Navigating Social Inclusion: How Social and Cognitive Factors Relate to Friendship Quality in Children with ADHD, Dyslexia, and Neurotypical Development

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Friendships, Social Understanding, and Executive Functions (EFs) in Children with and Without Neurodevelopmental Disorders

1.2. The Interplay Among Friendships and Social Understanding, EFs and ER in NT and ND Children

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Demographics Information

2.2.2. Friendship Quality

2.2.3. Social Understanding Tasks

2.2.4. Executive Functions Tasks

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analyses

3.2. Measurement Models

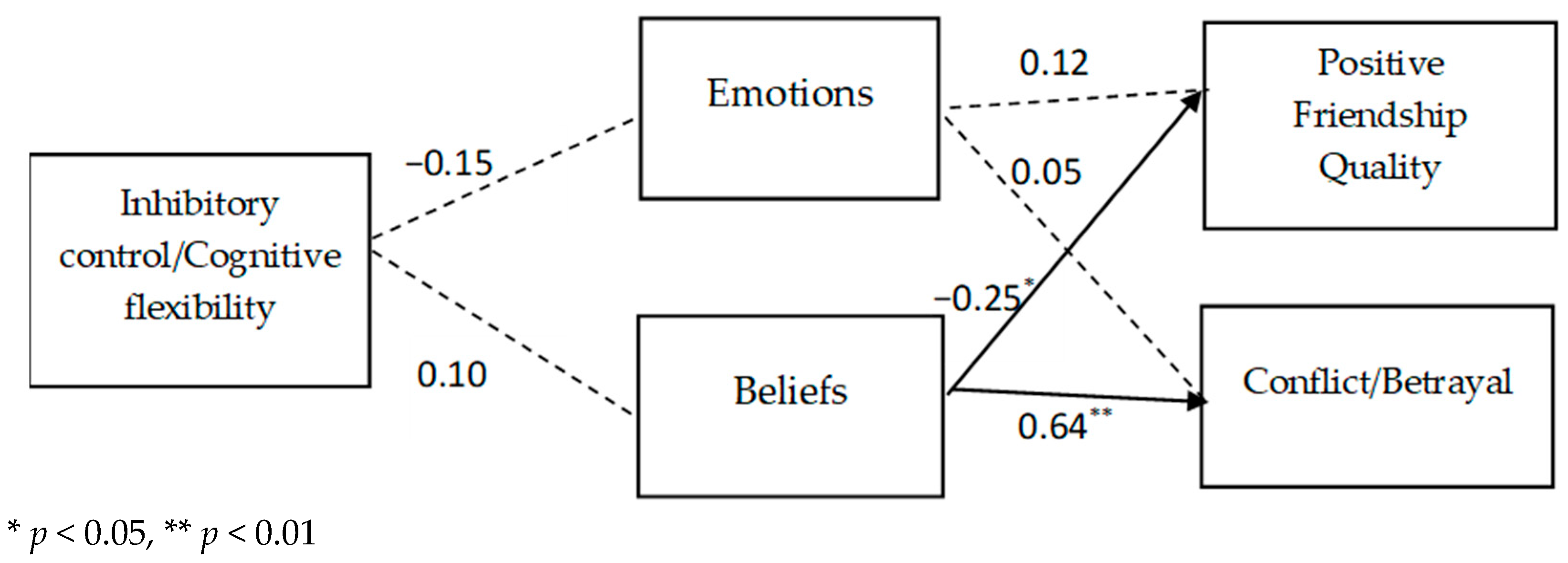

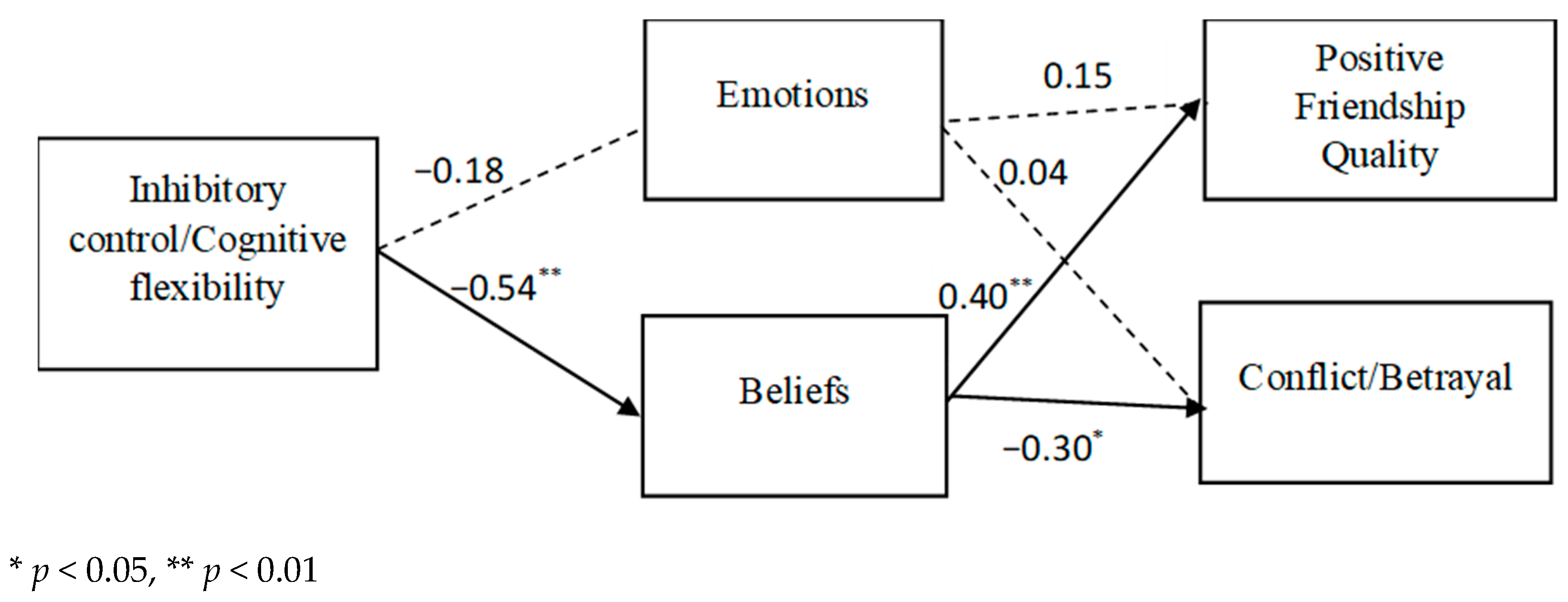

