Abstract

This study examines how implied speaker nationality, which serves as a proxy for bilingual/monolingual status, influences social perception and linguistic evaluation. A modified matched-guise experiment was created with the speech of eight bilingual U.S. Spanish speakers from Texas talking about family traditions; the speech stimuli remained the same, but the social information provided about the speakers–whether they were said to be from Mexico (implied monolingual) or from Texas (implied bilingual)–varied. Based on 140 listeners’ responses (77 L2 Spanish listeners, 63 heritage Spanish listeners), quantitative analyses found that overall listeners evaluated ‘Mexico’ voices as more able to teach Spanish than ‘Texas’ voices. However, only heritage listeners perceived ‘Mexico’ voices as being of higher socioeconomic status and of more positive social affect than ‘Texas’ voices. Qualitative comments similarly found that heritage listeners evaluated ‘Mexico’ voices more favorably in speech quality and confidence than ‘Texas’ voices. The implications are twofold: (i) the social information of implied monolingualism/bilingualism influences listeners’ social perceptions of a speaker, reflecting monoglossic language ideologies; and (ii) there exists indeterminacy between language and social meaning that varies based on differences in lived experiences between L2 and heritage Spanish listeners. Extending on previous findings of indeterminacy between linguistic variants and meaning, the current study shows this also applies to (implied) language varieties, demonstrating the role of language ideologies in mediating social perception.

1. Introduction

Speech perception studies have been fundamental to understanding the social meaning1 of linguistic variation and language varieties. It has been shown that linguistic information affects social perceptions of speakers (Barnes 2015; Campbell-Kibler 2007; Chappell 2016; Regan 2022c; Walker et al. 2014; Wright 2021a) and that social information affects linguistic perception as well (Barnes 2019; Hay et al. 2006a, 2006b; Hay and Drager 2010; Koops et al. 2008; Niedzielski 1999). For example, subtle differences in linguistic information,2 such as hearing affricate [t∫] or fricative [∫] for the voiceless prepalatal /t∫/ in Andalusian Spanish (Regan 2020), can affect the social perception3 of the speaker. Social information, such as implied speaker nationality (Hay et al. 2006a; Niedzielski 1999) or implied speaker ethnicity (Rubin 1992; Gutiérrez and Amengual 2016), has also been found to affect social perception and/or linguistic evaluation.4 The majority of studies thus far have focused on the role of linguistic information in social perception, with fewer studies examining the role of social information in social perception and/or linguistic evaluations, and the present study seeks to build on this body of work. Following previous research (Hay et al. 2006a; Rubin 1992; among others), we seek to determine how the presence of social information affects how listeners perceive a speaker and evaluate their speech. This approach allows sociolinguists to shed light on how language attitudes and language ideologies mediate the social meaning of language.

The current study focuses on the context of Texas, where both monolingual and bilingual varieties of Spanish are well represented. More specifically, it investigates the effect of a speaker’s implied nationality (i.e., ‘from Mexico’ or ‘from Texas’), which here serves as a proxy for bilingual or monolingual status, on listeners’ social and linguistic evaluations. Doing so sheds light on the role of monoglossic ideologies (see Section 2.2) in influencing how speakers are perceived, on the one hand, and explores whether differences in bilingualism type (second language versus heritage5 language speakers/listeners) affect one’s perception of monolingual6 and bilingual varieties of Spanish, on the other. To set the stage, Section 2 presents the background information, and the methodology is provided in Section 3. Section 4 reports the results of quantitative and qualitative analyses. Finally, Section 5 discusses the results in relation to the research questions, previous research, and theoretical implications.

2. Background

2.1. Social Information in Speech Perception

Rather than a linguistic variable having static meaning, third-wave7 approaches to language variation maintain that a variable’s social meaning is constantly renegotiated in various contexts and styles (Eckert 2005, p. 94). Eckert (2008), building on Silverstein’s (2003) notion of indexical order, proposed the indexical field to theorize the social meaning of linguistic variation. The indexical field is a “constellation of meanings that are ideologically linked. As such it is inseparable from the ideological field and can be seen as an embodiment of ideology in linguistic form” (Eckert 2008, p. 464). The multitude of social meanings8 attached to linguistic variants has been supported by several sociolinguistic perception studies, where the manipulation of a single phonetic variant (Barnes 2015; Campbell-Kibler 2007, 2008, 2011; Chappell 2016, 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021a; Regan 2020, 2022b, 2022c; Walker et al. 2014; Wright 2021a, 2021b) or of a single word (Baird et al. 2018; Regan 2022a) between guises affects listeners’ evaluations. Other sociolinguistic perception studies have examined the indexical fields of language varieties9 (Callesano and Carter 2019; Carter and Callesano 2018; Chappell and Barnes 2023; Niedzielski and Preston 1999), demonstrating that speech perception research can further our understanding of the social meaning of language varieties as well.

While most speech perception work has examined the role of linguistic information on social perception, there is a growing number of studies exploring the effect of social information on linguistic and social perception. For instance, implied age, portrayed through the visual stimuli of photos of older and younger speakers, has been used to examine the linguistic perception of sound change, such as the near-square merger-in-progress in New Zealand (Hay et al. 2006b) and the split-in-progress of the pin-pen merger in Houston, TX (Koops et al. 2008), finding that listeners were aware of the phonetic distinction among older speakers in New Zealand and in younger speakers in Houston, respectively. Barnes (2019) used speaker photos (one urban, one rural) to examine notions of urban-ness/rural-ness on the linguistic perception of a feature from Asturian Spanish (a contact variety in Spain) and found that the Spanish variant was heard more with the urban cosmopolitan photo. Implied ethnicity is perhaps the most studied social factor influencing speech perception; these studies tend to use speaker photos to suggest different ethnicities (Babel and Russell 2015; Chappell and Barnes 2023; Gutiérrez and Amengual 2016; Kutlu 2020; Rubin 1992; Staum Casasanto 2010), resulting in different evaluations of accentedness, comprehensibility, or social qualities (like religiousness).

Especially relevant to the present paper are studies that have analyzed how implied nationality affects speech perception. For example, Niedzielski (1999) found that Detroit listeners who were presented with a ‘Canadian’ label heard more raised diphthong /aw/ than listeners with a ‘Detroit’ label, even though the raised variant is common on both sides of the border, showing that the labels activated social stereotypes that attribute this pronunciation to Canadians. Similarly, national labels (Carter and Callesano 2018; Hay et al. 2006a), stuffed animals (Hay and Drager 2010), and negative/positive information about a nation (Walker et al. 2018) have been shown to affect linguistic and social perception. For example, Carter and Callesano (2018) found that the inclusion of national labels (Colombian, Cuban, Peninsular Spanish) affected Miami listeners’ perceptions of a speaker’s family wealth and salary, indicating that social stereotypes about different countries influenced socioeconomic judgements about speakers, even with a label–input mismatch.

A recurring finding from perception studies is that the relationship between linguistic form and social meaning has a “multiplicity and indeterminacy of indexical relations” (Johnstone and Kiesling 2008, p. 5). For example, in examining the social perception of monophthongal /aw/ as an index of localness in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Johnstone and Kiesling (2008) found that those who produce the least amount of /aw/ monophthongization were more likely to associate audio clips with the /aw/ monophthong with Pittsburgh while those who produced more /aw/ monophthongization did not perceive /aw/ monophthong as being from Pittsburgh. They posit that indeterminacy between linguistic forms and social meaning exists because of differences in lived experiences. Specifically, they state that

Numerous differences in lived experiences have been shown to create an indeterminacy between language and social meaning. For example, in examining the social perception of Spanish place names in Texas (with English phonology versus Spanish phonology), Regan (2022a) found that, while all listeners perceived Spanish place names with Spanish phonology similarly in some regards (e.g., as more respectful and friendlier), only Hispanic listeners perceived them as more educated, local to Austin, and older, while non-Hispanic listeners perceived them as non-local. In other words, the indexical meaning of place names in Austin was highly dependent on the listener’s background. As another example, after observing a gender effect in which only male listeners produced more local variants when presented with a stuffed animal associated with a sports rival, Hay and Drager (2010) suggest this result could be related to sports fandom, which serves as a strong marker of nationalism in New Zealand and interacts with gender (see also Drager et al. 2010).10 Previous perception studies of Costa Rican Spanish (Chappell 2016) and Andalusian Spanish (Regan 2022c) have found that female voices are judged more negatively than male speakers for using less institutionally prestigious features, and Chappell (2016, p. 372) suggests that awareness of the differential social payout for using local forms leads women to avoid them more than men.“It is people’s lived experiences that create indexicality. Since every speaker has a different history of experience with pairings of context and form, speakers may have many different senses of the potential indexical meanings of particular forms. Indexical relations are forged in individuals’ phenomenal experience of their particular sociolinguistic worlds.”(Johnstone and Kiesling 2008, p. 29)

