1. Introduction

The rapid advancement of technology has transformed many sectors, including education. One of the most promising innovations in this field is Virtual Reality (VR)—a computer-generated technology that creates fully immersive, three-dimensional environments. By wearing a head-mounted display (commonly called a VR headset) and sometimes using hand controllers, users feel as if they are physically present inside a simulated world, where they can look around in any direction, move freely, and interact with virtual objects and characters in real time. This sense of “being there”—known as presence—is what distinguishes VR from traditional video or screen-based learning tools. Importantly, VR serves not merely as a replacement for conventional educational methods; instead, it possesses unique capabilities that can augment the learning experience through the simulation of complex scenarios and the promotion of active engagement among students (

Crogman et al., 2025;

Yang et al., 2024).

In the realm of higher education, there is a pressing need for more engaging and effective approaches to teaching public speaking, a skill essential for success across a multitude of disciplines. Academic presentations serve as critical platforms for demonstrating comprehension, persuasion, and critical thinking. However, many students face substantial anxiety when required to present in front of peers, which often hinders their ability to articulate thoughts and ideas clearly. Research indicates that a significant proportion of individuals experience anxiety related to public speaking, which can impede performance and negatively affect learning outcomes (

Mardon et al., 2025;

Forsler, 2025;

Oje et al., 2025;

Valls-Ratés et al., 2024).

VR offers a promising solution to these challenges by providing a safe and controlled environment where students can practice their public speaking skills without the fear of real-world repercussions. This technology allows for the simulation of diverse scenarios, ranging from addressing a small group to presenting in a packed auditorium, thus enabling students to acclimatize to varying audience dynamics and distractions. By fostering an experiential learning approach, VR engages students in situational practice (

Bartyzel et al., 2025;

Laine et al., 2025;

Oliveira et al., 2024).

The rationale for creating a VR environment for oral presentations acknowledges that enhancing public speaking skills requires not only practice but also support in managing anxiety. Traditional instructional methods often fail to deliver the immediate feedback and authentic scenarios that students need to build confidence and skill. This gap in available educational tools signifies an opportunity to integrate VR technologies into speech education, cultivating a unique learning experience that targets emotional and cognitive dynamics associated with public presentations (

Laine et al., 2025;

Graham et al., 2025;

Tan et al., 2025;

Macdonald, 2024;

Valls-Ratés et al., 2024).

Numerous studies have underscored the effectiveness of VR across various domains, particularly its application in experiential learning frameworks. Research has shown that VR enhances student interaction, improves understanding, and promotes active engagement through realistic simulations (

Bartyzel et al., 2025;

Laine et al., 2025;

Graham et al., 2025;

Tan et al., 2025;

Macdonald, 2024). VR acts as a bridge between theoretical knowledge and practical application, allowing learners to immerse themselves in scenarios that are relevant to their academic endeavors and future professional careers. The literature further suggests that the value of VR in education transcends mere replication of real-world conditions, leveraging the benefits of immersion to create meaningful learning experiences. Given the compelling evidence supporting VR’s potential to enhance learning outcomes, it becomes imperative to contextualize its deployment towards achieving specific educational goals (

Mardon et al., 2025;

Forsler, 2025;

Oje et al., 2025).

Rationale for Creating a VR Environment for Oral Presentations

Despite the growing body of research demonstrating that VR exposure can reduce public speaking anxiety and improve communication performance (e.g.,

Oliveira et al., 2024;

Valls-Ratés et al., 2024), several important gaps remain. First, many existing VR training systems have been developed and tested in laboratory settings with generic audiences or highly stylized environments that differ markedly from the specific spaces in which students actually present (e.g., their own university auditoriums). Second, relatively few studies have systematically examined how deliberate graphical-design choices—particularly the degree of realism and the conscious avoidance of the uncanny valley—affect both immersion and emotional comfort during training. Third, there is limited evidence on the effectiveness of low-cost, standalone headsets (such as the widely available Meta Quest 2) when deployed in real university curricula rather than controlled experiments. Finally, although self-reported reductions in anxiety are frequently documented, the field still lacks consensus on how VR practice translates into measurable improvements in concrete speaking behaviors (fluency, clarity, and observable anxiety markers) within ecologically valid educational contexts.

The present exploratory study therefore addresses the following overarching research question: To what extent can a custom-designed, semi-realistic VR environment—modeled on students’ actual university auditorium and delivered via an accessible standalone headset—improve oral presentation skills and reduce public speaking anxiety in a real higher-education setting?

