Abstract

Connectivist learning has emerged as a contemporary theory in technology-enhanced education, emphasising the importance of learners’ metacognitive skills to manage their learning within connected communities. Despite its growing relevance, limited empirical evidence discussing how learners’ metacognitive patterns interact with the development of learning communities. This study took the first step by empirically investigating the interplay between metacognition and social presence through reciprocal interactions on Bilibili, a learning social media platform in China. From a dataset of 4084 comments, 485 interactions were extracted and analysed using k-means clustering, followed by a chi-square test to explore associations with social presence interactions. The findings reveal that learners actively engage in metacognition processes, particularly planning, monitoring, and evaluating their learning, within connectivist environments. Furthermore, the dynamic exchange of ideas fosters continuous knowledge construction, supporting both lifelong and informal learning. Crucially, the interdependence between metacognition engagement and social presence not only underscores their role in achieving deep and sustainable learning but also highlights the evolving identity of online learners as network facilitators on social media platforms.

1. Introduction

Connectivist learning, or connectivism, is a theory that offers a framework for understanding learning in the digital age (Siemens, 2005). It acknowledges the central role of technologies and social networks in modern education, providing learners with access to diverse resources and distributed knowledge (Alam, 2023). Connectivism has significantly influenced online and lifelong learning (Mukhlis et al., 2024), particularly through social media platforms that enable learners to share personal experiences and knowledge anytime and anywhere (Aksal et al., 2013). The theory emphasises the importance of connections and networks in knowledge acquisition, as information is distributed among networks (Alam, 2023). Consequently, effective learning requires learners to navigate, connect, and synthesise information from multiple sources (Khushk et al., 2022), while also exercising autonomy in deciding when and how to learn, interact, and interact, and contextualise knowledge (Boyraz & Ocak, 2021).

Metacognition, defined as awareness of one’s learning processes and the strategic use of information to achieve learning goals (Flavell, 1979), is widely recognised as a key component of online learning (Rapchak, 2018). It positively predicts learners’ readiness for online learning (Karatas & Arpaci, 2021). Within connectivist learning, metacognition is especially critical: learners must integrate ideas from diverse sources, evaluate their understanding, and regulate their learning through interactions (Boyraz & Ocak, 2021; O’Brien et al., 2020). Connectivism assumes that learning is driven by autonomous engagement within networks and facilitated through community-generated interactions (Boyraz & Ocak, 2021). For such communities to thrive, cohesion is essential, encouraging knowledge sharing and collaborative meaning-making. Kop (2011) highlights the role of social presence in fostering community formation and sense of belonging, which in turn enhances engagement in a connectivist learning environment. Researchers have also explored the association between metacognition and social presence. For instance, R. Garrison (2022) emphasises the social dimension of metacognition in online learning, while D. R. Garrison and Akyol (2015) argue that “social presence creates the frame of reference for metacognition” (p. 34).

Despite its theoretical promise, connectivism remains underexplored empirically. Most studies rely on qualitative designs and literature reviews (Boyraz & Ocak, 2021). For instance, Alam (2023) describes connectivism as a paradigm in which knowledge is distributed among the networks of people, technologies, and communities. In addition, O’Brien et al. (2020) propose a metaliterary model that positions metacognition as a key element in enhancing connectivist learning in Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs). Wang et al. (2014) conceptualise connectivist interactions across four levels: operation, wayfinding, sensemaking, and innovation interactions. However, empirical evidence on how learners engage metacognitively within social media platforms remains limited. Furthermore, the relationship between metacognitive skill development and the facilitation of social presence in learning communities is not yet fully understood. Without such insights, educators or online designers may struggle to foster metacognition development or cultivate a cohesive learning community with social presence for sustainable learning.

To address this gap, the present study investigates reciprocal interactions within Bilibili’s learning channel, a prominent social media platform in China. Using learning analytics, we empirically examine patterns of learners’ metacognition during online interactions. We also explore how these patterns relate to the development of social presence in connectivist learning, employing chi-square tests to assess associations. Thus, two research questions are explored:

- What are the metacognitive patterns in Bilibili’s connectivist learning environment?

- Are there associations between metacognition patterns and social presence in Bilibili’s connectivist learning environment?

The findings of this study contribute to the empirical understanding of connectivism by proposing a new perspective of metacognition and social presence in online learning communities. First, learners in connectivist environments actively engage in metacognitive regulation, planning, monitoring, and evaluating their learning. This behaviour is supported by the affordances of digital platforms, which promote learner autonomy, exploration, and social-affective interaction. Metacognitive engagement also fosters sustainable learning, as interactions stimulate awareness and future learning needs. Second, we found a reciprocal relationship between metacognition and social presence. This interplay expands our understanding of how learning capabilities and environments co-evolve in a connectivist context. Sharing metacognition insights can strengthen the networked learning environment, while cohesive learning communities enhance learners’ metacognitive engagement. Ultimately, this dynamic underscores the paradigm shift that connectivism represents in the digital age, where technologies and networks not only support learning but also empower online learners to become facilitators of knowledge within social media platforms.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Connectivist Learning and Social Media Platforms

Connectivist learning explores how knowledge is acquired and shared in the networked digital age (Downes, 2010). Introduced by Siemens (2005) as “connectivism” and “connected knowledge,” this paradigm is underpinned by two key characteristics. First, knowledge is viewed as distributed among networks formed by learners, platforms, and technologies (Goldie, 2016). Consequently, learning becomes a dynamic and socially mediated process, flowing through connections among individuals and digital artefacts (Xu & Du, 2023). Second, connectivism reconfigures the roles and authority of instructors and learners, driven by advances in pedagogical technologies. Learners are empowered with autonomy to access dispersed knowledge, engaged according to their personal needs and contribute actively to knowledge creation and dissemination (Boyraz & Ocak, 2021; Mukhlis et al., 2024; O’Brien et al., 2020). This approach not only legitimises flexible learning behaviours in online learning environments (Abrams, 2013) but also supports educators to design instruction that reflects learners’ lived experience and evolving needs (Boyraz & Ocak, 2021).

