Evidence Without Hype, Gamified Quizzing in EFL and ESL Classrooms in Low-Input Contexts, a Critical Review and Minimum Reporting Standards

Abstract

1. Introduction

Research Questions

- RQ1. To what extent does digital gamification improve assessed EFL/ESL performance in course-integrated tasks such as vocabulary, reading, grammar, or combined skills?

- RQ2. How does gamification shape participation, attention, and on-task behaviour during lessons?

- RQ3. How do students perceive gamified activities in terms of motivation, enjoyment, usefulness, fairness, and anxiety?

- RQ4. How do teachers evaluate gamification with respect to feasibility, workload, assessment alignment, and classroom management?

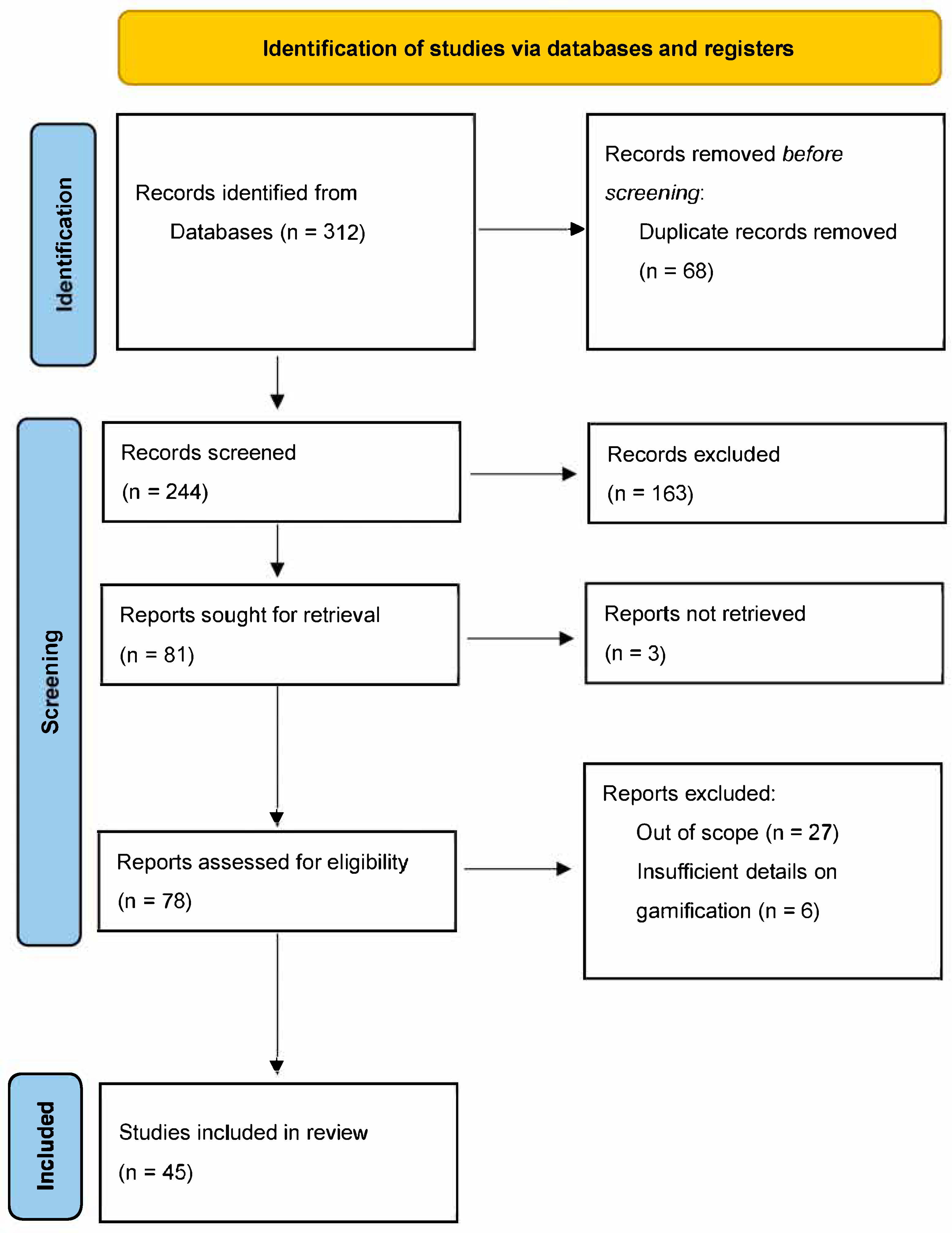

2. Methods and Approaches

- examined digital gamification in English language learning contexts,

- involved classroom or course-integrated activities rather than standalone entertainment,

- reported empirical outcomes on learning, engagement, or affect, and

- were peer-reviewed journal articles in English.

