1. Introduction

Large language models (LLMs), which have become ubiquitous in generative artificial intelligence workflows, contain a predetermined set of tokens as the atomic units of their inputs and outputs [

1]. The set of tokens

T, when embedded within the latent space

X of an LLM, can be thought of as a finite sample drawn from a distribution supported on a topological subspace of

X. One can ask what the smallest (in the sense of inclusion) subspace and simplest (in terms of fewest free parameters) distribution is that can account for such a sample.

Previous work [

2] suggests that the smallest topological subspace from which tokens can be drawn is not manifold, but has structure consistent with a stratified manifold. That paper relied upon knowing the token input embedding function

, which given each token

, ascribes a representation in

X. Because embeddings preserve topological structure, in this paper, we study

T by equating it with the image of the token input embedding function, thereby treating

T both as the set of tokens and as a subspace of

X. This subspace is called the token subspace of

X. Usually,

X is taken to be Euclidean space

, so the token input embedding function is stored as a matrix, with rows corresponding to tokens and columns to coordinates within the latent space. For instance, for the LLM

Llemma-7B [

3], there are 32,016 tokens that are embedded in

, so consequently, the token input embedding is a 32,016 × 4096 matrix.

A significant limitation of [

2] is that it relies upon direct knowledge of the token subspace via the token input embedding function. The authors only considered open-source models because the token input embedding function is distributed as part of the model. Many LLMs are proprietary and their internals are hidden [

4,

5], and as a result, the methods of [

2] are not applicable to any of these models. Because understanding the behavior of LLMs, proprietary or not, is essential for determining conditions under which they are appropriate for a given task, the requirement of having the token input embedding function in hand is a severe and potentially pervasive limitation. This article shows that this limitation can be completely lifted under surprisingly broad conditions. Specifically, we show that an unknown token subspace can be recovered up to homeomorphism (a kind of strong topological equivalence) by way of structured prompting of the LLM, without further access to its internal representations.

Our strategy exploits Takens’ classic result [

6] in dynamical systems, whereby an attractor is recovered up to homeomorphism by way of a vector of lagged copies of the timeseries produced by the dynamical system. Takens’ result asserts that if enough lagged copies are used, then the attractor can be recovered using almost every choice of lag values. Because LLMs are discrete systems that produce a sequence of tokens instead of a continuous timeseries, Takens’ result does not directly apply to LLMs. Consequently, like Takens’ result, we collect a sequence of outputs from the system (a “response”), but instead of using a single timeseries, we must restart the system at each token (a “query”). Underlying Takens’ result is the concept of transversality, which ensures that almost every choice of lags yields a homeomorphism. Transversality also applies to LLMs, though in a different way. The token subspace of almost every LLM can be reconstructed up to homeomorphism from almost every observable we choose to collect about its token sequence.

Once the token subspace has been obtained, it has a striking topological and geometric structure. For instance, it has a definite local dimension near many tokens, can exhibit singularities (points where the space is not a manifold) [

7], may have different clusters of semantically related tokens, and has negative curvature within subspaces that admit such a definition. It is natural to ask whether this structure has a measurable impact on the “behavior” of the LLM, namely its response to queries. Since this article shows that the token subspace can be recovered by studying the responses of the LLM to structured prompts, we must conclude that the topology of the token subspace has a direct and measurable impact on LLM behavior.

1.1. Contributions

This article presents a general and flexible method (Algorithm 1) for prompting an LLM to reveal its (hidden) token subspace up to homeomorphism, and provides strong theoretical justification (Theorem 1) for why this method should be expected to work. With this method in hand, we demonstrate its effectiveness in

Section 4 by recovering the token subspace of

Llemma-7B, an open-source model with 32,016 tokens embedded in 4096 dimensional space.

Llemma-7B was selected due to its moderately sized token subspace and open-source documentation. As Algorithm 1 requires systematically prompting every token, a moderate number of potential tokens enables computational tractability. Because it is open source, the local dimensions at each token are already documented [

2], so we can directly verify that the topology is correctly recovered, as Theorem 1 claims. The implication is that the method can also recover the token subspaces for LLMs, in which these token subspaces are not published. Recognizing that LLMs are a kind of generalized autoregressive process, the proof of Theorem 1 applies to general nonlinear autoregressive processes.

| Algorithm 1 Recovered token input embedding coordinates |

- Require:

ℓ: number of probabilities to collect per token - Require:

m: number of response tokens to collect - Require:

r: number of repeats for each query to collect - Require:

: fixed prefix for all queries - 1:

procedure TokenPromptEmbedding(x; ℓ, m, r) ▷x is the token to embed - 2:

Clear the context window - 3:

Build a query of the form - 4:

Use the LLM to produce a response of length m to the query q ▷ This computes - 5:

Repeat the previous three steps r times to estimate probability of most probable ℓ tokens in each of the m positions ▷ Applying the function g. - 6:

return The length vector of probabilities as embedding coordinates ▷ This is flattened into a single vector. - 7:

end procedure

|

1.2. Related Work

In [

8], it was hypothesized that the local topology of a word embedding could reflect semantic properties of the words, an idea that appears to be consistent with the data [

9]. Words with small local dimension (or those located near singularities) in the token subspace are expected to play linguistically significant roles. A few papers [

8,

10,

11] have derived local dimension from word embeddings. Additionally, Refs. [

12,

13] show that there is a generalized metric space in which distances between LLM outputs are determined by their probability distributions. These papers do not address differences between possible embedding strategies, nor the fact that different LLMs will use different embeddings. In short, while they acknowledge that topological properties can be estimated once the token subspace is found, they do not address how to find the subspace in the first place.

