Abstract

A global push for teaching science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) as a multidisciplinary endeavor is becoming increasingly prevalent in primary education. To understand how teachers are prepared to meet this need, we examined the programmatic design of seven teacher education programs, identified from among seventeen Robert Noyce Teacher Scholarship projects that focused on integrated STEM teacher education at the primary level. Specifically, we asked how the programmatic features and structures of the teacher education programs presented opportunities for prospective and practicing teachers to build capacity for integrated STEM teaching. Using case study methodology and qualitative content analysis, this study explored how primary teacher education programs framed integrated STEM across and within courses. The findings suggest that current initiatives aimed at meeting critical needs in STEM education do not sufficiently foster a focus on integrated STEM components in teacher education, especially at the primary level. The findings highlight a need for more intentional development of integrated STEM programs targeting primary teachers and provide guidance for the development or redesign of programs that better meet the demand. Specifically, integrated STEM can be woven into programs through a varying number of courses, which are introduced either later or from the beginning of programs.

1. Introduction

A global push for teaching science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) as a multidisciplinary endeavor is becoming increasingly prevalent in primary education (i.e., the first stage of formal schooling), but teacher education focused on integrated STEM (iSTEM) lags far behind the growing need. Models for preparing prospective and practicing teachers for iSTEM education exist, but whether the outcomes of such programs meet the needs of teachers remains unknown (Corp et al., 2020). Given the limited understanding of how to prepare teachers for iSTEM education, teachers continue to face a number of challenges to implementing iSTEM in primary classrooms, including school structures (e.g., siloed curriculum, isolated working conditions, limited resources), limited experience with iSTEM as a unique multidisciplinary endeavor; and the absence of preparation for and instructional models of STEM integration (Ryu et al., 2019; Shernoff et al., 2017). Further complicating the landscape, teachers bring a broad range of conceptualizations of iSTEM to guide their pedagogical efforts, mirroring the wide variation in theory and practice within research and teacher education (Radloff & Guzey, 2016; Wieselmann et al., 2025). Although attention to integration is increasing, STEM teacher education continues to emphasize preparation for teaching a single subject (Zhang & Zhu, 2022), and building primary teachers’ capacity for iSTEM education will require a substantial change in approaches to teacher preparation (Shernoff et al., 2017).

This gap between demand and preparation for iSTEM teaching and learning may help explain why narrow instrumental goals, characteristic of content-driven curriculum and devoid of application to social and global contexts and issues, dominates STEM education in primary schools (Jones et al., 2025). Such a narrow execution fails to realize the full potential and promise of iSTEM education and ignores the benefits of a more purposeful approach to multidisciplinarity. Namely, iSTEM holds the potential to address “wicked problems,” or complex social issues that defy formulation, lack immediate or clearcut solutions, and require numerous perspectives to analyze and confront (Ritchey, 2013). By drawing on multiple disciplines in interconnected and complex ways, an aspirational goal for iSTEM education foregrounds building future generations’ capacity to address complex issues, seen, unseen and unforeseen, while also centering justice and sustainability (Jackson et al., 2021; O. Lee & Grapin, 2025; Lina et al., 2025).

Accordingly, this study sought to increase the field’s knowledge of features and structures for teacher preparation that show promise for supporting iSTEM teaching and learning in schools. The aim of this study was to identify teacher education programs with the explicitly stated purpose of preparing primary teachers for iSTEM education. Upon identifying such programs, we asked the following research question: How do programmatic features and structures create opportunities for prospective and practicing teachers to build capacity for iSTEM teaching? We sought to more deeply understand the trends and themes that might guide the development of more cohesive teacher education programs to meet a growing need and to realize the full potential of iSTEM education at the primary level.

1.1. Conceptualizing Integrated STEM Education

The acronym STEM first appeared in the 1990s, introduced by the National Science Foundation (NSF) as a way to elevate attention to science and strengthen the political voice of scientists, technologists, engineers, and mathematicians (English, 2016; Maass et al., 2019). Since then, various conceptualizations of STEM have emerged in education, which represent varying degrees of integration across individual disciplines: (1) a disciplinary approach presents concepts and skills separately for each discipline; (2) a multidisciplinary approach maintains separation of learning by discipline but connects concepts and skills under a broader, common theme; (3) an interdisciplinary approach connects concepts and skills from two or more disciplines, aimed at deepening learning; and (4) a transdisciplinary approach connects and applies concepts and skills from two or more disciplines to a real-world problem or project, which guides the learning experience (English, 2016). The last approach, transdisciplinary STEM education, has been amplified in recent years. For example, Perwaiz and Asunda (2025) defined iSTEM as “an approach to teaching and learning wherein the discrete content from science, technology, engineering, and mathematics, along with computational thinking, are seamlessly merged into real-world experiences that align with authentic problems and vocational practices in STEM fields” (Perwaiz & Asunda, 2025). Such conceptualizations reinforce that iSTEM is not a straightforward combination of two or more disciplines; instead, iSTEM leverages its own set of skills and practices that are necessary in the 21st century for solving problems that cannot be solved through one discipline alone (Jackson et al., 2021).

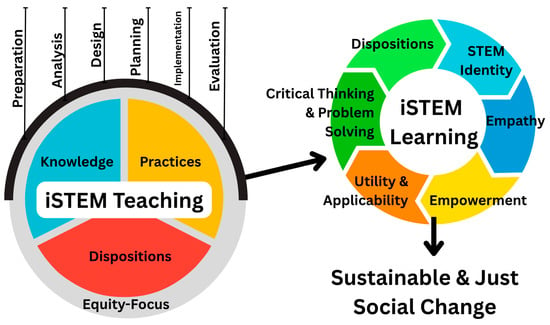

Figure 1 illustrates our conceptualization of iSTEM Education as a relationship between teaching iSTEM and learning iSTEM in ways that lead to addressing complex issues, while also centering justice and sustainability. In other words, Figure 1 provides an overview of the overarching conceptual framework, or the operationalization and organization of concepts and their application to practice, that guided this study. Specifically, we drew on, adapted and combined three existing conceptual frameworks, which we describe in more detail in the remainder of this section, to create our overarching conceptual framework (Jackson et al., 2021; Ku et al., 2025; Pynes et al., 2025). Namely, the Equity-Oriented STEM Literacy Framework (Jackson et al., 2021) served as the foundation for conceptualizing iSTEM learning. This existing conceptual framework is summarized on the right side of Figure 1 and labeled as “iSTEM Learning.” To conceptualize iSTEM teaching that supports the imagined learning processes and outcomes, we drew on the Model for Equity-Focused Transformational STEM Teacher Leadership (Pynes et al., 2025), which frames teaching capacity through knowledge, practices, and dispositions with an integrated equity focus. This conceptual framework is summarized on the left side of Figure 1 and is labeled “iSTEM Teaching.” We further elaborated on the knowledge and practices necessary for iSTEM teaching using the Six-Staged Integrated STEM Education Instructional Design Model (Pynes et al., 2025). This conceptual framework is summarized above the iSTEM Teaching representation in Figure 1, with the instructional design stages connected to teachers’ knowledge and practices.

Figure 1.

Conceptualization of iSTEM education. Adaptation of existing frameworks (Jackson et al., 2021; Ku et al., 2025; Pynes et al., 2025) to show a comprehensive conceptual framework for iSTEM teaching and learning that achieves the goal of preparing students to address complex issues through iSTEM with an emphasis on justice and sustainability.

