Abstract

The present study discusses typology and variation of word order patterns in nominal and verb structures across 20 Chinese languages and compares them with another 43 languages from the Sino-Tibetan family. The methods employed are internal and external historical reconstruction and correlation studies from linguistic typology and sociolinguistics. The results show that the head-final tendency is a baseline across the family, but individual languages differ by the degree of head-initial structures allowed in a language, leading to a hybrid word order profile. On the one hand, Chinese languages consistently manifest the head-final noun phrase structures, whereas head-initial deviants can be explained either internally through reanalysis or externally through contact. On the other hand, Chinese verb phrases have varied toward head-initial structures due to contact with verb-medial languages of Mainland Southeast Asia, before reinstalling the head-final structures as a consequence of contact with verb-final languages in North Asia. When extralinguistic factors are considered, the typological north-south divide of Chinese appears to be geographically consistent and gradable by the latitude of individual Chinese language communities, confirming the validity of a broader typological cline from north to south in Eastern Eurasia.

1. Introduction

Comparative studies of Chinese languages have become more widely practised in recent decades, particularly thanks to an increasing amount of information and data on understudied Chinese languages. Such valuable language descriptions supplement previous comparative works on Chinese dialectology (Yue-Hashimoto 1999; Li 2002; Cao 2008; Kurpaska 2010) and contribute to our better understanding of variation across Chinese languages. The advancement of such a diversity-based approach provides more evidence against the approach of “Universal Chinese Grammar” (Chao 1968, p. 13), which has been influential in Chinese linguistics for many decades (see also its criticism in Matthews 1999).

Such trends and advancement in the field of Chinese and Asian linguistics as well as linguistic typology in general have enabled further investigational attempts, which confirm an early observation by Hashimoto (1976) and strengthen the current consensus that variation in word order patterns of nominal and verb structures across Chinese languages largely results from language contact with non-Chinese languages. This emerging variation has been considered in a number of studies as evidence for areal diffusion in particular locations (Ansaldo 1999, 2010; Peyraube 2015; Szeto et al. 2018; Szeto 2019; Szeto and Yurayong 2021), particularly in Northwest China (Janhunen 2007; Sandman and Simon 2016) and South China (Li 2008; Matthews 2007; de Sousa 2015; Huang and Wu 2018; Szeto and Yurayong 2022).

Given the state of the art, the present study revisits earlier accounts of Chinese word order typology discussed in the context of the Sino-Tibetan family (Dryer 2003; LaPolla 2015). We aim to analyse diachronic changes of Sino-Tibetan word order based on synchronic data, naturally since diachronic data are only available for Chinese, Bodic and Burmo-Qiangic branches. For example, Nichols (1992) and Bickel (2015) have demonstrated that synchronic distributions of typological features can predictively provide information on diachronic trends and geographical clines as a directional implication for spread of languages and their features. Previously, variation and changes in the word order structure of Chinese have been discussed in a number of studies (e.g., Sun 1996; Xu 2006). However, Chinese has often been presented in publications as one name and one language possessing a single homogenous grammar contrasting with other more diverse Tibeto-Burman languages, leaving subtle differences present among individual Chinese languages unveiled. Unlike what has been usually done in previous studies, we adopt a diversity-linguistic approach which treats word order features of Chinese together with other Tibeto-Burman languages as equal datapoints without assumption or bias towards the hypothetical first level split of Proto-Sino-Tibetan into two major branches: Chinese vs. Tibeto-Burman (à Matisoff 2003; Sagart et al. 2019). The use of the term “Tibeto-Burman” in this study is therefore only for the purpose of referring to Sino-Tibetan languages which are not classified as belonging to the Chinese branch.

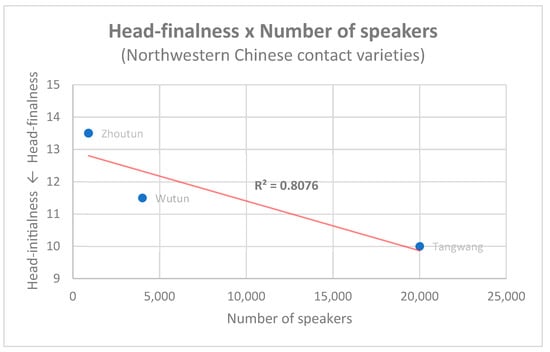

The aim of the current study is to tackle two main research questions, regarding the reconstruction of Proto-Chinese syntax and the role of variation and sociolinguistic factors in its change over time. By sociolinguistic factors, we refer to social factors related to language use in a broad sense, including population size, the number of L2 speakers and their speech communities. While these factors are usually not at the core of variationist sociolinguistics, they have received considerable attention in the work of sociolinguists interested in language change and language contact (e.g., Weinreich 1974; Thomason and Kaufman 1988). More recent works have also connected these factors to tendencies of typological change, including morphological complexity (e.g., Lupyan and Dale 2010; Sinnemäki and Di Garbo 2018). Although it is not possible to collect detailed sociolinguistic data on all the languages in our sample, the relevance of sociolinguistic factors for typological change have received so much attention in earlier research that we consider it necessary to bring out this issue as one of the factors which can explain our observations.

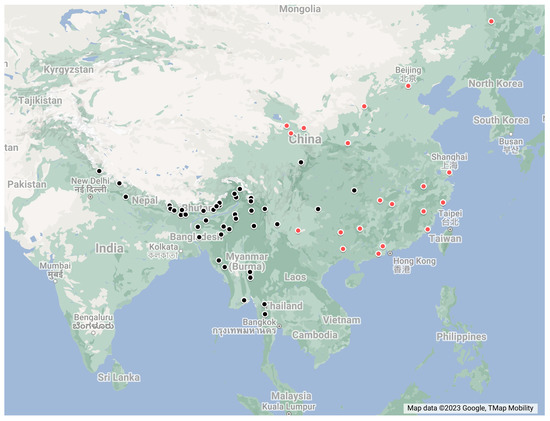

For the first research question, we explore diversity of word order structures across Chinese and the entire Sino-Tibetan language family through a variety sampling method developed by Miestamo et al. (2016). The principle is that one variety per one subbranch is taken in order to “display as much variety as possible in the linguistic realizations of the phenomena under investigation and to reveal even the rarest strategies or types of expression in the domain explored” (Miestamo et al. 2016, p. 234). The sample includes 20 Chinese and 43 Tibeto-Burman languages, geographically distributed across the Himalayas, their foothills in Southeast Asia and China as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Geographical coverage of the data: n = 63 (red = Chinese, black = Tibeto-Burman).

The data are collected from reference grammars and individual publications which provide synchronic (but sometimes also diachronic) descriptions and examples of individual word order features. Sociolinguistic data related to numbers of speakers and geographical locations of speech communities are also collected.

In terms of diachronic analysis to explain changes in word order typology of Sino-Tibetan languages, the current study uses a typological framework for both internal and external reconstruction methods. In practice, it means that we try to find an internal explanation first and will consider an external explanation only after the former reaches its limit, following a methodological practice of Thomason (2010). We challenge a holistic view that a protolanguage of any hitherto known language family must have been purely either the head-initial or head-final type without room for variation and hybridity.

As for the second research question, the data are quantitatively processed through coefficient of determination (R2, Wright 1921) for testing correlations between intralinguistic (a structural aspect of language) and extralinguistic (social and geographical) variables (see Section 3 for detailed description of the method). Concretely, we quantify variables by taking numbers of speakers and a geographical location (GIS coordinates) of any given speech community. The discussion pays special attention to a scenario of change initiated from sociolinguistically motivated free variation which further leads to the deviation of word order structure from the predominant head-final tendency of the Proto-Sino-Tibetan syntax, as is generally presented in the literature (see Dryer 2003; LaPolla 2015).

As a roadmap of the work structure, Section 2 provides relevant information and observations made in previous studies on word order and its related sociolinguistic factors in general and in Sino-Tibetan languages specifically. Section 3 describes data related matters and the method of analysis which is applied to the description of individual word order features in Section 4. The information and insights obtained from analysis of the data are used in the discussion of reconstruction and the explanation of directionality changes in word order from the Proto-Chinese and Proto-Sino-Tibetan stages, as shown in Section 5. Section 6 concludes the study with essential notes and suggestions for conducting further studies of the topic.

2. Background and Theoretical Framework

This section reviews significant observations of Chinese word order structure, as discussed in previous studies, and serves as a basis for building the research method for the present study (Section 3), as references for description of different word order features (Section 4) and as a theoretical framework for the discussion of reconstruction and the directionality of change in Chinese word order, motivated by multiple intralinguistic and extralinguistic factors (Section 5).