All of the existing methods for studying embeddings, whether they are word, token, or phrase embeddings, require access to the embedding directly. That is to say, for word embeddings, the coordinates of each word that is present must be taken as an input. This can either be provided as a table of words and coordinates (as is typical for LLMs) or as the specification of the embedding function as source or executable code. For those embeddings that are open source or otherwise published (example: [

14,

15]), this provides no impediment. But if the listing of (or function specifying) coordinates is not available, then the existing methods simply cannot be used. Therefore, our method makes it possible to apply these existing analyses to token input embeddings that are part of an LLM, even if they are not published with the LLM.

The transformer within an LLM makes it into a kind of dynamical system [

16]. A classic paper by Takens [

6] shows how to recover attractors—behaviorally important subspaces—from dynamical systems. Following the method discovered by Takens, a large literature grew around probing the internal structure of a dynamical system by building embeddings from candidate outputs, refs. [

6,

17]. While the usual understanding is that these results work for continuous-time dynamical systems, in which certain parametric choices are important [

18], the underlying mathematical concept is transversality [

19]. Transversality is a generalization of the geometric notion of “being in general position,” for instance, that two points in general position determine a line, or three points determine a plane. Moreover, two submanifolds can intersect transversally, which means that along the intersection, their tangent spaces span the ambient (latent) space. Transversality is useful because it yields strong conditions under which knowledge of several subspaces is sufficient to understand the entire ambient space. In this paper, we apply transversality to obtain a new embedding result for general nonlinear autoregressive systems, of which LLMs are a special case.

2. Preliminaries

A linear autoregressive system produces a sequence of values

in a vector space

X given by a formula of the form

where the scalars

are fixed. Such a system is said to depend upon a window

of size

n, so the equation for

implies a function

. If we generalize so that

X is a smooth manifold, the function

f can be taken to be a smooth function instead of a linear one. It is often the case that the values in

X are not directly observable. Instead, we observe the values through a measurement function

. We call the pair

a general nonlinear autoregressive system.

An LLM is a kind of general nonlinear autoregressive system that produces a sequence of tokens. The time steps correspond to positions within this sequence. Internally, each time step is a point in a fixed latent space

X. For instance, if

X represents the set of letters and one sees the following sequence of 5 letter windows

jabbe,

abber,

bberw,

berwo, one can be reasonably certain that the window could ultimately become

wocky. To model that behavior, one might have that

for instance.

Transformer-based LLMs use a stochastic version of the above idea, so that each point in

X represents (often in a compressed representation) a probability distribution over all tokens instead of the set of tokens themselves. The function

predicts the probability of each possible token given a sequence of

n tokens occurring previously in the sequence of tokens. This representation captures the intuitive idea that the structure of text is self-consistent but is also not predetermined. As a result of this representation, each time step is built from the iterates of shifts

of a given map

that predicts one point from a window of

n previous points. In an LLM, the map

f is usually implemented using one or more transformer blocks, and the tokens are embedded as points in

X. Here, we only require that the transformer block be a smooth function, which is consistent with how they are implemented [

16].

