1. Introduction

As a key prediction of Einstein’s general theory of relativity, gravitational waves have opened up a completely new approach to exploring and understanding the universe. However, due to seismic noise and other unavoidable disturbances, low-frequency gravitational wave signals (mHz–Hz) cannot be detected on the ground, which is precisely the part of the spectrum that holds the greatest research value [

1]. To enable in-depth exploration of the universe via low-frequency gravitational waves, several space-based gravitational wave detection missions have been proposed and developed, including LISA [

2], TianQin [

3], and Taiji [

4]. All three missions are designed to detect gravitational waves in the frequency band from 0.1 mHz to 1 Hz [

5].

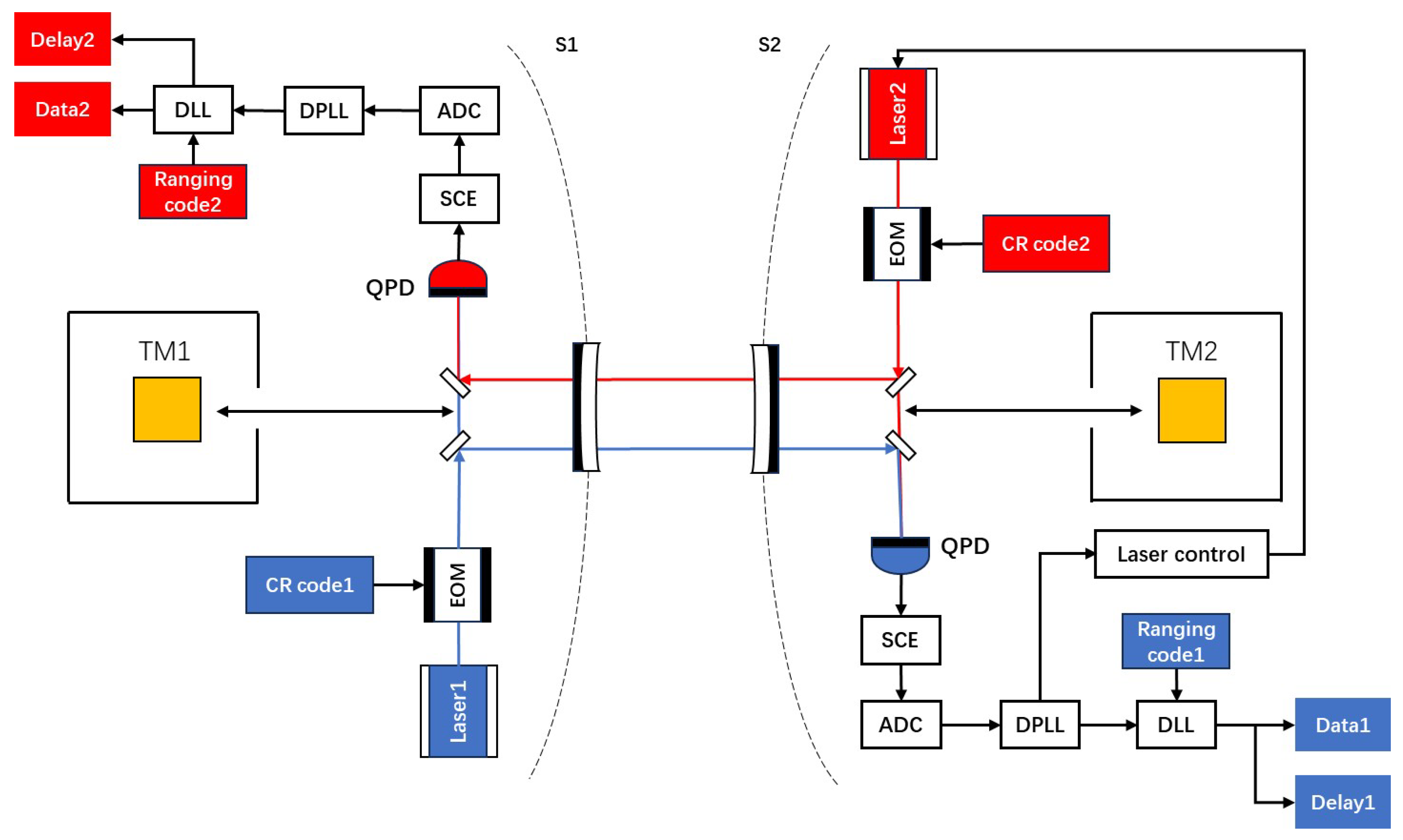

In the gravitational wave detection constellations involved in these missions, each satellite contains a reference object in a fully free-floating state, known as a test mass. During detection, gravitational wave effects are measured by precisely monitoring the displacement between the satellite and the test mass. At the same time, high-precision laser interferometry is employed to record extremely subtle changes in the distance between test masses, thereby extracting information related to gravitational wave signals [

6]. However, the relative orbital motion of the satellites leads to variations in the interferometer arm lengths, resulting in unequal arms. In such laser interferometers, laser frequency noise constitutes a dominant noise source, whose residual amplitude is proportional to the arm-length mismatch. To suppress the frequency noise arising from these variations, Time Delay Interferometry (TDI) is employed. This technique processes the measured data through appropriate time delays and linear combinations, effectively reconstructing a virtual equal-arm interferometer and achieving com-mon-mode suppression of laser frequency noise [

7,

8]. The implementation of TDI during data post-processing requires precise measurement of the absolute inter-satellite distances [

9,

10]. Meanwhile, to enable the transmission and backup of scientific data, inter-satellite laser communication based on Pseudo-Random Noise (PRN) codes is implemented on the same laser interferometry link [

11].

In space-based gravitational wave detection, to minimize the impact on inter-satellite laser interferometric measurements, the functions of inter-satellite laser communication and ranging are integrated into the same laser interferometry link. The communication and ranging signals are phase-modulated onto the laser carrier with a low modulation index. After ultra-long-distance transmission between satellites, the receiving terminal performs demodulation, acquisition, and tracking of these signals, thereby recovering the communication data and the ranging delay [

12]. The acquisition of the communication and ranging signals is the key to achieving successful inter-satellite communication and ranging. However, this process faces substantial challenges due to limited bandwidth, weak light conditions with low modulation indices, and ultra-long transmission distances in space-based gravitational wave detection [

13,

14]. These influences lead to a significant reduction of the received signal’s signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), consequently decreasing the acquisition performance of the communication and ranging signals and even leading to acquisition failures. Therefore, identifying the main factors that influence the acquisition performance of the inter-satellite communication and ranging signals in space-based gravitational wave missions, and establishing accurate mathematical models to describe the quantitative relationship between acquisition performance and these influencing factors, represents critical research questions that must be addressed.