2.1. Typology and Directionality Change of Word Order

A nuclear element of syntax is labelled as “head” which interacts with its complements labelled as “dependent(s)”. A formalist approach assumes that a language has strictly consistent parameters for the order of head and its dependents (e.g., Jackendoff 1977; Lightfoot 1982; Chomsky and Lasnik 1993). However, natural languages are not always confined to such invariable parameters; instead, deviations can be observed, and the most we can say is that a language possesses a cross-category harmony governing tendencies of placing head before or after dependent(s) (e.g., Greenberg 1963; Hawkins 1983; Dryer 1992a). The present study will illustrate concrete evidence from Chinese and other Sino-Tibetan languages against the formalist idea of invariable parameters (as will be demonstrated in Section 4 and Section 5).

Throughout the entire work, we adopt a dichotomy widely used in the literature on syntax to describe a structure and directionality where head precedes dependent(s) as “head-initial”, e.g., Vietnamese năm nay [year this] ‘this year’, whereas another structure where head follows dependent(s) as “head-final”, e.g., Mongolian ene jil [this year] ‘this year’ (see also alternative terminologies, e.g., “right” and “left branching” in Dryer 1992a). To give some examples from neighbouring languages of Chinese, Tai-Kadai, Hmong-Mien and Austroasiatic predominantly use head-initial nominal and verb structures, while languages of the Altaic type, Japonic, Koreanic, Tungusic, Mongolic and Turkic, consistently conform with head-final directionality (see numerous chapters on word order features in Dryer and Haspelmath 2013 for a worldwide survey).

Due to its binary characteristics, when a change of head directionality occurs in word order, it tends to be abrupt or is even sometimes considered catastrophic (Lightfoot 1999, p. 105). From the opposing viewpoint, the directionality change may not occur catastrophically over a night, but the result is a predictable outcome of competition among existing variants which are available and competing in the speakers’ linguistic resources at a certain point before one has won over the others (see the variationist approaches to language change in Kroch 1989; Santorini 1993; Pintzuk 2017). In the current study, we adopt the latter variationist approach and will show varying degrees of directionality change in individual phrase and clause structures in Sino-Tibetan languages (see Section 4 and Section 5).

Regarding the predictability of changes in head directionality, we are always dealing with a finite set of possibilities, particularly when there are only binary options for directionality of word order, as discussed above. The attempt has been made to explain the directionality of word order in a typological framework by providing a relative chronology in which constituents and their related constructions shift their directionality faster. For instance, Greenbergian implicational universals (1963) have been applied in the discussion of hierarchy among different noun modification types in Hawkins (1983, p. 75), Dryer (1992b) and Croft (2003, p. 123), as shown in Table 1. The given constituent orders in each row represent word order profiles, six scenarios which are typologically expected in a language.

When they are put in an ordered rank below, we can apply their hierarchical order to conduct a diachronic prediction of which types tend to shift their directionality earlier.

Table 1.

The Prepositional Noun Modifier Hierarchy (modified from Hawkins 1983, p. 75; Dryer 1992b; and Croft 2003, p. 123): N = Noun; Quan = Quantifier; Dem = Demonstrative; Adj =Adjective; Poss = Possessor; and Rel = Relative clause.

Table 1.

The Prepositional Noun Modifier Hierarchy (modified from Hawkins 1983, p. 75; Dryer 1992b; and Croft 2003, p. 123): N = Noun; Quan = Quantifier; Dem = Demonstrative; Adj =Adjective; Poss = Possessor; and Rel = Relative clause.

| Type | Head-Initial Structures | Head-Final Structures |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | NQuan & NDem & NAdj & NPoss & NRel | – |

| 2 | NDem & NAdj & NPoss & NRel | QuantN |

| 3 | NAdj & NPoss & NRel | QuantN & DemN |

| 4 | NPoss & NRel | QuantN & DemN & AdjN |

| 5 | NRel | QuantN & DemN & AdjN & PossN |

| 6 | – | QuantN & DemN & AdjN & PossN & RelN |

Quantifiers → Demonstratives → Adjectives → Possessors → Relative clauses

According to the proposed hierarchy, quantifiers being at the higher surface of noun phrase structure tend to shift their directionality first whereas relative clauses at a deeper structural level would be resistant and the last among the noun phrase constituents to shift their position. However, this postulation based on the noun phrase modification hierarchy is not necessarily valid universally across languages of the world (as will be shown in Section 5.3), but it can serve as a starting point for the prediction of syntactic change, which utilises a predictive power of the typological approach to language change (Greenberg 1957, p. 77; Jakobson 1958, p. 528). The Chinese and Sino-Tibetan data discussed in the present study will contribute further to the improvement of such a predictive tool.

When it comes to the extension of directionality changes, the effects may apply at different levels of syntactic structure in different rates. For instance, it has been discussed in diachronic syntax literature that subordinate clauses tend to be more conservative and therefore can preserve older patterns better than main clauses (Bybee 2001). This assumption is applicable, for example, to West Germanic languages in which main clauses have shifted to the verb-medial pattern (1a), while subordinate clauses still retain the Proto-Germanic verb-final pattern (1b).

| Dutch (Indo-European) | |||||||||

| (1) | a. | Ze | spreken | geen | Chinees. | ||||

| 3pl | [speak.3pl | no | Chinese] | ||||||

| ‘They do not speak Chinese.’ | |||||||||

| b. | Het | is | jammer | dat | ze | geen | Chinees | spreken. | |

| it | be.3sg | pity | quot | 3pl | [no | Chinese | speak.3pl] | ||

| ‘It is pity that they do not speak Chinese.’ | |||||||||

A similar explanation has also been applied to trace the verb-initial structures inherited from Proto-Austroasiatic, which are retained in subordinate clauses of modern Austroasiatic languages, although they may have shifted to verb-medial or verb-final patterns due to contact and may vary in terms of how extensively the retention of the verb-initial structures still applies across the grammatical system (Jenny 2015, 2020). This assumption and related observations, which Chinese and other Sino-Tibetan languages provide evidence for (see Section 5.2), are useful also for the current study which conducts a syntactic reconstruction of Proto-Chinese and beyond by also paying attention to differences in the word order patterns of main vs. complex clauses.

2.2. Word Order Typology of Chinese and Sino-Tibetan Languages

In linguistic typology, Chinese and Sino-Tibetan languages are generally regarded as belonging to a head-final type of language, meaning that they tend to prefer word order with the head following dependents. This view is largely based on the observation that verb-final is the predominant syntactic pattern among the majority of Sino-Tibetan languages, which typologically entails correlations with other head-final structures (as discussed in Greenberg 1963; Dryer 1992a). However, individual Sino-Tibetan languages show varying degrees of deviation from this baseline head-final tendency, with Chinese exhibiting significantly more variation and admixture of head-final and head-initial structures. It has been argued that this phenomenon is best explained by language contact and areal diffusion (as examined by Dryer 2003; Chappell et al. 2007; Szeto and Yurayong 2021).

As illustrated in Table 2, the noticeably non-harmonious profile of word order structures in Chinese languages is evident particularly in verb phrases due to their predominant verb-medial basic word order, unlike noun phrases which are largely head-final.

Note that this is a generalisation which does not take into account the entire subtle variation observed across Chinese languages (for more data and analyses on variation across Chinese, see e.g., Yue-Hashimoto 1999; Szeto 2019, and examples in Section 4).

Table 2.

General tendencies of word order features of Chinese languages (based on Chappell et al. 2007, p. 189).

Table 2.

General tendencies of word order features of Chinese languages (based on Chappell et al. 2007, p. 189).

| Head-Final Structures | Head-Initial Structures |

|---|---|

| Adjective → Noun | Verb ← Direct Object |

| Possessor → Possessee | Auxiliary Verb ← Main Verb |

| Numeral → Classifier → Noun | Verb ← Adverbial complement |

| Demonstrative → Classifier → Noun | Adposition ← Noun phrase |

| Relative Clause → Noun | Complementiser ← Sentence |

| Degree adverb → Adjective | |

| Standard of comparison → Adjective | |

| Adverb → Verb | |

| Adpositional phrase → Verb |

Previous discussions by Dryer (1992a, 2003) postulate that Chinese languages have more consistently preserved the original head-final structures in noun phrases, while verb phrases are affected by the assumed directionality change in basic word order from the verb-final to verb-medial pattern. However, other Sino-Tibetan languages, which retain the verb-final basic word order, also use the head-initial order for adjectival and quantity modifications as well as degree adverbs, all of which appear as head-final in Chinese languages. The situation is indeed fuzzier for other Sino-Tibetan languages as there are likewise a lot of hybrid phrase patterns (as discussed in LaPolla 2015), which makes it worth to compare them with Chinese in the present study, in order to shed light on the fact that the Sino-Tibetan syntax is far from being internally harmonious and homogenous. Many intralinguistic and extralinguistic factors have been responsible for head-dependent word order in the languages today (see further discussion in Section 5).