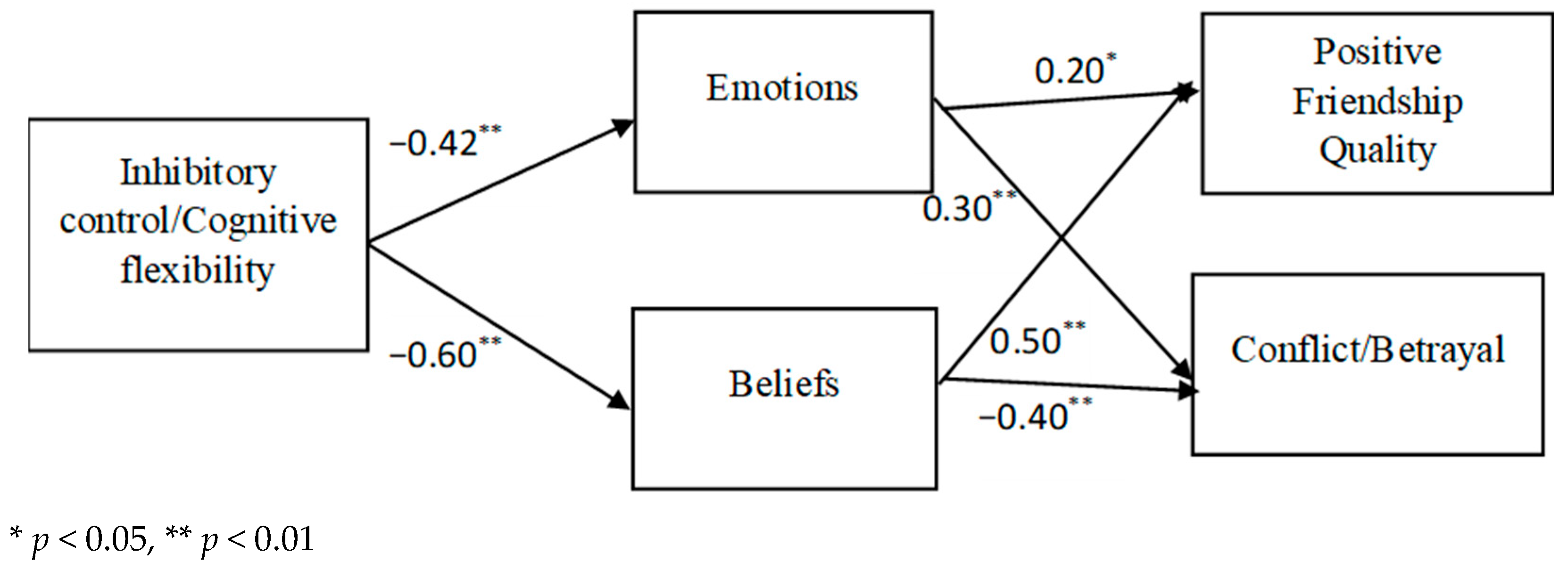

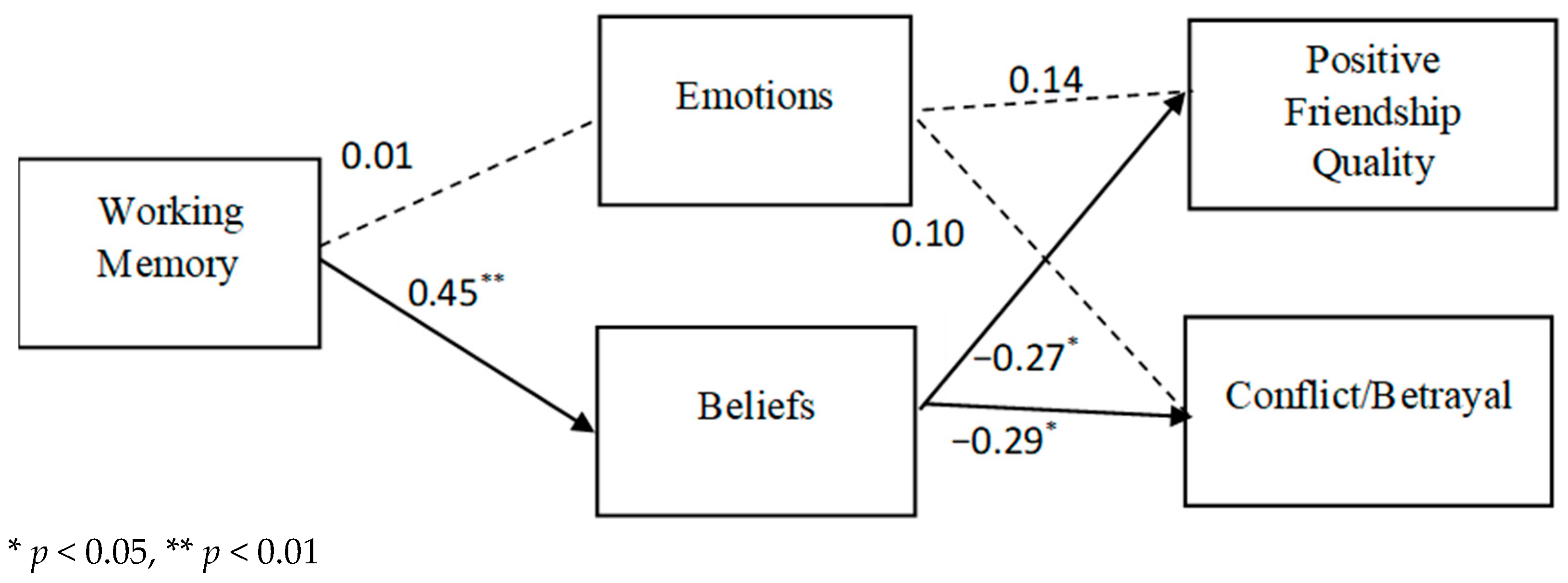

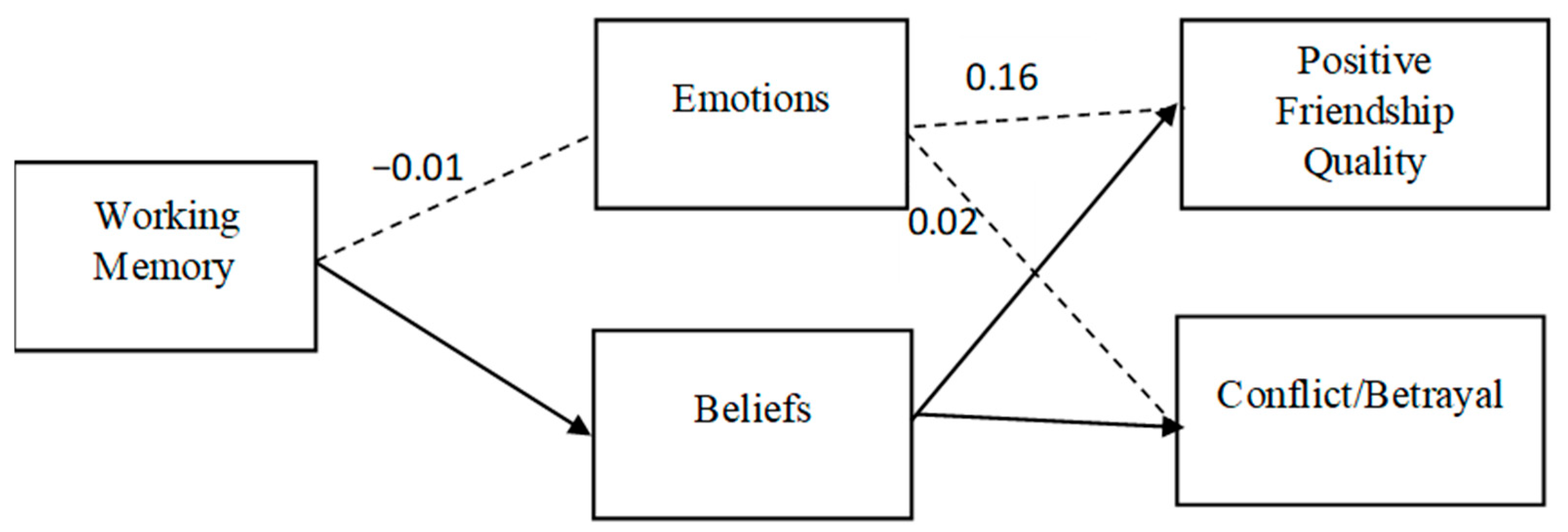

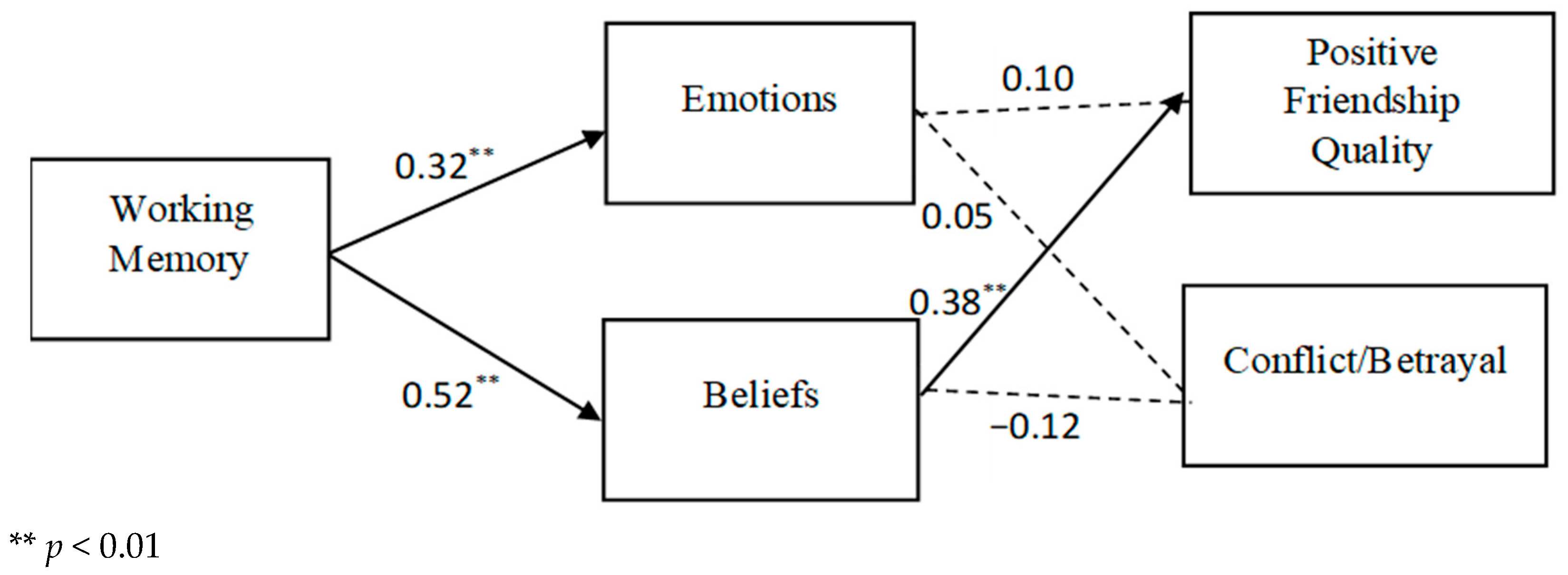

3.3. Structural Models

4. Discussion

4.1. Inhibitory Control and Cognitive Flexibility (Model 1)

4.2. Working Memory (Model 2)

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADHD | Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder |

| NT | Neurotypical Development |

| ND | Neurodivergent |

| ToM | Theory of Mind |

| ER | Emotion Regulation |

| CR | Cognitive Reappraisal |

| ES | Emotion Suppression |

| EFs | Executive Functions |

| SEM | Structural Equation Modeling |

Appendix A. Measurement Models’ Statistics

References

- Adler, L. A., Faraone, S. V., Spencer, T. J., Berglund, P., Alperin, S., & Kessler, R. C. (2017). The structure of adult ADHD. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 26(1), 1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonopoulou, K., Chaidemenou, A., & Kouvava, S. (2019). Peer acceptance and friendships among primary school pupils: Associations with loneliness, self-esteem and school engagement. Educational Psychology in Practice: Theory, Research and Practice in Ecucational Psychology, 35(3), 339–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonopoulou, K., Xanthou, E., & Kouvava, S. (2022). Best friendship relationships: How are they perceived by primary school children in Greece? Education 3–13. International Journal of Primary, Elementary and Early Years Education, 50(8), 1018–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, S. G. (1946). An analysis of certain psychological tests used for the evaluation of brain injury. Psychological Monographs, 60, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avramidis, E., Aroni, K., & Strogilos, V. (2022). Social participation and quality of best friendship of students with moderate learning difficulties in early adolescence: A longitudinal study. Australasian Journal of Special and Inclusive Education, 46(1), 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avramidis, E., Avgeri, G., & Strogilos, V. (2018). Social participation and friendship quality of students with special educational needs in regular Greek primary schools. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 33(2), 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baggetta, P., & Alexander, P. A. (2016). Conceptualization and operationalization of executive function. Mind, Brain, and Education, 10(1), 10–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagwell, C. L., & Bukowski, W. M. (2018). Friendship in childhood and adolescence: Features, effects, and processes. In W. M. Bukowski, B. Laursen, & K. H. Rubin (Eds.), Handbook of peer interactions, relationships, and groups (2nd ed., pp. 371–390). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, R., Watling, D., & Caputi, M. (2011). Peer relations and understanding of faux pas: Longitudinal evidence for bidirectional associations. Child Development, 82(6), 1887–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauminger, N., Schorr-Edelsztein, H., & Morash, J. (2005). Social information processing and emotional understanding in children with learning disabilities. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 38(1), 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benavides-Nieto, A., Romero-López, M., Quesada-Conde, A. B., & Corredor, G. A. (2017). Basic executive functions in early childhood education and their relationship with social competence. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences, 237, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berenguer Forner, C. B., Miranda, B. R., Fortea, I. B., Castellar, R. G., Diago, C. C., & Casas, A. M. (2017). ADHD Symptoms and peer problems: Mediation of executive function and theory of mind. Psicothema, 29(4), 514–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, J. N., Boyle, J. M. E., & Kelly, S. W. (2010). Do tasks make a difference? Accounting for heterogeneity of performance of children with reading difficulties on tasks of executive function: Findings from a meta-analysis. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 28(1), 133–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, B. K. (1982). An index of empathy for children and adolescents. Child Development, 53(2), 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunford, N., Evans, S. W., & Langberg, J. M. (2018). Emotion dysregulation is associated with social impairment among young adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Attention Disorders, 22(1), 66–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caporaso, J. S., Boseovski, J. J., & Marcovitch, S. (2019). The individual contributions of three executive function components to preschool social competence. Infant and Child Development, 28(4), e2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputi, M., Lecce, S., Pagnin, A., & Banerjee, R. (2012). Longitudinal effects of theory of mind on later peer relations: The role of prosocial behavior. Developmental Psychology, 48(1), 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caravita, S. C. S., Di Blasio, P., & Salmivalli, C. (2010). Early adolescents’ participation in bullying: Is ToM involved? The Journal of Early Adolescence, 30(1), 138–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardillo, R., Garcia, R. B., Mammarella, I. C., & Cornoldi, C. (2018). Pragmatics of language and theory of mind in children with dyslexia with associated language difficulties of nonverbal learning disabilities. Applied Neuropsychology: Child, 7(3), 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlson, S. M., & Moses, L. J. (2001). Individual differences in inhibitory control and children’s theory of mind. Child Development, 72(4), 1032–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpendale, J., & Lewis, C. (2006). How children develop social understanding. Blackwell Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F. F. (2007). Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 14(3), 464–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciarrochi, J., Heaven, P. C. L., & Supavadeeprasit, S. (2008). The link between emotion identification skills and socio-emotional functioning in early adolescence: A 1-year longitudinal study. Journal of Adolescence, 31(5), 565–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciarrochi, J., Parker, P., Sahdra, B., Kashdan, T., Kiuru, N., & Conigrave, J. (2017). When empathy matters: The role of sex and empathy in close friendships. Journal of Personality, 85(4), 494–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crick, N. R., & Dodge, K. A. (1994). A review and reformulation of social information-processing mechanisms in childrens’ social adjustment. Psychological Bulletin, 115(1), 74–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisci, G., Caviola, S., Cardillo, R., & Mammarella, I. C. (2021). Executive functions in neurodevelopmental disorders: Comorbidity overlaps between attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder and specific learning disorders. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 15, 594234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutting, L. E., Materek, A., Cole, C. A., Levine, T. M., & Mahone, E. M. (2009). Effects of fluency, oral language, and executive function on reading comprehension performance. Annals of Dyslexia, 59(1), 34–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Wied, M., Branje, S. J. T., & Meeus, W. H. J. (2007). Empathy and conflict resolution in friendship relations among adolescents. Aggressive Behavior, 33(1), 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, A. (2013). Executive functions. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 135–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, A. (2014). Understanding executive functions: What helps or hinders them and how executive functions and language development mutually support one another. Perspectives on Language and Literacy, 40(2), 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Doikou-Avlidou, M. (2015). The educational, social, and emotional experiences of students with dyslexia: The perspective of postsecondary education students. International Journal of Special Education, 30(1), 132–145. [Google Scholar]

