Abstract

This study explores how integrating simulations into lessons on electrical conductivity in aqueous solutions and electrolysis affects eighth-grade students’ academic achievement, motivation, and their perception of classroom climate. The study included 130 students (64 males, 66 females) from six classes in two Israeli middle schools, divided into an experimental group (68 students, simulation-integrated instruction) and a control group (62 students, traditional instruction). Participants completed pre- and post-achievement tests as well as motivation and classroom climate questionnaires. The results revealed significant improvements in achievement, especially for students with a lower initial performance. Additionally, when simulations were utilized, there was enhanced motivation to study chemistry. Simulations also improved students’ perception of classroom climate across all dimensions, with no significant gender differences observed. A strong positive correlation was found between achievements and motivation, as well as between classroom climate and motivation. The findings underscore the value of simulations and digital tools in education, emphasizing their role in creating more engaging learning experiences. These results also highlight the need for decision-makers to integrate such tools into science education to foster better outcomes in student learning experience.

1. Introduction

Students often struggle to grasp complex and abstract scientific concepts in chemistry, particularly in areas such as electrical conductivity in aqueous solutions and electrolysis (Beal et al., 2017; Calleja et al., 2020). These challenges can negatively impact their attitudes toward the subject, reduce motivation, and deter interest in scientific careers. To address these issues, enhance accessibility of complex content, and support students in developing strategies to overcome learning obstacles, digital tools could be incorporated into instruction (Avidov-Ungar & Iluz, 2015; Ekmekci & Gulacar, 2015; Vlachopoulos & Makri, 2017).

Simulations offer a safe and efficient approach for teaching complex scientific topics, especially in electrical and electrolytic systems. Interactive platforms allow students to explore intricate processes, visualize cause-and-effect relationships, and develop scientific reasoning and problem-solving skills (Beal et al., 2017). These dynamic learning experiences enhance student understanding and performance in topics related to electrical conductivity, while also fostering collaboration, teamwork, and peer discussion (Aires et al., 2024; Beal et al., 2017). Singh-Pillay (2024) stresses that simulations improve conceptual understanding and spatial visualization, enabling students to actively engage with scientific material beyond the limitations of traditional lab environments. Furthermore, digital tools support diverse learning styles, thus increasing motivation and engagement with the material (Waleed, 2009). When integrated effectively, they not only promote meaningful learning but also provide innovative strategies for educators to address content as well as pedagogical and organizational challenges. Technology enhances information access and interactivity, enabling the design of high-level, team-based learning tasks that cultivate an inclusive and participatory classroom environment (Inbal-Shamir & Kali, 2007). However, despite their benefits, there is a need for improved resources and professional development to support the effective integration of simulations in science education (Stinken-Rösner, 2020).

This study examines the impact of integrating simulations into instruction on student achievement, classroom climate, and motivation in the context of teaching electrical conductivity in aqueous solutions and electrolysis. The findings have broader implications for inclusive education and technology-enhanced learning environments. In contrast to earlier studies where simulations were often used as supplementary tools, this research integrates both digital simulations and physical models as central components of instruction. By embedding these tools directly into the teaching sequence, the study explores their combined effect on both cognitive gains and emotional engagement. This approach is particularly relevant in middle school science education, where students often struggle with abstract concepts and benefit from interactive, multimodal learning experiences. By investigating the dual role of simulations in enhancing academic performance and fostering a supportive classroom environment, this study contributes valuable insights for developing effective, inclusive teaching strategies that address the evolving needs of today’s learners.

2. Literature Review

Electrolysis and electrical conduction are core topics in both chemistry and physics, offering insight into the behavior of electricity in materials and biological systems. These subjects are typically taught through a combination of theoretical and practical instruction, emphasizing foundational principles, terminology, laws, and relevant chemical and physical processes (Stankiewicz & Nigar, 2020). Practical laboratory work, such as using electrolytic cells and analyzing electrolytic reactions, provides firsthand experience that reinforces theoretical understanding (Calleja et al., 2020). Increasingly, instructors supplement these experiences with interactive simulations such as PhET’s “Circuit Construction Kit” and electrolysis modules, which allow students to visualize electron flow, ion migration, and circuit behavior at both macroscopic and particulate levels (Moore et al., 2014; Perkins et al., 2006). This blended approach strengthens conceptual understanding by linking theory, hands-on practice, and dynamic representations of invisible processes.

In Israel, instruction progresses sequentially. Students first encounter simple metallic circuits in the fourth grade, advance to electrolytic conduction by eighth grade, and study the topics in greater depth by eleventh grade (Ministry of Education, 2022). Learning these topics pose challenges due to their abstract nature, requiring students to understand submicroscopic interactions, multiple variables, and complex systems (Johnstone, 1991; Gilbert & Treagust, 2009). Students often lack sufficient foundational knowledge in chemistry and physics, and the invisibility of these processes necessitates abstract reasoning, which can hinder comprehension (Taber, 2002). Studies of PhET simulations show that their intuitive drag-and-drop interfaces and visual cues can help students bridge the gap between macroscopic observations and submicroscopic interpretations, addressing the representational challenges identified by Johnstone (Johnstone, 1991; Podolefsky et al., 2010). The absence of engaging, tangible experiences in the classroom further limits students’ grasp of the concepts (Harrison & Treagust, 2000). To address these challenges and contextualize learning, educators can employ diverse strategies, such as tangible analogies, hands-on experiments, and digital simulations (Burke et al., 2020). For instance, electrolysis, where an electric current drives a chemical reaction to separate ions and electrons, is essential in industrial applications (Stankiewicz & Nigar, 2020). Providing experiential learning opportunities enables students to relate such abstract processes to real-world contexts (Calleja et al., 2020; Stankiewicz & Nigar, 2020). Simulation environments that animate ion movement, electrode behavior, and charge interactions provide middle-school learners with meaningful entry points into otherwise abstract chemical processes (Moore et al., 2014).

Technology expands instructional possibilities by creating interactive, collaborative learning environments that enhance creativity, critical thinking, and retention (Avidov-Ungar & Iluz, 2015; Ghavifekr et al., 2016). Tools such as computers, tablets, and online platforms support active learning, personalized instruction, and enriched teacher-student interactions (Calleja et al., 2020). Simulations, in particular, replicate real-world processes in virtual environments, allowing students to conduct experiments, test hypotheses, and analyze results safely and dynamically (Cant & Cooper, 2017; Ross et al., 2020). Inquiry-based simulation tools such as PhET encourage iterative model exploration, enabling students to manipulate variables like voltage and ion concentrations while observing immediate visual feedback (Keller et al., 2021). These tools help visualize complex concepts, such as electron flow in conductive materials and solutions, and allow students to manipulate variables such as voltage, current, and time (Beal et al., 2017; Calleja et al., 2020).

