Abstract

Several studies in the educational field have explored the use of digital technologies and how they promote the strengthening of socioemotional competencies. However, most of these studies have focused on students, leaving their application to teachers in the background. This systematic review identifies and analyzes studies on the application of digital tools aimed at strengthening the socioemotional competencies of teachers in order to answer the following question: What digital technologies have been implemented to support the socioemotional development of teachers in educational settings and what are their results? The study followed the PRISMA 2020 guidelines, based on the identification of research in the ERIC, EBSCO, OpenAlex, Sciencedirect, Scopus, PubMed, arXiv, and Google Scholar databases. Out of 451 research studies identified in an observation window open to any year, 57 studies were selected for analysis. The digital technologies reviewed to strengthen teachers’ socioemotional competencies were grouped into three categories: self-reflection tools (65%), such as digital diaries and blogs; intentional emotional development technologies (68%), such as virtual reality and gamification; and collaborative platforms (37%), such as social networks. Their use evidenced the development of CASEL model competencies: self-awareness and responsible decision-making (86%), self-regulation (81%), social awareness (58%) and relational skills (68%). It is recommended to integrate these technologies in an intentional and contextualized way in teacher training, in order to enhance their well-being, emotional preparation, and prosperity even in the midst of current educational challenges.

1. Introduction

1.1. Importance of Teachers’ Socioemotional Competencies (SECs)

Socioemotional Competencies (SECs) in teachers not only favor well-being at the personal level of teachers, but also influence their pedagogical and professional practices (Concha-Herrera et al., 2025; Corcoran & Tormey, 2012; Lozano-Peña et al., 2021; Sarpong, 2025). The teaching profession specifically involves a modeling role in the interaction with students (Ferreira et al., 2020; Weissberg, 2019); therefore, it is essential that teachers can be competent in the socioemotional aspect.

The literature reports vast evidence of the potential of these competencies, which are related to educational quality (Valverde Forttes, 2015), improving classroom management and climate (Müller et al., 2020), the teacher–student relationship, academic performance, and the personal and social development of students (Collie et al., 2016; Roorda et al., 2017). Likewise, teachers who demonstrate a high development of SECs significantly influence higher levels of student engagement (Delgado-Arenas et al., 2023; Gebre et al., 2025).

In this sense, SECs in teachers are fundamental in the school context and dynamics (Perikleous, 2024). A relevant synthesis to mention is the one made by Vaello Orts and Vaello Pecino (2018), who highlight the contribution and relevance of SECs in teachers and establish five main purposes of these competencies: instrumental purpose, improving the academic, social, and personal aspects of students; social purpose, acting as an important factor of social influence (they can produce positive changes in the thoughts, attitudes, and behaviors of students and their families); ecological purpose, allowing adaptation to the context and effective response to conflictual situations in the school context; affective purpose, providing satisfaction and favoring the personal well-being of teachers; and finally, a preventive purpose, acting as a protective factor on self-esteem and emotional balance, both in students, and in teachers, preventing burnout, stress, or anxiety (Sáez-Delgado et al., 2023).

1.2. Theoretical Models and Definition of SECs

The literature reports various theoretical models to address the study of teachers’ SECs, among them are the models focused on emotional intelligence as skill development (Salovey & Mayer, 1989) and as a personality trait (Petrides & Furnham, 2001), as well as theoretical models focused on emotional regulation focused on the process of emotion regulation (Gross, 1998; Thompson, 1994). Among the most recent theoretical models are those that have considered both the social and emotional component, among them the models of Prosocial Classroom (Jennings et al., 2019), Emotional Competencies (Bisquerra & Pérez Escoda, 2007), Social and Emotional Competency School (Collie, 2020), Domains and Manifestations of Social-Emotional Competences (DOMASEC) (Schoon & Lyons-Amos, 2017), and one of the most cited and used as a reference for the development of other theoretical models, the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL) model (CASEL, 2020).

The concept of SECs presents an important sociohistorical evolution. In its first approaches, the concept was understood as the set of skills, motivations, knowledge, or abilities that allow the effective management of social and emotional situations (Elias et al., 1997). Currently, the concept has evolved and has been expanded, not only considering the skills necessary to effectively manage social and emotional situations, but also recognizing that this can lead to personal and collective well-being and thriving (Collie, 2020; Sáez-Delgado et al., 2024). Thus, SECs are skills, attitudes, and knowledge that allow teachers to recognize, understand, regulate, and express their emotions. At the same time, they can develop social skills necessary to build empathetic and effective relationships (Schonert-Reichl, 2019).

While the theoretical models reviewed present different emphases, together they offer a complementary vision that guides the potential use of digital technologies in socioemotional teacher training. The CASEL model is the most consolidated framework, defining five core competencies (self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision-making) (CASEL, 2020). Its structured and widely validated nature has facilitated the development of digital platforms, applications, and online training programs explicitly organized around these competencies, making it an operative reference framework for designing technopedagogical interventions. Meanwhile, DOMASEC expands this perspective by organizing competencies into domains (self, others, tasks/challenges) and manifestations (affective, cognitive, behavioral) (Schoon & Lyons-Amos, 2017), which is particularly useful in digital environments as it allows for precise mapping, the dimensions of which can be stimulated through simulations, interactive resources, or socioemotional learning analytics. The Prosocial Classroom Model emphasizes teacher well-being as a prerequisite for creating positive classroom climates (Jennings et al., 2019), suggesting that technologies can mediate self-care and self-regulation processes. Complementarily, the emotional competencies framework highlights the intrapersonal dimension (emotional awareness and regulation) (Bisquerra & Pérez Escoda, 2007), which is central for the design of digital resources aimed at emotional training. Finally, the Social and Emotional Competency School Model (Collie, 2020), integrates the school perspective, emphasizing the interaction between individual and contextual competencies, which opens possibilities for technologies to support multilevel interventions at the school level. In short, although they differ in their level of analysis (individual, relational, or institutional) and in the way they organize competencies, all models offer promising potential when considering the integration of digital technologies, as they can improve both intrapersonal development and the creation of healthier and more effective socioemotional learning environments.

1.3. The Potential of Technologies for the Promotion of Teachers’ SECs

Considering that existing SEL models could maximize their benefits by incorporating the use of technology, it is essential to evaluate its inclusion in order to effectively promote SEL among teachers. In fact, in the current era, the value of technologies in promoting a more holistic approach to the teaching process is widely recognized (Kruty et al., 2024) and, increasingly, incorporates the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) (Sethi & Jain, 2024). In this regard, SEL promotion and training have not been immune to these changes, and the importance of moving from traditional formats to formats that integrate the use of technology to provide and ensure greater efficiency, sustainability, and scalability has become evident (CASEL, 2020; Durlak et al., 2022).

In this way, digital technology becomes an ally to promote the socioemotional development of teachers (Slovák & Fitzpatrick, 2015). Thanks to their versatility and accessibility, tools such as interactive platforms, mobile applications (Wetcho & Na-Songkhla, 2022), social networks, artificial intelligence (Liu & Chang, 2024), virtual reality (Mouw et al., 2020), or audiovisual resources (TamilSelvi & Thangarajathi, 2011) can be incorporated into structured programs. These can include courses, workshops, or spaces for professional accompaniment and reflection, allowing teachers to work on their socioemotional well-being by generating positive changes in the way they think, relate, and teach (Wetcho & Na-Songkhla, 2022).

Several investigations have documented how these digital tools foster participation, motivation, and the development of SECs mainly in students (Carrillo & Flores, 2020; De La Torre Quispe, 2022), addressing less frequently their impact on the teaching role (Lozano-Peña et al., 2021). An example of this is a study conducted in Pakistan that considered a teacher training program with technology support in public schools in rural areas, which evidenced among its results an improvement in the interaction between parents and teachers and greater self-efficacy and subjective well-being of teachers. Likewise, the results of the application evidenced the feeling of acceptability, cultural appropriateness, viability, and sustainability of the program (Hamdani et al., 2021; Jara-Coatt et al., 2025).