Coming to language contact issues, neighbouring languages to the north of Chinese, namely Tungusic, Mongolic and Turkic, consistently use head-final structures for all the features mentioned in Table 2 (as has been extensively discussed in Szeto et al. 2018; Szeto 2019; Szeto and Yurayong 2021). This is thought to have influenced the preference for a head-final tendency in northern Chinese languages, one of the components of a larger “Altaicisation” process occurring towards the northern zone of Chinese speaking areas, where language shift from a language of the Altaic type to Chinese has been continuously taking place during the past millennium (Hashimoto 1976; Janhunen 2007, 2012). On the contrary, a similar scenario for the head-initial tendency could have stemmed from neighbouring languages to the south of Chinese, namely Tai-Kadai, Hmong-Mien and Austroasiatic, which consistently use head-initial structures (Bennett 1979; de Sousa 2015; Szeto and Yurayong 2022). It remains disputable whether it ultimately was the northern or southern part of the Chinese dialect continuum which has changed from the Proto-Chinese word order patterns. Furthermore, the investigation of historical syntax of Chinese with evidence solely from Archaic Chinese may also be biased towards several specific varieties of Chinese (as will be discussed in Section 2.3).

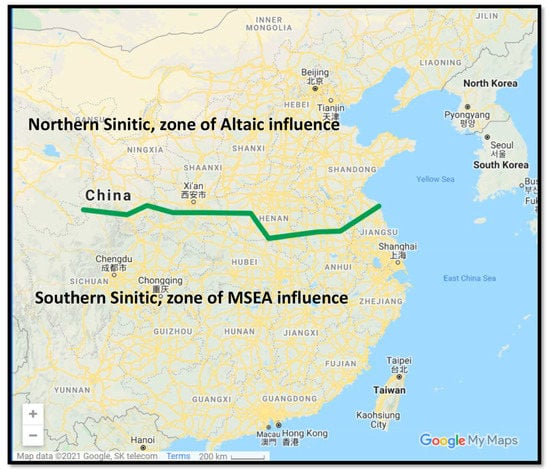

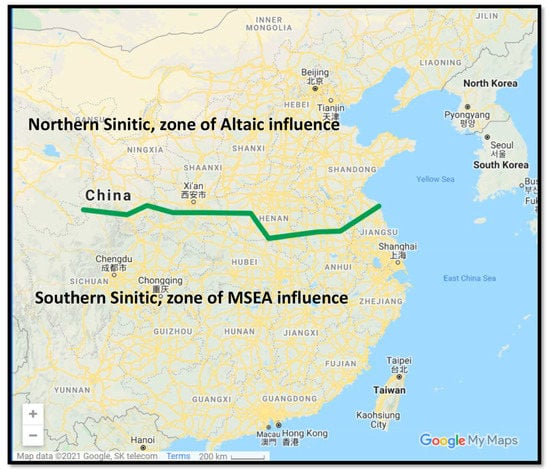

Despite uncertainty in the directionality of changes in Chinese, what has been agreed upon among Chinese contact linguistics scholars is that the role of language contact is certainly considerable with regards to both the north and the south. Based on the contact explanation, we can draw the line along the Qinling Mountain–Huaihe River Line (see Szeto and Yurayong 2021), a boundary which is also frequently used in other biosciences and population sciences to distinguish the two major vegetation, climate and demographic zones of China (see e.g., Fang et al. 2002; Xie et al. 2004), as illustrated in Figure 2.

Furthermore, a more fine-grained classification of Chinese languages in terms of using a large set of word order features also identifies the transitional zone in between (Norman 1988; Chappell 2015; Szeto and Yurayong 2021), in which the preferred head-final tendency in the north and the head-initial one in the south are used interchangeably. The validity of the Qinling Mountain–Huaihe River Line will be discussed further in Section 5.4.

Furthermore, a more fine-grained classification of Chinese languages in terms of using a large set of word order features also identifies the transitional zone in between (Norman 1988; Chappell 2015; Szeto and Yurayong 2021), in which the preferred head-final tendency in the north and the head-initial one in the south are used interchangeably. The validity of the Qinling Mountain–Huaihe River Line will be discussed further in Section 5.4.

Figure 2.

The Qinling Mountain–Huaihe River line (Szeto and Yurayong 2021, p. 557).

2.3. Archaic Chinese Word Order

Moving from the typological to philological approach, studies on historical Chinese syntax are, unlike the majority of the world’s languages, possible thanks to somewhat sufficient documentation of early forms of Chinese, providing concrete diachronic data of word order structures. Despite a potential bias toward the dialects or sociolects of the text producers, the attested documents are useful in the sense that they confirm the non-harmonious word order profile of Chinese to be in place since the late-2nd millennium BCE. In this section, we deal with Archaic Chinese, a Chinese language form spoken from the Shang dynasty during the 14th–11th centuries BCE to the Warring States period during the 5th–2nd centuries BCE (see also the complete periodisations in Sun 1996; Chappell 2001; Aldridge 2013).

As discussed in Section 2.2, Chinese languages consistently show a head-final tendency in noun phrase structures where possessors and modifiers precede head nouns, a pattern which largely applies also to Archaic Chinese (Aldridge 2015a), as in (2).

As in modern Chinese languages, modifiers are often attached to head nouns with a linker, a demonstrative 之 ‘that’ in the Archaic Chinese case. Likewise, relative clauses precede the head noun, and the two constituents are linked by the demonstrative 之, as in (3).

When there are multiple modifiers in a noun phrase, there is at least evidence for demonstratives preceding quantifiers, as in (4).

Interestingly, the use of classifiers was not attested in the Archaic Chinese sources (Peyraube 1991), but the order was consistently head nouns in the final position, as ‘these three gentlemen’ in (4).

| (2) | 先 | 王 | 之 | 道 |

| former | king | that[link] | way | |

| ‘ways of the former kings’ (Analects, Xue’er, Aldridge 2013, p. 44) | ||||

| (3) | 避 | 世 | 之 | 士 |

| avoid | world | that[link] | scholar | |

| ‘scholar who avoids the world’ (Lúnyǔ Wēizǐ, Aldridge 2015a, 3b) | ||||

| (4) | 願 | 君 | 去 | 此 | 三 | 子 | 者 | 也。 |

| desire | lord | dismiss | [this | 3 | gentleman] | det | nmlz | |

| ‘(I) hope your lordship will dismiss these three gentlemen.’ (Hánfēizǐ 36, Aldridge 2015a, 4b) | ||||||||

The use of prepositions, meanwhile, has been attested since the Archaic Chinese period when locational and dynamic verbs were already grammaticalised and used in the preverbal position, such as 於 ‘(in)to’ (< ‘to go’), 在 ‘in, at’ (< ‘to be in’) and 從 ‘from’ (< ‘to follow’), as can be seen in (5).

Typologically speaking, prepositions should be more common among head-initial languages and can be considered a secondary innovation in head-final Chinese languages, supplementing a more typical postpositional phrase based on relational nouns, such as 上 ‘top’ and 面 ‘side’, a strategy which is still productive in modern Chinese languages and other Sino-Tibetan languages (see concrete examples in Section 4.3).

| (5) | 孝文 | 帝 | 從 | 代 | 來。 |

| Xiàowén | emperor | [from | Dài] | come | |

| ‘Emperor Xiàowén arrived from Dài.’ (Shǐjì Xiàowén běnjì, Aldridge 2015a, 6a) | |||||

In terms of the verb phrase, verb-medial basic word order has been attested since the beginning of literary Chinese language history. However, pragmatic variation due to dislocation of topic has also been attested since the Archaic Chinese period. Often, the topicalised lexical unit may be repeated with a resumptive pronoun, such as the demonstrative-derived 3rd person pronoun 之 in (6).

In any case, there are also instances of the verb-final pattern in some specific constructions, which correspond to equivalent constructions in other Sino-Tibetan languages and are thus viewed by several scholars as remnants of pre-Archaic Chinese syntax (e.g., Li and Thompson 1974; Feng 1996; Xu 2006). This concerns, for instance, non-in situ question word phrases (7) and negative clauses (8). As for objects in negative clauses, there is a diachronic observation that fronting of the object disappeared later towards the 1st century BCE, as contrasted between texts from the 5th century BCE (8a) and the 1st century BCE (8b) (Aldridge 2015a).

