Abstract

In this study, two teachers of multilingual learners in the U.S. report case stories about how they implemented translanguaging approaches in support of their students’ social emotional learning. Translanguaging refers to bilinguals’ meaning-making process using their multilingual resources. In the first case story, Deborah created and utilized multilingual writing checklists in her 3rd grade classroom to encourage and support students’ multilingual writing practices. She enacted translanguaging as a collaborative space, which enabled students to shift their roles from learners to teachers, helping them to increase their confidence and collaboration. In the second case story, Walny applied translanguaging approaches to reading in his 9th grade English classroom. He utilized translanguaging to explain literary concepts, create a multilingual reading list, and send letters to families in students’ first languages, enacting translanguaging as a space for connecting the multilingual texts. His approaches enhanced his students’ engagement with the text, the teacher, and the peers. The results highlight the significance of teachers’ advocating for multilingual learners’ use of their entire linguistic repertoire for their academic success and personal growth, providing implications for language teacher education.

1. Introduction

In recent years, social emotional learning (SEL) has been an important aspect of schooling, due to the increasing interest in students’ emotional well-being and the relationship between affect and learning. SEL focuses on students’ development of social-emotional competence (SEC) in five areas, including self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision-making [1,2]. Teachers utilize SEL as systems of support for all students for their social-emotional well-being, which potentially help their personal and academic development [2,3]. Through SEL, support is provided for students who may need preventative measures, as well as students who have immediate risks.

We believe that SEL is particularly an essential area of development for multilingual (English) learners who begin schooling in their second language (L2). SEL enables them to navigate new linguistic and cultural environments successfully at school and develop strategies for utilizing their multilingual and multicultural competencies for their academic success and personal growth. While research in language education has reported that a new linguistic environment increases language learners’ anxiety and the negative effect of learners’ anxiety on their participation and performance [4,5], little has been discussed about how to support their positive learning experiences.

In this paper, we explore translanguaging as a strategy specifically supporting multilingual learners’ SEL. Translanguaging refers to “multiple discursive practices in which bilinguals engage in order to make sense of their bilingual worlds” [6] (p. 45). Teachers’ translanguaging practices in the classroom not only allow, but also encourage, students’ dynamic use of multiple languages in various formats (e.g., code-switching, code-mixing, and translation) to maximize their meaning-making processes. Research on translanguaging as a pedagogical strategy reports its positive effect on reducing multilingual learners’ negative emotional experiences and increasing their engagement in classroom activities [7]. In particular, translanguaging creates a welcoming learning environment for multilingual learners [8], through which they can further develop their bilingual identity and skills [7]. Our study further contributes to articulating the previous findings about the positive emotional effects of translanguaging on multilingual learners, by illustrating translanguaging strategies used in literacy practices in support of their SEL.

Researching SEL for multilingual learners at school is significant and timely, given that there has been an increasing number of multilingual learners in U.S. public schools. According to the latest education statistics [9], 5,025,995 multilingual learners (10.2 percent of the total enrollment) enrolled in U.S. public schools in 2018, which is up by 2 percent from 3,793,764 learners (8.1 percent) in 2000. Specifically, the two schools where the current study was conducted are located in Connecticut and Florida. Both the states have experienced an increasing number of multilingual learners in the past few decades. In Connecticut, the number of multilingual learners in school has increased from 3.6 percent in 2000 to 11.4 percent of the total enrollment in 2018, whereas it has increased from 7.7 percent to 10 percent in Florida during the same period [9]. The rapid and continued increase in multilingual learners in school clearly indicates the need for developing strategies in order to support multilingual learners’ SEL.

In this study, two teachers illustrate how they utilized translanguaging as a pedagogical strategy to support multilingual learners’ SEL through case stories. Three questions guided each teacher’s case story: (1) what are your beliefs and attitudes toward translanguaging and student learning? (2) what are the goals of your translanguaging approach? and (3) how does your translanguaging approach support multilingual learners’ SEL? In the following sections, we first introduce research on translanguaging pedagogy. Then, we present how translanguaging in these two teachers’ classrooms help multilingual learners increase collaboration and communication skills with their enhanced confidence and motivation. In conclusion, we discuss the significance of teachers’ understanding and advocating for students’ use of their entire linguistic repertoire for their academic success and personal growth.

2. Literature Review

Translanguaging refers to bilinguals’ meaning-making process using their multilingual linguistic recourses, which considers that bilingualism is based on interconnected systems rather than separate, multiple linguistic systems [9]. The concept, translanguaging, was coined by [10], who first used the Welsh term “trawsieithu” to refer to a pedagogical practice in the bilingual Welsh/English context. The term originally focused on students’ use of two languages within the classroom (allowing students to use their stronger and familiar language to develop proficiency in a new language towards the development of a relatively balanced proficiency in both languages). From this perspective, language practices that utilize translation, code-switching, and any synthesis of multilingual elements can be incorporated into the classroom practices for multilingual learners’ language learning and development.

The concept has been expanded and further developed by various scholars in recent years, significantly affecting bilingual education and bilingual practices [6,8,11,12,13]. Translanguaging is further defined by [13] (p. 1223).

Translanguaging involves both going between different linguistic structures and systems, including different modalities (speaking, writing, signing, listening, reading, remembering) and going beyond them. It includes the full range of linguistic performances of multilingual language users for purposes that transcend the combination of structures, the alternation between systems, the transmission of information and the representation of values, identities and relationships.

