Abstract

The article deals with family language policy (FLP) among Estonian families in Finland. The focus is on language beliefs concerning maintenance of Estonian and Estonian home language (HL) classes provided by municipalities free of charge. Using the classical three-component model of FLP by Spolsky (language beliefs, language management, language practices), the analysis concentrates on language beliefs (the importance of Estonian and HL education) and management (real actions that enable children’s involvement in HL classes). The data were collected from eight Estonian families via semi-structured interviews. The caregivers have higher education and stable incomes. All participants emphasized the importance of proficiency in Estonian for their ethnolinguistic identity and the beneficial aspects of HL classes. However, we found discrepancies between beliefs and actual behavior: the children do not attend Estonian HL classes because of complicated logistics and, according to the caregivers, poor language teaching methods (this claim is not supported by any evidence). Such discrepancies between beliefs and management have been attested in various recent studies of other minorities.

1. Introduction

The objective of the current study is to investigate attitudes to the option of home language instruction among Estonian diaspora families in Finland. The study is conducted within the framework of Family Language Policy (FLP) research.

Estonia and Finland are situated geographically close and their languages are closely related, belonging to the Finnic branch of the Uralic language family. Both peoples have a history of cultural connections. The number of Estonian background migrants has increased in Finland especially due to the enlargement of the European Union in 2004 (Praakli 2014). According to recent data, 50,318 Estonian speakers constitute the second largest immigrant community in Finland, according to the Finnish Statistical Agency’s database (StatFin Database 2022). However, the participation in home language classes of Estonian children is lower when compared to the activity of participation of children of other large minority origins—Russian, Arabic and Somali speakers. Thus, Estonian-speaking children participating in HL classes are in the fourth place (Teachers’ Labour Union OAJ 2019; Finnish National Agency for Education 2023).

This circumstance justifies the question of Estonian-speaking parents’ awareness of the options of home language teaching and their motivations to send or not to send their children to Estonian classes. The current article presents preliminary research on the topic. We pose the following research questions:

- Q1: What are language beliefs among Estonian caregivers concerning bilingualism and home language proficiency?Q2: What are the actual language management measures as far as the enrolment of the children to free Estonian home language instruction classes (provided by Finnish municipalities) is concerned?

In the present article, the term ‘home language’ is preferred to the often used term ‘heritage language’. Therefore, we refer to ‘home language teaching’ and ‘home language maintenance’ and not ‘heritage language teaching’ and ‘heritage language maintenance’. According to Skutnabb-Kangas and McCarty (2008), terms used to describe the field of multilingual studies are almost never neutral and always cause a discussion (quoted from Eisenchlas and Schalley 2020, p. 17). The term ‘heritage language’ originates from the education literature and policies in the USA and Canada in the 1990s and was introduced to describe ‘non-mainstream languages’ (Wiley 2014).

‘Heritage language’ referred to language speakers whose ancestors lived on the territories before the establishment of the United States, as well as those who migrated to the USA later (Valdés 2001; Wiley 2014 in Eisenchlas and Schalley 2020, p. 25). Gradually, the meaning of the term was expanded, and it may be used as a synonym for ‘minority language’ or ‘non-societal language’. The term ‘heritage language’ is challenged by some scholars (see overview in Verschik 2014). For example, Cummins (2005) states that the term actually includes all languages, since mainstream language speakers also have a heritage. Definitions of ‘heritage language’ vary: some scholars emphasize limited input and lesser competence than in the mainstream language (Valdés 2001; Polinsky 2008), while others refer to specific sociocultural factors, such as migration, identity, and language attitudes, rather than purely linguistic factors (Fishman 2001; He 2010). As Eisenchlas and Schalley (2020, p. 27) rightfully note, the term has a connotation of orientation toward the past. In this respect, Estonians in Finland are a relatively new community (1st generation) who, due to geographical proximity, can easily maintain connections with Estonia and secure a sufficient input in Estonian; some Estonians balance between living in both countries, and so on. This is different from a prototypical situation of immigrant/indigenous minorities described in the literature.

The terms ‘mother tongue’ and ‘first language’ (L1) may be problematic as well because the language first acquired is not necessarily the language one is most competent in or associates oneself with. Affiliation and competence may change during the life span. In our case, however, it is clear that parents have acquired Estonian as L1 and demonstrate a strong emotional connection with the language. At the same time, it is their home language (one’s mother tongue is not necessarily a home language: imagine a couple who speaks the dominant language with all family members, yet one partner has a different L1 that is not used in family communication).

In the present case, the caregivers’ L1 Estonian is their home language. Thus, we believe that the term ‘home language’ is more neutral, as it refers to the language spoken in the home environment and in the present, whereas ‘heritage language’ refers more to the past. When speaking about linguistic proficiency, ‘home language’ includes a wide scale of language skills ranging from limited basic knowledge to native-like proficiency in the language (Eisenchlas and Schalley 2020). In this particular study, we use ‘home language’ and ‘mother tongue’ as synonymous terms.

The article is organized as follows. First, a theoretical overview of FLP studies is presented. The FLP theoretical overview concentrates on Spolsky’s (2012) model concerning three domains: language beliefs, language management, and actual language practices of families. Socioeconomic factors influencing FLPs and the special characteristics of the sociolinguistic situation of the Estonian diaspora community in Finland are also taken into consideration. An overview of the theoretical background is followed by data, methodology, and the findings based on the interview and family conversation data. To follow up, the discussion of the findings and conclusions are provided.

2. The FLP Theoretical Framework

The field of FLP emerged in the early 2000s after the realization that language policy may be conceptualized in a broader sense and not only as something designed and implemented by institutions. Communities and individuals make decisions concerning a particular language or languages; such decisions may be influenced by top–down institutional language policies to a smaller or larger extent or not at all; these may be general decisions (“we speak language X at home”) or rather particular ones that arise from an immediate communicational situation (“oh, she understands language Y, so I can use Y language words”). Earlier studies, such as King and Fogle (2006), King et al. (2008), Okita (2002), and Schwartz (2010), conceptualized families as a domain where language policies are designed and implemented on a micro level.

