Abstract

Gifted students with neurodivergent profiles such as ADHD, autism, or dyslexia demonstrate unique cognitive and learning characteristics that can shape their educational experiences and socio-emotional development. Often referred to as twice-exceptional (2e), these students benefit from environments that recognise their strengths while responding to their diverse learning needs. Understanding the interplay between giftedness and neurodivergence is therefore essential for fostering strengths-based environments to support these students’ overall well-being. This review focuses on 2e students with ADHD, a subgroup within the gifted population who remain underexamined in the current literature. While existing research has emphasised the academic and diagnostic complexities associated with this cohort, limited studies have focused on the socio-emotional factors influencing their development. This systematic view aimed to identify and synthesise findings from existing research on the socio-emotional factors influencing the mental health of gifted students with ADHD. A comprehensive search was conducted across the EBSCO, ProQuest, and ProQuest Dissertations & Theses databases. Following PRISMA guidelines, 10 studies out of 438 met the predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria and were critically appraised using the JBI checklists for qualitative and cross-sectional designs. These 10 papers were categorised based on authorship, title, year of publication, population, study design, theoretical frameworks, key findings, and identified risk or protective factors. The findings indicate that gifted students with ADHD experience distinct challenges in forming and maintaining peer relationships. Additionally, the intersection of giftedness and ADHD is noted as a potential risk factor, rather than a protective factor, for lower self-esteem and social connectedness. The limitations of this review, along with implications for future research and educational practice, are discussed.

Keywords:

ADHD; gifted; mental health; social and emotional development; twice exceptional; students 1. Introduction

Twice-exceptional (2e) students represent a distinct population characterised by unique and often complex cognitive and behavioural profiles alongside diverse social and academic experiences. Often defined as individuals with high abilities in one or more domains alongside co-occurring neurodivergence such as ADHD or autism, 2e students often think, learn, and engage with their environments in ways that differ from their peers (Foley Nicpon et al., 2011). As a sub-group within the broader gifted population, 2e students have been consistently underrepresented in both educational and psychological research (Jolly & Barnard-Brak, 2024; Leggett et al., 2010). This can be partially attributed to the ongoing uncertainties and inconsistencies regarding the definition and identification of twice exceptionality (Romano et al., 2024; Reis et al., 2014).

1.1. Beyond Ordinary: The Multidimensional Concept of Giftedness

Although giftedness has been extensively researched, its conceptualisation remains subject to ongoing debate, with no universally accepted definition (Carman, 2013). Some approaches have emphasised high IQ scores as the primary indicator of giftedness (Pezzuti et al., 2022; McClain & Pfeiffer, 2012), whereas others advocate for multidimensional models that incorporate creativity, task commitment, and contextual factors (J. S. Renzulli, 2021). Current debates about terminology remain complex. Terms like ‘giftedness’, ‘high ability’, and ‘exceptionally able’ typically emphasise cognitive potential, whereas ‘talent’ is increasingly understood to involve broader dimensions such as creativity, task commitment, and domain-specific achievement (Pei et al., 2021; García-Perales et al., 2024). Consistent with the definition proposed by the National Association for Gifted Children (NAGC), this review conceptualises giftedness as “those who demonstrate outstanding levels of aptitude (defined as an exceptional ability to reason and learn) or competence (documented performance or achievement in top 10% or rarer) in one or more domains. Domains encompass any structured area of activity with its own symbol system (e.g., mathematics, music, language) and/or set of sensorimotor skills (e.g., painting, dance, sports)” (NAGC, 2014). Although researchers view this definition as comprehensive, the ongoing lack of consensus regarding a definition of giftedness, as well as the ambiguity surrounding its conceptual boundaries, continues to pose challenges for the identification of gifted learners. Additionally, although giftedness is typically highlighted as a strength, research has increasingly acknowledged that gifted students may also present with additional learning differences or neurodivergent traits, including attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (Romano et al., 2024; Cornoldi et al., 2023; Lee & Olenchak, 2015).

1.2. Beyond Hyperactivity: Understanding ADHD

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental condition characterised by differences in attention regulation, impulse control, and activity level. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed., DSM-5-TR: American Psychiatric Association, 2022) identifies three primary presentations: predominantly inattentive, predominantly hyperactive/impulsive, and combined presentation. It is present in approximately 8% of the global adolescent and child population and between 5.9% and 7.1% of children in Ireland (Ayano et al., 2024; Willcutt, 2012). Given its prevalence, ADHD continues to have a central focus within educational and psychological research. ADHD in children and adolescents can influence multiple aspects of their developmental and educational experiences. Research examining ADHD in student populations has consistently found that it is often associated with distinct social and emotional challenges. More specifically, studies on ADHD have emphasised particular challenges in socio-emotional development such as interactions with authority figures, e.g., teachers, as well as in sustaining friendships with same-age peers (Staff et al., 2023; Gardner & Gerdes, 2015). Evidence also suggests that children and adolescents identified with ADHD are more likely to experience peer rejection and may struggle with social acceptance and belonging (Grygiel et al., 2018; Frondelius et al., 2019). Consequently, these students are likely to experience additional emotional and behavioural challenges, including symptoms of depression and anxiety (Barkley, 2015).

1.3. Beyond Labels: Navigating Giftedness and ADHD

The interaction between giftedness and ADHD characteristics can be a source of difficulty for students who recognise their potential but experience academic and social challenges due to the differences associated with ADHD (Mullet & Rinn, 2015). Although giftedness and ADHD can co-occur, their interaction has historically received limited empirical attention. Hartnett et al. (2004) was among the first to highlight the diagnostic and interpretive challenges associated with identifying these students. In their study, they presented a vignette describing a boy exhibiting characteristics of both giftedness and ADHD to a sample of 44 university counselling students. The authors concluded that the considerable overlap in behavioural presentations between ADHD and giftedness can complicate accurate identification of either construct. Characteristics such as elevated activity levels, variable attention, and impulsivity can be observed in both gifted and ADHD profiles and may increase the risk of misdiagnoses or under-identification (Mendaglio, 2012; K. M. Antshel et al., 2007). Within ADHD, such behaviours are understood to reflect underlying neurological and cognitive differences, whereas in gifted students, similar behaviours may emerge as a response to environmental factors such as insufficient challenges or boredom in the classroom (Besnoy et al., 2021). In their systematic review, Mullet and Rinn (2015) identified three primary interaction patterns between giftedness and ADHD: (a) ADHD may obscure a student’s giftedness, (b) giftedness may obscure ADHD, or (c) the two may interact in such a way that they effectively mask each other, resulting in the student appearing to have no additional learning needs.

Research with 2e students have frequently emphasised the challenges associated with their identification. Reported prevalence rates vary considerably as the construct of twice exceptionality remains difficult to define and operationalise (Cheek et al., 2023). Ronksley-Pavia (2020) estimated that approximately 7–9% of the population may be twice-exceptional. However, identification remains complex due to substantial individual variability within this group (Gierczyk & Hornby, 2021). For example, a student may demonstrate excellent verbal reasoning or vocabulary while simultaneously experiencing literacy-related difficulties. Additionally, a gifted student with a reading-related learning difficulty may display different characteristics compared to a gifted student who is autistic. In their study, Reis et al. (2014) observed that 2e students may not consistently demonstrate either high performance or learning differences, as “their gifts may mask their disabilities and their disabilities may mask their gifts” (Reis et al., 2014, p. 222). Furthermore, gifted students with ADHD may face an increased risk of socio-emotional challenges arising from the interaction between their advanced cognitive abilities and ADHD-related characteristics. These challenges can contribute to experiences of peer rejection and misinterpretation of their behaviours by peers, teachers, and parents (Grygiel et al., 2018; Frondelius et al., 2019). Consequently, such experiences may lead to the development of negative self-perceptions related to both academic and social performances, which can, in turn, adversely impact socio-emotional development (Grimell et al., 2025; Foley Nicpon et al., 2011).