3. Results

3.1. RQ1: Learning Performance

3.2. RQ2: Classroom Dynamics

3.3. RQ3: Students’ Perceptions

3.4. RQ4: How Teachers Orchestrate Gamified EFL/ESL Work (Planning, Pacing, Feedback, Grouping) and Handle Constraints, Integrity, Equity, and Privacy

4. Discussion of the Results

5. Limitations of the Study

6. Recommendations for Practice and Future Research

7. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EFL, ESL | English as a Foreign Language, English as a Second Language |

| FL | Foreign Language |

| L1, L2 | First Language, Second Language |

| RQ | Research Question |

| HE | Higher Education |

| K-12 | Primary and secondary schooling |

| AR, VR | Augmented Reality, Virtual Reality |

| RPG | Role-Playing Game |

| LMS | Learning Management System |

| UX | User Experience |

| PD | Professional Development |

| Wi-Fi | Wireless internet connectivity |

| App | Application (mobile or web) |

| RCT | Randomised Controlled Trial |

| ANCOVA | Analysis of Covariance |

| M, SD | Mean, Standard Deviation |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| NS | Non-significant |

| WMC | Working Memory Capacity |

References

- Aldubayyan, N., & Aljebreen, S. (2025). The impact of Kahoot!-assisted gamification on Saudi EFL learners’ phrasal verb mastery and classroom engagement. Forum for Linguistic Studies, 7(9), 584–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfares, N. S. (2025). Investigating the efficacy of wordwall platform in enhancing vocabulary learning in Saudi EFL classroom. International Journal of Game-Based Learning, 15(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hoorie, A. H., & Albijadi, O. (2025). The motivation of uncertainty: Gamifying vocabulary learning. RELC Journal, 56(2), 332–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almufareh, M. (2021). The impact of gamification and individual differences on second language learning among first-year female university students in Saudi Arabia. Simulation & Gaming, 52(6), 715–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsswey, A., & Malak, M. Z. (2024). Effect of using gamification of “Kahoot!” as a learning method on stress symptoms, anxiety symptoms, self-efficacy, and academic achievement among university students. Learning and Motivation, 87, 101993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anane, C. (2024). Impact of a game-based tool on student engagement in a foreign language course: A three-term analysis. Frontiers in Education, 9, 1430729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolat, Y. I., & Taş, N. (2023). A meta-analysis on the effect of gamified-assessment tools’ on academic achievement in formal educational settings. Education and Information Technologies, 28(5), 5011–5039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancino Avila, M. O., & Castillo Fonseca, G. I. (2021). Gamification: How does it impact L2 vocabulary learning and engagement? Electronic Journal of Foreign Language Teaching, 18(2), 156–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S., & Lo, N. (2024). Enhancing EFL/ESL instruction through gamification: A comprehensive review of empirical evidence. Frontiers in Education, 9, 1395155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-M., Liu, H., & Huang, H.-B. (2019). Effects of a mobile game-based English vocabulary learning app on learners’ perceptions and learning performance: A case study of Taiwanese EFL learners. ReCALL, 31(2), 170–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J., Lu, C., & Xiao, Q. (2025). Effects of gamification on EFL learning: A quasi-experimental study of reading proficiency and language enjoyment among Chinese undergraduates. Frontiers in Psychology, 16, 1448916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiang, H.-H. (2020). Kahoot! In an EFL reading class. Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 11(1), 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cigdem, H., Ozturk, M., Karabacak, Y., Atik, N., Gürkan, S., & Aldemir, M. H. (2024). Unlocking student engagement and achievement: The impact of leaderboard gamification in online formative assessment for engineering education. Education and Information Technologies, 29(18), 24835–24860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deterding, S., Dixon, D., Khaled, R., & Nacke, L. (2011, September 28–30). From game design elements to gamefulness: Defining “gamification”. 15th International Academic MindTrek Conference: Envisioning Future Media Environments (pp. 9–15), Tampere, Finland. