Abstract

In this paper, I address the directionality issue posed by conversion in English through an investigation of category mismatch under VP-ellipsis, a less-studied type of ellipsis mismatch. For example, certain nouns, such as graduateN and sneezeN, allow the ellipsis of the VP headed by their morphologically related verbal counterparts, graduateV and sneezeV, but not vice versa. I argue that this kind of directional asymmetry, which would be mysterious under a purely semantic identity approach to ellipsis, based on truth-conditional equivalence and mutual entailment, is accounted for in terms of the syntactic identity condition to the effect that the structure of an ellipsis site must be properly contained within the structure of its intended antecedent expression. I will then use this syntactic account of category-mismatched VP-ellipsis as a critical probe into the internal syntax of zero-related N-V pairs and show that both N→V and V→N word-based derivations, in addition to the root-based derivation, must be admitted to account for conversion in English. To the extent that my proposed analysis is on the right track, the kind of asymmetries observed in N-V conversion furnishes an excellent testing ground for an abstract syntactic derivation for these morphologically related word pairs.

1. Introduction

The purpose of this paper is to address the directionality issue posed by conversion in English through category-mismatched VP-ellipsis, a less-studied type of mismatch under ellipsis (Johnson 2001; Fu et al. 2001; Hardt 1993; Kehler 2002; Merchant 2013a; Nakamura 2013a).1

The starting point of this paper is a certain directional asymmetry under VP-ellipsis. For example, certain nouns, such as graduateN and sneezeN, may serve as an antecedent for VP-ellipsis headed by their morphologically related verbal counterparts, graduateV and sneezeV, but the latter cannot license the ellipsis of the NP headed by the former. I argue that this kind of directional asymmetry is best accounted for in terms of the syntactic identity condition imposed on zero-related N-V pairs to the effect that the syntactic structure of an antecedent expression must properly contain the syntactic structure of the ellipsis site (Merchant 2008, 2013a, 2013b).

Having established the validity of the syntactic identity condition in this empirical domain, I will then use the condition as a critical litmus test in the abstract syntactic derivation of zero-related N-V pairs to address the familiar directionality issue concerning those pairs. This issue is essentially which member of each zero-related pair is derived from the other (N→V or V→N) (see Marchand 1963, 1964; Kiparsky 1982a, 1982b; Arad 2003; Harley and Haugen 2007 and numerous works cited therein on this issue).

The present paper is structured as follows. In Section 2, I will review some representative data, concerning voice mismatch under VP-ellipsis, that support a syntactic identity condition on ellipsis (Merchant 2008, 2013a, 2013b) over a semantic identity condition based on mutual entailment or truth-conditional equivalence between the ellipsis site and its antecedent (Dalrymple et al. 1991; Hardt 1993; Merchant 2001). In Section 3, I will introduce a wide range of examples in English to illustrate a directional asymmetry under category-mismatched VP-ellipsis whereby one member of a zero-related N-V pair may serve as an antecedent for the ellipsis of the phrase headed by the other member but not vice versa. I will then develop an account of the directional asymmetry in question within the framework of distributed morphology (hereafter, DM) that aligns with the independently motivated syntactic identity condition in Section 2. Having established the necessity of syntactic identity in category-mismatched VP-ellipsis, in Section 4, I will use it as a critical probe into the abstract syntax underlying zero-related N-V pairs to address the directionality issue concerning those pairs. I will provide novel evidence to show that both derivational patterns, N→V and V→N, in addition to the root-based derivation (Arad 2003), must be admitted into grammar to properly account for the entire range of possible directional asymmetries exhibited by conversion in English. Section 5 is the conclusion.

2. Syntactic Identity Condition on Ellipsis: Voice Mismatch under VP-Ellipsis

The (im)possibility of various forms of mismatch between an ellipsis site and its antecedent expression has proven to be a critical litmus test for the proper identification of identity conditions on ellipsis. Broadly speaking, three lines of approach have been articulated in the theoretical literature to illuminate the nature of the relevant conditions, though the relevant approaches are by no means necessarily mutually exclusive.

The first line of approach, represented by works such as Dalrymple et al. (1991) and Hardt (1993) and Merchant (2001), among many others, focuses on tolerable elliptical mismatches as supporting semantic identity conditions on ellipsis. The second line of approach, espoused by various researchers, including Chung (2013), Chung et al. (1995), Sag (1976), Hankamer (1979), and Merchant (2008, 2013a, 2013b), is centered instead around intolerable elliptical mismatches to argue for some version of syntactic identity conditions on ellipsis. The third line of approach, exemplified by works by Kehler (2000, 2002) and Kertz (2008, 2010), argues that ellipsis licensing is best characterized at the level of the discourse or information structure instead of syntactic or semantic structures.

In this section, I will review some representative data, concerning voice-mismatched VP-ellipsis (Merchant 2008, 2013a, 2013b), that support the syntactic identity condition on ellipsis. I will keep this review to a minimum, for it is simply to set the stage for a detailed discussion, in Section 3, on the fine syntactic derivation underlying zero-related N-V pairs exhibiting a directional asymmetry under category-mismatched VP-ellipsis.

It is widely acknowledged in the literature (see Sag 1976; Dalrymple et al. 1991; Hardt 1993; Kehler 2000, 2002; Johnson 2001; Merchant 2008, 2013a, 2013b; Kertz 2008, 2010; Nakamura 2013b; Stockwell 2024, among many others) that in VP-ellipsis, a passive antecedent may license an active elliptical VP and vice versa. Prima facie, this very possibility of “voice mismatch” is problematic for any strict syntactic-identity-based approach to VP-ellipsis, for the voice specifications are different between the antecedent–elliptical VP pair in apparent violation of the syntactic identity condition.

Merchant (2008, 2013a, 2013b) argues, however, that upon closer examination, it is actually a semantic-identity-based approach that has difficulties accounting for the VP-level voice-mismatch phenomenon. To illustrate this argument, consider examples in (1–2).

Merchant (2008, 2013a, 2013b) observes that the contrast in grammaticality between (1) and (2) is problematic for a purely semantic identity condition based on mutual entailment. More specifically, his reasoning is that because passive and active VPs entail each other, the voice mismatch pattern shown in the pseudogapping examples should be just as grammatical as that in the VP-ellipsis examples, clearly a wrong result.

| (1) | VP-ellipsis: Voice mismatch acceptable | |

| a. | This problem was to have been looked into, but obviously nobody did. | |

| b. | The janitor must remove the trash whenever it is apparent that it should be. | |

| (Merchant 2008, p. 169) | ||

| (2) | Pseudogapping: Voice mismatch unacceptable | |

| a.* | Roses were brought by some, and others did lilies. | |

| b.* | Some brought roses, and lilies were by others. | |

| (Merchant 2008, p. 170) | ||

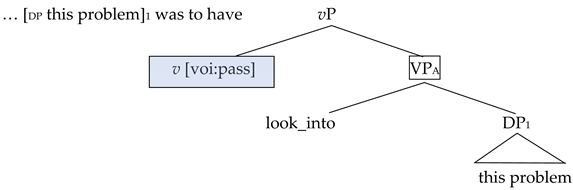

Merchant argues instead that the asymmetry between VP-ellipsis and pseudogapping with respect to voice mismatch is better explained through a syntactic identity condition if the latter targets a vP that contains a v-head specified for voice, whereas the former targets a smaller constituent, VP, to the exclusion of the v-head. To illustrate how this size-based syntactic analysis works, consider the relevant parts of the syntactic structures for the antecedent and elliptical VPs in (1a) and (2a), shown in (3a, b) and (4a, b), respectively. Here, VPA and VPE stand for the antecedent and elliptical VPs, and e stands for the [e]-feature, which is hypothesized by Merchant to license the ellipsis of its sister constituent under the condition of focus-assisted mutual entailment between VPA and VPE (see Merchant 2008, 2013a, 2013b for technical details on the nature and function of [e]-feature).