To conceptualize iSTEM learning, we adopted Jackson et al. (2021) research-based conceptual framework for STEM literacy, which they described as the integration of two or more areas of STEM, through engagement of big ideas alongside the tools and knowledge necessary to apply STEM concepts to real-world problems, led by a student-centered, collaborative approach. The development of their Equity-Oriented STEM Literacy Framework followed from a systematic review of empirical research on STEM teaching and learning that positioned each and every student as belonging in STEM (i.e., the development of a STEM identity). Accordingly, the framework emphasizes how the processes and outcomes of iSTEM are unique in their own right, meaning that they are not simply an amalgamation of processes and outcomes in each discrete discipline. Specifically, iSTEM involves new ways of thinking and collaborating, necessitates critical thinking and problem solving, builds empathy, and fosters dispositions that value utility, applicability, and social change (Figure 1). Ensuring that every student has access to such quality iSTEM learning opportunities paves the way for realizing aspirational goals of iSTEM education that support just and sustainable futures (Jackson et al., 2021; O. Lee & Grapin, 2025; Lina et al., 2025). This conceptual framework could serve as a model for developing iSTEM learning experiences for primary students (Jackson et al., 2021), but additional conceptual frameworks are necessary to fully articulate the types of knowledge and practices necessary for primary teachers to implement such an approach to iSTEM.

Primary teachers usually hold responsibility for teaching all content areas in the school curriculum, but because iSTEM relies on unique processes and outcomes, it also requires different forms of teacher dispositions, knowledge and practices (Pynes et al., 2025). While any approach to instruction driven by collaborative student inquiry into real-world problems could support iSTEM education, project-based learning has shown to be a particularly effective approach to iSTEM, especially for fostering equity and civic engagement (M. Y. Lee & Lee, 2025; Mustafa et al., 2016). Project-based learning can be characterized as an instructional approach in which the teacher identifies well-defined learning outcomes, situates them within authentic, real-world problems, and guides students to learn across disciplines to address the problem (Savery, 2006). Accordingly, our conceptual framework for iSTEM teaching privileges instructional concepts and practices that support project-based learning. To teach in this way, iSTEM teachers must leverage content and pedagogical core practices from across STEM disciplines in increasingly seamless ways (Pynes et al., 2025). For example, they must be able to identify which integrations will become necessary as students explore real-world problems and plan for tasks that support students’ learning across those disciplines. Such intentional teaching also requires deep knowledge of students, including their prior experiences and knowledge in STEM disciplines and what they consider authentic problems (Ku et al., 2025). Moreover, teachers must regularly draw on their abilities to collaborate with other teachers and administrators to change both classroom-level and school-level structures and practices to support meaningful, deep and authentic iSTEM education (Ku et al., 2025; Pynes et al., 2025). Ku et al. (2025) proposed the conceptual framework, Six-Stage Integrated STEM Education Instructional Design Model, which summarizes and connects the knowledge and practices that teachers must leverage as they prepare to implement iSTEM. These stages involve preparing for iSTEM projects with colleagues; analyzing the background of authentic problems and students’ experiences and knowledge; designing projects around specific learning outcomes that are authentic to the context of the problem; planning specific learning tasks to support students; implementing projects and responding to students’ needs; and evaluating student learning and their own teaching (Ku et al., 2025). Beyond these forms of knowledge and practices, teaching iSTEM also demands a disposition towards continual growth (Pynes et al., 2025), as teachers must remain consistently open to learning as they move through the instructional design stages.

1.2. Research on Primary Teacher Education for Integrated STEM

Primary teachers express interest in teaching iSTEM (Shernoff et al., 2017), and many seeking to build their capacity to do so describe iSTEM in ways that align with research on high quality STEM education, including a focus on student inquiry, authentic contexts for learning, and collaboration (Wieselmann et al., 2025). Great variation exists, however, in how teachers frame disciplinary integration in iSTEM. The approach to integration may limit or expand possibilities in a number of ways. First, teachers may ignore specific STEM disciplines. For example, engineering is often missing from preservice primary teachers’ descriptions of iSTEM (Perwaiz & Asunda, 2025; Wieselmann et al., 2025). Second, teachers may foreground one STEM discipline. For example, teachers may rely on the engineering design process for iSTEM education (Perwaiz & Asunda, 2025; Wieselmann et al., 2025), likely because engineering can be thought of as the “practical application of scientific knowledge to solve everyday problems” (DiFrancesca et al., 2014). Third, teachers may seek to connect STEM to other disciplines. For example, teachers may see benefits to integrating the arts and STEM (i.e., iSTEAM), especially given evidence suggesting art education can improve cognitive scores (Colucci-Gray et al., 2019). Given this complexity and variation, teachers experience difficulty when attempting to translate theories of iSTEM education into practice.

Teachers identified the following as necessary for supporting their iSTEM teaching goals: confidence related to specific subject areas and to student-centered instruction; collaboration with colleagues; integration across disciplines; planning and implementation; and student support (Ellebæk et al., 2025). Without this capacity, teachers may approach iSTEM teaching by adapting a mathematics or science task to incorporate technology or by adding learning goals for an additional STEM discipline, but this approach falls short of the true integration described in the previous section (Fitzpatrick & Leavy, 2025). The misconception of iSTEM as simply a combination of aspects from each separate discipline can linger, even following participation in iSTEM-focused teacher education, (Bartels et al., 2019; Ryu et al., 2019; Wieselmann et al., 2025), and recent research suggests that teachers may struggle more with the pedagogical practices and processes related to student inquiry into authentic problems than with specific subject matter knowledge (Ellebæk et al., 2025). Additional research is needed to identify ways to build primary teachers’ capacity for deep, meaningful integration that arises naturally from authentic problems.

The most common approach to iSTEM teacher education involves small, isolated revisions to existing teacher preparation courses, such as adding projects or activities, or short-term teacher development workshops for practicing teachers (Corp et al., 2020). As a result, most studies of primary teachers’ preparation for iSTEM analyze the effectiveness or outcomes of standalone iSTEM teacher education initiatives (Fitzpatrick & Leavy, 2025; O’Dwyer et al., 2023; Rinke et al., 2016). These initiatives can take different forms, including collaboration across traditional mathematics and science teaching methods courses. For example, programs may leverage existing courses but incorporate an iSTEM focus. Combining traditional mathematics and science methods courses or implementing shorter collaborative units within these courses shows promise for increasing teachers’ capacity to recognize and design iSTEM lessons (Bartels et al., 2019) and to promote STEM literacies through content integration, engineering and design, and arts (Rinke et al., 2016). Alternatively, programs may create new courses that prioritize iSTEM. Offering courses that specifically focus on engineering and making meaningful connections from engineering to mathematics and science are promising approaches (DiFrancesca et al., 2014; Webb & LoFaro, 2020). For example, following a 12-week module, preservice primary teachers gained deeper understanding of STEM practices (not just content), leading to increased attention to student inquiry and authentic learning contexts. Teachers also built capacity to teach engineering (which was identified as an area of under-preparation), but at the expense of integrating mathematics meaningfully (Fitzpatrick & Leavy, 2025).

Another approach to supporting teachers’ development of iSTEM teaching engages them as learners in iSTEM lessons; this is a favored approach because many teachers have not experienced iSTEM learning themselves (Bartels et al., 2019; Lesseig et al., 2016; Murphy & Mancini-Samuelson, 2012; O’Dwyer et al., 2023). This approach has shown to have a moderately positive impact on teachers’ capacity for interdisciplinary teaching (Wu et al., 2024). Another notable approach to supporting teachers’ learning of iSTEM teaching is to engage them in selecting, modifying, or developing integrated STEM lessons or tasks (Kim & Bolger, 2017; Rinke et al., 2016; Ryu et al., 2019) and in teaching STEM in classroom contexts (O’Dwyer et al., 2023). These efforts have been shown to positively impact primary teachers’ overall efficacy in iSTEM education, including attitudes toward iSTEM (Kim & Bolger, 2017) and lesson planning practices for iSTEM (Rinke et al., 2016; Ryu et al., 2019). In general, teachers’ self-efficacy for iSTEM teaching is linked to their participation in such teacher development initiatives that are specifically focused on iSTEM and their school’s support for such an instructional approach (Alhassan, 2025).