Language researchers who advocate for the need to incorporate students’ home languages into learning in school have broadened the concept by discussing the importance of translanguaging as culturally relevant and socially just pedagogy for multilingual learners. According to the culturally relevant pedagogy [14], it is important to utilize funds of knowledge, the knowledge that students bring with them from their homes and communities for their cognitive and overall development [15]. Translanguaging in the classroom helps utilize funds of knowledge and create a third space by allowing and encouraging students to enact their multicultural resources and identities in classrooms that focus on student-centered learning [16]. Translanguaging can also be considered a socially just pedagogy for multilingual learners, as it could enhance those students’ opportunities for academic success in school and beyond. Recognizing and utilizing their knowledge, experiences, and competencies that are often invisible or even prohibited in school gives the students a more socially just and inclusive education [17]. Translanguaging from this perspective helps these students not only acquire the knowledge and skills needed for academic success, but also experience positive emotions in a new school environment [17].

The view of translanguaging as a SEL strategy specifically emphasizes how translanguaging can provide multilingual learners with emotional and social support, through which they can develop several key competencies, including self-awareness and management, as well as relationship and collaboration skills. According to [18], translanguaging scaffolds multilingual learners’ emotions in their development of social and linguistic competencies. New linguistic environments generate high anxiety for students, which challenges these students’ social and academic development. Ref. [19] calls language learners’ anxiety an affective filter that limits learners’ processing of input for learning, claiming that lower anxiety is necessary for language acquisition. Research has reported a relationship between language learners’ anxiety and motivation in communication events, affecting their willingness to communicate [20]. Translanguaging helps multilingual learners manage their emotions and increase their participation in academic tasks [7,21]. Students reported that they felt happy and that they were significant members in the classroom when their teachers adopted translanguaging pedagogy [7]. Bilingual teachers in [22] argued that translanguaging particularly scaffolds multilingual learners’ emotions by offering them ways to recognize the value of their linguistic and cultural backgrounds and feel pride for who they are. Teachers’ translanguaging in this regard is a social action that welcomes multilingual learners and their bilingual practices in the classroom community [8]. Additionally, teachers’ careful use of translanguaging strategies not only helps multilingual learners reduce their feelings of isolation and anxiety, but also facilitates their engagement in academic tasks by utilizing their linguistic and cultural resources as funds of knowledge for their academic development [18].

These studies on translanguaging emphasize that incorporating students’ home languages into learning in school would benefit students, but few studies provide specific strategies for teachers to use to facilitate translanguaging pedagogy in the classroom. Translanguaging can create a space for multilingual learners to express and learn academic subjects in school, but creating such a space requires teachers’ clear understanding of students’ language use and purposefully inviting students to use their linguistic resources [23]. That is, teachers must develop specific strategies that acknowledge and encourage students’ use of translanguaging by moving beyond passively allowing it.

In this article, we explore how two teachers in different teaching contexts incorporate translanguaging into English literacy practices in their English/language arts lessons, by encouraging students to use their language skills beyond the English language. We focus on translanguaging as a significant support system for multilingual learners’ social-emotional well-being, potentially helping their personal and academic development.

3. Materials and Methodology: Two Case Stories

This study is based on two case stories that focus on translanguaging practices as a SEL strategy for multilingual learners in two different educational contexts. A case story “draws on individual stories of practice by blending aspects of the classic case study method with the tradition, artistry, and imagination of storytelling” [24] (p.107). The cases illustrated from the author’s perspective not only deal with their personal experiences through a form of narrative inquiry [25], but also reflect a cultural context of each case study [26] in which the narratives are told and interpreted. We adopted a case study method to offer teachers’ own explorations on translanguaging pedagogy in a specific context of English teaching through their own narratives about classroom practices, student participation, and relevant artifacts. As the study particularly focuses on social and emotional aspects of language education, we believe that teachers’ own narratives of classroom practices and student participation provide a window into their strategic use of translanguaging and its effects that may not be explicitly visible from the outside.

Two teachers, Deborah and Walny, provided case stories concerning their translanguaging approaches while working with multilingual learners in their classroom. Deborah works in a suburban K-5 public school in Connecticut with multilingual learners in first through fourth grade. The school has approximately 400 students with a 52 percent minority population and 30 percent of the students are eligible for free and reduced meals. There are currently 52 multilingual learners in her school, which is about 12 percent of the total school population. The number of multilingual learners at her school has tripled over the past ten years and continues to increase. The students she works with come from many language backgrounds including Albanian, Arabic, Japanese, Pashto, Portuguese, Russian, and Spanish. She has been teaching multilingual learners for over twenty years. Deborah has master’s degrees in TESOL and Instructional Technology. She is currently in the English Language Pedagogy doctoral program at Murray State University. She speaks Spanish and some German.

Walny is an English as a second or other language (ESOL) teacher in a public high school in Florida. He has been teaching language arts to multilingual learners for over four years. The school is located in the city of Homestead, a southern region of Miami where a high number of Latino and Haitian immigrant families reside. Nearly three fourths of the students in the school came from immigrant families, and over half of the students in the school have received school instruction in their first language in their home country. Among those students, 197 students were identified as multilingual learners, which comprises of 15 percent of the total student body. Many of the multilingual learners are newcomers to the country, with little or no English skills. The majority, 82 percent, of the multilingual learners speak Spanish as their first language, followed by French Creole speakers who make up 17 percent of the population of multilingual learners. Walny taught English in Cuba and Ecuador for over six years before coming to the United States. He speaks Spanish (L1) and French (intermediate). He is currently in the same Doctor of Arts Program with Deborah.