One difference in life experience that warrants more research is that of bilingualism. In exploring attitudinal differences between U.S.-born bilinguals and Spanish-dominant Mexican listeners toward monolingual Mexican and bilingual heritage speech, Chappell (2021b) found that Mexican listeners “exhibited an in-group preference for the Mexican speakers’ Spanish”, while also taking a more “critical tone” in highlighting perceived “incorrect” aspects of the heritage Spanish speakers’ Spanish (Chappell 2021b, p. 153). The U.S.-born bilinguals, on the other hand, valued both Mexican and U.S.-born voices. As Chappell (2021b) indicates, the Mexican listeners demonstrated a more hierarchical view based on language, using Spanish as a proxy for status and education, while U.S.-born bilinguals saw Spanish as serving more of a “communal, familial, and cultural role” (p. 154). Perhaps one of the only studies to examine differences in the lived experiences of L2 listeners is that of Chappell and Kanwit (2022), who examined L2 Spanish listeners’ social evaluation of sociophonetic variation (coda /s/ as [s] and [h]). They found that advanced L2 Spanish listeners were capable of acquiring the indexical values of phonetic variants in their second language, especially those that had previously taken a phonetics course and participated in study abroad in a coda-/s/ aspirating region. In addition to examining the effect of language ideologies on social perceptions, the present study extends this last line of work, exploring how the differences in lived experiences between L2 and heritage listeners impact their perception of language varieties.

2.2. Language Ideologies in Sociolinguistic and Language Attitude Studies

Linguistic anthropologists have long examined language ideologies (Kroskrity 2004; Irvine and Gal 2000; Schieffelin et al. 1998; Woolard 1998, 2008; Woolard and Schieffelin 1994), or people’s “beliefs, or feelings, about languages as used in their social worlds” (Kroskrity 2004, p. 498), and Milroy (2004) and Woolard (2008) have called for language ideologies to have a more prominent role in sociolinguistics. One such ideology that has been frequently studied from a qualitative perspective is the monoglossic language ideology (Silverstein 1996; Lippi-Green 2012; Fuller and Leeman 2020; Leeman 2004), which we use here to refer to the notion that monolingual varieties are valued as “more correct” than bilingual varieties due to their lack of contact with another language. By default, such an ideology is not an additive but rather a deficit bilingual perspective.11 It is worth noting, however, that ideologies are plural (Kroskrity 2004) and many times overlapping. The notion that a monolingual variety is “more correct” than a bilingual variety due to lack of contact also overlaps with a standard language ideology (Lippi-Green 2012; Milroy 2001; Milroy and Milroy 1999), which Lippi-Green (2012, p. 67) defines as “a bias towards an abstracted, idealized, homogeneous spoken language which is imposed and maintained by dominant bloc institutions, and which names as its model the written language, but which is drawn primarily from the spoken language of the upper middle class”. This ideology is based heavily on the notion of correctness. As Milroy (2001, p. 535) indicates, “when there are two or more variants of some word or construction, only one of them can be right. It is taken for granted as common sense that some forms are right and others wrong”. For example, the devaluing of a word such as la troca in bilingual U.S. Spanish in Texas (a linguistic borrowing from the English word truck, with phonological adaptation) as opposed to el camión or la camioneta (depending upon the dialect) is an example of the intersection of a monoglossic language ideology and a standard language ideology. While such a monoglossic language ideology12 will be examined within the bilingual context of Texas, this ideology can operate anywhere there exists language contact.

Several studies have examined language attitudes of bilingual U.S. Spanish that reflect such a monoglossic language ideology. These studies have found that, although Mexican-Americans have positive attitudes toward remaining bilingual for both communicative and identity purposes (Mejías and Anderson 1988; Galindo 1995; Rangel et al. 2015), features of bilingual speech, such as accented English (Ryan and Carranza 1977) or code-switching (Rangel et al. 2015), have been shown to elicit less favorable evaluations than monolingual practices. Riegelhaupt and Carrasco (2000) found that the use of just a few features of bilingual Spanish were generalized by monolingual speakers to label the speaker as uneducated or of low social status. Furthermore, Goble (2016) and Tseng (2021) found that third- and second-generation U.S. Spanish speakers, respectively, tend to feel linguistic insecurity (see also Martínez and Petrucci 2004) when speaking Spanish with older generations who are viewed as having “native-like” Spanish, and this insecurity is further intensified by familial teasing. Self-perceptions of linguistic abilities may affect heritage speakers’ interactions with Spanish monolinguals and/or Spanish-dominant speakers as well (Guerrero-Rodríguez 2021).

The internalization of monoglossic language ideologies that create linguistic insecurity for bilingual U.S. Spanish speakers has also been attributed in part to socialization in the education system (Leeman 2012), in which more value is given to L2 bilingualism than heritage language bilingualism13 (Beaudrie and Loza 2023; Valdés et al. 2003) or, alternatively, to monolingual Spanish as opposed to bilingual varieties of Spanish (Achugar and Pessoa 2009; Valdés et al. 2003). Other work (Lowther Pereira 2010; Loza 2019) has demonstrated that instructional practices disfavor U.S. Spanish. Research in this area has adopted a raciolinguistic perspective (Flores and Rosa 2015) to show that racialized speakers, such as Latinx speakers in the U.S., are often “perceived as linguistically deficient even when engaging in language practices that would likely be legitimized or even prized were they produced by white speaking subjects” (Rosa and Flores 2017, p. 628).

2.3. Research Questions

The current project examines implied nationality, which here serves as a proxy for perceived bilingual/monolingual status, to examine the role of monoglossic language ideologies in mediating the social meaning of bilingual Spanish in Texas in two different populations of listeners. The project was guided by two main research questions: (i) What is the effect of social information, namely whether a speaker is said to be from ‘México’ or ‘Texas’, on the social perception and linguistic evaluation of the speaker? and (ii) How do speaker and listener characteristics affect these social perceptions and linguistic evaluations? Most importantly, do L2 and heritage Spanish listeners differ in their evaluations?

3. Methodology

3.1. Stimuli

A modified matched-guise experiment (Lambert et al. 1960) was created with stimuli taken from informal sociolinguistic interviews, following previous studies (Campbell-Kibler 2007; Regan 2020, 2022b, 2022c). As noted by Campbell-Kibler (2007, p. 34), spontaneous speech sacrifices control of content, but also provides for more naturalistic data. To keep the content relatively similar between speakers, only clips from the sociolinguistic interviews that dealt with family traditions, holidays, and foods were included (see Appendix A for more information).

Eight Spanish-English bilingual speakers (four female, four male) produced the stimuli for the study. They were all pursuing undergraduate degrees at a large Texas public university, were between the ages of 20 and 24 (Mean: 21.6; SD: 1.2), and were all born in Texas with parents from Mexico. Thus, according to Silva-Corvalán’s (1994) notion of sociolinguistic generation, they would all be considered second-generation (G2). Participants were recorded with a Marantz PMD660 solid-state digital recorder and a Shure WH20XLR head-worn dynamic microphone with a sampling rate of 4.1 kHz (16-bit digitization). The sociolinguistic interviews were conducted by the first author14 in the sound-treated Sociolinguistics & Bilingualism Research Lab in the fall of 2018 and winter of 2019. The interviews ranged between 40 and 60 min and were conducted in Spanish, but participants were told that they should feel free to code-switch between languages whenever they wanted. The speakers were asked open-ended questions about their studies, professional future plans, their home city/town in Texas and what they liked about it, family traditions (holidays, birthdays, quinceañeras, etc.), traditional family foods, trips to visit family in Mexico, sports, and identity.

The first author selected two clips lasting between 8 and 12 seconds long from each participant. These clips did not contain any sections of code-switching into English or salient English influence to avoid confounds. Additionally, the selections avoided any repetitions or pauses. These clips were then presented to the first author’s colleague, a linguist who is a Mexican Spanish speaker with extensive Spanish language teaching experience within Texas and is thus familiar with both monolingual Mexican varieties and Texas bilingual varieties. She listened to each clip and provided her input on which sounded more fluid for the purposes of the project, and the audio file she selected (one per speaker) was incorporated into the study (see Appendix B). The final clips ranged from 8.51 to 12.23 seconds long (Mean: 10.67, SD: 1.45). Individual audio files were normalized for intensity (dB) in Praat (Boersma and Weenink 2019) using the Modify > Scale Intensity function15 in order to bring all sound files to an overall range of 65 to 70 dB.