We hypothesized that a single guided VR session incorporating progressive exposure to realistic distractions would yield (a) statistically significant increases in speaking fluency and clarity, (b) significant reductions in observable and self-reported anxiety, and (c) high levels of user satisfaction and perceived usefulness. To achieve these outcomes, the virtual auditorium was deliberately rendered in a semi-realistic style that prioritizes recognizability and emotional comfort over photorealism, thereby avoiding the uncanny valley effect (

Mori, 1970;

Kätsyri et al., 2015;

Kang et al., 2025) while preserving ecological validity. Preliminary participant feedback confirmed that the environment felt familiar and non-disturbing, supporting the effectiveness of this design choice (

Kaplan-Rakowski & Gruber, 2023;

Dudley et al., 2023;

Yang et al., 2024).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

This exploratory study employed a quasi-experimental design conducted over one academic semester at the University of Bío-Bío in Chillán, Chile. A quasi-experimental design was chosen because random assignment of participants to distinct treatment and control groups was not feasible within the existing curriculum of the Speech and Language Therapy program. Instead, the study adopted a single-group, pre-test/post-test (one-group pretest-posttest) design (

Cook et al., 2002), in which all participants received the same VR-based intervention after baseline measurements of oral fluency, clarity, and anxiety were collected one week prior to the VR session. Post-intervention measures were taken one week after the VR training using identical protocols. This approach allowed us to assess within-subject changes attributable to the intervention while maintaining ecological validity and curricular integration. Although quasi-experimental designs are more susceptible to certain internal validity threats (e.g., history, maturation, or testing effects) than true randomized experiments, the short time interval between measurements and the absence of concurrent external events mitigated these risks in the present context (

Thyer, 2012).

2.2. Participants and Sample

The study included 40 second- and third-year students enrolled in the Speech and Language Therapy program. Participants, aged 19 to 21, were selected to create a cohesive and homogeneous sample, ensuring a balance of genders. A cohesive and homogeneous sample was intentionally formed by recruiting students from the same academic program (Speech and Language Therapy), the same year levels (second- and third-year), and the same university campus. This strategy ensured that all participants shared highly similar educational backgrounds, prior exposure to public speaking tasks (as part of their clinical training), familiarity with the physical auditorium replicated in the VR environment, and comparable motivational contexts. Such homogeneity strengthens the internal validity of an exploratory study by reducing extraneous variability arising from differences in discipline-specific communication demands, prior presentation experience, or institutional culture, while still allowing the examination of gender-balanced responses within a clearly defined population.

Inclusion criteria required that participants be university students able to wear glasses or hearing aids but without pre-existing speech or voice disorders, cardiovascular diseases, balance disorders, depression, neurological disorders, or high levels of academic stress. Exclusion criteria aimed to eliminate potential confounding variables that might skew results, ensuring the integrity of the study.

2.3. Variables Analyzed

The study assessed several key variables, including oral fluency, clarity of speech, and anxiety levels during presentations. Oral fluency was measured as the number of words spoken per minute (WPM), clarity was rated on a scale from 1 to 10, and anxiety was evaluated using a similar 10-point scale, where higher scores indicated greater anxiety. These variables are critical for understanding the effectiveness of VR as a training tool and represent a novel approach to measuring public speaking capabilities among students.

2.4. Instruments, Techniques, and Procedures

The VR environment was developed using the Unity game engine, which is particularly effective for creating realistic and immersive scenarios. In this instance, the platform was specifically designed to simulate oral presentations, presenting challenges related to managing various distracting situations encountered by participants. The VR application featured multiple distracting situations and audience dynamics, enabling participants to engage in a range of public speaking scenarios that would be difficult to replicate in traditional educational settings.