Simulations also enable educators to assess student understanding by tracking decision-making processes and execution times, while also offering students targeted feedback for improvement (Hong et al., 2018; Roberts & Greene, 2011). This makes simulations especially useful for preparing students for real-world scientific tasks in a risk-free setting. They help bridge the gap between theory and practice, promoting conceptual understanding while addressing common misconceptions (Beal et al., 2017; Calleja et al., 2020). Beyond content mastery, simulations promote active learning, critical thinking, and problem-solving by enabling students to replicate experiments, interpret results, and reflect on their understanding (Papadakis et al., 2023). They foster engagement through interactive experiences that link abstract ideas with practical applications.

Simulation-based learning (SBL) also supports collaboration and skill development, encouraging students to predict outcomes, formulate questions, and refine understanding through reflection. In professional education, such as nursing, simulations help learners build competence and confidence before engaging in real-life scenarios (Roberts & Greene, 2011; Ross et al., 2020). Moreover, simulations enhance emotional and cognitive engagement, leading to deeper learning and improved academic outcomes (Immordino-Yang, 2011; Lonka & Ketonen, 2012). This is particularly important for students with learning difficulties, who often experience comprehension-related cognitive and linguistic barriers related to working memory, information processing, and processing speed (Asadi, 2020; Goff et al., 2005; Johnston & Kirby, 2006). Evidence from PhET implementation research shows that these simulations reduce extraneous cognitive load by relying on visual metaphors rather than symbolic formalism, making them particularly effective for learners who struggle with text-heavy explanations (Perkins et al., 2006). In addition, because PhET simulations incorporate color-coding, motion, and manipulable objects, they offer multiple entry points that support diverse learners and can reduce cognitive barriers associated with purely verbal or numerical instruction (Keller et al., 2021). These features collectively create learning environments, allowing SBL to meet students’ needs and foster imaginative, inclusive instruction.

Singh-Pillay (2024) further points out that simulations improve spatial visualization and conceptual understanding, especially in scientific domains where abstract reasoning is critical. Immersive and interactive digital environments enhance student engagement and learning outcomes but require thoughtful integration to overcome implementation challenges (Aires et al., 2024). Stinken-Rösner (2020) reports that 61% of surveyed German science teachers use digital simulations in their instruction. Their selection is primarily influenced by scientific accuracy, availability, and clarity of design, while considerations for student diversity are often overlooked. These findings emphasize the need for improved simulation resources and targeted professional development to support inclusive and effective science instruction.

Beyond cognitive outcomes, several studies emphasize that simulation-based learning also fosters emotional engagement, which is an essential component of meaningful learning in science education. Emotional aspects such as enjoyment, interest, curiosity, and a sense of belonging in the classroom have been found to mediate the relationship between motivation and academic performance (Immordino-Yang, 2011; Lonka & Ketonen, 2012). A positive classroom climate supports these emotions by creating a safe environment where students feel comfortable to explore, question, and collaborate. In this study, motivation and classroom climate are therefore conceptualized not merely as contextual variables but as key emotional dimensions that interact with cognitive outcomes. This framework provides a theoretical rationale for including emotional components alongside achievement when examining the effects of simulations on students’ learning experiences.

Building on these findings, it is important to recognize that while the benefits of simulations in science education are well-documented, many studies have treated cognitive and emotional domains separately. For example, Beal et al. (2017) and Calleja et al. (2020) highlighted improvements in students’ conceptual understanding and engagement, whereas Papadakis et al. (2023) and Roberts and Greene (2011) focused more on how simulations influence motivation and classroom atmosphere. However, relatively few studies have examined how fully integrated simulations—combining both virtual and physical tools—can simultaneously support achievement, motivation, and perceptions of the classroom climate. This gap is particularly relevant in middle school education, where students are transitioning from concrete to abstract thinking and may become disengaged if content feels disconnected from their experiences or overly complex (Eccles & Roeser, 2011).

This study responds to that gap by implementing a dual-mode simulation model that includes both digital platforms (e.g., PhET simulations) and hands-on manipulatives (e.g., electrical models and pulleys), embedding them centrally in the instructional sequence on electrical conductivity and electrolysis. Unlike prior research in which simulations were used peripherally or as supplemental activities, this study positions them as integral to the learning process and aligned with curriculum objectives. In doing so, it aims to demonstrate how integrated simulations can effectively enhance both the cognitive and emotional dimensions of science learning. This dual emphasis is particularly valuable for supporting students who struggle with abstract scientific content and for designing more inclusive, engaging, and supportive learning environments (Singh-Pillay, 2024; Stinken-Rösner, 2020).

In summary, integrating simulations into the teaching of electrolysis and electrical conduction has great potential to enrich student engagement, comprehension, and scientific skills. By merging theory with interactive practice, educators can create dynamic learning environments that empower students to explore complex scientific processes safely and meaningfully, preparing them for future academic and professional challenges.

Research Questions

- To what extent does the integration of simulations in teaching electrical conduction in aqueous solutions and electrolysis affect the academic performance of 8th-grade students compared to traditional instructional methods?

- How does the use of simulations influence the learning motivation of 8th-grade students, and how does it compare to the motivation levels of students taught without simulations?

- In what ways does simulation-based instruction shape the classroom climate for 8th-grade students learning about electrical conduction in aqueous solutions and electrolysis?

- Is there a correlation between academic performance, learning motivation, and classroom climate among students taught using simulation-based methods?

3. Methods

This study employed a quasi-experimental, quantitative research design to assess the impact of simulation-based instruction. Numerical data were collected and analyzed before and after the intervention using statistical methods to ensure objective and systematic evaluation. A pretest–posttest design was implemented, comparing outcomes between an experimental group that received the intervention, and a control group taught via traditional methods. This comparative structure allowed for the measurement of changes over time and the isolation of effects attributable specifically to the simulation-based teaching.

3.1. Participants

The study involved 130 eighth-grade students from a middle school in northern Israel, comprising 64 male (49%) and 66 female (51%) students. Participants were divided into two groups: an experimental group (N = 68) received instruction on electrical conduction in aqueous solutions and electrolysis using simulation-integrated methods, while the control group (N = 62) was taught using traditional approaches without simulations. Students were drawn from six eighth-grade classes across three schools, selected via convenience sampling. Each school contributed one class to the experimental group and one to the control group, ensuring balanced representation.

To reduce teacher-related variability, the same teacher instructed both the experimental and control classes within each school. The study focused on high-achieving classes with similar socioeconomic backgrounds to enhance comparability between groups. While classroom achievement levels remained heterogeneous, overall academic performance between the groups was balanced, providing a fair basis for comparison.