1.4. Socio-Emotional Development

Socio-emotional development refers to an individual’s growing understanding of their own identity, emotions, and social interactions (Duyar et al., 2023). During primary and post-primary years, socio-emotional development serves as a critical predictor of academic achievement, engagement in risk behaviours, and overall mental health (Berger et al., 2011; Ferreira et al., 2012; Allen et al., 2014). Research examining students with ADHD has indicated that they are more likely to encounter socio-emotional challenges related to peer interactions and school performance (Giannakopoulos, 2025; binti Marsus et al., 2022). In a quantitative study, Abrahão and Elias (2021) found that students with ADHD scored significantly lower on the Inventory of Social Skills Rating System (SSRS-BR) compared to a reference sample.

Research also indicates that giftedness can shape socio-emotional development. In a meta-analysis, Litster and Roberts (2011) found that gifted students consistently reported higher scores of academic, behavioural, and overall self-concept compared with their non-gifted peers. Similarly, Papadopoulos (2021) reported that increased cognitive ability was positively correlated with both academic competence and self-esteem. A more recent meta-analysis synthesising research study completed between 2005 and 2020 further supported these findings, indicating that gifted students demonstrate higher general and academic self-concept than non-gifted students (Infantes-Paniagua et al., 2022). Additionally, social competence has been reported to be stronger among gifted learners compared to their non-gifted peers (Citil & Özkubat, 2020).

1.5. Socio-Emotional Development and Twice Exceptionalism

Socio-emotional factors play a critical role in overall development and in shaping mental health outcomes. In general, research has consistently emphasised that positive social relationships and well-developed emotional regulation skills significantly influence mental health and well-being across the lifespan (Santini et al., 2016). Affecting approximately 970 million people worldwide, mental health is defined by the World Health Organisation (2019) as “a state of mental well-being that enables people to cope with the stresses of life, realize their abilities, learn well and work well, and contribute to their community”. Despite growing recognition of the importance of mental health across developmental contexts, research specifically examining the mental health of gifted students with ADHD remains limited. However, existing studies suggest that these students experience socio-emotional challenges comparable to those reported by their non-gifted peers with ADHD. In a quantitative study involving 112 students aged 6–18, Foley-Nicpon et al. (2012) found that their participants scored lower on measures of behavioural self-concept, self-esteem, and overall happiness compared to their non-ADHD gifted peers. Similarly, longitudinal research by K. Antshel et al. (2008) found that over a 4.5-year period, gifted children and young adults with ADHD exhibited significantly higher levels of mood and anxiety symptoms, as well as greater difficulties in social and academic competence, than gifted students without ADHD.

1.6. Conceptual Framework of the Systematic Review

Bronfenbrenner’s Process–Person–Context–Time (PPCT) Bioecological model provides a comprehensive framework for examining how socio-emotional factors influence the mental health of gifted students with ADHD. The model emphasises the dynamic interactions between an individual, their immediate environment, the broader social context, and the developmental changes that occur over time (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006). In this review, particular attention is given to the Person and Context components of the model. At the individual level (Person), understanding the socio-emotional factors that affect mental health requires consideration of these students’ diverse traits, abilities, and neurodevelopmental profiles. At the environmental level (Context), the model highlights the importance of factors such as peer relationships, school environments, and access to support services, all of which can meaningfully shape socio-emotional experiences and mental health outcomes.

The existing literature emphasises the processes involved in identifying ADHD, as well as the controversies surrounding dual identification (Process). In contrast, this review aims to examine the socio-emotional factors that contribute to the well-being of this population, drawing specially on the Person and Context components of the PPCT framework. As the impact of Process and Time is beyond the scope of the present review, these elements are not emphasised. By recognising and understanding the risk factors and challenges experienced by these learners, psychologists and educators are better equipped to provide targeted support systems and effective interventions that foster resilience, strengthen identity development, and promote positive mental health outcomes.

Despite growing attention to 2e students within educational and psychological research, no systematic review to date has directly focused on the socio-emotional factors contributing to the mental health of gifted students with ADHD.

This systematic review therefore aims to synthesise existing research examining the socio-emotional factors that influence the mental health and well-being of these individuals. It aims to summarise the associated risk and protective factors within this population. To achieve this, the systematic review will address the following research questions:

- What socio-emotional factors (e.g., low self-esteem, anxiety, peer relationship challenges) are experienced by gifted students with ADHD aged 6–18 years?

- What are the risk and protective factors associated with the mental health of this population?

2. Methodology

2.1. Search Procedures

This review followed the PRISMA 2020 guidelines (Page et al., 2021) for research synthesis and analysis. The review protocol was not registered, and this is acknowledged in the Limitations section of this paper. Electronic searches were conducted on 28 August 2025 across the following databases: EBSCOhost (APA Psych Info, ERIC, APA PsychArticles Academic Search Complete, British Education Index) and ProQuest (Social Science Premium Collection, Education Collection, Medline, Social Science Database). These databases were selected because they index a broad range of education, psychology, and social science journals in which research on twice-exceptional learners is most published. Given that this topic represents an emerging field within educational and psychological research, published articles in peer-reviewed journals are limited. To address this and reduce publication bias, this review incorporated grey literature. Grey literature can be highly relevant and contain rigorous methodologies and novel empirical findings that are yet to reach formal publication. Accordingly, the ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global database was utilised, and an electronic search was completed on 29 August 2025. The Boolean search string was developed to capture relevant studies addressing both giftedness and ADHD, with an emphasis on social and emotional outcomes. The final search string was as follows: Abstract (“twice-exceptional” OR “2e” OR “dual exceptionalities” OR “gifted AND learning disability” OR “high ability” OR “high functioning” OR “exceptionally able” OR gifted OR giftedness OR talent*) AND Abstract (ADHD or “attention deficit hyperactivity disorder” OR “attention deficit disorder” OR “attention-deficit-hyperactivity-disorder”) AND (“mental health” OR social OR emotion* OR internalising OR externalising OR withdrawal OR anxiety OR depress* OR “self-concept” OR “self-esteem”).

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

To be included in this systematic review, studies were required to meet the following criteria:

- Identification of giftedness: Participants were required to be identified as gifted or high ability through standardised psychometric measures.

- ADHD diagnosis: Participants were required to have a formal clinical diagnosis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder or identified as having ADHD according to recognised diagnostic frameworks (e.g., DSM-V or ICD-10).

- Age range: Participants were required to be between 6 and 18 years of age, encompassing both childhood and adolescence.

- Socio-emotional focus: Studies were required to examine socio-emotional variables such as emotional regulation, peer relationships, self-concept, self-esteem, or other indicators of mental health and well-being.

- Language: Studies were required to be published in English as translation resources were unavailable for this review.

- Study design: Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods designs were eligible for inclusion.

- Publication Period: Studies published between 2000 and 2024 were included, as the term twice-exceptional only became an officially recognised the early 2000s.

- Grey literature: Doctoral theses and master’s dissertations were included to capture emerging research within this developing field.

Studies were excluded from the review if they met any of the following criteria:

- Publication date: published prior to the year 2000.

- Participation age: did not include participants aged between 6 and 18 years of age.

- Population focus: examined twice-exceptional individuals without an explicit reference to ADHD.

- Study type: studies classified as a systematic review, meta-analysis, or book chapter, rather than a primary empirical study.