The rise in Web 2.0 technologies, particularly social media platforms, has been instrumental in enabling connectivist learning. These platforms support real-time collaboration and communication across spatial and temporal boundaries (Hendricks, 2019). According to Kaplan and Haenlein (2010), social media fosters the creation and the exchange of user-generated content, facilitates social interactions, and promotes self-representation and connectivity. Crucially, learners gain access to diverse resources, are encouraged to navigate and utilise these resources to develop meaningful connections and knowledge (Alam, 2023). Empirical studies have emphasised the value of integrating connectivist learning into social media platforms. Alzaın (2019) examined how social media platforms support collaborative learning among university students within a connectivist framework. Hamada (2014) found that such platforms outperform the traditional online learning environments in cultivating students’ personal knowledge management skills, particularly in computing modules. More recently, Apoko and Waluyo (2025) investigated the experiences of 108 international undergraduate students using social media in an English module designed based on the connectivism principles. Their findings highlighted platforms, such as Instagram, Facebook, TikTok, and WhatsApp, as effective spaces for supporting authentic learning and access to diverse knowledge networks.

While connectivism offers a compelling framework for understanding learning in the digital age, researchers have raised important practical concerns regarding the assumption that all learners possess a high degree of autonomy and self-regulation (Kop, 2011). Baque et al. (2020), for example, argue that learners are expected to independently navigate a range of tools, networks, and communities essential for connectivist engagement. This expectation extends to making informed decisions about learning pathways and maintaining awareness of one’s own learning processes (Boyraz & Ocak, 2021). Consequently, metacognition emerges as a critical component of connectivist learning, underpinning learners’ ability to reflect on, monitor, and direct their learning. However, despite its theoretical prominence, there remains a notable gap in empirical research concerning how metacognition is enacted and supported within connectivist environments. Questions persist about the pedagogical strategies, technological scaffolds, and instructional designs that effectively foster metacognitive engagement in socially networked learning contexts.

2.2. Metacognition in Connectivist Learning

Metacognition is defined as “one’s knowledge concerning one’s own cognitive processes and products or anything related to them” (Flavell, 1979, p. 232). It is often conceptualised as a multidimensional set of learning capacities encompassing: (1) planning on learning resources and objectives; (2) recognition of one’s cognitive, emotional, and knowledge status; (3) controlling, monitoring, and evaluating the overall learning process (Akturk & Sahin, 2011; Paris & Winograd, 1990; Scott, 2008). Drawing on prior research, this study categorises metacognition into three core dimensions: metacognitive knowledge (Livingston, 2003), metacognitive experience (Efklides et al., 2017), and procedural metacognition (Schraw et al., 2006; Schraw & Moshman, 1995; Whitebread et al., 2009). Metacognitive knowledge refers to static, self-appraisal knowledge about one’s cognitive abilities and limitations, reflecting judgments about current knowledge status (Paris & Winograd, 1990). Metacognitive experience involves the subjective awareness of cognitive processes, enabling learners to make decisions about how to initiate or sustain learning (Efklides et al., 2017). The final category is procedural metacognition, which is the most recognisable dimension. It encompasses the entire learning cycle: identifying learning needs and goals, planning and selecting strategies, implementing learning activities, and evaluating outcomes to determine whether objectives have been achieved (Schraw et al., 2006; Schraw & Moshman, 1995; Whitebread et al., 2009).

Within the framework of connectivism for Web 3.0 and Higher Education, Boyraz and Ocak (2021) emphasise that “decision-making itself is a learning process” (p. 1127). Given the dynamic and distributed nature of knowledge, learners must continuously decide what to learn, how to learn, and how to regulate and assess their learning processes. Connectivist learning demands a high level of digital literacy and familiarity with learning networks to foster self-regulation and orientation (Littlejohn, 2013). In this context, metacognition emerges as a critical capacity, enabling learners to plan, monitor, and evaluate their learning, while remaining attuned to their cognitive and emotional states (Akturk & Sahin, 2011; Paris & Winograd, 1990). Moreover, connectivist theory posits that the fluidity of online learning environments requires learners to adapt to evolving technologies and synthesise information from diverse sources (Siemens, 2005). This necessitates heightened sensitivity to learning processes and spaces, as well as critical engagement with information resources (O’Brien et al., 2020). Consequently, researchers have called for increased attention to metacognition, noting that “metacognition captures the ability to reflect on how we think and learn, and students who apply metacognitive reflection, especially those who are highly self-regulated and accept responsibility for directing their own learning, are more effective learners” (Terras & Ramsay, 2015, p. 479). In light of these insights, metacognition should be recognised as a key learner capability. Investigating its patterns within connectivist learning environments is essential for advancing both theoretical understanding and pedagogical practice

2.3. Social Presence in Connectivist Learning

Connectivism emphasises that learning occurs within a network. The learning environment should be deliberately designed to encourage learners to connect, form discussion groups, and develop communities of practice (Marhan, 2006). It therefore advocates for a highly learner-centred approach to community building (Garcia et al., 2015). By gathering individuals with shared interests through interaction, collaboration, and reflection, learners gain access to the information they need (Siemens, 2005). Within this framework, social presence emerges as a central dimension.

The concept of social presence was first introduced by Short et al. (1976), who examined the role of media in facilitating verbal and nonverbal communication. Since then, social presence has gained prominence as a key component of Community of Inquiry (CoI) (D. R. Garrison et al., 1999), which integrates interdependent elements to foster effective online learning communities. CoI argues that social presence occurs when learners perceive themselves as socially engaged during learning, thereby enabling more interactive and cohesive responses (Swan et al., 2009). Within this theoretical framework, social presence is understood as supporting both “the cognitive and affective objectives of learning” (Kilis & Yıldırım, 2018, p. 54).

The importance of social presence in connectivism learning environments has been acknowledged by several researchers. Garcia et al. (2015) demonstrated through a conceptual connectivist learning blog model that the social presence of facilitators and participants fosters engagement and autonomy. Similarly, Kop (2011), analysing data from Moodle forums, wiki, participant blogs, and Twitter posts, concluded that social presence enhances community formation, strengthens a sense of belonging, and promotes learner engagement. Starr-Glass (2013) further argued that online learners encountering new information can be viewed as “a part of information and communication networks that connect her to others, particularly organisations and learning institutions” (p. 132). In this way, connectivist learning environment highlights the accumulation of social capital within networks and communities as learners interact, share, and build new knowledge. Consequently, social presence plays an essential role in creating cohesive learning networks in connectivist contexts.

