Abstract

With the rapid expansion of the Internet of Things (IoT), interconnected systems are becoming increasingly vulnerable to cyberattacks, making intrusion detection essential but difficult. The marked imbalance between regular traffic and attacks, as well as the redundancy of variables from multiple sensors and protocols, greatly complicates this task. The study aims to improve the robustness of IoT intrusion detection systems by reducing the risks of overfitting and false negatives through appropriate rebalancing and variable selection strategies. We combine two data rebalancing techniques, Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE) and Random Undersampling (RUS), with two feature selection methods, LASSO and Mutual Information, and then evaluate their performance on two classification models: CatBoost and a Simple Neural Network (SNN). The experiments show the superiority of CatBoost, which achieves an accuracy of 82% compared to 80% for SNN, and confirm the effectiveness of SMOTE over RUS, particularly for SNN. The CatBoost + SMOTE + LASSO configuration stands out with a recall of 82.43% and an F1-score of 85.08%, offering the best compromise between detection and reliability. These results demonstrate that combining rebalancing and variable selection techniques significantly enhances the performance and reliability of intrusion detection systems in the IoT, thereby strengthening cybersecurity in connected environments.

1. Introduction

The Internet of Things (IoT) is one of the most significant technological revolutions of the digital age. By interconnecting billions of sensors, smart devices, and distributed applications, IoT is transforming sectors such as healthcare, industry, agriculture, logistics, and smart cities [1,2]. Recent forecasts predict that by 2034, the number of IoT connections worldwide will exceed 40 billion, generating an exponential volume of heterogeneous data [3,4]. While the integration of 5G/6G networks and cloud computing creates unprecedented opportunities for operational efficiency, it also amplifies vulnerabilities. Due to its decentralized architecture and reliance on devices constrained in processing power, memory, and energy, IoT remains highly exposed to a wide range of cyberattacks, from simple jamming to complex and persistent intrusions [5,6]. Major threats include distributed denial-of-service (DDoS), Blackhole and Greyhole attacks, packet spoofing, and protocol-level intrusions [7]. These disruptions compromise data confidentiality, integrity, and availability, and threaten critical services such as connected healthcare, smart grids, and autonomous transport systems [8].

Intrusion detection systems (IDS) have therefore become a cornerstone of IoT security. However, traditional signature- or rule-based methods quickly reach their limits in dynamic, heterogeneous environments [9]. They struggle to detect zero-day attacks, often generate high false positive rates, and cannot process large-scale data streams effectively in real time.

Artificial intelligence (AI), and particularly machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL), has emerged as a strategic approach to strengthen cybersecurity in IoT environments [10,11]. By analyzing massive datasets and automatically extracting complex patterns, these techniques enable more effective anomaly detection and intrusion classification. Yet, challenges remain: IoT data often has high dimensionality, which introduces redundancy and overfitting; deep models can be resource-intensive and ill-suited for constrained devices [12,13]; and intrusion patterns evolve rapidly, requiring adaptive methods.

To address these challenges, we propose a hybrid approach combining feature selection with joint classification using CatBoost and a Simple Neural Network (SNN). This approach focuses on three objectives: reducing data dimensionality and redundancy, improving classification accuracy and robustness, and optimizing computational efficiency for deployment on resource-limited devices.

CatBoost is well-suited for handling categorical variables, limiting prediction bias, and delivering high accuracy on complex classification tasks [14,15]. In parallel, SNN (a multilayer perceptron) provides a lightweight yet flexible architecture capable of modeling nonlinear relationships and supporting multiclass classification, while benefiting from modern deep learning frameworks for efficient training [16].

The main contributions of this study are:

- Combining two class rebalancing methods (SMOTE and RUS) with two feature selection methods (LASSO and Mutual Information) to identify the most discriminative attributes.

- Generating four distinct datasets (SMOTE + LASSO, SMOTE + Mutual Information, RUS + LASSO, RUS + Mutual Information) to assess the combined impact of rebalancing and feature selection.

- Evaluating each dataset with two complementary classifiers: CatBoost and SNN.

- Conducting a systematic comparison of all configurations to determine the best trade-off between accuracy, recall, F1-score, and robustness against class imbalance.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2: Literature Review on IoT Intrusion Detection. Section 3 introduces the materials and the proposed method. Section 4 presents the experimental results, with Section 5 providing a discussion. Section 6 presents a comparison with existing approaches, and Section 7 concludes the paper, highlighting future research directions.

2. Literature Review

Wireless networks, especially 5G and IoT systems, are vulnerable to intentional interference or jamming. Such attacks can severely disrupt operations and compromise the confidentiality and integrity of transmitted data [17]. This issue has attracted increasing research interest.

Buiya et al. investigated the use of machine learning models to detect cyberattacks in IoT network traffic. They relied on a widely used dataset that simulates both benign and malicious IoT activities [18]. Two algorithms were tested: logistic regression and random forest. Their results showed that Random Forest achieved higher accuracy and proved more effective for attack detection. Still, the dataset had some underrepresented attack types, which limited the model’s ability to detect all intrusion categories.

Jaigirdar et al. examined IoT-based healthcare systems and emphasized the lack of transparency and security awareness, which prevents users from making informed decisions about risks. They proposed integrating relevant security metadata into system design. Through expert workshops and simulated use cases, they demonstrated that metadata can increase user awareness and enhance cyber risk management [19]. However, these tests were based on controlled exercises and simulations, which may not fully reflect real-world IoT healthcare conditions.

Thawait [20] explored the transformative role of machine learning in cybersecurity. The study reviewed both theoretical foundations and practical applications while analyzing emerging threats such as adversarial attacks, data poisoning, and model inversion. It also presented defense strategies like adversarial training, robust architectures, and differential privacy. Finally, the study discussed ML applications in intrusion detection and malware classification and introduced an anomaly inference algorithm for early intrusion detection. While the contribution is significant, the approach remains theoretical mainly, with limited experimental validation. The proposed anomaly inference algorithm was not tested on diverse real-world datasets, limiting evidence of its robustness and generalizability.

In a related study, Alobaid et al. [21] categorized attack techniques and reviewed protection strategies for ANN security between 2019 and 2024. Their work provided a comprehensive analysis of multiple architectures, including DNNs, CNNs, GNNs, and SNNs, highlighting the shortcomings of current defense methods and suggesting future research directions.

Alromaihi et al. proposed an intrusion detection model based on machine learning. They integrated into a centralized proxy server capable of analyzing all incoming traffic before forwarding it to the target servers [22]. They evaluated the model using three reference datasets (CIC-MalMem-2022, CIC-IDS-2018, and CIC-IDS-2017). Results showed remarkable accuracy and speed, particularly with the XGBoost and Stacking models. XGBoost achieved detection accuracy rates of 99.96%, 99.73%, and 99.84% within short timeframes. Yet, the evaluation focused mainly on known threats in the datasets, leaving open the question of how adaptable the model would be to new and emerging cyberattacks.

Kouassi et al. examined the threat of jamming attacks in 5G mobile networks, which represent a serious challenge to communication security [23]. They developed a detection mechanism based on machine learning techniques. Their hybrid approach achieved accuracy rates ranging from 99.46% to 99.72%, confirming its effectiveness in reliably detecting jamming attacks in 5G networks. However, the system is limited in scope, as it only targets jamming and does not account for other emerging 5G threats, reducing its overall applicability in mobile cybersecurity.

To support research in IoT security, Neto et al. created a comprehensive dataset that documents 33 different attacks, including DDoS, DoS, and brute force, executed within a network of 105 IoT devices. The attacks were launched from compromised devices to other devices within the same network. This dataset, now available on the CIC Dataset website, provides a valuable benchmark for future IoT intrusion detection research [24].

Pastukh et al. analyzed the potential interference risks of 5G networks with fixed point-to-point services already operating in the 6425–7125 MHz frequency band [25]. Their simulation-based study provides practical recommendations, including minimum protection distances and frequency offsets, to facilitate efficient spectrum sharing and support regulators and businesses in deploying 5G services.

Because IoT devices are resource-constrained, the RPL protocol remains particularly vulnerable to attacks, and traditional machine learning–based intrusion detection systems often fail with IoT-specific traffic. To address this, Al Sawafi et al. [26] introduced a hybrid IDS that combines supervised and semi-supervised deep learning to detect both known and unknown abnormal behaviors. Their system was tested using IoTR-DS, a dataset designed around the RPL protocol and covering three types of attacks: DIS, Rank, and Wormhole.

