Exploring Factors Affecting the Adoption of IoT in Healthcare: A Systematic Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

Previous Empirical Studies

3. Methodology

3.1. Planning Phase

- -

- To explore the factors affecting the implementation of IoT;

- -

- To clarify academic research trends in the field of IoT in healthcare;

- -

- To understand the role of cybersecurity and its impact on IoT within healthcare.

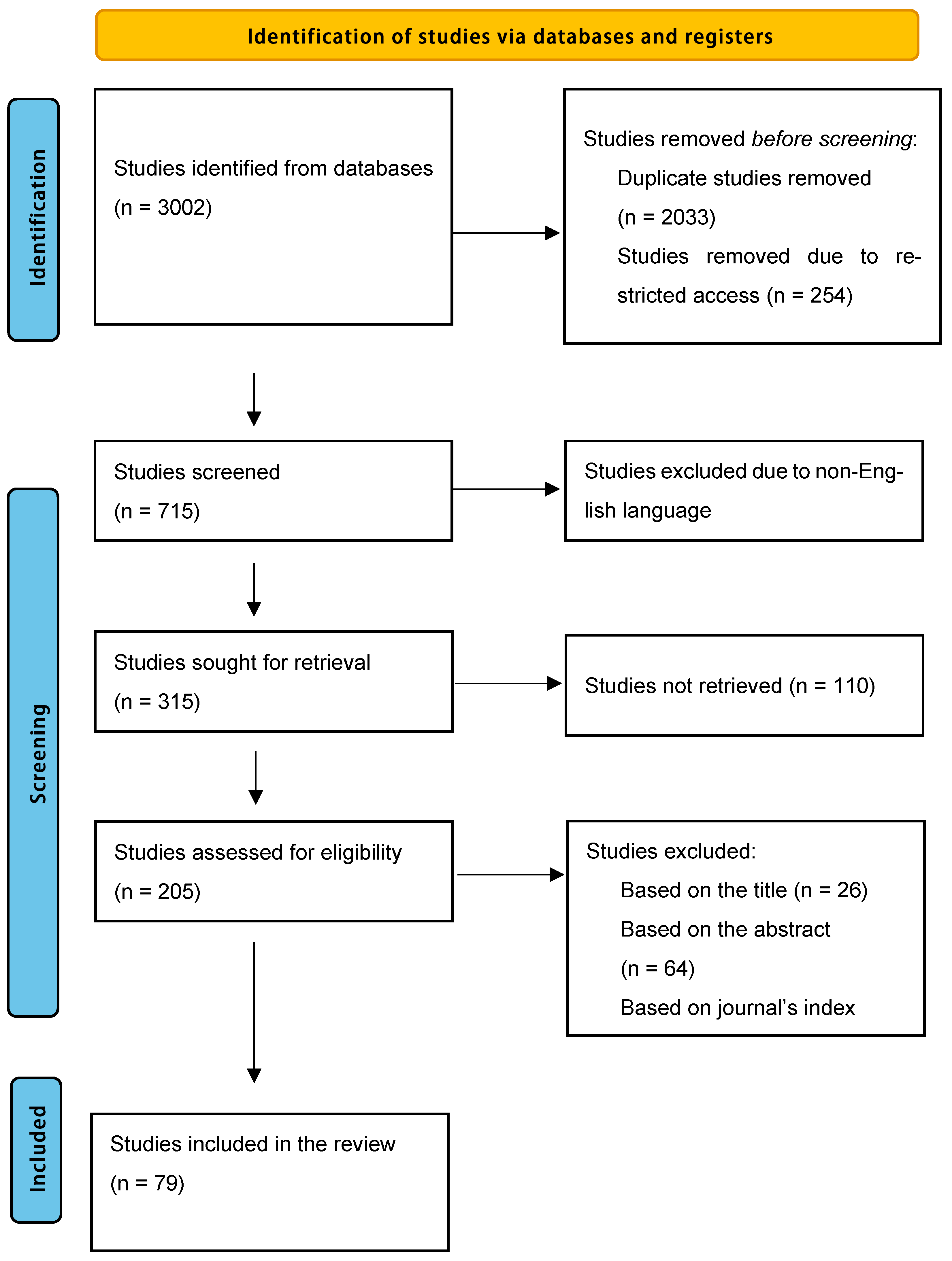

3.2. Selection Phase

3.3. Extraction Phase (PRISMA Flow Diagram)

3.4. Execution Phase (Results)

4. Findings/Results

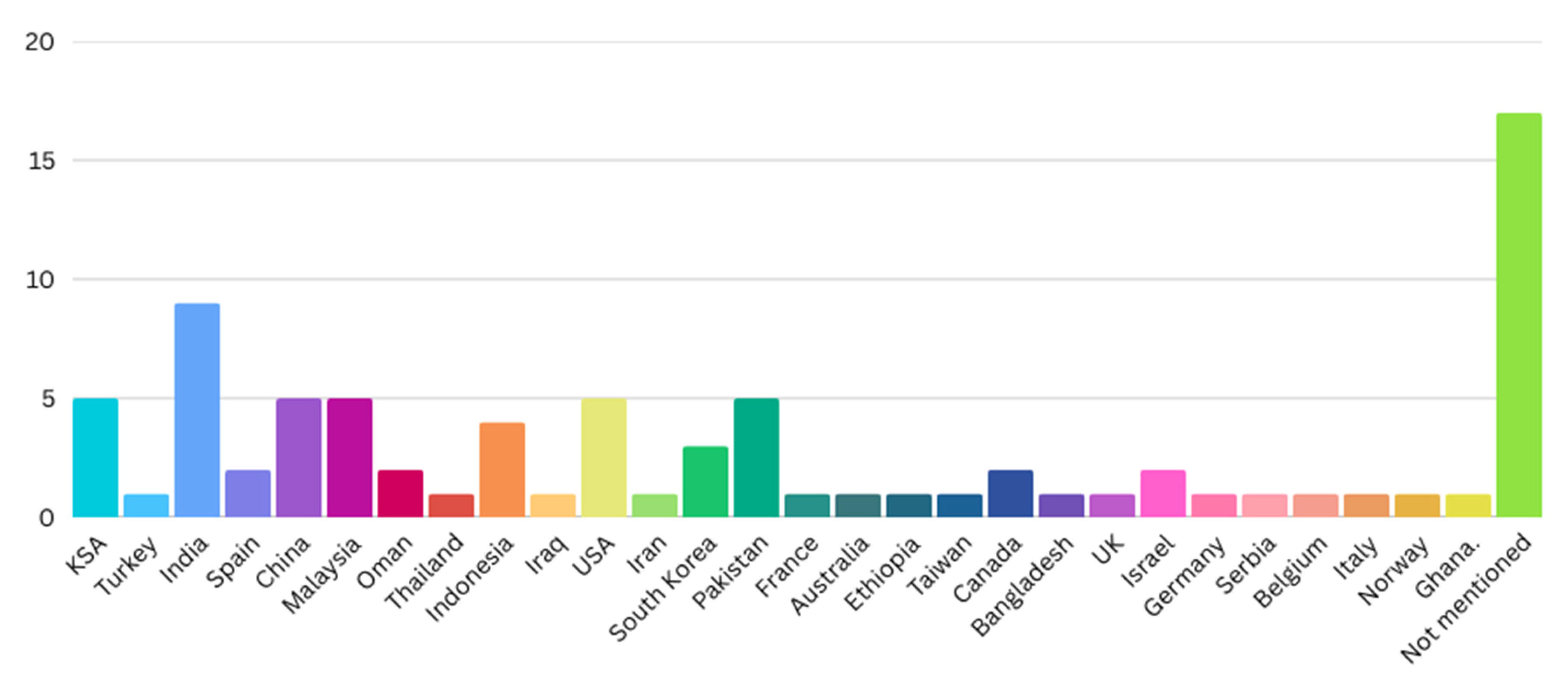

4.1. Countries Where Studies Took Place

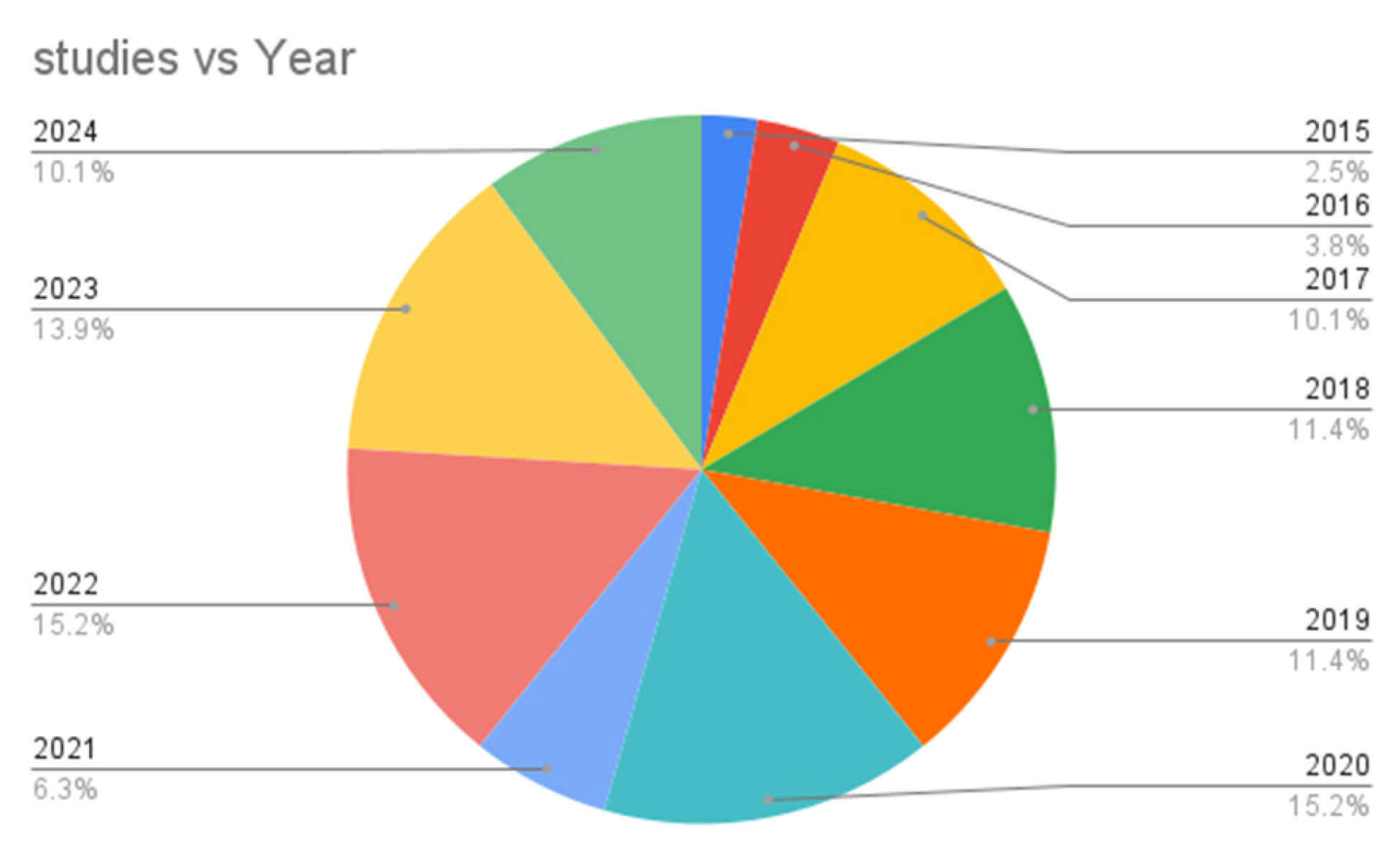

4.2. Year of Publication

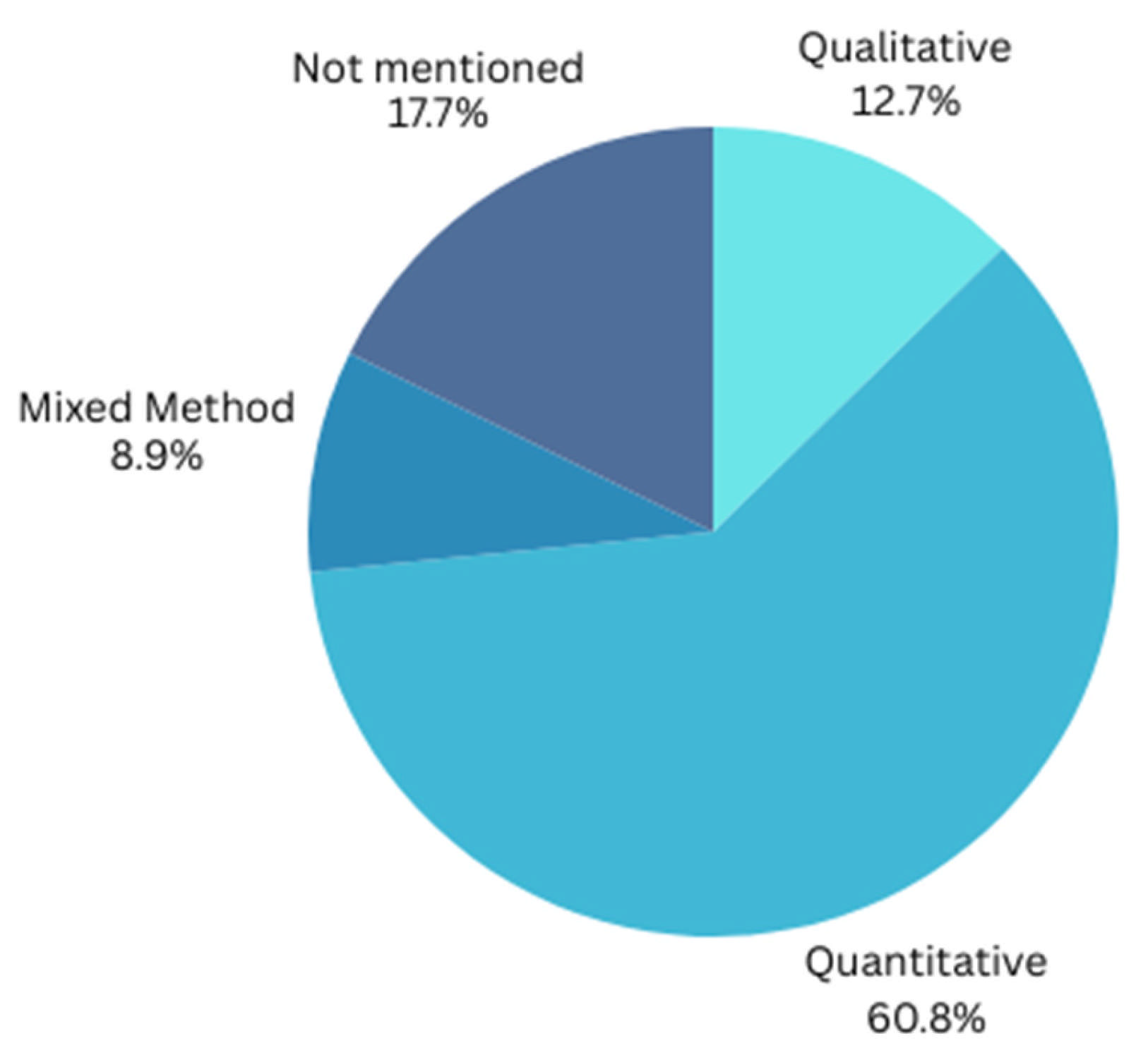

4.3. Research Design

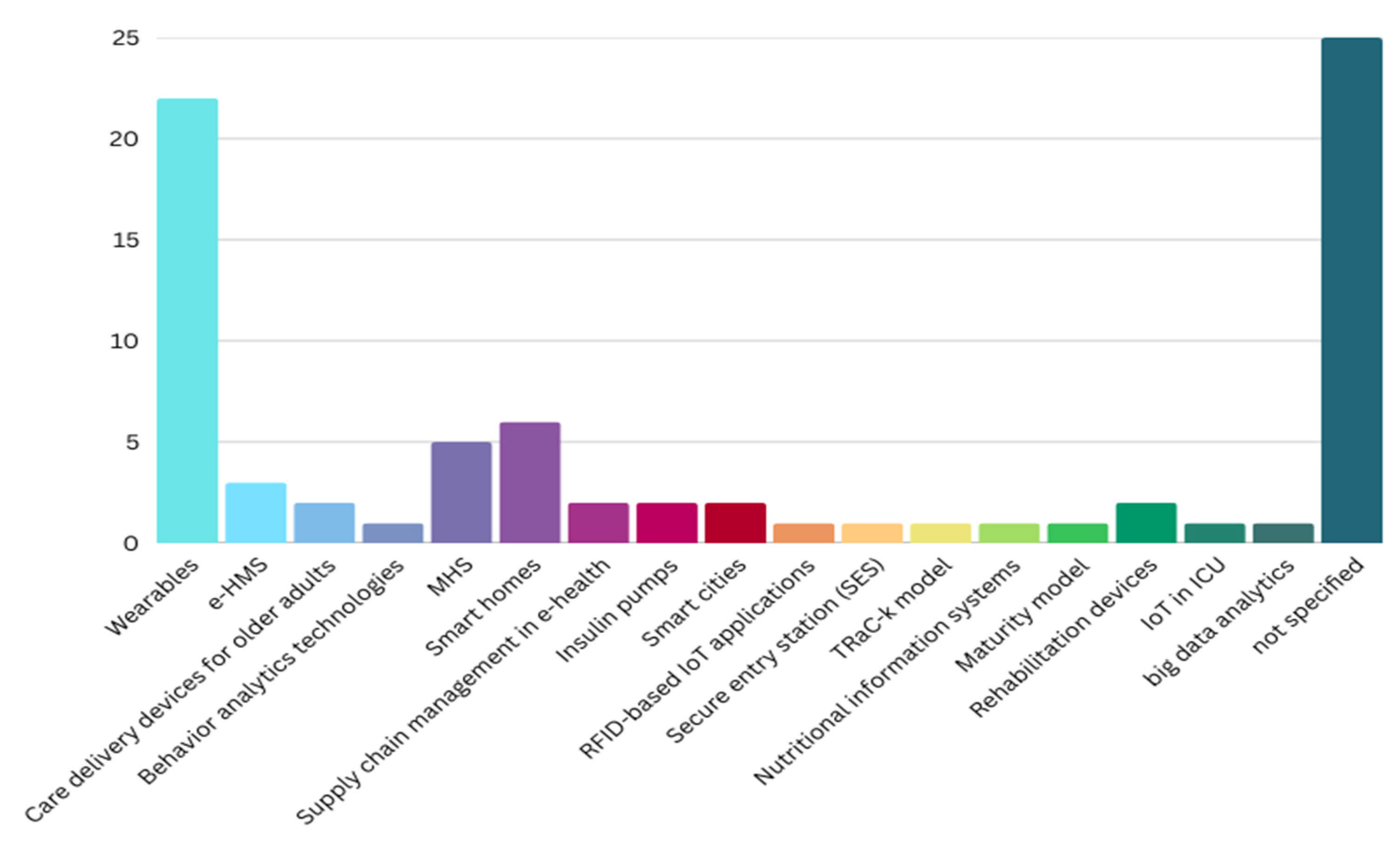

4.4. Technologies Used

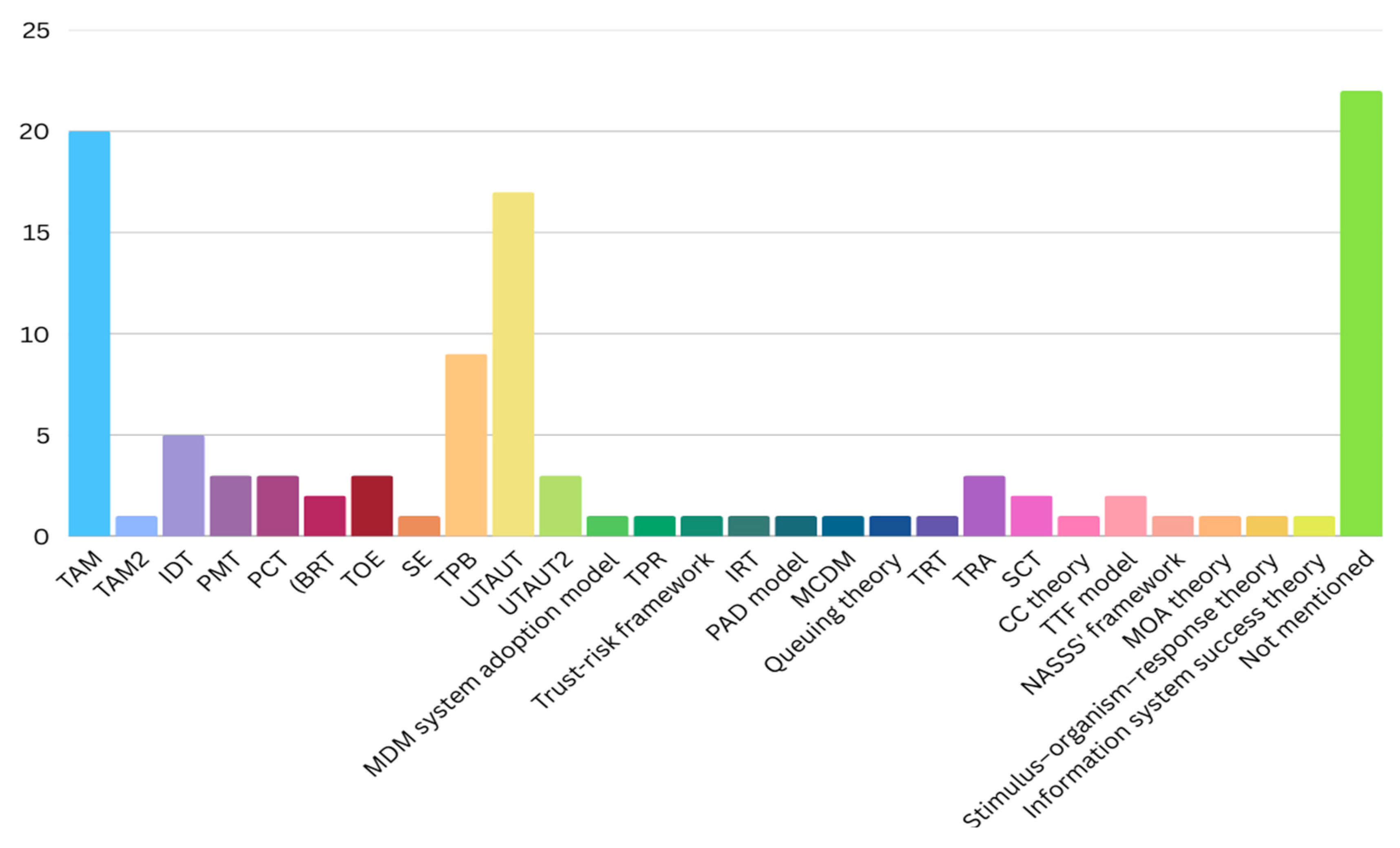

4.5. Theories Used

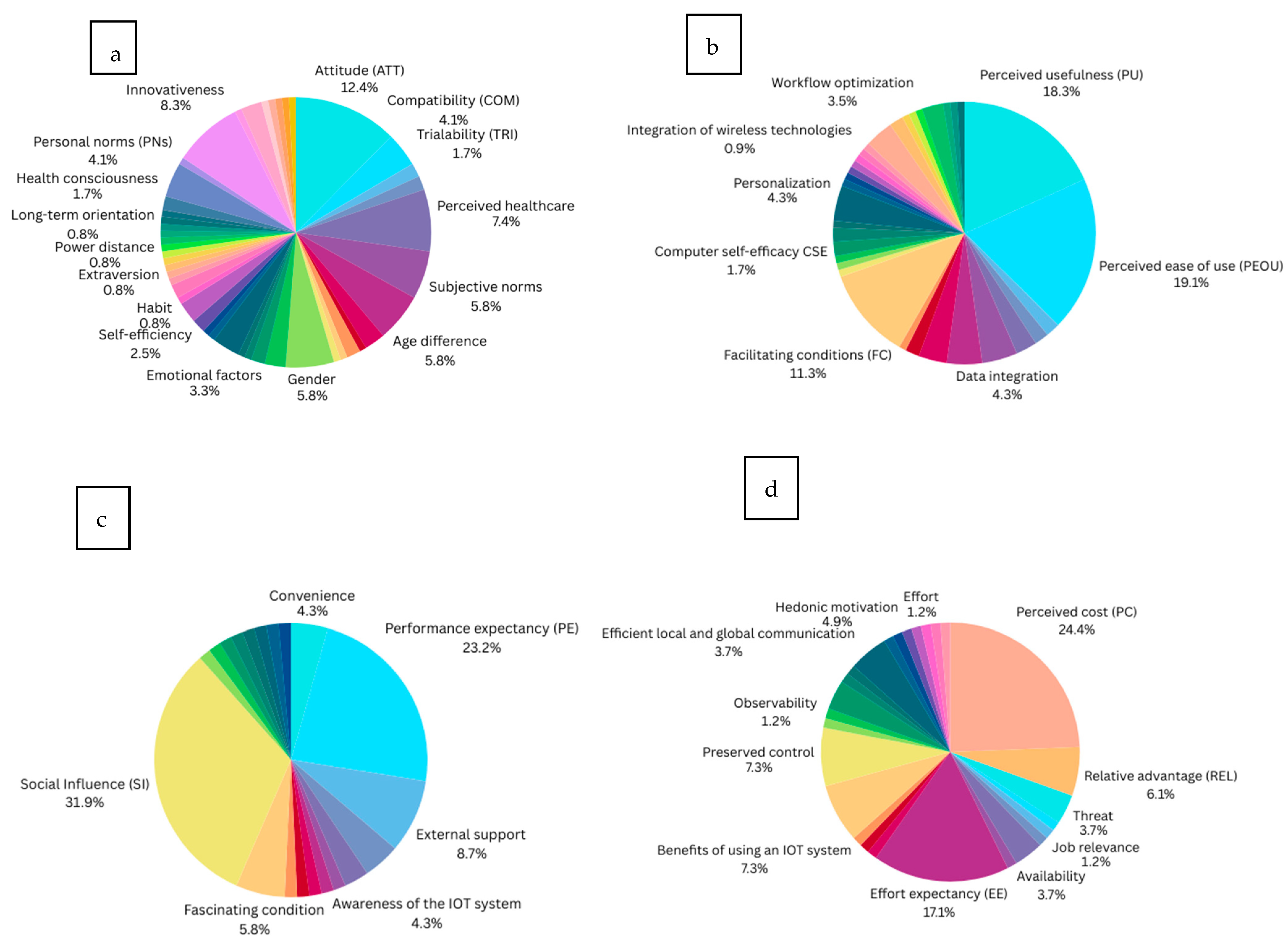

4.6. Factors Influencing IoT Adoption in Healthcare Sectors

4.6.1. Individual Factors

4.6.2. Technological Factors

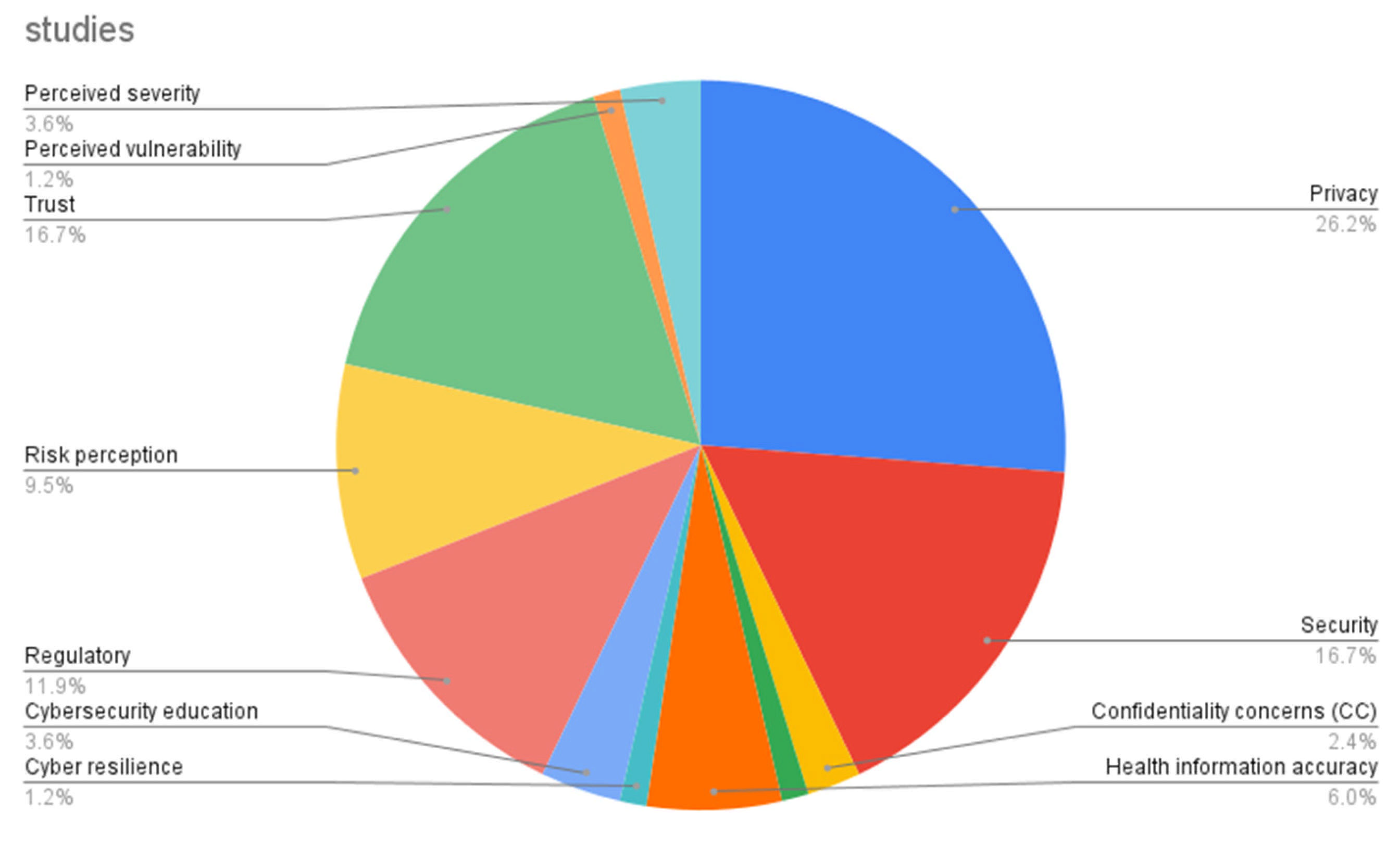

4.6.3. Security Factors

4.6.4. Environmental Factors

4.6.5. Other Factors

5. Gaps and Future Agenda

5.1. IoT in the Healthcare Sector

5.2. Factors

5.3. Cybersecurity Aspects

5.4. Future Recommendations

6. Contribution

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Category | Factor | Study Result | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Significant Effect | Slim to No Effect | ||

