Abstract

This study is based on a sample of 30 Sinitic languages spoken in the Hunan Province. Its first objective is to explore the types of dative markers, comparing the form of the dative with allative, passive, benefactive, and differential object markers in these languages. Five patterns are identified: (I) DAT = ALL (II) DAT = GIVE = OM ≠ PASS; (III) DAT = GIVE = OM = PASS; (VI) DAT = GIVE = PASS ≠ OM; (V) DAT = BEN. Then, we reveal three main possible grammaticalization pathways that motivate the five synchronic patterns: (a) Allative > Dative; (b) (TAKE >) GIVE > Dative; (c) Benefactive > Dative. It concerns two distinct developments for the second pathway. Based on the areal distribution of the various types of dative markers, we can observe how the dative markers are developed in Hunan Sinitic languages.

1. Introduction

This paper discusses the dative (recipient) markers in the Sinitic languages spoken in the Hunan Province.

Before embarking on the examination of the dative markers, it is pertinent to offer a brief introduction to the languages spoken in the Hunan Province. Hunan is located in the south-central region of China. According to Bao and Li (1985), the Hunan Sinitic languages can be classified into five broad areas: Xiang varieties spoken in the center of Hunan; Southwestern Mandarin varieties spoken in the west and south; Gan and Hakka varieties spoken in the east; Waxiang spoken in the west; and Tuhua1 spoken in the south (both within the Mandarin-speaking regions). Additionally, there are several non-Sinitic languages spoken in Hunan: Tujia in the northwest; Miao in the west; Dong in the southwest; and Yao in the south. Of these languages, Tujia exhibits SOV word order, while other languages use SVO order. Hunan is classified as a transitional zone for Sinitic languages in Chappell (2015), such that an examination of the Sinitic languages in Hunan can shed light on the refinement of this linguistic area and contribute to a better understanding of the linguistic development within Sinitic languages.

Dative usually refers to a morphological case that prototypically marks the recipient or indirect object in a ditransitive construction (cf. Haspelmath 2016). In this paper, we use dative marker to indicate the element that introduces the recipient argument, as the morpheme to in I gave a pen to Paul in English. Most studies on the Sinitic ditransitive constructions focus on the sentence structures, especially on the relative word order between the recipient and the theme (see Hashimoto 1976; Zhu 1979; Yue-Hashimoto 1993, for example). Chin (2010) firstly identified two types of dative markers in Sinitic languages (i.e., the go-type and the give-type) and discussed the chronological development of the two types of dative markers. See also Li and Wu (2015) for the development of dative markers in Yichun Gan.

In this paper, we present five types of dative markers from a synchronic perspective on the one hand, and we explore four grammaticalization pathways underlying these various types of dative markers on the other. Grammaticalization is defined as the development from lexical to grammatical forms and from grammatical to even more grammatical forms (Kuteva et al. 2019, p. 3). Cross-linguistically, the dative markers are frequently derived from allative markers, GIVE verbs, and benefactive markers (Kuteva et al. 2019).

In the languages that we investigated, we observe all these three patterns: namely, the dative marker shares the same form as either the allative marker, the GIVE verb, or the benefactive marker in each language. However, in order to clarify how the dative use was developed from these sources, especially for the GIVE verbs which are generally TAKE verbs in origin, we take the passive markers and differential object markers which are closely related to GIVE/TAKE verbs into consideration and refine the three main patterns into five: DAT = ALL; DAT = GIVE = OM ≠ PASS; DAT = GIVE = OM = PASS; DAT = GIVE = PASS ≠ OM; DAT = BEN. The detail of our methodology is presented in Section 2.

The layout of this article is as follows: this introduction leads into Section 2, which presents our definitions for the markers and relevant constructions, our terminology and methodology. We take allative markers, GIVE verbs, benefactive markers, passive markers, and differential object markers into consideration, and classify the 30 languages into five types. They will be discussed in detail in Section 3 with a map showing their areal distribution. The relevant diachronic developments of dative markers are found in Section 4 and are followed by a conclusion in Section 5.

2. Methodology and Definitions

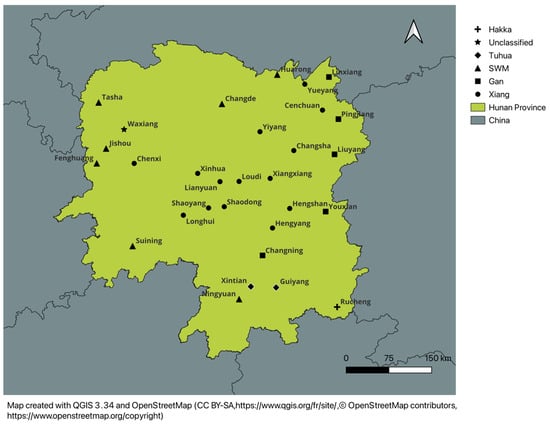

The sample of 30 languages spoken in the Hunan Province covers the five groups of Sinitic languages (i.e., Xiang, Gan, Southwestern Mandarin, Hakka, and Tuhua) and one unclassified one (i.e., Waxiang). Both fieldwork data and data from descriptive grammars and journal articles are used. Data are glossed and translated by the author when not provided in the original literature. The locations of all the languages can be found in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The locations of the sample languages.

In this paper, only the dative marker in the main2 ditransitive construction of the language is considered. As indicated in Zhang (2011), the Southern Sinitic languages3 use the postverbal dative construction4 [V + T(heme) + DAT + R(ecipient)] to encode transfer. This is the case for most of our sample languages. However, the preverbal dative construction [DAT + R+V + T] is also attested as the main type in some languages spoken in northwestern Hunan, such as in Waxiang. For the languages that use postverbal dative markers, we can identify two primary patterns: DAT = ALL and DAT = GIVE; for the languages that use preverbal dative markers, we can find a third pattern: DAT = BEN.

The dative markers that are related to allative markers and benefactive markers are relatively straightforward to identify and analyze, but when the dative marker shares the same form as the GIVE verb, we need to further confirm how the dative use is developed from the GIVE verb. Regarding the GIVE verbs, it refers to the general-purpose verb of giving in this paper, such as gěi 给 in Standard Mandarin or give in English. GIVE verbs have been extensively discussed in the literature due to their polyfunctionality in Sinitic languages (see Lai 2001; Chin 2011; Ngai 2015; Lu and Szeto 2023). For instance, in Standard Mandarin, gěi can act as a benefactive marker, dative marker, causative verb, passive marker, and differential object marker. However, in the Southern Sinitic languages, the GIVE verbs are more diverse in forms, such as pa41 把 in Changsha, te22 得 in Hengyang, and lɛ44 拿 in Lianyuan from our sample, and they are TAKE5 verbs in origin. Furthermore, in most cases, they manifest different syntactic behaviors from gěi in Northern Sinitic languages. See the two example sentences below in Standard Mandarin and in Huarong.

| (1) Standard Mandarin (Zhu 2009, p. 170) | ||||

| 给 | 我 | 一 | 枝 | 笔。 |

| gěi | wǒ | yì | zhī | bǐ |

| give | 1sg | one | clf | pen |

| ‘Give me a pen.’ | ||||

| (2) Huarong (SWM; own fieldwork) | ||||

| 把 | 本 | 书 | 得 | 我。 |

| pɑ21 | pən21 | ɕy53 | tɛ13 | ŋo21 |

| give | clf | book | dat | 1sg |

| ‘Give me a book.’ | ||||

The GIVE verbs which can take an R argument (in addition to a T argument) will be considered as a genuine GIVE verb in this analysis (cf. Zhang 2011), like the case in Standard Mandarin; while some GIVE verbs can only take a T argument but not an R argument, they solely have the semantic meaning of giving, like the case in Huarong6. When we consider that a dative marker is grammaticalized from a GIVE verb, it is generally the genuine GIVE verbs that we talk about, since it can precede an R argument and can be easily reanalyzed as a dative marker from V2 position in a serial verb construction, as illustrated by (3).

| (3) Standard Mandarin (Zhu 1979, p. 83) | ||||||

| 我 | 送 | 一 | 张 | 票 | 给 | 小李。 |

| wǒ | song | yì | zhāng | piào | gěi | Xiǎolǐ |

| 1sg | offer | one | clf | ticket | dat | Xiaoli |

| ‘I offered a ticket to Xiaoli.’ | ||||||

In Hunan, most GIVE verbs are originally TAKE verbs, and they form postverbal dative constructions but not double object constructions, which means they take a T argument but not R argument. However, some of these GIVE<TAKE verbs can also be used as a dative marker. Take Changsha, for example: the GIVE<TAKE verb and the dative marker are both pa41 把. The process of how the dative marker is developed from a GIVE<TAKE verb will be discussed in detail in Section 4.2.

Zhang (2011) claims Southern Sinitic languages lack genuine GIVE verbs, and the ditransitive constructions in Southern Sinitic languages are formed by the combination of TAKE verbs and a directional element which can be templated as [TAKE + T + ALL + R]. It is exactly in this construction that TAKE verbs obtained the semantic meaning of giving. On the basis of this construction, when the T argument shows preverbally (could be topicalized or marked by an object marker) or simply mentioned in the previous context, we have [TAKE + ALL + R], and according to Zhang (2011), [TAKE-ALL] becomes a genuine GIVE verb, which can precede the R argument directly, and form a serial verb construction with the GIVE<TAKE verb in ditransitive constructions, whence it can be reanalyzed as a compound dative marker: [GIVE<TAKE + T + DAT<[TAKE-ALL] + R]. Then, due to the frequent use, the allative marker might be omitted from the compound form, leaving the TAKE verb in the language as a dative marker alone: [GIVE<TAKE + T + DAT<TAKE + R].