- Eggum-Wilkens, N. D., Fabes, R. A., Castle, S., Zhang, L., Hanish, L. D., & Martin, C. L. (2014). Playing with others: Head Start children’s peer play and relations with kindergarten school competence. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 29(3), 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyuboglu, D., Bolat, N., & Eyuboglu, M. (2018). Empathy and theory of mind abilities of children with specific learning disorder (SLD). Psychiatry and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 28(2), 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, E., Begeer, S., Hunt, C., & de Rosnay, M. (2014). False-belief understanding and social preference over the first 2 years of school: A longitudinal study. Child Development, 85(6), 2389–2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freed, J., McBean, K., Adams, C., Lockton, E., Nash, M., & Law, J. (2015). Performance of children with social communication disorder on the Happe’ strange stories: Physical and mental state responses and relationship to language ability. Journal of Communication Disorders, 55(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabay, Y., Shamay-Tsoory, S. G., & Goldfarb, L. (2016). Cognitive and emotional empathy in typical and impaired readers and its relationship to reading competence. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 38(10), 1131–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gambin, M., & Sharp, C. (2016). The differential relations between empathy and internalizing and externalizing symptoms in inpatient adolescents. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 47(6), 966–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Andres, E., Huertas-Martínez, J. A., Ardura, A., & Fernández-Alcaraz, C. (2010). Emotional regulation and executive function profiles of functioning related to the social development of children. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 5, 2077–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgas, J., Paraskevopoulos, I., Bezevengis, H. N., & Giannitsas, A. (1997). The hellenic WISC-III, wechsler intelligence scales for children. Examiner’s guide. Hellinika Grammata. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Ger, E., & Roebers, C. M. (2023). The relationship between executive functions, working memory, and intelligence in kindergarten children. Journal of Intelligence, 11(4), 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez-Garibello, C., & Talwar, V. (2015). Can you read my mind? Age as a moderator in the relationship between theory of mind and relational aggression. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 39(6), 552–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J. J. (2015). Emotion regulation: Current status and future prospects. Psychological Inquiry, 26(1), 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groves, N. B., Wells, E. L., Soto, E. F., Marsh, C. L., Jaisle, E. M., Harvey, T. K., & Kofle, M. J. (2022). Executive functioning and emotion regulation in children with and without ADHD. Research on Child and Adolescent Psychopathology, 50, 721–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullone, E., & Taffe, J. (2012). The emotion regulation questionnaire for children and adolescents (ERQ–CA): A psychometric evaluation. Psychological Assessment, 24(2), 409–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gvirts, H. Z., & Perlmutter, R. (2020). What guides us to neurally and behaviorally align with anyone specific? A neurobiological model based on fNIRS hyperscanning studies. The Neuroscientist, 26(2), 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Happé, F. G. E. (1994). An advanced test of theory of mind: Understanding of story characters’ thoughts and feelings by able autistic, mentally handicapped, and normal children and adults. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 24(2), 129–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, M. A., & Orth, U. (2020). The link between self-esteem and social relationships: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 119(6), 1459–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartup, W. W., & Stevens, N. (1997). Friendships and adaptation in the life course. Psychological Bulletin, 121(3), 355–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, C. J., Kim-Spoon, J., & Deater-Deckard, K. (2016). Linking executive function and peer problems from early childhood through middle adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 44(1), 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoza, B., Gerdes, A. C., Mrug, S., Hinshaw, S. P., Bukowski, W. M., Gold, J. A., Arnold, L. E., Abikoff, H. B., Conners, C. K., Elliott, G. R., Greenhill, L. L., Hechtman, L., Jensen, P. S., Kraemer, H. C., March, J. S., Newcorn, J. H., Severe, J. B., Swanson, J. M., Vitiello, B., … Wigal, T. (2005). Peer-assessed outcomes in the multimodal treatment study of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 34(1), 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.-T. T., & Tran-Chi, V.-L. (2020). Exploration of the development of children’s empathy. MIER Journal of Educational Studies Trends and Practices, 10(1), 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, C., & Devine, R. T. (2015). A social perspective on theory of mind. In M. E. Lamb, & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology and developmental science: Socioemotional processes (pp. 564–609). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulme, C., & Snowling, M. J. (2009). Developmental disorders of language learning and cognition. Wiley Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- John, A., Friedmann, Y., DelPozo-Banos, M., Frizzati, A., Ford, T. J., & Thapar, A. (2022). Association of school absence and exclusion with recorded neurodevelopmental disorders, mental disorders, or self-harm: A nationwide, retrospective, electronic cohort study of children and young people in Wales, UK. The Lancet Psychiatry, 9(1), 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, O. P., & Gross, J. J. (2004). Healthy and unhealthy emotion regulation: Personality processes, individual differences, and life span development. Journal of Personality, 72(6), 1301–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalka, D., & Lockiewicz, M. (2018). Happiness, life satisfaction, resiliency and social support in students with dyslexia. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 65(5), 493–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidd, D. C., & Castano, E. (2013). Reading literary fiction improves theory of mind. Science, 342(6156), 377–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkinos, C. M., & Voulgaridou, I. (2017). Relational and cyber aggression among adolescents: Personality and emotion regulation as moderators. Computers in Human Behavior, 68, 528–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkinos, C. M., Voulgaridou, I., & Markos, A. (2016). Personality and relational aggression: Moral disengagement and friendship quality as mediators. Personality and Individual Differences, 95, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouvava, S., Antonopoulou, K., Kokkinos, C. M., & Ralli, A. M. (2025a). Executive functions and friendships in primary school children with ADHD, dyslexia and neurotypical development: A comparative study. Topics in Language Disorders, 45(3), 199–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouvava, S., Antonopoulou, K., Kokkinos, C. M., & Ralli, A. M. (2025b). Social understanding and friendships in children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder or dyslexia. Behavioral Sciences, 15(2), 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kouvava, S., Antonopoulou, K., Kokkinos, C. M., Ralli, A. M., & Maridaki-Kassotaki, K. (2022). Friendship quality, emotion understanding, and emotion regulation of children with and without attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder or specific learning disorder. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, 27(1), 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouvava, S., Antonopoulou, K., Kokkinos, C. M., & Voulgaridou, I. (2023). Psychometric properties of the Greek translation of the Friendship Quality Questionnaire. Psychology in the Schools, 60(4), 985–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhnert, R. L., Begeer, S., Fink, E., & de Rosnay, M. (2017). Gender-differentiated effects of theory of mind, emotion understanding, and social preference on prosocial behavior development: A longitudinal study. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 154, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladopoulos, E. (2019). The speed and flexibility of visual attention in secondary school students with learning difficulties. Panhellenic Conference on Education Sciences, 9, 416–426. (In Greek) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leseyane, M., Mandende, P., Makgato, M., & Cekiso, M. (2018). Dyslexic learners’ experiences with their peers and teachers in special and mainstream primary schools in North-West Province. African Journal of Disability, 7, a363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonergan, A., Doyle, C., Cassidy, C., MacSweeney Mahon, S., Roche, R. A. P., Boran, L., & Bramham, J. (2019). A meta-analysis of executive functioning in dyslexia with consideration of the impact of comorbid ADHD. Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 31(7), 725–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löytömäki, J., Laakso, M. L., & Huttunen, K. (2023). Social-emotional and behavioural difficulties in children with neurodevelopmental disorders: Emotion perception in daily life and in a formal assessment context. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 53, 4744–4758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, D. R., Kisbu-Sakarya, Y., & Gottschall, A. C. (2013). Developments in mediation analysis. In T. D. Little (Ed.), Oxford library of psychology. The Oxford handbook of quantitative methods: Statistical analysis (pp. 338–360). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mammarella, I. C., Ghisi, M., Bomba, M., Bottesi, G., Caviola, S., Broggi, F., & Nacinovich, R. (2016). Anxiety and depression in children with nonverbal learning disabilities, reading disabilities, or typical development. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 49(2), 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maoz, H., Gvirts, H. Z., Sheffer, M., & Bloch, Y. (2019). Theory of Mind and Empathy in Children With ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders, 23(11), 1331–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marton, I., Wiener, J., Rogers, M., & Moore, C. (2015). Friendship characteristics of children with ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders, 19(10), 872–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mary, A., Slama, H., Mousty, P., Massat, I., Capiau, T., Drabs, V., & Peigneux, P. (2016). Executive and attentional contributions to theory of mind deficit in attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Child Neuropsychology, 22(3), 345–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQuade, J. D., Breaux, R., Mordy, A. E., & Taubin, D. (2021). Childhood ADHD symptoms, parent emotion socialization, and adolescent peer problems: Indirect effects through emotion dysregulation. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 50(12), 2519–2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meuwese, R., Cillessen, A. H. N., & Güroǧlu, B. (2017). Friends in high places: A dyadic perspective on peer status as predictor of friendship quality and the mediating role of empathy and prosocial behaviour. Social Development, 26(3), 503–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikami, A. Y., & Hinshaw, S. P. (2003). Buffers of peer rejection among girls with and without ADHD: The role of popularity with adults and goal-directed solitary play. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 31(4), 381–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, S. E., Avila, B. N., & Reavis, R. E. (2020). Thoughtful friends: Executive function relates to social problem solving and friendship quality in middle childhood. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 181(1), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, S. E., Reavis, R. E., & Avila, B. N. (2018). Associations between theory of mind, executive function, and friendship quality in middle childhood. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 64(3), 397–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milligan, K., Astington, J. W., & Dack, L. A. (2007). Language and theory of mind: Μeta-analysis of the relation between language ability and false-belief understanding. Child Development, 78(2), 622–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsopoulou, E., & Giovazolias, T. (2013). The relationship between perceived parental bonding and bullying: The mediating role of empathy. The European Journal of Counselling Psychology, 2(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyake, A., Friedman, N. P., Emerson, M. J., Witzki, A. H., Howerter, A., & Wager, T. D. (2000). The unity and diversity of executive functions and their contributions to complex “Frontal Lobe” tasks: A latent variable analysis. Cognitive Psychology, 41(1), 49–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrug, S., Hoza, B., Gerdes, A. C., Hinshaw, S., Arnold, L. E., Hechtman, L., & Pelham, W. E. (2009). Discriminating between children with ADHD and classmates using peer variables. Journal of Attention Disorders, 12(4), 372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2017). Mplus: Statistical analysis with latent variables: User’s guide (Version 8). Authors. [Google Scholar]