| Individual | Attitude (ATT) | [2,32,34,37,40,44,52,57,64,65,79,82,86] | [27,35] |

| Compatibility (COM) | [35,57,64] | [31,71] | |

| Trialability (TRI) | [31,57] | ||

| Image (IMA) | [32,57] | ||

| Perceived healthcare Health values (HV) Health motivation (HM) Personal health beliefs (PHBs): Health improvement Health interests Health anxiety Healthcare vulnerability Perceived health risk (PHR) Human attachment concerns | [32,34,42,46,58,65,102] | [68,69] | |

| Subjective norms | [37,40,42,54,66,82,86] | ||

| Age difference | [28,52,72,79] | [56,74,82] | |

| Comfortability | [77] | [35,47] | |

| Trust in the organization and treatment | [93] | ||

| Traditional barrier | [35] | [49] | |

| Value of openness to change | [35] | ||

| Computer and English language self-efficacy (CESE) | [28] | ||

| Gender | [28,72,77,79] | [48,74,82] | |

| Education | [28,48] | [82] | |

| Occupation, experience | [28,82] | ||

| Technology anxiety (TA) | [36] | ||

| Awareness of disease | [88] | ||

| Emotional support: PAD (pleasure, arousal, dominance) model; emotional factors: empathy, interaction, compassion, interactivity | [54,58,59,62] | ||

| Health expectancy | [1] | ||

| Past behavior frequency | [40] | ||

| Perceived susceptibility | [86] | [68] | |

| Self-efficiency | [43,69,103] | ||

| Habit | [74] | ||

| User satisfaction | [43,100] | ||

| Conscientiousness | [56] | ||

| Agreeableness | [56] | ||

| Extraversion | [56] | ||

| Neuroticism | [56] | ||

| Collectivism | [56] | ||

| Power distance | [56] | ||

| Masculinity | [56] | ||

