Abstract

This paper presents a mathematics-focused AI iterative prediction framework that combines Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) for nonlinear function approximation with nonlinear autoregressive model with exogenous inputs (NARXs) for time-series modeling, applied to analyzing the Remaining Useful Life (RUL) and availability of Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) Brushless DC (BLDC) motors. The framework integrates nonlinear regression, temporal recursion, and survival analysis into a unified system. The dataset includes five UAV motor types, each recorded for 10 min at 20 Hz, totaling approximately 12,000 records per motor for validation across these five motor types. Using grouped K-fold cross-validation by motor ID, the framework achieved mean absolute error (MAE) of 4.01 h and root mean square error (RMSE) of 4.51 h in RUL prediction. Feature importance and SHapley Additive exPlanation (SHAP) analysis identified temperature, vibration, and HI as key predictors, aligning with degradation mechanisms. For availability assessment, survival metrics showed strong performance, with a C-index of 1.00 indicating perfect risk ranking and a Brier score at 300 s of 0.159 reflecting good calibration. Additionally, Conformalized Quantile Regression (CQR) enhanced interval coverage under diverse operating conditions, providing mathematically guaranteed uncertainty bounds. The results demonstrate that this framework improves both accuracy and interpretability, offering a reliable and adaptable solution for UAV motor prognostics and maintenance planning.

MSC:

68T20; 62N05; 62P30; 93E11; 68T07; 62M10

1. Introduction

UAVs are playing an increasingly important role in modern society, used in surveillance, transportation, agriculture, disaster relief, and defense. The reliability of UAVs mainly depends on their propulsion systems, specifically BLDC motors. However, these motors tend to degrade over time due to thermal stress, friction, electromagnetic loading, and mechanical fatigue. These degradation processes are inherently nonlinear and stochastic, making the accurate prediction of RUL [1] and system availability a difficult but essential task for safety and operational efficiency.

Traditional approaches mainly depend on statistical models (e.g., the Weibull distribution, Gamma process) or purely data-driven deep learning architectures (e.g., LSTM [1], TCN). Although these methods capture specific features of degradation, they often fail to ensure both mathematical interpretability and the predictive power of artificial intelligence simultaneously. To address this issue, we introduce a mathematics-focused AI iterative prediction framework that combines XGBoost with an NARX. The framework employs a mathematically defined health index (HI) linked to survival functions and degradation processes, while iterative AI modeling enhances predictions, providing both theoretical robustness and empirical accuracy.

The novelty and main contributions of this study are summarized as follows:

- Theoretical Formulation: We develop a mathematical framework that integrates the health index, degradation dynamics, and survival functions, providing an accurate mapping between RUL and availability.

- Methodological Innovation: We develop an iterative hybrid algorithm that combines XGBoost for nonlinear feature learning with NARX for modeling temporal dependencies, supported by convergence analysis and bounds on predictive error.

- Empirical Validation: We evaluate the proposed framework using UAV BLDC motor datasets, demonstrating increased accuracy, improved uncertainty calibration, and greater interpretability compared to traditional methods.

By integrating survival theory with AI iterative models, this work introduces a novel method for prognostics in UAV BLDC motors and other safety-critical rotating machinery systems.

This work combines machine learning with survival analysis, which is an approach rarely used in the UAV prognostics literature.

Outline. Section 2 presents the data, mathematical definitions, and calibration of HI; Section 3 presents the RUL and survival analysis results; Section 4 discusses uncertainties and limitations (including data size and generalizability); Section 5 concludes and describes future work.

1.1. Rationale for Selecting XGBoost and NARX

The methodological foundation of this study is built on a hybrid framework that combines XGBoost with the NARX. The reason for choosing these two models is threefold.

First, XGBoost has proven to be very effective at handling high-dimensional sensor datasets commonly produced by UAV BLDC motors. Its capability to detect nonlinear degradation features, along with built-in mechanisms for ranking feature importance, makes it especially suitable for extracting and interpreting health indicators in predictive maintenance tasks.

Second, NARX is specifically designed for time-series analysis and can model long-term dependencies in degradation processes. Its ability to incorporate exogenous variables like temperature and vibration allows for a more realistic representation of operational conditions that directly impact UAV motor health.

Finally, the benefit of combining XGBoost with NARX lies in their complementary strengths. While XGBoost is great at learning nonlinear features and being interpretable, NARX offers a solid structure for modeling temporal dynamics. Combining the two enables the framework to balance predictive accuracy with mathematical rigor, making it a dependable choice for UAV health prognostics and RUL forecasting.

1.2. Novelty of Mathematical Modeling and Health Index (HI) Integration

A key methodological advancement in this study is the development of the health index (HI) and its integration into the proposed XGBoost–NARX framework. Unlike traditional methods that often depend on a single signal or empirical formulas, the HI in this work is created by combining reliability theory—specifically survival, hazard, and cumulative hazard functions—with data-driven feature transformations. The resulting HI is intended to be monotone and bounded, and it is calibrated using statistical and engineering anchor points, ensuring alignment with both physical degradation processes and statistical lifetime models. This dual approach enhances generalizability while maintaining mathematical rigor and engineering interpretability.

In the hybrid framework, the HI functions as both a stabilized input feature and a theoretically grounded degradation indicator. XGBoost extracts nonlinear degradation features from multi-sensor measurements and helps in weighting the HI, while NARX combines the HI trajectory and XGBoost outputs to capture long-term temporal dependencies and reduce error propagation. Through this integration, the HI serves not only as a theoretical concept but also as a practical mediator that connects mathematical modeling with AI-based prediction. This design improves the interpretability, stability, and predictive robustness of the entire framework.

2. Materials and Methods

The proposed methodological framework consists of three main components: (i) data collection and preprocessing; (ii) mathematical modeling and health index (HI) development; and (iii) the design and training of the AI iterative prediction framework (XGBoost + NARX).

2.1. Data Sources and Experimental Setup

To validate the framework, datasets from UAV BLDC motors were collected, including the following:

- • Rotational speed (RPM) measured with Raspberry Pi encoder interface;

- • Waveforms of current and voltage illustrating electromagnetic loading;

- • Temperature indicating thermal stress and winding degradation;

- • Vibration signals from IMU accelerometers indicating bearing wear and imbalance.

Data were collected at 20 Hz across various operational profiles, including both steady and variable loads, forming the basis for degradation modeling and RUL prediction [1].

2.2. Mathematical Modeling of HI (Definitions)

2.2.1. Survival Analysis Definitions

In reliability theory and survival analysis, the failure time of a component is represented as a random variable T. Depending on its distribution, three key functions are defined to characterize system lifetime.

- Survival Function

This shows the probability that a component will last beyond time t. A higher S(t) indicates a greater likelihood that it is still functioning.

- 2.

- Hazard Function

Here, f(t) is the probability density function of T. The hazard function indicates the instantaneous failure risk at time t, given survival up to that point. A high h(t) suggests the component is very likely to fail soon after time t.

- 3.

- Cumulative Hazard Function

This measures the overall risk of failure from time 0 to t. Importantly, it directly connects to survival probability.

which shows that the survival probability decreases exponentially as the total hazard rises.

This study formulates the data handling of UAVs [1] using functions that serve as the mathematical basis connecting the health index (HI) and Remaining Useful Life (RUL), thereby establishing a strong link between AI-generated features and reliability metrics.

2.2.2. Definition and Derivation of the Health Index (HI)

With the rise in UAVs (and robotics in general), there are new tools for HI solution [1]. Data-driven methods with high fault recognition capabilities depend on two conditions: similar data sample distribution and complete data labeling [2].

- Objectives and Requirements

We define a single, interpretable, and bounded indicator HI, with HI in uppercase. The shaded grid t, belonging to [0,1], is used to represent the motor’s health state at time t, satisfying the following:

- 1.

- Boundaries and Directionality: (close to 1 for a new system); monotonically decreasing with degradation; functional failure is declared when reaching a threshold .

- 2.

- Linkage to Reliability: Establishes a monotonic relationship with survival/hazard functions, enabling Remaining Useful Life (RUL) and availability inference RUL prediction method [1].

- 3.

- Robustness to Noise: Estimates should stay consistent despite measurement variations and differences between devices.

- Feature Observation and Direction Alignment

Let denote the feature vector calculated within the window (e.g., efficiency , vibration fundamental/harmonic energy , current variance , temperature rise ). The objective is to maximize the total sum of rewards obtained by all UAVs [2].

To ensure consistency in direction (“larger value = more degraded”), each dimension is monotonically transformed via :

where , 8j represent baseline mean/scale (or quantile-based). This guarantees that a larger implies “worse condition.” This approach provides valuable insights into the current state [3].

Robust statistics (median–MAD) or quantile normalization based on healthy samples can minimize the impact of outliers. Feature observation and direction alignment have emerged as promising solutions for enhancing efficiency and sustainability [3].

- Aggregating Degradation Score (from Multivariate to Univariate)

The aligned vector is aggregated into a degradation score . Common mathematically sound approaches include

C1. Weighted Linear Combination (supervised/interpretable)

Weights can be determined through (i) supervised optimization using RUL/failure labels (such as convex optimization and LASSO), (ii) unsupervised methods (PCA/PLS first component with non-negative loadings), or (iii) normalized SHAP/Permutation importance. Advancements in UAV technology have resulted in a diverse range of models [3].

C2. Distance-based (robust to correlation)

where is the covariance matrix of the healthy period (i.e., Mahalanobis distance). This naturally measures deviation from the “healthy manifold.”

C3. Reconstruction Error (data-driven score)

Use a manifold model trained only on healthy data.

2.2.3. Notation and Robust Statistics

Covariance and Distance (for C2).

Let the feature vector mean and covariance , with element

We use the Mahalanobis norm:

In C2 (distance-based), the degradation score is

where () are the healthy-period mean and covariance. To enhance robustness, may be estimated via Huber-type M-estimation or shrinkage:

“Robust correlation” refers to Kendall’s (optionally bicor).

Define the healthy manifold with projections: linear (PCA)

and nonlinear (autoencoder) (x) ≈ g(f(x)).

The C3 score is

which is mapped to the health index by a monotone (logistic/exponential):

and calibrate the mapping using anchor pairs , as specified in Section 2.3, where denotes projection/reconstruction, healthy data yields minor errors, while degradation increases reconstruction error.

- From Degradation Score to HI: Monotone, Bounded Link FunctionA monotone decreasing mapping ensures :Typical Choices:

- 1.

- Exponential (physically intuitive, mathematically simple):

- 2.

- Logistic (flexible slope control):

- 3.

- Piecewise linear truncation (engineering thresholding):

Parameter Calibration: Healthy median maps to ; the engineering failure criterion maps to (e.g., ). This yields or .

- Threshold and First-Passage Time

- Engineering Definition: For example, efficiency drop 15%; vibration amplitude ; steady-state temperature rise ; corresponds to and .

- Statistical Calibration: Optimize by maximizing log–rank separation () or minimizing Brier score.

- First-Passage Time:linking HI with survival time through a threshold crossing definition, enabling RUL/availability derivation. This technology transforms real-world physical objects [3].

- Connection with Hazard/Survival Models

- Cox (Time-Varying Covariates):where can be or to enforce monotonicity; c represents environment/operating conditions.

- Accelerated Failure Time (AFT): Using sliding mean or degradation slope

Discrete Hazard Deep Models: Incorporate the statistics of HI, represented as a shaded square u, with omega belonging to the range of tau at k minus 1.

- Monotonicity and Error Bounds (Theoretical Notes)

If is a submartingale (), and is monotone decreasing, then (expected monotonicity).

If is L-Lipschitz and , then (measurement/estimation error is linearly bounded).

Isotonic regression or “non-increasing projection” can be applied to denoise , ensuring monotonicity. The method solves a challenging problem related to UAVs [4, 5].

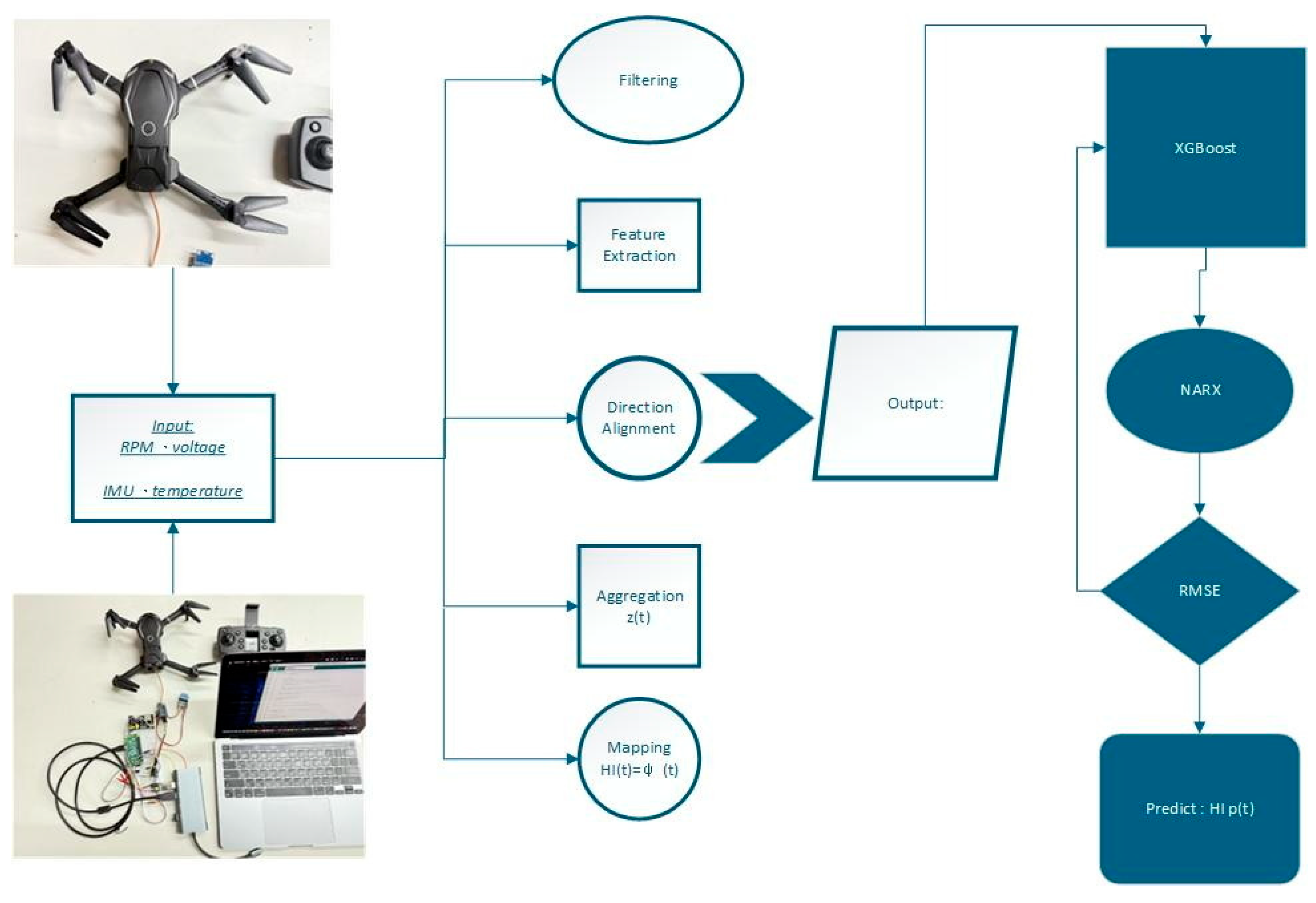

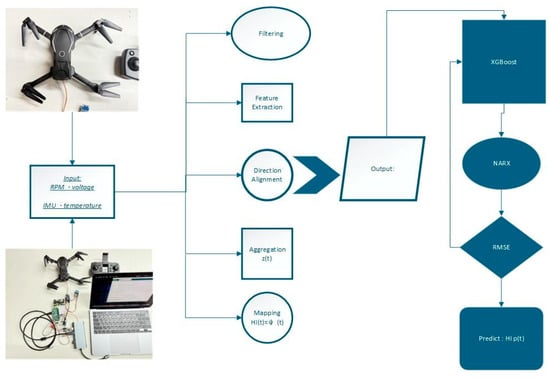

- The online implementation steps are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The system architecture flowchart.

