Abstract

Drone-view mixed reality (MR) in the Architecture, Engineering, and Construction (AEC) sector faces significant self-localization challenges in low-texture environments, such as bare concrete sites. This study proposes an adaptive sensor fusion framework integrating thermal and visible light (RGB) imagery to enhance tracking robustness for diverse site applications. We introduce the Effective Inlier Count () as a lightweight gating mechanism to evaluate the spatial quality of feature points and dynamically weigh sensor modalities in real-time. By employing a

grid-based spatial filtering algorithm, the system effectively suppresses the influence of geometric burstiness without significant computational overhead on server-side processing. Validation experiments across various real-world scenarios demonstrate that the proposed method maintains high geometric registration accuracy where traditional RGB-only methods fail. In texture-less and specular conditions, the system consistently maintained an average Intersection over Union (IoU) above 0.72, while the baseline suffered from complete tracking loss or significant drift. These results confirm that thermal-RGB integration ensures operational availability and improves long-term stability by mitigating modality-specific noise. This approach offers a reliable solution for various drone-based AEC tasks, particularly in GPS-denied or adverse environments.

1. Introduction

In recent years, image processing based on RGB and thermal imagery has been studied and deployed across a wide range of domains and continues to advance rapidly, driven by progress in sensing and computational methods [1]. In parallel, consumer drones have proliferated as a flexible data-acquisition platform, bringing fundamental changes to industrial workflows. Their applications have expanded beyond hobbyist use to diverse areas, including entertainment and aerial photography [2], geological surveying and mapping, traffic monitoring [3], disaster prevention and search and rescue [4], and precision agriculture [5,6,7]. In parallel, digital transformation is progressing in the Architecture, Engineering, and Construction (AEC) industry, and the utilization of drones as a core data acquisition platform is expanding rapidly [8]. Since drones possess advantages in terms of time efficiency, safety, and cost compared to conventional manual work [9], their utilization is expected in various processes, ranging from the construction planning stage to progress management and post-completion maintenance and inspection [10].

One factor supporting this proliferation is the integration with diverse onboard sensors. While visible-light RGB cameras remain fundamental sensors, drones equipped with thermal cameras are already becoming common in applications such as the detection of structural cracks [11] and tile detachment [12], as well as damage assessment at disaster sites [13].

Furthermore, attempts to integrate drones and mixed reality (MR) technology [14] have recently attracted significant attention. MR is a technology that superimposes virtual 3D information onto real space in real-time, enabling intuitive visualization and interaction. In the AEC field, various applications have been proposed, such as visualization to confirm landscapes by superimposing future buildings onto vacant land [15], comparison between Building Information Modeling (BIM) and actual structures [16], and the superimposed display of inspection results onto facility walls [12,17]. When applying MR to large-scale spaces such as high-rise buildings or urban blocks, or to locations inaccessible to human hands, it is often difficult to grasp the entire target solely from a ground-level viewpoint (e.g., via handheld terminals). In such situations, realizing MR from a drone-view, which moves freely within 3D space, is extremely effective for understanding the entire site comprehensively and intuitively [16].

However, robustly realizing drone-view MR is challenging. The primary technical hurdle is the requirement for high-precision and stabilized self-localization. While it is possible to satisfy this required accuracy by integrating a Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) or Real-Time Kinematic GNSS (RTK-GNSS) with the Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) built into the airframe, accessing position and attitude information typically requires coordination with model-specific Software Development Kits (SDKs) or dedicated airframes. In fact, drone-view MR systems developed by Wen and Kang [15] and Botrugn et al. [18] utilize airframes designed specifically for the project or model-specific SDKs; this reduces system versatility and significantly constrains use cases. Furthermore, the use of GNSS is often restricted in building canyons between urban high-rise buildings or at indoor/semi-indoor construction sites.

To circumvent such dependence on proprietary SDKs and dedicated airframes, methods realizing MR using only general-purpose technologies such as video streaming and screen sharing have been proposed. For example, Kikuchi et al. [19] integrated commercially available drones and MR using general technologies; however, to align the real and virtual spaces, it was necessary to pre-define the flight route and orientation, resulting in the constraint that the trajectory could not be freely changed during MR execution.

Against this background, vision-based approaches using only camera images are attracting attention as a highly versatile solution. For example, Kinoshita et al. [20] realized MR with free flight paths without relying on specific SDKs, using only RGB images and a pre-constructed 3D map. However, a significant limitation exists: methods relying solely on RGB images are vulnerable to texture-less environments, which are ubiquitous at AEC sites [21]. On homogeneous surfaces such as exposed concrete, painted walls, and metal panels, tracking often fails due to a lack of visual feature points, causing significant drift in position estimation.

For this vulnerability in texture-less environments, infrared (thermal) thermography provides a promising physical solution. Unlike RGB cameras that capture visible light reflected from surfaces, thermal sensors detect infrared radiation emitted by materials based on their emissivity and heat capacity [22]. This fundamental difference allows thermal cameras to perceive minute temperature unevenness—referred to as “thermal texture”—even on visually homogeneous surfaces. However, to integrate thermal information into MR systems, two essential challenges must be addressed. The first is temporal variance; since thermal distribution changes drastically due to solar radiation and weather conditions, utilizing a pre-constructed thermal map as a permanent coordinate reference is inappropriate for MR. The second is the computational cost. Many existing RGB-thermal fusion methods require complex feature extraction via deep learning [23] or dense optimization using all pixels. In the context of MR superimposition, where low-latency processing is critical, the computational load of these methods is excessive for real-time execution on limited hardware resources.

Therefore, this study proposes a novel localization method for drone-view MR that adaptively integrates RGB and thermal images. This method primarily utilizes an RGB map-based Visual Positioning System (VPS) for absolute position estimation under general conditions and adaptively fuses RGB and thermal data for relative motion estimation. Through this adaptive sensor fusion, we realize high-precision and seamless position estimation that serves as the foundation for drone-view MR systems, even in challenging environments where conventional RGB-only methods fail.

The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

- •

- Decoupled and Adaptive Fusion Architecture: We present a decoupled localization architecture for drone-view MR that separates RGB map-based absolute pose correction from RGB–thermal relative tracking, enabling stable overlays under texture-poor facade flights without relying on proprietary drone SDKs or GNSS/RTK.

- •

- Empirical validation in AEC Scenarios: We implemented the proposed system and quantified its tracking robustness in real-world AEC scenarios. We demonstrate that our adaptive fusion maintains overlay stability on texture-less exterior walls where conventional RGB-only baselines fail, validating the system’s practical survivability in proximity inspection tasks.

The structure of this paper is as follows. Section 2 provides an overview of related work. Section 3 describes the details of the proposed method, and Section 4 explains the implementation of the prototype. Section 5 reports the experimental results. Following the discussion in Section 6, the conclusion is presented in Section 7.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Drone-Based Mixed Reality in AEC

Research on the integration of drones and AR/MR is diverse, but it can be broadly classified into two categories: data collection for MR content creation and MR utilization for drone operations. In this study, we focus on the latter, specifically drone-viewpoint MR that adds virtual information to drone camera footage. The basic requirement for such systems is registration that matches the coordinates of the real camera and the virtual camera with high precision.

Early approaches tended to sacrifice system flexibility to ensure accuracy. Wen and Kang [15] realized aerial MR for construction site simulation using the Vuforia SDK. While this method enabled free flight paths, it required building a project-specific airframe to access the necessary sensor data, which reduced system versatility. Similarly, the method by Botrugno et al. [18] also depends on specific hardware configurations, limiting deployment to diverse AEC projects.

To enhance versatility, attempts were made in subsequent research to eliminate dependence on dedicated SDKs. Raimbaud et al. [16] implemented an interactive MR application that superimposes BIM models onto real video for quality control. While operating without a dedicated SDK, the registration of reality and virtuality required manual adjustment of rotation and translation, resulting in a high operational load. Kikuchi et al. [19] realized occlusion-aware MR using commercially available drones and general streaming technologies. Although hardware versatility was high, it was necessary to strictly define the drone’s start time, flight route, and orientation in advance for registration. Due to this constraint, the pilot could not freely change the path during operation, making application to dynamic inspection tasks difficult.

More recently, VPS and Simultaneous Localization and Mapping (SLAM) technologies have been applied to balance hardware independence and flight flexibility. Kinoshita et al. [20] combined absolute position estimation via VPS and natural feature point tracking to realize drone MR capable of free flight without a specific SDK. However, a significant limitation exists in this method. It is the reliance solely on RGB images. At AEC sites, there are many texture-less surfaces, such as concrete walls, roofs and roads, where RGB-based tracking fails. This study aims to solve this issue through the integration of thermal information; however, simply adding a sensor is insufficient, and an integration method that satisfies MR-specific requirements (permanence of the coordinate system) is required.

