Abstract

This study explores the perceptions of U.S. college-level language teachers regarding students’ readiness for online language learning. Drawing on a sequential explanatory mixed-methods approach, quantitative data were collected from 309 language teachers via an online survey, and qualitative data were collected from follow-up interviews with 21 respondents. The study identifies three key components of perceived student readiness: access and technological competence, self-responsibility, and use of support for online learning. In response to concerns regarding students’ responsibility, teachers reported that they employed strategies aimed at building trust and promoting student ownership of the language learning process. The findings also highlight the interplay between perceived student readiness and teachers’ self-confidence and their perceived value of online language teaching. Further, perceived student readiness shaped teachers’ increased willingness to adopt online and hybrid language teaching in the future.

1. Introduction

The expansion of online teaching in tertiary education has long stimulated research interest in student readiness. In the broader field of online learning, studies have examined student readiness through its proposed key components and their interaction with other perceptual variables, such as students’ self-confidence (e.g., Martin et al., 2020). However, compared to the decade-long history of general online education, online language teaching is still in its nascent stage. This distinction is important, as the unique communicative and interactive demands of language acquisition have historically led to resistance among educators and stakeholders toward adopting the online modality (e.g., Goertler, 2019). Nevertheless, despite being recognized as crucial contributors to success in online language learning, student-related factors such as their technology access, online learning competence, and attitudes were not uniformly integrated into the concept of “student readiness” (Winke & Goertler, 2008). As a result, given the limited implementation of online language courses prior to 2020, research on student readiness has been sparse.

Between 2020 and 2021, the global shift to remote teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic forced the language teaching field into its first large-scale experiment with online delivery. Although a few studies have since examined students’ online language learning preparedness (Cho, 2021; Rüschoff, 2024), systematic investigations remain limited. This study contends that students’ readiness to learn languages online warrants independent investigation. Importantly, due to the interactive nature of language teaching, students’ online readiness in language courses likely impacts how teachers perceive the online modality and their own confidence and attitude. Consequently, investigating student readiness is particularly significant as we explore the future of online language teaching, considering the preparedness and willingness of teachers and students.

The present study was conducted from late 2021 to early 2022, involving surveys and interviews with language teachers in tertiary education settings across the United States. Although remote teaching at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic was an emergency crisis response, the subsequent long-term use of the online modality reduced the unplanned nature of instruction, thereby creating an educational context approximating formal online teaching (e.g., Huang & Zhang, 2025). This context provided an unprecedented opportunity to study how student readiness and teacher perceptions co-evolved when the educational environment experienced rapid technology adoption. Given the ongoing, quick transformation of our educational landscape by technology-enhanced pedagogy and innovative tools, understanding the interplay of teachers’ perception of student preparedness and their own attitudinal factors while they adapt is of crucial significance.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Student Readiness for Online Language Learning: An Underdeveloped Domain

Students’ preparedness for general online learning has been explored in previous survey studies of students’ self-perceptions (e.g., Yu & Richardson, 2015). Many universities also implement self-assessment quizzes for students (e.g., University of Arkansas Online, n.d.). But no consensus has been reached on the specific components that constitute students’ online learning readiness. Based on an examination of survey instruments in 17 earlier studies, Martin et al. (2020) suggested that student attributes, time management, technical competencies, and communication competencies are four aspects of the concept. Student attributes refer to students’ “self-regulated learning, self-directed learning” and “developing and following goals to complete assigned work, being self-disciplined with their coursework, learning new technologies, and utilizing resources when questions arise” (Martin et al., 2020, p. 42). Time management refers to students’ ability to keep up with course assignments and deadlines with minimal reminders. Technical competencies reflect students’ “computer skills, Internet skills, and information-seeking skills.” Finally, communication competency refers to their abilities and confidence “to connect and communicate” with others via emails, discussion boards, etc. Although some scholars’ proposals largely corresponded to Martin et al.’s (2020) framework (e.g., Ware, 2018), different categorizations also existed. For instance, Hung et al. (2010) considered time management to be a sub-skill within “self-directed learning.”

Crucially, although research on general online learning readiness has laid foundational work, student preparedness for online learning is often insufficient for successful online language learning. Students with high digital literacy still encounter technological challenges for specific language learning tasks (Goertler et al., 2012). Furthermore, language teachers may perceive the online modality as less facilitative to interpersonal communication, which is fundamental to language learning. These perceived technological constraints may trigger concerns for reduced student engagement, resulting in language instructors’ hesitation to adopt an online modality. Thus, students’ online language learning readiness should be recognized as a concept distinct from general online readiness. Having established this, the remainder of the paper uses the term “student readiness” to exclusively refer to readiness for online language learning.

Before 2020, few empirical studies on this domain-specific student readiness existed. Student-facing surveys generally found students to hold ambivalent attitudes and preparedness towards online language learning. LaMance (2012) surveyed 210 students and 4 instructors in a French hybrid course, focusing on students’ and teachers’ language use and competence and their time management, among others. That study reported insufficient student autonomy and poor subject-specific technology readiness: even though 80% of the students self-reported as familiar with the technologies used in the hybrid courses, almost half of them admitted to being confused by the technology when using it for language learning. Their result highlighted the additional challenge of using technology for language learning. In Bousley’s (2018) survey of 178 students studying French, German, and Spanish, students showed a mixed attitude towards hybrid language classes, with 48.3% indicating possible interest and 21.3% indicating “no interest” and a generally “no interest” (56.7%) towards fully online classes. Overall, students, depending on their background and the target language, showed varied preparedness for online learning (Winke et al., 2010).