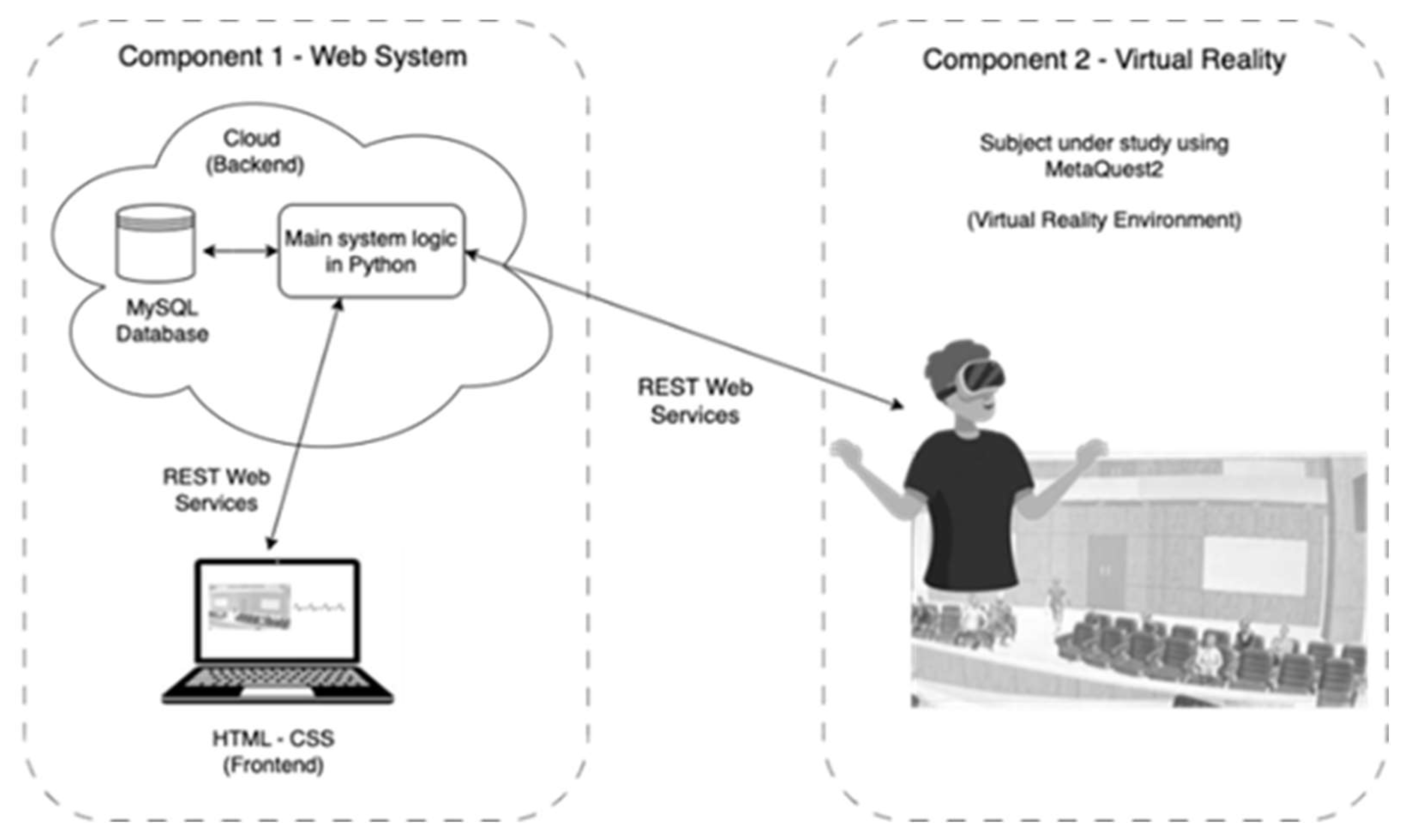

Prior to the experimental phase, a remote platform was established to manage data storage (see

Figure 1), generate VR scenarios, and log results. This platform consisted of two main components: a web interface with backend and frontend systems that interacted via REST services for flexibility and scalability. The backend was implemented using MySQL 8.0.33, and the server-side logic was developed in PHP 8.1. The frontend utilized HTML5, CSS3, and Vanilla JavaScript together with Bootstrap 5.2 for responsive user interface design. The VR application itself was developed in Unity 2022.3.10f1 (LTS) using the XR Interaction Toolkit 2.4.3 and the Oculus Integration package version 57.0. It was built for the standalone Android platform and deployed on the Meta Quest 2 running Quest system software version 60.0.0 (at the time of data collection, October–December 2024). Builds were compiled targeting OpenGLES3 graphics API with 72 Hz refresh rate locked to ensure consistent performance across devices. Both audio and visual data were captured natively within Unity and uploaded in real time to the remote server. This fully specified configuration ensured reproducibility and allowed precise tracking of participant performance under controlled yet realistic conditions (

Chen et al., 2024). This device was selected for several practical and methodological reasons: (1) at the time of the study (2023–2024), Quest 2 remained the most widely available and cost-effective standalone VR platform in our university context, ensuring accessibility for all participants without requiring additional PC hardware; (2) its widespread adoption in prior educational VR research (e.g.,

Kaplan-Rakowski & Gruber, 2023) facilitates comparability with existing studies on public speaking anxiety and VR training; and (3) its technical specifications (1832 × 1920 pixels per eye, 90–120 Hz refresh rate, and inside-out tracking) were fully sufficient for the semi-realistic visual style employed, while its low persistence and relatively light weight helped minimize cybersickness during extended presentation practice sessions. Although newer headsets offer incremental improvements, Quest 2 provided an optimal balance of performance, affordability, and ecological validity for the present educational setting.