2.4. Interactions of Metacognition and Social Presence in Connectivist Learning

Interactions are reciprocal activities that involve at least two objects or actions (Wagner, 1994), and are particularly significant for learning. As Downes (2010) argues, without interactions, learners might miss the opportunities for deeper learning and knowledge creation, since “interaction not only promotes human contact, it provides human content… it creates a deep layer of learning content that no developer could ever hope to create” (p. 48). Interaction also influences learners’ metacognitive development and supports subsequent self-regulated learning (Schnaubert et al., 2021). Several studies have highlighted the essential role of interaction in understanding learners’ metacognition across diverse learning contexts. For instance, Hurme et al. (2006) analysed student interactions in a knowledge forum during a geometry course to evaluate metacognition-related content. Peeters (2019) examined peer interactions on Facebook to explore how learners build networks and engage in cognitive, metacognitive, social, and organisational processes within a university-level foreign language curriculum. Similarly, Lobczowski et al. (2021) used interaction data from a collaborative app to demonstrate how pharmacy students construct metacognitive knowledge, skills, and experiences in a problem-solving course. More recently, Çini et al. (2023) assessed social interactions at varying levels of metacognitive awareness to explore the impact on collaborative problem-solving in a simulation module. Distinctively, Lu et al. (2024) examined informal learning settings on the video-based social media platform Bilibili in China, showing how the social interactions, both reflect and influence the metacognitive development of online learners over time. Collectively, these studies suggest that social interactions serve as a critical agent in investigating metacognition in social and digital learning environments.

Social presence originally conceptualised as a property of the communication system, has since evolved into a broader framework for understanding learning as a social process (Starr-Glass, 2013). Social interactions are widely recognised as the primary medium through which social presence can examined across different learning settings, including online community building in distance education (Chen & Bogachenko, 2022), formal online learning for undergraduate students (Miao et al., 2022), blended synchronous learning in engineering education (Szeto & Cheng, 2016), and foreign language curricula integrating Facebook (Peeters, 2019).

This study focuses on connectivism, which emphasises that learning events involve active engagement with resources and interactions among learners, rather than the one-way transmission of knowledge from instructors to learners (Kop, 2011). With integration becoming more open and extending beyond classroom boundaries, it is evolving into a more complex process that connects objects and people across diverse communities (Wang et al., 2014). Such openness fosters community development and enables learners to “jump across or cross boundaries” (Wang et al., 2014, p. 125). Boyraz and Ocak (2021) further describe connectivism as an epistemological approach grounded in interactions within networks, both internal (cognitive) and external (social).

From a pragmatic perspective, the role of online interactions facilitated by social technologies in connectivism has been increasingly acknowledged. For instance, Sozudogru et al. (2019) found that communication via blogs and Facebook effectively supports connectivist principles in language learning. Boyraz and Ocak (2021) emphasised that information is continuously updated through exchanges within learning communities. Wang et al. (2014) offered a detailed framework of connectivist interactions across four levels: operational (designing the learning environment), wayfinding (connecting information and people), sensemaking (developing networks, identities, and social presence through metacognitive processes), and innovation (creating new knowledge through reflection and negotiation). These stages illustrate how metacognition and social presence are embedded within the interactions that learners generate, reinforcing their centrality to connectivist learning.

2.5. Research Gap

Boyraz and Ocak (2021) highlighted that connectivism remains a relatively young learning theory with limited empirical studies. Although some studies have examined the integration of social media platforms into teaching and learning, most have focused either on learners’ perceptions of social media’s impact on their learning (e.g., Apoko & Waluyo, 2025; Sozudogru et al., 2019), or on the effectiveness of these platforms in supporting specific learning and teaching activities (e.g., Hamada, 2014; Haugsbakken & Langseth, 2014). Far less is known about how individuals engage metacognitively while learning on social media environments.

Similarly, the relationship between metacognition and social presence has received limited scholarly attention (Rowaida Mustafa, 2018). R. Garrison (2022) argued that several principles of metacognitive skill development, such as establishing communication, fostering cohesion, encouraging openness, building trust, and sustaining respect and responsibility, can also be seen as reflections of social presence. These elements are critical for metacognitive growth, yet empirical studies exploring this connection remain scarce. Consequently, R. Garrison (2022) posed the question of whether metacognitive development could enhance social presence and called for further empirical studies.

Addressing these questions is essential for advancing our understanding of how to strengthen online learners’ metacognitive capacity within connectivist learning environments. As Hendricks (2019) argued, connectivism supports individuals with new learning skills necessary to thrive the digital age. By connecting metacognition, representing individual learning capacity, with social presence, representing learners’ sense of belonging within communities, instructors and system designers can better understand how learning processes and community development interact to create more sustainable digital learning environment.

Building on this literature, the present study investigates patterns of metacognition and explored the association between metacognition and social presence as reflected in social interactions. The data were gathered from the communication generated in the comment areas of a video-based learning channel on one of China’s most promising social media platforms (Bilibili).

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Context

Bilibili was selected as the platform for data collection and analysis. Officially launched in June 2009, it has since developed into a leading video community with the mission of enriching the everyday lives of younger generations in China (Bilibili, 2023). The platform enables users to upload video clips for public viewing, with each video hosted on an independent page. Beneath each video, registered users can engage through written comments or by posting danmaku (real-time, on-screen) comments. In the first quarter of 2023, these interactive features generated approximately 14.2 billion monthly interactions (Bilibili, 2023). Beyond entertainment, Bilibili has emerged as a promising community for learning and knowledge sharing. According to People’s Daily Online (2021), more than one thousand users have contributed knowledge-based videos, and educational or learning-related content accounts for nearly 45% total views.

