Abstract

The teaching of natural sciences in complex school contexts, such as border and peripheral zones, faces challenges linked to curricular relevance, teacher preparation, and structural conditions. This study explored the professional demands of elementary teachers in northern Chile through four focus groups with 21 in-service teachers from rural and urban schools in the tri-border region. Thematic analysis revealed challenges including limited disciplinary training, scarce resources, reduced instructional time, and pressure from standardized tests. Enabling factors included the natural environment, students’ experiential knowledge, and interdisciplinary integration. Findings stress the need for situated teacher education policies responsive to territorial realities.

1. Introduction

In borderland territories such as Arica and Parinacota, these figures have an even more complex meaning. The convergence of ethnic diversity, human mobility, rurality, structural precariousness, and socio-environmental challenges shapes settings where nationally prescribed curricula interact tensely with the knowledge, experiences, and living conditions of school communities. In these extreme zones, science teaching necessarily unfolds as a territorial and culturally situated practice, where curricular justice becomes imperative to address realities that are profoundly diverse and often rendered invisible by centralized educational policies.

The global discourse surrounding climate change, the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, the emergence of artificial intelligence, and science and technology policies has intensified interest in science education. Its value is widely recognized in developing scientific competencies for a critical and informed citizenry (Brumann et al., 2022; MINEDUC, 2023; UNESCO, 2022), as well as its strategic role in shaping future generations of scientists, particularly among OECD countries (OECD, 2023).

Within this context, achieving minimum levels of scientific literacy remains an urgent challenge for Chile. According to PISA 2018, 35% of Chilean 15-year-old students do not reach Level 2 in scientific competency, which limits their ability to understand scientific problems, participate in socio-scientific debates, and apply knowledge to improve their quality of life (OECD, 2019).

This scenario becomes more complex by considering the results from the national standardized test (SIMCE, by its acronym in Spanish) administered in 2017 and 2018 for 6th and 8th grades. This test shows that schools in remote regions, particularly in the northern zone of Chile, perform significantly below those in central and southern regions (Agencia de Calidad de la Educación [ACE], 2019). These figures reveal not only persistent learning gaps but also deeper structural tensions within the educational system. Previous studies have highlighted the disconnection between pre-service teacher education and the professional demands of teaching practice (Bastías-Bastías & Iturra-Herrera, 2022; Cabezas et al., 2019; Kleickmann et al., 2016), prompting numerous proposals to improve science instruction (Cofré et al., 2010; Marzabal Blancafort & Merino Rubilar, 2021; Quintanilla & Adúriz-Bravo, 2022). Among these, the enhancement of both initial and ongoing teacher education stands out as a key factor for fostering a critical and contextually grounded scientific literacy (Quintanilla & Adúriz-Bravo, 2022). In particular, science teaching at the elementary level has been underscored as a strategic imperative (Declaración de Budapest, 1999).

From this perspective, research in science education must take into account the specific contexts in which it takes place. Understanding its complexity requires engaging with local knowledge systems and acknowledging historically marginalized voices (Kelly, 2023). Thus, scholarly inquiry in this field must be situated within specific geographic and cultural frameworks and in dialog with emerging socio-territorial realities (Freire-Contreras et al., 2021).

The tri-border region in northern Chile, where Chile, Peru, and Bolivia converge, represents a territory of heightened complexity that demands urgent attention for four key reasons: (1) schools are characterized by high levels of ethnic diversity, migration, and socioeconomic vulnerability (Gómez Chaparro & Sepúlveda, 2022; Mondaca Rojas, 2018; Sánchez Espinosa & Norambuena Carrasco, 2019; Urbina & Sepúlveda, 2020), which presents significant challenges for educational inclusion (Velásquez Semper, 2022); (2) the region faces acute socio-environmental issues such as heavy metal pollution, water scarcity, and land degradation—factors that directly impact science classrooms; (3) student performance on standardized national tests such as SIMCE remains consistently low; and (4) there is a troubling shortage of teachers, particularly in science and mathematics (Consejo Nacional de Educación [CNED], 2021).

Teaching science in this context requires a high degree of professionalism and social commitment. Bridging the gap between pre-service teacher education (PSTE), and territorial challenges demands a science education grounded in curricular justice and local relevance. Schools continue to be key sites in the construction of meaning around science, making it imperative to reimagine pedagogical practices from a situated perspective.

In this process, in-service teachers must be recognized as central agents of educational transformation. Valuing their experiences and the demands they articulate contributes to more informed decision-making regarding teacher education, curriculum planning, assessment, and resource allocation. Acknowledging territorial diversity is not merely an ethical imperative, it is a necessary condition for advancing toward a more equitable science education. This leads us to the guiding question of the present study:

What are the professional demands expressed by elementary school teachers in northern Chile’s border region regarding the teaching of natural sciences?

1.1. Review of Literature

1.1.1. Professional Demands in the Teaching of Natural Sciences in Elementary Education

Teaching natural sciences involves a complex professional practice that encompasses multiple dimensions extending beyond disciplinary knowledge. Barolli et al. (2019) identify key spheres of this work: scientific and pedagogical updating, instructional leadership, support of students’ educational trajectories, institutional participation, and inquiry into one’s own practice, professional projection, and social commitment. This reflects the need for teachers to constantly integrate professional expertise, ethical responsibility, and contextually grounded work.

In addition to these demands, structural factors shape and constrain teaching practice. De Pro Bueno et al. (2022) outline four interrelated levels: socio-educational level (school prestige, resources, and infrastructure), regulatory level (curriculum, policies, student-teacher ratios), formative level (professional pathways and access to the profession), and the school-based level (institutional climate, governance, and relationships with families). These dimensions have a direct impact on teaching in contexts of high vulnerability and cultural diversity.

Within this landscape, teachers have demonstrated adaptive capacities to navigate tensions between their professional knowledge and the demands of the educational system (Canabal García et al., 2017). However, as Cleophas and Francisco (2018) caution, it is also necessary to critically examine the structural causes and the ethical–political implications of these decisions (Iturralde et al., 2017). Teaching science thus becomes a reflective and political act, one that interrogates the present, envisions transformation, and defends the right to relevant and context-sensitive science education (Maturana & Cáceres, 2017).

Despite its importance, research on the specific demands faced by elementary school science teachers in Chile remains limited. Ferrada et al. (2018) note that teachers, especially those in public schools and with substantial teaching experience, call for greater participation in educational policy-making. In the Arica and Parinacota region, the “Voces Docentes” (“Teacher voices”) study conducted by CPEIP (2017) identified urgent needs for professional development in assessment, conflict management, and reflective practice.