Some previous studies have argued that the reason for object fronting may be due to an information structure effect (Djamouri 1991), cliticisation of the object (Feng 1996) or a need to apply accusative case marking on the object (Aldridge 2015b). Given the lack of consensus on the factor(s) behind dislocation of the object, we maintain in the current study that pragmatic factors are significant for determining variation but are at the same time difficult to predict and judge from the ancient texts with the limited contexts given. In any case, we still consider it useful to discuss the order of direct object and verb in comparison with other Sino-Tibetan languages with a rigid verb-final pattern (see also an additional explanation in Section 3).

| (6) | 子路, | 人 | 告 | 之 | 以 | 有 | 過。 |

| [Zǐlù]top | person | tell | [3.acc]res | appl | have | error | |

| ‘Zǐlù, someone told him he made a mistake.’ (Mèngzǐ Gōngsūnchǒu shàng, Aldridge 2015a, 7) | |||||||

| (7) | 公 | 誰 | 欲 | 與 | ___? |

| 2sg | who | want | give | ||

| ‘Who do you want to give (it) to?’ (Zhuāngzǐ Xúwúguǐ, Aldridge 2015a, 9a) | |||||

| (8) | a. | 莫 | 我 | 知 | 也 | 夫! |

| none | [1sg | know] | nmlz | excl | ||

| ‘No one understands me!’ (Lúnyǔ Xiànwèn, the 5th century BCE, Aldridge 2015a, 18a) | ||||||

| b. | 莫 | 知 | 我 | 夫! | ||

| none | [know | 1sg] | excl | |||

| ‘No one understands me!’ (Shǐjì Kǒngzǐ shìjiā, the 1st century BCE, Aldridge 2015a, 18b) | ||||||

Regarding other verb phrase structures, there is a consistent division between head-final and head-initial patterns. Head-initial modal auxiliaries (9) and complement clauses (10) consistently occur since the Archaic Chinese stage. Meanwhile, locational adverbials and temporal adverbials may vary between the preverbal (5) and postverbal positions (9), with both being equally frequent (Aldridge 2015a). Preverbal adverbials likely stem from the grammaticalisation of locational and dynamic verbs, as discussed above.

| (9) | 天子 | 能 | 薦 | 人 | 於 | 天。 |

| ruler | [can | recommend] | person | [to | heaven] | |

| ‘The ruler can recommend someone to heaven.’ (Mèngzǐ Wànzhāng shàng, Aldridge 2015a, 5a) | ||||||

| (10) | 言 | 非 | 禮 | 義, | 謂 | 之 | 自 | 暴 | 也。 |

| speech | betray | Rite | Righteousness | say | [3.acc | self | injure | nmlz] | |

| ‘If his speech betrays the Rites and Righteousness, then (one) says of him that he harms himself.’ (Mèngzǐ Lílóushàng, Aldridge 2015a, 22) | |||||||||

As for comparatives, the head-initial construction with adjectives preceding standards of comparison linked by comparative markers 於 ‘to go (into)’ (11a) or 過 ‘to surpass’ (11b) has been attested in Archaic Chinese (Sun 1996, pp. 10–11).

Later, another head-final construction with standards of comparison preceding adjectives emerged in Middle Chinese (the 2nd century CE onwards), through functional extension from a lexical meaning of 比 ‘to compare’ in Archaic Chinese (12) to a comparative marker in Middle Chinese (Sun 1996, p. 39).

The Middle Chinese alternation is still productive in southern Chinese languages, while the head-final construction with 比 ‘to compare’ is the only pattern in northern Chinese languages (Sun 1996, p. 38; Ansaldo 1999, 2010; Chappell 2015). Interestingly, the head-final type is used across other Sino-Tibetan languages (see Section 4.3), so the Archaic Chinese head-initial construction with 於 ‘to go (into)’ and 過 ‘to surpass’ showed an early deviation from the head-final baseline tendency. At the same time, the preferred patterns in the present-day northern and southern Chinese languages align with those of their neighbouring Altaic languages in the north and Mainland Southeast Asian languages in the south, as discussed in Section 2.2.

| (11) | a. | 苛 | 政 | 猛 | 於 | 虎。 | |

| severe | government | [ferocious | comp | tiger] | |||

| ‘A severe government is more ferocious than a tiger.’ (Lǐjì, Sun 1996, p. 25) | |||||||

| b. | 由 | 也 | 好 | 勇 | 過 | 我。 | |

| Yóu | part | fond | [dare | comp | 1sg] | ||

| ‘Yóu is more fond of daring than I (am).’ (Lúnyǔ Gōng yě zhǎng, Sun 1996, p. 38) | |||||||

| (12) | 爾 | 何 | 曾 | 比 | 予 | 於 | 是? |

| 2sg | how | emph | compare | 1sg | to | 3sg | |

| ‘How (dare) you compare me to him?’ (Mèngzǐ Gōngsūn Chǒu Shàng, Sun 1996, p. 39) | |||||||

Through the discussion with evidence from Archaic Chinese in this section, we see that a non-harmonious profile of Chinese with hybrid word order is diachronically consistent. This observation has motivated the idea that Chinese was originally a syntactically hybrid language which likely has maintained the Sino-Tibetan head-final tendency to a certain extent especially in noun phrase structures but also acquired head-initial structures from neighbouring languages. The head-initial tendency may be subject to areal diffusion from the south, particularly Tai-Kadai and Hmong-Mien, which have been in contact with Chinese for several millennia and from which a significant number of groups have shifted their language to Chinese (see also DeLancey 2013 for the discussion on the mixed origin of Chinese). Though such sociolinguistic factors and demographic changes may also be responsible for the non-harmonious word order patterns in Chinese throughout its attested history, we speculate that extralinguistic evidence and related explanation may also contribute to the discussion of the word order typology of Chinese and its change from a broader perspective.

2.4. Sociolinguistic and Other Explanation to Language Change

In addition to linguistic reconstruction methods, we also consider the role of sociolinguistic factors in language variation and change. Social factors alone cannot determine variation in language structure, and they are often difficult to separate from inheritance. Nevertheless, several theoretical approaches have looked for a link between sociolinguistics and variation in structural features of languages (as discussed in Ladd et al. 2015). One of them is sociolinguistic typology, a research program initiated by Trudgill (2011, 2020). Sociolinguistic typology aims at bridging the gap between sociolinguistics and linguistic typology, which up until recently have been largely separate subfields of linguistics. Sociolinguistics has mainly focused on language-external factors that shape language use and cause variation (such as age, social class, gender, language policies), while linguistic typology has been more concerned about language-internal diversity (such as word order correlations). A key question in sociolinguistic typology is whether there are any systematicities regarding what types of linguistic structures are developed and maintained in different types of sociolinguistic environments. Sociolinguistic typology has looked at, for example, the role of community size (small vs. large), density of social networks (dense vs. loose), social stability (stable vs. instable), the degree of shared information in the language community (high vs. low) and degree of contact with neighbouring language communities (high degree of contact vs. isolation) in relation to the complexity of language structure.

Recent research on sociolinguistic typology has shown that population size, the number of native speakers (henceforth, L1 speakers) and the proportion of second language speakers (henceforth, L2 speakers) correlate with morphological complexity. By using data from World Atlas of Language Structures (WALS), Lupyan and Dale (2010) have shown that languages with a smaller number of native speakers tend to have more complex morphological systems than languages with a larger number of native speakers. Bentz and Winter (2013) have found evidence that the greater the proportion of L2 speakers in the speech community, the smaller the case system of the language. Sinnemäki and Di Garbo (2018) have argued that morphological complexity depends on both population size and the number of L2 speakers. Finally, Sinnemäki (2020) has studied the role of population size and the number of L2 speakers together with a language-internal factor, word-order, in predicting the number of cases in a language. His results suggest that both population size and the number of L2 speakers are important predictors of the number of cases in a language, either in complex interaction with word order or as an independent predictor together with word order (Sinnemäki 2020).