For this study, the learning channel, “An interdisciplinary module for young people” (https://b23.tv/3gHLYs4, accessed on 1 November 2024), was chosen for analysis. This channel was selected because it had been consistently nominated as one of the most popular learning channels on Bilibili. More importantly, it offers a wide-ranging curriculum that spans communication, systems, self-management, brain science, marketing, and economics. Sucha diversity attracts varied audience groups encouraging multiple forms of interaction. Table 1 presents the number of comments recorded for each episode as of 1 November 2024, the date of data collection.

Table 1.

Episodes and number of comments.

3.2. Data Collection and Coding

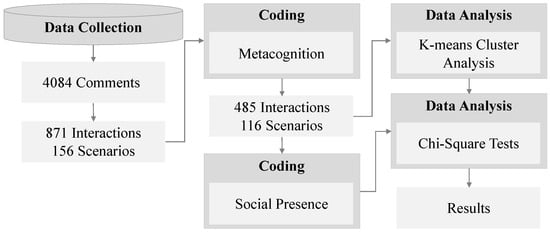

The present study employed online written discourse as the basis for coding. Previous research has adopted similar methods, analysing comments from video-based learning channels on social media platforms to investigate how interactions influence learning (e.g., Benson, 2015; Bou-Franch et al., 2012; Dubovi & Tabak, 2020). Figure 1 outlines the data collection and analysis procedures. First, all comments were extracted using Python 3.9 with the essential metadata such as commenter IDs, timestamps, and episodes titles, and subsequently stored in Excel for further processing. At this stage, 4084 comments were collected. Second, in line with the definition of interactions, only reciprocal exchanges involving at least two individuals, where one user posted a comment and another replied, were retained. Each original comment and its associated replies were treated as a single scenario. This process yields 871 interactions, grouped into 156 scenarios, which were then coded.

Figure 1.

Data collection, coding, and analysis steps.

For the coding of metacognition, the relevant interactions were analysed coding scheme proposed by Lu et al. (2024) to identify metacognition-related variables (see Table 2). Each comment and its corresponding reply were classified into one of the six subcategories outlined in the scheme. Only the interactions that exhibited these subcategories were retained for analysis. In total, 485 interactions with 116 scenarios were selected.

Table 2.

Coding scheme of metacognition.

Following qualitative coding, the data were transformed for quantitative pattern analysis. Each of the 116 scenarios was represented as a numerical vector capturing the frequency counts of the six metacognitive dimensions (MK, AW, PL, MO, EV, ME). This process generated a dataset in which the metacognitive composition of each scenario could be mathematically compared and clustered. Euclidean distance was used as the similarity measure, and clustering was performed with the k-means algorithm implemented in Python’s scikit-learn package.

For social presence, the data were coded using the CoI coding template for informal learning developed by Chatterjee and Parra (2022) (see Table 3). The scheme comprises three categories: emotional expression, open communication, and group participation. Emotional expression refers to the display of emotions through playful language, repeated punctuation, emojis, or capitalised letters. Open communication captures comments that convey confidence, confusion, comfort, or confession. Group participation involves inviting and encouraging others to engage, contribute, or share opinions. Each scenario’s social presence was defined as a binary variable, indicating whether social presence was observed during interaction. Of the 116 scenarios, 48 were coded as “Yes” and the remaining scenarios as “No”. The first author coded all the selected interactions, while a second rater independently coded 35% of the data. Disagreements were discussed and resolved. Disagreements were discussed and resolved. Interrater reliability was assessed using Cohen’s Kappa, which indicated good agreement, ranging from 0.75 (ME) to 0.89 (PL), with an overall value of 0.77.

Table 3.

Coding scheme of social presence.

3.3. Data Analysis

K-means cluster analysis, an unsupervised machine learning technique, was used to explore patterns of metacognition by clustering interaction scenarios according to their proximal similarities (Perrotta & Williamson, 2018). Scenarios were clustered based on the frequency of each metacognitive category identified in reciprocal interactions. The analysis was conducted using the K-means algorithm from Python’s scikit-learn package. To determine the optimal number of clusters, the sum of squared errors (SSE) was used, which calculates the squared Euclidean distances of each point to its nearest centroid. In this study, the minimum SSE indicated that three clusters were optimal. Accordingly, 116 scenarios were allocated to three clusters. Following cluster formation, a chi-square test was used to examine the association between metacognition and social presence.

4. Results

4.1. What Is the Pattern of Metacognition in the Interactions of the Connectivism Learning Environment of Bilibili?

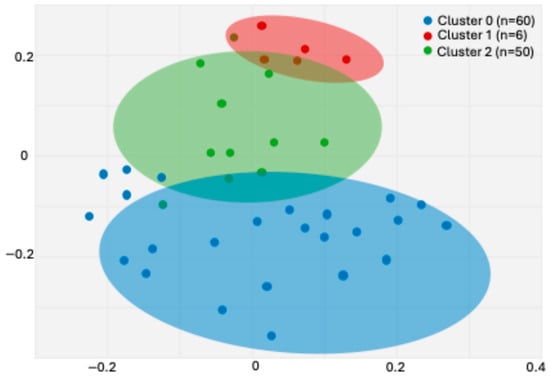

Three clusters were identified, with all 116 scenarios allocated according to their metacognition patterns. The results of the k-means clustering analysis are illustrated in Figure 2. The clusters were labelled 0, 1, and 2, each represented by a different colour. Table 4 provides detailed information on the six dimensions of metacognition within each cluster, including the mean, standard deviation, and the observed maximum and minimum frequencies.

Figure 2.

K-means clustering analysis result.

Table 4.

Details on the frequency of each metacognition-related dimension for each cluster.

Cluster 0 comprised 60 scenarios, accounting for 51.7% of the total. This cluster exhibited the lowest frequencies across all metacognition-related dimensions, with an overall average of 0.26. Within this cluster, planning was the most frequently observed dimension, followed by evaluation and monitoring. No evidence of metacognitive knowledge was identified.

Cluster 1 included six scenarios (5.17%) and demonstrated the highest frequencies across all six dimensions, with an overall average of 2. Planning and evaluation were the most prominent dimensions, while a smaller number of scenarios reflected metacognitive experience, monitoring and awareness. Metacognitive knowledge remained the least frequent dimension in this cluster.

