Agentic Actions and Agentic Perspectives Among Fellowship-Funded Engineering Doctoral Students

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Fellowships are competitively funded by sources internal and external to the institution, including government agencies and nonprofits. Fellowships typically provide for students’ financial needs without requiring additional work tasks (Bowen & Rudenstine, 1992; Lovitts, 2002; Mendoza et al., 2014). Thus, fellowships are often considered by students and their advisors to be the most desirable form of funding because students can focus on their coursework and dissertation research without additional teaching or research responsibilities. The open-ended nature of fellowships affords students much greater autonomy and agency (Graddy-Reed et al., 2021; Herzig, 2004; Szelényi, 2013) compared to other funding.

- Research assistantships are often funded through research grants awarded to faculty members; work responsibilities are motivated by the goals of the grant, funding agency, advisor, and any other collaborators on the research grant (Niemczyk, 2015). Research assistantships provide structured research training and opportunities to interact with faculty and peers (Millett & Nettles, 2006) as opportunities for socialization into the department and discipline. Within engineering, research assistantships are typically funded through either government entities or industry.

- Teaching assistantships are typically funded by academic departments to help with the teaching responsibilities of a class, such as grading, holding office hours, and leading recitation or lab sections (Prieto & Meyers, 2001). Teaching assistantships are perceived as the least desirable funding because they distract from research and degree progress (Borrego et al., 2021). Some prior studies found that teaching assistantships extend STEM doctoral students’ time-to-degree (Knight et al., 2017) while others found no difference (Nettles & Millett, 2006).

- How does fellowship funding contribute to or undermine agency of graduate student recipients?

- What fellowship circumstances, such as timing and internal vs. external source, determine the extent to which a fellowship will impact doctoral student agency?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Agency in Graduate Education

2.2. The Context for Doctoral Student Agency

2.3. Types of Fellowships

3. Methods

3.1. Participants

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Data Analysis

3.4. Quality

3.5. Author Positionality

4. Findings

4.1. Agentic Perspectives

4.1.1. Flexibility Influencing Agentic Perspectives

Again, while others took the agentic action of changing advisors, these students had the agentic perspective that switching was an option if their situation deteriorated.pretty adamant about the money follows you, so had I decided to switch universities or finish my PhD at a national lab that the money would stay with me. So, it’s not really contingent on you sticking with your advisor if something goes wrong.(Hannah)

4.1.2. Access Influencing Agentic Perspectives

4.1.3. Validation Influencing Agentic Perspectives

4.2. Agentic Actions

4.2.1. Flexibility Influencing Agentic Actions

I have to use them simultaneously because I need [first fellowship] to pay for my tuition, and I need the [second fellowship] to pay for my rent. But then, the Financial Aid office will say, “Well, now you have $[X] fellowship, so we’re going to deduct that from your other funding” […] I’ve had to write letters and convince Financial Aid that I need this money.(Malik)