These developmental stages can still be observed in many Southern Sinitic languages, such as in Shanghai Wu (Qian 1997), Yichun Gan (Li and Wu 2015), and Liancheng Hakka (Ye 2023). Take Yichun as an example. At first, the directional element ku42 过 is used to mark the recipient:

| (4) Yichun (Gan; Li and Wu 2015) | |||||||

| 我 | 把 | 本 | 书 | 过 | 你。 | [GIVE<TAKE + T + ALL + R] | |

| ŋo34 | pa42 | pun42 | ɕy34 | ku42 | ɲi34 | ||

| 1sg | give | clf | book | dat | 2sg | ||

| ‘I gave a book to you.’ | |||||||

Then, the GIVE<TAKE verb combines with the directional element and forms a compound genuine GIVE verb as pa42-ku42 把过 which can take a recipient as its argument. This compound form is then reanalyzed as a dative marker in a serial verb construction:

| (5) | 我 | 把 | 本 | 书 | 把过 | 你。 | [GIVE<TAKE + T + DAT<[TAKE-ALL] + R] | |

| ŋo34 | pa42 | pun42 | ɕy34 | pa42-ku42 | ɲi34 | |||

| 1sg | give | clf | book | dat | 2sg | |||

| ‘I gave a book to you.’ | ||||||||

Finally, the directional element dropped off and the GIVE<TAKE verb alone becomes a new dative marker in Yichun:

| (6) | 把 | 本 | 书 | 把 | 你。 | [GIVE<TAKE + T + DAT<TAKE + R] | |

| pa42 | pun42 | ɕy34 | pa42 | ɲi34 | |||

| give | clf | book | dat | 2sg | |||

| ‘Give a book to you.’ | |||||||

This is the first possible diachronic development for the dative markers that have the same form as the GIVE<TAKE verbs. Note that although the dative marker has the same form as the GIVE<TAKE verb in the language, it does not mean the GIVE<TAKE has become a genuine GIVE verb, because the dative marker is developed by dropping off the allative element from a genuine compound GIVE verb, but is not developed from the GIVE<TAKE verb itself. (Nevertheless, it is possible for the GIVE<TAKE verb to develops further into a genuine GIVE verb on this basis.)

The second possible explanation for a dative marker sharing the same form as the GIVE<TAKE verbs is the that GIVE<TAKE verb becomes a genuine GIVE verb through relexicalization (Güldemann 2012), and the dative use is developed from the genuine GIVE verb. This is a case mentioned in Shaowu (Ngai 2015; 2021, p. 384).

To help us tell if the GIVE<TAKE has become a genuine GIVE verb in the language, we need to take two other makers into consideration: passive markers and differential object makers.

Chappell and Peyraube (2006) argued “GIVE > permissive causative > passive” is a common grammaticalization pathway in Sinitic languages, such as gěi in Beijing Mandarin or 俾 pei35 in Cantonese. Below is an example of the bridging stage for the reanalysis. In (7), gěi can actually be interpreted as ‘to give’ in a pivot construction, a permissive causative marker, or a passive marker.

| (7) Beijing Mandarin (Xu 1992) | ||||

| 车 | 给 | 小王 | 修好 | 了。 |

| chē | gěi | Xiǎowáng | xiū-hǎo | le |

| car | give/let/pass | Xiaowang | repair-be.good | crs |

| ‘(Someone) gave the car to Xiaowang (and he) repaired it.’ | ||||

| or ‘(Someone) let Xiaowang have the car repaired.’ | ||||

| or ‘The car was repaired by Xiaowang.’ | ||||

The key point for the reanalysis is that the argument after the GIVE verb has to be an R argument, which can be considered as a causee in the causative construction or an agent in the passive construction. If the GIVE<TAKE verb in a language can be used as a passive marker, we can consider that the GIVE<TAKE verb in this language is a genuine GIVE verb, thus making it also possible to develop a dative use. On the contrary, if the GIVE<TAKE verb in a language cannot be used as a passive marker, we can consider that it might still stay as a TAKE verb, or at least its GIVE use is not yet well developed.

As for the differential object marker, Chappell (2007) outlines two common grammaticalization pathways for the object markers in Sinitic languages: (i) TAKE (>instrumental) > OM; (ii) GIVE > benefactive > OM. If an object marker is developed from the GIVE verb, generally it has to undergo an intermediate stage as a benefactive marker. While the pathway from TAKE to object marker is much more common, such as bǎ 把 in many Northern Sinitic languages. For the languages in Hunan, if the object marker has the same form as the GIVE<TAKE verb, and we cannot find an identical benefactive marker, then we can consider the object marker in these languages to be more likely to be developed from the TAKE use of their GIVE<TAKE verbs in the history.

In summary, we take passive makers and differential object markers into consideration to help us decide whether the GIVE<TAKE verbs in our sample are genuine GIVE verbs that can develop a dative use, or they are still a TAKE verb that has gained a dative use by dropping off the allative element in a compound GIVE verb. When DAT = GIVE = PASS ≠ OM, it is more likely to be the former case; when DAT = GIVE = OM ≠ PASS, it is perhaps the latter case especially when a compound GIVE verb form can be found in the language; finally for the syncretism DAT = GIVE = PASS = OM, both cases are possible. All the grammaticalization pathways will be explained in detail in Section 4.

Therefore, in this paper, we investigate six elements: dative markers, allative markers, benefactive markers, passive markers, differential object markers, and GIVE verbs. According to the data, we can classify the languages in our sample into five types: DAT = ALL; DAT = GIVE = OM ≠ PASS; DAT = GIVE = PASS = OM; DAT = GIVE = PASS ≠ OM; DAT = BEN.

The definitions for the five grammatical markers are given in the following part.

A dative marker or an indirect object marker marks the recipient in a ditransitive construction. It can be a postverbal marker, as in (8), or a preverbal marker, as in (9).

| (8) Ningyuan (SWM; Y. Wu 2009, p. 321) | ||||||

| 他 | 送 | 一 | 杆 | 笔 | 给 | 我。 |

| t’a33 | soŋ213 | i21 | kan45 | pi21 | kə45 | ŋo213 |

| 3sg | offer | one | clf | pen | dat | 1sg |

| ‘He offered a pen to me.’ | ||||||

| (9) Ningyuan (SWM; Zhang 2009) | |||||

| 有 | 话 | 就 | 和 | 牛 | 讲。 |

| iəu45 | fa213 | tɕiəu213 | xo21 | liəu21 | tɕiaŋ45 |

| have | speech | then | dat | buffalo | say |

| ‘(He) talks to the buffalo when (he) has something to say.’ | |||||

In (8), the dative marker is kə45 给, whereas in (9), the dative marker is xo21 和. Note that the preverbal xo21 can have other interpretations as well, such as being a benefactive marker, as demonstrated by an example in (10).

| (10) Ningyuan (SWM; Zhang 2009) | ||||||||

| 这里 | 景子 | 好, | 你 | 和 | 我 | 照 | 个 | 相。 |

| tɕi213li45 | tɕin45tsɿ45 | xau45 | li45 | xo21 | ŋo45 | tɕiau213 | ko213 | ɕiaŋ213 |

| here | view | good | 2sg | ben | 1sg | take | clf | photo |

| ‘The view is great here, take a photo for me.’ | ||||||||

A benefactive marker is a preverbal marker, which marks the beneficiary. In this paper, we consider it as a distinct class of markers from dative markers. However, it is worth noting that a benefactive marker can develop into a preverbal dative marker, as is the case in Ningyuan.

An allative marker expresses “the meaning of motion ‘to’ or ‘towards’ a place” (Crystal 2003, p. 19). As such, it marks the goal in a theme-goal construction, for example, as tau45 in Ningyuan.

| (11) Ningyuan (SWM; Y. Wu 2009, p. 321) | |||||||||

| 我 | 给 | 毛毛崽 | 给 | 倒 | 床 | 高头 | 要 | 不 | 要得? |

| ŋo45 | kə45 | mau21mau21tsæ45 | kə45 | tau45 | ts’uan21 | kau33t’əu21 | iau213 | pu21 | iau213tə21 |

| 1sg | om | baby | put | all | bed | on | ok | neg | ok |

| ‘Is it ok that I put the baby on the bed?’ | |||||||||

A passive marker is used to mark the agent in a passive construction. Sometimes, the passive marker shares the same form as the dative marker in the Sinitic languages. For instance, the dative marker kə45 can also be used as a passive marker.

| (12) Ningyuan (SWM; Y. Wu 2009, p. 321) | |||||

| 杯子 | 给 | 他 | 打烂 | 呱 | 了。 |

| pei33tsɿ45 | kə45 | t’a33 | ta45-lan213 | kua21 | liau45 |

| cup | pass | 3sg | hit-be.broken | cmpl | crs |

| ‘The cup was broken by him.’ | |||||

A differential object marker or disposal marker marks the object in a transitive sentence or the T argument in a ditransitive or theme-goal sentence. It might also share the same form as the dative marker. In Ningyuan, kə45 is also used as a differential object marker, as already shown in (11). Another example is given in (13).

| (13) Ningyuan (SWM; Zhang 2009) | |||||

| 给 | 那 | 本 | 书 | 拿 | 过来。 |

| kə45 | la213 | pən45 | ɕy33 | la21 | ko213-læi21 |

| om | that | clf | book | take | pass-come |

| ‘Bring that book over here.’ | |||||

The forms of the dative markers of the 30 Hunan Sinitic languages are listed in Table 1. Except for the GIVE verbs, the other elements examined in this paper, namely benefactive, allative, object, and passive markers, generally have several forms that developed from different sources. Since we are investigating the dative markers in this paper, we only list the forms that are identical or related to the dative markers. However, note that an empty cell may also indicate that we have not found the relevant form in the literature.

Table 1.

Dative, benefactive, allative, passive, and object markers and GIVE verbs in the sample of 30 languages.

In the next section, we discuss the five different types of dative markers and their distribution.

3. The Five Types of Dative Markers and Their Areal Distribution

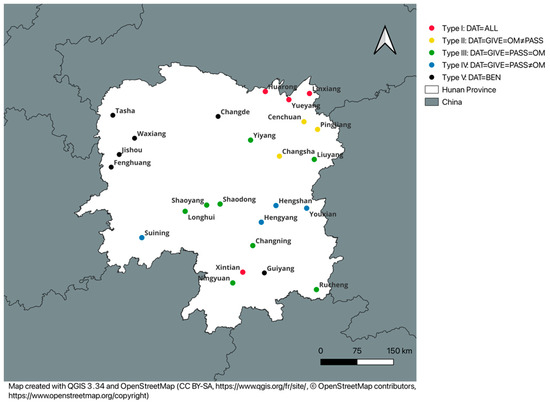

Based on the analysis of 30 Sinitic languages spoken in Hunan, which include Xiang, Gan, Southwestern Mandarin, Hakka, Tuhua, and one unclassified Sinitic language, we identify five patterns for the dative markers, as detailed in Table 2. The dative markers are given after each language. Following this table, the areal distribution of these four types is presented in Figure 2.

