Abstract

A positive learning environment is related not only to student outcomes but also to inclusion of diverse learners. Although the literature on inclusive learning environments depicts physical and sensory elements as relevant, there is a need to improve measurements to include not only objective measures but also end users’ valuations of these elements. This study sought to construct and validate the Physical and Sensorial Classroom Environment Scale (PSCES) and understand, from teachers’ perspectives, the associations between classroom environment and inclusive educational indicators of autistic students in Chilean mainstream schools. The instrument’s validation process involved expert judges, a pilot test, and exploratory factor analysis with 197 Chilean teachers and education professionals. The second phase examined the relationship between physical and sensory classroom environment and indicators of inclusive education—permanence in classroom, social interaction, learning progress, classroom well-being, and sense of belonging—among 123 autistic students in the first to fourth grade in mainstream schools. Results showed that the 34-item scale showed excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.945, McDonald’s ω = 0.936), with seven factors explaining 61% of the total variance. A significant positive correlation (r = 0.487, p < 0.001) was found between better classroom conditions and improved educational inclusion, suggesting that as the factors measured by the scale increased, the overall perception of inclusion also increased. The coefficient of determination (R2 = 0.312) indicated that about 31% of variability in teachers’ perceptions of autistic educational inclusion was explained by classroom environment factors, particularly student agency and personalization, alternative arrangements, spatial organization, and sensory conditions. This study contributes to understanding how the physical and sensory classroom environment can foster educational inclusion for all learners, particularly for diverse autistic learners.

1. Introduction

Inclusive education is a core part of promoting the right to education and constitutes one of the Sustainable Development Goals of the 2030 Agenda (UNESCO, 2016). Countries, therefore, are expected to progress toward developing educational systems that increase participation for all students while reducing exclusion and discrimination (Booth & Ainscow, 2015). From an inclusive education approach, it is essential to establish mechanisms that promote better learning and academic progress conditions in all schools, so that school leaders and classroom teachers can foster improved learning, participation, and engagement for all learners—ensuring that all learners matter and they matter equally (Ainscow, 2025).

In this context, the physical learning environment is a key factor that educational communities can manage to create inclusive schools for diverse learners. The physical learning environment has been recognized as a crucial element in the complex and highly contextualized nature of learning, potentially influencing learning outcomes, participation, and perceptions of well-being and comfort in the educational community (Baars et al., 2021; Barrett et al., 2015; Byers et al., 2018; OECD, 2017c). The classroom’s physical environment includes various spaces where teaching and learning take place, covering aspects such as available space, ventilation, lighting, furniture arrangement, links with nature, accessibility, and circulation patterns, among others—facilitating learning experiences through collaboration and student empowerment (Suraini & Aziz, 2023).

It is important to highlight that the physical learning environment is not considered an isolated element; rather, the current trend is to understand it from a psychosocial and physical relational approach that sees people and their physical environment as a unit, constantly interacting with each other (Baars et al., 2023). For this reason, the physical aspects of learning environments are considered essential from an inclusive perspective. This has been widely recognized as a key element that supports inclusive education and equity (Heinz et al., 2025; Suraini & Aziz, 2023), through providing accessible learning materials and resources; creating safe, friendly, and inclusive environments; and promoting student engagement, participation, learning, and the progress of all students (UNESCO, 2023).

1.1. Physical and Sensory Characteristics of Learning Environments

A comprehensive literature review was conducted using academic databases including Web of Science, SCOPUS, ERIC, and EBSCO. The search strategy combined the following keywords using Boolean operators (AND and OR): “physical learning environment”, “sensory learning environment”, “scales”, “inclusive education”, and “autism.” The search was limited to publications from 2000 to 2024. The primary objective of this review was to identify physical and sensory characteristics of learning of classroom environments that, according to the international literature, are relevant for inclusive education, particularly for autistic students. In addition, established instruments designed to assess general aspects of learning environments were examined. This comprehensive literature review yielded the following five central and conceptually different dimensions of the physical and sensorial characteristics of learning environments.

1.1.1. Sensory Environmental Conditions and Infrastructure

A substantial body of research has linked various physical characteristics of classrooms to students’ satisfaction with their overall school experience. Building conditions—such as lighting, noise levels, temperature, comfort, air quality, and even classroom odors—have been shown to influence academic performance, general school satisfaction, and students’ attitudes toward learning (Barrett et al., 2015; Byers et al., 2018; Chang & Fisher, 2003; Han et al., 2019; Young et al., 2003).

Barrett et al. (2015) emphasized that physical conditions, including visual, thermal, and acoustic factors, directly affect human comfort, positioning them as essential elements for promoting well-being in educational settings. Additionally, school infrastructure and adequate maintenance are critical for sustaining supportive learning environments. For example, the proper upkeep of windows, doors, and desks has been associated with increased perceptions of safety, improved student behavior (Plank et al., 2009), and even measurable impacts on academic outcomes (Barrett et al., 2018; Espinosa-Andrade et al., 2024; Fisher, 2000). This issue is particularly salient in the Chilean context, where many public schools face considerable infrastructure deficits, which may hinder both learning and inclusion efforts (OECD, 2017a).

1.1.2. Spatial Organization and Furniture

Spatial attributes such as the arrangement of furniture and overall classroom configurations have been closely associated with students’ levels of participation (Marx et al., 1999; Roskos & Neuman, 2011), visibility, and capacity to maintain clear visual access to instructional materials. Cardellino et al. (2017) found that at a distance of 5 m from the front of the classroom, students’ visual and auditory interaction with the teacher declines by approximately 70%. Moreover, deep or rectangular classroom shapes often result in low-interaction zones, which can negatively affect both student engagement and the quality of learning. Flexible classroom designs—those that allow students to manage furniture configurations and workspaces—have been associated with improved social cohesion, collaboration, and teamwork among students (Sasson et al., 2021).

Classroom furniture, particularly chairs and desks, should be understood as not only functional objects but also mediators and agents in the learning process. Depending on its arrangement, furniture can either facilitate or restrict student movement and interaction. In certain contexts, it may also operate as a discipline dispositive by reinforcing specific bodily postures and school behaviors (Angulo de la Fuente, 2024). From an inclusive education perspective, learning environments that incorporate flexible furniture—characterized by diverse seating options and surfaces, ease of reconfiguration, mobility, and adaptability to students’ preferences—have been shown to support greater student engagement and participation, including higher levels of school well-being and a reduction in mental health problems (Bluteau et al., 2022).

1.1.3. Classroom Size and Movement

The overall size of the classroom and space available per student are closely connected to opportunities for movement, circulation patterns, and the general sense of satisfaction reported by both students and teachers. Özyildirim (2021) found that when classroom space is perceived as insufficient, teachers report greater fatigue and reduced satisfaction and well-being. Tanner (2009) emphasized the importance of classroom movement and circulation—defined as spatial conditions allowing students and teachers to move freely without feeling confined—to promoting student well-being. Similarly, Castilla et al. (2017) argued that opportunities for movement in the classroom positively affect students’ social interactions and cooperation, ultimately influencing their perceived well-being. Bedard et al. (2019) demonstrated that physically active classrooms, which allow for student mobility, are associated with greater enjoyment and improved school-related well-being. Consistent with these findings, Van Delden et al. (2020) observed that students permitted to stand or adopt alternative postures reported greater satisfaction than those required to remain seated for most of the school day. This issue holds particular significance in the Chilean context, where primary school classrooms are among the most crowded in OECD countries, with an average of 30 students per room (OECD, 2017a). Consequently, the average classroom space per student is approximately 1.2 m2, substantially below the OECD recommendation of 2 m2 (Ministerio de Educación de Chile, 2017).

1.1.4. Student Agency and Classroom Personalization

Students are aware of the physical characteristics of their learning environments, even at an early age, and capable of suggesting modifications to improve their learning environment, highlighting the importance of developing environments with a student-centered perspective (Nyabando & Evanshen, 2022; Young et al., 2003).