2.5. Scenario Design, User Experience Adjustments and Data Collection Framework

We constructed one presentation scenario inspired by the primary auditorium at the university where the participants study (see

Figure 1). The virtual environment was intentionally designed in a semi-realistic graphical style that prioritizes recognizability and emotional comfort over photorealism. Avoiding hyper-realistic avatars and rendering prevented the uncanny valley effect (

Mori, 1970;

Kätsyri et al., 2015;

Kang et al., 2025), maximizing immersion and reducing potential discomfort or anxiety that could disrupt training. This scenario included distracting elements such as audience conversations, inappropriate entries into the auditorium, and verbal interruptions. Additionally, ambient noises, including fire sirens, phone calls, and audience coughing, were integrated to enhance realism. Research indicates that exposure to various distractions can significantly influence performance outcomes and engagement in educational contexts (

Mardon et al., 2025;

Forsler, 2025;

Oje et al., 2025).

Recognizing that students often experience anxiety when presenting in front of peers, we incorporated features designed to alleviate pre-presentation stress. Before engaging in the main presentation tasks, all participants entered a tranquil virtual environment—a Japanese garden—augmented with soothing music and nature sounds for two minutes. This approach allowed participants to acclimate to the VR setting and reduce initial anxiety levels (

Laine et al., 2025;

Graham et al., 2025;

Tan et al., 2025;

Bachmann et al., 2023).

The platform was designed to capture participants’ presentations, recording audio and visual data for later evaluation of speech fluency and anxiety levels while performing in VR scenarios. The use of real-time feedback mechanisms is crucial, as it facilitates reflection and enhances the learning process. Encouraging students to reflect post-presentation significantly contributes to their development and retention of public speaking skills (

Kaplan-Rakowski & Gruber, 2023;

Mendzheritskaya et al., 2024).

2.6. Procedure

Initially, the research team convened with eligible students from the Speech and Language Therapy program to explain the goals, procedures, and benefits of the study. Interested students signed a consent form and were provided with a standardized text titled “The Influence of Social Networks on University Life” to prepare for their oral presentations. Following this, a personal interview was conducted to assess participants’ eligibility, which involved discussions of their medical histories and the completion of an Academic Stress Guideline questionnaire. This screening ensured that only individuals without conditions affecting the study’s outcomes were included. Participants also signed informed consent forms emphasizing confidentiality regarding their involvement in the research.

Evaluations were conducted in a controlled VR lab setting (see

Figure 2). The experimental phase initiated with the registration of each participant’s ID in the web platform. Participants subsequently interacted with the VR system for approximately 10 min, during which they received instructions on operating the VR controls and familiarized themselves with the virtual tools. Once acclimatized, students entered the virtual auditorium to present their prepared texts. At the commencement of the presentation, participants received instructions aimed at anxiety management. If a participant exhibited prolonged silence, evaluators provided feedback to encourage further elaboration on their points.

To address the well-documented risk of cybersickness, which is particularly relevant when using Meta Quest 2 headsets, a specific safety protocol was implemented. During VR exposure, a member of the research team was present at all times to visually observe participants for early signs of nausea, disorientation, eye discomfort or balance disturbances, and to maintain verbal contact by asking standardized well-being check questions such as ‘Are you feeling okay?’ at three-minute intervals. Participants were explicitly instructed to report any discomfort immediately and informed that they could remove the headset at any time without penalty. Participants were provided with a comfortable, armrest-equipped chair, and sessions were limited to a maximum of 20 min of continuous immersion. In the event of symptoms occurring, a gradual interruption protocol was prepared (immediate removal of the headset and recovery in a seated position). No participant experienced symptoms of cybersickness severe enough to require interruption of the session.

2.7. Survey Data

Following the completion of their presentations, students were required to complete a structured satisfaction survey comprising five dichotomous (‘yes/no’) questions designed to capture their overall experience. The purpose of this survey was to assess various dimensions of their engagement in the VR environment, including enjoyment, ease of navigation, perceived realism, quality of guidance provided, and willingness to recommend the platform to peers. The diverse aspects of the survey were intentionally designed to yield a comprehensive understanding of student perceptions and satisfaction levels concerning the VR tool. The collected data underwent thorough analysis to extract insights regarding the effectiveness of the VR environment and identify potential improvements for future iterations. Adopting a participatory approach that incorporates student feedback into the development process is vital for creating an educational platform responsive to learners’ needs.