In terms of current space gravitational wave communication and ranging, the LISA project [

11] has achieved absolute distance measurements with an accuracy of 2.44 cm using BPSK modulation with a modulation index of 0.1 rad and a PRN code rate of 1.25 MHz. It also demonstrates inter-satellite communication at 78.125 kbps with a bit error rate below

. To further mitigate the impact of communication and ranging signals on laser interferometry, as well as the high-pass filtering effect of the phase-locked loop error signal, the LISA project [

15] proposes using BOC modulation for inter-satellite ranging and communication, enabling sub-meter ranging accuracy. The Taiji project [

16] initially employs a modulation index of 0.4 rad and a PRN code rate of 1.25 MHz, achieving a data rate of 19.5 kbps with a bit error rate below

. Subsequently, it has reduced the modulation index to 0.1 rad [

17], resulting in an absolute distance measurement accuracy of 82.1 cm and a root-mean-square error of 9.14 cm. The TianQin project [

9] has achieved an absolute distance measurement accuracy of 1.2 m with a modulation index of 0.1 rad and a PRN code rate of 3.125 MHz, which meets the ranging requirements for TDI [

18]. Due to the high CNR of the beat note signal, the TianQin project [

19] utilizes a low modulation index of

. Simulation results have verified an inter-satellite communication data rate of 62.5 kbps with a bit error rate below

. The communication and ranging signal schemes and system parameters of these missions are summarized in

Table 1.

Current research on communication and ranging for space-based gravitational wave detection shows that the signals employed in such missions primarily adopt BPSK and BOC modulation schemes. Intuitively, the modulation index is a key factor influencing the acquisition performance of communication and ranging signals. Moreover, the communication rate also plays an important role, as it affects the acquisition of PRN codes through the spreading factor. In addition, the design of PRN codes—such as code rate and code length—can further influence acquisition performance. However, due to the absence of accurate mathematical models that describe these relationships, it remains challenging for current studies to quantitatively analyze the acquisition performance of communication and ranging signals.

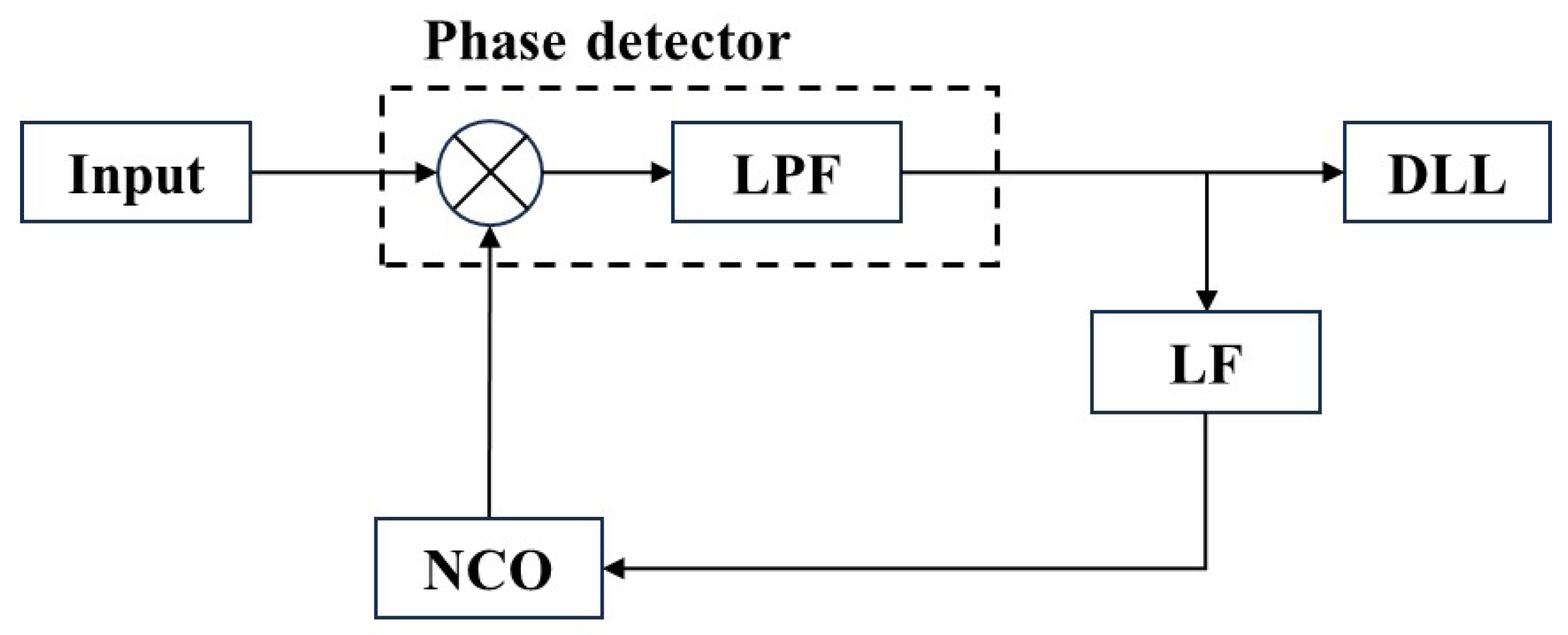

Therefore, the acquisition of ranging and communication signals for space-based gravitational wave detection constitutes a signal synchronization problem under multiple parameter constraints. Conventional satellite navigation signal acquisition typically employs suppressed-carrier synchronization, allocating all signal power to communication and ranging. It faces a high-dynamic, two-dimensional search problem due to high-velocity satellite motion, namely, the unknown and rapidly varying Doppler shift and code phase. Thus, it commonly employs coupled carrier and code tracking loops for joint acquisition [

20,

21]. However, in space gravitational wave detection, the scientific measurement demands phase stability of the main laser carrier at the picometer level, leaving only 1% of the signal power available for communication and ranging. To minimize the impact of the code loop on the phase measurement of the carrier loop and enable reliable acquisition of the communication and ranging signal, in summary, this study adopted a decoupled architecture described as “DPLL-first carrier locking with Doppler cancellation, followed by DLL-only code-phase acquisition.” Based on this architecture, this study focused on analyzing the acquisition performance of the communication and ranging signals in the gravitational wave detection mission. This study was organized as follows. First, a modulation and demodulation model for the communication and ranging signals was established (

Section 2). Second, an acquisition performance model was developed and the key factors influencing acquisition were identified (

Section 3). Finally, experimental verification, analysis of the factors influencing acquisition performance, and optimization of the modulation index were carried out (

Section 4).