2.2. Student Readiness as an Emerging Topic in Language Teaching After 2020

Before 2020, concerns for student readiness, together with other logistic, pedagogical, and curricular issues, constituted barriers in online language teaching (Goertler, 2019). The perpetuated hesitation slowed the adoption of the online modality in world language teaching. It was not until 2020 to 2021 that the field witnessed the massive and widespread implementations of online language teaching as a crisis response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Over subsequent semesters, what began as an unplanned emergency shift matured with sustained adaptation, evolving into a form that approximates regular online teaching. This period prompted further investigations into student readiness. Some studies, though not investigating it as an integrated construct, explored students’ perceptions and self-reported habits of online learning. For instance, Kim (2022) discussed how Japanese EFL students increased learner autonomy in later stages of remote or online learning. In Yashenkova’s (2022) survey of Ukrainian students, major hurdles were reported on students’ lack of time management and self-organization skills. In Morris et al.’s (2024) study, conducted in Spring 2021 at a mid-sized U.S. university, 122 language learning undergraduate students reported their perceptions of different teaching modalities’ effectiveness, and one conclusion was that the online modality impacts students’ learning habits and that students needed time to develop time management strategies for digital online learning.

Few studies specifically investigated the concept of “student readiness.” Cho (2021) surveyed Korean college students for their perceptions of EFL learning in remote classes at the end of the first and second remote teaching semesters as two data collection points. Compared to survey results at the end of the first semester, second-semester students reported themselves to be more comfortable with remote language classes, suggesting improved readiness through adaptation. Zou et al. (2021) surveyed 2310 students taking and 149 teachers teaching EFL remote courses in China after 2020, focusing on teachers’ technology acceptance and students’ self-rated online learning readiness. Among the five dimensions measured, the students had the lowest readiness in “self-directed learning” and “learner control” (e.g., time management) dimensions, where they showed moderate readiness for the other dimensions, including “computer/internet self-efficacy”, “motivation,” and “online communication self-efficacy.” Despite reporting some challenging areas with technical issues and needed adjustments for online learning, the majority of the student respondents indicated willingness to take EFL courses in the fully online or hybrid modality in the future. Jiang et al. (2024) focused on how demographic factors, learner attitude and environmental support affected student readiness. They surveyed 6364 students taking online EFL classes in China and considered student readiness in several different aspects, including students’ technology competence (which they termed “online learning self-efficacy”), online learning control, learning preferences, communication self-efficacy, and carrying out previews for the flipped classroom design. In their study, students self-reported high levels of readiness (above 4 out of 7) in all these areas, but significant variations across demographic background were found. These studies offered preliminary indications of students’ adaptation in autonomous learning, self-discipline, and time management skills, but findings were inconsistent.

2.3. Teacher Perceptions of Student Readiness

The body of research on the interactive relationship between student readiness and language teachers’ perceptions remains small. Jelińska and Paradowski’s (2021) article on general (instead of language) online learning was one of the few that directly addressed teachers’ perceptions of students’ readiness. The researchers surveyed 1944 teachers in different contexts (from universities to primary schools) across the globe, with most in European or North American countries. They found that teachers’ perceptions of remote teaching effectiveness were a significant predictor of their perceptions of students’ coping: teachers who found their remote instruction to be less efficient than face-to-face classes tended to believe that students were not coping well. More recently, Rüschoff (2024) reported a project conducted under the Council of Europe’s European Center for Modern Languages, drawing findings from a combination of a teacher survey in 2021 (n = 1735) and a secondary school student survey (n ≈ 1300) in 2022. More than half of the teachers believed that students had “become more autonomous during the period of remote learning” and that students appreciated the fact that they had to take responsibility for their work (p. 106). In other words, there was a shared perception of educational growth for both teachers and students. While Rüschoff’s (2024) study was situated in the secondary school context, the strong alignment between teacher-assessed and students’ self-reported readiness was a noteworthy result with more general potential applicability, as it empirically validated the significance of teachers’ perspectives in investigations of student readiness.

2.4. Perceived Student Readiness in Teachers’ Technology Acceptance

One area particularly warranting more attention is student readiness in relation to teachers’ other attitudinal or belief factors in the technology acceptance model (TAM) (Davis, 1989). TAM is interested in variables contributing to one’s willingness, intention, and actual use of technologies in the future. Among the key constructs in TAM, perceived usefulness or value of technology and one’s self-efficacy or self-confidence are two well-attested constructs that are strong predictors of one’s intention to adopt technology in the future (Granić & Marangunić, 2019; Sun & Mei, 2020). While these constructs have general definitions in TAM, in the context of online teaching, perceived values can be understood as teachers’ beliefs of the extent to which online teaching affects students’ learning outcome (Gasaymeh, 2009), whereas teachers’ self-confidence refers to teachers’ beliefs in how their technological and pedagogical knowledge affects students’ online learning success (Corry & Stella, 2018; Lin & Zheng, 2015).

Despite the commonality of using TAM frameworks in digital learning and recent studies arguing for the framework’s significance in future online language research (Huang & Zhang, 2025), its connection to student readiness in online language learning has only recently drawn scholars’ attention. Zou et al. (2021) considered student readiness to be “closely related to the concept of technology acceptance” (p. 3) but did not explicitly explore the relationships between various factors of technology acceptance. Jin et al. (2021) used a structural path analysis and found that language teachers’ perceptions of students’ readiness upon rapid shift to remote language teaching in early 2020 positively contributed to teachers’ beliefs in online teaching’s value and confidence in online teaching, which, in turn, were positive predictors for teachers’ intention to adopt online teaching in post-pandemic times. Further, Xu et al. (2021), exploring U.S.-based Chinese language teachers’ experience and practice of teaching Chinese characters in the initial stage of emergency remote teaching, found that teachers’ perception of student readiness, in addition to their perception of online teaching’s values and their online tool use in character teaching, were unique contributors to teachers’ intention to adopt more online tools for Chinese character teaching in the future. These studies yielded initial evidence for the interplay between teacher and student factors in TAM in online language teaching and pointed to the potential significance of including perceived student readiness as a key factor in future studies of technology integration, especially in teachers’ intentions for future online language teaching.