Cluster 2 contained 50 scenarios and presented moderate frequencies across dimensions compared to Clusters 0 and 1. As in the other clusters, planning and evaluation were the two most frequently observed dimensions, though at lower levels than in Cluster 1. No awareness patterns were recorded, and metacognitive knowledge appeared only rarely.

In summary, the empirical results show that procedural metacognition, particularly planning, monitoring, and evaluation, was most prevalent across all three clusters, whereas metacognitive knowledge and awareness were observed least frequently.

4.2. Are There Any Associations Between the Pattern of Metacognition and Social Presence in the Interactions of the Connectivism Learning Environment of Bilibili?

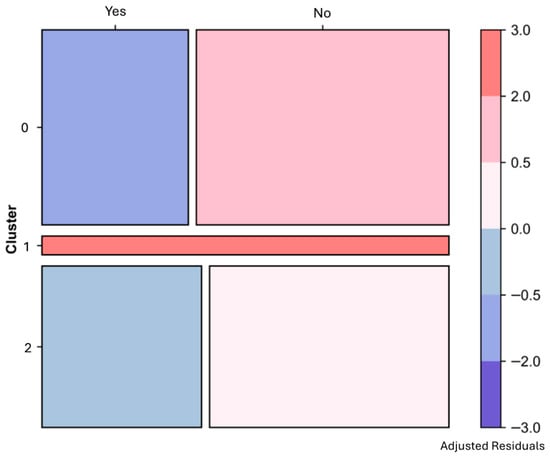

Chi-square analysis was conducted to examine differences among clusters in the performance of social presence. The presentation of social presence was coded as a binary variable: present (Yes) or absent (No). The analysis revealed a statistically significant difference in the distribution of social presence across cluster, χ2 = 9.089, df = 3, p = 0.011. Table 5 provides detailed results of the chi-square analysis. Specifically, the adjusted residuals for Cluster 1 exceeded ±1.96, indicating a significant association between metacognition patterns and social presence at the 0.05 significance level. In contrast, the adjusted residuals for Cluster 0 and Cluster 2 were below ±1.96, suggesting no significant association between metacognition and social presence in these clusters.

Table 5.

Chi-square analysis result.

To enhance the interpretability of the results, a mosaic plot was developed (Figure 3) to illustrate the chi-square analysis of the association between metacognition and social presence. Consistent with Table 5, the plot shows that more than half of the scenarios (58.6%) did not exhibit social presence. Among the three clusters, Cluster 1 was distinctive in that all six scenarios demonstrated social presence-related interactions. This aligns with the findings from the first research question, where Cluster 1 also presented the highest frequencies across all metacognitive dimensions. In Cluster 0, 36.7% of the 60 scenarios displayed social presence, a proportion slightly lower than that Cluster 2, where 40% of the 50 scenarios included social presence. Table 6 further integrates these results by summarising the cluster profiles, combining metacognition patterns with their associations to social presence.

Figure 3.

Mosaic plot of chi-square analysis results on the association between metacognition and social presence.

Table 6.

Cluster profiles integrating metacognition patterns and association with social presence.

5. Discussion

The present study proposes a new theoretical perspective on connectivism learning by highlighting the essential roles of metacognition as a core capability of online learners, alongside the contribution of learning communities enriched by social presence. These elements deepen our understanding of connectivist learning on social media platforms. While the correlational design employed cannot establish causality, the findings enable theorisation about the nature of the relationship. Metacognition has been defined as a key learning capacity (O’Brien et al., 2020) and connected learning communities are considered necessary to support connectivist learning in social media contexts (Marhan, 2006). However, empirical studies have largely overlooked the social dimension of metacognition, particularly its relationship with social presence (R. Garrison, 2022; Rowaida Mustafa, 2018). Addressing this gap, the present study explored patterns of metacognition and their associations with social presence based on the interactions within a video-based learning channel. By applying learning analytics techniques, the study revealed the interaction patterns that connect learners’ metacognitive processes with social presence in a connectivism environment. Three clusters of interaction scenarios emerged from the analysis, based on the six dimensions of metacognition. Planning, monitoring, and evaluation were the most frequently observed, while metacognitive knowledge and awareness were least represented. Cluster 1 exhibited the highest frequencies of planning (PL) and evaluation (EV) (see Table 4), suggesting that learners in highly metacognitive scenarios actively structure their learning. This finding aligns with Wang et al. (2014), who theorised that sensemaking interactions involve critical evaluation. However, our data extend this model by showing that planning is not an isolated cognitive activity but is deeply social, as evidenced by its significant association with social presence in the chi-square analysis. These results contrast with those of Hurme et al. (2006) and Peeters (2019), who did not identify planning-related patterns in social interactions within a formal online learning environment. In those studies, learning was designed and organised by instructors, leaving limited space for learner agency. By contrast, our findings demonstrate that connectivist learning on social media platforms is unstructured, with knowledge distributed across networks (Bozkurt, 2023). Learners therefore assume greater responsibility for directing their own learning, including resource investigation, evaluation, dissemination, and process control in highly distributed environments (Baque et al., 2020; Boyraz & Ocak, 2021). This autonomy encourages learners to establish their own schedules and strategies, often motivated by peer interactions.

Monitoring and evaluation were the second and third most frequent dimensions. This differs from findings in formal learning contexts, where students rarely engage in peer-based evaluation or monitoring (Cheng & Hou, 2015; Hurme et al., 2006; Peeters, 2015). Connectivist learning on social media platforms may foster these practices by enabling learners to interact socially and informally, thereby negotiating learning processes and assessing progress through affective and communicative exchanges (Kumpulainen & Rajala, 2017).

In contrast, awareness was rarely observed. Awareness captures reciprocal interactions in which learners’ needs are triggered by others. In this dataset, such interactions were often coded as the evaluation dimension (i.e., the highest frequency of the metacognition dimension observed), since learners’ intentions were modified or updated through peer exchanges. This provides empirical support for Wang et al.’s (2014) framework of interaction and cognitive engagement, showing that interactions not only contribute to content development but also facilitate the modification and continuous updating of learning needs. This dynamic process underscores the potential of connectivist learning to support lifelong learning, achieved through ongoing expansion and refinement of knowledge (Mukhlis et al., 2024; Siemens, 2005). It also emphasised the role of informal learning, which extends beyond formal institutions to occur anywhere and anytime through access to digital resources and communities (Kop & Hill, 2008).