Barrett et al. (2015) highlighted the principle of individualization, asserting that classrooms adapted to the specific needs of a particular group of learners can enhance educational outcomes. This concept is operationalized through personalization actions to foster students’ sense of ownership over the learning environment. Some studies reported that when students have a higher degree of participation in the classroom, they are also more involved in school activities. For example, Travis (2017) identified significant differences in student engagement between classrooms where students were allowed to select their seats and those with assigned seating. Allen (2018) further investigated this phenomenon, finding that student-selected seating was associated with higher levels of attention, fewer teacher redirections, and increased participation in academic tasks.

1.1.5. Comfortable and Aesthetic Classroom Environment

According to Barrett et al. (2015), this dimension encompasses the aesthetic and structural complexity of the physical environment, which should encourage students to explore, experiment, and exchange ideas. Aesthetic quality is considered a critical factor in creating a sense of balance and order in complex learning spaces. A warm and comfortable classroom environment has been associated with higher levels of student satisfaction and overall well-being (Castilla et al., 2017).

1.2. Physically and Sensorially Enabling Classrooms for Autistic Students in Mainstream Classrooms: What Does It Look Like?

The international literature suggests that the physical and sensory characteristics of classroom environments can serve as both barriers and facilitators of learning, participation, and well-being for autistic students. The concept of barriers and facilitators has been used in the field of inclusive education, referring to how culture, policies and school practices—when interacting with the personal, social, or cultural conditions of specific student groups—can lead to exclusion, marginalization, or academic failure (Ainscow, 2025; Booth & Ainscow, 2015; Echeita & Ainscow, 2011). This concept focuses on the different contexts in which people operate and interact, explaining how these complex interactions shape restrictions on participation. This understanding arises from changes in the field of disability studies, highlighting the importance of considering people’s social and cultural contexts rather than a narrow view of deficits or limitations.

The literature depicts the physical and sensory characteristics of what could be defined and operationalized as an inclusive classroom suitable for autistic students in mainstream classrooms. We present these characteristics, organized according to the five aforementioned conceptual dimensions regarding the physical and sensory elements of learning environments.

1.2.1. Sensory Environmental Conditions and Infrastructure for Autistic Students

Concerning autistic students, several studies have indicated that the sensory characteristics of environments can affect emotional regulation and concentration, generate discomfort or sensory overload, or interfere with the processing of information necessary for effective participation in school activities (Ashburner et al., 2013; Butera et al., 2020; Gentil-Gutiérrez et al., 2021; Kaundinya & Kaku, 2025; Rajotte et al., 2024; Whiting et al., 2021; Wood & Happé, 2023).

Regarding visual information, from an autism-inclusive education perspective, elements such as color and visual information in the classroom are not merely decorative; rather, they function as pedagogical and spatial tools for orientation. However, some classrooms with high levels of visual stimulation from direct light, bright light, excessive decoration, or visual clutter can produce overstimulation for autistic tudents, which can generate discomfort and negative emotions (Ashburner et al., 2013; Saggers et al., 2016; Zazzi & Faragher, 2018). Accordingly, it is recommended to minimize unnecessary visual stimuli and provide designated spaces that support sensory self-regulation (Martin & Wilkins, 2022), such as using pale colors on walls, dimming lights, and ensuring they are softer and less glaring (Fitri et al., 2025), and installing darkening curtains (Williams et al., 2024). Reducing visual overstimulation may enhance students’ attention and focus (Gaines & Curry, 2011; Martin & Wilkins, 2022).

Another factor relevant to autism is the need for appropriate temperature conditions. Marzi et al. (2025) reported that in environments with temperatures around 28 °C, performance on attention tasks was significantly poorer than under optimal conditions (24 °C), suggesting that elevated temperatures can act as a stressor. Such conditions may even lead to an increase in motor stereotypies and echolalia.

Regarding excessive noise, because some autistic individuals may exhibit high sensitivity to loud sounds (Khalfa et al., 2004), excessive noise can disrupt attention and behavior, constituting another critical dimension (Howe & Stagg, 2016). Classroom noise originates from multiple sources, both internal and external (Guo et al., 2024). Although the World Health Organization recommends maintaining noise levels below 35 dB indoors and 55 dB in outdoor areas (Berglund et al., 2002), empirical studies have recorded classroom noise levels ranging from 45 to 80 dB (Sundaravadhanan et al., 2017). Kanakri et al. (2016, 2017) reported that more than 95% of teachers observed students with autism covering their ears in response to bothersome noises, and levels exceeding 70 dB are associated with increased disruptive behaviors. In this context, González de Rivera et al. (2022) emphasized that noisy environments constitute a barrier to inclusion; therefore, the use of environmental modification such as sound-absorbing materials (e.g., carpets, panels), quiet zones (Fitri et al., 2025), and architectural designs that reduce noise and reverberation is recommended (Dargue et al., 2022; Shield et al., 2015).

1.2.2. Spatial Organization for Autistic Students

Regarding spatial organization as a facilitator, it is important to organize classroom spaces intuitively and understandably, establishing clear pathways and functional, manageable compartments that reduce anxiety and information overload, and furniture arrangements in the shape of a horseshoe or semicircle to promote social interaction (Fitri et al., 2025; Ghazali et al., 2021; Mostafa et al., 2024). Storage bins are particularly advantageous for enhancing learning environments for autistic students (Mostafa et al., 2024). Providing diverse and flexible spaces in the classroom has also been reported as a possible facilitator for autistic students. Mostafa et al. (2024) indicated that the benefits of designing scape spaces for sensorial regulation can provide emotional security. Incorporating quiet or silent zones, or compartmentalized areas in the classroom where students can retreat when feeling overwhelmed (Fitri et al., 2025; Ghazali et al., 2021), and allowing for pedagogical work in different postures can respond to the movement needs of autistic students (Saggers & Ashburner, 2019).

1.2.3. Furniture for Autistic Students

Research on furniture as school inclusion facilitators for autistic students has indicated that the use of alternative or flexible seating (stability ball seats, air cushions) can provide the necessary sensory stimulation to maintain optimal alertness (arousal states), facilitating attention levels, on-task behavior, appropriate seat behavior, and reduced self-stimulatory or disruptive behaviors (Brennan & Crosland, 2021; Krombach & Miltenberger, 2020; Matin Sadr et al., 2017; Schilling & Schwartz, 2004). Other studies suggested that furniture types should expand to include vestibular and proprioceptive stimulation, such as bounce chairs, swings, and yoga slings for hammocks (Mostafa et al., 2024).

1.2.4. Classroom Size and Movement for Autistic Students

With respect to the spatial environment and differences in proxemic perception, autistic students may need greater interpersonal distance to feel comfortable (Fusaro et al., 2023; Saggers et al., 2016). In Chile, classrooms with sufficient space and low student density have been associated with facilitating the provision of personalized support for autism people (Martinez et al., 2023; Villegas Otárola et al., 2014). Environmental modifications such as the arrangement of desks and chairs to reduce crowding and ensure personal space among students can result in a lower level of anxiety and greater concentration among autistic students (Fitri et al., 2025).

1.2.5. Other Classroom Characteristics for Autistic Students

There is a lack of scientific evidence in the international literature regarding student agency, personalization, aesthetics, and comfort regarding the classroom environment for autistic students.

1.3. Autistic Students in the Chilean School System

The Chilean state has developed an inclusive education framework that considers the well-being, participation, and full development of all students. It is based on the recognition and equality of all people, dignity and rights, respect for differences, and the appreciation of each member of an educational community, regardless of their characteristics or conditions (Ministerio de Educación de Chile, 2023).

One group that has seen the most significant increase in enrollment in the education system is autistic students. Although there are no updated data available for 2025 regarding the enrollment of autistic students, previous reports indicated that Chilean education system has at least 70,051 autistic students enrolled in various modalities and schools funded by the government (Ministerio de Educación de Chile, 2023), with an increase of 300.4% in the period from 2019 to 2023, going from 11,877 students to 47,551 in 5 years (Ministerio de Educación de Chile, 2024).