2.5. Current Study and Research Questions

Teachers’ perceptions about how well their students are managing online learning can deeply affect their teaching effectiveness, potentially creating a “self-fulfilling prophecy” (Jelińska & Paradowski, 2021, p. 9). Educators and stakeholders need to understand how students’ readiness and teachers’ perceptions relate to each other and how these factors, after sustained periods of online teaching trials, may evolve to shape teachers’ attitude towards future digital teaching. However, the current literature on student readiness exhibits several significant gaps.

First, large-scale, nationwide studies on student readiness are astonishingly rare, considering the unique opportunity for wide data collection offered by online language teaching during 2020–2021. The existing body of work is fragmented: some studies were situated in specific Asian or European contexts (e.g., Jiang et al., 2024; Rüschoff, 2024) while others varied widely in scope: Jelińska and Paradowski (2021) analyzed a broad international cohort from 91 countries across K–16 education, whereas Morris et al. (2024) confined their survey to students from a single U.S. public university. To our knowledge, no large-scale study has focused specifically on the online learning readiness of language students in the United States.

Second, research that systematically incorporates the teacher’s perspective on student readiness remains scarce. This gap is critical, given the fundamentally interactive nature of the language classroom, whether virtual or physical. Understanding teacher perceptions is essential to gaining a complete picture of student readiness dynamics.

Finally, few studies have focused on teachers’ or students’ attitudinal changes toward the future of online language teaching. Given the historical reluctance to adopt the online modality in the language teaching field and the quickly evolving technology-enhanced educational practice today, it is critical to study teachers’ assessment of student readiness in a time of technology-adoption shifts and investigate changes in teachers’ own willingness. Tracking these developments builds a contextualized record of technology adoption in language education and is key to understanding the evolving dynamics in the field’s ongoing digital transformation.

The present research addresses these gaps and investigates U.S. language teachers’ perceptions of college-level students’ online readiness and the relationship between student readiness and teachers’ attitudinal changes towards online teaching. The following research questions (RQs) are addressed.

RQ1: How do language teachers perceive students’ readiness for online learning?

RQ2: How does teachers’ perception of students’ readiness correlate with teachers’ perceived values of online language teaching and their self-confidence in online teaching?

RQ3: How does teachers’ perception of students’ readiness in online learning, along with their perceptions of online teaching’s value and their self-confidence, contribute to their evolving willingness to teach online or hybrid language courses in the future?

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants

The study was part of a bigger project on online language teaching in 2021–2022. A sequential explanatory mixed-method approach was used. As a first step to solicit quantitative data, an online Qualtrics survey primarily containing Likert-scale questions was distributed via language teaching professionals’ listservs and social media platforms. From September to November 2021, 309 valid responses were received. As shown in Table 1, the respondents represented a diverse group of teachers teaching different world languages. They had experience teaching different modalities of online courses, with many having experience teaching in multiple online modalities.

Table 1.

Demographic Background of the Survey Respondents (n = 309).

From December 2021 to January 2022, follow-up online interviews via Zoom were conducted with 21 of the survey respondents. The interviewees were purposefully selected to reflect our participant pool’s diverse background. Those included teachers of different languages: Spanish (5), French (3), Mandarin Chinese (3), Japanese (4), German (2), Russian (2), Portuguese (1), and Italian (1) and different ranks: tenured professors (4), full-time non-tenure-line instructors or lecturers (13), and part-time instructors (3). All interviewees have taught online synchronous classes since the pandemic, 11 have taught online hybrid courses (a combination of synchronous and asynchronous), and 2 have taught asynchronous classes.

3.2. Instrument and Procedure

The quantitative data came from the questionnaire, which contained five sections surveying teachers’ (a) perceived value of online language teaching (value), (b) self-confidence in online language teaching (teacher confidence), (c) technological pedagogical and content knowledge, (d) perceived student readiness for online language teaching, and (e) attitudinal changes towards online language teaching in the future. Only data from the teachers’ post-pandemic perceptions in sections (a) and (b), their responses to all nine items in (d), and two items on changed willingness towards future online and hybrid teaching in (e) were used in this study. The complete questionnaire can be found at the IRIS database. (See “Data Availability Statement.”)

Sections (a), (b), and (d) contained 5-point Likert scale questions in which participants were asked to rate statements regarding their beliefs and perceptions from “strongly disagree” (point 1) to “strongly agree” (point 5). For the scale assessing student readiness, i.e., Section (d), survey items include: (1) My students have the technologies needed for online language courses. (2) My students are self-disciplined with online learning. (3) My students can learn from a variety of formats (lectures, videos, podcasts, online discussion/conferencing). (4) My students meet multiple deadlines for course activities. (5) My students know how to use asynchronous technologies (discussion boards, email, etc.) for information and communication. (6) My students know how to use synchronous technologies (e.g., Zoom, Microsoft Teams, etc.) to communicate. (7) My students ask me for help via email, discussion board, or chat. (8) My students ask classmates for support (e.g., accessing the course, clarification on a topic). (9) My students know how to navigate the course learning management system (e.g., Moodle, Canvas, Blackboard, etc.). Validity and reliability of the perceived value, teacher confidence, and perceived student readiness constructs were addressed in the following ways: The scales for perceived value and teacher confidence were adopted from Jin et al. (2021), where their construct validity was previously established through factor analysis. For the perceived student readiness scale, we modified items from the established scale in Jin et al. (2021), using additional concepts mentioned in Martin et al. (2020) to guide item development, thus ensuring content validity. For the current sample, all three composite scales demonstrated solid internal consistency reliability (as reported in Section 4).

Participants’ responses towards the following statements of changed willingness in the (e) section were used: “1. Compared to pre-pandemic times, I am more willing to teach 100% online language courses; 2. Compared to pre-pandemic times, I am more willing to teach hybrid/blended language courses.”