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dindar, M., Ren, L., & Järvenoja, H. (2021). An experimental study on the effects of gamified cooperation and competition on English vocabulary learning. British Journal of Educational Technology, 52(1), 142–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahada, N., & Asrul, N. (2024). Students perception of gamified learning in EFL class: Online Quizizz for engagement and motivation. Journal of Education and Teaching Learning (JETL), 6(2), 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franciosi, S. J., Yagi, J., Tomoshige, Y., & Ye, S. (2016). The effect of a simple simulation game on long-term vocabulary retention. CALICO Journal, 33(3), 355–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F. (2024). Advancing gamification research and practice with three underexplored ideas in self-determination theory. TechTrends, 68(4), 661–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gini, F., Bassanelli, S., Bonetti, F., Mogavi, R. H., Bucchiarione, A., & Marconi, A. (2025). The role and scope of gamification in education: A scientometric literature review. Acta Psychologica, 259, 105418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, J. (2020). Gamifying the flipped classroom: How to motivate Chinese ESL learners? Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 14(5), 421–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.-C., Hwang, M.-Y., Liu, Y.-H., & Tai, K.-H. (2022). Effects of gamifying questions on English grammar learning mediated by epistemic curiosity and language anxiety. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 35(7), 1458–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, W., Pack, A., Guan, Y., Zhang, L., & Zou, B. (2025). The influence of game-based learning media on academic English vocabulary learning in the EFL context. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 38(5–6), 1341–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, M. N., & Nasouri, A. (2024). EFL learners’ flow experience and incidental vocabulary learning during text-based game tasks: The moderating role of working memory capacity. System, 124, 103398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krath, J., Schürmann, L., & von Korflesch, H. F. O. (2021). Revealing the theoretical basis of gamification: A systematic review and analysis of theory in research on gamification, serious games and game-based learning. Computers in Human Behavior, 125, 106963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniawan, A. B., Unsiah, F., & Razali, K. A. (2024). Students’ perception on utilizing Kahoot! As a game-based student response system for EFL students. Journal of Languages and Language Teaching, 12(2), 1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lashari, S. A., Rahman, S. U., & Lashari, T. A. (2025). Using Kahoot as a gamified learning approach to enhance classroom engagement and reduce test anxiety. RMLE Online, 48(8), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M., Ma, S., & Shi, Y. (2023). Examining the effectiveness of gamification as a tool promoting teaching and learning in educational settings: A meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1253549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z. (2024). More haste, less speed? Relationship between response time and response accuracy in gamified online quizzes in an undergraduate engineering course. Frontiers in Education, 9, 1412954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G., Fathi, J., & Rahimi, M. (2024). Using digital gamification to improve language achievement, foreign language enjoyment, and ideal L2 self: A case of English as a foreign language learners. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 40(4), 1347–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z. (2023). The effectiveness of gamified tools for foreign language learning (FLL): A systematic review. Behavioral Sciences, 13(4), 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mat Husin, M. Z., & Azmuddin, R. A. (2022). Learner engagement in using Kahoot! Within a university English proficiency course. Educational Process International Journal, 11(2), 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naderi, S., & Moafian, F. (2023). The victory of a non-digital game over a digital one in vocabulary learning. Computers and Education Open, 4, 100135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panmei, B., & Waluyo, B. (2022). The pedagogical use of gamification in English vocabulary training and learning in higher education. Education Sciences, 13(1), 