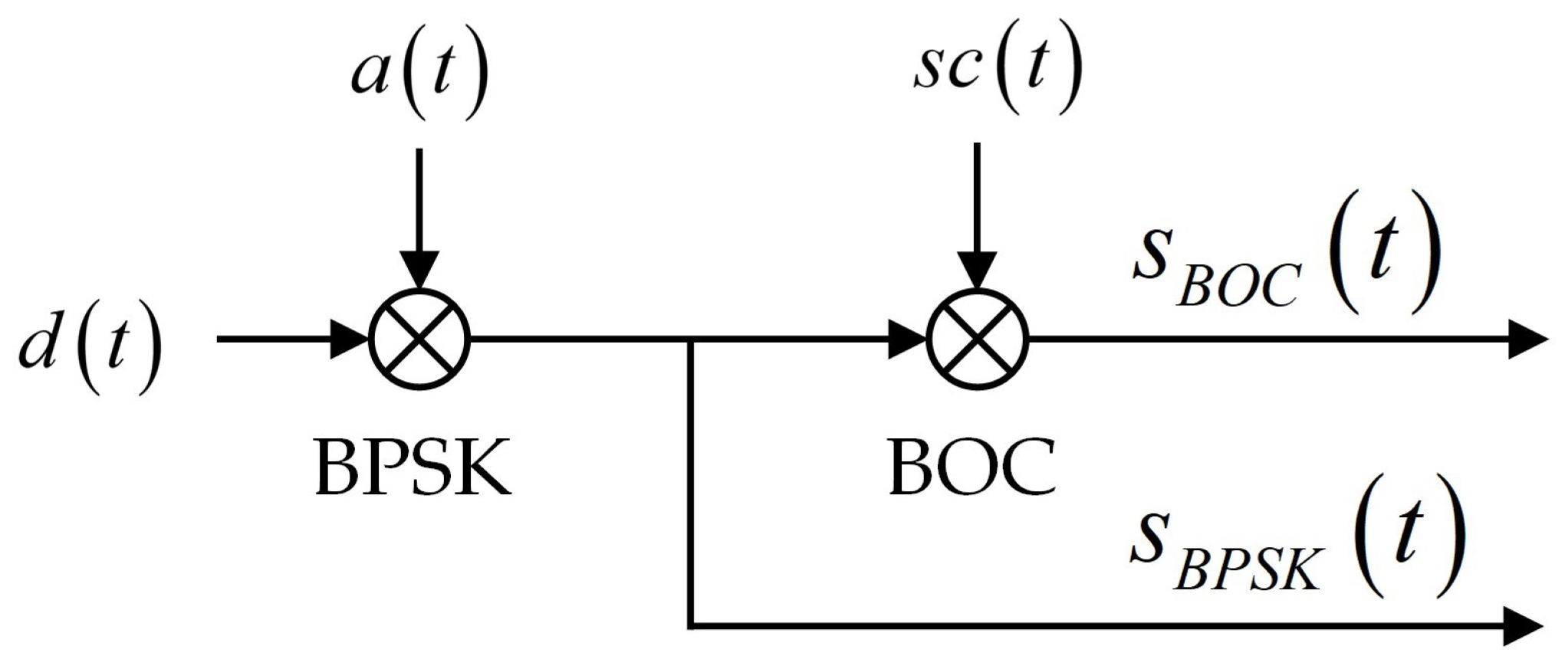

3. Acquisition Performance Modeling

After the DPLL extracts the communication and ranging codes from the main beat signal, the received communication and ranging codes are correlated with the local PRN code in the DLL. This correlation operation completes the acquisition and tracking processes, thereby enabling absolute distance measurement and data communication. This chapter models the acquisition performance based on the communication ranging signal model. This process involves setting the acquisition step size, calculating the acquisition detection metric through the acquisition process for different signals, and, finally, establishing the acquisition performance model. Currently, the communication and ranging signals for space-based gravitational wave detection utilize two modulation schemes: BPSK baseband signals and BOC baseband signals. Their acquisition performance models were thus developed.

3.1. Modeling of Acquisition Step Size

During the acquisition process, the acquisition step size determines the selection of both the maximum acquisition time and the acquisition threshold. Therefore, this chapter begins by describing the modeling of the acquisition step size.

Assuming the acquisition process begins scanning from the position furthest from the correlation peak, the acquisition time is given by

where

L represents the PRN code length,

denotes the PRN code chip period, and

is the acquisition step size.

Due to the relative motion between satellites, the actual delay of the PRN code changes during the acquisition process. The maximum variation is

where

is the maximum relative velocity between satellites and

c is the speed of light.

