant spectral shifts or the appearance of new absorption bands. The XRD pattern of HPC exhibited two broad, low-intensity diffraction peaks, indicating a low degree of structural ordering, which is consistent with previously reported data [51]. Importantly, the diffractogram remained essentially unchanged after HME, suggesting that the processing did not alter the existing level of ordering. This observation is supported by the FTIR analysis, which showed no significant spectral shifts or the appearance of new absorption bands. The XRD patterns of the formulations (Z1–Z4) showed a reduction in the intensity of the sharp diffraction peaks of zinc oxide, indicating partial amorphization of the material [53]. This decrease in peak intensity was more pronounced in formulations containing lower amounts of zinc oxide. A similar effect was observed for ABF (V1 and V2), where the crystalline peaks also became less intense upon incorporation into the formulations, suggesting a partial loss of crystallinity.

The printing temperature in this research was 140/145 °C, which was higher in comparison to the extrusion temperature. This setting is typical, as the printing temperature usually is higher than the temperature used in hot-melt extrusion. The minimum temperature for melting or deposition must be carefully optimized to avoid degradation of both the polymers and the active pharmaceutical ingredients. Polymer viscosity is a key factor in setting the printing temperature, as the molten polymer must flow smoothly through the narrow nozzle of the FDM 3D printer before being deposited onto the build plate [54]. The porosity of a dosage form is directly influenced by its infill density. Lower infill percentages result in higher porosity, increased surface area, and reduced mechanical strength. The infill density for the printed forms was 25%, which should result in an adequate ability to dissolve since it is reported that tablets printed with 20% infill density dissolve at a higher rate in comparison to those printed with 100% infill density [55]. The infill pattern determines the internal structure of the printed dosage form and varies with different fill densities. Like the infill density, the choice of infill pattern can influence mechanical strength and in vitro drug release profiles. Most commercially available 3D printers offer standard infill patterns such as line, diamond, concentric, hexagonal, shark fill, and grid designs [54]. In the 3D printing process, a triangle pattern for the cylinder and a zig-zag pattern for the bone were applied, which guaranteed faster disintegration. The printing velocity was 25 mm/s, which is rather slow, but it is reported that high printing speeds may produce low-quality dosage forms [56]. Formulations that are acceptable and suitable for dogs can improve owner compliance and, consequently, therapeutic outcomes. Due to the bitter taste of APIs and the lack of appropriately dosed medications, administering drugs to dogs can be challenging. FDM 3D printing, with its ability to create dosage forms customized in dose and shape, offers significant advantages in producing formulations specifically designed for canine patients. Various shapes are printed for pediatric populations, including donut-like [57] or candy-like [58], while veterinary practice, to the best of our knowledge, lacks variations [59,60,61]. Thus, the cylinder and bone proposed in this study are custom-made.

The best outer and inner appearance of the 3D-printed forms with zinc oxide loading (Z1–Z4) was observed for the Z1 formulation (Table 5). However, the absence of ABF may affect compliance due to the taste of the formulation or the lack of it. On the other hand, if ABF is observed as a mandatory additive in the formulation, Z4 presents enhanced outer and inner appearance in comparison to Z3 (Table 5). A pharmaceutical flavor should provide effective palatability at low concentrations. If the active ingredient has a very bitter taste, it may require additional taste masking, but usually the amount of palatability-enhancing flavor is a small fraction of the total weight of the formulation. ABF is one of the standardly used additives to enhance palatability in pharmaceutical formulations for dogs [62]. Based on the features presented in Table 5, the Z4 formulation has the highest potential for further development of zinc-loaded custom-made 3D-printed forms for supplementation in veterinary practice.