3.2. Experimental Design

The eight audio files were uploaded into an online survey in Qualtrics (2005–2023). Following previous studies (Barnes 2015; Regan 2020, 2022a, 2022b, 2022c), two versions of the survey were created and branched so that each voice was only heard once by each listener. This helps to reduce the overall time of completion and voice recognition, as each speaker has a unique utterance. Each speaker (i.e., audio clip) was given a pseudonym (Natalia, María, Sofía, Rosa, José, Juan, Alejandro, Pedro). These specific names were selected because they are some of the most frequent names in Mexico (bbmundo 2017; W Radio 2017) and, by default, are also quite common among Spanish speakers in Texas. While the audio was the same for Versions A and B for each speaker, the two social guises varied based on implied nationality: “María from Texas sounds…” or “María from México sounds…”. The complete experimental design can be seen in Table 1. The audio files within each block were randomized and participants were shown the blocks in random order, such that some participants were presented with block 1 and then block 2, while others started with block 2 and then heard block 1.

Table 1.

Experimental design.

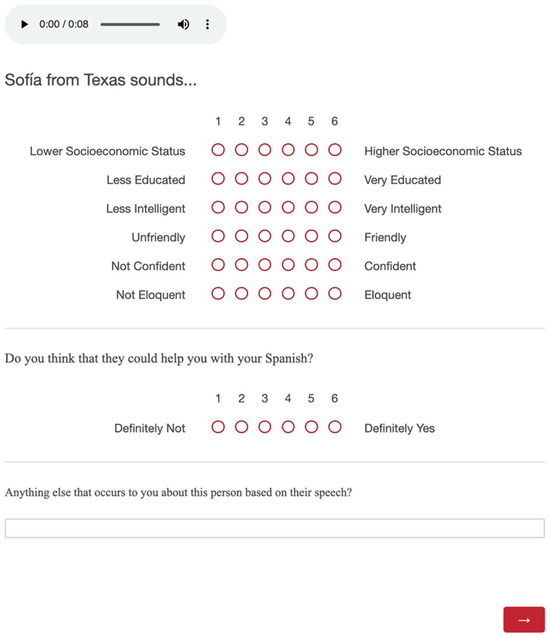

Upon consenting to the survey terms, participants (see Section 3.3 for listener participant recruitment) were asked to wear headphones and were told that they would hear eight short audio files ranging from 8 to 12 seconds long (see Appendix B for audio files). They were able to listen to each recording as many times as they liked and then responded to a series of questions to evaluated each speaker on a six-point Likert scale,16 as seen in Figure 1. The first six questions elicited evaluations of perceived social class, educational level, intelligence, friendliness, confidence, and eloquence17 of speech. Similar to Chappell (2021b, p. 143), although the recordings were in Spanish, the questions were presented in English, as the L2 listeners and most heritage listeners were English-dominant bilinguals. The final question (Do you think they could help you with your Spanish?) was designed to prompt reflection about whether or not listeners thought the speaker’s Spanish could serve as a pedagogical model. There was also an optional open-ended question for each voice. Finally, after completing all eight evaluations, listeners answered basic demographic questions about themselves, including their gender (male, female, self-identify [write-in]), age, home city, years lived in Texas, number of trips to Mexico, current Spanish class, and whether they identified as a Spanish heritage speaker or a second-language speaker of Spanish.

Figure 1.

Screenshot of survey questions for one audio file.

3.3. Implementation and Participants

All listener participants were undergraduate students currently enrolled in Spanish courses at a large public university in Texas. Over the course of 1.5 weeks in March of 2019, instructors of each upper-level Spanish course who agreed to have their classes participate brought their students to the department’s Language Lab & Research Center, where each participant had their own desktop computer and headphones. The survey link was placed on the Blackboard website of each course for the duration of the class period. Upon clicking the link, participants were asked to consent to the survey terms and confirm they were 18 years or older. Those who consented and confirmed their eligibility continued with the study, while skip logic took ineligible participants to the end of the survey, which prevented their participation. Responses were necessary to continue in the study, with the exception of the optional open-ended question (see Figure 1). Only completed surveys were used in the analysis.

There were 140 listeners (110 female, 30 male), ranging in age from 18 to 57 (Mean: 21.6, SD: 4.0), who participated in the experiment. They were roughly balanced by bilingualism type with 77 listeners who were L2 Spanish speakers and 63 listeners who were heritage Spanish speakers. At the time of participation, all were enrolled in third- (junior-level) and fourth- (senior-level) year Spanish classes. The majority (n = 132) of the participants were from Texas18 (Amarillo: 3, Austin: 16, Dallas/Fort Worth: 38, El Paso: 9, Houston: 18, Lubbock: 26, McAllen/Brownsville: 4, Midland/Odessa: 2, Presidio: 1, San Antonio: 13, Waco: 1, Wichita Falls: 1), with a few (n = 8) from other states (California: 1, “East Coast”: 1, Florida: 1, Mississippi: 1, New Mexico: 4).

3.4. Quantitative (Statistical) Analysis

All six-point Likert scales were centered on zero and then subject to a principal component analysis (PCA) and factor analysis in R (R Core Team 2023) to determine whether there were any correlations between the dependent measures and, if so, combine the correlated measures. The factor analysis revealed that the seven measures could be reduced to four factors, with three accounting for the majority of the variation (p < 0.01). Following Weatherholtz et al.’s (2014, p. 400) cutoff of 0.4 to determine whether a variable loaded onto a factor, the first factor strongly loaded for education (0.779) and intelligence (0.795). Thus, these two factors were combined to form “perceived education”. The second factor loaded for friendliness (0.635), confidence (0.805), and eloquence (0.556), which were then combined into a single factor entitled “perceived social affect”. A third factor only strongly loaded for socioeconomic status (0.861), and ability to help with one’s Spanish did not load strongly onto any of the three aforementioned factors. For this reason, both socioeconomic status and ability to help with Spanish were considered separately. As a result, there were a total of four continuous dependent measures: socioeconomic status, education (education and intelligence combined), social affect (friendliness, confidence, and eloquence combined), and ability to help with one’s Spanish.

Each dependent variable was subject to mixed-effects linear regression modeling using the lme4 (Bates et al. 2015) and lmerTest (Kuznetsova et al. 2017) packages in R with the random intercepts of speaker and listener. The independent variables tested in the modeling were (i) guise (‘México’ voices,19 ‘Texas’ voices); (ii) speaker gender (male, female); (iii) listener gender (male, female); (iv) listener city/town (border area, non-border area); (v) study abroad experience in a country where Spanish is the majority language (yes, no); (vi) frequency of trips to Mexico; (vii) course level (third-year, fourth-year); and (viii) listener bilingualism type (L2, heritage). Frequency of trips to Mexico was treated as a categorical variable of never, 1–5 times, 5–10 times, or more than 10 times. While it would have been ideal to treat this variable as a continuous measure, some listeners wrote comments (instead of raw numbers) such as “too many times to count”. Thus, we were unable to assign them an exact number of times and these listeners were coded as more than 10 times. After further analysis, we observed that both listener city/town and frequency of trips to Mexico demonstrated high collinearity with bilingualism type, as very few L2 listeners lived in border regions or had visited Mexico frequently. Thus, bilingualism type was included in the regression models while listener city/town and frequency of trips20 to Mexico were not. Model construction began with all independent variables and each social factor in interaction with guise, and non-significant factors were gradually removed. Three-way interactions that included bilingualism type and guise with all other social factors were also tested. Non-significant interactions with guise were removed from subsequent models, and in the case of interactions with more than two categorical levels, estimated marginal means (Lenth et al. 2018) were implemented to conduct post hoc analyses.

3.5. Qualitative Analysis

As previous researchers have stated (Baird et al. 2018; Campbell-Kibler 2010), some quantitative Likert-scale questions may not be able to uncover all language attitudes. For this reason, and following previous studies (Baird et al. 2018; Kirtley 2011; Nance 2013), the qualitative comments in response to “Anything else that occurs to you about this person based on their speech?” were subjected to word clouds. Rather than listing all of the words within the word cloud, the authors coded for any underlying themes. Thus, when possible, semantic themes were used in place of longer phrases, but only comments that were truly of the same semantic theme were combined. For example, comments related to quality of speech were deemed either “speaks well” or “speaks poorly” while observations related to speech rate were classified as either “speaks fast” or “speaks slowly”. To ensure objectivity in organizing these semantic themes, both authors separately coded and classified each comment. Given that the semantic category was more important than the individual word, all Spanish comments were translated into English semantic themes so that they would be represented in the same category for the word clouds. Of the possible 168 themes, the coding of both authors aligned on 120 specific descriptors, which constitutes a 71.4% agreement rate. The authors reviewed together the 48 semantic codes for which they did not have the exact same descriptors, most often due to a difference in synonyms. The finalized semantic themes for the ‘Mexico’ and ‘Texas’ voices were subjected to word clouds using the wordcloud() function in R. The size of the word/phrase in each word cloud is representative of its frequency, with larger words/phrases being more frequent in number than the smaller words/phrases.

4. Results

4.1. Quantitative Results

The results for each mixed-effects model are presented in Table 2, which displays the estimate, the standard error (SE), t-value, and p-value. Negative estimates indicate a lower rating than the reference level, while positive estimates indicate a higher rating than the reference level. Within the table, each model also has marginal R-squared (R2m) and conditional R-squared (R2c) values to assess how well the model explains the variation (Nakagawa and Schielzeth 2013). There were no significant main effects of guise or significant interactions with guise for perceived education (education and intelligence combined). As such, it will not be discussed further.