The research followed strict ethical guidelines. School administrators were informed of the study’s goals and procedures; parents were notified and provided prior written consent. Students were assured that participation was voluntary, confidential, and would not influence their academic standing or grades. The institutional ethics committee approved the research protocol. One ethical consideration involved the differential learning experiences of the two groups, as only the experimental group received simulation-based instruction. Table 1 provides a detailed demographic breakdown of the study participants.

Table 1.

Distribution of study participants by group and gender (N = 65).

3.2. Instruments

This study employed a range of instruments to assess the impact of simulation-based learning on student achievement, motivation, and perceptions of classroom climate.

Pre- and Post-Achievement Tests: The pre-test assessed students’ prior knowledge of electrical conductivity, focusing on basic circuits with metallic conductors and the properties of metals and solutions. The post-test evaluated their understanding of electrical conductivity in aqueous solutions and electrolysis. Both assessments included 10 single-choice questions with four options, only one of which was correct. Students were allotted 45 min to complete each test. Items were adapted from materials developed by the school’s science teaching staff to ensure alignment with the eighth-grade science curriculum (Ministry of Education, 2022). Content validity was established through review by two science education experts. These assessments provided a quantitative measure of learning changes resulting from the intervention. Two sample questions—one from the pre-test and one from the post-test—are provided below for illustration.

- (Pre-test) Which of the following materials conducts electric current?

- Piece of wood.

- Copper wire (The correct answer)

- Sulfur

- Distilled water.

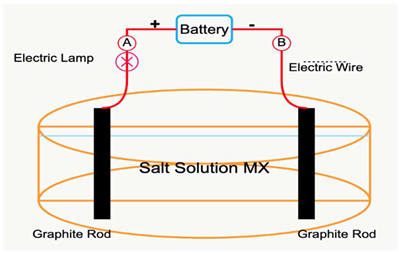

- (Post-test) Maryam immersed two graphite rods in a cup containing a salt solution and connected them with metal wires and a battery as shown in the diagram below.

Suppose two Smurfs, both skilled at counting electrons, are sitting on the electrical wire at points A and B (refer to the diagram). What would be the correct interpretation of their observations?

Suppose two Smurfs, both skilled at counting electrons, are sitting on the electrical wire at points A and B (refer to the diagram). What would be the correct interpretation of their observations?- The number of electrons that passed and were counted at point A is greater than their number at point B.

- The number of electrons that passed and were counted at point A is less than their number at point B.

- The number of electrons that passed and were counted at point A is equal to their number at point B. (The correct answer)

- The number of electrons at each point cannot be determined.

The internal consistency of the achievement pre- and post-test was examined using Cronbach’s alpha, which indicated satisfactory reliability (αpre = 0.79, αpost = 0.87) for the ten-items in each test. This suggests that the items adequately measure a coherent construct representing students’ understanding of electrical conductivity and electrolysis. The reliability analysis further supports the validity of the test for assessing students’ achievement in the context of simulation-based instruction.

Motivation Questionnaire: Student motivation toward science was assessed using a 30-item Likert-type questionnaire developed by Glynn et al. (2009). The instrument comprises six motivation dimensions (Table 2). Sample items include: “Getting a good grade in chemistry is very important to me.” Responses were scored on a 5-point scale: 1 = “Never,” 2 = “Rarely,” 3 = “Sometimes,” 4 = “Often,” and 5 = “Always.” Mean scores were calculated for each category. The instrument demonstrated strong internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.88 and a value of 0.93 for the original research (Glynn et al., 2009).

Table 2.

Items for each category, mean and standard deviation, and Cronbach’s Alpha value for the Motivation Questionnaire.

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics (means and standard deviations) of the instruments used in this study, based on the current research sample. The values reflect students’ responses in the pre-intervention stage and were used to verify the normality and internal consistency of the measures.

Classroom Climate Questionnaire: A modified version of the “What Is Happening In this Class?” (WIHIC) questionnaire developed by Afari et al. (2013) was used to assess students’ perceptions of classroom climate. The original WIHIC measures six dimensions: teacher support, student cohesiveness, involvement, cooperation, equity, and relevance. This study added a seventh category, physical environment, adapted from the Learning Environment Inventory (LEI) by Fraser and Walberg (1982) Each category contained five items, totaling 35 items. All categories with the item numbers were shown in Table 3. Students responded on a 5-point scale: 1 = “Almost never,” 2 = “Rarely,” 3 = “Sometimes,” 4 = “Usually,” 5 = “Almost always.” The overall instrument demonstrated high reliability, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.85. The reliability of the original questionnaire was checked using an internal traceability reliability check by Krubbach’s alpha coefficient, and it was found that the alpha value for the dimensions ranged from 0.81 to 0.92, with the alpha value for the entire questionnaire being 0.89.

Table 3.

The items in each category and the mean and standard deviation of it and the value of Cronbach’s alpha for the classroom climate questionnaire.

By combining these instruments, the study captured comprehensive quantitative data on student learning outcomes, motivation, and perceptions of the classroom environment.

3.3. Design and Data Collection

To evaluate the impact of simulation-based teaching, a quasi-experimental pretest–posttest design was employed. Both the experimental and control groups completed the same set of instruments: an achievement test, a motivation questionnaire, and a classroom climate questionnaire. These were administered at two points—prior to and following the instructional intervention.

Participants were drawn from six eighth-grade classes across three middle schools in northern Israel. Each teacher taught both an experimental and a control class to minimize teacher-related variability. The two-month intervention consisted of eight instructional sessions aligned with the national science curriculum on electrical conductivity and electrolysis.

The experimental group participated in lessons integrating virtual simulations (e.g., PhET) with physical models (e.g., electrical circuit kits), while the control group received traditional instruction emphasizing frontal teaching, textbook exercises, and demonstrations. Each simulation session lasted approximately 45–50 min and was conducted once per week (for eight weeks). The selected PhET simulations were adapted to address topics such as electrical conductivity in aqueous solutions and electrolysis, allowing students to explore ionic movement, electrode reactions, and the relationship between voltage, current, and solution concentration. In several sessions, simulations were complemented by simple physical models (e.g., circuit boards, electrodes, and beakers) to connect virtual and real-world contexts. The intervention followed an inquiry-based learning approach in which students predicted outcomes, ran simulations, recorded observations, and discussed results collaboratively. Teachers facilitated guided discussions focused on conceptual understanding and correcting common misconceptions (e.g., distinguishing between electron and ion movement).

The experimental group received seven lessons (each lesson 45 min) over seven weeks that incorporated simulation-based learning. Each lesson included a simulation with an emphasis on conceptualizing a specific topic in electrical conduction.

- Lesson one, a simulation on the topic of conduction in a simple electrical circuit and a demonstration of a closed simple electrical circuit.

- Lesson two, structure of ionic compounds and molecular compounds in condensed phases including solid state, liquid state and in solutions in context of conductivity.