In addition to the satisfaction survey conducted after the VR experience, students were assessed on three speech metrics one week prior to and one week following the VR intervention. Oral Fluency was measured by the number of words spoken per minute (WPM) during presentations, indicating their ability to convey information clearly and continuously. Speech Clarity was rated on a scale of 1 to 10, where a higher score represented superior clarity and articulation. Level of Anxiety in Speech was evaluated using a scale of 1 to 10 based on the presence of hesitations, with higher scores indicating increased anxiety during public speaking. Participants discussed topics related to speech and swallowing disorders, ensuring relevance to their field of study. The evaluations aimed to establish baseline metrics for comparison against post-intervention performance, providing insights into the VR experience’s effectiveness in enhancing fluency, clarity, and anxiety management (

Valls-Ratés et al., 2024).

2.8. Ethics Considerations

To ensure the participants’ understanding of the nature of the study and its implications, as well as their voluntary participation, they read and signed an informed consent form approved by the scientific ethics committee of the sponsoring university (code cecubb2024/1).

2.9. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics provided a comprehensive overview of participant demographics, enabling the identification of trends within the sample population. To investigate potential gender differences in survey responses, chi-square tests were applied, offering insights into how male and female participants engaged with the VR experience. Paired samples t-tests were employed to assess significant changes in performance metrics, specifically targeting improvements linked to VR training in oral presentation skills. Furthermore, regression analyses were utilized to determine key predictors of fluency enhancement, analyzing how various factors, such as initial anxiety levels and clarity ratings, influenced overall performance outcomes.

3. Results

Initially, the study involved 40 participants, all of whom were second- and third-year students enrolled in the Speech and Language Therapy program. The demographic characteristics of these participants are summarized in

Table 1.

Table 2 presents the survey results focusing on participants’ experiences with the VR environment. The survey responses are aggregated by gender, offering a comprehensive overview of how male and female participants reacted to each question. Overall, the findings suggest that the VR platform is not only enjoyable but also engaging and effective in creating realistic learning experiences for public speaking. Participants’ comments affirm the platform’s ability to prepare them for real-world speaking situations while highlighting areas for potential improvement and enhanced clarity in guidance.

Additionally, paired-samples t-tests conducted one week after the single VR training session revealed large and highly significant improvements across all three speech performance metrics (see

Table 3). Speaking fluency increased from a pre-training mean of 85.2 words per minute (±15.4 SD) to 102.3 words per minute (±17.8 SD), yielding a mean gain of 17.1 words per minute (t(39) = 8.41,

p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 1.33). This substantial improvement indicates that participants spoke noticeably faster and with fewer hesitations, pauses, and filler words following the VR intervention.

Perceived clarity, rated by trained evaluators on a 1–10 scale, rose from 5.5 (±1.9 SD) to 7.8 (±1.5 SD) (t(39) = 9.67, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 1.53). Independent raters consistently described post-training presentations as more articulate, better organized, and delivered with greater vocal confidence and projection.

Finally, self-reported and observed anxiety during presentations decreased markedly from 7.0 (±1.6 SD) to 4.3 (±1.8 SD), representing a reduction of 2.7 points on the 10-point scale (t(39) = −10.12, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 1.60). This shift moved participants from a level typically characterized as moderate-to-high anxiety to one reflecting only mild or low apprehension, with large effect sizes observed across all three measures.

To assess the relationships between the survey results and performance metrics, chi-square tests and regression analyses were conducted (

Table 4). A substantial association was identified between participants’ perceived ease of navigation within the VR environment and their overall enjoyment of the experience. The Chi-Square statistic was 9.14 with a significance level of

p = 0.003, suggesting that students who found the VR system enjoyable were significantly more likely to report comfort in navigating it. Additionally, regression analysis revealed that pre-VR anxiety levels and post-VR clarity ratings were significant predictors of fluency during presentations. The resulting model produced an R

2 value of 0.67 with a

p-value of less than 0.001, thus supporting the hypothesis that immersive practice scenarios can effectively reduce anxiety and enhance performance in speaking skills.

4. Discussion

The outcomes of this exploratory study demonstrate that the implementation of a VR environment significantly enhances students’ oral presentation skills. The data indicate that participants not only enjoyed their experience but also expressed increased confidence in their public speaking abilities. Specifically, the paired samples t-tests showcased notable improvements in fluency, clarity, and a marked decrease in anxiety levels after engaging in VR training. These findings align with the fundamental premise that immersive learning environments can effectively reduce the fear and anxiety associated with public speaking, allowing participants to focus on honing their communication skills without real-world repercussions.

The positive feedback garnered from the satisfaction surveys suggests that students valued the engaging nature of the VR platform. As evidenced by the high recommendation rates, students recognized the platform’s potential to prepare them for authentic speaking scenarios. Reinforcing this notion, previous research suggests that immersive environments foster deeper cognitive engagement and emotional safety—key factors in developing effective communication skills (

Tan et al., 2025;

Macdonald, 2024;

Patterson et al., 2025;

Kryston et al., 2021;

Chen et al., 2024).