It is optimal that during the acquisition period, the delay variation does not exceed the range of the tracking phase detector. Since the width of the tracking phase detector’s range typically matches the acquisition step size, the following relationship can be established:

From this, the minimum value for the acquisition step size

can be derived:

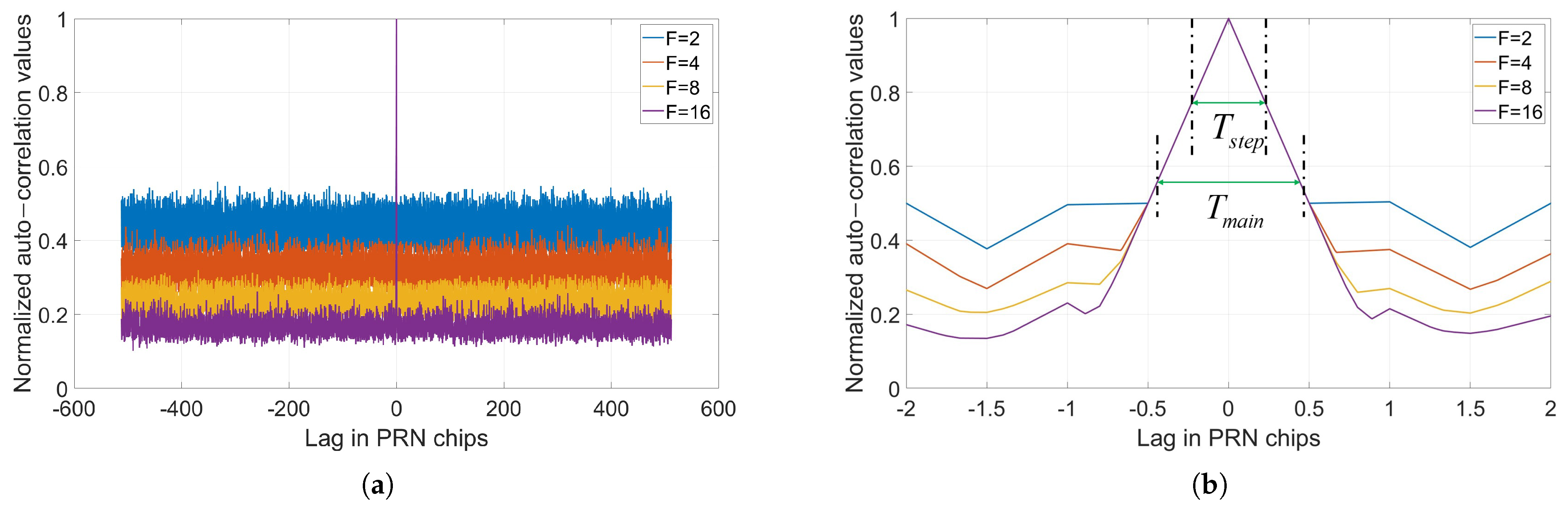

The acquisition process is estimated based on the most conservative scenario, considering that the maximum uncertainty requiring scanning when the communication and ranging codes are synchronized is symmetric about the peak of the autocorrelation function. The total symmetric length is the acquisition step size .

Given that the minimum value within the main peak of the autocorrelation function

must exceed all sidelobe values, and since the sidelobe magnitude is strongly correlated with (and increases as) the spreading factor

F decreases, the size of the main peak

therefore needed to be designed according to the specific spreading factor

F, as illustrated in

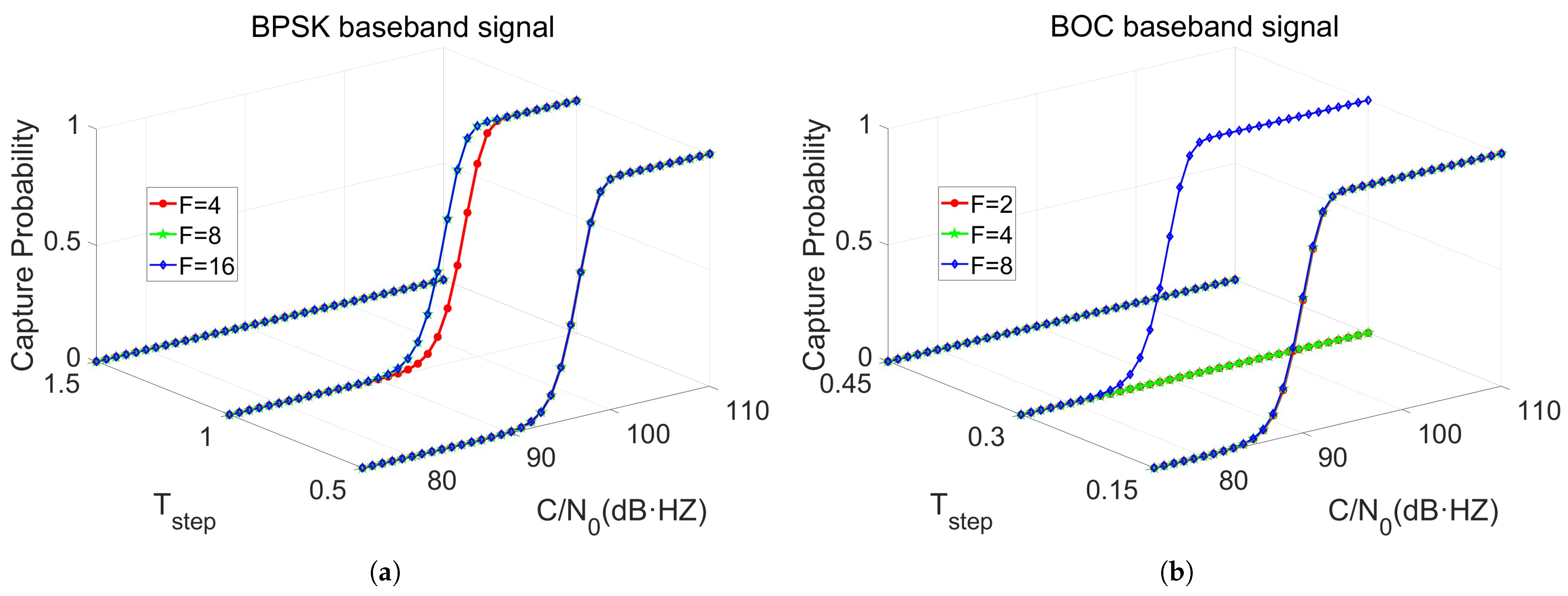

Figure 4.

The acquisition step size

could not exceed the width of the main lobe of the autocorrelation function

. Therefore, the valid range for the acquisition step size was

3.2. Acquisition Performance Modeling for BPSK Baseband Signals

Once the acquisition step size was determined, the acquisition detection metric could be calculated based on the acquisition process. Subsequently, the acquisition performance model could be established according to the acquisition decision criteria.