- Lesson three, dissolving electrolytes in water and dissociating them into ions and comparing them to dissolving non-electrolytes.

- Lesson four, a simulation to demonstrate conduction in an electrical circuit containing an electrolyte solution and a solution containing a non-electrolyte.

- Lesson five, a simulation of the electrolysis of the ionic compound “copper chloride”.

- Lesson six, a simulation of the electrolysis of water.

- Lesson seven, a simulation demonstrates measuring the voltage of an electrochemical cell.

- Lesson eight, a simulation that demonstrates how batteries work.

3.4. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS software version 28.0.1.0(142). Descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations, and frequencies) were used to summarize participants’ responses, while inferential tests were conducted to evaluate the effects of the intervention.

- To address Research Question 1 (achievement), independent-sample t-tests compared post-test results between the experimental and control groups, while paired-sample t-tests assessed within-group changes from pre- to post-test. Prior to conducting the t-tests, the data were examined for normality to ensure that the assumptions of parametric analysis were met. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk tests indicated that all variables were normally distributed (p > 0.05). In addition, skewness and kurtosis values were within the acceptable range of ±1, supporting the suitability of the data for parametric testing.

- For Research Question 2 and 3 (motivation and classroom climate), similar t-test procedures were used to examine differences within and between groups over time.

- Research Question 4 (correlations) was addressed using Pearson’s correlation, revealing relationships among student achievement, motivation, and classroom climate. Additionally, independent-sample t-test was conducted to analyze links between gender and changes in motivation.

This analytical framework enabled a multidimensional evaluation of the intervention’s impact, revealing not only group differences but also interrelationships among cognitive and affective learning outcomes.

4. Results and Discussions

The results presented in this section provide a comprehensive evaluation of the impact of integrating simulations into instruction on three key variables: students’ academic achievement, motivation to learn science, and perceptions of classroom climate. Comparisons were made both within and between the experimental and control groups to determine the effectiveness of simulation-based learning. In addition, the analyses explored whether the intervention affected students differently based on gender and initial achievement level, offering a nuanced understanding of its impact across diverse learner profiles. Findings are organized according to the four research questions, highlighting statistically significant patterns and their educational implications.

4.1. The Effect of Integrating Simulations on 8th-Grade Students Achievements on This Topic

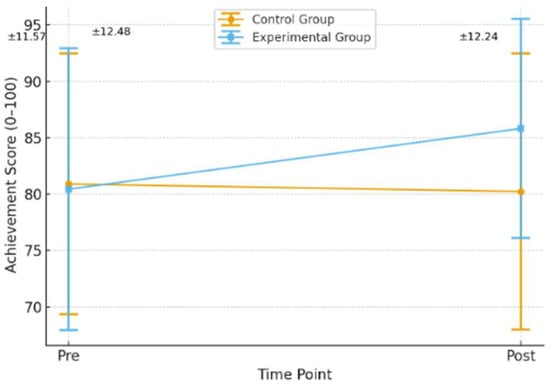

The first question focused on the impact of simulations on the students’ achievements with respect to their understanding of electrical conductivity in solutions. Figure 1 illustrates the achievements of students in both the experimental and control groups at two time points: before (pre-test) and after (post-test) the intervention. Initially, the two groups demonstrated similar achievement levels, with the experimental group scoring 80.44 and the control group scoring 80.90 on the pre-test. However, significant differences emerged in the post-test results.

Figure 1.

Students’ Pre- and Post-Achievement Scores in both Control and Experimental Groups.

The experimental group, which experienced simulation-integrated learning, showed a notable increase in achievement, with their average score rising to 85.82. In contrast, the control group, which followed traditional teaching methods, exhibited a slight decline, with their average score dropping to 80.23.

This comparison highlights the positive impact of simulation-based teaching on students’ academic performance. The substantial improvement in the experimental group underlines the effectiveness of simulations in enhancing students’ understanding of complex scientific concepts like electrical conductivity in aqueous solutions. Conversely, the slight decline in the control group may suggest that traditional methods may not be as effective in fostering deeper comprehension of the material seen as a key in the retention of knowledge.

To determine if the observed differences were statistically significant, independent samples t-tests were conducted. Table 4 presents the means and standard deviations for student achievements in the experimental and control groups at both the pre- and post-test stages. Preliminary analyses confirmed that the data met the assumptions for t-testing, including normal distribution and homogeneity of variance.

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics of student achievement in the two experimental groups at two time points (Pre and Post) and the differences between them.

The results in Table 4 reveal no statistically significant difference between the two groups in the pre-intervention phase, indicating that the experimental and control groups were comparable in their initial achievement levels (t(128) = −0.15, n.s.). However, after the intervention, the experimental group showed significantly higher average achievements compared to the control group (t(128) = 2.05, p < 0.05). Cohen’s d = 0.45, indicating a medium effect size. A paired-samples t-test for the experimental group demonstrated that their post-test scores were significantly higher than their pre-test scores (t(67) = 6.48, p < 0.001).

It is important to note that both groups demonstrated relatively high pre-test scores (M ≈ 80), which may indicate a partial ceiling effect. This means that students—particularly those already performing well—had limited room for further improvement, potentially constraining the magnitude of gains observable in the control group. Despite this, the experimental group still showed significant progress, suggesting that simulation-based learning was effective even under conditions where initial performance levels were already high. Notably, low-achieving students exhibited the largest gains, further supporting the robustness of the intervention.

These results reinforce the effectiveness of integrating simulations into the teaching of electrical conductivity in aqueous solutions and electrolysis. Students in the experimental group not only outperformed their peers in the control group but also exhibited significant improvement within their group over time. These findings underline simulations as an effective tool to enhance teaching and enrich learning, aligning with prior research emphasizing the benefits of active and practical learning methods (Roberts & Greene, 2011). Simulation-based learning also allowed students to actively engage with abstract scientific concepts by visualizing and applying them in practical, interactive scenarios. In the case of electrical conductivity in solutions, students observed key processes, such as the transfer of electrons between electrodes and ions in a solution. For example, they were able to see how electrons move from the electrode to ions in solution and vice versa, gaining a better understanding of the fundamental role of ion migration in conductivity.

These findings are consistent with the findings from the study of Singh-Pillay (2024), which showed that SBL enhances conceptual understanding and spatial visualization skills. They also align with the views of Aires et al. (2024) and his colleagues and clearly demonstrate the importance of integrating these technologies effectively into the curriculum to foster critical thinking and practical skills, while also addressing the challenges and considerations necessary for successful implementation.