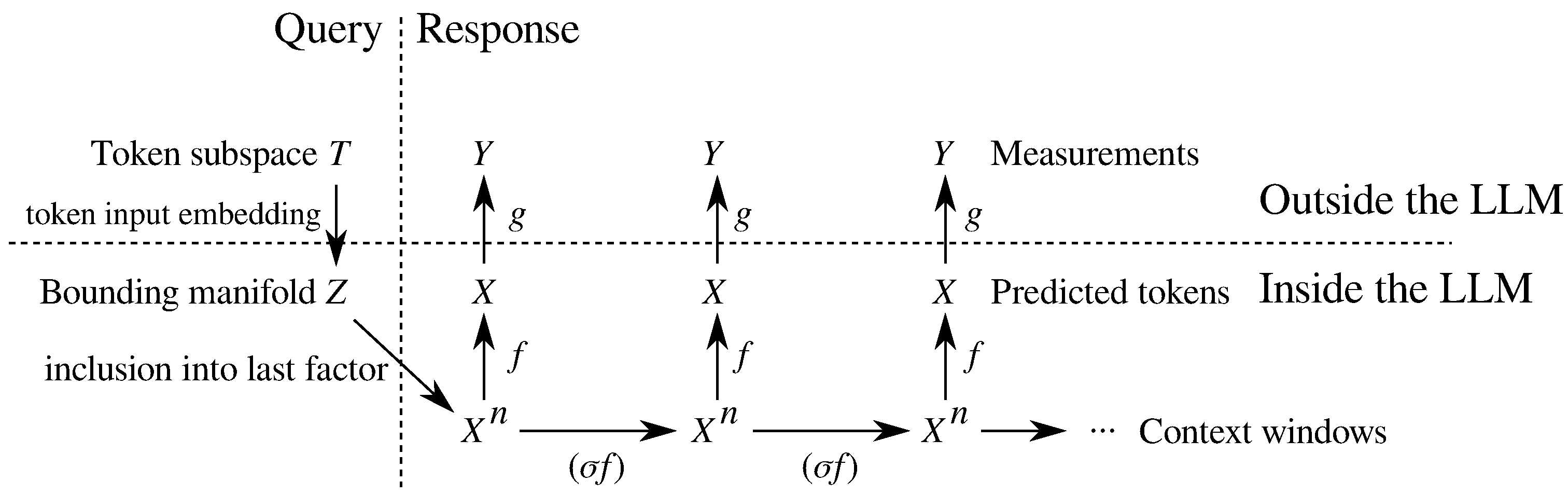

Definition 1. Suppose that X is a smooth finite-dimensional manifold of constant dimension, and that for some integer n, we have a smooth function . The shift of f is the function given by Usually, the latent space is not made visible to the user of an LLM. Instead, one can only obtain summary information about a point in X. This could be as simple as the textual representation of a point in X as a token (which is a categorical variable), but could be more detailed. For instance, running the same query several times will yield an estimate of the probability of each token being produced. In order to model the general setting, let us define a space Y that represents the data that we can collect (say, a probability) about a token in X. This measurement process is represented by a smooth function , which—according to our Theorem 1—can be chosen nearly arbitrarily. In the context of LLMs, the function g is often called the output embedding function (caution: g is rarely an “embedding” in the sense normally used by differential topologists). If the model is open source and X is the actual token probabilities, then it is possible to take .

Definition 2. The k-th iterate of a function , namely k compositions of h with itself, is written . By convention , the identity function on X.

Given a function , a function , and a non-negative integer m, the m-th autoregression of f with measurements by g is the function given byWe will assume that X and Y are finite dimensional smooth manifolds and f and g are both smooth maps throughout the article. The function represents the process of collecting data about the first m tokens in the response of the LLM to a context window of length n. The function g represents the information we collect about a given token in the response. Beware that in practice, since both f and g estimate probabilities from discrete samples, both are subject to sampling error.

While the token subspace

T is not generally a manifold [

2], in practice, it is always contained within a larger compact manifold, which we will call the bounding manifold

Z. Since the token subspace

T is not a manifold,

Z will generally not be equal to the token subspace

T. If we obtain an embedding of

Z, then the token subspace

T will also be embedded within the image of

Z.

Our method (Algorithm 1) requires that the context window of the LLM be “cleared” before each query to ensure that the hypotheses of Theorem 1 are met. We formalize the operation of clearing the context window by considering the restriction

to the subspace

. Notice that this means that the first

tokens of the initial context window are always the same (with no further constraints on exactly what values they take), while the last token in the context window is drawn from

Z. We write this restriction as

. Clearing the context window is straightforward if one has direct access to the model. For instance, in the HuggingFace

transformers library [

20] or the

ollama library [

21], clearing the context window simply requires that the prompt for the

generate method contains exactly the desired prefix and token and nothing else.

3. Methods

The main thrust of our approach is embodied by Algorithm 1, which produces a set of Euclidean coordinates for each token. Because Theorem 1 only yields a homeomorphism, not an isometry, the coordinates we estimate will not be the same as those in the original embedding, nor will the distances between tokens be preserved. Topological features, such as dimension, the presence of clusters, and (persistent) homology, will nevertheless be preserved. Since checking whether two spaces are homeomorphic is extremely difficult [

22,

23], in

Section 4, we will only verify that dimension is preserved. Other verifications remain as future work.

The researcher will need to select the m, ℓ, and r parameters in order to apply Algorithm 1, as well as the fixed prompt prefix. We found that choosing the shortest possible prefix works well enough and suspect that it is often the best choice. The parameters m and ℓ must be chosen to satisfy Theorem 1, with the recommendation that m be chosen as small as possible if direct access to the transformer within the LLM is available. If not, reducing ℓ is likely the best course of action.

Finally, it remains to select the number of repeat samples

r for each query. If direct access to the transformer is available, then

is recommended since the entire probability distribution for the tokens is available. If direct access to the transformer is not available, the best choice of

r is governed by the need to gather enough samples of the probability distribution to obtain a reliable estimate. Since the distribution may be heavy-tailed, selecting an optimal choice of

r is a difficult theoretical and practical problem. More recommendations are included in

Section 5.

Figure 1 summarizes the process. Each token in the token set is taken as a query, and yields in response a sequence of tokens, each of which has an internal representation in

X. If one has direct access to the model, clearing the context window can be performed simply by ensuring that the query contains only the prefix and the tokens as desired. All we have access to are summary measurements of this internal representation, viewed through the function

g. In Algorithm 1, we have chosen to define

g so that it estimates probabilities of tokens, even though Theorem 1 is more general than that. To that end, Steps 1–3 are repeated sufficiently many times to obtain a stable estimate of the probability of each of the

ℓ tokens. Therefore, each token yields a sequence of token measurements in

, where

m is the number of response tokens we wish to collect.

It is worth noting that if one is applying Algorithm 1 to an open-source LLM based upon a transformer, one can completely avoid sampling error by using the probabilities directly produced by the model. In this case, one may set in Algorithm 1.

The correctness of Algorithm 1 is justified by Theorem 1, which asserts that the process of collecting summary information about the sequence of tokens generated in response to single-token queries is an embedding, provided certain bounds on the number of tokens collected are met.

Theorem 1 (Proven in

Appendix A).