Table 2.

Five types of dative markers.

Figure 2.

The distribution for the different types of dative markers.

3.1. Type I: DAT = ALL (4/30)

In Type I languages, the dative marker is the same as allative marker. In our sample, this type is mainly found in the northeast of Hunan: Huarong (SWM), Yueyang (Xiang), Linxiang (Gan), apart from Xintian (Tuhua) in the south. Take Huarong, for example.

| (14) Huarong (SWM; own field work) | |||||

| Dative construction | |||||

| 买 | 哒 | 个 | 褂子 | 得 | 我。 |

| mai21 | ta21 | ko33 | kuɑ24tsɿ33 | tɛ13 | ŋo21 |

| buy | pfv | clf | coat | dat | 1sg |

| ‘(He) bought me a coat.’ | |||||

| (15) Allative construction | ||||||||

| 我 | 挂 | 哒 | 一 | 张 | 全家福 | 得 | 客厅 | 的 |

| ŋo21 | kuɑ24 | tɑ21 | i45 | tsɑŋ53 | tɕɦyn13tɕia53fu13 | tɛ13 | kɦɛ24tɦiɛn53 | ti33 |

| 1SG | hang | PFV | one | CLF | family.photo | ALL | living.room | POSS |

| 墙上。 | ||||||||

| tɕɦiɑŋ13 = sɑŋ21 | ||||||||

| wall = on | ||||||||

| ‘I hung a family photo on the wall in the living room.’ | ||||||||

In this type of language, the GIVE verb is always BA 把, and three of the four languages use DE 得 as the dative marker, while one language (i.e., Xintian) uses kəu35 whose etymological source is not clear. In Section 4.1, we will discuss the developmental path of DE as a dative marker in this type of language, using Huarong as an example.

3.2. Type II: DAT = GIVE = OM ≠ PASS (3/30)

There are three languages of Type II in our sample, they are Cenchuan (Xiang), Changsha (Xiang), and Pingjiang (Gan) which are in the north central region of the Hunan Province. They use BA 把 as the GIVE verb as well as the dative marker. Take Changsha as an example.

| (16) Changsha (Xiang; Wu 2011, p. 188; Y. Wu 2009, p. 309) | |||||||

| Dative construction | |||||||

| 他 | 送 | 哒 | 三 | 只 | 鸡 | 把 | 我。 |

| tha33 | sən45 | ta21 | san33 | tsa24 | tɕi33 | pa41 | ŋo41 |

| 3sg | offer | pfv | three | clf | chicken | dat | 1sg |

| ‘He gave me three chickens as a gift.’ | |||||||

| (17) Differential object marking construction | ||

| 把 | 窗户 | 打开。 |

| pa41 | tɕhyan33fu | ta41-khai33 |

| om | window | make-open |

| ‘Open the window.’ | ||

| (18) Passive construction | ||||

| 杯子 | 把得/捞/听 | 他 | 打烂 | 哒。 |

| pei33tsɿ | pa41tɤ24/lau33/t’in45 | t’a33 | ta41-lan21 | ta21 |

| glass | pass | 3sg | hit-be.broken | crs |

| ‘The glass was broken by him.’ | ||||

Note that, as shown in (18), the compound form pa41tɤ24 can be used as the passive marker, and tɤ24 得 is exactly the allative marker in Changsha. We can consider the dative use of pa41 把 is based on the compound GIVE verb pa41tɤ24, which gradually lost its allative element in it, hence pa41 alone is used as the dative marker. In Cenchuan and Pingjiang, we do not have the necessary data to tell if they have or had a compound form.

3.3. Type III: DAT = GIVE = PASS = OM (8/30)

The dative markers of the Type III languages are the same as their passive markers and differential object markers. In our sample, there are actually 10 languages mostly spoken in the central and south of Hunan that share the pattern. Nonetheless, as introduced in Section 2, the Type II, III, and IV languages are refined from the pattern: DAT = GIVE, so, for this reason, we exclude Xiangxiang and Lianyuan, which use the same marker for dative, passive, and object marking but have a distinct verb form for GIVE. As a result, we can only classify eight languages into this type. These are three Xiang varieties: Shaoyang, Shaodong, and Lianyuan; one Southwestern Mandarin variety: Ningyuan; two Gan varieties: Liuyang and Changning; and one Hakka variety: Rucheng. Take Shaodong, for example.

| (19) Shaodong (Xiang; Sun 2009, pp. 105–12) | |||||||

| Dative construction | |||||||

| 咯 | 只 | 衣衫 | 其 | 送 | 把 | 小明 | 哩。 |

| ko31 | tɕia55-31 | iɛn55san31 | tɕi31 | səŋ35 | pa31 | ɕio31min12 | li |

| this | clf | clothes | 3sg | offer | dat | XiaomingNAME | sfp |

| ‘He gave this clothing to Xiaoming.’ | |||||||

| (20) Passive construction | |||||||||

| 其 | 只 | 脚 | 把 | 车子 | 闯 | 哩, | 现唧 | 还 | 在 |

| tɕi31 | tɕia55-31 | to55 | pa31 | t’ei55tsɿ | ts’aŋ31 | li | ɣiɛn12·tɕi | ɣa12 | dzei12 |

| 3SG | clf | foot | pass | car | hit | sfp | now | still | LOC |

| 医院里 | 诊。 | ||||||||

| i55yɛn35-55 = li31 | taŋ3 | ||||||||

| hospital = inside | treat | ||||||||

| ‘His foot was hit by a car, and he is still in the hospital.’ | |||||||||

| (21) Differential object marking construction | ||||||

| 要 | 妹妹 | 把 | 屋 | 扫 | 一 | 下 |

| io35 | mei35·mei | pa31 | u55 | sau35 | i55 | ɣa24 |

| make | little.sister | om | house | sweep | one | vcl |

| ‘Make little sister to clean up the house.’ | ||||||

Generally speaking, the dative marker in Type III languages also shares the same form as the GIVE verb. The GIVE verbs in this type are not limited to the types that are originally TAKE verbs (e.g., pa31 把 in Shaodong or te33 得 in Changning). In Ningyuan, it is kə45 给 (which shares the same etymology as gěi in Standard Mandarin) that is used as the GIVE verb, and it can also be used as a dative marker, a passive marker and a differential object marker.

For this type of language, there are three possibilities. The dative marker could be developed from a genuine GIVE verb, like the case of Ningyuan just mentioned; or either the GIVE<TAKE verbs have been shifted to genuine GIVE verbs, and then developed a dative use; or the GIVE<TAKE verb combines an allative form and becomes a compound genuine GIVE verb, then the compound form loses the allative element and, subsequently, the GIVE<TAKE verb itself becomes the dative marker.

3.4. Type IV: DAT = GIVE = PASS ≠ OM (4/30)

In Type IV languages, the dative markers are the same as passive markers, but different from the object markers. This type is mainly found in southern Hunan, such as in Hengshan (Xiang), Hengyang (Xiang), Youxian (Gan), Changning (Gan), and Suining (SWM).

| (22) Youxian (Gan; Dong 2009, pp. 36–38; Y. Wu 2009, p. 313) | |||||

| Dative construction | |||||

| 其 | 送 | 支 | 笔 | 得 | 我。 |

| tɕi51 | səŋ11 | tsɿ | pi44 | te44 | ŋo11 |

| 3sg | offer | clf | pen | dat | 1sg |

| ‘He offered me a pen.’ | |||||

| (23) Passive construction | ||||

| 小芳 | 得 | 爱婆 | 接走 | 哩。 |

| ɕiau51faŋ44 | te44 | ŋəø11p’o213 | tɕie44-tsei51 | li |

| XiaofangNAME | pass | grandmother | pick.up-be.away | sfp |

| ‘Xiaofang was picked up by her grandmother.’ | ||||

| (24) Differential object marking construction | |||||||

| 我 | 把 | 毛毛 | 放 | 到 | 床上 | 要得 | 不? |

| ŋo11 | pa51 | mau213mau | faŋ11 | tau | t’aŋ213=ɕiaŋ | iau11te | pu |

| 1sg | om | baby | put | all | bed=on | ok | neg |

| ‘Is it okay if I put the baby on the bed?’ | |||||||

In all the six languages of this type, the GIVE<TAKE verbs have developed both dative and passive uses. In this group, except for Suining, which uses pa55 把 as a verb of giving, the other seven languages all use DE 得. Both the dative marker and the passive marker share the same form with the GIVE<TAKE verb. In Section 4.2.2, we will take Hengyang as an example to discuss how DE develops into a dative marker from GIVE<TAKE in this type of languages.

3.5. Type V: DAT = BEN (6/30)

This type of language is very easy to differentiate from the other types because it uses a preverbal dative construction. Note that, for some of these languages, the dative marker may also have the same form as the object marker, but since it is a preverbal marker, and it is not derived from the GIVE verb, we do not classify these languages into Type II languages. There are six languages in our sample that share this pattern, and they are found in the northwest of Hunan. Their GIVE verbs are more diversified, and sometimes the etymological sources for the GIVE verbs are not so clear. For instance, Guiyang (Tuhua) uses ta45 带 or uã33 弯 as the GIVE verb, but when it forms a ditransitive construction, it has to use [ta45 + R + uã33 + T]; Fenghuang (SWM) and Jishou (SWM) use fən55 分 as the GIVE verb, Waxiang (unclassified) uses tɤ55 得, Tasha (SWM) uses ko24 过, and Changde (SWM) uses pa21 把.