Finally, the release of an active pharmaceutical ingredient such as ZnO from HPC in water is primarily governed by its dissolution and gelation properties, where the rate of release depends on the formation of a hydrated gel layer [63]. Zinc from HPC can be released in water through diffusion and erosion mechanisms, influenced by factors like the HPC’s viscosity, the drug-to-polymer ratio, and the presence of other polymers. The release process is affected by the formation of pores in the polymer film as water penetrates [64]. However, as it is expected for the animal to gnaw and to seize with their teeth the 3D pharmaceutical forms, the integrity of the forms will be compromised. Thus, easier water penetration due to grinding in the animal’s mouth is expected.

5. Conclusions

Hydroxypropyl cellulose was found to be a suitable polymer for hot-melt extrusion, whereas hydroxypropyl methylcellulose showed inadequate extrudability in formulations containing ABF. Adding 10% ABF to HPC did not significantly affect the extrusion temperature. However, increasing the ABF concentration to 20% required a higher extrusion temperature and an increased extruder turnover rate. Placebo filament V1, composed of HPC with 10% ABF, exhibited similar properties to pure HPC when extruded at 125 °C, allowing for the successful 3D printing of custom shapes. At higher ABF levels, the extrusion temperature had to be raised to 140 °C, resulting in more pronounced layer lines during printing, likely due to increased viscosity, as FTIR analysis showed no chemical interactions.

The addition of zinc oxide improved filament surface smoothness regardless of the presence of ABF. ZnO as an active component in the formulations also enhanced the morphological characteristics of the filaments. Extrusion with 5% ZnO required a slightly higher temperature (130/125 °C), while increasing ZnO content to 10% had little impact. Formulations combining zinc oxide and 10% ABF showed no difference in extrusion temperature compared to those without flavoring. Future research should explore optimizing formulations with various additives to further improve filament processability and the mechanical properties of 3D-printed objects.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.L.-P., N.G. and N.M.; methodology, S.P. and I.B.; software, I.B.; validation, M.L.-P., N.T. and N.M.; formal analysis, A.V. and I.B.; investigation, I.B. and A.V.; resources, M.L.-P.; data curation, I.B. and A.V.; writing—original draft preparation, N.G. and N.M.; writing—review and editing, M.L.-P., N.M., S.P. and N.G.; visualization, N.T. and S.P.; supervision, M.L.-P. and S.P.; project administration, N.T. and N.M.; funding acquisition, M.L.-P. and N.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technological Development, Republic of Serbia (grant: 451-03-136/2025-03/200114).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Pet Flavors Inc. (Melbourne, FL, USA) for kindly providing the artificial beef flavoring used in this study. The authors acknowledge the help of Srđan Rakić, Department of Physics, Faculty of Science, University of Novi Sad, for recording the X-ray diffractograms.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of this study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ABF | artificial beef flavoring |