Kernel audit logs are crucial for investigating cyberattacks, but their coarse granularity often produces massive attack graphs filled with spurious dependencies [27]. To address this issue, Milajerdi et al. proposed ProPatrol. This system leverages the natural compartmentalization of sensitive applications (such as browsers and email clients) to group audit events into coherent execution compartments. ProPatrol does not require source code or binary instrumentation and relies only on general application knowledge. Experiments showed that it significantly reduces dependency explosion, improves attack cause identification, and introduces less than 2% overhead. Despite its strengths, ProPatrol still faces challenges in scalability, generalization, and deployment within diverse IoT environments.

Lanni and Masciari introduced a novel approach for detecting security threats in activity logs using compact coding based on prime numbers [28]. This representation enables the use of an outlier detection algorithm to identify malicious behaviors. The experimental results validated the effectiveness of combining prime number encoding with hierarchical detection in flagging suspicious activities. However, the method becomes challenging to manage as the number of activities grows, is highly sensitive to outlier detection thresholds, and has only been validated in limited experimental scenarios, restricting its generalizability.

Jiang et al. proposed Helios, a non-standard recommendation system for large-scale security policy management [29]. Helios analyzes access logs without requiring prior knowledge of users or items. It generates categorical combinations from log labels, ranks them statistically, and recommends the most relevant anomalies. This enables the rapid detection of unknown threats, even in double-cold-start situations, while also providing explanatory visualizations for security experts. Still, the system’s performance heavily depends on the quality of log labels, can become resource-intensive with large datasets, and does not account for the operational context of users. Its robustness has also only been tested in limited scenarios.

Tayebi et al. evaluated several recurrent neural network (RNN) architectures, including LSTM, GRU, BiLSTM, and BiGRU, for intrusion detection in IoT environments [30]. Their study also tested a deep neural network (DNN) and explored the impact of attention mechanisms. Results showed that DNN-enhanced models achieved the best overall performance, outperforming both baseline and attention-based approaches. However, while effective in simulations, these DNN-enriched recurrent architectures remain computationally heavy and poorly optimized for real-time deployment on resource-constrained IoT devices.

Musthafa et al. introduced an optimization scheme for IoT intrusion detection that combines class balancing with feature selection [31]. Using the UNSW-NB15 and NSL-KDD datasets, they evaluated two ensemble models: SVM with bagging and LSTM with stacking. The LSTM stacking model, paired with ANOVA-based feature selection, delivered the best results, achieving accuracies of 96.92% and 99.77% with minimal overfitting.

Benmalek et al. proposed an anomaly-based intrusion detection system (IDS) that integrates machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) techniques to secure IoT networks [32]. Their study relied on the RT_IoT2022 dataset, which represents complex IoT attack scenarios. To optimize detection, they applied particle swarm optimization (PSO) for feature selection, reducing computational overhead while boosting performance. Multiple classifiers were tested, including SVM, KNN, CatBoost, Naive Bayes, CNN, and LSTM, with results confirming the efficiency of PSO in enhancing intrusion detection accuracy.

Taken together, these studies reflect significant progress in applying ML and DL for IoT network security. Despite promising detection rates, several limitations persist. Many models are tightly coupled to specific datasets, which restricts their ability to generalize to unknown or emerging threats [18,22]. Critical constraints, such as computation and scalability, which are essential for deployment on IoT devices, are often overlooked [19,26]. In addition, current approaches tend to specialize in narrow areas, focusing either on single attack types (for example, jamming [23]) or on generic intrusion detection, without providing a unified framework for handling diverse threats simultaneously. Class imbalance and feature extraction also remain sub-optimally addressed, limiting the detection of rare or sophisticated intrusions.

These challenges underscore the need for robust, lightweight, and scalable IDS solutions that can detect both known and novel attacks, while efficiently leveraging available information to ensure the security of critical IoT infrastructures. Table 1 summarizes existing work on attacks and intrusion detection.

Table 1.

Summary of Recent Research on IoT Intrusion Detection.

The reviewed studies highlight promising detection performances, with accuracies often exceeding 95% and F1-scores above 90% on benchmark datasets. However, most approaches remain highly dependent on specific datasets and lack generalization to unseen or emerging threats. Additionally, critical aspects such as computational overhead, scalability, and adaptability to resource-constrained IoT environments are often overlooked, which limits the practical applicability of these models in real-world deployments.

3. Materials and Proposed Method

3.1. Materials

The experiments were conducted locally on a personal computer with the following specifications:

- Processor: Intel Core i5-8130U, 2.20 GHz

- Memory: 16 GB RAM

- Storage: SSD

- Operating system: Windows 11, 64-bit

Although this setup is relatively modest for deep learning tasks, it proved sufficient given the manageable size of the dataset and the choice of models. Training was performed in batches to reduce memory usage. CatBoost is optimized for efficient CPU execution, while the SNN was designed with low resource consumption in mind. These factors enabled us to conduct all experiments without the need for a GPU.

3.1.1. Simple Neural Network (SNN)

A Simple Neural Network (SNN) is a feedforward neural network designed to model nonlinear relationships between input features and target classes. It is particularly suited for multiclass classification problems with moderate datasets, offering flexibility in layer design and low computational overhead compared to deep architectures.

- Architecture and hyperparameters:

- ✓

- Input layer: dimension = number of selected features

- ✓

- Hidden layer 1: 256 neurons, ReLU activation, Dropout 0.3

- ✓

- Hidden layer 2: 128 neurons, ReLU activation, Dropout 0.3

- ✓

- Output layer: num_classes neurons, softmax implicit via CrossEntropyLoss

- Hyperparameters:

- ✓

- Optimizer: Adam, learning rate = 0.001

- ✓

- Loss function: CrossEntropyLoss

- ✓

- Batch size: 128

- ✓

- Epochs: 100

- ✓

- Random seed: 42

- ✓

- Implementation: PyTorch version 2.8

3.1.2. CatBoost

CatBoost is a gradient boosting algorithm that handles categorical features efficiently and mitigates prediction bias. It constructs an ensemble of decision trees sequentially, optimizing a loss function (here, MultiClass) to improve accuracy and robustness. CatBoost is particularly well-suited for structured data and small to medium-sized datasets, and it is optimized to run efficiently on CPUs.

- Configuration:

- ✓

- Objective: MultiClass

- ✓

- Random seed: 42

- ✓

- Validation: Stratified 10-fold cross-validation

- ✓

- Other hyperparameters: default settings optimized for classification tasks

- ✓

- Implementation: CatBoost Python version 3.10 library, CPU optimized

3.2. Dataset

The dataset used in this study is IoTID20. Imtiaz Ullah and Qusay H. Mahmoud, researchers affiliated with the University of Guelph in Canada, developed it as part of the Canadian AI 2020 conference to meet the specific needs of cybersecurity research applied to IoT networks. This dataset contains approximately 625,783 records, each described by 86 statistical variables extracted from the network and application layers [33]. These characteristics enable a detailed analysis of flow behavior, taking into account the duration, volume, frequency, and type of protocol used. The data is divided into five categories, namely:

- Mirai: botnet attack

- Scan: port scanning

- DoS: denial of service

- MITM ARP Spoofing: man-in-the-middle attack

- Normal: legitimate activity

One of the characteristics of the IoTID20 database is the imbalance between classes, which reflects the reality of IoT networks.

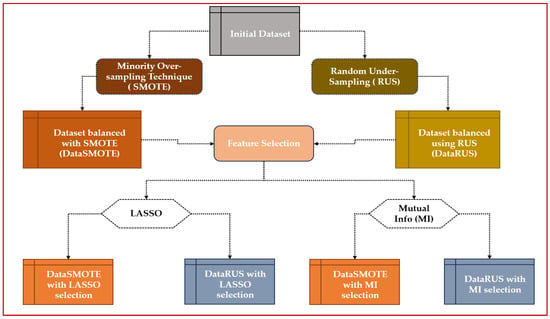

3.3. Proposed Methods

In our study, the methodology is based on a series of rigorous data preparation and transformation steps designed to enhance the representativeness and relevance of the initial dataset.

Step 1: Processing the initial dataset

We began by exploiting the raw dataset, which was characterized by an imbalance between classes. This initial state serves as an essential reference point, as it enables us to compare the impact of the subsequent rebalancing methods.

- Rebalancing classes

To remedy this imbalance, we have adopted two complementary resampling strategies:

- ✓

- SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique)

This method is based on the artificial generation of new instances belonging to the minority class. It proceeds by interpolation between neighboring observations, rather than by simple duplication, which increases the internal diversity of the under-represented class. The synthetic data obtained provides better representativeness and reduces the risk of overfitting associated with the repetition of identical examples [34].

