Abstract

The research explores the attitudes of students without disabilities towards the inclusion of students with disabilities in Physical Education classes. It analyses how gender and previous contact with people with disabilities influence these attitudes across four Spanish-speaking cities. The study involved 3732 secondary school students from Spain and Chile. Data was collected using the Students’ Attitudes Towards Integration in Physical Education (CAIPER-R) instrument. The results indicated that girls generally have more positive attitudes towards inclusion than boys. However, previous contact with people with disabilities did not significantly affect the students’ attitudes. There were also differences observed across the cities, with Extremadura showing the highest inclusion scores. This study highlights the importance of gender in shaping attitudes towards inclusion in PE. It suggests that new educational policies are effectively promoting inclusion across culturally similar countries, such as Chile and Spain.

1. Introduction

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development comprises 17 goals (SDGs) that encompass economic, social, and environmental dimensions. Among these, the objective of quality education (SDG 4) is to “ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all” (UNESCO, 2017b). When the topic is expanded upon, in accordance with Ainscow (2020a, 2020b), the inclusion of students with disabilities (SWD) in mainstream educational settings may be addressed through two main targets: (1) the elimination of all discrimination in education and (2) the construction and improvement of inclusive and safe schools. In light of these considerations, school-based Physical Education (PE) emerges as a distinctive setting where all children, regardless of their abilities, can engage in active and dynamic participation together (Qi & Ha, 2012), fostering the development of their domains of learning (psychomotor, affective, and cognitive), and maximizing the benefits of the curriculum (Wilhelmsen & Sørensen, 2017).

Although it is well known that inclusive PE provides meaningful physical activity opportunities both for students with and without disabilities (Pocock & Miyahara, 2018), SWD usually encounter numerous barriers to feel fully included in this context with their peers (Muñoz-Hinrichsen et al., 2024a; Sammon et al., 2020). According to Hutzler’s (2007) extended ecological model, barriers restricting the participation of SWD in physical activities have more to do with physical and social constraints rather than with the individual’s health condition (World Health Organization, 2007). PE is another setting in which these barriers manifest themselves. In some cases, these barriers are environmental and structural in nature (i.e., physical, such as specific equipment shortage or inaccessible constructions), which means that neither students nor teachers are likely to eradicate them on their own in a short-term period (Maher & Haegele, 2024). Nevertheless, one of the most significant barriers SWD encounter is an unfavorable social environment largely influenced by negative attitudes among peers (Teixeira Fabricio dos Santos et al., 2025; Wang, 2019). Because of these behaviors, SWD usually experience “bad days” in PE, defined as perceiving a lack of belonging to the typical development group, discrimination, or social isolation. Conversely, “good days” in PE, as experienced by these children, are characterized by a sense of belonging, skillful participation, and benefits sharing (Goodwin & Watkinson, 2000; Holland & Haegele, 2021).

Unambiguously, the role of children without disabilities is of great importance in fostering the acceptance of a peer with a disability (Freer, 2023). It is vital to acknowledge that demonstrating positive attitudes towards individuals with disabilities is likely to result in more effective inclusion. Consequently, it becomes essential to investigate the impact of various variables on attitudes towards the inclusion of classmates with disabilities in PE. For example, Reina et al. (2019) suggested that gender, previous contact, and participation in physical activities with children with disabilities partially contributed to the explained variance of “positive attitudes towards SWD”. Specifically, the authors found that girls reported more positive attitudes towards inclusion than boys, as did those who had previous contact or participation in activities with people with disabilities. However, the extant literature on this subject is controversial, and further research is required to understand the attitudes of younger and older students towards disability (Block, 2016; McKay et al., 2019).

In response to mounting international advocacy for the inclusion of individuals in all aspects of society, several countries worldwide have modified their educational policies to incorporate models that facilitate the inclusion of all students in mainstream educational settings. Sport is highlighted as an outstanding tool in this respect. For instance, at the Sixth International Conference of Ministers and Senior Officials responsible for Physical Education and Sport (MINEPS VI), UNESCO asserted that “sport policies at national and international levels must be inclusive of contributing to the reduction of inequalities, and therefore inclusive access for all to physical education, physical activity, and sport must be a basic component of any national or international sport policy” (UNESCO, 2017a). As noted by Bertills and Björk (2024), the promotion of programs and activities in the field of PE that are conducive to the inclusion of young people with disabilities is of paramount importance.

One such activity is the Inclusive Sport at School (ISS) program (Pérez-Tejero et al., 2013), which has been developed during successive academic years in different cities, including in Spain and Chile (Grassi-Roig, 2024; Muñoz-Hinrichsen et al., 2024b). The ISS program has been developed as a multiday initiative—developed over an academic year—to provide a sustained experience for its participants. In agreement with the principles of Paralympic School Day (McKay et al., 2015), practical activities are carried out in which students interact with Paralympic athletes and play sports commonly practiced by people with disabilities, always considering an inclusive format (Ocete et al., 2015).

1.1. Educational Legislation on Inclusion: The Cases of Chile and Spain

Chilean inclusive education policies, aligned with SDG 4, are guided by the enactment of the School Inclusion Law (Ministerio de Educación de la República de Chile, 2015)—promoting free education, non-discrimination, and the elimination of selection—and by three decrees on inclusive assessment, curricular adaptations under Universal Design for Learning, and providing the framework for inclusion support programs. In Spain, the Organic Law 3/2020 of December 29, which amends the Organic Law 2/2006 of May 3 on Education (Ministerio de Educación y Formación Profesional, 2020), emphasizes two main goals: avoiding segregation of students with special needs and strengthening the system’s inclusive capacity, requiring administrations to provide resources, support, and schooling decisions tailored to each student.