| DSC | differential scanning calorimetry |

| FDM | fused deposition modeling |

| FTIR | Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy |

| HME | hot-melt extrusion |

| HPC | hydroxypropyl cellulose |

| HPMC | hydroxypropyl methylcellulose |

| Tg | glass transition temperature |

References

- Jonovski, J.C.; Bacon, E.K.; Velie, B.D. Towards precision pain management in veterinary practice: Opportunities and barriers. Front. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 1658765, Erratum in Front. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 1687598. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd, K.C.; Khanna, C.; Hendricks, W.; Trent, J.; Kotlikoff, M. Precision medicine: An opportunity for a paradigm shift in veterinary medicine. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2016, 248, 45–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thamm, D.H.; Gustafson, D.L. Drug dose and drug choice: Optimizing medical therapy for veterinary cancer. Vet. Comp. Oncol. 2020, 18, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Chen, X.; Han, X.; Hong, X.; Li, X.; Zhang, H.; Li, M.; Wang, Z.; Zheng, A. A Review of 3D Printing Technology in Pharmaceutics: Technology and Applications, Now and Future. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano-Vicent, A.; Tambuwala, M.M.; Hassan, S.S.; Barh, D.; Aljabali, A.A.A.; Birkett, M.; Arjunan, A.; Serrano-Aroca, Á. Fused deposition modelling: Current status, methodology, applications and future prospects. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 47, 102378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, G.M.; Cardoso, P.H.N.; da Silva, E.M.E.; Tavares, G.F.; Olivier, N.C.; Faia, P.M.; Araújo, E.S.; Silva, F.S. FDM 3D Printing Filaments with pH-Dependent Solubility: Preparation, Characterization and In Vitro Release Kinetics. Processes 2024, 12, 2916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arafat, B.; Qinna, N.; Cieszynska, M.; Forbes, R.; Alhnan, M. Tailored on-demand anti-coagulant dosing: An in vitro and in vivo evaluation of 3D printed purpose-designed oral dosage forms. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2018, 128, 282–289. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, N.G.; Serajuddin, A.T.M. Improving drug release rate, drug-polymer miscibility, printability and processability of FDM 3D-printed tablets by weak acid-base interaction. Int. J. Pharm. 2023, 632, 122542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishath, F.; Mamatha, T.; Qureshi, Q.H.; Anitha, N.; Rao, J.V. Drug-excipient interaction and its importance in dosage form development. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2011, 1, 66–71. [Google Scholar]

- Nasereddin, J.M.; Wellner, N.; Alhijjaj, M.; Belton, P.; Qi, S. Development of a Simple Mechanical Screening Method for Predicting the Feedability of a Pharmaceutical FDM 3D Printing Filament. Pharm. Res. 2018, 35, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, A.M.; Guedes, M.; Matos, E.; Pinto, E.; Almeida, A.A.; Segundo, M.A.; Correia, A.; Vilanova, M.; Fonseca, A.J.M.; Cabrita, A.R.J. Effect of Zinc Source and Exogenous Enzymes Supplementation on Zinc Status in Dogs Fed High Phytate Diets. Animals 2020, 10, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombini, S.; Dunstan, R.W. Zinc-responsive dermatosis in northern-breed dogs: 17 cases (1990–1996). J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 1997, 211, 451–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyanes, Á.; Chang, H.; Sedough, D.; Hatton, G.; Wang, J.; Buanz, A.; Gaisford, S.; Basit, A.W. Fabrication of controlled-release budesonide tablets via desktop (FDM) 3D printing. Int. J. Pharm. 2015, 496, 414–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brambilla, C.R.M.; Okafor-Muo, O.L.; Hassanin, H.; ElShaer, A. 3DP Printing of Oral Solid Formulations: A Systematic Review. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wojnarowska, W.; Najowicz, J.; Piecuch, T.; Sochacki, M.; Pijanka, D.; Trybulec, J.; Miechowicz, S. Animal orthosis fabrication with additive manufacturing—A case study of custom orthosis for chicken. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2021, 28, 824–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, A.; Huarcaya, V.; Acuña, Í.; Marcos, G.; Ccama, G.; Ochoa, E.; Molina, A.R. Additive Manufacturing of a Customized Printed Ankle–Foot Orthosis: Design, Manufacturing, and Mechanical Evaluation. Eng. Proc. 2025, 83, 24. [Google Scholar]

- European Pharmacopoeia, 11th ed.; (Ph. Eur. 11); European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines & Health Care, Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2022.