Both Deborah and Walny had taken a few courses that discussed translanguaging as a theoretical concept and a teaching strategy, and both had prior research experiences on the topics of teacher identity and pedagogy. JS, the first author, is a faculty member who has research interests in teacher identity and emotions in language education. JS first met Deborah and Walny in 2021 and 2020, respectively, as an instructor in the course(s) that they were taking and invited both the teachers to collaborative with her, as they had demonstrated their understanding of and strong belief in the benefits of translanguaging for multilingual learners. Both the teachers considered their students’ L1 skills assets for their academic success, by highlighting the need for teachers to advocate for their multilingual identity and practices. For example, Deborah stated that her students enter school with a rich knowledge of language and culture but this knowledge is often not included in their academic identities, due to the monolingual environment of the education system. In her view, this monolingual stance in school places multilingual learners in the role of a learner rather than an expert, limiting opportunities to show and utilize all of their academic knowledge, which, in turn, leads to their lack of self-confidence. Walny also pointed out a gap between his students’ English skills and academic language skills required for success in high school and emphasized the need for meaningful and effective instructional practices to fill this gap. He believed that the conventional English-only approaches place low or no value on their experiences and knowledge in their L1 and ignore these students’ social and linguistic needs. He highlighted the benefit of using a translanguaging approach for his students’ content learning as well as for their SEL, such as self-awareness, motivation, and confidence.

The case stories in this study reflect each teacher’s own lived experiences in the classroom, as well as the collaborative dialogue among three of us on the topic of pedagogy, teacher beliefs, and student learning. Our collaborative dialogue officially began during the fall semester in 2021 and ended at the end of spring semester in 2022. During the period, we met multiple times through Zoom meetings and communicated and interacted via emails and Google Docs. At the first meeting, we discussed our common goal of the project, linking the areas between the effects of translanguaging on multilingual learners and the needs for their SEL. After discussing each teacher’s translanguaging practice and their views on students’ SEL, we identified areas of SEL relevant to each teacher’s translanguaging practice, writing in the 3rd grade classroom and reading in the 9th grade classroom. At another meeting, we explored ways to organize different narratives and developed a structure for each teacher to discuss the relationship between the translanguaging practice and students’ SEL. Then, Deborah and Walny documented the classroom translanguaging practices they implemented between the fall of 2021 and the spring of 2022, with detailed descriptions and instructional artifacts. In their narratives, they discussed their beliefs about the practice and students’ responses to explore the effect of translanguaging on learners’ SEL.

Each case story, including the detailed documentation and discussion of the translanguaging practice in a self-narrative format, was shared through on and off-line discussions. We particularly discussed each teacher’s context of teaching and strategies adopted in relation to their belief and understanding of translanguaging, resulting in multiple drafts of case stories. In this study, our collaborative dialogue was a significant part of this project, as it took place at different stages of the project, including before, during, and after drafting the two case stories through online Zoom meetings and offline comments and suggestions. For example, we planned the project together, read and revised each case story to compare and contrast, and discussed the limitations and implications of the project. The dialogue became a significant source for the teachers to reflect on their experiences and student reactions, helping them reflect on and remember what may have been forgotten. The dialogue also served as a form of peer debriefing to enhance the trustworthiness and the credibility of the analysis [27], by questioning these teachers’ stories and encouraging further exploration. Thus, the case stories in this study reflect our collaborative dialogue, which built on each author’s personal experiences with and perspective toward translanguaging.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Deborah’s Story: Translanguaging as a Collaborative Writing Space

4.1.1. Belief about Translanguaging and Student Learning

Deborah described her identity as a teacher who has always emphasized collaboration with students, forming relationships, and approaching language learning from an asset-based stance that incorporates students’ funds of knowledge [15]. She stressed that translanguaging practices allow her to build upon and value her students’ entire linguistic repertoires, which she believes supports her students’ unique social and emotional needs in a new cultural and linguistic context. Deborah also shared her translanguaging practice through a case study on the use of home language texts in reading instruction [28].

In this case story, Deborah utilized students’ multilingual and multicultural understanding in her 3rd grade writing lessons. By encouraging her students to write in their L1s and engaging in joint collaboration with them, she aimed to acknowledge students’ cultures and communities and to alter the role of the student from learner to teacher to increase their self-confidence and collaboration skills. Deborah stated that adopting a student-first stance by integrating their linguistic resources into official classroom instruction [29] is especially critical for the development of confidence and collaborative skills among young, emergent bilinguals who are exposed to a new linguistic and social environment.

4.1.2. Translanguaging and Co-Ownership of Student Writing

Deborah’s case story focuses on translanguaging writing in the 3rd grade classroom. Deborah views writing as an area of schooling typically dominated by a monolingual perspective. She believes that writing practices need a broader perspective that acknowledges multilingual learners’ existing linguistic and cultural knowledge to advocate for their academic success and personal growth.