Table 2.

Summary of mixed-effects linear regression models for perceived socioeconomic status, perceived social affect, and perceived ability to help with one’s Spanish, speaker and listener as random intercepts, n = 1120 for each model. Reference levels are ‘Mexico’ for guise, L2 for listener bilingualism type, female for speaker gender, and female for listener gender.

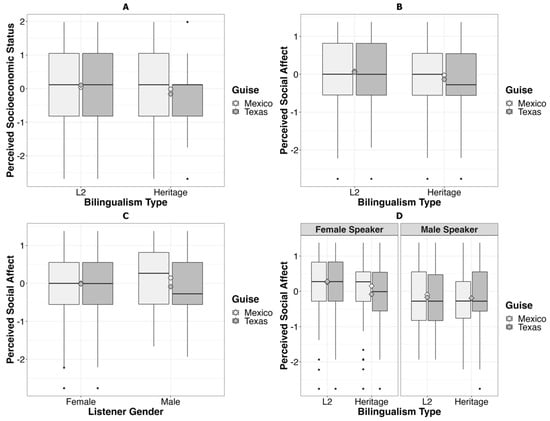

The model for perceived socioeconomic status revealed a significant interaction between guise and listener bilingualism type (see Figure 2A). Post hoc analyses revealed that there was no significant difference in guises for the L2 listeners (p = 0.324) but that heritage listeners perceived voices with a ‘Mexico’ label as being of a higher socioeconomic class than those with a ‘Texas’ label (p < 0.05). There was no significant difference in the evaluation of the ‘Mexico’ voices between L2 and heritage listeners (p = 0.617). However, heritage listeners perceived ‘Texas’ voices as being of a lower socioeconomic status than L2 listeners (p < 0.05).

Figure 2.

Guise by listener bilingualism type for perceived socioeconomic status (A); Guise by listener bilingualism type for perceived social affect (B); Guise by listener gender for perceived social affect (C); Guise by listener bilingualism type and speaker gender for perceived social affect (D).21 Note: bold horizontal black lines denote medians and the diamonds denote means.

The model for perceived social affect revealed two significant two-way interactions between guise and bilingualism type, on the one hand, and between guise and listener gender, on the other, as well as a significant three-way interaction between guise, speaker gender, and listener bilingualism type. Post hoc analyses revealed that L2 listeners did not perceive any significant difference (p = 0.28) between guises while heritage listeners perceived ‘Mexico’ voices as having higher positive social affect than ‘Texas’ voices (p < 0.01) (see Figure 2B). There were no significant differences between L2 and heritage speakers’ evaluations of ‘Mexico’ voices (p = 0.22) and ‘Texas’ voices (p = 0.06). Post hoc analyses found that female listeners (p = 0.53) did not evaluate speakers differently based on the guise, while male listeners perceived speakers with the ‘Mexico’ label as having more positive social affect than speakers with the ‘Texas’ label (p < 0.01) (see Figure 2C). The perception of social affect was not significantly different between male and female listeners for ‘Mexico’ (p = 0.18) and ‘Texas’ voices (p = 0.78). Regarding the three-way interaction, post hoc analyses indicate that L2 listeners did not perceive any significant difference in social affect between ‘Mexico’ or ‘Texas’ female voices (p = 0.57) nor between ‘Mexico’ or ‘Texas’ male voices (p = 0.07). While heritage listeners also did not perceive any significant differences in social affect between guises for male voices (p = 0.65), they perceived female ‘Mexico’ voices as having higher positive social affect than male ‘Mexico’ voices (p = 0.0006) (see Figure 2D).

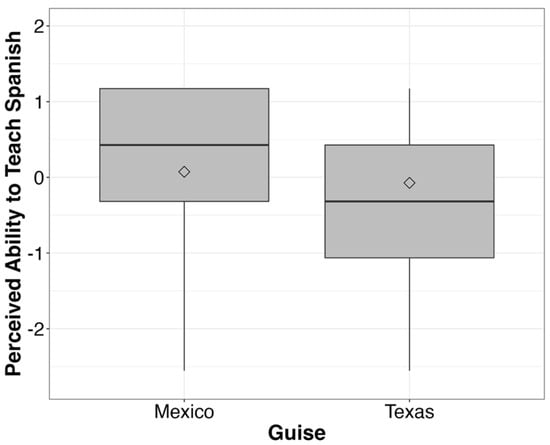

The model for perceived ability to help with one’s Spanish demonstrated a main effect of guise in which speakers with the ‘Mexico’ label were perceived as more able to help with one’s Spanish than those with the ‘Texas’ label (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Main effect of guise for perceived ability to teach Spanish. Note: bold horizontal black lines denote medians and the diamonds denote means.

To briefly summarize these results, the interaction between guise and bilingualism type for perceived socioeconomic status indicated that heritage Spanish listeners perceived ‘Mexico’ voices as being of higher socioeconomic status than ‘Texas’ voices, while L2 listeners did not perceive a significant difference in socioeconomic status between guises. There were three interactions for perceived positive social affect (friendliness, confidence, and eloquence). Speakers with ‘Mexico’ voices were evaluated as having higher social affect than those with ‘Texas’ voices, but only by heritage listeners. ‘Mexico’ voices were given higher social affect ratings only by male listeners. Additionally, for the three-way interaction, the only difference for guises was found among heritage listeners who evaluated female speakers with the ‘Mexico’ label as having higher social affect than those with the ‘Texas’ label. Finally, for perceived ability to teach Spanish, the main effect revealed that all listeners perceived speakers with the ‘Mexico’ label as more able to teach Spanish than those with the ‘Texas’ label.

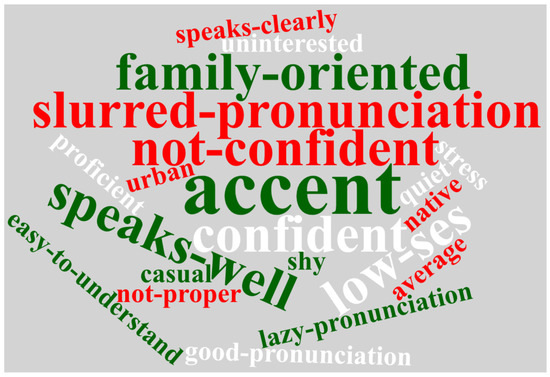

4.2. Qualitative Open-Ended Comments

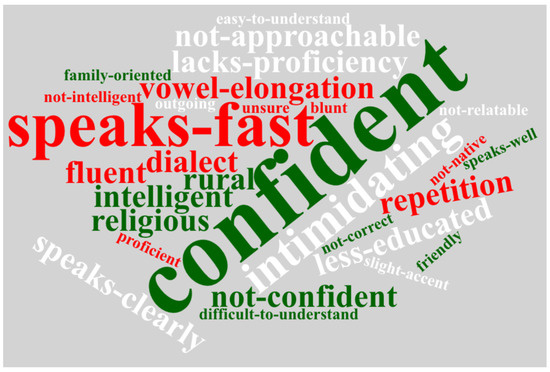

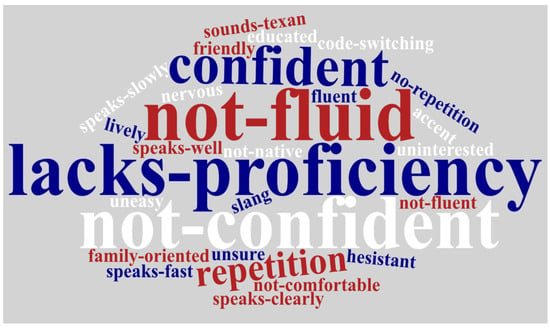

Given the differences in perception based on bilingualism type in the quantitative analysis, we separated comments for L2 and heritage listeners to examine any qualitative differences in perception between groups. Regarding the ‘Mexico’ voices, the L2 listeners’ most frequent comment was accent, followed by confident, not confident, family-oriented, speaks well, slurred-pronunciation and low socioeconomic status (SES) as seen in Figure 4. The word accent should be taken with caution as, without the full context of what listeners meant, it could imply they have a regional accent or possibly that they speak L2-accented Spanish. However, given that the listeners are L2 bilinguals, we can reasonably assume that they are referring to a Mexican-sounding accent. While confident and not confident stand in contradiction to one another, speaks well indicates a positive evaluation of speech quality. Slurred-pronunciation suggests that listeners had (or perceived that they had) difficulty in distinguishing words, which may indicate the perception of a fast speech rate. Finally, while not language-related, these listeners believe the speakers are family-oriented and of lower SES. Heritage listeners’ most frequent comment for the ‘Mexico’ voices was clearly confident, followed by speaks fast and intimidating, as seen in Figure 5. Of particular interest is that the descriptor intimidating was not used once by the L2 listeners. While there are differences between the two groups, overall, the comments are positive toward speech quality and speech rate.