VPe in (3b) may undergo VP-ellipsis because it is syntactically identical to VPa in (3a). The syntactic identity condition is met here because the specified voice values borne by the v-heads are located outside the ellipsis site and the antecedent expression. VPe in (4b), by contrast, may not undergo pseudogapping, analyzed here as a case of vP-ellipsis preceded by overt focus movement of the remanent (Jayaseelan 1990; Lasnik 1995; Takahashi 2004; Gengel 2013), because the active voice feature value contained within the vPe clashes with the passive voice feature value contained within the vPa in (4a), violating the syntactic identity condition on ellipsis.

| (3) | a. |  |

| b. |  | |

| (adopted from Merchant 2008, pp. 171–72) | ||

| (4) | a. |  |

| b. |  | |

| (adopted from Merchant 2008, p. 175) | ||

In this way, the voice mismatch contrast exhibited in (1) vs. (2) receives a principled explanation in terms of syntactic identity once we take the size of the ellipsis site in the two elliptic constructions—VP in VP-ellipsis and vP in pseudogapping—into account.2 In the rest of this paper, I will assume this syntactic-identity-based approach to VP-ellipsis as my point of departure to explore the syntactic derivation and directionality of conversion.3

3. Category-Mismatched VP-Ellipsis: Directional Asymmetries and Syntactic Identity

Hardt (1993) was the first to observe that certain nouns can serve as an antecedent for the ellipsis of the VP headed by their morphologically related verbs. Some illustrative examples of this category-mismatched VP-ellipsis from Hardt (1993) and those culled from the literature are shown in (5–10). See also Kehler and Ward (1999), Johnson (2001), Kehler (2002), Tanaka (2011), Merchant (2013a), Nakamura (2013a), Miller and Hemforth (2014), Park and Choi (2019), and Kim (2020) for further examples of this type.

| (5) | People say that Harry is an excessive drinker at social gatherings. Which is strange, because he never does [VP …] at my parties. | |

| (Hardt 1993, p. 35) | ||

| (6) | Today, there is little or no OFFICIAL harassment of lesbians and gays by the national government, although autonomous governments might [VP …]. | |

| (Hardt 1993, p. 35) | ||

| (7) | We should suggest to her that she officially appoint us as a committee and invite faculty participation. They won’t [VP …], of course. | |

| (Hardt 1993, p. 35) | ||

| (8) | Mubarak’s survival is impossible to predict and, even if he does [VP …], his plan to make his son his heir apparent is now in serious jeopardy. | |

| (Miller and Hemforth 2014, p. 7) | ||

| (9) | Since they don’t have anyone to replace her, her resignation is in doubt. If she does [VP …], …. | |

| (Miller and Hemforth 2014, p. 7) | ||

| (10) | a.? | That man is a robber, and when he does [VP …], he tries not to make any noise. |

| b.* | That man is a thief, and when he does [VP …], he tries not to make any noise. | |

| (Merchant 2013a, p. 447) | ||

Merchant (2013a, p. 447) notes that the semantics of (10a) and (10b) are identical, yet only the latter ends up being an ungrammatical case of category-mismatched VP-ellipsis. He argues, based on this contrast, that syntactic identity, not semantic identity, plays a role in licensing VP-ellipsis, suggesting that the noun robber, but not the noun thief, includes a VP in its internal syntax and so this abstract VP licenses the ellipsis of the identical VP in the elliptical cause in (10a). I will come back to a detailed analysis of the contrast between (10a) and (10b) in Section 4.3. For now, it suffices to say that to the extent that Merchant’s suggestion of this contrast can be maintained, it lends further support to the general syntactic identity approach to VP-ellipsis, adopted in this paper as the most important heuristic assumption to explore the syntax of N-V conversion in English.

3.1. Directional Asymmetries under Conversion N-V Pairs and Syntactic Identity

Note that all the examples of category-mismatched VP-ellipsis given above exhibit a clear morphological sign of derivational direction. That is, the verbs contained at the ellipsis site are morphologically derived from the nouns in the antecedent clause by overt affixation (i.e., drink→drinker, harass→harassment, participate→participation, survive→survival, resign→resignation, rob→robber). For such cases, then, it seems uncontestable that deverbal nouns license the ellipsis of the VP headed by their verbal bases.

Significantly, situations are not clear when the category mismatch in question involves an N-V pair supposedly derived through conversion or zero derivation. One of my central findings in this paper is the presence of directional asymmetry in N-V conversion under VP-ellipsis, a pattern first pointed out in an unpublished manuscript by Tan (2018). Tan points out that configurations that yield grammatical instances of category-mismatched VP-ellipsis in the context of conversion are restricted to those where the antecedent clause contains the noun of a zero-related N-V pair, followed by the ellipsis of the VP headed by its verbal counterpart; the acceptability of configurations with their roles and positions reversed is mixed, ranging from marginality to complete unacceptability. Tan’s original examples, illustrating the relevant directionality asymmetry, are shown in (11). A few more examples supporting the same asymmetry, which involve several other N-V conversion pairs, are also given in (12–14).4

| (11) | a. | Allow us to treat you like a [N graduate] before you do [VP |

| b.?? | You must [V graduate] before we end up treating you like one [NP | |

| (Tan 2018: his (1)) | ||

| (12) | a. | I’ve been working on [N divorce] for so long. I hope I don’t [VP |

| b.? | Although some people have decided that they definitely [N divorce] their spouse, they have no clue how to file for one [NP | |

| (13) | a.? | I heard a loud [N sneeze] in the other room, and then I almost did [VP |

| b.*? | Someone [V sneezed] loudly, and then I heard another [N | |

| (14) | a. | The police quashed the [N protest] in Chicago before angry mobs in other cities attempted to [VP |

| b.?? | Lots of people were [V protesting]. The last time I saw one [NP |

It is clear that a strict semantic-identity-based approach, like the one based on logical equivalence or mutual entailment (Dalrymple et al. 1991; Hardt 1993; Merchant 2001), is doomed to failure in the face of the contrast in grammaticality between the (a) examples and the (b) examples in (11–14). To take (11a, b), for instance, because a graduate is someone who has graduated and received a university degree after having successfully completed a course of study or training, the antecedent and elliptical VPs headed by the noun and its verbal variant mutually entail each other. Accordingly, the semantic-identity-based approach wrongly predicts there to be no contrast between these two examples. Note further that a root-based identity approach to conversion (Arad 2003) is also difficult to maintain in those cases. Such an approach would say that the ellipsis of a VP is licensed as long as the root contained at the ellipsis site is identical to that contained within the structure-matching antecedent. It would then predict both (11a) and (11b) as being grammatical, a wrong result, for only the N→V pattern is actually grammatical.

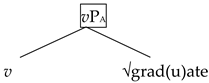

Why is there a directionality asymmetry of the kind illustrated in (11–14)? Adopting a word-based syntax of conversion/zero-derivation pioneered by Kiparsky (1982a, 1982b), as opposed to a root-based syntax (Arad 2003), I propose that the noun graduateN has a VP in its syntactic derivation, which properly contains the structure underlying the morphologically related verb graduateV. According to this analysis, the relevant parts of the antecedent and the ellipsis sites in (11a, b) are as shown in (15) and (16), respectively.

| (15) | category mismatch under conversion: graduateN→graduateV (grammatical, (11a)) | |||

| a. | Antecedent clause | b. | Elliptical clause | |

|  | |||

| (16) | category mismatch under conversion: graduateV→graduateN (ungrammatical, (11b)) | |||

| a. | Antecedent clause | b. | Elliptical clause | |

|  | |||

I assume, following the suggestion of an anonymous reviewer, that the word graduate in both its nominal and verbal use is composed of two bound roots—√grad(u) and √ate—given the presence of several other morphologically related words that share the same Latinate root grad(us) meaning ‘a step’, including gradual, gradually, graduation, graduand, grade, and gradation. For brevity’s sake, however, I simply notate this complex root under a single root node, as shown in (15) and (16). Here, I also follow the spirit of Lowenstamm’s (2015) proposal that derivational affixes in English are not spell-outs of the category-defining heads, as commonly assumed in the mainstream DM framework (Marantz 1997, 2001, 2007; Arad 2003; Marvin 2003), but are themselves roots whose category is instead determined by the nature of a higher categorizing functional head, such as v, n, and a. Thus, the roots √grad and √ate are merged to yield a complex root. The complex root, in turn, yields the verbal graduate and the nominal graduate, depending on whether it is merged with the verbalizing (v) or the nominalizing (n) head. In (15), the ellipsis of the vPe is licensed, as per the syntactic identity condition introduced in Section 2, because it has an identical vP in vPa in the antecedent. Such is not the case with (16), where the to be elided nPe has no syntactically identical constituent in the antecedent.

The present analysis of the directional asymmetry illustrated in (11–14) entails that nominals, such as graduateN, divorceN, sneezeN, and protestN, are deverbal not denominal. This particular result presents a novel type of evidence against deriving zero-related conversion pairs through the common root, but instead speaks in favor of a word-based syntactic derivation of such pairs, as originally envisaged in Kiparsky’s (1982a, 1982b) theory of conversion in Lexical Phonology (see Section 4.1 and Section 4.2 for a relevant discussion on Kiparsky’s theory as it pertains to the directionality of conversion).