Finally, the findings confirmed differences in metacognition patterns between scenarios with and without social presence. The evidence suggests a co-constructive process in which metacognition and social presence mutually reinforce one another. All six scenarios in Cluster 1, which exhibited the highest frequencies across all metacognition dimensions, also demonstrated social presence. This indicates that learners are more likely to engage in deep planning, monitoring, and evaluation when the learning environment fosters emotional expression, open communication, and group participation. Cluster 2, with moderate metacognition, also showed more social presence than Cluster 0, which had the lowest frequencies. These results suggest that sharing metacognitive strategies, such as articulating plans, monitoring progress, and evaluating outcomes, is inherently social, contributing to open communication and a sense of community. This reciprocal relationship supports R. Garrison’s (2022) argument that metacognitive awareness enhances open communication through reflection and discourse. In connectivist learning, social presence provides the “frame of reference” (p. 34) that strengthens and sustains metacognitive exchanges (D. R. Garrison & Akyol, 2015).

The high frequencies of metacognition-related patterns observed in this study also reflect the third and fourth stages of cognitive engagement in connectivist learning, sensemaking and innovation interaction, which promote critical evaluation, in-depth reflection, decision-making, and meaning-making as illustrated by Wang et al. (2014). Within a connectivist framework, our findings suggest that deep learning, fostered through the development and sharing of metacognitive processes, contributes to a more cohesive learning environment. On social media platforms, learners are required to investigate diverse digital resources across multiple networks and construct their learning by forming connections and relationships through the social tools afforded by these platforms. This underscores the new perspectives advanced by connectivism as a learning theory in the digital age, emphasising the centrality of networks and technologies in learning.

More importantly, the dynamic interplay between metacognition development and social presence reveals that online learners are not only knowledge investigators and distributors but also network facilitators within social media learning environments (e.g., Boyraz & Ocak, 2021; Mukhlis et al., 2024; O’Brien et al., 2020). Our empirical evidence indicates that cohesive networks and communities are co-constructed when learners engage metacognitively by shaping their social roles on these platforms. This reflects the connectivist view of networks as extensions of the mind, rather than merely social media spaces for interaction, as posited by social constructivism (Wang et al., 2014). Consequently, connectivism requires learners to develop the capacity to construct and traverse networks (Downes, 2010) rather than simply participate in them for communication.

5.1. Implications

The findings of this study have practical implications for educators and online designers seeking to facilitate effective online learning. First, learners in connectivist environments actively demonstrated metacognition in planning and evaluation, indicating a natural exercise of agency. Rather than imposing rigid structures, educators should consider creating flexible, resource-rich online spaces that support and extend this tendency toward self-directed exploration. Learners should be provided with greater opportunities to determine and pursue their own learning pathways, as knowledge in the digital age resides within distributed environments and must be accessed through active participation (Conradie, 2014).

Second, metacognition interactions were frequently associated with the articulation of learning needs. This suggests a potential strategy for sustaining engagement: analysing these interactions can serve as a real-time indicator of evolving learner interests. Online designers could leverage such insights to better understand users’ emerging needs, thereby encouraging continued participation and longer engagement with learning channels or social media platforms.

Third, the significant association between high metacognition and social presence observed in Cluster 1 implies that these two elements may be mutually reinforcing in connectivist contexts. Instructional activities should therefore be designed to integrate social and metacognitive goals simultaneously. For example, online instructors might initiate metacognitive dialogue while fostering social presence by inviting learners to share their reflective learning processes on complex topics through open communication.

5.2. Limitations

The present study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, due to restrictions in data availability, we were unable to collect information on registered users’ personal characteristics, such as gender, ethnicity, motivation, and learning persistence. Future research could address this limitation by targeting specific student groups within comparable online learning contexts and incorporating pre-surveys to capture these variables. Second, the analysis was limited to a single learning channel, albeit one that covered a wide range of topics. Subsequent studies may benefit from including multiple channels to examine whether variations in interaction patterns, and consequently in metacognition, are influenced by differences in learning topics or disciplinary contexts.

Third, our analysis was grounded in the CoI Framework, which provided a validated structure for evaluating constructions in online learning environments. Future research could extend this approach by applying Goffman’s (2017) interaction ritual framework to uncover the nuanced social dynamics of connectivist learning environments. Such an approach may reveal how learners maintain mutual respect and social equilibrium, curate digital identities, and employ modern interaction rituals to validate membership and reinforce shared values and community order.

Finally, social presence was operationalised as a binary variable, which is inherently reductive given its multidimensional nature. Future studies could adopt a multi-level coding scheme to capture the richness and varying degrees of intensity in social presence, thereby offering a more comprehensive understanding of its association with metacognition.

6. Conclusions

This study advances our understanding of connective learning on social media by foregrounding the dynamic interplay between metacognition and social presence. Through a metacognitive lens, it demonstrates how learners not only regulate their cognitive processes but also co-construct knowledge and community through socially embedded interactions. The identification of distinct interaction clusters, alongside the differentiation between formal and informal learning contexts, underscores the complexity and richness of online learning environments. Ultimately, the findings highlight that when learners share metacognitive strategies, they foster deeper learning, strengthen social bonds, and contribute to vibrant, self-sustaining learning communities. This integrated perspective provides valuable insights for the design of more effective and socially attuned digital learning experiences.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, H.L., X.Z. and M.L.; methodology, H.L.; validation, X.Z. and M.L.; formal analysis, H.L. and X.Z.; investigation, X.Z. and M.L.; resources, H.L.; data curation, H.L.; writing—original draft preparation, H.L. and M.L.; writing—review and editing, H.L., X.Z. and M.L.; supervision, X.Z. and M.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study has been approved by the Ethics Review Panel of anonymous for the review, ER-LRR-0010000051620231218110424, with the approval date of 22 December 2023.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived for this study. The research involved the analysis of existing, publicly accessible textual data (user comments) from the Bilibili platform, in accordance with its terms and conditions. The study was conducted without any interaction with human subjects and did not involve the collection of any personal, sensitive, or identifiable information. All data were anonymised and aggregated during analysis to ensure the privacy and confidentiality of the individuals. The waiver was granted because the research posed no more than minimal risk, as it involved the analysis of pre-existing public data rather than interactive methods like interviews or focus groups.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abrams, S. S. (2013). Peer review and nuanced power structures: Writing and learning within the age of connectivism. E-Learning and Digital Media, 10(4), 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksal, F. A., Gazi, Z. A., & Bahçelerli, N. M. (2013). Practice of connectivism as learning theory: Enhancing learning process through social networking site (Facebook). Gaziantep University Journal of Social Sciences, 12(2), 243–252. [Google Scholar]