Research on sociolinguistic typology has also found some evidence that a large population size and a high number of adult L2 speakers can lead to the preference of analytic expressions instead of inflectional expressions. A case in point is the reflexive in Kuki-Chin and Bodo-Garo languages of Northeast India (DeLancey 2014). Proto-Tibeto-Burman originally had a middle reflexive suffix *-(n)si, which has been lost in both Kuki-Chin and Bodo-Garo subbranches. However, both subbranches have recreated new reflexive constructions, whose structures at least partially reflect the sociolinguistic contexts in which these languages are spoken. Kuki-Chin languages, spoken by small populations in isolated hill locations, have created an inflectional middle reflexive suffix -a, e.g., ka-a-thooŋ [1sg-refl-hit] ‘I hit myself.’. Contrary to Kuki-Chin, Bodo-Garo languages are spoken by large populations in the Assam Valley in Northeast India. They serve as lingua francas in the region and are therefore influenced by contact from large numbers of L2 speakers who are learning them as adults. Bodo-Garo languages use an analytic expression, an emphatic pronoun gau, to express reflexivity, e.g., bi-w gau-khwu aina-ao nai-dwŋ-mwn [3sg-subj self-obj mirror-loc see-real-pst] ‘He saw himself in the mirror’. One of the possible reasons why Kuki-Chin and Bodo-Garo languages are using different strategies for reflexive expression is that analytic expression is easier to learn for adult L2 speakers. Therefore, sociolinguistic factors such as population size and multilingualism shape the environment in which the language is learned and used, and this, in turn, can affect the language structure together with internal factors.

Apart from bilingualism, language attitudes and ideologies, language awareness and stylistic practice have been shown to be important in understanding language change (Rodríguez-Ordóñez 2019). While typologically similar languages tend to converge in language contact and typological distance tends to deter convergence (see Thomason and Kaufman 1988), in some contact situations the language attitudes of the speakers may override the effects of structural similarities or differences in the languages in question. In any case, research on attitudes and ideologies has been largely qualitative and difficult to quantify, so we do not include it as a variable in this study.

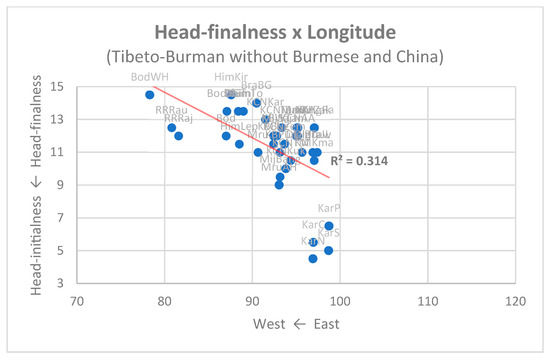

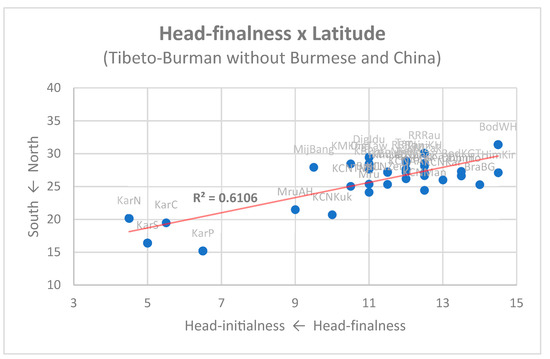

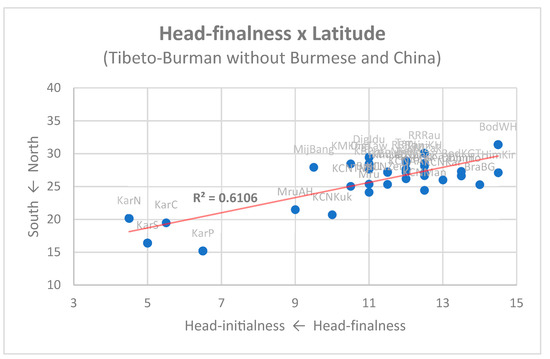

As the language sociology of a given community not only concerns its members but also its environment, we must not ignore the role of geographical factors such as climate and mobility. A pioneer work by Johanna Nichols (1992) and subsequent publications with various collaborators have identified typological clines which are the result of early human expansion prior to the formation of current linguistic groups or families and Sprachbünde. Most notably, the observation points to a stable incline or decline within selected language features from the west to the east of the northern hemisphere, especially across Northern Eurasia. However, such a large-scale approach has not been applied much in the quantitative explanation of linguistic diversity and variation of Sino-Tibetan languages spoken across the Trans-Himalayan zone. The current study operates on a working hypothesis developed by Szeto and Yurayong (2021) that Chinese speaking areas potentially illustrate the incline or decline of typological features in a stable and statistically significant manner. By integrating word order and geographical data, we seek to identify another north-to-south and east-to-west cline in East Asia and show that variation across Chinese, as discussed in previous studies and given in Section 2.2, are not necessarily divided sharply by the Qinling Mountain–Huaihe River line, but the decline of the head-final tendency has a significant correlation with extralinguistic factors (see Section 5.4).

We have seen in this section that both extralinguistic and intralinguistic factors are important in understanding language variation and change. The extralinguistic factors which have received most attention in studies of sociolinguistic typology are speaker population in terms of size and proportion of L1 and L2 speakers, as well as geographical factors. These factors have been shown to play an important role in predicting morphological complexity and patterns of language change. However, sociolinguistic factors alone cannot predict language change, and they must be studied together with diachronic analysis and language-internal factors, such as word order correlations discussed in Section 2.1, Section 2.2 and Section 2.3.

3. Data, Method and Results

The data for comparative analyses in the present study include 20 Chinese and 43 Tibeto-Burman languages, acquired from published reference grammars, grammatical sketches and analyses of individual constructions. The sample includes one language of each Sino-Tibetan second level subbranch as classified in Glottolog 4.6 (Hammarström et al. 2022). Several methods have been practised in linguistic typology with different degrees of control for genealogical and areal biases. For the present study, we adapt the variety sampling method developed by Miestamo et al. (2016), which takes one language per one branch. The reason for choosing this method is to capture general tendencies across Sino-Tibetan and to prevent an issue of oversampling, in which Chinese with the highest numbers of speakers and varieties would become unnecessarily overrepresented for the entire Sino-Tibetan family (see also discussion on advantages and issues within different sampling methods in Guzmán Naranjo and Becker 2022).

Since the milestone of the present study is to identify if there exist statistical correlations between the degree of directionality of change in word order and sociolinguistic factors, it is also crucial that sociolinguistic information such as numbers of speakers and geographical locations of linguistic varieties and communities under investigation are available for data accumulation. Information on genealogical status of individual variety in the Sino-Tibetan language family, number of speakers, geographical location in GIS coordinators and sources of data is given in Supplementary Material A. However, in reality, the data on word order features and sociolinguistic information may be insufficiently or fragmentally provided in the grammatical descriptions for some subbranches. This is the case for Gongduk, which unfortunately is excluded from the sample in terms of the quantitative analysis. In any case, Gongduk examples will still be mentioned in the qualitative analysis when they are relevant for the discussion.

In terms of word order features, the current study investigates 16 constructions involving different types of phrases and clauses, as given in Table 3.

The analysis takes into account the relation between the head and dependent of the constructions, thereby enabling a quantification of head-initial vs. head-final tendencies occurring in a given language.

Table 3.

Word order features under investigation.

Table 3.

Word order features under investigation.

| Feature | Construction | Head–Dependent | Domain |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Noun compounding | Noun[head]–Noun[modifier] | Noun (Section 4.1) |

| 2 | Adjectival modification | Noun–Adjective | |

| 3 | Adnominal possession | Possessee–Possessor | |

| 4 | Gender specification | Noun–Gender specifier | |

| 5 | Quantity modification | Noun–Numeral | |

| 6 | Deictic modification | Noun–Demonstrative | |

| 7 | Noun relativisation | Noun–Relative clause | |

| 8 | Degree adverb | Adjective–Degree adverb | Adjective (Section 4.2) |

| 9 | Comparative | Adjective–Standard of comparison | |

| 10 | Locational adverbial | Verb–Locational adverbial | Verb (Section 4.3) |

| 11 | Direct object | Verb–Direct object | |

| 12 | Predicative possession | Verb–Possessee | |

| 13 | Modal auxiliation | Verb[modal]–Verb[content] | |

| 14 | Adposition | Adposition–Noun | |

| 15 | Reported speech | Speech verb–Complement clause | |

| 16 | Negation | Negator–Verb |

It is worth remarking that direct objects can be prone to variation due to pragmatic factors, such as information structure (topic and comment) and text genres (narrative and dialogue), as discussed in Section 2.3 in connection to (6) and (8). A similar issue of pragmatically variable syntactic constructions, which causes some difficulties in terms of comparison and syntactic reconstruction, has been also discussed for Austroasiatic languages (see Jenny 2020). Despite such variation, it is still reasonable to consider this as a feature which is expected to appear as a head-initial construction in languages with more loosened tendency of verb-final structures.