Figure 4.

Word cloud of comments for ‘Mexico’ voices by L2 listeners.

Figure 5.

Word cloud of comments for ‘Mexico’ voices by heritage listeners.

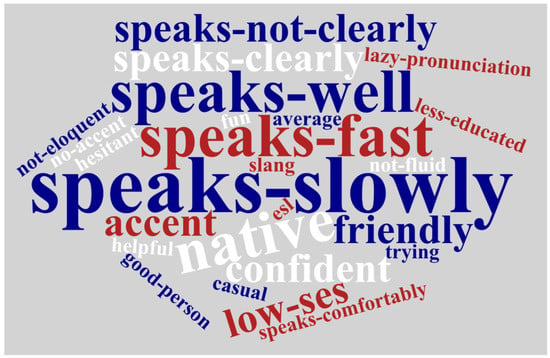

In terms of the ‘Texas’ voices, the L2 listeners’ most frequent comment was speaks slowly, followed by speaks fast, speaks well, native, and difficult to understand, as seen in Figure 6. The comments on speech rate (fast versus slow) appear to contradict one another, but then speaks well and native indicate an overall high evaluation of speech quality. For the heritage listeners, the most frequent words used to describe the ‘Texas’ voices were not fluid, lacks proficiency, and not confident, followed by confident and repetition, as seen in Figure 7. While the less frequent words demonstrate contradicting terms, the two most common descriptors are not only more negative toward speaking abilities than those used by the L2 listeners but also much more negative than the heritage listeners’ comments for the ‘Mexico’ voices. That is, the heritage listeners’ two most common descriptors for each guise stand in complete contrast: speaks fast and confident for ‘Mexico’ voices and not fluid and not confident for ‘Texas’ voices. The association of not fluid and speaks slowly with ‘Texas’ voices reflects the notion that monolingual speakers are more adept speakers of the language. For example, one full-length comment for “Pedro from Texas” was that he “sounds confident, but speaks rather slowly which I have noticed is a difference in speakers from Texas and Mexico. Speakers from Mexico typically are speaking faster and so that may cause them to be more intimidating” (P344,22 20-year-old female heritage speaker, Miami, FL).

Figure 6.

Word cloud of comments for ‘Texas’ voices by L2 listeners.

Figure 7.

Word cloud of comments for ‘Texas’ voices by heritage listeners.

In addition to the open-ended comment after each guise, there was also one final open-ended comment section at the end of the study for listeners to complete if they decided they wanted to add anything else. Excerpt 1 demonstrates that one listener (a second language learner) thought that all speakers were highly proficient in their speech.

However, others indicated that they heard or perceived differences between speakers ‘from Mexico’ and ‘Texas’, as seen in Excerpt 2.(1)They all seemed advanced in Spanish and all spoke with the same level on [sic] confidence and eloquence in my opinion. (P269, 21-year-old female L2 listener, Dallas, TX)

Another participant reflected on the fact that she believed knowing where the participants were from may have affected how she rated each speaker, as seen in Excerpt 3.(2)The accents and tones were different amongst Mexican speakers and non-Mexican speakers in my opinion. (P351, 20-year-old female heritage listener, Austin, TX)

One participant even acknowledged her own bias against bilingual Spanish due to her experience as a bilingual speaker, as seen in Excerpt 4.(3)I think that knowing where the person was from before listening to the audio clip may have influenced how I rated their Spanish, and I am not sure if that was purposeful but it is just something that came to mind. I tried not to let that influence me, but I can definitely see how it still might have affected my answers subconsciously. (P344, 20-year-old female heritage listener, Miami, FL)

This listener (P156) has internalized monoglossic and standard language ideologies that imply that her bilingual variety of Spanish is not as “correct” as monolingual varieties of Spanish due to San Antonio Spanish being “mixed”. As mentioned previously, there were no common morphosyntactic features of bilingual U.S. Spanish in the recordings. Thus, the inclusion of a speaker’s supposed nationality was enough social information to activate monoglossic and standard language ideologies, which were intensified in light of her own experience.(4)I think adding whether the person was from Texas or from Mexico influenced my expectation about how their speech should sound. I grew up being constantly corrected on my Spanish since San Antonio has very mixed Spanish, so I feel like I’ve been conditioned to think that those that have more of an accent tend to be less educated especially if their parents speak Spanish at home. (P156, 20-year-old female heritage listener, San Antonio, TX)

5. Discussion

5.1. Revisiting the Research Questions

In this section, we first discuss the results in relation to the research questions and previous literature and then the findings’ theoretical implications. Regarding the first research question (What is the effect of implied nationality on the social perception and linguistic evaluation of the speaker?), the most notable finding was the perceived ability to help with one’s Spanish: ‘Mexico’ voices were evaluated significantly higher than ‘Texas’ voices. It is important to remember that the audio guises were not digitally manipulated and that they were all produced by bilingual U.S. Spanish speakers, indicating that the social information of supposed monolingual/bilingual speech itself affected the differences in listener perception. This is the clearest indication of the pervasiveness of the monoglossic language ideology (Silverstein 1996; Pavlenko 2002; Lippi-Green 2012; Fuller and Leeman 2020; Leeman 2004, 2018), as an implied monolingual speaker is perceived to be more adept at teaching or explaining a language than an implied bilingual speaker. Such an ideology would increase the linguistic insecurity of bilingual speakers regarding their Spanish skills as somehow not being as adequate as those of monolingual speakers. This was evidenced by some of the qualitative comments from the heritage listeners (Excerpts 2–4), as well as the heritage listener word clouds.

In terms of the second research question (How do speaker and listener characteristics affect these social perceptions and linguistic evaluations?), listener bilingualism type interacted with guise for two of the dependent measures. More specifically, only heritage listeners perceived differences in socioeconomic status between guises, with ‘Mexico’ voices ranked as being of higher socioeconomic status than ‘Texas’ voices. This may demonstrate that heritage listeners are more acutely aware of the fact that in the U.S. context, the public discourse associates U.S. Spanish with a lower socioeconomic status (Urciuoli 1996, p. 26; Fuller and Leeman 2020, p. 85). Whether or not it relates to their own life experience, at-large public discourse may influence how they view (bilingual) U.S. Spanish speakers versus (monolingual) Mexican Spanish speakers. If we connect the results from the perceived socioeconomic status to those from the perceived ability to teach Spanish, we are able to observe what Zentella (2007, pp. 25–26) states: “Above all, distinct ways of being Latina/o are shaped by the dominant language ideology that equates working-class Spanish speakers with poverty and academic failure, and defines their bilingual children as linguistically deficient and cognitively confused (Zentella 2002)”.

The results for perceived positive social affect demonstrated additional interactions between bilingualism type and guise. Heritage listeners evaluated ‘Mexico’ voices as having higher positive social affect than ‘Texas’ voices, while L2 listeners did not perceive a significant difference between guises. This is interesting, as one may expect an in-group preference (Preston 1993) among the heritage listeners with regards to solidarity or perhaps tendencies similar to Chappell (2021b), where U.S.-born listeners demonstrated a broad conceptualization of community in which they positively evaluated both the Mexican and Mexican-American speakers. The three-way interaction would indicate that heritage listeners were more likely to perceive this difference in social affect between guises with female voices. Returning to the intersection of monoglossic and standard language ideologies, in which there is one variant or variety that is considered more correct or prestigious than the other, it may be the case that female speakers are evaluated more critically, at least by heritage listeners, for the use of any bilingual features or even—as in the current study—the mere implication of bilingual features. Previous studies (Chappell 2016; Gordon 1997; Eckert and McConnell-Ginet 1999; Regan 2022c) have found that women are judged more negatively than male speakers for using less institutionally prestigious features. Thus, because monoglossic and standard language ideologies would position bilingual varieties as less institutionally prestigious than monolingual varieties, this may explain why heritage listeners perceived ‘Mexico’ female voices as having more positive social affect than ‘Texas’ female voices. Regarding listener gender, only male listeners perceived differences in guises, evaluating ‘Mexico’ voices as having more social affect than ‘Texas’ voices. This finding should be taken with caution given there were only 30 male listeners in comparison to 110 female listeners.

5.2. Theoretical Implications

While evidence of a monoglossic language ideology was found among all listeners regarding one’s ability to teach Spanish, it is notable that, in the quantitative and qualitative analyses, there were differences in the evaluations between the L2 and heritage listeners. Specifically, heritage listeners evaluated ‘Mexico’ voices as being of higher socioeconomic status and having more positive social affect than ‘Texas’ voices, while L2 listeners generally did not perceive any other differences between guises. Although both groups are exposed to monoglossic and standard language ideologies, the findings of the current study indicate that heritage listeners may have more exposure to these ideologies than L2 listeners due to differences in lived experiences such as (i) contact with Spanish-dominant and monolingual Spanish speakers in and outside of the U.S., as well as (ii) experiences in the educational system.