2.2. Visual Localization Challenges: Texture-Less & Geometric Burstiness

2.2.1. VPS and SLAM

In recent years, VPS and Visual SLAM have been widely studied as image-based localization methods for achieving high-precision spatial registration in MR applications. VPS is a method that estimates the 6 degrees of freedom (6DoF) camera pose by pre-constructing a three-dimensional (3D) map of the target environment and associating monocular camera images acquired during operation with 3D points in the known map [24,25]. In this framework, a method is generally used that obtains the camera position and orientation by extracting local features from a query image, estimating the correspondence with feature points on the 3D map, and then solving the Perspective-n-Point (PnP) problem [26]. It has been reported that when sufficiently distributed correspondence points are obtained, high-precision pose estimation on the order of centimeters is possible, making it suitable for high-precision MR superimposition. Such a VPS framework is considered to have high practicality in MR applications in real environments because it can be realized with a relatively lightweight configuration without requiring additional sensors. In fact, it is widely deployed as commercial services such as Immersal VPS [27], Lightship VPS [28], and ARCore Geospatial API [29], and is utilized as a global position estimation infrastructure regardless of whether it is outdoors or indoors.

On the other hand, Visual SLAM, represented by ORB-SLAM [30], is an approach that performs localization and mapping simultaneously, and is characterized by the fact that it does not require prior map construction [30,31]. In Visual SLAM, since the environment map is generated and updated online as the camera moves, there is no need for the prior cost of map construction, and it has the advantage of being able to flexibly adapt to changes such as aging of the environment and the installation of temporary structures. For this reason, it has been widely used in fields that emphasize grasping relative positional relationships, such as robotics and navigation.

Thus, VPS and Visual SLAM are technologies with different premises and characteristics, and selective use according to the application is required. It has been pointed out that VPS, which provides a globally stable coordinate system, is effective for systems that perform MR display based on a consistent world coordinate system over a long period [32,33]. In VPS, since position estimation is performed within a pre-constructed global map coordinate system, there is an advantage that once the correspondence between the MR coordinate system and the map coordinate system is defined, that correspondence can be reused repeatedly.

Based on the above previous studies, in this study, we focus on a position estimation method based on VPS from the viewpoint of emphasizing high-precision consistency with design data and long-term stable MR display.

2.2.2. Visual Localization Challenges in AEC

As previously mentioned, both VPS and Visual SLAM are based on feature point extraction and matching from images. However, at AEC sites, there are widely existing texture-less surfaces that lack the high-contrast visual patterns necessary for robust feature detection, such as freshly poured concrete walls, unpainted gypsum boards, smooth metal panels, and glass curtain walls [21]. Furthermore, even in areas where feature points are detectable, their spatial distribution may compromise the reliability of position estimation. Sattler et al. [25] defined the phenomenon where feature points are detected concentrated in local regions of an image as Geometric Burstiness and pointed out that this is a serious challenge for visual localization. In construction sites, this phenomenon becomes pronounced when textures such as vents, stains, or background vegetation exist locally within vast texture-less wall surfaces. Under such circumstances, even if algorithms such as Random Sample Consensus (RANSAC) detect an apparently large number of inliers (matching points), the configuration becomes geometrically degenerate, causing visual odometry to lose tracking or the PnP solver to become unstable, leading to significant drift or complete failure of position estimation during close-range inspection [34].

As one direction to address this problem, methods utilizing geometric primitives such as line segments or planes instead of point features have been proposed. Structure-based methods using PL-SLAM or the Manhattan World assumption (an assumption modeling the environment as a set of orthogonal planes) are representative examples, and improved robustness in architectural environments has been reported [21]. While these methods are effective for corridors and facades where clear edges and contours exist, they remain vulnerable in situations where a drone navigates the center of vast flat surfaces where geometric primitives themselves are scarce or ambiguous.

As another approach, methods estimating unconstrained Optical Flow integrating rigid body motion and general object motion through learning have been proposed [35]. Such machine learning-based Optical Flow estimation is reported to be able to achieve relatively good motion estimation even in low-texture regions by utilizing learned priors and spatial smoothness. However, many of them require large-scale neural networks, and the computational load is extremely high. In general GPU environments, it is not easy to achieve real-time processing at the resolution and frame rate required for MR applications.

Based on the above, a fundamental trade-off exists in RGB-based position estimation methods for AEC environments. That is, methods such as VPS, which balance the accuracy and operational cost required for MR, are prone to fatal failure on texture-less surfaces, while advanced methods such as learning-based optical flow, which are robust to texture-less conditions, have high computational loads and are not necessarily suitable from the viewpoints of real-time performance for MR and global registration.

2.3. Thermal Imaging for Visual Localization

Thermal imaging has attracted attention in recent years as a localization method in environments where vision is obstructed by smoke, such as fire scenes, or in low-light environments such as nighttime. Under such conditions, while conventional RGB cameras are affected by low contrast or strong illumination fluctuations, thermal cameras can stably acquire patterns based on temperature differences [36,37].

In early research, the feasibility of thermal inertial odometry was demonstrated by directly utilizing radiometric information. For example, Borges et al. [38] proposed a method combining semi-dense optical flow of monocular thermal images with an IMU, recovering scale via road surface detection. By leveraging edge information in thermal images, low-cost and robust pose estimation was realized, demonstrating effectiveness in ground vehicles.

On the other hand, feature-point-based approaches are also evolving. Li et al. [36] proposed a new infrared SLAM algorithm integrating feature point methods and optical flow technology, addressing the problem of cumulative errors caused by weak textures in thermal images.

Furthermore, in recent years, deep learning-based approaches have also been investigated. In this domain, Transformers have been applied to enhance feature robustness. Zhang et al. [23] proposed template-guided low-rank adaptation (TGATrack) to improve RGB-T tracking. While these data-driven methods demonstrate high performance in recognition tasks, they often entail high computational costs for real-time processing.

In addition to system-level research, fundamental performance evaluations of thermal features have also been conducted. Johansson et al. [39] and Mouats et al. [40] conducted comprehensive benchmarks of feature point detectors and descriptors for thermal images. According to their evaluations, it is reported that combinations of Oriented FAST and Rotated BRIEF (ORB) and Fast Retina Keypoint (FREAK) or Binary Robust Invariant Scalable Keypoints (BRISK), or combinations of Speeded Up Robust Features (SURF) and FREAK, show relatively good performance. However, they also concluded that matching using visible light images was still superior under conditions with good visibility and sufficient texture. This suggests that while thermal features are robust against illumination changes, they have lower discriminative power compared to RGB features under standard environments, supporting the view that thermal images should not simply replace RGB but adaptively complement it.

However, when viewing existing research from the perspective of realizing high-precision MR in the AEC field, there are decisive mismatches in both the application domain and system configuration. First, many existing RGB-T frameworks focus primarily on autonomous robot navigation in nighttime or smoke environments [41], and do not focus on the drift problem caused by photometric homogeneity, such as concrete and metal panels, which is ubiquitous in daytime environments at AEC sites. Second, existing Thermal SLAM methods [36] construct maps using thermal images, but this ignores the fatal problem of the lack of map reusability due to the temporal variance of thermal information mentioned in the Introduction. Since a consistent coordinate reference is required throughout the process in MR applications, unstable thermal maps are unacceptable.

Therefore, the unresolved challenge lies in the establishment of Decoupled Adaptive Fusion, which uses thermal information to complement only local tracking robustness in texture-less regions while maintaining a high-precision global coordinate reference via RGB. By proposing this asymmetric hybrid architecture, this study overcomes the practical challenges faced by existing Thermal SLAM and Deep Learning methods and establishes the reliability of drone MR at AEC sites.

2.4. Multi-Modal Sensor Fusion and Uncertainty Estimation Strategies

2.4.1. Tightly-Coupled vs. Loosely-Coupled Architectures

In recent research on RGB–Thermal Odometry and SLAM, tightly coupled approaches—represented by VINS-Fusion [42] and LVI-SAM [43]—have been widely adopted because they can exploit cross-modal constraints in a principled manner under well-behaved sensing conditions. However, studies targeting severely degraded environments report that the practical robustness of tightly coupled optimization depends critically on failure detection and outlier handling; when degraded measurements are injected into a shared estimation pipeline, inconsistencies can propagate across modalities and trigger unstable tracking behavior [44]. This risk is often discussed as a “ripple effect” in which a malfunctioning sensor stream can contaminate the global update through a shared state representation [45]. Moreover, optimization-based pipelines can become computationally demanding as the number of measurements and variables grows, and the resulting runtime overhead is non-trivial for real-time robotic systems [46].