The result is a rebalanced dataset, called DataSMOTE, which provides a more stable basis for the analysis and modeling stages.

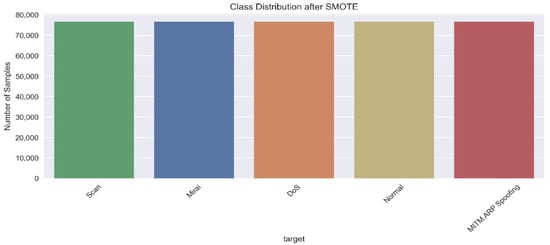

Figure 1 shows the rebalancing histogram of the dataset.

Figure 1.

Histogram of dataset rebalancing using SMOTE.

- ✓

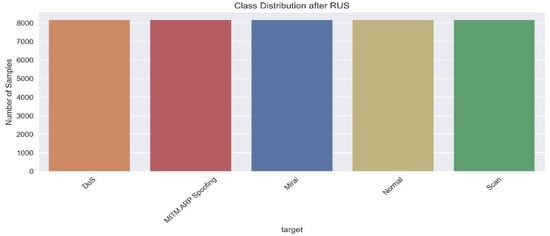

- Random Under-Sampling (RUS)

This approach involves reducing the size of the majority class by randomly selecting a subset of examples. By reducing the number of overrepresented occurrences, it mitigates the bias caused by the numerical dominance of specific categories [35].

The reduction in data volume also leads to a decrease in computational load, which can be an advantage during heavy analyses.

The resulting dataset, known as Data RUS, exhibits a more balanced distribution of classes, with each category having a comparable relative weight. Figure 2 shows the histogram of the dataset after RUS has reduced the majority classes.

Figure 2.

Histogram of dataset rebalancing by RUS.

- Selection of characteristics

Once the balanced databases had been created, a dimensionality reduction step was implemented to identify the variables that actually contributed to the prediction. Two complementary methods were used:

- ✓

- LASSO (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator)

This variable selection method is based on an L1-type regularization mechanism. The coefficients associated with the variables are constrained, gradually reducing the importance of the least relevant ones. When their contribution becomes negligible, their coefficients are reduced to zero, resulting in the automatic elimination of these variables. This process allows only the truly explanatory attributes to be retained, highlighting those that significantly influence the target variable [36].

- ✓

- Mutual Information (MI)

This technique evaluates the relevance of variables according to a statistical dependency criterion. It measures the amount of information shared between each explanatory variable and the target variable. The selected attributes are those that have the strongest informational link to the output to be predicted. Unlike some linear methods, Mutual Information is capable of detecting complex or nonlinear relationships, which enhances its ability to isolate truly informative variables [37].

- Creation of final datasets

At the end of this process, four distinct datasets were produced:

- ✓

- DataSMOTE with LASSO selection

- ✓

- DataSMOTE with mutual information selection

- ✓

- DataRUS with LASSO selection

- ✓

- DataRUS with mutual information selection

This organization facilitates the comparison of the combined influence of class rebalancing and feature selection, enabling the identification of the most effective combinations for further analysis.

Figure 3 illustrates this first step.

Figure 3.

Data pre-processing methodology.

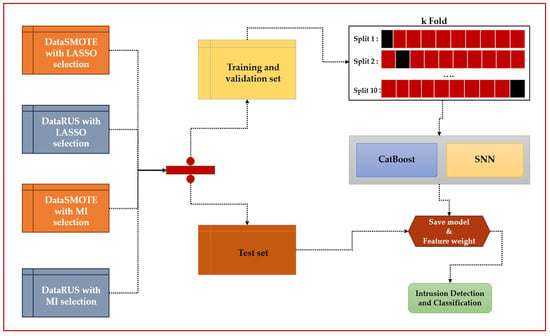

Step 2: Modeling and evaluation

The four datasets obtained at the end of the first step were then subjected to a rigorous partitioning process. Each dataset was divided into two main sets:

- ✓

- 80% dedicated to training and validation, to build and optimize the models;

- ✓

- 20% reserved for final testing, ensuring independent and impartial performance evaluation.

For the training and validation phase, we applied 10-fold cross-validation. This method consists of dividing the training/validation subset into ten equal parts, then successively rotating the roles of learning and validation data. This process has several advantages: it limits the risk of overfitting by ensuring that each observation is used for both training and validation.

- ✓

- It provides a more robust and stable estimate of model performance.

- ✓

- It facilitates comparison between different algorithm configurations.

- ✓

- In this context, two distinct algorithms were implemented:

- ✓

- CatBoost, recognized for its effectiveness in processing categorical data and its ability to reduce overfitting through gradient boosting;

- ✓

- SNN (Shallow Neural Network), an artificial neural network with a reduced architecture, allows nonlinear relationships between variables to be captured without requiring excessive model depth.

Once training and optimization were completed through cross-validation, the models underwent a final evaluation on the independent test set. This step is essential because it reflects their actual ability to detect and classify intrusions by reproducing conditions close to those found in practical applications.

Figure 4 illustrates the modeling and evaluation process.

Figure 4.

Methodology for implementing intrusion detection models.

4. Experimental Results

4.1. Evaluation Metrics

Various metrics were used to evaluate the performance of the models. These mainly included: Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-score, Matthews Correlation Coefficient, Mean Squared Error, and Confidence Interval. They were calculated using the following formulas:

- Accuracy is a performance metric that indicates how well the system correctly classifies data into the correct categories.

- Precision indicates the proportion of correctly identified attack instances among all predicted attacks. It is defined as:

- Recall is the ability of a classifier to determine true positive results.

- F1 score is the weighted average of precision and recall.

- Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC) is used in machine learning as a measure of classification quality.

TP (true positive): The number of samples that are actually positive and correctly predicted as such. TN (true negative): The number of samples that are actually negative and correctly predicted as such. FP (false positive): number of samples that are actually negative but predicted as positive. FN (false negative): number of samples that are actually positive but predicted as negative.

- The Mean Squared Error of an estimator measures the average of the squared errors, i.e., the mean square difference between the estimated values and the actual value.

In a multi-class classification context with one-hot encoding, as is the case in this work, the formula used to calculate the MSE is as follows:

where

N: number of examples (dataset or batch size); C: number of classes

probability predicted by the model that example i belongs to class c

actual value (usually one-hot encoded, i.e., 1 for the correct class and 0 otherwise)

- Confidence interval (CI) is an interval estimate of the value of an unknown parameter (e.g., a proportion, a mean, the accuracy of a classifier). It indicates a range of acceptable values for this parameter, calculated from the observed data.

The 95% confidence interval with Student’s t-distribution (n-1 degrees of freedom) is determined by:

where s is the standard deviation and n denotes the size of the sample studied (i.e., the number of observations). s expressed as follows:

and is the mean value of variable x. .

4.2. Overall Model Performance

The experimental results obtained highlight the overall performance of the models studied. The following table presents the model performance results on the final test set.

Table 2 above compares the performance of intrusion detection models based on CatBoost, combined with different data rebalancing methods (namely, SMOTE and RUS algorithms) and feature selection using LASSO and MI.

Table 2.

Summary of Model Performance on the Final Test Set.

Analysis of the results shows that:

- Case 1: SMOTE + LASSO + CatBoost

The SMOTE + LASSO + CatBoost model performs remarkably well, with an accuracy of 82.43%, the highest achieved with the SMOTE method. Its precision of 90.76% demonstrates an excellent ability to reduce false positives, while its recall of 82.43% shows a good ability to detect attacks, although there is still room for improvement. The F1 score of 85.08% reflects a good balance between precision and recall. Furthermore, the AUC reaches 97.20%, indicating the model’s excellent ability to accurately distinguish between classes. The MCC of 76.00% confirms satisfactory overall robustness. On the other hand, the model has a relatively high MSE (30.82), indicating a greater error compared to different approaches.

- Case 2: SMOTE + MI + CatBoost

The SMOTE + MI + CatBoost model performs broadly comparable to the SMOTE + LASSO approach. It achieves an accuracy of 82.43%, a precision of 90.72%, a recall of 82.43%, and an F1-score of 85.06%, confirming its ability to maintain a good balance between detection and false positive limitation. Its AUC reaches 97.00%, which is slightly lower than that obtained with SMOTE + LASSO. Still, it compensates for this difference with an MCC of 76.22%, the highest of all the models, reflecting greater robustness and stability. In addition, its MSE of 29.57 is significantly lower than that of SMOTE + LASSO, indicating a lower average error.

