Abstract

This systematic review examines how translanguaging has been integrated into educational assessment, a domain historically dominated by monolingual norms. Drawing on 33 empirical studies published between 2012 and 2023, we employed an inductive–deductive coding approach to analyze how translanguaging is enacted across assessment types and its implications for teaching, learning, and equity. The literature was concentrated in North America. Findings reveal affordances of translanguaging assessments including more authentic demonstrations of knowledge, deepen content learning, affirm multilingual identities, and reduce linguistic anxiety and challenges including perceptions of illegitimacy, systemic policy constraints, and resource inequities. We argue that translanguaging provides a transformative framework for reimagining assessment as a socially just practice that validates multilingual repertoires. To capture the varied engagements with equity, we conceptualize translanguaging assessment as an epistemological and political stance along a spectrum of justice. The spectrum ranges from access and inclusion to structural transformation to highlight how scholars frame translanguaging within assessment as descriptive practice, pedagogical equity, political resistance, and systemic reimagining. We call for more geographically diverse and methodologically varied research to sustain translanguaging’s impact and inform systemic change.

1. Introduction

The term “assessment” originated from the Latin word assidere—“to sit beside,” referring to a teacher sitting with their students to ascertain how to best support them on their learning journey. It indicates a close relationship and a sharing of experience. However, while many assessments have “good intentions” to measure student learning and inform instruction, they are often designed from a monoglossic, deficit-oriented orientations. Such assessments function as dismissive of multilingual students’ cultural and linguistic funds of knowledge which serves to maintain power structures that privilege standardized and national languages. As a result, these practices, often in conjunction with other structural and political forces (e.g., restrictive language-in-education policies), have exacerbated existing inequities and further contributed to the historic, systemic marginalization of language-minoritized multilinguals (Schissel, 2019). Indeed, assessment practitioners have only more recently begun to take seriously the task of meaningful inclusion of test-takers’ linguistic diversity in assessment development processes (Schissel, 2025).

The struggles in the field of assessment to cultivate dynamic environments with inclusive are rooted in monoglossic language ideologies. Monoglossic language ideologies are invested in the oppression of linguistic diversity, the promotion of linguistic purism, and the maintenance of power structures that privilege particular language varieties (e.g., standard languages, national languages; García & Li, 2014). Such ideologies are found in other areas of education as well. Language education policies about the medium of instruction across different areas of the world have often enforced strict separation of languages during instruction. In dual language bilingual education programs in the United States, a certain percentage of the instruction is often mandated in a specific language per day or in postcolonial contexts such as South Africa, instruction transitions from English as a subject to English as the medium of instruction for all subjects at grade 4.

Contrasting monoglossic perspectives are heteroglossic language ideologies that cultivate spaces for linguistic diversity to thrive, often in opposition to existing power structures. Building on this orientation, researchers and educators seeking equitable and just assessments that center the voices of multilingual test-takers, especially those from marginalized communities (Gorter & Cenoz, 2017; Shohamy, 2011), have turned to a growing area of scholarship that uses an asset-based, heteroglossic perspective: translanguaging. Translanguaging research has expanded exponentially across global educational contexts, highlighting its theoretical, pedagogical, and increasingly epistemological potential to challenge dominant monolingual ideologies and redefine what counts as legitimate knowledge and participation in education, with important implications for assessment (García & Kleyn, 2016; Hamman-Ortiz et al., 2025; Zheng & Qiu, 2024).

As assessment practices across the world have begun to integrate translanguaging rooted in heteroglossia and social justice (Seltzer & Schissel, 2025; Van Viegen et al., in press), we found it timely to conduct an analysis of the available research in this area. Assessment approaches that use translanguaging, we posit, may represent some of the first meaningful and affirming understandings of linguistic diversity within assessments--combating decades of modern practices that have been marginalizing and discriminatory.

Our literature review of empirical studies of translanguaging and assessment provides an overview and synthesis of the impact and implications of this new area of research. Our paper focuses on the following two research questions: (1) What is the current landscape of translanguaging assessment research? and (2) What are the affordances and challenges of translanguaging within assessments? In this paper, we begin by detailing the theory of languaging with respect to translanguaging that we used to identify studies for this literature review. We then provide an overview of our methods and procedures for the literature review before reporting our findings with respect to our research questions. We conclude with a discussion of the past, present, and potential future implications of this scholarship.

2. Conceptual Framework

Translanguaging represents a paradigmatic shift in how language is conceptualized and how multilingual students are supported in educational contexts, including assessment. Traditionally, assessments have been designed from monoglossic perspectives, which treat languages as discrete, bounded systems and privilege standardized national languages as the default medium of evaluation (Shohamy, 2011). Such approaches can systematically disadvantage language-minoritized students by invalidating their full linguistic repertoires and reinforcing linguistic hierarchies tied to colonial and modernist-era structuralist ideologies (Makoni & Pennycook, 2007). Adopting a Rawlsian (2001) justice-as-fairness lens, we view language background as social difference rather than as a barrier; accordingly, fair assessment practices must not conflate evidence of learning with conformity to a single standardized code. While this Rawlsian orientation underscores fairness and access, we also acknowledge that educational justice extends beyond procedural equity. Translanguaging assessment must engage broader dimensions of justice—including recognition, representation, and epistemic transformation (Fraser, 2009; García & Leiva, 2014; Heugh et al., 2017)—to fully capture the relational, cultural, and, structural dimensions of equity in multilingual education.

As a theory, translanguaging provides a heteroglossic, more socially just alternative, recognizing the fluid and dynamic nature of multilingual speakers’ language practices. Grounded in Bakhtin’s concept of heteroglossia, translanguaging posits that multilingual individuals do not operate within separate, compartmentalized linguistic codes but rather draw upon an integrated linguistic and semiotic repertoire (García & Li, 2014). For language-minoritized students especially, this means that translanguaging is not just about using multiple named languages but about asserting their epistemologies, identities, and ways of knowing in educational spaces where their linguistic resources have historically been marginalized (Arias & Schissel, 2021).

As a pedagogical approach, translanguaging leverages students’ full linguistic, cultural, and semiotic repertoires to facilitate meaningful learning (Li & García, 2022). Rather than tokenistically including home languages, it repositions multilingual students as knowledge producers, challenging deficit discourses that frame them as linguistically incomplete, in need of remediation, or languageless (Rosa, 2019). This shift is particularly crucial in assessment, a historically exclusionary space where multilingual students have been forced to conform to standardized linguistic norms that ignore their lived communicative practices (Sánchez, 1934; Schissel, 2019). By disrupting these paradigms, translanguaging offers a critical intervention in rethinking assessment as a more just and inclusive practice (García & Leiva, 2014). It has the potential to decolonize educational evaluation by challenging the dominance of monolingual, standardized measures of achievement and instead recognizing the full range of multilingual students’ meaning-making abilities, viewing multilingualism as the essence of validity for assessments (Schissel, 2019). García and Kleyn (2016) argue that translanguaging “enables a more socially just and equitable education for bilingual students” (p. 17). Integrating translanguaging into assessment design allows educators and researchers to reclaim assessment as a tool for equity rather than exclusion—one that, as its Latin root suggests, truly “sits with” students to support their learning.