1.2. Justification of the Research and Objectives

In the context of the growing global emphasis on educational inclusion, particularly within PE classrooms, it becomes imperative to address the existing lacuna by exploring the prevailing attitudes of young individuals towards the inclusion of their peers with disabilities. In addition, it is crucial to consider the sociodemographic context of these students to accurately ascertain the findings of the research.

To date, research has not examined students’ attitudes towards inclusion in PE across different Spanish-speaking regions that share comparable educational frameworks, such as Chile and Spain. Consequently, to the best of our knowledge, this study constitutes a novel contribution that addresses this gap by providing the first cross-regional analysis of the perspectives of students without disabilities on the inclusion of children and adolescents with disabilities in four Spanish-speaking cities—three in Spain and one in Chile. Furthermore, the analysis encompasses key sociodemographic variables emphasized in the extant literature, including gender and previous contact with individuals with disabilities, thereby offering a more comprehensive understanding of the factors that shape these attitudes. We hypothesize that these factors and variables may influence participants’ attitudes.

Based on the findings of previous studies included in our research, we hypothesized that (a) Spanish students would show better attitudes than Chilean children, (b) female students would exhibit more positive attitudes towards inclusion than their male counterparts, and (c) students who reported previous contact with persons with disabilities outside of the academic environment would have more positive attitudes than those who have not had contact with persons with disabilities.

2. Materials and Methods

For the development of the research process, the work will be organized under two main objectives: (1) the first is to validate the CAIPER-R instrument, to be able to use it in the study group, and (2) to know the attitudes of students without disabilities towards the inclusion of children and adolescents with disabilities in PE in Spain and Chile.

2.1. Participants

A sample of 3732 students (n = 1905; 51.05% females and n = 1827; 48.95% males) from secondary schools participated voluntarily in this study. All participants were drafted from Spanish schools in Extremadura, Ibiza, and Madrid, as well as Chilean schools in Santiago de Chile. Permissions from the Regional Education Board and the School Board were obtained. Before data collection, ethical approval was obtained from the Universidad Politécnica de Madrid (IRB protocol number not provided) and from the Universidad de Santiago de Chile (Ethical Report No. 170/2023). All participants were treated in accordance with the ethical guidelines (American Psychological Association, 2017) concerning parental consent, confidentiality, anonymity of responses, and the right to withdraw. Demographic characteristics of the sample are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample demographics.

2.2. Measures

The attitudes of children without disabilities toward the inclusion of children with disabilities in PE were assessed using the Student Attitudes Toward Integrated Physical Education (CAIPER-R) instrument (Ocete et al., 2017). This is an adapted and validated version of the Children’s Attitudes Towards Integrated Physical Education—Revised (CAIPE-R) (Block, 1995). It consists of 10 items (6 items to assess general attitudes and 4 items for the specific scale). The degree of agreement or disagreement with each item is expressed on a four-point Likert scale (1 = no, 2 = probably not, 3 = probably yes, 4 = yes). The questionnaire was preceded by questions collecting demographic information about the participants: date of birth, gender, school, education level, and previous contact with people with disabilities. The questionnaire resulted in a Cronbach’s alpha value greater than 0.70. For the exploratory analysis, the obtained two-factor model explained 53.95% of the variance, and the initial quality measures of the analysis were highly satisfactory, with a sampling adequacy index of KMO = 0.767 and a significant Bartlett’s test of sphericity (χ2 = 640.27, df = 45, p < 0.001). For the confirmatory factor analysis, the model fit was evaluated according to the main goodness-of-fit indices, obtaining satisfactory results based on the generally recommended values of GFI > 0.90 and RMSEA < 0.08 (Ocete et al., 2017).

2.3. Research Design and Procedure

In the first instance, the Regional Educational Board in each of the four regions, respectively, invited all schools in their area to take part in the ISS program during the 2021–2022 academic year. Subsequently, the same Educational Board assessed each application individually. Three applications were selected to participate in Extremadura, four in Ibiza, 26 in Madrid, and seven in Santiago de Chile. Once the educational institutions were formally informed that they had been accepted to participate in the ISS program, the PE teacher in charge of the ISS development and the school principal signed an agreement to participate in this research. This document explained the purpose of the study, the methods, respect for anonymity in handling personal data, and ethical approval. Once these criteria were met, the PE teachers selected the students to participate in the study. These are all students enrolled in PE. Each teacher received an email containing a link to the online questionnaire to be completed by their students so that they could supervise their participation in fulfilling it. An informed consent form was included with each questionnaire and accepted by each individual before they accessed the instruments. A total of 3817 individuals completed the online questionnaire, of which 85 (2.22%) missed one of the demographic questions for further identification and had to be excluded. Finally, 3732 students (97.77% of the total) satisfactorily completed the questionnaire and were included in the final sample. All responses were collected between September 2021 and April 2022. The questionnaire was completed before students participated in any ISS program-related activities.