Suppose that X is a smooth manifold, Y is a smooth manifold of dimension ℓ, that are elements of X, and Z is a submanifold of X of dimension d. For smooth functions and , the function given in Definition 2, collects m samples from iterates of .If the dimensions of the above manifolds are chosen such thatthen there is a residual subset (a residual subset is the intersection of countably many open and dense subsets) V of such that if , then there is a (different) residual subset U of such that if , then the functionis a smooth injective immersion (an immersion is a smooth function whose derivative (Jacobian matrix) is injective at all points). Following this, it is a standard fact (see Proposition 7.4 in [24]) that if Z is compact, then is an embedding of Z into . Since the token subspace T is always compact, if we satisfy the inequalities on dimensions, most choices of f (the LLM) and g (the measurements we collect) will yield embeddings of into if the appropriate number of measurements is collected. Furthermore, since embeddings induce homeomorphisms on their images, even if the token subspace is not a manifold, its image within will be topologically unchanged.

Equation (

1) is based upon, and should be reminiscent of, the classical Whitney embedding theorem (Theorem 10.11 in [

24]). Specifically, there is a residual set of smooth functions that embed the bounding manifold

Z into Euclidean space

if

. Roughly speaking, Equation (

1) restates this requirement with

, since the functions under study have codomains built as a product of

m copies of the manifold

X. The insight of Theorem 1 (beyond the classical Whitney embedding theorem) is that while the residual subset of

all smooth functions yielding embeddings might not include

, a smaller residual subset is sufficient to obtain an injective immersion.

The ordering of the residual subsets, that first g is chosen and then f may be chosen according to a constraint imposed by g, is necessary to make the proof of Theorem 1 work. In essence, a poor choice of g can preclude making any useful measurements, regardless of f. From a practical standpoint, one selects the measurement strategy (corresponding to the function g) first, and then selects the model(s) f to study, provided that they are supported by the chosen measurement strategy, namely that f is in the residual subset U.

LLMs are based upon transformers, so X is internally stored both as a latent space and as the space of probabilities on the set of tokens, and the application of f passes through both spaces. In the usual software interface, X is presented to a user of the LLM as the space of probabilities, not the latent space. As a result, a natural—and effective—choice of g is . Since the bounding manifold dimension is usually much smaller than the number of tokens, the hypotheses of Theorem 1 are satisfied trivially if the set of token probabilities is available. However, this is precisely the situation of having direct access to the LLM, such as is afforded by an open-source model.

When not exploring open-source models, one must confront the fact that Algorithm 1 operates in the opposite way than Theorem 1 requires. The LLM (described by

f) is selected without regard for the properties to be collected (described by

g). While a poor choice of

g is not likely to recommend itself to engineers in the first place, Algorithm 1 suggests the use of probability estimation as

g. Again, since LLMs are based on transformers, they internally store probabilities for tokens. As a result, the choice of

g made in Algorithm 1 is particularly apt. Further details are covered in

Appendix A.

4. Results

To demonstrate our method, we chose to work with

Llemma-7B [

25]. This model has 32,016 tokens in total, which are embedded in a latent space of dimension

. We interfaced with the model using the

transformers Python 3.13 module from HuggingFace [

20], which provides direct access to both generation capabilities and the model weights as

PyTorch 2.5.0 tensors. Since the source code and pre-trained weights for the model are available, the token input embedding is known. Additionally, because the model is of moderate size, no special hardware provisions were needed to manipulate the token embedding or perform the prompting. We can therefore compare the token subspace of the model with the embedding computed by Algorithm 1.

Llemma-7B uses a context window of

tokens, since [

3] says the model was trained on sequences of this length.

As per the results exhibited in Figure 7 of [

2], the token subspace is a stratified manifold in which all strata are dimension 14 or less. According to [

26], this implies that the token subspace can be embedded in a Euclidean space of dimension 29. Therefore, the manifold

Z that contains the token subspace can be taken to be not more than

dimensional, and even though this is probably quite a loose bound.

Algorithm 1 requires the use of a function g to collect m samples from each response token. We tried three different Options for the choice of g and the number of tokens we collected:

- Option (1):

Collect response tokens and probabilities for the top three tokens at each response token position (ignoring what the tokens actually were);

- Option (2):

Collect response tokens and ℓ = 32,016 probabilities, one for each token, but aggregated over the entire response;

- Option (3):

Collect response token and ℓ = 32,016 probabilities, one for each token being the first token in the response.

Since Llemma-7B is open source and based upon a transformer, we collected the probabilities in Options (2) and (3) directly from the transformer output. Because sampling error in the process of computing g is a concern, we can use the difference between Options (2) and (3) to isolate the effect of this sampling error. Because Option (3) collects exactly response tokens and all probabilities for all tokens, it is entirely deterministic and subject to no sampling error. Therefore, any differences we observe between Options (2) and (3) are entirely attributable to sampling error. Differences between Options (1) and (2) are due to the change in the number of probabilities estimated but not the response length.

We did not examine any cases where the transformer output itself was sampled, as would entail much longer runtimes than we were able to afford, and is likely to result in substantially higher sampling error.