As assessment practices worldwide increasingly incorporate translanguaging, a systematic review of existing research is both timely and necessary. While translanguaging has been widely explored in pedagogy (Hamman-Ortiz et al., 2025), its application in assessment remains understudied, particularly in terms of its interaction with educational equity. Our review examines the current landscape of translanguaging assessment research as well as the affordances and challenges of its integration. This synthesis aims to highlight sustainable practices, identify gaps, and contribute to ongoing conversations about reimagining assessment as a more inclusive and socially just process.

3. Methods

Zhongfeng and Jamie began the process for the systematic review by reviewing the guidance from Newman and Gough (2020) on systematic literature reviews in education and APA style JARS for inclusion criteria for qualitative research (American Psychological Association, 2023) to design our systematic review of research published on translanguaging and assessment. Newman and Gough recommend

- Developing a research question

- Designing a conceptual framework

- Constructing selection criteria

- Developing search strategies

- Selecting studies using the selection criteria

- Coding studies

- Assessing the quality of the studies

- Synthesizing study results to answer research questions

- Reporting findings (p. 6)

We closely followed this process and divided tasks among the research team. Zhongfeng coordinated the process. Zhongfeng and Jamie led steps 1–4 and Chia-Hsin and Jessica worked closely on steps 4–6. All members of the research team collectively contributed to steps 7–9. We detail the process below.

Guided by Zhongfeng and Jamie, Jessica began our systematic review of the intersection of translanguaging and assessment by engaging in a comprehensive search across two databases: Google Scholar and ERIC. These databases were chosen as they are widely known for capturing a broad spectrum of peer-reviewed articles and book chapters, particularly those related to education. Table 1 shows the original number of results from searching each database.

Table 1.

Original number of results for search terms in ERIC database and Google Scholar.

From these original 1056 results, Jessica excluded all items that did not fit the following criteria: empirical; journal article or book chapter published between 2012 and 2023 (the year in which our search was conducted); aligned with a heteroglossic theory of language; peer reviewed. Additionally, we excluded items that did not align with a heteroglossic and social justice-oriented approach to translanguaging. The team discussed any questions about inclusion based on this specific criterion until reaching consensus.1 For example, we excluded an article that discussed multilingual assessment, but not the intersection of translanguaging and assessment. To check if each article met the inclusion criteria, Jessica skimmed through the entire article, rather than just the abstract, to ensure that we did not eliminate articles that actually aligned, and that we did not include articles that only briefly mentioned translanguaging in assessment, but were empirically focused on a different topic. Table 2 shows the number of articles that remained for each search term per database after applying the inclusion criteria.

Table 2.

Number of items remaining for search terms in ERIC database and Google Scholar after applying the inclusion criteria.

Jessica compiled a list of the remaining titles and abstracts in a shared Google spreadsheet. Then, Zhongfeng and Jamie read through the titles and abstracts and identified articles that should also be disqualified based on the selection criteria and study quality. 37 articles met all selection criteria as agreed upon by all authors and were selected for coding. Four of these articles were later removed as more detailed coding demonstrated that they also failed to meet the inclusion criteria. More specifically, although these articles mentioned translanguaging and/or a heteroglossic perspective, they did not provide relevant data with respect to defining translanguaging, or implementing it as a theoretical framework or in assessment design. Ultimately, we analyzed 33 articles (see the PRISMA flow diagram).

We jointly established a preliminary codebook informed by both emerging patterns and the conceptual framework of translanguaging and assessment. For our coding process, we employed an inductive–deductive hybrid approach (Fereday & Muir-Cochrane, 2006). Chia-Hsin and Jessica identified excerpts from each article that aligned with elements of focus including how translanguaging was defined, number of participants, length of study, country/region, research methods, type of assessment (e.g., high-stakes/low-stakes, classroom-based, content area/language). Thematically, our inductive coding surfaced excerpts on washback on teaching/teachers and learning/students and deductive coding included the themes of social justice and equity regarding contextual constraints. Washback refers to the influence that testing exerts on instructional practices and learning processes, encompassing the ways in which assessments shape teaching approaches, learner behaviors, and curricular decisions within educational systems (Alderson & Banerjee, 2001; Alderson & Wall, 1993; Bachman & Palmer, 1996, 2010; Hughes, 1989). To assure coding consistency, Chia-Hsin and Jessica first completed coding for approximately 30% of the dataset (ten randomly chosen articles), beyond the 20% recommended by O’Connor and Joffe (2020) for initial code setting. Based on these independent codings, they calculated Cohen’s Kappa coefficients by code and by study to assess initial intercoder reliability (IRR), which measures independent agreement prior to discussion. Half of the coefficients by code and half of the coefficients by study met a minimum of 95% intercoder agreement per code (Campbell et al., 2013) which enhances the rigor of data analysis (O’Connor & Joffe, 2020). All Kappa values indicated an almost perfect agreement of 0.81 or higher (McHugh, 2012), with the lowest value by code being 0.85, and the lowest value by study being 0.86. For codes showing misalignment, we engaged in consensus discussions consistent with a socially mediated approach to coding, in which discrepancies are collaboratively examined and resolved through dialog and negotiation to ensure shared interpretation (Campbell et al., 2013). With this rate of intercoder agreement, we used the codebook to create a coder training. Chia-Hsin and Jessica then divided the remaining articles (n = 33) and coded the rest of the articles, noting any areas of ambiguity for full team review. The full team reviewed the final coding to ensure fidelity across coding of all articles.

After the coding process was complete, the team compiled descriptive statistics to examine the current landscape of translanguaging assessment research, followed by an examination of the affordances and challenges of translanguaging within assessment with respect to (1) washback and (2) social justice. The findings of this analysis are detailed below. A full table of selected 33 articles and their relevant information can be found in the Supplementary Material.

4. Findings

Our findings focus on answering our two research questions: (1) What is the current landscape of translanguaging assessment research? and (2) What are the affordances and challenges of translanguaging within assessments?

4.1. The Current Landscape of Translanguaging Assessment Research

To provide a comprehensive overview of research in the field, we begin by presenting general information about the selected studies in terms of (1) context and participants, (2) research methods, (3) assessment types, and (4) journal types. This helped us investigate what type of information has been researched, where the research was conducted, how it was conducted, and who the typical readership has been.

4.1.1. Context and Participants

We began our research by analyzing the geographical context within which studies were conducted as well as the number of participants involved. Table 3 below outlines the geographical contexts of the 33 empirical articles reviewed.

Table 3.

Geographical Context.

Most studies focus on North America (23 among 33 studies; 69.7%), with a majority focusing particularly on the United States. A growing number of studies address Asian contexts (8 among 33 studies; 24.2%), including Bangladesh, Israel, the Philippines, the UAE, Japan, and South Korea, with China featuring slightly more studies. Notably, very few studies are focused on Africa (2 among 33 studies; 6.06%) or Oceania (1 among 33 studies; 3.03%), and none are based in Europe. This finding was surprising, given that translanguaging first emerged in Europe, and the linguistic and cultural diversity of Africa would suggest that more research is warranted there. However, North America understandably dominates the research landscape as the birthplace of translanguaging pedagogy. The global distribution of studies suggests that translanguaging in assessment remains underexplored, particularly in settings characterized by rich linguistic and cultural diversity.