While heritage speakers are not a monolith (Pascual y Cabo and Rothman 2012, pp. 451–52), it is important to consider that, in general, they have more contact with Spanish-dominant and/or monolingual Spanish speakers than L2 speakers, allowing for more internalization of monoglossic language ideologies. Previous studies have found that familial teasing for bilingual language features by more Spanish-dominant family members increases one’s linguistic insecurity (Carruba-Rogel 2018; Goble 2016; Tseng 2021), as monolinguals often expect bilinguals to behave like monolinguals (Riegelhaupt and Carrasco 2000). Tseng (2021) found this particularly true among second-generation speakers who were criticized for their pronunciation. She also found that second-generation U.S. bilinguals had more linguistic insecurity in the presence of Spanish-dominant speakers and therefore would avoid speaking. Thus, “purist language beliefs imposed deficiency identities on second-generation speakers regardless of actual language use” (Tseng 2021, p. 129). It is quite possible that these ideologies are being reinforced in interactions with members of their community, as shown by the listener from San Antonio in Excerpt 4. When the listeners first came into contact with these ideologies may play a role, given that the heritage listeners were all simultaneous bilinguals or early-sequential bilinguals while the L2 listeners were late-sequential bilinguals. As a result, L2 learners would have had significantly fewer years of exposure to these Spanish-specific attitudes in childhood, furthering differences in perceptions between the two groups.

Aside from the individual’s age of acquisition of Spanish, the educational system also has a role in reinforcing monoglossic language ideologies, cyclically recycling and reaffirming them. As Leeman (2012, p. 44) states, “school is a key site where young people are socialized into hegemonic value systems” such as “which kind of Spanish is ‘best’”. These language ideologies become “naturalized and come to be understood as common sense” (Leeman 2012, p. 46), such that “even individuals who are negatively affected by particular conceptions of language may embrace the very ideologies that subordinate them” (Leeman 2012, p. 44). Just as monolingual Spanish is granted a privileged status over bilingual varieties of Spanish (Achugar and Pessoa 2009; Valdés et al. 2003), it has been shown in multiple university23 contexts that more value24 is given to L2 bilingualism than to heritage language bilingualism (Beaudrie and Loza 2023; Valdés et al. 2003). For example, within a bilingual creative writing graduate program in El Paso, Texas, Achugar and Pessoa (2009) found that, while there were overall highly favorable attitudes toward bilingualism, local (bilingual) varieties of Spanish were viewed as inferior to monolingual Latin American varieties of Spanish. Similarly, in focus group interviews with professors and graduate instructors of Spanish departments across several universities, Valdés et al. (2003) observed that monolingual varieties of Spanish (Spain and Latin American) were considered the most correct varieties of Spanish and, while L2 Spanish was also viewed positively, the educators held the most negative views toward bilingual U.S. Spanish speakers. Valdés et al. (2003, p. 24) concluded,

These studies have demonstrated the role of the educational system in modeling the ideal variety of language as a monolingual one, which in turn leads to a devaluing of one’s own bilingual variety. Given the “paradox of Spanish” in the U.S. (Carter 2018), in which L2 bilingualism is valued more than heritage bilingualism, it would seem from the differences in perception based on bilingualism type that heritage speakers may be more exposed to such deficit ideologies in the educational system, making them more ingrained in their evaluations of language varieties, including their own.“[…] these departments are complicitous—although perhaps unconsciously—with the deep values and linguistic beliefs of American monolingualism that continue to view the United States as a profoundly English-speaking country. Both directly and indirectly, such departments transmit ideologies of nationalism (one language, one nation), standardness (a commitment to linguistic purity and correctness), and monolingualism and bilingualism (assumptions about the superiority of monolingual native speakers).”

L2 and heritage listeners may also differ in linguistic proficiency in Spanish, which could have influenced the participants’ evaluations.25 We may assume that—at least in terms of speaking and listening—the heritage listeners here are more advanced than L2 listeners given their exposure to a wide variety of monolingual and bilingual Spanish speakers. If this is the case, the L2 listeners may have simply perceived all speakers as more advanced than they were and thus did not feel comfortable assessing any potential differences based on status and/or social affect. As mentioned previously, Chappell and Kanwit (2022) found that only more advanced L2 listeners (as opposed to less advanced L2 listeners) were able to associate coda /s/ aspiration with a geographical distribution and social status, especially among those with phonetics courses and study abroad experience, respectively. However, even the advanced L2 listeners were not able to perceive the more nuanced social meanings that L1 listeners attribute to coda /s/ aspiration. Perhaps similar to their findings, if proficiency differences existed among the two groups, this may have led to L2 listeners not being able to (or feeling qualified to) evaluate speakers on more nuanced social properties.

Finally, building on Johnstone and Kiesling’s (2008, p. 25) idea of the “indeterminacy of relations between forms and meanings”, the current results reveal that, even when hearing the same linguistic input, the social interpretation of speech varies due to differences in listeners’ lived experiences (Johnstone 2011). While all participants in the study, L2 and heritage listeners alike, perceived the ‘Mexico’ and ‘Texas’ voices similarly for their ability to teach Spanish, the divergence in perceived socioeconomic status and social affect, as well as the qualitative comments, indicates a difference in the social meaning of bilingual varieties based on the listeners’ type of bilingualism. The lived experience of heritage listeners, which includes a greater exposure to monoglossic ideologies, may lead them to evaluate bilingual varieties differently from L2 listeners. What is of particular interest is that, in this experiment, the labels of ‘Mexico’ and ‘Texas’ were enough to activate associations within monolingual (or Spanish-dominant) and bilingual speakers. These results align with Regan’s (2022a, pp. 467–68) finding of two partially overlapping indexical fields for the perception of Spanish place names in Austin, TX, which varied based on listener ethnicity. While some social meaning was shared between Hispanic and non-Hispanic listeners, there were also differences between them, in which Hispanic listeners perceived Spanish phonology with Spanish place names just as local as English phonology, while non-Hispanic listeners26 only perceived the English phonology as local to Austin. As third-wave sociolinguistic studies continue to theorize the social meaning of linguistic variation (Hall-Lew et al. 2021), more emphasis should be placed on the role of differences in the lived experiences of listeners and speakers. That is, as Johnstone and Kiesling (2008, p. 29) state, researchers should pay “attention to the multiplicity and indeterminacy of indexical relations and to the way in which such relations arise in lived experience, [which] can lead to a more nuanced account of the social meanings of variant forms in a speech community”. Studies in bi/multilingual communities that only examine the social perception of linguistic variants in a broad, community-based sense may overlook this indeterminacy based on differences in lived experiences such as bilingualism type (L2, heritage), proficiency, trips to the country of family origin, cultural and emotional connection to Spanish, etc. Thus, these findings highlight the need for studies in multilingual settings to explore sociodemographic factors that may result in differential perceptions among bi/multilingual speakers and listeners. As the current study indicates, this applies not only to specific linguistic variants but entire language varieties.

It has been said that social perception is where linguistic variants and language varieties become associated with social meaning (Walker et al. 2014, p. 169). However, the current study demonstrates that commonly held language ideologies, such as monoglossic language ideologies (Silverstein 1996; Fuller and Leeman 2020; Leeman 2004) and standard language ideologies (Lippi-Green 2012; Milroy 2001; Milroy and Milroy 1999), can influence one’s social perception and linguistic evaluation even without any modification to the linguistic input. That is, language ideologies may activate indexical fields of social meaning related to language varieties without the presence of the variety itself. Given that language ideologies become an entrenched “common sense” notion (Leeman 2012, p. 46), a simple social prompt of being from ‘Mexico’ or being from ‘Texas’ affects how one is socially perceived and linguistically evaluated. This has real-life implications in which bilinguals are judged based on their linguistic status as a bilingual Spanish speaker and less so on their actual linguistic practices. This finding supports a raciolinguistic perspective (Flores and Rosa 2015; Rosa and Flores 2017) in the U.S. context in which U.S. bilingual Latinxs are viewed as having deficient forms of speaking. Rosa and Flores (2017, p. 628) indicate that “language ideologies associated with social categories produce the perception of linguistic signs”. That is, regardless of the actual linguistic input, ideologies associated with social categories (such as U.S. bilingual Latinxs) can shape how linguistic practices are perceived. Specifically, Rosa and Flores (2017, p. 628) indicate that these raciolinguistic ideologies produce “racialized language practices that are perceived as emanating from racialized subjects”. As such, the mere suggestion that a speaker is ‘from Texas’, that is, a U.S. bilingual Latinx, is enough to evoke negative social and linguistic meanings for listeners. From the results of the study, this appears to be more ingrained among heritage listeners and less so among L2 listeners. Consequently, there is much work to do in K-12 and university education to continue to show the value of bilingual varieties. Following a Critical Language Awareness approach (Leeman and Serafini 2016), L2 and heritage language curricula should actively include concepts of language ideologies to examine how they mediate the social perception of language.