- Language: published in a language other than English.

These exclusion parameters ensured that the review focused on empirical research examining socio-emotional outcomes among school-aged, 2e students formally identified as gifted with ADHD.

2.3. Screening Process and Study Identification

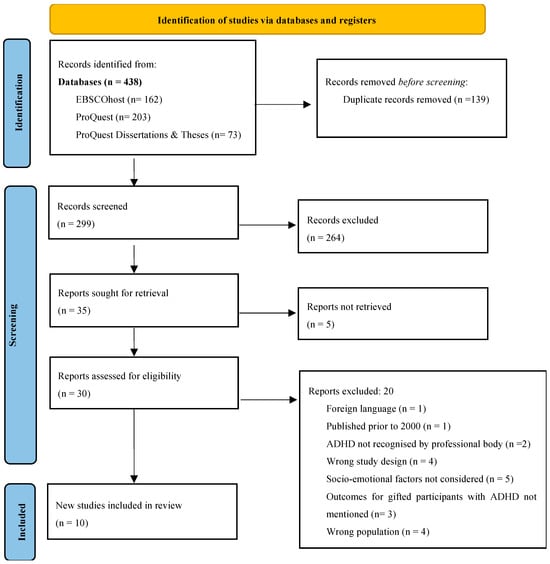

A descriptive analytic approach was employed to synthesise the data retrieved from the search process. A narrative synthesis was conducted on the included studies to summarise and evaluate current knowledge regarding gifted students with ADHD, in line with the research aims. Following the application of the refined search string and inclusion and exclusion criteria, the database searches yielded 162 studies from EBSCOhost, 203 from ProQuest, and 73 from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses. All search results were exported into Covidence, a software platform designed to support systematic review screening and data management. Title and abstract screening were carried out independently by two reviewers (RMD, LL). Discrepancies at each stage were resolved through discussion. After removal of 139 duplicate records, 299 empirical studies remained for screening. Title and abstract screening, based on the inclusion/exclusion criteria, resulted in the exclusion of 264 articles, leaving 35 articles for full-text and in-depth screening. Of the 35 records identified for full-text screening, five could not be retrieved through university library holdings or direct correspondence with the authors. The remaining 30 studies were obtained and reviewed. This process resulted in the exclusion of 20 studies for the following reasons: non-English language (1 study), published prior to the year 2000 (1 study), did not include participants with a formal ADHD diagnosis (2 studies), wrong study design (4 studies), socio-emotional outcomes not reported (5 studies), no specific findings related to 2e participants with ADHD (3 studies), or wrong participant population (4 studies). The remaining ten studies met all inclusion criteria and were included in the synthesis. Each article was independently reviewed by two researchers (RMD, LL). Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion until full consensus was reached. The study selection process is illustrated in Figure 1, following the PRISMA 2020 guidelines (Page et al., 2021). Excluded full tests are provided in Appendix A.

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram. Note: adapted from The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews (Page et al., 2021). For more information, visit http://www.prisma-statement.org (accessed on 15 September 2025).

2.4. Coding Procedure

Descriptive data was extracted from each study by two reviewers (RMD, LL) and entered into a data extraction table created in Microsoft Excel. This table included key study characteristics such as the following:

- Study title;

- Authors;

- Year of publication;

- Country of origin;

- Study design.

To address the research questions, data relevant to the identification and diagnosis of twice-exceptional students with ADHD were extracted and summarised in a dedicated section of the Excel file. An additional section captured study findings related to key socio-emotional constructs including self-esteem, self-concept, peer relationship quality, emotional regulation, and internalising symptoms such as anxiety and depression. These constructs were selected because they represent the core socio-emotional domains most frequently identified in the literature as relevant to the experiences and developmental outcomes of students. Specifically, self-esteem, self-concept, and peer relationships reflect central aspects of social functioning and identity formation, while emotional regulation and internalising symptoms represent critical indicators of mental health vulnerability. The instruments utilised in each study were also recorded. Another section of the Excel file was divided into two subsections to distinguish between identified protective and risk factors, both of which were central to this review. A final section was reserved for general information identified by the researchers as pertinent to the synthesis and to future research recommendations.

In line with the PPCT model, particular attention was paid to identifying factors that reflected internal characteristics such as personal traits and individual profiles (Person) and environmental characteristics such as peer relationships and support systems (Context). These elements informed both the extraction categories and analyses. After data extraction, initial codes were generated to capture recurring patterns across the data. The coding process was also guided by the PPCT framework, whereby codes were created in relation to the Person and Context dynamics that shaped students’ socio-emotional outcomes. These codes were refined and grouped into four broader conceptual categories. The final framework comprised four overarching themes: (1) Challenges in Peer Relationships and Social Isolation, (2) Vulnerabilities in Self-Perception, (3) Emotional Regulation Difficulties, and (4) Protective Factors: A Missing Component. Appendix B contains sample first-level codes and demonstrates how they were mapped onto these final themes.

The quality of the included studies alongside risk assessment biases was independently assessed by two reviewers using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal Checklists. The JBI provides specific checklists tailored to different study designs (Aromataris et al., 2015). Each checklist comprises between 8 and 10 items and includes response options of yes (criterion clearly met) or no, unclear, or not applicable (criterion not fully met or insufficiently reported). A quantitative scoring system was applied to evaluate study quality. Each checklist item received a score of 1 if the criterion was met, 0.5 if the reviewer was uncertain, and 0 if the criterion was not met. Individual item scores were then summed to produce an overall quality score, which was subsequently converted into a percentage. Studies were categorised as high quality (80–100%), moderate quality (40–70%), or low quality (0–30%). Quality appraisals were initially conducted by the primary reviewer and independently validated by a second reviewer to ensure reliability.

3. Results

Table 1 provides a summary of the ten studies, detailing their location, participant characteristics, identified risk and protective factors, and quality appraisal scores. The studies were published between 2001 and 2025, with sample sizes ranging from a single participant (Turk & Campbell, 2003; Cross et al., 2020) to 141 participants (K. M. Antshel et al., 2007). Most studies (n = 8) were conducted in the United States, while one study was carried out in Canada and another in Sweden. Across all studies, participant ages ranged from 6 to 30 years.

Table 1.

Table of included studies.

3.1. Quality Appraisal Scores

None of the studies included in the review were of low methodological quality. Overall, quality scores ranged from 60% to 88%. Study quality was calculated using the Joanna Briggs Institute critical appraisal criteria. Each score was converted into an overall percentage to enable comparability across studies. Quantitative studies were assessed using the 8-item JBI checklist for cross-sectional studies (Holmgren et al., 2023; Ford, 2007; Moon et al., 2001; Turk & Campbell, 2003; K. M. Antshel et al., 2007; Kauder, 2009). Qualitative studies were critically appraised using the 10-item JBI checklist for qualitative research (Foley-Nicpon et al., 2012; Fosenburg, 2018; Cross et al., 2020; Fugate & Gentry, 2016).

All studies clearly articulated their aims and research questions and employed appropriate methodologies to address them. Although standardised measures were used across all studies, only one study (Foley-Nicpon et al., 2012) discussed potential biases and confounding variables. All studies, apart from Turk and Campbell (2003), situated their findings within the context of previous research.

3.2. Overview of Studies

3.2.1. Theoretical Perspectives

Only two of the studies in this review explicitly identified a theoretical framework when investigating gifted students with ADHD (Fosenburg, 2018; Kauder, 2009). Fosenburg (2018) employed Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Model to explain the impact of twice exceptionalism on friendship quality, whereas Kauder (2009) applied Social Cognitive Theory to explore identity development among twice-exceptional students.