Qualitative data were drawn from the interviews. The interviews were semi-structured with open-ended questions that prompted interviewees to provide reflections. Each interview lasted 30 to 50 min. We focused on interviewees’ answers to the following: Do you think your students have adapted well to online language learning in this past academic year? Did you see their competence in online language learning change over time? If yes, in what way? If not, what do you think caused the lack of growth in competence? We also examined interviewees’ responses to questions regarding their perceived values of online teaching, their confidence, practice, and attitudinal changes in online teaching in the future, if interviewees made references to student readiness in their responses.

3.3. Data Analysis

This study is grounded in a pragmatic worldview, which prioritizes the research problem and justifies the use of mixed methods to obtain a more complete understanding (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2018). There were two phases of data analysis, corresponding to the two-step study design. The initial quantitative phase identifies broad statistical patterns, while the subsequent qualitative phase draws on experience shared by interview participants to build a deeper understanding of the results.

In phase one, quantitative analysis was conducted on participants’ survey responses. All quantitative analyses were performed using SPSS version 29.0.2.0. For RQ1, we used participants’ rating responses to the Likert-scale questions in the (d) student readiness section. A Principal Component Analysis (PCA) with Varimax rotation was conducted on the nine items to identify key components of student readiness. This technique was selected for its suitability in exploring the component structure of the data for descriptive purposes (e.g., Zimmerman & Kulikowich, 2016). The Kaiser criterion (eigenvalues > 1) was used to determine the number of components to extract. To address RQ2, Pearson’s correlations were computed to examine the relationships between three key constructs: perceived student readiness, teachers’ perceived value of online teaching, and teaching self-confidence. Each construct was measured as a composite score derived from the mean of its respective survey items: 9 items for student readiness, 10 items for perceived values of online teaching, and 8 items for teacher confidence. The development of these items is detailed in Section 3.2 “Instrument and Procedure.” To explore RQ3, participants’ responses to the Likert-scale questions were transformed into three categories (“disagree,” “neutral,” and “agree”) to meet statistical test assumptions. (See Section 4.3 for the rationales of data transformation.) Two regression analyses were conducted to examine how the three independent variables, namely perceived student readiness, perceived value of online teaching, and teacher confidence, contribute to teachers’ increased willingness for future teaching modes. The dependent variables were increased willingness to teach 100% online and increased willingness to teach hybrid in the future, each measured by a single Likert-scale item. For willingness to teach online, a multinomial regression was used because the proportional odds assumption was violated (Test of Parallel Lines: χ2(3) = 14.617, p = 0.002). For willingness to teach hybrid, an ordinal regression was used, as all its assumptions were met.

Phase two consisted of a qualitative analysis of 21 interview transcripts (coded IR01–21). Following a typological approach (Hatch, 2002), the analysis was structured by the research questions, focusing on themes related to: (1) the specific attributes of student readiness, (2) the interrelationships between perceived student readiness, teacher confidence, and perceived value, and (3) the role of student readiness in shaping teachers’ changed willingness for future online or hybrid teaching. Two researchers independently coded the data, identifying patterns and illustrative examples for these pre-specified typologies. Through iterative discussion, they reached a consensus on the thematic structure, which was then verified by a third researcher to ensure reliability.

4. Results

4.1. Language Teachers’ Perceptions of Students’ Online Learning Readiness

Construct reliability was assessed through internal consistency. All three scales demonstrated good to excellent reliability, with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of 0.79 for perceived student readiness, 0.90 for perceived value, and 0.89 for teacher confidence. The PCA yielded a three-component solution, which collectively explained 61.3% of the total variance. All items had component loadings above 0.53. The specific loadings for each item, as well as the Eigenvalue, % of variance, composite means, and standard deviations of each component, are presented in Table 2. The clear component structure provides evidence for the construct validity of the refined student readiness scale.

Table 2.

Principal Component Analysis for perceived student readiness items.

Component 1, access to and abilities to use technology, consists of five items (items 1, 3, 5, 6, 9). This component reflects students’ access to online technologies and their abilities to navigate online platforms and use synchronous and asynchronous online tools. Component 2, self-responsibility in online learning, includes items 2 and 4, reflecting students’ self-discipline and their accountability in online learning. Component 3, support for online learning, includes items 7 and 8 and captures the students’ use of instructor and peer support. The means and standard deviations for these three student readiness aspects were reported in Table 2.

The results showed that teachers believed that students generally had the technological skills to navigate, used various platforms, used synchronous and asynchronous technology, and had access to technology. Teachers also felt confident that students reached out to instructors and peers for help. However, teachers had some reservations regarding students’ self-responsibility in online learning.

Qualitative analysis led to the identification of two main themes: Quick adaptation through learning curves and concerns for self-responsibility. Interviewees generally had positive attitudes towards student readiness, especially in students’ abilities to adapt, which convinced many teachers that online language learning “is not only possible, it’s doable” (IR08). “Learning curve,” described as “huge” or “steep,” was a recurring key term mentioned by at least 10 interviewees. Many considered their students to have “adapt[ed] fairly quickly” (IR06) or “really fast” (IR20), but some felt it was “a slow evolution” (IR19). According to IR07, students became “more organized,” participated “more actively” in discussions, and were no longer “embarrassed” in virtual classrooms. The learning curve encompassed two main aspects: technology readiness and self-responsibility. Perceptions of initial tech readiness varied, with some interviewees referring to students as “digital natives” and others labeling the notion as “absolutely false” (IR14). Most agreed that technical issues soon “faded away” (IR09; IR18). Regarding students’ self-responsibility, opinions were split. Some believed that students gained more self-control and autonomy in adaptations to digital learning (IR19), while others believed self-responsibility was an intrinsic “personal characteristic” that resists impact from learning environment (IR08; IR10).

The recurring theme of self-responsibility challenge aligns with the quantitative results on the component and consists of three subthemes: First, multiple teachers noted signs of distractions in the online environment, such as students attending classes “from the backseat of a friend’s car.” Such behaviors were thought to “decrease the amount of trust and [other students’] willingness to participate in the class” (IR08). Second, academic misconduct in various forms of cheating was a “very frustrating” frequent issue, ranging from students sharing answers to false claims of online participation (IR06; IR14). Finally, some interviewees felt that the online environment may lead to “too much leniency” with no personal “accountability” (IR05).

