The HIT-6 Questionnaire Corresponds to the PedMIDAS for Assessment of Pediatric Headaches

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Patients and Methods

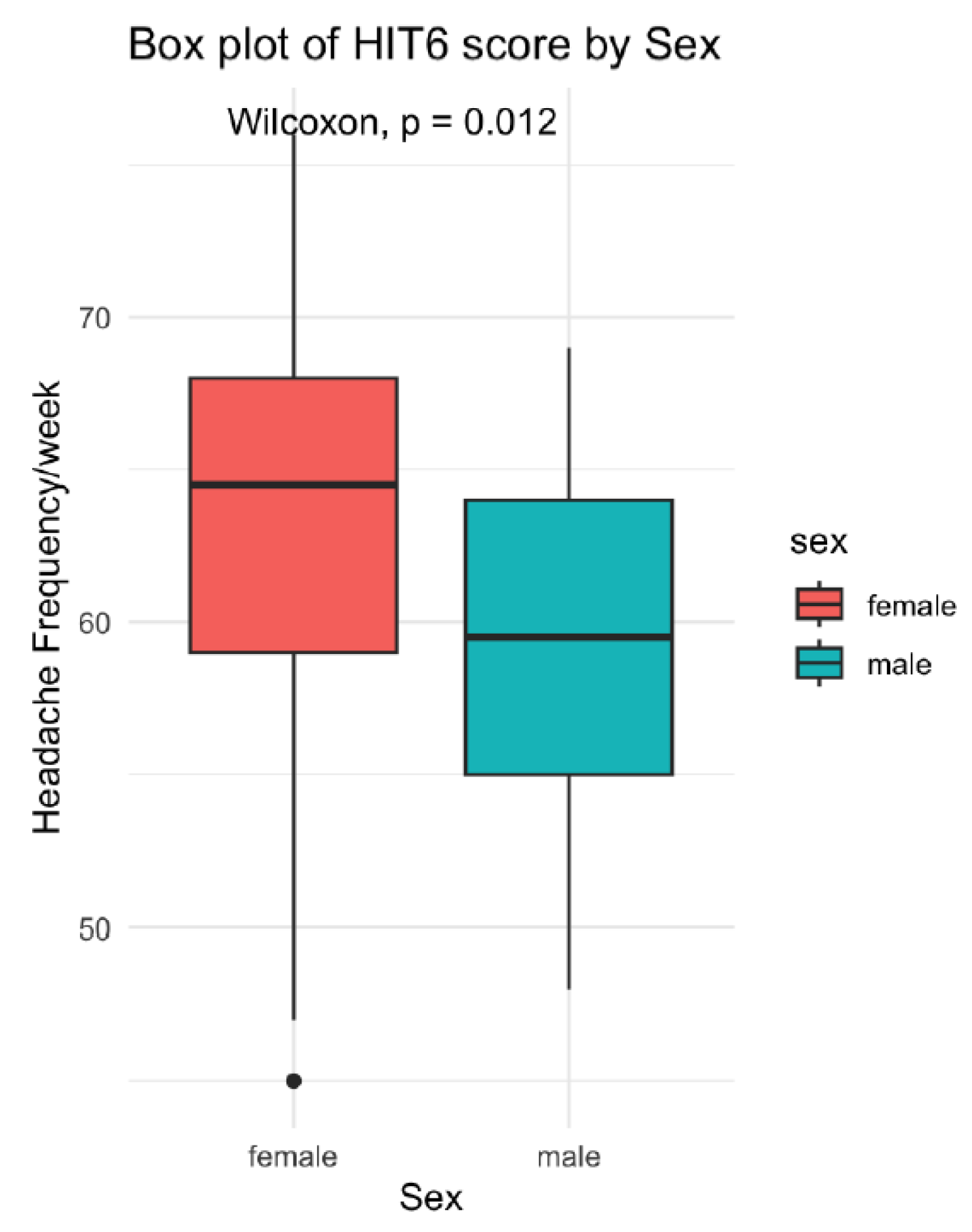

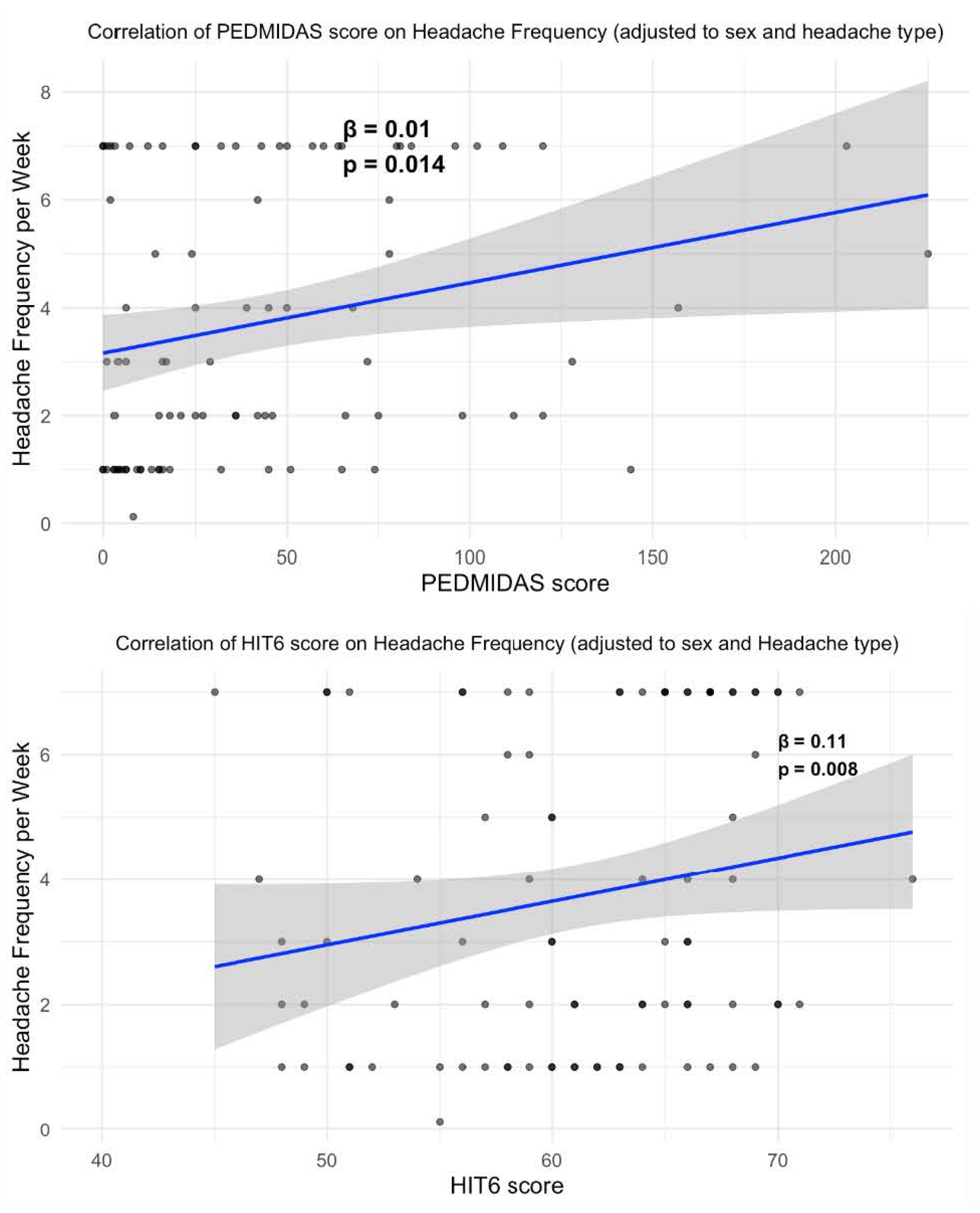

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Clinical Implications

References

- Abu-Arefeh, I.; Russell, G. Prevalence of headache and migraine in schoolchildren. BMJ 1994, 309, 765–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genizi, J.; Lahoud, D.; Cohen, R. Migraine abortive treatment in children and adolescents in Israel. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 7418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD 2016 Neurology Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of neurological disorders, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019, 18, 459–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2023 Headache Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of headache disorders, 1990-2023: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2023. Lancet Neurol. 2025, 24, 1005–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Luo, R.; Wen, Q. Rising trends in the burden of migraine among children and adolescents: A comprehensive analysis from 1990 to 2021 with future predictions. Front. Public Health 2025, 23, 1634098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genizi, J.; Khourieh Matar, A.; Schertz, M.; Zelnik, N.; Srugo, I. Pediatric mixed headache—The relationship between migraine, tension-type headache and learning disabilities in a clinic-based sample. J. Headache Pain 2016, 17, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, K.; Sakai, N.; Kimpara, K.; Arizono, S. The effect of physical therapy integrated with pharmacotherapy on tension-type headache and migraine in children and adolescents. BMC Neurol. 2024, 24, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Arafeh, I. Predicting quality of life outcomes in children with migraine. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2022, 22, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hershey, A.D.; Powers, S.W.; Vockell, A.L.; LeCates, S.; Kabbouche, M.A.; Maynard, M.K. PedMIDAS: Development of a questionnaire to assess disability of migraines in children. Neurology 2001, 57, 2034–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyer, G.L.; Merison, K.; Rose, S.C.; Perkins, S.Q.; Lee, J.M.; Stewart, W.C. PedMIDAS-based scoring underestimates migraine disability on non-school days. Headache 2014, 54, 1048–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, W.F.; Lipton, R.B.; Kolodner, K.B.; Sawyer, J.; Lee, C.; Liberman, J.N. Validity of the Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) score in comparison to a diary-based measure in a population sample of migraine sufferers. Pain 2000, 88, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, W.F.; Lipton, R.B.; Dowson, A.J.; Sawyer, J. Development and testing of the Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) Questionnaire to assess headache-related disability. Neurology 2001, 56 (Suppl. S1), S20–S28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayliss, M.S.; Dewey, J.E.; Dunlap, I.; Batenhorst, A.S.; Cady, R.; Diamond, M.L.; Sheftell, F. A study of the feasibility of Internet administration of a computerized health survey: The headache impact test (HIT). Qual. Life Res. 2003, 12, 953–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houts, C.R.; Wirth, R.J.; McGinley, J.S.; Gwaltney, C.; Kassel, E.; Snapinn, S.; Cady, R. Content validity of HIT-6 as a measure of headache impact in people with migraine: A narrative review. Headache 2020, 60, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piebes, S.K.; Snyder, A.R.; Bay, R.C.; Valovich McLeod, T.C. Measurement properties of headache-specific outcomes scales in adolescent athletes. J. Sport Rehabil. 2011, 20, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia 2018, 38, 1–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozge, A.; Sasmaz, T.; Cakmak, S.E.; Kaleagasi, H.; Siva, A. Epidemiological-based childhood headache natural history study: After an interval of six years. Cephalalgia 2010, 30, 