The model of language policy suggested by Spolsky (2004) has been a standard point of reference in FLP research. According to the model, language policy in general and FLP in particular consists of three components: language beliefs (language ideologies), language management, and language practices. Language beliefs, or ideologies, are ideas about language as such or particular languages, language use, who should speak what language, and so on (for instance, “monolingualism is the best”, “my children should know my language”, “one should speak only proper Estonian and not mix in words from other languages”). Language management is a broad concept that includes all kinds of measures taken in accordance with language beliefs in order to shape language practices. It may include the creation of an appropriate environment for home language usage, enrollment of children in home language classes, and finding playmates from families of the same ethnolinguistic profile. Parents may employ various strategies to manage their children’s language use, for example, rephrasing, suggesting equivalents in home language, etc., especially if they follow the so-called OPOL principle (one parent, one language), see more in (Lanza 1997) and Schwartz (2020, p. 198). According to Curdt-Christiansen (2018, p. 2), language practices are de-facto language use.

In real life, there may be discrepancies between beliefs, management, and practices (for instance, Verschik and Argus 2023). For instance, parents may hold a view that only “pure” languages should be used but, at the same time, switch between languages and not notice it. Or there may be an understanding in the family that some particular measures are necessary, such as creating more input in a lesser-used language, but this may be a difficult task due to various reasons (economic resources, geographical distance, place of residence, size of the community; the roles of some of these factors are discussed in Doyle 2018).

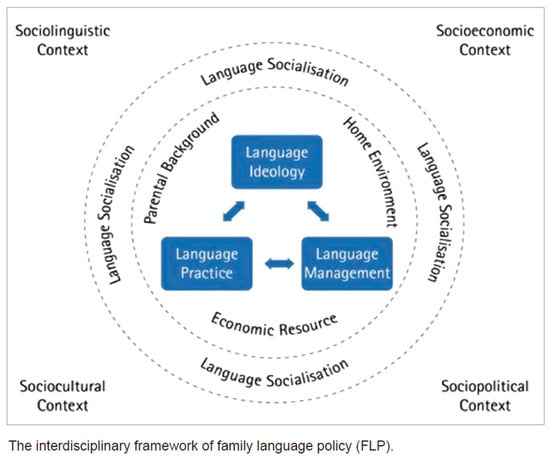

Based on this, it has been suggested that the FLP model as developed by Spolsky (2004) has to be considered in a broader context of sociolinguistic, socioeconomic, sociocultural, and sociopolitical factors. More immediate factors such as the parents’ background, home environment, socioeconomic status, and patterns of language socialization contribute to the formulation and shaping of FLP. These ideas were introduced by Curdt-Christiansen (2018) and have been widely discussed since then (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

FLP framework according to Curdt-Christiansen (2018, p. 423).

In the present study, we concentrate on the language beliefs and language management of Estonian parents in Finland. Language practices remain outside the scope of this research, as we do not have access to actual language use, nor is it relevant for the current study, as we are interested in the attitudes towards Estonian HL education and measures parents take (or do not take) as far as such classes are concerned. In order to analyze language beliefs and management, we need to look at a wider context, such as the sociolinguistic situation of Estonians in Finland in general, and the more specific context of each family. Thus, the general sociolinguistic situation of Estonian speakers in Finland is presented below; other contexts (i.e., sociocultural, sociopolitical, and socioeconomic), as outlined in Figure 1, are dealt with in the discussion section.

2.1. Sociolinguistic Situation of the Estonian Diaspora in Finland

Worldwide, the Estonian diaspora community reaches 150,000 to 200,000 people, which makes it about 15% of all the population of Estonia (Kaldur et al. 2022). The Estonian-speaking diaspora in Finland is a relatively new language community consisting of individuals rather young of age, having developed mainly as a result of intense immigration after the enlargement of the EU in 2004 (Praakli 2014). At present, Estonian speakers are the second largest (50,318) immigrant community in Finland after Russians, according to the Finnish Statistical Agency’s database (StatFin Database 2022). Most members of the Estonian diaspora in Finland are described as multilingual and they identify themselves as native speakers of Estonian, which they speak with a high level of proficiency (Praakli 2014).

Kaldur et al. (2022) researched Estonian-speaking families in the capital area of Finland and noted the lack of awareness of the possible level of language competence in their children’s mother tongue. Caregivers might expect their children’s mother tongue level to be of high proficiency; however, the only activity relating to mastering the language at home was nothing but oral speaking and communicating with relatives, which does not provide adequate input for achieving a high level of academic skills such as writing and reading. In terms of school subject teaching and caregivers’ attitudes, these skills are often divided and not combined into a general literacy term.

According to the same research (Kaldur et al. 2022), the geographically close position of the two countries influences Estonian diaspora families’ language beliefs that good access to traveling and meeting relatives is sufficient for achieving good command in children’s mother tongue. Due to that attitude, they tend to believe additional academic activities for mastering children’s language skills are inessential. Clearly, caregivers’ tendencies to overestimate the significance of oral speaking and underestimate the fact that high command of the Estonian language by children living in Finland is achieved both by family input and academic input from the education they receive in their mother tongue.

2.2. Possibilities of Maintaining the Estonian Language in the Finnish Education System

Home language (HL) is a term broadly recognized worldwide; it describes the language spoken by a minority population of the country. However, in Finland, among educational authorities and in many official documents, another term is used more commonly: a person’s/student’s/child’s own mother tongue. The same term is used to describe home language teaching as a subject in the Finnish schooling system. It is believed that referring to the mother tongue improves the position of these languages, raising them to the same line together with other official mother tongues of schools (Swedish, Finnish).

Instruction of HL started in Finland in 1970 and was applied to refugee children from Chile (Ikonen 2007). In the Finnish National Agency for Education (2014), it is stated that it is the responsibility of schools to support and develop children’s multilingual and multicultural identities. HL classes are not an official subject in the national core curriculum for basic education but only fulfill the role of a “supportive subject of a national core curriculum” (Airto and Aksinovits 2021) and they aim to provide support for general academic studies. The decision whether to enroll their children in HL classes is made by caregivers. Since the classes are not compulsory and often organized outside the general study plan of students, it is quite common for some families to withdraw their children from HL teaching. Due to the lower position of the class in comparison to other school subjects, children are not provided with a transfer from one school to another and it is seen as the responsibility of the caregivers to transfer their children to HL classes, also in situations when the class is scheduled in the middle of the working day. HL groups tend to be highly heterogeneous—students vary in ages and class levels, level of command of the language, motivation to learn, and level of support needed to proceed in academic learning.

Estonian children residing in Finland have some opportunities to maintain their home language; however, access to these opportunities is restricted by the location of the family and availability of language learning-related activities within different municipalities. Some Finnish municipalities provide free facultative home language classes two hours once a week (oman äidinkielen opetus Fin. ‘their mother tongue instruction’).