Although the increasing enrollment of autistic students in mainstream schools may represent progress in the realization of their right to education, it does not guarantee their full participation in school life or meaningful advancement in their educational trajectories. Various studies have shown that autistic students often perceive their well-being in school as significantly lower compared to their peers (Danker et al., 2019; Haug, 2019). They have reported frequently experiencing negative school experiences, high rates of social exclusion and bullying, low levels of peer support, lack of support and understanding from teachers, and perceptions of the sensory school environment as overwhelming. (González de Rivera et al., 2022; Goodall, 2018, 2019; Lynam et al., 2024).

The government of Chile enacted Autism Law No. 21,545 (República de Chile, 2023), which aims to strengthen inclusion measures in education, stating that the state must ensure and create the necessary conditions for the access, participation, retention, and progress of autistic students in school settings. However, according to reports from the Chilean Superintendence of Education for the 2022–2024 period, complaints related to the discrimination and mistreatment of autistic students in preschool and primary schools rank first among all reported issues, with the highest concentration in primary education (59% in 2024; Superintendencia de Educación, 2025). These data highlight the persistence of negative schooling experiences among autistic students in Chile, suggesting that many continue to learn in environments that fall short of inclusive education principles.

In this context, these reports can be interpreted as evidence of gaps between the requirements established by the autism law and the actual conditions experienced in schools. The enactment of this legislation underscores the urgent need to improve conditions that enable inclusion, not only from pedagogical or attitudinal perspectives but also in relation to the physical and sensory characteristics of classrooms.

1.4. Rationale for the Study

This research focused on understanding the extent to which school environments—particularly their physical and sensory aspects—align with the inclusion principles promoted by the autism law and how these aspects may facilitate or hinder inclusion of autistic students in mainstream school settings. This gap is partly due to a lack of scientific evidence regarding which elements of the physical and sensorial learning environment in the Latin American context are associated with and therefore more relevant for a positive experience of educational inclusion among all stakeholders, including teachers.

The overall purpose of this study was to explore, from the teachers’ perspectives, the relationship between the features of the physical and sensory classroom environment and the ways in which these may configure barriers or facilitators for the educational inclusion of autistic primary school students, with a focus on their potential to support inclusive education.

The first step was to identify existing instruments capable of assessing the physical and sensory characteristics of classroom environments. A review of current instruments revealed two critical gaps. First, no available scale comprehensively integrates the physical and sensory elements identified in the literature as essential for the inclusion of autistic students, such as organized visual information, opportunities for movement, flexible and varied seating options, mechanisms for ownership of the physical spaces, students’ seat decisions, and personalization. Second, instruments have failed to reflect the lived experiences and structural challenges characteristic of Latin American educational systems, particularly Chile’s public schools, which often face infrastructure limitations, overcrowded classrooms, shared spaces across grade levels, and limited funding for the implementation of innovative learning environments.

Because there were no other Latin American instruments in this field, Phase 1 of the study sought to fill this gap by developing and validating a scale capable of assessing teachers’ perceptions of the physical and sensory conditions of their classrooms.

2. Materials and Methods

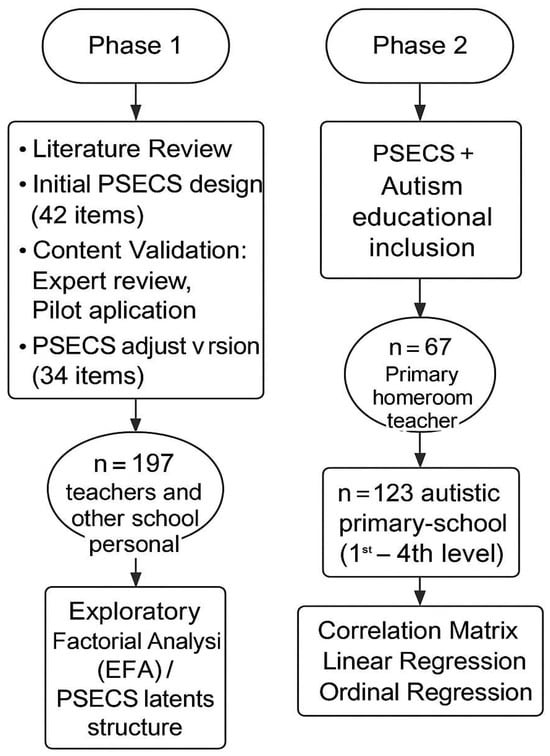

This study adopted a quantitative research approach, structured in two sequential phases. Phase 1 employed an instrumental design to develop and validate a scale, named the Physical and Sensory Classroom Environment Scale (PSCES). Phase 2 involved a predictive design to test the explanatory power of the scale in understanding the relationship between the physical and sensory characteristics of the classroom environment and educational inclusion of autistic students in Chilean mainstream classrooms (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study design.

We constructed the scale for physical and sensory classroom environment based on the conceptual framework of the physical learning environment proposed by Barrett et al. (2015), the OECD Teaching and Learning International Survey on learning environments (OECD, 2017b), and the OECD School User Survey: Improving Learning Spaces Toguether (OECD, 2018). Furthermore, items from the Classroom Climate Scale, developed by JUNAEB (2019) and validated by López et al. (2018), were reviewed, given its use in the Chilean public school system to monitor school climate. Concepts and items consistent with the aims of this study were selected and adapted to align with the focus on the physical and sensory dimensions of inclusive learning environments.

The educational inclusion of autistic students was conceptualized and measured following Index for Inclusion (Booth & Ainscow, 2015), conceptualized by Echeita et al. (2013), and the Chilean Inclusive Education Framework (Ministerio de Educación de Chile, 2023), with five interrelated aspects of school inclusion: staying and having permanence in the classroom, participating and engaging with peers, feeling a sense of belonging to the group, learning progress, and well-being in the classroom.

2.1. Content Validation

The initial version of the PSECS had 42 items. To assess content validity, a two-phase validation process was implemented. In the first phase, construct validation interviews were conducted with two elementary school teachers, who reviewed the initial set of items and provided qualitative feedback regarding clarity, relevance, and alignment with real classroom experiences. Their input contributed to the refinement of item wording and structure. In the second phase, the revised scale was evaluated by three academic experts in the fields of psychology and education, who acted as content judges. They assessed the instrument in terms of clarity, relevance, appropriateness, and feasibility and offered suggestions for improvement. Based on their recommendations, seven items were removed, resulting in a refined version of the scale with 35 items. Finally, a pilot test was conducted with five education professionals, who completed the survey and provided additional feedback to enhance the clarity and wording of the items. Following this stage, minor adjustments were made, and the final version of the instrument consisted of 34 items. Table 1 presents the variables considered in the design of the scale. Complete descriptions and conceptual definitions are provided in Appendix A.

Table 1.

Items and classroom statements.

To evaluate the indicators of inclusive education, from teachers perceptions,, we used the conceptual framework by Echeita et al. (2013) and interpreted inclusive education according to the Index for Inclusion (Booth & Ainscow, 2011, 2015), as detailed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Inclusion conceptual definitions and educational inclusion wording of autistic students (Booth & Ainscow, 2011, 2015; Echeita et al., 2013).

2.2. Participants

2.2.1. Phase 1: PSCES Validation

A nonprobabilistic snowball sampling method was employed for this phase of the study. The inclusion criteria were education professionals—teachers or education assistants (school psychologists, occupational therapists, speech therapists, special educators, and others) currently employed in Chilean educational institutions, whether public, subsidized private, or fully private, and across various modalities (mainstream, special, or rural schools). Professionals working in higher education or university settings were excluded from the study.

Education professionals were included in this phase because, for the validation process, it was necessary to obtain a broad perspective on the classroom environment. In the Chilean school system, education professionals such as occupational therapists, school psychologists, speech therapists, and special educators usually provide in-class support in mainstream classrooms, which gives them a deep understanding of the physical and sensory characteristics of these settings.