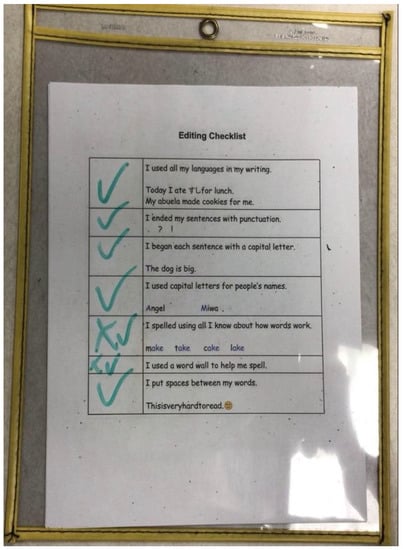

In order to foster a collaborative space that is more inclusive of her students’ full linguistic repertoire, she recently revised an editing checklist to encourage her students to use multilingual writing skills. The changes include utilizing translations in students’ first languages (L1s) and incorporating translanguaging models in the checklist. Figure 1 shows Deborah’s writing checklist in English (also see Appendix A). The checklist includes an item that states, “I used all of my languages in my writing” with example sentences that utilize translanguaging, such as “Today I ate ずし(sushi) for lunch” and “My abuela (grandma) made cookies for me”. Deborah explained that she added the specific item to encourage her students’ use of their multilingual skills in their writing based on a suggestion by [30]. With the checklist item, she aimed to create a space for translanguaging, a space that not only allows but also makes translanguaging a classroom norm for writing practice [31]. By doing so, Deborah acknowledged her students’ multilingual skills and incorporated those skills into her English lessons. She asserted that writing practice based on the checklist enabled her students to recognize and utilize their multilingual skills in the translanguaging space, increasing their confidence and supporting positive attitudes toward their L1s and cultures.

Figure 1.

Writing checklist in English.

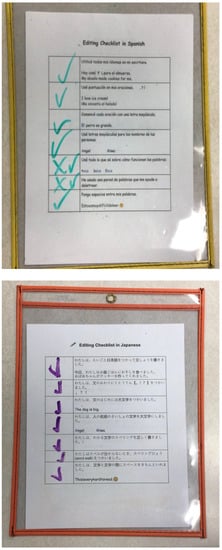

Deborah also created the writing checklist in other languages, such as Spanish and Japanese (see Figure 2), and chose to use them according to the students’ linguistics backgrounds and their proficiency in English. In her case story, Deborah shared her experiences of using the checklists to increase collaboration between two third-grade students, Carlos and Sara, and herself. Carlos and Sara came from Peru and Japan, respectively, and had low intermediate skills in writing in English. The two students were writing journals in their English development lessons.

Figure 2.

Writing checklist in Spanish and Japanese.

When the editing checklists were presented to the two students, Deborah immediately noticed these students’ high energy and engagement as they recognized examples of their languages on the checklists. As they went through and read the checklist together, each of the students began to highlight and annotate the rubric with what was important to them. When reading the first item on the checklist, “I used all of my languages in my writing”, Deborah and the students had an illuminating conversation about being able to use all of their languages in their writing and why they might want to do that. Before writing in her journal, Sara asked if she needed to write in English, and Deborah replied that she could use whichever language made sense for what she wanted to say. She wrote her greeting to Deborah in English and then wrote the rest of her entry in Japanese. When using the checklist to review her writing, Sara checked items that she did in either English or Japanese. For example, she initially did not put a check next to “I used capital letters for names”, but then she remembered that she used capital letters for the name in her greeting. She compared and contrasted the two languages, as she did not check the item, “I put spaces between my words”. She said, “We don’t do that in Japanese”. Deborah believed that this was an example of how the checklist increased the students’ metalinguistic language awareness.

More importantly, the translanguaging practice in the classroom helped the students’ SEL in the areas of confidence and collaboration skills. During a writing practice, Carlos started writing in English and then exclaimed, “I need to use Spanish for this part!” Carlos demonstrated how he made his own language choices by exercising his own agency. The translanguaging practice helped him understand his authority as well as responsibility in his own choices in writing. Sara also showed her increasing authorship/ownership in her writing. After writing her entry entirely in Japanese, Sara offered an explanation in English, so that Deborah could understand it. In the process, Sara and Deborah collaborated in discussing the meanings of Japanese words and expressions and seeking corresponding words and expressions in English. This collaboration increased Sara’s self-confidence, as it put her in the role of teacher with Japanese linguistic knowledge and skills in the collaborative space.

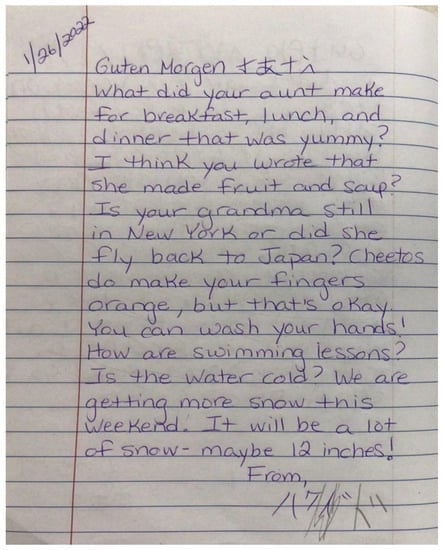

As Sara built up her confidence and ownership in her writing, she asked Deborah to practice writing her name in Chinese characters. When Deborah finished and asked Sara how she did, she said “mas o menos” (more or less, so so), a phrase she had learned in Spanish. Pulling from her linguistic repertoire, the expression that most accurately fit her communicative purposes for conveying that Deborah had done a so-so job of writing her name was the Spanish phrase. Sara then proceeded to show Deborah the mistakes that Deborah had made in writing, positioning herself as the one with expertise. When writing in her journal, she addressed Deborah’s name in Japanese and Deborah adopted Japanese address terms and greetings in her response to Sara’s letter. Sara continued to correct Deborah’s attempt to write her name in Japanese (see Figure 3 at the bottom in pencil).

Figure 3.

Sample of teacher’s journal entry that utilizes translanguaging.