It is also important to determine the number of participants commonly involved in this type of research. As such, Table 4 breaks down the number of studies that involved different participant numbers.

Table 4.

Number of Participants.

Most studies involved 1–50 participants (75%). For studies involving more than fifty participants, several involved multiple smaller groups, such as a control and experimental group (Qureshi & Aljanadbah, 2022).

4.1.2. Research Method

Our investigation then led us to investigate important research method elements involved across studies. Table 5 demonstrates how many studies employed a qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods research design.

Table 5.

Research Method.

Among the 33 selected empirical studies, the major research method across all studies was a qualitative research design (23 out of 33, 70%). Nearly one-quarter of the studies adopted a mixed-methods paradigm (8 out of 33, 24%). Two employed a quantitative approach (6%). We argue that the methodological choices reflect the nature of translanguaging, which encompasses multiple ways of making meaning from experiences and learning that may not be fully captured through purely statistical methods.

Qualitative data in the reviewed studies were gathered through classroom observations, writing interventions, focus groups, and semi-structured interviews. In Oaxaca, Mexico, Schissel et al. (2021) used participatory action research (PAR) to co-design English–Spanish assessments with teachers, drawing on field notes, participant reflections, interviews, and student work to examine the impact of translanguaging. Similarly, Tian (2022b) employed participatory design research to co-develop translanguaging assessments with a Grade 3 Mandarin teacher in a one-way Mandarin–English dual language classroom, using observations, interviews, and student artifacts to show how translanguaging broadened opportunities for students to demonstrate their content and language learning. Shi and Rolstad (2022) conducted ethnographic content analysis in a Chinese kindergarten, analyzing how the teacher’s use of translanguaging in instruction and assessment supported children’s learning through storytelling, show-and-tell, and play. Burgess and Roswell (2020) employed ethnography to explore how multimodal translanguaging assessments empowered refugee and newcomer adults in Canada. Additional studies used case study (Fine, 2022; López-Velásquez & García, 2017) and multiple case study approaches (Ascenzi-Moreno & Seltzer, 2021; Noguerón-Liu & Driscoll, 2021), highlighting how qualitative inquiry continues to uncover the transformative potential of translanguaging across diverse assessment contexts.

Mixed-methods studies (Adamson & Coulson, 2015; Lopez, 2023a; Lopez et al., 2014, 2017, 2019; Morales et al., 2020; Schissel et al., 2018; Shohamy et al., 2022) yielded nuanced insights into translanguaging’s role across diverse educational contexts, capturing both measurable outcomes and students’ multilingual meaning-making. Studies also explored varied perspectives from students and educators, helping to assess the effectiveness and equity of translanguaging practices and inform inclusive, culturally responsive assessment policies. Two studies employed quantitative methods (Przymus & Alvarado, 2019; Qureshi & Aljanadbah, 2022). Przymus and Alvarado (2019) used bilingual language sample analysis with SALT (Systematic Analysis of Language Transcripts) software to examine content-based story retellings in a bilingual special education context. Using a quasi-experimental design, Qureshi and Aljanadbah (2022) quantitatively examined the effects of translanguaging on differences in reading comprehension under translingual and non-translingual conditions, with the translingual group allowed to use any language during reading tasks and the non-translingual group required to use only English.

We also documented the varying lengths of data collection and analysis. Table 6 provides information on the number of studies representing varying time periods.

Table 6.

Length of Study.

Almost half of the studies took place over the course of one year or less (16 out of 33, 48%). Of those, several (3 out of 33, 9%) of those took place at one moment in time (e.g., a focus group discussion or survey). Of the studies which did not specify a length of time (10 out of 33, 30%), they frequently involved multiple types of data collection, but did not specify the amount of time that data collection lasted.

4.1.3. Assessment Type

Table 7, Table 8, Table 9 and Table 10 below provide information on whether each published article was standardized or non-standardized, high-stakes or low-stakes, classroom-based or non-classroom based, and content area or language based.

Table 7.

Type of Assessment—Standardized or Non-Standardized.

Table 8.

Type of Assessment—High-Stakes or Low-Stakes.

Table 9.

Type of Assessment—Classroom Based or Non-Classroom Based.

Table 10.

Type of Assessment–Content Area or Language.

Overall, most assessments were non-standardized (24 out of 33, 73%), low-stakes (28 out of 33, 85%), and classroom-based (27 out of 33, 82%).

4.1.4. Publication Type

When examining research on translanguaging in assessment, it is important to consider the audiences reached through the dissemination of findings. Therefore, we took note of the type of publisher to better understand the intended reach and impact (see Table 11 below).

Table 11.

Type of Publisher.

The majority of published articles or chapters were found in applied linguistics publications (26 among 33, 78%), with several focusing on general education. Only two were published in the areas of science and technology (6%). This concentration reflects the strong roots of translanguaging research in applied linguistics, with emerging relevance across broader educational contexts.

4.2. Affordances and Challenges of Translanguaging Within Assessments

After describing the current landscape of research on translanguaging in assessment, we analyzed the findings of existing studies thematically in terms of washback across teaching and teachers and learning and learners. We then discuss the contextual constraints on translanguaging and assessment within social justice frameworks.

4.2.1. Washback on Teaching and Teachers

Washback on teaching and teachers revealed multiple affordances of translanguaging and assessment. Several studies demonstrate that using translanguaging can increase educators’ confidence and agency in fostering equitable learning environments (Buxton et al., 2022; Fine, 2022). For example, Fine’s case study of a 6th-grade science teacher illustrated how the teacher developed a stronger sense of agency in promoting linguistic equity as she deepened her translanguaging interpretive power through formative assessment. Translanguaging has also been shown to strengthen teacher–student and teacher–family relationships (Fine, 2022; Noguerón-Liu & Driscoll, 2021; Shi & Rolstad, 2022). Shi and Rolstad (2022) emphasized the “transformative nature of translanguaging” (p. 21) in fostering trust-based connections between students and teachers. In addition, Greenier et al. (2023) reported that ten primary English teachers in China used translanguaging in formative assessments to support student engagement, meaning-making, collaboration, and empowerment and enhance teachers’ ability to provide meaningful feedback.

Translanguaging in assessment has also helped teachers better understand what multilingual learners know and identify areas needing support (Lopez et al., 2014; Shi & Rolstad, 2022; Wang & East, 2023). Studies described how the inclusion of translanguaging improves the quality of assessment data, which informed teachers’ instructional decisions (Tian, 2022b; Gandara & Randall, 2019; Przymus & Alvarado, 2019). For instance, Przymus and Alvarado argued that incorporating translanguaging into state content standard–based story retells, combined with classroom observations, can improve the evaluation process for identifying multilingual students eligible for special education services.