The final sample consisted of 197 education professionals, representing a broad geographical distribution. The largest groups were from Santiago (n = 74, 37.6%), Valparaíso (n = 72, 36.6%), and O’Higgins (n = 34, 17.3%). Other participants were from the Biobío (n = 5), Atacama (n = 3), Aysén (n = 1), Coquimbo (n = 1), Iquique (n = 2), Los Lagos (n = 2), Maule (n = 1), and Ñuble (n = 1) regions. Most participants identified as female (n = 170, 86.3%), followed by male (n = 22, 11.2%). A small group identified as LGBTQ+ (n = 2, 1.0%), and some preferred not to disclose their gender (n = 3, 1.5%). Regarding participants’ ages, 40.1% were between 36 and 45 years old, 25.9% were between 26 and 35, a small group was younger than 25 (1.5%), and 1.0% were older than 65. Most participants worked in public schools (n = 141, 71.6%), followed by subsidized schools (n = 45, 22.8%) and private schools (n = 11, 5.6%). In terms of professional background, elementary teachers being the most common (n = 92, 46.7%), followed by special education teachers (n = 42, 21.3%) and occupational therapists (n = 25, 12.7%).

2.2.2. Phase 2: PSCES and Inclusive Educational Indicators of Autistic Students

To explore the relationship between PSCES and indicators of inclusive education for autistic students, a subsample of teachers was selected based on three criteria: (a) primary teachers (homeroom) of first- to fourth-grade classes, (b) working in a mainstream school, and (c) having at least one autistic student in their class.

This study focused on primary school teachers because early schooling represents a critical stage for the social and academic inclusion of autistic students and the first step in their educational trajectories. Moreover, in Chile, the first years of primary education have the highest rates of enrollment of autistic students in mainstream schools, making this level particularly relevant for analyzing the relationship between classroom environments and inclusion outcomes.

Each teacher reported on the inclusion status of at least one autistic student in their class. Teachers were advised to consider only students who had a formal diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder that was documented and supported by reports provided to the school. Additionally, they were asked to exclude students who were in the process of diagnosis or for whom there was no certainty about their diagnosis.

As a result, 67 teachers were selected for this second phase of analysis. Each teacher completed the PSCES survey and the inclusion indicators, indicating their level of agreement with each of the five premises related to school inclusion for their autistic students (Table 2). The teachers reported their perceptions of the inclusion variables for 123 autistic students in primary school, distributed across first grade (n = 24), second grade (n = 36), third grade (n = 29), and fourth grade (n = 34); from public schools (n = 104) or subsidized schools (n = 19); and from the central regions of Chile (Valparaiso, Metropolitan, and O’Higgins).

2.3. Data Collection and Analysis

The survey, administered via Google Forms, was widely shared through email and social media channels between November 2023 and June 2024. In Phase 1, participants were invited to contribute to the instrument validation process. In Phase 2, the study’s objectives were explained. Each respondent completed the scale by rating their level of agreement with statements related to their classroom environment and autism inclusion indicators using a 4-point Likert scale (0 = strongly disagree, 1 = disagree, 2 = agree, 3 = strongly agree). The five items of educational inclusion were averaged to create a composite index that represented the level of inclusion for each autistic student. For both (PSCES and inclusion autistic indicators), the arithmetic mean of the scores obtained for each item (0–3) or factor was used to facilitate comparisons between scales. This procedure allowed for the derivation of interpretable average values.

Exploratory factor analysis and additional statistical analyses were conducted using JAMOVI software version 2.6 “https://www.jamovi.org” (accessed on 9 July 2025 and JASP software version 0.95.3 “https://jasp-stats.org” (accessed on 11 July 2025).

2.4. Ethical Considerations

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the sponsoring university (Approval Code: BIOEPUCV-H 802-2024), and informed consent was obtained from all participants. Participants accessed the informed consent form online and indicated their agreement to participate by selecting the option “I agree to participate in this study.”

3. Results

3.1. Phase 1: PSCES Validation

3.1.1. Factor Structure of the Scale

To examine the latent structure of the constructed scale, Bartlett’s test of sphericity was conducted to assess whether the correlation matrix was suitable for factor analysis. The test yielded good results, χ2(561) = 2687, p < 0.001, indicating significant correlations among variables and supporting the suitability of the data for factor analysis. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy was calculated, resulting in an overall value of 0.866, with most items exhibiting individual Measure of Sampling Adequacy (MSA) values exceeding 0.80, further confirming the adequacy of the data for factor analysis.

Exploratory factor analysis was then performed using the parallel analysis method, combined with the minimum residual extraction method and oblimin rotation. We used a polychoric–tetrachoric correlation matrix to ensure that the psychometric evaluation of the scale aligned with current methodological recommendations for ordinal data (Baglin, 2014; Domínguez, 2014; Ferrando et al., 2022).

The rotated solution revealed seven factors, which collectively accounted for 63.1% of the total variance in the scale’s responses, suggesting a robust factor structure (see details in Table 3), providing a comprehensive understanding of the classroom’s physical environment.

Table 3.

Factor loadings and explained variance percentages.

Table 4 presents the grouping of items ordered by factor loadings. Items with low loadings (<0.30) were omitted, following the recommendations of Tabachnick and Fidell (2014) and Field (2013). The clustered items in each factor were carefully analyzed, leading to a theoretical interpretation of each factor.

Table 4.

PSCES exploratory factor analysis.

3.1.2. Conceptual Interpretation

Table 5 provides a comprehensive summary of the factors, items associated with each factor, proposed conceptual interpretations, and proposed factor names, considering the theoretical framework and conceptual organizing dimensions derived from the comprehensive literature review.

Table 5.

Summary of factors, items, conceptual interpretation, and proposed factor names.

3.1.3. Internal Consistency of the Scale

Cronbach’s alpha for the 34-item scale was 0.945, indicating high internal consistency (George & Mallery, 2003). McDonald’s omega was also high, at 0.946, further supporting the scale’s reliability. This means that all items measured the same general construct consistently (see Table 6).

Table 6.

Scale reliability statistics.

The mean overall scale was 1.71 (in 0–3 points). Table 7 presents reliability statistics for each item (means and standard deviations) and measures of central tendency for ordinal-appropriate descriptive statistics (mode, median), and corrected item–total correlations for each item. The item–total correlations were adequate and demonstrated a coherent internal structure. None of the items decreased reliability when removed, which supports the consistency and integrity of the scale. Consequently, it was not considered necessary to discard any items at this stage.

Table 7.

Item reliability statistics.

3.1.4. Descriptive Results of the Scale

Participants reported an average of 27 students per classroom, and 15.3% indicated that they shared the classroom with another class in alternating sessions. Descriptive statistics for item-level perceptions of education professionals are presented in Table 8, with a focus on the lowest- and highest-rated classroom items.

Table 8.

Low-rated and high-rated items.

Table 9 shows the emergent factor scale. Among the seven factors, Sensory Environment (Factor 7) obtained the lowest mean score, whereas the factor associated with Classroom Size and Movement (Factor 2) showed the highest mean. For all factors, the Shapiro–Wilk test yielded p-values less than 0.001, indicating a nonnormal distribution of the data.

Table 9.

Summary of PSCES factors.

3.2. Phase 2: PSCES and Inclusion of Autistic Primary School Students

3.2.1. Descriptive Results by Grade Level

The educational inclusion of autistic students was calculated based on the five previously defined variables (permanence in the classroom, social interactions, sense of belonging, learning progress, and classroom well-being). The level-by-level analysis (Table 10) showed that the average perception of inclusion gradually decreased from first grade ( = 1.99, SD = 0.49 to fourth grade ( = 1.59, SD = 0.76). The data suggest a slight decline in the perception of inclusion as students progress through the school levels, with increasing dispersion in the higher grades. The mode also reflects this pattern, decreasing from 2.20 in first grade to 1.60 in fourth grade.