703–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kröner-Herwig, B.; Heinrich, M.; Vath, N. The assessment of disability in children and adolescents with headache: Adopting PedMIDAS in an epidemiological study. Eur. J. Pain 2010, 14, 951–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, A.V.; Ashina, H.; Al-Khazali, H.M.; Rose, K.; Christensen, R.H.; Amin, F.M.; Ashina, M. Clinical features of migraine with aura: A REFORM study. J. Headache Pain 2024, 25, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genizi, J.; Khourieh Matar, A.; Zelnik, N.; Schertz, M.; Srugo, I. Frequency of pediatric migraine with aura in a clinic-based sample. Headache 2016, 56, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyer, G.L.; Perkins, S.Q.; Rose, S.C.; Aylward, S.C.; Lee, J.M. Comparing patient and parent recall of 90-day and 30-day migraine disability using elements of the PedMIDAS and an Internet headache diary. Cephalalgia 2014, 34, 298–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Jumah, M.; Al Khathaami, A.M.; Kojan, S.; Husøy, A.; Steiner, T.J. The burden of headache disorders in the adult general population of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: Estimates from a cross-sectional population-based study including a health-care needs assessment. J. Headache Pain 2024, 25, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | N = 96 |

|---|---|

| Age | 14.0 (±3.3) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 63 (66%) |

| Male | 33 (34%) |

| Headache type | |

| Migraine with aura | 10 (10%) |

| Migraine without aura | 50 (52%) |

| TTH | 17 (18%) |

| Combined | 14 (15%) |

| Other | 5 (5.2%) |

| Family history of migraine | |

| Negative | 32 (34%) |

| Positive | 61 (66%) |

| Disease duration (months) | 11.0 (9.0, 15.0) |

| Headache frequency (per week) | 3.00 (1.00, 7.00) |

| Headache intensity | 7.00 (5.00, 8.00) |

| Characteristic | Migraine with Aura, N = 10 1 | Migraine Without Aura, N = 50 1 | TTH, N = 17 1 | Combined, N = 14 1 | Other, N = 5 1 | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 14.9 (2.8) | 13.0 (3.3) | 11.7 (3.3) | 14.8 (2.9) | 12.8 (2.6) | 0.048 |