In contrast, loosely coupled approaches adopt a decentralized architecture that estimates modality-specific odometry streams independently and fuses them at a higher level. This modularity naturally supports fault detection and isolation by down-weighting or suspending unreliable modalities, which has been emphasized in long-duration missions conducted under intermittent sensing and communication constraints, including disaster-response scenarios [44]. For UAV-based tasks in complex AEC environments, where sensing conditions can degrade abruptly (e.g., low texture, illumination washout, motion blur, or thermal low-contrast surfaces), such survivability under partial sensor degradation can be a primary requirement, rather than purely maximizing accuracy under nominal conditions.

More recently, sophisticated loosely coupled frameworks such as CompSLAM [47] and MIMOSA [48] have demonstrated high resilience in consistently extreme environments by integrating diverse sensor suites including LiDAR, IMU, and multiple cameras. While these systems achieve robust navigation through complex multi-modal fusion, they introduce significant barriers to practical deployment in the AEC sector. First, integrating LiDAR or high-grade IMUs often necessitates custom sensor rigs that exceed the payload capacity of standard inspection drones. Second, and critically, accessing low-level sensor data required for these fusion algorithms—such as hardware-synchronized IMU streams or raw thermal radiometry—frequently creates a dependency on proprietary SDK or specific drone models. This reliance on specialized hardware and restricted software interfaces limits the universality of these methods, making them difficult to apply broadly across the diverse fleet of off-the-shelf commercial drones typically used in on-site workflows.

2.4.2. Uncertainty Estimation: Deep Learning vs. Geometric Approaches

For a loosely-coupled system to function robustly, it is necessary to dynamically estimate the reliability (uncertainty/weight) of each modality and adapt fusion accordingly. In filtering-based fusion, ideally, the observation noise covariance should be updated online; however, in texture-less or repetitive scenes, erroneous correspondences may pass conventional inlier tests and trigger over-confident updates, causing the covariance to shrink excessively and destabilize subsequent state estimation [49].

Deep learning-based SLAM systems such as DROID-SLAM [50] incorporate learned confidence/weighting mechanisms for image alignment and motion estimation, yet their computational footprint can be substantial and may compete with server-side MR rendering and localization workloads within a strict end-to-end latency budget. In addition, robustness under domain shifts—when deployment conditions deviate from the training distribution—remains a practical concern for safety-critical navigation in unconstrained environments.

Consequently, geometric reliability cues that can be computed efficiently—such as inlier statistics and the spatial dispersion (coverage) of correspondences—have been actively studied as practical alternatives or complements. In particular, when feature correspondences are spatially concentrated (i.e., geometric burstiness), naive inlier counts alone can be misleading; therefore, reliability estimation should account not only for the number of inliers but also for their spatial coverage after pose computation [49]. Motivated by this gap, our work focuses on a lightweight geometric reliability criterion tailored to drone-view MR constraints; the concrete definition and integration strategy are presented in Section 3.

3. Proposed Methods

3.1. System Overview

The method by Kinoshita et al. [20] is an effective framework that combines RGB-based VPS and monocular tracking; however, in texture-less construction sites, RGB tracking frequently fails, leading to the challenge that position estimation is interrupted between VPS updates. To overcome this challenge, this study proposes an adaptive fusion architecture that adds a parallel tracking layer using thermal images, enabling continuous position estimation even in environments with scarce visual features.

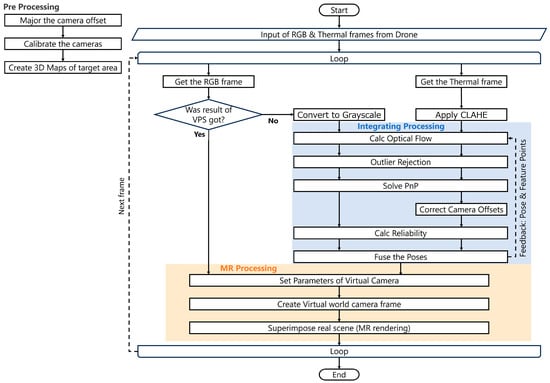

The flow diagram of the processing of the proposed system is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the proposed system. The feedback arrow (labeled ‘Feedback: Pose & Feature Points’) illustrates the temporal recursion, where the fused pose and feature points from the previous frame are used to initialize tracking for the current frame.

This system is an extension of the MR framework established by Kinoshita et al. [20]. In the method of Kinoshita et al., absolute position (Localization) is periodically estimated by RGB-based VPS using a pre-constructed 3D map, and the gaps between VPS updates are complemented by natural feature point tracking (Tracking) of RGB images. While following this basic structure, the proposed method extends the local tracking process from monocular RGB to RGB-Thermal parallel tracking. The system acquires synchronized footage from RGB and Thermal cameras mounted on the drone and performs processing in the following two loops:

- •

- Global Initialization Loop: To reset drift errors, VPS is executed asynchronously using RGB keyframes to estimate the 6DoF pose in the absolute coordinate system.

- •

- Adaptive Dual-Tracking Loop: To fill the update interval (latency) of VPS, relative pose displacement between frames is estimated in two independent pipelines, RGB and Thermal, and fused adaptively based on reliability.

3.2. Geometric and Radiometric Pre-Processing

3.2.1. Geometric Rectification and Calibration

In this system, the RGB camera and the thermal camera are arranged with a physically fixed baseline (offset). To maximize the accuracy of optical flow and ensure pixel correspondence between heterogeneous sensors, the following geometric corrections are performed. First, using pre-acquired intrinsic parameters and distortion coefficients, lens distortion of each image is corrected (undistorted). For the thermal camera specifically, we apply parameters derived from an SfM-based self-calibration method (detailed in Appendix A) to ensure geometric fidelity despite the sensor’s low resolution. This ensures compatibility with the pinhole model, where straight lines are projected as straight lines, reducing tracking errors in optical flow estimation.

Next, to integrate the estimated pose

of the thermal camera into the RGB coordinate system, the pre-calibrated extrinsic parameter (rigid body transformation matrix)

is applied.

3.2.2. Asymmetric Radiometric Enhancement

To maximize feature tracking capabilities in each modality while minimizing the influence of sensor-specific noise, the following asymmetric image processing is applied:

- •

- RGB Stream: Under general daytime environments, RGB sensors have a sufficient dynamic range. Since excessive enhancement processing may compromise the brightness constancy assumption in optical flow, only standard grayscale conversion is performed to preserve the raw luminance distribution.

- •

- Thermal Stream: Thermal images of isothermal building materials, such as concrete walls, characteristically exhibit histograms concentrated in a narrow dynamic range, resulting in extremely low contrast. To address this, we apply Contrast Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalization (CLAHE). We adopted CLAHE specifically to overcome the limitations of standard enhancement methods in visual self-localization. Unlike Global Histogram Equalization (GHE), which maximizes entropy but indiscriminately amplifies sensor noise (e.g., Fixed Pattern Noise), causing ‘False Features’ and geometric burstiness [51], CLAHE effectively reveals only the latent thermal gradients (thermal texture) within the material. Furthermore, unlike restoration methods based on Mean Squared Error (MSE) minimization—which tend to smooth out high-frequency textures due to the ‘Perception-Distortion Trade-off’ [52] and fail to capture structural information [53]—CLAHE prioritizes the distinctiveness of local features required for robust matching by setting a specific Clip Limit on the degree of contrast enhancement [54]. This pre-processing effectively recovers latent texture gradients essential for tracking while preventing the amplification of noise artifacts common in global equalization methods.

3.3. Independent Dual-Pipeline Tracking

The core of this method is a parallel pipeline structure that independently performs pose estimation for each of the RGB and thermal images. By performing geometric verification individually for each sensor rather than using simple image composition (early fusion), the influence when one sensor fails is eliminated. The processing for each sensor is conducted according to the following steps:

- Optical Flow Estimation: For the undistorted images, feature points from the previous frame are tracked to the current frame using the Lucas-Kanade method [55] or similar.

- Outlier Rejection: Geometric verification using RANSAC is performed to remove outliers due to moving objects or mismatches.

Pose Estimation (PnP): The PnP problem is solved using the feature points remaining as inliers and the intrinsic parameter matrix K specific to each camera, and the camera movement amount (relative pose) is calculated.

3.4. Adaptive Pose Fusion

This subsection describes the method for adaptively integrating the individual pose estimation results obtained from RGB and Thermal images in an environment-adaptive manner.

3.4.1. Reliability Metric Based on Geometric Consistency

The design of the reliability metric is a crucial element that determines the robustness of the fusion. Conventionally, image gradient intensity (Gradient Magnitude) and the number of inliers by RANSAC have been used as reliability metrics [30]. However, in texture-less environments such as construction sites, these metrics often have the problem of outputting erroneously high reliability. For example, when a phenomenon occurs where feature points concentrate in a narrow area (Geometric Burstiness), such as on fences, vegetation, or stains on concrete walls, the apparent number of inliers increases despite the low geometric constraint [25].