2.4. Data Analysis

Descriptive statistical analyses were conducted to represent participants’ demographic characteristics. Descriptive statistics are presented in frequency, percentages, mean (M), and standard deviation (SD). To meet the validation objective of the CAIPER-R instrument, a validation procedure was performed using a split-half cross-validation procedure. The dataset was randomly divided into two sets: the train and test datasets. The train dataset was used to perform an exploratory factor analysis (EFA), to then confirm the structure using confirmatory factor analysis in the test dataset. When assessing EFA, given the multidimensional nature of the CAIPER-R, we evaluated the number of latent variables performing Parallel Analysis (Hayton et al., 2004; Raîche et al., 2013). The expectation was to confirm the same 2 subscales observed in CAIPE-R original version. Once this number was determined, we evaluated multivariate normality of the items using the Henze–Zirklers’s test. In the case where multivariate normality was not met, we proceeded using Principal Axis Factorization Extraction instead of Maximum Likelihood (Costello & Osborne, 2005; de Winter & Dodou, 2012). Expecting that up to some point CAIPER-R’s subdimensions may be associated, we used an oblimin rotation. EFA was performed using 1000 bootstrap iterations to report the mean of the loadings and 95% confidence intervals. We expected all loadings to be above 0.3, without sub or cross loadings. Items that would not fit these criteria were removed. After the evaluation of the CAIPER-R structure, we proceeded to evaluate its internal consistencies using Cronbach’s Alpha. We also included Total Omega following the criticism of many authors about only using Cronbach’s Alpha (Dunn et al., 2014; Peters, 2014; Sijtsma, 2009). Confidence intervals were also provided using 1000 bootstrap iterations.

Once the structure was defined for using exploratory factor analysis with the train dataset, we proceeded to perform a confirmatory factor analysis in the test dataset using the CAIPER-R structure obtained with the exploratory factor analysis. We estimated again internal consistencies, reporting global fits; Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) as diagnostic parameters. We also report the EFA structure and internal consistencies of the test data. CFA was followed by a multiple-group confirmatory factor analysis for measurement invariance with continuous and ordinal indicators (Hirschfeld & Von Brachel, 2014). The usual procedure is to evaluate four different levels of invariance: configural, weak (metric), strong (scalar), and strict (residual) (Putnick & Bornstein, 2016). Configural invariance indicates that the same factor structure is held in the different evaluated groups. Weak invariance evaluates if factor loadings are the same between groups. Strong invariance evaluates whether intercepts and loadings are equivalent in the evaluated groups. Finally, strict invariance evaluates if residual variances are equal across groups in addition to strong invariance constraints. All four invariance models are evaluated to assess if they differ significantly. Significant differences are indicative of a lack of invariance. However, if the invariance fit index is significant but marginally different, one can interpret that invariance is present (Cheung & Rensvold, 2002). All four invariance models were evaluated, and goodness of fit was contrasted from the least to the strictest model.

In the second step, to respond to the second objective of knowing the attitudes of students without disabilities towards the inclusion of children and adolescents with disabilities in PE in Spain and Chile, the normality of the distribution and the homogeneity of the variance of the data were evaluated using Shapiro–Wilk tests to determine the suitability of the parametric techniques for data analysis. Since normality was not met, non-parametric tests were used. For the descriptive analysis, the data are presented as means and standard deviations.

The Kruskal–Wallis rank-sum test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test with continuity correction was used to determine the contrasts between variables and was applied separately for each independent variable. Each of the instrument’s subscales (General Physical Education, Specific Physical Education, Total) was considered as a dependent variable, and as independent variables “gender” (boy and girl), “city” (Extremadura, Ibiza, Madrid, Santiago), and “previous contact with people with disabilities” (Yes or No). In the case of the city, pairwise Dunn’s multiple comparison test was applied for the post hoc analysis of the contrasts. For the effect size, the Cohen’s r, considering a 0.3 (small effect), 0.30–<0.5 (moderate effect), and ≥0.5 (large effect).

Given that this statistical approach does not allow for evaluating interactions between factor variables, as it would be the case if we were able to apply parametric statistics, we included a final analysis using Conditional Regression Trees, a particular case of Classification and Regression Trees models (CART; Strobl et al., 2009). One of the primary reasons for using CART models is their resilience to collinearity and their ability to detect variable interactions without the need to specify them explicitly, allowing us to perform a regression-like model but assessing the interactions using a non-parametric approach.

CART model is interpreted by following its hierarchical structure, which is like a flowchart. Interpretation begins at the root node, which represents the entire dataset. From this node, divisions (branches) follow based on the conditions of the model variables (features). Each branch leads to an internal node containing a new question about another variable. The process continues until reaching a leaf node, which is the final prediction.

A significant p-value < 0.05 was considered for the entire process, with a confidence interval of 95% (Cohen, 1988). All analyses were conducted using the R project (version 4.4.1).

3. Results

Our first objective was the CAIPER-R validation, which began with an EFA analysis. The results indicated the elimination of item 4 due to cross-loading (EFA = −0.35, CFA = −0.16), the presence of negative values indicates that it is not a good item for generating analysis or prediction processes. Therefore, the use of the 9-item instrument was considered based on the factor analysis. When inspecting internal consistencies, General Physical Education presented a good internal consistency of 0.84, and Specific Physical Education, 0.69 and 0.68 using Cronbach’s Alpha and McDonald’s Omega, respectively (Table 2). Given our heterogeneous sample, we also performed an analysis of invariance. The results show invariance for the configural hypothesis. However, stronger constraints lead to significant differences. These significant differences were due to minor changes in the fit index. Since the changes in the CFI are less than 0.01 even for the most restrictive invariance model, we conclude that, in practice, the CAIPER-R shows invariance for these different cities (Table 3). By presenting invariance, we assume, as stated in the methodology, that we can compare the study groups.