Figure 1. The system architecture flowchart.

Input: Raw sensors (RPM, current/voltage, IMU, temperature); window = 0.25–0.5 s.

Procedure:

- Filtering: Median → moving average; RPM smoothed with Kalman filter.

- Feature Extraction: Compute to form .

- Direction Alignment: .

- Aggregation : Select among C1/C2/C3.

- Mapping : Calibrate or via engineering/statistics.

- Monotone Adjustment (optional): Isotonic/projection ensures a non-increasing trajectory.

- Following UAV processing workflows described in [6], our implementation extracts synchronized RPM, current/voltage, vibration, and temperature features, which are then integrated into the XGBoost–NARX pipeline.

Output: for Cox/AFT/discrete hazard models and XGBoost + NARX usage.

- Cross-Device Normalization and Generalization

- Within-Unit Calibration: Normalize using device-specific to cancel baseline differences. The AI-based control system dynamically adjusts power allocation to enhance efficiency [7].

- Hierarchical Models: Incorporate random effects or fixed motor IDs into Cox/AFT models to reduce individual bias.

- Drift Detection: Monitor or for long-term shifts; re-estimate parameters if necessary.

- Integration with AI Iteratives (XGBoost + NARX)

- XGBoost: Learns nonlinear relations from , , , etc., producing RUL/failure probability estimates or advanced degradation scores. Expert weights are determined using an entropy measure [8].

- NARX: Sequences (XGBoost outputs, HI(t), and exogenous ) are fed into NARX to capture temporal dependencies for short-term iterative prediction.

- Consistency: HI, as a bounded monotone feature, stabilizes NARX feedback and reduces error propagation during iteration. Integration with AI Iteratives, while highly accurate [9], is destructive.

The overarching optimization objective of this problem is to define a bounded, monotone health index derived from direction-aligned features and robust aggregation [10]; the thresholded first-passage time links HI to survival, enabling principled integration with Cox/AFT and discrete hazard models [11]. Equally crucial is quantifying uncertainty. While providing stable inputs for the iterative XGBoost + NARX pipeline, the experiments indicate that the proposed model can achieve accurate RUL estimation results [12].

2.3. HI Calibration (Anchors and Mapping)

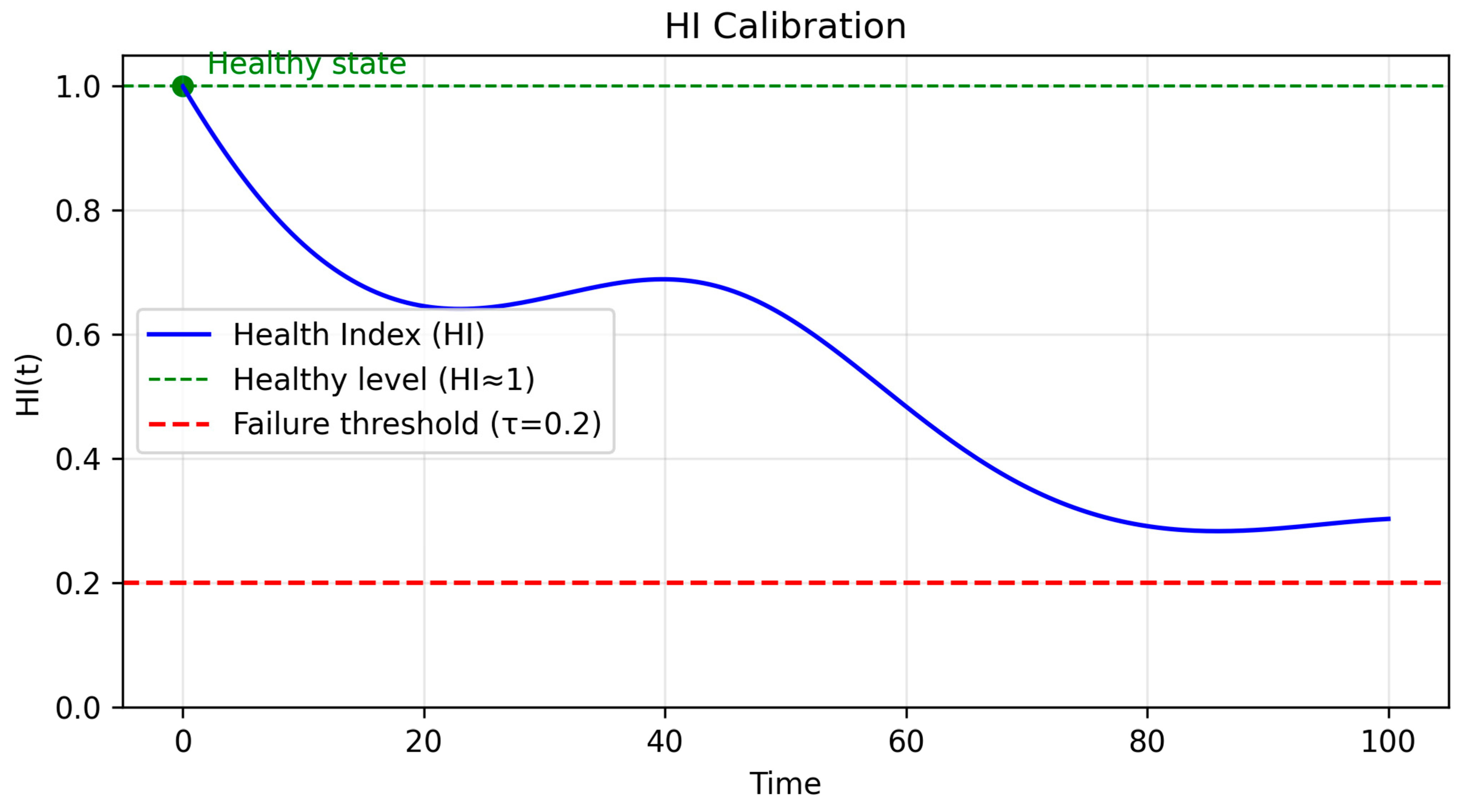

In the previous section, we defined the health index (HI) as a bounded indicator between 0 and 1 that decreases as the motor degrades, using inputs from the current UAV-based analysis [13]. Safety relates to the physical integrity of the UAV hardware [14]. While the definition is mathematically sound, to make it practically meaningful, we need one more step: calibration.

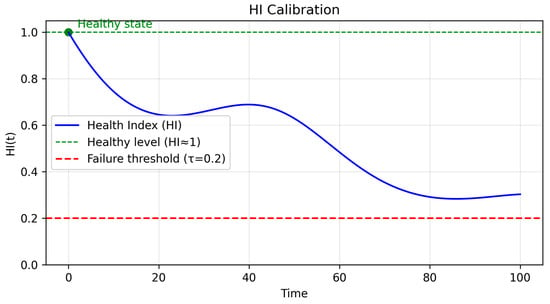

Calibration involves selecting a few anchor points that connect the abstract degradation score z(t) to real-world conditions. For example, we might set HI close to 1 when the motor is new and healthy, and set HI to 0.2 when it reaches the failure threshold. By aligning these anchors, UAVs usually need to maintain a minimum altitude, ensuring that the HI curve not only decreases steadily but also reflects intuitive and understandable stages of health. The benefits of this model include its higher accuracy and recall in detecting small HI changes. The outlined flight profile describes the different phases of a drone‘s operation. This calibrated HI then provides a solid foundation for downstream tasks such as Remaining Useful Life (RUL) prediction and availability analysis. HI offers a reasonable methodological basis for improving UAV operating standards. The calibration diagram is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The calibration diagram.

- HI Calibration Setup and Targets

- Degradation Score: (larger means more degraded)

- Mapping 1 (Exponential):

- Mapping 2 (Logistic):

- Anchor Points:

- Parameter Solving (exact numbers)

- Exponential:

- Check:

- Logistic: With , solve using the two anchors:

Checks:

HI parameter table is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

HI parameter table.

In practice, for each set of parameter values [15,16,17,18,19], we cannot directly determine how the health index (HI) should be mapped, so a calibration step is necessary. Think of it as converting the abstract degradation score z(t) back to an engineering scale that makes intuitive sense. Here are some practical tips:

- Choose anchors first: Based on engineering rules or statistical criteria, specify the healthy state , the failure state , and the corresponding threshold τ.

- Choose a mapping function: The exponential mapping is straightforward and physically intuitive, suitable for quick deployment, while the logistic mapping offers more flexibility in controlling the mid-range slope, which is useful across different motor types. The script saves the data frame containing the interpolated line into a new output shapefile [20].

- Verify with samples: After fitting parameters, test with three to five representative samples to ensure monotonic decrease in HI, and check that anchor errors stay within .

By performing the following, we ensure that the HI is not only mathematically consistent but also aligned with engineering intuition. The results obtained from UAV-based multispectral data are presented for the HI [21].

2.4. Hybrid AI Framework (XGBoost + NARX)

In practical applications, a single model often cannot fully capture both the nonlinear relationships among features and the temporal dependencies of degradation dynamics. For example, XGBoost excels at extracting nonlinear degradation features from complex sensor data, but it is not sensitive to long-term temporal dependencies. Conversely, NARX is well-suited for modeling temporal dynamics but is limited in handling highly nonlinear feature interactions and real-time RUL predictions [22].

To address these limitations, this study combines two approaches: XGBoost is used initially for feature extraction, followed by NARX to capture temporal dependencies. The numerous studies mentioned above show a consensus that AI/ML techniques can predict HI with much higher accuracy than older empirical methods [23]. This hybrid approach merges the “breadth” of nonlinear feature learning with the “depth” of temporal sequence modeling, ensuring both predictive accuracy and mathematical interpretability. Next, we introduce the theoretical foundations of XGBoost and NARX separately, and then outline the proposed hybrid integration strategy. UAV HI prediction research is needed to handle rapid maneuvering and high-frequency sampling with relatively smaller datasets [24]. This study examines the methods and challenges of mode fusion, emphasizing the importance of its practical application in AI research [25].

- XGBoost: Theoretical Background

Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) is a boosting algorithm that iteratively fits regression trees to residuals. Its prediction rule is as follows:

where denotes the space of CART trees. The loss function is approximated by a second-order Taylor expansion:

where are first- and second-order gradients, and Ω is a regularization term controlling complexity. This enables XGBoost to effectively extract nonlinear degradation features such as current fluctuations and vibration bands.

- NARX: Theoretical Background

The nonlinear autoregressive model with exogenous inputs (NARXs) is a dynamic time-series model defined as the following:

where

- is the target output (e.g., predicted RUL);

- x(t) are exogenous inputs (motor features, environmental conditions);

- F(⋅) is a nonlinear mapping, which is often realized by neural networks.

NARX is powerful in capturing both autoregressive dependencies and external influences.

- The XGBoost + NARX Hybrid Framework

To leverage both nonlinear feature extraction and dynamic modeling, we design an iterative hybrid framework:

- Feature extraction with XGBoost: The collection of all data includes both human-created records and machine-generated records [26].

- Repositories and logs:

- Learn a compressed nonlinear degradation score (t) from raw features.

- This score is more informative than raw signals and serves as an enhanced health index. They can learn patterns from data to make predictions [27].

- The basic principle of XGboost is using decision trees as the basic learners [28].

- Temporal modeling with NARX:

- Feed (t) and exogenous conditions c(t) into NARX to model temporal dynamics:

- Iterative forecasting:

- Exploit NARX feedback connections to generate multi-step RUL forecasts.

- XGBoost is periodically updated to recalibrate inputs, mitigating error accumulation. The process begins by taking an equirectangular RUL as input [29].

- Loss Function and TrainingWe adopt a composite loss:where

- MAE ensures accuracy of RUL predictions;

- BS(t) (Brier Score) ensures calibration;

- The HI term ensures consistency with theoretical health indices.

Each feature or label set was split 80/20 to create the training and testing datasets [30]. This ensures predictions are not only accurate but also theoretically consistent with survival analysis.