For the six languages of Type V, the dative markers have not developed from the GIVE verbs. The main ditransitive constructions for them are formed on the basis of the benefactive construction. Take Jishou, for instance.

| (25) Jishou (SWM; Li 2002, p. 318) | |||||

| Benefactive construction | |||||

| 医生 | 倒 | 帮 | 他 | 看 | 病? |

| i55sən55 | tau | paŋ55 | t’a55 | k’an35 | pin35 |

| doctor | prog | ben | 3sg | see | illness |

| ‘The doctor is treating him.’ | |||||

| (26) Dative construction | |||||||

| 我 | 一 | 到 | 学校, | 就 | 帮 | 屋里 | 打 |

| ŋo42 | i11 | tau35 | ɕio11ɕiau35 | tɕiəu35 | paŋ5 | u11li | ta42 |

| 1SG | once | arrive | school | then | dat | home | make |

| 了 | 个 | 电话。 | |||||

| lə | ko | tian35xua3 | |||||

| pfv | clf | phone.call | |||||

| ‘As soon as I got to school, I called home.’ | |||||||

The verbs that are used in the benefactive construction are transitive verbs, but they do not necessarily indicate transfer (Zhu 1979). The argument introduced by the benefactive marker is a beneficiary. As we can see from (25), the verb is ‘to see (the patient), to treat (the illness)’, and 3rd person singular is the beneficiary, while for the dative construction, the verbs are either intrinsically ditransitive verbs that express transfer or verbs of saying that concern an addressee. As shown in (26), the verb is ‘to call’, and the preverbal argument is an addressee.

In this group of languages, dative markers are developed from preverbal benefactive markers and have little to do with GIVE verbs in the given language. Four of these languages can use GEN 跟 as a preverbal dative marker, and one uses GEI 给. In Section 4.3, we will discuss the grammaticalization path of kai55 跟 in Waxiang as an example.

3.6. Interim Summary: The Areal Distribution

Except for Xiangxiang and Lianyuan, which we exclude from the Type III languages, there are other three languages in our sample that do not fit into any types that we have classified. They are three Xiang varieties: Loudi, Xinhua, and Chenxi. In Loudi, the dative marker is another verb of giving sɿ5 赐, while the GIVE<TAKE verb that is used in the ditransitive construction is nõ44 拿, which can also be used as a differential object marker. The postverbal dative construction in Loudi can be templated as [nõ44 + T+ sɿ5 + R], and the passive marker is the compound form nõ44sɿ5. Note that in Modern Chinese, the compound form bǎyǔ 把与 which combines a TAKE verb and a former GIVE verb has also existed (Mao 2022). sɿ5 no longer has a verbal use in Loudi, which suggests that it is probably a GIVE verb belonging to an older layer. In Xinhua at an earlier stage, the dative marker is læ13 来, and it is different from the GIVE verb lɔ21 拿or the allative marker tɔ45 到. In some varieties of Wu, 来 is identical to the allative marker that is also used as dative marker (Chin 2010). It is possible that læ13 was the allative marker in Xinhua before, but since we do not have any record in the literature, we cannot include Xinhua into Type I language. In Chenxi, the GIVE verb and the dative marker are both ko324 过, producing the dative construction is [ko324 + T+ ko324 + R]. At the same time, the double object construction is also attested in Chenxi as [ko324 + R + T], but the detailed uses of ko324 and its developments cannot be found in the literature, meaning that we cannot draw a credible conclusion as to how it developed the dative use. So, in our discussion, we exclude these three languages.

To conclude, we classify the languages in our sample into five main groups according to the dative constructions and the polyfunctionality of dative markers. The Type I languages have a dative marker that is identical to the allative marker, and they are mainly found in northeastern Hunan. In the Type II, III, and IV languages, the dative markers have the same form as the GIVE verbs. The dative markers in Type II languages are identical to their differential object makers. There was probably a compound GIVE verb in the history for these languages. As for the Type III languages, they are spread over central and southern Hunan. Their dative markers share the same form as the passive markers and the differential object markers. This pattern can be explained by two possible grammaticalization pathways. The type IV languages are mostly found in southern Hunan, and their dative markers are the same as the passive markers but different from the object markers. The Type V languages have various sources for GIVE verbs, and their main type of ditransitive constructions is the preverbal dative constructions. They are found in northwestern Hunan.

4. Diachronic Sources and Developments for the Dative Markers

In this section, we discuss the pathways of development for dative markers. There are three main grammaticalization pathways behind the synchronic distribution of different patterns of dative markers, as shown below. We will discuss these pathways with a language in our sample one by one.

- Allative > Dative

- (TAKE >) GIVE > Dative

- [TAKE-ALL] > GIVE > Dative; TAKE > Dative

- (TAKE >) GIVE > Dative

- Benefactive > Dative

4.1. ALL > DAT

Using the allative marker to mark the recipient is common in the languages across the world (Kuteva et al. 2019; Rice and Kabata 2007), such as to in English or à in French. Malchukov et al. (2010, p. 52) also show that the theme-goal construction and the ditransitive construction often overlap in a semantic map for many languages, such as in Finnish. Allative markers being the source for the dative markers in Sinitic languages has already been discussed in the literature. For example, Chin (2010) claimed there are two types of indirect object marker (i.e., dative marker) in Chinese: the go-type and the give-type. He mentioned that YU 于 in the oracle-bone inscriptions, LAI 来 in 17th century Wu, DU 度 in 16th century Min and GUO 过 in 19th century Yue are all directional verbs that can be used as dative markers. Li and Wu (2015) also mentioned that the directional element ku42 过 can be used as a dative marker in Yichun Gan. For some languages spoken in northeastern Hunan, the theme-goal construction and the ditransitive construction can both be realized with the same syntactic template and share a same marker. What the literature lacks is an exploration of the developmental stages through which an allative marker acquires a dative use.

We take Huarong as an example and show how the allative tɛ13 得 developed its dative use. In Huarong, tɛ13 can be used as a verb which means ‘get, obtain’, see an example in (27).

| (27) Huarong (SWM; own fieldwork) | ||||

| 他 | 得 | 哒 | 头名。 | (GET) |

| lɑ33 | tɛ13 | tɑ21 | ɣou13miɛn13 | |

| 3sg | get | pfv | first.rank | |

| ‘He won the first place.’ | ||||

It can be used as an allative or dative marker either directly after the verb or after the T argument. The former case is more frequently found in my corpus of Huarong and in the literature of other languages using DE 得as an allative/dative marker.

| (28) | 他 | 把 | 车 | 停 | 得 | 路 | 边上 | 哒。 | (Allative) |

| lɑ33 | pɑ21 | tsɦɛ53 | tɦiɛn13 | tɛ33 | lou33 | pin53sɑŋ21 | tɑ21 | ||

| 3SG | OM | car | park | ALL | road | side | CRS | ||

| ‘He parked the car on the side of the road.’ | |||||||||

| (29) | 他 | 捡 | 哒 | 两 | 百 | 块 | 钱 | 得 | 枕头 |

| lɑ33 | tɕin21 | tɑ21 | liɑŋ21 | pɛ45 | kɦuai21 | tɕɦin13 | tɛ13 | tsən21lou33 | |

| 3sg | hide | pfv | two | hundred | currency.unit | money | all | pillow | |

| 下头。 | |||||||||

| ɕia33lou21 | |||||||||

| below | |||||||||

| ‘He hid two hundred yuan under the pillow.’ | (Allative) | ||||||||

| (30) | 他 | 书 | 把 | 得 | 我 | 哒。 | (Dative) |

| lɑ33 | ɕy53 | pɑ21 | tɛ33 | ŋo21 | tɑ21 | ||

| 3sg | book | give | dat | 1sg | crs | ||

| ‘He gave the book to me.’ | |||||||

| (31) | 他 | 送 | 哒 | 一 | 包 | 烟 | 得 | 爷。 | (Dative) |

| lɑ33 | sɤŋ24 | tɑ21 | i45 | pɑu53 | iɛn53 | tɛ13 | ia13 | ||

| 3sg | offer | pfv | one | packet | cigarette | dat | father | ||

| ‘He offered a packet of cigarette to father.’ | |||||||||

In the diachronic data, DE firstly appeared after the verbs having the meaning ‘to get’ in the Western Han Dynasty (202BC-8AD), as in (32). Then, it is found after the verbs which do not have the GET meaning; it can be analyzed as a phase complement which expresses the phase of an action in the first verb (Chao 1968), see (33).

| (32) | 赵 | 使 | 人 | 微 | 捕得 | 李牧 |

| zhào | shǐ | rén | wēi | bǔ-dé | Lǐ Mù | |

| Zhao | order | people | secretly | catch-get | Li Mu | |

| ‘Zhao ordered people to secretly arrest Li Mu.’ | ||||||

| (史记·廉颇蔺相如列传 [Records of the Grand Historian: Biography of Lian Po and Lin Xiangru], cited from Ma 2003, p. 20, glossing is mine) | ||||||

| (33) | 武丁 | 夜 | 梦得 | 圣人 |

| Wǔ Dīng | yè | mèng-dé | Shèngrén | |

| Wu Ding | night | dream-get | saint | |

| ‘Wu Ding dreamed of a saint at night.’ | ||||

| (史记·殷本纪 [Records of the Grand Historian: Biography of Yin Ben], cited from Ma 2003, p. 22, glossing is mine) | ||||

Note that in the historical documents for Mandarin, DE has not developed an allative use to mark a goal. However, Lamarre (2009) discussed the goal marker in the Northern Sinitic languages, such as de 的 in Beijing Mandarin (Zhu 2009, p. 115; Xu 1994), təʔ4 得 in the Jin variety of Shenmu (Xing 2000; 2002, p. 596), or DE 得 in the Xiang variety of Changsha (Wu 2011, pp. 231–48). The origin of these goal markers is difficult to identify. Xu (1994) argues that de in Beijing Mandarin comes from ZHE 着, which is used as a preposition in the Dunhuang Variant Texts Collection (Dūnhuáng biàn wén敦煌变文), while Xing (2000, 2002) and Wu (2011) suggest that the source of the goal marker in Shenmu and Changsha is DE 得. Regardless of the etymological source, what these analyses have in common is that the goal marker comes from a bounded marker (yǒujiè biāojì有界标记 in Lamarre 2009) in the language. This is consistent with the use of DE 得as a phase complement that we mentioned in (33).

In fact, Wu (2001, pp. 53–54) proposed several phases for the diachronic development of the locative marker tɤ24 得 in Changsha:

- it was used as a main verb meaning ‘get’, ‘catch’.

- it was used as the second verb after a main verb with a meaning similar to ‘get’, such as ‘buy’, ‘have’.

- it was used as a verb complement to indicate the result or completion of an action. In this phase, it often took a locative noun as its object, as [V + DE + Place], and it could be reanalyzed as a preposition or an aspectual marker.