| Uncertainty avoidance | [56] | ||

| Long-term orientation | [56] | ||

| Positive anticipated emotion | [40] | ||

| Negative anticipated emotion | [40] | ||

| Health consciousness | [40,75] | ||

| Personal factors (e.g., activity patterns and exercise schedule), personal norms (PNs), interpersonal influence, user characteristics; user behavior (UB) | [2,46,103] | [54,65] | |

| Lack of knowledge, decreased sensory perception | [61] | ||

| Innovativeness | [27,32,43,59,62,65,66,82,90,102] | ||

| Lack of need for the technology | [61] | ||

| Technology skills | [61,76,79] | ||

| Fashionability | [66] | ||

| Willingness to learn | [61] | ||

| Limited/fixed income | [61] | ||

| Intrinsic motivation | [62] | ||

| Desire | [40] | ||

| Technological | Perceived usefulness (PU) | [2,27,32,37,43,44,45,47,54,56,57,59,61,62,64,66,69,82,86,102] | [73] |

| Perceived ease of use (PEOU), ease of learning, complexity, usage barriers, adaptability | [1,2,27,32,35,37,44,45,47,49,54,57,59,64,82,86,101,103] | [31,62,66,73] | |

| Facilitation, functionality | [33] | [73] | |

| Ubiquity (UQ), ubiquitous control | [34,35] | ||

| Overall quality (system, information, service) | [42,47,100] | ||

| Ease of data collection, data integration, data governance | [29,83,84,87,91] | ||

| Connectedness | [62,64,83] | [27,66] | |

| Unreliability | [73,87] | [39,91] | |

| Facilitated appropriation | [2,56] | ||

| Cognitive instrumental attitude | [2] | ||

| Facilitating conditions (FCs) | [1,34,45,55,62,68,72,74,75,77,85] | [36,50] | |

| Traceability | [29] | ||