Additional demands have also emerged, including calls for greater moral and financial support (Alpaslan & Damlı, 2022), as well as the need to strengthen the connection between institutional collaboration and science learning outcomes (Quiroga-Lobos et al., 2014). Furthermore, there is growing emphasis on pedagogical innovation, critical use of technologies, inclusive approaches, and the development of strong teaching competencies (Boyd et al., 2008; Brain et al., 2006; Cisternas, 2011).

These structural and formative demands call into question the quality and relevance of both initial and continuing teacher education (Ávalos & Aylwin, 2007; Cortés & Hirmas, 2016; Córtez & Montecinos, 2016; Ortúzar et al., 2009). From an intercultural and situated perspective, they should not be interpreted as individual deficits but as systemic tensions that disproportionately affect marginalized territories. Recognizing these demands is essential for advancing toward a transformative and contextually relevant teacher education, one that can effectively respond to socio-scientific challenges in multicultural and borderland schools.

1.1.2. Pre-Service Teacher Education for the Teaching of Natural Sciences in Borderland Elementary Education Contexts

Multiple international studies have emphasized that transforming science education requires prioritizing teacher education, particularly at the elementary level (Dias-Lacy & Guirguis, 2017). In Chile, this need is heightened by a projected shortage of 26,273 teachers by 2030 (Elige Educar, 2021), driven by attrition among in-service teachers and a sustained decline in enrollment in teacher education programs, especially in STEM fields: biology and chemistry (−10.2%), physics (−13.8%), and mathematics (−3.2%). This scenario is even more acute in remote regions such as the north, where precarious working conditions intersect with historical inequalities and high levels of sociocultural diversity (Consejo Nacional de Educación [CNED], 2021).

Despite this context, few studies have explored how teachers themselves evaluate their pre-service teacher education (PSTE) in relation to science teaching at the elementary level. Broader research, such as Ruffinelli (2013), has identified weaknesses in key areas, including family engagement, classroom management, attention to student diversity, and science content knowledge, as well as insufficient preparation in literacy, mathematics, and understanding of the national educational system (Gaete et al., 2016; Ruffinelli, 2013).

Recent studies reveal generational differences in perceptions of PSTE. While Soto-Hernández and Díaz Larenas (2018) report high levels of satisfaction among graduates from two Chilean universities, Garay Aguilar and Sillar Velásquez (2018) document a more critical stance among younger teachers, who argue that their training was inadequate to meet classroom demands, particularly during their entry into the profession (Borko et al., 2008; Díaz-Larenas et al., 2015). In contrast, more experienced teachers tend to view their pre-service education favorably, without necessarily linking its limitations to the evolving demands of the current educational system Marín-Cano et al. (2019). Gaete et al. (2016) delve into structural gaps in PSTE, highlighting deficits in classroom management, attention to diversity, creation of supportive learning environments, and formative assessment practices.

Building on this body of work, the present study seeks to identify the specific professional demands expressed by elementary-level natural science teachers in Chile’s northern border region. It aims to understand how they navigate the challenges specific to this territory, how they assess their pre-service education, and what factors either facilitate or hinder a contextually grounded science education in the extreme north region.

1.1.3. Local Environment as a Potential Pedagogical Resource

Research in science education has increasingly emphasized the pedagogical relevance of grounding school science in the local environment and in the sociocultural practices of communities. Approaches that recognize the epistemic value of local knowledge systems and territorial experiences highlight how students’ interactions with their surroundings (biodiversity, climatic phenomena, land-use practices, and ancestral worldviews) can become powerful resources for scientific learning (Aikenhead, 2001; Valladares, 2021). Studies in rural and Indigenous settings in Chile underscore that connecting science teaching with everyday territorial experiences strengthens engagement, promotes inquiry, and supports curricular justice in contexts historically marginalized by centralized policies (Freire-Contreras et al., 2021; Mondaca Rojas, 2018; Urbina & Sepúlveda, 2020). In borderland and rural regions such as Arica and Parinacota, the territory itself thus emerges as an essential pedagogical asset for contextualized and culturally situated science education.

1.1.4. Research Related to Integrated Learning and Interdisciplinary

Related research also highlights the contribution of integrated and interdisciplinary approaches to strengthening science learning in primary education. Work in Chilean contexts shows that linking natural sciences with language, mathematics, arts, or environmental education enables students to develop deeper conceptual understanding and scientific skills, particularly when learning experiences are connected to meaningful, real-world situations (Busquets et al., 2016; Brain et al., 2006; Quiroga-Lobos et al., 2014). Such integration aligns with perspectives that view science teaching as a relational and multidimensional practice shaped through dialog between disciplinary knowledge, students’ lived experiences, and the sociocultural reality of schools (González-Weil et al., 2013; Cisternas, 2011). In rural and multigrade settings, where flexibility and contextual relevance are crucial, interdisciplinary learning becomes a key strategy to articulate scientific content with community practices, local problems, and the cultural experiences of students.

2. Methodology

This study adopts a qualitative, exploratory approach (Yin, 2018) aimed at understanding the professional demands faced by natural science teachers at the elementary education level within a socio and territorial complex context: the border north region of Arica and Parinacota in Chile. Given the nature of the phenomenon (teachers’ perceptions, knowledge, and experiences) an interpretive design was employed. This design acknowledges the agency of participants and values their voices as legitimate sources of pedagogical knowledge (Sandín, 2003; Flick, 2012), aligning with a critical and context-sensitive tradition in educational research.

2.1. Theoretical Framework

The current study is situated within a critical and context-sensitive tradition in educational research, adopting an interpretive design that acknowledges participants’ agency and positions teachers’ voices as authoritative sources of pedagogical knowledge. This approach becomes imperative in making sense of the complexity of science teaching within border contexts.

Theoretically, the research is framed by the concept of situated science education (Honingh et al., 2020) that conceives teaching as a relational, multi-dimensional, and situated phenomenon; this does not consider that pedagogical practice is solely constructed in institutional frameworks but rather through dynamic dialog with students, local knowledge systems, and the territory. On the other hand, this study was guided by criteria of curricular justice and local pertinence, advocating for an education anchored in specific geographical and cultural frameworks and in conversation with emerging socio-territorial realities. This shares an approach with scholars who focus on culturally situated science education that recognizes the epistemic validity of other knowledge systems and provides a venue for dialog between school science and the sociocultural realities of communities (Valladares, 2021; Aikenhead, 2001).