3.2.2. Measurements of Concepts

Giftedness measurements: As part of the inclusion criteria, all studies were required to identify giftedness using standardised measures. Among the five studies that explicitly reported the standardised tool utilised, three utilised the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC-V; Holmgren et al., 2023; Foley-Nicpon et al., 2012; K. M. Antshel et al., 2007). Two of these studies also incorporated the Wechsler Individual Achievement Test (WIAT III) (Holmgren et al., 2023; Foley-Nicpon et al., 2012). K. M. Antshel et al. (2007) additionally utilised scores from the Wide Range Achievement Test—Revised Edition (WRAT-R). Another standardised measure utilised was the Otis-Lennon School Ability test (Moon et al., 2001). The remaining studies noted that giftedness was assessed using standardised or psychometric assessments but did not specify the instruments used. Fosenburg (2018) noted they required participants to score within the 91st percentile or higher on a standardised measure to meet their criteria for giftedness.

ADHD measurement: Across all included studies, ADHD diagnoses were provided by qualified professionals such as psychologists, doctors, and psychiatrists or by private clinics. None of the studies specified the reasons for referral or described the diagnostic procedures used to confirm ADHD among participants.

Socio-Emotional Measurements: Of the ten studies, five studies utilised qualitative methods of data collection, primarily semi-structured interviews (Ford, 2007; Fugate & Gentry, 2016; Holmgren et al., 2023; Moon et al., 2001; Turk & Campbell, 2003). Thematic analyses from these studies identified several socio-emotional challenges associated with being gifted and having ADHD. Other studies utilised standardised instruments to assess socio-emotional functioning. These measures included the Behaviour Assessment System for Children (BASC-2), the Piers-Harris Children’s Self-Concept Scale (Foley-Nicpon et al., 2012), the Friendship Quality Scale (Fosenburg, 2018), Connors, Home Situations Questionnaire—revised, and the School Situations Questionnaire—revised (Moon et al., 2001).

3.2.3. Risk Factors Identified

All ten studies identified socio-emotional risk factors associated with the coexistence of ADHD and giftedness in students. The literature consistently found that 2e students with ADHD face more challenges in forming and maintaining peer relationships than their peers who are only gifted, only have ADHD, or are neither gifted nor have ADHD. Foley-Nicpon et al. (2012) found that gifted students with ADHD scored lower on measures of self-esteem, behavioural self-concept, and overall happiness than gifted students without a co-existing diagnosis. Similar findings regarding the negative associations between twice-exceptionalism, self-esteem, and self-concept were indicated in Kauder’s (2009) study. Fosenburg (2018) noted that participants with ADHD, regardless of ability, reported significantly less companionship and connection with a best friend than those without ADHD.

Giftedness did not appear as a protective factor against friendship quality. This was also noted in Ford’s (2007) study, whereby social immaturity among gifted participants with ADHD contributed to a lack of friendships, frustration due to unawareness of social cues, and emotional difficulties. These findings align with those of Turk and Campbell (2003), who reported that boredom, social isolation stemming from misinterpreting social cues, and challenges managing expectations negatively impacted participant’s social experiences. In their retrospective study, Cross et al. (2020) reported that their male participant experienced social isolation and feelings of being misunderstood, which contributed to emotional distress and led to death by suicide. Moon et al. (2001) found that their gifted male participants with ADHD experienced difficulties regulating their emotions, challenges with peer relationships, and family stress. Notably, giftedness appeared to exacerbate the social and emotional difficulties associated with ADHD in boys. Conversely, Fugate and Gentry (2016), focusing on gifted girls with ADHD, reported that girls often experience social isolation, frustration, lower confidence levels, and feelings of being misunderstood by their peers.

3.2.4. Protective Factors Identified

Among the ten studies, only one identified potential protective factors for gifted children with ADHD. Fugate and Gentry (2016) highlighted that supportive teachers and friendships strengthen participants’ motivation and emotional well-being. This finding underscores the important role of educational environments in supporting the socio-emotional development of this population. No other study reported any protective factors related to socio-emotional development, highlighting a notable gap in strength-based research with twice-exceptional individuals.

3.3. Certainty of the Evidence

The overall certainty of evidence across the included studies was appraised using an adapted GRADE framework (Guyatt et al., 2011). Each socio-emotional outcome (peer relationships, self-esteem/self-concept, emotional regulation, risk, and protective factors) was assessed across five domains: risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias. Certainty ratings ranged from very low to moderate. Evidence for peer relationship difficulties and emotional regulation challenges was of moderate certainty, supported by consistent findings across multiple studies despite small sample sizes and heterogeneity in methods. Evidence regarding self-esteem and self-concept was of low certainty, reflecting limited quantitative data. Findings related to potential protective factors, such as supportive teacher relationships, was based one on exploratory study and was therefore rated very low in certainty.

These assessments suggest that while socio-emotional difficulties among gifted adolescents with ADHD are consistently reported, further large-scale, longitudinal, and theoretically grounded research is needed to confirm the strength and scope of these associations.

4. Discussion

This review synthesised and analysed demographic information, measures, and key findings from ten published studies focusing on gifted students with ADHD. The results from the synthesis highlight the complexity of defining giftedness and the scarcity of theoretical frameworks applied to this population. Twice-exceptionality had a notable impact on socio-emotional development and mental health across all ten studies. The following discussion presents the review findings and is organised into the four key themes that emerged from the syntheses; Challenges in Peer Relationships, Vulnerabilities in Self-Perception, Emotional Regulation Difficulties, and Protective Factors: A Missing Component.

4.1. Theme 1: Challenges in Peer Relationships

Across all synthesised studies, 2e students were consistently identified as facing significant socio-emotional difficulties, particularly in relation to peer relationships. Research by Fosenburg (2018), Ford (2007), and Moon et al. (2001) indicated that gifted students with ADHD often struggle with social maturity, interpreting social cues, and maintaining friendships. These challenges may be exacerbated by the “masking” effect, whereby strong cognitive abilities can conceal social and ADHD-related difficulties, leading teachers, and peers to overestimate these students’ social competence (Mullet & Rinn, 2015). The gap between cognitive and socio-emotional development can contribute to confusion and self-blame when social interactions are perceived as more challenging than academic demands. For example, Moon et al. (2001) found that high intellectual abilities heightened students’ awareness of social disparities, intensifying feelings of isolation. Case studies further illustrate experiences of social exclusion and being misunderstood, which in some instances contributed to severe mental health challenges (Turk & Campbell, 2003; Cross et al., 2020).

Gender differences in peer relationship difficulties also emerged as an important finding. Fosenburg (2018) reported that boys with ADHD tended to have weaker friendships than girls, suggesting that externalising behaviours and/or impulsivity associated with ADHD may more strongly influence boys’ peer relationships. Conversely, Fugate and Gentry (2016) found that gifted girls with ADHD often experienced social isolation and frustration but benefited from supportive teachers and strong peer relationships. These patterns suggest gender-specific mechanisms whereby boys may experience greater peer rejection due to behaviour that deviates from social norms, while girls may internalise their difficulties, resulting in feelings of inadequacy, masking, and low confidence. These differences have significant implications for assessment and intervention. Boys may require support targeting social skills, emotional regulation, and peer integration, whereas girls may benefit more from relationally focused interventions that prioritise validation, self-understanding, and strategies to reduce reliance on masking as a coping mechanism.