| Observational learning | [81] | ||

| Utilitarian monitoring activity | [81] | ||

| Computer self-efficacy (CSE), IT-related self-efficacy | [57] | [65] | |

| Qualification of resources, quantifying resources | [49,76] | ||

| Visualization of complex workflows | [49] | ||

| Personalization, self-configuration of IoT devices, customizability, user-friendliness | [39,47,59,80,103] | ||

| Integration of wireless technologies. | [91] | ||

| Enabled decision support | [92] | ||

| Latency tolerance | [92] | ||

| Robust computational power | [92] | ||

| Optimizing power consumption | [92] | ||

| Expanded data communication rate (F33) (F33 refers to a specific type of data communication rate used in the context of digital communication systems. The “F” usually indicates a frequency or a modulation scheme, while “33” may represent a particular characteristic, such as the number of bits transmitted per symbol or a specific baud rate) | [92] | ||

| Information pervasiveness | [94] | ||

| Care service efficiency, workflow optimization | [87,90,94,101] | ||

| Care process improvement, efficient business process | [39,94] | ||

| Agility | [38] | ||

| Flexibility | [38] | ||

| Interoperability | [39] | ||

| IT infrastructure Poorly designed interface | [39,41,61] | ||

| Infotainment | [66] | ||

| Wearability | [66] | ||

| Technical efficiency | [45] | ||

| Security | Privacy issue, perceived privacy protection (PPR), privacy risks, enhancement of privacy | [27,29,31,32,39,52,57,58,66,67,73,83,87,91,95,96,98] | [40,48,50,60,102] |