Table 2.

Exploratory and Confirmatory Factor Analysis Factor Loadings Report.

Table 3.

Cultural Invariance Analysis.

Given the reliable results of CAIPER-R validation, we proceed to evaluate our goals concerning the impact of city of origin, gender, and previous contact on inclusion. As shown in Table 4, Extremadura presented significant differences in contrast with the other communities, driving the results obtained for global scores (c2 = 27.3, df = 3, p-value = 4.9 × 10−6) and Global Physical Education (c2 = 33.0, df = 3, p-value = 3.0 × 10−7), presenting higher CAIPER-R scores. For Specific Physical Education, we also found significant differences (c2 = 21.9, df = 3, p-value = 6.7 × 10−5), but in this case, mostly driven by differences in the Madrid community and presenting almost negligible effects (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Pairwise Wilcoxon rank-sum test with continuity correction with Holm–Sidak multiple comparison correction posthocs derived from Kruskal–Wallis results for CAIPER-R total and subscales.

Gender also presented significant results for Global Score (W = 1,311,140, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16), Global Physical Education (W = 1,294,320, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16), and Specific Physical education (W = 1,502,091, p-value = 3.264 × 10−13). However, these results present low effects sizes (see Table 5). Finally, previous contact did not present significant results for Global Score (W = 1,762,533, p-value = 0.14), Global Physical Education (W = 1,748,971, p-value = 0.28), and Specific Physical education (W = 1,764,002, p-value = 0.12; see Table 6).

Table 5.

Pairwise Wilcoxon rank-sum test with continuity correction results for CAIPER-R total and subscales contrasted by Gender.

Table 6.

Pairwise Wilcoxon rank-sum test with continuity correction results for CAIPER-R total and subscales contrasted by Previous Contact.

To summarize the comparison results, we can indicate the following:

- −

- Extremadura presented significant differences in contrast to the other cities in all subscales.

- −

- Gender showed significant results in all subscales (with low effect sizes), all favoring better attitudes on the part of girls.

- −

- Prior contact with people with disabilities showed no differences between groups.

Finally, given that non-parametric tests do not allow for evaluating interactions, we applied CART models to explore potential interactions between independent variables.

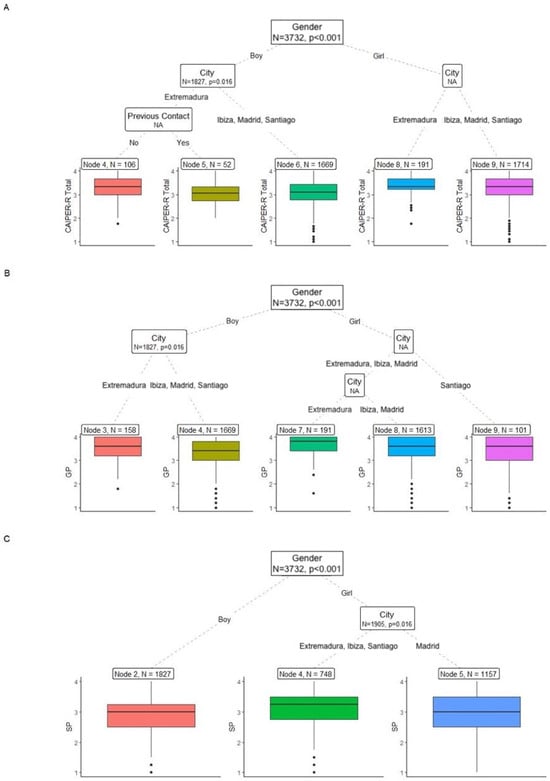

Following its hierarchical structure, interpretation begins at the root node, which represents the entire dataset. For Figure 1A–C, the Root node corresponds to Gender as the main variable. From this node, divisions (branches) follow based on the conditions of the model’s variables (characteristics). The leaf node, which represents the final prediction, corresponds as follows:

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of a conditional regression tree (CART). The root node corresponds to Gender as the main variable. From this node, divisions (branches) follow that correspond to the cities, and then based on the conditions of the variables (characteristics) of the model that correspond to the subscales of the CAPER-R. (A) Gender related to attitudes on the total scale (Total); (B) Gender related to attitudes in General Physical Education (GP); (C) Gender related to attitudes in Specific Physical Education (SP).

As shown in Figure 1, there are differences driven by complex interactions between gender, city, and previous contact. The highest inclusion scores are obtained for girls in Extremadura, while the lowest are for boys in Extremadura with previous contact. When assessing Global Physical Education, we observed that girls presented the highest scores, being the highest in Extremadura, followed by Ibiza and Madrid, with Santiago offering the lowest scores. For boys, Extremadura presents the highest scores, and Ibiza, Madrid, and Santiago with the lowest scores. For Specific Physical Education, the pattern is similar but simplified, being again the girls with the highest scores again, but the girls with the lowest scores were from Madrid. Boys did not present different scores by city.