- Case 3: RUS + LASSO + CatBoost

The RUS + LASSO + CatBoost model achieves an accuracy of 81.39%, which is slightly lower than that obtained with SMOTE-based methods. Precision reaches 90.66%, while recall is 81.39%, leading to an F1-score of 84.24%. The AUC of 96.80% confirms a very good ability to distinguish between classes, although it remains slightly lower than that observed with SMOTE. On the other hand, the MCC index reaches 76.67%, the highest of all the configurations tested, reflecting the model’s high stability and robustness. Finally, the mean square error (MSE) stands at 29.23, indicating a relatively low error level.

Thus, this model stands out for its robustness and stability (high MCC), but remains slightly less effective than SMOTE approaches in terms of accuracy and F1-score.

- Case 4: RUS + MI + CatBoost

The RUS + MI + CatBoost model achieves an accuracy of 81.57%, which is slightly higher than that obtained with RUS + LASSO. Its precision reaches 90.69%, its recall is 81.57%, and its F1-score is 84.38%, reflecting a good balance between correct attack detection and false positive limitation. With an AUC of 96.80% and an MCC of 76.76%, this model shows remarkable robustness and excellent class distinction capability. Additionally, its MSE of 29.02 is the lowest among the tested approaches, confirming its reliability.

In summary, its main advantage lies in the optimal compromise between precision and recall, combined with a high MCC and the lowest error. However, its AUC remains slightly lower than that of SMOTE-based approaches.

Analysis of the results highlights contrasting performances depending on the approach. The SMOTE + LASSO model stands out for its excellent accuracy and high AUC; however, it also has a higher error rate, as reflected in a relatively high MSE. The SMOTE + MI model offers an interesting compromise, with a good MCC and a lower MSE, making it more robust than SMOTE + LASSO. The RUS + LASSO approach is strong thanks to a high MCC, but its performance is less satisfactory in terms of accuracy and F1-score. Finally, the RUS + MI model appears to be the most balanced, combining decent accuracy, well-adjusted recall, high MCC, and, above all, the lowest MSE, making it the most stable and reliable solution overall.

Table 3 above compares the performance of intrusion detection models based on SNN, combined with different data rebalancing methods (namely, SMOTE and RUS algorithms) and feature selection using LASSO and MI.

Table 3.

Presents various results obtained from the SNN model.

- Case 5: SMOTE + LASSO + SNN

The SMOTE + LASSO + SNN model has an accuracy of 80.87%, reflecting good overall precision. Its precision reaches 89.84%, its recall is 80.87%, and its F1-score is 83.67%, showing a good balance between the ability to detect intrusions and limit false positives. With an AUC of 96.6% and an MCC of 78.40%, it demonstrates excellent separation power between classes and high robustness. In addition, its MSE of 27.71%, the lowest among all approaches, confirms better error minimization. This model stands out for its very satisfactory overall balance and its ability to effectively reduce error, even though its F1-score remains slightly lower than that of the other configurations tested.

- Case 6: SMOTE + MI + SNN

The SMOTE + MI + SNN model has an accuracy of 80.55%, close to that obtained with SMOTE + LASSO. Its precision reaches 90.31%, while its recall is 80.55%, resulting in an F1 score of 83.58%, reflecting a good compromise between correct attack detection and false positive limitation. The AUC is 97.0%, the highest value of all the results, confirming an excellent ability to distinguish between classes. The MCC is 77.40%, demonstrating satisfactory robustness, while the MSE is 28.41, slightly higher than that of SMOTE + LASSO.

Thus, this model stands out mainly for its exceptional AUC, which guarantees excellent class differentiation; however, it suffers from a slightly higher error rate and somewhat lower robustness compared to some other approaches.

- Case 7: RUS + LASSO + SNN

The RUS + LASSO + SNN model achieved an accuracy of 78.61%, the lowest among the different combinations tested. Its precision reached 90.12%, but its recall, also 78.61%, remained limited, which reduced its ability to identify all intrusions correctly. Nevertheless, the F1 score of 81.96% represents an acceptable compromise between precision and recall. With an AUC of 96.0% and an MCC of 77.60%, the model demonstrates adequate robustness and a good ability to separate classes. However, its MSE of 28.54, one of the highest in the table, indicates room for improvement in terms of overall error. This model stands out for its solid F1-score and good robustness, but remains less effective than SMOTE-based approaches in terms of accuracy and recall.

- Case 8: RUS + MI + SNN

The RUS + MI + SNN approach performs well in the classification studied. It achieves an accuracy of 79.20%, with an equivalent recall (79.20%) and high precision of 89.57%, resulting in an F1 score of 82.40%. These values indicate that the model accurately identifies a substantial proportion of positive classes while minimizing false alarms, thereby offering a suitable compromise between precision and recall. The AUC of 96% and the MCC of 77.30% confirm that the model has an excellent ability to distinguish between different classes and that its prediction is generally reliable. In addition, the MSE of 28.32 indicates a slight improvement over the RUS + LASSO combination, suggesting that the use of MI (Mutual Information) as a feature selection method provides better predictive quality.

Nevertheless, despite these strengths, the RUS + MI + SNN approach remains overall less effective than combinations incorporating SMOTE, which appear to handle class imbalance better and enhance overall accuracy. In summary, this method is robust and balanced; however, it does not achieve the level of effectiveness attained by techniques based on synthetic oversampling. The performance of the different classification models applied to network traffic classes or attack types using the CatBoost algorithm is presented in Table 4. The results obtained with the SNN algorithm are summarized in Table 5.

Table 4.

Performance achieved with the CatBoost algorithm.

Table 5.

Performance achieved with the SNN algorithm.

The evaluation of detection models shows highly variable performance, depending on the nature of the attack considered, which reflects both the strengths and limitations of the approaches used.

For the DoS class, the results are almost perfect, with accuracy greater than or equal to 99.80%, recall around 99.50%, an F1-score of 99.60%, and an AUC of 100%. These figures show that the detection of DoS attacks is a problem that the system effectively addresses. The highly distinctive characteristics of this type of attack facilitate learning and recognition by the models, regardless of the algorithm or method used.

On the other hand, for the ‘MITM ARP Spoofing’ class, performance appears more mixed. Recall shows a minimum value of 74.03% and a maximum value of 81.25%. As for the AUC, a score ranging from 92.00% to 94.00% is observed. Accuracy drops from 27.35% to 32.98%. The F1 score, around 45%, reflects this imbalance. The SMOTE + MI and RUS + MI combinations offer slight improvements, but the differences remain marginal. Overall, detection is effective in signaling the presence of MITM attacks, but it lacks reliability in classifying positive instances.

The detection of the ‘Mirai’ class presents a different dynamic: the models achieve a very high accuracy of around 99% and an AUC close to 97%, which significantly reduces false alarms. However, recall is more modest, with a score between 74% and 78%, indicating that some Mirai attacks still escape the system. Nevertheless, the F1-score remains satisfactory, ranging from 86% to 88%. The use of SMOTE slightly improves the results by increasing recall compared to RUS, confirming the value of oversampling for this minority class. Performance is also excellent for the ‘Normal’ class. The accuracy ranges from 97% to 98%, and the AUC reaches approximately 99%. Among the methods, RUS + LASSO stands out as the most balanced, with an F1-score of 97.1%, combining high accuracy of 96.9% and robust recall of 97.3%. SMOTE-based approaches, although showing slightly higher accuracy, lose recall, which degrades their F1-score to 94.6%. RUS + MI achieves intermediate results of 94.1%. Finally, for the ‘Scan’ class, performance is more mixed. Recall scores range from 60.00% to 70.89% with low precision ranging from 38.02% to 43.63%, resulting in an excess of false positives. An F1 score ranging from 47.47% to 75.40% is observed for this class. The AUC values confirm the models’ good discrimination capacity, but do not compensate for the imbalance observed between precision and recall.

4.3. 95% Confidence Intervals for Performance Metrics of CatBoost and SNN Models

A 95% confidence interval is a statistical tool used to assess the reliability of an estimate. This range of values, calculated from a sample of data, is estimated with a 95% confidence level to contain the true value of the parameter being studied. The results of confidence intervals for the performance measurements of our CatBoost and SNN models are presented in the following tables.

Table 6 presents the 95% confidence intervals for the primary metrics of the different CatBoost configurations combining rebalancing methods (SMOTE, RUS) and feature selection methods (LASSO, Mutual Information). We observe that:

Table 6.

CatBoost: 95% Confidence Intervals for Accuracy, F1-score, Precision, and Recall.