| Security concerns, security risk | [29,31,39,48,50,52,67,73,83,87,95,96] | [60,84] | |

| Confidentiality concerns | [67] | [28] | |

| Assurance barriers | [63] | ||

| Defective health information, health information accuracy, precise diagnosis | [63,69,87,102] | [81] | |

| Cyber resilience, | [2] | ||

| Adequate training, cybersecurity education | [61,80,84] | ||

| Regulatory environment, regulatory affairs, government regulations, presence of clear objectives and plans for MIoT systems adoption, legal frameworks, roles and responsibilities, compliance and policy | [29,41,62,67,76,83,84,96,97] | [67,71] | |

| Risk perception, perceived risk, risk barrier | [35,45,49,52,86,99] | [1,72] | |

| Perceived trust (PT) | [2,30,33,36,48,52,60,73,75,86,91,93,100] | [68] | |

| Perceived vulnerability | [69] | ||

| Perceived severity | [68,69,86] | ||

| Environmental | Perceived convenience value (PCV) | [27,35,59] | |

| Performance expectancy (PE) | [28,30,33,36,48,50,55,58,60,68,70,72,74,75,77,85] | ||

| External support (ES) from government entities, consultants, and software suppliers, as well as selection of a reliable and experienced MIoT vendor, skilled IT professionals, vendor credibility | [29,39,71,76,78,101] | ||

| Awareness of the IoT system | [65,76,88] | ||

| Support and commitment of top management, management support (MS) | [29,71] | ||

| Organizational readiness | [71] | ||

| Organizational culture | [83] | ||

| Epidemic ecosystem | [62] | ||

| Monitoring and governance | [83] | ||

| Readiness | [45] | ||

| Opportunity factors: fascinating conditions, preserved fascinating conditions | [30,74] | [60,68] | |

| Social influence (SI), social support, reference group influence, preserved social usefulness, social norms | [1,2,28,34,44,46,48,55,58,60,62,70,72,75,77,85,102,103] | [36,50,68,74] | |

| Awareness of consequences (AoC) | [46] | ||

| Ascription of responsibility (AoR) | [46] | ||

| Digital and data literacy | [85] | ||

| Doctor–patient relationship (D-PR) | [68] | ||

| Collaboration environment | [100] | ||

| Openness | [56] | ||

| Physician recommendation | [61] | ||

| Free equipment | [61] | ||

| Other | Perceived cost (PC), preserved value (PV) | [27,31,36,39,42,49,57,58,60,61,64,67,72,78,87,98] | [1,65,74,77] |

| Relative advantage (REL) | [32,34,35] | [31,71] | |

| Threat | [30,33] | [28] | |

| Job relevance | [42] | ||

| Information quality | [42] | ||

| Application areas | [87] | ||

| Availability | [44,48,89] | ||

| Perceived pressure | [44] | ||

| Effort expectancy (EE) | [36,55,60,68,70,72,74,75,85] | [28,48,50,58,77] | |

| Value creation | [83] | ||

| Expert advice (EA) | [36] | ||

| Life quality expectancy | [58] | ||

| Benefits: functional benefits, informational benefits, psychological benefits, external benefits, benefits of using an IoT system | [42,45,63,88,90,99] | ||

| Preserved control, perceived behavioral control | [39,40,52,64,99] | [37] | |

| Observability | [31] | ||

| Close to action | [68] | ||

| Discomfort | [50] | ||

| Determining the type of signals to be collected, psychological/environmental | [92] | ||

| Hedonic motivation | [60,69,76] | [74] | |

| Moral consideration | [99] | ||

| Preserved as a fuse | [37] | ||

| Preserved novelty | [69] | ||

| e-Loyalty | [43] | ||

| Effort | [100] | ||

| Actual control | [99] | ||

| Overall consistency of internet coverage, efficient local and global communication | [39,41,91] | [66] | |

References

- Yin, Z.; Yan, J.; Fang, S.; Wang, D.; Han, D. User acceptance of wearable intelligent medical devices through a modified unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. Ann. Transl. Med. 2022, 10, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsourela, M.; Nerantzaki, D.M. An internet of things (Iot) acceptance model. assessing consumer’s behavior toward iot products and applications. Future Internet 2020, 12, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashton, K. That ‘Internet of Things’ Thing. 2010. Available online: https://www.rfidjournal.com/expert-views/that-internet-of-things-thing/73881/ (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- HAbdul-Ghani, A.; Konstantas, D. A comprehensive study of security and privacy guidelines, threats, and countermeasures: An IoT perspective. J. Sens. Actuator Netw. 2019, 8, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minerva, R.; Rotondi, D. Towards a Definition of the Internet of Things (IoT). 2014. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/317588072 (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Nižetić, S.; Šolić, P.; González-de-Artaza, D.L.-D.-I.; Patrono, L. Internet of Things (IoT): Opportunities, issues and challenges towards a smart and sustainable future. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 274, 122877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambe, A.H.; Brereton, M.; Soro, A.; Chai, M.Z.; Buys, L.; Roe, P. Older people inventing their personal internet of things with the IoT un-kit experience. In Proceedings of the Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Glasgow, UK, 4–9 May 2019; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronlid, C.; Brantnell, A.; Elf, M.; Borg, J.; Palm, K. Sociotechnical analysis of factors influencing IoT adoption in healthcare: A systematic review. Technol. Soc. 2024, 78, 102675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, F.; Yang, H.; Qiu, L.; Wang, X.; Ren, Z.; Wei, S.; Zhou, H.; Chen, Y.; Hu, H. Innovation networks in the advanced medical equipment industry: Supporting regional digital health systems from a local–national perspective. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1635475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Zhou, L.; Wang, S.; Fan, C.; Huang, D. Facilitating Patient Adoption of Online Medical Advice Through Team-Based Online Consultation. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaraj, S.; Sundaravaradhan, S. Challenges and Opportunities in IoT Healthcare Systems: A Systematic Review; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaid, M.; Haleem, A.; Singh, R.P.; Suman, R. Towards insighting cybersecurity for healthcare domains: A comprehensive review of recent practices and trends. Cyber Secur. Appl. 2023, 1, 100016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Piramuthu, S. IoT security perspective of a flexible healthcare supply chain. Inf. Technol. Manag. 2018, 19, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirbhulal, S.; Samuel, O.W.; Wu, W.; Sangaiah, A.K.; Li, G. A joint resource-aware and medical data security framework for wearable healthcare systems. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2019, 95, 382–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, A.L.; Pérez, M.G.; Ruiz-Martínez, A. A Comprehensive Review of the State-of-the-Art on Security and Privacy Issues in Healthcare. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 55, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HHS. HIPAA Home. Available online: https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/index.html (accessed on 5 July 2025).

- General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)—Legal Text. Available online: https://gdpr-info.eu/ (accessed on 5 July 2025).