It is important to complete my analysis of directional asymmetry by making sure that the (b) examples in (11–14) involve NP-ellipsis so that the asymmetry in question indeed holds true for conversion to begin with; otherwise, the examples may not involve any ellipsis, and hence the pairs in those cases do not constitute a genuine case of category-mismatched VP-ellipsis. Llombart-Huesca’s (2002) analysis of one-constructions provides independent evidence to show that the (b) examples do involve NP-ellipsis (see also Saab and Lipták 2015 for a DM-style analysis of NP-ellipsis as nP-ellipsis based on the possibility of number mismatch between antecedent–elliptical noun phases in Hungarian and Spanish). Llombart-Huesca argues that one-constructions in English, exemplified by sentences like I like that book better than this *(one), are derived through NP-deletion in the PF component, as schematically depicted in (17).

In this representation, one is inserted under Num as the last resort to give phonological support to the head, which would remain stranded if the deletion of the host NP on its right took place. Llombart-Huesca shows that this NP-ellipsis analysis is supported by the fact that the relevant construction permits strict/sloppy ambiguities, as shown in (18b), on par with bona fide cases of NP-ellipsis, such as the one in (18a), a standard diagnostic test for ellipsis (Sag 1976; Williams 1977).5

| (17) |  |

| (18) | a. | I saw Janet’s picture of her cat and Jack saw Julie’s. |

| strict reading: Jack saw Julie’s picture of Janet’s cat. | ||

| sloppy reading: Jack saw Julie’s picture of Julie’s cat | ||

| b. | I saw Janet’s beautiful picture of her cat, and Jack saw Julie’s ugly one. | |

| strict reading: Jack saw Julie’s ugly picture of Janet’s cat. | ||

| sloppy reading: Jack saw Julie’s ugly picture of Julie’s cat. | ||

| (Llombart-Huesca 2002, p. 60) |

As an anonymous reviewer points out, the availability of a sloppy interpretation is not a fool-proof test because overt pronominals are also known to give rise to such an interpretation in so-called paycheck contexts, as illustrated in the following celebrated example from Karttunen (1969):

| (19) | The mani who gave hisi paycheck to his wife is wiser than the manj who gave it (= hisj paycheck) to hisj mistress. |

| (Karttunen 1969, p. 114) |

It is important to note that the one-construction does not require such a special context to induce a sloppy interpretation, unlike the paycheck pronoun in (19). This observation thus supports the view that the construction in question involves NP-ellipsis. Furthermore, Elbourne (2001) argues that the definite pronoun in paycheck contexts is the definite article under D so that the relevant part of the underlying derivation for the pronoun is as shown in (20), where the complement of the D head subsequently undergoes NP-ellipsis:

| (20) | … the mani who gave [DP it [ |

To the extent that Elbourne’s analysis is right, the availability of the sloppy reading in (19), upon closer reflection, can actually be made consistent with the standard view that a sloppy interpretation diagnoses ellipsis.

3.2. Tying Up Some Loose Ends

In this section, I would like to address a number of questions concerning more precise details of my proposed analysis of the V→N conversion pair in (11–14), as pointed out to me by two anonymous reviewers.

The first question with my proposed analysis comes from its key assumption that the directional asymmetry discussed in this section is due to the noun being derived from a verbal base. At first sight, this assumption seems hard to sustain in the face of examples like (5–6), repeated here as (21–22), with the intended VP denotation filled in.

To take (21), for instance, the most natural reading of the elided VP is drink excessively. Under my syntactic approach, this means that the adjective excessive, modifying the derived nominal drinker within the NP, must start out as an adverb within the VP before the base structure is transformed to the NP via some “transformation” available in the contemporary syntactic/DM literature. Whatever transformation would relate the NP excessive drinker to the VP drink excessively in a way reminiscent of the generative semantics approach (Lees 1960) seems overly powerful and otherwise unmotivated elsewhere (Chomsky 1970). At the same time, however, the observation remains that VP-ellipsis in (21) does denote the VP drink excessively, indicating that the antecedent NP must somehow contain some suitable VP-like expression. A similar observation holds true for the example in (22), wherein the VP is the most naturally interpreted as denoting harass lesbians and gays. The question, thus, is how to resolve this conundrum.

| (21) | People say that Harry is an excessive drinker at social gatherings. Which is strange, because he never does [VP |

| (Hardt 1993, p. 35) | |

| (22) | Today, there is little or no OFFICIAL harassment of lesbians and gays by the national government, although autonomous governments might [VP |

| (Hardt 1993, p. 35) |

I propose that the antecedent NP excessive drinker has the syntactic structure, as shown in (23). In this structure, there is indeed the VP base, [VP drink excessively]. The V head drink undergoes head movement first into the root √er and then into the nominalizing n head to yield the derived nominal drinker (Recall that I am following Lowenstamm’s 2015 root theory of derivational affixes; see my previous discussion below (15–16)). Additionally, the structure simply has the adjective excessive within the nP portion dominating the VP without assuming any sort of adverb-to-adjective transformation.

Assuming this structure, it is clear how particular details within the abstract syntax of the antecedent nominal correctly feed into my current theory of ellipsis based on syntactic identity. The elided VPe means drink excessively because it has an identical antecedent in vPa. Indeed, there is an independent argument showing that expressions like excessive drinker have an underlying VP base. Clearly, the degree adjective excessive modifies some pre-nominalized form of drink because it modifies the drinking action, not the person (*He is an excessive person). Thus, the relevant NP has a structural mismatch, [[excessive-drink]-er].

| (23) |  |

This VP base analysis is further supported by the minimal pair shown in (24a, b).

Example (24a) is minimally different from (24b) in the choice of the pre-nominal modifiers: excessive and picky. The latter must describe the person’s character, not the drinking action. Indeed, the ellipsis site in (24b) cannot mean drink tequila in a picky manner, unlike in (24a), where the elided VP most naturally means drink tequila excessively. This minimal semantic contrast thus indicates that there is an abstract VP base underlying excessive drinker, as shown in (23).

| (24) | a. | People say that Harry is an excessive drinker of tequila at social gatherings. Which is strange, because he never does [VP |

| b. | People say that Harry is a picky drinker of tequila at social gatherings. Which is strange, because he never does [VP |

A similar argument for the VP base analysis can be made on the basis of other minimal pairs shown in (25a, b) and (26a, b).

As pointed out by Larson (1998), the NP a beautiful dancer in (25a) is ambiguous between a dancer who is beautiful (but may not be good at their craft) and someone who dances beautifully (but may not be physically attractive). Interestingly, the NP a beautiful ballerina in (25b) is unambiguous, giving rise to only the former reading ‘Olga is a ballerina and beautiful’, despite the fact that ballerina is intuitively related to the dancing action as much as dancer is.6 This contrast is naturally accounted for under the abstract VP base analysis. That is, the derivation of dancer involves the abstract VP base, where dance is modified by beautifully below the nP layer in the manner depicted in (23), whereas the derivation of ballerina does not have the VP base to support the manner adverb reading. The same analysis is supported by (26a, b). Example (26a) means either that Mike is a happy person or that Mike can sing happily, but (26b) lacks the reading that Mike sings happily as a member of a church choir. This contrast is analyzed as a straightforward consequence of my current analysis, whereby singer, not chorister, involves the nominalization of the abstract VP base.

| (25) | a. | Olga is a beautiful dancer. | |

| Intersective reading: Olga is a dancer, and she is beautiful. | |||

| Non-intersective reading: Olga dances beautifully. | |||

| b. | Olga is a beautiful ballerina. | ||

| Intersective reading: Olga is a ballerina, and she is beautiful. | |||

| * Non-intersective reading: Olga dances ballet beautifully. | |||

| ((25a) from Larson (1998, p. 145); (25b) from Winter and Zwarts 2019, p. 642) | |||

| (26) | a. | Mike is a happy singer. | |

| Intersective reading: Mike is a singer, and he is a happy person. | |||

| Non-intersective reading: Mike sings happily. | |||

| b. | Mike is a happy chorister. | ||

| Intersective reading: Mike is a singer in a church choir, and he is a happy person. | |||

| * Non-intersective reading: Mike sings happily as a member of a church choir. | |||

| (cf. Belk 2013) | |||

Note that the current analysis predicts that the nominals in (25a) and (26a), but not those in (25b) and (26b), should be able to antecede the ellipsis of the VP headed by the verb of the hidden VP in their syntactic derivation. Examples (27–28) show that this prediction is indeed borne out.

| (27) | a. | Olga is a beautiful dancer, so when she does, the audience is mesmerized by the adroitness of her movements. |

| b.* | Olga is a beautiful ballerina, so when she does, the audience is mesmerized by the adroitness of her movements. | |

| (28) | a. | Mike is a happy singer, and when he does, he is so adorable. |

| b.* | Mike is a happy chorister, and when he does, he is so adorable. |

The second question, related to the first question, is concerned with the relationship of the entity/result reading of deverbal nominals with VP-ellipsis. The noun graduateN has an entity/result reading (‘someone who has graduated’) but has no complex event nominal reading (Grimshaw 1990), unlike graduation. Given this fact, how does my proposed analysis ensure that this type of entity/result nominalization yields the antecedent vP to license VP-level ellipsis in the elliptical clause as required?

