Advancing Quality Physical Education: From the Canadian PHE Competencies to the QPE Foundations and Outcomes Frameworks

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework: The Development of the Canadian PHE Competencies

3. Results

3.1. Elements of the Canadian Physical and Health Education Competencies

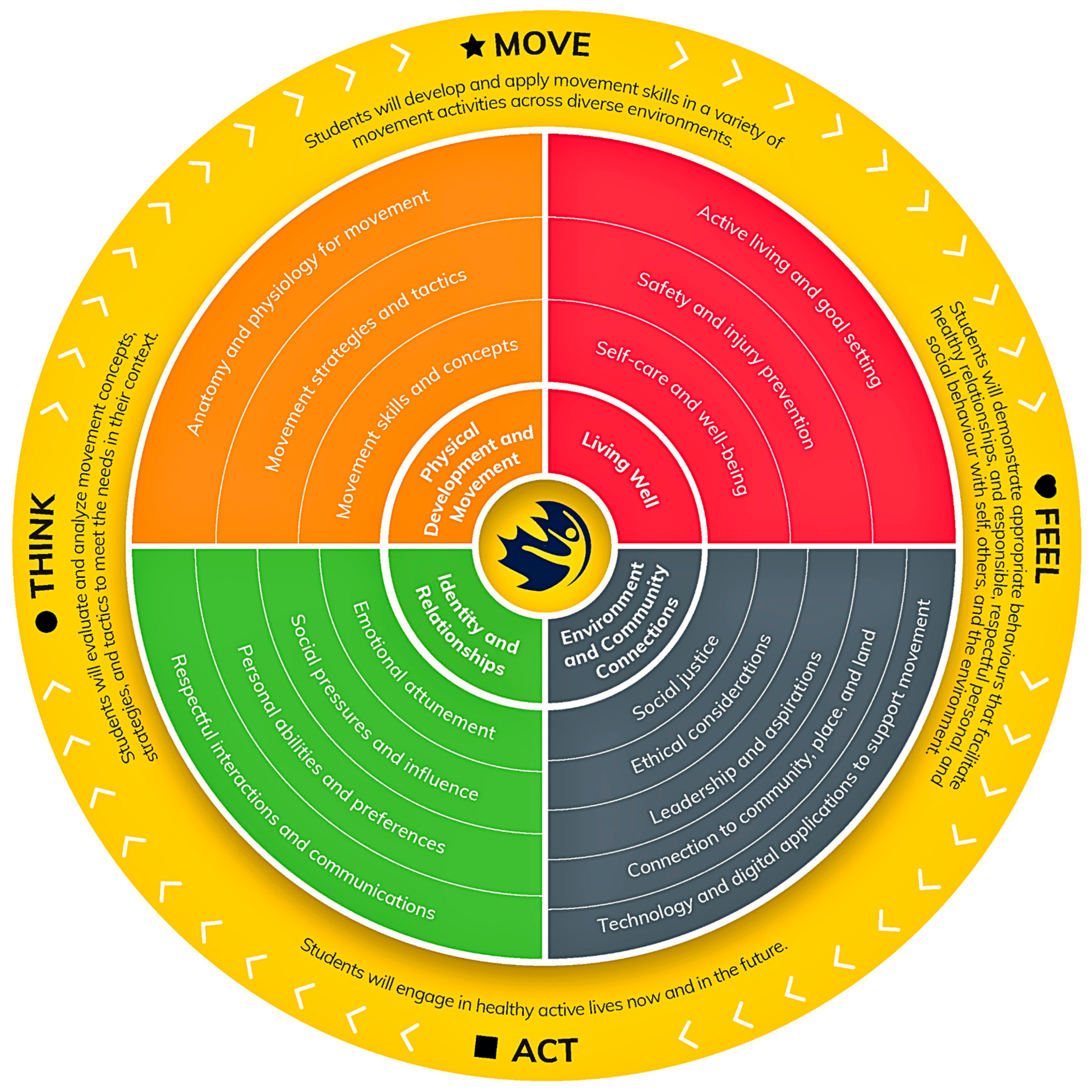

3.2. PE Competencies Wheel: A Tool for Quality Physical Education Instruction

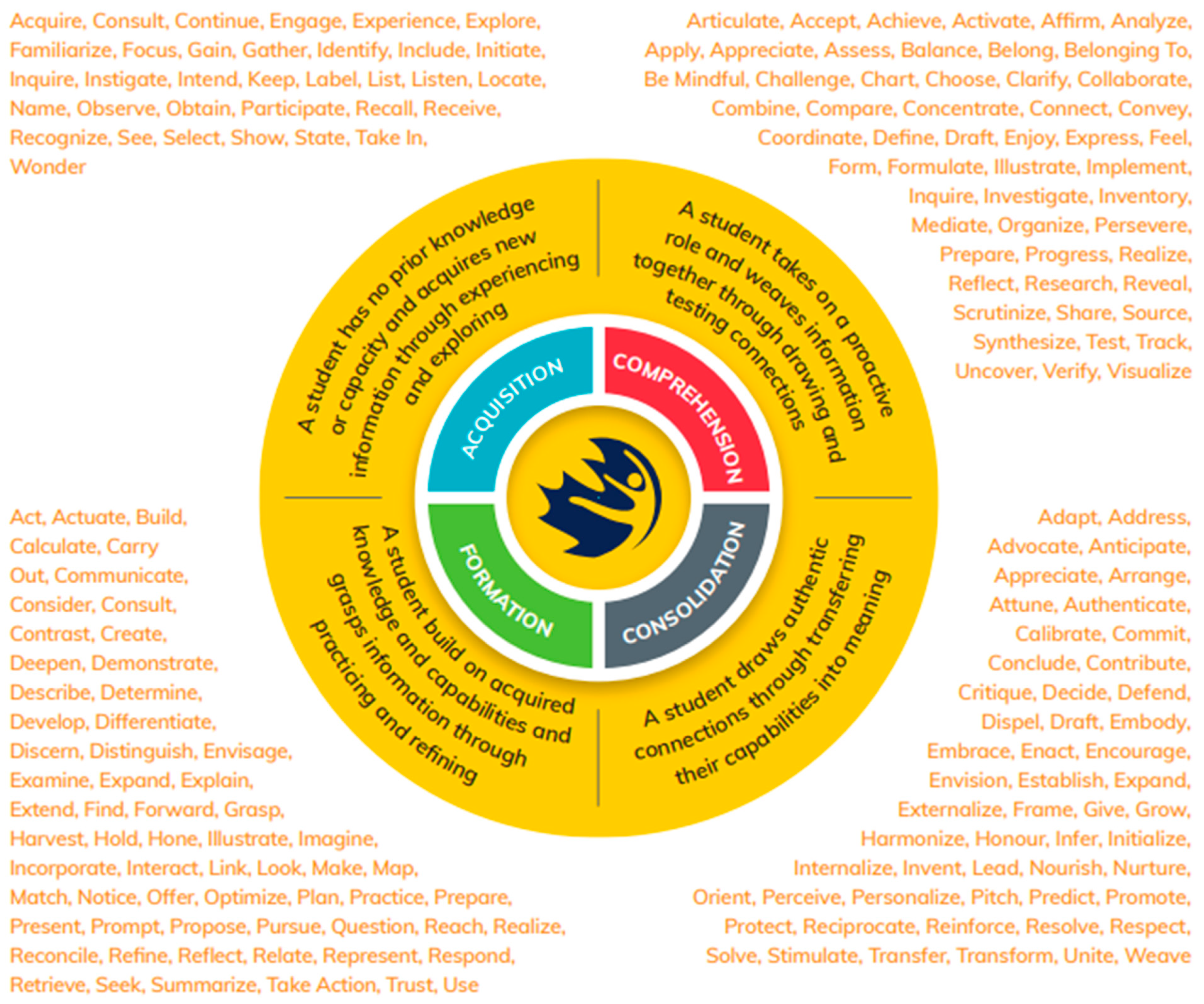

3.3. The Wholistic Verb Wheel: Four Stages of Continuous Learning

3.4. The Quality Physical Education Frameworks: Foundations & Outcomes

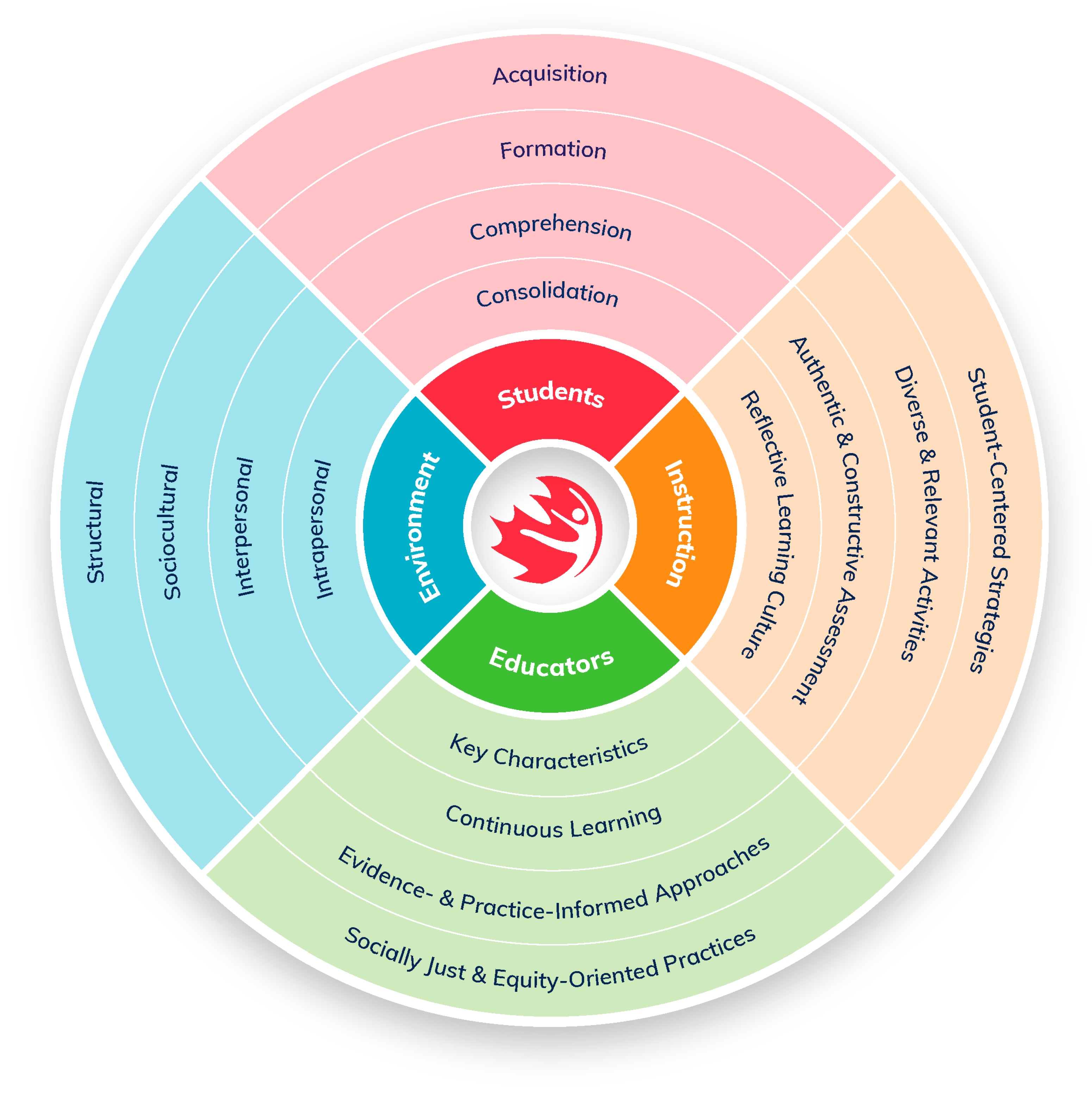

3.4.1. Part One: Quality Physical Education Foundations Framework

3.4.2. Part Two: QPE Outcomes Framework—Skills for Life

4. Discussion

“Quality Physical Education extends beyond just movement—it considers the many ways children and youth can think, feel, and act through movement. Quality Physical Education utilizes student voice and choice to guide instruction and the shape of the physical and social environments, allowing students to see themselves and their unique backgrounds, experiences, abilities, and identities reflected in their learning. By integrating student-centered approaches and socially just, equity-oriented, and culturally responsive practices into curriculum, Quality Physical Education creates spaces