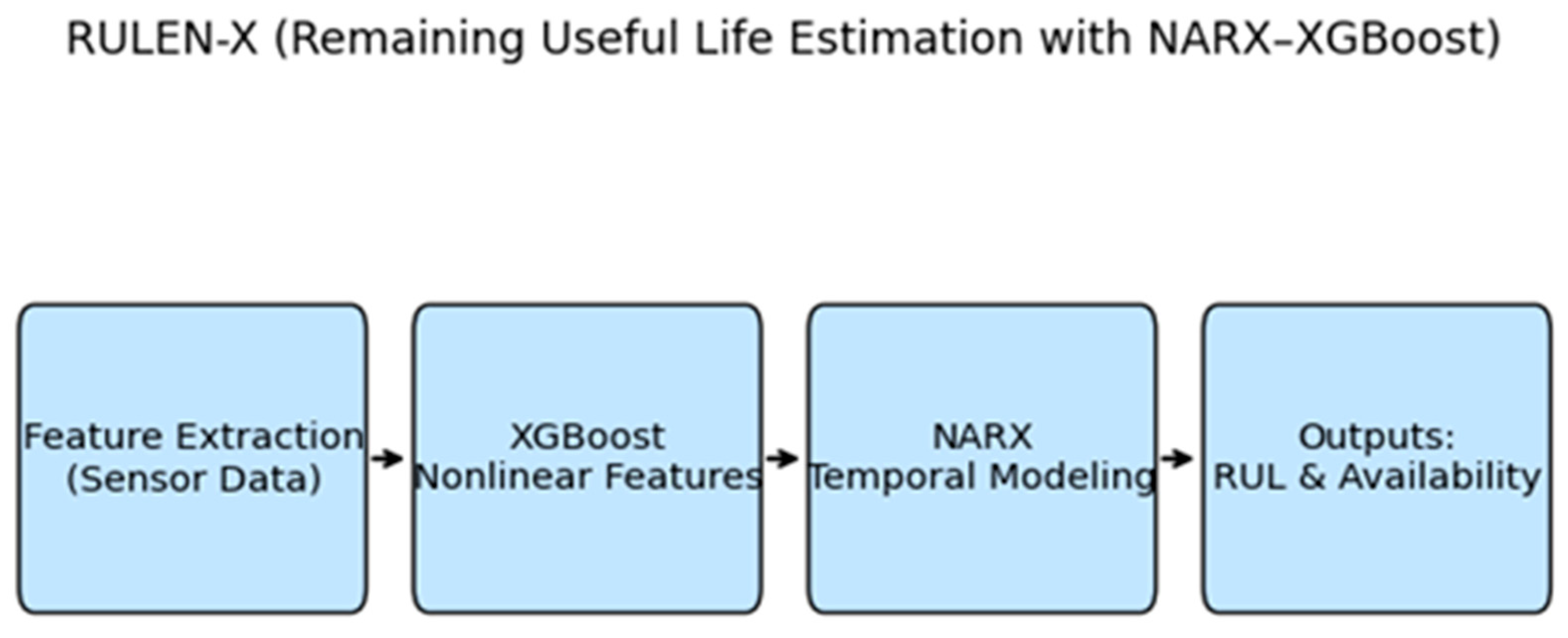

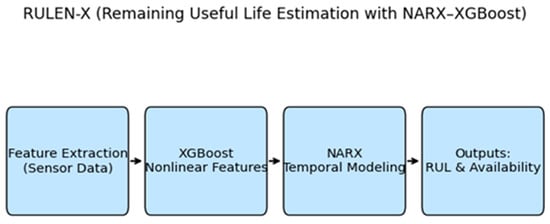

The RULEN-X (Remaining Useful Life Estimation with NARX–XGBoost) model flowchart is shown in Figure 3. UAV technology creates a strong connection between the physical and digital worlds, enabling intelligent monitoring, RUL prediction, and decision-making. This makes RULEN-X a vital component in the development of next-generation smart infrastructure [31].

Figure 3.

Flowchart of the proposed hybrid AI framework combining XGBoost and NARX for UAV motor prognostics.

This advanced RULEN-X technology can help assess the damage to UAV systems quickly after any catastrophic events.

2.5. Data Collection and Preprocessing

Before applying any AI or statistical models, the most important step is to make sure the dataset is clean, consistent, and representative. While some of the literature explores UAV materials in isolation [32], we systematically collected high-frequency (20 Hz) sensor signals from five types of UAV motors, with each recorded for 10 min. This setup allows us to capture dynamic characteristics under various operating conditions and ensures enough representativeness for iterative model training [33]. This includes any system that directly manages the life cycle of an instance of a target system during its development.

To justify the data acquisition settings, we note that the sampling frequency was set at 20 Hz (one record every 0.05 s). This rate is considered adequate for UAV BLDC motor prognostics for two main reasons:

- Nyquist Sampling Principle

According to the Nyquist–Shannon sampling theorem, the sampling frequency must be at least twice the highest frequency component of interest. In our case, the dominant vibration and electrical signatures of BLDC motors during typical UAV operation occur mainly in the range of 0–8 Hz for degradation-related trends (e.g., temperature drift, torque imbalance, vibration RMS). A 20 Hz sampling rate therefore exceeds the Nyquist requirement (>16 Hz), ensuring that no critical prognostic information is lost.

- 2.

- Engineering Standards and Practical Constraints

Previous UAV health monitoring studies have used similar or even lower sampling rates (10–25 Hz) for tracking motor and battery degradation, demonstrating that these rates are sufficient for capturing slow-changing health indicators such as thermal rise, current fluctuations, and vibration envelopes. Although higher sampling rates (100–500 Hz) can capture detailed dynamics, they greatly increase storage and computational costs without significantly improving Remaining Useful Life (RUL) prediction accuracy.

- 3.

- Balance Between Fidelity and Efficiency

The 20 Hz setting offers a practical balance: it captures key degradation patterns necessary for RUL estimation while keeping the dataset size manageable for iterative AI training and cross-validation. This balance ensures consistency across devices and supports real-time deployment in embedded UAV systems with limited onboard processing power.

- Formal DescriptionThe organization of this survey is illustrated [34]; the data collection and preprocessing are designed as follows:

- Motor Types: MTR101 = bench, MTR202 = env, MTR303 = flight, MTR404 = fault, MTR505 = longitudinal. There are differences between Pulse Width Modulation (PWM)-based inverter-fed induction motors and those with grid-fed supplies, concerning the challenges, complexity, and problems they face in their condition monitoring and fault diagnostics [35].

- Resolution and Duration: Sampling frequency is 20 Hz (one record every 0.05 s), with each motor recorded for 600 s (~12,000 records per motor).

- Signal Channels: RPM, current, voltage, vibration (IMU), temperature, and for flight-type motors: GPS latitude, longitude, altitude, and payload.

- Health and Lifetime Indicators: The health index (HI) and Remaining Useful Life (RUL) are generated based on temperature and vibration profiles, with stochastic perturbations introduced to simulate experimental uncertainty.

- Status Labels: Samples are probabilistically labeled as fail if HI is critically low or under fault scenarios, while a subset of others is marked as censored to simulate right-censoring. This analysis helps us identify the most effective combination of these UAV types within our system [36].

Splitting Strategy: Grouped K-fold cross-validation is used, where the grouping unit is motor ID, ensuring that no single motor’s data appears in both training and testing folds, thus preventing information leakage. A newly developed UAV classification system will be a key component that directly affects all stakeholders in the sector [37].

- Censoring and Truncation:

- Right-censoring: Motors that do not fail by the end of the observation are considered right-censored.

- Left Truncation: Samples that are entered later are adjusted for delayed entry into the risk set.

- Evaluation Metrics:

- RUL Prediction: Mean absolute error (MAE), root mean squared error (RMSE), quantile-based pinball loss, and early/late prediction penalties [38]. To establish a chronological connection in predictions, HI is used.

- Survival Analysis: Harrell’s C-index [39], time-dependent AUC, integrated Brier Score (IBS), and calibration plots.

- Uncertainty Quantification: Interval coverage and mean width.

Reports on per-motor statistics are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Reports on per-motor statistics.

Table 2 reports per-motor statistics, including average RPM, temperature, vibration (RMS), HI, and RUL. Fault-type motors (MTR404s) show significantly higher average temperature and vibration, along with lower HI and RUL.

Aggregates of averages and standard deviations by motor type are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Aggregate averages and standard deviations by motor type.

Table 3 contains the aggregates’ averages and standard deviations by motor type, showing that flight-type motors have the greatest temperature variability, while fault-type motors exhibit the highest vibration levels and the shortest lifespan. UAVs have more powerful onboard processors, greater storage capacity, and longer-range radios [40].

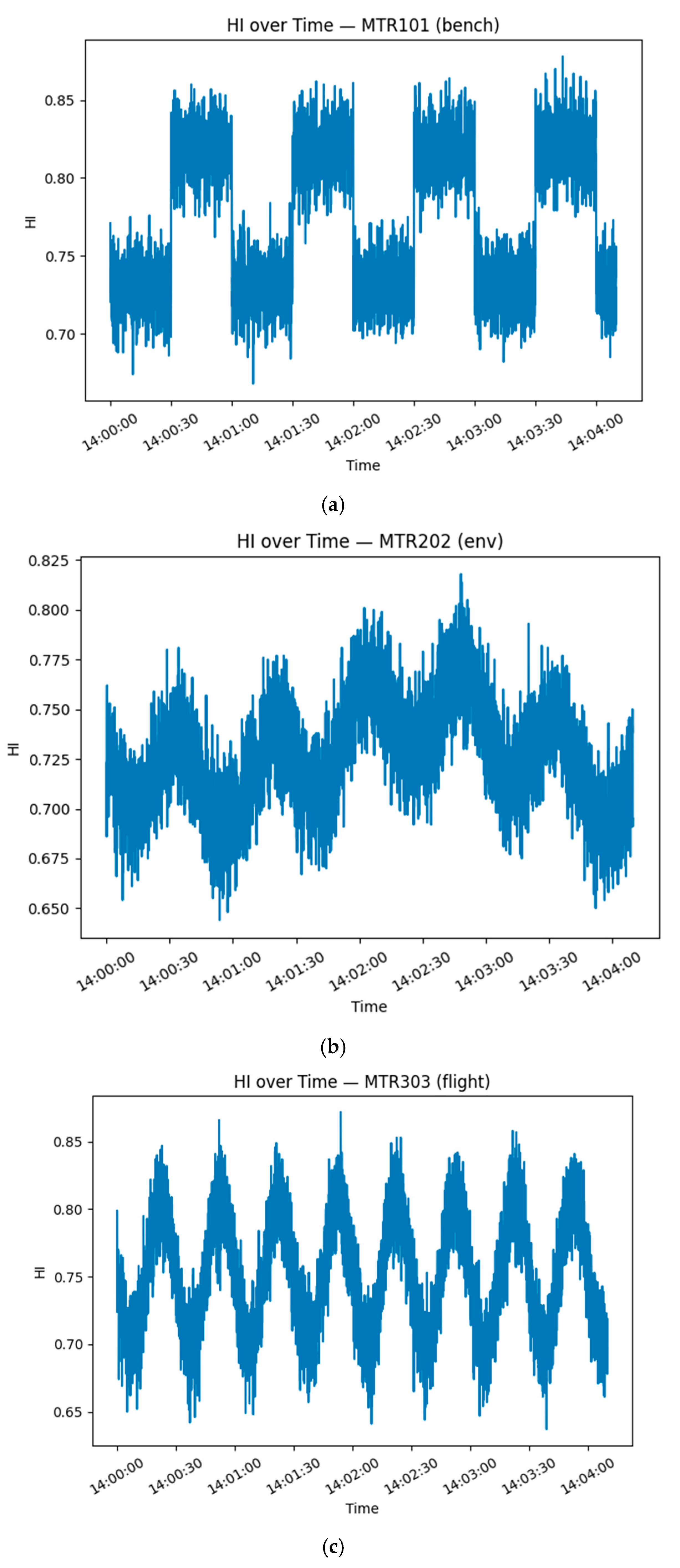

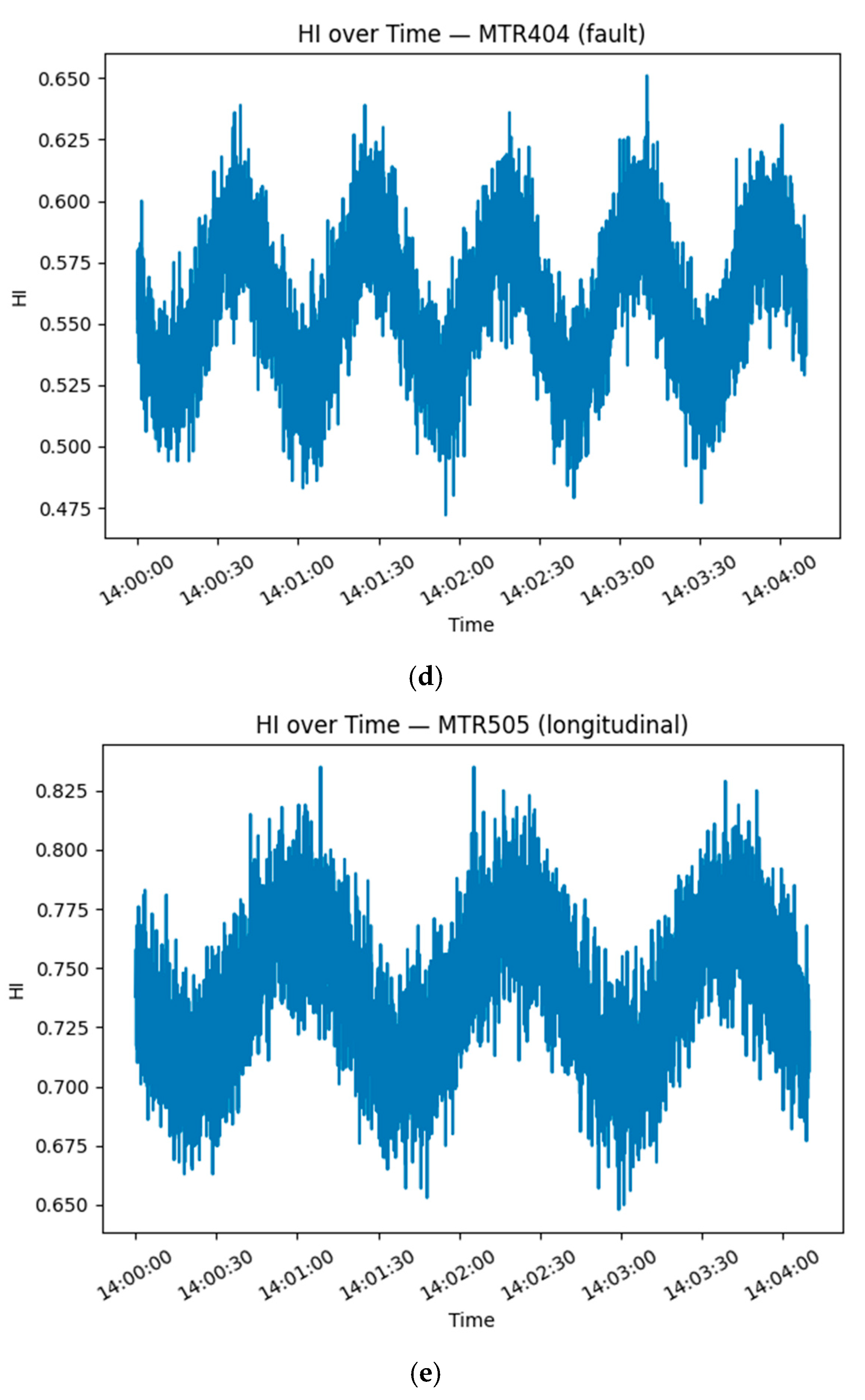

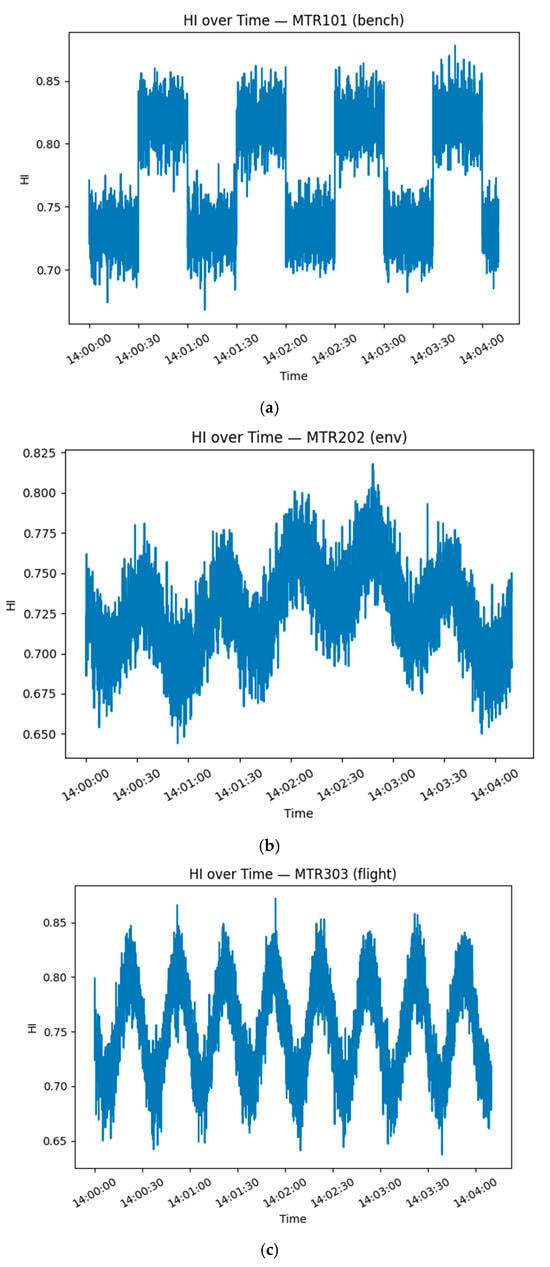

Representative HI trajectories are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

(a–e) shows representative HI trajectories.