The research suggests that a more effective approach to preparing teachers for iSTEM would require a substantial change in the approach to teacher preparation, for both prospective and practicing teachers, in terms of the design of courses and workshops (Shernoff et al., 2017). More substantial revisions are especially important for achieving more equitable iSTEM learning, as described by our conceptual framework, given that none of the above research-based examples take up equity considerations in a meaningful way. In general, little is known about the design or outcomes of programs that attend to iSTEM education explicitly and consistently. Focused exclusively on technology and engineering integration, one study (Rose et al., 2017) provides some insights into the overall structure of programs that center integration and multi-disciplinarity. Rose et al. (2017) found that programs integrating technology and engineering generally took one of six approaches to preparing teachers. Specific courses on technology and engineering (Approach 1) were common; and a coordinated set of courses in iSTEM sometimes led to a concentration area of study (Approach 2) or a certificate (Approach 3). They also found two minor programs (Approach 4), Integrative STEM Education at Millersville University and Technological Literacy at Pittsburg State University, and one Bacher’s degree (Approach 5) in Integrative-STEM Education in elementary K-6 STEM education at The College of New Jersey. Finally, they found one combined undergraduate and master’s certificate program (Approach 6) at the University of Arkansas, which offered a certificate program in STEM Education for their Master of Arts in Childhood Education. In this study, we sought to expand the field’s knowledge of iSTEM teacher education at the program level and to provide additional insights into the design aspects of those programs, beyond the overarching model for a program.

2. Materials and Methods

This research was guided by case study methodology (Yin, 2009). Namely, we leveraged a single-case design to investigate the phenomenon of primary teacher education programs purposefully aimed at preparing teachers for iSTEM education. Embedded within the single case, we viewed each individual teacher education program as a unit of analysis, maintaining a focus at the overall program level. Based on our knowledge of the field, we expected to find only a limited number of programs purposefully designed for iSTEM teacher education, providing the rationale for a single case study given the revelatory nature of the research (Yin, 2009). In the next section, we describe the systematic process by which we identified teacher education programs to include in this study, and then we conclude by detailing the generation and analysis of data.

2.1. Identifying Integrated STEM Teacher Education Programs for Case Study

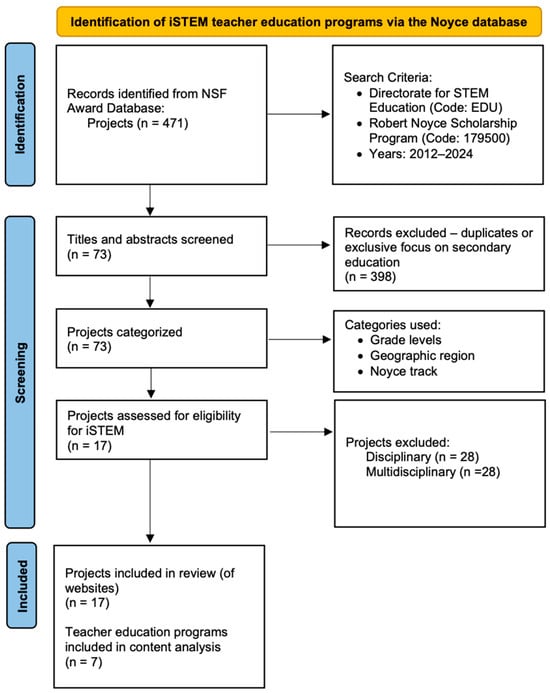

We used a systematic process, adapted from methods for systematic literature reviews (Figure 2; Page et al., 2021), to identify programs purposefully designed for iSTEM teacher education for this case study. Because a comprehensive database of teacher preparation programs does not exist, we selected the database of projects currently and previously supported through the NSF’s Robert Noyce Teacher Scholarship (Noyce) program (National Science Foundation, 2023) as a source for identifying programs. We chose to focus on Noyce-funded projects to identify teacher education programs for several reasons. First, the Noyce program prioritizes innovation, which research suggests is necessary for effective iSTEM teacher education (Shernoff et al., 2017). Moreover, the Noyce program seeks to address critical shortages in STEM education by recruiting, preparing and retaining effective primary and secondary teachers. Because of the gap between preparation for iSTEM teachers and the rapidly emerging need, we can assume a critical shortage. Finally, the Noyce program provides funding, in the form of scholarships, for both prospective and practicing teachers. Scholarships support undergraduates majoring in a STEM discipline to earn their initial teaching credentials (Track 1), STEM professionals to transition to teaching careers (Track 2), and practicing teachers to develop additional expertise in STEM teaching (Track 3). This allowed us to identify both initial teacher preparation programs and advanced education options for practicing teachers. The Noyce program also funds research on Noyce program outcomes (Track 4), and research projects related to Noyce programs may overlap with projects funded through the Engaged Student Learning track in the Improving Undergraduate STEM Education program. That program funds the development and study of new instructional materials and methods (National Science Foundation, 2022), further increasing the likelihood of finding innovation in coursework. Finally, the Noyce program also funds projects designed to build capacity for teacher education programs that would qualify for future Noyce awards, increasing the likelihood of innovation in the form of substantial (re)structuring at the program level.

Figure 2.

Flow diagram for the systematic identification of teacher education programs purposefully focused on iSTEM for inclusion in the case study. Methods for identification, screening and inclusion adapted from methods for systematic literature reviews (Page et al., 2021).

Within NSF’s award database, we searched for awards made through the Directorate for STEM Education (Code: EDU) and the Robert Noyce Scholarship Program (Code: 179500) from 2012–2024. We selected 2012 as the initial date for our search given that research on iSTEM preservice teacher education began appearing around 2012 (Zhang & Zhu, 2022). Our search returned 471 results, which we downloaded as a spreadsheet with the following information: award number; project title; start date; principal investigator (PI); state; organization; end date; PI e-mail address; organization address; and abstract. In our initial round of analysis, we worked within Google Sheets and reviewed the title and abstract of each project to remove duplicates (e.g., Collaborative Research projects listed multiple times) and to exclude all projects that focused exclusively on secondary STEM education This left 73 programs for the next stage of analysis that focused on identifying the grade-level bands: Kindergarten (K)-12, K-6 (primary) and K-8 (primary and middle). We reviewed project titles, abstracts and locations (i.e., state) and categorized the 73 funded projects by geographic region (West/Hawaii, Southwest, Southeast, Northeast/Mid-Atlantic, Midwest/Plains States, and Multi-region), Noyce track, and identified grade level bands. We also created data displays that looked at the intersections of these categories.

Next, we reviewed again the title and abstract for each project and categorized the descriptions based on the level of STEM integration described, because we sought to include programs with a specific emphasis on preparing teachers for iSTEM. We developed categorization criteria based on the conceptual framework for STEM education and its degrees of integration described by English (2016). We chose this framework because it acknowledges varying degrees of connecting multiple STEM disciplines, as described in Section 1.1. We considered those programs focused on preparing teachers in a single subject area as disciplinary. For example, the Preparing the Effective Elementary Mathematics Teacher project focused exclusively on mathematics:

The program goals are to: recruit high-quality pre-service elementary teachers for effective mathematics teaching, prepare high-quality pre-service elementary teachers for a career of effective mathematics teaching in a high-need school, and promote the retention of high-quality elementary math teachers in high-need schools. Accordingly, this project broadens participation to under-represented groups in mathematics by recruiting new elementary mathematics teachers to the profession, providing them with extraordinary preparation experiences, and placing them in the schools where they are needed most.