where every student can feel affirmed, challenged, engaged, safe, supported, and welcomed. The essential and foundational elements of the Canadian Physical and Health Education Competencies provide meaningful and progressive possibilities for making learning trajectories in Quality Physical Education personalized, relevant, responsive, and dynamic by honoring children and youth’s spirit and sense of self, and centering their physical, cognitive, social, and emotional development. Through this lens, students in K–12 Physical Education receive quality movement and learning opportunities for experiencing joy through movement and living well; instilling agency and ownership; developing skills and life competencies; understanding self, others, and the world; connecting to community, place, and land; attuning a sense of resiliency; engaging as socially just community members; and, nurturing empathy and respectful relationships. In essence, Quality Physical Education acknowledges the full spectrum of abilities, stages, and learning styles; values the process of skill development rather than specific, immediate outcomes; and provides students with multiple entry points to build foundational movement competencies. Through this approach, Quality Physical Education cultivates safer, inclusive, accessible, and fun learning environments where every student’s wholistic well-being and commitment to being active and living well—for life—are fostered. It is this framework that supports children and youth with understanding how to think, feel, and act through movement, helping them build the confidence, competence, and capacity for enjoying and valuing movement and living well, which in turn paves the way for their personal and vocational growth as they transition into adulthood.”

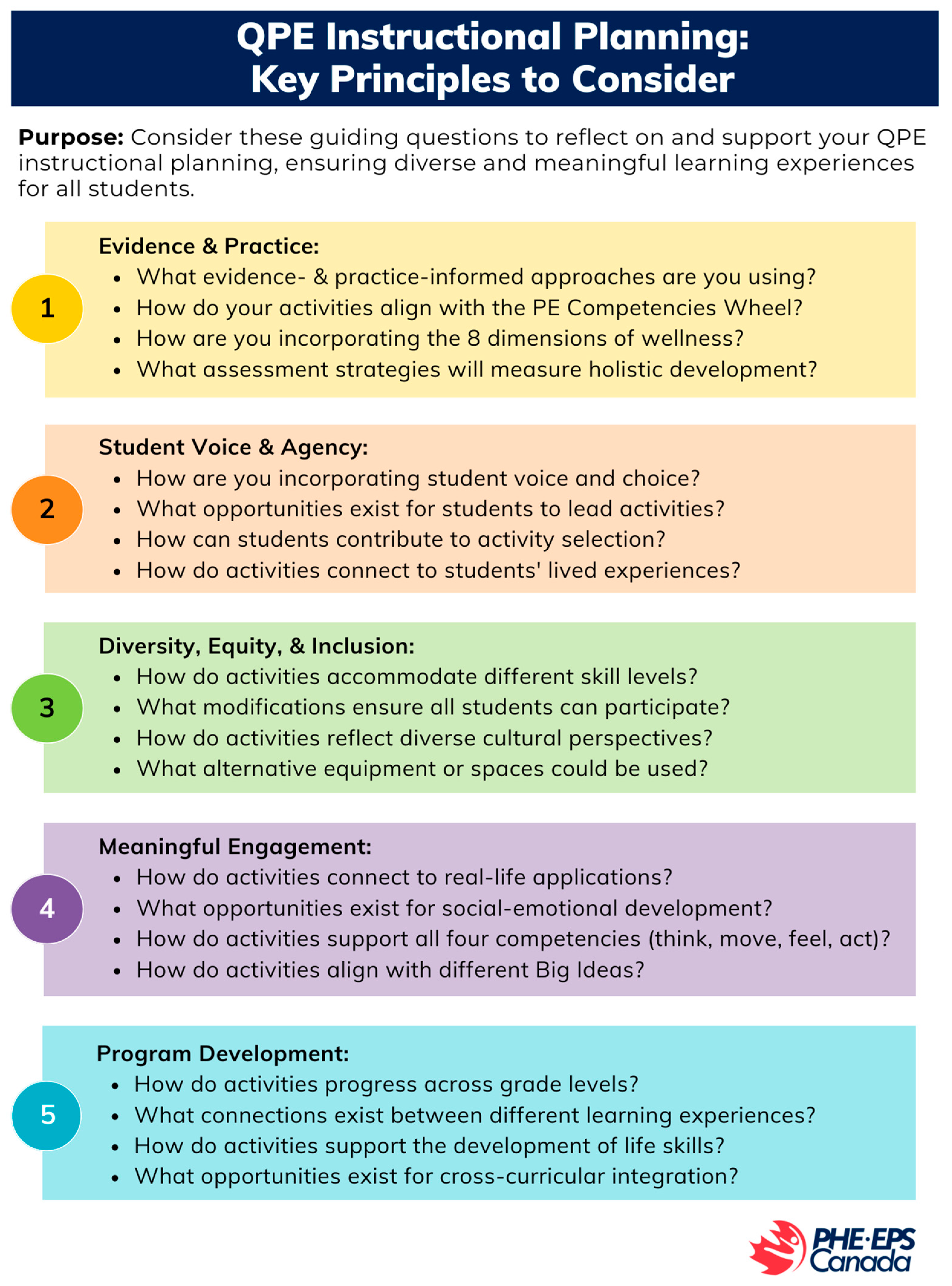

4.1. The PE Competencies Wheel: Supporting Educators Curriculum Delivery

4.2. The Wholistic Verb Wheel: A Student-Centered Assessment Tool

4.3. The Development of the Two-Part QPE Framework—Foundations & Outcomes: Inspiring Critical Reflective Thinking of PE Pedagogy

- Comprising well-planned and sequential learning opportunities that lead to the acquisition of information, skills and knowledge to lead active, healthy lives;

- engaging, meaningful, enduring, and developmentally appropriate;

- inclusive, and centered on diverse student experiences, intersectionalities, characteristics, motivations and interests;

- centered on respect for the whole self, others and the environment;

- focusing on a student-centered process of learning and growth;

- anchored in evidence and practice-informed approaches, pedagogies, and assessments; and,

- empowering students to make confident decisions, apply skills and take action to live well.