1.4. Gap and Research Question

Despite the importance and evidence of the use of technology to promote socioemotional development in the educational context, several studies highlight that these competencies are not worked on in a clear or constant way in teacher training, nor are they contemplated in curricular structures or teacher training programs (Lozano-Peña et al., 2021), which leaves teachers poorly prepared to face the challenges involved in their daily work, impacting aspects such as their performance and professional trajectory, the quality of relationships, and classroom climate (Jara-Coatt et al., 2025; Mouw et al., 2020; Sáez-Delgado et al., 2023).

The question this study examines is the following: Which digital technologies have been implemented to support the development of teachers’ SECs in educational contexts and what are their results? The contribution of this research lies in its teacher-centered approach and in systematically gathering SECs that are strengthened by the use of technology. In addition, it offers recommendations that can guide future interventions or teacher training strategies in this field.

2. Materials and Methods

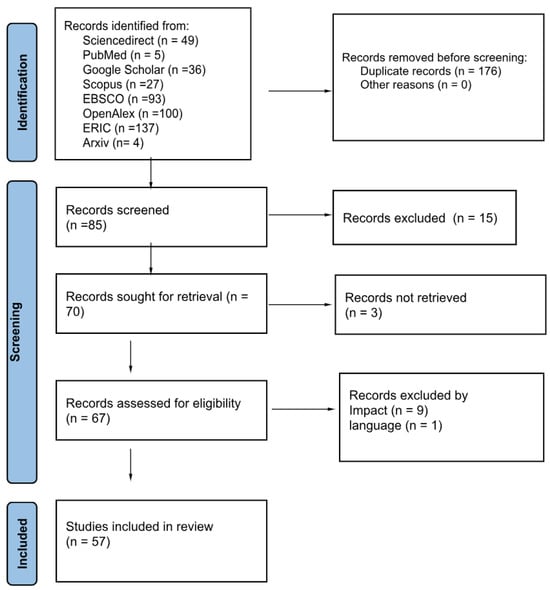

This review follows the guidelines of the PRISMA 2020 statement (Page et al., 2021) for research synthesis and analysis. With a window of observation open to any year of publication, it includes studies in English or Spanish, published in peer-reviewed academic journals. Studies that do not address how technology contributes to strengthening teachers’ socioemotional support were excluded from the analysis. Theoretical research was also eliminated. The ERIC, Academic Search Complete (EBSCO), OpenAlex, Sciencedirect, Scopus, PubMed, arXiv, and Google Scholar databases were used as data sources. The review contemplated the phases of identification, selection (screening), and inclusion, and all artifacts generated were registered in a public repository in the figshare platform (Sáez-Delgado et al., 2025). The review contemplated the phases of identification, selection (screening), and inclusion, and all artifacts generated were registered in a public repository on the figshare platform (Sáez-Delgado et al., 2025).

2.1. Identification Phase

In this phase, the search strategy was defined based on the research question (What digital technologies have been implemented to support the socioemotional development of teachers in educational environments and what are their results?), identifying key words and phrases in English and Spanish, according to the categories or groups of words related to (a) socioemotional competencies, (b) teachers, (c) technologies (See Table 1).

Table 1.

Search algorithm.

The search algorithm was constructed by associating these key words and phrases, adjusted according to each search engine and language (English and Spanish). The search was performed automatically by means of a Python 3.13.7 programming language script in the different academic engines, using filters by title and abstract, and excluding citations to optimize the relevance of the results.

Data Collection Process

The search sentences and their variations were entered into the platforms of the information sources. The initial search date was 25 May 2025, and the last date was 12 June 2025. Access to EBSCO, Sciencedirect, and Scopus was through the institutional subscription of the University associated with the affiliation of the authors of this study.

2.2. Selection of Studies

The selection of articles was a semi-supervised three-stage process.

2.2.1. Identification Phase

In the first phase, searches were carried out in the different search engines, obtaining a preliminary list of 451 records, which were imported into the Rayyan application that allowed the automatic identification of 176 duplicate studies, which were evaluated with this tool, discarding 116 records (See Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Diagram of systematic review results. Source: authors.

2.2.2. Selection Phase

The second stage began with the analysis of 335 abstracts, which were assigned to two researchers via the Rayyan tool. Of these, 250 studies were excluded due to their limited relevance to the objective of the systematic review and the predefined categories designed to address the research question. Eighty-five studies were identified, to which the inclusion criteria were applied as follows: (a) empirical studies; (b) studies written in Spanish, English, or Portuguese; (c) studies focused on teachers; and (d) studies addressing the topic of SECs in conjunction with technologies. The following exclusion criteria were then applied as follows: (a) studies that did not provide a detailed description of the technology used (7 studies excluded); (b) studies that were highly similar to prior research by the same authors (8 studies excluded); and (c) studies with restricted access and/or high cost (over USD 30) (3 studies excluded). The remaining 67 articles were randomly assigned to two researchers for content evaluation, and two additional exclusion criteria were applied as follows: (d) studies that did not explain how the technology contributes to enhancing teachers’ socioemotional support, i.e., due to “Impact” (9 studies excluded), and (e) studies written in languages other than those specified in the inclusion criteria, i.e., due to “Language” (1 study in Russian excluded).

To ensure rigor in the study selection and categorization process, we implemented a systematic coding procedure. First, two independent reviewers coded the records based on predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria, as well as the categorization scheme developed for this review. Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion with a third independent reviewer, who acted as an adjudicator to reach consensus. This procedure strengthened the validity and transparency of the study selection and categorization process.

2.2.3. Inclusion Phase

The last phase consisted of tabulating the results and generating master tables for the 57 studies included in the review. To facilitate the work, the tables were placed in the public access repository (Sáez-Delgado et al., 2025). The master tables developed were as follows:

General descriptive data include study data such as title, objective, author(s), year, country of publication, type of study, and limitations. They also specify the academic level where it was developed, number of participating teachers, and professional stage of the teachers.

Specific data include the following:

- Technology: Details what type of digital technology was used in each study, its specific purpose, and how it was designed or applied to support the development of teachers’ socioemotional competencies.

- Competencies: Relates the type of socioemotional skills promoted by the application of digital technologies for each study according to the CASEL model.

- Impact: Relates the main effects observed in the development of teachers’ SECs and the recommendations proposed for future research.

- Statistics: Includes absolute and relative frequencies of the different general and specific data, in order to recognize patterns in the data and understand the context, diversity, and focus of the research included.

3. Results

The following sections present a synthesis of the general and specific aspects of the studies selected for this systematic review. To facilitate the identification of the records, each of the studies was assigned a unique code (ID), which is listed in the different master tables of the public access repository of this research (Sáez-Delgado et al., 2025).

3.1. General Aspects

3.1.1. Year of Publication and Geographical Location

A total 74% of the 57 studies selected in this review were published from the year 2020, after the COVID-19 pandemic (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Year of publication of studies.

Most of the studies come from Europe (42%), with Germany, the Netherlands, Turkey, and England being the most representative countries. This is followed by North America with 28%, with research conducted in the United States and, to a lesser extent, Canada. Asia accounts for 23% of the total, with studies mainly in countries such as Indonesia, India, Kazakhstan, China, and Singapore. Africa contributes 7%, with studies conducted in Nigeria, Egypt, and South Africa. Latin America has a 5% share, represented by studies in Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru. Finally, Oceania contributes 2%, with one study conducted in Australia (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Geographical distribution of studies.

3.1.2. Types of Studies

Quantitative studies were the most frequent in this review, with 25 investigations (44%) employing experimental, correlational, pre–post, or comparative cross-sectional designs. This was followed by mixed studies combining qualitative and quantitative approaches, with 30% (17 studies), and finally qualitative studies represented 26% (15 studies), including designs such as case studies, phenomenography, ethnography, or empirical validation processes (See Table 4).

Table 4.

Types of studies.

3.1.3. Educational Level of Performance of Study Participants

Regarding the educational context in which study participants perform, 20 studies (35%) correspond to university level, 33 studies (58%) to primary and secondary level, and 4 studies (7%) address transversal or unspecified contexts. (See Table 5).