As stated in the paragraph directly below (16), it is reasonable to assume that the noun graduate is composed of the two bound roots √grad(u) and √ate. Note that, as pointed out by Harley (2009), the root √ate (the verbalizing functional head -ate for Harley) is among the candidates for overt v-morphemes in English, for the root form occurs with a variety of verb classes, including causative verbs, causative/inchoative alternation verbs, unaccusative verbs, and unergative verbs, as shown in (29a–d), respectively.

Under the assumption in the DM framework that “every piece of morphology must have a structural correlate” (Harley 2009, p. 342), the inclusion of the root form √ate in the noun graduate suggests itself as further indication that its syntax contains a hidden VP base.

| (29) | a. | causative verbs: |

| complicate, calculate, commemorate, pollinate, decorate, regulate, and disambiguate | ||

| b. | causative/inchoative alternation verbs: | |

| coagulate, activate, detonate, dilate, oscillate, correlate, levitate, and separate | ||

| c. | unaccusative verbs: | |

| capitulate, deteriorate, gravitate, and stagnate | ||

| d. | unergative verbs: | |

| dissertate, elaborate, ejaculate, commentate, hesitate, undulate, lactate, and vibrate | ||

| (Harley 2009, pp. 329–30) |

Returning, now, to the question above—how the entity/result reading is obtained through the vP structure that would otherwise give rise to the process reading, I follow Harley’s (2009) hypothesis that process nominals, inherently mass nouns, are coerced into being count nominals through their merger with a higher functional “packaging” head, such as Num and Cl(assifier), a process that concurrently results in the elimination of the original argument(s), if any. The intuition behind Harley’s hypothesis is that such a packaging head is used to delimit the event/entity, but the existence of any argument inherited from the verbal base, if any, blocks the head from delimiting it, for the same event/entity cannot be delimited twice in two different manners. Applied to the present case, this analysis correctly yields the result that the NP, a graduate, with an indefinite determiner—a morphosyntactic indication of the entity/result reading (Grimshaw 1990; see Lieber 2016, though, for some counterexamples to Grimshaw’s theory of complex/simplex/result nominals)—gives rise to the result reading despite having an abstract VP-level syntax. The relevant coercion process converting a mass process nominal to a count entity nominal is depicted in (30).

In this structure, the complex root, composed of √grad(u) and √ate, is first merged with the verbalizing functional head (v). The result is the process verb graduate, a verb, which thereby may license the ellipsis of the vP headed by graduateV, as shown in (11a). Subsequently, this vP is further merged with the nominalizing n head and then with the delimiting Num head to yield the entity/result reading, as per Harley’s proposal.

| (30) |  |

| a |

Admittedly, there is one problem with my proposed answer to the question concerning the derivation of the entity/result reading from the process VP base. The problem is that the current system, as it is, would seem to predict that the two morphologically related nouns—graduateN and graduationN—should behave identically with respect to VP-hood diagnostics but they, in fact, do not. For example, the latter may, but not the former, serve as an antecedent for do so replacement and occur with a VP-level adverbial, two diagnostics for the VP structure within process nominalizations (Fu et al. 2001). This point is shown by the contrast between (31) and (32).

| (31) | a.? | Yosuke’s graduation from the University of Arizona happened in 2008, but Mike’s doing so happened from the University of Toronto in 2006. |

| b.? | Yosuke’s graduation from the University of Arizona swiftly impressed the hiring committee at the University of British Columbia in 2008. | |

| (32) | a.* | Yosuke is a 2008 graduate from the University of Arizona, but Mike’s doing so from the University of Toronto happened in 2006. |

| b.* | Yosuke is a 2008 graduate from the University of Arizona, which impressed the hiring committee at the University of British Columbia in 2008. |

Here is one tentative solution to this problem, though I must leave a further investigation of it for future research. The solution owes itself to Alexiadou’s (2001)/Alexiadou et al.’s (2007) cross-linguistically robust observation that the possibility of adverbial modification requires the presence of aspect; without it, the modifier in question must syntactically surface, with adjectival morphology licensed instead within the nominal layer superimposed on a verbal base (see Hamm 1999 for further evidence for the correlation between aspect and adverbial modification based on three different types of nominalizations in Akatek Maya). Let us hypothesize, then, that the overt nominalizer -(a)tion selects an aspect phrase, or an event phrase in the sense of Travis (2010), whereas the zero nominalizer (Ø) selects a verbal base, such as vP (which, by itself, is not associated with any aspectual information). Given this hypothesis, the relevant parts of the derivations for the two deverbal nouns—graduationN and graduateN—will be represented as shown in (33) and (34), respectively.

| (33) | graduationN | (34) | graduateN |

|  |

The contrast between (31b) and (32b) now falls into place. The adverb swiftly in (31b) is licensed by the presence of the Asp head in (33), but it may not appear in (32b) because of the lack of this functional head, as shown in (34). Note that this account can also be extended to account for the fact that what semantically modifies the actions denoted by process nominals must appear instead as a pre-nominal adjective, as illustrated in (5).

The contrast between (31a) and (32a) is also to be attributed to the presence vs. absence of the Asp head, granted that the complex root √grad(u)ate is a stative root. It is well-known that the do so pro-form cannot substitute stative VPs, such as know, unlike non-stative verbs, such as chase, as shown in (35a, b).

The Asp head in (33), specified with the [+bounded] feature, serves to derive a telic event named by the complex root. The pro-form then can successfully target the resulting “extended” vP. The derivation in (34), by contrast, lacks this head. As such, the vP, derived through merger of the stative root with the verbalizing v head, remains stative. Consequently, this constituent cannot be substituted by the pro-form because of the stativity restriction. Recall that the vP in (34) serves as an antecedent for vP-ellipsis, as attested in (11a). This result is entirely consistent with my present analysis, for VP-ellipsis is free from the stativity restriction imposed on do so, as shown by the grammaticality of (36a).

| (35) | a. | * Susan knew John, but Karen didn’t do so. |

| b. | Susan chased John, but Karen didn’t do so. |

| (36) | a. | Susan knew John, but Karen didn’t [VP …]. |

| b. | Susan chased John, but Karen didn’t [VP …]. |

4. On the Directionality of Conversion: A View from Category-Mismatched VP-Ellipsis

In the previous section, I have argued that the directional asymmetry observed in category-mismatched VP-ellipsis with deverbal nominals, like graduateN, receives a structural explanation in terms of a word-based syntactic structure underlying them, which postulates an abstract VP structure in it, thereby licensing the ellipsis of the VP headed by graduateV. The purpose of this section is to take this result a step further and explore empirical ramifications of the proposed analysis for the so-called directionality issue raised by conversion. Essentially, the issue is which member of a particular zero-derived N-V pair is the base form from which the other form is derived? I will show that the syntactic identity condition on ellipsis allows us to shed light on this issue, when coupled with a phase-theoretical rendition of Kiparsky’s (1982a, 1982b) stratum-based theory of conversion.

4.1. Category-Mismatched VP-Ellipsis under V→ N and N→ V Conversions

Kiparsky’s (1982a, 1982b) theory of lexical phonology postulates that the lexicon is organized in a series of ordered lexical strata, each of which functions as the defining domain of the application of a restricted range of phonological/morphological rules characteristic of each stratum. As one of the primary motivations for this stratum-based approach to word formation, Kiparsky develops an eclectic analysis of conversion in English (see also Arad 2003 for a DM-based reanalysis of the same phenomenon in English and Modern Hebrew in terms of the dichotomy between root-derived and word-derived word formation; see also Section 4.3). Kiparsky draws on evidence from bisyllabic word stress placement, relative productivity, and the degree of segmental phonological rules to show that nouns are formed from verbs at stratum 1, yielding deverbal nouns, whereas it is verbs that are formed from nouns at stratum 2, yielding denominal verbs.