4.3.1. Exploring the QPE Foundations Framework: The Structures, Purpose, and Impact

- The “Student” section and the four sub-components reflect the four stages of learning from the Wholistic Verb Wheel (Figure 2)—Acquisition, Formation, Comprehension, and Consolidation. These four interconnect stages focus on a continuous and wholistic approach to learning which can serve as a dynamic compass for PE educators when implementing strength-based instruction and assessment. For example, the four stages honour and prioritize learning processes and skill development over the final destination or outcome. In QPE settings, educators are not assessing the results; they are assessing the process, providing instruction (e.g., cues) along the way and modifying their instruction (e.g., cues) as necessary so the student’s process is done correctly which then leads to the correct result. Learning is not linear. And, as students encounter new or familiar movement challenges and experiences, they may move fluidly between various learning stages. PE Educators can use the Students section when considering individual learning journeys and their unique contexts, as each sub-component offers specific verbs taxonomies that align with different learning phases (e.g., age-and-stage) and the diverse ways students can demonstrate knowledge and understanding, creating a “multiple points of entry” approach to instruction and assessment.

- No single teaching style is deemed superior, nor should PE lessons be delivered exclusively through one instructional method (Mosston & Ashworth, 2008; Blair & Whitehead, 2015; Capel & Whitehead, 2015). Each PE educator brings unique qualities to their teaching and while some characteristics can naturally enhance one’s craft, others may create barriers that can hold them back. The “Educator” section and its four sub-components are intended to define what qualities an educator needs to be considered a QPE teacher. For example, a QPE educator hones “key characteristics” that inspire students, build caring and trusting relationships, and ensure that all students feel included. To provide students with a meaningful quality PE experience, dedicated QPE educators engage in ongoing “continuous learning” and reflective teaching practices. They are guided by “evidence- & practice-informed approaches” (e.g., essential and foundational elements), apply and advocate for “socially just & equity-oriented practices” (Luguetti & Hordvik, 2024), and are guided by a student-centered philosophy to create positive movement and learning spaces that support diverse needs and interests of every student. The Educators section is connected to all parts of the QPE Foundations Framework. It acknowledges that QPE educators need to have a strong understanding of: various teaching styles that support the diverse ways students learn (Student section); reflective practices on values, social norms, and assumptions (Mezirow, 2009) and the consideration of the contextual learning experiences of both the students and educators (Walton-Fisette et al., 2019) (Environment section); and, intentional strategies that put students at the center of their learning journey to create meaningful PE experiences (Instruction section).

- QPE learning environments, whether indoors or outdoors or on the land, ice, snow, or water, must emphasize multiple levels of safety—physical, emotional, mental, social, spiritual, and cultural well-being (CDC, 2004). The “Environment” section acknowledges that learning environments are complex and how multiple factors interact to shape students’ learning experiences and sense of belonging in PE. The four environmental sub-components—Intrapersonal (emotional well-being), Interpersonal (social dynamics), Sociocultural (cultural norms and values), and Structural (physical space)—significantly shape students’ experiences, acting as either participation barriers or facilitators. The Environment section is directly connected to other parts of the QPE Foundations Framework. For example, when PE educators commit to implementing student-centered strategies and utilize evidence- & practice-information approaches, it creates opportunities for students’ acquisition to develop in a learning environment that welcomes all types of learners. In addition, when PE educators embed socially just & equity-oriented practices, engage in continuous learning, and build a reflective learning culture, both students and educators can develop a better understand of how the environmental elements create barriers and be proactive and responsive with identifying and addressing those participation barriers (Ní Chróinín et al., 2024). Furthermore, each Environment sub-component can have a direct influence on student motivation, interactions, and connections with PE and by adapting Instruction to involve Students with co-creating their learning environments, Educators can drastically improve the overall sense of belonging, agency, and ownership in their QPE program.

- The “Instruction” section and its four sub-components—Student-Centered Strategies, Diverse & Relevant Activities, Authentic & Constructive Assessment, and Reflective Learning Culture—shape teaching and learning in PE. Each sub-component includes important focal points (Table 8) that will support PE educators’ decision-making for their planning and implementation of their provincial and/or territorial PE curricula. For example, in QPE programs, all instructional opportunities should be tailored to students’ needs, interests, age-and-stage, characteristics, and abilities as this will help students find joy in, for, and through movement, creating opportunities for creativity and exploration (Beni et al., 2016; Houser & Kriellaars, 2023; Luguetti & Alfrey, 2024; CDC, 2004). When both Students and Educators work together, they are building a deeper understanding and connection to PE Instruction and the learning Environment, improving their motivation and positive attitudes towards physical activity, movement, and living well. Incorporating student voice and choice (i.e., Student-Centered Strategies) is a fundamental component of creating quality PE experiences that support Students’ wholistic development (e.g., Acquisition, Comprehension, Formation, and Consolidation). And, understanding student progress (Student section) requires “Authentic & Constructive Assessment” practices (i.e., thoughtful collection of learning evidence; Wholistic Verb Wheel) as this information guides instructional decisions and helps PE educators create responsive learning experiences (Gini-Newman & Case, 2015; Lund & Veal, 2013a, 2013b; Gini-Newman & Gini-Newman, 2020; Lieberman et al., 2024). QPE educators understand the value in a “Reflective Learning Culture” as it serves as a powerful catalyst for growth in PE, benefiting both students and educators. When embedded thoughtfully, reflective practices can, but are not limited to, guiding Continuous Learning, identifying Environment barriers or facilitators, helping communicate curriculum objectives, and providing self- or peer-assessment opportunities for determining progress in learning. Lastly, the inclusion of “Diverse & Relevant Activities” provides Students with multiple opportunities to find joy in PE and connect various acquired movements and skills with real-life experience, making learning both relevant and impactful (Fletcher & Ní Chróinín, 2021). When implementing Diverse & Relevant Activities, adopting a Meaningful Physical Education (MPE) approach (Fletcher et al., 2021; Fletcher & Ní Chróinín, 2021; Beni et al., 2016; Ní Chróinín et al., 2024) will encourage Students to reflect on how movement experiences relate to their values, challenge social norms, and question assumptions (Mezirow, 2009). And, by Educators implementing “Student-Centered Strategies”, this approach will intentionally create opportunities that help Students foster lifelong engagement in movement and physical activity (Luguetti & Alfrey, 2024; Beni et al., 2016; Davis et al., 2023).