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paramita, P. E. (2023). Exploring student perceptions and experiences of Nearpod: A qualitative study. Journal on Education, 5(4), 17560–17570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, I., Shanmugam, N., Ismail, S. M., & Mandal, G. (2022). An investigation of EFL learners’ vocabulary retention and recall in a technology-based instructional environment: Focusing on digital games. Education Research International, 2022, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, A. T. (2023). The impact of gamified learning using Quizizz on ESL learners’ grammar achievement. Contemporary Educational Technology, 15(2), ep410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, A. T., Thai, C. T. H., & Van Nguyen, T. (2025). Gamified learning in grammar lessons: EFL students’ perceptions of Kahoot! and Quizizz. Acta Psychologica, 259, 105436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, C. N. T., & Tran, A. N. P. (2024, April 27–30). Students’ achievements and teachers’ perception: Exploring the effectiveness of Kahoot for vocabulary learning in Vietnamese classrooms. ICRES 2024—International Conference on Research in Education and Science, Antalya, Turkey. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED673139 (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Rojabi, A. R., Setiawan, S., Munir, A., Purwati, O., Safriyani, R., Hayuningtyas, N., Khodijah, S., & Amumpuni, R. S. (2022). Kahoot, is it fun or unfun? Gamifying vocabulary learning to boost exam scores, engagement, and motivation. Frontiers in Education, 7, 939884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, K., Sağlık, E., Mede, E., Samur, Y., & Comert, Z. (2022). The effects of implementing gamified instruction on vocabulary gain and motivation among language learners. Heliyon, 8(11), e11811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sailer, M., & Homner, L. (2020). The Gamification of Learning: A Meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 32(1), 77–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temel, T., & Cesur, K. (2024). The effect of gamification with Web 2.0 tools on EFL learners’ motivation and academic achievement in online learning environments. Sage Open, 14(2), 21582440241247928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waluyo, B., & Balazon, F. G. (2024). Exploring the impact of gamified learning on positive psychology in CALL environments: A mixed-methods study with Thai university students. Acta Psychologica, 251, 104638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A. I., & Tahir, R. (2020). The effect of using Kahoot! For learning—A literature review. Computers & Education, 149, 103818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werbach, K., & Hunter, D. (2015). The gamification toolkit: Dynamics, mechanics, and components for the win. University of Pennsylvania Press, Incorporated. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J. (2024). Study on computer-based systematic foreign language vocabulary teaching. The JALT CALL Journal, 20(3), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainuddin, Z., Chu, S. K. W., Shujahat, M., & Perera, C. J. (2020). The impact of gamification on learning and instruction: A systematic review of empirical evidence. Educational Research Review, 30, 100326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakian, M., Xodabande, I., Valizadeh, M., & Yousefvand, M. (2022). Out-of-the-classroom learning of English vocabulary by EFL learners: Investigating the effectiveness of mobile assisted learning with digital flashcards. Asian-Pacific Journal of Second and Foreign Language Education, 7(1), 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R., Zou, D., & Cheng, G. (2023). Learner engagement in digital game-based vocabulary learning and its effects on EFL vocabulary development. System, 119, 103173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S., & Hasim, Z. (2023). Gamification in EFL/ESL instruction: A systematic review of empirical research. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1030790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Skill/Focus | Design and N | Post-Test Timing | Main Performance Outcome | Social/Competition Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sailer and Homner (2020) | Cross-domain learning (cognitive/motivational/behavioural) | Meta-analysis (k = 38; 40 exps) | Mostly immediate; rare delayed | Small positive effects overall; cognitive most robust | Competitive–collaborative > pure competition for behavioural; fiction helps behaviour |