4. Discussion

The main objective of this study was twofold: first, to validate the CAIPER-R instrument in large student samples from Spain and Chile, and second, to analyze how gender, city of origin, and previous contact with people with disabilities influenced attitudes toward inclusion in PE. Based on prior research (Reina et al., 2019; Block, 2016), we hypothesized that Spanish students would show more positive attitudes than Chilean students, that female students would be more favorable than males, and that previous contact would be positively associated with inclusive dispositions. Results partially confirmed these expectations, demonstrating robust effects for gender and contextual differences across cities, but revealing no significant differences for previous contact. These findings make important contributions to the literature on inclusion in PE by both confirming and challenging key assumptions.

A major contribution of this study lies in deepening the understanding of how inclusive attitudes develop in the PE context. As previous reviews have emphasized (Qi & Ha, 2012; Wilhelmsen & Sørensen, 2017), PE represents a privileged setting where students with and without disabilities can share experiences of motor activity, cooperation, and skill development. Yet, this potential is often constrained by barriers related to peer perceptions and attitudes (Hutzler, 2007; Wang, 2019). The present results show that although attitudes are generally favorable, systematic variations exist depending on sociodemographic variables, such as gender and local context. This reinforces prior evidence that peer attitudes represent one of the most critical determinants of whether SWD experience “good days” or “bad days” in PE (Goodwin & Watkinson, 2000; Holland & Haegele, 2021). Moreover, the fact that Extremadura reported the highest inclusion scores suggests that inclusive school climates and teacher preparedness (Rojo-Ramos et al., 2022a, 2022b) are instrumental in shaping students’ openness to participation alongside peers with disabilities.

The city-based differences revealed by our analyses deserve special attention. Extremadura students consistently scored higher on inclusion measures compared to those in Madrid, Ibiza, and Santiago. Previous research suggests that such differences may stem from the degree to which inclusive education policies are translated into school-level practices (Muñoz-Hinrichsen et al., 2024a; Arroyo-Rojas & Hodge, 2024). While Spain and Chile share legislative frameworks aligned with the UN 2030 Agenda (Ainscow, 2020a; UNESCO, 2017b), the implementation of these policies is uneven. Extremadura has been noted for teacher development initiatives and stronger traditions of inclusive PE practice (Rojo-Ramos et al., 2022a), which may explain its comparatively higher scores. On the contrary, it is likely that the lower attitudinal indicators in Santiago de Chile students compared to other cities are justified by the shorter life span of activities aimed to facilitate the inclusion of SWD (Arroyo-Rojas & Hodge, 2024). These results suggest that legislative similarity does not guarantee attitudinal homogeneity, and that local adaptations and cultural contexts continue to play decisive roles in shaping how students perceive inclusion.

Gender emerged as another robust predictor (Hutzler, 2003), with female students demonstrating consistently more positive attitudes across all CAIPER-R subscales. This finding is consistent with previous research showing that girls report higher empathy, prosocial behaviors, and openness to inclusion in educational contexts (Reina et al., 2019; Delgado-Gil et al., 2023). In the specific case of PE, girls’ greater acceptance may be linked to socialization processes that emphasize collaboration over competitiveness, contrasting with boys’ greater orientation towards performance and ability comparison (Block & Obrusnikova, 2007; Hutzler et al., 2005). Nonetheless, effect sizes in our study were small, which suggests that while gender differences are statistically robust, their practical implications may be modest. This observation aligns with the idea that inclusive dispositions are multi-determined, and that educational interventions—rather than demographic factors—play a stronger role in shaping long-term inclusive mindsets (Grassi-Roig et al., 2025).

Perhaps one of the most surprising findings was the absence of significant differences related to previous contact with individuals with disabilities. Contrary to both our hypothesis and prior evidence suggesting a positive role of contact (Reina et al., 2019; Ocete et al., 2020), our results indicate that the simple presence of such experiences is insufficient to shape students’ attitudes. This phenomenon may be attributed, in part, to the adoption of novel educational models in both countries that prioritize inclusive practices. The younger generations in these countries have become more familiar with, receptive to, and cognizant of inclusive policies (Ministerio de Educación de la República de Chile, 2015; Ministerio de Educación y Formación Profesional, 2020). Furthermore, there is a greater prevalence of social interaction with individuals with disabilities, which is associated with a range of contacts beyond those of an academic nature, encompassing domains of social development. The sports context is a pertinent exemplar in this regard, given its role in the establishment of models that are oriented towards inclusion. In Chile, this is evidenced by the implementation of the 20,978 Law, which recognizes adapted and Paralympic sports (Ministerio del Deporte de la República de Chile, 2016), and the 20,422 Law, which establishes rules on equal opportunities and social inclusion of persons with disabilities (Ministerio de Planificación de la República de Chile, 2010). In Spain, these processes have been recognized for an extended period since the foundation of the Spanish Paralympic Committee in 1995 (Comité Paralímpico Español, 2025), the approval of the General Law on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and their social inclusion (Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad, 2013), and lately, the 39/2022 Law on Sport, where inclusive sport is defined and promoted (Jefatura del Estado, 2022). This result underscores the need to distinguish between superficial, unstructured contact and carefully designed, meaningful interactions. Indeed, prior interventions such as Paralympic School Day (McKay et al., 2015, 2019) and Inclusive Sport at School (Grassi-Roig et al., 2025) have shown that experiential, pedagogically supported contact significantly improves student attitudes. Our finding therefore highlights a critical implication: educational systems should not assume that exposure alone is enough but should ensure structured opportunities for contact, built around collaboration, role reversal, and reflection (Gobbi et al., 2024).