3.2.1. Acquisition Process

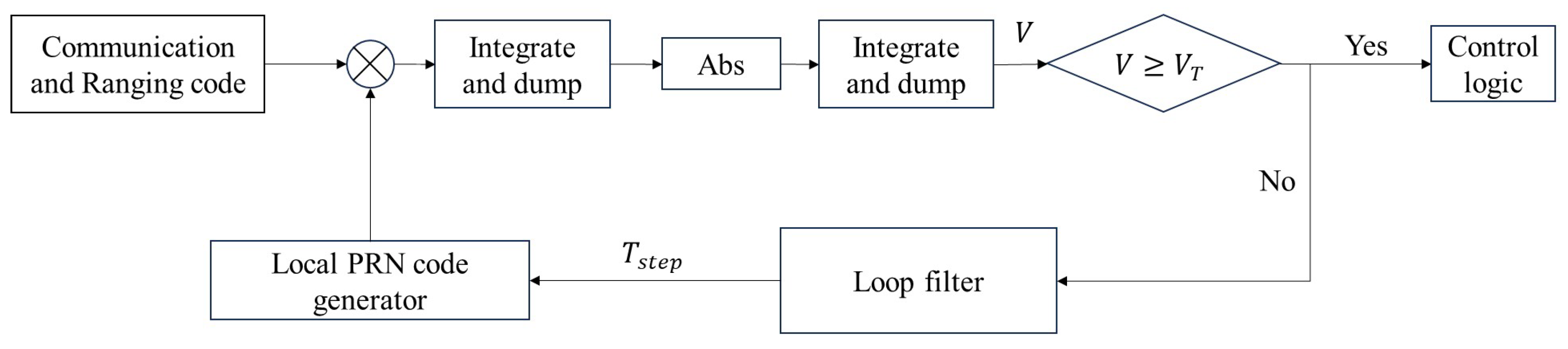

Considering hardware resource constraints, the time-domain serial acquisition process was employed for the BPSK baseband signal in the DLL. The corresponding processing flow is illustrated in

Figure 5.

The received communication and ranging signal and the local PRN code first undergo coherent integration over a duration equal to the data code period. The absolute value of the resulting output is then computed, followed by noncoherent integration over the PRN code period to obtain the acquisition detection metric, denoted as V. If the acquisition detection metric V exceeds a predefined acquisition threshold , the process is considered successfully acquired. Otherwise, the local PRN code is shifted by the acquisition step size , and the process is repeated until successful acquisition is achieved.

3.2.2. Acquisition Detection Metric

The data code is inherently a random signal. To facilitate quantitative analysis of the acquisition detection metric, this study analyzes the scenario where the data code is assumed to be an all-ones sequence. Based on Equations (

4) and (

14), the BPSK baseband signal input to the DLL is expressed as

For notational convenience, the noise input to the DLL can be rewritten as

, which is AWGN with zero mean and a variance of

(given by Equation (

15)).

The local PRN code generated by the local code generator within the DLL is expressed as

where

is the local PRN code sequence of length

L, taking values of +1 or −1.

The acquisition detection metric

V is calculated as

where

represents the autocorrelation value of the PRN codes over one data code length and

denotes the accumulated value of the noise-correlated PRN code over the same interval.

3.2.3. Acquisition Decision Analysis

Based on the preceding analysis, this study considers the signal to be synchronized when the acquisition detection metric V is greater than or equal to the acquisition threshold . Otherwise, it is regarded as not synchronized.

An analysis is conducted for both synchronized and non-synchronized states of the BPSK baseband signal. Let denote the hypothesis that the BPSK baseband signal is synchronized and denote the hypothesis that it is not synchronized. If the acquisition threshold is set too low when the signal is not synchronized, this will lead to a false alarm. Conversely, if the threshold is set too high when the signal is synchronized, this will result in a missed detection. The acquisition threshold value is first calculated based on the required false alarm probability . Subsequently, the detection probability is derived using this threshold. The resulting detection probability under a fixed false alarm probability defines the acquisition performance.

This study considered the most conservative scenario. When synchronized, the acquisition detection metric V was assumed to be equal to the acquisition threshold . When not synchronized, the acquisition detection metric V was assumed to be the maximum possible value that was still less than the acquisition threshold .

The probability distribution of the acquisition detection metric

V was then analyzed. For

, its mean and variance were, respectively,

Since

follows a normal distribution,

also follows a normal distribution. For

, this follows a folded normal distribution. By the central limit theorem,

can be approximated as normally distributed. Its mean and variance are given by (see

Appendix A)

where

represents the error function, defined as

Its probability density function is given by

When the BPSK baseband signal is not synchronized, the mean and variance of

are

and

, respectively, where the value of

is taken as the average over all non-synchronized cases. A false alarm is considered to occur when the acquisition detection metric

V is greater than or equal to the acquisition threshold

. Therefore, the false alarm probability is

where

represents the complementary error function, defined as

The acquisition threshold

can be obtained as

where

represents the inverse function of the complementary error function, defined as

When the BPSK baseband signal is synchronized, the mean and variance of

are

and

, respectively, where the value of

is taken as the average over all synchronized cases. The detection probability is thus

In summary, the acquisition probability for the BPSK baseband signal depends on the PRN code length L, the sampling factor N, the modulation index , the CNR of the primary beat note signal input to the DPLL, the spreading factor F, the acquisition step size , the DPLL input noise bandwidth . Based on the parameters mentioned above, the acquisition threshold can first be calculated. This threshold is then used to compute the acquisition probability . When the acquisition probability reaches 1, the corresponding threshold value can be applied to the practical acquisition process for BPSK baseband signals in communication and ranging.