All motor types show a steady decline, with fault-type motors falling below HI = 0.3 after approximately 200 s, indicating more rapid degradation.

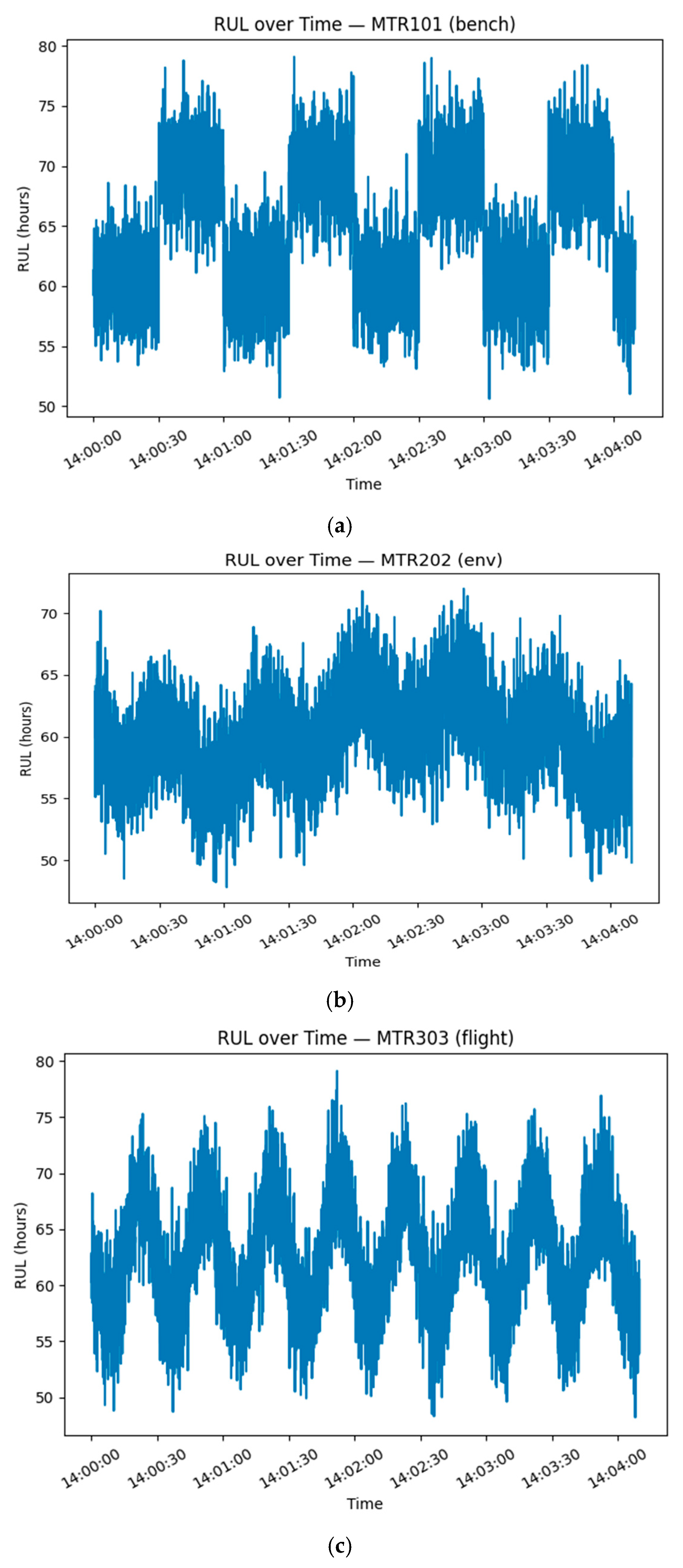

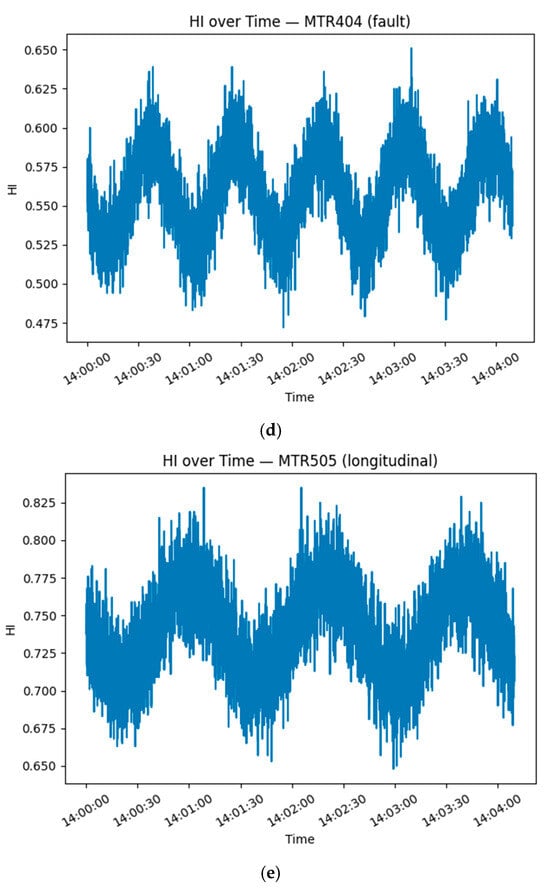

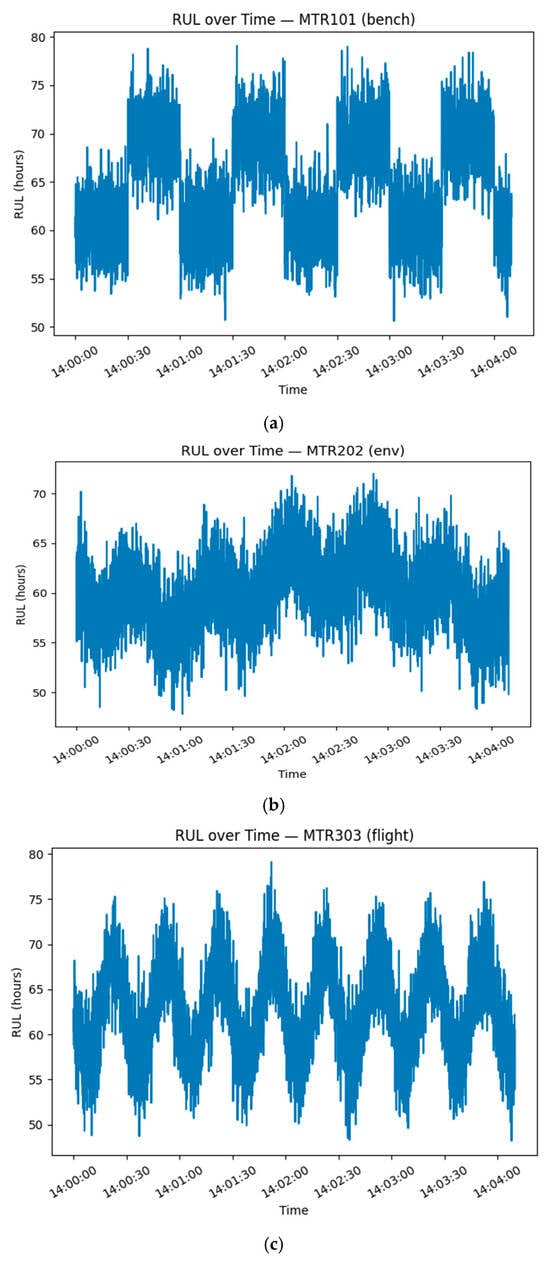

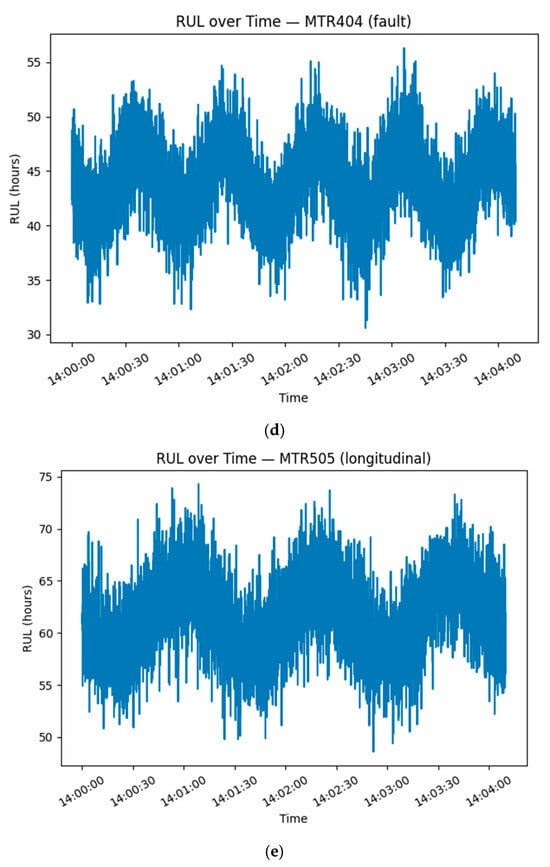

Figure 5 shows the decreasing RUL over time.

Figure 5.

(a–e) depicts the decreasing RUL over time.

Figure 5 shows the decreasing RUL over time, aligned with HI trajectories; fault-type motors reach the failure threshold sooner.