| Wang and Tahir (2020) | Quiz-based learning (multi-discipline; incl. EFL) | Narrative review (93 studies) | Mostly immediate | Predominantly positive; wear-out and time-pressure issues | Individual competition common; team play can reduce anxiety |

| Li et al. (2023) | Education-wide learning outcomes | Meta-analysis | Unclear delayed reporting | Positive overall; stronger with longer duration and fuller designs | Social dynamics important; specifics not coded |

| S. Zhang and Hasim (2023) | EFL/ESL performance and affect | Systematic review (40 studies) | Mixed; limited delayed | Frequent gains; also nulls where design/tech frictions occur | Competition may unsettle some learners |

| Luo (2023) | FL gamified tools effectiveness | Systematic review (21 studies) | Mixed; some longitudinal | Mixed effectiveness; gaps in cognitive engagement measures | Heterogeneous element mixes; risk of “pointsification” |

| Cheng et al. (2025) | Reading proficiency (HE) | Quasi-exp., 16 weeks, N = 220 | Immediate only | Gamified > traditional on reading; enjoyment up | Competitive + collaborative class games; points/badges/leaderboards |

| Panmei and Waluyo (2022) | Vocabulary (HE) | Quasi-exp., 4 weeks, N = 100 | Weekly immediate | No overall gain vs. paper; some weekly wins | Quizizz features incl. timers/leaderboards; individual play |

| Liu et al. (2024) | Mixed skills; enjoyment; ideal L2 self (young EFL) | Mixed-methods RCT, N = 36 | Immediate only | Digital gamified > non-digital gamified on all outcomes | Points, badges, leaderboards; some collaboration |

| Chen et al. (2019) | Vocabulary (HE) | App RCT-style, N = 20 | Immediate + 2-week delay | Gamified app > non-gamified app at both times | Individual + leaderboard; mini-games; competition elements |

| Franciosi et al. (2016) | Vocabulary (HE) | Quasi-exp., N ≈ 162 | 1-week + 11-week delay | No immediate gain; delayed advantage for simulation | Collaborative team play in simulation; control individual flashcards |

| Jia et al. (2025) | Academic vocabulary (HE) | Quasi-exp., N = 90 | Immediate + 1- and 3-week delay | AR > digital app immediately; parity with paper; attenuates over time | Individual play; no explicit leaderboards/timers |

| Naderi and Moafian (2023) | Vocabulary (primary) | Quasi-exp. crossover, N = 40 | Immediate + 2-week delay | Non-digital collaborative > digital individual at both times | Digital individual/competitive vs. non-digital cooperative |

| Wu (2024) | Vocabulary (HE) | Quasi-exp., 10 weeks, N = 58 | Immediate + 1-month delay | Computer-based > paper at both times | Individual, strategy-rich computer tasks; no competition |

| Patra et al. (2022) | Vocabulary (primary) | Quasi-exp., 9 sessions, N = 50 | Immediate + 3-week delay | Digital cooperative > traditional | Cooperative play; no explicit competitive mechanics |

| Zakian et al. (2022) | Vocabulary (HE; out-of-class) | Quasi-exp., 4 months, N = 86 | Immediate + 2-month delay | Digital flashcards > paper; some decline at delay | Individual, spaced repetition; no competition |

| Karimi and Nasouri (2024) | Incidental vocabulary (HE) | Quasi-exp., N = 57 | Immediate + 2-week delay | Digital text-based game ≈ paper text-based game; flow and WMC matter | Individual; narrative choices; no competition |

| Temel and Cesur (2024) | Motivation and achievement (HE, online) | Quasi-exp., N = 60 | Immediate only | Motivation ↑; achievement NS vs. control | Mostly individual competition via leaderboards |

| Cluster | Studies | Mode | Typical Mechanics | How Dynamics Were Measured | Key Takeaway |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meta/reviews | (Sailer & Homner, 2020; Wang & Tahir, 2020) | Mixed | Timers, points, leaderboards; comp/collab/comp-collab; fiction | Syntheses and moderator analyses | Livelier sessions; competitive–collab > competition on behavioural indicators; fiction supports on-task effort; manage time pressure. |

| In-person HE | (Aldubayyan & Aljebreen, 2025; Chiang, 2020; Sadeghi et al., 2022; Waluyo & Balazon, 2024) | Face-to-face | 20–60 s timers, points, team play, leaderboards, rewards | Surveys, tests, interviews; item feedback | Structured turn-taking and energy ↑; some stress with speed/competition; teamwork steadies participation. |

| Online HE | (Anane, 2024; Dindar et al., 2021; Fahada & Asrul, 2024; Mat Husin & Azmuddin, 2022) | Fully online | Kahoot/Quizizz; daily app tasks (points/badges/leaderboards); coop vs. comp | Surveys; app logs; group messages | Energy ↑; cooperation → stronger relatedness and richer messaging; connectivity/usability can disrupt flow. |

| Blended/logs | (Cigdem et al., 2024; Zainuddin et al., 2020) | Blended/in-person | Weekly leaderboards/timed e-quizzes; badges; team races | LMS logs; surveys/interviews; performance | Completion ↑ and more homogeneous attempts ; later quizzes ↑; anonymity broadens shy students’ voices; some novelty tapers. |