We considered programs that focused on two or more separate disciplines but under a common theme as multidisciplinary. Multidisciplinary programs maintained an emphasis on preparing teachers for single-subject-area instruction, and the common theme connecting disciplines could be either content-based or pedagogy-focused. For example, the Integrating Science Content and Engineering Thinking in the Elementary Classroom emphasized preparing primary teachers for science instruction under common themes from the engineering design process. In the abstract, the engineering design process is positioned as “a teaching-learning approach that can be used to promote science learning,” unifying science content and engineering practices but maintaining disciplinary separation and an emphasis on science (not integrated) learning. In other abstracts, disciplines were connected under a common pedagogical theme. For example, Developing and Implementing Case-Based Scenarios to Support Elementary Pre-Service Teachers’ Enactment of Equitable Mathematics and Science Instruction, involved the development of cases under the common theme of culturally grounded pedagogy but maintained the separation of disciplines by implementing cases “in university-based elementary mathematics and science methods courses.”

We considered those projects that closely linked concepts and skills from two or more disciplines for the purpose of deepening learning (i.e., interdisciplinary) or for applying to real-world problems or projects (i.e., transdisciplinary) as emphasizing iSTEM. Our conceptualization of iSTEM in Section 1.1 prioritizes applying knowledge and skills in authentic contexts (i.e., transdisciplinary), and in some descriptions this focus was evident. For example, the abstract for NebraskaSTEM: Supporting Elementary Rural Teacher Leadership described teacher development and implementation of “STEM initiatives (school/community-based STEM projects),” which suggested application of iSTEM to authentic problems. Generally, however, we found it difficult to determine whether integration of disciplines included an emphasis on application from the abstracts alone. For example, Preparing Teachers to Integrate Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math in Elementary Classrooms described preparing prospective primary teachers through “topic integration in STEM” and “service learning,” but the description did not explicitly connect service learning as a means of using iSTEM to address community-based problems. Therefore, we decided to include descriptions that we saw as interdisciplinary approaches to integration so as not to unnecessarily exclude projects in subsequent analyses.

For those Noyce projects identified as focused on preparing primary teachers for iSTEM education (n = 17), we identified the universities and their respective teacher education programs involved in the project (See Section 3). Next, we reviewed project websites and/or university websites to find more detailed descriptions of teacher education programs included in the awarded projects. This analytic step helped us in shifting the focus from awarded NSF projects to university-based primary teacher education programs focused on iSTEM. Based on program descriptions, we excluded some teacher education programs for consideration in subsequent analyses because we found that the programs did not meet the criteria for inclusion (i.e., they were not iSTEM or did not include primary teacher education). For example, we found that some Noyce projects described as focusing on the K-12 grade band actually focused on secondary education. This was expected because “K-12 education” is used commonly in the United States to describe formal education generally. For remaining programs, we contacted the Noyce project investigator or the program director from the university website and requested additional information such as course syllabi. Responses were limited, which forced us to rely mostly on information available from the websites, and necessitated that we eliminate some programs from the analysis because we had insufficient information to analyze the program’s overarching program design related to iSTEM. Ultimately, we found sufficient information for the analysis of programs from seven universities (Table 1). For those programs, we generated data from university and program websites, including program overviews, programs of study (i.e., requirements for completing the program), descriptions of required courses, and course syllabi (when available or shared with us). Table 1 provides information about the nature of each program included in this case study and information about the available data sources.

Table 1.

Seven teacher education programs included in the case study. Includes contextual information about each program, specifically the nature of the degree or other program and a description of iSTEM features, along with available data sources for each program.

2.2. Analyzing the Case of Integrated STEM Teacher Education Programs

We used qualitative content analysis to analyze program overviews, programs of study, descriptions of required courses and course syllabi. Specifically, we used a directed content analysis approach, which is appropriate for validating or extending theory (Carley, 1990). Directed content analysis allows researchers to identify the presence of specific ideas from theory in text; these ideas can appear either explicitly or implicitly. Across iterative rounds of analysis, the first author applied the codes developed in our previous round of analysis for indicating the level of STEM integration (English, 2016). More specifically, we identified as specific aspects of the program or courses as disciplinary, multidisciplinary or iSTEM in the way we had previously done for project abstracts. For example, references to a required mathematics teaching methods course in the program of study would be labeled as “disciplinary.” If the course description or the syllabus, however, indicated connections between mathematics and another STEM disciplinary, the descriptions of a specific course could be labeled as multidisciplinary or iSTEM.

Next, the first and second authors sorted excerpts from the analyzed documents (with multiple data sources for each program) by level of STEM integration (i.e., disciplinary, multidisciplinary, iSTEM) and identified themes across excerpts through the lens of our conceptual framework for iSTEM education (Figure 1). More specifically, we created codes to further describe the excerpts in relation to a focus on teacher knowledge, practices, or dispositions. By looking at the intersection of STEM integration level with teacher education focus (i.e., knowledge, practices, and dispositions), we were able to identify trends in how and to what extent programs emphasized iSTEM across all the different dimensions of teacher capacity building. We also added additional codes for those excerpts identified as iSTEM to provide further nuance. Specifically, we added codes to indicate, when possible, approaches to support teachers’ development of knowledge and skills in relation to the instructional design features of iSTEM teaching (i.e., preparation, analysis, design, planning, implementation, and evaluation). This allowed us to consider what areas of iSTEM teaching knowledge and practices programs emphasized. Overall, this analysis facilitated the identification of trends in programmatic design features of primary teacher education for iSTEM.

3. Findings

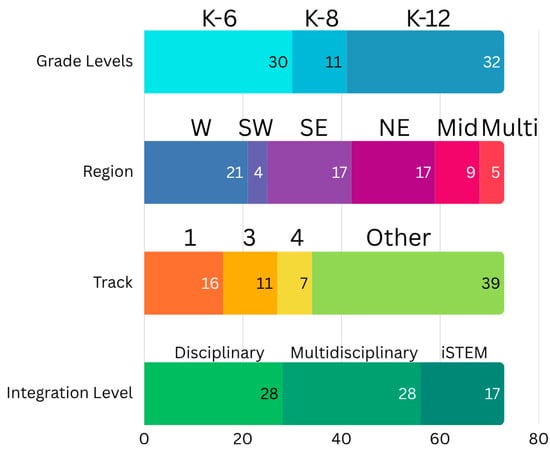

From the 471 Noyce projects initially reviewed, we found 73 projects which included a focus on primary teacher education. Findings from our analysis of those 73 projects are shown in Figure 3. Notably, we found only 30 projects focused exclusively on primary (K-6) teacher education. A majority of projects attended to middle grades (n = 11) in addition to primary levels or identified the full spectrum of formal schooling (n = 32). We found that the projects spanned all geographic regions of the United States. Yet, among the 73 projects, we found a relatively limited number focused on scholarships for prospective or practicing teachers (Tracks 1, 2, or 3). We identified 16 Track 1 projects, which support undergraduates majoring in a STEM discipline to earn their initial teaching credentials. Notably, 13 of these overlapped with the K-12 focus, and only two exclusively focused on primary education: Preparing Teachers to Integrate Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math in Elementary Classrooms and Investigating Learning Progression Modules in Integrated Science Content Courses for Preservice Elementary Teachers. The remaining project, Strengthening Mathematics Instruction for Elementary and Middle Schools, focused on the K-8 grade bands. The primary (n = 4) or combined primary and middle grades (n = 2) focus was more common for Track 3 projects, which supports practicing teachers to develop additional expertise in STEM teaching. Yet, the K-12 focus among Track 3 projects remained prevalent (n = 5). We did not find any Track 2 projects, which support STEM professionals to transition to teaching careers, which included a focus on primary education. The majority of projects (n = 46) did not fit within the scholarship tracks. Instead, most projects were research projects (Track 4, n = 7; Engaged Student Learner Track, n = 31) or did not specify a track (n = 8).