In addition to home language classes provided by municipalities, in the capital region of Finland, there are also available extra-curricular possibilities for children directed at maintaining Estonian (Koreinik and Praakli 2017). There is also an online option, available in Finland or any other palace, called Worldwide School (Est. Üleilmakool), which offers different courses on Estonian language, culture, history and geography (Kirber 2020) At the moment 350 children from 34 different countries study in Üleilmakool. Some families choose for their children Latokartanon school situated in the capital region with a bilingual Finnish-Estonian curriculum; however, the school has faced declining interest for maintenance of Estonian (Koreinik and Praakli 2017).

There is limited research in the field of FLP concerning home language classes among Estonian diaspora families in Finland. The association of intercultural families, Familia (2022), carried out research on demotivating factors in the decision-making process concerning enrollment of children in HL teaching. Some Estonian families participated in the survey, but researching their beliefs and linguistic behavior was not the exclusive interest of the particular research. According to Familia’s report, the most frequent reasons for not participating in HL teaching are logistical problems: no HL teaching is provided in the home municipality children, the quality of municipal HL classes is low and/or the teacher’s qualification is low/inadequate, lack of HL teachers for certain languages, insufficient information about HL teaching provided in the municipality, highly heterogeneous HL groups consisting of children of different ages and language abilities, and late classes being challenging for children.

3. Data and Methodology

The information about the research was placed on Facebook groups for Estonians residing in Finland. Estonian-speaking caregivers were invited to participate in the research voluntarily. The caregivers who expressed the wish to participate in the study themselves contacted the researchers. In order to collect and map the caregivers’ language-related beliefs, attitudes, and actual language management efforts, eight semi-structured interviews were conducted. Each interview lasted approximately an hour; altogether 8 h of speech was recorded and transliterated.

Ten people responded to the invitation, among whom one wanted to express appreciation for carrying out research on this essential topic. One of the potential participants withdrew their agreement to participate in the research after it was announced that the interviews were recorded.

All of the interviews were held in the Estonian language and transcribed, then content analysis was conducted, based on themes related to internal and external factors influencing management of HL education in the families. This methodology is common for FLP research.

Thus, eight caregivers participated in the research altogether. The participants were aged from 34 to 50. From each family, only one caregiver participated, representing the whole family’s language-related attitudes, beliefs, and language management efforts concerning their children’s participation in Estonian home language classes provided by the municipality.

Almost all participant families but one used Estonian at home. One family was bilingual with a second home language (father’s language) different from Estonian or Finnish. In this family, English was also sometimes used as lingua franca for communication.

Estonian was also the mother tongue for all participants and their children, according to the caregivers’ self-reported answers. There were some cases of another heritage language or ancestral background among parents (Russian, Ingrian Finnish); still, all participants stated that their mother tongue was Estonian, since it is the language they were brought up in and spoken in their childhood.

All of the participants were educated and had a vocational education or higher education. All of the respondents were employed or had a work record and experience of working in Finland. Thus, they had confident socioeconomic positions in Finnish society.

Detailed information about the participants is presented in Table 1 provided below.

Table 1.

Information about the participants.

The focus and the interaction during the interview concentrated on Spolsky’s three-domain FLP model and considered two main FLP domains out of three: language beliefs and language management. The third domain (actual language practices) stayed outside the frame of the interview and was not the point of interest of the present research.

From an ethical perspective, participation in the research was totally voluntary and anonymous, no personal data were included in the article, and the recordings and transcripts are not available to the public and are in the possession of the researchers. No under-aged participants were included in the research, and all answers were the caregivers’ self-reported answers.

4. Findings

The findings are organized following the order and the logic of the research questions. The section is structured as follows: first, everything concerning language beliefs and ideology (Q1), followed by language management measures taken by Estonian diaspora families (Q2).

4.1. Language Beliefs among Estonian Caregivers concerning Bilingualism and Home Language Proficiency (Q1)

As stated above, in almost all families but one, both L1 and the home language was Estonian. In all of the interviews, a strong belief was expressed that the caregivers themselves and their children identify themselves as Estonians and their mother tongue as well as their home language is Estonian.

CG1: Meil on oma eesti mull siin. Meil on kodus Eesti lipud ja Eesti sümboolika. Hoiame au sees. Juured on ikkagi väga tähtsad. Ei näe, et eluks ajaks jääme Soome. Kunagi äkki tuleb ilus aeg ja saame tagasi Eesti minna.

‘We have our own Estonian bubble here. We have Estonian flags and symbols at home. We honor it. The roots are indeed very important. I do not think that we might stay for our whole life in Finland. Maybe beautiful times will come and we can go back to Estonia’.

CG4: Oleme Eestist pärit, räägime eesti keelt ja eesti keel on meie emakeel. Eestis on meie juured ja me olemegi eestlased.

‘We originally come from Estonia, we speak Estonian and Estonian is our mother tongue. We have our roots in Estonia and we are Estonians’.

Additionally, the value of Estonian language proficiency was considered as an inter-generational link, aiming to prevent generation gap between grandparents and grandchildren living in two different countries.

CG4: Eesti keelt läheb kindlasti tulevikus vaja. Meil on sugulased seal, vanaemad—vanaisad. Meie oleme väga sellest kinni, et peab teadma meie keelt—oma emakeelt, vanemate keelt. Kui oled sealt riigist pärit, siis oleks ilus osata seda keelt. Kunagi ei tea, kas äkki lähed tagasi.

‘The Estonian language will definitely be necessary in the future. We have our relatives there, grandmas, grandpas. We stick close to the fact that it is essential to know our language—our mother tongue, the parents’ language. If you come from that land, it is good to have language skills. You never know, maybe you’ll go back someday’.

CG5: Minu laste jaoks see on vanaema juures käimise keel. Mis keeles nad siis räägiks? Ma isegi ei kujutaks ette, et nad seda ei oskaks. On oluline, et see side säiliks.

‘For my children, it is the language for visiting grandma. In which language would they communicate otherwise? I cannot even imagine that they [children] wouldn’t be able to speak it. It is extremely important that the connection would last’.

Interestingly, maintenance of Estonian as a strong basis for cultural identity was also believed to be an opportunity for future additional education and career opportunities. In several interviews, the idea was mentioned that children might go to study in Estonia later in their lives and they would need to have good academic skills in their L1 to enter a university there.

CG1: Kunagi ei tea, äkki (laps) läheb Eesti elama.

‘You never know, maybe [the child] would move to Estonia’.

CG4: Praegu on meil lihtne, kuna laps tahab Tartu ülikooli minna. Väiksena ütles, et tema läheb kindlasti Tartu ülikooli, kuna tahab arstiks saada … Uksed aga oleksid rohkem lahti (kui õpiks eesti keelt) ja oleks rohkem võimalusi tulevikus. Eestis oleks keelega kergem sisse saada.