When contextualizing these results within the broader landscape of educational research, our findings resonate with a growing body of literature advocating for the incorporation of VR in educational settings. Prior studies have highlighted similar benefits derived from VR applications; for instance, Patterson et al. reported significant improvements in students’ presentation skills and confidence levels following VR training, underscoring the medium’s ability to facilitate experiential learning (

Patterson et al., 2025).

Moreover, studies focusing on VR and anxiety management suggest that immersing students in controlled VR scenarios allows them to practice public speaking in real-time, ultimately reducing their apprehension and enhancing their speaking performance (

Satake et al., 2023). In a meta-analysis of VR applications in education,

Graham et al. (

2025) found that the inclusion of immersive simulations not only increased student engagement but also yielded substantial learning outcomes, reinforcing our findings (

Graham et al., 2025).

While our results align with the existing literature on VR and presentation skill development, they also contribute to a niche area of research that emphasizes immersive learning experiences in high-stress situations, such as public speaking. However, the exact mechanisms by which VR fosters learner confidence may vary, suggesting further exploration is necessary (

Shirtcliff et al., 2024;

Ali & Hoque, 2017).

The implications of this research extend beyond the current findings. As we look ahead, there are several projections for future studies that stem from our work. One potential avenue is the refinement of the VR platform based on participant feedback, allowing developers to enhance user experiences by integrating additional features, such as customizable scenarios and real-time analytics. Such improvements could lead to even more significant gains in students’ oral presentation skills. (

Kunz et al., 2025;

Ali & Hoque, 2017;

Yang et al., 2024).

Additionally, further research is warranted to examine the long-term impacts of immersive VR training on students’ public speaking abilities. Exploring the retention of skills acquired through VR can reveal valuable insights regarding the efficacy of immersive learning as a pedagogical approach. Longitudinal studies could track graduates as they apply their skills in real-world settings, providing a more comprehensive assessment of VR’s role in enhancing students’ communication capabilities. This aligns with previous recommendations to conduct longitudinal investigations in immersive learning (

Graham et al., 2025;

Macdonald, 2024;

Satake et al., 2023;

Yang et al., 2024).

Furthermore, diversifying the participant pool by including students from various disciplines could help assess the versatility of the VR platform, allowing researchers to determine whether the benefits observed are discipline-specific or generalizable across educational contexts. As such, it may be beneficial to investigate how different types of distractions and audience engagement models affect students’ performances in public speaking.

Although this study provides valuable preliminary insights into the use of VR for public speaking training, its exploratory nature and modest sample size (N = 40) constrain the generalizability of the findings. These limitations are typical of pilot investigations and underscore the need to interpret the results with appropriate caution. Future research should employ larger, more diverse samples across multiple institutions to confirm the observed effects and strengthen the evidence base for VR-based interventions in higher education. Framing the present work as an exploratory pilot study thus aligns with its scope and helps prevent overinterpretation while laying a foundation for subsequent confirmatory studies.

Second, the research was conducted within a singular academic program—Speech and Language Therapy—potentially introducing bias based on the specific training and experiences of students in that program. Consequently, the results may not fully reflect the perspectives or performance improvements of students in other fields of study.

Third, variations in students’ prior exposure to public speaking or VR technology could impact results, as those with previous experience may demonstrate different levels of comfort and skill improvement compared to novices. As highlighted by Graham et al., assessing participants’ baseline skills and experiences is essential for interpreting the effects of interventions accurately, indicating that more comprehensive pre-training assessments could enhance future studies (

Graham et al., 2025).

A further limitation stems from the exclusive use of self-report measures (e.g., perceived anxiety, confidence, and enjoyment ratings) to evaluate training outcomes. Although these subjective assessments capture important affective dimensions of public speaking anxiety, they do not provide objective evidence of improvements in actual presentation performance. Key behavioral indicators—such as eye contact duration, posture stability, vocal prosody, articulation clarity, and pausing patterns—were not recorded or analyzed in the current study. Incorporating such objective metrics in future iterations would yield more robust and verifiable data on skill acquisition, thereby complementing self-reported experiences and strengthening the overall evaluation of the VR intervention’s effectiveness (

Stein et al., 2019).

Finally, while the study provided promising short-term outcomes related to VR use, further exploration into the long-term efficacy of VR training on public speaking skills remains essential. Encouragingly, the existing literature notes the potential for sustained learning benefits, but additional longitudinal studies are required to validate these hypotheses.