Another example of translanguaging as a collaborative space in Deborah’s classroom was her modeling students’ translanguaging practices using multiple languages, such as Spanish and German (her linguistic background), as well as Japanese (learning from her student). Deborah believed that her students’ translanguaging responses built upon her own translanguaging practice. Deborah modeled translanguaging when she used both German and Japanese in her greeting to Sara (see Figure 3), which was then reciprocated. Sara also shared that her father spoke some German and asked to copy down some German words to take home. When Deborah wrote “¡Hola !” as the greeting in her letter to Carlos, Carlos also responded with “¡Hola Mrs. Howard!” when he wrote back to her. Carlos continued to use Spanish in his journal, in particular when he was expressing excitement about family events, such as his uncle’s birthday and a recent trip. Carlos wrote, “¡Casi ba ser mi Teyo B-day!” (It is almost going to be my uncle’s birthday!) and “My trip fe moooy bien!” (My trip was very good!). Deborah’s translanguaging practice led to a metalinguistic conversation about the different words in Spanish that she and Carlos used for the word lunch in English, including “almuerzo” and “lonche”. Deborah also researched how to write certain words in Japanese and did her best to use them in her journal entries. Placing herself in the role of learner changed the hierarchical power dynamic of the classroom, which led to more opportunities for collaboration between the students and Deborah.

The multilingual writing rubric and the translanguaging writing that Deborah modeled for students moved the act of writing from a monolingual stance to one where translanguaging was valued. These practices resulted in the students opening up their writing to new possibilities and enabling them to engage in collaboration with others with authority in their own writing. The translanguaging in this regard supports multilingual students’ SEL through improving their self-confidence, which enables them to build collaborative relationships with other writers, with shifted roles from learner to teacher.

4.2. Walny’s Story: Translanguaging as Connecting the Dots in Multilingual Texts

4.2.1. Belief about Translanguaging and Student Learning

Walny enacted a translangusing approach in language arts classrooms in high school to help his multilingual learners increase confidence, as well as develop academic English skills. He believed that English language acquisition for his newcomer students is not the focus of the curriculum, as his students’ learning of English is expected to “happen” through the use of English as a medium, rather than as a subject of instruction. He stated that the school curriculum emphasizes students’ standardized test scores and graduation rates and overlooks multilingual learners’ specific language needs. That is, their English proficiency is not strong enough to understand various academic terms and figurative languages in high school language arts classes. Thus, teaching the content in English only does not work well with his students, as the majority of his students have received school instruction in another language, such as Spanish or Haitian Creole, prior to their schooling in the U.S. Thus, he strived to establish a connection between the content received in students’ first languages and the content in English language through translanguaging. Walny witnessed his students’ low confidence and motivation to learn the subject area when they needed to learn beginning English skills or did not understand the lessons, due to their lack of language skills. In his view, focusing on students’ rapid English acquisition to increase test scores and graduation rates may not help them engage in their classroom practice.

In this regard, Walny believed that it is critical to utilize his students’ L1s to help them understand the concepts (the goal of the lessons). He implemented translanguaging pedagogy by incorporating multilingual texts for reading, as well as presenting and prompting multilingual examples during instructional activities for multilingual meaning-making [7]. He asserted that students’ L1s are significant resources in the English language arts classes as those high schoolers have invested in other language(s) for a long time and face challenges developing proficiency in English in a short period of time. He added that encouraging his students’ L1s not only increases their comprehension of the content, but also enhances their self-confidence and motivation. By inviting his students to use all of their languages to engage with the literary texts and develop advanced literacy skills, Walny aimed to create a safe space [23] for multilingual meaning-making processes in the secondary English classroom. Furthermore, he also aimed to expand the space beyond the classroom by sending letters to families in students’ L1s, so that his students and their families can continue to utilize multilingual resources to support these students’ academic and social development.

4.2.2. Translanguaging as a Safe Space for Multilingual Meaning Making

The translanguaging approaches Walny implemented included both classroom-based and family-based strategies. For the former, Walny incorporated the two major languages his students speak, Spanish and French, into his classroom activities when teaching concepts of English literary devices, such as metaphor, simile, and personification. For the latter, he sent letters written in English, Spanish, and Haitian Creole to families concerning what students are learning in each unit with discussion questions and multilingual references.