‘Right now it is easy for us because the child wants to study in the university of Tartu [a university in Estonia]. When the child was small, he used to say that he would definitely go to the university of Tartu to become a doctor. Doors would be more open (if the child learns Estonian) and there would be more opportunities in the future. It would be much easier to enroll into a university in Estonia if one speaks the language’.

While emphasizing the importance of Estonian for their and their children’s identities, all caregivers also valued their children’s multilingualism and the ability to use various languages and switch between languages if needed as a positive skill. It was not asked explicitly about the purism of Estonian usage at home; however, mother tongue-related linguistic purism was often a general tendency in families of Estonian origin. The caregivers volunteered to talk about the importance of “pure” Estonian. Thus, in their view, multilingualism was positive but languages should be separated. For all of the families, except one bilingual family, it was important to keep Estonian as a home language and other languages (Finnish, English) for outside home use.

CG4: Segasõnu laps kasutab väga harva. Kui ta soome keeles ütleb, siis me ütleme, et ei saa aru, ütle palun selle eesti keeles. Kui ta ei tea, kuidas see eesti keeles on, siis ta küsib ise, mis see eesti keeles on. Ta väga hästi vahetab ära, kiiresti soome keelest eesti keelde. … Oleme talle rääkinud, et see on rikkus, et oskad rääkida erinevaid keeli

‘The child uses mixed words really seldom. When the child says something in Finnish, then we tell him that we do not understand, please say it in Estonian. If he doesn’t know how to say it in Estonian, then he asks himself how to express it in Estonian. … We have told him that it is a treasure to be able to speak different languages’.

CG6: Siis kui korteri uks läheb kinni, siis on ikkagi eesti keel.

‘When the door is shut, then it is the Estonian language’.

Nevertheless, limited use of words and phrases in other languages at home was evaluated as a normal tendency for youth and children. Children and parents themselves used words and phrases in other languages to optimize the communication process, in addition, children may engage in multilingual humor and emphasize their bilingual linguistic skills.

CG1: Noorem laps kasutab vahepeal sõnu reppu, läksyt. See on kuidagi loomulikum.

‘Our younger child sometimes uses the words reppu ‘schoolbag’, läksyt ‘homework’ [in Finnish] It is somehow more natural’.

The tendency of purism was also noticed in the situation when children are able to notice “a wrong language” and correct themselves. Thus, self-correction was evaluated as a positive trait, which was somewhat contradictory to the previous acknowledgement of bilingual skills and code-switching being evaluated as positive (for various parental strategies, see Schwartz in Eisenchlas and Schalley 2020, pp. 194–217). On the one hand, the caregivers believed that languages should be separated and only Estonian should be used at home; on the other hand, they spoke in a positive way about children’s bilingual creativity and believed that insertion of some Finnish words referring to school life is natural.

CG2: Laps tekitab uusi sõnu nt vieraat/võõrad. Kodus kasutab ainult eesti keelt, automaatselt parandab: ütleb “vabandust” ja parandab soomekeelse sõna eestikeelseks.

‘The child creates new words, for example vieraat/võõrad [cognates, Estonian võõrad strangers’ and Finnish vieraat ‘guests’. At home, the child uses Estonian only, corrects herself if needed: says “sorry” and corrects the word in Finnish into Estonian’.

Acquiring academic skills such as reading and writing by children was evaluated as important. However, often it was seen as a whole system of language proficiency together with speaking. Speaking and being able to communicate with relatives and grandparents back in Estonia was still mentioned as one of the most important language skills. Reading and writing were evaluated as important too, but it was also stated that maintaining these skills required extra effort from families even if the children participated in HL classes.

CG3: Lugemine on ajaliselt muutunud. Raamatuid on meil väga palju. Olen alati ostnud, ja kingitud palju. Väiksena oli palju lugemist ja ette lugemist. Aga kui lapsed suuremaks said, siis on raske neid raamatu juurde saada. Ja küsimus ei ole eesti keeles, aga üldse selles, et raamatute lugemine on “nõme ja igav”.

‘Reading has changed in time. We have a lot of books [at home]. I have always bought them and a lot of books were presented as gifts. There was a lot of reading and reading out loud when the children were small. But as the children grew up, it became harder to get them to read [books]. And the question is not about the Estonian language, but about the attitude that reading on the whole is “dumb and boring”’.

The caregivers’ beliefs concerning free municipal HL classes were also analyzed and the findings are presented further. Many caregivers believed that Estonian culture is strongly connected to the Estonian language and the identity of being Estonian, but teaching about Estonian culture and history was not mentioned as a popular topic in the HL curriculum. In their opinion, HL classes should rather be fun and entertaining for children and should include topics interesting for children and for teenagers. According to the participants, there are many things that can be learned through play. Learning about Estonian folk games/dances using computer games and digital devices was also mentioned as suitable content for HL classes.

CG1: Kõige paremini saab saab keelt suhtlemise kohta. … Keel käib kaasas kultuuriga—traditsioonid ja kombed. Oma emakeele tunnis võiks olla tegevus noortepärasem, mitte kuiv teooria. Uudise kokkuvõtte kirjutamine.

‘The best way to acquire a language is through communication. … Language is connected to the culture: traditions and customs. In an HL class, the activities could be more youthful, not all dry theory. Writing a summary on some news article’.

CG2: Tänapäeval lapsed tahavad arvutis olla. Lastele võib olla huvitav mingisugusest kuulsusest klatši lugeda. Artiklid, ristsõnad, asjad, arvutimängud. Kui teha materjalid virtuaalseks ja huvitavaks, mänguliseks, siis äkki pakub huvi.

‘Nowadays children want to be on a computer. It could be interesting for children to read some gossip about celebrities. Articles, crosswords, things, computer games. If digital teaching materials are involved and the teaching is attractive, gamified, maybe it might motivate [the children]’.

In some cases, the caregivers underestimated the importance of a two-hour HL class and did not believe it to be a game changer in the process of children’s language development since the amount of the classes was so insignificant. HL classes were evaluated rather as one additional activity for maintaining the language among many other possible activities. The system behind teaching for two hours a week strengthened by revision, reading, or writing homework at home was not seen as a framework for supporting children’s academic skills in Estonian.

CG1: Mingi hetk tuli teave, et see eesti keele õpe oli seal koolis ära lõppenud ja kuhugi mujale teise linnaossa kolinud (…) Ja siis meie emakeele eesti keele tunnid olid ära jäänud. Me ei hakanud enam pingutama. Ei ole mõtet rabeleda, sellest on kasu väike.