- The SMOTE + LASSO and SMOTE + MI configurations achieve the highest accuracy and F1-score intervals, confirming the robustness of performance across all validation folds.

- The precision ranges are particularly high ([90.36–91.12]%), highlighting CatBoost’s ability to limit false positives.

- The difference between RUS and SMOTE is small but significant, indicating a slight advantage for oversampling methods for this dataset.

Table 7 presents the 95% confidence intervals for the main metrics of the SNN configurations, also combining rebalancing and feature selection. We note that:

Table 7.

Simple Neural Network (SNN): 95% Confidence Intervals for Accuracy, F1-score, Precision, and Recall.

- The SMOTE + LASSO and SMOTE + MI configurations offer higher intervals for accuracy and F1-score, showing the positive effect of oversampling for simple networks.

- Accuracy is slightly lower than that of CatBoost, indicating greater variability in false positives for SNN.

- The intervals are broader than those of CatBoost, indicating greater variability across validation splits and less stable results.

4.4. Visualization of Model Graphs

For an overall assessment of our different models, we used two complementary tools: the ROC curve and the confusion matrix.

On the one hand, the ROC (Receiver Operating Characteristic) curve provides a more comprehensive view of the classifier’s discriminatory power. The areas under the curve (AUC) obtained indicate very satisfactory performance, reflecting a good compromise between the true positive rate (sensitivity) and the false positive rate (specificity). The closer the curve is to the upper left corner, the higher the classification quality, which is the case in our results.

In short, the combination of the confusion matrix and the ROC curve highlights the robustness of our CatBoost model, while emphasizing the classes for which improvements are still needed to reduce residual confusion.

On the other hand, the confusion matrix allows for detailed analysis of the model’s predictions by comparing them to the actual classes. The results show that the model can effectively distinguish between most categories, with particularly high recognition rates for the DoS, Mirai, Normal, and Scan classes. However, some confusion remains, particularly between MITM ARP Spoofing and Mirai attacks, suggesting that the behavioral signatures of these two types of traffic are similar. Despite these errors, the main diagonal of the matrix remains largely dominant, reflecting the model’s overall reliability. The following figures illustrate the ROC curves and confusion matrices of our different models.

- With the CatBoost algorithm

The evaluation of the CatBoost algorithm with different resampling and feature selection strategies is presented below.

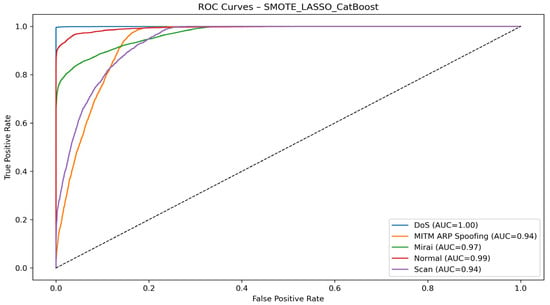

Figure 5 shows the ROC curve of the CatBoost model trained on the dataset processed with SMOTE and LASSO feature selection. Overall, the results highlight the strong discriminating power of the CatBoost algorithm combined with SMOTE and LASSO. All classes achieve AUCs greater than 0.94, confirming that the model is capable of reliably classifying both attacks and normal traffic.

Figure 5.

SMOTE + LASSO + Catboost ROC curve.

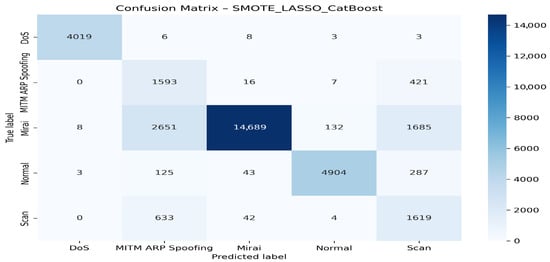

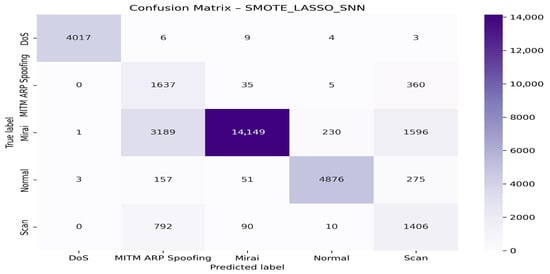

Figure 6 presents the corresponding confusion matrix for the SMOTE + LASSO + CatBoost model.

Figure 6.

Confusion matrix for the SMOTE + LASSO + CatBoost model.

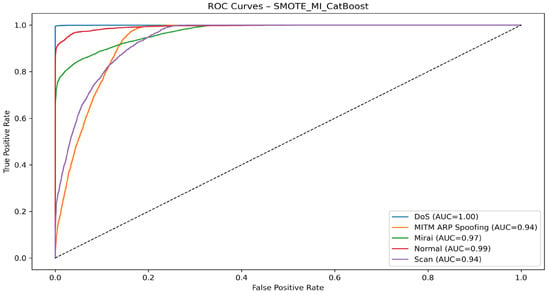

Figure 7 illustrates the ROC curves corresponding to the detection of different classes (DoS, MITM ARP Spoofing, Mirai, Normal, and Scan), obtained using the SMOTE + Mutual Information + CatBoost approach. With AUC values between 0.94 and 1.00, the model shows high robustness, good generalization, and resistance to classification errors, confirming the effectiveness of the adopted protocol.

Figure 7.

SMOTE + MI + CatBoost ROC curve.

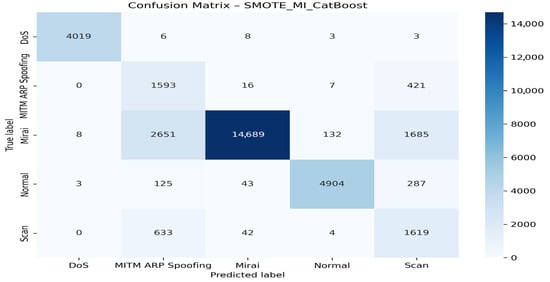

Figure 8 displays the confusion matrix associated with this configuration.

Figure 8.

Confusion matrix for the SMOTE + MI + CatBoost model.

This matrix compares actual values with predicted values. It allows the model’s ability to correctly classify each type of traffic or attack to be evaluated. The overall analysis of the confusion matrix highlights both the strengths and limitations of the SMOTE_MI_CatBoost model. On the one hand, the model performs exceptionally well in detecting DoS and Mirai attacks, achieving a very high recognition rate. The Normal class is also well identified, with a relatively low number of classification errors, demonstrating the model’s ability to distinguish benign traffic from attacks effectively.

On the other hand, specific weaknesses are notable, notably a marked confusion between MITM ARP Spoofing, Scanning, and Mirai attacks. This difficulty reflects the substantial similarity in the characteristics of these attacks, which the model struggles to differentiate accurately. Thus, although the model performs very well overall, optimization efforts are still needed to improve the separation between these similar types of attacks.

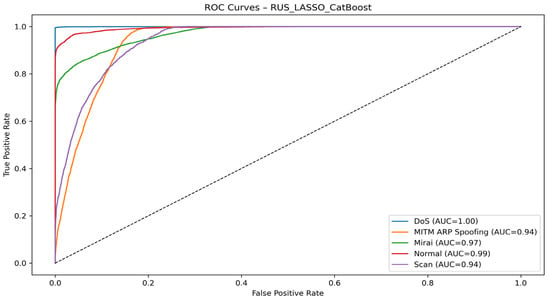

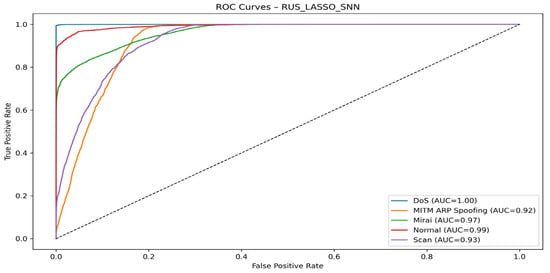

Figure 9 illustrates the performance of the RUS_LASSO_CatBoost model.

Figure 9.

RUS + LASSO + CatBoost ROC curve.

The RUS_LASSO_CatBoost model demonstrates excellent discriminatory power with very high AUC values for all classes. DoS attacks are detected perfectly (AUC = 1.00), while normal traffic is also very well recognized (AUC = 0.99). Mirai attacks also yield very good results (AUC = 0.97), confirming the model’s accuracy. On the other hand, the MITM ARP Spoofing and Scan classes show slightly lower performance (AUC = 0.94). This suggests a certain similarity between their signatures, making it more challenging to differentiate them.