- Nadeau, M. F., Massé, L., Argumedes, M., & Verret, C. (2020). Education for students with neurodevelopmental disabilities: Resources and educational adjustments. Handbook of Clinical Neurology, 174, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neprily, K. M., Climie, E. A., McCrimmon, A., & Makarenko, E. (2025). Why can’t we be friends? A narrative review of the challenges of making and keeping friends for children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Frontiers in Developmental Psychology, 2, 1390791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Normand, S., Lambert, M., Guiet, J., Brendgen, M., Bakeman, R., & Mikami, A. Y. (2024). Peer contagion dynamics in the friendships of children with ADHD. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 65(12), 1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Normand, S., Schneider, B. H., Lee, M. D., Maisonneuve, M.-F., Kuehn, S. M., & Robaey, P. (2011). How do children with ADHD (mis)manage their real-life dyadic friendships? A multi-method investigation. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 39(2), 293305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Toole, S. E., Monks, C. P., & Tsermentseli, S. (2017). Executive function and theory of mind as predictors of aggressive and prosocial behavior and peer acceptance in early childhood. Social Development, 26(4), 907–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özyurt, G., Öztürk, Y., Turan, S., Çıray, R. O., Tanıgör, E. K., Ermiş, Ç., Tufan, A. E., & Akay, A. (2024). Are communication skills, emotion regulation and theory of mind skills impaired in adolescents with developmental dyslexia? Developmental Neuropsychology, 49(3), 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, T. C., Panayiotou, G., Spanoudis, G., & Natsopoulos, D. (2005). Evidence of poor planning in children with attention deficits. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 33(5), 611–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parke, E. M., Becker, M. L., Graves, S. J., Baily, A. R., Paul, M. G., Freeman, A. J., & Allen, D. N. (2021). Social cognition in children with ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders, 25(4), 519–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, J. G., & Asher, S. R. (1993). Friendship and friendship quality in middle childhood: Links with peer group acceptance and feelings of loneliness and social dissatisfaction. Developmental Psychology, 29(4), 611–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, J. G., Rubin, K. H., Earth, S., Wojslawowicz, J. C., & Buskirk, A. A. (2006). Peer relationships, child development, and adjustment: A developmental psychopathology perspective. In D. Cicchetti (Ed.), Developmental psychopathology: Vol. 3: Risk, disorder, and adaptation (pp. 419–493). Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Perner, J., & Wimmer, H. (1985). “John thinks that Mary thinks that…” Attribution of second order beliefs by 5–10 year old children. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 39, 437–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, A., & Shamay-Tsoory, S. (2013). Understanding emotional and cognitive empathy: A neuropsychological perspective. In S. Baron-Cohen, H. Tager-Flusberg, & M. V. Lombardo (Eds.), Understanding other minds: Perspectives from developmental social neuroscience (pp. 178–194). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, C. C., & Siegal, M. (2002). Mindreading and moral awareness in popular and rejected preschoolers. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 20(2), 205–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Policarpo, V. (2015). What is a friend? An exploratory typology of the meanings of friendship. Social Sciences, 4(1), 171–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renouf, A., Brendgen, M., Séguin, J. R., Vitaro, F., Boivin, M., Dionne, G., Tremblay, R. E., & Pérusse, D. (2010). Interactive links between theory of mind, peer victimization, and reactive and proactive aggression. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 38(8), 1109–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rielly, N. E., Craig, W. M., & Parker, K. C. H. (2006). Peer and parenting characteristics of boys and girls with subclinical attention problems. Journal of Attention Disorders, 9(4), 598–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rokeach, A., & Wiener, J. (2022). Predictors of friendship quality in adolescents with and without attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. School Mental Health, 14, 328–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, A. J., & Asher, S. R. (2004). Children’s strategies and goals in response to help-giving and help-seeking tasks within a friendship. Child Development, 75(3), 749–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, A. J., Borowski, S. K., Spiekerman, A., & Smith, R. L. (2022). Children’s friendships. In P. K. Smith, & C. H. Hart (Eds.), The wiley-blackwell handbook of childhood social development (3rd ed., pp. 487–502). Wiley Blackwell. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruffman, T., Slade, L., & Crowe, E. (2002). The relationship between children’s and mother’s mental state language and theory-of-mind understanding. Child Development, 73(3), 734–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambol, S., Suleyman, E., & Ball, M. (2025). The interplay of hot and cool executive functions: Implications for a unified executive framework. Cognitive Systems Research, 91, 101360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz-Mette, R. A., Shankman, J., Dueweke, A. R., Borowski, S., & Rose, A. J. (2020). Relations of friendship experiences with depressive symptoms and loneliness in childhood and adolescence: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 146, 664–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sendil, C. O., & Erden, F. T. (2014). Peer preference: A way of evaluating social competence and behavioural well-being in early childhood. Early Child Development and Care, 184(2), 230–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverstein, M. J., Faraone, S. V., Leon, T. L., Biederman, J., Spencer, T. J., & Adler, L. A. (2020). The relationship between executive function deficits and DSM-5-defined ADHD symptoms. Journal of Attention Disorders, 24(1), 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slaughter, V. (2015). Theory of mind in infants and young children: A review. Australian Psychologist, 50(3), 169–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, S., Kazemi, F., Maleki, N., & Soltani, Z. (2013). Deficits in theory of mind and executive function in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Novel Applied Sciences, 2(10), 449–455. [Google Scholar]