4.2. Theme 2: Vulnerabilities in Self-Perception

Self-perceptions emerged as a key area of vulnerability for gifted students with ADHD. Foley-Nicpon et al. (2012) and Kauder (2009) found that participants exhibited lower self-esteem, diminished behavioural self-concept, and reduced overall happiness compared with gifted peers without ADHD. The “masking” effect likely contributes to these difficulties, as external expectations based on high cognitive ability may clash with internal struggles related to ADHD. Students may interpret these discrepancies as personal failure rather than recognising them as consequences of neurodevelopmental differences. Emotional regulation difficulties, particularly when combined with stress in family and school contexts, further exacerbate these challenges and contribute to negative self-evaluations (Moon et al., 2001).

Cross et al. (2020) also highlighted the significant influence of perfectionism in gifted students (Grugan et al., 2025; Liao et al., 2025). Consistent with previous research, perfectionism in high-ability students can contribute to maladaptive patterns, including excessive concern over mistakes, fear of criticism, and the setting of unrealistically high expectations (Sánchez-Moncayo et al., 2025; Noor, 2023). These tendencies increase the likelihood of negative self-evaluations, heightened anxiety, and emotional exhaustion (Toshev, 2025). Consequently, the mismatch between internal struggles and external expectations can create a cycle in which students feel pressured to perform yet perceive themselves as incapable of meeting either self-imposed or socially imposed standards. This dynamic contributes to maladaptive coping behaviours and low self-esteem. Furthermore, perfectionistic tendencies may amplify the effects of ADHD-related impulsivity and executive function difficulties, making it more challenging for students to regulate frustration and manage emotional responses effectively (Chęć et al., 2025).

4.3. Emotional Regulation Difficulties

Emotional regulation difficulties emerged as a pervasive challenge throughout the synthesised literature. Case studies provided valuable insight into the lived experiences of 2e students with ADHD, with participants reporting difficulties in managing emotions, coping with boredom, experiencing isolation, and feeling misunderstood (Turk & Campbell, 2003; Cross et al., 2020). High cognitive abilities may heighten students’ awareness of social or academic challenges, which can intensify emotional distress when they are unable to meet internal or external expectations. Consequently, this can increase their vulnerability to anxiety, depression, and maladaptive coping strategies (Chęć et al., 2025; Cross et al., 2020). Cross et al. (2020) further illustrate the emotional consequences of repeated mismatches between ability, expectations, and social-emotional capacity. These findings underscore how the interaction of high cognitive ability, socio-emotional difficulties, and ADHD-related differences can heighten the risk of mental health challenges. Additionally, the interplay between giftedness, perfectionism, and ADHD demonstrates that individual traits may amplify socio-emotional risk rather than serve as protective factors, highlighting the importance of considering the full profile of twice-exceptional students when designing interventions.

4.4. Protective Factors: A Missing Component

A notable finding across the literature is the limited attention given to socio-emotional protective factors for 2e students. While some studies highlighted the importance of supportive teachers, mentors, and friendships (Fugate & Gentry, 2016), giftedness alone did not appear to serve as a protective buffer. In some cases, advanced cognitive abilities heightened students’ awareness of discrepancies between their abilities and social-emotional skills, intensifying feelings of frustration, isolation, and stress (Moon et al., 2001). These findings underscore the need for tailored interventions that address both the cognitive and emotional needs of twice-exceptional learners.

These findings can be interpreted through the lens of the theoretical framework employed in this review. Bronfenbrenner’s PPCT Bioecological Model emphasises the interaction between individual characteristics (Person) and the multiple environmental systems that shape development (Context). The review highlights a disparity between the cognitive and socio-emotional development of 2e students, providing insight into why giftedness alone does not serve as a socio-emotional protective factor for students with ADHD. While these students may exhibit advanced cognitive abilities, differences in their emotional regulation, executive functioning, and social skills may create internal discrepancies within the Person component of the PPCT model. These individual-level vulnerabilities can then interact with Context stressors, such as peer difficulties, inconsistent school supports, or environments that prioritise academic performance over emotional needs. This interaction may exacerbate socio-emotional risk rather than buffer it, increasing the likelihood of mental health difficulties (Lukito et al., 2025; Helsper et al., 2025). Accordingly, the PPCT framework provides an explanation for a central finding of this review: giftedness alone is insufficient to offset the socio-emotional challenges associated with ADHD. The interaction between individual characteristics and environment can amplify, rather than mitigate, vulnerability to mental health difficulties in this population.

4.5. Implications for Practice and Future Research

Across the studies synthesised, the importance of examining 2e students was consistently emphasised. Given the ambiguity that surrounds this population, it is apparent that it remains challenging to research, conceptualise, and fully understand what it means to be twice-exceptional. Findings from this review highlighted that giftedness does not appear to serve as a protective factor for socio-emotional well-being among gifted children and adolescents with ADHD. These results underscore the need for strength-based yet realistic approaches in both educational and psychological contexts.

In educational settings, these findings have significant implications. Teachers, special educators, and psychologists require targeted professional development to recognise and respond to the complex profiles of 2e learners. Traditional differentiation strategies for gifted students or behavioural interventions for ADHD alone are insufficient. Educators must understand the nuanced interplay between high ability and attentional or emotional regulation difficulties. Developing evidence-based, individualised support plans that integrate both enrichment and socio-emotional support is critical. Examples of classroom strategies can include scheduled breaks to support emotional regulation, scaffolding multi-step instructions to accommodate executive function difficulties and offering extracurricular activities aligned with students’ interests to foster peer relationships. Such tailored interventions are better suited to address the unique challenges faced by twice-exceptional students, rather than relying on generalised strategies designed solely for giftedness or ADHD.

The review also highlighted a lack of consistent theoretical frameworks underpinning current research and interventions. This limitation constrains the development of evidence-based practices grounded in a comprehensive understanding of the intersection between giftedness and ADHD. Future research should adopt clear, standardised, and theory-driven criteria for assessing both giftedness and ADHD, and for their relationship with self-concept and socio-emotional development. Longitudinal studies are needed to investigate how the timing of ADHD diagnosis relative to gifted identification influences long-term outcomes such as self-esteem, emotional regulation, and peer relationships. Additionally, intervention research should explicitly evaluate the protective role of supportive teachers, mentors, and peers, identifying which targeted strategies most effectively reduce socio-emotional risk in twice-exceptional learners. Such research would provide critical evidence to inform the development of tailored, evidence-based supports for this complex population.

4.6. Limitations

While this review provides a comprehensive analysis of the current literature on gifted students with ADHD, several limitations should be acknowledged. Although the review was conducted systematically, it is possible that relevant studies were missed or excluded based on qualitative judgements. Additionally, as this review employed a narrative synthesis, the identification and synthesis of findings inherently involved subjective interpretation, which may reduce transparency (De Cassai et al., 2025).

A further limitation is that the review protocol was not prospectively registered in a repository such as PROSPERO or the Open Science Framework. Protocol registration promotes transparency, reduces risk of bias, and strengthens methodological credibility by documenting planned procedures in advance. Although the review adhered to PRISMA guidelines, the absence of a registered protocol means that any deviations from the initial search or analysis cannot be independently verified.

The review was also limited by the small number of available studies, some of which included grey literature. Additionally, the majority of included studies utilised qualitative or mixed-methods designs with small samples. While these studies valuable insights into the socio-emotional experiences of 2e students, limited sample sized constrain the generalisability and robustness of the research. Consequently, the findings and implications should be interpreted with caution. Given the ambiguity surrounding the definition of ‘giftedness’, some potentially relevant studies may have been excluded if they did not explicitly describe how giftedness was measured or operationalised.

A final limitation concerns geographical and linguistic bias. Only English-language studies were included, and all identified studies were conducted in Western countries. This may affect the generalisability and representativeness of the findings reported in this synthesis, as conceptualisation of giftedness and the assessment tools used to measure ability and attainment may vary greatly across cultural and educational contexts.