A common misconception among students is that electrolytes “swim” freely between electrodes, rather than recognizing the structured movement of charged particles driven by electric fields. Simulations reveal these microscopic interactions in a clear and dynamic way, reinforcing accurate conceptual understanding and helping to correct alternative conceptions on the subject. Through interactive exploration, students gain a deeper and more intuitive understanding of how metallic electrodes facilitate electron transfer and how ions contribute to electrical conductivity in aqueous solutions. This hands-on engagement not only strengthens conceptual understanding but also boosts students’ confidence and problem-solving skills, particularly in challenging topics such as electrical conduction and electrolysis (Hong et al., 2018; Roberts & Greene, 2011). By bridging the gap between abstract theory and real-world application, simulation-based learning provides an effective and inclusive approach to mastering complex scientific phenomena.

To explore potential gender differences, a t-test was conducted to examine the impact of the intervention on male and female students. Table 5 reveals no statistically significant gender differences in achievements (t(128) = 1.174, p < 0.05). This lack of difference suggests that the intervention was equally effective for both males and females.

Table 5.

Mean and standard deviation of student achievements among males and females and the t difference between them.

According to Hong et al. (2018), this may be attributed to a balanced learning environment where all students had equal access to the concepts and simulation-based experiences. Additionally, the study size may not have been large enough to detect subtle differences between genders. These results may also be interpreted as supporting the integration of simulations as an inclusive instructional tool that benefits students regardless of gender, thereby advancing equity in science education.

4.2. The Effect of Integration of Simulation on the Eighth-Grade Students’ Motivation

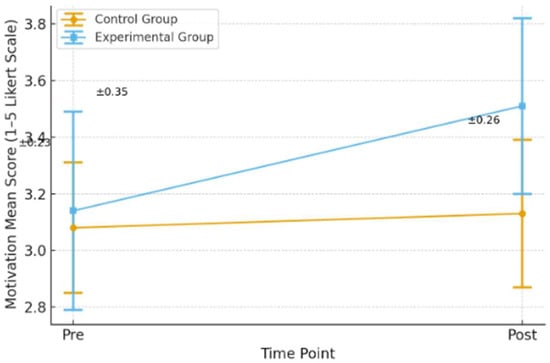

In addition to examining the effects of simulations on students’ achievements, the study also sought to investigate the impact of simulations on students’ motivation. By integrating simulation-based learning into the curriculum, we aimed to determine whether this teaching approach could enhance students’ enthusiasm and drive to engage with complex scientific concepts like electrical conductivity in aqueous solutions and electrolysis. Motivation, a critical component of the learning process, was analyzed alongside achievement to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the intervention’s impact. Figure 2 illustrates the changes in general motivation before and after the intervention for both the experimental and control groups.

Figure 2.

Students’ Pre- and Post-general motivation scores in both control and experimental groups.

Both groups started with comparable levels of general motivation, with the experimental group scoring 3.14 and the control group slightly lower at 3.08. Following the intervention, the experimental group, which engaged in simulation-integrated learning, displayed a significant increase in motivation, rising to 3.51. In contrast, the control group, which was taught using traditional methods, experienced only marginal improvement, moving from 3.08 to 3.13. Overall, the experimental group demonstrated a markedly greater enhancement in motivation compared to the control group, emphasizing the positive impact of incorporating simulations into the teaching process.

Statistical tests were then employed to ensure that the observed differences in motivation were meaningful and generalizable to a larger population. Table 6 presents the means and standard deviations of general motivation, for both the experimental and control groups at two time points (pre- and post-intervention).

Table 6.

Descriptive statistics of motivation in general and across different categories for both experimental groups at two time points (Pre and Post) and the differences between them.

An independent samples t-test revealed no statistically significant difference in general motivation between the experimental and control groups at the pre-intervention stage (t(128) = 0.79, n.s.), indicating that the two groups were comparable in their motivation to study science prior to the intervention (See Table 6 and Figure 2). Similarly, no significant differences were found across specific motivation categories (Table 6).

However, post-intervention findings showed a significant increase in general motivation for the experimental group compared to the control group (t(128) = 5.24, p < 0.001). This increase was reflected in most motivation categories, including intrinsic motivation, personal importance, and self-efficacy. Additionally, the experimental group demonstrated significantly lower levels of evaluation anxiety after the integration of simulations compared to the control group (Table 6). A paired samples t-test for the experimental group further supported these findings, revealing a significant improvement in general motivation after the integration of simulations compared to before, (t(67) = 5.29, p < 0.001). Improvements were observed in intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation, and self-efficacy, with anxiety about evaluation also decreasing significantly.

The results clearly indicate the significant positive impact of integrating simulations into teaching electrical conductivity in aqueous solutions. While no initial differences were observed between the control and experimental group, the post-intervention stage showed notable improvements in motivation among students in the experimental group, both in general motivation and across various subcategories. These findings suggest that simulations enhance student engagement and foster a more profound and enjoyable learning experience. The interactive and participatory nature of simulations allows students to immerse themselves in complex learning processes, experience scientific challenges, and develop confidence and enthusiasm for the subject matter.

Simulation-based learning transforms abstract concepts into active practice, enabling students to experiment, manipulate variables, and observe outcomes in a safe, user-friendly environment. For example, simulations allow students to examine the effects of parameters such as voltage, current, and chemical composition on scientific processes as well as electrons transfer between electrodes and ions, helping them connect theoretical knowledge with practical applications (Papadakis et al., 2023). This approach provides opportunities for students to replicate laboratory experiments, analyze results, design new experiments, and test various effects, significantly enhancing their understanding (Beal et al., 2017).

To explore whether the impact of simulations on motivation differed between male and female students, an independent samples t-test was conducted. The results, presented in Table 7, showed no statistically significant difference in general motivation between males and females (t(128) = 0.12, p > 0.05). Similarly, no significant differences were observed across individual motivation categories. These findings suggest that simulations were equally effective in enhancing motivation for both male and female students.

Table 7.

Mean and standard deviation of motivation among males and females, and the t-test difference between them.

Gender differences were examined using independent samples t-tests based on the post-test scores, as the post-test reflected students’ final level of achievement after the intervention. Pre-test differences between male and female students were also examined to confirm that both groups started at a comparable baseline. No significant differences were found in the pre-test scores (p > 0.05), indicating that the two groups were comparable before the intervention (Table 7).

The lack of gender differences in motivation aligns with prior research suggesting that external factors, such as family support systems, peer influence, and school learning culture, may play a larger role in shaping motivation than gender alone (Dorfberger & Carmi, 2017; Fraser & Walberg, 1982). Additionally, cultural perceptions or social expectations may influence students’ responses and their reported levels of motivation. The gender-neutral impact of simulations emphasizes their value as an inclusive teaching tool that benefits diverse student populations.