In the process of data collection, queries are biased toward the head-final variant of a construction, and data are organised as binary values: 1 = head-final vs. 0 = head-initial. In cases where variation is reported in language descriptions, i.e., a language allows both head-final and head-initial variants of a construction either conditionally in specific contexts or unconditionally, the value is assigned as 0.5. These word order scores aggregated from different constructions under investigation have two uses. On the one hand, they serve as evidence for the generalisation of cross-family tendencies and a baseline for the reconstruction of Proto-Chinese and Proto-Sino-Tibetan syntax (see Section 5.3). On the other hand, they are used to identify whether there exist statistical correlations between the degree of word order variation and extralinguistic factors related to language sociology of given speech communities (see Section 5.4).

Supplementary Material B shows the results with head-finalness scores of each variety in the right-most column and family-average scores of each word order features in the bottom lines. As Chinese languages make up more than one-third of the sample, the feature average scores are accumulated separately from the rest of the Tibeto-Burman languages to prevent bias toward Chinese.

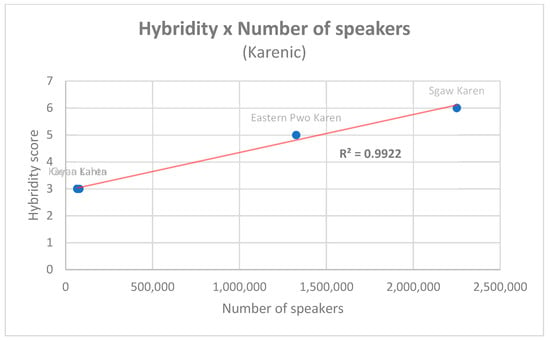

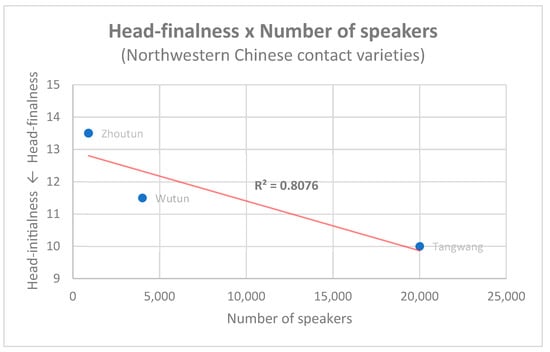

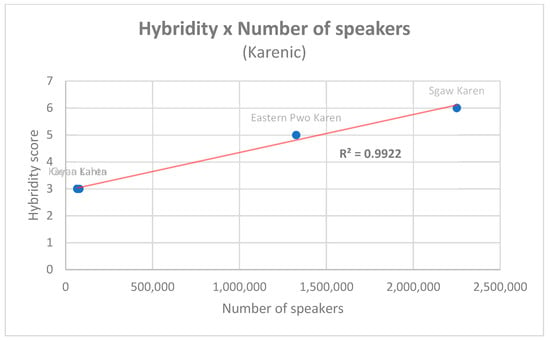

Several immediate observations can be made from Supplementary Material B, which will be followed up in more details in Section 4. Among Chinese, the range of variation is between 9.5 and 13.5, with Zhoutun being on the top. More strikingly, Karenic languages have significantly low overall head-finalness scores, ranging from 4.5 to 6.5. This corresponds to previous observations regarding a radical typological shift in Karenic which could have taken place already at the Proto-Karenic stage based on the observed distribution (see Kato 2019 and further observation and discussion in Section 4 and Section 5, respectively). At the same time, overall head-finalness scores are consistently high across Bodic, Dhimalish, Himalayish, Macro-Tani and Raji-Raute languages. Feature-wise, adnominal possession is consistently head-final across languages, followed by noun compounding, locational adverbial, relative clause and comparative constructions, in line with earlier typological investigations of variation across Chinese languages (Chappell et al. 2007, p. 189; Szeto and Yurayong 2021).

A closer look will be taken at individual word order features with concrete examples in Section 4, focusing on how they are generally realised across Chinese and Tibeto-Burman languages and whether some specific branches show significant deviation from the baseline.

4. Description of Word Order Variation across Sino-Tibetan Languages

This section provides examples of 16 word order features under investigation by primarily describing homogeneity or variation across Chinese languages and secondarily making references to Tibeto-Burman languages as a supplementary explanation of individual features. Table 4 contrasts the average head-finalness scores between Chinese and other Sino-Tibetan languages to support the description below in this section.

The results are largely in line with observations in the previous cross-Sino-Tibetan surveys by Dryer (2003) and LaPolla (2015) in that the head-initial tendency is present in several grammatical constructions, deviating from the head-final baseline. In particular, adjectival and quantity modification show a consistent opposition between Chinese, which prefers the head-final pattern, and Tibeto-Burman, which prefers the head-initial pattern, while the opposite applies for predicative possession, modal auxiliaries and reported speech. Obvious and subtle differences between Chinese and other Sino-Tibetan languages will be discussed below in connection with individual features. Unless the source is given for language examples embedded in text, particularly the Chinese ones, refer to the sources given in Supplementary Material A.

Table 4.

Average head-finalness scores for Chinese and Tibeto-Burman languages: 1 = head-final vs. 0 = head-initial.

Table 4.

Average head-finalness scores for Chinese and Tibeto-Burman languages: 1 = head-final vs. 0 = head-initial.

| Feature | Construction | Chinese | Tibeto-Burman | Domain |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Noun compounding | 1.00 | 0.95 | Noun (Section 4.1) |

| 2 | Adjectival modification | 0.98 | 0.36 | |

| 3 | Adnominal possession | 1.00 | 0.98 | |

| 4 | Gender specification | 0.35 | 0.06 | |

| 5 | Quantity modification | 0.93 | 0.20 | |

| 6 | Deictic modification | 0.98 | 0.71 | |

| 7 | Noun relativisation | 1.00 | 0.77 | |

| 8 | Degree adverb | 0.83 | 0.65 | Adjective (Section 4.2) |

| 9 | Comparative | 0.83 | 0.91 | |

| 10 | Locational adverbial | 1.00 | 0.86 | Verb (Section 4.3) |

| 11 | Direct object | 0.53 | 0.88 | |

| 12 | Predicative possession | 0.10 | 0.93 | |

| 13 | Modal auxiliation | 0.43 | 0.94 | |

| 14 | Adposition | 0.55 | 0.94 | |

| 15 | Reported speech | 0.08 | 0.71 | |

| 16 | Negation | 0.05 | 0.33 |

4.1. Noun Phrase Structures

Across Chinese and Tibeto-Burman languages, the most consistently head-final noun phrases are compounds and possession. In Chinese noun compounds, a modifier noun always precedes a head noun, e.g., Shanghai Wu jiéu di [wine shop] ‘hotel’, shiã̀ sḯ [fragrant water] ‘perfume’, and hú tsuo [fire car] ‘train’ (see also Arcodia 2007 for further subtypes of compounds). This is also a general tendency across Tibeto-Burman languages, but variation is, however, marginally found, e.g., Sgaw Karen plì tʰāˀ [string iron] ‘wire’ vs. pʰɛ̄ tʰū [necklace gold] ‘golden necklace’ (Kerbs, forthcoming), and Anong kʰɛn55 tʂʰɿ31 [vegetable juice] ‘vegetable soup’ vs. luŋ55 sɯ55 [stone mill] ‘grindstone’ (Sun and Liu 2009, p. 50).

Likewise, a head-final adnominal possessive construction with the possessor preceding the possessee is prevalent across Chinese and Tibeto-Burman, e.g., Kunming Mandarin ni3 nə1 tie1 [2sg link father] ‘your father’ and ɕio2ɕiɔ4 nə1 tsʰiɛ2tʂʰa3 [school link property] ‘school’s property’. Juxtaposition is a common strategy, while some languages may also optionally use genitive linkers, e.g., Mandarin de 的 and Cantonese ge3 嘅, which can be an instance of alienable possession in some sense (see e.g., Li 2018, pp. 54–57 for Yichun Gan). However, there is also an instance of head-initial adnominal possession reported in Raji with possessors marked by possessive suffixes, e.g., tsa-ŋ [son-poss.1sg] ‘my son’, and this pattern has likely been adopted from contact with an Indo-Aryan language (Khatri 2008, p. 22).