Recalling that

, Option (1) satisfies the hypotheses of Theorem 1 because

Option (2) also satisfies the hypotheses of Theorem 1 because

Option (3) also satisfies the hypotheses of Theorem 1 because

As post-processing, we compared the dimensions at each token estimated from the three Options with those dimensions estimated from the original token embedding. Following the methodology of [

2], we recognize that dimension estimates do not tell the full story, especially because there are some tokens for which a valid dimension does not exist [

7]. In fact, most of the tokens in the token subspace for

Llemma-7B have

two salient dimensions: one for small radii and one for larger radii. To this end, Ref. [

7] shows that for many tokens, a better model for the token subspace than a manifold may be a fiber bundle. In the setting we need here, a fiber bundle is triple of topological spaces

and a continuous surjection

such that each point has an open neighborhood

for which

is homeomorphic to

. The space

B is called the base and

F is called the fiber.

If the token subspace is well represented by a fiber bundle, a given token will have two dimensions: the dimension of the fiber space and the dimension of the base space. As Ref. [

7] shows, both dimensions can be estimated from the data. If one considers the tokens in a small neighborhood around a given token, the variability across these tokens will generally reflect the sum of the base and fiber space dimensions. Conversely, if one considers tokens in an increasingly larger neighborhood around a given token, that variability will reflect the base dimension alone.

Given these experimental parameters, we used Algorithm 1 to compute coordinates for each of the 32,016 tokens. This process took 13 h of wall time on a MacBook M3. Afterwards, the method from [

7] was used to estimate the local base and fiber dimensions at each token; this took 3 h of wall time on a Core i7-3820 running 3.60 GHz. The entire process, consisting of the pipeline of (1) selection of one of the Options, (2) Algorithm 1 using that Option for data collection, followed by (3) dimension estimation, will be referred to as a “proposed dimension estimator”.

Because the embedding produced by Algorithm 1 using Option (1) is into , while the others embed into substantially higher-dimensional space, doing any post-processing is much easier on Option (1) than the others. As a consequence, we will mostly focus on the proposed dimension estimator with Option (1) after establishing that it is qualitatively similar to the others.

Because Options (2) and (3) are very computationally expensive, we drew a stratified sample of 200 random tokens to compare dimensions across all three Options and the original embedding. We drew a simple random sample of 100 tokens from the distribution at large and another simple random sample of 100 tokens with a known low dimension (below 5). The reason for this particular choice is that [

2] establishes that a few tokens in

Llemma-7B have unusually low dimension (less than 5), and we would like to ensure that this is correctly captured.

Figure 2 shows the estimated dimension for these two strata across all three Options against the true token input embedding. There are two different kinds of sampling error involved: the sampling error in estimating

g and the error in drawing the stratified sample. It is clear that both strata are recovered by Algorithm 1 using all three Options, but that there are biases present across all Options, and the variance of the estimates is increased across all Options. The reader is cautioned that the outliers in

Figure 2 are likely misleading because each of the top three box plots consists of 200 tokens, whereas the bottom box plot consists of 32,016.

Therefore,

Figure 2 indicates that the differences between different Options are not large. Since Option (3) collected only

token, the process for Option (3) is deterministic. This eliminates sampling error from Option (3), allowing us to directly measure the influence of sampling by comparing Options (2) and (3). In short, the token input embedding has a stronger impact upon the behavior of the LLM than the sampling error from estimating

g from

samples.