The study documents the benefits of integrating simulations into teaching to enhance students’ motivation. The experimental group exhibited substantial increases in motivation compared to the control group, demonstrating the effectiveness of interactive and engaging instructional methods. Simulations provide students with opportunities to actively engage in scientific processes, tackle challenges, and gain a deeper understanding of the material. This innovative approach connects theoretical content to practical applications, fostering confidence and enthusiasm among students. Moreover, the absence of gender differences in motivation emphasizes the inclusivity of simulation-based learning, making it a valuable tool for diverse educational contexts. By providing an immersive, participatory learning environment, simulations have proven to be a powerful method for amplifying student motivation and fostering a positive attitude toward science education.

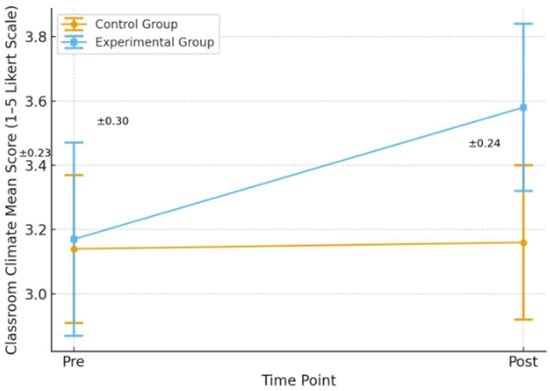

4.3. The Effect of Inclusion of Simulation on the Classroom Climate

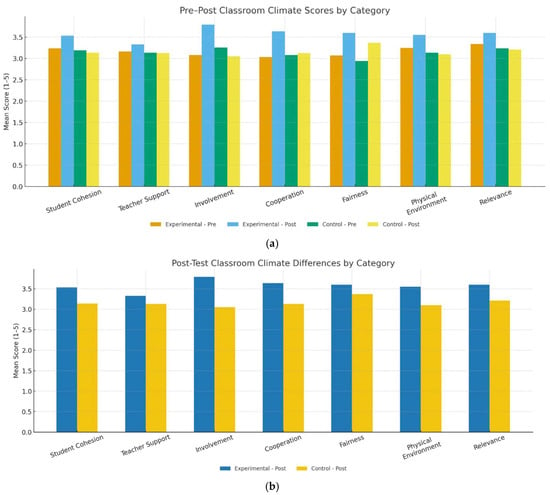

The third research question explored the changes in classroom climate when simulations were integrated into the teaching of electrical conductivity in chemical solutions. As depicted in Figure 3 and documented in Table 8, the experimental group, which used simulations as part of the instructional approach, exhibited positive changes in classroom climate. Initially, the classroom climate in both groups was relatively similar, with the experimental group scoring 3.17 and the control group scoring 3.14 on the pre-test. Following the intervention, the experimental group’s classroom climate improved markedly to 3.58, while the control group saw only a modest increase to 3.16. This difference makes the positive effect of simulations clear in fostering a more engaging and collaborative classroom environment.

Figure 3.

Students’ Pre- and Post-Perception of Classroom Climate Scores for both Control and Experimental Groups.

Table 8.

Descriptive statistics of classroom climate in general aspect for both experimental groups at two time points (Pre and Post) and the differences between them.

The interactive nature of simulation-based learning likely contributed to this outcome. Simulations provide students with hands-on experiences, enabling them to experiment, solve problems collaboratively, and engage in meaningful discussions. These activities not only enhance their understanding of the subject matter but also encourage active participation and teamwork, creating a more inclusive and dynamic classroom atmosphere. In contrast, the modest improvement in the control group suggests that traditional methods may not be as effective in transforming the classroom environment. While the traditional methods can still foster some positive interactions, they lack the engaging and participatory elements that simulations bring to the learning experience.

These findings align with prior research, such that of Roberts and Greene (2011), which emphasizes the importance of interactive and experiential learning environments in enhancing classroom dynamics. By integrating simulations into teaching, educators can create a more vibrant and supportive atmosphere that fosters student engagement, collaboration, and a deeper sense of connection to the learning process. This improvement in classroom climate further underscores the value of simulations as a teaching tool that benefits not only individual achievement but also the collective learning experience. Moreover, Singh-Pillay (2024) found that virtual worlds and simulations in science education have great potential to create immersive and interactive learning environments that enhance student engagement and understanding of scientific concepts.

To assess the statistical significance of differences in classroom climate, a series of tests were conducted. Table 8 presents the means and standard deviations for the overall classroom climate and its various categories for both the experimental and control groups at two time points (Pre and Post). An independent samples t-test revealed that, during the pre-test phase (Pre), there were no statistically significant differences between the experimental and control groups regarding classroom climate in science lessons (t(128) = 0.39; n.s.). This indicates that both groups started with similar classroom climates across all measured categories (Figure 4). Figure 4a displays the pre–post development for each group, while Figure 4b highlights the post-intervention differences.

Figure 4.

(a): “Pre–post classroom climate comparison (all dimensions)”. (b): “Post-test classroom climate differences by dimensions.

However, post-test results for the simulation-based learning group demonstrated a significant improvement in the classroom. The mean classroom climate score for the experimental group increased to 3.5, compared to in the control group (t(128) = 6.70; p < 0.001). Cohen’s d = 0.3, indicating a medium effect size. The experimental group also showed significantly higher scores in specific categories such as student cohesion, involvement, cooperation, material environment, and relevance to learning (Figure 4).

A paired samples t-test further revealed that the classroom climate in the experimental group improved significantly after the integration of simulations compared to the pre-test phase (t(67) = 6.10; p < 0.001). This improvement was evident across most categories, including involvement, cooperation, fairness, and material environment. These results suggest that integrating simulations significantly enhances the overall classroom climate, fostering a more engaging and supportive environment for 8th-grade students during science lessons.

To examine potential gender effects, an independent samples t-test was conducted. As shown in Table 9, no statistically significant differences were found between males and females in terms of classroom climate (t(128) = 0.16; p > 0.05). This indicates that the integration of simulations had a similarly positive impact on classroom climate regardless of gender.

Table 9.

Mean and standard deviation of classroom climate among females and males and the t-test difference between them.

These results indicate some improvements in classroom climate and motivation among students in the experimental group, displaying the effectiveness of simulation-based learning in creating a dynamic and inclusive educational environment. Several components of classroom climate, including collaboration, involvement, and relevance to learning, showed marked improvement, reinforcing the benefits of integrating active and interactive teaching methods.

Simulation-based learning fosters a supportive environment where students feel encouraged to participate, express their opinions, ask questions, and collaborate with peers. This aligns with prior research, such as Calleja et al. (2020), which emphasized the importance of group activities, practical experiments, and independent research in improving classroom climate. Furthermore, Bratley et al. (1987) stress the role of simulations in enhancing student motivation, classroom climate, and overall academic achievements. From an educator’s perspective, these findings are particularly valuable. They demonstrate the potential of simulations and active methods to create more engaging and meaningful learning experiences for students. Additionally, fostering a safe and supportive learning environment that prioritizes equity and encourages student participation can significantly enhance the educational experience.