We agree with this analysis. We propose that from the phase complement in [V-DE], when DE is followed by a place, it is reanalyzed as an allative marker. Then, through metaphorical extension DE can be considered as a dative marker when it precedes a person instead of a place (a parallel development for 于 yú in Old Chinese is discussed in Ye 2020).

4.2. (TAKE >) GIVE > DAT

Dative markers developing from a genuine GIVE verb is a very common pathway described in the literature, but as we mentioned before, the GIVE verbs in the Northern and Southern Sinitic languages are different from a syntactic perspective. Hashimoto (1976) has pointed out that the northern GIVE verbs form double object constructions of the form: [GIVE + R + T], while the Southern GIVE verbs generally form inverted double object construction: [GIVE + T + R]. Zhang (2011) claims that the main difference for ditransitive constructions between Northern and Southern Sinitic languages is that the Northern Sinitic languages use double object construction, while the Southern Sinitic languages use postverbal dative construction [GIVE + T + DAT + R], and the inverted double object construction is developed on the basis of the postverbal dative construction with the dative marker omitted.

We discuss how a GIVE<TAKE verb which can only precede the T argument in the ditransitive constructions becomes a dative marker which introduces the R argument. We propose that the dative marker is developed from the GIVE<TAKE verb that appears in the second position of a serial verb construction [GIVE<TAKE + T+GIVE + R]. It concerns two possible developments.

4.2.1. Allative Element Dropping off from the Compound GIVE<[TAKE-ALL]

This development has been discussed by Li and Wu (2015) in Gan languages, as already shown in Section 2. For this pathway, the GIVE verbs are TAKE verbs in origin. The TAKE verb can only take a theme argument and cannot precede the recipient directly. When it forms a ditransitive construction, it borrows the allative marker as a dative to introduce the recipient, as in [TAKE + T + ALL + R]. Next, the TAKE verb combines with the allative marker and becomes a compound GIVE verb [TAKE-ALL] which can be further reanalyzed as a dative marker in V2 position of a serial verb construction. Then, the compound GIVE verb loses the allative element after a long period of frequent use and leaves the TAKE verb itself to become a dative marker.

We cannot present all the stages with our data of Type II languages. As we can see in (18), a compound form pa41tɤ24 把得 exists in Changsha, but we cannot find an example with pa41tɤ24 being a genuine GIVE verb or a dative marker. Only its use as a passive marker suggests that it was probably a genuine GIVE verb before.

Nevertheless, we can observe this development with the data in Yueyang. The primary dative marker is tə 得, as shown in (34). pa42tə 把得 can be used as a GIVE verb, as shown in (35). In fact, according to my own fieldwork, among the young speakers of Yueyang, pa42 把 is also accepted as a dative marker, as shown in (36).

| (34) Yueyang (Xiang; Fang 1999, pp. 222–24, own field work) | |||||

| 拿 | 件 | 衣 | 得 | 我。 | [tə + R] |

| na55 | tɕ’ian33 | i45 | tə | ŋo42 | |

| take | clf | clothes | dat | 1sg | |

| ‘Give me a shirt.’ | |||||

| (35) | 橘子 | 把得 | 他 | 哒。 | [pa42tə + R] |

| tɕy55tsɿ | pa42tə | la33 | ta | ||

| clementine | give | 3sg | crs | ||

| ‘(Someone) gave the clementine to him.’ | |||||

| (36) | 借 | 本 | 书 | 把 | 我。 | [pa42 + R] |

| tɕia324 | pən42 | ɕy45 | pa42 | ŋo42 | ||

| lend | clf | book | dat | 1sg | ||

| ‘Lend a book to me.’ | ||||||

Changsha, Cenchuan, and Pingjiang probably share this pathway for their dative marker 把 BA, based on the geographic location of the languages and possible development.

4.2.2. Relexicalization

In this pathway, the TAKE verb gained a GIVE meaning through relexicalization. Güldemann (2012) discussed the polysemy of a ‘take/give’ verb in Tuu languages spoken in southern Africa. See two examples from Taa (Güldemann 2012, p. 73) with the verb /uM~!ãM (regularly followed by the dative preposition n/aM)8.

| (37) Taa (Tuu languages; southern Africa) | ||||

| Si | /oe | si n//au | /’ang | ʘuru |

| 1p.e | hold.s:3> | problem.3 | com:1s | offspring.p |

| ‘We get/have problems with my children.’ | ||||

| (38) | suu | si | /ui | tuu |

| feed.first.time | ipfv | ?GIVE~TO:1> | people.1 | |

| ‘Purifying the people’ [lit.: feed to the people] | ||||

He proposed that the ‘obtainment-possession’ meaning is the original one, and the ‘give’ reading of the ‘take’ verb is triggered by its recurrent use in the ditransitive construction with a dative element. In other words, it is induced by a syntactically coerced semantic re-analysis.

Newman (1996, pp. 50–60) also demonstrated that TAKE and GIVE verbs are semantically close from a cognitive perspective: the participants (i.e., Giver, Theme, Recipient) for TAKE and GIVE remain the same within the same spatio-temporal domain.

From TAKE to GIVE has been reported in Sinitic languages, such as Shaowu (Ngai 2015, 2021), and Hengyang (Yang and Peng 2021). Take Hengyang, for example. te22 得 can be used as a verb of GET or GIVE, dative marker, causative verb, and passive marker.

| (39) Hengyang (Xiang; Peng 2005, pp. 143–45) | ||||||||

| 我 | 得 | 哒 | 一 | 百 | 块 | 钱 | 奖。 | (GET) |

| ŋo33 | te22 | ta22 | i22 | pe22 | k’uai33 | tɕien11 | tɕian33 | |

| 1sg | get | pfv | one | hundred | currency.unit | money | prize | |

| ‘I won a prize of one hundred yuan.’ | ||||||||

| (40) | 冇 | 得 | 一 | 分 | 钱 | 得 | 我。 | (GIVE and Dative) |

| mau213 | te22 | i22 | fən45 | tɕien11 | te22 | ŋo33 | ||

| neg | give | one | currency.unit | money | dat | 1sg | ||

| ‘(Someone) didn’t give me a penny.’ | ||||||||

| (41) | 你 | 就 | 得 | 其 | 骂 | 也 | 冇得 | 关系 | 唦。 | (Causative) |

| ni33 | tɕiu213 | te22 | tɕi33 | ma213 | ia33 | mau213te22 | kuen45·ɕi | sa11 | ||

| 2sg | just | let | 3sg | scold | also | not.have | affect | sfp | ||

| ‘It is fine to just let him scold you.’ | ||||||||||

| (42) | 我 | 走 | 箇 | 来 | 冇 | 两 | 天 | 就 | 得 | 你 |

| ŋo33 | tsəu33 | ko33 | lai11 | mau213 | lian33 | t’ien45 | tɕiu213 | te22 | ni33 | |

| 1sg | walk | here | come | neg | two | day | then | pass | 2sg | |

| 骂 | 一 | 顿, | 我 | 还 | 不 | 如 | 不 | 来。 | ||

| ma33 | i22 | tən24 | ŋo33 | xai11 | pu22 | ɕy11 | pu22 | lai11 | ||

| scold | one | vcl | 1sg | rather | neg | as | neg | come | ||

| ‘I haven’t even been here two days and you’ve scolded me. I might as well not have come.’ | ||||||||||

| (Passive) | ||||||||||

Since there is no compound form mentioned in Hengyang from the literature, it is less likely that te22 develops a dative use through a compound GIVE verb, and the object marker in Hengyang is another verb of taking (i.e., lau45 㧯), which means te22 is more likely to turn into GIVE before developing an object marking use based on TAKE. We consider that te22 first became a genuine GIVE verb then developed the dative use from GIVE. Most languages that share this pathway use DE 得 as their GIVE verb.

4.3. BEN > DAT

Zhang (2011) mentioned that in some Sinitic languages spoken in Hunan and Hubei, instead of using the postverbal dative construction that commonly used in Southern Sinitic languages, they tend to use preverbal dative construction to express transfer. Huang (2021) investigated the sources for the preverbal dative markers in Sinitic languages, and she indicates that a common developmental chain for Southern Sinitic languages is: Comitative > Benefactive > Dative. From Map 96 of Linguistic Atlas of Chinese Dialects (Grammar Volume) (Cao 2008), we can also observe this tendency.

In our data, the Type V languages: Fenghuang, Jishou, Waxiang, Tasha, and Changde all share this pathway. Take Waxiang, for example.

| (43) Waxiang (Unclassified; Chappell et al. 2011) | |||||||

| 是 | □ | 跟 | 我 | 担 | 的 | 水。 | (Benefactive) |

| tshɛ25 | zɤ13 | kai55 | u25 | toŋ55 | ti | tsu25 | |

| be | 3sg | ben | 1sg | carry | sp | water | |

| ‘He’s the one who carried the water for me.’ | |||||||

| (44) | □ | 跟 | 我 | 得 | 件 | 衣。 | (Dative) |

| zɤ13 | kai55 | u25 | tɤ55 | tɕhia41 | i55 | ||

| 3sg | dat | 1sg | give | clf | clothes | ||

| ‘He gave me a shirt.’ | |||||||

Preverbal dative constructions are very commonly used in the northwest of China, as shown in Map 96, such as in Lanzhou, Xining. There is a famous linguistic area in the northwest China, i.e., ‘Qinghai-Gansu Sprachbund’, and the Sinitic languages in this region have been influenced by Mongolian, Turkic, and other non-Han languages with SOV word order; as a result, some of the varieties of Sinitic languages have also shifted to SOV order and have even developed case markers (Xu 2015). Preverbal adpositional phrase is in harmony with OV word order (Dryer 1992). The use of preverbal dative construction in this region is reasonable. Zhang (2011) also tried to explain the similar situation in Hunan and Hubei by language contact, he indicated that these Sinitic languages with preverbal dative constructions are probably influenced historically by a Tibeto-Birman language with OV order, i.e., Tujia. It is possible that there existed a substratum of Tujia in Hunan, Hubei, and Guizhou. The Tujia people have lived in this area throughout many centuries, and many of the historical and cultural customs of the Tujia people have spread to the neighboring Han Chinese communities, but this remains to be proved by subsequent research.