4.2.2. Access Influencing Agentic Actions

5. Discussion

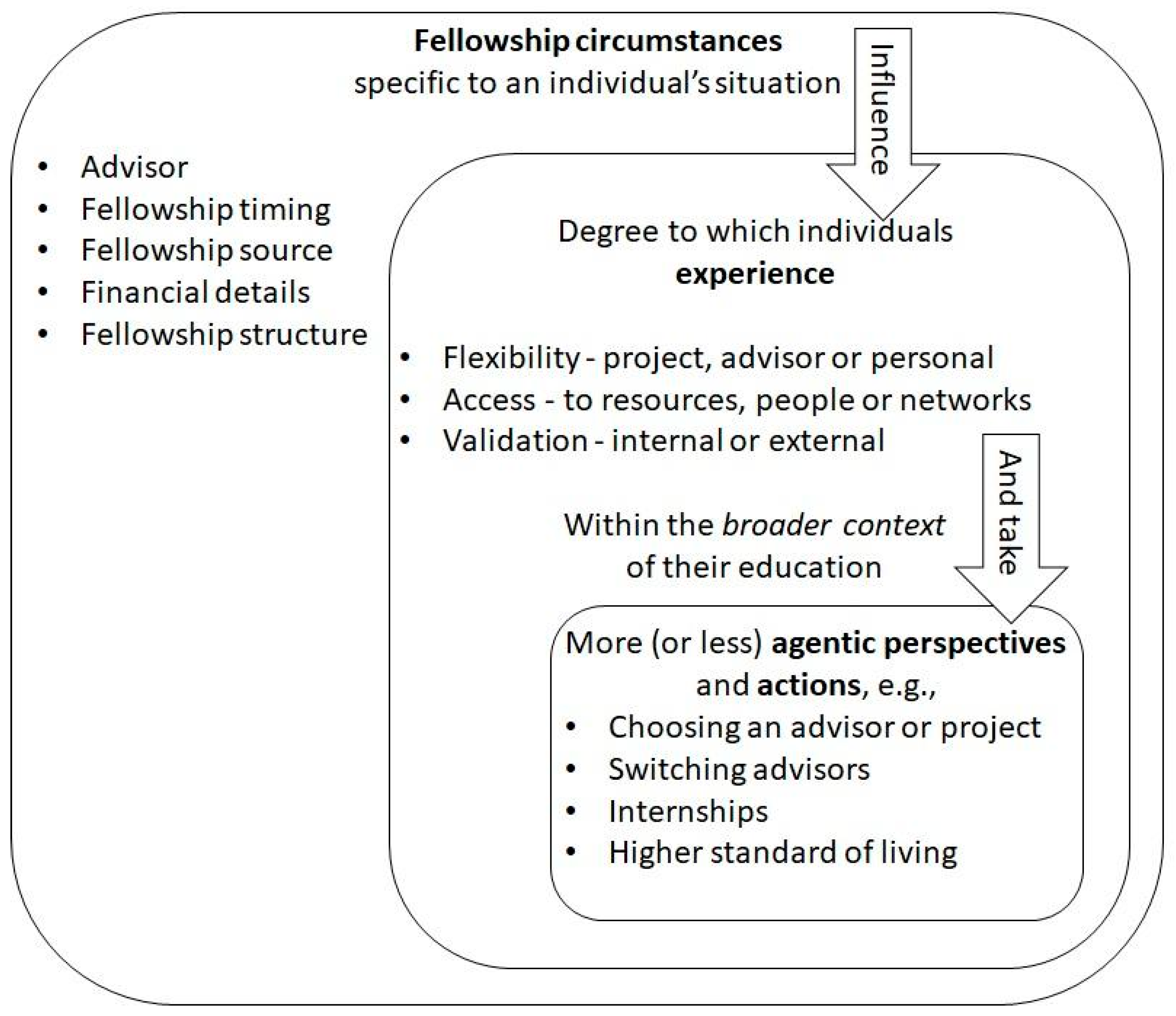

5.1. RQ1 How Does Fellowship Funding Contribute to or Undermine Agency of Graduate Student Recipients?

5.2. RQ2 What Fellowship Circumstances, Such as Timing and Funder, Determine the Extent to Which a Fellowship Will Impact Doctoral Student Agency?

5.3. Contributions to Theory

5.4. Implications

5.5. Limitations and Future Work

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| STEM | Science, technology, engineering, and mathematics |

| 1 | Although mentorship, advising and supervision are distinct concepts, the equipment-intensive nature of STEM disciplines and reliance on supervisors to provide funding for STEM students results in students expecting their dissertation supervisors to fulfill all roles. We use “advisor” as the most common term in the US and among our participants. |

References

- Amon, M. J. (2017). Looking through the glass ceiling: A qualitative study of STEM women’s career narratives. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ampaw, F. D., & Jaeger, A. J. (2012). Completing the three stages of doctoral education: An event history analysis. Research in Higher Education, 53(6), 640–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artiles, M. S., Knight, D. B., & Matusovich, H. M. (2023). Doctoral advisor selection processes in science, math, and engineering programs in the United States. International Journal of STEM Education, 10(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahnson, M., Satterfield, D., Perkins, H., Parker, M., Tsugawa, M., Cass, C., & Kirn, A. (2023). Engineer identity and degree completion intentions in doctoral study. Journal of Engineering Education, 112(2), 445–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdanier, C., Whitehair, C., Kirn, A., & Satterfield, D. (2020). Analysis of social media forums to elicit narratives of graduate engineering student attrition. Journal of Engineering Education, 109(1), 125–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blume-Kohout, M. E., & Adhikari, D. (2016). Training the scientific workforce: Does funding mechanism matter? Research Policy, 45(6), 1291–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bork, S. J., & Mondisa, J. L. (2022). Engineering graduate students’ mental health: A scoping literature review. Journal of Engineering Education, 111(3), 665–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrego, M., Choe, N. H., Nguyen, K., & Knight, D. B. (2021). STEM doctoral student agency regarding funding. Studies in Higher Education, 46(4), 737–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, W. G., & Rudenstine, N. L. (1992). In pursuit of the Ph.D. Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burt, B. A. (2017). Learning competencies through engineering research group experiences. Studies in Graduate and Postdoctoral Education, 8(1), 48–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, B. A., McKen, A. S., Burkhart, J. A., Hormell, J., & Knight, A. J. (2016, June 26–July 29). Racial microaggressions within the advisor-advisee relationship: Implications for engineering research, policy, and practice. 2016 ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition, New Orleans, LA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Charles, S. T., Karnaze, M. M., & Leslie, F. M. (2021). Positive factors related to graduate student mental health. Journal of American College Health, 70(6), 1858–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Graduate Schools. (2005). The doctor of philosophy degree: A policy statement. Council of Graduate Schools in the United States. [Google Scholar]