4.4. Exploring the Correlations Among the Three Variables- Achievement, Motivation and Classroom Climate- in the Context of Electrical Conduction in Aqueous Solutions and Electrolysis

A correlation model was developed to explore the relationships among three key variables: student achievement, 8th-grade students’ general motivation in science learning, and the overall classroom climate during science lessons. Table 10 provides a summary of the Pearson correlations between these variables.

Table 10.

Summary of Pearson correlations between the three variables (student achievement, students’ motivation and classroom climate).

The results indicate strong and statistically significant positive correlations between all three variables. Specifically, student achievement is positively correlated with motivation to learn science (r = 0.70, p < 0.001) and with classroom climate (r = 0.71, p < 0.001). Additionally, a significant positive correlation exists between classroom climate and motivation (r = 0.83, p < 0.001).

These findings suggest that students who experience higher motivation and enjoy a more positive classroom climate tend to achieve better academic outcomes. The correlation model offers valuable insights into the interconnectedness of these variables, demonstrating how motivation and a supportive learning environment contribute to academic success. When students feel motivated as a part of a positive classroom climate, they are more likely to invest effort and achieve higher learning outcomes. High motivation not only enhances students’ desire to learn but also strengthens their self-perception and academic progress. A positive classroom climate, characterized by support and collaboration, plays a vital role in fostering motivation and engagement. When students feel encouraged to express their ideas, ask questions, and collaborate with peers, they become more active participants in the learning process (Calleja et al., 2020). For instance, students who feel included in a supportive learning community are more willing to take extra steps to achieve their goals. Moreover, the strong positive relationships among achievements, motivation, and classroom climate have broader implications for teaching practices. Teachers can leverage students’ motivation and the positive classroom climate to design more engaging and meaningful learning experiences. By encouraging teamwork, fostering collaboration, and creating an open and supportive environment, teachers can further enhance learning outcomes. The findings also emphasize the importance of creating a safe and supportive classroom atmosphere. When students feel secure in expressing their opinions and engaging with peers, they become more motivated and engaged, which ultimately contributes to their academic success.

Overall, the results highlight the substantial impact of motivation and classroom climate on student achievement. A high level of motivation and a positive learning environment not only improve academic performance but also promote an enriched and dynamic learning experience for students. These insights affirm the importance of integrating strategies that enhance both motivation and classroom climate to achieve optimal learning outcomes.

5. Limitations

While the study’s results are promising, it has limitations that should be acknowledged. The relatively small sample size restricts the generalizability of the findings to broader populations, limiting the study’s applicability to other educational contexts. A second limitation concerns the possibility of a ceiling effect in the achievement measures. The pre-test scores were high across both groups, which may have reduced the sensitivity of the instrument to detect additional progress, especially among higher-achieving students. Future studies would benefit from using pre-tests with a wider difficulty range or including open-ended performance tasks that can better differentiate higher-level understanding. Additionally, the scope of the intervention was confined to the topic of electrical conductivity in aqueous solutions, leaving other scientific topics unexplored and raising questions about the potential impact of simulations on different subject areas. Furthermore, an ethical consideration arises from the fact that students in the control group did not receive the benefits of simulation-based instruction, which may pose concerns about equity in access to innovative teaching methods. These limitations point out the need for further research to expand the sample size, explore additional topics, and address ethical considerations in similar studies.

6. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that integrating simulations into teaching electrical conductivity in aqueous solutions and electrolysis significantly enhances student achievement, learning motivation, and classroom climate. Students in the experimental group reported feeling more engaged and motivated to learn due to the interactive nature of simulation-based instruction, which allowed them to connect theoretical concepts with practical applications.

The findings lend strong support to the development and refinement of educational tools that leverage simulations and interactive technologies, as these tools promote active engagement, enable students to experiment with complex scientific processes, and foster a deeper understanding of content. Simulation-based teaching creates a dynamic and practical learning environment that enhances student engagement and deepens their understanding of challenging topics. Simulations not only improve cognitive outcomes, such as academic performance, but also positively influence emotional aspects, including motivation and classroom climate. Furthermore, the study establishes a strong positive relationship between motivation, achievement, and classroom climate, underscoring the importance of fostering a supportive and secure learning environment to maximize student success.

While gender did not significantly impact achievement, motivation, or classroom climate, students with lower initial performance experienced the greatest benefits from the integration of simulations in the teaching process. This finding suggests that simulation-based learning is inclusive, offering equal benefits to all students regardless of gender. Furthermore, the results confirm that higher motivation levels are closely linked to better academic performance and a more positive classroom environment, emphasizing the crucial role of motivation in the learning process.

The findings of this study have significant implications for teaching and learning in science education. First, understanding the impact of technology on student learning equips educators and policymakers with valuable insights for developing more effective teaching strategies. By integrating simulations into lesson plans, teachers can make the learning process more engaging, interactive, and impactful. This approach encourages active participation and helps students connect theoretical knowledge with practical applications, transforming how scientific concepts are taught.

Finally, the study emphasizes the role of simulations in boosting students’ motivation to learn, which is strongly correlated with improved academic outcomes and a positive classroom climate. The insights from this research can inform the development of programs and teaching approaches that prioritize student enthusiasm and active involvement. Additionally, by identifying the connections between motivation, classroom climate, and achievement, the findings offer a framework for predicting academic outcomes and tailoring interventions to support students who may benefit most from simulation-based learning.