3.3. Acquisition Performance Modeling for BOC Baseband Signals

3.3.1. Acquisition Process

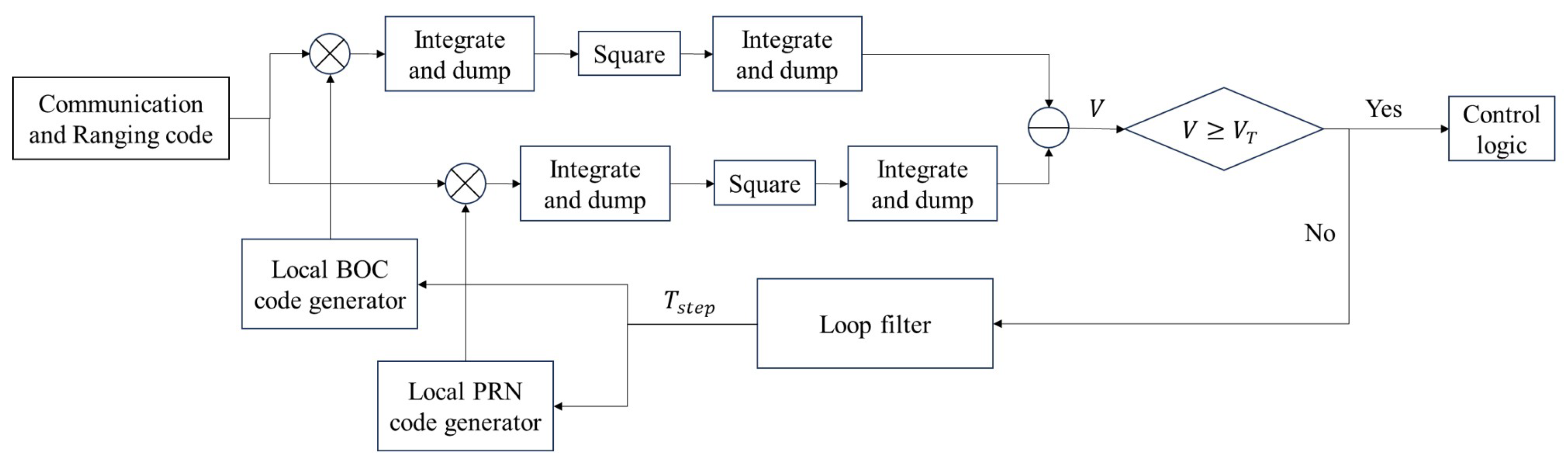

For the

signal, this study employs the Autocorrelation Side-Peak Cancellation Technique (ASPeCT) to eliminate the secondary peaks present in the autocorrelation function of the BOC baseband signal. The fundamental principle of the ASPeCT is to use a combined operation of the BOC code autocorrelation function and the BOC/PRN code cross-correlation function to achieve side-peak cancellation. The process is expressed as follows:

where

represents the autocorrelation function of the BOC code and

denotes the cross-correlation function between the BOC code and the PRN code.

The ASPeCT is implemented in the DLL for the acquisition of the BOC baseband signal. The fundamental workflow is illustrated in

Figure 6.

The received communication and ranging signal is separately correlated with the local BOC code and the local PRN code, performing coherent integration over a duration equal to the data code period. The results of this integration are then squared. Subsequently, non-coherent integration is performed over the PRN code period on the squared results to yield the acquisition detection metric V. If the acquisition detection metric V exceeds a pre-defined acquisition threshold , the process is deemed successfully acquired. Otherwise, both the local BOC code and the local PRN code are shifted by the acquisition step size , and the process iterates until successful acquisition is achieved.

3.3.2. Acquisition Detection Metric

Following the same approach as for the BPSK baseband signal, the scenario where the data code is an all-ones sequence is analyzed. According to Equations (

6) and (

14), the BOC baseband signal input to the DLL is expressed as

The local BOC code generated by the local BOC code generator and the local PRN code generated by the local PRN code generator in the DLL are respectively expressed as

Using the ASPeCT for acquisition, the acquisition detection metric

V is calculated as

where

represents the BOC code autocorrelation value over one data code length,

denotes the accumulated value correlated with the BOC code over the same interval,

represents the BOC-PRN code cross-correlation value over one data code length, and

denotes the accumulated value correlated with the PRN code over the same interval.

3.3.3. Acquisition Decision Analysis

The acquisition decision process for the BOC signal follows the same logical procedure as detailed for the BPSK baseband signal and will not be repeated here. The probability distribution of the acquisition detection metric

V is now analyzed. For

, its mean and variance are, respectively,

Since

follow normal distributions,

also follows normal distributions. For

, this follows a scaled non-central chi-square distribution. Its mean and variance are, respectively,

Similarly, for

, this also follows a scaled non-central chi-square distribution. Its mean and variance are, respectively,

The probability density function of

is

When the BOC baseband signal is not synchronized, the mean and variance of

are

and

, respectively. Here, the values of

and

are taken as their averages over all non-synchronized cases. A false alarm occurs when the acquisition detection metric

V is greater than or equal to the threshold

. Thus, the false alarm probability is

The acquisition threshold

is given by

When the BOC baseband signal is synchronized, the mean and variance of

are

and

, respectively, where

and

are taken as their averages over all synchronized cases. The detection probability is

In summary, the acquisition probability for the BOC baseband signal depends on the PRN code length L, the sampling factor N, the modulation index , the CNR of the primary beat note signal input to the DPLL, the spreading factor F, the acquisition step size , and the DPLL input noise bandwidth . Based on the parameters mentioned above, the acquisition threshold can first be calculated. This threshold is then used to compute the acquisition probability . When the acquisition probability reaches 1, the corresponding threshold value can be applied to the practical acquisition process for BOC baseband signals in communication and ranging.