6. Conclusions

Using quantitative and qualitative analyses, this study has demonstrated that (i) the social information of implied monolingualism/bilingualism influences listeners’ social perceptions of a speaker, reflecting monoglossic and standard language ideologies; and (ii) there exists indeterminacy between language and social meaning that varies based on differences in lived experiences between L2 and heritage listeners. Extending on Johnstone and Kiesling’s (2008) finding of indeterminacy between linguistic variants and meaning, the current study shows this also applies to (implied) language varieties, highlighting the role of language ideologies in mediating social perception.

Future studies would do well to include more metalinguistic questions in the experimental design, such as the quality of speech (speaks well/speaks poorly) and the speech rate (speaks slowly/speaks quickly). Additionally, future work should attempt to disentangle exactly how participants interpret implied nationality (‘Mexico’, ‘Texas’), as they may not truly be a proxy for a speaker’s monolingualism or bilingualism. For example, it is possible that some listeners based their evaluations on national stereotypes rather than notions of monolingualism versus bilingualism. Other listeners may assume that speakers from Mexico have had more years of formal education in Spanish while speakers from Texas have received most of their formal education in English, and therefore Mexican speakers are viewed as more qualified to teach Spanish based on this factor alone. Thus, future research should continue to tease apart these factors as they explore the role of language ideologies in the evaluation of speakers and their speech.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.R.; methodology, B.R.; formal analysis, B.R. and J.L.M.; writing—original draft preparation, B.R. and J.L.M.; writing—review and editing, B.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This investigation was funded by a 2018–2019 Texas Tech University Humanities Center Alumni College Fellowship.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Texas Tech University (IRB2017-973, approved on 24 January 2018).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available due to lack of permission to share.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Rossy Lima for providing her insights regarding the audio clips as well as feedback with the demographic questions, Geazul Hernandez and Chris Vasquez-Wright for their help in the CMLL Language Lab & Research Center in accommodating listener participation, and two anonymous reviewers for their suggestions. We are particularly indebted to the speaker participants for their time and for sharing their stories with us, to the listener participants for their time and insights, and to editors Whitney Chappell and Sonia Barnes for their detailed and insightful feedback. All errors remain our own.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Online Instructions for the Experiment

Instructions

Social psychology studies have demonstrated that one can infer a great deal about a person by briefly hearing her/his speech. To ensure a consistent topic, each speaker was interviewed in Spanish with the same question about Mexican/Mexican-American family traditions, holidays, and foods. You will hear clips of 8 different speakers who are from México or from Texas. Each recording is an 8–12 second clip taken from a larger conversation. Listen to the recording as many times as you would like. Respond to the question following each recording.

Make sure to be in a quiet place, to wear headphones, and to complete the study individually. The study lasts 10–12 minutes Don’t overthink it, go with your first instinct.

Appendix B. Stimuli Phrases

- Natalia: Toda mi familia viene a mi casa y vamos a misa el veinticuatro y miramos como una danza que siempre hacen en la misa. ‘All my family comes to my house and we go to mass on the 24th and we see a dance that they always do at the mass’.

- María: Sí sí, y luego siempre hay lumbre afuera, carne asada, ponche, tamales, de to- de todo, [risa], pero así nomás. ‘Yes yes, and then there’s always a fire outside, carne asada, punch, tamales of all kinds [laughter], but just like that’.

- José: Para el almuerzo, así como un burrito o, este: huevos rancheros, y luego para la cena, como tacos o tamales, a veces estamos en el invierno los tamales. ‘For lunch, like a burrito or um:27, huevos rancheros and then for the dinner like tacos or tamales, sometimes when we’re in the winter the tamales’.

- Juan: Pero por la Navidad es cuando mi mamá siempre saca el- el niño Dios, y pues nosotros ponemos a rezar, y hay tamales, menudo, de todo, y luego más comer y más risa. ‘But for Christmas is when my mother always takes out the baby Jesus, and well we begin to pray and there are tamales, menudo, and everything, and then more eating and more laughter’.

- Sofía: Pero tuvimos la quinceañera, la ceremonia, la fiesta, y como le dije, a mí me encanta bailar me encanta, encanta, entonces. ‘But we had the quinceañera, the ceremony, the party, and like I told you, I love dancing, I love, love dancing, so’.

- Rosa: Hay ponche de fruta, hay arroz con leche, chocolate [risa], de eso, sí sí, eh: hacemos mucho entonces en la Navidad hay más variedad en la comida. ‘There is fruit punch, there is arroz con leche, chocolate [laughter], yes yes, uh: we make a lot of that so at Christmas there is more variety in the food’.

- Alejandro: En Cuaresma, creo que, es un poco más, pescado solamente porque no puedes comer carne los viernes, entonces siempre es pescado. ‘In Lent, I believe, it’s a bit more, fish only because you can’t eat meat on Fridays, so it’s always fish’.

- Pedro: Pos, mi papá también cocina afuera, hace fajitas o hace como una discada para tacos, también unas enchiladas verdes también me gustan mucho, pero eso se hace con pollo. ‘Well, my father also cooks outside, he makes fajitas or makes a meat stew/roast for tacos, also some enchiladas verdes, also I really like them, but he makes them with chicken’.

Notes

| 1 | Here, social meaning is defined as “the set of interferences that can be drawn on the basis of how language is used in a specific interaction” (Hall-Lew et al. 2021, p. 3). |

| 2 | Here, linguistic information refers to the subtle changes in the audio input. Much of the sociolinguistic literature has focused on phonetic variation at the subsegmental, segmental, and suprasegmental levels. |

| 3 | Social perception is defined as the social characteristics that listeners attribute to speakers such as perceived educational level, friendliness, respectfulness, etc. |

| 4 | Here, we distinguish linguistic perception from linguistic evaluation, which is a more global or holistic evaluation (not-segmental specific) such as perceived accentedness (Rubin 1992) or speech intelligibility (Babel and Russell 2015). |

| 5 | A heritage Spanish speaker/Listener within the U.S. context is someone who grew up speaking or hearing Spanish at home while receiving their schooling in English (Valdés 2000). While this is one term, we could also refer to heritage Spanish speakers as U.S. Spanish speakers (see Erker and Otheguy 2021, pp. 199–200). |

| 6 | While we use the term “monolingual speaker” for the ‘Mexico’ guises, “Spanish-dominant speaker” could easily be employed as well. This acknowledges that in Mexico, there are L1 speakers of indigenous languages (L2 Spanish), as well as L1 Spanish speakers who are bi/multilingual. |

| 7 | The authors would like to state that a sequence of sociolinguistic waves does not indicate one wave is inherently better than the other, but rather each methodological approach depends upon one’s research questions. To this point, we strongly agree with Schilling (2013, p. 343), who states, “as far as we may have sailed over the first and second waves of variation to reach the third, we would do well to remember that the three “waves” are part of the same ocean, that elements of all three ‘waves’ of study were present from the outset of variation study (see Eckert 2005), and that the best current studies will approach the social meaning of linguistic variation from a range of perspectives […]”. |

| 8 | It has been shown that a combination of features—or the perception of a combination of features—can also be perceived as indexing a type of persona, such as what Inoue (2006) describes as “schoolgirl speech” for Japanese women. |

| 9 | Perceptual dialectology studies (Alfaraz 2002, 2014; Alfaraz and Mason 2019; Montes-Alcalá 2011) have examined the language attitudes of different language variants using the participants’ intuitions on questionnaires and/or “draw-a-map” tasks (Preston 1999). |

| 10 | This topic was explored in a production study by Drager et al. (2010) in which they found that while the condition (good information, bad information, no information of Australia) had an effect on New Zealanders’ speech, this interacted with sports fandom in which sports fans in the bad condition favored the Australian variant while non-sports fans in the good condition favored the Australian variant. Here, sports fandom was a stronger predictor than gender. |

| 11 | See Erker and Otheguy (2021) for an excellent example of quantitative evidence against the deficit bilingual perspective as seen in the U.S. context. |

| 12 | Of note is that while the focus here is on the monoglossic language ideology, there is also overlap with the standard language ideology in this context. |

| 13 | This has been referred to as the “paradox of Spanish” in the U.S. context (Carter 2018). |

| 14 | The researcher’s variety is Andalusian Spanish, which in theory could influence the bilingual Mexican Spanish speakers. However, given that Mexican Spanish is the dominant norm in West Texas, this is unlikely. |

| 15 | The rationale for a range instead of a fixed number is so that no audio clip was adjusted more than 5 dB (up or down) from the original recording. |

| 16 | Following previous studies (Campbell-Kibler 2007; Barnes 2015; Chappell 2016, 2018; Regan 2020, 2022a, 2022b, 2022c), an even number was selected to avoid neutral responses. |