4.3.2. Exploring the QPE Outcomes Framework—Skills for Life: Benefits and Instructional Goals

- “affirmed and challenged through inclusive physical and health education;

- respected as unique and individual students;

- confident, courageous, and reflective decision makers;

- motivated and competent movers and caretakers;

- respectful and empathetic towards themselves, others, and their environment;

- resilient persons with a sense of self, worth, agency, and accomplishment;

- knowing of their rights and responsibilities for individual and collective well-being.”

- Experiencing joy through movement & living well.

- Instilling agency and ownership.

- Developing skills and life competencies.

- Understanding self, others, and the world.

- Connecting to the community, place, and land.

- Attuning a sense of resiliency.

- Engaging as socially just and equity-oriented community members.

- Nurturing empathy and respectful relationships.

4.4. Further Explanation & Example of How the QPE Outcomes Framework Aligns with the PE Competencies

- Think: Students critically reflect on their physical activity preferences and the impact of movement on their well-being, fostering deeper awareness of how physical activity supports a healthy lifestyle.

- Move: As they engage in various physical activities, students develop movement competence and confidence, enhancing their physical literacy across different settings.

- Feel: The emphasis on enjoyment nurtures a positive emotional connection to movement, improving motivation, self-efficacy, and their sense of belonging.

- Act: Students are encouraged and empowered to make informed decisions about their physical activity participation, fostering autonomy and a lifelong commitment to movement and living well.

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alfrey, L. (2023). An expansive learning approach to transforming traditional fitness testing in health and physical education: Student voice, feelings and hopes. Curriculum Studies in Health and Physical Education, 15(1), 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auld, M. E., Allen, M. P., Hampton, C., Montes, J. H., Sherry, C., Mickalide, A. D., Logan, R. A., Alvarado-Little, W., & Parson, K. (2020). Health literacy and health education in schools: Collaboration for action. In NAM Perspectives. National Academy of Medicine. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beach, H., & Strijack, T. N. (2020). Reclaiming our students: Why children are more anxious, aggressive, and shut down than ever—And what we can do about it. Page Two. Available online: https://pagetwo.com/book/reclaiming-our-students/ (accessed on 8 December 2024).

- Beni, S., Fletcher, T., & Ní Chróinín, D. (2016). Meaningful experiences in physical education and youth sport: A review of the literature. Quest, 69(3), 291–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birch, D. A., Goekler, S., Auld, M. E., Lohrmann, D. K., & Lyde, A. (2019). Quality assurance in teaching K–12 health education: Paving a new path forward. Health Promotion Practice, 20(6), 845–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blair, R., & Whitehead, M. (2015). Designing teaching approaches to achieve intended learning outcomes. In S. Capel, & M. Whitehead (Eds.), Learning to teach physical education in the secondary school: A companion to school experience (4th ed., pp. 204–218). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bleazby, J. (2015). Why some school subjects have a higher status than others: The epistemology of the traditional curriculum hierarchy. Oxford Review of Education, 41(5), 671–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, C., & Sims, S. K. (2020). Making a case for physical education teacher education as a viable degree program in colleges and universities. The Physical Educator, 77(4), 731–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capel, S., & Whitehead, M. (2015). Learning to teach physical education in the secondary school: A companion to school experience. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. (2004). High quality physical education. Division of Adolescent and School Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Available online: https://archive.cdc.gov/www_cdc_gov/healthyschools/pecat/highquality.htm (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- Davis, M., Gleddie, D. L., Nylen, J., Leidl, R., Toulouse, P., Baker, K., & Gillies, L. (2023). Canadian physical and health education competencies. Physical and Health Education Canada. Available online: https://phecanada.ca/sites/default/files/content/docs/canadian-phe-competencies-en-web.pdf (accessed on 9 February 2025).

- DODDS, P. (2006). Physical education teacher education (pe/te) policy. In D. Kirk, D. Macdonald, & M. O’Sullivan (Eds.), Physical education teacher education (PE/TE) policy (pp. 540–561). SAGE Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ennis, C. D. (2014). What goes around comes around … or does it? Disrupting the cycle of traditional, sport-based physical education. Kinesiology Review, 3(1), 70–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ercikan, K., & Pellegrino, J. W. (2017). Validation of score meaning for the next generation of assessments: The use of response processes. Journal of Educational Measurement, 50(1), 1–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferry, M., & Westerlund, R. (2023). Professional networks, collegial support, and school leaders: How physical education teachers manage reality shock, marginalization, and isolation in a decentralized school system. European Physical Education Review, 29(1), 74–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, T., & Ní Chróinín, D. (2021). Pedagogical principles that support the prioritisation of meaningful experiences in physical education: Conceptual and practical considerations. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 27(5), 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, T., Ní Chróinín, D., Gleddie, D., & Beni, S. (Eds.). (2021). Meaningful physical education: An approach for teaching and learning. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, H. (2021). From ideas to action: Transforming learning to inspire action on critical global issues. Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gini-Newman, G., & Case, R. (2015). Creating thinking classrooms: Leading educational change for a 21st century world. The Critical Thinking Consortium. [Google Scholar]

- Gini-Newman, G., & Gini-Newman, L. (2020). Powerful instruction and powerful assessment: The double-helix of learning. Canadian School Libraries. Available online: https://researcharchive.canadianschoollibraries.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/TMC6_2020_Gini-NewmanGini-Newman.pdf (accessed on 28 January 2025).