Figure 3.

Findings from analyzing the 73 funded Noyce projects’, which included a primary teacher education, geographic region (West/Hawaii, Southwest, Southeast, Northeast/Mid-Atlantic, Midwest/Plains States, and Multi-region), Noyce track, identified grade level bands, and level of STEM integration.

We found that most of the 73 projects approached STEM teacher education in either a disciplinary (n = 28) or multidisciplinary (n = 28) way; the abstracts from only 17 projects suggested iSTEM teacher education. These 17 projects are identified in Table 2, which includes information about each project’s stated grade band, Noyce track, and the universities participating in the project. Notably the majority of these projects are exclusively focused on primary (K-6) teacher education (n = 10), with only one extending through middle grades and five focused on K-12. Most of these projects were not focused on teacher scholarships (n = 11), with most described as research projects (i.e., Noyce Track 4 or Engaged Student Learner Track). Projects focused on teacher scholarships included four at the undergraduate level for prospective teachers (Track 1) and two for practicing teachers (Track 3). Among the Track 1 proposals was one project, Preparing Teachers to Integrate Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math in Elementary Classrooms, focused exclusively on primary teacher education.

Table 2.

Noyce projects identified from their abstracts as focusing on iSTEM teacher preparation, listed alphabetically by project title. Information about each project’s grade band, Noyce Track and participating universities are also included. Teacher education programs at universities in bold met the criteria for iSTEM education at the primary level, and sufficient information was available for subsequent analysis of programs.

From these 17 projects, we identified teacher education programs at seven universities (bolded in Table 2; described in Table 1) that met the criteria for iSTEM education at the primary level and for which information was sufficiently available for subsequent analysis. All of these programs came from projects focused exclusively on primary teacher education, and all but one came from research-focused projects rather than projects focused on teacher scholarships. Six programs provided detailed course listings with comprehensive descriptions on their websites; the remaining program at Sacred Heart University provided less detail about specific courses but we chose to include it because of its unique status as a Track 1 Noyce-funded teacher education program focused exclusively on primary education. Moreover, we obtained two course syllabi directly from faculty members we contacted at Indiana University Southeast and Towson University. Our analysis revealed that courses within these programs existed along a spectrum of STEM integration, ranging from single-discipline focused to those embracing multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary or transdisciplinary approaches. Across this trend, we identified three themes: (1) limiting iSTEM to specific courses; (2) transitioning from a disciplinary to iSTEM focus across the program; and (3) emphasizing iSTEM from the beginning of a program.

3.1. Integrated STEM Limited to Specific Courses

While the abstracts for projects involving both Purdue University and Sacred Heart University suggested alignment with iSTEM, the programmatic structures at these institutions fell short of meeting calls within the field (Shernoff et al., 2017) for substantial overhaul to prepare primary teachers for iSTEM. At Purdue University, the optional iSTEM concentration for K-12 education, within the Bachelor of Arts in Elementary Education program, demonstrates a strong emphasis on elementary engineering and its connections to science education (i.e., a multidisciplinary approach). The university’s broader aim, through their awarded project, was to redesign their science teacher preparation model to align with the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS). The course description for EDCI 53900, titled Introduction to K-12 Integrated Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math Education, explicitly states that “students will explore implications for the teaching and learning of integrated STEM in a K-12 context.” This course description suggests a genuine commitment to integrated approaches through a focus on teaching practices; however, when we examined the teaching methods courses within the program elementary education program, we found they are taught through a strictly disciplinary lens, specifically focusing on approaches to teaching and learning for the discipline of science. This represents a significant departure from truly integrated pedagogy. Purdue, however, does require participation in Engineering Projects in Community Service (EPICS), a yearlong course where students collaborate in multidisciplinary teams on engineering-based project. While Purdue’s programmatic structure for iSTEM may be limited in scope, the program’s requirement that students complete an EPICS course provides a valuable experiential iSTEM learning opportunity. By participating in EPICS, teachers engage with iSTEM from a student perspective, which allows them to understand the learning experience firsthand. This dual positioning is pedagogically significant because as they work through iSTEM challenges as learners themselves, they can simultaneously reflect on and develop knowledge and dispositions to support effective iSTEM teaching. Moreover, observed pedagogical strategies might become part of their emerging teaching practices. The Bachelor of Science and combined Master of Arts in Teaching Elementary Education program at Sacred Heart University follows a similar pattern to Purdue in terms of the required courses. Although the institution articulates a mission to prepare all elementary teachers to engage with curriculum through inquiry-based and iSTEM approaches, their courses are ultimately delivered through traditional disciplinary silos. We did observe a few modifications to the programmatic structure, such as modifying the method courses; however, they do not offer a series of courses focused on iSTEM in the way that Purdue University does.

As indicated in Table 1, the programmatic structures of the Bachelor’s programs at the Indiana University Southeast and Townson University appeared to be disciplinary in nature based on program descriptions. We included these programs in our case study, however, because we had access to course syllabi that provided evidence of an iSTEM approach within individual courses. These syllabi allowed us to dive deeper into the approach of emphasizing iSTEM within specific courses, that seem disciplinary at first glance. The two course syllabi we received—one from each university—revealed a more veiled effort to incorporate iSTEM teaching preparation. In fact, the coursework and goals within each course aligned with multidisciplinary and iSTEM approaches rather than strictly disciplinary ones. At Indiana University Southeast, we examined the syllabus for the course Methods in Teaching Science in Elementary. The course description reads as follows:

E328 is designed to provide practical experience in the development, planning and teaching of learning experiences appropriate for elementary school children in the context of science. The major focus is on direct involvement with laboratory experiences as a base for developing a working knowledge of science, to understand learning experiences appropriate to elementary school children, to develop teaching competencies, to convey the nature, scope and approaches of contemporary elementary school science curricula and to identify purposeful goals for the learning and teaching of science.

This description suggests a disciplinary focus; however, the course goals extend beyond simply preparing teachers to teach science at the elementary level. The ultimate objective is for students to “design an interdisciplinary STEM unit map.” To enable students to reach this culminating goal, the course employs a scaffolded structure in which each objective builds progressively upon the previous one to develop knowledge for iSTEM teaching. At the outset, students learn to “apply STEM content knowledge,” which grounds them in working within individual content disciplines. The course then transitions into a multidisciplinary phase where teachers “demonstrate their understanding of the three forms of knowledge associated with learning about STEM,” requiring them to make connections across multiple disciplines. Finally, the course culminates in the development of an interdisciplinary unit, synthesizing all prior learning into an integrated approach by applying knowledge to practice. Students are expected to engage in some of the instructional design practices identified in our conceptual framework, namely, design and planning.

Towson University’s Earth-Space Science course follows a different approach. While the course focuses on a subdiscipline within science, it employs a scaffolded structure with sequential units in Engineering, Geology, Climate Change, Light, and Astronomy. Although discrete disciplines are identified for each unit, all units begin with a multidisciplinary approach (i.e., connected two or more disciplines under the content-based theme of the unit), supporting the development of teacher content knowledge across disciplines. The project within the Engineering Unit asks students to demonstrate their “knowledge and application of the engineering design project…understanding what counts as technology.” This is the first opportunity for students to experience iSTEM learning for themselves. As the subsequent units progress, they deepen the focus on integration. Throughout the entire course, there is a threaded discussion examining how engineering, geology, light, and climate change are interconnected in the local geography, using the Conowingo Dam in Northeastern Maryland as a concrete example, suggesting an iSTEM approach. The instructor’s rationale for this interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary discussion across science subdisciplines is to “represent the thematic way to connect content in our course to technology that has been a part of Northeastern Maryland for nearly 100 years.” This course provides an opportunity for prospective teachers to experience iSTEM learning, helping them to develop the knowledge and dispositions that support iSTEM teaching, but it does not present opportunities for bridging knowledge and teaching practice.