2.2. Participants and Data Collection

The sample (n = 21) was purposive and included teachers from public and publicly subsidized schools, both rural and urban, who participated in a continuing professional development program organized by the Chilean Ministry of Education between July and August 2024. This ensured access to informants with recent experience in science-related professional learning. The study received approval from the Scientific Ethics Committee of the host institution. Anonymity, voluntary participation, and informed consent were ensured for all participants in this study.

Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) were used as the elementary data collection method due to their potential to foster collective dialog and shared meaning-making (Ferrada et al., 2014). A total of 21 teachers participated across four in-person focus groups (each lasting 90–120 min): (1) Novice Teachers (≤5 years of experience); (2) Lower Elementary Level Teachers (Grades 1–4); (3) Upper Elementary Level Teachers (Grades 5–8); and (4) Rural Multigrade Teachers.

Group segmentation was based on two key dimensions: professional experience and educational setting (urban/rural). These dimensions were also considered during analysis to identify patterns and contrasts. This strategy enabled the construction of categories that are responsive to schooling levels, territorial dynamics, and the specific conditions of teaching in borderland contexts. (See Table 1).

Table 1.

Key informant characteristics.

To ensure the validity of the research instrument, the FGD guide was reviewed by a panel of experts in science education. Their evaluation focused on the guide’s relevance, clarity, and alignment with the study’s objectives. Based on their feedback, some questions were revised, and the sequence was adjusted to facilitate a more fluid interaction among participants.

2.3. Data Analysis

All focus group data were fully transcribed verbatim and analyzed using NVivo 14 software, following a hermeneutic–interpretive approach (Miles et al., 2014). In this approach, thematic categories could be drawn out that were rooted in the narratives themselves.

The coding process consisted of an a priori coding framework, as suggested by Flores-Kanter and Medrano (2019), from the main research question and dimensions that emerged from the literature review, namely professional demands, PSTE evaluation, and enabling/hindering factors. This was complemented with an inductive review to identify emergent categories directly arising from the focus group data, making sure that the findings were sensitive to the specific context of the border region.

Meaning units were operationally defined as discursive segments containing complete semantic coherence. The transition from codes to the final categories followed an iterative process of constant comparison, which functioned as a flexible working hypothesis refined dialectically throughout the hermeneutic circle. Finally, it should be clarified that the numerical values presented in the subsequent figures correspond to the frequency of coded references (nodes) in NVivo software, representing discrete units of meaning derived from participants’ discourse

The final analysis was organized according to the three levels that influence science teaching proposed by Fischer et al. (2023): individual processes, classroom dynamics, and systemic conditions. Additionally, the Framework for Good Teaching (MINEDUC, 2021) and the current national pedagogical and disciplinary standards were used as analytical references and to guide critical dialog during the focus groups (See Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Dimensions and categories of analysis. Own elaboration.

3. Results

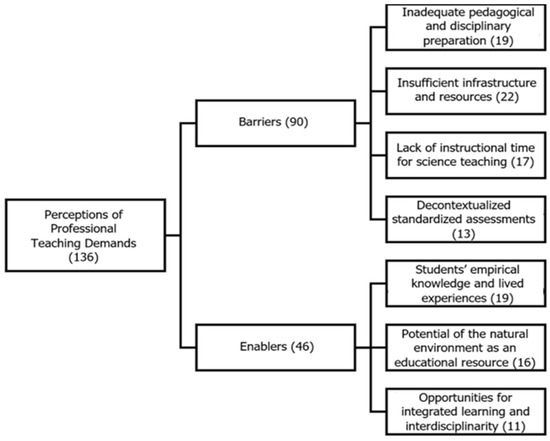

The following sections present findings based on two dimensions related to the professional demands faced by teachers in science instruction: (2) enablers, consisting of three categories, and (1) challenges, consisting of four categories.

3.1. Enablers

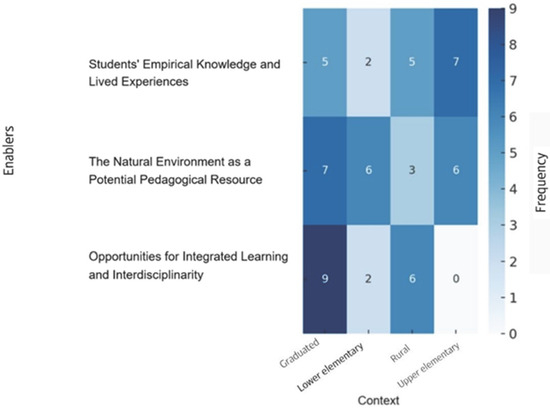

Similarly, teachers’ perceptions and narratives revealed three categories of enabling factors related to how pre-service teacher education (PSTE) supports the professional demands of science teaching (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Enablers for science teaching in borderland contexts. Own elaboration.

3.1.1. Students’ Empirical Knowledge and Lived Experiences

In rural and borderland contexts, students bring valuable cultural diversity and empirical knowledge that significantly enrich science classrooms. Teachers highlighted how experiences related to climate phenomena, agricultural practices, or traditional worldviews not only broaden discussions but also provide unique opportunities to contextualize the curriculum through lived realities. Their accounts confirm that cultural diversity is not a challenge but a key pedagogical resource for meaningful and situated science teaching.

“I have students from different ethnic backgrounds […] they allow me to explore philosophical comparisons, such as deities we refer to as Mother Earth, or Pachamama.”(34 years old, 10 years of teaching experience, upper elementary, public school)

“One of the foundational aspects of our school is the interculturalism lived within the classroom. […] We approach it interdisciplinarity, including science, to address students’ prior knowledge […] even linked to their migratory journeys.”(38 years old, 13 years of teaching experience, upper elementary, public school)

“Students’ prior knowledge, their environment, their biodiversity, enriches the classroom. […] Having them share their experiences with peers is also important, along with the context we are in.”(40 years old, 11 years of teaching experience, upper elementary, public school)

Teacher–student dialog reveals that learners’ lived experiences provide a powerful foundation for planning meaningful learning and developing scientific skills. These experiences, rooted in ancestral wisdom and local knowledge, emerge as essential resources for teaching science and expanding understandings of scientific knowledge. However, their integration in classrooms is still hindered by persistent challenges such as limited resources, lack of teacher training in intercultural approaches, and rigid curricula.