| Sex | 0.12 | |||||

| Female | 6/10 (60%) | 32/50 (64%) | 10/17 (59%) | 13/14 (93%) | 2/5 (40%) | |

| Male | 4/10 (40%) | 18/50 (36%) | 7/17 (41%) | 1/14 (7.1%) | 3/5 (60%) | |

| Family history of migraine | 0.7 | |||||

| Negative | 4/9 (44%) | 16/50 (32%) | 7/17 (41%) | 3/13 (23%) | 2/4 (50%) | |

| Positive | 5/9 (56%) | 34/50 (68%) | 10/17 (59%) | 10/13 (77%) | 2/4 (50%) | |

| Disease duration (months) | 15.4 (4.9) | 10.8 (4.3) | 8.1 (5.0) | 12.0 (5.0) | 11.0 (3.9) | 0.004 |

| Headache frequency (per week) | 3.00 (2.56) | 3.04 (2.27) | 4.75 (2.52) | 5.43 (2.10) | 3.38 (3.45) | 0.006 |

| Headache intensity | 7.67 (0.87) | 6.71 (1.50) | 5.53 (1.19) | 6.62 (1.45) | 6.00 (1.00) | 0.005 |

| Migraine with Aura | Migraine Without Aura | TTH | Combined | Other | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PedMIDAS score | 69 (69) | 44 (47) | 19 (26) | 59 (36) | 48 (83) | 0.006 |

| PedMIDAS level | 2.80 (1.40) | 2.56 (1.21) | 1.71 (0.99) | 3.21 (0.80) | 2.00 (1.41) | 0.008 |

| HIT-6 score | 65 (4) | 62 (7) | 55 (6) | 63 (5) | 54 (10) | <0.001 |

| HIT-6 level | 3.90 (0.32) | 3.44 (0.95) | 2.47 (1.18) | 3.64 (0.50) | 2.40 (1.14) | <0.001 |

| ID | Age (Years) | Disease Duration (Months) | Headache Frequency (per Week) | Headache Intensity | PedMIDAS Score | PedMIDAS Level | HIT-6 Score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ID | ||||||||

| Age (years) | −0.317 ** | |||||||

| Disease duration (months) | 0.011 | 0.182 | ||||||

| Headache frequency (per week) | −0.196 | 0.150 | −0.142 | |||||

| Headache intensity | 0.107 | 0.219 * | 0.269 * | −0.188 | ||||

| PedMIDAS score | −0.245 * | 0.326 ** | 0.150 | 0.275 * | 0.075 | |||

| PedMIDAS level | −0.280 ** | 0.335 ** | 0.094 | 0.299 ** | 0.059 | 0.964 *** | ||

| HIT-6 score | −0.031 | 0.244 * | 0.225 * | 0.203 | 0.255 * | 0.594 *** | 0.601 *** | |

| HIT-6 level | −0.076 | 0.228 * | 0.168 | 0.121 | 0.236 * | 0.478 *** | 0.498 *** | 0.874 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Genizi, J.; Mansour, R.; Burbara, M.; Gal, S.; Nathan, K.; Kaly, L.; Yaniv, L. The HIT-6 Questionnaire Corresponds to the PedMIDAS for Assessment of Pediatric Headaches. Healthcare 2025, 13, 3158. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233158

Genizi J, Mansour R, Burbara M, Gal S, Nathan K, Kaly L, Yaniv L. The HIT-6 Questionnaire Corresponds to the PedMIDAS for Assessment of Pediatric Headaches. Healthcare. 2025; 13(23):3158. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233158

Chicago/Turabian StyleGenizi, Jacob, Raneen Mansour, Malak Burbara, Shoshana Gal, Keren Nathan, Lisa Kaly, and Liat Yaniv. 2025. "The HIT-6 Questionnaire Corresponds to the PedMIDAS for Assessment of Pediatric Headaches" Healthcare 13, no. 23: 3158. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233158

APA StyleGenizi, J., Mansour, R., Burbara, M., Gal, S., Nathan, K., Kaly, L., & Yaniv, L. (2025). The HIT-6 Questionnaire Corresponds to the PedMIDAS for Assessment of Pediatric Headaches. Healthcare, 13(23), 3158. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233158