Another important aspect of our results relates to cultural invariance. The validation analyses demonstrated that the CAIPER-R instrument functioned adequately across groups, confirming configural invariance and showing only marginal differences in stricter models. This supports the interpretability of results across culturally diverse, Spanish-speaking contexts, echoing similar findings in motivational and attitudinal research in sport (Franco et al., 2019; López-Walle et al., 2011). The ability to compare attitudes across regions is especially relevant in the context of global initiatives toward inclusive education (Ainscow, 2020b), as it provides robust evidence that the constructs measured are not biased by cultural factors. However, the contextual differences found between cities highlight that measurement equivalence does not imply attitudinal uniformity, which reinforces the importance of studying local facilitators and barriers (Muñoz-Hinrichsen et al., 2024a; Sammon et al., 2020). As posited by Byrne (2004), a robustness test of measurement instruments could be performed prior to conducting a cross-cultural differences analysis providing support for potential inferences generated in this investigation methodologically. This situation would facilitate the emergence of new research domains focused on the comparison of diverse cultural manifestations within a specific paradigm.

These findings must be interpreted within the broader framework of educational policy. Both Spain and Chile have enacted strong legislative measures in favor of inclusion (Ministerio de Educación de la República de Chile, 2015; Ministerio de Educación y Formación Profesional, 2020; Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad, 2013). Nonetheless, as noted by Ainscow (2020a, 2020b), policy frameworks are only as effective as their implementation in schools. As mentioned above, the fact that Extremadura outperformed other cities despite a shared legislative context suggests that localized adaptations, teacher training, and community engagement play crucial roles in shaping the lived reality of inclusion. This reflects previous concerns raised in comparative studies showing that, even with similar laws, cultural and institutional practices can produce diverging outcomes (Maher & Haegele, 2024). Strengthening teacher preparation (Rojo-Ramos et al., 2022b), allocating resources, and embedding inclusive practices within PE curricula therefore appear as essential steps to ensure that legislative intentions translate into equitable educational experiences.

5. Limitations

Despite the strengths of this study, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the research design relied on self-reported measures of attitudes, which may be influenced by social desirability bias and do not necessarily reflect actual behaviors in inclusive PE settings. While the CAIPER-R instrument demonstrated adequate validity and reliability, future studies should complement attitudinal questionnaires with observational or qualitative data to capture more nuanced perspectives of students’ lived experiences. Second, the sample, although large and diverse, was restricted to four Spanish-speaking cities. This limits the generalizability of the findings beyond the specific cultural and educational contexts of Spain and Chile. Attitudes toward inclusion may differ substantially in other regions with distinct sociocultural dynamics, legislative traditions, and levels of policy implementation. Third, the cross-sectional design precludes establishing causal relationships. While gender and city of origin were associated with differences in attitudes, it remains unclear whether these factors directly shape inclusivity or whether they are proxies for deeper variables, such as teacher training, school culture, or community values. Longitudinal research would help clarify the directionality and stability of these effects. Fourth, although previous contact with people with disabilities was included as a variable, the measure did not capture the quality, duration, or context of such experiences. Prior literature (McKay et al., 2015; Ocete et al., 2020) emphasizes that meaningful, structured contact is more influential than mere exposure. The binary measure used in this study may therefore oversimplify a complex construct and partially explain the lack of significant results. Finally, while the study demonstrated cultural invariance of the CAIPER-R across the four cities, small differences in stricter invariance models suggest that certain items may function differently depending on the local context. Although these differences were minor, they highlight the need for continued validation work in broader and more diverse cultural samples.

6. Conclusions

This study provides evidence on the factors shaping students’ attitudes toward the inclusion of peers with disabilities in PE, with gender and city of origin emerging as significant predictors, while previous contact showed no effect. The validation of the CAIPER-R instrument further strengthens its use in cross-cultural research on inclusive education. Variation across cities reflects differences in local implementation and resource distribution. For a practical perspective, PE teachers can foster inclusion through structured contact activities that promote meaningful interactions between students with and without disabilities. Programs such as Inclusive Sport at School or Paralympic School Day provide tested models for fostering empathy, cooperation, and positive perceptions. In addition, teachers should receive continuous professional development to increase their competence and confidence in inclusive practices. Future research should use longitudinal or mixed-methods designs and assess the quality of prior contact in terms of quality, reciprocity, emotional tone, and frequency. In conclusion, our findings emphasize the necessity for a multi-level approach to inclusion, indicating that legislative frameworks, whilst essential, are insufficient on their own. The active role of teachers, the provision of structured and meaningful contact experiences, and the allocation of resources at the local level are all essential variables in the creation of truly inclusive PE experiences.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.G.-R. and F.M.-H.; methodology, F.M.-H. and J.C.; software, R.C.V.; validation, J.P.-T., J.C. and M.G.-R.; formal analysis, R.C.V.; investigation, J.P.-T. and J.C.; resources, M.G.-R. and F.M.-H.; data curation, R.C.V.; writing—original draft preparation, M.G.-R. and F.M.-H.; writing—review and editing, J.P.-T. and J.C.; visualization, R.C.V.; supervision, J.P.-T. and J.C.; project administration, J.P.-T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the University of Santiago de Chile (protocol code: 170/2023; date of approval: 3 April 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ainscow, M. (2020a). Inclusion and equity in education: Making sense of global challenges. Prospects, 49(3–4), 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainscow, M. (2020b). Promoting inclusion and equity in education: Lessons from international experiences. Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy, 6(1), 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychological Association. (2017). Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct (pp. 1–20). American Psychological Association. Available online: https://www.apa.org/ethics/code/index.html (accessed on 18 June 2024).