Table 5.

Academic level.

Of the 57 studies analyzed, 28 studies (49%) focused on teachers in training with an approximate participation of 2200 teachers in the different investigations and 29 studies (51%) on practicing teachers involving about 3000 participants (see Table 6).

Table 6.

Teaching stage.

3.1.4. Limitations Stated by the Authors of the Studies

Among the 57 studies reviewed, methodological limitations were identified. The most frequent was the use of small or specific samples, present in 54% of the studies. Next was the lack of generalizability or external validity, reported in 53% of the cases. Other limitations reported included the absence of quantitative data or longitudinal follow-up (37%) and the use of self-reports or subjective perceptions (35%). We also identified studies developed in limited contexts, whether geographical, cultural, or institutional (32%), and finally, 19% of the studies employed technologies that were still experimental or in the development phase (See Table 7).

Table 7.

Limitations stated in the studies.

3.2. Specific Information

3.2.1. Digital Technologies

Haleem et al. (2022) suggest that digital technologies that support the development of teacher socioemotional skills can be grouped into three types: digital self-reflection tools, which allow teachers to think about their emotions and experiences; collaborative professional learning platforms, which favor accompaniment and exchange among colleagues; and intentional emotional development technologies, designed to directly train skills such as empathy, self-regulation, and stress management.

Intentional Emotional Development Technologies

In this systematic review, 39 studies (68%) used intentional emotional development technologies. These included virtual reality environments, digital platforms, mindfulness applications, gamified platforms, virtual agents with artificial intelligence, emotional feedback tools, and educational simulation technologies (see Table 8).

Table 8.

Digital technologies used in studies.

Studies by Mouw et al. (2020), Dai et al. (2024), Ong et al. (2024), Ye et al. (2023), and Tettegah et al. (2006) used immersive technologies such as virtual reality (VR), mixed reality, and 360° video that facilitate the simulation of complex school situations in which the teacher can rehearse strategy and explore their emotional reactions of classroom management.

These technologies strengthen resilience, self-efficacy, and emotional regulation by enabling controlled and reflective experiences.

The use of digital platforms and collaborative tools, as proposed by Halder (2022), Ingram et al. (2024), Dantes et al. (2024), Cavioni et al. (2024), Cartagena et al. (2024), and Teng and Allen (2005), highlight the role of Moodle, asynchronous forums, videoconferences, collective diaries, and blogs for emotional support, self-reflection, and strengthening the sense of community.

The studies of this group include the use of technologies based on artificial intelligence that make it possible to automate repetitive tasks, offer personalized feedback, and support educational planning. Tools such as ChatGPT (version GPT-5) (Hashem et al., 2023; Hou et al., 2024; Kopuz, 2024), AI-enabled gamified platforms such as SofIA (Näykki et al., 2022; Reupert & Dalgarno, 2011), conversational chatbots (Dueck et al., 2024; Lee et al., 2025), and emotion analysis systems such as Engage AI (version 1.0.2) (Stairs et al., 2021) or AffectToolbox (academic release arXiv:2402.15195) (Bhuvaneshwara et al., 2025) present their usefulness in reducing workload, facilitating emotional feedback and encouraging teacher reflection on their socioemotional impact.

Studies by Halder (2022), Hou et al. (2024), Lee et al. (2025), and Stairs et al. (2021) used empathic virtual agents, digital feedback systems, and facial or voice recognition technologies to provide tailored emotional accompaniment and strengthen teacher self-regulation. Dueck et al. (2024) also applied chatbots with conversational AI as a form of affective containment, while Ingram et al. (2024) proposed personalized video feedback strategies focused on empathy and social presence.

Gamification along with the use of multimedia resources also played an important role. Interactive simulators and digital games were employed to foster emotional expression, the exploration of educational scenarios, and teacher community building (Näykki et al., 2022; Overdiep & Koffeman, 2025; Reupert & Dalgarno, 2011). Meanwhile, Chan et al. and Tolbert used motivational videos, simulations, and gamified environments to promote resilience, emotional connection, and active participation in educational contexts (Chan et al., 2024; Tolbert, 2008).

Finally, studies such as those by Flook et al., Suganda et al., and Andersson and Manning et al. present mobile application technologies and mindfulness platforms such as Calm, Headspace, or mMBSR, which are aimed at reducing stress, improving sleep, and promoting mindfulness and teaching self-compassion, facilitating sustainable and accessible self-care practice in the professional environment (Andersson, 2020; Flook et al., 2013; Manning et al., 2020; Suganda et al., 2022).

Digital Self-Reflection Tools

A total of 37 studies (65%) included in this review incorporate digital tools for self-reflection. These technologies encompass resources such as reflection journals, learning platforms (Moodle, Padlet, Blackboard), generative artificial intelligence applications (ChatGPT), video analysis, digital narratives, podcasts, blogs, emotional dashboards, and virtual simulators such as OpenSimulator (See Table 8).

For example, Reupert and Dalgarno’s study encouraged digital self-reflection by designing activities accompanied by podcasts, videos, infographics as triggers for teachers to reflect on their own emotional responses to moral dilemmas, or problematic or complex school situations (Reupert & Dalgarno, 2011). Similarly, Näykki et al. integrate accessible digital resources to stimulate emotional awareness and guided reflection (Näykki et al., 2022). Varanasi et al., supported with the Chat-GPT tool, found a guided reflection where teachers interact to review their pedagogical practices and express emotions in order to deepen their understanding of their professional decisions (Varanasi et al., 2024). AI is used as a vehicle for critical and emotional thinking that achieves self-reflection through questions, reformulations of texts, and textual feedback.

On the other hand, with the support of Artificial Intelligence technology, the study by Hou et al. (2024) proposed a combined model of GPT-4 and multilayer perceptrons (MLP) for reading teaching transcripts and an automated diagnosis of socioemotional dimensions such as warmth and encouragement. This architecture was able to more accurately identify levels of emotional competence from actual verbal productions.

Likewise, technologies oriented to structured self-reflection, such as emotional diaries and self-reflection rubrics (Dantes et al., 2024; Mukhametzhanova & Естаева, 2025; Romano & Schwartz, 2005; Weber et al., 2018), allow teachers to reflect on the emotional experiences they have worked on and evaluate their personal and professional growth, favoring self-awareness and supporting individual and collective emotional self-regulation processes.

Other important research studies are those by Dantes et al. (2024) and Cavioni et al. (2024), who used digital diaries as a means to promote emotional self-reflection, teacher self-regulation, and the construction of a common professional identity. These platforms served as spaces for expressing experiences, recognizing common emotions, and enriching teachers’ SECs.

Finally, the work of Weber et al. (2018) used reflective blogs and collaborative platforms as means to promote affective dialog, critical observation, and the consolidation of reflective professional communities.

Collaborative Professional Learning Platforms (PLCs)

A total of 21 studies (37%) applied this type of technology, using tools such as WhatsApp, Zoom, Google Meet, Moodle, social networks, online forums, LMS platforms, and digital collaborative environments (see Table 8).

Studies by Cansoy (2017) and Latif and Shehata (2024), highlight that the use of WhatsApp and Zoom allow teachers to exchange experiences, receive emotional support, and develop their practice as professionals in synchronous or asynchronous environments. Chan et al. (2024) complement this view by showing how virtual forums foster emotional accompaniment and a sense of community among peers.

Similarly, research by Dantes et al. (2024), Cavioni et al. (2024), and Teng and Allen (2005) has shown that the use of Moodle, virtual communities of practice, and asynchronous forums favors collaborative learning, emotional dialog, and shared professional reflection.

Research by Nacimba Rivera et al. (2024) and Wetcho and Na-Songkhla (2022) also highlighted how social networks, asynchronous multimedia comments, and collaborative tools allow teachers to share their experiences, stay connected, and accompany each other emotionally in digital contexts, promoting peer support.