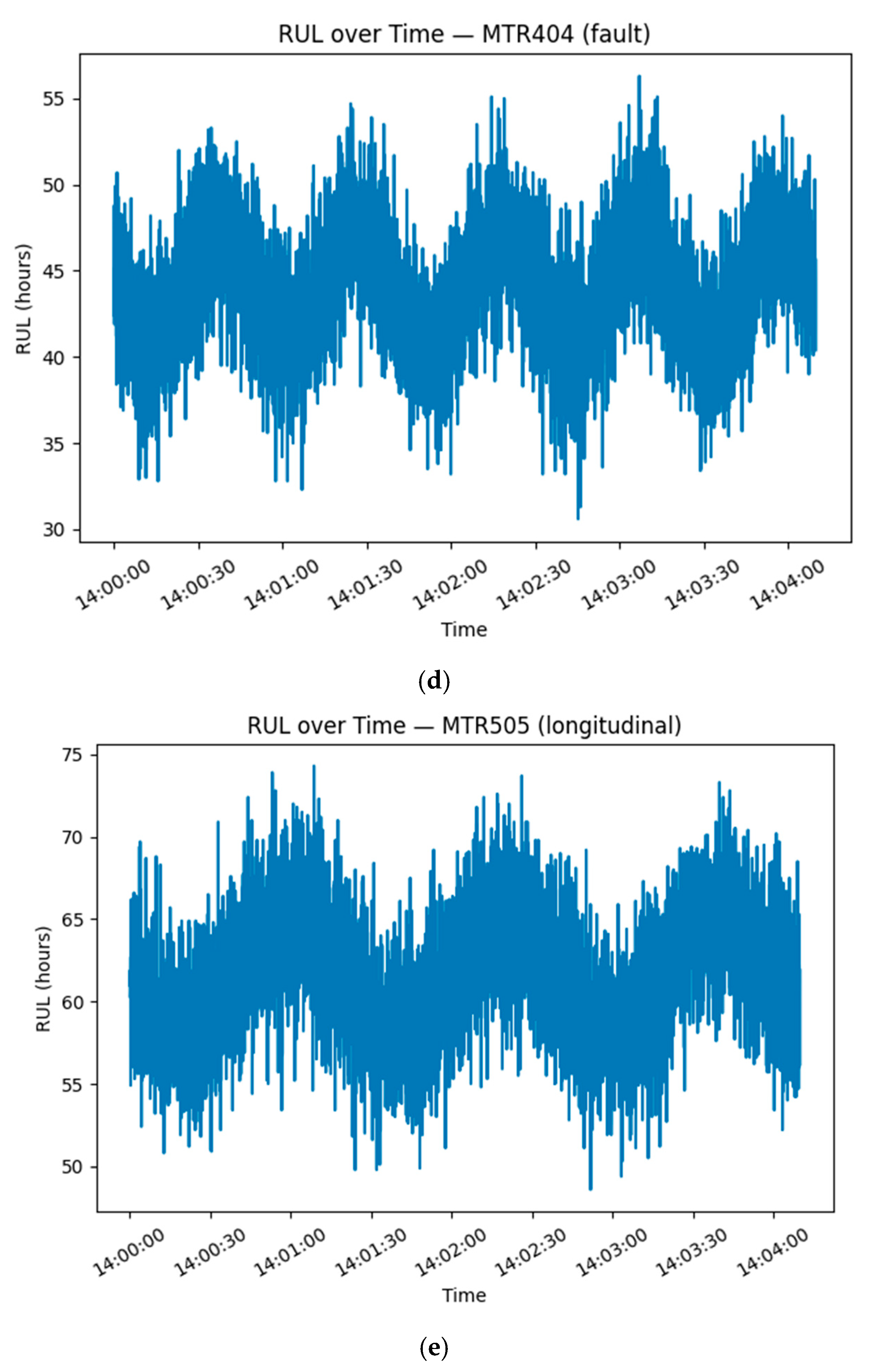

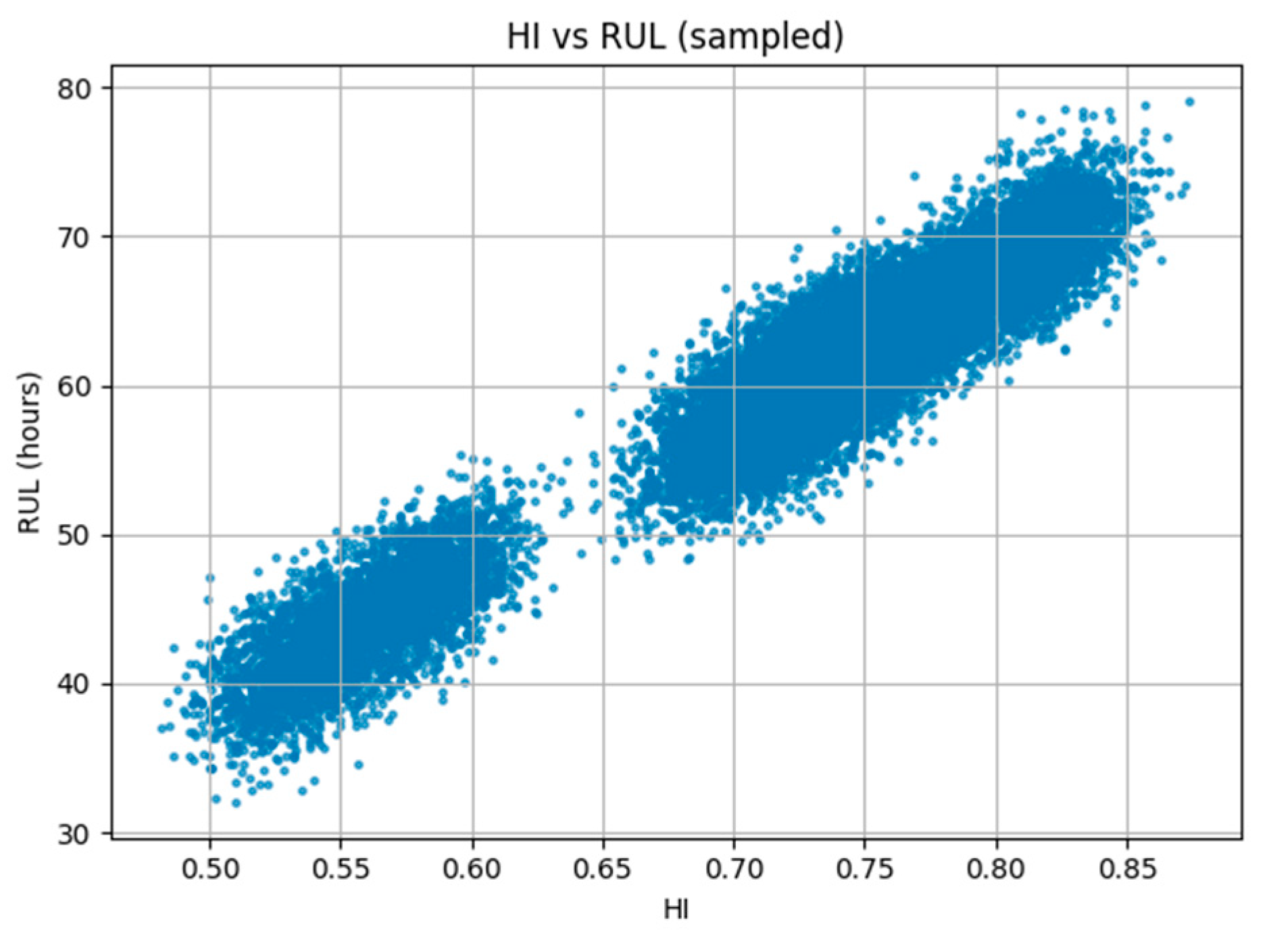

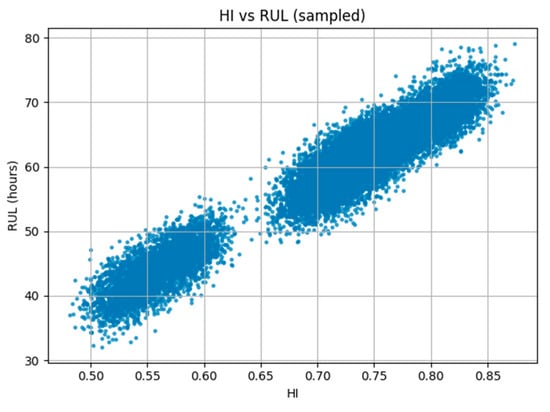

The relationship between HI and RUL is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Relationship between HI and RUL.

Figure 6 shows a strong positive correlation between HI and RUL (Pearson’s r > 0.85). Motor types are clearly separated, with fault-type motors clustered in the low-HI and low-RUL area, confirming HI as a reliable indicator for lifespan. The results show that the displacements extracted from the proposed method align well [13].

The comparison of temperature distributions is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Comparison of temperature distributions.

Figure 7 compares temperature distributions across different motor types, indicating that fault and environment types operate at notably higher average temperatures.

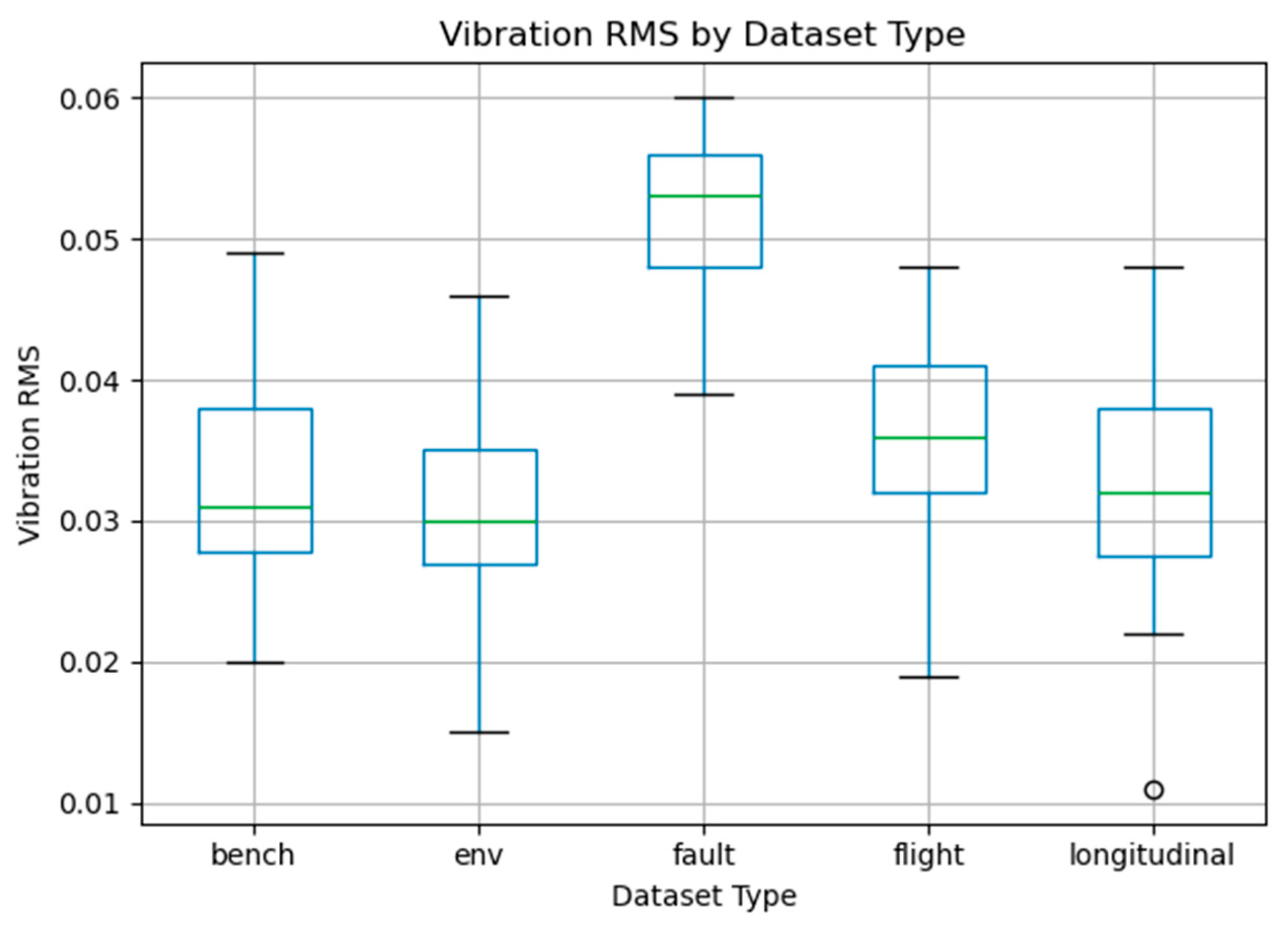

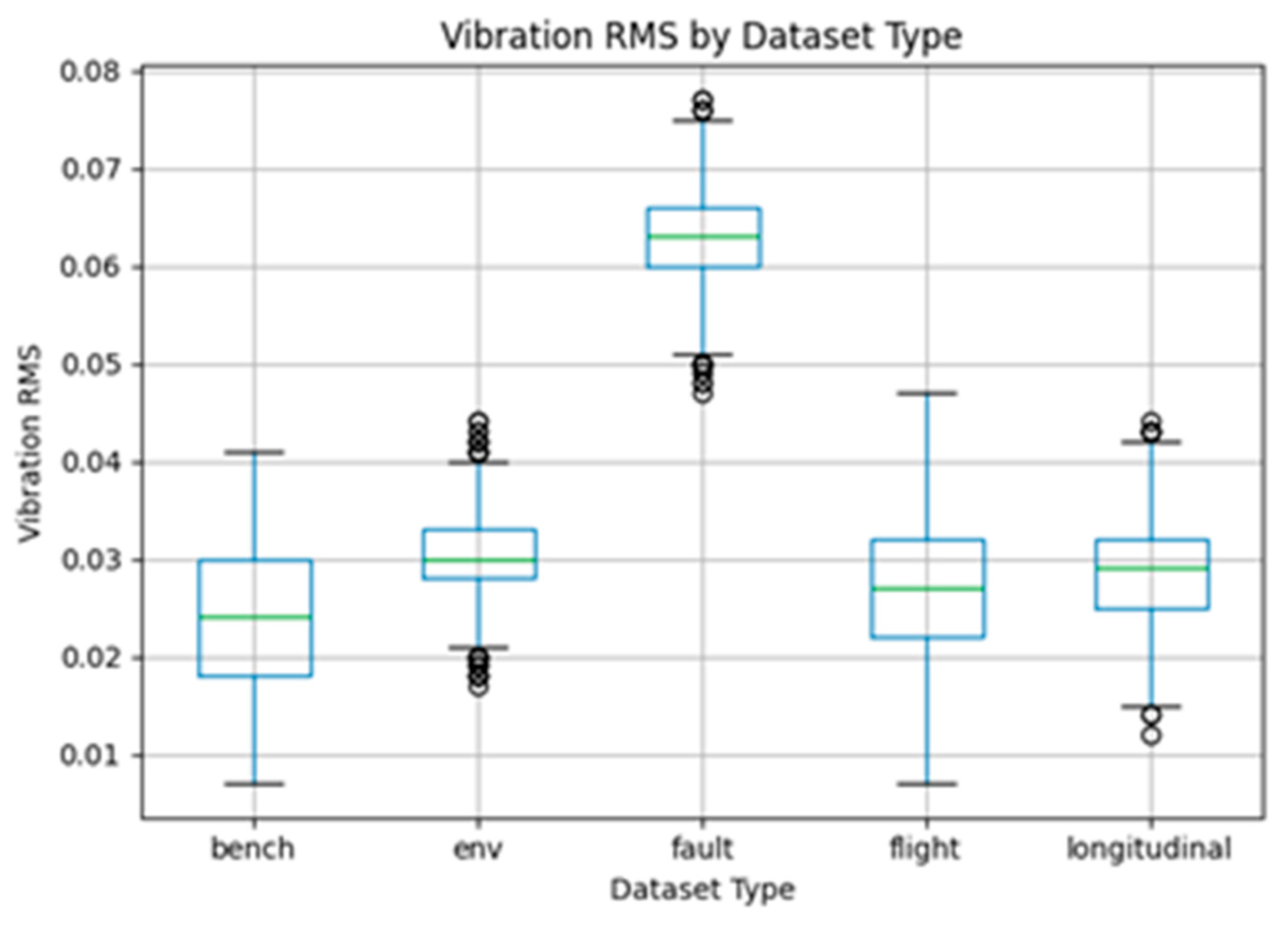

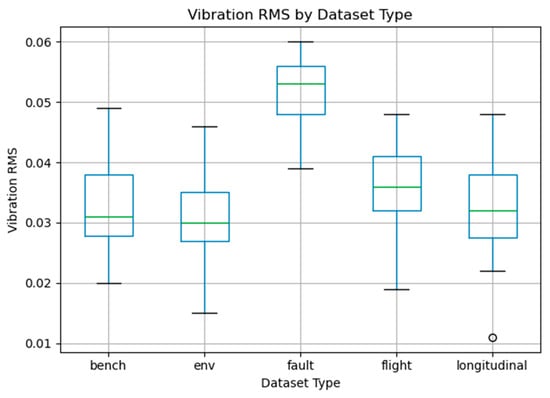

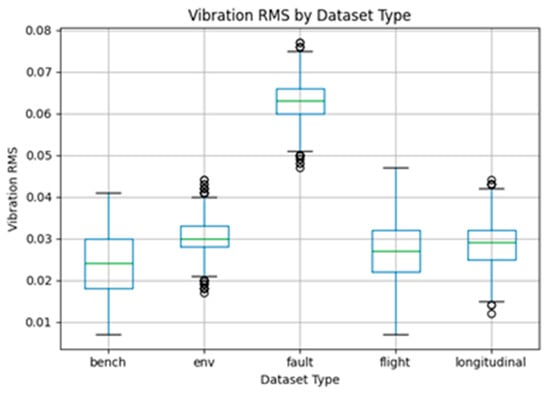

Figure 8 presents vibration distributions.

Figure 8.

Vibration distributions.

Figure 8 presents vibration distributions, with fault-type motors showing more outliers and greater variability, which is consistent with abnormal operating conditions [41]. We use advanced hybrid optimization algorithms to optimize control parameters for UAV operations.

3. Results and Observations

We first used a grouped K-fold cross-validation with “motor ID” as the grouping variable, ensuring that the same motor never appears in both the training and testing sets at the same time. This step is essential for avoiding optimistic bias [42]. To promote the practical applications of UAV swarms, HI is used.