- Arroyo-Rojas, F., & Hodge, S. R. (2024). Perspectives on Inclusion in physical education from faculty and students at three physical education teacher education programs in Chile. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 43(4), 636–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertills, K., & Björk, M. (2024). Facilitating regular Physical Education for students with disability—PE teachers’ views. Front. Sports Act. Living, 6, 1400192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, M. (1995). Development and validation of the children’s attitudes toward integrated physical education—Revised (CAIPE-R) inventory. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly, 12(1), 60–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, M. (2016). A teacher’s guide to adapted physical education: Including students with disabilities in sports and recreation (4th ed.). Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co., Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Block, M., & Obrusnikova, I. (2007). Inclusion in physical education: A review of the literature from 1995–2005. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly, 24(2), 103–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B. M. (2004). Testing for multigroup invariance using AMOS graphics: A road less traveled. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 11(2), 272–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 9(2), 233–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Comité Paralímpico Español. (2025). Qué es el CPE. Comité Paralímpico Español. Available online: https://www.paralimpicos.es/CPE/que-es (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Costello, A. B., & Osborne, J. (2005). Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, 10(7), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Gil, S., Mendoza-Muñoz, D. M., Galán-Arroyo, C., Denche-Zamorano, Á., Adsuar, J. C., Mañanas-Iglesias, C., Castillo-Paredes, A., & Rojo-Ramos, J. (2023). Attitudes of non-disabled pupils towards disabled pupils to promote inclusion in the physical education classroom. Children, 10(6), 1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Winter, J. C. F., & Dodou, D. (2012). Factor recovery by principal axis factoring and maximum likelihood factor analysis as a function of factor pattern and sample size. Journal of Applied Statistics, 39(4), 695–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, T. J., Baguley, T., & Brunsden, V. (2014). From alpha to omega: A practical solution to the pervasive problem of internal consistency estimation. British Journal of Psychology, 105(3), 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, E., Coterón, J., & Martínez, A. (2019). Invarianza cultural del cuestionario de la orientación a la tarea y al ego (TEOSQ) y diferencias en las orientaciones motivacionales entre adolescentes de España, Argentina, Colombia y Ecuador. Diversitas: Perspectivas en Psicología, 15(1), 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freer, J. R. R. (2023). Students’ attitudes toward disability: A systematic literature review (2012–2019). International Journal of Inclusive Education, 27(5), 652–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobbi, E., Amatori, S., Perroni, F., Sisti, D., Rocchi, M., & Neuber, N. (2024). Impact of a model-based paralympic sports project in physical education on primary school pupils’ attitudes, self-efficacy, and intentions toward inclusion of peers with physical disabilities. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, D., & Watkinson, E. (2000). Inclusive physical education from the perspective of students with physical disabilities. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly, 17(2), 144–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassi-Roig, M. (2024). Procesos de inclusión en educación física: El programa “Deporte inclusivo en la escuela” como estudio de caso [Doctoral thesis, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassi-Roig, M., Bores-García, D., Haegele, J. A., & Pérez-Tejero, J. (2025). Disability awareness sport and physical education interventions: A systematic literature review from 1992 to 2023. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 1, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayton, J. C., Allen, D. G., & Scarpello, V. (2004). Factor retention decisions in exploratory factor analysis: A tutorial on parallel analysis. Organizational Research Methods, 7(2), 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschfeld, G., & Von Brachel, R. (2014). Improving multiple-group confirmatory factor analysis in R-A tutorial in measurement invariance with continuous and ordinal indicators. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, 19(7), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, K., & Haegele, J. A. (2021). Perspectives of students with disabilities toward physical education: A review update 2014–2019. Kinesiology Review, 10(1), 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutzler, Y. (2003). Attitudes toward the participation of individuals with disabilities in physical activity: A review. Quest, 55(4), 347–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutzler, Y. (2007). A systematic ecological model for adapting physical activities: Theoretical foundations and practical examples. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly, 24(4), 287–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutzler, Y., Zach, S., & Gafni, O. (2005). Physical education students’ attitudes and self-efficacy towards the participation of children with special needs in regular classes. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 20(3), 309–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jefatura del Estado. (2022). Ley 39/2022, de 30 de diciembre, del deporte. Boletín Oficial Del Estado, 314, 1–87. [Google Scholar]

- López-Walle, J., Tristán, J., Isabel Castillo, I., & Balaguer, I. (2011). Invarianza factorial del TEOSQ en jóvenes deportistas mexicanos y españoles. Revista Mexicana de Psicología, 28(1), 53–61. [Google Scholar]

- Maher, A. J., & Haegele, J. A. (2024). Beyond spatial materiality, towards inter- and intra-subjectivity: Conceptualizing exclusion in education as internalized ableism and psycho-emotional disablement. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 45(4), 531–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, C., Block, M., & Park, J. Y. (2015). The impact of paralympic school day on student attitudes toward inclusion in physical education. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly, 32(4), 331–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, C., Haegele, J., & Block, M. (2019). Lessons learned from paralympic school day: Reflections from the students. European Physical Education Review, 25(3), 745–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Educación de la República de Chile. (2015). Ley 20845 (pp. 1–56). Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional de Chile. Available online: http://bcn.cl/2f8t4 (accessed on 26 May 2025).