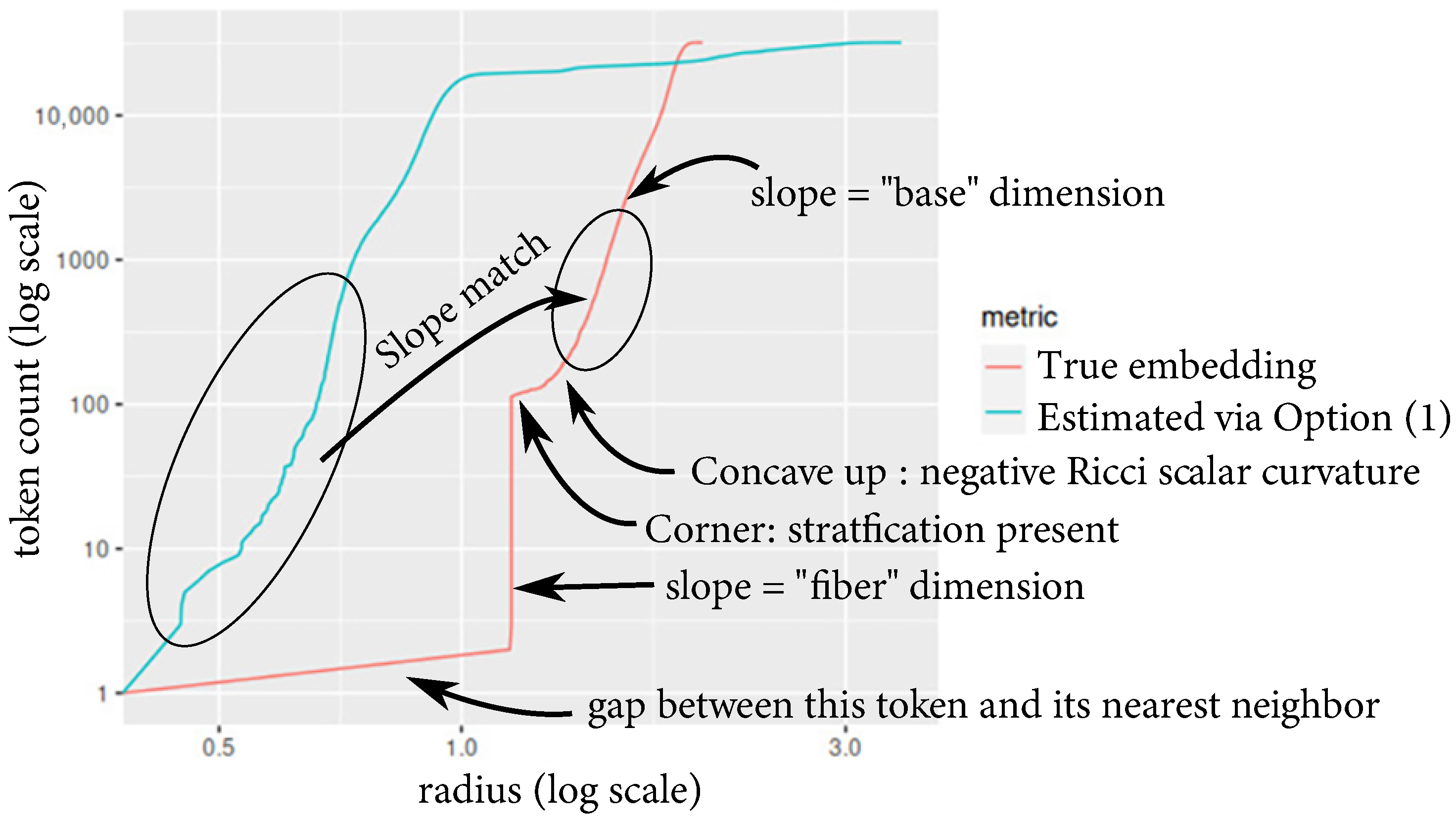

As part of the dimension estimation process, we computed the volume (token count) versus radius for all of the tokens.

Figure 3 shows one instance, which corresponds to the token “

}” appearing at the start of a word. Notice that there are “corners” present in the curve derived from the original embedding, which is indicative of stratifications in the token subspace, according to Theorem 1 in [

7]. The stratification structure in the vicinity of this particular token is indicative of a negatively curved stratum (larger radii) that has been thickened by taking the Cartesian product with a high-dimensional sphere of definite radius (smaller radii). In the case of

Figure 3, the radius of this sphere is approximately

, as indicated by the vertical portion of the red curve.

The structure of two distinct dimensions, suggesting a fiber bundle is a reasonable model, is typical throughout the token subspace for

Llemma-7B, though the radius of the inner sphere tends to vary substantially. As suggested in [

7], one should use the intuition that the base stratum corresponds to the inherent semantic variability in the tokens, while the fiber stratum mostly captures model uncertainty, noise, and other effects. Indeed, the definite radius of the sphere at each token appears to be characteristic of

Llemma-7B; other LLMs do not seem to exhibit this structure as clearly.

Notice that for the token shown in

Figure 3, there is an apparent match in slope between the estimate provided by the proposed dimension estimator with Option (1) and the slope within the base portion of the original embedding. This suggests that the base portion of the token subspace is most important in terms of the LLM’s responses. This accords with some of the intrinsic dimension estimates in the literature for natural language (see, for instance, refs. [

8,

10,

11]), since the base dimension tends to be in the vicinity of 5–10, whereas the fiber is much higher dimensional. This intuition is confirmed in the analysis that follows.