- Herrada-Manchón, H.; Rodríguez-González, D.; Alejandro Fernández, M.; Suñé-Pou, M.; Pérez-Lozano, P.; García-Montoya, E.; Aguilar, E. 3D printed gummies: Personalized drug dosage in a safe and appealing way. Int. J. Pharm. 2020, 587, 119687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, P.H.N.; Araújo, E.S. An Approach to 3D Printing Techniques, Polymer Materials, and Their Applications in the Production of Drug Delivery Systems. Compounds 2024, 4, 71–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azad, M.A.; Olawuni, D.; Kimbell, G.; Badruddoza, A.Z.M.; Hossain, M.S.; Sultana, T. Polymers for Extrusion-Based 3D Printing of Pharmaceuticals: A Holistic Materials–Process Perspective. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karalia, D.; Siamidi, A.; Karalis, V.; Vlachou, M. 3D-Printed Oral Dosage Forms: Mechanical Properties, Computational Approaches and Applications. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, D.K.; Maniruzzaman, M.; Nokhodchi, A. Development and Optimisation of Novel Polymeric Compositions for Sustained Release Theophylline Caplets (PrintCap) via FDM 3D Printing. Polymers 2020, 12, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Yang, W.; Vo, A.Q.; Feng, X.; Ye, X.; Kim, D.W.; Repka, M.A. Hydroxypropyl methylcellulose-based controlled release dosage by melt extrusion and 3D printing: Structure and drug release correlation. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 177, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponsar, H.; Wiedey, R.; Quodbach, J. Hot-Melt Extrusion Process Fluctuations and Their Impact on Critical Quality Attributes of Filaments and 3D-Printed Dosage Forms. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowe, R.C.; Sheskey, P.J.; Quinn, M.E. (Eds.) Handbook of Pharmaceutical Excipients, 9th ed.; Pharmaceutical Press: London, UK, 2020; pp. 317–322. [Google Scholar]