5. Discussion

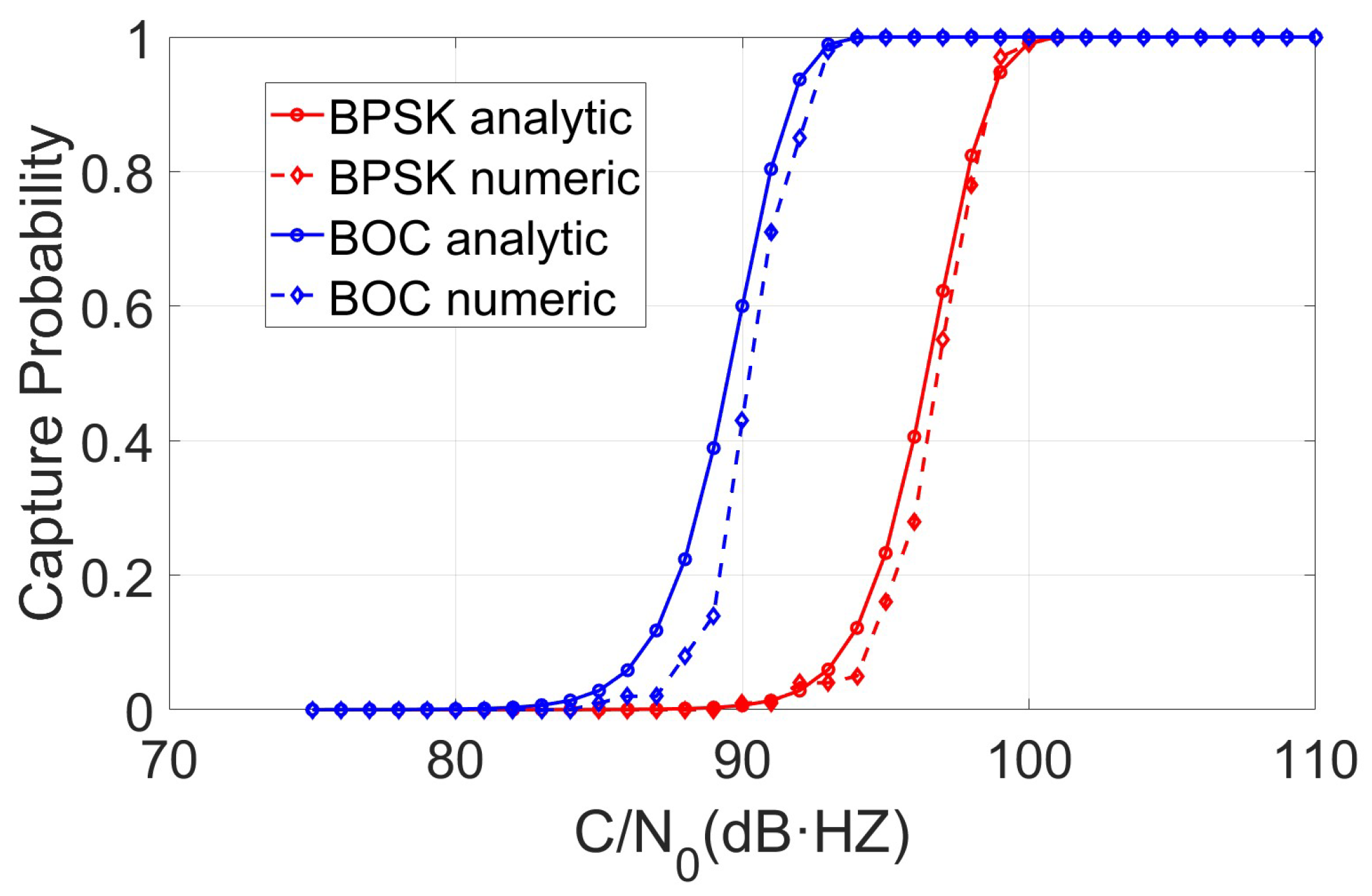

Achieving ranging and communication using only 1% optical power on the same laser interferometry measurement link poses a significant challenge in space-based gravitational wave detection. In order to achieve the correct acquisition of communication and ranging signals, this study established a comprehensive signal-level communication and ranging mathematical model based on the principle of laser interferometry, including transmitter and receiver subsystems. Subsequently, acquisition performance models were developed for both BPSK and BOC baseband signals, incorporating the acquisition step size, acquisition process, acquisition detection metric, and acquisition decision criteria. The key factors influencing acquisition performance were identified, including the PRN code length, sampling factor, modulation index, CNR of the primary beat note signal input to the DPLL, spreading factor, acquisition step size, and the DPLL input noise bandwidth. Alternatively, the acquisition threshold could be directly derived from the these parameters for use in acquiring communication and ranging signals.