Likewise, research by Ingram et al. (2024) and Romano and Schwartz (2005) show how asynchronous forums strengthen social interaction, personal expression, and the development of communities of practice that contribute to teachers’ emotional and professional well-being. Moreover, studies by Boyarintseva et al. (2025) and Tolbert (2008) have documented the implementation of wikis, e-mails, and peer-to-peer forums in the development of empathy, belonging, and emotional expression in teaching communities of practice.

3.2.2. SECs

SECs in teachers can be classified using the CASEL model (Corcoran & Tormey, 2012; Lozano-Peña et al., 2021), which contemplates five dimensions: self-awareness, understood as the ability to recognize one’s own emotions, values, and strengths; self-regulation, which involves managing emotions, impulses, and behaviors; social awareness, associated with empathy and understanding of diverse contexts; relational skills, which promote the creation of positive and collaborative bonds; and responsible decision-making, which consists of acting based on ethical standards and a conscious evaluation of consequences (see Table 9).

Table 9.

SECs identified in the studies.

The results show that teachers’ self-awareness was fostered in 49 of the studies analyzed (86%), supported by tools such as artificial intelligence, virtual reality, immersive simulations, and social networks. These technologies made it easier for teachers to identify their emotions, recognize their strengths, and critically reflect on their professional role. For example, studies by Nacimba Rivera et al. (2024) and Mouw et al. (2020) assert that digital platforms and virtual environments promoted reflection on emotions such as stress, anxiety, and surprise, increasing awareness of their own personal reactions and skills. Similarly, studies by Wetcho and Na-Songkhla (2022) and Cavioni et al. (2024) highlighted how simulations and immersive experiences in virtual reality favor processes related to emotional introspection and the identification of teaching strengths.

The use of emotional diaries, video analysis, digital coaching, or emotional feedback, as evidenced by the work of Mukhametzhanova and Естаева (2025), Russell and Smyth (2023), and Näykki et al. (2022), promoted self-evaluation processes where teachers could observe, analyze, and recognize themselves emotionally.

Self-regulation was considered in 81% of the research selected for this study, suggesting that digital tools helped teachers in stress management, management of negative emotions, and emotional adaptation to difficult situations. Emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence, virtual reality, gamified spaces, or even social networks offered a safe space to practice emotional regulation strategies, develop impulse control, and strengthen teacher resilience. Nacimba Rivera et al. (2024) and Mouw et al. (2020) identified that tools such as MagicSchool AI or virtual reality offered teachers the possibility to reduce their emotional load and rehearse responses to stressful situations without real consequences. Other studies, such as those by Wetcho and Na-Songkhla (2022) and Näykki et al. (2022), supported that immersive simulations and emotional feedbacks in interactive environments offered an opportunity for educational practice oriented to the development of self-regulation.

At the same time, methodologies such as reflective blogging (Reupert & Dalgarno, 2011), mindfulness supported by virtual reality (Ong et al., 2024), and personal video review (Dai et al., 2024) also offered self-regulation-oriented modes of teaching practice. Complementarily, studies such as those by Kopuz (2024) and Hashem et al. (2023) highlighted that the use of ChatGPT enabled teachers to manage work overload, manage their time, and reduce stress, promoting better emotional control.

On the other hand, research by Andersson (2020) and Chan et al. (2024) showed how the use of mindfulness applications, emotional tracking technologies, or collaborative digital spaces helped to strengthen teacher self-regulation, offering strategies to stay calm and maintain motivation in demanding contexts.

Social awareness was promoted in 33 of the studies analyzed (58%). Digital technologies helped teachers to develop skills such as empathy and sensitivity to the emotions and needs of others. Technological tools such as virtual reality simulations, artificial intelligence, social networks, or gamified game environments allowed teachers to experience diverse educational and cultural realities. Studies by Wetcho and Na-Songkhla (2022) and Ye et al. (2023) show that the use of simulated characters and virtual students helped to recognize others’ emotions and sensitive adaptation to various situations. In addition, research by Chehayeb et al. (2024), Bhuvaneshwara et al. (2025), and Mukhametzhanova and Естаева (2025) corroborate how teachers developed competencies such as empathy through role-playing, interaction in simulations showing the social norms shared by this practice, and the use of emotional feedback work adapted for each situation.

In relation to relational skills, 68% of the works analyzed (39 studies) report important advances in terms of communication, cooperation, and the creation of support networks between teachers and students. Digital technologies such as messaging platforms, simulations, blogs, forums, and collaborative environments offer spaces to practice active listening, empathetic expression, and teamwork. For example, the study by Tuyakova et al. (2020) showed that interactive educational technologies improve collaboration between colleagues and students. Something similar occurred in studies such as those by Wetcho and Na-Songkhla (2022), Chehayeb et al. (2024), and Varanasi et al. (2024) in which it was shown that the use of simulations and digital platforms favors the quality of dialog, conflict resolution, or the construction of more empathetic relationships. Also, studies by Cansoy (2017) or Reupert and Dalgarno (2011) showed how virtual communities, instant messaging groups, or collaborative environments foster the creation of bonds of trust and support between peers.

Finally, responsible decision-making was identified in 49 of the studies analyzed (86%). Many of these studies presented complex situations in simulated environments in tools such as virtual reality or gamified platforms, which allowed teachers to reflect critically, evaluate the logic of their decisions and act ethically and sensitively to the emotional needs of the educational context. For example, research by Dantes et al. (2024) and Boyarintseva et al. (2025) highlighted how future teachers have made pedagogical and ethical decisions when selecting content and designing applications, promoting values such as inclusion and tolerance. In studies such as those by Chehayeb et al. (2024) and Varanasi et al. (2024) participants face dilemmas in simulations similar to real situations in order to assess the consequences of their choices and respond sensitively to students with complex emotional needs. At the same time, studies such as those by Weber et al. (2018) and Overdiep and Koffeman (2025) indicate how teachers critically reflected on different possible future scenarios, learning to weigh options and consider their social, emotional, and professional implications.

4. Discussion

4.1. General Aspects

The studies that have been considered in the present systematic review evidence that the use of digital technology to promote the socioemotional development of teachers has been increasing after the pandemic, also coinciding with the emergence of emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence, virtual reality, and gamification (González Gutiérrez & González Gutiérrez, 2025). These have transformed education to improve the accessibility, quality, and effectiveness of learning (Salgado Reyes, 2023) and have made it possible to design environments that actively support the development of SECs in teachers such as emotional self-regulation, empathy, social awareness, and responsible decision-making (Goldoni et al., 2023).

Most of the studies were conducted in Europe, where there is good momentum to integrate technologies in education (García, 2023); however, there is little representation from Latin America, Africa, and Oceania, indicating that more research is needed in these regions to understand how these experiences are lived in different contexts, and in many cases, with fewer technological resources.

In terms of methods, we mainly used quantitative approaches that allowed us to analyze the impact of technologies and to evaluate specific variables related to teachers’ socioemotional competencies. Mixed studies were also identified that helped to combine the measurement of results with the understanding of the participants’ experiences. Qualitative studies were also found that allowed for a more in-depth exploration of teachers’ emotions and perceptions in different contexts. The studies included teachers both in their training stage and at the professional level, which is important because it allows us to see how these SECs develop at different times in the teacher’s life.

Finally, it should be noted that several studies have limitations such as the use of small samples or methodological limitations in their research designs and some focus on specific contexts such as a single group in a private school. These aspects should be improved in future research to make the results more useful and applicable.

4.2. Specific Aspects

The use of digital technologies such as artificial intelligence, virtual reality, social networks, or gamified platforms allows teachers to know themselves better, manage their emotions in adverse situations, and work more empathetically with their colleagues or students (Boyarintseva et al., 2025; Chehayeb et al., 2024; Kopuz, 2024; Nacimba Rivera et al., 2024). In addition, it facilitates them to make more conscious and ethical decisions, increase their adaptive capacity, and better manage the stress they experience on a daily basis (Agbatogun, 2010; Halder, 2022; Mouw et al., 2020; Mukhametzhanova & Естаева, 2025; Wetcho & Na-Songkhla, 2022). However, for these benefits to be consolidated, it is necessary to take into account the recommendations given by some authors to strengthen the different SECs needed by teachers.