Table 10.

Inclusion of autistic students per grade level.

The Kruskal–Wallis analysis conducted to compare the mean inclusion score among different education levels showed a χ2 value of 5.50 with three degrees of freedom and a significance level of p = 0.139, indicating that there were no statistically significant differences in the perception of inclusion among grade levels.

3.2.2. Descriptive Results by Dimension

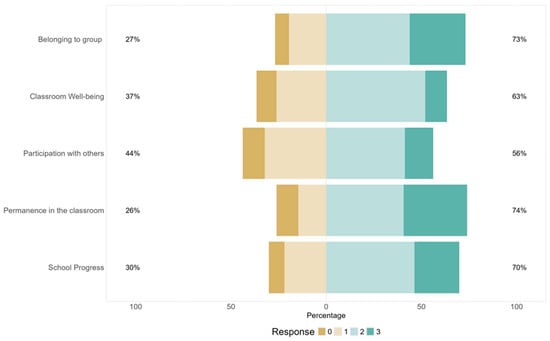

Table 11 presents the teachers’ perceptions regarding the level of inclusion of autistic students in mainstream primary classrooms, considering the five indicators previously conceptualized (Booth & Ainscow, 2011, 2015; Echeita et al., 2013).

Table 11.

Items measuring inclusion of autistic primary school students.

The results reflect mostly positive perceptions among primary school teachers regarding the inclusion indicators (Figure 2). Classroom permanence (74%, = 1.96), sense of belonging (73%, = 1.95), and learning progress (70%, = 1.85) received more responses in the higher levels of the scale (strongly agree and agree). In contrast, the items for well-being in the classroom (53%, = 1.64) and social interactions (63%, =1.60) received less agreement. These findings enable the identification of strengths and critical areas for designing inclusive strategies and practices at this level of education.

Figure 2.

Percentages of agreement and disagreement about teachers’ perceptions from the inclusion of autistic students.

The data exhibited negative skewness and kurtosis, indicating nonnormal distributions, as confirmed by the Shapiro–Wilk test (p < 0.001).

3.2.3. Relationship Between Teachers’ Perceptions About Inclusion of Autistic Students and Physical and Sensorial Classroom Aspects

To explore correlations between teachers’ perceptions of inclusion of autistic students and their classroom conditions, the Shapiro–Wilk test was applied to verify the univariate normality of (1) mean inclusion autism scores and (2) mean PSCES factors, resulting in p = 0.091, which supports the use of parametric correlation. The Pearson correlation yielded a coefficient of 0.487 (p < 0.001), indicating a moderate and significant positive relationship between the two variables.

This suggests that as the factors related to the PSCES increase, there is also an increase in the overall perception of autistic students. This finding highlights the importance of PSCES factors that are related to the educational inclusion experience.

3.2.4. Contribution of Physical and Sensory Aspects of the Classroom to Teachers’ Perception of Inclusion of Autistic Students in Mainstream Classrooms

A linear regression model was developed to analyze whether the PSCES factors can predict the inclusion of autistic primary school students. Hierarchical regression analyses were conducted (stepwise) to evaluate the contribution of the seven PSCES factors to students’ inclusion perceived by their teachers (see Table 12).

Table 12.

Regression model (stepwise method).

Model 0, which included only the intercept, did not explain variance in the dependent variable (R2 = 0.00, RMSE = 0.67). When sensory environment was added to Model 1, this factor showed a positive and significant effect (b = 0.471, p < 0.001), explaining 21.4% of the variance (adjusted R2 = 0.20) and reducing RMSE to 0.602.

Model 2, adding alternative arrangements and spatial organization, also proved significant (b = 0.32, p = 0.004), and the effect of sensory environment remained (b = 0.31, p = 0.003), increasing the explained variance to 27.6% (adjusted R2 = 0.26, RMSE = 0.58).

Model 3, which incorporated student agency and personalization (b = 0.28, p = 0.021), showed that all predictors had positive effects, although the significance of sensory environment was marginal (b = 0.21, p = 0.053). This model explained 31.4% of the total variance (adjusted R2 = 0.29, RMSE = 0.56), demonstrating that the combination of sensory conditions, spatial organization, and student agency and personalization significantly contributed to teachers’ perception of educational autism inclusion in the classroom.

Other factors of teacher satisfaction with aesthetics, comfort, and classroom conditions, classroom size and movement, infrastructure and environmental conditions, and furniture were not included in the final models because they did not provide additional significance in this sample.

In summary, Table 13 show thatthe three factors included in the model 3 predicted teacher’s perception of inclusion of autistic students explaining up to 31.4% of the total variance).

Table 13.

Model summary: PSCES and school inclusion.

3.2.5. Key PSCES Factors as Predictors of Inclusion of Autistic Primary School Students

Finally, ordinal regressions were performed to evaluate the effect of the PSECS factors on each inclusion variable (Table 14), allowing for the identification of the key PSCES factors that, in this research and from teacher’s perception appear relevant to the permanence, participation, sense of belonging, learning progress, and well-being of autistic students in mainstream classrooms and practical recommendations for teachers derived from these findings.

Table 14.

PSCES factors as predictors of the inclusion of autistic students.

The results showed that student agency, participation, and personalization (Factor 4) were positive and significant predictors across multiple dimensions: they promoted social interaction (b = 0.90, p = 0.042), learning progress (b = 0.99, p = 0.017), and the perception of being valued and recognized by peers (b = 1.10, p = 0.012). Meanwhile, sensory conditions were relevant for staying in the classroom (b = 1.10, p = 0.010), although they were not significant in other outcomes. Furniture negatively affected social interactions (b = −0.70, p = 0.023) and learning progress (b = −0.75, p = 0.016).

Other factors, such as infrastructure and environmental conditions, teacher satisfaction with aesthetics, comfort, and classroom conditions, classroom size and movement, and alternative arrangements and spatial organization, exhibited variable effects that were generally not significant, although some trended toward significance.

4. Discussion

The constructed scale demonstrated excellent internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha (0.945) and McDonald’s omega (0.936) both exceeding the recommended psychometric standards (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994). This statistical robustness supports the coherence of the items and stability of the construct being measured: teachers’ perceptions of the physical and sensory learning environment from an inclusive education perspective.

The exploratory factor analysis identified seven distinct factors, which together explained 63.1% of the total variance. These dimensions align with constructs reported in the international literature on physical and sensory learning environments, thus supporting the conceptual foundation of the scale. The multidimensional structure effectively captured the complexity of the construct and reflected the diverse elements that influence how teachers perceive the physical classroom environment and its impact on teaching, learning, and participation.

The study reinforced that the physical learning environment is not an isolated or unidimensional concept, but rather a complex, multidimensional construct closely tied to the educational experiences of both students and teachers. In this way, the research contributes to a multifactorial understanding of physical and sensory dimensions that act as barriers or facilitators of inclusive education, providing empirical evidence for the design of more supportive and adaptive school environments.

From a practical standpoint, teachers, stakeholders, and school management teams can draw on this finding to develop inclusive practices centered on classroom environmental agency to promote context-specific transformation and continuous improvement actions. Such practices can strengthen the implementation of inclusive approaches and promote the participation and well-being of all students.

This aspect is particularly relevant in the current educational context, in which the implementation of inclusive education policies across countries has led to a substantial increase in the proportion of teachers working in schools with diverse student populations. According to the OECD (2025), the percentage of teachers working in schools where more than 10% of students have special educational needs rose from 30% in 2018 to 45% in 2024, underscoring the growing need for systemic adaptation and professional support in educational institutions.

4.1. Overall PSCES Results

The analysis of item-level responses revealed critical contrasts in teachers’ perceptions of the physical and sensory conditions of their classrooms. Noise emerged as one of the most problematic aspects, with exterior ( = 1.20) and interior noise ( = 1.45) receiving the lowest ratings. A large percentage of teachers (60.7%) reported that their classrooms are located near noisy areas, and more than half (50.8%) indicated difficulty maintaining low noise levels indoors, such as that produced by desks and chairs, student activity, movement, or the use of materials.