3.1.2. The Natural Environment as a Potential Pedagogical Resource

This category shows how the natural and cultural environment of the north extreme region serves as a high-value educational resource for science teaching. Teachers’ testimonies highlight how this context offers multiple opportunities to align curricular content, such as “living things” and “habitats” in lower elementary level, with local, practical, and meaningful experiences. This link between curriculum and territory transforms abstract concepts into experiential learning, promoting deeper understanding through observation, exploration, and situated inquiry. Framing the territory as a learning space fosters a more relevant, accessible, and culturally meaningful science education.

“The region offers many opportunities for science development. […] In lower elementary levels, units such as living things and habitats allow for studying various phenomena.”(36 years old, 12 years of teaching experience, lower elementary, public school)

“The region’s characteristics are excellent for science teaching. […] We can go to the Azapa Museum, the Sea Museum. […] Everything is accessible for children to experience science in their own context. […] I’m currently working on a project about native flowers and colors of Arica city.”(37 years old, 5 years of teaching experience, recent graduate, subsidized school)

The natural environment also encourages collaborative learning and collective knowledge construction through contextualized scientific discussions. Students’ personal experiences, such as having or not having witnessed certain natural events like rainfall, generate spaces for exchange where perceptions, local knowledge, and scientific concepts are interwoven, enriching the learning process through diverse perspectives.

“The water cycle begins at the coast and ends in the inland villages. […] In the border context, this helps me a lot when teaching science. […] Often, discussions arise because one student says, ‘I’ve never seen rain,’ and another responds, ‘Yes, but rain is like this,’ and through that, they build their own understanding.”(52 years old, 14 years of teaching experience, rural, public school)

“We have the advantage of a beautiful sky. […] Recently, I brought in a telescope, and we created a guide so that students could, on their own, say, ‘Are classes over? Let’s grab the telescope […] as the teacher’s manual says.’ […] So they play but also learn outside the classroom.”(26 years old, 1 year of teaching experience, rural, public school)

The ability to carry out field visits in the surrounding environment without significant bureaucratic hurdles broadens access to hands-on learning. This enables teachers to design contextualized didactic units around topics such as soil analysis, ecological interactions, and astronomical observation, enhancing a place-based and culturally meaningful science education.

3.1.3. Opportunities for Integrated Learning and Interdisciplinarity

The analyzed accounts show that, in their daily practice, teachers promote learning that dynamically and creatively integrates content, skills, and context. These experiences reflect the value of combining natural sciences with subjects such as language, mathematics, arts, and technology, not only in response to curricular demands but as a pedagogical strategy aligned with students’ needs, interests, and realities.

“We work in an integrated way. If we’re studying living things, we explore the environment. […] We start in the school garden. Since we integrate all subjects, we have more time. In math, for example, students counted in sequence while planting seeds.”(55 years old, 13 years of teaching experience, rural, public school)

“In language as well. A girl grabbed a bottle and added stones: ‘This is called an espanta jar” […] We created an illustrated glossary with terms used in planting. That’s how we integrated the subject, and the school coordinator supports this kind of work in the garden.”(42 years of teaching experience, rural, public school)

The connection between language and science emerges as a fertile space for the development of critical thinking and argumentation. Strategies such as teaching opinion structures strengthen reflection in natural sciences, while hands-on activities like working in school gardens allow for the integration of various disciplines through meaningful experiences. As they cultivate and observe, students explore natural and human interactions, apply mathematics to identify patterns and sequences, and bridge theoretical knowledge with practical application.

Similarly, the integration of art and technology into science education enhances the understanding of complex phenomena, such as the Earth’s layers or diverse habitats, through student-constructed models. Art supports the visualization of abstract concepts by fostering creativity and esthetic sensitivity, while technology introduces a contemporary and applied dimension, enabling learners to explore how science is expressed both in their immediate environment and in other regional contexts. This interdisciplinary approach contributes to a richer, more situated, and transformative science education. As one teacher noted:

“I tend to integrate a lot, in order to meet the needs of science using other subjects, such as art or technology. These help me construct the models required in the Natural Sciences curriculum, like the Earth’s layers or habitats in different urban contexts”.(40 years old, 11 years of teaching experience, upper elementary, public school)

A key factor identified is the need for flexibility in integrating subjects and managing time autonomously. This capacity proves fundamental for the effective implementation of interdisciplinary approaches. Open communication with school leadership and the freedom to plan, based on students’ interests and needs are essential conditions for turning these strategies into practice. This highlights that sustained collaboration among teachers and educational community stakeholders is vital to integrating learning in a coherent and meaningful way.

3.2. Challenges

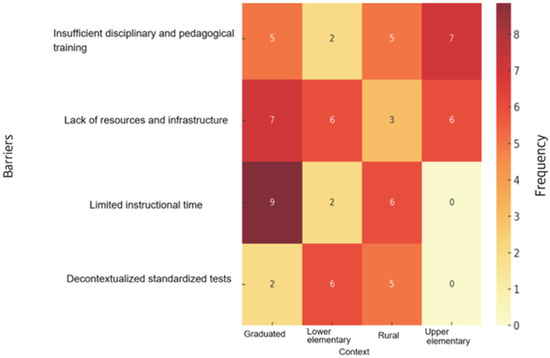

Across the different focus groups (recent graduates, lower elementary, rural, and upper Elementary), four categories of perceived challenges were identified in relation to the professional demands of teaching science (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Challenges to teaching science in borderland contexts. Own elaboration.

3.2.1. Inadequate Pedagogical and Disciplinary Preparation Among In-Service Teachers

This was the most frequently cited category, especially among rural and upper elementary teachers. Participants reported that their PSTE did not provide them with tools to effectively connect disciplinary content with contextually relevant teaching strategies appropriate to their grade levels. In rural areas, this deficit is exacerbated by the challenges of multigrade classrooms and the lack of resources and infrastructure.

“I think we’re still behind. When we went to university, they taught us science […] but not teaching strategies. I feel like […] we all left very unprepared, and what little science knowledge we have […] we’ve learned by our own.”.(62 years old, 22 years’ experience, rural, public school)

“I think my weakness is disciplinary knowledge, which I’ve had to learn independently. I’ve gone directly to the source […] textbooks […] to study and apply them in a way that’s understandable for children.”(35 years old, 11 years’ experience, lower elementary, public school)

“What bothers me is not having all the skills! Because I wasn’t trained in science. So, I rely a lot on the official Ministry’s textbooks […] and I try to make a connection with language […] but I lack the tools.”(36 years old, 12 years’ experience, lower elementary, public school)

According to participants, limited pedagogical and disciplinary preparation hinders their ability to facilitate meaningful learning, particularly in rural and border regions. This perceived inadequacy undermines their professional confidence and complicates the planning of relevant science experiences. While many employ self-directed learning with notable resilience, the urgent need for ongoing professional development was emphasized. The rural context also adds the challenge of teaching multiple subjects and grade levels simultaneously.