- Spender, K., Chen, Y.-W. R., Wilkes-Gillan, S., Parsons, L., Cantrill, A., Simon, M., Garcia, A., & Cordier, R. (2023). The friendships of children and youth with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A systematic review. PLoS ONE, 18(8), e0289539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statiri, V., & Andreou, E. (2017). Social skills, social status, and sense of belonging of students with and without special educational needs in the general elementary school. Preschool and Primary Education, 5(2), 1–26. (In Greek). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroop, J. R. (1935). Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 18(6), 643–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Undheim, A.-M., Wichstrøøm, L., & Sund, A.-M. (2011). Emotional and behavioural problems among school adolescents with and without reading difficulties as measured by the youth self-report: A one year follow-up study. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 55(3), 291–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Bedem, N. P., Willems, D., Dockrell, J. E., van Alphen, P. M., & Rieffe, C. (2019). Interrelation between empathy and friendship development during (pre)adolescence and the moderating effect of developmental language disorder: A longitudinal study. Social Development, 28(3), 599–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenberg, R. J., & Lance, C. E. (2000). A review and synthesis of the measurement invariance literature: Suggestions, practices, and recommendations for organizational research. Organizational Research Methods, 3(1), 4–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Elst, W., Van Boxtel, M. P. J., Van Breukelen, G. J. P., & Jolles, J. (2006). The Stroop Color-Word Test influence of age, sex, and eduation; and normative data for a large sample across the adult age range. Assessment, 13(1), 62–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van de Schoot, R., Lugtig, P., & Hox, J. (2012). A checklist for testing measurement invariance. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 9(4), 486–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassilopoulos, S. P., Vlachou, E., Brouzos, A., Moberly, N. J., Misailidi, P., & Diakogiorgi, K. (2021). Ability to distinguish genuine from non-genuine smiles in children aged 10- to 12-years: Associations with peer status, gender, social anxiety, and level of empathy. Hellenic Journal of Psychology, 18(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlahou, C. H., & Kosmidis, M. H. (2002). The Greek trail making test: Preliminary normative data for clinical and research use. Psychology: The Journal of the Hellenic Psychological Society, 9(3), 336–352. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X., & Feng, T. (2024). Does executive function affect children’s peer relationships more than emotion understanding? A Longitudinal study based on latent growth model. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 66, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Hawk, S. T., Tang, Y., Schlegel, K., & Zou, H. (2019). Characteristics of emotion recognition ability among primary school children: Relationships with peer status and friendship quality. Child Indicators Research, 12(4), 1369–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wåhlstedt, C., Thorell, L. B., & Bohlin, G. (2009). Heterogeneity in ADHD: Neuropsychological pathways, comorbidity and symptom domains. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 37(4), 551–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wechsler, D. (1991). Weschler intelligence scale for children (3rd ed.). The Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Weimer, A. A., Warnell, K. R., Ettekal, I., Cartwright, K. B., Guajardo, N. R., & Liew, J. (2021). Correlates and antecedents of theory of mind development during middle childhood and adolescence: An integrated model. Developmental Review, 59(4), 100945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellman, H. M. (2014). Making minds: How theory of mind develops. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, S. G., Finch, J. F., & Curran, P. J. (1995). Structural equation models with nonnormal variables: Problems and remedies. In R. H. Hoyle (Ed.), Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues, and applications (pp. 56–75). Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Wiener, J., & Schneider, B. H. (2002). A multisource exploration of friendship patterns of children with learning disabilities. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 30, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woltering, S., Lishak, V., Hodgson, N., Granic, I., & Zelazo, P. D. (2016). Executive function in children with externalizing and comorbid internalizing behavior problems. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 57(1), 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yavuz, H. M., Colasante, T., Galarneau, E., & Malti, T. (2024). Empathy, sympathy, and emotion regulation: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 150(1), 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| NT Children (n = 64) | Children with Dyslexia (n = 64) | Children with ADHD (n = 64) | Differences | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| f | % | f | % | f | % | χ2 | p | ||