Similarly, aspects such as students’ seating choices ( = 1.27), the comfort of school chairs ( = 1.55), adequate aroma ( = 1.38), temperature ( = 1.47), and adequate classroom size ( = 1.59) further point to environmental deficiencies that may affect student engagement, well-being, and inclusive education promotion. In contrast, higher ratings were observed in aspects reflecting teacher agency and support. For instance, 78.6% of respondents reported that school leadership supports teachers’ agency regarding the classroom environment ( = 2.15), and 69% indicated that it allows flexibility in postures or surfaces for learning activities ( = 1.90). Ventilated air ( = 2.12) also received positive evaluations, with most teachers (77.8%) stating they can ensure good air quality through natural ventilation. Additionally, the presence of circulation paths ( = 1.97 for teachers; = 1.90 for students) and personalized classroom elements ( = 1.89) suggests that, despite structural limitations, some environmental and organizational strategies are being implemented to support more inclusive and responsive educational settings.

The low overall satisfaction rating ( = 1.37) was a significant finding, with 53% of teachers and school assistants expressing discontent with the physical classroom conditions, indicating a pressing need for improvements in this dimension. These findings underscore the need for targeted policy measures to address learning environments and classroom conditions, thereby managing inequalities.

4.2. Overall Results of Inclusion for Autistic Primary School Students

Overall, teachers’ perceptions about the inclusion of autistic students were positive, especially regarding staying in the classroom, a sense of belonging, and learning progress. However, levels of well-being and social interactions were lower, suggesting the need to focus on inclusive practices, support social interaction opportunities in the classroom, and promote well-being. Additionally, a slight decrease in perceptions of inclusion was observed as students advanced through grade levels, although there were no statistically significant differences among grades.

The correlation analysis revealed a positive and significant relationship between physical environment conditions (PSCES) and perceptions of inclusion indicators (r = 0.487, p < 0.001), confirming that classroom environmental factors have a significant relationship with the inclusion of autistic students. This finding emphasizes that a sensory-appropriate environment can contribute to improving inclusion; in other words, the inclusion of autistic students depends not only on attitudes and pedagogical and social practices but also on the material and sensory conditions of the educational space.

The hierarchical regression model identified three dimensions of the physical environment as significant predictors of inclusion: sensory conditions; alternative arrangements and spatial organization; and student agency and personalization. These factors collectively explained 31.4% of the variance in teachers’ perceptions of inclusion. This result suggests that classrooms that effectively regulate sensory stimuli (e.g., noise, aromas, visual overload) by creating a sensory-friendly environment, providing adequate spatial organization, and allowing students to participate in and engage with environmental decision-making tend to foster more inclusive experiences for autistic students.

Finally, analyses by inclusion indicators revealed that the sensory environment had a particularly significant influence on permanence in the classroom. At the same time, student agency and personalization of the classroom environment were closely associated with learning progress and a sense of belonging. Conversely, inadequate or uncomfortable furniture negatively affected learning progress and social interaction, highlighting the need to improve physical resources to support inclusive education.

Overall, the results provide robust empirical evidence that the quality of the school’s physical environment constitutes a critical component for developing sustainable and effective inclusive practices for autistic students in primary education.

5. Conclusions

This study aimed to explore, from teachers’ perspectives, the relationship between the physical and sensory characteristics of classrooms and the inclusion of autistic students in primary education. A two-phase design was implemented: The first focused on the development and psychometric validation of the PSCES, and the second examined the relationship between teachers’ perceptions of the physical learning environment and inclusion of autistic students.

The results demonstrate that the PSCES exhibited excellent internal consistency and a robust seven-factor structure, confirming its reliability as a tool for assessing teachers’ perceptions of the physical and sensory conditions of classrooms.

Overall, teachers expressed positive perceptions of autistic students, particularly regarding their permanence in the classroom, sense of belonging, and learning progress. However, perceptions were less favorable concerning their well-being and social interaction, suggesting the need to strengthen inclusive practices that promote peer engagement, emotional support, and active participation in classroom life. A slight decrease in teachers’ perceptions of inclusion of these students was observed as grade levels increased, although these differences were not statistically significant. The scale provides a framework for understanding the physical learning environment as a key element of inclusion.

Consequently, these findings contribute to a deeper understanding of the physical learning environment as a complex, multidimensional construct that directly shapes the educational experiences of both teachers and students. The PSCES, therefore, is not only a valid measurement tool but also a conceptual and practical framework for guiding contextualized transformations in school infrastructure, classroom design, and pedagogical practices. By identifying environmental factors that are related to educational inclusion, the study highlights the classroom as a dynamic and participatory space capable of empowering students, fostering their autonomy, and strengthening agency in the learning community.

From a policy and practice perspective, the PSCES provides empirical evidence to guide educational authorities and school leaders in prioritizing inclusive infrastructure investments and developing evidence-based classroom design policies. It also offers schools a concrete tool for self-assessment, enabling them to critically evaluate how their physical environments support (or hinder) student participation, learning, and well-being. This is particularly relevant in educational systems marked by infrastructural limitations and socioeducational inequalities, such as the Chilean public school system and other Latin American contexts.

Another relevant finding is that from teachers’ perceptions, high levels of agency, participation, ownership of the physical space appropriation, and personalization in classrooms were positive and significant predictors across multiple autism-inclusive indicators: they promoted social interaction, learning, progress, and the perception of being valued and recognized by peers. Meanwhile, sensory conditions were relevant for staying in the classroom, although they were not significant in other outcomes. Inadequate furniture negatively affected social interactions and learning progress (b = −0.75, p = 0.016) in autistic primary students.

Finally, this study presents limitations. The nonprobabilistic sampling method and focus on Chilean education professionals may limit the generalizability of results to other cultural contexts. Moreover, the data reflects only teachers’ perceptions; future studies should incorporate the voices of students, school leaders, and families to capture a more holistic view of inclusion. In this sense, we posit that an adjusted version of the PSCES would need to be designed to capture students’ voices. Although the sample size was sufficient for exploratory factor analysis, additional studies using confirmatory factor analysis are recommended to further validate the instrument’s factorial structure.

Despite these limitations, this research is a significant step forward in building an empirical foundation for understanding how physical and sensory environments influence autism-inclusive education. Future work will continue to explore these dynamics across different educational levels and contexts, contributing to the development of evidence-based tools and school design models that promote equity, participation, and well-being for all students, including autistic students.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.A.D.l.F., C.U., V.L.: methodology, V.A.D.l.F., C.U., V.L., I.M.: Software, V.A.D.l.F., I.M.; validation, V.A.D.l.F., C.U., V.L., I.M.: formal analysis, V.A.D.l.F., C.U., V.L., I.M.: investigation, V.A.D.l.F., C.U., V.L., F.E.-A., I.M.; data curation, V.A.D.l.F.; writing—original draft preparation, V.A.D.l.F., F.E.-A.; writing—review and editing, V.A.D.l.F., F.E.-A.; supervision, V.A.D.l.F., C.U., V.L., I.M.; funding acquisition V.A.D.l.F., C.U., V.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Scholarship for Doctorate National, Agency for Research and Development ANID Chile N° 21221242, Fondecyt Regular National Agency for Research and Development ANID Chile N° 1231674, and Agency for Research and Development ANID Chile: SCIA ANID CIE160009.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the sponsoring university, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso, with code BIOEPUCV-H 802-2024, date of approval 18 July 2024.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset generated and analyzed during the current study is available in the Zenodo repository at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17080643.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the Chilean teachers and education assistants who selflessly supported this research without receiving any financial support or funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study, in data collection, analysis, or interpretation, in writing the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PSCES | Physical and Sensory Classroom Environment Scale |

Appendix A

Table A1.

PSCE conceptual definitions and items.

Table A1.