3.2.2. Inadequate Infrastructure and Lack of Resources

Teachers highlighted the lack of basic materials and appropriate physical spaces for teaching and learning science. Infrastructure limitations prevent the implementation of active methodologies, the integration of educational technology, and the ability to adequately address student needs in both urban and rural contexts.

“My school can’t take students anywhere. We have 45 students per class. In the school, we only have two trees. We can’t even go outside to look at them.”(37 years old, 5 years’ experience, recent graduate, subsidized school)

“I teach science in a normal classroom with no lab materials at all […] no test tubes, no dyes […], no scales, none of the essential instruments for some science units.”(38 years old, 2 years’ experience, recent graduate, public school)

“There are forgotten areas in schools […] the science lab disappeared during the pandemic. […] This semester we’re just now reopening the science room […] because we lack space and the school lacks adequate structure.”(24 years old, 2 years’ experience, recent graduate, public school)

According to the teacher’s discourse, adverse conditions deepen educational inequality and negatively affect the quality of science instruction, especially in under-resourced settings. Urban schools report overcrowded classrooms and limited outdoor spaces, restricting active methods like inquiry-based learning or project-based approaches. The inability to access natural environments creates a disconnection between students and their surroundings, hindering the development of scientific thinking. Additionally, spaces such as laboratories are often devalued or repurposed. Rural schools face similar challenges with infrastructure and access to resources.

“Due to time and student numbers, I teach two grades in one room: first grade with 20 kids and second grade with 15. Classrooms are small, we have no lab, and the internet is poor.”(72 years old, 42 years’ experience, rural, public school)

“In the highland areas, there are very few children and absolutely no resources. […] In the multigrade school there’s no lab, nothing. So, the teacher has to be inventive to teach science with whatever they can find.”(26 years old, 1 year experience, rural, public school)

In all contexts, these limitations constrain teachers’ ability to implement innovative practices and reduce students’ opportunities to engage in meaningful learning.

3.2.3. Insufficient Instructional Time for Science

A major structural challenge identified is the lack of sufficient instructional time for natural science, which limits the depth of content coverage and hinders the sustained development of scientific competencies throughout the school year.

“There are huge gaps in students’ science education. […] Science hours always get reduced in the curriculum.”(51 years old, 17 years’ experience, rural, public school)

“My school offers very little time to science, two hours a week in lower elementary. […] We used to have three hours and covered the curriculum; now we don’t even reach 50% due to other activities or holidays.”(51 years old, 16 years’ experience, rural, public school)

“The Local Education Service decided to regularize flexible hours. […] They cut science hours in all lower elementary, and in upper elementary, there are only three hours from grades 5 to 8. […] That’s made it hard to cover all the learning objectives and skills.”(55 years old, 13 years’ experience, rural, public school)

The prioritization of subjects such as language, mathematics, or Aymara (local indigenous language) in rural schools’ strains instructional time, displacing science and reducing its instructional time, especially in schools under pressure from standardized testing.

“Very few hours are aimed to work in rural areas, especially because there is also a focus on Aymara language. […] That’s where they cut science hours. […] Here in the semi-rural zone, we have five hours.”(52 years old, 14 years’ experience, rural, public school)

“There’s no way to teach all that content in the time they expect […] but I have to do it because it will be tested. […] Then we get a chart showing the school scored zero in Life Sciences. See what I mean?”(60 years old, 20 years’ experience, rural, public school)

This shortage of instructional hours stems from policy decisions that prioritize certain subjects, relegating science education despite its importance in fostering key competencies for 21st-century citizenship.

3.2.4. Decontextualized Standardized Assessments

Standardized national testing, such as SIMCE, has been widely criticized for its inability to reflect the realities of school communities. The testimonies reveal how these centrally designed assessments pose significant challenges in rural and vulnerable contexts, affecting both teachers and students.

“I’m in a debate because they’re trying to take away two of my four weekly science hours for SIMCE math prep. […] I don’t want to give them up, I need them, on top of all the extracurricular activities.”(40 years old, 11 years’ experience, upper elementary, public school)

Teachers reported a clear tension between student context, curricular goals, and the demands of standardized tests. Preparing for SIMCE and similar exams often results in reduced time for science, in favor of subjects like language and mathematics.

“Standardized tests like the DIA require students to know the entire curriculum while we’re still on unit one or two. […] They don’t reflect school realities. […] Next year it’s SIMCE for History, the year after for science, and that’s how schools get labeled.”(44 years old, 14 years’ experience, upper elementary, public school)

In all contexts, particularly rural schools, standardized tests constrain lesson planning, making it difficult to develop contextually relevant and culturally responsive pedagogical practices.

“In practice, there are contents you have to teach because of the DIA or another standardized test. […] In March there’s the diagnostic, in July the midterm, and at year’s end the final one. […] That comes straight from the Ministry with the required content that as a teacher you should teacher.”(46 years old, 16 years’ experience, upper elementary, public school)

“There’s no rural version of the DIA. It’s a national level test, from Arica to Punta Arenas. […] All schools have to cover the same content. […] In science, language doesn’t matter because it’s so specific.”(43 years old, 15 years’ experience, upper elementary, public school)

The school rhythm, governed by a calendar of diagnostic assessments, imposes a uniform content coverage that does not align with multigrade classroom realities or the constraints of space, time, and resources in rural areas. National-level standardized instruments reinforce decontextualization by ignoring local knowledge, Indigenous languages, infrastructure gaps, and pedagogical diversity.

4. Discussion

The findings of this study provide a significant and original contribution to the field of science education in borderland contexts by centering the voices of elementary school teachers who teach science in the Arica and Parinacota region of northern Chile. In line with Kelly (2023), who advocates for amplifying traditionally marginalized teacher perspectives in educational research, this inquiry demonstrates how professional teaching practice is shaped under conditions of structural vulnerability, curricular tension, and cultural demands unrecognized by the system. As such, this study not only contributes situated empirical evidence but also challenges the homogeneity of teacher education and curricular policies in regions marked by sociocultural and geopolitical complexity.