3.2. From Disciplinary to Integrated STEM Across a Program

Another trend we identified in programmatic structures was beginning with a disciplinary or multidisciplinary focus and progressing toward iSTEM approaches. Based on the course descriptions provided on their websites, we found evidence of this approach at Bridgewater State University within their Master of Education in Elementary Education. The methods courses in elementary mathematics and science were rooted in a disciplinary approach. As students progress beyond methods courses, however, the program shifted toward a multidisciplinary and iSTEM emphasis. For instance, Bridgewater State University’s Technology and STEM Education course centers a multidisciplinary approach by preparing teachers to use technology effectively to enhance student learning. This course emphasizes research-driven pedagogical practices that support “conceptual understandings across STEM domains.” Similarly, the Science and Engineering Practices in the Elementary Classroom course addresses NGSS standards but extends beyond simply teaching those standards in relation to teacher knowledge and practice. Instead, it prepares teachers to apply NGSS standards to real-world engineering contexts, which is characteristic of iSTEM. Through this process, students engage not only with science and engineering but also with writing and drawing, thereby incorporating disciplines beyond traditional STEM fields. These more advanced courses are available to all students but are especially relevant to students who choose to pursue a STEM education concentration. This indicates that the STEM education concentration helps to support preparation for iSTEM.

3.3. Integrated STEM from the Start

Another approach we found, based on the program overviews and course descriptions, involved emphasizing iSTEM from the beginning of the teacher education program. We found evidence of this approach at Southern Methodist University, which offers a Master of Education with a STEM area of interest, and Point Park University, which offers a graduate-level integrative STEM education endorsement. Southern Methodist University program’s STEM courses begin at a multidisciplinary level from the outset. The course titled The Science of Learning and STEM explores maker-based learning, nontraditional sites for teaching and learning, and examines how problem-solving, tinkering, and exploring technologies can lead to iSTEM lesson plans by connecting teacher knowledge to practice. The subsequent three courses build upon this foundation by moving from theory into practice regarding iSTEM. These final three required courses prepare students to design and implement classroom activities in community settings, giving students the opportunity to experience the full instructional design process linking knowledge and practice in our conceptual framework. Students practice creating maker units, lessons, and activities that occur both inside and outside the classroom and within the broader community. The coursework culminates in a practicum, essentially a capstone project, where students experience iSTEM implementation in their local community.

Point Park University employs a unique (within this study) programmatic approach to ensure authentic iSTEM education. They have developed a twelve-credit Integrated STEM Education Endorsement. The four required courses center inquiry-based learning methodologies alongside experiential learning in makerspaces within primary STEM education contexts. The Foundations of STEM Education and Integrated Curriculum course takes an approach similar to Bridgewater’s Science and Engineering Practices in the Elementary Classroom. This course explores NGSS, mathematics, engineering, and technology standards, to develop teacher knowledge, while examining how these standards can be integrated and connected with “science, technology, engineering, and mathematics with other subjects like history, arts, and social studies.” This facilitates the linking of knowledge and iSTEM teaching practice by making connections across the full primary school curriculum.

4. Discussion

Opportunities for high-quality learning in the STEM disciplines are critical for later academic success, but teachers’ capacity to meet those needs fall short (Hapgood et al., 2020). Findings from our analysis of the Noyce projects point to implications for additional research and development to meet the critical need for effective iSTEM teachers at the primary level. Specifically, we found that approximately 15% (73 of 471) of Noyce awards included a focus on primary STEM education. This limited representation suggests that even initiatives such as Noyce, specifically designed to bolster innovation in teacher education and facilitate the recruitment, preparation and retention of teachers in critical shortage areas like STEM, are falling short of meeting critical needs in primary education. Moreover, we found very few Noyce projects focused on primary education that distributed scholarships to prospective or practicing primary teachers. The Noyce program requirement for undergraduate majors in STEM disciplines likely makes it challenging for programs to offer Track 1 programs for prospective primary teachers, who usually major in education. This played out in our analysis as we visited university websites and found that many projects, which described a K-12 focus, served only secondary prospective teachers. One program within our case study, namely Purdue University, offers a possible solution for this challenge—by offering a K-12 focused iSTEM concentration, primary teachers can benefit from opportunities from better-resourced (at least through Noyce) secondary STEM teacher education programs. Yet, removing the barrier of an undergraduate STEM major could open up possibilities for supporting the recruitment, preparation and retention of more iSTEM teachers for primary schools. The prevalence of Noyce projects focused on research in primary teacher education suggests that some resources are available to develop and study innovative iSTEM primary teacher education. Yet, less attention has been paid to attracting teachers into the resulting programs, and far less support is available than is offered at the secondary level.

The relative prevalence of Noyce-funded research projects at the primary level and the small number of projects with an explicit iSTEM focus also suggest that few universities have established primary teacher preparation programs capable of preparing primary teachers for iSTEM. In other words, not enough programs exist with an iSTEM education focus to meet the growing need because the field is still figuring out how to prepare iSTEM primary teachers. This was reiterated by our findings, which indicated that program descriptions may continue to communicate a disciplinary focus, even when courses support iSTEM experiences. This was the case at Indiana University Southeast and Townson University. Thus, programmatic (re)design lags behind efforts to meet the growing need for iSTEM. Additional research and development are necessary to reimagine primary teacher education for iSTEM, and our findings from analysis of seven programs provide some guidance on how programs might approach program redesign.

Our findings echoed those of prior research that suggests that small, isolated revisions to existing courses or workshops is the most common approach (Corp et al., 2020). Our analysis of two courses from the Indiana University Southeast and Towson University reveal one possibility for transforming teacher preparation programs without necessarily creating entirely new courses. Course restructuring represents a viable alternative pathway, and research suggests some success with this course-level approach (e.g., Fitzpatrick & Leavy, 2025; O’Dwyer et al., 2023; Rinke et al., 2016). Many universities require certain courses to ensure prospective teachers meet licensure requirements, and such requirements may lag behind trends towards STEM integration. In fact, research shows how courses for prospective teachers in single disciplinary areas, like mathematics, continue to lag behind the field’s recommendations for preparing primary teachers (Garner et al., 2024). Thus, we can expect that the more comprehensive programmatic changes suggested by research (Shernoff et al., 2017) might be less feasible. Yet, teachers/educators have the potential to be subversive and/or responsive to schools’ emerging needs in their pedagogical and curricular choices within existing required courses, opting to teach within an iSTEM framework rather than maintaining traditional disciplinary boundaries. This approach allows institutions to embrace iSTEM education while working within existing programmatic constraints.

Across the course-level approach, we saw several practices that have shown promise for preparing primary teachers for iSTEM education. Specifically, Indiana University Southeast, learning opportunities related to developing STEM content knowledge, including knowledge and practices unique to integration, and designing units that support iSTEM learning. The development of such lesson planning practices can be especially important (Kim & Bolger, 2017; Rinke et al., 2016; Ryu et al., 2019). The course from Towson University offers a model for prioritizing application of iSTEM knowledge to authentic contexts, where primary teachers act as learners, which may support the dispositions necessary for iSTEM teaching. These kinds of opportunities can positively impact teachers’ instructional capacity (Wu et al., 2024) and may help address the need for pedagogical strategies that guide student inquiry into authentic problems (Ellebæk et al., 2025). Finally, Purdue University also provides a model for how small, more isolated revisions might meet the need for specific attention to engineering in primary teacher education identified in our review of the literature (Perwaiz & Asunda, 2025; Wieselmann et al., 2025). The Purdue program combines a specific course on iSTEM integration and a yearlong service commitment, in which prospective primary teachers collaborate with engineers to solve authentic community-based problems. This approach gives prospective primary teachers opportunities to experience iSTEM as learners during community service and to develop their capacity for iSTEM teaching in their coursework. These community-based experiences seemed especially promising for providing a model for iSTEM learning as outlined in our conceptual framework—namely one that facilitates social change through community collaboration.