If pose estimation is performed without considering such biased distribution, it leads to drift in a specific direction or instability in estimation. Therefore, in this study, to evaluate not only the number of feature points but also the spatial distribution simultaneously, the effective inlier count () proposed by Sattler et al. [25] was adopted as the reliability metric. The image area was divided into an

grid, and only if at least one inlier existed within each grid cell

, that cell was counted as effective:

where

is the confidence threshold for guaranteeing geometric stability. Note that theoretically,

(total grid count), and its specific value is an empirical hyperparameter determined by the image resolution and grid division. The subscript

{RGB, Thermal} denotes the sensor modality. By using the metric, it becomes possible to eliminate mis-evaluations due to local bursts and selectively utilize only high-quality frames where feature points are dispersed throughout the entire screen.

3.4.2. Spatial Pose Fusion Strategy

Integration was performed according to the following procedure. First, the estimated pose

and

of the thermal camera was transformed into the RGB coordinate system using the offset

defined in Section 3.2.1 to obtain the transformed position

and rotation

. Next, an adaptive fusion weight

(constrained to

) for each sensor modality based on the number of effective inliers for each sensor was calculated. This weighting strategy was explicitly designed to prioritize the sensor modality that offered stronger geometric constraints. By allocating a higher weight

to the sensor with a larger effective spatial distribution (), the system actively suppressed the influence of the modality suffering from tracking instability (e.g., due to texture loss or thermal equilibrium), thereby ensuring robust trajectory estimation.

The fused pose

and

were defined as follows.

- •

- Translation: Since this was between two points in Euclidean space, linear interpolation (Lerp) was used.

- •

- Rotation: In a unit quaternion space representing 3D rotation, simple linear interpolation leads to distortion of the rotation speed and norm failure. Therefore, Spherical Linear Interpolation (Slerp), which is a mathematically rigorous rotation interpolation, was adopted [56].

By this logic, when both RGB and Thermal were valid, they were optimally blended according to their respective geometric strengths; if RGB was lost and only Thermal survived,

and the system automatically transitioned seamlessly to Thermal-only tracking.

4. Implementation of Prototype System

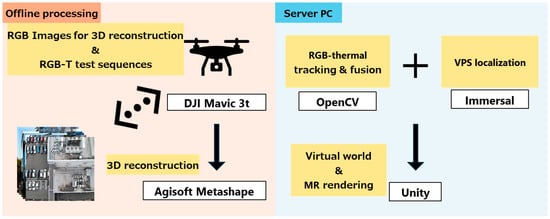

This section describes the hardware configuration, software environment, and detailed implementation parameters of the prototype system used for the validation experiments of the proposed method. Details of the equipment used for the implementation of the prototype system are shown in Table 1, details of the software and services are shown in Table 2, and a conceptual image of the development environment integration is shown in Figure 2. The source code files for the simulation are provided in the Supplementary Materials (Unity Project).

Table 1.

Environment of the prototype system.

Table 2.

Software/services used in the prototype system.

Figure 2.

Development Environment Integration Concept.

4.1. Overview of Prototype System Implementation

The basic architecture for global self-localization follows the asynchronous remote rendering framework established by Kinoshita et al. [17]. Specifically, the processing flow of VPS requests, the latency compensation logic, and the registration of virtual cameras for MR on the Unity scene using these methods follow their approach. The system operates in the following two parallel threads:

Global localization thread: Keyframes are sent asynchronously to the Immersal VPS server. Since a delay of 1 to 3 s occurs due to network transmission and server processing, directly applying the returned pose would result in visual inconsistency with the current frame.

Real-time compensation thread: To compensate for this latency, the system continuously tracks the relative movement of the camera using 2D-3D point matching and optical flow. Upon receiving the delayed VPS pose

at time

, the system calculates the accumulated displacement

from the tracking since the transmission time

to the present. The corrected global pose

is calculated as

. The unique contribution of this study lies in implementing RGB-Thermal adaptive tracking in this thread to enhance robustness in texture-less environments.

Through this approach, the position and orientation of the virtual camera in Unity maintain constant synchronization with the live video, regardless of the VPS response time.

4.2. Dual-Sensor Pre-Processing

In heterogeneous sensor fusion, ensuring geometric consistency between the RGB camera and the thermal camera is indispensable. In particular, the thermal camera of the DJI Mavic 3T has a low resolution (640 × 512), and since sensor cropping occurs in the dual-screen video mode with RGB, it possesses intrinsic parameters that differ from the nominal parameters (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of native and effective sensor resolutions in dual-stream visualization mode.

To address this, the following calibration methods were implemented.

- •

- RGB camera: Using Zhang’s method [57] with a standard chessboard pattern, intrinsic parameters and distortion coefficients were calculated using the OpenCV library.

- •

- Thermal camera: Standard chessboard calibration is often unreliable for thermal sensors due to low resolution and thermal diffusion [58]. Therefore, we adopted a Structure-from-Motion (SfM) based self-calibration approach. Crucially, to ensure high precision and avoid optimization errors in low-texture experimental scenes, this calibration was conducted as an offline pre-process, distinct from the main data collection. We utilized a dedicated dataset captured over a structure with rich thermal heterogeneity to derive the intrinsic parameters via bundle adjustment. Since these parameters represent the static physical properties of the lens, the estimated values were fixed and applied to all subsequent experimental reconstructions. The detailed methodology and validation are provided in Appendix A and all estimated calibration results are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4. Estimated intrinsic parameters for the RGB and thermal cameras.

Table 4. Estimated intrinsic parameters for the RGB and thermal cameras. - •

- Extrinsic parameters: The extrinsic parameters (rigid body transformation matrix) between both cameras were fixed with a translation vector based on the physical design blueprints of the gimbal mechanism.

During online processing, lens distortion correction and parallax correction for both images were applied in real-time using these parameters.

It should be noted that the thermal stream was automatically upscaled by the drone’s internal firmware to match the video output. While the specific interpolation algorithm was proprietary (black box), a qualitative analysis of the recorded footage confirmed that the output exhibited smooth gradients characteristic of higher-order resampling, avoiding blocky, aliased artifacts that typically introduce false edges. Thus, despite the “black box” nature of the hardware processing, the risk of introducing erroneous features into the optical flow calculation was minimized.

4.3. Implementation Details of Adaptive Tracking

This subsection details the specific engineering parameters and optimization methods applied to realize the adaptive tracking logic described in Section 3.

- •

- Radiometric Enhancement: The CLAHE algorithm defined in Section 3 was implemented using the Imgproc.createCLAHE function in OpenCV. The parameters were empirically optimized for the specific thermal sensor used in this study. We selected a Clip Limit of 2.0 and a grid size of 8 × 8, as preliminary testing confirmed these values provide the optimal trade-off between enhancing local texture for survivability and suppressing sensor-specific noise (e.g., fixed pattern noise).

- •

- Tracking Parameters: The Lucas-Kanade tracker was configured with a search window size of pixels and a pyramid level of 5 to accommodate rapid drone maneuvers. The outlier rejection was performed using the RANSAC algorithm (specifically, the UPnP solver in solvePnPRansac). To guarantee real-time performance and to bound the computation time, we explicitly set the maximum number of RANSAC iterations to 400 with a confidence level of 0.98, rather than relying on unbounded adaptive iterations. The reprojection error threshold was empirically set to 5.0 pixels to accommodate minor sensor noise and drone vibrations observed in our system. Furthermore, to mitigate the risk that RANSAC would accept geometrically unstable models (e.g., due to strongly clustered inliers), the proposed Effective Inlier Count, , served as a post-RANSAC validation metric and automatically down-weighted pose estimates that lacked sufficient spatial support in the image.

- •

- Fusion Logic Execution: For reliability evaluation, the Effective Inlier Count () defined in Section 3 was used. Following the methodology of Sattler et al. [25], which suggests a cell size of approximately pixels to ensure spatial diversity, we partitioned our resolution frames into a grid. This resulted in an exact cell size of pixels, providing a balanced spatial constraint across the entire field of view. In this implementation, considering that the number of feature points required for robust initialization in standard Visual SLAM, such as ORB-SLAM, is 30 to 50 [30], a conservative value of was adopted. If the of either sensor fell below 50, the system immediately set the reliability of that sensor to zero, thereby excluding unstable estimation results that caused drift from the fusion.

4.4. Experimental Setup Using Pre-Recorded Datasets

While the proposed architecture supports real-time wireless video transmission, offline evaluation using pre-recorded datasets was adopted for the experimental validation in this study.

The reason for adopting this protocol was to eliminate variability in flight trajectories and environmental conditions (wind, illumination changes, etc.) and to verify the proposed method against conventional methods (RGB-only, Thermal-only) under Identical Conditions. By inputting lossless recorded RGB and thermal video streams on the drone into the server pipeline, it was possible to purely evaluate the processing performance and robustness of the algorithm. Note that the influence of latency caused by network transmission has already been quantified and verified by Kinoshita et al. [20] and was therefore excluded from the scope of this experiment.