Deverbal nouns formed at stratum 1 are accompanied by changes in the location of the primary word stress, as shown in zero-related pairs listed in (37). This stress shift occurs here because a word stress rule in English operating at stratum 1 places the main stress on the final syllable of a verb and on the first syllable of a noun. By contrast, denominal verbs, illustrated by N-V pairs as in (38), do not exhibit a stress shift. These examples are formed at stratum 2, where these verbs escape the application of the aforementioned stress rule that holds at stratum 1. As a result, they inherit the stress pattern from their nominal bases.

| (37) | Stratum 1: verb→noun (deverbal noun), accompanied by a shift in the primary stress |

| torméntV→tórmentN, transférV→tránsferN, digéstV→dígestN, progréssV→prógressN, | |

| convíctV→cónvictN, and survéyV→súrveyN | |

| (38) | Stratum 2: noun→verb (denominal verb), not accompanied by a shift in the primary stress |

| pátternN→pátternV, pátentN→pátentV, and léverN→léverV |

Kiparsky’s theory of English conversion makes two predictions, when coupled with the syntactic identity condition developed above, to account for the directional asymmetry of category-mismatched VP-ellipsis. One prediction is that a deverbal noun (formed at stratum 1) should serve as an antecedent licensing the ellipsis of its verbal base because the syntactic structure of the deverbal noun properly contains that of the underlying verb that feeds the noun. The other prediction, tested neither by Tan (2018) nor by this paper so far, is that a denominal verb (formed at stratum 2) should serve as an antecedent licensing the ellipsis of its nominal base because the derivation underlying the former contains the derivation underlying the latter. These predictions are indeed borne out. Consider (39–40). All these examples are grammatical with or without VP/NP-ellipsis. Note further that the sentence in (39b) needs contrastive focus on they.

The grammaticality of the examples in (39a–c) shows that deverbal nouns—tránsfer, prógress, and export—license the ellipsis of the VPs headed by their respective verbal bases. The grammaticality of the examples in (40a–c) further shows that the reverse antecedent–ellipsis pair is available for denominal verbs pátent, desíre, and tattóo, which license the ellipsis of the VPs headed by their verbal counterparts.

| (39) | Stratum 1: verb→noun (deverbal noun) |

| Prediction: The N licenses the ellipsis of the VP headed by its verbal base. ✔ | |

| a. | A [N tránsfer] of $500 would solve many a student’s financial problems, so I strongly recommend that, no less than $400, all parents do [VP |

| b. | Understanding the [N prógress] by their predecessors would prove necessary before they could [VP |

| c. | The [N éxport] of endangered animals is illegal, so I can assure you that, these endangered animals, our company didn’t [VP |

| (40) | Stratum 2: noun→verb (denominal verb) |

| Prediction: The V licenses the ellipsis of the NP headed by its nominal base. ✔ | |

| a. | ?He applied to [V pátent] his five inventions, but was only awarded three [NP |

| b. | ?He gave many of what they [V desíre], but he never could fulfill any of his own [NP |

| c. | They wish to [V tattóo] their forearms but are unsure of which [NP |

Let us now see whether ellipsis in the other direction would be ungrammatical. More specifically, for deverbal nouns (V→N derivation), as shown in (39), does the verbal variant license the ellipsis of the NP headed by its nominal variant? Similarly, for denominal nouns (N→V derivation), as shown in (40), does the nominal variant license the ellipsis of the VP headed by its verbal variant? These results generally support the hypothesis that the directionality of conversion, i.e., V→N vs. N→V, inversely correlates with the directionality of category-mismatched VP-ellipsis licensing. That is, the verbal antecedent does not license NP-ellipsis. In the same way, the nominal antecedent does not license VP-ellipsis. Examples (41–42) illustrate category-mismatched VP-ellipsis involving V→N and N→V conversion types, respectively. Note that according to my native speaker consultants, all the starred examples below are grammatical when NP/VP-ellipsis does not occur, indicating that the ungrammaticality of these examples are to be attributed to the application of ellipsis.

The only problem here is concerned with the grammaticality of the example in (41a), and I can only make one speculation on it. Although transfer is historically a deverbal noun, it is not obvious whether contemporary English speakers treat the word synchronically as such. Indeed, it is possible that synchronically speaking, the N-V conversion pair for transfer actually takes place at stratum 2 (N→V). This position is supported by the observation that the verb transfer has stress on the first syllable for many of my native speaker consultants, on a par with the nominal variant. I leave this problem open here for future research.

| (41) | a. | John’s parents [V transférred] money to him on three separate occasions, but only two [NP |

| b.*? | Mary [V progréssed] significantly over the semester, but John’s [NP | |

| c. *? | The company [V expórted] lithium all over the world, and the accountant had to figure out which [NP | |

| (42) | a.* | My neighbors were looking at different [N cruises] available at the travel agent, but I’ve never had the desire to [VP cruise]/but I can’t [VP |

| b.* | There’s not much water available during the summer months for our gardens, so we’re not allowed to [VP | |

| c.* | There’s lots of bandages in the store room for the student nurses to learn how to [VP | |

| d.* | There’s lots of bandages in the store room for the student nurses to practice with, so they can [VP |

One direct implication of my analysis for the directionality problem, then, is that any adequate theory of conversion in English must be designed to accommodate the formation of particular zero-related pairs in both directions (N→V or V→N) at the very least.

4.2. Phase-Theoretical Word Formation in Distributed Morphology

Before concluding this section, there is one important question to address, which has to do with the notion of cyclic word formation in more contemporary theories of the morphology–syntax interface. Recall that my proposed analysis of the directionality of N-V conversion in English so far has simply borrowed the stratum-based level ordering assumption from Kiparsky’s (1982a, 1982b) Lexical Phonology to differentiate two types of zero-related N-V pairs, one deverbal (stratum 1) and the other denominal (stratum 2), with their associated primary stress patterns. However, my analysis adopts a purely syntactic approach to such word formation along the lines of the non-lexicalist stance of the DM framework, which does not square well with the lexicalist stance of Lexical Phonology. Accordingly, a question arises as to how one could formally capture the sort of level-ordering effects traditionally attributed to the existence of a sequentially ordered block of strata/levels/cycles in a modern syntactically oriented theory of word formation without such theoretical constructs.

I maintain that the cyclic effects of word formation, once captured through Kiparsky’s notion of strata, can still be accommodated through a phase-theoretical version of the DM approach to word formation, as outlined in Arad (2003), Marantz (2001, 2007), and Marvin (2003, 2013), which, in turn, has been further articulated in works such as Lowenstamm (2015), Creemers et al. (2021), Newell (2021), and Sande et al. (2020), among others. Marantz (2001) proposes that lexical categories, such as verb, noun, and adjective, are derived through the merger of an acategorial root with one of the category-defining functional x heads, i.e., n, v, and a. For example, the root √destroy is acategorial in syntax and has its category fixed as noun, verb, or adjective, depending on which category-defining head among the three heads is merged with the root, with the results of this merger being externalized post-syntactically as destroy, destruction, and destructive, in the manner schematically depicted in (43a–c), respectively.

Marantz (2001, 2007) argues that each category-defining head constitutes a phase head and suggests that cyclic effects, including stress shifts, can be accounted for in terms of the phase-based structure of words. Note, however, that even if all the category-defining heads are phases, we still cannot really explain how the distinction between stratum 1 zero affixes and stratum 2 zero affixes involved in N-V conversion or between stress-shifting/+boundary affixes and stress-neutral/#-boundary affixes in Chomsky and Halle’s (1968) classic SPE model can be properly derived. For example, within Marantz’s phase-theoretical system, the syntactic structures for atomícity (with the level 1/stratum 1 suffix -ity) and atómicness (with the level 2/stratum 2 suffix -ness) are identical. Hence, we cannot resort to any structural difference to derive the distinction between stress-shifting and stress-neutral affixes.

| (43) | a. | destroy | b. | destruction | c. | destructive |

|  |  |

For this reason, I will adopt a more relativized version of Marantz’s (2001, 2007) phase-based theory of word formation informed by Lowenstamm (2015) and Creemers et al. (2021); see also Newell (2021), Sande et al. (2020) and Simonović (2022) for related approaches in phase theory. Lowenstamm and Creemers et al. propose that the difference between level 1/stratum 1 and level 2/stratum 2 affixes can be reduced to their c-selectional difference: the former has an uninterpretable categorial feature [u √P], which must be checked against a root, whereas the latter has an uninterpretable categorial feature [u xP], which must be checked against an already categorized word. To illustrate, let us consider the syntactic structures for atomícity and atómicness, shown in (44) and (45), respectively.

| (44) | atomícity (with -ity [u √P]) | (45) | atómicness (with -ness [u xP]) |

|  | ||

| (adopted from Creemers et al. 2021:64) | |||

The difference between the two types of affixes with respect to stress shifts is now correctly derived if cyclic phonological operations, such as stress assignment in English, apply only in the first phase (Marantz 2001, 2013; Arad 2003), defined here as the mid-derivational unit consisting of the root and the lowest root-selecting affix (see also Embick 2010:51–53 for a detailed discussion on the technical definition of spell-out domains). Stress shift occurs in (44) because the root √ity must occur within the first phase to satisfy its root-selecting property. By contrast, the root √ness must occur outside the first phase head, as shown in (45), because it must merge with an already categorized adjective and, hence, has no way to affect the stress behavior of the output of the first phase. In this way, the difference between the two types of affixes, once attributed to a stipulated morphological diacritic in previous lexicalist theories, can independently be accounted for by the interaction of an independently motivated phase-theoretical assumption regarding the first phase with general selectional properties of affixes.