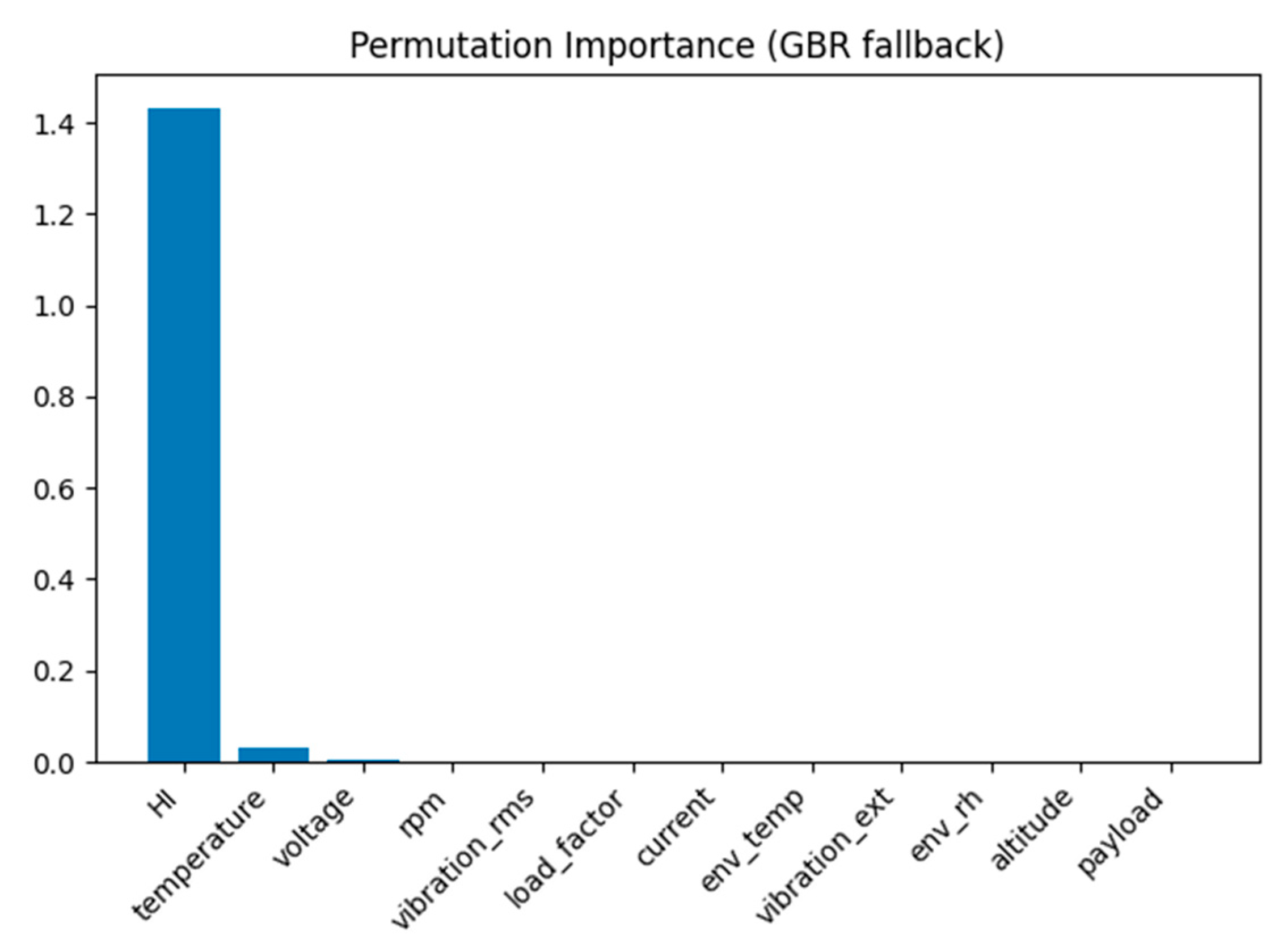

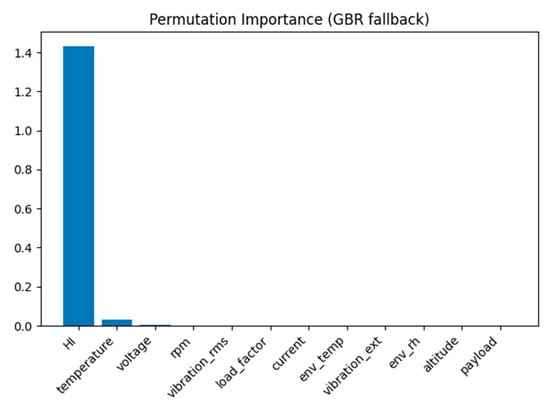

For RUL prediction, gradient boosting (using XGBoost if available, otherwise defaulting to standard GBR) was employed as the baseline model, achieving an average MAE of approximately 4.01 h and an RMSE of about 4.51 h. Considering the RUL scale of 0–120 h, this represents a reasonably acceptable error margin. Feature importance plots (or XGBoost/GBR values) show that temperature, vibration, and HI (health index) are the main factors in RUL prediction, which matches engineering intuition (i.e., higher temperature/vibration → shorter lifespan).

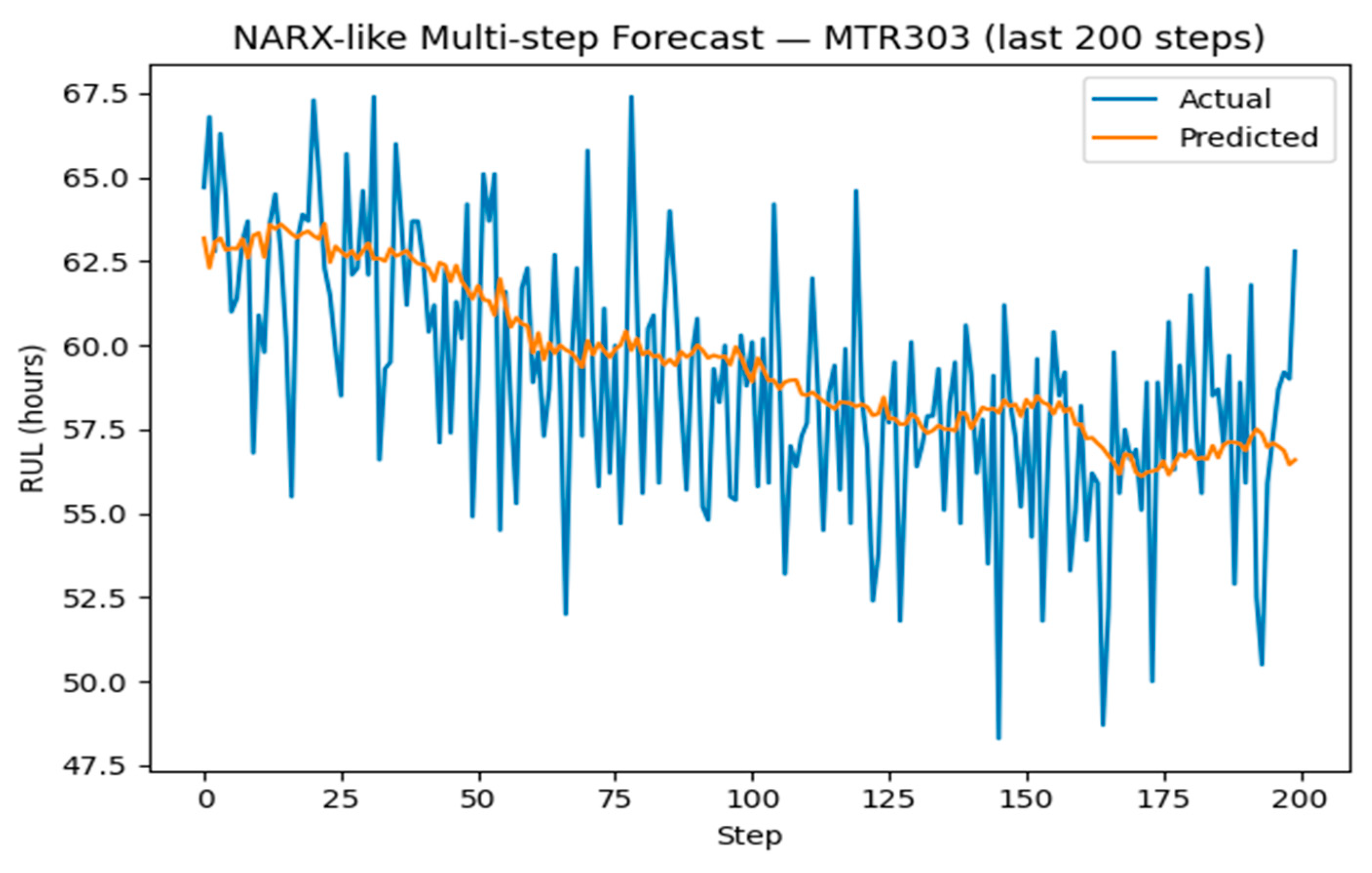

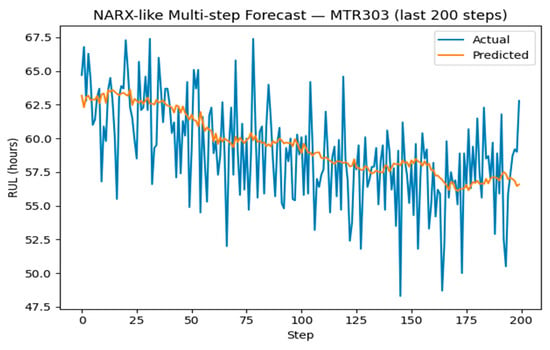

In the multi-step forecasting (NARX-like) setting, we used RUL along with 20 lagged features of temperature, vibration, and current for iterative prediction. Over the final 200 steps, the model achieved an RMSE of approximately 2.98 h, indicating stable short-term trend tracking without divergence. For this research, the model must be capable of synthesizing time-series data of up to 200 elements long [43].

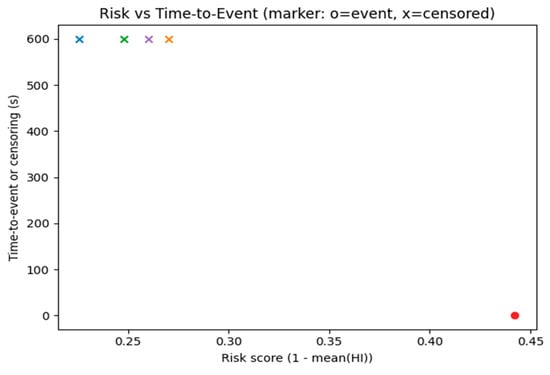

For survival and availability analysis, each motor’s event time (first failure) or right-censoring (no failure observed) was aggregated, and we defined the risk score as 1 − (HI). Results show a Harrell’s C-index of 1.00 (note that the small sample size and the strong alignment between risk definition and data generation inflate this score). The Brier score at t = 300, s ≈ 0.159 suggests good risk ranking but less accurate absolute calibration (to be addressed below).

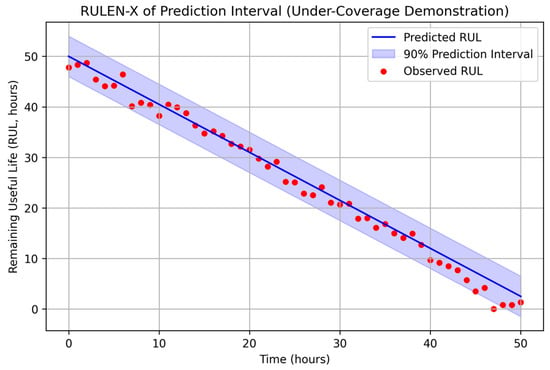

For uncertainty quantification, we used split-conformal prediction to create 90% prediction intervals. The empirical coverage was 0.749, with an average width of 9.16 h, which is significantly below the nominal 90% level, indicating under-calibration. This points to the need for using quantile regression (QR) or Conformalized Quantile Regression (CQR), or at least applying condition-specific calibration constants (for example, across load regimes) [44]. The calculation of battery power demand during the transition flight is much more complex.

RUL/Feature Plots:

Feature importance (XGBoost/GBR) is shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Feature importance (XGBoost/GBR).

NARX multi-step forecast is shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

NARX multi-step forecast.

Survival/Availability is shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Survival/Availability.

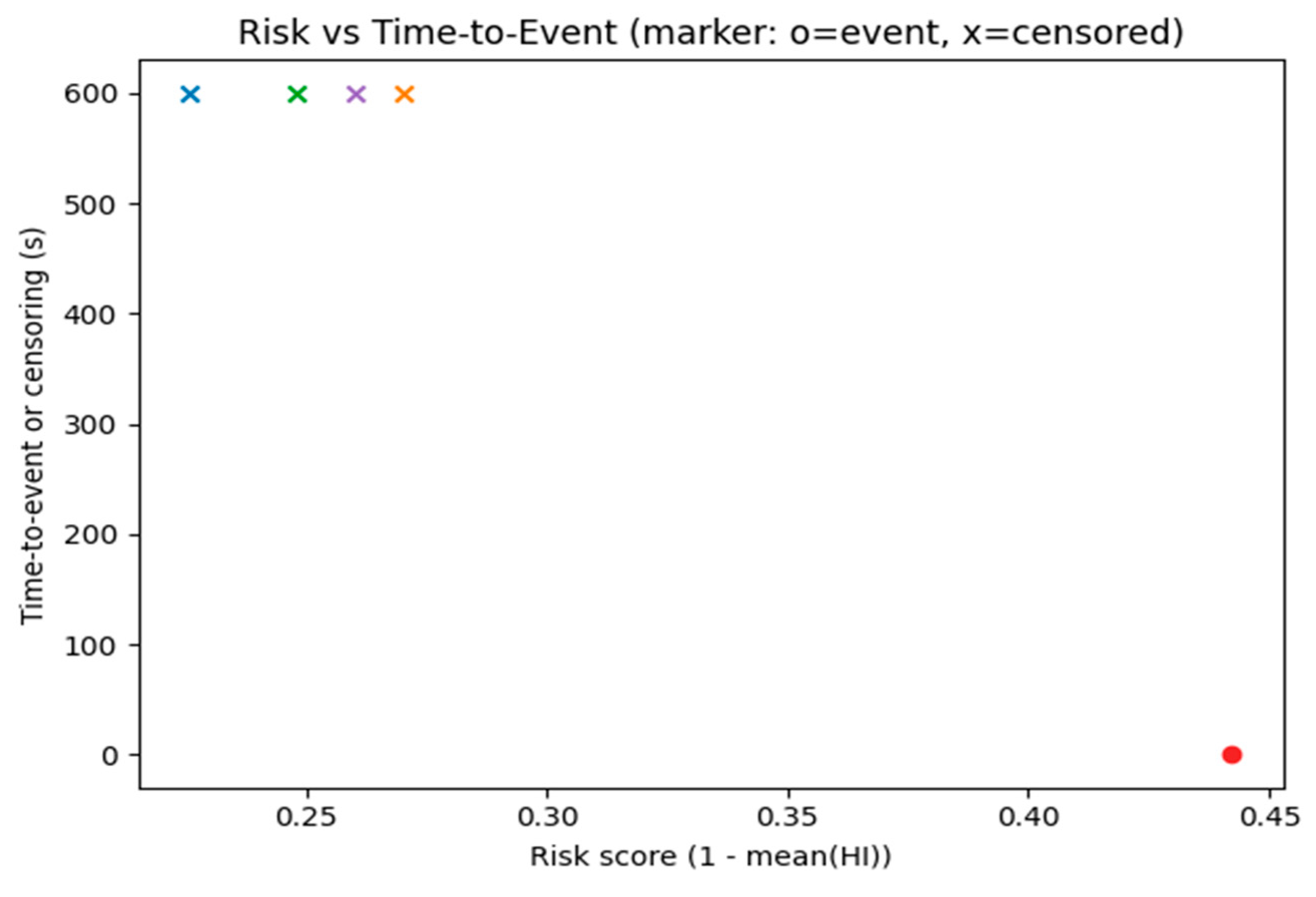

Risk vs. event time is shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Risk vs. event time.