5. Verification Test

In this section, using the prototype system constructed in Section 4, we demonstrate that the proposed method achieves comparable performance in general environments and significantly improved robustness in challenging scenarios over the existing method [20] in diverse environments. The validation was conducted in two major phases. First was the quantitative comparison of MR registration accuracy between the proposed system and the existing system. Both algorithms were applied to the same recorded video to verify the fundamental accuracy in general flight environments. Second was the validation of robustness in environments that are harsh for RGB cameras (texture-less). Here, a durability test was performed where initialization by VPS was successful only once, after which registration was continued using only tracking, and the transition of the accuracy was analyzed chronologically. In this experiment, the drone functioned as an image acquisition device, and all computational processing was performed on a server PC after video transmission.

5.1. Comparison of Positioning Accuracy

In MR, geometric registration between the real space and the virtual space is one of the most important requirements [59]. Therefore, it is essential to verify the fundamental registration accuracy of the proposed system. In this validation, IoU (Intersection over Union) was adopted as a quantitative index for registration accuracy. IoU is an evaluation scale generally used in benchmarks for object detection and similar tasks, and is defined by the following equation [60]:

where TP (True Positive) represents the number of pixels in correctly detected regions of interest (ROI), FP (False Positive) represents erroneously detected non-interest regions, and FN (False Negative) represents regions of interest that were missed. In MR, geometric registration can be indexed by setting an ROI on an object in the real space and evaluating the degree of overlap with the corresponding virtual object (semi-transparent monochromatic texture). In this validation, an IoU closer to 1 is judged as higher registration accuracy. It should be noted that the ground truth masks for IoU calculation were manually annotated using LabelMe. Since an external motion capture system was not deployed in the outdoor environment, minor human-induced biases in the mask creation cannot be theoretically excluded. To minimize annotation ambiguity, we intentionally employed simple geometric targets (squares) rather than complex shapes. Furthermore, to ensure transparency and reproducibility, the raw video and frame-by-frame measurement data are publicly available (see Data Availability Statement).

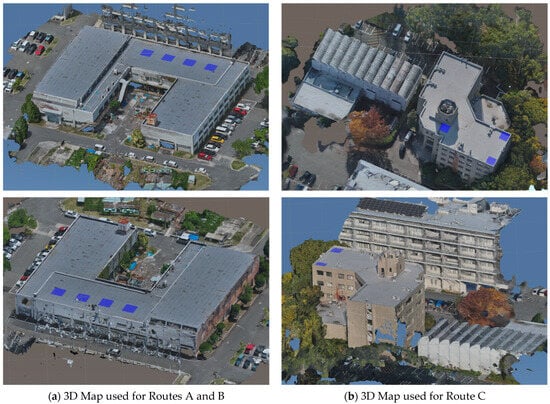

Since no public dataset currently satisfies the specific requirements for RGB-thermal drone MR in construction sites, the validation was conducted using a video recorded via manual drone piloting at the Suita Campus of The University of Osaka (2-1 Yamadaoka, Suita 565-0871, Osaka, Japan). The input footage used for these experiments is available in the Supplementary Materials (Video Folder). The data acquisition was conducted specifically at Building S2 for Routes A and B, and Building M4 for Route C, along the following three types of routes:

- •

- Route A (Texture-Rich): An overhead viewpoint from above Building S2. A general environment includes diverse objects such as buildings, roads, and vegetation. It follows an elliptical orbit after translation.

- •

- Route B (Texture-less/Bursty): An environment in close proximity to the rooftop of Building S2. Homogeneous concrete surfaces occupy most of the field of view, accompanied by rapid frame changes due to drone movement.

- •

- Route C (Long-term/Specular): An environment involving close-up photography of the rooftop and walls of Building M4. Although it presents low-texture characteristics similar to Route B, the visibility of tiled walls and surrounding vegetation renders it less challenging than the completely homogeneous environment of Building S2. However, it introduces other difficulties, such as specular reflections from water puddles and repetitions of similar shapes.

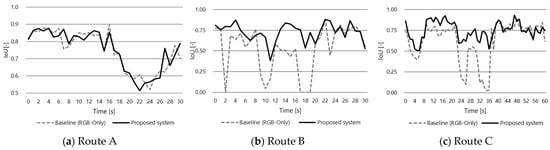

Route A was for control experiments where tracking is easy, even with RGB alone, while Routes B and C assumed environments that are harsh for RGB. For the recorded video of each route, MR superimposition was performed using the proposed system and the existing system, and the average IoU was calculated approximately every second. For validation, virtual 3D models (blue semi-transparent) arranged at equal intervals were used (see Figure 3), and the IoU with mask images created using the image editing software LabelMe (version 5.6.0) was measured. Figure 4 and Table 5 show the measured IoU results. The detailed time-series measurement data for this and all subsequent experiments can be found in the Supplementary Materials (Data Folder). While both methods showed high accuracy in Route A, the proposed method recorded accuracy significantly exceeding that of the existing method in Routes B and C.

Figure 3.

3D maps used for (a) Routes A and B and (b) Route C. The semi-transparent blue squares placed on the building rooftops are the objects for MR display.

Figure 4.

Comparison of the proposed system and the baseline method in Routes A–C (IoU).

Table 5.

Average IoU in each route.

5.2. Durability Analysis in Communication-Denied or VPS-Lost Environments

The proposed system typically compensates for cumulative error (drift) through periodic VPS requests. However, in real-world environments such as infrastructure inspections, it is expected that scenarios where VPS itself fails due to insufficient texture, or where verification with the server is impossible due to communication delays or disruptions, will occur frequently. Therefore, a durability test was conducted on Route B and Route C, where initialization by VPS was performed only once at the beginning, after which registration was maintained solely through pure tracking. This evaluated the geometric robustness of the system during VPS failure or in communication-denied environments.

5.2.1. Analysis of Route B: Mutual Rescue in Geometric Burstiness

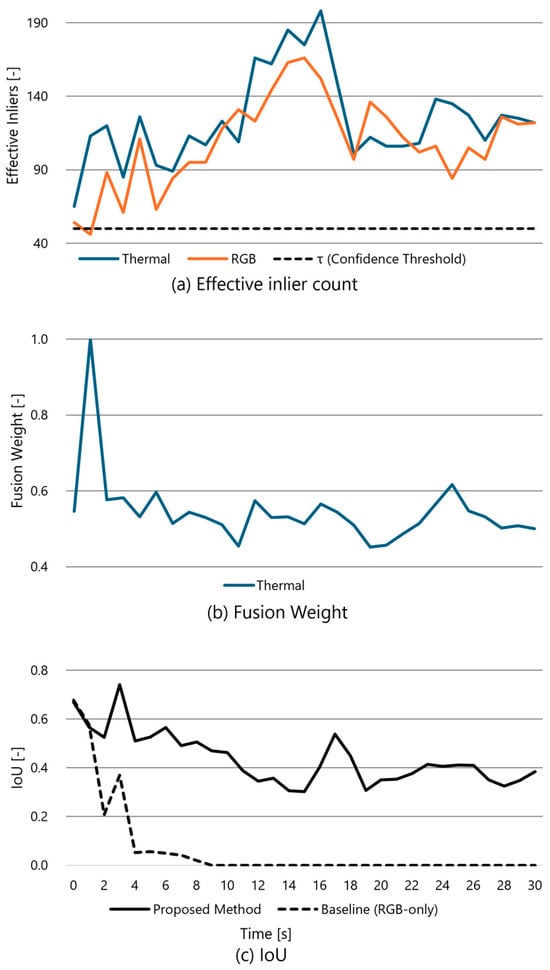

The time-series data for Route B (effective inlier count, fusion weight, IoU) is shown in Figure 5 and a comparison of the tracking status is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 5.

(a) Effective inlier count, (b) fusion weight, and (c) IoU in Route B after operating VPS only once.

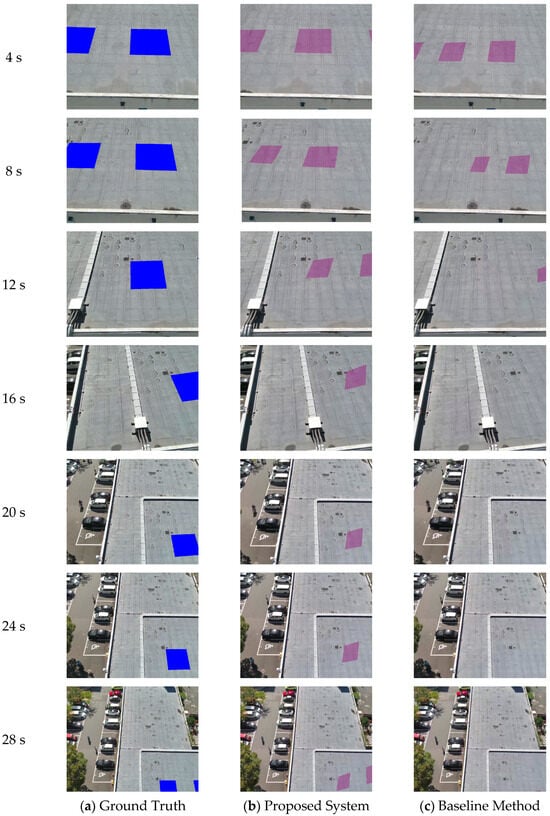

Figure 6.