5. Conclusions

This exploratory study provides robust evidence that a single, institution-specific VR training session—delivered through an affordable standalone headset and grounded in a familiar, semi-realistic virtual auditorium—can produce large, statistically significant, and practically meaningful improvements in university students’ oral presentation skills. One week after the intervention, participants demonstrated a 20% increase in speaking fluency (from 85.2 to 102.3 words per minute), a 2.3-point gain in rated clarity, and a 2.7-point reduction in anxiety (from moderate–high to mild levels), with all changes yielding large effect sizes (Cohen’s d = 1.33–1.60). These gains occurred alongside high user satisfaction (85% enjoyment and recommendation rates) and no incidence of cybersickness, confirming that the deliberately chosen semi-realistic graphical style successfully balanced ecological validity, immersion, and emotional comfort.

The results extend previous laboratory-based research by showing that VR training is not only feasible but highly effective when embedded in real curricular contexts, using widely available hardware and environments that mirror students’ everyday academic spaces. The particularly strong anxiety reductions observed among participants with higher baseline apprehension further suggest that VR may be especially valuable for those who stand to benefit most from repeated, low-stakes exposure.

From a pedagogical perspective, these findings position VR as a powerful complement—or even alternative—to traditional public speaking instruction, particularly for skills that are difficult to rehearse safely in front of live audiences. The combination of controlled distractions, immediate immersion in a recognizable setting, and the absence of socialevaluation threat appears to accelerate both behavioral skill acquisition and emotional regulation in ways that conventional classroom practice rarely achieves in a single session.

Future research should now move toward larger, multi-institutional randomized controlled trials to confirm generalizability across disciplines and cultures, incorporate objective behavioral coding (e.g., eye contact, gesture, prosody), and examine long-term skill retention and transfer to real-world presentations. Nevertheless, the present work offers clear empirical support and practical design guidelines for educators and institutions seeking evidence-based, scalable solutions to one of higher education’s most persistent challenges: helping students master public speaking with confidence and competence. VR has moved from promise to a proven pedagogical tool in this domain, and its systematic integration into communication curricula merits serious consideration.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Y.S., C.R. and B.F. Methodology: Y.S., L.G., S.Q. and G.L. Validation: Y.S., L.G. and S.Q. Investigation: Y.S., C.R. and B.F. Data curation: Y.S. and C.R. Writing—original draft: Y.S., C.R., B.F., L.G. and S.Q. Writing—review & editing: Y.S., C.R., B.F., L.G., S.Q. and G.L. Supervision: C.R. Funding acquisition: Y.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by ANID FONDECYT INICIACION, grant number: 11230984; Communication & Cognition Investigation Group, Universidad del Bío-Bío, grant number: GI2309435; DICREA Regular Research Proyect, Universidad del Bío-Bío grant number: RE2534906; Innovation Initiation Project (Design and conceptual validation—TRL 2—of an immersive VR environment to optimize the communication skills of first responders to emergencies in Chile), Universidad del Bío-Bío grant number: I+D45.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by Universidad del Bío-bío (code cecubb2024/1, 20 December 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ali, M. R., & Hoque, E. (2017). Social skills training with virtual assistant and real-time feedback. In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM international joint conference on pervasive and ubiquitous computing and proceedings of the 2017 ACM international symposium on wearable computers (pp. 585–592). Association for Computing Machinery. [Google Scholar]

- Bachmann, M., Subramaniam, A., Born, J., & Weibel, D. (2023). Virtual reality public speaking training: Effectiveness and user technology acceptance. Frontiers in Virtual Reality, 4, 1242544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartyzel, P., Igras-Cybulska, M., Hekiert, D., Majdak, M., Łukawski, G., Bohné, T., & Tadeja, S. (2025). Exploring user reception of speech-controlled virtual reality environment for voice and public speaking training. Computers & Graphics, 126, 104160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.-X., Hu, H., Yao, R., Qiu, L., & Li, D. (2024). A survey on the design of virtual reality interaction interfaces. Sensors, 24(19), 6204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, T. D., Campbell, D. T., & Shadish, W. (2002). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference. Houghton Mifflin. [Google Scholar]