- Gafni, R.; Pavel, T. Cyberattacks against the health-care sectors during the COVID-19 pandemic. Inf. Comput. Secur. 2022, 30, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartwright, A.J. The elephant in the room: Cybersecurity in healthcare. J. Clin. Monit. Comput. 2023, 37, 1123–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kashani, M.H.; Madanipour, M.; Nikravan, M.; Asghari, P.; Mahdipour, E. A systematic review of IoT in healthcare: Applications, techniques, and trends. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2021, 192, 103164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawad, H.H.M.; Hassan, Z.B.; Zaidan, B.B.; Jawad, F.H.M.; Jawad, D.H.M.; Alredany, W.H.D. A Systematic Literature Review of Enabling IoT in Healthcare: Motivations, Challenges, and Recommendations. Electronics 2022, 11, 3223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-rawashdeh, M.; Keikhosrokiani, P.; Belaton, B.; Alawida, M.; Zwiri, A. IoT Adoption and Application for Smart Healthcare: A Systematic Review. Sensors 2022, 22, 5377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wang, J.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Y. A review of IoT applications in healthcare. Neurocomputing 2024, 565, 127017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoli, C.; Schabram, K. A Guide to Conducting a Systematic Literature Review of Information Systems Research; Working Papers on Information Systems; Association for Information Systems: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wohlin, C.; Mendes, E.; Felizardo, K.R.; Kalinowski, M. Guidelines for the search strategy to update systematic literature reviews in software engineering. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2020, 127, 106366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boell, S.K.; Cecez-Kecmanovic, D. On being ‘systematic’ in literature reviews in IS. J. Inf. Technol. 2015, 30, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massaro, M.; Dumay, J.; Guthrie, J. On the shoulders of giants: Undertaking a structured literature review in accounting. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2016, 29, 767–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchenham, B.; Charters, S.M. Guidelines for performing Systematic Literature Reviews in Software Engineering. 2007. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/302924724 (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Cai, L.; Zhu, Y. The challenges of data quality and data quality assessment in the big data era. Data Sci. J. 2015, 14, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alanazi, M.; Soh, B. Behavioral Intention to Use IoT Technology in Healthcare Settings. Eng. Technol. Appl. Sci. Res. 2019, 5, 4769–4774. Available online: https://www.etasr.com (accessed on 15 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Alomari, A.; Soh, B. Determinants of Medical Internet of Things Adoption in Healthcare and the Role of Demographic Factors Incorporating Modified UTAUT. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2023, 14, 17–31. Available online: https://www.ijacsa.thesai.org (accessed on 12 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Abuabid, A.A. Preliminary Model on Factors Influencing the Adoption of Medical Internet of Things (MIoT) Systems in Small and Medium-sized Hospitals in Saudi Arabia. In Proceedings of the 2024 3rd International Conference on Computational Modelling, Simulation and Optimization, ICCMSO 2024, Phuket, Thailand, 14–16 June 2024; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.: Singapore, 2024; pp. 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Moteri, M.; Alojail, M. Factors influencing the Supply Chain Management in e-Health using UTAUT model. Electron. Res. Arch. 2023, 31, 2855–2877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masmali, F.H.; Miah, S.J. Adoption of IoT based innovations for healthcare service delivery in Saudi Arabia. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Asia-Pacific Conference on Computer Science and Data Engineering, CSDE 2019, Melbourne, Australia, 9–11 December 2019; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karahoca, A.; Karahoca, D.; Aksöz, M. Examining intention to adopt to internet of things in healthcare technology products. Kybernetes 2018, 47, 742–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadhich, M.; Hiran, K.K.; Rao, S.S.; Sharma, R. Factors Influencing Patient Adoption of the IoT for e-Health Management Systems (e-HMS) Using the UTAUT Model: A High order SeM-ANN Approach. Int. J. Ambient Comput. Intell. 2022, 13, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, A.; Kovid, R.K.; Thatha, M.; Gupta, J. Adoption of IoT-based healthcare devices: An empirical study of end consumers in an emerging economy. Paladyn J. Behav. Robot. 2023, 14, 20220106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivathanu, B. Adoption of internet of things (IOT) based wearables for healthcare of older adults—A behavioural reasoning theory (BRT) approach. J. Enabling Technol. 2018, 12, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, D.; Funilkul, S.; Charoenkitkarn, N.; Kanthamanon, P. Internet-of-Things and Smart Homes for Elderly Healthcare: An End User Perspective. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 10483–10496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mital, M.; Chang, V.; Choudhary, P.; Papa, A.; Pani, A.K. Adoption of Internet of Things in India: A test of competing models using a structured equation modeling approach. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2018, 136, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Bhatt, V.; Chakravorty, T. Impact of iot adoption on agility and flexibility of healthcare organization. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Explor. Eng. 2019, 8, 2673–2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, S. System Dynamics perspective for Adoption of Internet of Things: A Conceptual Framework. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Shailja-Tripathi/publication/338365676_System_Dynamics_perspective_for_Adoption_of_Internet_of_Things_A_Conceptual_Framework/links/5e143953a6fdcc28375dd24c/System-Dynamics-perspective-for-Adoption-of-Internet-of-Things-A-Conceptual-Framework.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Srivastava, N.K.; Chatterjee, N.; Subramani, A.K.; Jan, N.A.; Singh, P.K. Is health consciousness and perceived privacy protection critical to use wearable health devices? Extending the model of goal-directed behavior. Benchmarking 2022, 29, 3079–3096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desingh, V.; Baskaran, R. Internet of Things adoption barriers in the Indian healthcare supply chain: An ISM-fuzzy MICMAC approach. Int. J. Health Plan. Manag. 2022, 37, 318–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okazaki, S.; Blas, S.S.; Castañeda, J.A. Physicians’ adoption of mobile health monitoring systems in spain: Competing models and impact of prior experience. J. Electron. Commer. Res. 2015, 16, 194. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Caro, E.; Cegarra-Navarro, J.G.; García-Pérez, A.; Fait, M. Healthcare service evolution towards the Internet of Things: An end-user perspective. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2018, 136, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, N.; Rau, P.L.P. The acceptance of personal health devices among patients with chronic conditions. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2015, 84, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Li, Q.; Han, S. Using Extended Technology Acceptance Model to Assess the Adopt Intention of a Proposed IoT-Based Health Management Tool. Sensors 2022, 22, 6092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Al Mamun, A.; Wu, M.; Naznen, F. Strengthening health monitoring: Intention and adoption of Internet of Things-enabled wearable healthcare devices. Digit Health 2024, 10, 20552076241279199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Negera, D.T.; Chudhery, M.A.Z.; Zhao, Q.; Gao, L. IoT and Motion Recognition-based Healthcare Rehabilitation Systems (IMRHRS): An Empirical Examination from Physicians’ Perspective Using Stimulus-Organism-Response Theory. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 142863–142882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawad, H.H.M.; Hassan, Z.B.; Zaidan, B.B. Factors Influencing the Behavioural Intention of Patients with Chronic Diseases to Adopt IoT-Healthcare Services in Malaysia. J. Hunan Univ. Nat. Sci. 2023, 50, 26–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arifin, T.R.T.; Mohamad, Z.Z.; Samsuri, A.S.; Hussin, S.M.; Zainol, S.S.; Badaruddin, M.N.A. Resistance and drivers to adopting the internet of things in healthcare services. Platf. A J. Manag. Humanit. 2022, 5, 16–26. [Google Scholar]