- Crede, E., & Borrego, M. (2012). Learning in graduate engineering research groups of various sizes. Journal of Engineering Education, 101(3), 565–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches (4th ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. (n.d.). Marie skłodowska-curie actions. Available online: https://marie-sklodowska-curie-actions.ec.europa.eu/ (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- Feldon, D. F., Wofford, A. M., & Blaney, J. M. (2022). Ph.D. pathways to the professoriate: Affordances and constraints of institutional structures, individual agency, and social systems. In Higher education: Handbook of theory and research (Volume 38, pp. 1–91). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, S. K. (2007). ‘‘I heard it through the grapevine’’: Doctoral student socialization in chemistry and history. Higher Education, 54, 723–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, K. L., & Newhouse, K. N. (2024). Updating our understanding of doctoral student persistence: Revising models using structural equation modeling to examine consideration of departure in computing disciplines. Research in Higher Education, 65(8), 1883–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germain-Alamartine, E., & Moghadam-Saman, S. (2020). Aligning doctoral education with local industrial employers’ needs: A comparative case study. European Planning Studies, 28(2), 234–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golde, C. M. (1998). Beginning graduate school: Explaining first-year doctoral attrition. In M. S. Anderson (Ed.), The experience of being in graduate school: An exploration. Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Golde, C. M. (2005). The role of the department and discipline in doctoral student attrition: Lessons from four departments. Journal of Higher Education, 76(6), 669–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graddy-Reed, A., Lanahan, L., & D’Agostino, J. (2021). Training across the academy: The impact of R&D funding on graduate students. Research Policy, 50(5), 104224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grady, R. K., La Touche, R., Oslawski-Lopez, J., Powers, A., & Simacek, K. (2014). Betwixt and between: The social position and stress experiences of graduate students. Teaching Sociology, 42(1), 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, K. A., Miller, C., & Roksa, J. (2023). Agency and career indecision among biological science graduate students. Studies in Graduate and Postdoctoral Education, 14(1), 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grote, D., Patrick, A. D., Lyles, C., Knight, D., Borrego, M., & Alsharif, A. (2021). STEM doctoral students’ skill development: Does funding mechanism matter? International Journal of STEM Education, 8(50), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haines, C., Wall Bortz, W., Fleming, G. C., Knight, D. B., Borrego, M., Denton, M., Chasen, A., & Alsharif, A. (2023). STEM program leaders’ strategies to diversify the doctoral student population: Incongruence with student priorities. Journal of Women and Minorities in Science and Engineering, 30(5), 41–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzig, A. H. (2004). Becoming mathematicians: Women and students of color choosing and leaving doctoral mathematics. Review of Educational Research, 74(2), 171–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horta, H., Cattaneo, M., & Meoli, M. (2018). PhD funding as a determinant of PhD and career research performance. Studies in Higher Education, 43(3), 542–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horta, H., Cattaneo, M., & Meoli, M. (2019). The impact of Ph.D. funding on time to Ph.D. completion. Research Evaluation, 28(2), 182–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q., & Jung, J. (2024). Career decision-making among Chinese doctoral engineering graduates after studying in the United States. Higher Education Quarterly, 78(2), 349–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, J., Quinn, B., Madon, T., & Lustig, S. (2007). Mental health need, awareness, and use of counseling services among international graduate students. Journal of American College Health, 56(2), 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaac, P. D., Koenigsknecht, R. A., Malaney, G. D., & Karras, J. E. (1989). Factors related to doctoral dissertation topic selection. Research in Higher Education, 30, 357–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, A. J., Mitchall, A., O’Meara, K., Grantham, A., Zhang, J., Eliason, J., & Cowdery, K. (2017). Push and pull: The influence of race/ethnicity on agency in doctoral student career advancement. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 10(3), 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinoshita, T., Knight, D., Borrego, M., & Bortz, W. W. (2020). Illuminating systematic differences in no job offers for STEM doctoral recipients. PLoS ONE, 15(4), e0231567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, D. B., Borrego, M., Kinoshita, T., & Choe, N. H. (2017). Investigating national-scale variation in doctoral student funding mechanisms across engineering disciplines. American Society of Engineering Education Annual Conference & Exposition. [Google Scholar]