- Crogman, H. T., Cano, V. D., Pacheco, E., Sonawane, R. B., & Boroon, R. (2025). Virtual reality, augmented reality, and mixed reality in experiential learning: Transforming educational paradigms. Education Sciences, 15(3), 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudley, J., Yin, L., Garaj, V., & Kristensson, P. O. (2023). Inclusive immersion: A review of efforts to improve accessibility in virtual reality, augmented reality and the metaverse. Virtual Reality, 27(4), 2989–3020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsler, I. (2025). Virtual reality in education and the co-construction of immediacy. Postdigital Science and Education, 7(2), 502–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, W., Drinkwater, R., Kelson, J., & Kabir, M. A. (2025). Self-guided virtual reality therapy for anxiety: A systematic review. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 200, 105902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H., dos Santos, T. F., Moussa, M. B., & Magnenat-Thalmann, N. (2025). Mitigating the uncanny valley effect in hyper-realistic robots: A student-centered study on LLM-driven conversations. arXiv, arXiv:2503.16449. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan-Rakowski, R., & Gruber, A. (2023). The impact of high-immersion virtual reality on foreign language anxiety. Smart Learning Environments, 10(1), 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kätsyri, J., Förger, K., Mäkäräinen, M., & Takala, T. (2015). A review of empirical evidence on different uncanny valley hypotheses: Support for perceptual mismatch as one road to the valley of eeriness. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kryston, K., Goble, H., & Eden, A. (2021). Incorporating virtual reality training in an introductory public speaking course. Journal of Communication Pedagogy, 4, 133–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunz, K., Brändle, M., Zinn, B., & Hirsch, S. (2025). Moments of stress in the virtual classroom—How do future vocational teachers experience stress through 360° classroom videos in virtual reality? Journal of Technical Education, 13(1), 82–115. [Google Scholar]

- Laine, T. H., Lee, W., Moon, J., & Kim, E. (2025). Building confidence in the metaverse: Implementation and evaluation of a multi-user virtual reality application for overcoming fear of public speaking. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 199, 103487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, C. (2024). Improving virtual reality exposure therapy with open access and overexposure: A single 30-min session of overexposure therapy reduces public speaking anxiety. Frontiers in Virtual Reality, 5, 1506938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardon, A. K., Wilson, D., Leake, H. B., Harvie, D., Andrade, A., Chalmers, K. J., & Moseley, G. L. (2025). The acceptability, feasibility, and usability of a virtual reality pain education and rehabilitation program for veterans: A mixed-methods study. Frontiers in Pain Research, 6, 1345678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendzheritskaya, J., Hansen, M., & Breitenbach, S. (2024, June 18–21). The effects of virtual reality learning activities on student teachers’ emotional and behavioral response tendencies to challenging classroom situations. 10th International Conference on Higher Education Advances (pp. 367–374), Valencia, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Mori, M. (1970). The uncanny valley. Energy, 7(4), 33–35. [Google Scholar]

- Oje, A. V., Hunsu, N. J., & Fiorella, L. (2025). A systematic review of evidence-based design and pedagogical principles in educational virtual reality environments. Educational Research Review, 47, 100676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M., Simões de Almeida, R., Veloso Gomes, P., Donga, J., Marques, A., Teixeira, B., & Pereira, J. (2024). Effectiveness of virtual reality in reducing public speaking anxiety: A pilot study. In VII Congreso XoveTIC: Impulsando el talento científico (pp. 371–376). Servizo de Publicacións, Universidade da Coruña. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson, A., Temple, C., Anderson, N., Rogalski, C., & Mentzer, K. (2025). The virtual stage: Virtual reality integration in effective speaking courses. Information Systems Education Journal, 23(4), 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satake, Y., Yamamoto, S., & Obari, H. (2023). Effects of English-speaking lessons in virtual reality on EFL learners’ confidence and anxiety. Frontiers in Technology-Mediated Language Learning, 1, 26–40. [Google Scholar]

- Shirtcliff, E. A., Finseth, T. T., Winer, E. H., Glahn, D. C., Conrady, R. A., & Drury, S. S. (2024). Virtual stressors with real impact: What virtual reality-based biobehavioral research can teach us about typical and atypical stress responsivity. Translational Psychiatry, 14(1), 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stein, A. T., Levihn-Coon, A., Pogue, J. R., Rothbaum, B., Emmelkamp, P., Asmundson, G. J. G., Carlbring, P., & Powers, M. B. (2019). Virtual reality exposure therapy for anxiety and related disorders: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 61, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, Y. L., Chang, V. Y. X., Ang, W. H. D., Ang, W. W., & Lau, Y. (2025). Virtual reality exposure therapy for social anxiety disorders: A meta-analysis and meta-regression of randomized controlled trials. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 38(2), 141–160. [Google Scholar]

- Thyer, B. A. (2012). Quasi-experimental research designs. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Valls-Ratés, Ï., Niebuhr, O., & Prieto, P. (2024). VR public speaking simulations can make voices stronger and more effortful. In Proceedings of the 16th international conference on computer supported education (Vol. 1, pp. 256–263). SCITEPRESS—Science and Technology Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C., Zhang, J., Hu, Y., Yang, X., Chen, M., Shan, M., & Li, L. (2024). The impact of virtual reality on practical skills for students in science and engineering education: A meta-analysis. International Journal of STEM Education, 11(1), 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).