Comparison of tracking status in Route B over time (4 s to 28 s). The blue overlays represent the Ground Truth (GT) positions, while the purple overlays indicate the MR registration results estimated by the respective methods.

Of particular note was the behavior near

immediately after the start of the experiment. At this point, the number of RGB effective inliers dropped to 46 (Figure 5a). This was a value below the reliability threshold () set for this prototype system (Section 4.3), suggesting that geometric information from the RGB image was insufficient for position estimation. The proposed system responded immediately to this critical situation. The thermal weight at

reached 1.0 (Figure 5b). Given the normalization constraint

, this saturation implied that the system had decided to completely cut off the RGB information and rely solely on the thermal camera. In contrast, the existing method (baseline method), which relied solely on RGB, could not withstand this moment of texture loss, and its IoU plummeted to nearly 0 at approximately

, falling into a lost state (Figure 5c). Subsequently, as the drone moved and the number of RGB effective inliers increased, the system immediately adjusted the weights for RGB and thermal again, returning to cooperative tracking. This result demonstrates that in environments where visual texture is missing, thermal information prevents system loss and improves availability.

Furthermore, the robustness of the system was observed during rapid scene transitions in the latter half of the flight. As shown in Figure 6, the field of view changed drastically between t = 16 s and 20 s as the ground appeared in the frame, followed by a rapid expansion of the visual range due to drone ascent between t = 24 s and 28 s. While the baseline method suffered a significant drop in accuracy (IoU < 0.1) around t = 22–26 s—likely unable to recover from these rapid environmental changes—the proposed system consistently maintained stable tracking. This demonstrates that the fused odometry retains robustness against dynamic scale and scene changes where conventional methods fail.

5.2.2. Analysis of Route C: Drift Suppression via Consensus

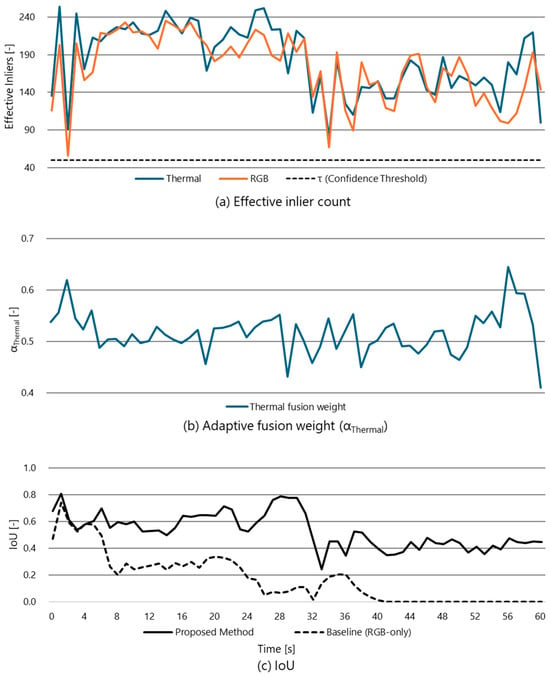

The time-series data for Route C (effective inlier count, fusion weight, IoU) is shown in Figure 7 and a comparison of the tracking status is shown in Figure 8.

Figure 7.

(a) Effective inlier count, (b)fusion weight, and (c) IoU in Route C after operating VPS only once.

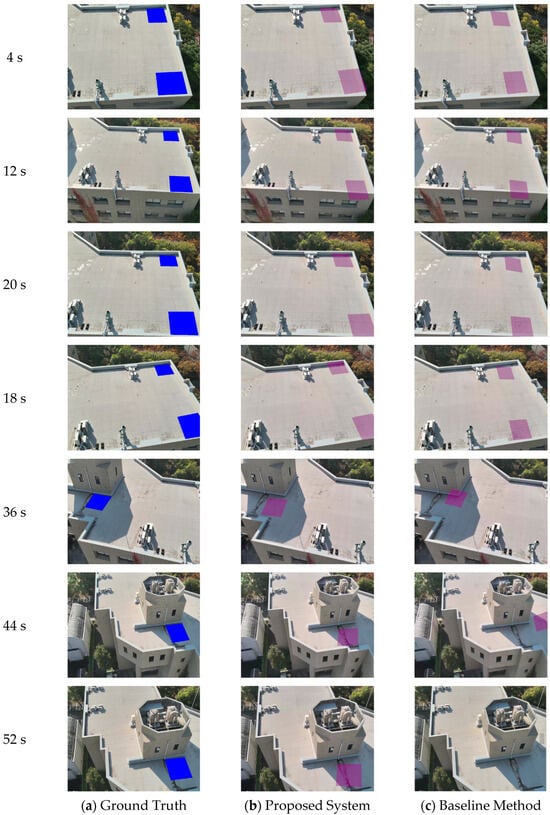

Figure 8.

Comparison of tracking status in Route C over time. The blue overlays represent the Ground Truth (GT) and the purple overlays indicate the MR registration results estimated by the respective methods.

The results for Route C demonstrate the effect of raising the baseline accuracy in long-term tracking. In this route, although the existing method avoided complete loss, a trend was observed where the IoU gradually decreased over time. This is a drift phenomenon that occurs as a result of the accumulation of minute matching errors characteristic of a single sensor.

On the other hand, the proposed method maintained a high accuracy of

for 30 s. In this interval, it is noteworthy that both RGB and thermal maintained a sufficient number of effective inliers. Under this condition, the system exhibited behavior where the fusion weight was allocated approximately at

.

Qualitatively, integrating these two heterogeneous observation sources leverages the orthogonality of their failure modes. Since RGB and thermal images are generated from distinct physical phenomena (visible light reflection vs. thermal radiation), the environmental factors causing tracking loss (e.g., lack of visual texture vs. thermal equilibrium) are unlikely to occur simultaneously in most practical scenarios. Consequently, the fused consensus effectively mitigates the risk of single-modality tracking failure, ensuring geometric stability even when one sensor is compromised. This confirms that multimodal integration not only prevents loss but also actively improves tracking precision even in feature-rich environments.

6. Discussion

In this section, we discuss the theoretical significance and practical value of the proposed method based on the findings obtained from the experimental results.

6.1. Lightweight Spatial Filtering for Real-Time Multimodal Fusion

The technical core of this study lies in the introduction (Section 1) of the Effective Inlier Count () as a metric to dynamically compare and integrate the reliability of heterogeneous sensors (RGB and Thermal). While state-of-the-art deep learning-based reliability estimators can provide robust results, the proposed grid-based

offers an exceptionally low computational footprint. Even with the high-performance computational resources of a server-side PC, minimizing the per-frame processing overhead is critical for reducing end-to-end latency in MR applications. As shown by the results of experimental Route B,

accurately detected the decrease in inliers of the RGB sensor and functioned as a trigger to switch the system to thermal-led tracking. By employing a lightweight spatial filtering algorithm, we effectively suppressed the influence of geometric burstiness without sacrificing the real-time responsiveness required for synchronized MR visualization. This metric provides a practical solution for evaluating sensors with different physical characteristics on the same scale and achieving adaptive sensor fusion.

It is worth noting that while the proposed lightweight algorithm is theoretically compatible with edge computing, we adopted a server-side architecture in this study. This design choice prioritizes hardware versatility, enabling the system to function with any standard commercial drone capable of video streaming, thereby avoiding the constraints of model-specific onboard SDKs.

6.2. Achieving Robust Drone-Based MR via Thermal Integration

The achievement of this study lies in the improvement of the robustness of drone-view MR by integrating Thermal images into an RGB map-based self-localization system in low-texture environments such as construction sites.

In construction sites where bare concrete walls or frequently changing lighting conditions exist, there are limits to maintaining tracking with RGB alone, which has been a factor hindering the practical application of drone MR in the AEC field (the loss of the Baseline in Route B supports this). The results of this experiment demonstrated that thermal information is one of the effective modalities for complementing this weakness of RGB. In situations where visible light texture is missing (Route B), the thermal distribution provided stable geometric features and prevented system loss. Moreover, the validation confirmed that the system maintains operational stability even during rapid environmental changes—such as sudden shifts in the field of view or abrupt scale changes caused by drone maneuvers—where single-modality baselines are prone to tracking failures. The robustness against environmental artifacts stems fundamentally from the physical orthogonality of the sensor modalities. Since the failure modes—‘Geometric Burstiness’ in RGB (due to illumination) and ‘Thermal Equilibrium’ in Thermal (due to contrast)—rarely coincide in operational AEC environments, our adaptive architecture successfully exploits this non-overlapping failure probability.