In contrast, there are several noun modifiers which are to a certain extent consistently placed before a head noun in Chinese but after a head noun in Tibeto-Burman, such as adjectives, gender specifiers and quantifiers. While prenominal adjectives and quantifiers are prevalent across Chinese languages, e.g., Yichun Gan san34 pun42 xao42 ɕy34 [three clf good book] ‘three good books’, northwestern Mandarin also allows postnominal adjectives as in Wutun and postnominal quantifiers as in Tangwang, Wutun and Zhoutun, e.g., Wutun hu yak-la~la-de-ge [flower beautiful-incomp~incompl-nmlz-clf] ‘beautiful flower’ and gek san-ge [dog three-clf] ‘three dogs’. This phenomenon has been explained for these varieties as a result of contact with Tibetan. For Tibeto-Burman, a diachronic scenario is the reanalysis of relative clauses (see Section 5.1). Interestingly, some other factors for variation are also reported in language descriptions or noticed in our observation.

In terms of semantics, when there are multiple adjectives in a noun phrase in Konyak, a language which allows the use of prenominal adjectives (prefixed by ə-) alongside canonical postnominal adjectives (suffixed by -pu), there is a tendency to place a quality adjective before the head noun but a quantity adjective after noun, e.g., yəwməy-pu ciŋ ə-ñu [beautiful-adj village adj-big] ‘a beautiful big city’ (Nagaraja 2010, pp. 75–76). From the syntactic perspective, meanwhile, East-Central Tangkhul Naga, a language which also allows free alternation between prenominal and postnominal adjectives, seems to prefer the prenominal adjectives in the contexts of predicative (13) and reduplication for plurals e.g., kʰra kʰra seiŋ [old old house] ‘old houses’, while the word order for adjectives in subject and direct object phrases remains more variable (see Devi 2011, pp. 134–40, 231, 234, 290–91).

Regarding phonology, Anong, which predominantly uses postnominal adjectives, may also allow the use of adjectives with two or more syllables in the prenominal position before a nominaliser u55, e.g., bɑ35bɑ31-tɕʰɛn31 u55 ʂɿ55vɑ31 [thin-dim nmlz book] ‘a thin book’ and sɿ31la33 u55 ɑ31tsʰɑŋ31 [good nmlz person] ‘a good person’ (see Sun and Liu 2009, p. 115).

| East-Central Tangkhul Naga (Kuki-Chin-Naga) | |||||

| (13) | a. | və | kəpʰə | ləsiɲəu | ə-ŋi-mə-ne. |

| 3sg.fem | [good | girl] | neg-be-neg-asp | ||

| ‘She is not a good girl.’ (Devi 2011, p. 256) | |||||

Specification of gender shows two patterns across Chinese languages, among which the northern varieties have a head-final pattern (14a), whereas the southern varieties have a head-initial pattern (14c). Interestingly, Changsha Xiang allows both orders as free alternation among different animal referents, first attested in Shímén Xiànzhì ‘Gazetteer of Shimen’ in 1875 (Wu 2005, p. 113). This may be largely due to the transitional identity of Xiang and its geography in the central zone of the Chinese dialect continuum (as discussed by Ho 1987; Norman 1988, p. 182; Szeto and Yurayong 2021, and in Section 2.2).

The head-final pattern is considered a Chinese construction, though our data show that it is consistently so only for Mandarin and Jin, while the other Chinese languages allow and use the head-initial pattern more frequently. The head-initial pattern is often considered to be a pattern borrowing from Mainland Southeast Asian substrate languages, most notably Tai-Kadai and Hmong-Mien (Yuan 1983, p. 10; Wang 1991, pp. 177–78; Pan 1991, pp. 287–88; Szeto and Yurayong 2021, p. 566). Such a preference is concretely reported for the Xiang dialect continuum, in which the northern part prefers the head-final pattern, which is considered to be prototypical for Chinese, while the southern part prefers the head-initial pattern, considered an innovation (Wu 2005, pp. 111–13). At the same time, Tibeto-Burman languages mostly use the head-initial pattern like in southern Chinese languages (Szeto and Yurayong 2022, p. 29), with the exception of the head-final pattern observed in Dhimalish languages and Kinnauri, as shown in the parallel examples in (14a) and (14b). The emergence of the head-initial structure in both Chinese and Tibeto-Burman can also be explained language-internally without unnecessary reference to a contact explanation, but rather to the nominalisation of the adjectival constituent (see further discussion in Section 5.1). As a side note, we also observe a conditioned alternation in Toto, as given in (15).

The rule is that Toto uses gender specifiers before animal (15a) and bird referents (15b) but after plant (15c) and human referents (15d).

| (14) | a. | gōng | jī | mǔ | jī | Beijing Mandarin |

| h’ióng | ji | tsï̀ | ji | Shanghai Wu | ||

| kən33 | tɕi33 | po13 | tɕi33 | Changsha Xiang | ||

| (s)kjo- | kukəri | manʈ- | kukəri | Kinnauri | ||

| male | chicken | female | chicken | |||

| ‘rooster’ | ‘hen’ | |||||

| b. | daŋkha | juhã | maini | juhã | Dhimal | |

| male | rat | female | rat | |||

| ‘male rat’ | ‘female rat’ | |||||

| c. | tɕie11 | kan11 | tɕie11 | m̩24 | Tunxi Hui | |

| tɕi33 | kən33 tsɪ | tɕi33 | po13 tsɪ | Changsha Xiang | ||

| kɪ21 | bo33 | kɪ21 | tɕie55 | Caijia | ||

| naga | -whaba | naga | -mama | Eastern Tamang | ||

| chicken | male | chicken | female | |||

| ‘rooster’ | ‘hen’ | |||||

| Toto (Dhimalish) | |||

| (15) | a. | dabe-kuŋwa | cabe-kuŋwa |

| masc-tiger | fem-tiger | ||

| ‘tiger’ | ‘tigress’ | ||

| b. | bale-keka | cabe-keka | |

| masc-chicken | fem-chicken | ||

| ‘cock’ | ‘hen’ | ||

| c. | muri | dabe | |

| chilli | male | ||

| ‘male chilli’ (a chilli which fails to bear fruits) | |||

| d. | yui-wa-poɟa | yui-wa-meme | |

| dance-agent-masc | dance-agent-fem | ||

| ‘male dancer’ | ‘female dancer’ (Basumatary 2016, pp. 81–83) | ||

Regarding the use of numerals and classifiers, some conditioned behaviour is observed in several languages which allow both prenominal and postnominal quantifiers. For instance, Eastern Tamang classifiers are obligatory when the quantifier precedes a noun (16b), but they can be omitted when the quantifier follows a noun (16a), the latter being reportedly a more frequent pattern in texts and normal dialogue (Lee 2011, p. 32).

At the same time, Amri Karbi generally uses fused forms of numerals attached to classifiers in the postnominal position, e.g., kampi i-jon [monkey one-clf] ‘one monkey’, but also sometimes allows the use of prenominal quantifiers for animate referents, e.g., isi i-jon a-kampi-so [one one-clf poss-monkey-dim] ‘one little monkey’ (Philippova 2021, pp. 129–30). The alternation is also reported for Garo mechik sak-sa [woman clf-one] and sak-sa mechik [clf-one woman] ‘one woman’ (Burling 2003, p. 97), and Zakhring dungpu nga [tree five] ‘five trees’ and nga simjong [five banana] ‘five bananas’ (Landi 2005, p. 56).

| Eastern Tamang (Bodic) | |||||

| (16) | a. | jha-gade | (gor) | som | mu-la |

| son-pl | [(clf) | three] | cop-npst | ||

| ‘(He) has three sons.’ [lit. There are three sons.] | |||||

| b. | gor | som | jha(-gade) | ||

| [clf | three] | son(-pl) | |||

| ‘three sons’ (Lee 2011, p. 32) | |||||

Other groups of noun modifiers with less consistent variation between head-final and head-initial patterns are demonstratives and relative clauses. On the one hand, demonstratives are prenominal across Chinese languages, e.g., Xi’an Mandarin tʂʅ55/u55/næ55 kɤ31 ʐən31 [this/that/yonder clf person] ‘this/that/yonder person’. On the other hand, there is variation between prenominal and postnominal demonstratives among Tibeto-Burman languages. Interestingly, for noun phrases with multiple modifiers in Toto, demonstratives occur consistently in the prenominal position, while adjectives may alter between the prenominal (17a) and postnominal positions (17b).

Such a phenomenon is not observed in Chinese languages because the position of adjectives is consistently prenominal (as discussed above).

| Toto (Dhimalish) | |||||||

| (17) | a. | i | dasiwa | ziya | u | haŋpuwa | ziya |

| this | black | bird | that | white | bird | ||

| b. | i | ziya | dasiwa | u | ziya | haŋpuwa | |

| this | bird | black | that | bird | white | ||

| ‘this black bird’ | ‘that white bird’ (Basumatary 2016, pp. 152–53) | ||||||

As for relative clauses, their position is always prenominal in Chinese languages, as shown in (18a). Note that Tunxi Hui speakers reportedly use more spontaneously a construction formed by a noun phrase with a demonstrative without a relativiser as in (18b) (Lu 2018, pp. 167–68).