In the case of teachers’ self-awareness competence, studies show that the occasional use of technologies is not enough. For these tools to really contribute to the development of this competence, they must be integrated into training programs that promote internal questioning, recognition of emotions, and critical reflection on teaching practice (Mukhametzhanova & Естаева, 2025; Tuyakova et al., 2020; Wetcho & Na-Songkhla, 2022). Technology should be combined with reflective mentoring, continuous feedback, and spaces for dialog about teaching practice (Chehayeb et al., 2024; Näykki et al., 2022; Reupert & Dalgarno, 2011).

Regarding self-regulation competence in teachers, studies highlight that digital technologies such as simulation platforms, digital portfolios, mindfulness apps, or guided yogic routines offer safe contexts for stress management, impulse control, and the channeling of difficult emotions (Bull-Beddows, 2020; Dai et al., 2024; Suganda et al., 2022; Wetcho & Na-Songkhla, 2022). However, for these skills to be consolidated, there needs to be continuous training to help bring these skills to the real classroom and to everyday situations of teaching practice. This implies integrating these technologies into professional development programs with reflective accompaniment, personalized tutoring, and long-term emotional follow-up. Therefore, it is important that these technologies are not only used in isolated activities but are part of a continuous process that accompanies teachers both in their training and in their daily practice (Hashem et al., 2023; Kopuz, 2024; Reupert & Dalgarno, 2011; TamilSelvi & Thangarajathi, 2011).

Regarding the development of relational skills, studies show that the use of collaborative virtual environments and messaging networks promotes active listening, respectful communication, and interpersonal bonding in teachers (Cansoy, 2017; Cartagena et al., 2024). However, the development of these skills requires that virtual environments incorporate elements intentionally designed to foster emotional engagement, mutual support, and conflict resolution (Chehayeb et al., 2024; Näykki et al., 2022).

Finally, responsible decision-making is recognized as a cross-cutting competency in teachers that articulates ethical judgment, understanding of emotions, and the ability to analyze professional situations critically (Boyarintseva et al., 2025; Dai et al., 2024; Dantes et al., 2024). However, it is necessary that digital technologies do not focus solely on providing correct or automatic answers but become spaces that invite teachers to face uncertainty, reflect, and develop a critical and active attitude in their pedagogical practice (Kopuz, 2024; Overdiep & Koffeman, 2025; Weber et al., 2018).

4.3. Discussion of Results

The evidence shows that the COVID-19 pandemic marked a turning point in the development of research integrating digital technologies in teacher education, especially in the socioemotional domain (Salamanca, 2023). The fact that 74% of the studies analyzed have been published since 2020 suggests an epistemological shift in which emotional training and teacher well-being have acquired an unprecedented centrality in the global educational agenda. This phenomenon can be interpreted both as a response to the health crisis, which made the emotional exhaustion of teachers visible, and as an opportunity to experiment with emerging technologies that, until then, had not been sufficiently explored in training contexts (Mérida López et al., 2020).

Likewise, the irruption of technologies, such as generative artificial intelligence, virtual reality, and emotional feedback systems, has catalyzed new forms of professional teacher learning, allowing for more personalized, immersive, and adaptive processes (Carrillo & Flores, 2020). In this context, the increase in research suggests a maturation of the field, although it also evidences the urgency of consolidating robust theoretical frameworks that guide a critical incorporation of these technologies (Palacios Ortega et al., 2022).

The geographical bias in the distribution of the included studies reveals a marked concentration of scientific production in Europe (42%), in contrast to the scarce representation of Latin America (5%). This asymmetry not only limits the contextual generalization of the findings, but also reproduces epistemic inequalities in the educational field, making training experiences in territories historically less represented in the academic literature invisible (Hernández et al., 2021).

The few studies from Latin America—located in Colombia, Peru, and Ecuador—show that there are relevant initiatives in the region, although these are scattered, poorly systematized, or present difficulties in international indexing. As warned by Hernández et al. (2021), the structural technological backwardness and access gaps hinder not only the implementation of digital technologies in teaching practice but also their research and publication in high-impact academic media. Hence the need to promote regional funding policies for applied research, strengthen collaborative networks, and ensure open access to publishing platforms as basic conditions for a more equitable participation in the construction of knowledge.

In methodological terms, the results reveal a predominance of the quantitative approach (44%), followed by mixed (30%) and qualitative (26%) designs. This pattern is understandable if one considers the need to measure concrete effects of technologies on emotional variables—such as stress levels, self-awareness, or empathy—by means of standardized instruments. However, this trend also implies a limitation: the reduction in the socioemotional phenomenon to operational constructs, which may make its experiential and contextual complexity invisible (Corcoran & Tormey, 2012)

In this scenario, mixed studies emerge as a valuable middle way, combining the explanatory power of quantitative data with the interpretative depth of qualitative techniques, such as interviews, reflective diaries, and digital narrative analysis (Hernández et al., 2021). It becomes imperative to foster more robust qualitative research that explores how teachers experience, re-signify, and appropriate technologies from their emotional, cultural, and professional trajectories.

One of the most relevant methodological weaknesses detected is the scarce implementation of controlled or longitudinal experimental designs. Most of the included studies adopt a cross-sectional or comparative approach, which makes it possible to establish associations but not causal inferences or analyses of effects sustained over time. This situation is consistent with previous findings in reviews on technologies in education, where economic, logistical, and ethical resources limit the use of experimental methodologies with teachers in real contexts (Tamim et al., 2011).

The absence of longitudinal follow-ups also prevents us from assessing the impact of digital technologies on the continuous development of socioemotional competencies, a key aspect for a sustainable transformation of teaching practices. It is therefore recommended that future research incorporate post-intervention follow-ups or quasi-experimental designs that allow us to determine whether the changes observed are transitory or permanent (Chua et al., 2024).

The results also show a higher concentration of studies at the elementary and middle school levels (58%), compared to the university level (35%). This distribution evidences that the concern for SECs is no longer limited to the field of initial teacher training but extends to professional practice in school contexts. The emphasis on these levels makes it possible to address the emotional demands of the classroom from a situated perspective, although it also reveals the need for greater systematization in university programs that train teachers with emotional preparation from the beginning of their careers (Martínez-Saura et al., 2024). Likewise, the few studies with unspecified contexts (7%) could miss the possibility of analyzing interinstitutional approaches, systemic policies, or comprehensive professional development programs.

The balance in the distribution between teachers in training (49%) and practicing teachers (51%) is particularly significant, as it allows us to observe differences in the appropriation and effects of technologies according to the professional trajectory. For example, studies with future teachers tend to focus on the training of skills such as emotional regulation or empathy in simulated scenarios (Jong et al., 2024), while those aimed at practicing teachers favor stress management, self-reflection on practice, and professional peer support. This finding suggests that technologies can be adapted to different moments in the teaching career, but also reinforces the need to design differentiated strategies, sensitive to the specific challenges of each group.

Among the most reported limitations are the use of small or specific samples (54%), the lack of generalization (53%), and the absence of longitudinal follow-up (37%). These methodological weaknesses are frequent in emerging studies that work with new technologies or populations that are difficult to access, such as in-service teachers.

The widespread use of self-reports or subjective perceptions (35%) should also be critically analyzed. Although these instruments allow capturing internal experiences, they may be biased by social desirability or a lack of deep self-reflection. In that sense, it is recommended to complement them with observational analyses, third-party evaluations, or objective digital metrics (Wettstein et al., 2021), such as emotional pattern analysis, automatic detection of affective tone, or visualization of emotional progress through dashboards.

The review shows that ICTs were mostly used to promote teacher self-reflection (65%) and intentional emotional development (68%). In contrast, only 37% of the studies explored their potential to foster collaborative professional learning. This finding suggests a tendency toward the individualization of socioemotional processes, focused on personal improvement rather than on the collective construction of teacher well-being.