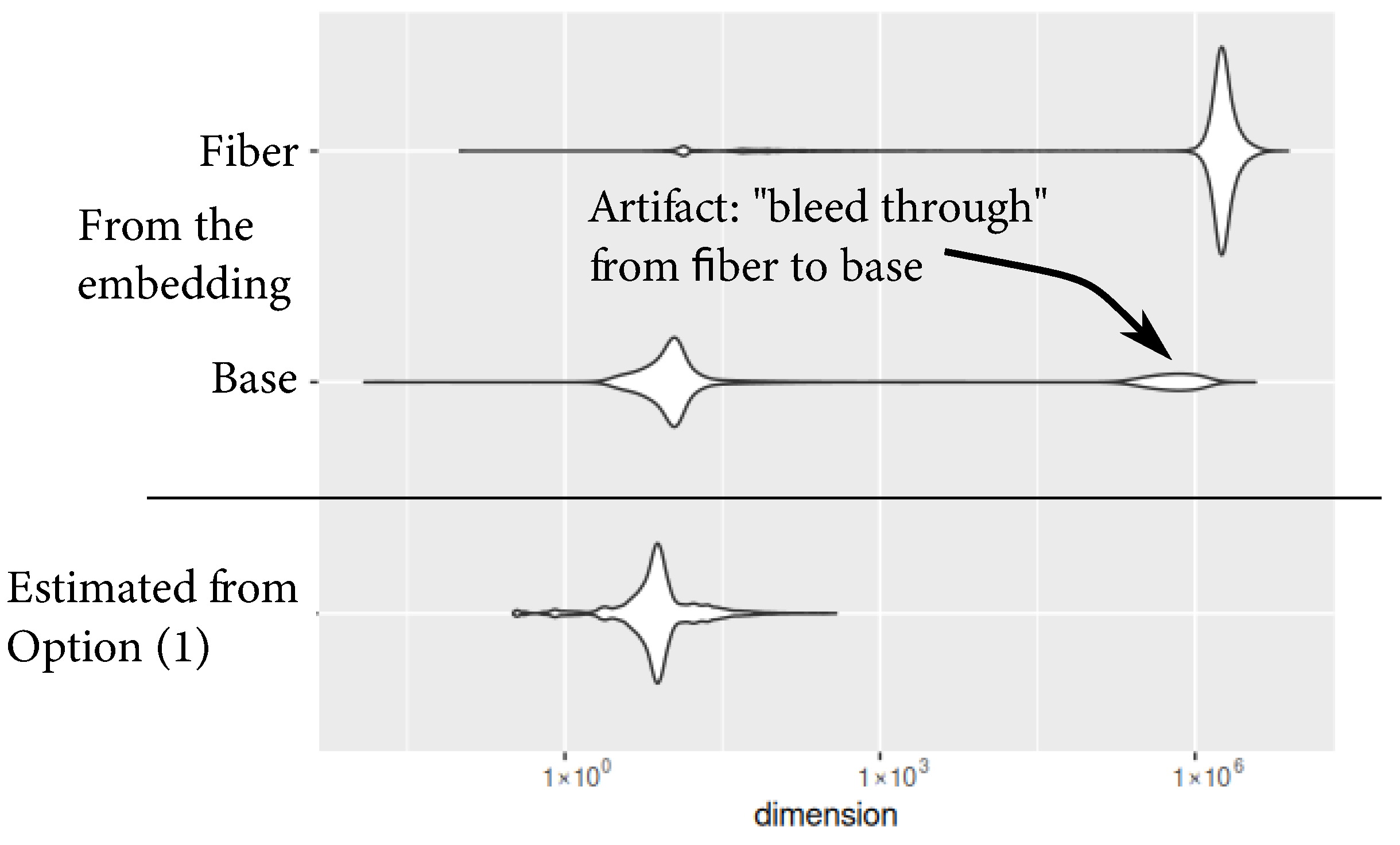

The dimension estimated by the proposed dimension estimator across all three Options is more sensitive to the base dimension, and therefore can be understood to estimate the base space of the fiber bundle structure of the token subspace. This is consistent with the findings given in [

7]. Across several LLMs, the fiber dimension variability is quite high compared to that of the base. Both (A.3) in Ref. [

7] and the findings in the present article argue for a heteroscedastic noise model, one in which the variability in a neighborhood around a token depends on the token being examined and is not global across all tokens. This suggests that small-scale perturbations due to noise, quantization error, or other uncertainties tend to be concentrated in more directions than the true variability being captured by the model. Although the true variability is confined to a fairly low-dimensional stratum, the smaller-scale perturbations obscure this when small-radii neighborhoods are considered.

Figure 4 shows the distribution of local dimensions estimated for all tokens using the original embedding (base and fiber computed separately) and using the proposed dimension estimator with Option (1). As is clear from

Figure 3, stratifications are not clearly visible with the proposed dimension estimator, so each token is ascribed only one dimension.

Figure 4 shows that the estimated dimension aligns closely with the base dimension. This agrees with the intuition that the fiber dimension mostly corresponds to noise-like components, which ultimately have less impact on the LLM responses.

There are a few tokens with very few neighbors under the token input embedding. These isolated tokens have a local dimension less than 1.

Figure 5 shows that the proposed dimension estimator with Option (1) reports significantly lower dimensions for the isolated tokens, both in the fiber and the base. There is a bias towards the median dimension of approximately 10 that is likely due to random sampling effects.

5. Discussion

We have demonstrated that Algorithm 1 allows one to impute coordinates to tokens from LLM responses in a way that leads to an embedding of the latent space into the space of responses. This establishes that the topology of an LLM’s token subspace has a strong link to the LLM’s behavior, specifically tokens that are near each other result in similar responses. As suggested by others [

2,

8], this may explain why LLMs are not performant against certain kinds of queries.

5.1. Algorithm Usage Guidelines

According to the ordering of the selection of the measurement function g and model f in Theorem 1, one first selects the data that will be collected from the models under test, and then selects the models that are appropriate to be studied in this way. (this corresponds to the selection of g first, followed by f, subject to its corresponding hypothesis in Theorem 1). For instance, if one wishes to collect entire probability distributions (, , ℓ is the number of tokens), then one is restricted to models for which one has direct access to the transformer. If instead one wishes to estimate probability distributions from small samples (m and r larger, ℓ smaller), then one is restricted to models that use smaller vocabularies.

To apply our Algorithm 1, one then selects the fixed prompt prefix to be used. This need not be difficult; we simply chose the start token that Llemma-7B requires as the entire prefix in our experiments. When applying our method to a proprietary model, the model likely includes “system prompts” and “templates” that are inaccessible to the researcher. However, clearing the context window before each prompt will usually set both of these to the same prefix each time. Using the transformers library, clearing the context window is performed by ensuring that the prompt for the generate method is exactly the desired prefix and token, and nothing else. Even though that prefix remains unknown to the researcher, Theorem 1 ensures that the token subspace will still be recovered.

According to our results in

Section 4, selecting the choice of Option is not critical in terms of accuracy. We have shown that the resulting dimension estimates are about the same across all of them, according to

Figure 2. Moreover, Theorem 1 ensures that the Options do not differ theoretically.

5.2. Parameter Selection

The context window size n is generally stated by the model provider. Even for proprietary models, the context window size n is often disclosed, as it is seen as a proxy for model “strength.” The researcher wishing to use our method may have no control over n but will probably have a good idea of its approximate value.