The results reveal a persistent disconnect between PSTE and the actual conditions of professional practice in public schools located along Chile’s northern border. While prior studies have noted this gap (Cofré et al., 2010; Bastías-Bastías & Iturra-Herrera, 2022), this research gives it critical weight through the embodied accounts of teachers who must confront daily challenges such as multigrade classrooms, resource scarcity, migrant populations, and pressure from standardized testing. Teachers’ narratives sharply problematize the lack of contextual relevance in their training, as well as the absence of tools for addressing cultural diversity, migrant trajectories, and socio-environmental issues that shape pedagogical work in the tri-border zone.

This study also affirms the tensions between the prescribed curriculum and school realities, particularly with regard to science instruction. Although national frameworks such as the Marco para la Buena Enseñanza (Framework for Good Teaching) (MINEDUC, 2021) promote meaningful learning for all students, curricular overload, insufficient instructional time for science, and pressure to meet decontextualized external standards create a restrictive environment that undermines professional autonomy. As noted by Blank (2013) and Fischer et al. (2023), science education in elementary schools is systematically marginalized in favor of subjects considered more essential, such as language and mathematics. This tendency intensifies in rural and underserved areas, where uniform applications of standardized tests fail to reflect local realities or diverse ways of learning.

Theoretically, the findings reinforce the understanding of science teaching as a relational, multidimensional, and situated phenomenon (Honingh et al., 2020). Teachers do not construct their practice solely through institutional frameworks, but also through dialog with students, knowledge of the territory, incorporation of community knowledge, and reflective improvisation in adverse conditions. This interpretation aligns with the work of Valladares (2021), González-Weil et al. (2013), and Aikenhead (2001), who advocate for culturally situated science education that recognizes the epistemic validity of other knowledge systems and fosters dialog between school science and the sociocultural realities of communities.

Practically, this study offers several implications for the redesign of teacher education and education policy. These include strengthening science didactics from an intercultural, relational, and contextually relevant perspective; increasing curricular flexibility to adapt to borderland and rural realities; incorporating authentic teaching experiences in diverse territories into PSTE programs; and recognizing in-service teachers as critical agents capable of transforming their contexts through pedagogical reflection and situated practice. This approach not only contributes to curricular justice (Valladares, 2021) but also to the democratization of scientific knowledge through a postcolonial lens, as proposed by El-Hani and Mortimer (2007) and Baptista and El-Hani (2009).

Despite its interpretative value, this study has limitations. Its qualitative and exploratory design does not allow for national generalization. Furthermore, its territorial focus on a single region limits the ability to capture the diversity of experiences in other borderland or rural areas across the country. However, this limitation is also a key strength of the study, as it sheds light on a historically overlooked region in both Chilean educational policy and research, echoing Freire-Contreras et al. (2021) on the urgency of conducting research from the margins. Future studies could expand the sample to other border or insular regions and incorporate mixed methods to complement the richness of teacher narratives with comparative quantitative data.

In sum, this study not only brings attention to a critical issue in Chilean science education but also offers pathways for rethinking teacher education, curriculum, and policy through a lens of territorial justice, critical interculturality, and pedagogical emancipation. Recognizing the voices of science teachers working in borderland contexts is not merely a symbolic act of recognition, it is an essential condition for constructing an educational project that genuinely reflects the diverse realities of Chilean schools.

5. Limitations of the Work

Despite its interpretive value, this study has certain limitations. Its qualitative and exploratory design does not allow for national generalization of the findings. Furthermore, the territorial focus on a single region limits the study from capturing the diversity across other borderland or rural areas in the country. This limitation is instead one of the key strengths of this research: it gives voice to an always-neglected region, both in Chilean educational policy and in research, as pointed out by Freire-Contreras et al. (2021) referring to the need to conduct research from the margins. The sample may be expanded to other border or insular regions, complementing the rich narratives with quantitative data in future studies.

6. Conclusions

The research gives situated data on the structural and pedagogical tensions that affect natural science teachers in elementary education in the north of Chile due to rurality, multi-grade teaching, migration, and high levels of social vulnerability. When addressing the formative, curricular, and contextual challenges that these teachers face, three main aspects arise: the gap between pre-service training and what they encounter in the classroom; a lack of preparation regarding teaching science in culturally diverse settings; and an urgent need for contextualized, intercultural, and territorially based pedagogical approaches.

The voices of teachers show a transversal and critical diagnosis: pre-service education is insufficient in disciplinary and didactic dimensions and is even more limited when incorporating tools to take up the cultural and social diversity of students. This finding is in tune with previous research that has signaled the persistent disconnection between pre-service teacher education and the demands of professional practice (Cofré et al., 2010; Bastías-Bastías & Iturra-Herrera, 2022). This dissonance underlines how much it is necessary to rethink the design of teacher education, not only by adding relevant content but also by reflective practices, sustained university–school partnership, and mentoring strategies that acknowledge the knowledge of teachers as a starting point for educational transformation.

The second set of structural challenges, which includes insufficient time for science instruction, resonates with the literature showing that elementary science education is systematically left out to make more time for what is perceived as more foundational subjects, such as language and mathematics (Blank, 2013; Fischer et al., 2023). Moreover, the resistance of teachers to decontextualized standardized tests is for locally relevant practices that move toward situated science education called for by scholars (Honingh et al., 2020).

By giving voice to a territory seldom explored in national literature, this investigation contributes to filling a critical gap and joins Kelly’s call from 2023 to amplify the voices of traditionally marginalized teachers in educational research. Far from a deficient perspective, the narratives collected prove that even amidst contexts of structural precariousness, creative and committed pedagogical practices arise that encompass the integration of ancestral knowledge, language, art, environmental observation, and science instruction which reaffirm their emancipatory potential. This commitment to embedding local and cultural knowledge serves to support the conceptual shift toward a culturally situated science education, one that recognizes the epistemic validity of other knowledge systems (Valladares, 2021; Aikenhead, 2001). The findings contribute to the redesign of teacher education and curriculum policies through an intercultural lens of territorial justice.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the conception, development, and writing of each section of this manuscript equally. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Agencia Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo (ANID) (the National Research and Development Agency of Chile) through the Fondecyt project 11241075 Titled: “Teaching Natural Sciences at the Primary Level in a Border Context: Relationships and Tensions Between Professional Practice, Initial Teacher Training, and Self-Efficacy”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Ethic Committee of Universidad de Tarapacá (protocol code C01-2024 on 15 March 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is unavailable due to privacy and ethical restrictions regulated by the nature of the chilean government funding system.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Agencia de Calidad de la Educación [ACE]. (2019). Simce. Available online: https://www.agenciaeducacion.cl/simce/ (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Aikenhead, G. S. (2001). Students’ ease in crossing cultural borders into school science. Science Education, 85(2), 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpaslan, M. M., & Damlı, N. (2022). Relations of in-service teacher job motivation with demographic variables. Online Science Education Journal, 7(1), 28–38. [Google Scholar]