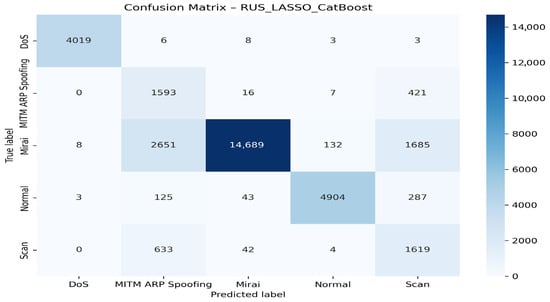

Figure 10 displays the confusion matrix associated with this configuration.

Figure 10.

Confusion matrix for the RUS + LASSO + CatBoost model.

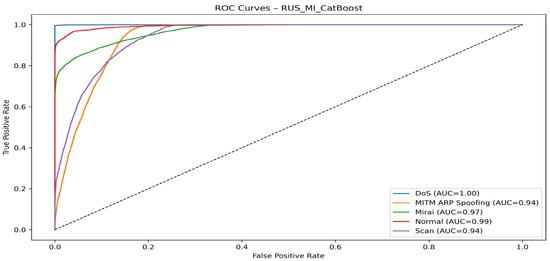

Figure 11 highlights the ROC curve of the RUS_MI_CatBoost model.

Figure 11.

RUS_MI_CatBoost model ROC curve.

The RUS_MI_CatBoost model demonstrates remarkable and robust performance, with near-perfect results for DoS, Mirai, and Normal attacks. However, there is room for improvement in more finely differentiating between MITM ARP Spoofing and Scan attacks.

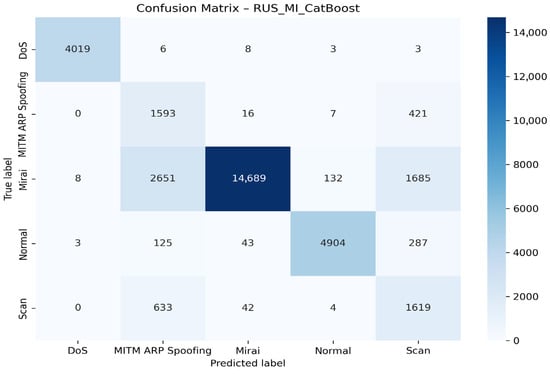

Figure 12 presents the confusion matrix of the RUS_MI_CatBoost model

Figure 12.

Confusion matrix for the RUS + MI + CatBoost model.

The DoS class is detected very well, with 4019 instances correctly classified and a near-perfect rate. The Mirai class is also well recognized (14,689 cases), but with notable confusion with MITM ARP Spoofing and Scan. The Normal class is robust with 4904 correct detections and limited errors. On the other hand, MITM ARP Spoofing and Scan show high mutual confusion, reflecting the similarity of their network signatures. Overall, the model performs well but remains limited in distinguishing between similar attacks such as MITM ARP Spoofing, Scan, and Mirai.

- With the SNN algorithm

Similarly, the performance of the SNN algorithm is assessed under the same experimental settings.

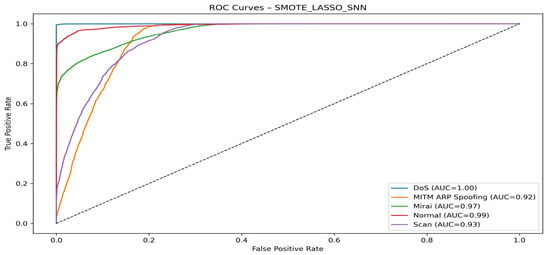

Figure 13 presents the ROC curve for the SMOTE + LASSO + SNN model.

Figure 13.

SMOTE + LASSO + SNN ROC curve.

Figure 13 shows the ROC curve for the SMOTE + LASSO + SNN model. With AUCs above 0.92 for all classes, the model demonstrates excellent ability to classify attacks and normal traffic.

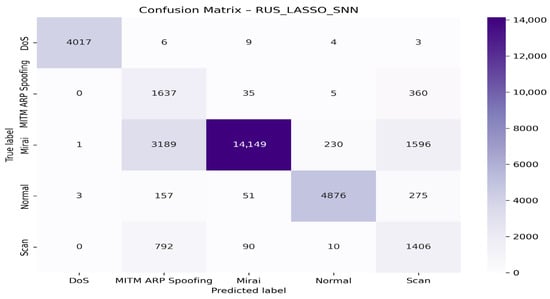

To evaluate the performance of the SMOTE_LASSO_SNN classification model, a confusion matrix was generated, considering five distinct classes: DoS, MITM ARP Spoofing, Mirai, Normal, and Scan. This matrix enables us to observe the distribution of correct and incorrect predictions in relation to the true labels and those predicted by the model. The main diagonal of the matrix represents correct predictions, i.e., when the predicted class is identical to the actual class. We observe that:

The DoS is correctly identified in 4017 cases, demonstrating the model’s excellent ability to detect this type of attack.

Normal is also well recognized, with 4876 correct predictions.

The Mirai class, although widely represented with 14,149 correct predictions, shows significant confusion with MITM ARP Spoofing (3189 cases) and Scan (1596 cases).

MITM ARP Spoofing is correctly classified in 1637 cases, but is often confused with the Scan class (360 cases).

Finally, the Scan class is predicted correctly in 1406 cases, but is highly confused with MITM ARP Spoofing (792 cases).

Figure 14 illustrates the corresponding confusion matrix.

Figure 14.

Confusion matrix for the SMOTE + LASSO + SNN model.

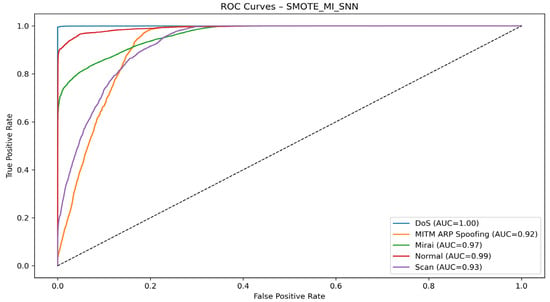

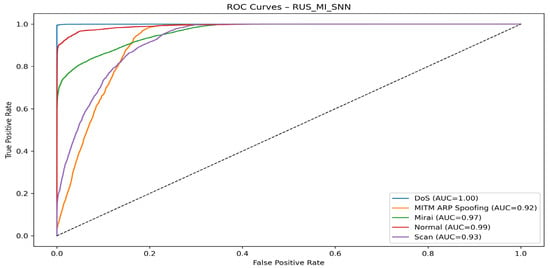

Figure 15 shows the ROC curve obtained with SMOTE + MI + SNN.

Figure 15.

SMOTE + MI + SNN model ROC curve.

Figure 16 presents the confusion matrix for this model.

Figure 16.

Confusion matrix for the SMOTE + MI + SNN model.

The model shows excellent class discrimination ability, with all AUCs above 0.90 and perfect detection of the DoS class (AUC = 1.00). The MITM ARP Spoofing and Scan classes perform slightly less well but remain reliable. The use of SMOTE combined with Mutual Information allowed for good class separation despite the imbalance, ensuring high accuracy for DoS, Normal, and Mirai.

Figure 17 depicts the ROC curve for RUS + LASSO + SNN.

Figure 17.

RUS + LASSO + SNN model ROC curve.

All classes achieve an AUC ≥ 0.92, indicating a very good overall ability of the model to distinguish between different classes.

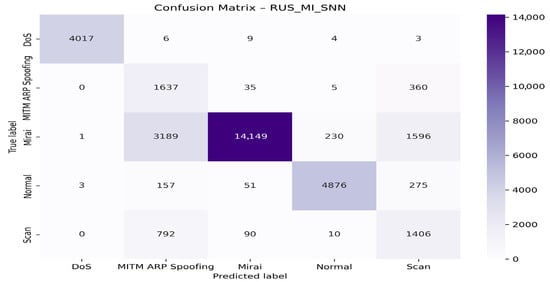

Figure 18 presents the confusion matrix for the RUS + LASSO + SNN model.

Figure 18.

Confusion matrix for the RUS + LASSO + SNN model.

The RUS_LASSO_SNN model performs exceptionally well for the DoS and Normal classes, with a high rate of correct predictions and minimal confusion. However, it shows significant confusion between the Mirai, MITM ARP Spoofing, and Scan classes, suggesting a similarity in the characteristics of these types of attacks, which remain difficult to distinguish even after variable selection via LASSO.