Our study pointed to two approaches that primary teacher education might adopt to support substantial program redesign: (1) building from an initial disciplinary focus to an iSTEM approach; or (2) introducing iSTEM from the beginning of the program. Those programs that must necessarily have a disciplinary focus on methods courses could consider introducing more iSTEM courses later in the program, such as the ones available at Bridgewater State University. Science education courses offer a promising site for introducing iSTEM because learning standards have evolved to include engineering in the United States. Opportunities for primary teachers to bridge science and engineering to address authentic problems can naturally shift the focus from multidisciplinary to iSTEM teaching. Moreover, including a programmatic structure that emphasize iSTEM, such as a concentration area of study (e.g., iSTEM Concentration at Purdue University; STEM education at Bridgewater University), area of interest (STEM at Southern Methodist), or minor (STEM discipline at Towson), was common across this case study. This suggests that creating opportunities (or requirements) to specialize in iSTEM can support the shift from a single-discipline to an iSTEM emphasis in primary teacher preparation.

For those programs looking to weave iSTEM throughout the teacher education experience, analysis of programs at Southern Methodist University and Point Park University highlights the potential for makerspaces as promising sites for teacher learning. The descriptions of both programs suggest that leveraging makerspaces as a cornerstone for iSTEM primary teacher education can support the development of knowledge and theory as well as practices related to both iSTEM teaching and learning. In the makerspace, teachers had an opportunity to experience iSTEM as learners, helping support dispositions for iSTEM teaching. Moreover, the makerspace served as a context for engaging teachers in the instructional design aspects that bridge knowledge and practice, from preparation through implementation and evaluation. Both of the programs providing a model for iSTEM teacher preparation are offered at the graduate level; therefore, the extent to which these programs can serve as a model for initial licensure or undergraduate programs is limited. The fact that Point Park University’s program is comprised of a four-course sequence leading to an endorsement shows promise as a model for undergraduate programs who are seeking to add an advanced specialization or concentration in iSTEM within an otherwise single-discipline-focused teacher education program.

Finally, in our findings from across programs with a more cohesive approach to iSTEM, we identified opportunities for primary teachers to connect iSTEM to other disciplines, such as literacy, art, history, and social sciences. Additional research and development is needed to understand how primary teachers conceptualize other multidisciplinary approaches, like iSTEAM, or how they see and make connections across all the subject areas they are responsible for teaching. iSTEAM presents new challenges for integrated teaching, and art is often integrated as an afterthought, meaning artistic components, such as drawing, coloring, etc., are simply added to STEM projects (Quigley et al., 2020). Teacher education for genuine iSTEAM, however, is an especially promising area for future research and development because iSTEAM can support students to pursue their interests through contextualized, connected, and collaborative learning (Quigley et al., 2020). Further, iSTEAM project-based learning has been found to facilitate student development in literacy, language, citizenship, socioemotional learning, and cultural expression, in addition to STEM content (Diego-Mantecon et al., 2021). Thus, integration of the arts can facilitate aspects of more equitable iSTEM learning, such as empathy and empowerment (Jackson et al., 2021; Figure 1). Depending upon the specific conception of art or the arts engaged, iSTEAM education can support social inclusion, community participation and a sustainability agenda (Colucci-Gray et al., 2019), helping to realize iSTEM’s full potential to foster sustainable and just social change.

Limitations

We recognize that this study has several important limitations to consider. First, because a global database of primary teacher education programs and their relation to STEM education does not exist, we needed to rely on an available database, which limited our focus to teacher preparation within the United States. We also wanted to maximize our chances of identifying programs redesigned to emphasize iSTEM teacher preparation, and the Noyce award database helped to identify promising teacher education programs for this case study. Nonetheless, the limited focus on the United States is important to consider because the push for iSTEM education in primary schools is global, and the gap between preparation for iSTEM teaching and the demand for it shapes implementation across the globe (e.g., Australia; Jones et al., 2025). We hope that any teacher educator who prepare teachers seeking to redesign courses or programs for iSTEM can draw on the approaches we described in this paper and use our findings to advocate for additional research and development in their local contexts.

Second, the claims we make in this study are limited because the data sources we used did not give us detailed information about the specific content of courses within programs. Because of this, we likely eliminated some programs from the case study because program and course descriptions suggested a disciplinary focus. For example, two programs we included in the study had program descriptions that did not describe iSTEM, but the course syllabi provided evidence of preparing teachers for iSTEM. The inverse is likely true; we may have interpreted some course descriptions as incorporating iSTEM, but syllabi might reveal a disciplinary or multidisciplinary approach. Syllabi, however, are rarely publicly available or may be outdated (Garner et al., 2024). Moreover, we found it difficult to gain access to course syllabi; only two Noyce project investigators responded to our request for syllabi. Our approach to using publicly available sources from university websites, however, gave some insights into programmatic features and structures to support iSTEM teacher preparation. Future research, however, could build upon these initial insights by either collecting additional course syllabi for analysis or by analyzing a more representative sample of primary teacher education programs (cf. Garner et al., 2024).

5. Conclusions

Given the growing need for primary teachers prepared to teach iSTEM, this study provides timely and relevant insights into the current landscape of iSTEM teacher education in the United States and points to themes that can guide the development of additional programs. Additionally, the conceptual framework presented in this article offers one way of bridging theory and research on iSTEM teaching and teacher education with theory and research on iSTEM learning. Teacher educators and researchers seeking to develop and study the (re)design of teacher education initiatives to center iSTEM may find this framework useful. Overall, the framework and our findings suggest the need for increased opportunities for primary teachers to experience iSTEM as the application of a unique set of knowledge and practices to solve authentic problems in both their own learning and in their development of instructional design practices. We offered details of different approaches that might guide program revisions, from small, course-level changes to overall program redesign. Leveraging the most feasible approach to reframe primary teacher education presents one way of supporting iSTEM education that realizes the full potential for developing future generations’ capacity to address complex issues in just and sustainable ways.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.R.-J. and F.K.H.; Methodology, F.K.H.; Formal analysis, D.R.-J., F.K.H.; Data curation, D.R.-J.; Writing—original draft, D.R.-J., F.K.H. and C.L.B.; Writing—review and editing, D.R.-J., F.K.H. and C.L.B.; Supervision, F.K.H.; Project administration, F.K.H. and C.L.B.; Funding acquisition, F.K.H. and C.L.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

U.S. National Science Foundation, 2243317.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| STEM | Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics |

| iSTEM | Integrated Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics |

| NGSS | Next Generation Science Standards |

References

- Alhassan, A. (2025). Integrated STEM education for in-service K-5 elementary teachers: Definitions, self-efficacy, and teaching practices [Doctoral dissertation, East Tennessee State University]. Available online: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/4586 (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Bartels, S. L., Rupe, K. M., & Lederman, J. S. (2019). Shaping preservice teachers’ understandings of STEM: A collaborative math and science methods approach. Journal of Science Teacher Education, 30(6), 666–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carley, K. (1990). Content analysis. In R. E. Asher, & J. M. Y. Simpson (Eds.), The encyclopedia of language and linguistics (Vol. 2, pp. 725–730). Pergamon. [Google Scholar]