Practically, there is no optimal choice of the number of tokens m to collect in the response. Given the fact that our method is inspired by the Takens delay embedding idea, it is reasonable to suppose that more response tokens are better. However, if the token probabilities need to be sampled, the computational cost for collecting enough samples to estimate the probabilities in the g function will quickly become prohibitive. Therefore, if probability estimation is required, we strongly suggest collecting the minimum number m of tokens required by Theorem 1.

There still remains the trade-off between m, ℓ, and r. The choice of all three parameters will depend strongly on the performance requirements of the particular LLM under study. If the model can be held in memory (even on a remote server) so that prompts may be run “in batches,” it is a better choice to keep m as small as possible and choose a larger ℓ to satisfy Theorem 1, as then each prompt can run independently and in parallel. This does result in slower dimension estimation, because the distances between all pairs of tokens now involve longer coordinate vectors. It is for this reason that we compared only a stratified sample of tokens using Options (2) and (3).

For an open-source model, selecting parameters can be taken to its natural limit (ℓ is the number of tokens, , ), since the transformer directly computes probabilities for every token and these can be simply captured; this is what we performed in Option (3). If the model is not open source, but direct access to the transformer is available, this remains the best option.

However, if the transformer is not available, the researcher will have to perform sampling to estimate the distribution. In this case, reducing ℓ to a much smaller value and taking r to be larger (simulated by Options (1)) is a viable strategy.

Selecting r, the number of repeat queries to run, is difficult to optimize. Clearly, the runtime of Algorithm 1 scales linearly with r, although parallelization is possible. Since the purpose of r is to control the recovery of the distribution of the next token, and this distribution may be heavy-tailed, it may be necessary to take r to be a fairly large fraction of the number of tokens. On the other hand, in deployed LLMs, the responses are drawn not from the distribution produced directly by the transformer, but instead from a subset of the most likely tokens. At the time of writing, often, only tens of tokens are in this subset, so choosing r to be in that vicinity is a reasonable starting point.

5.3. Unexpectedly Interesting Output

Aside from the process of estimating the topology of the token subspace, the raw output of Algorithm 1 is interesting on its own.

Table 1 shows just a few of the most intriguing results. Each of the responses shown was produced from single token queries, yet some of the output of

Llemma-7B in response to a single token is apparently coherent. The responses to semantically meaningless queries can even include (as in the case of the penultimate entry of

Table 1) syntactically correct source code. This suggests that the data collection part of Algorithm 1 may be finding interesting glitch tokens [

27,

28,

29,

30].

5.4. Limitations

Our method, based on the use of topological embeddings, is fundamentally only sensitive to the topology of the input token embedding. Geometric information, such as the cosine or Euclidean distance between tokens, is not recovered. This is a feature of all embedding approaches [

17]. Because the token subspace is recovered up to homeomorphism, relationships between distances between nearby tokens are preserved, though the actual distance values may change dramatically. Any analysis that uses the embeddings produced by our approach must not assume the values themselves are those appearing within the original token subspace. For instance,

Table 2 compares the estimates of Ricci scalar curvature at each token of

Llemma-7B from [

2], which uses the original token embedding coordinates, with the estimates of the same quantity from the coordinates obtained from Algorithm 1. One can see that the quantiles are significantly different! It might be the case that under more restrictive conditions, which would apply to the Jacobians of

f and

g, these distances might be approximately recovered.

Under the assumption that the token embedding is not available, it is also likely that the probabilities of tokens are not directly available. Therefore, the practical use of Options (2) or (3) would require token sampling. Since there are very many tokens, the convergence of the distribution of tokens is unlikely to be fast. This is a dramatically more severe case than the sampling error exhibited by our Option (2), in which

entire distributions are aggregated. High sampling error means that the topology recovered by the method may differ from the true topology. It is known that sampling error of this kind (in the coordinates of points in a point cloud) has a definite impact on the estimation of topological features [

31,

32], but this is still an active area of research.

To find the coordinates of a given token, it is necessary to collect responses to a prompt including that token, which can incur nontrivial computational costs for a model with many more tokens than Llemma-7B. In our experiment, the main performance bottleneck was the prompting process itself. While collecting a single response is not onerous, collecting multiple responses for every token can be computationally demanding. That said, the prompting process scales linearly in the number of tokens and the number of samples to be collected, and these can all be run in parallel without change.

As we noted, it is infeasible to verify that topology up to homeomorphism is correctly recovered, even theoretically. As a considerably less demanding proxy, we verified that the dimension estimates were correctly recovered, though more accurate tests exist. For instance, Ref. [

31] presents a hypothesis testing framework for topology reconstruction using persistent homology. While this seems promising, severe performance limitations are present because persistent homology scales polynomially in both time and memory requirements with the dimension of the data [

33]. In our initial attempts at verification, we did try to use persistent homology to compare the original token subspace with our reconstruction. We were stymied by memory limitations of our computing hardware, due to the fact that the fiber dimensions of the token subspace of

Llemma-7B are typically large.

One might also consider a set of prompts that are longer than a single token, but only the token in a single position is varied. Theorem 1 is easily extended to handle such a case, so the topology of the token subspace will be embedded into the output. That said, while the topology of the embedded token subspace will be identical, its geometry will likely change. It remains an open question, and is the subject of ongoing research by the authors, to determine what geometric changes are to be expected using different prompt templates.