Figure 19 presents the ROC curve for the RUS + MI + SNN model.

Figure 19.

RUS + MI + SNN model ROC curve.

The RUS_MI_SNN model exhibits excellent classification performance, with AUC values exceeding 0.90 for all classes. Separation is excellent for DoS, Normal, and Mirai, but more difficult for MITM ARP Spoofing and Scan, confirming the trends observed in the other configurations tested.

Figure 20 displays the corresponding confusion matrix.

Figure 20.

Confusion matrix for the RUS + MI + SNN matrix model.

The RUS_MI_SNN model effectively distinguishes between the DoS and Normal classes, achieving a high correct classification rate. However, the Mirai, MITM ARP Spoofing, and Scan classes still exhibit notable cross-classification errors, indicating that these attacks share overlapping characteristics that remain difficult to separate even after applying variable selection with Mutual Information (MI). The main confusions occur between Mirai and MITM ARP Spoofing, MITM ARP Spoofing and Scan, and Mirai and Scan.

5. Discussion

Analysis of the performance of CatBoost and SNN models, considering different combinations of balancing techniques (SMOTE and RUS) and feature selection methods (LASSO and Mutual Information), reveals several interesting observations. CatBoost generally outperforms SNN on most metrics, particularly in terms of accuracy (82% versus 80%). This superiority can be attributed to CatBoost’s intrinsic ability to capture complex relationships between variables and to mitigate overfitting through its gradient boosting mechanism. SNN, although competitive, remains limited by its reduced depth, which restricts its representation capacity.

The choice of balancing techniques also plays a decisive role. For CatBoost, the gap between SMOTE and RUS remains modest, though SMOTE achieves slightly better accuracy (82.43% compared to 81.39% with RUS when paired with LASSO). This improvement stems from SMOTE’s ability to generate diverse synthetic examples for the minority class, thereby enriching data representation and stabilizing the model. For SNN, the contrast is sharper: accuracy reaches 80.9% with SMOTE, but falls to 78.6% with RUS. The reduction performed by RUS appears too severe, depriving the model of valuable training information and limiting its generalization ability.

Regarding feature selection, both LASSO and Mutual Information produce comparable results. With CatBoost, the differences are marginal, though MI slightly improves prediction stability, with an MCC of 76.76% compared to 76.00% for LASSO, and reduces the MSE (29.02% versus 30.82%). SNN follows the same trend, as both methods yield nearly identical outcomes, yet MI achieves a better balance between recall and MCC. This is especially critical in intrusion detection, where reducing false negatives (undetected attacks) is more important than simply minimizing false positives.

Beyond predictive performance, practical considerations such as model size, memory footprint, and computational efficiency further highlight the trade-offs between CatBoost and SNN. CatBoost consists of approximately 500 trees with an average depth of 6, corresponding to a size of roughly 20–25 MB. In contrast, the SNN, with two hidden layers of 256 and 128 neurons stored in float32, requires only 3–5 MB. This makes SNN considerably lighter and more suitable for deployment on resource-constrained IoT devices. Training time also reflects this difference: CatBoost completes training in about 5 to 10 min on CPU, while SNN takes slightly longer (8 to 12 min). However, inference is faster with SNN, ranging from 0.5 to 1 ms per instance compared to 1–2 ms for CatBoost, which opens the door to near real-time execution on microcontrollers or mini-PCs. Strategies to further reduce complexity exist for both models. CatBoost can be optimized by reducing the number or depth of trees, applying quantization, or relying on lightweight variants tailored for embedded systems. SNN can benefit from pruning, weight quantization, or compact architectures with fewer parameters, without necessarily compromising accuracy.

Finally, global analysis of the metrics confirms the robustness of both models. Precision consistently hovers around 90%, which is essential in cybersecurity contexts where an excess of false alarms could overwhelm monitoring teams and erode trust in the system. Recall remains slightly lower, between 78% and 82%, which means inevitable intrusions still go undetected. Among all tested configurations, CatBoost combined with SMOTE and LASSO emerges as the most effective compromise, achieving a recall of 82.43% and an F1-score of 85.08%, thereby providing the best balance between detection capacity, computational efficiency, and prediction stability.

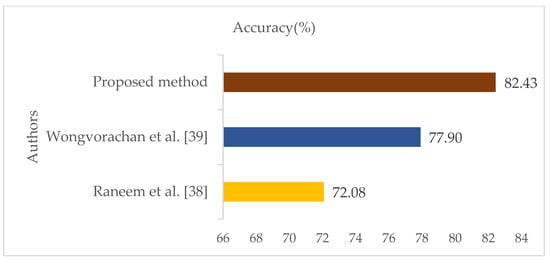

6. Comparison with Existing Approaches

Table 8 presents the results obtained from our approaches and those from previous work. Figure 21 presents a histogram comparing the results with those of the state-of-the-art. A comparison was made between the SMOTE + LASSO + CatBoost (SLC) system proposed in this work and the methods used by other researchers in the field of IoT intrusion detection, using the IoTID20 dataset. The results show that our system, SMOTE + LASSO + CatBoost, outperforms the approaches of different authors.

Table 8.

Comparison of accuracy with existing results for the IoTID20 dataset.

Figure 21.

Comparison of Histogram of works [38,39].

These results demonstrate the superiority of our SMOTE + LASSO + CatBoost system compared to existing methods in terms of intrusion detection accuracy in an IoT environment, as described in the IoTID20 database. The hybrid approaches developed in this article are based on statistical feature selection, the CatBoost gradient boosting algorithm, and Simple Neural Networks (SNN). Statistical selection was an essential step in reducing the dimensionality of the data while preserving the relevant discriminating variables. CatBoost, with its ability to process heterogeneous and noisy data, ensured accurate and robust classification. At the same time, SNNs, inspired by biological neural mechanisms, introduced efficiency and temporal processing capabilities particularly suited to the constraints of IoT devices.

Compared to the other models in Table 5, LASSO + CatBoost offers better performance, strengthening the security of IoT infrastructures and ensuring more effective protection against intrusions.

These results also encourage further research in this field, as they pave the way for future work or new approaches to detecting intrusions due to increasingly sophisticated attacks.

7. Conclusions and Future Work

The Internet of Things (IoT) is now an essential pillar of digital ecosystems, with applications ranging from connected health to smart cities and Industry 4.0. However, this continued expansion, amplified by the deployment of 5G and 6G networks and cloud computing, is accompanied by a significant increase in the attack surface, exposing IoT networks to increasingly complex intrusions and threats. Traditional intrusion detection approaches, often based on signatures or rules, are proving insufficient in the face of the variation and heterogeneity of IoT environments.

In this context, this study proposes a hybrid solution that combines statistical feature selection to reduce dimensionality and balance the data, the CatBoost gradient boosting algorithm, and Simple Neural Networks (SNN). The results demonstrate the overall superiority of CatBoost, with an accuracy of 82% compared to 80% for SNN, due to its ability to handle complex relationships and mitigate overfitting. The effect of balancing techniques is significant: SMOTE improves performance by generating representative synthetic examples, particularly for SNN (80.9% vs. 78.6% for RUS). The CatBoost + SMOTE + LASSO configuration stands out as the most effective, achieving a recall of 82.43% and an F1-score of 85.08%, thus constituting the best compromise between detection and reliability. This study emphasizes the significance of synergies among statistical methods, boosting models, and simple neural networks in developing intelligent and resilient intrusion detection systems, thereby enhancing the security and reliability of IoT infrastructures in the face of emerging threats.