| Edge cases | (Alfares, 2025; Al-Hoorie & Albijadi, 2025) | Out-of-class/K-12 | RPG app (avatars, time limits); Wordwall | App logs and tests; no interaction coding | Vocabulary gains but little in in-class interaction; out-of-class gains may fade by delayed tests. |

| Course-wide rotation | (Temel & Cesur, 2024) | Online | Rotating Web-2.0 quizzes | ANCOVA on motivation; achievement test | Motivation/climate ↑ even when achievement NS; pacing/variety matter. |

| Study | Affective (Enjoyment, Motivation, Anxiety) | Perceived Learning (Understanding, Feedback, Pace) | Practicality and Fairness (Usability, Access, Timing, Leaderboard) | Evidence Type/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rojabi et al. (2022) | “Fun,” “exciting,” not boring; high engagement (M = 3.95) and motivation (M = 4.09). | Immediate feedback valued; felt pushed to learn topics correctly. | Time limits frustrating; unstable internet; room-size caps; some items difficult. | Student quotes + Likert means. |

| Phan and Tran (2024) | Teachers report students enjoy Kahoot; motivation up; boredom down. | Immediate scoring aids tracking; students understand with less lecture. | Unstable internet; inappropriate nicknames; time limits during the lesson. | Teacher surveys; no student scales. |

| Kurniawan et al. (2024) | “Fun, creative, interesting”; enthusiasm up; some distraction from peers/apps. | Easier to understand with audiovisuals + teacher elaboration; feedback helps. | Device gaps; internet issues; classroom management in large classes. | Student quotes/themes; no scale means. |

| Pham (2023) | Not directly reported. | Improved grammar outcomes; reattempts + immediate feedback support review. | Easy access (multi-device); teacher can customise feedback; no fairness issues reported. | Achievement + platform description; no student affect data. |

| Pham et al. (2025) | Enjoyment/motivation high; anxiety mostly mild/declining (Kahoot M = 3.30; Quizizz M = 3.45); excitement about competition. | Quizizz reattempts aid retention; on-device items reduce split attention vs. Kahoot. | Prefer Quizizz for solo/self-study; Kahoot for in-class teams; strict timers stressful; occasional key errors. | Interviews + Likert anxiety means. |

| Paramita (2023) | Described as fun, engaging; positive atmosphere. | Visuals/VR/simulations improve grasp of abstract ideas; real-time checks help. | Technical glitches disrupt flow; desire for more customization. | Student themes; no quotes/means. |

| Almufareh (2021) | Duolingo seen as fun; motivation; competitive elements can engage. | Audiovisual repetition + self-pacing help reading/writing/vocab. | App not in syllabus → extra workload; features (XP) seen as less useful. | Surveys/interviews (students and profs). |

| Chan and Lo (2024) | Generally positive attitudes; competitive cues vary by personality (e.g., introverts vs. extroverts). | Immediate feedback, clear rules, social interaction perceived to help; gains not always sustained. | Usability/infra gaps; some pacing too fast; mixed views on leaderboards. | Narrative review/synthesis. |

| Ho (2020) | High enjoyment (e.g., 92% interest; M ≈ 4.4); reduced reticence to speak. | Better understanding/application of narrative concepts; critical thinking ↑. | Tool easy to use; small-group teamwork preferred; timed scoring accepted. | Mixed-methods; Likert + interviews. |

| Hong et al. (2022) | Curiosity (especially deprivation-type) → more positive gamification attitudes; anxiety lowers curiosity. | Learning performance improved in “pose–gamify–play” grammar tasks. | User-friendly creation/play; fixed short sessions; rankings recorded (no fairness feedback). | Questionnaires + performance data. |

| Bolat and Taş (2023) | Motivation cited as mechanism (meta-analytic context). | Feedback/formative features linked to achievement effects (tool-level). | Notes tool affordances (e.g., avatars/memes in Quizizz); no user fairness data. | Meta-analysis; no primary perceptions. |

| Orchestration Theme | Concrete Practices (What to Do) | Typical Constraints | Integrity and Equity Notes | Privacy/Data Notes | Key Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plan the cadence | Prime → teach → quiz/reteach within the same lesson; reserve a fixed game window (≈15–30 min) to avoid overuse | Prep time for good items; fitting games into tight syllabi | Keep games formative; align with what you assess | Be transparent about what platforms log | (Chan & Lo, 2024; Lashari et al., 2025; Waluyo & Balazon, 2024) |