The integration of simulations into science education has the potential to transform teaching and learning. By making learning more engaging, interactive, and inclusive, simulations offer a pathway to bridge achievement gaps, increase student motivation, and create positive classroom climates. As supported by previous studies (Bratley et al., 1987; Calleja et al., 2020), these tools provide opportunities for students to develop deeper understanding and practical skills, preparing them for academic and professional success. Moving forward, educators and policymakers should embrace these findings to integrate simulation-based tools into curricula, develop innovative teaching methods, and create supportive and enriching learning environments that empower students to excel.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.B. and N.M.; methodology, A.B.; formal analysis, A.B., O.G. and N.M.; investigation, A.B. and N.M.; data curation, A.B. and N.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.B. and O.G.; writing—review and editing, O.G. and A.B.; project administration, A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Arab Academic College for Education in Israel-Haifa (protocol code AACE-S8-17102024 and 17 October 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data cannot be accessed publicly because the Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval did not encompass authorization for public dissemination. Thus, the data remain restricted and are not available for public review or distribution. Interested parties may request private access by contacting the corresponding author directly.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Afari, E., Aldridge, J. M., Fraser, B. J., & Khine, M. S. (2013). Students’ perceptions of the learning environment and attitudes in game-based mathematics classrooms. Learning Environments Research, 16(1), 131–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aires, F. K. F., de Sousa, A. M. F., Batista, M. d. C., Narciso, R., Sousa, D. B., & Ramalho, R. d. A. (2024). Virtual worlds the use of simulations for science teaching. ARACÊ, 6(2), 1618–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi, I. A. (2020). Predicting reading comprehension in Arabic-speaking middle schoolers using linguistic measures. Reading Psychology, 41(2), 87–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avidov-Ungar, O., & Iluz, A. (2015). Driving forces and inhibiting forces in integrating ICT among teacher educators in teacher training colleges. In A. Y. Eshet-Alkalai, A. C. Blau, N. Geri, Y. Kalman, & V. Silber-Varod (Eds.), Proceedings of the 10th Chais conference for the study of innovation and learning technologies: The learning man in the technological era. The Open University. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Beal, M. D., Kinnear, J., Anderson, C. R., Martin, T. D., Wamboldt, R., & Hooper, L. (2017). The effectiveness of medical simulation in teaching medical students critical care medicine: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Simulation in Healthcare, 12(2), 104–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratley, P., Fox, B. L., & Schrage, L. E. (1987). A guide to simulation (2nd ed.). Springer Science & Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, K. A., Greenbowe, T. J., & Hand, B. M. (2020). Implementing the science writing heuristic in the chemistry laboratory. Journal of Chemical Education, 83(7), 1032–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calleja, J. L., Soublette Sánchez, A., & Radedek Soto, P. (2020). Is clinical simulation an effective learning tool in teaching clinical ethics? Medwave, 20(2), e7824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cant, R. P., & Cooper, S. J. (2017). Use of simulation-based learning in undergraduate nurse education: An umbrella systematic review. Nurse Education Today, 49, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorfberger, S., & Carmi, A. (2017). The impact of the national ICT program on teachers’ attitudes towards technology use. Studies in Education, 15(16), 170–185. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Eccles, J. S., & Roeser, R. W. (2011). Schools as developmental contexts during adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21(1), 225–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekmekci, A., & Gulacar, O. (2015). A case study for comparing the effectiveness of a computer simulation and a hands-on activity on learning electric circuits. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics Science and Technology Education, 11(4), 765–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, B. J., & Walberg, H. J. (1982). Assessment of learning environments: Manual for learning environment inventory (LEI) and my class inventory (MCI). Western Australian Institute of Technology. [Google Scholar]

- Ghavifekr, S., Kunjappan, T., Ramasamy, L., & Anthony, A. (2016). Teaching and learning with ICT tools: Issues and challenges from teachers’ perceptions. Malaysia Online Journal of Educational Technology, 4(2), 38. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, J. K., & Treagust, D. F. (2009). Multiple representations in chemical education. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glynn, S. M., Taasoobshirazi, G., & Brickman, P. (2009). Science motivation questionnaire: Construct validation with nonscience majors. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 46(2), 127–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goff, D. A., Pratt, C., & Ong, B. (2005). The relations between children’s reading comprehension, working memory, language skills and components of reading decoding in a normal sample. Reading & Writing, 18(7–9), 583–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, A. G., & Treagust, D. F. (2000). A typology of school science models. International Journal of Science Education, 22(9), 1011–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, T., Langevin, J., & Sun, K. (2018). Building simulation: Ten challenges. Building Simulation, 11(5), 871–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Immordino-Yang, M. H. (2011). Implications of affective and social neuroscience for educational theory. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 43(1), 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inbal-Shamir, T., & Kali, Y. (2007). ICT-based teaching—A way of life or a burden for the teacher? In Y. Eshet, A. Caspi, & Y. Yair (Eds.), The learning man in the technological era: Proceedings of the Chais conference on learning technologies research (pp. 174–180). The Open University. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, T. C., & Kirby, J. R. (2006). The contribution of naming speed to the simple view of reading. Reading & Writing, 19(4), 339–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnstone, A. H. (1991). Why is science difficult to learn? Things are seldom what they seem. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 7(2), 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, C., Durfee, D., McKagan, S. B., & Perkins, K. (2021). Supporting inquiry-based learning with PhET simulations: Design principles and classroom strategies. Journal of Chemical Education, 98(4), 1203–1213. [Google Scholar]

- Lonka, K., & Ketonen, E. (2012). How to make a lecture course an engaging learning experience? Studies for the Learning Society, 2(3), 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Education. (2022). Ministry of education website, teaching staff portal, pedagogical space. Available online: https://pop.education.gov.il/tchumey_daat/mada-tehnologia/chativat-beynayim/noseem_nilmadim/electrical-circuit/ (accessed on 23 July 2023). (In Hebrew)

- Moore, E. B., Herzog, T. A., & Perkins, K. K. (2014). Interactive simulations as conceptual models in chemistry instruction. Journal of Chemical Education, 91(8), 1191–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadakis, S., Kiv, A. E., Kravtsov, H. M., Osadchyi, V. V., Marienko, M. V., Pinchuk, O. P., Shyshkina, M. P., Sokolyuk, O. M., Mintii, I. S., Vakaliuk, T. A., Striuk, A. M., & Semerikov, S. O. (2023, December 22). Revolutionizing education: Using computer simulation and cloud-based smart technology to facilitate successful open learning. CEUR Workshop Proceedings, Kyiv, Ukraine. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins, K. K., Adams, W. K., Pollock, S. J., Finkelstein, N. D., & Wieman, C. E. (2006). PhET: Interactive simulations for teaching and learning physics. The Physics Teacher, 44(1), 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podolefsky, N. S., Moore, E. B., & Perkins, K. K. (2010). Implicit scaffolding in interactive simulations: Design strategies to support multiple educational goals. AIP Conference Proceedings, 1289(1), 115–118. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, D., & Greene, L. (2011). The theatre of high-fidelity simulation education. Nurse Education Today, 31(7), 694–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, T., Bilas, P., Buliung, R., & El-Geneidy, A. (2020). A scoping review of accessible student transport services for children with disabilities. Transport Policy, 95, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh-Pillay, A. (2024). Exploring science and technology teachers’ experiences with integrating simulation-based learning. Education Sciences, 14(8), 803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankiewicz, A. I., & Nigar, H. (2020). Beyond electrolysis: Old challenges and new concepts of electricity-driven chemical reactors. Reaction Chemistry & Engineering, 5(6), 1005–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stinken-Rösner, L. (2020). Simulations in science education–status quo. Progress in Science Education (PriSE), 3(1), 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taber, K. S. (2002). Chemical misconceptions: Prevention, diagnosis and cure: Volume I: Theoretical background. Royal Society of Chemistry. [Google Scholar]

- Vlachopoulos, D., & Makri, A. (2017). The effect of games and simulations on higher education: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 14(1), 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waleed, A. (2009). The perception of teachers and student teachers at Al-Qasemi College regarding the integration of information technologies in teaching and the influencing factors—A case study. Jami’a, 13, 407–446. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).