4.2.2. Washback on Learning and Learners

Findings centered around the washback on learning and learners were the most prevalent across the studies. Translanguaging in assessment has demonstrated substantial potential to enhance multilingual learners’ language development. In translanguaging classrooms, multilingual students utilized their full language resources. Bauer et al. (2020) observed that African American and Latinx dual language learners benefited from multidimensional assessments that redefined language and literacy evaluation by recognizing their linguistic and experiential assets. Similarly, Lopez (2023a, 2023b) demonstrated that integrating multilingual practices in English proficiency tests enabled students to access multiple entry points for demonstrating their skills, bridging home and assessment languages (García et al., 2017). Adamson and Coulson (2015) also observed that awareness of translanguaging enhanced authenticity and relevance of assessment tasks, which was reported to improve students’ writing development. Conversation-based assessments, when paired with translanguaging, further fostered interactive and supportive learning environments for multilingual learners’ learning of English (Lopez et al., 2017).

Translanguaging and assessments explored language development and deepening students’ understanding of disciplinary content as intertwined. Establishing multilingual-friendly assessment spaces enables learners to mobilize all their linguistic resources to construct meaning and deepen content learning (Buxton et al., 2022; Lopez et al., 2019). This flexibility allows for responses not typically available in monolingual settings (Greenier et al., 2023). Translanguaging in assessments validates students’ fluid language practices (Shi & Rolstad, 2022; Noguerón-Liu & Driscoll, 2021) and provides a holistic lens on multilingual learners’ academic and communicative language use. These practices enrich students’ disciplinary understanding (Greenier et al., 2023; Tian, 2022a, 2022b). For instance, Lopez et al. (2014) found that multilingual learners used English, Spanish, and mathematical language to effectively demonstrate their knowledge in math. Likewise, Buxton et al. (2022) and Przymus and Alvarado (2019) noted student growth in language and content learning when assessments supported all linguistic resources.

Sustained engagement also intersects with identity expression. Enabling students to use their full communicative repertoires fosters stronger academic identities (Przymus & Alvarado, 2019). And translanguaging pedagogical shifts enable students to navigate academic and personal identities. When students are empowered to make linguistic and cultural choices in assessment, they do more than complete tasks—they actively assert their voices and perspectives within academic contexts. In an interdisciplinary project across Chinese language arts and social studies, Tian (2022b) found that multilingual learners not only deepened their content understanding, but also developed a stronger, more nuanced sense of their bilingual identities. These learners were positioned not as deficient language users, but as creative multilingual agents. Translanguaging fosters inclusive and identity-affirming assessment environments that enable learners to move between unfamiliar and familiar language resources, strengthening their ability to reason abstractly and express knowledge authentically (Buxton et al., 2022). Notably, such identity work reinforces engagement, as learners become more willing to take risks and invest in their academic growth (Schissel et al., 2021).

Additionally, translanguaging assessments alleviated language-related anxiety and enhance student engagement. Lopez (2023a, 2023b) observed that when instructions were delivered in students’ home languages, learners performed more confidently and demonstrated emerging skills in the target language. By the same token, Shohamy et al. (2022) found that bilingual assessments enhanced test legitimacy, reduced cognitive load, and promoted more positive emotional responses. The benefits were particularly pronounced for students with lower proficiency levels (Noguerón-Liu et al., 2020). In one case, Adamson and Coulson (2015) integrated Japanese readings into writing tasks, leading to improved outcomes among novice learners. Awareness of translanguaging practices helped students become more invested in their writing and generated content that reflected local and personal relevance. Wang and East (2023) noted similar benefits in digital L2 writing, and even university professors reported reduced anxiety and cognitive strain when using their L1 in listening assessments (Baker & Hope, 2019).

However, while the reviewed literature largely affirmed the benefits of translanguaging assessment for learners and learning, it also highlights implementation challenges. For example, Wang and East (2023) pointed out several student-noticed constraints of translanguaging assessment, revealing how prior educational experiences and dominant ideologies shape learner perceptions. Some students expressed skepticism about digital, multimodal composition tasks, finding the shift from monolingual, handwriting-based assessments to translanguaged digital formats unexpected, unnecessary, and inauthentic. In certain contexts, test-takers also concerned that translanguaging would be viewed as a lowering of linguistic standards, particularly where the maintenance of “pure” language forms is tied to sociopolitical ideologies, as in French-medium Canadian institutions (Baker & Hope, 2019). Overarching contextual constraints were also identified as a major challenge in translanguaging and assessment.

4.2.3. Contextual Constraints on Translanguaging and Assessment Within Social Justice Frameworks

As described above, translanguaging assessment represents a compelling approach that has empowered multilingual learners and their teachers to reimagine what counts as valid knowledge. Translanguaging assessment, nonetheless, faces deep structural constraints. A growing body of research highlighted the persistence of monolingual ideologies that restrict teachers’ ability to enact translanguaging in assessment (López-Velásquez & García, 2017; Macawile & Plata, 2022; Morales et al., 2020; Rafi, 2023; Schissel et al., 2021). López-Velásquez and García (2017) found that an English-dominant school environment undermined biliteracy development, prioritizing English reading and marginalizing the value of home languages. The authors expressed concern that family support alone could not counter these hegemonic school practices. Teachers have often struggled to implement translanguaging practices amid the pressures of monolingual-centric school cultures and broader educational politics. Schissel et al. (2021) documented the tension educators experienced when navigating between innovative assessment practices and monolingual-centric school policies, especially when working with marginalized student populations. Teachers called for greater institutional support and resources to engage in equitable, linguistically responsive assessment.

Resource access inequities further complicated implementation. Lopez (2023a) noted that students from low-income communities often lack access to digital tools necessary for online assessments and that unstable internet connections and outdated equipment contribute to unequal participation. Additional issues with resources included the need for more multilingual staff (Lopez et al., 2017, 2019; Lopez 2023a; Shi & Rolstad, 2022), scheduling challenges (Lopez et al., 2019; Lopez, 2023a; López-Velásquez & García, 2017), and the availability of authentic assessment tools (Kabuto, 2017). Some teachers found it more feasible to implement translanguaging in everyday instruction than in assessment due to fewer constraints (Buxton et al., 2022). As Buxton et al. noted, “a particular challenge to this work is the need to disrupt the current rigid structures guiding summative assessments that limit science teachers’ sense of agency to take instructional risks and to embrace ecological practices of multilingual meaning making” (p. 34). These logistical barriers reflected broader patterns of structural disadvantage and reveal the infrastructural gaps that intensify inequities in student assessment participation.

Other structural constraints, such as rigid assessment policies (Ascenzi-Moreno & Seltzer, 2021), also were described in the literature. In the United States, Ascenzi-Moreno and Seltzer found that school-imposed assessment parameters restricted teachers’ ability to recognize multilingual students’ reading strengths and, in some cases, reinforced deficit-based perceptions. A perceived need to uphold the “neutrality and validity of assessments” (p. 485) further discouraged teacher support for translanguaging-based adaptations. They explained that what counted as “success” in these institutional frameworks—often measured through limited, English-dominant benchmarks—may not align with the more expansive demonstrations of competence shown in translanguaging assessments. In Bangladesh, Rafi (2023) described how translanguaging-based achievements may conflict with institutionalized notions of linguistic competence, which were shaped by broader societal ideologies privileging standard language use. This disconnect exposed how dominant ideologies shape assessment legitimacy and marginalize alternative ways of knowing.