- Colucci-Gray, L., Burnard, P., Gray, D., & Cooke, C. (2019). A critical review of steam (science, technology, engineering, arts, and mathematics). In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education. Oxford University Press (OUP). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corp, A., Fields, M., & Naizer, G. (2020). Elementary STEM teacher education: Recent practices to prepare general elementary teachers for STEM. In C. C. Johnson, M. J. Mohr-Schroeder, T. J. Moore, & L. D. English (Eds.), Handbook of research on STEM education (pp. 337–348). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Diego-Mantecon, J.-M., Prodromou, T., Lavicza, Z., Blanco, T. F., & Ortiz-Laso, Z. (2021). An attempt to evaluate STEAM project-based instruction from a school mathematics perspective. ZDM—Mathematics Education, 53(5), 1137–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiFrancesca, D., Lee, C., & McIntyre, E. (2014). Where is the “E” in STEM for young children? Engineering design education in an elementary teacher preparation program. Issues in Teacher Education, 23(1), 49–64. [Google Scholar]

- Ellebæk, J. J., Larsen, D. M., & Auning, C. (2025). Teachers’ challenges in teaching integrated STEM: In light of PCK as an analytical lens. LUMAT: International Journal on Math, Science and Technology Education, 12(4), 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- English, L. D. (2016). STEM education K-12: Perspectives on integration. International Journal of STEM Education, 3(1), 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, M., & Leavy, A. (2025). Reciprocal interplays in becoming STEM learners and teachers: Preservice teachers’ evolving understandings of integrated STEM education. International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, B., Munson, J., Krause, G., Bertolone-Smith, C., Saclarides, E. S., Vo, A., & Lee, H. S. (2024). The landscape of US elementary mathematics teacher education: Course requirements for mathematics content and methods. Journal of Mathematics Teacher Education, 27(6), 1009–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hapgood, S., Czerniak, C. M., Brenneman, K., Clements, D. H., Duschl, R. A., Fleer, M., Greenfield, D., Hadani, H., Romance, N., Sarama, J., Schwarz, C., & VanMeeteren, B. (2020). The importance of early STEM education. In C. C. Johnson, M. J. Mohr-Schroeder, T. J. Moore, & L. D. English (Eds.), Handbook of research on STEM education (1st ed., pp. 87–100). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, C., Mohr-Schroeder, M. J., Bush, S. B., Maiorca, C., Roberts, T., Yost, C., & Fowler, A. (2021). Equity-oriented conceptual framework for K-12 STEM literacy. International Journal of STEM Education, 8(1), 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M., Geiger, V., Falloon, G., Fraser, S., Beswick, K., Holland-Twining, B., & Hatisaru, V. (2025). Learning contexts and visions for STEM in schools. International Journal of Science Education, 47(3), 337–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D., & Bolger, M. (2017). Analysis of Korean elementary pre-service teachers’ changing attitudes about integrated STEAM Pedagogy through developing lesson plans. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 15(4), 587–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, C.-J., Lin, K.-Y., Kwon, H., & Kelley, T. R. (2025). A Six-stage instructional design model for collaborative implementation of integrated STEM education. Journal of Technology Education, 36(2), 25–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M. Y., & Lee, J. S. (2025). Project-based learning as a catalyst for integrated STEM education. Education Sciences, 15(7), 871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, O., & Grapin, S. E. (2025). STEM education with a focus on equity and justice: Traditional approaches, contemporary approaches, and proposed future approach. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 62, 2255–2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesseig, K., Nelson, T. H., Slavit, D., & Seidel, R. A. (2016). Supporting middle school teachers’ implementation of STEM design challenges. School Science and Mathematics, 116(4), 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lina, S. I., Johar, R., & Anwar. (2025). The role of mathematics education in shaping sustainable futures: A systematic literature review. Jurnal Elemen, 11(3), 757–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maass, K., Geiger, V., Ariza, M. R., & Goos, M. (2019). The role of mathematics in interdisciplinary STEM education. ZDM—Mathematics Education, 51(6), 869–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, T. P., & Mancini-Samuelson, G. J. (2012). Graduating STEM competent and confident teachers: The creation of a STEM certificate for elementary education majors. Journal of College Science Teaching, 42(2), 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- Mustafa, N., Ismail, Z., Tasir, Z., & Mohamad Said, M. N. H. (2016). A meta-analysis on effective strategies for integrated STEM education. Advanced Science Letters, 22(12), 4225–4288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Science Foundation. (2022, October 19). Improving undergraduate STEM education: Directorate of STEM education (IUSE: EDU). U.S. National Science Foundation. Available online: https://www.nsf.gov/funding/opportunities/iuse-edu-improving-undergraduate-stem-education-directorate-stem (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- National Science Foundation. (2023, May 8). Robert Noyce teacher scholarship program. U.S. National Science Foundation. Available online: https://www.nsf.gov/funding/opportunities/robert-noyce-teacher-scholarship-program (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- O’Dwyer, A., Hourigan, M., Leavy, A. M., & Corry, E. (2023). “I Have Seen STEM in Action and It’s Quite Do-able!” The impact of an extended professional development model on teacher efficacy in primary STEM education. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 21(S1), 131–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., Moher, D., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … McKenzie, J. E. (2021). PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perwaiz, F., & Asunda, P. (2025). Teachers’ instructional practices and students’ responses in middle school integrated STEM learning environments. Journal of STEM Education, 26(2), 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pynes, D., Kloser, M., Wagner, C., Szopiak, M., Wilsey, M., Svarovsky, G. N., & Trinter, C. (2025). Bridging theory and practice: A framework for STEM teacher leadership. School Science and Mathematics, 125(4), 330–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quigley, C. F., Herro, D., Shekell, C., Cian, H., & Jacques, L. (2020). Connected learning in STEAM classrooms: Opportunities for engaging youth in science and math classrooms. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 18(8), 1441–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radloff, J., & Guzey, S. (2016). Investigating preservice STEM teacher conceptions of STEM education. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 25(5), 759–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinke, C. R., Gladstone-Brown, W., Kinlaw, C. R., & Cappiello, J. (2016). Characterizing STEM teacher education: Affordances and constraints of explicit STEM preparation for elementary teachers. School Science and Mathematics, 116(6), 300–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchey, T. (2013). Modelling social messes with morphological analysis. ActaMorphologicaGeneralis, Swedish Morphological Society, 2(1), 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, M. A., Carter, V., Brown, J., & Shumway, S. (2017). Status of elementary teacher development: Preparing elementary teachers to deliver technology and engineering experiences. Journal of Technology Education, 28(2), 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, M., Mentzer, N., & Knobloch, N. (2019). Preservice teachers’ experiences of STEM integration: Challenges and implications for integrated STEM teacher preparation. International Journal of Technology and Design Education, 29(3), 493–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savery, J. R. (2006). Overview of problem-based Learning: Definitions and distinctions. Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-Based Learning, 1(1), 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shernoff, D. J., Sinha, S., Bressler, D. M., & Ginsburg, L. (2017). Assessing teacher education and professional development needs for the implementation of integrated approaches to STEM education. International Journal of STEM Education, 4(1), 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, D. L., & LoFaro, K. P. (2020). Sources of engineering teaching self-efficacy in a STEAM methods course for elementary preservice teachers. School Science and Mathematics, 120(4), 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieselmann, J. R., Menon, D., Price, B. C., Johnson, A., Asim, S., Haines, S., & Morison, G. (2025). What is STEM? Preservice elementary teachers’ conceptions of integrated STEM education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 165, 105108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X., Yang, Y., Zhou, X., Xia, Y., & Liao, H. (2024). A meta-analysis of interdisciplinary teaching abilities among elementary and secondary school STEM teachers. International Journal of STEM Education, 11(1), 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R. K. (2009). Case study research: Design and methods. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y., & Zhu, J. (2022, June 26–29). A review of research on STEM preservice teacher education. 2022 ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition Proceedings, Minneapolis, MN, USA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).