- Knight, D. B., Grote, D. M., Kinoshita, T. J., & Borrego, M. (2024). PhD student funding patterns: Placing biomedical, biological, and biosystems engineering in the context of engineering sub-disciplines, biological sciences, and other STEM disciplines. Biomedical Engineering Education, 4(2), 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, D. B., Kinoshita, T., Choe, N., & Borrego, M. (2018). Doctoral student funding portfolios across and within engineering, life sciences, and physical sciences. Studies in Graduate and Postdoctoral Education, 9(1), 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, S. E. (2006). The master degree: A critical transition in STEM doctoral education [Doctoral Dissertation, University of Washington]. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, A. (2008). How are doctoral students supervised? Concepts of doctoral research supervision. Studies in Higher Education, 33(3), 267–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1986). But is it rigorous? Trustworthiness and authenticity in naturalistic evaluation. In D. D. Williams (Ed.), Naturalistic Evaluation (Vol. 1986, pp. 15–25). Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovitts, B. E. (2002). Leaving the ivory tower: The causes and consequences of departure from doctoral study. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Luxembourg National Research Fund. (n.d.). Homepage. Available online: https://www.fnr.lu/ (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Mackie, S. A., & Bates, G. W. (2019). Contribution of the doctoral education environment to PhD candidates’ mental health problems: A scoping review. Higher Education Research & Development, 38(3), 565–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, M. A., Wofford, A. M., Roksa, J., & Feldon, D. F. (2020). Finding a fit: Biological science doctoral students’ selection of a principal investigator and research laboratory. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 19(3), ar31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAlpine, L. (2012). Identity-trajectories: Doctoral journeys from past to present to future. Australian Universities’ Review, 54(1), 38–46. [Google Scholar]

- McAlpine, L., & Amundsen, C. (2009). Identity and agency: Pleasures and collegiality among the challenges of the doctoral journey. Studies in Continuing Education, 31(2), 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAlpine, L., & Amundsen, C. (2011). Doctoral education research-based strategies for doctoral students, supervisors and administrators. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza, P., Villarreal, P., & Gunderson, A. (2014). Within-year retention among Ph.D. students: The effect of debt, assistantships, and fellowships. Research in Higher Education, 55(7), 650–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merton, R. K. (1968). The Matthew effect in science: The reward and communication systems of science are considered. Science, 159(3810), 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldana, J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook (3rd ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Millett, C. M., & Nettles, M. T. (2006). Expanding and cultivating the Hispanic STEM doctoral workforce: Research on doctoral student experiences. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education, 5(3), 258–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MIT Office of Graduate Education. (n.d.). External fellowships. Available online: https://oge.mit.edu/fellowships/external-fellowships/ (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- National Science Foundation. (2024a). Doctorate recipients from U.S. universities: 2023 (NSF 25-300). Available online: https://ncses.nsf.gov/doctorate-recipients-from-u-s-universities-2023 (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- National Science Foundation. (2024b). NSF 24-591: NSF graduate research fellowship program (GRFP) solicitation (NSF 24-591). Available online: https://www.nsf.gov/funding/opportunities/grfp-nsf-graduate-research-fellowship-program/nsf24-591/solicitation (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- NC State University. (n.d.). Nationally competitive graduate fellowships. Available online: https://grad.ncsu.edu/student-funding/fellowships-and-grants/national/nationally-competitive-graduate-fellowships/ (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Nettles, M. T., & Millett, C. M. (2006). Three magic letters: Getting to Ph.D. JHU Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyet Nguyen, M., & Robertson, M. J. (2022). International students enacting agency in their PhD journey. Teaching in Higher Education, 27(6), 814–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemczyk, E. (2015). A case study of doctoral research assistantships: Access and experiences of full-time and part-time education students [Doctoral Dissertation, Brock University]. [Google Scholar]