‘At a certain point, we received information that HL Estonian classes were terminated in that school and moved to some other place in the city. (...) And then our HL classes were left behind. We stopped trying. There is no point in struggling, the benefit is too little’.

In addition to the HL classes’ curriculum, the teacher’s role in motivating children to participate was discussed. The participants were not asked explicitly to evaluate the role of teachers or the lack of motivation among children to participate in HL classes. Nevertheless, quite often, the teachers’ pedagogical qualification, skills of planning classes, choosing teaching materials for the class, and personal characteristics were mentioned during the interview.

CG1 Võib olla lapsed saavad rohkem mõjutada tunni kulgu, kui õpetaja on selline avatum ja sõbralikum.

‘Maybe children can influence the course of a class more if a teacher is more friendly and open-minded’.

CG2: Õpetaja isiksus mõjutab. Kui äkki õpetaja mõjub sellise kohustusena ja õpetab kuivalt. Või ta tuleb ise niimoodi, et lapsed on põnevil ja on huvitatud.

‘The teacher’s personality makes an impact. If maybe the teacher acts as an obligation and teaches in a dull way. Or maybe the teacher enters the class in a way that makes the children also excited and interested’.

Some caregivers brought to light the importance of taking children’s basic needs into consideration. HL classes take place in the second part of the day, when children are already tired and hungry. The availability of snacks for children within the school building during late classes was mentioned as one of the motivating factors for participating in the HL teaching process.

CG1: Tahtsime panna eesti keele tundidesse, aga kohe esimesest klassist alates tunnid olid alates kella 17, tunnid olid teises koolis. Pidime organiseerima nii, et laps sinna teise kooli saada. Ilmsekseet peale pika päeva kella 5-ks on laps väsinud ja enam ei jaksa.

‘We wanted to enroll [the child] into Estonian HL class, but right from the first grade, the classes started at 5:00 p.m., the classes were in another school. We had to organize a lift for the child to get her to another school. Obviously, after a long day, by 5:00 p.m. the child is tired and can’t take it anymore’.

CG2: Lapsi motiveeriks peale tunde jääma, kui nad saaks sealt mingeid snäkke.

‘It would be more motivating for children to stay after the classes if they get some snacks there [at school]’.

Since not all participants had experience with HL classes, it was instructive to learn how they explained the beliefs of other Estonian families regarding not participating in these free municipal classes. For that reason, the caregivers were asked explicitly why children from other Estonian families they know do not participate in HL classes. The participants provided the following arguments:

- Logistical and timing problems: classes take place in the evening and/or in a distant school.

- The content of the classes is not motivating enough for children to participate.

- The teacher might be a kind of “old-school teacher”, not flexible and child-friendly enough.

- Highly heterogeneous groups where children vary in age, language skills, and motivation.

- Families might have decided not to return to Estonia anymore and start building their life and the life of their children in Finland. There was even an idea that these other parents “might be disappointed in Estonia as the state and do not want to return there anymore”.

- Language shift in domestic communication: almost all caregivers expressed concern about other families that start using Finnish or bilingual Finnish-Estonian mode for communicating with their children, as a result, they do not value Estonian enough to send their children to HL classes. Caregivers participating in the research expressed their concern about these families abandoning Estonian as the language of their roots and country of origin. However, we do not have evidence to support this claim that families whose children do not attend HL classes shift to Finnish as HL.

To sum up, Estonian diaspora families tended to have a strong mother tongue-related identity and value the acquisition of and proficiency in Estonian as extremely important. Almost all parents believed that children might need Estonian language skills in the future for education and career. Various beliefs regarding HL classes were also noted in this section.

4.2. Knowledge of Scholars Fails

In this section, language management, as reported by the families, is examined and analyzed. Eight different families of Estonian background were represented in the present semi-structured interview. Data concerning this part of the research is represented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Attendance of free municipal HL classes and reasons for not participating in them.

As apparent from the information provided by the parents, most children did not participate in free municipal HL classes for various reasons. In the eight families that participated in the research, there was a total number of 19 children. Three of the children were of preschool age and could not be considered in the present study. Two of the participants’ children were already young adults, yet with experience of learning in a Finnish educational system. Among all of these children, only five had some experience with attending HL classes, four children were enrolled into bilingual Estonian-Finnish school, and four were studying in English at an international school. Below, the reasons for not participating at all or stopping participating in HL classes are listed:

- (a)

- Logistical problems and timing problems: the classes are organized late in the evening and/or in a distant school.

- (b)

- Child-oriented reasons: the child is tired late in the evening, the child did not like the classes and found them boring, the child has some special needs and extra classes late in the evening are burdensome for him/her.

- (c)

- An insufficient support network for migrant-background families: caregivers have to take care of everything themselves, managing work, house and family. Lack of grandparents and relatives who would partly share the management of the children was evaluated as an important factor influencing priorities in decision making concerning children’s extra-curricular activities. In addition, the same factor, according to the caregivers’ responses, influenced managing children’s reading activities at home: reading for pleasure or reading aloud books to children.

CG1: Meil Soomes tugivõrgustik on nii hõre—vanaemasid, vanaisasid, kes võtaksid osa asjadest enda peale. Tugiisikuid on vähe. Rügame tööd.

‘In Finland, our support network is so limited, [we don’t have] grandmas and grandpas who would give a hand in some things. The number of support persons is small. We keep our shoulders to the wheel’.

- (d)

- Highly heterogeneous groups and, as a result, unsystematic teaching methodology and teaching materials that do not take into consideration the level of the child’s language proficiency.

CG5: Kui grupis on kõik lapsed erineva vanusega, siis on raske igat last õpetada vanusele vastavalt ja veel teha seda huvitavalt. … Raske hinnata õpetajate metoodilist osamist. Vahepeal tundub, et ei ole äkki nii läbi mõeldud, mis laadi näiteks kodused ülesanded metoodiliselt hakkavad olema.

‘If all the children in the group vary in age, it is difficult to teach each child according to their age and to do it in a motivating way. … It is difficult to evaluate the methodological skills of teachers. Sometimes it seems that maybe it was not quite planned how the homework assignments would work from the point of view of teaching methods’.

CG8: Eesti keele tunnid olid pettumus talle. Minul oli ka suur hämming. Nad värvisid seal. Ja need lehed, mida ta koju tõi... Mõned olid väga lihtsad, nagu lasteaia ülesanded. Ja teised olid juba rasked.