- Gleddie, D. L., & Morgan, A. (2021). Physical literacy praxis: A theoretical framework for transformative physical education. Prospects, 50(1), 31–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodson, I. F. (2011). Developing life and work histories of teachers. In Life politics. SensePublishers. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halas, J. M. (2011). Aboriginal youth and their experiences in physical education: “This is what you’ve taught me”. PHENex Journal, 3(2), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, J. (2018). The case for physical education becoming a core subject in the national curriculum (version 1). Loughborough University. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/2134/33950 (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Hayward, L., Jones, D. E., Waters, J., Makara, K., Morrison-Love, D., Spencer, E., & Wardle, G. (2018). Learning about progressions: CAMAU research report. Project Report. University of Glasgow. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3806612 (accessed on 6 December 2024).

- Hemphill, M. A., Templin, T. J., & Wright, P. M. (2013). Implementation and outcomes of a responsibility-based continuing professional development protocol in physical education. Sport, Education and Society, 20(3), 398–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houser, N., & Kriellaars, D. (2023). “Where was this when I was in Physical Education?” Physical literacy enriched pedagogy in a quality physical education context. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 5, 1185680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilborn, M., Lorusso, J., & Francis, N. (2016). An analysis of Canadian physical education curricula. Canadian Journal of Education, 22(1), 23–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohl, H. W., III, & Cook, H. D. (2013). Physical activity and physical education: Relationship to growth, development, and health. In Educating the student body: Taking physical activity and physical education to school. National Academies Press (US). Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK201497/ (accessed on 6 February 2025).

- Kretchmar, R. S. (2008). The increasing utility of elementary school physical education: A mixed blessing and unique challenge. The Elementary School Journal, 108, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieberman, L. J., Houston-Wilson, C., & Grenier, M. (2024). Strategies for inclusion: Physical education for everyone (4th ed.). Human Kinetics. Available online: https://us.humankinetics.com/products/strategies-for-inclusion-4th-edition-with-hkpropel-access (accessed on 6 January 2025).

- Luguetti, C., & Alfrey, L. (2024, October 23). Amplifying student voice in physical education. Physical and Health Education Canada. Available online: https://phecanada.ca/professional-learning/journal/amplifying-student-voice-physical-education (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Luguetti, C., & Hordvik, M. (2024). Nurturing activist teachers in physical education teacher education. In Social pedagogy in physical education: Human-centred practice. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, J. L., & Veal, M. L. (2013a). Assessment-driven instruction in physical education: A standards-based approach to promoting and documenting learning. Human Kinetics. [Google Scholar]

- Lund, J. L., & Veal, M. L. (2013b). Assessment-driven instruction in physical education. Human Kinetics. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, S., Walton-Fisette, J. L., & Luguetti, C. (2022). Pedagogies of social justice in physical education and youth sport. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, J., Ramirez Varela, A., Costa, J., Onofre, M., Dudley, D., Cristão, R., Pratt, M., Hallal, P. C., & Tassitano, R. (2025). Worldwide policy, surveillance, and research on physical education and school-based physical activity: The global observatory for physical education (GoPE!) conceptual framework and research protocol. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 22(4), 444–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mears, D. (2008). The effects of physical education requirements on physical activity of young adults. American Secondary Education, 36(3), 70–83. [Google Scholar]

- Melnychuk, N., Robinson, D., Lu, C., Chorney, D., & Randall, L. (2011). Physical education teacher education (PETE) in Canada. Canadian Journal of Education/Revue Canadienne de l’éducation, 34(2), 148–168. [Google Scholar]

- Mezirow, J. (2009). Transformative learning theory. In J. Mezirow, & E. W. Taylor (Eds.), Transformative learning in practice: Insights from community workplace, and higher education (pp. 18–32). Jossey-Bass. Available online: https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=2774011 (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- Montemurro, G., Cherkowski, S., Sulz, L., Loland, D., Saville, E., & Storey, K. E. (2023). Prioritizing well-being in K–12 education: Lessons from a multiple case study of Canadian school districts. Health Promotion International, 38(2), daad003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosston, M., & Ashworth, S. (2008). Teaching physical education (1st online ed.). Spectrum Institute for Teaching and Learning. Available online: https://spectrumofteachingstyles.org/e-book-download/ (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- Ní Chróinín, D., Iannucci, C., Luguetti, C., & Hamblin, D. (2024). Exploring teacher educator pedagogical decision-making about a combined pedagogy of social justice and meaningful physical education. European Physical Education Review, 30(4), 671–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pangrazi, R. P., & Beighle, A. (2020). Essential components of a quality physical education program. Human Kinetics. Available online: https://canada.humankinetics.com/blogs/excerpt/essential-components-of-a-quality-physical-education-program (accessed on 3 December 2024).

- Parfitt, G., Pavey, T., & Rowlands, A. (2009). Children’s physical activity and psychological health: The relevance of intensity. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/24042810_Children’s_physical_activity_and_psychological_health_The_relevance_of_intensity (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- PHE Canada. (2025). QPE definition & QPE frameworks: Foundations and outcomes—Skills for life (C. Poulin, T. Zakaria, & M. Davis, Eds.). Physical and Health Education Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Physical and Health Education Canada. (2023). Inclusion of students of all abilities in school-based physical activity programs: A Guidebook. ISBN 978-1-927818-86-2. Available online: https://phecanada.ca/sites/default/files/content/docs/Program/inclusion-of-Students-of-all-abilities-guidebook.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2024).