While self-regulation and self-awareness are fundamental pillars of emotional competence, several studies argue that emotional accompaniment among peers, the generation of support networks, and collective reflection are equally determinant for the sustainability of teacher well-being (Acton & Glasgow, 2015; Cansoy, 2017). Therefore, it is necessary to balance individual strategies with collaborative pedagogical practices, such as virtual communities of practice, asynchronous affective forums, or platforms for co-creation of professional meaning (Ingram et al., 2024).

Finally, the analysis of the competencies worked on reveals a clear predominance of self-awareness (86%) and relational skills (68%), while social awareness appears less addressed (58%). This trend evidences a focus on strengthening the teaching self, emotional introspection, and direct interpersonal management. It also suggests a formative debt regarding the development of empathy towards otherness, the understanding of sociocultural contexts, and the promotion of social justice in the classroom. Social awareness, understood as the ability to recognize others’ perspectives, value diversity, and respond empathetically in complex scenarios, is fundamental for facing the current challenges of education in multicultural and unequal societies. In this sense, technology can offer valuable opportunities to experience other realities, but it needs to be pedagogically intentional to fulfill this purpose (Mutchima et al., 2025; Rambaree et al., 2023).

5. Limitations and Future Lines of Research

Regarding possible limitations, although several databases were consulted, there may be other relevant studies indexed in other databases that were not explored. Some articles were not accessible due to payment requirements. Although the search algorithm was validated, it is always possible that some construct or word that identifies key studies may have been left out. In particular, the term “technology” encompasses a very wide range of possible concepts, both hardware and software, some of which extend the use of technology to the use of processes, models, etc.; therefore, some concepts may have been left out of the search algorithm.

Considering the limitations of current studies, future lines of research can delve deeper into non-Western contexts, specifically in the use of digital technologies for socioemotional teacher development in underrepresented regions such as Latin America, Africa, and Oceania.

Also, studies are needed that go beyond isolated interventions with partial measurements. There is a need to design and validate teacher training programs that intentionally integrate technologies for human accompaniment, reflective tutoring, and long-term follow-up. Studies are also needed to evaluate the impact of interventions not only in the acquisition of competencies, but also in their transfer and real application in the classroom over time.

In terms of methodology, it is necessary to advance in research with larger and more representative samples to improve external validity. Likewise, using mixed methodological approaches with nested qualitative designs, which allow responding to the limitations of current dichotomous methodologies, and fill the gap associated with qualitative studies that delve into internal emotional aspects that are not captured by quantitative research, such as teachers’ perceptions and complex emotional processes. Future studies could also explore the use of digital tools to strengthen less explored socioemotional competencies, such as resilience, self-compassion, assertive communication, and conflict management, which were less represented in the studies found.

From the point of view of technological development, it is necessary to advance in the design of technologies with IAGen and virtual reality that favor critical reflection, ethical judgment, and responsible decision-making in critical and uncertain situations. Finally, research into the combination of different types of technologies to more effectively enhance the various SECs of the CASEL model would be beneficial.

6. Conclusions

Digital technologies such as artificial intelligence, virtual reality, or social networks have had a significant and positive impact on the development of socioemotional competencies in teachers, reflected in improved skills such as self-awareness, self-regulation, social awareness, relational skills, and responsible decision-making. These technologies have not only allowed teachers to recognize and manage their emotions, but also to strengthen empathy, improve their interpersonal relationships, and make more ethical and reflective pedagogical decisions.

Digital technologies have a high potential to strengthen the socioemotional well-being of teachers, provided that their integration is intentional and guided by a sound pedagogical approach. The studies reviewed agree that it is not enough to incorporate these tools in an isolated or technical way; it is necessary to include them systematically and continuously within teacher training processes. This implies accompanying them with strategies for critical reflection, ethical training, spaces for emotional dialog and institutional follow-up to ensure their long-term impact on the development of socioemotional competencies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.S.-D., P.C.-S. and J.M.-N.; methodology, F.S.-D., P.C.-S. and J.M.-N.; software, F.S.-D., P.C.-S. and J.M.-N.; validation, F.S.-D., Y.L.-A. and J.B.-F., formal analysis, F.S.-D., P.C.-S., J.M.-N. and C.C.-S.; investigation, F.S.-D., Y.L.-A., J.B.-F. and G.L.-P.; resources, F.S.-D. and Y.L.-A.; data curation, P.C.-S., J.B.-F., C.C.-S., G.L.-P.; writing—original draft preparation, F.S.-D., Y.L.-A., J.B.-F. and G.L.-P.; writing—review and editing, F.S.-D., J.B.-F., C.C.-S. and G.L.-P.; visualization, F.S.-D., P.C.-S. and J.M.-N.; supervision, F.S.-D., J.M.-N. and Y.L.-A.; project administration, F.S.-D., J.M.-N. and Y.L.-A.; funding acquisition, F.S.-D., J.M.-N. and Y.L.-A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Funding Regular Fondecyt Project No. 1241902 entitled “Promoting teacher thriving through the ProSEL-iT intervention based on virtual worlds with immersive experiences and its effect on socioemotional skills, resilience, and well-being,” from the Chilean National Research and Development Agency.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study is a theoretical review and does not involve work with humans or animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The research data were shared and are available in the supplementary material of Sáez-Delgado et al. (2025).