4.4. Areal Distribution According to the Diachronic Developments

We can make three observations from the data. First of all, looking at the various types of patterns, we can note two different directions of development. From north to south, Type I languages can develop into Type II languages, and the dative markers of Type II languages are formed by the loss of allative element on the basis of a compound GIVE verb: [TAKE-ALL]. This process can actually be observed in Yueyang, as shown in Section 4.2.1. On the basis of Type II, the GIVE<TAKE can further develop into a genuine GIVE verb which may subsequently develop into a passive marker, as the case of some Type III languages, such as in Yiyang (Shi and Wang 2009) and Longhui (Ding 2006, p. 84), a compound dative form ba13te55 把得 is reported. From the south to the north, the GIVE<TAKE verbs of Type IV languages are directly transformed into genuine GIVE verbs through relexicalization, and further develop the dative and passive use. We note that most of the GIVE verbs in these languages are DE 得, only Suining uses pa55 把. Type IV languages may also develop further into Type III languages in the north, having object marker grammaticalized from the GIVE verb through the intermediate stage of benefactive. It might be the case that for Changning, the GIVE verb te33 得 is attested as a dative marker, a passive marker, a benefactive marker, and an object marker.

Another interesting phenomenon that we can observe is about the GIVE<TAKE verb BA 把 is that from north to south, from the syntactic perspective, the TAKE use of BA is gradually weakened, while the GIVE use is gradually strengthened. For example, in Type I languages, e.g., Huarong, pa21 把 can only be followed by the T argument, which has neither dative nor passive use, and the genuine GIVE verb is pa21tɛ33 把得, whereas in Type IV languages, e.g., Suining, pa55 把 is more like a GIVE verb, as it can act as both a dative and a passive marker, and the object marker is developed from another TAKE verb tan55 担.

Finally, we can find that DE 得 as a dative marker actually involves two different evolutionary pathways; one is represented by Type I languages, where the dative use is based on the allative use, and the other is represented by Type III languages, where the dative use is derived from DE being a genuine GIVE verb.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we investigated the dative markers of 30 Sinitic languages in the Hunan Province, including 14 Xiang varieties, five Gan varieties, seven SWM varieties, one Hakka variety, two Tuhua varieties, and one unclassified Sinitic language in the Hunan Province. Five patterns have been observed, and the patterns show a regular distribution according to their geographic locations instead of the affiliations. We also identified three main grammaticalization pathways behind the patterns. See Table 3 for the summary of the pathways behind each type of pattern.

Table 3.

The types and developments of dative markers in Hunan.

For the Type II, III, and IV languages, the dative markers have the same form as their GIVE<TAKE verbs, but it concerns two different grammaticalization pathways. One is that the original TAKE verb combines with an allative element and this compound form becomes a genuine GIVE verb, which can become a dative marker to introduce the R argument, then the allative dropped from the compound form and left the original TAKE verb as a dative marker. The second pathway is that the TAKE verb first became a genuine GIVE verb through relexicalization, then the dative use was developed from the genuine GIVE verb. Type III languages may involve these two different pathways.

We can see that the most used dative marker is DE 得 (attested in seven languages) and BA 把 (found in nine languages). The dative use of DE in northern Hunan is developed from its allative use, while in southern Hunan, DE grammaticalized into dative marker from the GIVE verb use. BA as a GIVE verb is widely spread in Hunan, but in northern Hunan, BA only gained the semantic meaning of giving and cannot be really considered as a GIVE verb which can take an R argument; however, in the south, the GIVE use of BA becomes mature: it can not only be used as a dative marker to introduce the recipient, but also develops a passive use. We claim that in the Hunan Province, from north to south, BA is gradually shifting from TAKE to GIVE.

Finally, we remarked on a pattern that might be induced by language contact from Tujia, i.e., in northwestern Hunan; different from other Sinitic languages spoken in Hunan, four languages in our data tend to use a preverbal dative construction to encode transfer, and the source for the dative marker is the benefactive marker.

Hunan has been regarded as a transitional zone in Chappell (2015) by three constructions: differential object marking, passive, and comparative constructions. How to refine the linguistic areas there relies on other features. Our examination of the distribution and origin of patterns with dative markers helps the further finer classification of the Sinitic languages in Hunan, as well as to probe the historical layers and developments for those languages. In addition, double object constructions as well as GIVE verbs have long been important in the research for linguistic geography, e.g., (Hashimoto 1976; Szeto 2019). However, the literature has not explored much the development of the dative markers. We hope this paper will be an important addition to the exploration of dative marking patterns by combining dative markers with GIVE verbs, allative markers, passive markers, and differential object markers.

Further extensive inquiry and investigation into the patterns of dative markers will undoubtedly serve to rigorously test and refine the grammaticalization chains outlined in our analysis, not only for other Sinitic languages and regions but also for broader linguistic contexts.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

A part of the data for this research was collected during my short-term fellowship in the SFB 1287 Limits of Variability in Language: Cognitive, Computational and Grammatical Aspects at Potsdam University while doing a collaborative study on the word orders of the oblique arguments in Hunan Sinitic languages with Andreas Hölzl, whom I thank for his great support and productive exchange. I would also like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisor Professor Hilary Chappell for her invaluable help and guidance throughout the research.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| 1 | First person |

| 2 | Second person |

| 3 | Third person |

| ALL | Allative |

| BEN | Benefactive |

| CLF | Classifier |

| COM | Comitative |

| CRS | Currently relevant state |

| DAT | Dative |

| E | Exclusive |

| EXP | Experiencer marker |

| IPFV | Imperfective |

| LOC | Locative |

| NEG | Negation |

| OM | Object marker |

| P | Plural |

| PASS | Passive |

| PFV | Perfective |

| POSS | Possessive |

| PROG | Progressive |

| S | Singular |

| SFP | Sentence final particle |

| SG | Singular |

| SP | Structural particle |

| VCL | Verbal classifier |

| Arabic number | Agreement class |

Notes

| 1 | The Tuhua of shouthern Hunan (or ‘Xiāngnán tǔhuà 湘南土话’ in Chinese) is mainly found in the Chenzhou 郴州 and Yongzhou 永州 regions. It is very different from both the neighboring Xiang and Mandarin varieties, and its affiliation is still controversial. It is categorized in the Language Atlas of China (Institute of Linguistics, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences 2012, p. 3) with Pinghua 平话 as one of the ten major groups of Sinitic languages. Refer to the Language Atlas of China (Institute of Linguistics, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences 2012) for more information on the Sinitic languages and their classification. |

| 2 | Usually, there is more than one type of ditransitive construction in a language, and the ‘main ditransitive construction’ here refers to the most commonly used, or the least restricted one. For instance, in Ningyuan, as can be seen in the examples (8) and (9) mentioned later, the construction with a postverbal dative marker kə45 is more commonly used, while the construction with a preverbal dative marker xo21 is only found with verbs denoting a mental transfer, such as ‘tell’. In this case, kə45 is the marker that we deal with in this paper. |

| 3 | In this paper, we use the definition in Zhang (2011) for Southern and Northern Sinitic languages: Southern Sinitic languages refer to the languages of eastern and southern China, the ‘Southern Mandarin’varieties (i.e., Jiang-Huai Mandarin and Southwestern Mandarin), and the Tuhua (or Pinghua) of the southern regions of China whose affiliation is not yet clear; Northern Sinitic languages refer to the Mandarin (other than Jiang-huai Mandarin and Southwestern Mandarin) and Jin varieties. |

| 4 | Zhang (2011) uses the terminology Jiè bīn bǔyǔ shì shuāng jí wù jiégòu 介宾补语式双及物结构 in Chinese to indicate this type of ditransitive construction, but it is difficult to find an appropriate English term to translate it. Considering the dative prepositional phrase appears postverbally, and it is the dative marker or the dative phrase that is of interest in this paper, we opt for using postverbal dative construction to refer to it. For similar reason, preverbal dative construction is used to refer to Jiè bīn zhuàngyǔ shì shuāng jí wù jiégòu 介宾状语式双及物结构 in Min Zhang (2011). |

| 5 | In this paper, TAKE verbs represent those verbs meaning ‘to take’, ‘to grasp’, ‘to get’, and they are monotransitive in nature. |

| 6 | Note that in Huarong, the inverted double-object construction [pa42 + T + R] exists, and it may seem that the pa42 can also take two arguments. However, if pa42 has to take an R argument, a compound form 把得 pa42tə is used. |

| 7 | The symble □ is used for any syllable of uncertain etymological source. |

| 8 | The lexeme is sensitive to the number of its object by means of stem suppletion; hence, it has two forms. In addition, as a transitive verb, it has to agree with the first nominal of its object pharse or incorporte the object pronoun (depending on that element, /uM can change to /oM). |

References

- Bao, Houxing 鲍厚星, and Yongming Li 李永明. 1985. Húnánshěng Hànyǔ dìtú sān fú 湖南省汉语地图三幅 [Three Chinese dialect maps of Hunan province]. Fangyan 4: 273–76. [Google Scholar]

- Bei, Xianming 贝先明, and Ning Xiang 向柠. 2009. Liúyáng fāngyán de jiècí 浏阳方言的介词 [The prepositions in Liuyang dialect]. In Húnán fāngyán de jiècí 湖南方言的介词 [Coverbs in the Hunan Dialects]. Changsha: Hunan Shifan Daxue Chubanshe 湖南师范大学出版社 [Publishing House of Hunan Normal University], pp. 46–59. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Zhiyun 曹志耘, ed. 2008. Hànyǔ fāngyán dìtú jí·yǔfǎ juàn 汉语方言地图集·语 [Linguistic Atlas of Chinese Dialects (Grammar)]. Beijing: The Commercial Press 商务印书馆. ISBN 978-7-100-05785-1. [Google Scholar]

- Chao, Yuan-Ren 赵元任. 1968. A Grammar of Spoken Chinese. Berkeley et Los Angeles: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chappell, H., and A. Peyraube. 2006. The Analytic Causatives of Early Modern Southern Min in Diachronic Perspective. Beijing: The Commercial Press 商务印书馆. [Google Scholar]

- Chappell, H., A. Peyraube, and Y. Wu. 2011. A comitative source for object markers in Sinitic languages: 跟kai55 in Waxiang and 共kang7 in Southern Min. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 20: 291–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chappell, Hilary 曹茜蕾. 2007. Hànyǔ fāngyán de chǔzhì biāojì de lèixíng汉语方言的处置标记的类型 [Typology of Object Marking Constructions: A Pan-Sinitic View]. Yǔyán xué lùn cóng语言学论丛 36: 184–209. [Google Scholar]