Although some teachers felt increased distraction was inherent to digital learning (e.g., IR03), many actively developed strategies to promote responsible conduct and accountability. Some teachers implemented strict rules, such as requiring students to show cellphones on camera, but they noted these measures often risked creating distrust. For instance, IR09 observed that students “really hate lockdown browser” because it “created a sense of pressure” and made them “feel that teachers don’t trust them at all.” Many interviewees conceded that, given the lack of appropriate tools to prevent cheating, they simply had to “trust the student” (IR07; 09; 10; 20). Several interviewees developed alternative pedagogy, deliberately “encouraging [students] to look for online resources,” to share their use of online apps, and to use self-study reports by apps in lieu of homework (IR07; 08; 17). They also changed traditional tests to “open-book or take-home exams” and “performance-based projects” (e.g., IR10). These approaches utilized online resources to shift more responsibilities onto the students, encouraging their self-direction. To help students with accountability, such as meeting deadlines, several interviewees reported finding success with clear structures: “keeping expectations and due dates clear”; keeping everything “organized” and “predictable”; “minimizing the time [students] spend to find things and links” (IR03; 09; 10; 21). These teachers felt a transparent system helped students meet expectations with “no difficulty.” Several teachers felt that they succeeded in instilling a sense of responsibility through the adaptation. IR19 acknowledged that her students, through adjustment, were “finally [being] responsible for themselves in the class.” IR17 felt that her students became “more collaborative” and “can rely on each other more” while they can also “do things independently [and] gauge their own level of knowledge.”

4.2. Relationship Between “Perceived Student Readiness,” “Teacher Values,” and “Teacher Confidence”

The assumptions for Pearson’s correlation were assessed through visual inspection of bivariate scatterplots. There were no significant outliers or heteroscedasticity. Plus, given the robust sample size (N = 309), the analysis is resilient to minor deviations from normality. As Table 3 shows, there were significant correlations between these three variables (ps < 0.001). Perceived student’s readiness was strongly correlated with teacher’s self-confidence (r = 0.52). It was also moderately correlated with instructors’ “perceived values of online teaching” (r = 0.38). The correlation between the two traditional technology acceptance variables, value and confidence, was also significant (r = 0.58). Teachers who perceived their students to be more ready for online learning had higher self-confidence in online teaching; teachers who gave high ratings to their students’ online learning readiness also had higher ratings for the value of online language teaching. In other words, student readiness interacted with other variables of teachers’ technology acceptance.

Table 3.

Correlations between different technology acceptance variables.

The qualitative data help explain the correlations between the three variables: The shared “learning curve” helped teachers build connections with students, which facilitated both teaching and learning preparedness and outcomes, in turn contributing to improved self-efficacy and perceived values of online teaching.

First, due to the shared learning curve, interviewees reported having a “very similar experience” as the students, and they became “understanding” and “compassionate” towards each other when adapting (IR05; 13; 14; 19). IR03 likened the shift to the online modality to “asking students to jump off the cliff with you” without certainty, emphasizing the role of initial positive experiences in building mutual confidence. IR17 compared teachers to drivers and students to passengers, highlighting the impact of teachers’ confidence on students’ comfort and engagement. These analogies illustrate how students’ online readiness or performance corresponds directly to teachers’ efficacy. A related subtheme was “community building” and its contribution to students’ confidence and teaching effectiveness (IR 02; 05). Teachers found that acknowledging their limitations and mistakes was highly effective in encouraging student motivation and interaction. As IR14 stressed, teachers must be “willing to fail” and laugh at themselves. Other interviewees agreed that this kind of candor built trust and empathy, making students more “comfortable” and “confident,” which in turn facilitated mutual growth (IR05; 09; 19).

Teachers’ perceptions of online teaching’s value often depended on students’ achievements. IR02, a German teacher with over 20 years of experience, felt “very good” about his and his students’ progress after a year of online teaching. Teachers noted that when students recognized the effectiveness of online learning, it became easier for them to embrace the new modality (IR09). They observed that student readiness and commitment directly influenced learning outcomes, shaping teachers’ views on online teaching’s value. A Spanish teacher (IR16) noted that engaged students could learn nearly as much as in-person classes, while a Russian teacher (IR03) linked her growing confidence with technology to her students’ progress, which matched her students’ typical learning outcome in pre-pandemic times.

On the other hand, some teachers felt the online environment posed challenges to learning, citing difficulties in building natural rapport with the students (IR19; 21). A Spanish and Portuguese teacher (IR13) at a public institution linked students’ lack of readiness to his negative view of online learning. Many students at his institution traditionally juggled full-time classes with work or caregiving responsibilities, and the institution has a low fourth-year graduation rate. IR13 observed heightened anxiety among students due to the online environment, leading him to conclude that it “is not the right learning environment.” To him, the experience of teaching online reinforced his belief in the importance of face-to-face interaction for meaningful human connection.

These testimonies show that while teachers’ perceptions of online teaching’s value varied, they were closely tied to perceived students’ readiness and the outcome of online interaction.

4.3. Perceived Student Readiness and Teachers’ Attitudinal Changes for Online Teaching

To explore the quantitative aspect of this question, participants’ responses to questions of “increased willingness” towards online and hybrid teaching were recategorized into an ordinal variable with a 3-point scale. This was because the original 5-point responses were unevenly distributed across the five groups. For instance, there were few 1-point responses, which led to insufficient observations in that category for statistical analysis. Thus, responses of 1 and 2 were coded as the first level of the dependent variable, responses of 3 were coded as the second level, and responses of 4 and 5 were coded as the third level of the variable “increased willingness.” The frequencies of each level for the attitudinal change variables after coding are presented below, in Table 4.