Acknowledgments

Research and innovation group in socioemotional learning, well-being, and mental health to foster thriving (Thrive4All), the Faculty of Education of the Universidad Católica de la Santísima Concepción, Chile.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Acton, R., & Glasgow, P. (2015). Teacher wellbeing in neoliberal contexts: A review of the literature. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 40(8), 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbatogun, A. O. (2010). Teachers’ management of stress using information and electronic technologies. Journal of Social Sciences, 24(1), 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, R. (2020). Effects of a mobile phone-based mindfulness intervention for teachers, and how mindfulness trait correlates with stress, wellbeing, burnout, and compassion [Master’s thesis, Halmstad University, School of Health and Welfare]. Available online: https://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:hh:diva-42864 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Bhuvaneshwara, C., Chehayeb, L., Haberl, A., Siedentopf, J., Gebhard, P., & Tsovaltzi, D. (2025). InCoRe—An interactive co-regulation model: Training teacher communication skills in demanding classroom situations. arXiv, arXiv:2502.20025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisquerra, R., & Pérez Escoda, N. (2007). Las competencias emocionales. Educación XX1, 10, 61–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyarintseva, N. A., Soboleva, E. V., Shilova, Z. V., & Shadrina, N. N. (2025). Peculiarities of organizing practical activities for designing didactic mobile applications to develop future teachers’ communicative tolerance. Perspectives of Science and Education, 2, 627–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull-Beddows, R. (2020). Exploring the mechanisms in which a digital mindfulness-based intervention can help reduce stress and burnout among teachers [Ph.D. thesis, University of Southampton]. Available online: https://eprints.soton.ac.uk/439321/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Cansoy, R. (2017). Teachers’ professional development: The case of WhatsApp. Journal of Education and Learning, 6(4), 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo, C., & Flores, M. A. (2020). COVID-19 and teacher education: A literature review of online teaching and learning practices. European Journal of Teacher Education, 43(4), 466–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartagena, M., Pedrera, M., Revuelta, F., & Soria, E. (2024). Management of religion teachers’ socioemotional competencies in information and communication technologies integration: A phenomenographic study. The Qualitative Report, 29(5), 1443–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CASEL. (2020). Fundamentals of SEL. CASEL. Available online: https://casel.org/fundamentals-of-sel/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Cavioni, V., Conte, E., & Ornaghi, V. (2024). Promoting teachers’ wellbeing through a serious game intervention: A qualitative exploration of teachers’ experiences. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1339242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, W. W. L., Wu, K. C., Li, S. X., Tsang, K. K. Y., Shum, K. K., Kwan, H. W., Su, M. R., & Lam, S. (2024). Mindfulness-based intervention for schoolteachers: Comparison of video-conferencing group with face-to-face group. Mindfulness, 15(9), 2291–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chehayeb, L., Bhuvaneshwara, C., Anglet, M., Hilpert, B., Meyer, A.-K., Tsovaltzi, D., Gebhard, P., Biermann, A., Auchtor, S., Lauinger, N., Knopf, J., Kaiser, A., Kersting, F., Mehlmann, G., Lingenfelser, F., & André, E. (2024). MITHOS: Interactive mixed reality training to support professional socio-emotional interactions at schools. arXiv, arXiv:2409.12968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, Y., Cooray, S., Cortes, J. P. F., Denny, P., Dupuch, S., Garbett, D. L., Nassani, A., Cao, J., Qiao, H., Reis, A., Reis, D., Scholl, P. M., Sridhar, P. K., Suriyaarachchi, H., Taimana, F., Tang, V., Weerasinghe, C., Wen, E., Wu, M., … Nanayakkara, S. (2024). Striving for authentic and sustained technology use in the classroom: Lessons learned from a longitudinal evaluation of a sensor-based science education platform. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 40(18), 5073–5086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collie, R. J. (2020). The development of social and emotional competence at school: An integrated model. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 44(1), 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collie, R. J., Shapka, J. D., Perry, N. E., & Martin, A. J. (2016). Teachers’ psychological functioning in the workplace: Exploring the roles of contextual beliefs, need satisfaction, and personal characteristics. Journal of Educational Psychology, 108(6), 788–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Concha-Herrera, V., Sáez-Delgado, F., Reynoso-González, O., & Mella-Norambuena, J. (2025). Psychological well-being and resilience in elementary school teachers: Correlation with age and differences according to sex and educational dependency in Chile. CienciaUAT, 20(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcoran, R. P., & Tormey, R. (2012). How emotionally intelligent are pre-service teachers? Teaching and Teacher Education, 28(5), 750–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, C.-P., Ke, F., Zhang, N., Southerland, S. A., Barrett, A., Bhowmik, S., West, L., & Yuan, X. (2024). Preservice teacher learning in virtual reality simulation with artificial intelligence-powered virtual students: Emotions and teacher talk patterns. Available online: https://repository.isls.org//handle/1/10616 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Dantes, G. R., Asril, N. M., Liem, A., Suwastini, N. K. A., Keng, S.-L., & Mahayanti, N. W. S. (2024). Brief mobile app–based mindfulness intervention for indonesian senior high school teachers: Protocol for a pilot randomized controlled trial. JMIR Research Protocols, 13(1), e56693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Torre Quispe, R. D. P. (2022). Trabajo colaborativo utilizando herramientas digitales en habilidades socioemocionales en estudiantes de secundaria. Ciencia Latina Revista Científica Multidisciplinar, 6(6), 4769–4789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Arenas, R., Delgado-Llerena, A. A., Farfán-Pimentel, J. F., Delgado-Corazao, N. S., Corazao-Marroquin, N., & Lizandro-Crispín, R. (2023). Emotional competencies, learning styles and academic performance in university students. Cypriot Journal of Educational Sciences, 18(2), 492–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dueck, B., Loucks, T., Pelletier, G., & Daniels, L. (2024). Reducing pre-service teachers’ public speaking anxiety through a virtual reality intervention. Journal of Student Research, 13(3), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durlak, J. A., Mahoney, J. L., & Boyle, A. E. (2022). What we know, and what we need to find out about universal, school-based social and emotional learning programs for children and adolescents: A review of meta-analyses and directions for future research. Psychological Bulletin, 148(11–12), 765–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, M., Zincs, J., Weissberg, R., Frey, K., Greenberg, M., Norris, H., Kessler, R., Schwab-Stone, M., & Shriver, T. (1997). Promoting social and emotional learning: Guidelines for educators. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. Available online: https://earlylearningfocus.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/promoting-social-and-emotional-learning-1.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Ferreira, M., Martinsone, B., & Talić, S. (2020). Promoting sustainable social emotional learning at school through relationship-centered learning environment, teaching methods and formative assessment. Journal of Teacher Education for Sustainability, 22(1), 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flook, L., Goldberg, S. B., Pinger, L., Bonus, K., & Davidson, R. J. (2013). Mindfulness for teachers: A pilot study to assess effects on stress, burnout, and teaching efficacy. Mind, Brain, and Education, 7(3), 182–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García, L. (2023). Diferencias clave en tecnología educativa: Europa vs. Asia. Available online: https://techevolucion.net/perspectivas-globales/perspectiva-global-tecnologia-educacion-comparacion-europa-asia/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Gebre, Z. A., Demissie, M. M., & Yimer, B. M. (2025). The impact of teacher socio-emotional competence on student engagement: A meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 16, 1526371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldoni, D., Reis, H. M., Carrascoso, M. M., & Jaques, P. A. (2023). Computational tools to teach and develop socio-emotional skills: A systematic mapping. International Journal of Learning Technology, 18(2), 207–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Gutiérrez, F. L., & González Gutiérrez, S. G. (2025). Transformación de la formación docente: Inteligencia artificial, realidad virtual y gamificación en la educación del futuro en México. Revista Científica Multidisciplinar SAGA, 2(1), 416–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J. J. (1998). The emerging field of emotion regulation: An integrative review. Review of General Psychology, 2(3), 271–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halder, S. (2022). SEL-E: Social and emotional learning intervention to enhance pre-service teachers’ empathy development in a technology-mediated learning space [Electronic Theses and Dissertations]. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12588/3692 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Haleem, A., Javaid, M., Qadri, M. A., & Suman, R. (2022). Understanding the role of digital technologies in education: A review. Sustainable Operations and Computers, 3, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdani, S. U., Zill-e-Huma, Warraitch, A., Suleman, N., Muzzafar, N., Minhas, F. A., Psych, F. R. C., Nizami, A. T., Sikander, S., F.C.P.S., Pringle, B., Hamoda, H. M., Wang, D., Rahman, A., & Wissow, L. S. (2021). Technology-assisted teachers’ training to promote socioemotional well-being of children in public schools in rural pakistan. Psychiatric Services, 72(1), 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashem, R., Ali, N., El Zein, F., Fidalgo, P., & Abu Khurma, O. S. (2023). AI to the rescue: Exploring the potential of ChatGPT as a teacher ally for workload relief and burnout prevention. Research and Practice in Technology Enhanced Learning, 19, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, R. M., Saavedra-López, M. A., Wong-Fajardo, E. M., Campos-Ugaz, O., Calle-Ramírez, X. M., & García-Pérez, M. V. (2021). Producción científica Iberoamericana sobre TIC en el contexto educativo. Propósitos y Representaciones, 9(3), e1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, R., Fütterer, T., Bühler, B., Bozkir, E., Gerjets, P., Trautwein, U., & Kasneci, E. (2024). Automated assessment of encouragement and warmth in classrooms leveraging multimodal emotional features and ChatGPT (Vol. 14829, pp. 60–74). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, K., Oyarzun, B., Maxwell, D., & Salas, S. (2024). The difference a three-minute video makes: Presence(s), satisfaction, and instructor-confidence in post-pandemic online teacher education. TechTrends, 68(4), 723–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jara-Coatt, P., Constenla-Nuñez, J., & Sáez-Delgado, F. (2025). Modelos de competencia socioemocional docente para la innovación educativa. Revista ESPACIOS, 46(03), 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, P. A., Doyle, S., Oh, Y., Rasheed, D., Frank, J. L., & Brown, J. L. (2019). Long-term impacts of the CARE program on teachers’ self-reported social and emotional competence and well-being. Journal of School Psychology, 76, 186–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jong, M., Zhai, X., & Chen, W. (2024). Innovative uses of technologies in science, mathematics and STEM education in K-12 contexts. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 22, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopuz, E. (2024). English language teachers’ insights on the influence of ChatGPT on professional well-being. Journal of Educational Studies and Multidisciplinary Approaches, 4(2), 138–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruty, K., Zdanevych, L., Desnova, I., Blashkova, O., & Zameliuk, M. (2024). The main trends in the formation of psychological competence in the process of teacher training. Academia, (35–36), 50–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, O. L. I. A., & Shehata, M. G. M. (2024). Using an online assessment-based program for developing faculty of education prospective teachers’ test-making skills and self-confidence. Journal of Research in Curriculum Instruction and Educational Technology, 10(1), 85–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S., Jeon, J., & Choe, H. (2025). Enhancing pre-service teachers’ global englishes awareness with technology: A focus on AI Chatbots in 3D metaverse environments. TESOL Quarterly, 59(1), 49–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., & Chang, P. (2024). Exploring EFL teachers’ emotional experiences and adaptive expertise in the context of AI advancements: A positive psychology perspective. System, 126, 103463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano-Peña, G., Sáez-Delgado, F., López-Angulo, Y., & Mella-Norambuena, J. (2021). Teachers’ social–emotional competence: History, concept, models, instruments, and recommendations for educational quality. Sustainability, 13(21), 2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, J. B., Blandford, A., Edbrooke-Childs, J., & Marshall, P. (2020). How contextual constraints shape midcareer high school teachers’ stress management and use of digital support tools: Qualitative study. JMIR Mental Health, 7(4), e15416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Saura, H. F., Calderón, A., & López, M. C. (2024). Programas de formación emocional inicial y permanente para docentes de Educación Infantil y Primaria: Una revisión sistemática. Revista Complutense de Educación, 35(1), 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mérida López, S., Extremera Pacheco, N., Quintana Orts, C., & Rey Peña, L. (2020). Sentir ilusión por el trabajo docente: Inteligencia emocional y el papel del afrontamiento resiliente en un estudio con profesorado de secundaria. Revista de Psicología y Educación, 15(1), 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouw, J., Fokkens-Bruinsma, M., & Verheij, G.-J. (2020). Using Virtual Reality to promote pre-service teachers’ classroom management skills and teacher resilience: A qualitative evaluation. Editorial Universitat Politècnica de València. Available online: https://riunet.upv.es/handle/10251/146103 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Mukhametzhanova, А. О., & Естаева, К. Р. (2025). Methods and technologies of pedagogical support in the development of the emotional intelligence of future primary school teachers. Bulletin of the Karaganda University Pedagogy Series, 30(117), 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutchima, P., Leelakitpaisarn, Y., Pijitkamnerd, B., Phiwma, N., & Pantrakool, S. (2025). The effect of metaverse technology on multicultural learning: Strengthening the social attitudes, cultural awareness and critical thinking skills of secondary school students. Journal of Education and E-Learning Research, 12(1), 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, F., Denk, A., Lubaway, E., Sälzer, C., Kozina, A., Perše, T. V., Rasmusson, M., Jugović, I., Nielsen, B. L., Rozman, M., Ojsteršek, A., & Jurko, S. (2020). Assessing social, emotional, and intercultural competences of students and school staff: A systematic literature review. Educational Research Review, 29, 100304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nacimba Rivera, N. O., Trávez Osorio, G. M., Moreno Corrales, A. S., & Zambrano, B. A. (2024). Evaluación cuantitativa y cualitativa del impacto de la inteligencia artificial en la satisfacción, eficacia, gestión del tiempo y reducción del estrés laboral en la jornada laboral docente ecuatoriana presencialmente o fuera del plantel. Explorador Digital, 8(3), 101–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Näykki, P., Laitinen-Väänänen, S., & Burns, E. (2022). Student teachers’ video-assisted collaborative reflections of socio-emotional experiences during teaching practicum. Frontiers in Education, 7, 846567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, J., Doshi, K., Chew, K. H., Tay, J. H. M., & Foo, J. J.-C. (2024). The effectiveness of immersive VR 360 mindfulness for the reduction of stress and burnout among teachers. Mental Health and Digital Technologies, 2(1), 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overdiep, C., & Koffeman, A. (2025). Changing teacher perspectives: Game-based scenario writing. Social Publishers Foundation. Available online: https://www.socialpublishersfoundation.org/knowledge_base/changing-teacher-perspectives-game-based-scenario-writing/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Page, M. J., Moher, D., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … McKenzie, J. E. (2021). PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios Ortega, A., Pascual López, V., & Moreno Mediavilla, D. (2022). El papel de las nuevas tecnologías en la educación STEM. Bordón. Revista de Pedagogía, 74(4), 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perikleous, L. (2024). You don’t go in their place’: Historical empathy in education. Revista de Historia, 31, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrides, K. V., & Furnham, A. (2001). Trait emotional intelligence: Psychometric investigation with reference to established trait taxonomies. European Journal of Personality, 15(6), 425–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambaree, K., Nässén, N., Holmberg, J., & Fransson, G. (2023). Enhancing cultural empathy in international social work education through virtual reality. Education Sciences, 13(5), 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reupert, A., & Dalgarno, B. (2011). Using online blogs to develop student teachers’ behaviour management approaches. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 36(5), 48–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, M., & Schwartz, J. (2005). Exploring technology as a tool for eliciting and encouraging beginning teacher reflection. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher, 5(2), 149–168. [Google Scholar]