- Pulimeno, M., Piscitelli, P., Colazzo, S., Colao, A., & Miani, A. (2020). School as ideal setting to promote health and wellbeing among young people. Health Promotion Perspectives, 10(4), 316–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, K. A. R., Gaudreault, K. L., & Woods, A. M. (2018). Physical education teachers’ perceptions of perceived mattering and marginalization. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 37(2), 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, K. A. R., Templin, T. J., & Gaudreault, K. L. (2013). Understanding the realities of school life: Recommendations for the preparation of physical education teachers. Quest, 65(4), 442–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, D. B., Sulz, L., Morrison, H., Wilson, L., & Harding-Kuriger, J. (2023). Health education curricula in Canada: An overview and analysis. Curriculum Studies in Health and Physical Education, 15(1), 77–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallis, J. F., McKenzie, T. L., Kolody, B., Lewis, M., Marshall, S., & Rosengard, P. (1999). Effects of health-related physical education on academic achievement: Project SPARK. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 70(2), 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaefer, L., & Wasyliw, D. (2018, June 25). What is the impact of physical education on students’ well-being and academic success? EdCan Network. Available online: https://www.edcan.ca/articles/impact-physical-education-students-well-academic-success/ (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Spicer, C., & Robinson, D. B. (2021). Alone in the gym: A review of literature related to physical education teachers and isolation. Kinesiology Review, 10(1), 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Canada. (2024). Number of students in elementary and secondary schools, by school type and program type. (Table 37-10-0109-01). Government of Canada. [CrossRef]

- Sulz, L., Davis, M., & Damani, D. (2023). “Are we there yet?” An examination of teacher diversity within Canada’s physical and health education community. Revue phénEPS/PHEnex Journal, 13(2). Available online: https://ojs.acadiau.ca/index.php/phenex/article/view/4349/3813 (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- Sulz, L., Morrison, H., Robinson, D. B., & Barrett, J. (2025). Contemporary physical education curricula across Canada: An overview and analysis. Curriculum Studies in Health and Physical Education, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulz, L., Robinson, D. B., Morrison, H., Read, J., Johnson, A., Johnston, L., & Frail, K. (2024). A scoping review of K–12 health education in Canada: Understanding school stakeholders’ perceptions. Curriculum Studies in Health and Physical Education, 16(1), 41–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toulouse, P. (2016). What matters in Indigenous education: Implementing a vision committed to holism, diversity and engagement. In Measuring what matters, people for education. Toronto. Available online: https://peopleforeducation.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/MWM-What-Matters-in-Indigenous-Education.pdf (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Trudeau, F., & Shephard, R. J. (2008). Physical education, school physical activity, school sports, and academic performance. International Journal of Behavioural Nutrition and Physical Activity, 5, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truelove, S., Bruijns, B. A., Johnson, A. M., Burke, S. M., & Tucker, P. (2021). Factors that influence Canadian generalist and physical education specialist elementary school teachers’ practices in physical education: A qualitative study. Canadian Journal of Education, 44(1), 202–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. (2021). The case for inclusive quality physical education policy development: A policy brief. UNESCO. Available online: https://www.icsspe.org/system/files/Making%20the%20case%20for%20inclusive%20quality%20physical%20education%20policy%20development%20a%20policy%20brief.pdf (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- United Nations General Assembly. (1989). Convention on the rights of the child. United Nations, Treaty Series, 1577(3), 1–23. Available online: https://sithi.org/medias/files/projects/sithi/law/Convention%20on%20the%20Rights%20of%20the%20Child.ENG.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- Walters, W., Robinson, D., Barber, W., & Spicer, C. (2025). The physical, social, and professional isolation of physical education teachers. Curriculum Studies in Health and Physical Education, 16(1), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton-Fisette, J. L., Sutherland, S., & Hill, J. (Eds.). (2019). Teaching about social justice issues in physical education. Information Age Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by design (2nd ed.). Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development ASCD. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (2021). Promoting physical activity through schools: A toolkit. World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2022). Promoting physical activity through schools: Policy brief. Available online: https://iris.who.int/server/api/core/bitstreams/228fb58c-c720-4043-8c94-57ea3f969363/content (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- World Health Organization & UNESCO. (2021). Making every school a health-promoting school: Implementation guidance. (License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO). World Health Organization. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/341908 (accessed on 26 April 2025).

| Province (P) or Territory (T) | PE Time Requirements |

|---|---|

| British Columbia (P) Yukon (T) | No longer specific time recommendations with the new K–10 curricula. Integrated learning occurs between grades 1–6. |

| Alberta (P) Northwest Territories (T) | Grades 1–9 minimum PE instruction is 150 min per week. |

| Saskatchewan (P) | Grades 1–8 are required to have 120–150 min of physical education per week (still dependent on school division). Grades 9–10 are required to have 150 min of physical education per week. |

| Manitoba (P) Nunavut (T) | Over a six-day cycle, K is about 75 min, 150 min for grades 1–6, 134 min for grades 7–8, and grades 9–10 is approximately 55 h over the span of 1 course credit per grade. More details on the breakdown can be viewed at this link: Retrieved from: https://www.edu.gov.mb.ca/k12/cur/physhlth/c_overview.html, accessed on 1 December 2025. |

| Ontario (P) | There are no mandated minutes for PE, only guidelines. The recommended guideline is 150 min per week. |

| Quebec (P) | Grades 1–6 are required to have 120 min per week and grades 7–8 receive approximately 60–90 min. There is no time allocation mandated for secondary students (9–12/CEGEP). |

| New Brunswick (P) | Kindergarten students are required to have 75 min of PE in a six-day cycle (or 16 min/day). Grades 1–6 receive 150 min of PE in a six-day cycle (or, 33 min/day). Grades 7–8 are recommended to have 134 min of PE in a six-day cycle (or, 30 min/day). Grades 9–10 have 2 PE/HE credits with 1 credit equalling 55 h of PE/grade. In grades 11–12, there are 2 credits with each requiring a Physical Activity Practicum consisting of a minimum of 50% of moderate to vigorous physical activity. |

| Nova Scotia (P) | Grades K–2 are required to have 20 min of physical education per day, Grade 3 is required to have 30 min per day, and Grades 4–6 are required to have 20 min per day. There are no time allocations for grades 7 and up. |

| Prince Edward Island (P) | Grades K–6 are required to have 75 min of physical education per week or 90 min per 6-day cycle. Grades 7–9 are required to have 60–90 min of physical education per week or 72–108 min per 6-day cycle. |

| Newfoundland & Labrador (P) | Grades K–3 physical education is recommended to have a portion of 30% of instruction time, at administrator’s discretion, as part of an integrated approach with other specialized subjects. Grades 4–6 is 6% recommended physical education time, and therefore also site-based. Grade 7–9 is recommended to have 6% of instructional time. High School requires 2 credits (i.e., 1 year). |

| Province/Territory, Course | Categorized Topics (Curriculum Competencies, General Outcomes, Goals, General Learning Outcomes, Strands, Core Competencies, Outcomes) |