Let us now consider what the above phase-theoretical approach to word formation implies regarding level 1/stratum 1 and level 2/stratum 2 conversions. Under this approach, the presence vs. absence of stress shifts in (39) vs. (40) indicates that the zero nominalizing affix deriving a denominal verb is included within the first phase, whereas the zero verbalizing affix deriving a denominal verb is located outside the relevant domain. To see why that is, consider the derivations shown in (46) and (47).

In the V→N derivation in (46), the root √transfer is merged with the verbalizing v head to yield the verb transfer. This result, in turn, is merged with the nominalizing n head. The stress-shifting behavior of the V→N derivation falls into place if the nP is the first phase domain so that the zero nominalizer may participate in cyclic stress assignment. In the N→V derivation in (47), by contrast, the root √patent is merged first with the nominalizing n head to yield the noun patent. The noun, in turn, is merged with the zero verbalizing v head to yield the verb patent. The lack of a stress shift here is accounted for if nP forms a phase boundary excluding the v head so that its merger will not have any effect on the stress assignment. These considerations suggest then that n is, but v is not, a phase-defining head.

| (46) | V→N derivation (stratum 1: with stress shift) | (47) | N→V derivation (stratum 2: without stress shift) |

|  |

The question, then, is why this is the case. In his original conception of phasehood in clausal domains, Chomsky (2000, 2001, 2004, 2008) argues that only verbs with a full argument structure—transitive and experiencer verbs—are headed by phasal vs (which he dubs v*). Adopting this definition as a general heuristic diagnostic for phasehood in general, it is reasonable that the v head at least of the kind that participates in conversion, as in (46) or (47), is not a phase, for it is not associated with any argument structure. In fact, developments in the fine-grained structure of the traditional verb phrase converge on the view that so-called internal and external arguments of a verb are dissociated from the verb but instead are introduced by independent functional heads, such as aspect and voice (Borer 1994, 1998; Kratzer 1996; Harley 1995, 2013, among many others), a view that lends further credence to the idea that it is the entire verbal spine instantiating the full argument/event structure that forms the verbal phase, not just vP.

As for the phasehood of nP, a number of works in morphophonology argue that the NP below the D head counts as phasal (Marvin 2003; Newell 2008; Embick 2010; Embick and Marantz 2008; Newell and Piggott 2014; Simpson and Syed 2016; Syed and Simpson 2017; Simpson and Park 2019). Recall that we discussed Harley’s (2009) proposal, in Section 3.2, that process nominals with mass noun denotations are coerced into being count nouns to yield the result/entity reading with the help of a delimiting functional head, such as Num and Cl(assifier). Just as the phasehood of a verbal domain is linked to its voice/argument structure properties, it is not far-fetched to speculate that the phasehood of a nominal domain is also linked to similar nominal properties, such as boundedness and delimitedness. Needless to say, pursuing further links between verbal and nominal domains would take us far afield from the central focus of this paper and must be left as one of the important tasks for future research.

4.3. Another Impact of the Proposed Analysis on the Directionality of N-V Conversion in English

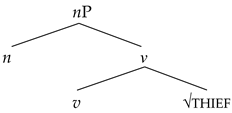

In this section, I would like to briefly explore another potential implication of my proposed analysis of conversion, as suggested to me by an anonymous reviewer. The implication is that my analysis can be used to figure out whether roots are categorial. I explore this specific implication below with the minimal pair in (10a, b), repeated here as (48a, b).

The grammaticality of (48a) is straightforward. The ellipsis of the VP headed by rob is acceptable because the antecedent noun clearly has the VP base selected by the agentive nominalizer -er. The question is why (48b) is ungrammatical, given that the noun thief is morphologically related to the verb thieve, so that the ellipsis of the VP headed by the latter, in principle, could be licensed by the former. Note that the pattern observed here is abstractly similar to that in (27–28): clearly morphologically deverbal nouns, such as dancer and singer, license the ellipsis of the VP headed by dance and sing, but non-deverbal nouns, such as ballerina and chorister, do not. Given this reasoning, the ungrammaticality of (48b) implies that the noun thief is not derived through the verb thieve, as shown in (49), for, otherwise, it would be grammatical. Instead, the noun is derived through the acategorial root √thief, as shown in (50), so that there is no suitable VP base to antecede VP-ellipsis.

| (48) | a.? | That man is a robber, and when he does [VP … ], he tries not to make any noise. |

| b.* | That man is a thief, and when he does [VP … ], he tries not to make any noise. | |

| (Merchant 2013a, p. 447) |

| (49) | Thief is derived from the verb thieve. | (50) | Thief is derived from the acategorial root √thief. |

|  |

To the extent that this analysis of the contrast between (48a) and (48b) is on the right track, it shows that all three logically possible derivational options within the basic DM assumptions are available for conversion in English, two word-based derivations (V→N and N→V) and one root-derived derivation (with a common acategorial root yielding both Ns and Vs), with all their differences attributed to different hierarchical arrangements of the same set of universally available grammatical primitives: √, n, and v.

Note that the root-based derivation predicts that there should be conversion pairs whose directionality cannot be determined. Although further testing of this prediction is left for future research, it is possible that it is borne out by classic data such as loveN vs. loveV that have been used to argue against the unidirectionality of conversion (see also Umbreit 2010, for instance, for a bidirectional approach to such conversion pairs).8

5. Concluding Remarks

In this paper, I have studied directional asymmetries in configurations involving category mismatch under VP-ellipsis, a pattern first noted by Tan (2018), to shed light on debates concerning the directionality of conversion in English. For example, the noun graduateN can antecede ellipsis of a VP headed by its verbal counterpart, graduateV, but not vice versa. I have proposed that asymmetries of this sort can be accounted for only by a syntactic identity condition to the effect that the syntactic structure of an antecedent expression must properly contain that of an elided constituent. Having established this analysis, I then used it as a critical probe into the abstract syntax underlying zero-related N-V pairs to address the directionality issue concerning those pairs. I have presented novel data to show that both derivational patterns, N→V and V→N, as well as the common root-based derivation, must be admitted into grammar to properly account for the entire range of possible directional asymmetries exhibited by conversion in English.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Sciences (JSPS) KAKENHI Grant Number JP19K00560.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | I thank the editors of the Special Issue, Akiko Nagano and Ryohei Naya, and three anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on previous versions of this paper. I wish to express my deepest gratitude to Michael Barrie for many hours of stimulating discussions, numerous e-mail exchanges on the project, reported herein, since 2018, and tons of data and intriguing observations on English conversion, all included herein. My thanks also go to my native speaker consultants—Michael Barrie (again), Jason Ginsburg, Si Kai Lee, Jun Jie Lim, Hannah Lin, Keely New, and Hansel Tan—for their help with judgements of the English data and to Nobu Goto, Heidi Harley, Satoru Kanno, Hideki Kishimoto, Shin-Ichi Kitada, Masako Maeda, Taichi Nakamura, Kuniya Nasukawa, Dongwoo Park, Myung-Kwan Park, Jeff Punske, Matthew Reeve, Kensuke Takita, Hansel Tan, and Dwi Hesti Yuliani for various suggestions, questions and/or references. Of course, all the remaining inadequacies and oversights are my own. | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | More recent major works that adopt the syntactic identity approach to VP-ellipsis and its kin include Rudin (2019) and Ranero (2021). Rudin (2019) proposes that no mismatch is tolerated below vP, which he dubs the eventive core, whereas mismatch is, in principle, tolerable above this domain as long as discourse and pragmatic constraints are properly met. Couching Merchant’s intuition within his theory of the eventive core as the absolute boundary of elliptical mismatch, Rudin suggests (p. 281) that VP-ellipsis targets the entire verbal domain/vP, but its identity calculation domain is smaller than the ellipsis site itself. Ranero (2021) also pursues the general syntactic identity approach to ellipsis. Ranero proposes the universal syntactic identity condition to the effect that the antecedent and material properly contained at the ellipsis site must be featurally non-distinct, where featurally non-distinct means that there must be no clashing values in any feature slot shared between the antecedent and the ellipsis site. See also Stockwell (2024) for the latest analysis of the varying acceptability of voice-mismatched VP-ellipsis cases based on a focus-based condition on ellipsis (Rooth 1992a, 1992b). | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | There are a number of controversies regarding Merchant’s (2008, 2013a, 2013b) syntactic-identity-based analysis of (1) vs. (2), which I will not delve into herein. See Miller (1991), Kehler (2000, 2002), Coppock (2001), Kertz (2010), Tanaka (2011), and Nakamura (2013b), among others, for critical appraisals. My stance herein, however, is not to defend the syntactic identity condition on (VP-) ellipsis but rather simply to use it as a given to explore its implications for the syntactic derivation of zero-related N-V pairs in English. | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | I polled seven native English speakers in total, three linguistic specialists and four advanced undergraduate students of syntax, for their acceptability judgments on the examples in (11–12). They all did obtain some contrast in acceptability, but admittedly it was weak. An anonymous reviewer, for example, reports that he/she personally does not perceive a contrast between (11a) and (11b) at all. The same reviewer also points out that he/she would give (12a) “?”and find (12b) to be perfect, but the other speakers I polled all find that (12a) sounds better than (12b). For this reason, I included a few more example pairs illustrating the directional asymmetry in (13–14), for which all the seven speakers I polled reported a clearer contrast. There is clearly interspeaker variation in these judgements. Thus, the same reviewer notes that (14b) is only slightly odd, giving it “?” rather than “??”, so the judgement reported herein is only relative, but the point stands that (14a) is noticeably better than (14b), at least for all the speakers I polled. | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5 | An anonymous reviewer points out that Llombart-Huesca’s (2002) proposal that one is inserted as a last resort in the context of NP-ellipsis is complicated by the fact that it is not always in complementary distribution with NP-ellipsis. Kayne (2015:17) observes that this proposal would not account for the grammaticality of both (ia) and (ib) (for many speakers, see below); if one-support were a last resort strategy, then the grammatical example in (ia) would block the example (ib) as being ungrammatical. Examples (iia–c) show other putative cases, where complementarity between one(s) and NP-ellipsis breaks down.