- Akturk, A. O., & Sahin, I. (2011). Literature review on metacognition and its measurement. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences, 15, 3731–3736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M. A. (2023). Connectivism learning theory and connectivist approach in teaching and learning: A review of literature. Bhartiyam International Journal of Education and Research, 12, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Alzaın, H. A. (2019). The role of social networks in supporting collaborative e-learning based on connectivism theory among students of PNU. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education, 20(2), 46–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apoko, T. W., & Waluyo, B. (2025). Social media for English language acquisition in Indonesian higher education: Constructivism and connectivism frameworks. Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 11, 101382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baque, P. G. C., Cevallos, M. A. M., Natasha, Z. B. M., & Lino, M. M. B. (2020). The contribution of connectivism in learning by competencies to improve meaningful learning. International Research Journal of Management, It and Social Sciences, 7(6), 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, P. (2015). Commenting to learn: Evidence of language and intercultural learning in comments on YouTube videos. Language Learning and Technology, 19(3), 88–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilibili. (2023). Bilibili investor presentation. Bilibili investor home. Available online: https://ir.bilibili.com/media/ckxl4gyp/q1-2023-bilibili-inc-investor-presentation.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Bou-Franch, P., Lorenzo-Dus, N., & Blitvich, P. G.-C. (2012). Social interaction in YouTube text-based polylogues: A study of coherence. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 17(4), 501–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyraz, S., & Ocak, G. (2021). Connectivism: A literature review for the new pathway of pandemic driven education. International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology, 6(2), 1122–1129. [Google Scholar]

- Bozkurt, A. (2023). Using social media in open, distance, and digital education. In O. Zawacki-Richter, & I. Jung (Eds.), Handbook of open, distance and digital education (pp. 1237–1254). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee, S., & Parra, J. (2022). Undergraduate students engagement in formal and informal learning: Applying the community of inquiry framework. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 50(3), 327–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. L., & Bogachenko, T. (2022). Online community building in distance education: The case of social presence in the Blackboard discussion board versus multimodal VoiceThread interaction. Educational Technology & Society, 25(2), 62–75. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, K.-H., & Hou, H.-T. (2015). Exploring students’ behavioural patterns during online peer assessment from the affective, cognitive, and metacognitive perspectives: A progressive sequential analysis. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 24(2), 171–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conradie, P. W. (2014). Supporting self-directed learning by connectivism and personal learning environments. International Journal of Information and Education Technology, 4(3), 254–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çini, A., Järvelä, S., Dindar, M., & Malmberg, J. (2023). How multiple levels of metacognitive awareness operate in collaborative problem solving. Metacognition and Learning, 18(3), 891–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downes, S. (2010). Learning networks and connective knowledge. In Collective intelligence and e-learning 2.0: Implications of web-based communities and networking (pp. 1–26). IGI Global. [Google Scholar]

- Dubovi, I., & Tabak, I. (2020). An empirical analysis of knowledge co-construction in YouTube comments. Computers and Education, 156, 103939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efklides, A., Schwartz, B. L., & Brown, V. (2017). Motivation and affect in self-regulated learning: Does metacognition play a role? In D. H. Schunk, & J. A. Greene (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation of learning and performance (2nd ed., pp. 64–82). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Flavell, J. H. (1979). Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: A new area of cognitive–developmental inquiry. American Psychologist, 34(10), 906–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, E., Elbeltagi, I., Brown, M., & Dungay, K. (2015). The implications of a connectivist learning blog model and the changing role of teaching and learning. British Journal of Educational Technology, 46(4), 877–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrison, D. R., & Akyol, Z. (2015). Toward the development of a metacognition construct for communities of inquiry. Internet and Higher Education, 24, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (1999). Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education. Internet and Higher Education, 2(2–3), 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrison, R. (2022). Shared metacognition in a community of inquiry. Online Learning, 26(1), 6–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffman, E. (2017). Interaction ritual: Essays in face-to-face behavior. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Goldie, J. G. S. (2016). Connectivism: A knowledge learning theory for the digital age? Medical Teacher, 38(10), 1064–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamada, A. (2014). The impact of designing a collaborative e-learning environment based on Web 2.0 tools according to the connectivism theory and the development of personal knowledge management skills. Arab Studies in Education and Psychology, 56, 81–148. [Google Scholar]

- Haugsbakken, H., & Langseth, I. D. (2014, July 15–18). YouTubing: Challenging traditional literacies and encouraging self-organisation and connecting in a connectivist approach to learning in the K-12 system. Paper presented at the 9th International Conference on e-Learning, Lisbon, Portugal. [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks, G. P. (2019). Connectivism as a learning theory and its relation to open distance education. Progressio, 41(1), 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurme, T.-R., Palonen, T., & Järvelä, S. (2006). Metacognition in joint discussions: An analysis of the patterns of interaction and the metacognitive content of the networked discussions in mathematics. Metacognition and Learning, 1(2), 181–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, A. M., & Haenlein, M. (2010). Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of Social Media. Business Horizons, 53(1), 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatas, K., & Arpaci, I. (2021). The role of self-directed learning, metacognition, and 21st century skills predicting the readiness for online learning. Contemporary Educational Technology, 13(3), ep312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khushk, A., Dacholfany, M. I., Abdurohim, D., & Aman, N. (2022). Social learning theory in clinical setting: Connectivism, constructivism, and role modeling approach. Health Economics and Management Review, 3(3), 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilis, S., & Yıldırım, Z. (2018). Investigation of community of inquiry framework in regard to self-regulation, metacognition and motivation. Computers and Education, 126, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kop, R. (2011). The challenges to connectivist learning on open online networks: Learning experiences during a massive open online course. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 12(3), 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kop, R., & Hill, A. (2008). Connectivism: Learning theory of the future or vestige of the past? The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 9(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumpulainen, K., & Rajala, A. (2017). Negotiating time-space contexts in students’ technology-mediated interaction during a collaborative learning activity. International Journal of Educational Research, 84, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littlejohn, A. (2013). Understanding massive open online courses. Caledonian Academy Glasgow Caledonian University. [Google Scholar]