- Ávalos, B., & Aylwin, P. (2007). How young teachers experience their professional work in Chile. Teaching and Teacher Education, 23(4), 515–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, G. C. S., & El-Hani, C. N. (2009). The contribution of ethnobiology to the construction of a dialogue between ways of knowing: A case study in a Brazilian public high school. Science and Education, 18(3), 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barolli, E., Nascimento, W. E., de Oliveira Maia, J., & Villani, A. (2019). Desarrollo profesional de profesores de ciencias: Dimensiones de análisis. Revista Electrónica de Enseñanza de las Ciencias, 18(1), 137–197. [Google Scholar]

- Bastías-Bastías, L. S., & Iturra-Herrera, C. (2022). La formación inicial docente en Chile: Una revisión bibliográfica sobre su implementación y logros. Revista Electrónica Educare, 26(1), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blank, R. K. (2013). Science instructional time is declining in elementary schools: What are the implications for student achievement and closing the gap? Science Education, 97(6), 830–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borko, H., Whitcomb, J., & Byrnes, K. (2008). Genres of research in teacher education. In M. Cochran-Smith, S. Feiman-Nemser, D. J. McIntyre, & K. Demers (Eds.), Handbook of research on teacher education enduring questions in changing contexts (3rd ed., pp. 1017–1045). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, D. B., Lankford, H., Loeb, S., Rockoff, J. E., & Wyckoff, J. (2008). The narrowing gap in New York City teacher qualifications and its implications for student achievement in high-poverty schools. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 27, 793–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brain, K., Reid, I., & Boyes, L. C. (2006). Teachers as mediators between educational policy and practice. Educational Studies, 32(4), 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brumann, S., Ohl, U., & Schulz, J. (2022). Inquiry-based learning on climate change in upper secondary education: A design-based approach. Sustainability, 14(6), 3544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busquets, T., Silva, M., & Larrosa, P. (2016). Reflexiones sobre el aprendizaje de las ciencias naturales: Nuevas aproximaciones y desafíos. Estudios Pedagógicos, 42(especial), 117–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabezas, V., Hochschild, H., & Medeiros, M. P. (2019). Los desafíos pendientes en la ejecución de la nueva política docente: ¿es suficiente con la ley? In A. Carrasco, & L. M. Flores (Eds.), De la reforma a la transformación. Capacidades, innovaciones y regulaciones de la educación chilena. Ediciones UC. [Google Scholar]

- Canabal García, C., Campos, M. C. N., & García, L. M. (2017). La reflexión dialógica en la formación inicial del profesorado: Construyendo un marco conceptual. Perspectiva Educacional, 56(2), 28–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cisternas, T. (2011). La investigación sobre formación docente en Chile: Territorios explorados e inexplorados. Calidad en la Educación, 1(35), 131–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleophas, M. D. G., & Francisco, W. (2018). Metacognição e o ensino e aprendizagem das ciências: Uma revisão sistemática da literatura (RSL). Amazônia, 14(29), 10–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cofré, H., Camacho, J., Galaz, A., Jiménez, J., Santibáñez, D., & Vergara, C. (2010). La educación científica en Chile: Debilidades de la enseñanza y futuros desafíos de la educación de profesores de ciencia. Estudios Pedagógicos, 36(2), 279–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consejo Nacional de Educación [CNED]. (2021). Informe de tendencias de la matrícula de pregrado en la educación superior. Consejo Nacional de Educación [CNED]. [Google Scholar]

- Cortés, I., & Hirmas, C. (2016). Experiencias de innovación educativa en la formación práctica de carreras de pedagogía en Chile. Organización de Estados Iberoamericanos para la Educación, la Ciencia y la Cultura. [Google Scholar]

- Córtez, M., & Montecinos, C. (2016). Transitando desde la observación a la acción pedagógica en la práctica inicial: Aprender a enseñar con foco en el aprendizaje del alumnado. Estudios Pedagógicos, 42(4), 49–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CPEIP. (2017). Estándares pedagógicos y disciplinarios para la formación inicial docente. Versión preliminar. Centro de Perfeccionamiento, Experimentación e Investigaciones Pedagógicas, CPEIP. Área de Formación Inicial de Educadoras y Docentes. Ministerio de Educación.

- Declaración de Budapest. (1999). Declaración sobre la ciencia y el uso del saber científico y programa en pro de la ciencia: Marco general de acción. Unesco. [Google Scholar]

- De Pro Bueno, A. J., De Pro Chereguini, C., & Doménech, J. L. (2022). Cinco problemas en la formación de maestros y maestras para enseñar ciencias en Educación Primaria. Revista Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado, 97(36), 185–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias-Lacy, S. L., & Guirguis, R. (2017). Challenges for new teachers and ways of coping with them. Journal of Education and Learning, 6(3), 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Larenas, C. H., Solar Rodríguez, M. I., Soto Hernández, V., & Conejeros Del Solar, M. (2015). Formación docente en Chile: Percepciones de profesores del sistema escolar y docentes universitarios. Civilizar Ciencias Sociales y Humanas, 15(28), 229–246. [Google Scholar]

- El-Hani, C., & Mortimer, E. (2007). Multicultural education, pragmatism, and the goals of science teaching. Cultural Study of Science Education, 2, 657–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elige Educar. (2021). Déficit docente en Chile: Actualización 2021. Elige Educar. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrada, D., Villena, A., Catriquir, D., Pozo, G., Turra, O., Schilling, C., & Del Pino, M. (2014). Investigación dialógica- kishu kimkelay ta Che en educación. Revista de Estudios y Experiencias en Educación, 13(26), 33–50. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrada, D., Villena, A., & Del Pino, M. (2018). ¿Hay que formar a los docentes en políticas educativas? Cadernos De Pesquisa, 48(167), 254–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, H. E., Boone, W. J., & Neumann, K. (2023). Quantitative research designs and approaches. In N. G. Lederman, D. L. Zeidler, & J. S. Lederman (Eds.), Handbook of research on science education (Vol. 3, pp. 28–59). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Flick, U. (2012). Introducción a la investigación cualitativa (T. del Amo, Trans.). Ediciones Morata. [Google Scholar]