- Cholakova, D.; Tsvetkova, K.; Yordanova, V.; Rusanova, K.; Denkov, N.; Tcholakova, S. Hydroxypropyl Cellulose Polymers as Efficient Emulsion Stabilizers: The Effect of Molecular Weight and Overlap Concentration. Gels 2025, 11, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarode, A.; Wang, P.; Cote, C.; Worthen, D.R. Low-viscosity hydroxypropylcellulose (HPC) grades SL and SSL: Versatile pharmaceutical polymers for dissolution enhancement, controlled release, and pharmaceutical processing. AAPS PharmSciTech 2013, 14, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlad, R.-A.; Pintea, A.; Pintea, C.; Rédai, E.-M.; Antonoaea, P.; Bîrsan, M.; Ciurba, A. Hydroxypropyl Methylcellulose—A Key Excipient in Pharmaceutical Drug Delivery Systems. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batra, A.; Yang, F.; Kogan, M.; Sosnowik, A.; Usher, C.; Oldham, E.W.; Chen, N.; Lawal, K.; Bi, Y.; Dürig, T. Comparison of Hydroxypropylcellulose and Hot-Melt Extrudable Hypromellose in Twin-Screw Melt Granulation of Metformin Hydrochloride: Effect of Rheological Properties of Polymer on Melt Granulation and Granule Properties. Macromol 2022, 2, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picker-Freyer, K.M.; Dürig, T. Physical mechanical and tablet formation properties of hydroxypropylcellulose: In pure form and in mixtures. AAPS PharmSciTech 2007, 8, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakimets, I.; Wellner, N.; Smith, A.C.; Wilson, R.H.; Farhat, I.; Mitchell, J. Effect of water content on the fracture behaviour of hydroxypropyl cellulose films studied by the essential work of fracture method. Mech. Mater. 2007, 39, 500–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaFountaine, J.S.; McGinity, J.W.; Williams, R.O., 3rd. Challenges and Strategies in Thermal Processing of Amorphous Solid Dispersions: A Review. AAPS PharmSciTech 2016, 17, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakellariou, P.; Rowe, R.C.; White, E.F.T. The thermomechanical properties and glass transition temperatures of some cellulose derivatives used in film coating. Int. J. Pharm. 1985, 27, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, E.; Islam, M.T.; Goodwin, D.J.; Megarry, A.J.; Halbert, G.W.; Florence, A.J.; Robertson, J. Development of a hot-melt extrusion (HME) process to produce drug loaded Affinisol™ 15LV filaments for fused filament fabrication (FFF) 3D printing. Addit. Manuf. 2019, 29, 100776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuther, M.; Rollet, N.; Debeaufort, F.; Chambin, O. Orodispersible films prepared by hot-melt extrusion versus solvent casting. Int. J. Pharm. 2025, 675, 125536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prodduturi, S.; Manek, R.V.; Kolling, W.M.; Stodghill, S.P.; Repka, M.A. Water vapor sorption of hot-melt extruded hydroxypropyl cellulose films: Effect on physico-mechanical properties, release characteristics, and stability. J. Pharm. Sci. 2004, 93, 3047–3056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouter, A.; Briens, L. The effect of moisture on the flowability of pharmaceutical excipients. AAPS PharmSciTech 2014, 15, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira, A.Z.A. Hydroxypropylcellulose Controlled Release Tablet Matrix Prepared by Wet Granulation: Effect of Powder Properties and Polymer Composition. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2009, 52, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albornoz-Palma, G.; Ching, D.; Andrade, A.; Henríquez-Gallegos, S.; Teixeira Mendonça, R.; Pereira, M. Relationships between Size Distribution, Morphological Characteristics, and Viscosity of Cellulose Nanofibril Dispersions. Polymers 2022, 14, 3843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, G.M.; Billa, N. Solid Dispersion Formulations by FDM 3D Printing—A Review. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borș, A.I. Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy Analysis of 3D-Printed Dental Resins Reinforced with Yttria-Stabilized Zirconia Nanoparticles. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, Y.C.; Ong, J.J.; Alfassam, H.; Díaz-Torres, E.; Goyanes, A.; Williams, G.R.; Basit, A.W. Fabrication of 3D printed mutable drug delivery devices: A comparative study of volumetric and digital light processing printing. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2025, 15, 1595–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štaffová, M.; Ondreáš, F.; Svatík, J.; Zbončák, M.; Jančář, J.; Lepcio, P. 3D printing and post-curing optimization of photopolymerized structures: Basic concepts and effective tools for improved thermomechanical properties. Polym. Test. 2022, 108, 107499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- V-Niño, E.D.; Lonne, Q.; Díaz Lantada, A.; Mejía-Ospino, E.; Estupiñán Durán, H.A.; Cabanzo Hernández, R.; Ramírez-Caballero, G.; Endrino, J.L. Physical and Chemical Properties Characterization of 3D-Printed Substrates Loaded with Copper-Nickel Nanowires. Polymers 2020, 12, 2680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhindo, D.; Elkanayati, R.; Srinivasan, P.; Repka, M.A.; Ashour, E.A. Recent Advances in the Applications of Additive Manufacturing (3D Printing) in Drug Delivery: A Comprehensive Review. AAPS PharmSciTech 2023, 24, 57, Erratum in AAPS PharmSciTech 2023, 24, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasieczna-Patkowska, S.; Cichy, M.; Flieger, J. Application of Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy in Characterization of Green Synthesized Nanoparticles. Molecules 2025, 30, 684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plamadiala, I.; Croitoru, C.; Pop, M.A.; Roata, I.C. Enhancing Polylactic Acid (PLA) Performance: A Review of Additives in Fused Deposition Modelling (FDM) Filaments. Polymers 2025, 17, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Etim, U.J.; Zhang, C.; Amirav, L.; Zhong, Z. CO2 Activation and Hydrogenation on Cu-ZnO/Al2O3 Nanorod Catalysts: An In Situ FTIR Study. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 2527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsiao, K.-Y.; Chung, R.-J.; Chang, P.-P.; Tsai, T.-H. Identification of Hydroxyl and Polysiloxane Compounds via Infrared Absorption Spectroscopy with Targeted Noise Analysis. Polymers 2025, 17, 1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afolabi, H.K.; Mudalip, S.K.A.; Alara, O.R. Microwave-assisted extraction and characterization of fatty acid from eel fish (Monopterus albus). Beni-Suef Univ. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2018, 7, 465–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.I.; Biliuta, G.; Macsim, A.-M.; Dinu, M.V.; Coseri, S. Chemistry of Hydroxypropyl Cellulose Oxidized by Two Selective Oxidants. Polymers 2023, 15, 3930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spoială, A.; Ilie, C.-I.; Trușcă, R.-D.; Oprea, O.-C.; Surdu, V.-A.; Vasile, B.Ș.; Ficai, A.; Ficai, D.; Andronescu, E.; Dițu, L.-M. Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles for Water Purification. Materials 2021, 14, 4747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorović, N.; Panić Čanji, J.; Pavlić, B.; Popović, S.; Ristić, I.; Rakić, S.; Rajšić, I.; Vukmirović, S.; Srđenović Čonić, B.S.; Milijašević, B.; et al. Supercritical fluid technology as a strategy for nifedipine solid dispersions formulation: In vitro and in vivo evaluation. Int. J. Pharm. 2024, 649, 123634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumpa, N.; Butreddy, A.; Wang, H.; Komanduri, N.; Bandari, S.; Repka, M.A. 3D printing in personalized drug delivery: An overview of hot-melt extrusion-based fused deposition modeling. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 600, 120501. [Google Scholar]