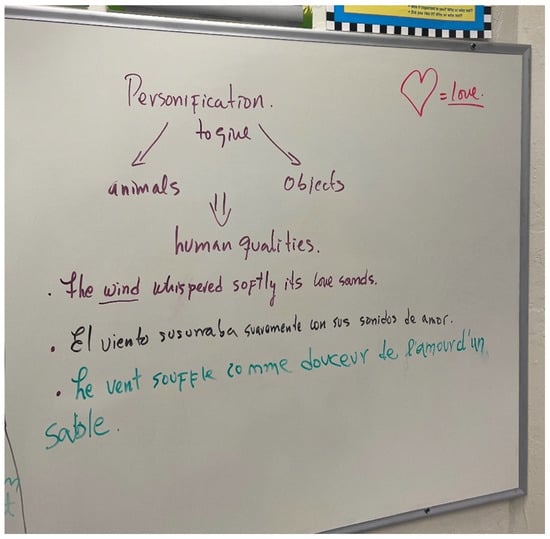

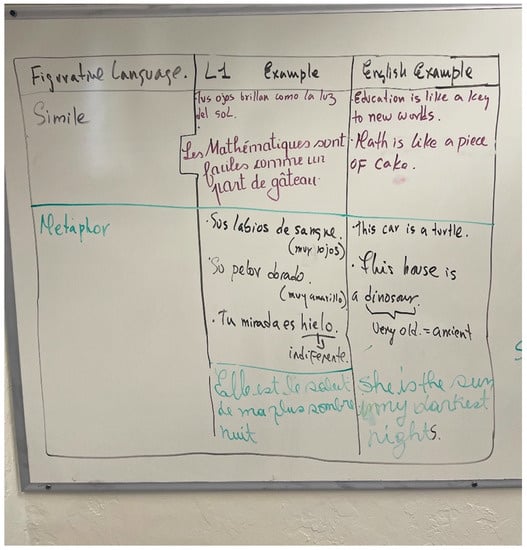

When teaching “The Tempest” by William Shakespeare, Walny used translanguaging at multiple steps, including brainstorming, exemplifying, and the second-read. At the first step, Walny let students explore and build background knowledge on the concept, figurative language, in any language that students speak. He first wrote down the relevant terms on the board (metaphor, simile, etc.) and discussed examples not only in English, but also in Spanish and French (see Figure 4). When he asked students a question, he repeated the same question in Spanish and French (e.g., what are a metaphor and a simile? Que es una metáfora y un simil? Qu’est-ce qu’une métaphore et une comparaison?).

Figure 4.

Translanguaging in figurative language teaching.

Then, students responded variously in their L1s, including in Spanish, “Es una frase sin sentido” (it is a meaningless phrase), “Es una oracion con palabras de diferentes significados” (it is an ambiguous sentence), and in French, “C’est une expression à double sens” (it is an ambiguous sentence). His attention to these responses in students’ L1s prompted student interest and motivation to learn the concept further in English. For the next step, Walny provided examples of metaphors and similes in English and then in Spanish and French. Examples of these included “When my dog died, I cried a river,” “Cuando mi perro murio, llore todo un rio” in Spanish, and “Quand mon chien est mort, j’ai pleuré une rivière” in French. Then, students worked together in a group and discussed examples in their L1s and searched for corresponding examples in English. After their group activity, students shared their work with the entire class.

Figure 5 shows the examples the students presented. The table in the figure includes Spanish examples, such as “Tus ojos brillan como la luz del sol” (your eyes shine like the sun), “Tus labios de sangre” (bloody lips), “Su (de ella) pelo dorado” (her golden hair), and “Tu expresion fria como el hielo” (your expression is cold as ice). Examples in French include “Less Mathematiques sont faciles comme un part de gateau” (Math is like a piece of cake) and “Elle est le soleil dans mes nuits les plus sombres” (she is the sun in my darkest nights). Some of the English examples include “Math is like a piece of cake” and “She is the sun in my darkest nights.” These multilingual examples indicate that students were comparing metaphors in different languages. This activity helped students to increase their metalinguistic awareness of the forms and associated meanings in different cultural contexts. More importantly, Walny pointed out that this enabled his students to increase their motivation to participate in the classroom, as they showed a high level of excitement while working to find examples in different languages.

Figure 5.

Translanguaging in students’ group work on figurative language.

Finally, Walny applied a translanguaging approach to second-read activities, discussing the reading deeply in both English and students’ L1s. When students identified figurative language in the text, they were asked if they would feel the same way as described in the text. Students responded freely in the language with which they felt comfortable. An example of their responses is “Yo creo que el autor usa un simil aqui porque quiere afirmar que Gonzalo estaba sufriendo” in Spanish (I think that the author uses a simile here because he wants to confirm that Gonzalo was suffering). The translanguaging practice here motivated students to read and reflect on the story critically and encouraged them to express their thoughts and feelings about what is in the story in a language that they chose.

Walny reported that student engagement in this activity was notably high, which he believed helped them to learn academic texts in English. He described his prior experiences in teaching the same lesson in English only as very challenging because he could not complete the lesson as scheduled, due to students’ limited engagement and low comprehension. He remembered that students reacted to the same group work with low enthusiasm and motivation without understanding what they needed to do. Their level of anxiety was very high when they engaged in individual work, due to their low comprehension and limited English skills. With the translanguaging approach, the students collaborated with each other in their L1s and English. Their higher motivation and engagement were evident in their attitudes toward language arts classes. Walny described changes in his students’ attitudes toward the course, from “Esto es muy aburrido” (this is really boring) to “Que hay de nuevo en clases?” (what is new in class today?).

Walny’s translanguaging approach also incorporated multilingual texts. For example, when he was teaching The Metamorphosis by Kafka, he consulted with a Spanish teacher and found out “El Hombre que se Convirtio en Perro” (the man who became a dog) is a short text that deals with the same theme. He also found a French version of the same text, “L’homme qui s’est transforme en chien”. Walny added those texts to the reading list and had his students read them to respond to discussion questions. Walny reported that students gained a higher level of comprehension of the unit mentor text from the multilingual texts via their ability to compare the plots and contexts in different languages.

Walny also invited his students’ families to become involved in their children’s education by sending home letters about what students are learning. Walny wrote the letter in English, Spanish, and Haitian Creole (See Appendix B). The letter not only aims to inform families of the school curriculum, but also to encourage them to discuss the lesson topics with their children in their L1s, based on the guided questions included in the letter. Walny observed that students came to his classroom with ideas and knowledge about the lesson, as a result of their discussion with their families in their homes. In some cases, Walny heard how students exhibited their own points, different from those of their families, and argued about their points. This means that the letter generated a chance for the students and their families to discuss lesson topics in their L1s, which increases not only these students’ classroom participation, but also their self-confidence and self-awareness about their L1s and literary work in the languages. In this regard, translanguaging in Walny’s classroom is a space in which students connect multilingual stories in their meaning-making process [7]. In the process, translanguaging becomes a significant resource for his students’ development of confidence and motivation to learn and transform themselves.