5. Conclusions

This review contributes to the growing body of literature on 2e students by synthesising and evaluating evidence on the socio-emotional experiences of gifted students with ADHD. The findings highlight the complexity of defining giftedness, the lack of theoretical grounding in existing research, and the considerable socio-emotional challenges faced by this population.

Across studies, giftedness did not emerge as a protective factor and, in some cases, appeared to exacerbate social and emotional difficulties. Notably, nine of the ten studies did not identify any protective factors, despite examining multiple domains of socio-emotional functioning. This suggests that the co-occurrence of giftedness and ADHD may create a profile in which advanced cognitive abilities do not buffer against vulnerabilities related to peer relationships, emotional regulation, and self-perception. These outcomes underscore the importance of adopting holistic, theory-driven, and strength-based approaches in both educational and clinical contexts.

It is recommended that future research move beyond deficit-oriented perspectives in attempt to understand the dynamic interplay between giftedness and ADHD fully. This includes developing consistent assessment frameworks, clarifying diagnostic criteria, and conducting longitudinal and cross-cultural studies to explore developmental trajectories of these students. By integrating robust theoretical perspectives and prioritising individualised evidence-based interventions, educators, clinicians, and researchers can more effectively support the socio-emotional well-being and potential of 2e students.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.M., J.S. and O.I.; methodology, R.M. and J.S.; software, R.M. and L.L.; validation, R.M. and L.L.; formal analysis, R.M. and L.L.; investigation, R.M. and J.S.; data curation, R.M., L.L. and J.S.; writing—original draft preparation, R.M. and J.S.; writing—review and editing, R.M., J.S. and O.I.; supervision, R.M. and J.S.; project administration, R.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Extracted data tables are available on request. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

List of full-text articles excluded at the eligibility stage with reasons for exclusion is provided.

Table A1.

List of full-text articles excluded at the eligibility stage with reasons for exclusion is provided.

| Author(s) and Year of Publication | Study Title | Exclusion Reason |

|---|---|---|

| Al-Rousan et al. (2025) | Network Analysis of Internalizing and Externalizing Symptoms in Arab Gifted Children: A Cross-Sectional Study. | Outcomes for gifted participants with ADHD not specified |

| Bussing et al. (2012) | Academic Outcome Trajectories of Students With ADHD: Does Exceptional Education Status Matter? | No emphasis on socio-emotional factors |

| Byrd et al. (2025) | The Intersection of Giftedness, Disability, and Cultural Identity: A Case Study of a Young Asian American Boy | No emphasis on socio-emotional factors |

| Chiang et al. (2018) | School dysfunction in youth with autistic spectrum disorder in Taiwan: The effect of subtype and ADHD. | Outcomes for gifted participants with ADHD not specified |

| Chou et al. (2019) | Self-Reported and Parent-Reported School Bullying in Adolescents with High Functioning Autism Spectrum Disorder: The Roles of Autistic Social Impairment, Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity and Oppositional Defiant Disorder Symptoms | ADHD not identified by professional body |

| Cobbaert et al. (2024) | Neurodivergence, intersectionality, and eating disorders: a lived experience-led narrative review. | Outcomes for gifted participants with ADHD not specified |

| Dagli et al. (2025) | A Bibliometric Analysis of Research on the Mental Health of Gifted and Talented Children (1948–2025). | Wrong study design |

| Foley-Nicpon et al. (2017) | The effects of a social and talent development intervention for high ability youth with social skill difficulties | Wrong study design |

| Freitas and Del Prette (2013) | Habilidades sociais de crianças com diferentes necessidades educacionais especiais: Avaliação e implicações para intervenção. | Wrong Language |

| Gully (2009) | A study of the talent development of gifted individuals with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder | Wrong population |

| Hidalgo (2018) | Defying the Odds: One Mother’s Experience Raising a Twice-Exceptional Learner | Wrong population |

| Lee and Olenchak (2015) | Individuals with a Gifted/Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Diagnosis | ADHD not identified by professional body |

| Leroux and Perlman (2000) | The Gifted Child with Attention Deficit Disorder: An Identification and Intervention Challenge. | Published prior to year 2000 |

| Lesch (2018) | ‘Shine bright like a diamond!’: is research on high-functioning ADHD at last entering the mainstream? | No emphasis on socio-emotional factors |

| Martin et al. (2010) | Mental Disorders Among Gifted and Nongifted Youth: A Selected Review of the Epidemiologic Literature. | Wrong study design |

| Park (2019) | ADHD, High Ability, or Both: The Paths to Young Adulthood Career Outcomes | No emphasis on socio-emotional factors |

| Pfeiffer (2015) | Gifted students with a coexisting disability: The twice exceptional. | Wrong study design |

| Turk and Campbell (2003) | What’s Right with Doug: The Academic Triumph of a Gifted Student with ADHD. | Wrong population |

| Williams (2024) | Raising Their Voices: Lived Experiences of Gifted Women With ADHD | Wrong population |

| Zentall et al. (2001) | Learning and motivational characteristics of boys with AD/HD and/or giftedness | No emphasis on socio-emotional factors |

Appendix B

Table A2.

Sample codes and their mapping to final themes.

Table A2.

Sample codes and their mapping to final themes.

| Initial Code | Description | Intermediate Category | Final Theme |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feeling Different | Reports of disputes and feelings of misunderstood around peers and friends | Difficulty maintaining friendships | Challenges in Peer Relationships and Social Isolation |

| Negative self-views | Results reflecting low self-worth or self-criticism | Low Self-Esteem | Vulnerabilities in Self-Perception |

| Managing challenging emotions | Difficulty managing emotions that are strong or when under stress such as academic or social stressors | Regulation Challenges in Tricky Contexts | Emotional Regulation Difficulties |

| Lack of Support | Results or lack of results highlighting supports in place or aspects that help promote well-being | Missing environment supports | Absence of Protective Factors |

References

References marked with an asterisk indicate studies included in this review.

- Abrahão, A. L. B., & Elias, L. C. D. S. (2021). Students with ADHD: Social skills, behavioral problems, academic performance, and family resources. Psico-USF, 26, 545–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J., Balfour, R., Bell, R., & Marmot, M. (2014). Social determinants of mental health. International Review of Psychiatry, 26(4), 392–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rousan, A. H., Ayasrah, M. N., & Khasawneh, M. A. S. (2025). Network analysis of internalizing and externalizing symptoms in Arab gifted children: A cross-sectional study. Psychiatric Quarterly, 96(1), 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition DSM-5TM. American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Antshel, K., Faraone, S. V., Maglione, K., Doyle, A., Fried, R., Seidman, L., & Biederman, J. (2008). Temporal stability of ADHD in the high-IQ population: Results from the MGH longitudinal family studies of ADHD. Journal of American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 47, 817–825. [Google Scholar]