| Pace the session | Use short rounds/turns; tune timers (not just default); vary mechanics across weeks | Rapid gameplay can outpace some learners | Vet difficulty; avoid speed-only scoring | — | (Cancino Avila & Castillo Fonseca, 2021; Chan & Lo, 2024; Chiang, 2020) |

| Feedback loops | Exploit instant item stats to reteach immediately; let students review wrong answers on their own devices between rounds | Time to debrief within class block | Publicly posted leaderboards can demotivate some | Limit unnecessary exposure of names/scores | (Chan & Lo, 2024; Pham et al., 2025; Waluyo & Balazon, 2024) |

| Grouping and tone | Mix cooperation + light competition (teams/triads + gentle ranking) to broaden participation | Managing teams in large rooms | Rotate roles; set norms to reduce shout-outs | — | (Cancino Avila & Castillo Fonseca, 2021; Lashari et al., 2025; Sailer & Homner, 2020) |

| Tool–room fit | Prefer own-device view to cut split attention; keep a low-tech backup (cards/images) | Single-projector rooms; seating/readability | Ensure everyone can see/participate | — | (Cancino Avila & Castillo Fonseca, 2021; Chiang, 2020; Pham et al., 2025) |

| Low-tech options | Image-rich card games in small groups with scoring/turn rules for immediate, intrinsic feedback | Nonelectronic prep time; printing | Accessible in low-resource contexts | Minimal data footprint | (Cancino Avila & Castillo Fonseca, 2021) |

| Time and workload | Block-design lessons (e.g., lecture 30′ + game 15′); reuse/iterate item banks; plan micro-reteaches | Authoring, vetting items; teacher training needs | Keep stakes low to reduce anxiety | — | (Alsswey & Malak, 2024; Chiang, 2020; Pham, 2023) |

| Tech and class size | Check Wi-Fi; have spare devices/charging; adjust font/music; rehearse join steps | Connectivity, device gaps, app hiccups; big classes | Provide alternatives for students without devices | — | (Alsswey & Malak, 2024; Chiang, 2020; Waluyo & Balazon, 2024) |

| Integrity and quality | Monitor in-room participation; discourage calling out answers; audit public quiz items for errors | Errors in shared item banks; off-site answering | Favour formative use; align items to outcomes | — | (Chiang, 2020; Pham et al., 2025; Sailer & Homner, 2020) |

| Equity and access | Provide own-device modes, low-tech backups, and clear visuals; localise content | Cultural/economic access differences | Scaffold for novice tech users; avoid one-size-fits-all | — | (Alsswey & Malak, 2024; Cancino Avila & Castillo Fonseca, 2021; Chan & Lo, 2024) |

| Dashboards and teacher UX | Use platform analytics that surface actionable patterns without extra load; seek PD on linking mechanics to pedagogy | Data overload; limited PD time | Use data to support, not label students | Handle student data minimally/securely | (Chan & Lo, 2024; Gini et al., 2025) |

| Evidence gaps (for future work) | More reports on teacher moves (think time, role rotation), long-term routines, and policy (privacy) | — | — | Prioritise privacy-by-design in studies | (Gini et al., 2025; R. Zhang et al., 2023) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ameen, F. Evidence Without Hype, Gamified Quizzing in EFL and ESL Classrooms in Low-Input Contexts, a Critical Review and Minimum Reporting Standards. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1568. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121568

Ameen F. Evidence Without Hype, Gamified Quizzing in EFL and ESL Classrooms in Low-Input Contexts, a Critical Review and Minimum Reporting Standards. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1568. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121568

Chicago/Turabian StyleAmeen, Fahad. 2025. "Evidence Without Hype, Gamified Quizzing in EFL and ESL Classrooms in Low-Input Contexts, a Critical Review and Minimum Reporting Standards" Education Sciences 15, no. 12: 1568. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121568

APA StyleAmeen, F. (2025). Evidence Without Hype, Gamified Quizzing in EFL and ESL Classrooms in Low-Input Contexts, a Critical Review and Minimum Reporting Standards. Education Sciences, 15(12), 1568. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121568