PSCE conceptual definitions and items.

| Conceptual Definition | Items |

|---|---|

| Infrastructure: The physical space, facilities, and equipment that constitute an educational establishment are designed to ensure optimal conditions of safety, habitability, accessibility, and inclusion (Dirección de Presupuestos, 2021) | Classroom infrastructure: The structural elements and building materials of my classroom are in good condition. Repair and infrastructure maintenance: When there is a malfunction in the classroom, it is possible to contact support staff, and repairs are carried out within a reasonable time frame. |

| Lighting: Lighting conditions necessary for conducting learning activities, including the type of light, its usage, and the adjustability of both natural and artificial light sources (Barrett et al., 2015) | Natural light: My classroom receives adequate natural light. Electric lighting: The electric lighting in the classroom functions properly and supports adequate visibility within the space. |

| Air quality: The level of air pollution, commonly indicated by the ventilation rate and measured through carbon dioxide concentration levels (Barrett et al., 2015) | Ventilated air: The classroom maintains adequate air ventilation (e.g., windows or doors can be opened to allow for air exchange). |

| Noise: Any sound in the school environment that is perceived as disruptive, unpleasant, or inappropriate by students or staff members, potentially interfering with teaching and learning activities (Ministerio del Medio Ambiente, 2011) | External noise: The classroom is located away from noisy areas such as street traffic, playgrounds, fairs, or zones with constant movement within the school. Internal noise: Inside the classroom, noise levels (e.g., voices, chair movement, etc.) are kept low by both students and the teacher. |

| Acoustics: Acoustic qualities of the learning environment that influence the intelligibility of spoken language (Barrett et al., 2015) | Acoustics: The acoustics of my classroom are adequate, allowing all students to hear me without having to raise my voice too much, and the voices do not echo (resonate). |

| Visual information The extent to which the classroom offers appropriate visual diversity, balancing stimulation and clarity to support students’ attention, orientation, and learning (Barrett et al., 2015) | Organized visual stimulation: The classroom provides students with organized visual information (e.g., visuals are concentrated in specific areas, and walls are not excessively decorated or overly colorful). |

| Temperature: Classroom air temperature appropriate for the nature of learning activities and level of physical effort involved, ensuring comfort and concentration (Barrett et al., 2015) | Temperature: The temperature in my classroom is generally comfortable. |

| Aroma: Olfactory sensory stimuli perceived in the classroom | Aroma: The classroom generally maintains a pleasant and neutral smell throughout the school day. |

| Size: Perception of the extent to which students have adequate classroom space to carry out learning activities comfortably (Barrett et al., 2015) | Classroom size: The classroom size is appropriate for the number of students and the pedagogical activities; it does not feel overcrowded or overly full. |

| Movement and Spatial Connection: Spatial connection of learning spaces, possibilities for movement and social interaction, consideringpathways, open space, collaboration. (Barrett et al., 2015) | Movement of teacher: The classroom has clear pathways that allow me to move freely throughout the space and interact with all students. Movement of students: During collaborative or group activities, students are able to move around the classroom to interact and work with their peers. |

| School furniture: Desks and chairs of good quality, appropriate for each age group, that are comfortable and support learning and teaching (Barrett et al., 2015) | Suitable chairs: The students’ chairs and desks are appropriately sized and functional for the educational activities conducted in the classroom. Comfortable chairs: The chairs in my classroom are comfortable for students. Movable and stackable chairs: The students’ chairs and desks can be easily moved and stacked. |

| Spatial organization The spatial arrangement of the classroom, including how the furniture is organized, which can range from a conference format to collaborative or small group settings (Barrett et al., 2015; López et al., 2018) | Furniture reorganization: When necessary, the students’ chairs and desks can be quickly rearranged in under five minutes to create a new layout. Time for reorganization: If necessary, I have sufficient time to rearrange the classroom into different layouts. Organization furniture: My classroom has furniture for organizing or storing students’ belongings and school materials (shelves, lockers, bookcases, or others). Ordered and organized classroom: My classroom remains tidy and organized. Alternative arrangements: Most of the time, I use arrangements other than rows (e.g., group tables, circles, semicircles, horseshoes, etc.). |

| Visibility: The extent to which students can clearly see presentations or audiovisual materials from different areas of the classroom (López et al., 2018) | Visibility in alternative arrangements: When I use arrangements other than ‘rows,’ students can properly see the board or the projection screen. |

| Ownership: The extent to which the distinctive features of the classroom foster students’ sense of belonging and ownership of the space and the degree to which the classroom is individualized for the class as a whole and each student (Barrett et al., 2015) | Personalization: My classroom has been personalized by the students; it includes elements that reflect whose studies there. |

| Agency and Participation: The extent to which students engage and make decisions about their physical learning environment to support their educational experience | Student seating choice: In my class and with the previous organization, students select and decide where they will sit. Seat preferences: I consider students’ preferences and opinions when arranging the seating in my classroom. Comfort Decisions: In my classroom, students can participate in decisions regarding environmental elements that make them feel more comfortable, such as turning off the lights, opening windows, using cushions, moving their desks, etc. |

| Flexibility: The extent to which the physical environment accommodates diverse learning needs, which may vary among students and change over time, supporting both simultaneous and sequential learning scenarios (Barrett et al., 2015) | Managerial support: In my work setting, the managers allow me to make the changes or adjustments that I, as a teacher, find appropriate to promote my students’ learning. Movement possibilities during learning: In my classroom, I always include some pedagogical activity that involves moving, standing, or walking. Postural flexibility: When a student needs it, I allow them to work in different body postures (e.g., sitting on the floor) or in a place other than their desk. |

| Design and aesthetics: How the various elements of the classroom combine to create an environment that is emotionally and visually pleasing, whether coherent and structured or random and chaotic (Barrett et al., 2015; López et al., 2018) | Aesthetic appeal: My classroom is aesthetically appealing; the colors and design of objects and stimuli provided for students are well-balanced. Enjoying the classroom: I like my classroom. |

| Teachers’ Physical well-being and satisfaction with the classroom: Perception of satisfaction with the physical and sensory characteristics of the classroom, including feeling comfortable and well in that space | Physical well-being: I feel physically comfortable and well in this classroom. Overall satisfaction with the classroom: I am satisfied with the physical and sensory conditions of my classroom, as they support learning and enhance the well-being of all my students. |

References

- Ainscow, M. (2025). Reforming education systems for inclusion and equity. Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, C. (2018). Flexible seating: Effects of student seating type choice in the classroom [Master’s thesis, Western Illinois University]. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/docview/2061668236 (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Angulo de la Fuente, V. (2024). Sillas y mesas escolares como agentes de aprendizaje: Reflexiones históricas y actuales. Revista Enfoques Educacionales, 21(1), 256–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashburner, J., Bennett, L., Rodger, S., & Ziviani, J. (2013). Understanding the sensory experiences of young people with autism spectrum disorder: A preliminary investigation. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 60(3), 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baars, S., Schellings, G. L., Krishnamurthy, S., Joore, J. P., den Brok, P. J., & van Wesemael, P. J. (2021). A framework for exploration of relationship between the psychosocial and physical learning environment. Learning Environments Research, 24(1), 43–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baars, S., Schellings, G. L. M., Joore, J. P., & van Wesemael, P. J. V. (2023). Physical learning environments’ supportiveness to innovative pedagogies: Students’ and teachers’ experiences. Learning Environments Research, 26, 617–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baglin, J. (2014). Improving your exploratory factor analysis for ordinal data: A demonstration using FACTOR. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 19(5), 2. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, P., Davies, F., Zhang, Y., & Barrett, L. (2015). The impact of classroom design on pupils’ learning: Results of a holistic, multi-level analysis. Building and Environment, 89, 118–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, P., Treves, A., Shmis, T., Ambasz, D., & Ustinova, M. (2018). The impact of 561 school infrastructure on learning: A synthesis of the evidence. World Bank. Available online: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/853821543501252792 (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Bedard, C., St John, L., Bremer, E., Graham, J. D., & Cairney, J. (2019). A systematic review and meta-analysis on the effects of physically active classrooms on educational and enjoyment outcomes in school-age children. PLoS ONE, 14(6), e0218633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berglund, B., Lindvall, T., & Schwela, D. H. (2002). New WHO guidelines for community noise. Noise & Vibration Worldwide, 31(4), 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bluteau, A., Aubenas, S., & Dufour, F. (2022). Influence of flexible classroom seating on the well-being and mental health of upper elementary school students: A gender analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 821227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, T., & Ainscow, M. (2011). Index for inclusion: Developing learning and participation in schools (3rd ed.). Centre for Studies on Inclusive Education. [Google Scholar]