| Gender | Boy | 31 | 48.4 | 33 | 51.6 | 32 | 50 | 0.13 | 0.94 |

| Girl | 33 | 51.6 | 31 | 48.4 | 32 | 50 | |||

| Grade level | 3rd | 16 | 25 | 16 | 25 | 16 | 25 | 0.21 | 0.99 |

| 4th | 17 | 26.6 | 15 | 23.4 | 16 | 25 | |||

| 5th | 16 | 25 | 17 | 26.6 | 16 | 25 | |||

| 6th | 15 | 23.4 | 16 | 25 | 16 | 25 | |||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | F(2,104) | p | ||

| Age (in years) | 9.67 | 1.15 | 9.82 | 1.15 | 9.81 | 1.16 | 0.29 | 0.75 | |

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Beliefs (2nd order & advanced ToM) | 18.25 | 5.32 | |||||

| 2. Emotions (affective empathy & ER) | 55.39 | 5.97 | 0.03 | ||||

| 3. Inhibitory control/cognitive flexibility (response time) (EFs) | 225.50 | 52.28 | 0.08 | −0.17 | |||

| 4. Working Memory (EFs) | 2.86 | 1.10 | 0.45 ** | 0.00 | 0.18 | ||

| 5. Pos. Friendship Quality | 2.84 | 0.84 | 0.36 ** | 0.15 | −0.07 | 0.30 * | |

| 6. Conflict/Betrayal | 2.51 | 0.71 | −0.31 * | 0.09 | −0.22 | −0.20 | −0.09 |

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Beliefs (2nd order & advanced ToM) | 21.62 | 6.46 | |||||

| 2. Emotions (affective empathy & ER) | 56.19 | 7.34 | 0.12 | ||||

| 3. Inhibitory control/cognitive flexibility (response time) (EFs) | 220.81 | 68.26 | −0.56 ** | −0.18 | |||

| 4. Working Memory (EFs) | 3.50 | 1.14 | 0.33 ** | −0.03 | −0.22 | ||

| 5. Pos. Friendship Quality | 3.26 | 0.84 | 0.40 ** | 0.21 | −0.30 * | −0.05 | |

| 6. Conflict/Betrayal | 2.37 | 0.67 | −0.23 | −0.01 | 0.32 ** | 0.04 | −0.24 |

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Beliefs (2nd order & advanced ToM) | 33.39 | 6.38 | |||||

| 2. Emotions (affective empathy & ER) | 62.08 | 5.57 | 0.49 ** | ||||

| 3. Inhibitory control/cognitive flexibility (response time) (EFs) | 82.48 | 40.02 | −0.56 ** | −0.44 ** | |||

| 4. Working Memory (EFs) | 6.39 | 1.64 | 0.52 ** | 0.32 * | −0.52 ** | ||

| 5. Pos. Friendship Quality | 4.36 | 0.55 | 0.54 ** | 0.35 ** | −0.72 ** | 0.44 ** | |

| 6. Conflict/Betrayal | 1.82 | 0.43 | −0.25 * | −0.10 | 0.50 ** | −0.33 ** | −0.59 ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kouvava, S.; Antonopoulou, K.; Ralli, A.M.; Voulgaridou, I.; Kokkinos, C.M. Navigating Social Inclusion: How Social and Cognitive Factors Relate to Friendship Quality in Children with ADHD, Dyslexia, and Neurotypical Development. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1566. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111566

Kouvava S, Antonopoulou K, Ralli AM, Voulgaridou I, Kokkinos CM. Navigating Social Inclusion: How Social and Cognitive Factors Relate to Friendship Quality in Children with ADHD, Dyslexia, and Neurotypical Development. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(11):1566. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111566

Chicago/Turabian StyleKouvava, Sofia, Katerina Antonopoulou, Asimina M. Ralli, Ioanna Voulgaridou, and Constantinos M. Kokkinos. 2025. "Navigating Social Inclusion: How Social and Cognitive Factors Relate to Friendship Quality in Children with ADHD, Dyslexia, and Neurotypical Development" Education Sciences 15, no. 11: 1566. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111566

APA StyleKouvava, S., Antonopoulou, K., Ralli, A. M., Voulgaridou, I., & Kokkinos, C. M. (2025). Navigating Social Inclusion: How Social and Cognitive Factors Relate to Friendship Quality in Children with ADHD, Dyslexia, and Neurotypical Development. Education Sciences, 15(11), 1566. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111566