Table 4.

Tabulation of survey respondents’ responses towards “increased willingness.”.

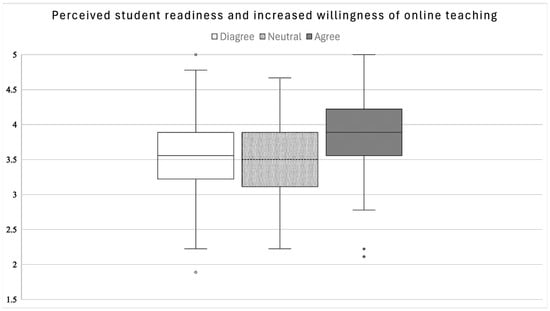

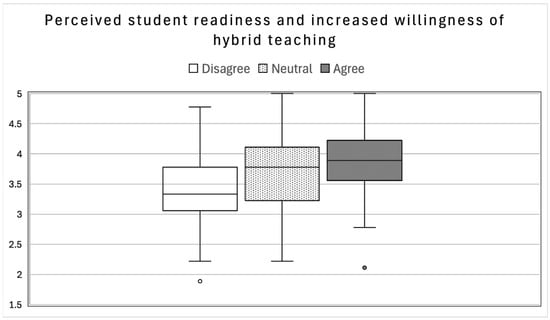

The boxplots (Figure 1 and Figure 2) below visually show the correlation of perceived student readiness with teachers’ attitudinal changes: For teachers’ attitudinal change towards 100% online teaching, those who agreed with the statement of “increased willingness” gave higher ratings to student readiness, compared to those who were neutral or disagreed with the statement. For teachers’ attitudinal changes towards hybrid teaching, those who agreed with the “increased willingness” statement rated student readiness higher than those who responded “neutral,” which in turn rated student readiness higher than teachers who disagreed with the statement.

Figure 1.

Relationship between teachers’ perception of student readiness and their increased willingness to teach 100% online language courses in the future.

Figure 2.

Relationship between teachers’ perception of student readiness and their increased willingness to teach hybrid language courses in the future.

We first examined the effects of the three independent variables on teachers’ increased willingness towards 100% online teaching. Stepwise multinomial regression was used, with value and confidence entered as the independent variable in the first step and student readiness as the third independent variables entered in the second step. The model was a good fit (χ2 = 87.713, p < 0.0001). The likelihood ratio test showed that the addition of student readiness in the second step significantly improved the model (G2 = 7.516, p < 0.023).

For the “disagree” response relative to the “agree” response to “increasing willingness,” the effect of student readiness did not reach significance (p = 0.183), given other predictors in the model. For the “neutral” response relative to the “agree” response, student readiness had a unique positive effect on increased willingness (p = 0.007). Specifically, the odds ratio was 0.435. That is, when teachers’ perceived values of online teaching and their self-confidence are held constant, if a participant increases their response in student readiness by one unit on the 5-point scale, the chance of them choosing an “agreement” rather than “neutral” response to the “increased willingness” statement increases by a factor of 0.435.

We then investigate the effects of the three independent variables on teachers’ increased willingness towards hybrid teaching. The ordinal regression result is presented in the table below. The model was statistically significant, χ2(3) = 53.471, p < 0.001. Nagelkerke R2 = 0.181. Results are presented in Table 5 and confirm the unique contribution of student readiness to the dependent variable. Specifically, when the other variables (i.e., perceived value and teachers’ self-confidence) in the model are held constant, an increase of 1 unit (in the 5-point Likert scale) in student readiness is associated with an increase in the odds of having a positive attitudinal change in hybrid teaching, with an odds ratio of 1.786 (95% CI, 1.156 to 2.76), Wald χ2(1) = 6.828, p < 0.009).

Table 5.

Results of Ordinal Regression Analysis.

The above results indicate that teachers’ perceptions of student readiness played an important role in both their attitudinal changes towards both hybrid teaching and 100% online teaching in the future. Perceived student readiness was a significant predictor of teachers’ attitudinal changes in hybrid teaching. Positive perceptions of student readiness also improved teachers’ attitudes from “neutral” to “increased willingness” responses for 100% online teaching.

Qualitative data highlight the key role of student readiness in shaping teachers’ willingness for future modalities of teaching. IR02, a German instructor, credited disciplined students and resourceful online tools for his positive experience, noting that engaging native speakers via Zoom was highly effective and referred to his long-term plans to use more web materials in the future. Similarly, after observing how some students thrived online, they became more open to integrating online components in the future, even for conversation courses that traditionally rely on in-person communication. IR17, a French professor teaching both language and language pedagogy classes, admitted that her response to online language teaching would be “absolutely not” 30 years ago, but she was “swayed” by both her recent research and her personal experience of witnessing students “get better at it.” She emphasized that the success of online language teaching hinges directly on student readiness and effective pedagogy, and referred to specific strategies such as a flipped classroom design to enhance student readiness. She further recognized the benefits of online teaching to diverse students and learning preferences.

5. Discussion

The present study revealed three components of perceived student readiness, which largely mirror the construct of student readiness in the general online education domain: First, the component of technology access and abilities aligns with the concept of student “technical competence” in Martin et al. (2020). Despite earlier studies’ consideration of “access” and “competency in use” as two distinct factors (e.g., Zou et al., 2021), the high correlation observed with “access” and “comfort” or “ability to use” suggests they can be coherently considered as one dimension. Second, the component of using support for online learning reflects students’ “online communication competence” (Jiang et al., 2024; Martin et al., 2020; Zou et al., 2021). Finally, we identified a core component termed “self-responsibility.” While prior research has highlighted related concepts like “self-direction” or “learner control” (e.g., Hung et al., 2010) and “time management” (Zimmerman & Kulikowich, 2016), our quantitative and qualitative analyses suggest that a broader construct is necessary to capture students’ self-control, ethical conduct, and accountability. In contrast to strict control, teachers in our study found it more effective to entrust students with responsibilities. They leveraged digital and pedagogical tools to demand a higher degree of student ownership and self-direction, providing a predictable and transparent accountability system to help. This reconceptualization of “self-responsibility” is the context of ongoing educational digitalization: As learning environments increasingly grant students autonomy and powerful tools, they also introduce more distractions and new ethical dilemmas. Students’ self-responsibility, emerging as a core construct in online learning readiness, is a foundational competency in digital learning today (Mukul & Büyüközkan, 2023).