- Northwestern University. (n.d.). External fellowships and grants. Available online: https://www.tgs.northwestern.edu/funding/fellowships-and-grants/external-fellowships-and-grants/ (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- O’Meara, K. (2013). Advancing graduate student agency. Higher Education in Review, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- O’Meara, K., Jaeger, A., Eliason, J., Grantham, A., Cowdery, K., Mitchall, A., & Zhang, K. (2014). By design: How departments influence graduate student agency in career advancement. International Journal of Doctoral Studies, 9(1), 155–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Meara, K., Knudsen, K., & Jones, J. (2013). The role of emotional competencies in faculty-doctoral student relationships. The Review of Higher Education, 36(3), 315–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paglis, L. L., Green, S. G., & Bauer, T. N. (2006). Does adviser mentoring add value? A longitudinal study of mentoring and doctoral student outcomes. Research in Higher Education, 47, 451–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, H. L., Bahnson, M., Tsugawa-Nieves, M. A., Satterfield, D. J., Parker, M., Cass, C., & Kirn, A. (2020). An intersectional approach to exploring engineering graduate students’ identities and academic relationships. International Journal of Gender, Science and Technology, 11(3), 440–465. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer, J., & Salancik, G. R. (2003). The external control of organizations: A resource dependence perspective. Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Portnoi, L. M., Chlopecki, A. L. A., & Peregrina-Kretz, D. (2015). Expanding the doctoral student socialization framework: The central role of student agency. The Journal of Faculty Development, 29(3), 5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Prieto, L. R., & Meyers, S. A. (2001). The teaching assistant training handbook: How to prepare TAs for their responsibilities. New Forums Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, S. L., Perez, R. J., & Schulz, J. M. (2022). How STEM lab settings influence graduate school socialization and climate for students of color. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 15(1), 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallai, G. M., Shanachilubwa, K., & Berdanier, C. G. (2023). Overlapping coping mechanisms: The hidden landscapes of stress management in engineering doctoral programs. International Journal of Engineering Education, 39(6), 1513–1530. [Google Scholar]

- Shanachilubwa, K., Sallai, G., & Berdanier, C. G. (2025). Elements of disenchantment: Exploring the development of academic disenchantment among US engineering graduate students. Journal of Engineering Education, 114(1), e20624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowell, R. S., Zhang, T., & Redd, K. (2008). Ph.D. completion and attrition: Analysis of baseline program data from the Ph.D. completion project. Council of Graduate Schools. [Google Scholar]

- Sverdlik, A., Hall, N. C., McAlpine, L., & Hubbard, K. (2018). The PhD experience: A review of the factors influencing doctoral students’ completion, achievement, and well-being. International Journal of Doctoral Studies, 13, 361–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szelényi, K. (2013). The meaning of money in the socialization of science and engineering doctoral students: Nurturing the next generation of academic capitalists? The Journal of Higher Education, 84(2), 266–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiry, H., Laursen, S. L., & Loshbaugh, H. G. (2015). “How do I get from here to there?” An examination of Ph.D. science students’ career preparation and decision making. International Journal of Doctoral Studies, 10, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torka, M., Kohl, U., & Mahoney, W. M. (2022). Funding of doctoral education and research. In M. Nerad, D. Bogle, U. Kohl, C. O’Carroll, C. Peters, & B. Scholz (Eds.), Towards a global core value system in doctoral education (pp. 110–132). UCL Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, N. A., Jean-Marie, G., Powers, K., Bell, S., & Sanders, K. (2016). Using institutional resources and agency to support graduate students’ success at a Hispanic serving institution. Education Sciences, 6(3), 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Rooij, E., Fokkens-Bruinsma, M., & Jansen, E. (2021). Factors that influence PhD candidates’ success: The importance of PhD project characteristics. Studies in Continuing Education, 43(1), 48–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walther, J., Sochack, N. W., & Kellam, N. N. (2013). Quality in interpretive engineering education research: Reflections on an example study. Journal of Engineering Education, 102(4), 626–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wofford, A. M., & Blaney, J. M. (2021). (Re)shaping the socialization of scientific labs: Understanding women’s doctoral experiences in STEM lab rotations. The Review of Higher Education, 44(3), 357–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerbe, E., Sallai, G. M., Shanachilubwa, K., & Berdanier, C. G. (2022). Engineering graduate students’ critical events as catalysts of attrition. Journal of Engineering Education, 111(4), 868–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Agency Codes | |||