Integrating translanguaging into standardized assessments has remained a complex and underexplored endeavor. Buxton et al. (2022) noted that while teachers were generally eager to support students in using their complete linguistic and cultural repertoires—especially in content areas like science—this support was often far easier to implement during daily instruction than within rigid summative frameworks. Gandara and Randall (2019) reported on translanguaging within test administration with standardized testing of mathematics in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Although they concluded that this approach was more appropriate than traditional monolingual methods, they also discussed the issues around the incongruency of flexible translanguaging practices and standardized testing procedures, in particular the ways in which translanguaging was better aligned with local languaging practices.

These examples illuminated inherent tensions between the fluid, context-responsive design of translanguaging assessments and the constraints of standardized assessments. They pointed to a persistent methodological and policy dilemma in the field—how to reconcile the inclusive, learner-centered aims of translanguaging with the accountability-driven design of standardized assessments. These cases highlighted the need to address the infrastructural, linguistic, and policy barriers that currently hinder translanguaging practices in assessment, including the scarcity of linguistically diverse evaluators and appropriate materials in underrepresented or endangered languages (Kabuto, 2017).

4.3. A Discussion of a Spectrum of Justice: Unpacking Equity in Translanguaging-Based Assessment

The integration of translanguaging in assessment holds transformative potential for advancing equity in multilingual education. Yet across the literature, studies engage with social justice, equity, and power in varied and evolving ways. Rather than dividing this work into a binary of “justice-oriented” versus “not,” we can better understand it along a dynamic spectrum—from inclusive access to structural transformation. This framework highlights how scholars can conceptualize translanguaging in assessment, offering a generative view of both the momentum and the tensions in the field. Importantly, this spectrum does not exist in a vacuum; it intersects with diverse theoretical traditions in justice studies that sometimes align and sometimes conflict. While some perspectives emphasize fairness and inclusion within existing systems (Rawlsian, 2001), others call for epistemic and structural transformation that redefines what counts as knowledge, language, and learning (Fraser, 2009).

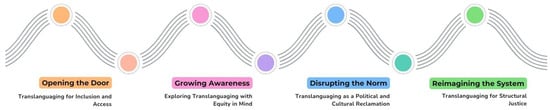

We present the contributions as a continuum—each with distinct strengths and possibilities for growth (see Figure 1). Across the spectrum, we see a shared commitment to honoring multilingual students’ full linguistic repertoires, even as the depth of engagement with justice-oriented frameworks and existing structural and systemic hierarchies varies.

Figure 1.

Social Justice in Translanguaging-based Assessment.

4.3.1. Opening the Door: Translanguaging for Inclusion and Access

Studies in this category lay the groundwork for more inclusive assessment by illustrating how translanguaging can enhance students’ ability to demonstrate their knowledge. This work shifts the focus away from monolingual norms and embraces students’ full linguistic resources as legitimate and valuable. For instance, Lopez (2023a) and Guzman-Orth et al. (2019) show how bilingual learners use their linguistic repertoires in pilot assessments to express their thinking more fully. Similarly, Adamson and Coulson (2015) find that translanguaging improves the authenticity of academic writing in Japanese-English CLIL classrooms.

These contributions are essential in challenging the exclusionary nature of many current assessments. Yet, the framing of translanguaging in these studies often remains descriptive and outcome focused, emphasizing performance or comprehension gains without explicitly addressing the sociopolitical conditions that marginalize certain language practices. The concept of equity is present, but not always central.

4.3.2. Growing Awareness: Exploring Translanguaging with Equity in Mind

This cluster of studies reflects a growing critical awareness of how language ideologies shape assessment. These scholars acknowledge the limitations of monolingual frameworks and explore how translanguaging can foster student engagement, creativity, and agency. For example, Fine (2022) documents how a science teacher co-designs translanguaging-informed assessment and develops what she calls translanguaging interpretive power—the ability to notice and make sense of multilingual students’ contributions. Greenier et al. (2023) and Wang and East (2023) also highlight the pedagogical creativity of teachers using translanguaging in classroom-based assessments.

These studies are significant in expanding the professional knowledge and reflective capacity of educators. They point toward equity without always naming it as a driving force. Often, they treat justice as a potential outcome of good practice rather than as a foundational principle and may not of interrogate the structural forces that constrain teacher agency or student expression.

4.3.3. Disrupting the Norm: Translanguaging as a Political and Cultural Reclamation

Here, translanguaging is framed explicitly as a tool for resistance, identity affirmation, and ideological disruption. These studies recognize assessment as inherently political and argue that it must be reimagined to challenge dominant racial and linguistic hierarchies. Ascenzi-Moreno and Seltzer (2021) draw on raciolinguistic perspectives to show how reading assessments often marginalize bilingual students of color, calling for critical translingual teacher learning. Tian (2022a, 2022b), through participatory design research in Mandarin-English dual language classrooms, uses translanguaging allocation policies to resist monolingual ideologies and protect minoritized languages. Similarly, Rafi (2023) explores how instructors in Bangladeshi universities redesign assessments to counter English hegemony and elevate Bangla.

These studies push the field forward by naming systemic oppression and offering translanguaging as a means of cultural and educational justice. However, while powerful in critique, they sometimes under-articulate the practical conditions—policy shifts, leadership support, material resources—needed to implement and sustain such approaches at scale.

4.3.4. Reimagining the System: Translanguaging for Structural Justice

At the transformative end of the spectrum are works that re-envision assessment as a lever for structural change. These studies propose justice-oriented frameworks that not only validate students’ multilingual repertoires but also redistribute power in schools and institutions. García et al. (2012) introduce the concept of transcaring—an ethic of care that fosters third spaces, or hybrid learning environments that transcend rigid boundaries between languages, cultures, and ways of knowing. In these spaces, translanguaging becomes a relational practice rooted in solidarity and belonging, nurturing a humanizing assessment approach (Schissel, 2025). Meanwhile, Shohamy et al. (2022) and Heugh et al. (2017) directly address the colonial legacies of monolingual assessment systems, advocating for multilingual assessments that reflect the lived realities of linguistically diverse students. These scholars critically interrogate prevailing assumptions about what constitutes valid knowledge and the authorities that determine such standards.

While these studies offer visionary models for justice-centered education, they also reveal the challenges of implementation. Deeply entrenched monolingual ideologies, standardized testing policies, and institutional inertia continue to limit transformative change. Yet these works remind us what is possible when assessment is reimagined not as a tool of compliance, but as a practice of liberation.

Across this continuum, different conceptions of justice surface and occasionally collide. A Rawlsian lens of justice as fairness (Rawlsian, 2001) foregrounds procedural equity—ensuring that all learners have comparable opportunities to demonstrate their knowledge—yet it may leave intact the structures that privilege standardized linguistic norms. In contrast, Fraser’s (2009) multidimensional framework of redistribution, recognition, and representation shifts attention to systemic inequities that shape who and what is valued in assessment. Finally, decolonial and critical race perspectives (e.g., García & Leiva, 2014; Heugh et al., 2017) emphasize epistemic justice, calling for the dismantling of colonial hierarchies that define legitimate knowledge and linguistic legitimacy. These frameworks reveal productive contradictions: what appears “fair” under one model may reproduce inequity under another. Translanguaging assessment, situated at the intersection of these paradigms, thus becomes a site of theoretical negotiation—seeking both access within and transformation beyond existing systems.