- Doualeh, A.I.; Rahman, N.A.A.; Ismail, N. A Survey of Adopting Smart Home Healthcare via IoT Technology. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Developments in eSystems Engineering, DeSE, Sharjah, United Arab Emirates, 7–10 December 2021; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.: Singapore, 2021; pp. 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malarvizhi, C.A.; Subramaniam, S.S.; Jayashree, S. Analysing the Behaviour Intention of IOT Adoption Among Elderly NCD Patients in Malaysia. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Sustainable Engineering Solution, CISES 2023, Greater Noida, India, 28–30 April 2023; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.: Singapore, 2023; pp. 1029–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alraja, M. Frontline healthcare providers’ behavioural intention to Internet of Things (IoT)-enabled healthcare applications: A gender-based, cross-generational study. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 174, 121256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alraja, M.N.; Farooque, M.M.J.; Khashab, B. The Effect of Security, Privacy, Familiarity, and Trust on Users’ Attitudes Toward the Use of the IoT-Based Healthcare: The Mediation Role of Risk Perception. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 111341–111354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonas, D.; Maria, E.; Sutarto; Widiasari, I.R.; Rahardja, U.; Wellem, T. Design of a TAM Framework with Emotional Variables in the Acceptance of Health-based IoT in Indonesia. ADI J. Recent Innov. 2023, 5, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurhayati, S.; Anandari, D.; Ekowati, W. Unified Theory of Acceptance and Usage of Technology (UTAUT) Model to Predict Health Information System Adoption. J. Kesehat. Masy. 2019, 15, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayoga, T.; Abraham, J. Behavioral intention to use IoT health device: The role of perceived usefulness, facilitated appropriation, big five personality traits, and cultural value orientations. Int. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. 2016, 6, 1751–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhasan, A.; Audah, L.; Ibrahim, I.; Al-Sharaa, A.; Al-Ogaili, A.S.; Mohammed, J.M. A case-study to examine doctors’ intentions to use IoT healthcare devices in Iraq during COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Pervasive Comput. Commun. 2022, 18, 527–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaiad, A.; Zhou, L. Patients’ adoption of WSN-Based smart home healthcare systems: An integrated model of facilitators and barriers. IEEE Trans. Prof. Commun. 2017, 60, 4–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.J.; Hwang, Y.C. Exploring the Factors Affecting the Continued Usage Intention of IoT-Based Healthcare Wearable Devices Using the TAM Model. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldossari, M.Q.; Sidorova, A. Consumer Acceptance of Internet of Things (IoT): Smart Home Context. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2020, 60, 507–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cajita, M.I.; Hodgson, N.A.; Lam, K.W.; Yoo, S.; Han, H.R. Facilitators of and Barriers to mHealth Adoption in Older Adults with Heart Failure. CIN Comput. Inform. Nurs. 2018, 36, 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, K.; Koh, C.; Prybutok, V.; Johnson, V. WIoT Adoption Among Young Adults in Healthcare Crises. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2022, 63, 1316–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consumer Reasoning Cognition in Adopting IoT for Healthcare Purposes: A Behavioral Reasoning Theory Perspective. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4241197 (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Park, E.; Cho, Y.; Han, J.; Kwon, S.J. Comprehensive Approaches to User Acceptance of Internet of Things in a Smart Home Environment. IEEE Internet Things J. 2017, 4, 2342–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Lee, K. Factors that influence an individual’s intention to adopt a wearable healthcare device: The case of a wearable fitness tracker. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2018, 129, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.S.; Lee, S.C.; Ji, Y.G. Wearable device adoption model with TAM and TTF. Int. J. Mob. Commun. 2016, 14, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, M.I.; Mian, N.A.; Sohail, A.; Alyas, T.; Ahmad, R. Evaluation of the challenges in the internet of medical things with multicriteria decision making (AHP and TOPSIS) to overcome its obstruction under fuzzy environment. Mob. Inf. Syst. 2020, 2020, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ZSolangi, A.; Solangi, Y.A.; Maher, Z.A. Adoption of IoT-based Smart Healthcare: An Empirical Analysis in the Context of Pakistan. J. Hunan Univ. Nat. Sci. 2021, 48, 143–153. Available online: https://www.jonuns.com/index.php/journal/article/view/704 (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Zhang, Q.; Khan, S.; Khan, S.U.; Khan, I.U. Assessing the older population acceptance of healthcare wearable in a developing Country: An extended PMT model. J. Data Inf. Manag. 2023, 5, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahri, A.S.; Massan, S.-R.; Thebo, L.A. An overview of AI enabled M-IoT wearable technology and its effects on the conduct of medical professionals in Public Healthcare in Pakistan. 3C Tecnol. Glosas Innov. Apl. Pyme 2020, 9, 87–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, S.B.; Azam, M.; Boulos, M.N.K.; Bhatti, R. Leveraging the TOE Framework: Examining the Potential of Mobile Health (mHealth) to Mitigate Health Inequalities. Information 2024, 15, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arfi, W.B.; Nasr, I.B.; Khvatova, T.; Zaied, Y.B. Understanding Acceptance of eHealthcare by IoT Natives and IoT Immigrants: An Integrated Model of UTAUT, Perceived Risk, and Financial Cost. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 163, 120437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, S.; Bello, A.; Maurushat, A.; Farid, F. Security Risks and User Perception towards Adopting Wearable Internet of Medical Things. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walle, A.D.; Jemere, A.T.; Tilahun, B.; Endehabtu, B.F.; Wubante, S.M.; Melaku, M.S.; Tegegne, M.D.; Gashu, K.D. Intention to use wearable health devices and its predictors among diabetes mellitus patients in Amhara region referral hospitals, Ethiopia: Using modified UTAUT-2 model. Inform. Med. Unlocked 2023, 36, 101157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-C. Exploring the Usage Intentions of Wearable Medical Devices: A Demonstration Study. Interact. J. Med. Res. 2020, 9, e19776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bele, S.; Cassidy, C.; Curran, J.; Johnson, D.W.; Saunders, C.; Bailey, J.A.M. Barriers and enablers to implementing a virtual tertiary-regional Telemedicine Rounding and Consultation (TRAC) model of inpatient pediatric care using the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) approach: A study protocol. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.Z.; Hoque, M.R.; Hu, W.; Barua, Z. Factors influencing the adoption of mHealth services in a developing country: A patient-centric study. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 50, 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reidy, C.; A’cOurt, C.; Jenkins, W.; Jani, A.; Ramos, A.; Morys-Carter, M.; Papoutsi, C. ‘The plural of silo is not ecosystem’: Qualitative study on the role of innovation ecosystems in supporting ‘Internet of Things’ applications in health and care. Digit. Health 2023, 9, 20552076221147114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achituv, D.B.; Haiman, L. Physicians’ attitudes toward the use of IoT medical devices as part of their practice. Online J. Appl. Knowl. Manag. 2016, 4, 128–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagliardi, A.R.; Carrubbo, L.; Rozenes, S.; Fux, A.; Siano, D. Assessing IoT integration in ICUs’ settings and management: A cross-country analysis among local healthcare organizations. Digit. Policy Regul. Gov. 2024. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canhoto, A.I.; Arp, S. Exploring the factors that support adoption and sustained use of health and fitness wearables. J. Mark. Manag. 2016, 33, 32–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodić, B.; Stevanović, V.; Labus, A.; Kljajić, D.; Trajkov, M. Adoption Intention of an IoT Based Healthcare Technologies in Rehabilitation Process. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 2023, 40, 2873–2886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasi, F.; Beirens, B.; Serral, E. Maturity model for iot adoption in hospitals. Comput. Inform. 2022, 41, 213–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleveland, S.M.; Haddara, M. Internet of Things for diabetics: Identifying adoption issues. Internet Things 2023, 22, 100798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edu, A.S. Configural paths for IoTs and big data analytics acceptance for healthcare improvement: A fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis. Aslib J. Inf. Manag. 2024, 76, 800–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Ni, Q.; Zhou, R. What factors influence the mobile health service adoption? A meta-analysis and the moderating role of age. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 43, 342–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charyyev, B.; Mansouri, M.; Gunes, M.H. Modeling the Adoption of Internet of Things in Healthcare: A Systems Approach. In Proceedings of the ISSE 2021—7th IEEE International Symposium on Systems Engineering, Proceedings, Vienna, Austria, 13 September–13 October 2021; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.: Singapore, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johri, A.; Bhadula, S.; Sharma, S.; Shukla, A.S. Assessment of factors affecting implementation of IoT based smart skin monitoring systems. Technol. Soc. 2022, 68, 101908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strielkina, A.; Uzun, D.; Kharchenko, V. IDAACS 2017. Modelling of Healthcare IoT Using the Queueing Theory. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 9th International Conference on Intelligent Data Acquisition and Advanced Computing Systems: Technology and Applications, Bucharest, Romania, 21–23 September 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Philip, N.Y.; Rodrigues, J.J.P.C.; Wang, H.; Fong, S.J.; Chen, J. Internet of Things for In-Home Health Monitoring Systems: Current Advances, Challenges and Future Directions. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2021, 39, 300–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niranjan, S.K.; Raja, J.; Rajini, A.R. Survey of Smart healthcare systems using Internet of things (IoT). In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Communication, Computing & Internet of Things: IC3IoT 2018, Department of Electronics and Communication Engineering, Sri Sairam Engineering College, Chennai, India, 15–17 February 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Habibzadeh, H.; Dinesh, K.; Shishvan, O.R.; Boggio-Dandry, A.; Sharma, G.; Soyata, T. A Survey of Healthcare Internet of Things (HIoT): A Clinical Perspective. IEEE Internet Things J. 2019, 7, 53–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, V.; Chakraborty, S. Importance of trust in iot based wearable device adoption by patient: An empirical investigation. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on IoT in Social, Mobile, Analytics and Cloud, ISMAC 2020, Palladam, India, 7–9, October 2020; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.: Singapore, 2020; pp. 1226–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Bhatt, V. Mobile IoT adoption as antecedent to Care-Service Efficiency and Improvement: Empirical study in Healthcare-context. J. Int. Technol. Inf. Manag. 2019, 28, 101–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, S.; Zafar, N.A.; Khan, R.Y. A Survey of Security and Privacy Issues in IoT for Smart Cities. In Proceedings of the 2017 Fifth International Conference on Aerospace Science & Engineering (ICASE), Islamabad, Pakistan, 14–16 November 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Raje, V.V.; Mohite, R.V.; Srivastava, S.; Lipi, K.; Gavhane, Y.; Devi, T.J. Data Security and Privacy in the Smart Healthcare System. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Healthcare Innovations, Software and Engineering Technologies, HISET 2024, Karad, India, 18–19 January 2024; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.: Singapore, 2024; pp. 204–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulghani, H.A.; Nijdam, N.A.; Konstantas, D. Analysis on Security and Privacy Guidelines: RFID-Based IoT Applications. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 131528–131554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newcombe, L.; Yang, P.; Carter, C.; Hanneghan, M. Internet of things enabled technologies for behaviour analytics in elderly person care: A survey. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Internet of Things, IEEE Green Computing and Communications, IEEE Cyber, Physical and Social Computing, IEEE Smart Data, iThings-GreenCom-CPSCom-SmartData 2017, Exeter, UK, 21–23 June 2017; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.: Singapore, 2017; pp. 863–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Princi, E.; Krämer, N.C. Out of Control—Privacy Calculus and the Effect of Perceived Control and Moral Considerations on the Usage of IoT Healthcare Devices. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 582054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauwed, M.A.; Yahaya, J.; Zulkefli, A.M.; Hamdan, R. Human factors for iot services utilization for health information exchange. J. Theor. Appl. Inf. Technol. 2018, 96, 2095–2105. Available online: https://www.jatit.org/volumes/Vol96No8/3Vol96No8.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Kadu, M.M.; Gray, C.S.; Berta, W. Assessing Factors that Influence the Implementation of Technologies Enabling Integrated Care Delivery for Older Adults with Complex Needs: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Integr. Care 2018, 18, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, M.L.; Chau, K.Y.; Lam, M.H.S.; Tse, G.; Ho, K.Y.; Flint, S.W.; Broom, D.R.; Tso, E.K.H.; Lee, K.Y. Examining consumers’ adoption of wearable healthcare technology: The role of health attributes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abouzahra, M.; Ghasemaghaei, M. The antecedents and results of seniors’ use of activity tracking wearable devices. Health Policy Technol. 2020, 9, 213–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Li, H.; Luo, Y. An empirical study of wearable technology acceptance in healthcare. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2015, 115, 1704–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, S.B.; Xiang, W.; Atkinson, I. Internet of Things for Smart Healthcare: Technologies, Challenges, and Opportunities. IEEE Access 2017, 5, 26521–26544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalsoom, T.; Ramzan, N.; Ahmed, S.; Anjum, N.; Safdar, G.A.; Rehman, M.U. Socio-Organisational Challenges and Impacts of IoT: A Review in Healthcare and Banking. J. Sens. Actuator Netw. 2025, 14, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Q. Digital leadership enhances organizational resilience by fostering job crafting: The moderating role of organizational culture. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 24640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, S.; Thakur, S.; Hussain, S.; Breslin, J.G.; Jameel, S.M. Identification and Authentication in Healthcare Internet-of-Things Using Integrated Fog Computing Based Blockchain Model. Internet Things 2021, 15, 100422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaiah, M.A.; Hajjej, F.; Ali, A.; Pasha, M.F.; Almomani, O. A Novel Hybrid Trustworthy Decentralized Authentication and Data Preservation Model for Digital Healthcare IoT Based CPS. Sensors 2022, 22, 1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Almaiah, M.A.; Hajjej, F.; Pasha, M.F.; Fang, O.H.; Khan, R.; Teo, J.; Zakarya, M. An Industrial IoT-Based Blockchain-Enabled Secure Searchable Encryption Approach for Healthcare Systems Using Neural Network. Sensors 2022, 22, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Kaur, K.; Wang, X.; Kaddoum, G.; Hu, J.; Hassan, M.M. Privacy-Aware Access Control in IoT-Enabled Healthcare: A Federated Deep Learning Approach. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 10, 2893–2902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Rathore, S.; Alfarraj, O.; Tolba, A.; Yoon, B. A framework for privacy-preservation of IoT healthcare data using Federated Learning and blockchain technology. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2022, 129, 380–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosain, Y.; Çakmak, M. XAI-XGBoost: An innovative explainable intrusion detection approach for securing internet of medical things systems. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 22278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sathya, D.; Veena, S.; Yankanchi, S.R.; Manasa, S. Edge Computing and Blockchain-Based Data Security in IoMT. Int. J. Online Biomed. Eng. 2025, 21, 124–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelekoudas-Oikonomou, F.; Zachos, G.; Papaioannou, M.; de Ree, M.; Ribeiro, J.C.; Mantas, G.; Rodriguez, J. Blockchain-Based Security Mechanisms for IoMT Edge Networks in IoMT-Based Healthcare Monitoring Systems. Sensors 2022, 22, 2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xu, J.; Vijayakumar, P.; Sharma, P.K.; Ghosh, U. Homomorphic Encryption-Based Privacy-Preserving Federated Learning in IoT-Enabled Healthcare System. IEEE Trans. Netw. Sci. Eng. 2023, 10, 2864–2880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Sample Size | Period | Results | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [20] | 146 articles | 2015–2020 |