- Flores-Kanter, P. E., & Medrano, L. A. (2019). Núcleo básico en el análisis de datos cualitativos: Pasos, técnicas de identificación de temas y formas de presentación de resultados. Interdisciplinaria, 36(2), 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire-Contreras, P. A., Llanquín-Yaupi, G. N., Neira-Toledo, V. E., Queupumil-Huaiquinao, E. N., Riquelme-Hueichaleo, L. A., & Arias-Ortega, K. (2021). Prácticas pedagógicas en aula multigrado: Principales desafíos socioeducativos en chile. Cadernos De Pesquisa, 51, e07046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaete, A., Gómez, V., & Cascopé, M. (2016). ¿Qué le piden los profesores a la formación inicial docente en Chile? Temas De La Agenda Pública, 11(86), 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Garay Aguilar, M., & Sillar Velásquez, M. (2018). Evaluación sobre los procesos formativos de los docentes de la región de Magallanes (Chile). Sophia Austral, 1(21), 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- González-Weil, C., Cortez Muñoz, M., Pérez Flores, J. L., Bravo González, P., & Ibaceta Guerra, Y. (2013). Construyendo dominios de encuentro para problematizar acerca de las prácticas pedagógicas de profesores secundarios de Ciencias: Incorporando el modelo de Investigación-Acción como plan de formación continua. Estudios Pedagógicos, 39(2), 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gómez Chaparro, S., & Sepúlveda, R. (2022). Inclusión de estudiantes migrantes en una escuela chilena: Desafíos para las prácticas del liderazgo escolar. Psicoperspectivas, 21(1), 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honingh, M., Ruiter, M., & Van Thiel, S. (2020). Are school boards and educational quality related? Results of an international literature review. Educational Review, 72(2), 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iturralde, M., Mariel Bravo, B., & Flores, A. (2017). Agenda actual en investigación en didáctica de las Ciencias Naturales en América Latina y el Caribe. Revista Electrónica De Investigación Educativa, 19(3), 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kelly, G. J. (2023). Qualitative research as culture and practice. In N. G. Lederman, D. L. Zeidler, & J. S. Lederman (Eds.), Handbook of research on science education (Vol. III, pp. 60–86). Routledge. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Kleickmann, T., Tröbst, S., Jonen, A., Vehmeyer, J., & Möller, K. (2016). The effects of expert scaffolding in elementary science professional development on teachers’ beliefs and motivations, instructional practices, and student achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 108(1), 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín-Cano, M. L., Parra-Bernal, L. R., Burgos-Laitón, S. B., & Gutiérrez-Giraldo, M. M. (2019). La práctica reflexiva del profesor y la relación con el desarrollo profesional en el contexto de la educación superior. Revista Latinoamericana de Estudios Educativos, 15(1), 154–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzabal Blancafort, A., & Merino Rubilar, C. (2021). Investigación en educación científica en Chile: ¿Dónde estamos y hacia dónde vamos? Ediciones Universitarias de Valparaíso. [Google Scholar]

- Maturana, J., & Cáceres, P. (2017). Construcción de concepciones epistemológicas y pedagógicas en profesores secundarios de ciencia. Enseñanza de las ciencias: Revista de investigación y experiencias didácticas, (N° Extra 0), 2781–2786. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldaña, J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Educación [MINEDUC]. (2021). Marco para la Buena Enseñanza. MINEDUC.

- Ministerio de Educación [MINEDUC]. (2023). Plan de reactivación educativa 2023. MINEDUC.

- Mondaca Rojas, C. E. (2018). Educación y migración transfronteriza en el norte de Chile: Procesos de inclusión y exclusión de estudiantes migrantes peruanos y bolivianos en las escuelas de la región de Arica y Parinacota [Ph.D. thesis, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona]. [Google Scholar]

- Organización para la Cooperación y el Desarrollo Económico [OECD]. (2019). TALIS 2018 results (Vol. I). OECD EBooks. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organización para la Cooperación y el Desarrollo Económico [OECD]. (2023). PISA 2025 science framework (Second draft). OECD. [Google Scholar]

- Ortúzar, M. S., Flores, C., Milesi, C., & Cox, C. (2009). Aspectos de la formación inicial docente y su influencia en el rendimiento académico de los alumnos. In Camino al Bicentenario: Propuestas para Chile (pp. 155–186). Centro de Políticas Públicas, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile. [Google Scholar]

- Quintanilla, M., & Adúriz-Bravo, A. (2022). Enseñanza de las ciencias para una nueva cultura docente: Desafíos y oportunidades. Ediciones UC. [Google Scholar]

- Quiroga-Lobos, M., Arredondo-González, E., Cafena, D., & Merino-Rubilar, C. (2014). Desarrollo de competencias científicas en las primeras edades: El Explora Conicyt de Chile. Educación y Educadores, 17(2), 237–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruffinelli, A. (2013). La calidad de la formación inicial docente en Chile: La perspectiva de los profesores principiantes. Calidad en la Educación, (39), 117–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandín, M. P. (2003). Investigación cualitativa en educacion. Fundamentos y tradiciones. McGraw-Hill Interamericana de España. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez Espinosa, E., & Norambuena Carrasco, C. (2019). Formación inicial docente y espacios fronterizos. Profesores en aulas culturalmente diversas. Región de Arica y Parinacota. Estudios Pedagógicos, 45(2), 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Hernández, V., & Díaz Larenas, C. H. (2018). Formación inicial docente en una universidad. Praxis & Saber, 9(20), 190–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. (2022). Educación en América Latina y el Caribe en el segundo año de la COVID-19. UNESCO Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Urbina, A. A., & Sepúlveda, P. Z. (2020). Niñez aymara a ojos de quienes les educan: Percepciones sobre multiculturalidad en escuelas de Arica, Chile. Utopía y Praxis Latinoamericana, 25(13), 159–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valladares, L. (2021). Scientific literacy and social transformation. Science & Education, 30(3), 557–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velásquez Semper, F. (2022). La interculturalidad en las aulas de ciencias en Chile: Prácticas y perspectivas de profesores de ciencias naturales y biología. Universidade do Minho. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/1822/77426 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Yin, R. K. (2018). Case study research and applications: Design and methods (6th ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).