|---|---|

| British Columbia (and Yukon), Physical and Health Education | Curriculum Competencies: physical literacy; healthy and active living; school and community health; mental well-being |

| Alberta (and Northwest Territories, Nunavut), Physical Education | General Outcomes: activity; benefits health; cooperation; do it daily…for life |

| Saskatchewan, Physical Education | Goals: active living; skillful movement; relationships |

| Manitoba, Physical Education/Health Education | General Learning Outcomes: movement; fitness management; safety; personal and social management; healthy lifestyle practices |

| Ontario, Health and Physical Education | Strands: social-emotional learning skills; active living; movement competence: skills, concepts, and strategies; healthy living |

| Québec, Physical Education and Health | Core Competencies: to perform movement skills in different physical activity settings; to interact with others in physical activity settings; to adopt a healthy active lifestyle |

| New Brunswick, Physical Education | Strands: movement skills and concepts; movement strategies and tactics; well-being |

| Nova Scotia, Physical Education 1 | Outcomes: learners will analyze health-related fitness; learners will analyze motivation principles in different types of physical activities; learners will implement fundamental movement skills and movement concepts within dance (and gymnastics, games, active pursuits); learners will apply decision-making skills to fundamental movement skills and movement concepts during different types of physical activities; learners will apply communication and interpersonal skills during different types of physical activities; learners will investigate the well-being and safety of self and others during different types of physical activities in multiple environments |

| Prince Edward Island, Physical Education | Goals: active living; skillful movement; relationships |

| Newfoundland and Labrador, Physical Education | General Curriculum Outcomes: in movement (e.g., perform efficient, creative and expressive movement patterns consistent with an active living lifestyle); about movement (e.g., demonstrate critical thinking and creative thinking skills in problem posing and problem solving related to movement); through movement (e.g., demonstrate socially responsive behavior within the school and community; exhibit personal responsibility for the social, physical and natural environment during physical activity; exhibit personal development, such as positive self-esteem, self-responsibility, decision-making, cooperation, self-reflection and empowerment during physical activity) |

| Essential Elements | Foundational Elements |

|---|---|

|

|

| Think | Students will evaluate and analyze movement concepts, strategies, and tactics to meet the needs in their context. |

| Move | Students will develop and apply movement skills in a variety of movement activities across diverse environments. |

| Feel | Students will demonstrate appropriate behaviours that facilitate healthy relationships, and responsible, respectful, personal, and social behaviors with self, others, and the environment. |

| Act | Students will engage in healthy, active lives now and in the future. |

| Students | |

|---|---|

| Acquisition | A student has no prior knowledge or capacity and acquires new information through experiencing and exploring. |

| Formation | A student builds on acquired knowledge and capabilities and grasps information through practicing and refining. |

| Comprehension | A student takes on a proactive role and weaves information together through drawing and testing connections. |

| Consolidation | A student draws authentic connections through transferring their capabilities into meaning. |

| Educators | |

|---|---|

| Key Characteristics | Embody essential characteristic traits such as empathy, enthusiasm, and effective communication to build and sustain caring and trusting relationships for inspiring students. |

| Continuous Learning | Engage in ongoing professional development and reflective practices to enhance their teaching skills and adapt to the evolving needs of their students. |

| Evidence- & Practice-Informed Approaches | Are guided by and stay informed about the latest research and best practices in PE to implement effective teaching strategies for improving student outcomes and connections with PE. |

| Socially Just & Equity-Oriented Practices | Possess foundational knowledge of social justice and equity to effectively address and meet diverse needs to create environments that promote fairness, safety, and access for all students. Actively teaching about and for social justice and equity in their program ensures that every learner feels valued and supported. |

| Environment | |

|---|---|

| Intrapersonal | Internal factors that can positively influence participation because of feelings about oneself, beliefs in one’s ability to participate, and feelings of being treated fairly and equally to others. |

| Interpersonal | Relationship-based factors that enhance participation because of positive feelings and supportive attitudes from others, or encouragement, engagement, and support from teachers, parents/caregivers, friends, or other social networks. |

| Sociocultural | Cultural and social factors that promote and embrace diversity, acceptance, respect, and understanding regarding people with diverse abilities, varying identities, and background experiences. |

| Structural | Addresses the physical and organizational elements that make participation possible by considering the environment’s safety and accessibility. May include the thoughtful design and layout of facilities, reliable transportation, financial resources, diverse programming options, and participation requirements. |

| Instruction | |

|---|---|

| Student-Centered Strategies | Student voice and choice drive programming, creating opportunities for leadership and ownership in the movement journey. This approach fosters joy through movement while encouraging creativity and exploration |

| Diverse & Relevant Activities | Activities reflect student interests and backgrounds, promoting active participation and meaningful engagement. This approach prioritizes learning processes over outcomes, providing multiple entry points tailored to students’ needs, abilities, and developmental stages. |

| Authentic & Constructive Assessment | Students demonstrate understanding through meaningful, real-world applications while receiving constructive feedback from peers and educators. This collaborative approach highlights strengths, supports growth, and builds student agency in the learning process. |

| Reflective Learning Culture | Ongoing self-assessment and critical thinking by both students and educators creates a dynamic learning environment that continuously adapts and improves to enhance educational outcomes. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Poulin, C.; Davis, M. Advancing Quality Physical Education: From the Canadian PHE Competencies to the QPE Foundations and Outcomes Frameworks. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1376. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101376

Poulin C, Davis M. Advancing Quality Physical Education: From the Canadian PHE Competencies to the QPE Foundations and Outcomes Frameworks. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(10):1376. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101376

Chicago/Turabian StylePoulin, Caleb, and Melanie Davis. 2025. "Advancing Quality Physical Education: From the Canadian PHE Competencies to the QPE Foundations and Outcomes Frameworks" Education Sciences 15, no. 10: 1376. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101376

APA StylePoulin, C., & Davis, M. (2025). Advancing Quality Physical Education: From the Canadian PHE Competencies to the QPE Foundations and Outcomes Frameworks. Education Sciences, 15(10), 1376. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101376