Furthermore, in long-term flights (Route C), although the environment was non-ideal for RGB—including specular reflections and weak-textured planes—the integration effect between heterogeneous sensors mitigated the drift error characteristic of a single sensor and contributed to maintaining the geometric consistency of the MR display. The proposed method is an approach that complements vulnerabilities through Thermal fusion while taking advantage of high-precision foundational technology that is RGB map-based. This has shown the possibility of providing a highly reliable MR experience that does not depend on the SDK or model, even in GPS-denied environments or under adverse conditions.

Regarding the transition between modalities, the current system determines fusion weights based on the instantaneous

value. While incorporating temporal consistency constraints (e.g., low-pass filtering) could suppress jitter and improve visual comfort, it introduces latency in weight adaptation. In critical scenarios where one modality fails abruptly, such latency would delay the system from completely discarding the unreliable modality, potentially leading to tracking loss. Therefore, we prioritized instantaneous responsiveness in this study to maximize robustness against rapid environmental changes, although temporal smoothing remains a valid optimization for enhancing user experience in stable conditions.

6.3. Limitations and Future Work

The constraints and future challenges of the proposed system in this study are described.

First, regarding the comparison with existing solutions, our vision-based approach has inherent physical limitations compared to sensor-heavy frameworks. Unlike sophisticated loosely coupled systems such as MIMOSA [48] or CompSLAM [47] that integrate LiDAR or high-end IMUs to ensure navigation in zero-visibility conditions, our system relies solely on RGB and thermal images. Consequently, tracking remains challenging in extreme environments where both modalities lose discernible features simultaneously. Specifically, feature stability in thermal images is highly dependent on temperature gradients. If the target surface reaches a state of ‘thermal equilibrium’ (e.g., concrete structures at dawn or dusk, or polished metal surfaces reflecting uniform surroundings), the thermal texture contrast degrades significantly. In such scenarios, if the RGB stream is also texture-less, our system lacks the geometric constraints necessary for pose estimation. However, as discussed in Section 2.4, relying on such specialized hardware configurations would impose critical restrictions on payload capacity and software interoperability (e.g., dependencies on proprietary SDK). Therefore, we accept this trade-off to prioritize the hardware universality and immediate applicability to standard commercial drones, which are essential for scalable on-site deployment.

Second, there is a dependency on pre-existing maps and adaptation to environmental changes. Since this method requires pre-created 3D maps, its application is restricted in environments where the structure changes daily, such as buildings under construction, or for objects that are too vast to make map creation difficult.

Third, there is a dependency on the initialization process (VPS). The system depends on VPS for the initial alignment of tracking and the correction of cumulative errors. Therefore, if VPS does not succeed even once in a texture-less environment or similar, MR superimposition cannot be started.

Fourth, regarding the temporal scope of the evaluation, this study focused on verifying short-term robustness (30 s). This duration was selected to validate the system’s capability as a gap-filling mechanism to bridge the typical latency of VPS updates (1–3 s). While the results confirmed that the system possesses a sufficient safety margin (10× the typical interval) to survive in texture-less environments, the long-term drift behavior of the fused odometry over extended periods without any VPS correction remains to be fully characterized in future work.

Finally, there is a lack of a recovery function for VPS false positives. Although VPS is a highly accurate technology, its performance can deteriorate not only in environments with repetitive patterns but also in texture-less environments—such as the concrete surfaces investigated in this study—where the lack of distinct visual features can lead to incorrect initializations or significant pose errors. In the experiments conducted in this study, this risk was mitigated by manual visual verification to ensure that the initial pose was within the acceptable error margin, thereby guaranteeing the validity of the evaluation data. For fully autonomous scenarios, it is important to note that our architecture inherently possesses a self-recovery capability—where subsequent valid VPS updates in the continuous loop can overwrite erroneous poses. However, to prevent even temporary tracking instability caused by an initial outlier, an automated validation mechanism is desirable. Therefore, future work will focus on implementing a ‘geometric sanity check’ to explicitly detect and reject false positive VPS responses before integration.

7. Conclusions

In this study, to address the vulnerability of self-localization in low-texture environments—a challenge for drone-view MR systems in the AEC industry—we proposed an adaptive sensor fusion method that integrates Thermal and RGB images. The primary conclusions of this study are as follows.

- •

- Establishment of a lightweight geometric gating mechanism: We introduced the Effective Inlier Count as a metric to evaluate the reliability of heterogeneous sensors in real-time and on a unified scale. In drone systems with limited computational resources, this metric effectively eliminates erroneous reliability judgments caused by geometric burstiness (local concentration of feature points) without the need for computationally expensive covariance estimation. This enabled robust sensor selection based on spatial quality rather than mere quantity of feature points.

- •

- Simultaneous achievement of availability and stability: Validation experiments in real-world environments demonstrated that the proposed method exhibits robustness through two distinct mechanisms. First, in critical situations where visible light texture is missing, thermal information functioned as a fail-safe modality to prevent system loss, ensuring operational availability. Second, during long-term flights, the integration effect between sensors with different physical characteristics mitigated drift errors inherent to single modalities, thereby maintaining geometric stability.

- •

- Contribution to Digital Transformation in the AEC industry: The proposed system provides a practical solution for the full automation of infrastructure inspection and construction management by offering an MR experience that remains continuous and accurate even in GPS-denied environments or under adverse conditions. By leveraging existing high-precision RGB map-based foundational technology while complementing its primary weakness through thermal fusion, this approach significantly enhances the reliability of drone utilization within the AEC sector.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.18087871. The materials are organized into the following folders: Video Folder: Input footage for Routes A–C and output result videos under various experimental conditions; Data Folder: result.xlsx containing detailed time-series IoU measurement data; Unity Project: Source code files for the simulation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.F. and T.F.; methodology, R.F.; software, R.F.; validation, R.F.; formal analysis, R.F.; investigation, R.F.; resources, T.F.; data curation, R.F.; writing—original draft preparation, R.F.; writing—review and editing, R.F. and T.F.; visualization, R.F.; supervision, T.F.; project administration, T.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially funded by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI Grant Number JP23K11724.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The source code, experimental data (Data Folder), and video materials (Video Folder) presented in this study are openly available in Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.18087871. The specific 3D map data of the experimental site used for the VPS is not publicly available due to privacy and security restrictions.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this work, the authors used ChatGPT (model: GPT-5.2) and Gemini (model: Gemini 3 Pro) to improve the readability and language of the text. After using these tools/services, the authors reviewed and edited the content as necessary and took full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 6DoF | 6 degrees of freedom |

| AEC | Architecture, Engineering, and Construction |

| BIM | Building Information Modeling |

| CLAHE | Contrast Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalization |

| GNSS | Global Navigation Satellite System |

| IMU | Inertial Measurement Unit |

| IoU | Intersection over Union |

| Lerp | Linear interpolation |

| MR | Mixed Reality |

| PnP | Perspective-n-Point |

| RANSAC | Random Sample Consensus |

| ROI | regions of interest |

| RTK-GNSS | Real-Time Kinematic GNSS |

| SDKs | Software Development Kits |

| SLAM | Simultaneous Localization and Mapping |

| SfM | Structure-from-Motion |

| Slerp | Spherical Linear interpolation |

| VPS | Visual Positioning System |

Appendix A. Thermal Camera Calibration Methodology

To ensure precise spatial alignment and geometric consistency between heterogeneous sensors, accurate estimation of the camera’s intrinsic parameters (focal length

principal point

) and lens distortion coefficients () was essential. This section details the calibration principles and the specific workflow adopted in this study.

Appendix A.1. Physical Nature of Lens Distortion

The standard approach for camera calibration was based on the Pinhole Camera Model, extended with lens distortion models. Typically, Zhang’s method [50] is employed, which utilizes a planar chessboard pattern. By detecting the grid corners with high sub-pixel accuracy, the algorithm solved for the intrinsic matrix

and distortion coefficients by minimizing the reprojection error between the detected corners and their theoretical positions. For the RGB camera in this study, we applied this standard method using the OpenCV library, as the high resolution and sharp contrast of the visible spectrum allow for robust corner detection.

Appendix A.2. SfM-Based Self-Calibration (Thermal Camera)

For thermal cameras, applying Zhang’s method is often difficult. In our preliminary tests, we confirmed that thermal diffusion and low sensor resolution blurred the chessboard patterns, leading to unreliable corner detection.