- Chappell, Hilary. 2015. Linguistic areas in China for differential object marking, passive, and comparative constructions. In Diversity in Sinitic Languages. Edited by Hilary M. Chappell. Oxford: Oxford Academic. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Hui 陈晖. 2009. Lián yuán qiáotóuhé fāngyán de jiècí 涟源桥头河方言的介词 [The Prepositions in Lianyuan Qiaotouhe Dialect]. In Húnán fāngyán de jiècí 湖南方言的 介词 [Coverbs in the Hunan Dialects]. Changsha: Hunan Shifan Daxue Chubanshe 湖南师范大学出版社 [Publishing House of Hunan Normal University], pp. 200–12. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Hui 陈晖. 2002. Liányuán (Qiáotóuhé) fāngyán de bèidòng biāojì 涟源(桥头河)方言的被动标记 [The passive markers of Lianyuan (Qiaotouhe) Dialect] [Conference paper]. Paper presented at Guójì hànyǔ fāngyán yǔfǎ xuéshù yántǎohuì 国际汉语方言语法学术研讨会 [International Symposium on Chinese Dialcet Grammar], Ha’erbin, China, December 26–29. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, Andy C. 錢志安. 2010. Two types of indirect object markers in Chinese: Their typological significance and development. Journal of Chinese Linguistics 38: 1–25. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23753879 (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- Chin, Andy Chi-on. 2011. Grammaticalization of the Cantonese Double Object Verb [pei35] 畀 in Typological and Areal Perspectives. Language and Linguistics 語言暨語言學 12: 529–63. [Google Scholar]

- Crystal, David. 2003. A Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics, 5th ed. Malden: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Zhenhua 崔振华. 2009. Yìyáng fāngyán de jiècí 益阳方言的介词 [The Prepositions in Yiyang Dialect]. In Húnán fāngyán de jiècí 湖南方言的介词 [Coverbs in the Hunan Dialects]. Changsha: Hunan Shifan Daxue Chubanshe 湖南师范大学出版社 [Publishing House of Hunan Normal University], pp. 156–68. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Yonghong 邓永红. 2009. Guìyáng Tǔhuà fāngyán de jiècí 桂阳土话的介词 [The prepositions in Guiyang Tuhua]. In Húnán āngyán de jiècí 湖南方言的介词 [Coverbs in the Hunan dialects]. Changsha: Hunan Shifan Daxue Chubanshe 湖南师范大学出版社 [Publishing House of Hunan Normal University], pp. 70–84. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Jiayong 丁家勇. 2006. Xiāng fāngyán dòngcí jù shì de pèi jià yánjiū—Yǐ lóng huí fāngyán wéi lì湘方言动词句式的配价研究—以隆回方言为例 [A study on the Valency of Verbal Clauses in Xiang Dialect—A Case Study of Longhui Dialect]. Changsha: Hunan Shifan Daxue Chubanshe 湖南师范大学出版社 [Publishing House of Hunan Normal University]. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Jiayong 丁家勇. 2009. Lónghuí fāngyán de jiècí 隆回方言的介词 [The prepositions in Longhui dialect]. In Húnán fāngyán de jiècí 湖南方言的介词 [Coverbs in the Hunan Dialects]. Changsha: Hunan Shifan Daxue Chubanshe 湖南师范大学出版社 [Publishing House of Hunan Normal University], pp. 213–30. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Zhengyi 董正宜. 2009. Yōuxiàn fāngyán de jiècí 攸县方言的介词 [The prepositions in Youxian dialect]. In Húnán āngyán de jiècí 湖南方言的介词 [Coverbs in the Hunan Dialects]. Changsha: Hunan Shifan Daxue Chubanshe 湖南师范大学出版社 [Publishing House of Hunan Normal University], pp. 34–45. [Google Scholar]

- Dryer, Matthew S. 1992. The Greenbergian Word Order Correlations. Language 68: 81–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Pingquan 方平权. 1999. Yuèyáng fāngyán yánjiū 岳阳方言研究 [Research on Yueyang dialect]. Changsha: Hunan Shifan Daxue Chubanshe 湖南师范大学出版社 [Hunan Normal University Press]. [Google Scholar]

- Güldemann, Tom. 2012. Relexicalization within grammatical constructions. In Grammaticalization and (Inter-) Subjectification. Edited by Johan van der Auwera and Jan Nuyts. Brussels: Koninklijke Vlaamse Academie van Belgie voor Wetenschappen en Kunsten, pp. 65–80. [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto, Mantaro. 1976. Language diffusion on the Asian continent: Problems of typological diversity in Sino-Tibetan. Computational Analyses of Asian and African Languages 3: 49–65. [Google Scholar]

- Haspelmath, Martin. 2016. The serial verb construction: Comparative concept and cross-linguistic generalizations. Language and Linguistics 17: 291–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Xiaoxue 黄晓雪. 2021. Hànyǔ fāngyán yòng yú dòngcí qián de yǔ gé biāojì汉语方言用于动词前的与格标记 [Dative Markers Used Before Verbs in Chinese Dialects]. Yǔyán kēxué 语言科学 Language Sciences 20: 337–47. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Linguistics, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (Zhōngguó shèhuì kēxuéyuàn yǔyán yánjiū suǒ 中国社会科学院语言研究所). 2012. 中国语言地图集 (Zhongguo Yuyan Dituji [Language Atlas of China]), 2nd ed. Beijing: The Commercial Press 商务印书馆. [Google Scholar]

- Kuteva, Tania, Bernd Heine, Bo Hong, Haiping Long, Heiko Narrog, and Seongha Rhee. 2019. World Lexicon of Grammaticalizations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, Huei-ling. 2001. On Hakka BUN: A case of polygrammaticalization. Language and Linguistics 2: 137–53. [Google Scholar]

- Lamarre, Christine 柯理思. 2009. Lùn běifāng fāngyán zhōng wèiyí zhōngdiǎn biāojì de yǔfǎ huà hé jù wèi yì de zuòyòng 论北方方言中位移终点标记的语法化和句位义的作用 [The grammaticalization of goal markers in Northern Mandarin and the syntactic position of locative phrases]. In Yǔfǎ huà yǔ yǔfǎ yánjiū 语法化与语法研究 [Research on Grammaticalization and Grammar]. Beijing: Commercial Press. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Guohua 李国华. 2009. Shàoyáng fāngyán de jiècí 邵阳方言的介词 [The prepositions in Shaoyang dialect]. In Húnán fāngyán de jiècí 湖南方言的介词 [Coverbs in the Hunan Dialects]. Changsha: Hunan Shifan Daxue Chubanshe 湖南师范大学出版社 [Publishing House of Hunan Normal University], pp. 271–79. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Qiqun 李启群. 2002. Jíshǒu fāngyán yánjiū 吉首方言研究 [Research on Jishou Dialect]. Beijing: Publishing House of Minority Nationalities 民族出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Qiqun 李启群. 2009. Fènghuáng fāngyán de jiècí 凤凰方言的介词 [The prepositions in Fenghuang dialect]. In Húnán fāngyán de jiècí 湖南方言的介词 [Coverbs in the Hunan Dialects]. Changsha: Hunan Shifan Daxue Chubanshe 湖南师范大学出版社 [Publishing House of Hunan Normal University], pp. 295–308. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Xuping, and Yicheng Wu. 2015. Ditransitives in three Gan dialects: Valence-increasing and preposition incorporation. Language Sciences 50: 66–77. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S038800011500025X (accessed on 10 October 2022). [CrossRef]

- Li, Yongming 李永明. 2016. Línxiāng Fāngyán 临湘方言 [Linxiang Dialect]. Xiangtan: Xiāngtán dàxué chūbǎnshè 湘潭大学出版社 [Xiangtan University Publishing House]. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Wen, and Pui Yiu Szeto. 2023. Polyfunctionality of ‘Give’ in Hui Varieties of Chinese: A Typological and Areal Perspective. Languages 8: 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Xinru 罗昕如, and Lei Zou 邹蕾. 2009. Xīnhuà fāngyán de jiècí 新化方言的介词 [The prepositions in Xinhua dialect]. In Húnán fāngyán de jiècí 湖南方言的介词 [Coverbs in the Hunan Dialects]. Changsha: Hunan Shifan Daxue Chubanshe 湖南师范大学出版社 [Publishing House of Hunan Normal University], pp. 184–99. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Hui 马慧. 2003. Táng yǐqián ‘dé’ zì jī xiāngguān ‘dé’ zìjù dé yǎnbiàn yánjiū唐以前“得”字机相关“得”字句得演变研究 [The Research for the Evolution of ‘De’ and Relevant ‘De’ Sentences before Tang Dynasty]. Master’s dissertation, Hunan Normal University, Changsha, China. [Google Scholar]

- Malchukov, Andrej, Martin Haspelmath, and Bernard Comrie, eds. 2010. A Comparative Handbook. Berlin and New York: De Gruyter Mouton. ISBN 9783110220377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Bingsheng 毛秉生. 2009. Héngshān fāngyán (Qiánshān huà) de jiècí 衡山方言(前山话)的介词 [The prepositions in Hengshan (Qianshan) dialect]. In Húnán fāngyán de jiècí 湖南方言的介词 [Coverbs in the Hunan Dialects]. Changsha: Hunan Shifan Daxue Chubanshe 湖南师范大学出版社 [Publishing House of Hunan Normal University], pp. 259–70. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, Wenjing 毛文静. 2022. Lùn hànyǔ fāngyán jǐyǔ dòngcí ‘bǎ’ de chǎnshēng论汉语方言给予动词‘把’的产生 [On the Emergence of the Verb ‘Ba’ Denoting ‘Give’ in Chinese Dialects]. Hanyu Xuebao 汉语学报 Chinese Linguistics 1: 67–79. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, John. 1996. Give: A Cognitive Linguistic Study [Cognitive Linguistics Research 7]. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Ngai, Sing Sing. 2015. Giving is receiving: The polysemy of the GET/GIVE verb [tie53] in Shaowu. In Causation, Permission, and Transfer: Argument Realisation in GET, TAKE, PUT, GIVE and LET Verbs. Studies in Language Companion Series; Edited by Brian Nolan, Gudrun Rawoens and Elke Diedrichsen. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 167, 253–69. [Google Scholar]