This spectrum overall offers a way to honor the full range of scholarly contributions while inviting deeper engagement with the sociopolitical dimensions of assessment. Translanguaging is not a neutral pedagogical technique; it is an ideological stance grounded in the belief that students’ languages, identities, and lived experiences are sources of strength and insight. As researchers and educators, we ask: Are our assessments merely accommodating multilingualism, or are they actively dismantling the systems that marginalize it? Moving toward the transformative end of the spectrum means designing assessments that reflect, respect, and respond to the communities they serve—laying the groundwork for more equitable and just educational futures.

5. Discussion

Our systematic review builds upon and extends the expanding body of translanguaging research (e.g., Hamman-Ortiz et al., 2025) by focusing specifically on the underexplored domain of assessment. While translanguaging has gained significant traction as a pedagogical approach across multilingual classrooms (e.g., García & Kleyn, 2016; Li & García, 2022), assessment remains one of the most monolingually entrenched areas of education (Shohamy, 2011). Translanguaging pedagogy has long been positioned as a means to affirm multilingual learners’ identities, promote equitable participation, and disrupt deficit discourses, yet assessment continues to lag behind—often reinforcing the very hierarchies that translanguaging seeks to dismantle. Our review addresses this critical gap by examining not only how translanguaging is taken up in assessments but also how these practices interact with broader ideologies, institutional structures, and justice goals.

5.1. Looking Beneath the Surface: Patterns and Silences

Our review of 33 empirical studies revealed promising developments as well as persistent tensions. The prevalence of qualitative, classroom-based, and small-scale studies reflects the localized, relational nature of translanguaging assessment. Teachers in these studies often exercised considerable autonomy in classroom assessment contexts, enabling them to draw on students’ full linguistic repertoires and build stronger connections between home and school literacies. Yet few studies examine standardized or policy-driven contexts, reflecting structural and epistemological barriers that make translanguaging difficult to operationalize at scale. As Chalhoub-Deville (2019) notes, multilingual assessments represent disruptive innovations that challenge the incremental adjustments typical of traditional testing. Designing tasks that allow test-takers to use their full repertoires—and determining how to score such performances—stretch prevailing notions of validity and reliability. While applied linguistics increasingly embraces heteroglossic understandings of multilingualism, standardized testing systems rely on parameters, scales, and comparability logics that conflict with the fluidity of languaging (Schissel et al., 2019). These tensions help explain why translanguaging assessment encounters systemic resistance: it disrupts the epistemologies of language and measurement that underlie large-scale testing.

Regionally, North America—particularly the United States—remains overrepresented, despite translanguaging’s origins in Welsh bilingual education and its growing relevance across the Global South. This imbalance reflects not only broader academic publishing hierarchies but also epistemic and infrastructural inequities that influence whose research becomes visible. For instance, the underrepresentation of Global South contexts may stem from structural barriers such as publishing language, journal indexing, and epistemic hierarchies privileging English-medium scholarship (see also Heugh et al., 2017). Nonetheless, emerging work in multilingual testing and translanguaging pedagogy across Africa—such as that of Antia (2024) and others advancing decolonial approaches to evaluation—signals a growing momentum that may soon expand to assessment research.

The relative scarcity of European studies warrants a similarly nuanced interpretation. Rather than indicating an absence of multilingual practice, this gap partly reflects how multilingualism is normalized within European educational systems and conceptualized through plurilingualism in the Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR). While plurilingual competence acknowledges integrated linguistic repertoires, it is often operationalized within policy and proficiency frameworks that differ from heteroglossic theories and translanguaging’s connection to social justice. For example, several European publications—such as De Backer et al. (2019), Saville (2019), and Margić and Molino (2022)—were excluded from our dataset because they focus on test accommodations, policy reforms, or pedagogical practices without empirically theorizing assessment through a translanguaging or heteroglossic lens. These regional trends reveal how epistemic visibility and theoretical framing—rather than the actual presence or absence of multilingual practice—shape the contours of translanguaging assessment scholarship worldwide.

Additionally, although most studies were published in applied linguistics journals, only a few appeared in general education or disciplinary-specific journals. This raises important questions about the audiences this research is—and is not—reaching. If translanguaging assessment is to influence practice and policy broadly, it must move beyond linguistics circles and into education, content-area, and policy-focused spaces where assessment discourse is shaped and operationalized.

5.2. Interrogating Equity: Insights from the Justice Spectrum

While translanguaging assessment is often celebrated for its equity-promoting potential, our review reveals wide variation in how justice is conceptualized and enacted. This “spectrum of justice” framework illustrates how some studies foreground translanguaging’s instructional benefits, while others use it to disrupt entrenched raciolinguistic hierarchies and reimagine assessment as a decolonial, justice-oriented practice. This conceptual diversity reflects the field’s richness but also points to an urgent need for greater ideological clarity. Without explicit attention to power, race, and language politics, translanguaging risks being reduced to a technical fix rather than a transformative stance. Future work must move beyond descriptive accounts and toward critical inquiry that centers multilingual students’ lived experiences and challenges the systems that marginalize them.

5.3. Implications for Primary, Secondary and Higher Education

In primary and secondary settings, the reviewed studies highlight the affordances of translanguaging assessment in affirming multilingual students’ identities, improving teacher feedback, and fostering authentic demonstrations of learning. Classroom translanguaging assessments can help educators identify and respond to students’ strengths in ways that resist deficit-based placement and tracking practices. Yet many teachers remain constrained by institutional mandates, monolingual testing policies, and a lack of multilingual infrastructure—especially in standardized assessment contexts. This suggests the need for systemic professional development, leadership support, and the development of flexible assessment tools that validate translanguaging as both pedagogically sound and politically necessary.

In higher education, translanguaging assessments can serve as powerful tools to reduce linguistic anxiety, support transnational students, and cultivate more inclusive learning environments. However, resistance remains strong in academic gatekeeping practices—especially in contexts where English proficiency is tied to institutional legitimacy and upward mobility. Faculty may support translanguaging pedagogically but feel constrained by accreditation bodies, monolingual rubrics, or institutional norms. As universities reckon with calls for decolonization and equity, translanguaging assessment offers a concrete practice through which to reimagine linguistic justice in postsecondary education.

6. Conclusions and Future Directions

Translanguaging in assessment is not merely an accommodation strategy; it is an epistemological and political stance. As our review demonstrates, its implementation can enhance multilingual students’ learning, transform teacher beliefs, and challenge the exclusionary logic of traditional testing. This review emphasized meaningful innovations that have begun to mitigate the persistent inequities that multilingual learners have faced in taking tests in a variety of contexts for decades. Yet for these affordances to be realized broadly, translanguaging must move beyond isolated classroom practices toward systemic reconfiguration of what counts as legitimate knowledge, language, and learning.