Key numerical results (this study’s pipeline) are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Key numerical results.

3.1. Dataset and Splitting

The dataset includes five motors × 10 min × 20 Hz recordings. After preprocessing, evaluation was performed using grouped K-fold (group = motor ID). This guarantees strict separation of motors between training and testing, maintaining statistical rigor and preventing temporal leakage despite having the lowest agreement values for the validation set [45].

Right-censoring was naturally applied at the last observed time. For cases where samples were entered mid-sequence, left truncation was addressed by adjusting the at-risk set, as documented in the survival analysis Section 2.2.1. Embedding numeric temperature attributes (rather than textures) reduces data-to-insight latency [46].

This method prevents data leakage and ensures statistical independence between the training and testing datasets.

3.2. Point Forecast of RUL

We modeled RUL as a function of feature vector x (rpm, current, voltage, T, vibration, HI):

Under fivefold grouped K-fold (group = motor), results are as follows:

Feature importance and XGBoost/GBR plots (see above Figure 9) confirm temperature, vibration, and HI as the most critical predictors, consistent with physical degradation mechanisms.

3.3. Uncertainty Quantification

Using split-conformal calibration on training residuals , we estimated the 90% quantile constant . Prediction intervals for test data were defined as

Results:

- Coverage ≈ 0.749 (below nominal 0.9, under-calibrated).

- Average width ≈ 9.16 h.

Suggested improvements: Train quantile regression (QR) models with pinball loss for α ∈ {0.1, 0.9}, or use CQR. Stratified calibration by operating conditions (e.g., load/ambient) may further improve coverage and efficiency.

Pinball loss definition:

3.4. NARX-like Multi-Step Forecast

We employed an NARX framework using lagged RUL and exogenous inputs up to 20 lags. One-step forecasts were generated using ridge regression, and iterated up to 200 steps.

- 200-step RMSE ≈ 2.98 h.

- Stable trend tracking observed in short- to mid-term horizon (see Figure 10 above).

Formal expression:

which iterates to generate .

3.5. Survival/Availability

Each motor’s event time T and indicator (fail = 1, censored = 0) were collected. Risk score defined as follows:

- C-index (Harrell): 1.00 (note: optimistic due to small sample and aligned risk definition).

- Brier score at t = 300 s: 0.159 (See Figure 11 above).

Survival fundamentals:

The C-index measures the agreement between risk ranking and survival times. Time-dependent AUC and Integrated Brier Score (IBS) will be included in the extended module (current results show C-index and fixed-time Brier).

To avoid over-interpreting the C-index ≈ 1.00, we conducted additional validation: motor-level bootstrap (B = 1000) was conducted to obtain 95% confidence intervals for the C-index, time-dependent AUC, and Integrated Brier Score (IBS); a permutation test (shuffling event times or risk scores) was conducted to approximate the null distribution; and calibration curves compared predicted survival with Kaplan–Meier estimates. We further performed sensitivity checks by adding noise to the HI, perturbing the failure threshold by ±Δ, contrasting Leave-One-Motor-Out (LOMO) and grouped K-fold splits, and assessing quantile-interval coverage after stratifying by load and ambient temperature. Collectively, these diagnostics indicate near-perfect risk concordance on this dataset; yet, estimates can be optimistic under small-sample settings or specific configurations. Accordingly, we report interval estimates and calibration metrics and—per Section 4.3—outline external validation and a pre-registered analysis plan to ensure robustness and reproducibility across conditions.

3.6. Calibration and Diagnostics

Prediction intervals: Under-coverage (74.9% vs. nominal 90%) → to be improved with CQR, quantile regression, or conditional conformal calibration.

Survival calibration: Will be evaluated using calibration curves (predicted vs. Kaplan–Meier survival). Future work includes adding time-dependent ROC and IBS.

Data splitting: Strictly enforced grouped K-fold (using motor ID as group), ensuring statistical validity.

Censoring/truncation: Right-censoring is naturally managed; left truncation (delayed entry) will be handled through risk set adjustment in extended analyses. This approach ensures that the UAV does not pose safety risks to the power inspection due to hovering errors [47].

4. Discussion

The results demonstrate that integrating multiple mathematical frameworks allows for deeper insights into the lifetime and availability of UAV motors. The main contribution is not just in “AI prediction,” but in combining function approximation, time-series modeling, and survival statistics into a single, interpretable pipeline. We highlight three key aspects. These AIoT-powered features support a robust, real-time decision-making system, improving data-driven collaboration [48]. We provide an overview of observations collected during UAV operations and discuss RUL at a phenomenological level. We systematically analyze their impact on the quality of URL [49]. UAV independence assumes no spanwise interference between components [50].

First, the theoretical contribution of mathematical integration is the hybrid design that combines XGBoost (gradient boosting for nonlinear function approximation) with NARX (nonlinear autoregressive models with exogenous inputs for temporal dynamics). This approach addresses both nonlinear feature relationships and temporal dependencies, and is expressed as follows:

where extracts nonlinear mappings, and captures sequential propagation. Such a layered mathematical structure constitutes the core innovation.

Second, the mathematical progress in uncertainty quantification stems from the application of Conformalized Quantile Regression (CQR). Instead of symmetric intervals, CQR provides valid coverage through conformal calibration, ensuring that

applies across various operating regimes. This provides a mathematically sound method for determining safety margins in practical applications.

Third, the statistical extension in survival and availability analysis shows how motor lifetime can be modeled as a random variable T, characterized by S(t), h(t), and H(t), and then combined with machine learning predictions. Metrics like C-index, Brier score, and IBS quantitatively confirm risk ranking and probability calibration, connecting engineering interpretability with statistical rigor to quantify the volume of the flow processes featured [51].

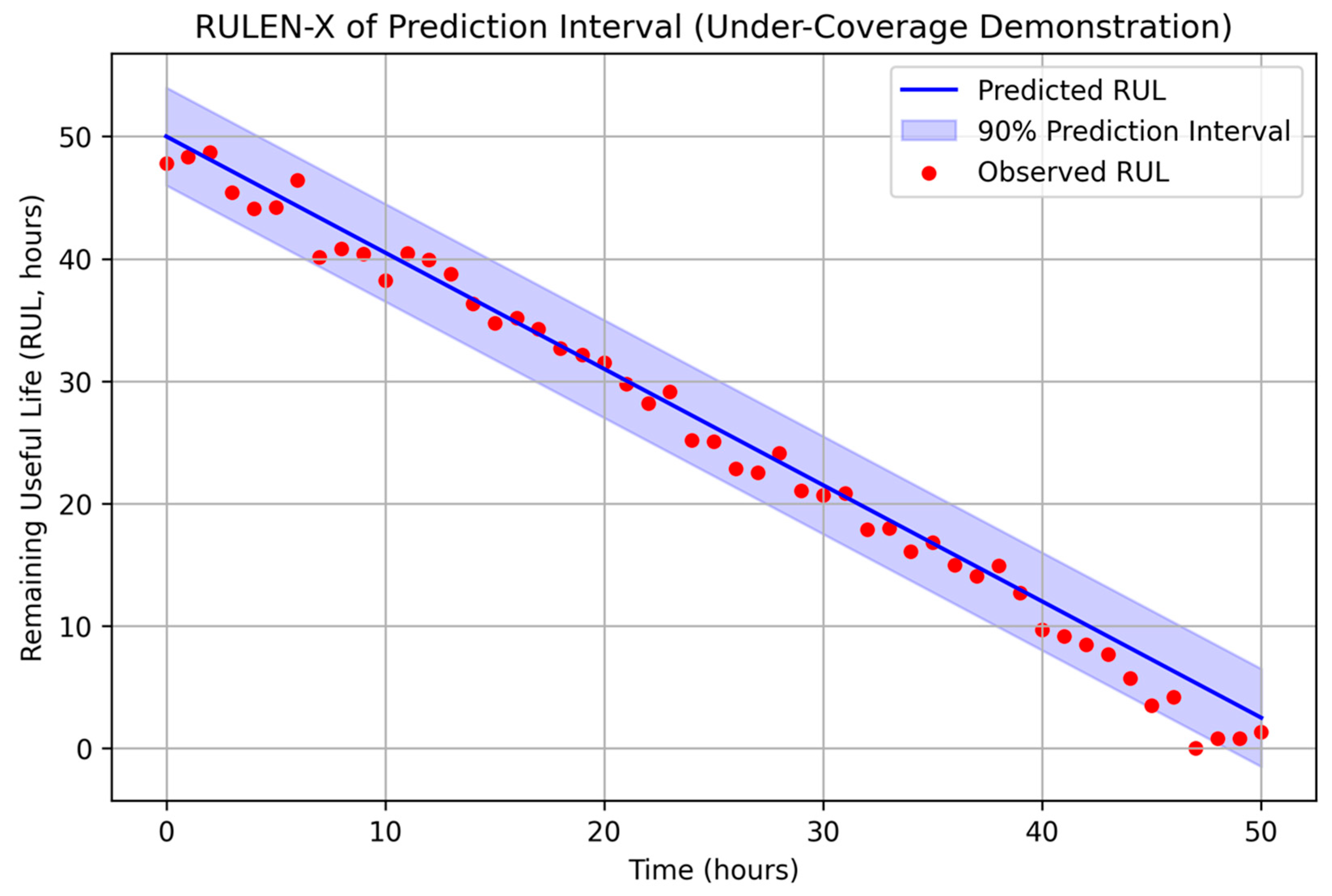

To better illustrate the under-coverage issue observed in the conformal prediction intervals (74.9% versus the nominal 90%), we include a visualization example of prediction intervals. Figure 12 shows predicted RUL trajectories with 90% confidence intervals represented by shaded bands around the mean forecast. Although the intervals generally follow the trend, several actual values fall outside the nominal bounds, confirming the under-coverage noted in Table 5.

Figure 12.

Prediction intervals of RULEN-X forecasts.

This graphical demonstration highlights two key issues:

- (1)

- Narrow intervals under heterogeneous conditions: When operating load or ambient temperature shifts, the intervals fail to adapt and underestimate uncertainty.

- (2)

- Systematic bias: Errors accumulate in multi-step forecasting, pushing observed RUL trajectories outside the prediction bands.

This visualization not only enhances the statistical diagnosis but also offers practitioners a clear understanding of the risks tied to under-calibrated intervals. Future improvements (e.g., Conformalized Quantile Regression, stratified calibration) will be evaluated to verify their effectiveness in reaching nominal coverage, as illustrated in Figure 12.

Predicted RUL (solid line) with 90% prediction intervals (shaded area) were compared to actual observed values (dots). Several observations fall outside the predicted ranges, indicating under-coverage compared to the nominal level.

In summary, the contribution of this work lies not only in “making predictions” but also in developing a cross-domain mathematical framework: nonlinear regression + temporal recursion + survival statistics. This offers an interpretable, verifiable, and extensible foundation for UAV motor prognostics. Future research will focus on multimodal sensing and Bayesian/probabilistic graph models to better quantify uncertainty.

4.1. Benchmark Comparison

While the proposed XGBoost–NARX hybrid framework shows strong performance in RUL prediction and availability analysis, it is essential to compare these results with standard baselines like Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) and Temporal Convolutional Networks (TCNs). These baselines were not directly implemented in this work; however, published studies on UAV or rotating machinery prognostics offer useful benchmarks for comparison.

Table 6 summarizes key results from the literature compared to the current study. The comparison shows that while deep learning models (e.g., LSTM, TCN) achieve decent accuracy, they often need larger datasets and can have interpretability issues. In contrast, the proposed XGBoost–NARX framework offers a good balance of predictive accuracy, mathematical rigor, and interpretability.

Table 6.

Comparison of different approaches for UAV motor RUL prediction.

4.2. Remaining Useful Life (RUL) and Availability

In this study, RUL and availability are key evaluation metrics of the proposed framework. Using grouped K-fold validation, the model achieved MAE of 4.01 h and RMSE of 4.51 h for RUL prediction, demonstrating strong performance across different UAV motor types. Additionally, multi-step forecasting with NARX showed consistent trend tracking, with a 200-step RMSE of 2.98 h, indicating its ability to capture short-term degradation dynamics without error buildup. For availability analysis, survival metrics reported a Harrell’s C-index of 1.00, reflecting perfect consistency in risk ranking, while the Brier score at t = 300 s was 0.159, indicating reasonable calibration performance. These results highlight the framework’s strength in both RUL prediction and availability assessment, providing a solid foundation for UAV maintenance planning and mission reliability. Future work will include validation of larger datasets and more varied operational conditions to further improve the approach’s generalizability.

4.3. Generalizability, Power, and External Validation

To strengthen generalizability, we implement four layers of validation: (1) Power and uncertainty. We conduct motor-level bootstrap (B = 1000) and report 95% CIs for MAE/RMSE, time-dependent AUC, IBS, and C-index; these intervals inform the adequacy of the current sample size and the precision of estimates. (2) Cross-device robustness. We compare Leave-One-Motor-Out with grouped K-fold, reporting error deltas and confidence intervals to detect any device leakage or over-fitting to specific motors. (3) Stratified coverage. We stratify by load, ambient temperature, and operating regimes, and evaluate quantile-interval coverage and bias; conditional conformal calibration enforces the desired coverage (e.g., 90%) within each stratum, improving reliability under domain heterogeneity. (4) External validation and data growth. We plan an external dataset spanning different brands, controllers, and longer degradation horizons, and will release protocols and code to facilitate replication. In addition, we perform HI-perturbation sensitivity and domain-shift tests to quantify robustness of survival and RUL metrics under plausible perturbations. A pre-registered analysis plan will be used to mitigate multiplicity and optimism bias, ensuring that conclusions remain stable as data scale and operating conditions change.

5. Conclusions

This study develops a mathematics-oriented AI iterative prediction framework that integrates XGBoost for nonlinear regression, NARX for temporal recursion, and survival statistics for UAV BLDC motor RUL and availability analysis.

The framework achieved an MAE of 4.01 h and an RMSE of 4.51 h for RULEN-X forecasting under grouped K-fold validation. Survival analysis showed consistent risk ranking with a C-index of 1.00, while calibration was measured by a Brier score of 0.159 at 300 s. These results confirm the effectiveness of combining nonlinear approximation, temporal dependency modeling, and survival functions into a unified mathematical system.