- Goyanes, A.; Fina, F.; Martorana, A.; Sedough, D.; Gaisford, S.; Basit, A.W. Development of modified release 3D printed tablets (printlets) with pharmaceutical excipients using additive manufacturing. Int. J. Pharm. 2017, 527, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamer, M.S.; Temiz, S.; Yaykaşlı, H.; Kaya, A.; Akay, O. Effect of printing speed on fdm 3d-printed pla samples produced using different two printers. Int. J. 3D Print. Technol. Digit. Ind. 2022, 6, 438–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Dumpa, N.; Bandari, S.; Durig, T.; Repka, M.A. Fabrication of Taste-Masked Donut-Shaped Tablets Via Fused Filament Fabrication 3D Printing Paired with Hot-Melt Extrusion Techniques. AAPS PharmSciTech 2020, 21, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scoutaris, N.; Ross, S.A.; Douroumis, D. 3D Printed “Starmix” Drug Loaded Dosage Forms for Paediatric Applications. Pharm. Res. 2018, 35, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathiyalagan, R.; Westerlund, M.; Mahran, A.; Altunay, R.; Suuronen, J.; Palo, M.; Nyman, J.O.; Immonen, E.; Rosenholm, J.M.; Monaco, E.; et al. 3D printing of tailored veterinary dual-release tablets: A semi-solid extrusion approach for metoclopramide. RSC Pharm. 2024, 2, 413–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, L.; Peña, J.F.; Palma, S.D.; Real, J.P.; Cotabarren, I. Design and production of 3D printed oral capsular devices for the modified release of urea in ruminants. Int. J. Pharm. 2022, 628, 122353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjöholm, E.; Mathiyalagan, R.; Rajan Prakash, D.; Lindfors, L.; Wang, Q.; Wang, X.; Ojala, S.; Sandler, N. 3D-Printed Veterinary Dosage Forms—A Comparative Study of Three Semi-Solid Extrusion 3D Printers. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thombre, A.G. Oral delivery of medications to companion animals: Palatability considerations. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2004, 56, 1399–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremer, G.; Danthine, S.; Van Hoed, V.; Dombree, A.; Laveaux, A.S.; Damblon, C.; Karoui, R.; Blecker, C. Variability in the substitution pattern of hydroxypropyl cellulose affects its physico-chemical properties. Heliyon 2023, 9, e13604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Yang, G.; Chu, X.; Gao, C.; Wang, Y.; Gong, W.; Li, Z.; Yang, Y.; Yang, M.; Gao, C. Polymer Distribution and Mechanism Conversion in Multiple Media of Phase-Separated Controlled-Release Film-Coating. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).