To address this, we adopted a Self-Calibration approach based on Structure-from-Motion (SfM). Fundamentally, SfM is a technique designed to reconstruct 3D scene geometry from 2D images. However, accurate 3D reconstruction mathematically requires knowledge of the camera’s internal geometry. In a self-calibration setup, the SfM algorithm treats the intrinsic parameters not as fixed inputs, but as unknown variables to be solved. Consequently, the calibration parameters are generated as a necessary by-product of the 3D reconstruction process.

Appendix A.3. Calibration Workflow and Results

To ensure robustness and avoid the risk of “circular dependency” in low-texture experimental scenes, we implemented an Offline Pre-Calibration strategy.

- Data Acquisition: A dedicated flight was conducted over a test site selected for its high thermal contrast (e.g., a structural complex with varied materials) to maximize feature detection and tie-point generation.

- Estimation: The SfM reconstruction pipeline was executed using Agisoft Metashape. During the image alignment phase, the intrinsic parameters were calculated and retrieved as a computational by-product of the optimization process described in Appendix A.2.

- Validation & Application: The derived parameters (shown in Table 4 in the main text) demonstrated a low reprojection error (0.32).

To verify the accuracy of the estimated parameters, we conducted a controlled validation experiment using a planar target with known geometry. Nine chemical heat pads were attached to a flat, rectangular whiteboard to serve as distinct thermal markers. These markers were arranged in a 3 × 3 grid pattern, positioned at the four corners, the midpoints of the edges, and the geometric center.

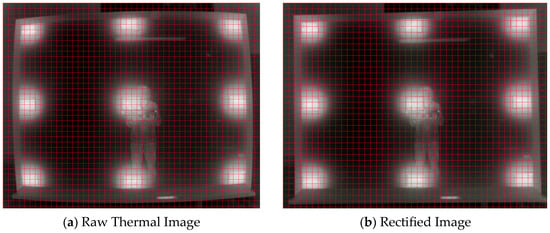

To visualize the geometric distortion, evenly spaced red grid lines were overlaid on the images. As illustrated in Figure A1, the raw image (a) exhibited significant barrel distortion, where the arrangement of the markers appeared curved relative to the straight lines. In contrast, the rectified image (b) showed a clear improvement in linearity compared to (a). This confirmed that the estimated parameters effectively mitigated the lens distortion.

Figure A1.

Qualitative validation of thermal lens distortion correction. (a) The raw thermal image showing barrel distortion relative to the overlaid grid lines. (b) The rectified image using the estimated parameters, showing improved linearity compared to (a).

References

- Song, K.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, L.; Yan, Y.; Meng, Q. RGB-T image analysis technology and application: A survey. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 120, 105919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonatti, R.; Ho, C.; Wang, W.; Choudhury, S.; Scherer, S. Towards a Robust Aerial Cinematography Platform: Localizing and Tracking Moving Targets in Unstructured Environments. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), 3–8 November 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordan, D.; Adams, M.S.; Aicardi, I.; Alicandro, M.; Allasia, P.; Baldo, M.; De Berardinis, P.; Dominici, D.; Godone, D.; Hobbs, P.; et al. The use of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) for engineering geology applications. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2020, 79, 3437–3481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Outay, F.; Mengash, H.A.; Adnan, M. Applications of unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) in road safety, traffic and highway infrastructure management: Recent advances and challenges. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2020, 141, 116–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobart, M.; Pflanz, M.; Tsoulias, N.; Weltzien, C.; Kopetzky, M.; Schirrmann, M. Fruit Detection and Yield Mass Estimation from a UAV Based RGB Dense Cloud for an Apple Orchard. Drones 2025, 9, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Wang, X.; Hu, K.; Zhou, H.; Kang, H.; Chen, C. FF3D: A Rapid and Accurate 3D Fruit Detector for Robotic Harvesting. Sensors 2024, 24, 3858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogili, U.M.R.; Deepak, B.B.V.L. Review on Application of Drone Systems in Precision Agriculture. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2018, 133, 502–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakhatreh, H.; Sawalmeh, A.H.; Al-Fuqaha, A.; Dou, Z.; Almaita, E.; Khalil, I.; Othman, N.S.; Khreishah, A.; Guizani, M. Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs): A Survey on Civil Applications and Key Research Challenges. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 48572–48634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, S.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, G. A Review on UAV-Based Remote Sensing Technologies for Construction and Civil Applications. Drones 2022, 6, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Videras Rodríguez, M.; Melgar, S.G.; Cordero, A.S.; Márquez, J.M. A Critical Review of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) Use in Architecture and Urbanism: Scientometric and Bibliometric Analysis. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 9966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomita, K.; Chew, M.Y. A Review of Infrared Thermography for Delamination Detection on Infrastructures and Buildings. Sensors 2022, 22, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukuda, R.; Fukuda, T.; Yabuki, N. Advancing Building Facade Inspection: Integration of an infrared camera-equipped drone and mixed reality. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Education and Research in Computer Aided Architectural Design in Europe, Nicosia, Cyprus, 9–13 September 2024; pp. 139–148. [Google Scholar]

- Yeom, S. Thermal Image Tracking for Search and Rescue Missions with a Drone. Drones 2024, 8, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milgram, P.; Kishino, F. A Taxonomy of Mixed Reality Visual Displays. IEICE Trans. Inf. Syst. 1994, 77, 1321–1329. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, M.-C.; Kang, S.-C. Augmented Reality and Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Assist in Construction Management. In Computing in Civil and Building Engineering (2014); Proceedings; ASCE: Reston, VA, USA, 2014; pp. 1570–1577. [Google Scholar]

- Raimbaud, P.; Lou, R.; Merienne, F.; Danglade, F.; Figueroa, P.; Hernández, J.T. BIM-based Mixed Reality Application for Supervision of Construction. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Conference on Virtual Reality and 3D User Interfaces (VR), 23–27 March 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 1903–1907. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y.; Dong, Y.; Wang, F.; Yang, J.; Cao, Y.; Li, X. Multi-sensor spatial augmented reality for visualizing the invisible thermal information of 3D objects. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2021, 145, 106634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botrugno, M.C.; D’Errico, G.; De Paolis, L.T. Augmented Reality and UAVs in Archaeology: Development of a Location-Based AR Application. In Proceedings of the Augmented Reality, Virtual Reality, and Computer Graphics, Cham; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 261–270. [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi, N.; Fukuda, T.; Yabuki, N. Future landscape visualization using a city digital twin: Integration of augmented reality and drones with implementation of 3D model-based occlusion handling. J. Comput. Des. Eng. 2022, 9, 837–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinoshita, A.; Fukuda, T.; Yabuki, N. Drone-Based Mixed Reality: Enhancing Visualization for Large-Scale Outdoor Simulations with Dynamic Viewpoint Adaptation Using Vision-Based Pose Estimation Methods. Drone Syst. Appl. 2024, 12, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Yang, T.; Ning, Y.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, Y. A Monocular Visual Odometry Method Based on Virtual-Real Hybrid Map in Low-Texture Outdoor Environment. Sensors 2021, 21, 3394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.W.; Bao, N.K. Infrared thermography and its application in the NDT of sandwich structures. Opt. Lasers Eng. 1996, 25, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, L.; Chen, M.; Zhao, W.; Zheng, D.; Cai, Y. Monocular thermal SLAM with neural radiance fields for 3D scene reconstruction. Neurocomputing 2025, 617, 129041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarlin, P.; Cadena, C.; Siegwart, R.Y.; Dymczyk, M. From Coarse to Fine: Robust Hierarchical Localization at Large Scale. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 12708–12717. [Google Scholar]

- Sattler, T.; Havlena, M.; Schindler, K.; Pollefeys, M. Large-Scale Location Recognition and the Geometric Burstiness Problem. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 27–30 June 2016; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 1582–1590. [Google Scholar]

- Lepetit, V.; Moreno-Noguer, F.; Fua, P. EPnP: An accurate O(n) solution to the PnP problem. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2009, 81, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Immersal Ltd. Immersal SDK. Available online: https://immersal.com/ (accessed on 20 December 2025).

- Niantic, I. Niantic Lightship VPS. Available online: https://lightship.dev/ (accessed on 20 December 2025).

- Google Developers. ARCore Geospatial API. Available online: https://developers.google.com/ar/develop/geospatial (accessed on 20 December 2025).

- Mur-Artal, R.; Montiel, J.M.M.; Tardós, J.D. ORB-SLAM: A Versatile and Accurate Monocular SLAM System. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2015, 31, 1147–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadena, C.; Carlone, L.; Carrillo, H.; Latif, Y.; Scaramuzza, D.; Neira, J.; Reid, I.; Leonard, J. Past, Present, and Future of Simultaneous Localization and Mapping: Towards the Robust-Perception Age; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]