The composite means of these teacher perceived student readiness matched language students’ own ratings in earlier studies: In Zou et al. (2021), EFL students were found to have low “self-directed learning” readiness (3.48/5) and low “learner control (3.47/5) whereas they had relatively high “online communication” and “computer/internet self-efficacy” (around 3.7/5). The consistency between student surveys and teacher perspectives in the current research supports the validity of the identified student readiness component and confirms that teachers and students share similar perceptions of student preparedness and challenges in online language learning.

We found that teachers’ perception of student readiness can be divided in some cases. Qualitative findings suggested institutional factors and student background factors. Institutional factors have been noted in Zou et al.’s (2021) study of college students’ online EFL learning in Wuhan during the pandemic: students at the institutions directly under the Ministry of Education had better readiness than students at institutions under the provincial department of education; they also had better readiness than students at non-governmental institutions. Such disparities directly affect students’ technology access and competence. Regarding student factors, although some interviewees considered student control and discipline as inherent “student attributes” (Martin et al., 2020), many teachers in our study reported having found ways to regulate and nurture student-responsibility through empathy, trust, and adaptive pedagogy. Their strategies helped students to quickly adapt to the “new normal.” Overall, proactive efforts from institutions and teachers are vital to support learners to thrive in changing environments that increasingly demand technological access, competency, and learner autonomy.

The study responded to the call for expanding and extending the factors in TAM research in online language learning (Huang & Zhang, 2025). Compared to earlier research on connections between language students’ self-perceived readiness and their perception of online learning’s values (e.g., Zou et al., 2021), the correlations between key variables in the current study highlight a synergistic relationship between teachers and students. Teacher testimonies emphasized “compassion,” “empathy,” and “mutual” trust as key psychological elements in a shared journey of pedagogical transition. The interplay between teachers’ and students’ efforts in digital adaptation was evident: teachers’ and students’ (self-)evaluations, attitudes, and beliefs shape and reinforce one another; teachers gained confidence from student progress, while observing student struggles often reinforced skepticism about online teaching’s value.

Finally, the predictive relationship between perceived student readiness and language teachers’ increased willingness for online and hybrid teaching is a unique contribution of the current study. From the teachers’ professional development perspective, this indicates a critical need for the future: Teachers should be equipped with more than just technical and language pedagogy skills; they should be trained to diagnose and scaffold student readiness. When teachers feel empowered to foster these fundamental student competencies, their own apprehension of educational changes will be transformed into a willingness to embrace innovation.

6. Conclusions and Limitations

Through national surveys and interviews with U.S.-based tertiary-level language teachers’ perceptions, this study found technology access and competency, students’ self-responsibility, and their use of peer and teacher support to be three key aspects of teacher- perceived student readiness in online language courses. Perceived student readiness correlated with teachers’ self-confidence and their perception of online teaching’s value and is a significant predictor of language teachers’ increasing openness to future online teaching.

Today, language teachers and students’ readiness are subject to quick transformations in the digital world. The challenge of online teaching in 2020–2022 is now followed by uncertainties surrounding the adoption of artificial intelligence technologies in language classrooms. Against the backdrop of this emerging educational paradigm shift, concerns for students’ accountability and responsibility again rise. In language education, teachers need to offer more than discipline-specific expertise but have an increased role as mentors in supporting, motivating, and guiding students, both pedagogically and psychologically. This study found that successful strategies prioritize mutual trust and implement pedagogical modifications to strengthen students’ ownership of their learning. Teachers’ reassuring attitude, confidence, and beliefs can foster an ethical learning culture and positive engagement. Institutions also have a responsibility to support both teachers and students in times of educational transition, ensuring adequate training for teachers and equitable access and responsible use of technology among students.

While this study provides a critical examination of teacher-perceived student readiness during a historical transition that normalized online language teaching, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the absence of students’ self-reported data presents an opportunity for future research. Triangulating teacher observations with student-facing surveys and interviews will reveal influences of student motivation, habits, and beliefs. Further, the potential impact of institutional factors, though indicated in our qualitative data, remains to be systematically explored. The constructs of student readiness and teachers’ technology acceptance are dynamic factors that continue to co-evolve within our changing educational landscape. The present results have established a baseline detailing students’ digital language learning preparedness from a period of intense technology adoption and pedagogical transition, providing a needed benchmark for future longitudinal research to track how readiness and acceptance evolve in an educational future characterized by an abundance of digital tools and an imperative of shared accountability and student agency.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, all authors; methodology, all authors; software, Y.X.; validation, L.J.; formal analysis, Y.X. and L.J.; investigation, Y.X. and L.J.; resources, all authors; data curation, all authors; writing—original draft preparation, Y.X.; writing—review and editing, all authors; visualization, Y.X.; supervision, Y.X.; project administration, Y.X.; funding acquisition, L.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning grant from the DePaul University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of University of Pittsburgh (STUDY21090157, approved on 13 October 2021) and DePaul University (Protocol #1 IRB-2021-467, approved on 13 October 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was waived because no identifying information (except for the temporary storage of participants’ emails for the purpose of interviewee contact, which were permanently deleted after interviews) is kept, and participants were fully informed of the research’s nature on the online survey before they proceeded to fill out the surveys.