- Livingston, J. A. (2003). Metacognition: An overview. Psychology, 12(5), 259–266. [Google Scholar]

- Lobczowski, N. G., Lyons, K., Greene, J. A., & McLaughlin, J. E. (2021). Socially shared metacognition in a project-based learning environment: A comparative case study. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 30, 100543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H., Limniou, M., & Zhang, X. (2024). Exploring the metacognition of self-directed informal learning on social media platforms: Taking time and social interactions into consideration. Education and Information Technologies, 30, 5105–5132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marhan, A.-M. (2006). Connectivism: Concepts and principles for emerging learning networks. In Proceedings of the 1st international conference on virtual learning (pp. 209–216). Faculty of Mathematics and Computer Science. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, J., Chang, J. M., & Ma, L. (2022). Teacher-student interaction, student-student interaction and social presence: Their impacts on learning engagement in online learning environments. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 183(6), 514–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukhlis, H., Haenilah, E. Y., Maulina, D., & Nursafitri, L. (2024). Connectivism and digital age education: Insights, challenges, and future directions. Kasetsart Journal of Social Sciences, 45(3), 1001–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, K. L., Forte, M., Mackey, T. P., & Jacobson, T. E. (2020). Metaliteracy as pedagogical framework for learner-centered design in three MOOC platforms: Connectivist, coursera and canvas. Open Praxis, 9(3), 267–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, S. G., & Winograd, P. (1990). Promoting metacognition and motivation of exceptional children. Remedial and Special Education, 11(6), 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, W. (2015). Metacognitive awareness in foreign language learning through Facebook: A case study on peer collaboration. Dutch Journal of Applied Linguistics, 4(2), 174–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, W. (2019). The peer interaction process on Facebook: A social network analysis of learners’ online conversations. Education and Information Technologies, 24(5), 3177–3204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- People’s Daily Online. (2021). Educational content gains wider popularity on video-sharing platforms—People’s daily online. People’s daily. Available online: http://en.people.cn/n3/2021/1103/c90000-9915234.html (accessed on 8 June 2024).

- Perrotta, C., & Williamson, B. (2018). The social life of learning analytics: Cluster analysis and the “performance” of algorithmic education. Learning, Media and Technology, 43(1), 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapchak, M. E. (2018). Collaborative learning in an information literacy course: The impact of online versus face-to-face instruction on social metacognitive awareness. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 44(3), 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowaida Mustafa, J. (2018). Exploring the relations between social presence and individual and social/shared metacognition in learners within a global graduate online programme. The University of Liverpool. [Google Scholar]

- Schnaubert, L., Krukowski, S., & Bodemer, D. (2021). Assumptions and confidence of others: The impact of socio-cognitive information on metacognitive self-regulation. Metacognition and Learning, 16(3), 855–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schraw, G., Crippen, K. J., & Hartley, K. (2006). Promoting self-regulation in science education: Metacognition as part of a broader perspective on learning. Research in Science Education, 36(1), 111–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schraw, G., & Moshman, D. (1995). Metacognitive theories. Educational Psychology Review, 7(4), 351–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, B. M. (2008). Exploring the effects of student perceptions of metacognition across academic domains [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Indiana University.

- Short, J., Williams, E., & Christie, B. (1976). The social psychology of telecommunications. Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Siemens, G. (2005). Connectivism: Learning as network-creation. ASTD Learning News, 10(1), 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Sozudogru, O., Altinay, M., Dagli, G., Altinay, Z., & Altinay, F. (2019). Examination of connectivist theory in English language learning: The role of online social networking tool. International Journal of Information and Learning Technology, 36(4), 354–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starr-Glass, D. (2013). From connectivity to connected learners: Transactional distance and social presence. In C. Wankel, & P. Blessinger (Eds.), Increasing student engagement and retention in e-learning environments: Web 2.0 and blended learning technologies (Vol. 6, pp. 113–143). Emerald Group Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swan, K., Garrison, D. R., & Richardson, J. C. (2009). A constructivist approach to online learning: The community of inquiry framework. In Information technology and constructivism in higher education: Progressive learning frameworks (pp. 43–57). IGI Global. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szeto, E., & Cheng, A. Y. N. (2016). Towards a framework of interactions in a blended synchronous learning environment: What effects are there on students’ social presence experience? Interactive Learning Environments, 24(3), 487–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terras, M. M., & Ramsay, J. (2015). Massive open online courses (MOOCs): Insights and challenges from a psychological perspective. British Journal of Educational Technology, 46(3), 472–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, E. D. (1994). In support of a functional definition of interaction. American Journal of Distance Education, 8(2), 6–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z., Chen, L., & Anderson, T. (2014). A framework for interaction and cognitive engagement in connectivist learning contexts. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 15(2), 121–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitebread, D., Coltman, P., Pasternak, D. P., Sangster, C., Grau, V., Bingham, S., Almeqdad, Q., & Demetriou, D. (2009). The development of two observational tools for assessing metacognition and self-regulated learning in young children. Metacognition and Learning, 4(1), 63–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y., & Du, J. (2023). What participation types of learners are there in connectivist learning: An analysis of a cMOOC from the dual perspectives of social network and concept network characteristics. Interactive Learning Environments, 31(9), 5424–5441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).