‘Estonian HL classes were a disappointment for the child. I was also very confused. They painted there. And the worksheets the child brought home… Some of them were very simple, like kindergarten assignments. And others were already difficult’.

- (e)

- Deficient home–school interaction: insufficient interaction with teachers and educational authorities on the matter of teaching curriculum, teaching aims, teaching materials, feedback and evaluation, and benefits of learning HL at school on an academic level.

CG7: Ja siis ikka see, et ega täpselt ei teata mida seal tehakse. Et umbes kui ma ise ei tea mis seal toimub, siis miks ma peaksin oma last sinna sundima. Tutvustus puudub.

‘And then the fact that it is actually not exactly known what is being done there [in class]. That if I myself don’t know what’s going on there, why should I force my child there. This kind of information is absent’.

Two caregivers mentioned that they did not feel that the authorities were interested in improving HL-related language awareness of families and, additionally, Estonian families felt excluded from general language minority communities, since neither information nor translation was ever provided in Estonian, yet it was provided in other minority/immigrant languages.

CG7: Meil kooli kaudu ei ole mitte mingit infot tulnud. Kõikides teistes keeltes (somaali, arabia, rootsi keeles, inglise keeles) tuleb infot Wilmasse, aga mitte mingil juhul eesti ja vene keeles

‘We haven’t received any information from the school. Information is sent to Wilma in all other languages (Somali, Arabic, Swedish, English), but not in Estonian or Russian’

CG8: Ei jää tunnet, et see tund on võrdväärne teiste kooli tundidega. Seda serveeritakse nii—juba kirjastiil on selline, et “Äkki teid huvitab”. Aga see peaks rõhutama just oma kultuuri ja oma keele oskust ja seda, kui oluline on see lapse arengus ja identiteedis.

‘There is no feeling that this class has an equal status if compared to other classes at school. It is served as follows: the writing style itself goes like this: “Perhaps you are interested”. But it should emphasize the knowledge of one’s culture and language and how important it is for the child’s development and identity’.

In order to discover more about actual linguistic behavior of Estonian diaspora families, the caregivers were asked about measures for supporting children’s mother tongue at home. The questions mostly concerned reading and extracurricular activities. Many caregivers mentioned watching television in Estonian and listening to audiobooks as important activities for maintaining the children’s proficiency in Estonian. Supporting reading in Estonian at home was mostly evaluated as highly important and almost all families tended to contribute to providing books in Estonian for children, whether borrowing them from a library or buying from bookstores in Estonia.

CG1: Kui laps oli väike, siis oli palju raamatuid ja oli lemmikraamatuid. Laps ei saanud nendest kunagi küllalt. Aga mida vanemaks sai, seda vähem huvi jäi. Kodus ei ole seda lugemisharjumust ei ole jatkunud. Nutiseadmed on lastele nii olulised nüüd, et raamatu lugemine ei tundu olulisena lastele. Inglise keelt oli tulnud nendel ka rohkem. Raamatute lugemiseks peab rohkem motiveerima. Endal töö ja pere asjade kõrval alati ei ole selleks aega.

‘When the child was small, there were many books and the child had favorite books. The child could never get enough of them. But the older the child got, the less interest remained. This reading habit has not been established at home. Electronic gadgets are so important to kids nowadays, that reading a book doesn’t seem important to kids. They received more English [input]. It is essential to motivate [the children] more to read books. We don’t always have time for this amidst work and family matters’.

As far as language management was concerned, all caregivers tried to support and develop their children’s mother tongue skills by providing various tools and activities, such as communicating in Estonian, buying and reading books, providing an opportunity to watch television in Estonian, and participating in extracurricular activities such as language and culture clubs and events. However, it seemed that HL classes were underestimated as an important academic activity and rated as another extracurricular activity. In addition, children were also involved in family language policy since parents took their opinions and the feedback perceived from the children into consideration in language behavior-related decision making.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

The answer to Q1 (What language-related beliefs and ideologies do caregivers have?) is as follows. The caregivers of Estonian origin have a strong belief in belonging to the Estonian community and, according to their own evaluation, have a strong sense of Estonian identity and transfer it to their children at home. They highly value their mother tongue and think that it is important for their children to learn Estonian. In many cases, a possible education or career path for their children is seen as a beneficial opportunity that opens many doors and is secured by proficiency in Estonian.

As for Q2 (What are the actual language management measures as far as the enrolment of the children to free Estonian home language instruction classes is concerned?), the interview data revealed some discrepancy between the caregivers’ declared linguistic beliefs and actual linguistic behavior. Free municipal home language classes are not always seen as an option to maintain the Estonian language among children. Instead, these are mostly listed as one possible extracurricular activity rather than an essential and effective academic activity. A positive impact of systematic HL instruction on children’s multilingual identity, school academic achievement in both L1 and L2, and general academic skills and cultural competencies is stated by many scholars (Cummins 2000; Ganuza and Hedman 2019; Agridag and Vanlaar 2016; Seals and Peyton 2016; Yli-Jokipii et al. 2022). However, it seems that the common knowledge of scholars fails to meet the actual HL management realities of families in everyday life.

The sociopolitical context is that of two friendly states. Families choose a bilingual Estonian-Finnish Latakartanon school situated in Helsinki if their geographical location enables it. Some rely on the role of family and home activities, such as reading, watching programs and movies in Estonian, and speaking, to maintain children’s mother tongue. The caregivers also admitted that the lack of a supportive network of relatives and grandparents acts as a barrier to the development of language proficiency in full scale. Thus, the findings differ from the findings by Kaldur et al. (2022), according to which Estonian caregivers tend to overestimate the significance of speaking and underestimate additional academic activities for mastering children’s language skills. The results of the present study, in contrast, show that maintaining children’s academic skills in Estonian and attending HL classes as one of the options to manage language skills are valued among caregivers. Caregivers tend to believe that those “other parents” who do not send their children to such classes are probably shifting to Finnish in home communication. However, caregivers’ language beliefs and actual linguistic behavior do not necessarily match: caregivers tend to believe that maintaining academic skills are important and know well the possible tools and activities to maintain their children’s linguistic proficiency, but they struggle to implement their knowledge about language maintenance.

The geographically close position of Estonia and Finland was often mentioned as one of the important factors influencing use of Estonian and the linguistic proficiency of the Estonian diaspora community in Finland. Kaldur et al. (2022) partly explained overestimation of oral skills among Estonians in Finland by the geographically close position of the two countries and good access to traveling, meeting relatives, and being exposed to the language. According to our findings, children of Estonian diaspora families are exposed to the language most of the time while living in Finland and communicating with members of the Estonian community there. Thus, they master their linguistic skills to be used as a tool for communication and preventing inter-generational gap while traveling to Estonia to meet relatives.