- Booth, T., & Ainscow, M. (2015). Guía para la educación inclusiva: Desarrollando el aprendizaje y la participación en los centros escolares. FUHEM- OEI. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan, J., & Crosland, K. (2021). Evaluating the use of stability ball chairs for children with ASD in a clinic setting. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 14(3), 1079–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butera, C., Ring, P., Sideris, J., Jayashankar, A., Kilroy, E., Harrison, L., Cermak, S., & Aziz-Zadeh, L. (2020). Impact of sensory processing on school performance outcomes in high-functioning individuals with autism spectrum disorder. Mind, Brain and Education, 14(3), 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byers, T., Mahat, M., Liu, K., Knock, A., & Imms, W. (2018). Systematic review of the effects of learning environments on student learning outcomes. Innovative Learning Environments and Teachers Change. Available online: https://www.iletc.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/TR4_Web.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Cardellino, P., Araneda, C., & Alvarado, R. G. (2017). Classroom environments: An experiential analysis of the pupil-teacher visual interaction in Uruguay. Learning Environments Research, 20, 417–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castilla, N., Llinares, C., Bravo, J. M., & Blanca, V. (2017). Subjective assessment of university classroom environment. Building and Environment, 122, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, V., & Fisher, D. (2003, November, 29). The validation and application of a new learning environment instrument for online learning in higher education. AARE Annual Conference, Fremantle, Australia. Available online: https://www.aare.edu.au/data/publications/2001/cha01098.pdf (accessed on 11 April 2025).

- Danker, J., Strnadová, I., & Cumming, T. M. (2019). “They don’t have a good life if we keep thinking that they’re doing it on purpose!”: Teachers’ perspectives on the well-being of students with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(7), 2923–2934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dargue, N., Adams, D., & Simpson, K. (2022). Can characteristics of the physical environment impact engagement in learning activities in children with autism? A systematic review. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 9, 143–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirección de Presupuestos. (2021). Infraestructura y equipamiento para la Educación Pública del siglo XXI (Versión 4). Ministerio de Educación. Available online: https://www.dipres.gob.cl/597/articles-212578_doc_pdf1.pdf (accessed on 23 May 2025).

- Domínguez, S. (2014). ¿Matrices policóricas/tetracóricas o matrices Pearson? Un estudio metodológico. Revista Argentina de Ciencias del Comportamiento, 6(1), 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echeita, G., & Ainscow, M. (2011). La educación inclusiva como derecho. Marco de referencia y pautas de acción para el desarrollo de una revolución pendiente [Inclusive education as a right. Framework and guidelines for action for the development of a pending revolution.]. Tejuelo, 12(4), 26–46. [Google Scholar]

- Echeita, G., Simón, C., López, M., & Urbina, C. (2013). Educación inclusiva: Sistemas de referencia, coordenadas y vórtices de un proceso dilemático. In M. A. Verdugo, & R. Schalock (Eds.), Discapacidad e inclusión (pp. 329–358). Alianza Editorial. [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa-Andrade, A., Padilla, L., & Carrington, S. J. (2024). Educational spaces: The relation between school infrastructure and learning outcomes. Heliyon, 10, e38361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrando, P. J., Lorenzo-Seva, U., Hernández-Dorado, A., & Muñiz, J. (2022). Decálogo para el análisis factorial de los ítems de un test. Psicothema, 34, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Field, A. (2013). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS Statistics (4th ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, K. (2000). Building better outcomes: The impact of school infrastructure on student outcomes and behaviour. Commonwealth Department of Education, Training and Youth Affairs. [Google Scholar]

- Fitri, A., Dewi, W. N., Hamidy, M. Y., & Saam, Z. (2025). The autistic child friendly school environment model for behavioral development in children with autism. Journal of Education and Health Promotion, 14(1), 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusaro, M., Fanti, V., & Chakrabarti, B. (2023). Greater interpersonal distance in adults with autism. Autism Research, 16(10), 2002–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaines, K. S., & Curry, Z. D. (2011). The inclusive classroom: The effects of color on learning and behavior. Journal of Family and Consumer Sciences Education, 29(1), 46–57. [Google Scholar]

- Gentil-Gutiérrez, A., Cuesta-Gómez, J. L., Rodríguez-Fernández, P., & González-Bernal, J. J. (2021). Implication of the Sensory Environment in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Perspectives from School. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(14), 7670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, D., & Mallery, P. (2003). SPSS for Windows step by step: A simple guide and reference (11.0 update) (4th ed.). Allyn & Bacon. [Google Scholar]

- Ghazali, R., Md Sakip, S. R., Samsuddin, I., & Samra, H. (2021). Determinant factors of sensory in creating autism learning environment. Environment-Behaviour Proceedings Journal, 6(16), 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González de Rivera, T., Fernández-Blázquez, M. L., Simón Rueda, C., & Echeita Sarrionandia, G. (2022). Educación inclusiva en el alumnado con TEA: Una revisión sistemática de la investigación. Siglo Cero, 53(1), 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodall, C. (2018). ‘I felt closed in and like I couldn’t breathe’: A qualitative study exploring the mainstream educational experiences of autistic young people. Autism & Developmental Language Impairments, 3, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodall, C. (2019). ‘There is more flexibility to meet my needs’: Educational experiences of autistic young people in mainstream and alternative education provision. Support for Learning, 34(1), 4–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J., Kang, J., & Ma, H. (2024, August 25–29). Acoustic environment in classrooms for children with autism spectrum disorders: Case studies in China. INTER-NOISE and NOISE-CON Congress. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H., Moon, H., & Lee, H. (2019). The physical classroom environment affects students’ satisfaction: Attitude and quality serve as mediators. Social Behavior and Personality, 47(5), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haug, P. (2019). Inclusion in Norwegian schools: Pupils’ experiences of their learning environment. Education 3–13, 48(3), 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinz, M., Graham, L., & Maulana, R. (2025). Towards more equitable and inclusive learning environments: Forging new connections and research directions. Learning Environments Research, 28, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, F. E., & Stagg, S. D. (2016). How sensory experiences affect adolescents with an autistic spectrum condition within the classroom. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(5), 1656–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JUNAEB. (2019). Informe nacional de monitoreo de la convivencia escolar del año 2018. Available online: https://www.junaeb.cl/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Monitoreo-de-la-Convivencia-Escolar-Programa-Habilidades-Para-la-Vida.pdf (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Kanakri, S. M., Shepley, M., Tassinary, L. G., Varni, J. W., & Fawaz, H. M. (2016). An observational study of classroom acoustical design and repetitive behaviors in children with autism. Environment and Behavior, 49(8), 847–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanakri, S. M., Shepley, M., Varni, J., & Tassinary, L. (2017). Noise and autism spectrum disorder in children: An exploratory survey. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 63, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaundinya, A., & Kaku, S. M. (2025). Sensory responses in autistic individuals—A narrative review. Sensory Neuroscience. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalfa, S., Bruneau, N., Rogé, B., Georgieff, N., Veuillet, E., Adrien, J. L., Barthélémy, C., & Collet, L. (2004). Increased perception of loudness in autism. Hearing Research, 198(1–2), 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krombach, T., & Miltenberger, R. (2020). The effects of stability ball seating on the behavior of children with autism during instructional activities. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(2), 551–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]