Future research should expand geographically to include more studies from the global South and historically marginalized contexts. Methodologically, while the dominance of qualitative studies reflects the relational and exploratory nature of translanguaging, there is a pressing need for more mixed-methods and longitudinal research. Such work can help generate scalable insights that balance the richness of lived experiences with evidence of broader impact. Importantly, however, the call for more quantitative data should not re-center positivist logics that erase linguistic complexity, but rather be rooted in culturally sustaining, justice-oriented frameworks.

To shift the field meaningfully, translanguaging scholarship must also extend its reach. Publishing in applied linguistics journals is crucial—but not sufficient. We urge scholars to engage with general education, teacher education, policy, and content-area outlets to influence a broader range of stakeholders. Simultaneously, we must ensure that multilingual communities themselves—families, students, and educators—are partners in co-creating the assessment tools and policies that affect them.

As assessment continues to shape educational futures, translanguaging offers a timely and necessary intervention. It reminds us that to “sit beside” students in the spirit of assessment’s Latin root, we must honor all of who they are. By reimagining assessment not as a neutral act of measurement, but as a dialogic, relational, and justice-seeking practice, we can begin to build educational systems that reflect the multilingual realities—and aspirations—of the communities we serve.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/educsci15111567/s1, The current landscape of translanguaging assessment research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.T. and J.L.S.; Methodology, Z.T., J.L.S., C.-H.Y. and J.W.M.; Validation, Z.T. and J.L.S.; Formal Analysis, Z.T., J.L.S., C.-H.Y. and J.W.M.; Investigation, Z.T. and J.L.S.; Resources, Z.T., J.L.S., C.-H.Y. and J.W.M.; Data Curation, Z.T., J.L.S., C.-H.Y. and J.W.M.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, Z.T., J.L.S., C.-H.Y. and J.W.M.; Writing—Review & Editing, Z.T., J.L.S., C.-H.Y. and J.W.M.; Visualization, J.L.S.; Supervision, Z.T.; Project Administration, Z.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Note

| 1 | The large number of studies are excluded from Google Scholar because that search engine included studies where the search terms appeared in all areas of the publications, including references. This resulted in many studies fitting the initial search terms, but not the inclusion criteria. |

References

(* indicates articles included in the systematic review).

- * Adamson, J., & Coulson, D. (2015). Translanguaging in English academic writing preparation. International Journal of Pedagogies and Learning, 10(1), 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alderson, J. C., & Banerjee, J. (2001). Language testing and assessment (part 1). Language Teaching, 34(4), 213–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alderson, J. C., & Wall, D. (1993). Does washback exist? Applied Linguistics, 14(2), 115–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychological Association. (2023). Journal article reporting standards (JARS—Qual). Available online: https://apastyle.apa.org/jars/qualitative (accessed on 15 July 2023).

- Antia, B. E. (2024). Multilingual assessment: The Global South as locus of enunciation. In K. Vogt, & B. E. Antia (Eds.), Multilingual assessment—Finding the nexus? (pp. 27–62) Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Arias, A., & Schissel, J. L. (2021). How are multilingual communities of practice being considered in language assessment? A language ecology approach. Journal of Multilingual Theories and Practices, 2(2), 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- * Ascenzi-Moreno, L., & Seltzer, K. (2021). Always at the bottom: Ideologies in assessment of emergent bilinguals. Journal of Literacy Research, 53(4), 468–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachman, L. F., & Palmer, A. S. (1996). Language testing in practice: Designing and developing. Useful language tests. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bachman, L. F., & Palmer, A. S. (2010). Language assessment in practice. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- * Baker, B., & Hope, A. (2019). Incorporating translanguaging in language assessment: The case of a test for university professors. Language Assessment Quarterly, 16(4–5), 408–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- * Bauer, E. B., Colomer, S. E., & Wiemelt, J. (2020). Biliteracy of African American and Latinx kindergarten students in a dual-language program: Understanding students’ translanguaging practices across informal assessments. Urban Education, 55(3), 331–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- * Burgess, J., & Roswell, J. (2020). Transcultural-affective flows and multimodal engagements: Reimagining pedagogy and assessment with adult language learners. Language and Education, 34(2), 173–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- * Buxton, C., Harman, R., Cardozo-Gaibisso, L., & Dominguez, M. V. (2022). Translanguaging within an integrated framework for multilingual science meaning making. In A. Jakobsson, P. Nygård Larsson, & A. Karlsson (Eds.), Translanguaging in science education (Vol. 27, pp. 13–38). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, J. L., Quincy, C., Osserman, J., & Pedersen, O. K. (2013). Coding in-depth semistructured interviews: Problems of unitization and intercoder reliability and agreement. Sociological Methods & Research, 42(3), 294–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalhoub-Deville, M. B. (2019). Multilingual testing constructs: Theoretical foundations. Language Assessment Quarterly, 16(4–5), 472–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Backer, F., Baele, J., van Avermaet, P., & Slembrouck, S. (2019). Pupils’ perceptions on accommodations in multilingual assessment of science. Language Assessment Quarterly, 16(4–5), 426–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fereday, J., & Muir-Cochrane, E. (2006). Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5(1), 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- * Fine, C. G. M. (2022). Translanguaging interpretive power in formative assessment co-design: A catalyst for science teacher agentive shifts. Journal of Language, Identity & Education, 21(3), 191–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, N. (2009). Scales of justice: Reimagining political space in a globalizing world. Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- * Gandara, F., & Randall, J. (2019). Assessing mathematics proficiency of multilingual students: The case for translanguaging in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Comparative Education Review, 63(1), 58–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, O., Johnson, S. I., & Seltzer, K. (2017). The translanguaging classroom: Leveraging student bilingualism for learning. Caslon. [Google Scholar]

- García, O., & Kleyn, T. (Eds.). (2016). Translanguaging with multilingual students: Learning from classroom moments. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- García, O., & Leiva, C. (2014). Theorizing and enacting translanguaging for social justice. In A. Creese, & A. Blackledge (Eds.), Heteroglossia as practice and pedagogy (pp. 199–216). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- García, O., & Li, W. (2014). Translanguaging: Language, bilingualism and education. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- * García, O., Woodley, H. H., Flores, N., & Chu, H. (2012). Latino emergent bilingual youth in high schools: Transcaring strategies for academic success. Urban Education, 48(6), 798–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorter, D., & Cenoz, J. (2017). Language education policy and multilingual assessment. Language and Education, 31(3), 231–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- * Greenier, V., Liu, X., & Xiao, Y. (2023). Creative translanguaging in formative assessment: Chinese teachers’ perceptions and practices in the primary EFL classroom. Applied Linguistics Review, 15(5), 1861–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- * Guzman-Orth, D. A., Lopez, A. A., & Tolentino, F. (2019). Exploring the use of a dual language assessment task to assess young English learners. Language Assessment Quarterly, 16(4–5), 447–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamman-Ortiz, L., Dougherty, C., Tian, Z., Palmer, D., & Poza, L. (2025). Translanguaging at school: A systematic review of US PK-12 translanguaging research. System, 129, 103594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- * Heugh, K., Prinsloo, C., Makgamatha, M., Diedericks, G., & Winnaar, L. (2017). Multilingualism (s) and system-wide assessment: A southern perspective. Language and Education, 31(3), 197–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, A. (1989). Testing for language teachers. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- * Kabuto, B. (2017). A socio-psycholinguistic perspective on biliteracy: The use of miscue analysis as a culturally relevant assessment tool. Reading Horizons: A Journal of Literacy and Language Arts, 56(1), 25–44. Available online: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/reading_horizons/vol56/iss1/2 (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Li, W., & García, O. (2022). Not a first language but one repertoire: Translanguaging as a decolonizing project. RELC Journal, 53(2), 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- * Lopez, A. A. (2023a). Examining how Spanish-speaking English language learners use their linguistic resources and language modes in a dual language mathematics assessment task. Journal of Latinos and Education, 22(1), 198–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- * Lopez, A. A. (2023b). Enabling multilingual practices in English language proficiency assessments for young learners. In K. Raza, D. Reynolds, & C. Coombe (Eds.), Handbook of multilingual TESOL in practice (pp. 359–371). Springer Nature Singapore. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- * Lopez, A. A., Guzman-Orth, D., & Turkan, S. (2014). A study on the use of translanguaging to assess the content knowledge of emergent bilingual students [Unpublished manuscript]. Educational Testing Service, USA.