5. Conclusions and Implications

This study explored two teachers’ translanguaging approaches applied to literacy activities in the 3rd and 9th grade classrooms, respectively, in support of their multilingual learners’ SEL. By encouraging and advocating for students’ use of their entire linguistic repertoire for their academic success and personal growth, the two teachers integrated these students’ SEL as a significant goal for their teaching. Deborah in her 3rd grade classroom created and utilized multilingual writing checklists to encourage students’ use of their L1s, as well as English, in their writing practices. By doing so, she enacted translanguaging as a collaborative space in which students could exhibit higher authority and confidence in their writing in their collaboration with their teacher. Walny also implemented translanguaging approaches to help students understand literary concepts and key aspects of English literature, as well as increase communication with their families in their home languages. Translanguaging in Walny’s classroom became a space for connecting the multilingual texts for the students’ critical understanding of English texts, and increasing their engagement with the text, the teacher, and their peers. In these two case stories, there are no clear boundaries between students’ learning of social and emotional skills and academic skills, but the development of those skills is “weaved” tightly together to reinforce one another. The results demonstrate that the translanguaging pedagogy by the two teachers supports multilingual learners’ SEL, and thus provides them with a great potential for their academic development and personal transformation.

The results also point out that for these two teachers’ successful integration of SEL into their teaching, their effort to create a safe and caring space for multilingual learners’ creative linguistic practices and associated multilingual identities was key. This, in turn, generated critical opportunities for these students’ navigation and negotiation of various linguistic and social means for their academic development. This means that it is critical for teachers to pay attention to students’ divergent needs and backgrounds to develop specific strategies in support of their students’ SEL. As the case stories demonstrated, translanguaging is a successful way to support multilingual learners’ SEL, but this strategy may not work with other groups of students in school. We suggest that more attention must be paid to teacher candidates’ understanding of students’ social and emotional needs and their development of specific strategies that create emotionally secure and supportive classroom environments, conducive to their SEL. Specifically, in language teacher education, more discussion should focus on how to advocate for multilingual learners’ emotional well-being by developing strategies that promote the additive view of their multilingual and multicultural experiences.

While this study has a limitation as it only focused on two teachers’ case stories, the examples presented in each case story, such as multilingual writing checklists, letters for families written in various languages, and relevant pedagogical activities, can be applicable to a range of teaching contexts in which teachers interact with multilingual students and emergent bilinguals. Additionally, this study explored the case stories from the perspectives of teachers. Further studies may incorporate students’ perspectives on their emotional and social challenges, so that their emotional well-being becomes part of the school curriculum and instruction.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.S.; Methodology, J.S.; Investigation, J.S., D.H. and W.O.-A.; Data Curation, D.H. and W.O.-A.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, J.S., D.H. and W.O.-A.; Writing—Review & Editing, J.S. and D.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Editing Checklist

| I used all my languages in my writing. | |||

| Today I ate すし for lunch. My abuela made cookies for me. | |||

| I ended my sentences with punctuation. | |||

| . | ? | ! | |

| I began each sentence with a capital letter. | |||

| The dog is big. | |||

| I used capital letters for people’s names. | |||

| Angel | Miwa | ||

| I spelled using all I know about how words work. | |||

| make | take | cake | lake |

| I used a word wall to help me spell. | |||

| I put spaces between my words. | |||

| Thisisveryhardtoread.🙁 | |||

Appendix B. Home Connection Letter (Spanish Sample)

Conexión con el hogar

Lo más destacado de la Unidad 4: Virtud y venganza

Estimada familia:

En esta unidad, los estudiantes aprenderán sobre el perdón, considerando situaciones en las que la gente suele buscar venganza o redimirse. Los estudiantes leerán variostextos altiempo que comentan la Pregunta Esencial de la Unidad.

PREGUNTA ESENCIAL

Los estudiantes trabajarán con todo el grupo de clase, en grupos pequeños y de forma independiente para responder a la pregunta: ¿Qué nos lleva a perdonar? Dé a su hijo(a) la oportunidad de continuar la conversación en casa.

| HÁBLELO CON SU HIJO(A) |

|

TÍTULOS, AUTORES Y GÉNEROS DE LAS SELECCIONES DE LA UNIDAD 4

| La Tempestad | William Shakespeare | Obra de teatro |

| “En el Jardín de los Espejos Quebrados, Caliban logra ver un destello de su imagen” | Virgil Suárez | Poesía |

| “Caliban” | J. P. Dancing Bear | Poesía |

Home Connection Letter (Haitian Creole Sample)

Koneksyon Lakay

Pwen Esansyèl nan Inite 4: Vèti ak Tire Revanj

Chè Fanmi,

Nan inite sila a, elèv yo pral aprann sou padon, konsidere sitiyasyon kote moun chache tire revanj oswa ofri amannman. Elèv yo ap li yon varyete tèks pandan y ap diskite sou Kesyon Esansyèl inite a.

KESYON ESANSYÈL

Kòm yon klas, an ti gwoup, ak endepandamman, elèv yo ap travay pou reponn kesyon Ki sa ki motive nou padone? Bay elèv ou opòtinite pou kontinye diskisyon an lakay ou.

| PALE AK ELÈV OU |

|

INITE 4 SELEKSYON TIT, OTÈ, JAN

| The Tempest | William Shakespeare | Teyat |

| “En el Jardín de los Espejos Quebrados, Caliban Catches a Glimpse of His Reflection” | Virgil Suárez | Pwezi |

| “Caliban” | J. P. Dancing Bear | Pwezi |

Home Connection Letter (English Sample)

Home Connection

Highlights of Unit 4: Virtue and Vengeance

Dear Family,

In this unit, students will learn about forgiveness, considering situations in which people seek vengeance or offer amends. Students will read a variety of texts as they discuss the Essential Question for the unit.