Data Availability Statement

The data-collecting survey instrument presented in the study is openly available through IRIS (https://www.iris-database.org/details/QAF6b-PuE13, accessed on 15 October 2023). Because the study was part of a bigger project with ongoing analysis, restrictions apply to datasets. Some specific data used in the study may be made available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank all language teachers who participated in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TAM | Technology Acceptance Model |

| RQ | Research Question(s) |

| IR | Interviewee |

References

- Bousley, C. (2018). Did we forget someone else? Foreign language students’ computer access and literacy for CALL [Master’s thesis, Michigan State University]. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, H. (2021). Students’ perceptions of emergency online language education during COVID-19 pandemic: A case study. Multimedia-Assisted Language Learning, 24(2), 10–33. [Google Scholar]

- Corry, M., & Stella, J. (2018). Teacher self-efficacy in online education: A review of the literature. Research in Learning Technology, 26, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2018). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasaymeh, A. M. (2009). A study of faculty attitudes toward internet-based distance education: A survey of two Jordanian public universities [Doctoral dissertation, Ohio University]. [Google Scholar]

- Goertler, S. (2019). Normalizing online learning: Adapting to a changing world of language teaching. In L. Ducate, & N. Arnold (Eds.), From theory and research to new directions in language teaching (pp. 51–92). Equinox. [Google Scholar]

- Goertler, S., Bollen, M., & Gaff, J., Jr. (2012). Students’ readiness for and attitudes toward hybrid FL instruction. Calico Journal, 29(2), 297–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granić, A., & Marangunić, N. (2019). Technology acceptance model in educational context: A systematic literature review. British Journal of Educational Technology, 50(5), 2572–2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatch, J. A. (2002). Doing qualitative research in education settings. State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, F., & Zhang, H. (2025). Explaining the penetrating role of technology in online foreign language learning achievement. Foreign Language Annals, 58(1), 10–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, M. L., Chou, C., Chen, C. H., & Own, Z. Y. (2010). Learner readiness for online learning: Scale development and student perceptions. Computers & Education, 55(3), 1080–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelińska, M., & Paradowski, M. B. (2021). Teachers’ perception of student coping with emergency remote instruction during the COVID-19 pandemic: The relative impact of educator demographics and professional adaptation and adjustment. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 648443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, L., Meng, H., & Zhou, N. (2024). English learners’ readiness for online flipped learning: Interrelationships with motivation and engagement, attitude, and support. Language Teaching Research, 28(5), 2026–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L., Xu, Y., & Deifell, E. (2024). Remote language teaching and changes in college-level world language educators’ knowledge and attitudes toward online language teaching. In S. Goertler, & J. Gleason (Eds.), Technology-mediated crisis response in language studies (pp. 16–48). Equinox. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, L., Xu, Y., Deifell, E., & Angus, K. (2021). Emergency remote language teaching and U.S.-based college-level world language educators’ intentions to adopt online teaching in postpandemic times. Modern Language Journal, 105(2), 412–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. (2022). Implications of a sudden shift online: The experiences of English education students’ studying online for the first-time during COVID-19 pandemic in Japan. In Emergency remote teaching and beyond: Voices from world language teachers and researchers (pp. 193–213). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- LaMance, R. A. (2012). Say hello to hybrid: Investigating student and instructor perceptions of the first hybrid language courses at UT [Master’s thesis, University of Tennessee]. Available online: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/1177 (accessed on 10 August 2024).

- Lin, C.-H., & Zheng, B. (2015). Teaching practices and teacher perceptions in online world language courses. Journal of Online Learning Research, 1(3), 275–304. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, F., Stamper, B., & Flowers, C. (2020). Examining student perception of readiness for online learning: Importance and confidence. Online Learning, 24(2), 38–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, K., Robarge, M., & Robles-Garcia, P. (2024). Confronting crisis with craft: Students’ perceptions of language teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic. In S. Goertler, & J. Gleason (Eds.), Technology-mediated response in language studies (pp. 229–251). Equinox. [Google Scholar]

- Mukul, E., & Büyüközkan, G. (2023). Digital transformation in education: A systematic review of education 4.0. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 194, 122664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rüschoff, B. (2024). The future of language education in the light of COVID: A European survey project on lessons learned and ways forward. In S. Goertler, & J. Gleason (Eds.), Technology-mediated response in language studies (pp. 86–113). Equinox. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, P. P., & Mei, B. (2020). Modeling preservice Chinese-as-a-second/foreign-language teachers’ adoption of educational technology: A technology acceptance perspective. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 35(4), 816–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- University of Arkansas Online. (n.d.). Available online: https://online.uark.edu/students/readiness-quiz.php (accessed on 7 July 2024).

- Ware, L. L. (2018). A Descriptive study of readiness skills assessment instruments, support services, and retention of online community college students [Doctoral dissertation, Northcentral University]. [Google Scholar]

- Winke, P., & Goertler, S. (2008). Did we forget someone? Students’ computer access and literacy for CALL. CALICO Journal, 25(3), 482–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winke, P., Goertler, S., & Amuzie, G. L. (2010). Commonly taught and less commonly taught language learners: Are they equally prepared for CALL and online language learning? Computer Assisted Language Learning, 23(3), 199–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y., Jin, L., Deifell, E., & Angus, K. (2021). Chinese character instruction online: A technology acceptance perspective in emergency remote teaching. System, 100, 102542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yashenkova, O. (2022). Listening to student voice to improve the quality of emergency remote teaching. In Emergency remote teaching and beyond: Voices from world language teachers and researchers (pp. 507–533). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, T., & Richardson, J. (2015). An exploratory factor analysis and reliability analysis of the student online learning (SOLR) instrument. Online Learning, 19(5), 120–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, W. A., & Kulikowich, J. M. (2016). Online learning self-efficacy in students with and without online learning experience. American Journal of Distance Education, 30(3), 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, C., Li, P., & Jin, L. (2021). Online college English education in Wuhan against the COVID-19 pandemic: Student and teacher readiness, challenges and implications. PLoS ONE, 16(10), e0258137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).