| 17 | The first author was informed by several participants after the experiment that they were not very familiar with the term eloquent. Future studies should employ a synonym. |

| 18 | Of note, these cities refer to the greater metropolitan areas and surrounding towns from each city. |

| 19 | Similar to Niedzielski’s (1999) use of ‘Canadian’/‘Detroit’ voice, here we use ‘Mexico’/‘Texas’ voice in quotations, as all the speakers are truly bilinguals from Texas, but their voices were presented to listeners with two different nationality labels. |

| 20 | In future studies these two variables should be explored further with a larger sample size of listeners to examine whether differences in communities and frequency of trips to Mexico play a role in differences in perceptions among heritage listeners. |

| 21 | |

| 22 | This is the participant code (Excerpts 1–4 also provide participant codes). |

| 23 | This has also been found within the K-12 context in multiple school districts (see Clemons 2022). |

| 24 | Such ideological valuing of L2 Spanish over heritage Spanish is often reflected in the lack of institutional support for Spanish heritage programs (Beaudrie and Loza 2023). |

| 25 | We can only conjecture, as we did not provide any way to measure participant proficiency. |

| 26 | Of note, while this was the quantitative finding, Regan (2022a, p. 646) found that even among non-Hispanic listeners, there were individual listeners that demonstrated in the qualitative section that, due to their social contacts, they perceived Spanish phonology with Spanish place names to be just as local as English phonology, indicating the importance of lived experience in one’s perception. |

| 27 | “Este”, with vowel elongation of [e], here is a discourse marker (such as “uh” or “um” in English) to indicate to the interlocutor that the speaker is thinking of their next response and maintaining their speaking turn. |

References

- Achugar, Mariana, and Silvia Pessoa. 2009. Power and place: Language attitudes towards Spanish in a bilingual academic community in Southwest Texas. Spanish in Context 6: 199–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaraz, Gabriela G. 2002. Miami Cuban perceptions of varieties of Spanish. In Handbook of Perceptual Dialectology. Edited by Daniel Long and Dennis R. Preston. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, vol. 2, pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Alfaraz, Gabriela G. 2014. Dialect perceptions in real time: A restudy of Miami-Cuban perceptions. Journal of Linguistic Geography 2: 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaraz, Gabriela G., and Alexander Mason. 2019. Ethnicity and perceptual dialectology: Latino awareness of U.S. regional dialects. American Speech 94: 352–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, Brandon, Marcos Rohena-Madrazo, and Caroline Cating. 2018. Perceptions of lexically specific phonology switches on Spanish-origin loanwords in American English. American Speech 93: 79–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babel, Molly, and Jamie Russell. 2015. Expectations and speech intelligibility. The Journal of the Acoustic Society of America 137: 2823–33. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, Sonia. 2015. Perceptual salience and social categorization of contact features in Asturian Spanish. Studies in Hispanic and Lusophone Linguistics 8: 213–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, Sonia. 2019. The role of social cues in the perception of final vowel contrasts in Asturian Spanish. In Recent Advances in the Study of Spanish Sociophonetic Perception. Edited by Whitney Chappell. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 15–38. [Google Scholar]

- Bates, Douglas, Martin Mächler, Ben Bolker, and Steve Walker. 2015. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software 67: 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- bbmundo. 2017. Available online: https://www.bbmundo.com/comunidad/noticias/los-nombres-mas-populares-en-mexico/ (accessed on 23 January 2019).

- Beaudrie, Sara M., and Sergio Loza. 2023. Insights into SHL program direction: Student and program advocacy challenges in the face of ideological inequity. Language Awareness 32: 39–57. [Google Scholar]

- Boersma, Paul, and David Weenink. 2019. Praat: A System for Doing Phonetics by Computer. (Version 6.0.04) [Computer Program]. Available online: http://www.praat.org (accessed on 6 February 2019).

- Callesano, Salvatore, and Phillip M. Carter. 2019. Latinx perceptions of Spanish in Miami: Dialect variation, personality attributes and language use. Language & Communication 67: 84–98. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell-Kibler, Kathryn. 2007. Accent, (ING), and the social logic of listener perceptions. American Speech 82: 32–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell-Kibler, Kathryn. 2008. I’ll be the judge of that: Diversity in social perceptions of (ING). Language in Society 37: 637–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell-Kibler, Kathryn. 2010. Sociolinguistics and Perception. Language and Linguistics Compass 4: 377–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell-Kibler, Kathryn. 2011. The sociolinguistic variant as a carrier of social meaning. Language Variation and Change 22: 423–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carruba-Rogel, Zuleyma. 2018. The complexities in seguir avanzando: Incongruences between the linguistic ideologies of students and their familias. In Feeling It: Language, Race, and Affect in Latinx Youth Learning. Edited by Mary Bucholtz, Dolores Inés Casillas and Jin Sook Lee. New York: Routledge, pp. 149–65. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, Phillip M., and Salvatore Callesano. 2018. The social meaning of Spanish in Miami: Dialect perceptions and implications for socioeconomic class, income, and employment. Latino Studies 16: 65–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, Phillip. 2018. Spanish in U.S. language policy and politics. In The Routledge Handbook of Spanish as a Heritage Language. Edited by Kim Potowski. New York: Routledge, pp. 36–52. [Google Scholar]

- Chappell, Whitney, and Matthew Kanwit. 2022. Do learners connect sociophonetic variation with regional and social characteristics?: The case of L2 perception of Spanish aspiration. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 44: 185–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappell, Whitney, and Sonia Barnes. 2023. Stereotypes, language, and race: Spaniards’ perception of Latin American immigrants. Journal of Linguistic Geography 11: 104–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappell, Whitney. 2016. On the social perception of intervocalic /s/ voicing in Costa Rican Spanish. Language Variation and Change 28: 357–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappell, Whitney. 2018. Caribeño or mexicano, profesionista o albañil? Mexican listeners’ evaluations of /s/ aspiration and maintenance in Mexican and Puerto Rican voices. Sociolinguistic Studies 12: 367–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappell, Whitney. 2019. The sociophonetic perception of heritage Spanish speakers in the United States: Reactions to labiodentalized <v> in the speech of native and heritage voices. In Recent Advances in the Study of Spanish Sociophonetic Perception. Edited by Whitney Chappell. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 239–64. [Google Scholar]

- Chappell, Whitney. 2020. Perceptions of Spanish(es) in the United States: Mexican’s sociophonetic evaluations of [v]. In Spanish in the United States: Attitudes and Variation. Edited by Scott Alvord and Gregory Thompson. New York: Routledge, pp. 31–55. [Google Scholar]

- Chappell, Whitney. 2021a. Heritage Mexican Spanish Speaker’s Sociophonetic Perception of /s/ Aspiration. Spanish as a Heritage Language 1: 167–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappell, Whitney. 2021b. Mexican and Mexican-Americans’ perceptions of themselves and each other: Attitudes towards language and community. In Topics in Spanish Linguistic Perceptions. Edited by Luis A. Ortiz-López and Eva-María Suárez Büdenbender. New York: Routledge, pp. 138–60. [Google Scholar]

- Clemons, Aris. 2022. Benefits vs. Burden: A raciolinguistic analysis of world language mission statements and testimonios of bilingualism in the United States. Journal of Postcolonial Linguistics 6: 69–91. [Google Scholar]

- Drager, Katie, Jennifer Hay, and Abby Walker. 2010. Pronounced rivalries: Attitudes and speech production. Reo, Te 53: 27–53. [Google Scholar]

- Eckert, Penelope, and Sally McConnell-Ginet. 1999. New generalizations and explanations in language gender research. Language in Society 28: 185–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, Penelope. 2005. Three waves of variation study: The emergence of meaning in the study of variation. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Eckert, Penelope. 2008. Variation and the indexical field. Journal of Sociolinguistics 12: 453–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erker, Daniel, and Ricardo Otheguy. 2021. American myths of linguistic assimilation: A sociolinguistic rebuttal. Language in Society 50: 197–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, Nelson, and Jonathan Rosa. 2015. Undoing appropriateness: Raciolinguistic ideologies and language diversity in education. Harvard Educational Review 85: 149–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, Janet M., and Jennifer Leeman. 2020. Speaking Spanish in the U.S.: The Socio-Politics of Language, 2nd ed. Bristol: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Galindo, D. Leticia. 1995. Language attitudes toward Spanish and English varieties: A Chicano perspective. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences 17: 77–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goble, Ryan. 2016. Linguistic insecurity and lack of entitlement to Spanish among third-generation Mexican Americans in narrative accounts. Heritage Language Journal 13: 29–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, Elizabeth. 1997. Sex, speech, and stereotypes: Why women use prestige speech forms more than men. Language in Society 26: 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Rodríguez, Paola. 2021. Telecolaboración: Discutiendo sus efectos e implicaciones pedagógicas para hablantes de herencia de español. Doctoral dissertation, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA. [Google Scholar]