It is also to be noted that some native speakers, including Kayne, accept (ia) but reject (ib). The existence of this pattern of acceptability judgment provides support for Llombart-Huesca’s proposal. | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6 | There is one speaker among the seven native English speakers who told me that (25b) can mean that Olga is a ballerina who does ballet dance beautifully. So, for this particular speaker, the sentence Olga is an ugly but beautiful ballerina does not sound that bad, suggesting that the adjective beautiful may refer to the dancing event even though there is no verb hidden in ballerina. In this paper, I simply follow the standard observation cited in the relevant literature (Belk 2013; Winter and Zwarts 2019), setting aside this interspeaker variation in the availability of the non-intersective manner of adverb interpretation. | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7 | I must hasten to add that the pronunciation of the verbal use of export is dialect dependent, so both éxport and expórt are equally common for the verb, though the noun must be éxport. | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8 | I would like to thank Akiko Nagano (personal communication) for suggesting this line of argument. |

References

- Alexiadou, Artemis. 2001. Functional Structure in Nominals: Nominalization and Ergativity. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Alexiadou, Artemis, Liliane Haegeman, and Melita Stavrou. 2007. Noun Phrase in the Generative Perspective. Berlin and New York: Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Arad, Maya. 2003. Locality constraints on the interpretation of roots: The case of Hebrew denominal verbs. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 21: 737–78. [Google Scholar]

- Belk, Zoë. 2013. The paradox of the heavy drinker. In UCL Working Papers in Linguistics 25. Edited by Diana Mazzarella, Isabelle Needham-Didsbury and Kevin Tang. London: University College London Psychology and Language Sciences, pp. 102–11. [Google Scholar]

- Borer, Hagit. 1994. The projection of arguments. In University of Massachusetts Occasional Papers in Linguistics 17. Edited by Elena Benedicto and Jeffrey Runner. Amherst: GLSA, University of Massachusetts, pp. 19–47. [Google Scholar]

- Borer, Hagit. 1998. Deriving passive without theta-grids. In Morphology and Its Relations to Phonology and Syntax. Edited by Steven G. Lapointe, Diane K. Brentari and Patrick M. Farrell. Stanford: CSLI Publications, pp. 60–99. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, Noam. 1970. Remarks on nominalization. In Readings in English Transformational Grammar. Edited by Roderick A. Jacobs and Peter S. Rosenbaum. Waltham: Ginn, pp. 184–221. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, Noam. 2000. Minimalist inquiries: The framework. In Step by Step: Essays on Minimalist Syntax in Honor of Howard Lasnik. Edited by Roger Martin, David Michaels and Juan Uriagereka. Cambridge: MIT Press, pp. 89–155. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, Noam. 2001. Derivation by Phase. In Ken Hale: A Life in Language. Edited by Michael Kenstowicz. Cambridge: MIT Press, pp. 1–52. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, Noam. 2004. Beyond explanatory adequacy. In Structures and Beyond: The Cartography of Syntactic Structures. Edited by Adriana Belletti. Oxford: Oxford University Press, vol. 3, pp. 104–31. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, Noam. 2008. On phases. In Foundational Issues in Linguistic Theory: Essays in Honor of Jean-Roger Vergnaud. Edited by Robert Freidin, Carlos P. Otero and Maria Luisa Zubizarreta. Cambridge: MIT Press, pp. 133–66. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, Noam, and Morris Halle. 1968. The Sound Pattern of English. New York: Harper and Row. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, Sandra. 2013. Syntactic identity in sluicing: How much and why. Linguistic Inquiry 44: 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Sandra, William A. Ladusaw, and James McCloskey. 1995. Sluicing and logical form. Natural Language Semantics 3: 239–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppock, Elizabeth. 2001. Gapping: In defense of deletion. In Proceedings of the Thirty-Seventh Annual Meeting of the Chicago Linguistics Society. Edited by Mary Andronis, Christoper Ball, Heidi Elston and Sylvain Neuvel. Chicago: Chicago Linguistic Society, University of Chicago, pp. 133–48. [Google Scholar]

- Creemers, Ava, Jan Don, and Paula Fenger. 2021. Some affixes are roots, others are heads. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 36: 45–84. [Google Scholar]

- Dalrymple, Mary, Stuart M. Shieber, and Fernando Pereira. 1991. Ellipsis and higher order unification. Linguistics and Philosophy 14: 399–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbourne, Paul. 2001. E-type anaphora as NP-deletion. Natural Language Semantics 9: 241–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Embick, David. 2010. Localism versus Globalism in Morphology and Phonology. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Embick, David, and Alec Marantz. 2008. Architecture and blocking. Linguistic Inquiry 39: 1–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Jingqi, Thomas Roeper, and Borer Hagit. 2001. The VP within process nominals: Evidence from adverbs and the VP anaphor do-so. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 19: 549–82. [Google Scholar]

- Gengel, Kirsten. 2013. Pseudogapping and Ellipsis. London: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grimshaw, Jane. 1990. Argument Structure. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hamm, Fritz. 1999. Modelltheoretische Untersuchungen zur Semantik von Nominalisierungen. Habilitationschrift. Túbingen: University of Túbingen. [Google Scholar]

- Hankamer, Jorge. 1979. Deletion in Coordinate Structures. New York: Garland. [Google Scholar]

- Hardt, Daniel. 1993. Verb Phrase Ellipsis: Form, Meaning and Processing. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- Harley, Heidi. 1995. Subjects, Events and Licensing. Ph.D. dissertation, MIT, Cambridge, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Harley, Heidi. 2009. The morphology of nominalizations and the syntax of vP. In Quantification, Definiteness, and Nominalization. Edited by Anastasia Ginnakidou and Monika Rathert. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 321–43. [Google Scholar]

- Harley, Heidi. 2013. External arguments and the mirror principle: On the independence of Voice and v. Lingua 125: 34–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harley, Heidi, and Jason D. Haugen. 2007. Are there really two different classes of instrumental denominal verbs in English? Snippets 16: 9–10. [Google Scholar]

- Jayaseelan, Karattuparambil A. 1990. Incomplete VP deletion and gapping. Linguistic Analysis 20: 64–81. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Kyle. 2001. What VP ellipsis can do, and what it can’t, but not why. In The Handbook of Contemporary Syntactic Theory. Edited by Mark Baltin and Chris Collins. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, pp. 439–79. [Google Scholar]

- Karttunen, Lauri. 1969. Pronouns and variables. In Papers from the Fifth Regional Meeting of the Chicago Linguistic Society. Edited by Robert I. Binnick, Alice Davison, Georgia M. Green and Jerry L. Morgan. Chicago: Chicago Linguistic Society, pp. 108–16. [Google Scholar]

- Kayne, Richard S. 2015. English one and ones as Complex Determiners. Master’s thesis, New York University, New York, NY, USA. Available online: https://lingbuzz.net/lingbuzz/002542 (accessed on 11 March 2024).