In relation to HL teaching, parents tend to delegate responsibility for motivating children to participate in HL classes to schools and teachers. However, the lower position of HL classes in comparison to other school subjects can definitely work as a demotivator. Lack of suitable structured teaching materials, large and highly heterogeneous groups, problematic timing, and logistics were mentioned as demotivators also in the research carried out by the association of intercultural families, Familia (2022). Interestingly, insufficient dialog between home and school and low motivation of authorities were not mentioned among the reasons for not participating in HL classes in Familia’s research, but they were brought out in the present research results.

On a more general note, we discuss the results in the framework by Curdt-Christiansen (2018, see above). As far as parental background, home environment, and economic resources are concerned, all parents had stable incomes, higher education, and the home environment was safe. Based on the interviews, it was clear that the parents think about their children’s linguistic skills and try to provide reading materials in Estonian and not only rely on oral communication. At least in theory, writing and reading skills are considered to be important.

Language socialization of the caregivers takes place in the context of Estonian ethnic identity being based on Estonian language (i.e., ethnic Estonians speak Estonian as L1 and identify with this language). The parents adhere to this concept and use Estonian at home (the principle “minority language at home”, except for one mixed family).

The sociolinguistic and sociocultural contexts of the study differ from that in many studies where a minority is linguistically distant and comes from a geographically distant location. Estonians are one of the largest ethnolinguistic minorities in Finland, the languages are closely related, and the countries are situated close to each other.

The sociopolitical context is that of two friendly states with a long history of cultural connections and no antagonism. Although in any society there are people who dislike foreigners in general or some ethnolinguistic group in particular, the political climate in Finland does not disfavor Estonians and speakers of Estonian.

The socioeconomic context of the families in question is distinct from that of most Estonian migrants in Finland. While there was work migration from Estonia to Finland in the 1990s–2000s (mostly blue collar workers), they tended to be a rather segregated community (Sinitsyna 2024). Still, many people go back and forth between the two countries. The families in question have white collar occupations and are well integrated into Finnish society. Probably partly because of that they feel secure, they believe that their children might choose to build their life in Estonia in the future and proficiency in Estonian would enable this.

Some limitations of the present study have to be taken into consideration while trying to understand the phenomenon of discrepancy between parents’ beliefs about language and language management (see some case studies like Ghimenton 2015; Verschik and Argus 2023). All of the caregivers who participated in the study were highly motivated in preserving and maintaining their children’s mother tongue. All of them came from more or less equal socioeconomic conditions, were educated, and had a work record and experience of working in Finland. Participation in the study was skewed toward parents who evaluated HL positively and were more likely to act accordingly. In addition, most of the caregivers lacked experience with municipal HL classes for various reasons. This makes it impossible to make generalizations on the whole Estonian diaspora in Finland, especially concerning the reasons for not sending Estonian children to HL classes.

It would be highly desirable to carry out additional research in this field. Many beliefs of the caregivers were connected to their insufficient information about the teaching materials and the absence of suitable HL coursebooks as such, the curriculum and aims of HL classes, as well as the didactics and methodology, which can be the result of faulty or/and incomplete communication on a home school level or inadequate and deficient HL teaching organization by the municipal authorities. Thus, these areas need additional scholar attention.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.A. and A.V.; methodology, A.V.; formal analysis, L.A. and A.V.; investigation, L.A.; resources, LA. and A.V.; writing—original draft preparation, L.A. and A.V.; writing—review and editing, A.V.; supervision, A.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research did not receive any external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving human samples in accordance with the Ethical principles of research with human participants and ethical review in the human sciences in Finland issued by the Finnish National Board on Research Integrity (TENK) in 2019 because the study did not involve intervening in the physical integrity of research participants, did not expose research participants to exceptionally strong stimuli, and does not entail a security risk to the participants or their family members. The study did not involve any children/refugees, the participants were grown up adults only. Information about the study and invitation to participate was placed in social media. Participation in the study was totally voluntary.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. The participants insisted on their names not being shared officially with any parties concerned.

Data Availability Statement

Due to the personal character of the interviews, the data are not available.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Agridag, Orhan, and Gudrun Vanlaar. 2016. Does more exposure to the language of instruction lead to higher academic achievement? A cross-national examination. International Journal of Bilingualism 22: 123–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Airto, Pipsa, and Larissa Aksinovits. 2021. Multilingual Native Language Lesson, a Pilot Project in Tuusula, Finland. Kieliverkosto. Available online: https://www.kieliverkosto.fi/fi/journals/kieli-koulutus-ja-yhteiskunta-lokakuu-2021/multilingual-native-language-lesson-a-pilot-project-in-tuusula-finland (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- Cummins, Jim. 2000. Language, power, and pedagogy: Bilingual children in the crossfire. Bilingual Research Journal 25: 405–12. [Google Scholar]

- Cummins, Jim. 2005. A proposal for action: Strategies for recognizing heritage language competence as a learning resource within the mainstream classroom. Modern Language Journal 89: 585–92. [Google Scholar]

- Curdt-Christiansen, Xiao Lan. 2018. Family language policy. In The Oxford Handbook of Language Policy and Planning. Edited by Tollefson James and Pérez-Milans Miguel. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 420–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, Colm James. 2018. ‘She’s the big dog who knows’–power and the father’s role in minority language transmission in four transnational families in Tallinn. In Keelest ja Kultuurist/On Language and Culture. Philologia Estonica Tallinnensis 3. Edited by Reili Argus and Suliko Liiv. Tallinn: Tallinna Ülikooli Kirjastus, pp. 17–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenchlas, S. A., and A. C. Schalley. 2020. Making sense of “home language” and related concepts. In Handbook of Home Language Maintenance and Development. Handbooks of Applied Linguistics. Berlin and Boston: Walter de Gruyter GmbH, vol. 18. [Google Scholar]

- Familia. 2022. A Research Report on the Participation of Children Coming from International Families in Heritage Language Classes. Available online: https://www.familiary.fi/uploads/7/1/8/2/71825877/oman_aidinkielen_document.pdf (accessed on 18 February 2024).

- Finnish National Agency for Education. 2014. Finnish National Core Curriculum for Basic Education 2014. Available online: https://www.oph.fi/sites/default/files/documents/perusopetuksen_opetussuunnitelman_perusteet_2014.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Finnish National Agency for Education. 2023. Database of Students of a Migrant Origin Participating in Native Language Lessons in Year 2022. Available online: https://www.oph.fi/sites/default/files/documents/Oman%20%C3%A4idinkielen%20opetukseen%20osallistuneet%202022.pdf (accessed on 18 June 2024).