Future work could enhance the practical applicability and robustness of the proposed approach by extending the evaluation to other IoT datasets or synthetic environments, thereby verifying the generalizability of the results. It would also be relevant to analyze computational efficiency, taking into account memory consumption and inference latency, to facilitate deployment on constrained IoT devices. Finally, exploring more advanced or hybrid deep learning models capable of integrating temporal dimensions or graph structures would provide a better understanding of the complexity of patterns specific to IoT traffic.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.M.K. and K.J.A.; methodology, B.M.K. and K.J.A.; software, Y.D. and K.J.A.; validation, K.J.A. and D.M.; formal analysis, B.M.K. and A.B.B.; investigation, B.M.K. and A.B.B.; resources, K.J.A.; data curation, K.J.A.; writing—original draft preparation, B.M.K., A.B.B., and K.J.A.; writing—review and editing, K.J.A., Y.D.; visualization, Y.D.; supervision, K.J.A. and D.M.; project administration, D.M.; funding acquisition, D.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset employed in this paper can be retrieved online from: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/rohulaminlabid/iotid20-dataset (accessed on 2 June 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ullah, S.; Ahmad, J.; Khan, M.A.; Alkhammash, E.H.; Hadjouni, M.; Ghadi, Y.Y.; Saeed, F.; Pitropakis, N. A New Intrusion Detection System for the Internet of Things via Deep Convolutional Neural Network and Feature Engineering. Sensors 2022, 22, 3607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awajan, A.A. A Novel Deep Learning-Based Intrusion Detection System for IoT Networks. Computers 2023, 12, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prisca, R. Ecosystème IoT. Available online: https://www.objetconnecte.com/les-connexions-iot-mondiales-devraient-depasser-40-milliards-dici-2034/ (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Lionel, S.V. Number of Internet of Things (IoT) Connections Worldwide from 2022 to 2023, with Forecasts from 2024 to 2034. Statista, 2025. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1183 (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Hela, M.; Abir, H.K.; Lamia, C.F. A Comprehensive Survey on Intrusion Detection based Machine Learning for IoT Networks. ICST Trans. Secur. Saf. 2021, 21, e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Shakil, S.A.; Mustakim, M.R. A survey on intrusion detection system in IoT networks. Cyber Secur. Appl. 2025, 3, 100082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhukabayeva, T.; Zholshiyeva, L.; Mardenov, Y.; Buja, A.; Khan, S.; Alnazzawi, N. Real-Time Detection and Response to Wormhole and Sinkhole Attacks in Wireless Sensor Networks. Technologies 2025, 13, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, M.; Tariq, N.; Ashraf, M.; Khan, F.A.; Asim, M.; Imran, M. Securing Smart Healthcare Cyber-Physical Systems against Blackhole and Greyhole Attacks Using a Blockchain-Enabled Gini Index Framework. Sensors 2023, 23, 9372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikissagbe, B.R.; Adda, M. Machine Learning-Based Intrusion Detection Methods in IoT Systems: A Comprehensive Review. Electronics 2024, 13, 3601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dritsas, E.; Trigka, M. A Survey on Cybersecurity in IoT. Future Internet 2025, 17, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyamfi, E.; Jurcut, A. Intrusion Detection in Internet of Things Systems: A Review on Design Approaches Leveraging Multi-Access Edge Computing, Machine Learning, and Datasets. Sensors 2022, 22, 3744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubaba, R.; Majed, A.; Abdullah, A.; Shtwai, A.; Binbusayyis, A.; Bukhari, S.A.C. Analysis of dimensionality reduction techniques on Internet of Things data using machine learning. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2022, 52, 102304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adedeji, K.B.; Abu-Mahfouz, A.M.; Kurien, A.M. DDoS Attack and Detection Methods in Internet-Enabled Networks: Concept, Research Perspectives, and Challenges. J. Sens. Actuator Netw. 2023, 12, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawahib, S.A.B.; Nithinsha, S.; Preethi, R.; Najla, B.; Niyasudeen, F.; Jezna, A.J.P. Enhancing IoT Network Attack Detection with Ensemble Machine Learning and Efficient Feature Extraction. J. Inf. Syst. Eng. 2025, 10, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Hancock, J.T.; Khoshgoftaar, T.M. CatBoost for big data: An interdisciplinary review. J. Big Data 2020, 7, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, L.; Yu, Z. The Difference of Simple Neural Networks in Testing Penetration Speed. Contemp. Educ. Front. 2025, 3, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghware, F.O.; Ogala, J.O. Jamming and anti-jamming solutions for 5G and IoT. Dutse J. Pure Appl. Sci. 2024, 10, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buiya, M.R.; Laskar, A.N.; Islam, M.R.; Sawalmeh, S.K.S.; Roy, M.S.R.C.; Roy, R.E.R.S.; Sumsuzoha, M. Detecting IoT cyberattacks: Advanced machine learning models for enhanced security in network traffic. J. Comput. Sci. Technol. Stud. 2024, 6, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaigirdar, F.T.; Rudolph, C.; Anwar, M.; Tan, B. Empowering End-Users with Cybersecurity Situational Awareness: Findings from IoT-Health Table-Top Exercises. J. Cybersecur. Priv. 2025, 5, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thawait, N.K. Machine learning in cybersecurity: Applications, challenges and future directions. Int. J. Sci. Res. Comput. Sci. Eng. Inf. Technol. 2024, 10, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alobaid, A.; Talal, B.; Maher, A. Disruptive attacks on artificial neural network: A systematic review of attack techniques, detection methods, and protection srategies. Intell. Syst. Appl. 2025, 26, 200529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alromaihi, N.; Rouached, M.; Akremi, A. Design and Analysis of an Effective Architecture for Machine Learning Based Intrusion Detection Systems. Network 2025, 5, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouassi, B.M.; Monsan, V.; Ballo, A.B.; Kacoutchy, J.A.; Mamadou, D.; Adou, K.J. Application of the learning set for the detection of jamming attacks in 5g mobile networks. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2023, 14, 715–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, E.C.P.; Dadkhah, S.; Ferreira, R.; Zohourian, A.; Lu, R.; Ghorbani, A.A. CICIoT2023: A Real-Time Dataset and Benchmark for Large-Scale Attacks in IoT Environment. Sensors 2023, 23, 5941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pastukh, A.; Tikhvinskiy, V.; Devyatkin, E.; Kulakayeva, A. Sharing Studies between 5G IoT Networks and Fixed Service in the 6425–7125 MHz Band with Monte Carlo Simulation Analysis. Sensors 2022, 22, 1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Sawafi, Y.; Touzene, A.; Hedjam, R. Hybrid Deep Learning-Based Intrusion Detection System for RPL IoT Networks. J. Sens. Actuator Netw. 2023, 12, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milajerdi, S.M.; Eshete, B.; Gjomemo, R.; Venkatakrishnan, V.N. Propatrol: Attack investigation via extracted high-level tasks. In International Conference on Information Systems Security; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 107–126. [Google Scholar]

- Ianni, M.; Masciari, E. Scout: Security by computing outliers on activity logs. Comput. Secur. 2023, 132, 103355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Algatt, S.; Ahammad, P. A recommender system for efficient discovery of new anomalies in large-scale access logs. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1610.08117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayebi, M.; El Kafhali, S. Performance Analysis of Recurrent Neural Networks for Intrusion Detection Systems in Industrial-Internet of Things. Franklin Open 2025, 12, 100310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musthafa, M.B.; Huda, S.; Kodera, Y.; Ali, M.A.; Araki, S.; Mwaura, J.; Nogami, Y. Optimizing IoT Intrusion Detection Using Balanced Class Distribution, Feature Selection, and Ensemble Machine Learning Techniques. Sensors 2024, 24, 4293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benmalek, M.; Seddiki, A. Particle swarm optimization-enhanced machine learning and deep learning techniques for Internet of Things intrusion detection. Data Sci. Manag. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samir, F.; Fouzi, S. Smart Intrusion Detection in IoT Edge Computing Using Federated Learning. Rev. D’intelligence Artif. 2023, 37, 1133–1145. Available online: http://iieta.org/journals/ria (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Nur, A.A.; Muhammad, S.M.P.; Aniza, M.D.; Adam, J. An Investigation of SMOTE Based Methods for Imbalanced Datasets with Data Complexity Analysis. Available online: https://www.ieee.org/publications/rights/index.html (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Haseeb, A.; Mohd, N.M.S.; Kashif, H.; Arshad, A.; Ayaz, U.; Arshad, M.; Rashid, N.; Muzammil, K. A review on data preprocessing methods for class imbalance problem. Int. J. Eng. Technol. 2019, 8, 390–397. Available online: https://www.sciencepubco.com/index.php/ijet/article/view/29508 (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Ernesto, C.; David, D.G.; Danae, C. Neural lasso: A unifying approach of lasso and neural networks. Int. J. Data Sci. Anal. 2025, 20, 1485–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilberto, C.; Gabriel, M.F.F.; Thomas, M.L. Mutual Information as a General Measure of Structure in Interaction Networks. Entropy 2020, 22, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raneem, Q.; Al-Zoubi, A.M.; Faris, H.; Almomani, I. A Multi-Layer Classification Approach for Intrusion Detection in IoT Networks Based on Deep Learning. Sensors 2021, 21, 2987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongvorachan, T.; He, S.; Bulut, O. A Comparison of Undersampling, Oversampling, and SMOTE Methods for Dealing with Imbalanced Classification in Educational Data Mining. Information 2023, 14, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).