ESSENTIAL QUESTION

As a class, in small groups, and independently, students will work to answer the question what motivates us to forgive? Give your kids the opportunity to continue the discussion at home.

| TALK IT OVER WITH YOUR KIDS |

|

UNIT 4 SELECTION TITLES, AUTHORS, GENRES

| The Tempest | William Shakespeare | Drama |

| “En el Jardín de los Espejos Quebrados, Caliban Catches a Glimpse of His Reflection” | Virgil Suárez | Poetry |

| “Caliban” | J. P. Dancing Bear | Poetry |

References

- CASEL. What Is SEL? 2019. Available online: https://casel.org/what-is-sel/ (accessed on 27 January 2022).

- Zins, J.E.; Elias, M.J. Social and emotional learning: Promoting the development of all students. J. Educ. Psychol. Consult. 2007, 17, 233–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, M.J.; Zins, J.E.; Weissberg, R.P. Promoting Social and Emotional Learning: Guidelines for Educators; Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development: Alexandria, VA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz, E.K.; Horwitz, M.B.; Cope, J. Foreign language classroom anxiety. Mod. Lang. J. 1986, 70, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacIntyre, P.D.; Gardner, G.C. The subtle effects of language anxiety on cognitive processing in the second language. Lang. Learn. 1994, 44, 283–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, O. Bilingual Education in the 21st Century: A Global Perspective; Wiley/Blackwell: Malden, MA, USA; Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Michael, A.; Andrade, N.; Bartlett, L. Figuring “success” in a bilingual high school. Urban Rev. 2007, 39, 167–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, O.; Li, W. Translanguaging: Language, Bilingualism and Education; Palgrave Macmillan: Abingdon, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). English Language Learner (ELL) Students Enrolled in Public Elementary and Secondary Schools, by State: Selected Years, Fall 2000 through Fall 2018. 2020. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d20/tables/dt20_204.20.asp (accessed on 27 January 2022).

- Williams, C. Arfarniad o Ddulliau Dysgu ac Addysgu yng Nghyd-Destun Addysg Uwchradd Ddwyieithog. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Wales, Bangor, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Blackledge, A.; Creese, A. (Eds.) Heteroglossia as Practice and Pedagogy; Springer: Dordrecht, Holland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Canagarajah, S. Codemeshing in academic writing: Identifying teachable strategies of translanguaging. Mod. Lang. J. 2011, 95, 401–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W. Moment analysis and translanguaging space: Discursive construction of identities by multilingual Chinese youth in Britain. J. Pragmat. 2011, 43, 1222–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, D.; Alim, H.S. (Eds.) Culturally Sustaining Pedagogies. Teaching and Learning for Justice in a Changing World; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- González, N.; Moll, L.; Amanti, C. (Eds.) Funds of Knowledge: Theorizing Practices in Households, Communities and Classrooms; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ladson-Billings, G. The (r)evolution will not be standardized: Teacher education, hip hop pedagogy, and culturally relevant pedagogy 2.0. In Culturally Sustaining Pedagogies: Teaching and Learning for Justice in a Changing World; Paris, D., Alim, H.S., Eds.; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 141–156. [Google Scholar]

- Ayers, W.; Quinn, T.; Stovall, D. (Eds.) Handbook of Social Justice Education; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Back, M.; Han, M.; Weng, S. Emotional scaffolding for emergent multilingual learners through translanguaging: Case stories. Lang. Educ. 2020, 34, 387–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Krashen, S.D. The Input Hypothesis; Longman: London, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- MacIntyre, P.D.; Serroul, A. Motivation on a per-second timescale: Examining approach-avoidance motivation during L2 task performance. In Motivational Dynamics in Language Learning; Dornyei, Z., MacIntyre, P.D., Henry, A., Eds.; Multilingual Matters: Bristol, UK, 2015; pp. 109–138. [Google Scholar]

- Adamson, J.; Coulson, D. Translanguaging in English academic writing preparation. Int. J. Pedagog. Learn. 2015, 10, 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsokalidou, R.; Skourtou, E. Translanguaging as a culturally sustaining pedagogical approach: Bi/multilingual educators’ perspectives. In Inclusion, Education and Translanguaging: How to Promote Social Justice in (Teacher) Education? Panagiotopoulou, J.A., Reosen, L., Strzykala, J., Eds.; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2020; pp. 219–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, M.A.; Hansen-Thomas, H. Sanctioning a space for translanguaging in the secondary English class: A case of a transnational youth. Res. Teach. Engl. 2016, 50, 450–472. [Google Scholar]

- Maslin-Ostrowski, P.; Ackerman, R. Case Story. In Encyclopedia of Educational Leadership and Administration; English, F., Ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2006; p. 106. [Google Scholar]

- Connelly, F.M.; Clandinin, D.J. Telling teaching stories. Teach. Educ. Q. 1994, 21, 145–158. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 4th ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G. Naturalistic Inquiry; Sage Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, D. Empowering reading with home language texts. Read. Teach. 2022, 75, 649–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, O.; Kleyn, T. Translanguaging with Multilingual Students: Learning from Classroom Moments; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- España, C.; Herrera, L.Y. Reading and Writing in Community: Applying a Texts, Topic, and Translanguaging Approach to Teaching Multilingual Learners. In Proceedings of the the International Literacy Association (ILA) 2021 Conference, Indianapolis, IN, USA, 12–17 October 2021. Presentation. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, S.M.; Jiménez, R.T.; Pray, L.; Pacheco, M.B. Scaffolding to make translanguaging a classroom norm. TESOL J. 2019, 10, e00361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).