| Agentic perspectives—perspectives or views taken when experiencing opportunities and constraints, e.g., seeing situations as possible to overcome, recognizing that they can get certain types of support, feeling in control of their career goals, and viewing critical feedback as a way to learn and grow | Agentic actions—strategic and enacted with self-awareness of goals and contexts, e.g., managing advisor relationship, getting needed support from people other than advisor, asking for help when needed, and taking steps to obtain skills or knowledge to advance their career goals | ||

| Inductive Codes (to describe experiences) | |||

| Flexibility—flexibility around project(s), advisor(s), or personal life arising from fellowship conditions | Access—access to physical resources, people, and networks, learning new skills, or research experiences as direct or indirect result of fellowship funding | Validation—internal or external perceptions of the student from having received a competitive or prestigious fellowship | |

| Fellowship Circumstance Codes | |||

| Fellowship timing—when fellowship funding starts with respect to year of study in graduate school and the duration of the funding | Fellowship source—internal fellowships are from the participant’s university; external fellowships originate from organizations other than their own | Fellowship structure—non-monetary aspects, including fellowship requirements and optional opportunities for involvement | Financial—monetary compensation associated with the fellowship, typically in the form of a salary or stipend, including benefits |

| Pseudonym | Fellowship Source | Timing of Fellowship Start | Fellowship Duration | Agentic Perspectives | Agentic Actions | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PF | AF | APN | ALNS | IV | ER | PF | AF | PFQL | APRC | ARE | ||||

| Kalia | Internal | Year 1 | 1 year | + | − | − | ||||||||

| Priya | Internal and External | Year 1 (I) Year 3 (E) | 1 year 3 years | +, − | + | + | + | + | ||||||

| Malik | External (2) | Year 1 (E1) Year 4 (E2) | 5 years 3 years | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | +, − | + | ||

| Caitlin | External (2) | Year 3–4 (E1) Year 5 (E2) | 1 year 7 mos | + | + | + | ||||||||

| Nadia | External | Year 1 | 5 years | − | + | − | +, − | |||||||

| Jamal | External | Year 1 | 5 years | + | + | +, − | + | |||||||

| Sophia | External | Year 3 | 3 years | + | +, − | + | + | − | + | − | ||||

| Elaine | Internal | Year 1 | 2 years | + | + | |||||||||

| Allison | External | Year 1 | 3 years | + | + | − | +, − | |||||||

| Taylor | Internal | Year 1 | 3 years | + | + | + | ||||||||

| Sydney | Internal and External | Year 1 (I) Year 3 (E) | 1 year 3 years | + | + | + | ||||||||

| Caleb | External | Year 3 | 3 years | + | ||||||||||

| Carlos | External | Year 2 | 3 years | + | + | + | +, − | + | + | + | ||||

| Hannah | External | Year 2 | 4 years | + | + | + | − | + | + | +, − | + | |||

| Avery | External | Year 2 | 3 years | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||

| Emma | External | Year 3 | 3 years | + | + | + | + | − | + | |||||

| Jenny | External | Year 1 | 3 years | − | + | +, − | ||||||||

| Maeve | External | Year 3 | 3 years | + | + | + | ||||||||

| Keysha | External | Year 1 | 4 years | − | + | + | + | + | +, − | |||||

| Mei | Internal | Year 1 | 1 sem | + | + | |||||||||

| Rose | External | Year 1 | 3 years | + | + | |||||||||

| Charlotte | Internal | Year 1 | 5 years | + | + | |||||||||

| Melissa | Internal and External | Year 2 (E) Year 5 (I) | 3 years 1 year | + | − | + | − | + | +, − | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Denton, M.; Chasen, A.; Fleming, G.C.; Borrego, M.; Knight, D. Agentic Actions and Agentic Perspectives Among Fellowship-Funded Engineering Doctoral Students. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1378. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101378

Denton M, Chasen A, Fleming GC, Borrego M, Knight D. Agentic Actions and Agentic Perspectives Among Fellowship-Funded Engineering Doctoral Students. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(10):1378. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101378

Chicago/Turabian StyleDenton, Maya, Ariel Chasen, Gabriella Coloyan Fleming, Maura Borrego, and David Knight. 2025. "Agentic Actions and Agentic Perspectives Among Fellowship-Funded Engineering Doctoral Students" Education Sciences 15, no. 10: 1378. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101378

APA StyleDenton, M., Chasen, A., Fleming, G. C., Borrego, M., & Knight, D. (2025). Agentic Actions and Agentic Perspectives Among Fellowship-Funded Engineering Doctoral Students. Education Sciences, 15(10), 1378. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101378