- *Antshel, K. M., Faraone, S. V., Stallone, K., Nave, A., Kaufmann, F. A., Doyle, A., Fried, R., Seidman, L., & Biederman, J. (2007). Is attention deficit hyperactivity disorder a valid diagnosis in the presence of high IQ? Results from the MGH longitudinal family studies of ADHD. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 48(7), 687–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aromataris, E., Fernandez, R., Godfrey, C., Holly, C., Kahlil, H., & Tungpunkom, P. (2015). Summarizing systematic reviews: Methodological development, conduct and reporting of an Umbrella review approach. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare, 13(3), 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayano, G., Tsegay, L., Gizachew, Y., Demelash, S., & Alati, R. (2024). The prevalence of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents: An umbrella review of global evidence. European Psychiatry, 67(S1), S76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkley, R. A. (2015). Emotional dysregulation is a core component of ADHD. In R. A. Barkley (Ed.), Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A handbook for diagnosis and treatment (4th ed., pp. 81–115). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, C., Alcalay, L., Torretti, A., & Milicic, N. (2011). Socio-emotional well-being and academic achievement: Evidence from a multilevel approach. Psicologia: Reflexao e Critica, 24, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besnoy, K. D., Jolly, J. L., & Manning, S. (2021). Academic underachievement of gifted students. In Special populations in gifted education (pp. 401–415). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- binti Marsus, N., Huey, L. S., Saffari, N., & Motevalli, S. (2022). Peer relationship difficulties among children with ADHD: A systematic review. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 12(6), 1265–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. A. (2006). The bioecological model of human development. In R. M. Lerner (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology (pp. 793–828). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussing, R., Porter, P., Zima, B. T., Mason, D., Garvan, C., & Reid, R. (2012). Academic outcome trajectories of students with ADHD: Does exceptional education status matter? Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 20(3), 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrd, T. J., Glass, T. B. E., Desmet, O. A., & Olenchak, F. R. (2025). The intersection of giftedness, disability, and cultural identity: A case study of a young Asian American boy. Behavioral Sciences, 15(8), 1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carman, C. A. (2013). Comparing apples and oranges: Fifteen years of definitions of giftedness in research. Journal of Advanced Academics, 24(1), 52–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheek, C. L., Garcia, J. L., Mehta, P. D., Francis, D. J., & Grigorenko, E. L. (2023). The exceptionality of twice-exceptionality: Examining combined prevalence of giftedness and disability using multivariate statistical simulation. Exceptional Children, 90(1), 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chęć, M., Konieczny, K., Michałowska, S., & Rachubińska, K. (2025). Exploring the dimensions of perfectionism in adolescence: A multi-method study on mental health and CBT-based psychoeducation. Brain Sciences, 15(1), 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, H. L., Kao, W. C., Chou, M. C., Chou, W. J., Chiu, Y. N., Wu, Y. Y., & Gau, S. S. F. (2018). School dysfunction in youth with autistic spectrum disorder in Taiwan: The effect of subtype and ADHD. Autism Research, 11(6), 857–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, W. J., Hsiao, R. C., Ni, H. C., Liang, S. H. Y., Lin, C. F., Chan, H. L., Hsieh, Y. H., Wang, L. J., Lee, M. J., Hu, H. F., & Yen, C. F. (2019). Self-reported and parent-reported school bullying in adolescents with high functioning autism spectrum disorder: The roles of autistic social impairment, attention-deficit/hyperactivity and oppositional defiant disorder symptoms. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(7), 1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citil, M., & Özkubat, U. (2020). The comparison of the social skills, problem behaviours and academic competence of gifted students and their non-gifted peers. International Journal of Progressive Education, 16(6), 296–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobbaert, L., Millichamp, A. R., Elwyn, R., Silverstein, S., Schweizer, K., Thomas, E., & Miskovic-Wheatley, J. (2024). Neurodivergence, intersectionality, and eating disorders: A lived experience-led narrative review. Journal of Eating Disorders, 12(1), 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornoldi, C., Giofrè, D., & Toffalini, E. (2023). Cognitive characteristics of intellectually gifted children with a diagnosis of ADHD. Intelligence, 97, 101736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Cross, T. L., Cross, J. R., Dudnytska, N., Kim, M., & Vaughn, C. T. (2020). A psychological autopsy of an intellectually gifted student with attention deficit disorder. Roeper Review, 42(1), 6–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagli, N., Dagli, R., & Haque, M. (2025). A bibliometric analysis of research on the mental health of gifted and talented children (1948–2025). Bangladesh Journal of Medical Science, 24(3), 764–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cassai, A., Dost, B., Tulgar, S., & Boscolo, A. (2025). Methodological standards for conducting high-quality systematic reviews. Biology, 14(8), 973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duyar, S. N., Özkaya, C., & Akdeniz, H. (2023). A systematic review of the factors affecting twice-exceptional students’ social and emotional development. Gifted and Talented International, 38(2), 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M., Simões, C., Gaspar Matos, M., Ramiro, L., Alves Diniz, J., & Team, S. A. (2012). The role of social and emotional competence on risk behaviors in adolescence. The International Journal of Emotional Education, 4, 43–55. [Google Scholar]

- Foley Nicpon, M., Allmon, A., Sieck, B., & Stinson, R. D. (2011). Empirical investigation of twice-exceptionality: Where have we been and where are we going? Gifted Child Quarterly, 55(1), 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley-Nicpon, M., Assouline, S. G., Kivlighan, D. M., Fosenburg, S., Cederberg, C., & Nanji, M. (2017). The effects of a social and talent development intervention for high ability youth with social skill difficulties. High Ability Studies, 28(1), 73–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Foley-Nicpon, M., Rickels, H., Assouline, S. G., & Richards, A. (2012). Self-esteem and self-concept examination among gifted students with ADHD. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 35(3), 220–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Ford, V. M. (2007). High ability and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Their impact on teaching and learning. Library and Archives Canada Bibliothèque et Archives Canada. [Google Scholar]

- *Fosenburg, S. (2018). Investigating friendship qualities in high ability or achieving, typically developing, ADHD, and twice exceptional youth [Ph.D. thesis, University of Iowa]; pp. 8–80. [Google Scholar]

- Freitas, L. C., & Del Prette, Z. A. P. (2013). Habilidades sociais de crianças com diferentes necessidades educacionais especiais: Avaliação e implicações para intervenção. Avances en psicología latinoamericana, 31(2), 344–362. [Google Scholar]

- Frondelius, I. A., Ranjbar, V., & Danielsson, L. (2019). Adolescents’ experiences of being diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A phenomenological study conducted in Sweden. BMJ Open, 9(8), e031570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- *Fugate, C. M., & Gentry, M. (2016). Understanding adolescent gifted girls with ADHD: Motivated and achieving. High Ability Studies, 27(1), 83–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Perales, R., Rocha, A., Aguiar, A., & Almeida, A. I. S. (2024). Characterization of students with high intellectual capacity: The approach in the Portuguese school context and importance of teacher training for their educational inclusion. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1196926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, D. M., & Gerdes, A. C. (2015). A review of peer relationships and friendships in youth with ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders, 19(10), 844–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannakopoulos, G. (2025). Adolescents with ADHD in the school environment: A comprehensive review of academic, social, and emotional challenges and interventions. Journal of Clinical Images and Medical Case Reports, 6, 3528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gierczyk, M., & Hornby, G. (2021). Twice-exceptional students: Review of implications for special and inclusive education. Education Sciences, 11(2), 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimell, J., Ericson, M., & Frick, M. (2025). Identity work among girls with ADHD: Struggling with me and I, impression management, and social camouflaging in school. Frontiers in Psychology, 16, 1591135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grugan, M. C., Olsson, L. F., Hill, A. P., & Madigan, D. J. (2025). Perfectionism, school burnout, and school engagement in gifted students: The role of stress. Gifted Child Quarterly, 69, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grygiel, P., Humenny, G., Rębisz, S., Bajcar, E., & Świtaj, P. (2018). Peer rejection and perceived quality of relations with schoolmates among children with ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders, 22(8), 738–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gully, D. (2009). A study of the talent development of gifted individuals with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. The College of William and Mary. [Google Scholar]