- * Lopez, A. A., Guzman-Orth, D., & Turkan, S. (2019). Exploring the use of translanguaging to measure the mathematics knowledge of emergent bilingual students. Translation and Translanguaging in Multilingual Contexts, 5(2), 143–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- * Lopez, A. A., Luce, C., Zapata-Rivera, D., & Forsyth, C. (2017). Using formative conversation-based assessments to support students’ English language development. Bulletin of the Technical Committee on Learning Technology, 19(1), 6–9. [Google Scholar]

- * López-Velásquez, A. M., & García, G. E. (2017). The bilingual reading practices and performance of two Hispanic first graders. Bilingual Research Journal, 40(3), 246–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- * Macawile, K. L., & Plata, S. (2022). Translanguaging as a resource for teaching and assessment: Perceptions of senior high school teachers. Modern Journal of Studies in English Language Teaching and Literature, 4(2), 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Makoni, S., & Pennycook, A. (2007). Disinventing and reconstituting languages. Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Margić, B. D., & Molino, A. (2022). Translanguaging in EMI: Lecturers’ perspectives and practices. RiCOGNIZIONI. Rivista Di Lingue E Letterature Straniere E Culture Moderne, 9(17), 29–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, M. L. (2012). Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic. Biochemia Medica, 22(3), 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- * Morales, J., Schissel, J. L., & López-Gopar, M. (2020). Pedagogical sismo: Translanguaging approaches for English language instruction and assessment in Oaxaca, Mexico. In Z. Tian, L. Aghai, P. Sayer, & J. L. Schissel (Eds.), Envisioning TESOL through a translanguaging lens: Global perspectives (pp. 161–183). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, M., & Gough, D. (2020). Systematic reviews in educational research: Methodology, perspectives and application. In O. Zawacki-Richter, M. Kerres, S. Bedenlier, M. Bond, & K. Buntins (Eds.), Systematic reviews in educational research (pp. 3–22). Springer VS. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- * Noguerón-Liu, S., & Driscoll, K. (2021). Bilingual families’ perspectives on literacy resources and supports at home. The Reading Teacher, 75(1), 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- * Noguerón-Liu, S., Shimek, C. H., & Bahlmann Bollinger, C. (2020). ‘Dime De Que Se Trató/Tell me what it was about’: Exploring emergent bilinguals’ linguistic resources in reading assessments with parent participation. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 20(2), 411–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, C., & Joffe, H. (2020). Intercoder reliability in qualitative research: Debates and practical guidelines. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- * Przymus, S. D., & Alvarado, M. (2019). Advancing bilingual special education: Translanguaging in content-based story retells for distinguishing language difference from disability. Multiple Voices for Ethnically Diverse Exceptional Learners, 19(1), 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- * Qureshi, M. A., & Aljanadbah, A. (2022). Translanguaging and reading comprehension in a second language. International Multilingual Research Journal, 16(4), 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- * Rafi, A. S. M. (2023). Creativity, criticality and translanguaging in assessment design: Perspectives from Bangladeshi higher education. Applied Linguistics Review, 15(5), 1887–1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawlsian, J. (2001). Justice as fairness: A restatement. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rosa, J. (2019). Looking like a language, sounding like a race: Raciolinguistic ideologies and the learning of Latinidad. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Saville, N. (2019). How can multilingualism be supported through language education in Europe? Language Assessment Quarterly, 16(4–5), 464–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, G. I. (1934). Bilingualism and mental measures. A word of caution. Journal of Applied Psychology, 18(6), 765–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schissel, J. L. (2019). Social consequences of testing for language-minoritized bilinguals in the United States (Vol. 117). Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Schissel, J. L. (2025). Humanizing assessment: Decolonizing, historicizing, and communing with language-minoritized communities. Critical Inquiry in Language Studies, 22(2), 128–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- * Schissel, J. L., De Korne, H., & López-Gopar, M. (2021). Grappling with translanguaging for teaching and assessment in culturally and linguistically diverse contexts: Teacher perspectives from Oaxaca, Mexico. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 24(3), 340–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schissel, J. L., Leung, C., & Chalhoub-Deville, M. (2019). The construct of multilingualism in language testing. Language Assessment Quarterly, 16(4–5), 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- * Schissel, J. L., Leung, C., López-Gopar, M., & Davis, J. R. (2018). Multilingual learners in language assessment: Assessment design for linguistically diverse communities. Language and Education, 32(2), 167–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seltzer, K., & Schissel, J. L. (2025). A critical translanguaging lens on assessment. In L. Wei, P. Phyak, J. W. Lee, & O. García (Eds.), The handbook of translanguaging (pp. 349–364). Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- * Shi, L., & Rolstad, K. (2022). “I don’t let what I don’t know stop what I can do”—How monolingual English teachers constructed a translanguaging Pre-K classroom in China. TESOL Quarterly, 57(4), 1490–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shohamy, E. (2011). Assessing multilingual competencies: Adopting construct valid assessment policies. The Modern Language Journal, 95(3), 418–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- * Shohamy, E., Tannenbaum, M., & Gani, A. (2022). Bi/multilingual testing for bi/multilingual students: Policy, equality, justice, and future challenges. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 25(9), 3448–3462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- * Tian, Z. (2022a). Translanguaging Design in a third grade Chinese language arts class. Applied Linguistics Review, 13(3), 327–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- * Tian, Z. (2022b). Challenging the “dual”: Designing translanguaging spaces in a Mandarin-English dual language bilingual education program. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 43(6), 534–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Viegen, S., Lau, S. M. C., & Lin, A. M. Y. (in press). Multilingual assessment for social justice in diverse educational contexts. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism.

- * Wang, D., & East, M. (2023). Integrating translanguaging into assessment: Students’ responses and perceptions. Applied Linguistics Review, 15(5), 1911–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y., & Qiu, Y. (2024). Epistemic (in)justice in English-medium instruction: Transnational teachers’ and students’ negotiation of knowledge participation through translanguaging. Language and Education, 38(1), 97–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).