- Kehler, Andrew. 2000. Coherence and the resolution of ellipsis. Linguistics and Philosophy 23: 533–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehler, Andrew. 2002. Coherence, Reference, and the Theory of Grammar. Stanford: CSLI Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Kehler, Andrew, and Gregory Ward. 1999. On the semantics and pragmatics of identifier so. In The Semantics/Pragmatics Interface from Different Points of View. Edited by Ken Turner. Amsterdam: Elsevier, pp. 233–256. [Google Scholar]

- Kertz, Laura. 2008. Focus structure and acceptability in verb phrase ellipsis. In WCCFL27: Proceedings of the 27th West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics. Edited by Natasha Abner and Jason Bishop. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project, pp. 283–91. [Google Scholar]

- Kertz, Laura. 2010. Ellipsis Reconsidered. Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, San Diego, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Sun-Woong. 2020. Mismatches in ellipsis: Category mismatch asymmetry in English VP-ellipsis. Korean Journal of English Language and Linguistics 20: 475–495. [Google Scholar]

- Kiparsky, Paul. 1982a. From cyclic phonology to lexical phonology. In The Structure of Phonological Representations, Part 1 (Linguistic Models). Edited by Harry van der Hulst and Norval Smith. Dordrecht: Foris, pp. 131–75. [Google Scholar]

- Kiparsky, Paul. 1982b. Lexical morphology and phonology. In Linguistics in the Morning Calm: Selected Papers from SICOL-1981. Seoul: Hanshin Publishing Company, vol. 1, pp. 3–91. [Google Scholar]

- Kratzer, Angelika. 1996. Severing the external argument from its verb. In Phrase Structure and the Lexicon. Edited by Johan Rooryck and Laurie Zaring. Dordrecht: Kluwer, pp. 109–37. [Google Scholar]

- Larson, Richard. 1998. Events and modification in nominals. In SALT VIII. Edited by Devon Strolovitch and Aaron Lawson. Ithaca: Cornell University, pp. 145–68. [Google Scholar]

- Lasnik, Howard. 1995. A note on pseudogapping. In MIT Working Papers in Linguistics 27. Edited by Rob Pensalfini and Hiroyuki Ura. Cambridge: MIWPL, pp. 143–63. [Google Scholar]

- Lees, Robert B. 1960. The Grammar of English Nominalizations. The Hague: Mouton. [Google Scholar]

- Lieber, Rochelle. 2016. English Nouns: The Ecology of Nominalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Llombart-Huesca, Amalia. 2002. Anaphoric one and NP-ellipsis. Studia Linguistica 56: 59–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowenstamm, Jean. 2015. Derivational affixes as roots: Phasal spell-out meets English stress shift. In The Syntax of Roots and the Roots of Syntax. Edited by Artemis Alexiadou, Hagit Borer and Florian Schäfer. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 230–59. [Google Scholar]

- Marantz, Alec. 1997. No escape from syntax: Don’t try morphological analysis in the privacy of your own lexicon. In University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics 4. Edited by Alexis Dimitriadis, Laura Siegel, Clarissa Surek-Clark and Alexander Williams. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, pp. 201–25. [Google Scholar]

- Marantz, Alec. 2001. Words and Things. Master’s thesis, MIT, Cambridge, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Marantz, Alec. 2007. Phases and words. In Phases in the Theory of Grammar. Edited by Sook Hee Choe. Seoul: Dong In, pp. 191–220. [Google Scholar]

- Marantz, Alec. 2013. Locality domains for contextual allomorphy across the interfaces. In Distributed Morphology Today: Morphemes for Morris Halle. Edited by Ora Matushansky and Alec Marantz. Cambridge: MIT Press, pp. 95–116. [Google Scholar]

- Marchand, Hans. 1963. On a question of contrary analysis with derivationally connected but morphologically uncharacterized words. English Studies 44: 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchand, Hans. 1964. A set of criteria for the establishing of derivational relationship between words unmarked by derivational morphemes. Indogermanische Forschungen 69: 10–19. [Google Scholar]

- Marvin, Tatjana. 2003. Topics in the Stress and Syntax of Words. Ph.D. dissertation, MIT, Cambridge, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Marvin, Tatjana. 2013. Is word structure relevant for stress assignment? In Distributed Morphology Today. Edited by Ora Matushansky and Alec Marantz. Cambridge: MIT Press, pp. 79–94. [Google Scholar]

- Merchant, Jason. 2001. The Syntax of Silence: Sluicing, Islands, and the Theory of Ellipsis. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Merchant, Jason. 2008. An asymmetry in voice mismatches in VP-ellipsis and pseudogapping. Linguistic Inquiry 39: 169–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merchant, Jason. 2013a. Polarity Items under ellipsis. In Diagnosing Syntax. Edited by Lisa Lai-Shen Cheng and Norbert Corver. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 441–62. [Google Scholar]

- Merchant, Jason. 2013b. Voice and ellipsis. Linguistic Inquiry 44: 77–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Philip H. 1991. Clitics and Constituents in Phrase Structure Grammar. Ph.D. dissertation, Rijksuniversiteit te Utrecht, Utrecht, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Philip H., and Barbara Hemforth. 2014. Verb Phrase Ellipsis with Nominal Antecedents. Master’s thesis, University of Paris Diderot, Paris, France. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura, Taichi. 2013a. Semantic identity and deletion. English Linguistics 30: 643–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, Taichi. 2013b. Voice mismatches in sloppy VP-ellipsis. Linguistic Inquiry 44: 519–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, Heather. 2008. Aspects in the Morphology and Phonology of Phases. Ph.D. dissertation, McGill University, Montréal, QC, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Newell, Heather. 2021. Deriving Level 1/Level 2 affix classes in English: Floating vowels, cyclic syntax. Acta Linguistica Academica 68: 31–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, Heather, and Glyne Piggott. 2014. Interactions at the syntax-phonology interface: Evidence from Ojibwe. Lingua 150: 332–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Myung-Kwan, and Sunjoo Choi. 2019. Ellipsis and replacement in categorial mismatch. Korean Journal of English Language and Linguistics 19: 194–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranero, Rodrigo. 2021. Identity Conditions on Ellipsis. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Maryland, College Park, MD, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Rooth, Matts. 1992a. A theory of focus interpretation. Natural Language Semantics 1: 75–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rooth, Matts. 1992b. Ellipsis redundancy and reduction redundancy. In Proceedings of the Stuttgart Ellipsis Workshop, Arbeitspapiere des Sonderforschungsbereichs 340. Edited by Stephen Berman and Arild Hestv+ik. Stuttgart: Universitäten Stuttgart und Tübingen in Kooperation mit der IBM Deutschland, pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Rudin, Deniz. 2019. Head-based syntactic identity in sluicing. Linguistic Inquiry 50: 253–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saab, Andrés, and Anikó Lipták. 2015. Movement and deletion after syntax: Licensing by inflection reconsidered. Studia Linguistica 70: 66–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sag, Ivan. 1976. Deletion and Logical Form. Ph.D. dissertation, MIT, Cambridge, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Sande, Hannah, Peter Jenks, and Sharon Inkelas. 2020. Cophonologies by ph(r)ase. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 38: 1211–62. [Google Scholar]

- Simonović, Marko. 2022. Derivational affixes as roots across categories. Journal of Slavic Linguistics 30: 195–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, Andrew, and Saurov Syed. 2016. Blocking effects of higher numerals in Bangla: A phase-based approach. Linguistic Inquiry 47: 754–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, Andrew, and Soyoung Park. 2019. Strict vs. free word order patterns in Korean and cyclic linearization. Studia Linguistica 3: 139–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockwell, Richard. 2024. Ellipsis, contradiction and voice mismatch. Glossa 8: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, Saurov, and Andrew Simpson. 2017. On the DP/NP status of nominal projections in Bangla: Consequences for the theory of phases. Glossa 2: 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, Shoichi. 2004. Pseudogapping and cyclic linearization. In Proceedings of the Thirty-Fourth Meeting of the North East Linguistic Society. Edited by Keir Moulton and Matthew Wolf. Amherst: GLSA, vol. 3, pp. 571–85. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Hansel Jian Xin. 2018. Category Mismatch in VP-Ellipsis. Master’s thesis, National University of Singapore, Singapore. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, Hidekazu. 2011. Syntactic identity and ellipsis. The Linguistic Review 28: 79–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travis, Lisa. 2010. Inner Aspect: The Articulation of VP. Dordrecht: Springer. [Google Scholar]