- Ngai, Sing Sing. 2021. A Grammar of Shaowu: A Sinitic Language of Northwestern Fujian. Publication Title: A Grammar of Shaowu. De Gruyter Mouton, September. Available online: https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/9781501512483/html (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- Peng, Daxingwang. 2022. Le Dialecte de Cenchuan à Pingjiang [The Dialect of Cenchuan in Pingjiang]. Ph.D. thesis, INALCO, Paris, France. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Fengshu 彭逢澍. 2009. Lóudǐ fāngyán de jiècí 娄底方言的介词 [The prepositions in Loudi dialect]. In Húnán fāngyán de jiècí 湖南方言的介词 [Coverbs in the Hunan Dialects]. Changsha: Hunan Shifan Daxue Chubanshe 湖南师范大学出版社 [Publishing House of Hunan Normal University], pp. 169–83. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Yulan 彭玉兰. 2005. Héngyáng fāngyán yǔfǎ yánjiū 衡阳方言语法研究 [Research on the Grammar of Hengyang Dialect]. Beijing: China Social Sciences Press. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Yulan 彭玉兰. 2009. Héngyáng fāngyán de jiècí 衡阳方言的介词 [The Prepositions in Hengyang Dialect]. In Húnán fāngyán de jiècí 湖南方言的介词 [Coverbs in the Hunan Dialects]. Changsha: Hunan Shifan Daxue Chubanshe 湖南师范大学出版社 [Publishing House of Hunan Normal University], pp. 240–58. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, Nairong 钱乃荣. 1997. Shànghǎi huà yǔfǎ 上海话语法 [Grammar of Shanghainese]. Shanghai: Shanghai People’s Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rice, Sally, and Kaori Kabata. 2007. Crosslinguistic grammaticalization paterns of the ALLATIVE. Linguistic Typology 11: 451–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Yuzhi 石毓智, and Tongshang Wang 王统尚. 2009. 方言中处置式和被动式拥有共同标记的原因 [The Common Markers of Disposal and Passive Constructions in Chinese Dialects]. Hanyu Xuebao 汉语学报 [Chinese Languistics] 2: 43–53. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Yelin 孙叶林. 2009. Shàodōng fāngyán yǔfǎ yánjiū 邵东方言语法研究 [Research on the Grammar of Shaodong Dialect. Guangzhou: Huacheng Chubanshe 花城出版社 [Flower City Publishing House]. [Google Scholar]

- Szeto, Piu Yiu. 2019. Typological Variation Across Sinitic Languages. Ph.D. thesis, University of Hongkong, Hongkong. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Fang 王芳. 2009. Xiāngxiāng fāngyán de jiècí 湘乡方言的介词 [The prepositions in Xiangxiang dialect]. In Húnán fāngyán de jiècí 湖南方言的介词 [Coverbs in the Hunan Dialects]. Changsha: Hunan Shifan Daxue Chubanshe 湖南师范大学出版社 [Publishing House of Hunan Normal University], pp. 231–39. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Zhongxing 王众兴. 2009. Píngjiāng Chéngguān fāngyán de jiècí 平江城关方言的介词 [The prepositions in Pingjiang Chengguan dialect]. In Húnán fāngyán de jiècí 湖南方言的介词 [Coverbs in the Hunan Dialects]. Changsha: Hunan Shifan Daxue Chubanshe 湖南师范大学出版社 [Publishing House of Hunan Normal University], pp. 24–33. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Qizhu 吴启主. 2009. Chángníng fāngyán de jiècí 常宁方言的介词 [The Prepositions in Changning Dialect]. In Húnán fāngyán de jiècí 湖南方言的介词 [Coverbs in the Hunan Dialects]. Changsha: Hunan Shifan Daxue Chubanshe 湖南师范大学出版社 [Publishing House of Hunan Normal University], pp. 12–23. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Yunji. 2001. The Development of Locative Markers in the Changsha Xiang Dialect. In Sinitic Grammar: Synchronic and Diachronic Perspectives. Edited by Hilary Chappell. Oxford: Oxford Academic. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Yunji 伍云姬. 2009. Húnán fāngyán de jiècí 湖南方言的介词 [Coverbs in the Hunan dialects]. Changsha: Hunan Shifan Daxue Chubanshe 湖南师范大学出版社 [Publishing House of Hunan Normal University]. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Yunji 伍云姬. 2011. A synchronic and diachronic study of the grammar of the Chinese Xiang dialects. In A Synchronic and Diachronic Study of the Grammar of the Chinese Xiang Dialects. Mouton: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Boduan 谢伯端. 2009. Chénxī fāngyán de jiècí 辰溪方言的介词 [The prepositions in Chenxi dialect]. In Húnán fāngyán de jiècí 湖南方言的介词 [Coverbs in the Hunan Dialects]. Changsha: Hunan Shifan Daxue Chubanshe 湖南师范大学出版社 [Publishing House of Hunan Normal University], pp. 131–43. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Qiyong 谢奇勇. 2009. Xīntián fāngyán de jiècí 新田方言的介词 [The prepositions in Xintian dialect]. In Húnán fāngyán de jiècí 湖南方言的介词 [Coverbs in the Hunan Dialects]. Changsha: Hunan Shifan Daxue Chubanshe 湖南师范大学出版社 [Publishing House of Hunan Normal University], pp. 115–30. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, Xiangdong 邢向东. 2000. Shénmù fāngyán de xūcí ‘dé’ 神木方言的虚词‘得’ [The grammatical word ‘de’ in Shenmu Dialect]. Yǔwén xué kān: Gāoděng jiàoyù bǎn 语文学刊: 高等教育版 2: 26–28. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, Xiangdong 邢向东. 2002. Shénmù fāngyán yánjiū 神木方言研究 [Research on Shenmu Dialect]. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju 中华书局. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Dan 徐丹. 1992. Běijīnghuà zhōng de yǔfǎ biāojì cí ‘gěi’ 北京话中的语法标记词‘给’ [The marker ‘gei’ in Pekinese]. Fangyan 方言 1: 54–60. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Dan 徐丹. 1994. Guānyú hànyǔ lǐ ‘dòngcí +x + dìdiǎn cí’ de jù xíng 关于汉语里‘动词+x+地点词’的句型 [About the Construction of ‘Verb+X+Location’ in Chinese]. Zhongguo Yuwen 中国语文 3: 180–85. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Dan. 2015. Sinitic languages of Northwest China: Where did their case marking come from? In Languages in Contact in Northwestern China. Edited by Guangshun Cao, Redouane Djamouri and Alain Peyraube. Paris: EHESS-CRLAO, pp. 217–44. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Fan 阳繁, and Zerun Peng 彭泽润. 2021. Húnán héngshān fāngyán ‘dé’ de duō gōngnéng yòngfǎ jí qí yǔfǎ huà湖南衡山方言‘得’的多功能用法及其语法化 [The Multifunctional Usage and Grammaticalization of Word ‘De’ in Hengshan Dialect of Hunan]. Journal of Tongren University 铜仁学院学报 23: 110–23. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, Shumian 叶述冕. 2020. Cóng lìshí yǎnbiàn kàn yǔyì dìtú móxíng zhōng de yǔyì yù——Yǐ gǔdài hànyǔ xūcí ‘yú’ wéi lì从历时演变看语义地图模型中的语义域——以古代汉语虚词‘于’为例 [Semantic domains in semantic maps: Diachrony of yi and yu]. Hànyǔ shǐ yǔ hàn zàng yǔ yánjiū 汉语史与汉藏语研究 1: 134–53. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, Yanpeng 叶雁鹏. 2023. Jiāngxī ān yuǎn (lóng bù) kèjiā huà de shuāng jí wù jiégòu江西安远(龙布)客家话的双及物结构 [The ditransitive constructions in Anyuan (Longbu) Hakka of Jiangxi]. Fangyan 方言 45: 196–202. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, Yaxin 易亚新. 2007. Chángdé fāngyán yǔfǎ yánjiū 常德方言语法研究 [Research on the Grammar of Changde Dialect]. Beijing: Xueyuan Chubanshe 学苑出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Yue-Hashimoto, Anne. 1993. Comparative Chinese Dialectal Grammar: Handbook for Investigators. Paris: EHESS-CRLAO. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Changhong 曾常红, and Jianjun Li 李建军. 2009. Suīníng fāngyán de jiècí 绥宁方言的介词 [The prepositions in Suining dialect]. In Húnán fāngyán de jiècí 湖南方言的介词 [Coverbs in the Hunan Dialects]. Changsha: Hunan Shifan Daxue Chubanshe 湖南师范大学出版社 [Publishing House of Hunan Normal University], pp. 60–69. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Xianfei 曾献飞. 2006. Rǔchéng fāngyán yánjiū 汝城方言研究 [Research on Rucheng Dialect]. Beijing: Zhōngguó Shèhuì kēxué Chūbǎnshè 中国社会科学出版社 [China Social Sciences Press]. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Min. 2011. Revisiting the alignment typology of ditransitive constructions in Chinese dialects. Bulletin of Chinese Linguistics 4: 87–259. Available online: https://brill.com/view/journals/bcl/4/2/article-p87_3.xml (accessed on 10 October 2022). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Xiaoqin 张小勤. 2009. Níngyuǎn fāngyán de jiècí 宁远方言的介词 [The prepositions in Ningyuan dialect]. In Húnán fāngyán de jiècí 湖南方言的介词 [Coverbs in the Hunan Dialects]. Changsha: Hunan Shifan Daxue Chubanshe 湖南师范大学出版社 [Publishing House of Hunan Normal University], pp. 97–114. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Qingjun 郑庆君. 1999. Chángdé Fāngyán Yánjiū 常德方言研究 [Research on Changde Dialect]. Changsha: 湖南教育出版社 [Hunan Education Publishing House]. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Dexi 朱德熙. 1979. Yǔ dòngcí ‘gěi’ xiāngguān de jùfǎ wèntí 与动词“给”相关的句法问题 [Syntactic problems associated with the verb ‘gěi’]. Fangyan 方言 2: 81–87. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Dexi 朱德熙. 2009. Yǔfǎ jiǎngyì 语法讲义 [Lecture Notes on Grammar]. Beijing: The Commercial Press 商务印书馆. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).