- Guyatt, G. H., Oxman, A. D., Sultan, S., Glasziou, P., Akl, E. A., Alonso-Coello, P., Atkins, D., Kunz, R., Brozek, J., Montori, V., Jaeschke, R., Rind, D., Dahm, P., Meerpohl, J., Vist, G., Berliner, E., Norris, S., Falck-Ytter, Y., Murad, M. H., … The GRADE Working Group. (2011). GRADE guidelines: 9. Rating up the quality of evidence. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 64(12), 1311–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartnett, D. N., Nelson, J. M., & Rinn, A. N. (2004). Gifted or ADHD? The possibilities of misdiagnosis. Roeper Review, 26, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helsper, A., DeShon, L., Boylan, L. E., Galliher, J., & Rubenstein, L. D. (2025). Under pressure: Gifted students’ vulnerabilities, stressors, and coping mechanisms within a high achieving high school. Behavioral Sciences, 15(2), 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hidalgo, M. F. (2018). Defying the odds: One mother’s experience raising a twice-exceptional learner. Research Issues in Contemporary Education, 3(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar]

- *Holmgren, A. C., Backman, Y., Gardelli, V., & Gyllefjord, Å. (2023). On being twice exceptional in Sweden—An interview-based case study about the educational situation for a gifted student diagnosed with ADHD. Education Sciences, 13(11), 1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infantes-Paniagua, Á., Fernández-Bustos, J. G., Ruiz, A. P., & Contreras-Jordán, O. R. (2022). Differences in self-concept between gifted and non-gifted students: A meta-analysis from 2005 to 2020. Annals of Psychology, 38(2), 278–294. [Google Scholar]

- Jolly, J. L., & Barnard-Brak, L. (2024). Special education status and underidentification of twice-exceptional students: Insights from ECLS-K data. Education Sciences, 14(10), 1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Kauder, J. K. (2009). The impact of twice-exceptionality on self-perceptions [Ph.D. thesis, The University of Iowa]. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K. M., & Olenchak, F. R. (2015). Individuals with a gifted/attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder diagnosis: Identification, performance, outcomes, and interventions. Gifted Education International, 31(3), 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leggett, D. G., Shea, I., & Wilson, J. A. (2010). Advocating for twice-exceptional students: An ethical obligation. Research in the Schools, 17(2), 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Leroux, J. A., & Levitt-Perlman, M. (2000). The gifted child with attention deficit disorder: An identification and intervention challenge. Roeper Review, 22(3), 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesch, K. P. (2018). ‘Shine bright like a diamond!’: Is research on high-functioning ADHD at last entering the mainstream? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 59(3), 191–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C. C., Kuo, C. C., Chen, C. H., & Chu, C. C. (2025). Overexcitability and perfectionism: A comparative study of mathematically and scientifically talented, verbally talented, and regular students. Education Sciences, 15(3), 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litster, K., & Roberts, J. (2011). The self-concepts and perceived competencies of gifted and non-gifted students: A meta-analysis. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 11(2), 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukito, S., Chandler, S., Kakoulidou, M., Griffiths, K., Wyatt, A., Funnell, E., Pavlopoulou, G., Baker, S., Stahl, D., Sonuga-Barke, E., & The RE-STAR Team. (2025). Emotional burden in school as a source of mental health problems associated with ADHD and/or autism: Development and validation of a new co-produced self-report measure. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 66(10), 1577–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, L. T., Burns, R. M., & Schonlau, M. (2010). Mental disorders among gifted and nongifted youth: A selected review of the epidemiologic literature. Gifted Child Quarterly, 54(1), 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClain, M. C., & Pfeiffer, S. I. (2012). Identification of gifted students in the United States today: A look at state definitions, policies, and practices. Journal of Applied School Psychology, 28, 59–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendaglio, S. (2012). Overexcitabilities and giftedness research: A call for a paradigm shift. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 35(3), 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Moon, S. M., Zentall, S. S., Grskovic, J. A., Hall, A., & Stormont, M. (2001). Emotional and social characteristics of boys with ADHD and giftedness: A comparative case study. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 24, 207–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullet, D. R., & Rinn, A. N. (2015). Giftedness and ADHD: Identification, misdiagnosis, and dual diagnosis. Roeper Review, 37(4), 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Association for Gifted Children (NAGC). (2014). [Title IX, Part A, Definition 22]. NAGC.org. Available online: https://www.nagc.org/glossary-of-terms (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Noor, B. (2023). Pressure and perfectionism: A phenomenological study on parents’ and teachers’ perceptions of the challenges faced by gifted and talented students in self-contained classes. Frontiers in Education, 8, 1225623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, D. (2021). Examining the relationships among cognitive ability, domain-specific self-concept, and behavioral self-esteem of gifted children aged 5–6 years: A cross-sectional Study. Behavioral Sciences, 11(7), 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S. (2019). ADHD, high ability, or both: The paths to young adulthood career outcomes [Doctoral dissertation, The University of Iowa]. [Google Scholar]

- Pei, M. A., Meyer, M. S., & Plucker, J. A. (2021). Truthmaker semantics and equity in gifted and talented identification. Journal of Minority Achievement, Creativity, and Leadership, 2(1–2), 72–99. [Google Scholar]

- Pezzuti, L., Farese, M., Dawe, J., & Lauriola, M. (2022). The cognitive profile of gifted children compared to those of their parents: A descriptive study using the Wechsler scales. Journal of Intelligence, 10(4), 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeiffer, S. I. (2015). Gifted students with a coexisting disability: The twice exceptional. Estudos de Psicologia, 32(4), 717–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, S. M., Baum, S. M., & Burke, E. (2014). An operational definition of twice-exceptional learners: Implications and applications. Gifted Child Quarterly, 58(3), 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renzulli, J. S. (2021). The three-ring conception of giftedness: A developmental model for promoting creative productivity 4. In Reflections on gifted education (pp. 55–90). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Romano, S., Esposito, D., Aricò, M., Arigliani, E., Cavalli, G., Vigliante, M., Penge, R., Sogos, C., Pisani, F., & Romani, M. (2024). Giftedness and twice-exceptionality in children suspected of ADHD or specific learning disorders: A retrospective study. Sci, 6(2), 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronksley-Pavia, M. (2020). Twice-exceptionality in Australia: Prevalence estimates. Australasian Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 29(2), 18–29. [Google Scholar]

- Santini, Z. I., Fiori, K. L., Feeney, J., Tyrovolas, S., Haro, J. M., & Koyanagi, A. (2016). Social relationships, loneliness, and mental health among older men and women in Ireland: A prospective community-based study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 204, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Moncayo, R., Menacho, I., Ramiro, P., & Navarro, J. I. (2025). Perfectionism and psychological well-being in adolescents with high intellectual abilities. Frontiers in Psychology, 16, 1617755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staff, A. I., Oosterlaan, J., Van der Oord, S., de Swart, F., Imeraj, L., van den Hoofdakker, B. J., & Luman, M. (2023). Teacher feedback, student ADHD behavior, and the teacher–student relationship: Are these related? School Mental Health, 15(1), 287–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toshev, M. (2025). The perfectionism of gifted and talented students. International Journal of Education Teacher, 29, 110–114. [Google Scholar]

- *Turk, T. N., & Campbell, D. A. (2003). What’s right with Doug: The academic struggles of a gifted student with ADHD from preschool to college. Gifted Child Today, 26(2), 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willcutt, E. G. (2012). The prevalence of DSM-IV attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A meta- analytic review. Neurotherapeutics, 9, 490–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, J. (2024). Raising their voices: Lived experiences of gifted women with ADHD. University of Denver. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation. (2019). Mental health. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/mental-health#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Zentall, S. S., Moon, S. M., Hall, A. M., & Grskovic, J. A. (2001). Learning and motivational characteristics of boys with AD/HD and/or giftedness. Exceptional children, 67(4), 499–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).