- Ministerio de Educación y Formación Profesional. (2020). Ley orgánica 3/2020, de 29 de diciembre, por la que se modifica la ley orgánica 2/2006, de 3 de mayo, de educación. Boletín Oficial del Estado, 340, 122868–122953. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Planificación de la República de Chile. (2010). Ley 20422. Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional de Chile. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad. (2013). Real decreto legislativo 1/2013, de 29 de noviembre, por el que se aprueba el texto refundido de la ley general de derechos de las personas con discapacidad y de su inclusión social. Boletín Oficial del Estado, 289, 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio del Deporte de la República de Chile. (2016). Ley 20978. Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional de Chile. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Hinrichsen, F. I., Camargo-Rojas, D. A., Grassi-Roig, M., Torres-Paz, L., Martínez-Aros, A., & Herrera-Miranda, F. (2024a). Facilitadores y barreras para la inclusión de estudiantes con discapacidad en educación física en Colombia, Chile, España y Perú. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 158, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Hinrichsen, F. I., Grassi-Roig, M., & Pérez-Tejero, J. (2024b). Deporte inclusivo en la escuela en Chile. In P. Vargas Garcés, & F. Herrera Miranda (Eds.), Bienestar y discapacidad: Contribuciones desde una mirada amplia y diversa (pp. 225–233). Universidad Andrés Bello. Available online: https://repositorio.unab.cl/handle/ria/59390 (accessed on 9 February 2025).

- Ocete, C., Pérez-Tejero, J., & Coterón, J. (2015). Propuesta de un programa de intervención educativa para facilitar la inclusión de alumnos con discapacidad en educación física. Retos, 27(1), 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocete, C., Pérez-Tejero, J., Coterón, J., & Reina, R. (2020). How do competitiveness and previous contact with people with disabilities impact on attitudes after an awareness intervention in physical education? Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 27(1), 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocete, C., Pérez-Tejero, J., Franco, E., & Coterón, J. (2017). Validación de la versión española del cuestionario “Actitudes de los alumnos hacia la integración en educación física (CAIPE-R)”. Psychology, Society and Education, 9(3), 447–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, G.-J. Y. (2014). The alpha and the omega of scale reliability and validity. The European Health Psychologist, 16(2), 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Tejero, J., Barba, M., García-Abadía, L., Ocete, C., & Coterón, J. (2013). Deporte inclusivo en la escuela. In J. Pérez-Tejero, M. Barba, & L. García-Abadía (Eds.), Serie “Publicaciones del CEDI—3”. Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, Fundación Sanitas, Psysport. [Google Scholar]

- Pocock, T., & Miyahara, M. (2018). Inclusion of students with disability in physical education: A qualitative meta-analysis. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 22(7), 751–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnick, D. L., & Bornstein, M. H. (2016). Measurement invariance conventions and reporting: The state of the art and future directions for psychological research. Developmental Review, 41, 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, J., & Ha, A. S. (2012). Inclusion in physical education: A review of literature. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 59(3), 257–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raîche, G., Walls, T. A., Magis, D., Riopel, M., & Blais, J. G. (2013). Non-graphical solutions for Cattell’s scree test. Methodology, 9(1), 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reina, R., Hutzler, Y., Iniguez-Santiago, M. C., & Moreno-Murcia, J. A. (2019). Student attitudes toward inclusion in physical education: The impact of ability beliefs, gender, and previous experiences. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly, 36(1), 132–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojo-Ramos, J., González-Becerra, M. J., Merellano-Navarro, E., Gómez-Paniagua, S., & Adsuar, J. C. (2022a). Analysis of the attitude of Spanish physical education teachers towards students with disabilities in Extremadura. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(9), 5043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojo-Ramos, J., Manzano-Redondo, F., Adsuar, J. C., Acevedo-Duque, Á., Gomez-Paniagua, S., & Barrios-Fernandez, S. (2022b). Spanish physical education teachers’ perceptions about their preparation for inclusive education. Children, 9(1), 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sammon, K., Baker, L., & Lieberman, L. J. (2020). Overcoming inclusion barriers for students with disabilities in physical education. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation and Dance, 92(1), 51–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sijtsma, K. (2009). On the use, the misuse, and the very limited usefulness of Cronbach’s alpha. Psychometrika, 74(1), 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strobl, C., Malley, J., & Tutz, G. (2009). An introduction to recursive partitioning: Rationale, application, and characteristics of classification and regression trees, bagging, and random forests. Psychological Methods, 14(4), 323–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira Fabricio dos Santos, L. G., Arroyo-Rojas, F., Martinez Rivera, S., Felipe Castelli Correia de Campos, L., Nowland, L. A., Wilson, W. J., & Haegele, J. A. (2025). Barriers and facilitators to including students with down syndrome in integrated physical education: Chilean physical educators’ perspectives. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 44(1), 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. (2017a). MINEPS VI—Plan de acción de Kazán. UNESCO. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000252725.locale=es (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- UNESCO. (2017b). UNESCO moving forward the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. UNESCO. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000247785.locale=es (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Wang, L. (2019). Perspectives of students with special needs on inclusion in general physical education: A social-relational model of disability. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly, 36(2), 242–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelmsen, T., & Sørensen, M. (2017). Inclusion of children with disabilities in physical education: A systematic review of literature from 2009 to 2015. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly, 34(3), 311–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (2007). International classification of functioning, disability and health. Children & youth version. World Health Organization.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).