- Fishman, Joshua. 2001. 300-plus years of heritage language education in the United States. In Heritage Languages in America: Preserving a National Resource. Edited by Peyton Joy Kreeft, Ranard Donald A. and McGinnis Scott. McHenry and Washington, DC: Delta Systems and Center for Applied Linguistics, pp. 87–97. [Google Scholar]

- Ganuza, Natalia, and Christina Hedman. 2019. The Impact of Mother Tongue Instruction on the Development of Biliteracy: Evidence from Somali-Swedish Bilinguals. Applied Linguistics 40: 108–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimenton, Anna. 2015. Reading between the code choices: Discrepancies between expressions of language attitudes and usage in a contact situation. International Journal of Bilingualism 19: 115–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Agnes Weiyun. 2010. The heart of heritage: Sociocultural dimensions of heritage language learning. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 30: 66–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikonen, Kristiina. 2007. Oman äidinkielen opetuksen kehityksestä Suomessa. In Oma kieli kullan kallis. Opas oman äidinkielen opetukseen. Edited by Latomaa Sirkku. Helsinki: Finnish National Agency for Education. Available online: https://www.oph.fi/sites/default/files/documents/Oma%20kieli%20kullan%20kallis.pdf (accessed on 21 January 2024).

- Kaldur, Kristjan, Kirill Jurkov, Nastja Pertsjonok, Robert Derevski, Kats Kivistik, Richard-Karl Henahan, Emily Vogel, Keiu Telve, Liisi Reitalu, and Darya Podgoretskaya. 2022. Estonian Communities Abroad: Identity, Attitudes and Expectations Towards Estonia. Available online: https://www.ibs.ee/en/publications/estonian-communitites-abroad-identity-attitudes-and-expectations-towards-estonia/ (accessed on 17 March 2024).

- King, Kendall A., and Lynn Fogle. 2006. Bilingual Parenting as Good Parenting: Parents’ Perspectives on Family Language Policy for Additive Bilingualism. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 9: 695–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, Kendall A., Fogle Lynn, and Logan-Terry Aubrey. 2008. Family Language Policy. Language and Linguistics Compass 2: 907–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirber. 2020. Üleilmakool. Available online: https://yleilmakool.ee (accessed on 15 March 2024).

- Koreinik, Kadri, and Kristiina Praakli. 2017. Emerging language political agency among Estonian native speakers in Finland. In Language Policy Beyond the State. Edited by Maarja Siiner, Kadri Koreinik and Kara Brown. Cham: Springer, pp. 81–98. [Google Scholar]

- Lanza, Elisabeth. 1997. Language contact in bilingual two-year-olds and code-switching: Language encounters of a different kind? International Journal of Bilingualism 1: 135–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okita, Toshie. 2002. Invisible Work: Bilingualism, Language Choice and Childrearing in Intermarried Families. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polinsky, Maria. 2008. Heritage language narratives. In Heritage Language Education. A New Field Emerging. Edited by Donna M. Brinton, Olga Kagan and Susan Bauckus. New York and London: Routledge, pp. 149–64. [Google Scholar]

- Praakli, Kristiina. 2014. On the bilingual language use of Estonian-speakers in Finland. Sociolinguistic Studies 8: 383–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, Mila. 2010. Family Language Policy: Core Issues of an Emerging Field. Applied Linguistics Review 1: 171–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, Mila. 2020. Strategies and practices of home language maintenance. In Handbook of Home Language Maintenance and Development. Edited by Schalley Andrea C. and Eisenchlas Susana A. Berlin/Boston: Walter de Gruyter, pp. 194–217. [Google Scholar]

- Seals, Corinne A., and Joy Kreeft Peyton. 2016. Heritage language education: Valuing the languages, literacies, and cultural competencies of immigrant youth. Current Issues in Language Planning 17: 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinitsyna, Anastasia. 2024. Links between Segregation Processes on the Labour and Housing Markets: Evidence from Finland. Ph.D. thesis, University of Tartu, Tartu, Estonia. [Google Scholar]

- Skutnabb-Kangas, Tove, and Teresa McCarty. 2008. Key concepts in bilingual education: Ideological, historical, epistemological, and empirical foundations. In Encyclopedia of Language and Education: Bilingual Education, 2nd ed. Edited by Jim Cummins and Nancy H. Hornberger. New York: Springer, pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Spolsky, Bernard. 2004. Language Policy Key Topics in Sociolinguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Spolsky, Bernard. 2012. Family language policy—The critical domain. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 33: 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- StatFin Database. 2022. Vieraskieliset Suomen väestössä. Available online: https://www.stat.fi/tup/maahanmuutto/maahanmuuttajat-vaestossa/vieraskieliset.html (accessed on 12 January 2024).

- The Trade Union of Education in Finland (OAJ). 2019. Kotoutumiskompassi. Available online: https://www.oaj.fi/ajankohtaista/julkaisut/2019/kotoutumiskompassi-2019 (accessed on 12 January 2024).

- Valdés, Guadalupe. 2001. Heritage languages students: Profiles and possibilities. In Heritage Languages in America: Preserving a National Resource. Edited by Joy K. Peyton, Donald A. Ranard and Scott McGinnis. Washington: Center for Applied Linguistics and Delta Systems, pp. 37–77. [Google Scholar]

- Verschik, Anna. 2014. Conjunctions in early Yiddish-Lithuanian bilingualism: Heritage language and contact linguistic perspectives. In Language Contacts at the Crossroads of Disciplines. Edited by Heli Paulasto, Lea Meriläinen, Helka Riionheimo and Maria Kok. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 33–58. [Google Scholar]

- Verschik, Anna, and Reili Argus. 2023. When family language policy and early bilingualism research intersect: A case study. Taikomoji Kalbotyra 20: 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiley, Terrence G. 2014. The problem of defining heritage and community languages and their speakers: On the utility and limitations of definitional constructs. In Handbook of Heritage, Community, and Native American Languages in the United States: Research, Policy, and Educational Practice. Edited by Terrence G. Wiley, Joy Kreeft Peyton, Donna Christian, Sarah Catherine K. Moore and Na Liu. New York: Routledge, pp. 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Yli-Jokipii, Maija, Rissanen Inkeri, and Kuusisto Elina. 2022. Oman äidinkielen opettaja osana kouluyhteisöä. Kasvatus 53: 350–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).