|

|

| [21] | 106 papers | 2015–2022 |

|

|

| [22] | 22 articles | 2015–2021 |

|

|

| [23] | Not mentioned | Not mentioned |

|

|

| [8] | 10 articles | Not mentioned |

|

|

| Current research | 79 articles | 2015–2024 |

|

| Criteria | |

|---|---|

| Inclusions |

|

| Exclusion |

|

| Country | Studies |

|---|---|

| Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) | [31,32,33,34,35] |

| Turkey | [36] |

| India | [37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45] |

| Spain | [46,47] |

| China | [1,48,49,50,51] |

| Malaysia | [40,52,53,54,55] |

| Oman | [56,57] |

| Thailand | [40] |

| Indonesia | [40,58,59,60] |

| Iraq | [61] |

| USA | [62,63,64,65,66] |

| Iran | [67] |

| South Korea | [68,69,70] |

| Pakistan | [71,72,73,74,75] |

| France | [76] |

| Australia | [77] |

| Ethiopia | [78] |

| Taiwan | [79] |

| Canada | [80] |

| Bangladesh | [81] |

| United Kingdom (UK) | [82] |

| Israel | [83,84] |

| Germany | [85] |

| Serbia (Belgrade) | [86] |

| Belgium | [87] |

| Italy | [84] |

| Norway | [88] |

| Ghana | [89] |

| Not mentioned | [2,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105] |

| Year | Studies |

|---|---|

| 2015 | [46,48] |

| 2016 | [60,70,83] |

| 2017 | [36,41,62,68,85,93,99,102] |

| 2018 | [39,40,47,65,69,90,95,104,105] |

| 2019 | [31,35,42,43,57,59,80,98,106] |

| 2020 | [2,61,64,71,74,76,79,81,96,97,103,107] |

| 2021 | [54,56,72,91,94] |

| 2022 | [1,37,38,44,45,49,53,63,67,87,92,101] |

| 2023 | [32,34,52,55,58,66,73,77,78,82,88] |

| 2024 | [33,50,51,75,84,86,89,100] |

| Research Design | Studies |

|---|---|

| Qualitative | [35,45,65,67,80,82,85,87,88,107] |

| Quantitative | [1,2,31,32,34,36,37,38,40,41,42,44,46,47,49,50,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,63,64,66,68,69,70,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,81,86,90,92,97,98,103,106] |

| Mixed methods | [39,48,51,62,83,84,89] |

| Not mentioned | [33,43,71,91,93,94,95,96,99,100,101,102,104,105] |

| Focus Technology | Study |

|---|---|

| Personal IoT health devices, “wearables” | [1,35,36,39,44,48,50,60,66,69,70,73,74,77,78,79,85,92,97,103,106,107] |

| e-Health management system (e-HMS) | [37,49,104] |

| Care delivery devices for older adults | [65,105] |

| Behavior analytics technologies | [102] |

| Mobile health services (MHS) | [46,55,75,81,90] |

| Smart homes | [40,54,62,64,68,94] |

| Supply chain management in e-health | [34,45] |

| Insulin pumps | [88,93] |

| Smart cities | [41,99] |

| RFID-based IoT applications | [101] |

| Secure entry station (SES) | [58] |

| Telemedicine rounding and consulting for kids (TRaC-k) model | [80] |

| Nutritional information systems | [59] |

| Maturity model | [87] |

| Rehabilitation devices | [51,86] |

| IoT in intensive care units (ICUs) | [84] |

| IoT in big data analytics | [89] |

| Not specified | [2,31,32,33,35,38,42,43,47,52,53,55,56,57,61,67,71,72,76,82,83,91,95,96,100] |

| Theory | Studies |

|---|---|

| Technology acceptance model (TAM), IoT acceptance model (IoTAM), | [1,31,36,41,46,49,51,58,60,61,63,68,70,77,84,86,90,106] |

| technological–personal–environmental (TPE) framework | [2,66] |

| Technology acceptance model 2 (TAM2), M2 competitive model | [46] |

| Innovation diffusion theory (IDT) (Diffusion of Innovation [DOI] theory), | [35,36,55,61] |

| consolidated framework for implementation research (CFIR) | [105] |

| Protection motivation theory (PMT) | [36,73,90] |

| Privacy calculus theory (PCT) | [36,56,103] |

| Behavioral reasoning theory (BRT) | [39,67] |

| Technology–organization–environment (TOE) model | [33,52,75] |

| Social exchange (SE) theory | [52] |

| Theory of planned behavior (TPB), | [41,55,56,58,69,86] |

| model of goal-directed behavior (MGB), | [44] |

| value–belief–norm (VBN) model | [50,55] |

| Unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT), | [1,34,37,40,52,54,59,62,72,74,76,79,81,83,89] |

| unified theory of acceptance and use of technology–hospital staff (UTAUT-HS) | [32,89] |

| Unified theory of acceptance and use of technology 2 (UTAUT2) | [38,64,78] |

| Okazaki et al.’s (2015) mobile phone-based diabetes monitoring (MDM) system adoption model | [46] |

| Theory of perceived risk (TPR) | [1] |

| Trust–risk framework | [56] |

| Innovation resistance theory (IRT) | [53] |

| Pleasure, arousal, dominance (PAD) model | [62] |

| Multicriteria decision-making methods (MCDM) using analytic hierarchy process (AHP) and the technique for order preference by similarity to ideal solution (TOPSIS) | [71] |

| Queueing theory | [93] |

| Technology readiness theory (TRT) | [54] |

| Theory of reasoned action (TRA), | [41] |

| health belief model (HBM), | [72,106] |

| social cognitive theory (SCT), theoretical domains framework (TDF) | [69] [80] |

| Cybernetic control (CC) theory | [42] |

| Fit between the individuals, task, and technology (FITT) framework, | [105] |

| task–technology fit (TTF) model | [70] |

| Non-adoption, abandonment, scale-up, spread, sustainability (NASSS) framework. | [82] |

| Motivation, opportunity, ability (MOA) theory | [49] |

| Stimulus–organism–response theory | [51] |

| Information system success theory | [51] |

| Not mentioned | [43,45,47,48,57,65,77,85,87,88,91,92,94,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,107] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alnajim, R.; Alkhalifah, A. Exploring Factors Affecting the Adoption of IoT in Healthcare: A Systematic Literature Review. Healthcare 2025, 13, 3157. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233157

Alnajim R, Alkhalifah A. Exploring Factors Affecting the Adoption of IoT in Healthcare: A Systematic Literature Review. Healthcare. 2025; 13(23):3157. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233157

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlnajim, Ruba, and Ali Alkhalifah. 2025. "Exploring Factors Affecting the Adoption of IoT in Healthcare: A Systematic Literature Review" Healthcare 13, no. 23: 3157. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233157

APA StyleAlnajim, R., & Alkhalifah, A. (2025). Exploring Factors Affecting the Adoption of IoT in Healthcare: A Systematic Literature Review. Healthcare, 13(23), 3157. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233157