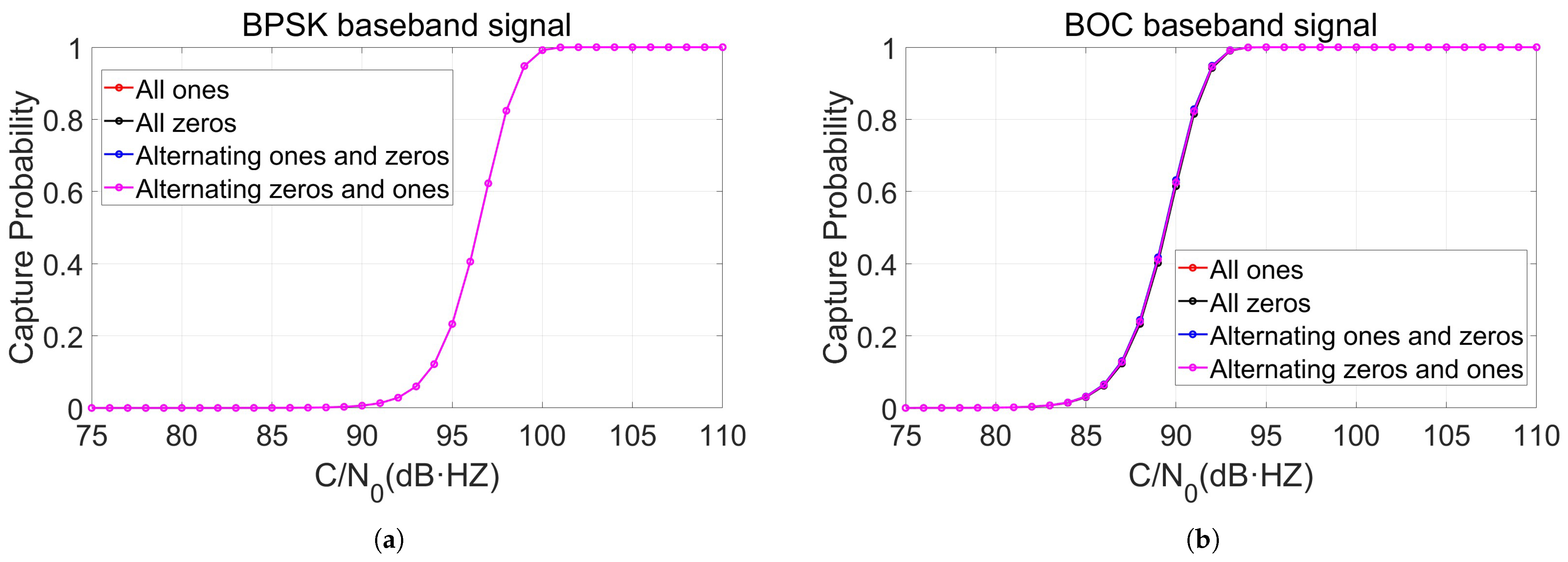

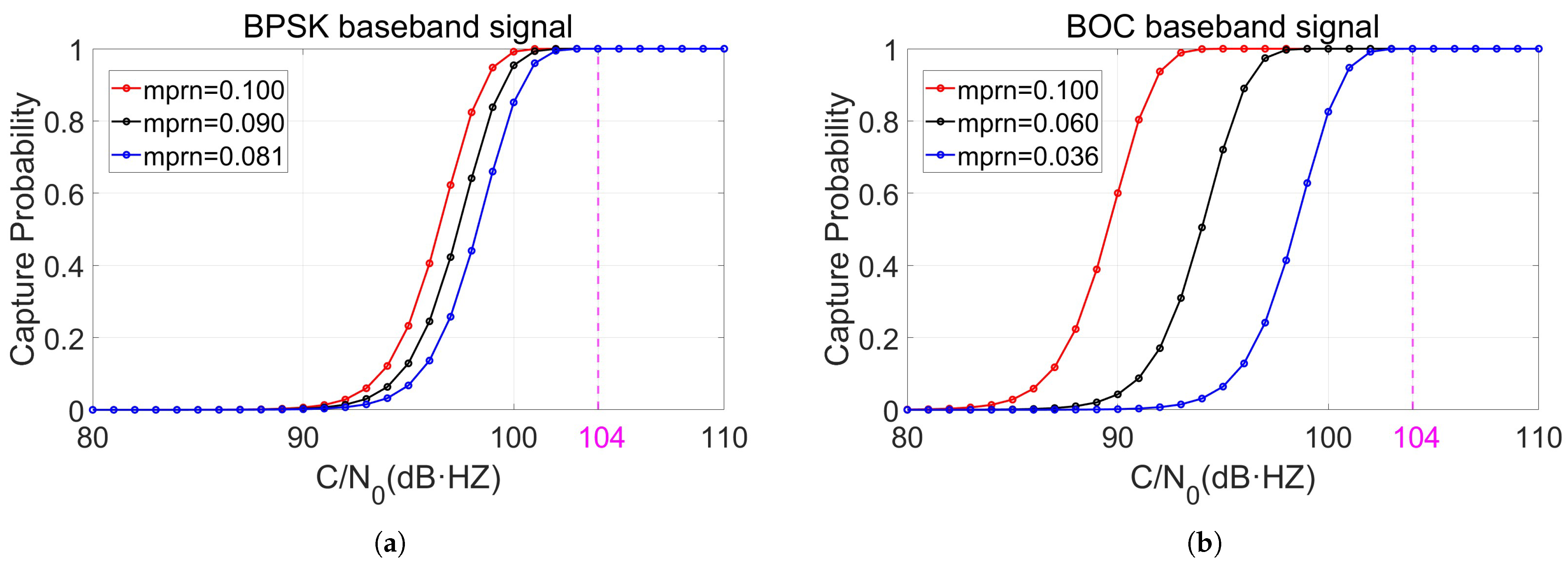

This study validated the proposed mathematical models for the acquisition performance of both BPSK and BOC baseband signals, analyzing comparatively the acquisition performance under different acquisition step sizes, spreading factors, and modulation indices. The results indicate that acquisition performance can be improved by increasing the spreading factor F, the modulation index , and the CNR of the primary beat note signal input to the DPLL and decreasing the acquisition step size and the DPLL input noise bandwidth .

However, as a theoretical exploration, the practicality of the proposed model and conclusions require further multidimensional deepening and validation, which also outlines clear directions for future research.

First, regarding noise modeling, this study simplified the analysis by focusing primarily on additive white Gaussian noise dominated by shot noise. However, in practical links, laser intensity noise, frequency noise, and other factors may exhibit non-Gaussian and non-stationary characteristics. Future work should incorporate these noise sources into the model to quantify their impact on acquisition performance, thereby enhancing the model’s predictive accuracy and engineering guidance value in real space environments.

Second, experimental validation oriented toward engineering implementation is needed. The conclusions in this paper are derived from numerical simulations, and their transition to engineering practice requires experimental support. The next research priority will be to validate the theoretical model by building a ground-based prototype or a high-fidelity hardware-in-the-loop simulation platform.

The communication and ranging signal acquisition performance model proposed in this study demonstrates cross-mission applicability. Its starting point is not specific mission parameters but rather addresses the common challenge in space gravitational wave detection of “minimizing interference with the main carrier while achieving reliable communication and ranging”. The core mathematical relationships of the model are independent of specific parameters, allowing it to be directly transferred to similar missions such as LISA and Taiji. By substituting the corresponding mission parameters, performance predictions and design guidance can be obtained, forming a universal theoretical tool.

6. Conclusions

This study focused on the acquisition of communication and ranging signals employing low-depth phase modulation on the primary carrier within the inter-satellite laser interferometry link for space gravitational wave detection. A systematic theoretical analysis model was established, which quantitatively revealed the influence of key parameters—including modulation index, spreading factor, acquisition step size, and loop bandwidth—on acquisition performance.

Numerical simulations confirm that for the BPSK baseband signal, with a PRN code length of 1024 and an acquisition step size of , the modulation index can be reduced to 0.081 rad. For the BOC baseband signal, with a PRN code length of 1024 and an acquisition step size , the modulation index can be reduced to 0.036 rad. Under this configuration, the system supports an inter-satellite data rate of 62.5 kbps and achieves an acquisition false alarm probability of and a perfect acquisition probability of 1, given a CNR of 104 dB·Hz for the signal input to the DPLL.

The model developed in this study elucidates the key factors governing the acquisition of communication and ranging signals. The findings provide a theoretical foundation and an engineering reference for the design and optimization of future inter-satellite laser links for space-based gravitational wave detection.