Key contributions include the following:

- (1)

- A layered mathematical design formalized as (29) which jointly manages nonlinear features and temporal dependence.

- (2)

- Enhanced interpretability through feature importance and SHAP, validating the role of temperature, vibration, and HI.

- (3)

- Reliable uncertainty quantification via CQR, ensuring coverage guarantees and efficient prediction intervals.

- (4)

- Integration of survival metrics to bridge predictive modeling with reliability assessment, improving both engineering interpretability and mathematical rigor.

In conclusion, the proposed framework provides a mathematically rigorous, interpretable, and practical solution for UAV motor health monitoring, RUL forecasting, and availability management.

However, this study has certain limitations. In particular, the relatively small dataset size may inflate the C-index and decrease the robustness of survival metrics.

Future work will broaden the dataset’s diversity and test real-flight scenarios to verify the approach’s effectiveness in different conditions. Additionally, cross-validation with larger open-source UAV datasets will be considered to further assess its generalizability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.-T.H.; methodology, C.-T.H. and K.-C.Y.; software, D.-F.C.; validation, W.-J.S. and D.-F.C.; formal analysis, K.-C.Y. and W.-J.S.; investigation, T.-Y.C. and C.-C.L.; resources, T.-Y.C. and B.-K.H.; data curation, T.-Y.C., B.-K.H. and C.-C.L.; writing—original draft preparation, C.-T.H.; writing—review and editing, K.-C.Y., B.-K.H. and W.-J.S.; visualization, D.-F.C.; supervision, C.-T.H. and K.-C.Y.; project administration, C.-T.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support from Yungui Technology Co., Ltd., which provided access to laboratory facilities, UAV equipment, testing tools, and the research website, enabling the successful completion of this study. They also sincerely appreciate the constructive feedback from colleagues during internal reviews. In particular, the authors would like to thank Hsu, Tian-Yu and Ma, Pei-Chi, who are employed at Yungui Technology Co., Ltd., for their valuable contributions in data organization and model analysis, which significantly enhanced the quality of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Chien-Tai Hsu was employed by the company Yungui Technology Co., Ltd. Author Bo-Kai Hsu was employed by the company Yungui Technology Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AFT | Accelerated Failure Time |

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| BLDC | Brushless Direct Current |

| CQR | Conformalized Quantile Regression |

| HI | Health index |

| IBS | Integrated Brier Score |

| IMU | Inertial Measurement Unit |

| MAE | Mean absolute error |

| NARX | Nonlinear AutoRegressive model with exogenous inputs |

| RMSE | Root mean squared error |

| RPM | Revolutions per minute |

| RUL | Remaining Useful Life |

| UAV | Unmanned Aerial Vehicle |

| XGBoost | Extreme Gradient Boosting |

References

- Ahwiadi, M.; Wang, W. Battery Health Monitoring and Remaining Useful Life Prediction Techniques: A Review of Technologies. Batteries 2025, 11, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freixes, A.; Panadero, J.; Juan, A.A.; Serrat, C. Combining the A* Algorithm with Neural Networks to Solve the Team Orienteering Problem with Obstacles and Environmental Factors. Algorithms 2025, 18, 309. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Yan, S.; Janicke, H.; Mahboubi, A.; Bui, H.T.; Aboutorab, H.; Bewong, M.; Islam, R. A Survey on Unauthorized UAV Threats to Smart Farming. Drones 2025, 9, 251. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragomir, L.O.; Popescu, C.A.; Herbei, M.V.; Popescu, G.; Herbei, R.C.; Salagean, T.; Bruma, S.; Sabou, C.; Sestras, P. Enhancing Conventional Land Surveying for Cadastral Documentation in Romania with UAV Photogrammetry and SLAM. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2113. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arok, M.; Brkljač, B.; Lugonja, P.; Ivošević, B.; Vukotić, M.; Lugonja, T.N. High resolution descriptors for UAV mapping in biodiversity conservation—A case study of sandy steppe habitat renewal. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0315399. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shafiee, S.; Montesinos-López, O.A.; Crossa, J.; Burud, I.; Dieseth, J.A.; Alsheikh, M.; Lillemo, M. Optimizing wheat crop performance: Genomic and phenomic insights into yield and days to maturity prediction using multi-temporal UAV imagery. Plant Phenome J. 2024, 7, e70004. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gronfula, M.; Sayed, K. AI-Driven Predictive Control for Dynamic Energy Optimization in Flying Cars. Energies 2025, 18, 1781. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F. An integrated multi criteria decision making method using dual hesitant fuzzy sets with application for unmanned aerial vehicle selection. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 12637. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haokip, S.C.; Rajwade, Y.A.; Rao, K.V.R.; Kumar, S.P.; Marak, A.B.; Srivastava, A. Approaches for Assessment of Soil Moisture with Conventional Methods, Remote Sensing, UAV, and Machine Learning Methods—A Review. Water 2025, 17, 2388. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Z.; Yu, K.; Qiu, R. Location-routing optimization of UAV collaborative blood delivery vehicle distribution on complex roads. Complex Intell. Syst. 2024, 10, 8127–8141. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piekutowska, M.; Niedbała, G. Review of Methods and Models for Potato Yield Prediction. Agriculture 2025, 15, 367. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, B.; Zhao, X.; Tang, X.; Xiao, M.; Zhu, H.; Li, J. A generalized diffusion model for remaining useful life prediction with uncertainty. Complex Intell. Syst. 2025, 11, 140. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, R.; Sorosh, S.; Lo, E.; Norton, T.J.; Driscoll, J.W.; Kuester, F.; Barbosa, A.R.; Simpson, B.G.; Hutchinson, T.C. Application Framework and Optimal Features for UAV-Based Earthquake-Induced Structural Displacement Monitoring. Algorithms 2025, 18, 66. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zeng, J.; Yang, Y.; Jia, Y.; Song, H.; Lv, T.; Sun, Q.; An, J. AI-Driven Safety and Security for UAVs: From Machine Learning to Large Language Models. Drones 2025, 9, 392. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, B.; Santos, M.; Dorian, T.; Moreno, M.; Trslic, P.; Dooly, G. Real-Time UAV Surveys with the Modular Detection and Targeting System: Balancing Wide-Area Coverage and High-Resolution Precision in Wildlife Monitoring. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 879. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Othman, S.; Ali, O. Residual capsule network with threshold convolution and attention mechanism for forest fire detection using UAV imagery. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 24360. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintana, J.A.; Bordons, C.; Esteban, S.; Delgado, J. Hybrid Powerplant Design and Energy Management for UAVs: Enhancing Autonomy and Reducing Operational Costs. Energies 2025, 18, 3101. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.-T.; Lin, Y.-C.; Yao, K.-C.; Ma, P.-C. A Study on the Performance of B&B Operations Is Conducted in Sustainable Tourism. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, S.; Fischer, F.J.; Ball, J.G.C.; Barbier, N.; Boisseaux, M.; Bonal, D.; Burban, B.; Chen, X.; Derroire, G.; Lichstein, J.W.; et al. TROLL 4.0: Representing water and carbon fluxes, leaf phenology, and intraspecific trait variation in a mixed-species individual-based forest dynamics model—Part 2: Model evaluation for two Amazonian sites. Geosci. Model Dev. 2025, 18, 5205–5243. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragazzo, A.V.; Mei, A.; Mattei, S.; Fontinovo, G.; Grosso, M. Illegal Abandoned Waste Sites (IAWSs): A Multi-Parametric GIS-Based Workflow for Waste Management Planning and Cost Analysis Assessment. Earth 2025, 6, 33. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portela, F.; Sousa, J.J.; Araújo-Paredes, C.; Peres, E.; Morais, R.; Pádua, L. Monitoring the Progression of Downy Mildew on Vineyards Using Multi-Temporal Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Multispectral Data. Agronomy 2025, 15, 934. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaoraingern, J.; Numsomran, A. Embedded Sensor Data Fusion and TinyML for Real-Time Remaining Useful Life Estimation of UAV Li Polymer Batteries. Sensors 2025, 25, 3810. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pyra, J.; Żołądek, T. Application of UAVs to Support Blast Design for Flyrock Mitigation: A Case Study from a Basalt Quarry. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 8614. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.; Jang, D.; Yoon, H.; Park, T.; Lee, K. GRU-Based Deep Learning Framework for Real-Time, Accurate, and Scalable UAV Trajectory Prediction. Drones 2025, 9, 142. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platel, A.; Sandino, J.; Shaw, J.; Bollard, B.; Gonzalez, F. Advancing Sparse Vegetation Monitoring in the Arctic and Antarctic: A Review of Satellite and UAV Remote Sensing, Machine Learning, and Sensor Fusion. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1513. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molęda, M.; Małysiak-Mrozek, B.; Ding, W.; Sunderam, V.; Mrozek, D. From Corrective to Predictive Maintenance—A Review of Maintenance Approaches for the Power Industry. Sensors 2023, 23, 5970. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrioaia, D.A.; Gaitan, V.G.; Culea, G.; Banu, I.V. Predicting the RUL of Li-Ion Batteries in UAVs Using Machine Learning Techniques. Computers 2024, 13, 64. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Cheng, G.; Huang, S.; Yang, J.; Yang, Y.; Xing, S.; Wang, J.; Yang, H.; Nie, H.; Yang, W.; et al. Winter Wheat Nitrogen Content Prediction and Transferability of Models Based on UAV Image Features. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1373. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choanji, T.; Jaboyedoff, M.; Yuskar, Y.; Samsu, A.; Fei, L.; Derron, M.-H. Evolution of Rockfall Based on Structure from Motion Reconstruction of Street View Imagery and Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Data: Case Study from Koto Panjang, Indonesia. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1888. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapelonis, Z.; Chatzigeorgiou, G.; Ntoumas, M.; Grigoriou, P.; Pettas, M.; Michelinakis, S.; Correia, R.; Lemos, C.R.; Pinheiro, L.M.; Lomba, C.; et al. Flying Robots Teach Floating Robots—A Machine Learning Approach for Marine Habitat Mapping Based on Combined Datasets. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 611. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Huang, B.; Gao, Y.; Jiao, C. Current Status and Prospects of Digital Twin Approaches in Structural Health Monitoring. Buildings 2025, 15, 1021. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedrtnam, A.; Negi, H.; Kalauni, K. Materials and Energy-Centric Life Cycle Assessment for Drones: A Review. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 169. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parnell, G.S.; Kenley, C.R.; Clark, D.; Smith, J.; Salvatore, F.; Nwobodo, C.; Davis, S. Decision Analysis Data Model for Digital Engineering Decision Management. Systems 2025, 13, 596. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.; Shafaei, S.; Jones, T.S.; Totaro, M.W. Secure Communication in Drone Networks: A Comprehensive Survey of Lightweight Encryption and Key Management Techniques. Drones 2025, 9, 583. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardar, M.U.; Vaimann, T.; Kütt, L.; Kallaste, A.; Asad, B.; Akbar, S.; Kudelina, K. Inverter-Fed Motor Drive System: A Systematic Analysis of Condition Monitoring and Practical Diagnostic Techniques. Energies 2023, 16, 5628. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khemiri, S.; Kishk, M.A.; Alouini, M.-S. Exploiting tethered and untethered UAVs: A hybrid aerial communication system. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 15882. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savas, T. A Risk-Based Analysis of Lightweight Drones: Evaluating the Harmless Threshold Through Human-Centered Safety Criteria. Drones 2025, 9, 517. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasquez-Camacho, L.; van Doorn, N.; Preisler, H.; Etxegarai, M.; Alas, O.; Castro, J.M.G.; De-Miguel, S. Monitoring temporal changes in large urban street trees using remote sensing and deep learning. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, 21. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Shao, Z.; Li, H.; Chen, J.; Sun, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, N.; Pei, L.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, H.; et al. A Novel Back Propagation Neural Network Based on the Harris Hawks Optimization Algorithm for the Remaining Useful Life Prediction of Lithium-Ion Batteries. Energies 2025, 18, 3842. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baktayan, A.A.; Zahary, A.T.; Sikora, A.; Welte, D. Computational offloading into UAV swarm networks: A systematic literature review. EURASIP J. Wirel. Commun. Netw. 2024, 2024, 69. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basil, N.; Marhoon, H.M.; Sabbar, B.M.; Mohammed, A.F.; Albahri, O.; Albahri, A.; Alamoodi, A.; Sharaf, I.M.; Amsal, A.M.; Ahmed, M.; et al. Multi-criteria decision model for multicircular flight control of unmanned aerial vehicles through a hybrid approach. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 18962. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinh, M.L.; Nguyen, D.T.; Dinh, L.Q.; Nguyen, M.D.; Setiadi, D.R.I.M.; Nguyen, M.T. Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAV) Networking Algorithms: Communication, Control, and AI-Based Approaches. Algorithms 2025, 18, 244. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanton, I.; Munir, K.; Ikram, A.; El-Bakry, M. Data augmentation for predictive maintenance: Synthesising aircraft landing gear datasets. Eng. Rep. 2024, 6, e12946. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Tong, Y.; Liu, D.; Yang, S.; Zhan, F. Preliminary Design and Optimization Approach of Electric FW-VTOL UAV Based on Cell Discharge Characteristics. Drones 2025, 9, 415. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacerda, L.N.; Ardigueri, M.; Barboza, T.O.C.; Snider, J.; Chalise, D.P.; Gobbo, S.; Vellidis, G. Using High-Resolution Multispectral Data to Evaluate In-Season Cotton Growth Parameters and End-of-the-Season Cotton Fiber Yield and Quality. Agronomy 2025, 15, 692. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muchla, A.; Kurcjusz, M.; Sutkowska, M.; Burgos-Bayo, R.; Koda, E.; Stefańska, A. The Use of BIM Models and Drone Flyover Data in Building Energy Efficiency Analysis. Energies 2025, 18, 3225. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.; Meng, X.; Yu, J.; Wang, J.; Yin, L. An unmanned intelligent inspection technology based on improved reinforcement learning algorithm for power large-area multi-scene inspection. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 24933. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabashkin, I. Framework for Addressing Imbalanced Data in Aviation with Federated Learning. Information 2025, 16, 147. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Xia, B.; Huang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Su, Y.; Gao, H. Automatic Detection System for Rainfall-Induced Shallow Landslides in Southeastern China Using Deep Learning and Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Imagery. Water 2025, 17, 2349. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; Zhou, D.; Wang, X.; Guo, Y.; Chen, H. Vibration Characteristic Analysis and Dynamic Reliability Modeling of Multi-Rotor UAVs. Machines 2025, 13, 697. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turbessi, L.; Taboni, B.; Umili, G.; Fubelli, G.; Ferrero, A.M. Modeling Debris Flow Events in the Rio Inferno Watershed (Italy) Through UAV-Based Geomorphological Survey and Rainfall Data Analysis. Sensors 2025, 25, 1980. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).