- Roorda, D. L., Jak, S., Zee, M., Oort, F. J., & Koomen, H. M. Y. (2017). Affective teacher–student relationships and students’ engagement and achievement: A meta-analytic update and test of the mediating role of engagement. School Psychology Review, 46(3), 239–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, A., & Smyth, S. (2023). Using a 10-day mindfulness-based app intervention to reduce burnout in special educators. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 23(4), 278–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamanca, M. (2023). Experiencias pedagógicas de docentes de educación básica y media en el marco del confinamiento por pandemia COVID-19. Educación y Ciencia, 27, e16278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgado Reyes, N. (2023). Evolución de la educación y las aplicaciones tecnologías. Polo del Conocimiento: Revista Científico—Profesional, 8(4), 1319–1328. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=9152237 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Salovey, P., & Mayer, J. D. (1989). Emotional intelligence. Imagination, Cognition and Personality, 9(3), 185–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarpong, R. (2025, February 4–5). Physical, social and emotional wellbeing of teachers: A concern of the future teacher education. National Seminar on Futuristic Teacher Education by 2050 (pp. 1–8), Vadodara, India. [Google Scholar]

- Sáez-Delgado, F., Coronado-Sánchez, P. C., López-Angulo, Y., Brieba-Fuenzalida, J., Mella-Norambuena, J., & Contreras-Saavedra, C. (2025). Master table of the systematic review on the use of technologies for teacher social-emotional support. Available online: https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/Master_table_of_the_systematic_review_on_the_use_of_technologies_for_teacher_social-emotional_support/29821148/3?file=56887490 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Sáez-Delgado, F., López-Angulo, Y., Mella-Norambuena, J., Hartley, K., & Sepúlveda, F. (2023). Mental health in school teachers: An explanatory model with emotional intelligence and coping strategies. Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology, 21(61), 559–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáez-Delgado, F., Mella-Norambuena, J., & López-Angulo, Y. (2024). Psychometric properties of the SocioEmotional skills instrument for teachers using network approach: English and Spanish version. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1421164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schonert-Reichl, K. A. (2019). Advancements in the landscape of social and emotional learning and emerging topics on the horizon. Educational Psychologist, 54(3), 222–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoon, I., & Lyons-Amos, M. (2017). A socio-ecological model of agency: The role of psycho-social and socioeconomic resources in shaping education and employment transitions in England. Longitudinal and Life Course Studies, 8(1), 35–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, S. S., & Jain, K. (2024). AI technologies for social emotional learning: Recent research and future directions. Journal of Research in Innovative Teaching & Learning, 17(2), 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slovák, P., & Fitzpatrick, G. (2015). Teaching and developing social and emotional skills with technology. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction, 22(4), 19:1–19:34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stairs, J., Mangla, R., Chaudhery, M., Singh Chandhok, J., & Timorabadi, H. S. (2021, July 26–29). Engage AI: Leveraging video analytics for instructor-class awareness in virtual classroom settings. 2021 ASEE Annual Conference Content Access (pp. 1–13), Virtual. [Google Scholar]

- Suganda, L. A., Zuraida, Z., Petrus, I., & Fiftinova, F. (2022). Pre-service teahers’ use of mobile-based mindfulness practices during COVID-19 pandemic era. Jurnal Pendidikan Bahasa Dan Sastra, 22(2), 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]