The predominance of prenominal relative clauses also applies to Tibeto-Burman. There is, however, an exception in Karenic languages which predominantly use postnominal relative clauses for both subject (19a) and object relativization (19b). At the same time, the use of the prenominal pattern for objects is also reported for Eastern Pwo Karen under certain conditions (20).

Among other verb-final Tibeto-Burman languages, an unconditioned free alternation is also observed in several languages as indicated in Supplementary Material B. This is a consistent free alternation, for instance, in both Digarish languages as shown in the prenominal (21a) and postnominal patterns (21b).

| Tunxi Hui | ||||||

| (18) | a. | kə44 | ɕio11 | ka | ʦʰə42 | |

| [3sg | cook | rel] | dish | |||

| ‘the dishes which (s)he cooks’ | ||||||

| b. | ʨʰiʔ5 | ʨiɔn24 | mo31 | ka42 | ian44 | |

| [eat | dumpling] | that | clf | person | ||

| ‘the person who is eating dumplings’ (Lu 2018, p. 169) | ||||||

| Sgaw Karen (Karenic) | ||||||||

| (19) | a. | pɣākəɲɔ́ | lə́ | ʔə | hɛ́ | lə́ | pɣākəɲɔ́ | kɔ |

| person | [rel | 3sg | come | loc | Karen | country] | ||

| ‘the person who came to Kayin State’ | ||||||||

| b. | pɣākəɲɔ́ | lə́ | jə | tɔ̀ | ʔɔ̄ | nê | ||

| person | [rel | 1sg | hit | 3sg] | that | |||

| ‘that person whom I hit’ (Kato 2021, p. 356) | ||||||||

| Eastern Pwo Karen (Karenic) | |||||||

| (20) | jə | tháʊ | lə́ | dàʊ | phə̀ɴ | kháɴphài | nɔ́ |

| [1sg | ride | loc | room | inside] | shoes | that | |

| ‘those shoes which I wear in the room’ (Kato 2021, p. 355) | |||||||

| Tawra (Digarish) | |||||||||

| (21) | a. | hã́ | hɨbáŋ | bóyà | jyinaŋdõ̀ | kitab | haŋde | ||

| I.nom | [forest.dat | go] | cousin.dat | book.acc | give.hab.3sg | ||||

| ‘I give the book to (my) cousin who goes to the forest.’ | |||||||||

| b. | masáŋsyígwèlàŋ | bɨríhɨriso | cyá | katɨ́gharɨmso | |||||

| tree.fruit.pl.acc | [fall.recip] | she.nom | collect.recip | ||||||

| ‘She collected the fallen fruit.’ (Devi Prasada Sastry 1984, pp. 187–89) | |||||||||

4.2. Adjective Phrase Structures

Two constructions fall under adjective phrase: (1) degree adverb and (2) comparative. The use of an adverb ‘very’ varies across Chinese and Tibeto-Burman languages. Particularly, the northwestern Chinese languages predominantly use postadjectival degree adverbs, e.g., Zhoutun ɻɤ li uɤ [hot very] ‘very hot’. At the same time, some languages possess both preadjectival and postadjectival degree adverbs, as is the case for Dhimal preadjectival particle menaŋ ‘very’ and suffix -ŋ ‘very’ (King 2008, p. 53), and Amri Karbi preadjectival particle bohut (potentially borrowed from Indic) and suffixes -ad and -det ‘very’ (Philippova 2021, pp. 74, 136, 192, 218).

Moving to the comparative, we are only interested in comparatives of degree, not in comparatives of (in)equality which may show more variation (see, e.g., Zhou 2023 for such variation in Zhoutun). The majority of Chinese languages can use a head-final pattern with a standard preceding an adjective, as in (22a). However, the far southern Chinese languages, Yue and Pinghua in particular, also allow the use of an adjective before a standard (23a), as contrasted and paralleled with other Tibeto-Burman languages in (22b) and (23b).

This contrast has been characterized as areal diffusion from neighbouring Altaic languages in the north and Mainland Southeast Asian languages in the south (Ansaldo 1999, 2010). The idea is also supported by the predominant head-final tendency across Tibeto-Burman languages, with the exception only for Karenic languages which use adjectives before standards of comparison, as is shown in (23b).

| (22) | a. | a24 | pi31 kʰə44 | kə11 | Tunxi Hui | |

| b. | i | pa-sone | hubibe-ləi | Bugun | ||

| 1sg | comp 3sg | 3sg-comp | tall(er)-decl | |||

| (23) | a. | ŋoi33 | kɔ33 | kɔ33 | k’ui33 | Dancun Taishanese |

| b. | jə̄ | tʰó | -ɗɔ̀lí | sə̄ | Geba Karen | |

| 1sg | tall | comp | 3sg | |||

| ‘I am taller than him.’ | ||||||

Typically across the Chinese languages, adjectives can precede a standard of comparison, even in Chinese languages which predominantly use the head-final bǐ-construction when the comparison involves degree measurement (Wu 2005, p. 183; Li 2018, p. 94; Lu 2018, p. 238), as shown in the Xiang example (24b).

This pattern is considered by Yue-Hashimoto (2003, p. 111) as a reflex of the historical pattern, as discussed in Section 2.3 under (11). The study of Zhoutun comparatives also suggests that this pattern might be an instance of reinstalling the original head-initial comparatives (Zhou 2023).

| Changsha Xiang | ||||||

| (24) | a. | tʰa33 | pi41 | ŋo41 | kau33 | |

| 3sg | comp | 1sg | tall | |||

| ‘(S)he is taller than me.’ | ||||||

| b. | tʰa33 | kau55 | ŋo41 | san33 | li13 mi41 | |

| 3sg | tall | 1sg | [three | centimetre] | ||

| ‘(S)he is three centimetres taller than me.’ (Wu 2005, p. 183) | ||||||

4.3. Verb Phrase Structures

Unlike nominal phrase structures, Chinese languages use many head-initial patterns whereas most Tibeto-Burman prefer head-final structures. For instance, most Chinese languages generally place the direct object after the verb in their basic word order, while also allowing the opposite pattern for topicalisation (as discussed in Section 2.3 and Section 3). At the same time, the majority of Tibeto-Burman languages possess a verb-final basic word order, while several branches also allow placing the direct object after the verb, as is common for verb-medial Karenic and Caijia and less frequent in verb-final Zakhring and Mruic languages, as given in (25).

| Mru (Mruic) | ||||

| (25) | pariŋ | ca | ɯipʰum | kʰɔk |

| Paring | eat | mango | pst | |

| ‘Paring eats mango.’ (Rashel 2009, p. 146) | ||||

The position for possessee in predicative possession also shows a direct correlation with basic word order. Chinese languages place the possessee in the postverbal position due to their verb-medial basic word order and topic-type of predicative possession, i.e., possessor as topic (see Stassen’s 2009 typology of predicative possession). In any case, northwestern Chinese languages with the verb-final basic word order place the possessee before an existential verb, similarly to verb-final Tibeto-Burman languages. Interestingly the verb-medial Karenic languages can place the possessee before the existential verb, although the quantifier still follows the verb, as given in (26).

This might be an instance of archaism as a remnant of verb-final pattern in Karenic (see further discussion in Section 5.3). In any case, the use of verb-medial pattern for predicative possession is also reported for Sgaw Karen when the construction belongs to the with-type in Stassen’s (2009) classification (Kerbs, forthcoming), as given in (27a). This variant is considered by the informant as being more formal and poetic than the spoken variant with verb-final pattern given in (26) and (27b).

| Geba Karen (Karenic) | |||||

| (26) | sə̄ | ʃì | ʔɔ̀ | θó | wà |

| 3.poss | house | exist | three | clf | |

| ‘He has three houses.’ [lit. His three houses exist.] (Naw 2008, p. 129) | |||||

| Sgaw Karen (Karenic) | ||||||

| (27) | a. | jə | sē | ʔôˀ | [more common, spoken] | |

| 1sg.poss | money | exist | ||||

| b. | jə | ʔôˀ | dɔ̄ˀ | sē | [more formal, written, poetic] | |

| 1sg | exist | with | money | |||

| ‘I have money.’ (Kerbs, forthcoming) | ||||||

As for adverbials, the expression of location is generally preverbal across Chinese and Tibeto-Burman languages, as is shown in (28).

However, deviation is observed in Mruic languages which allow multiple clausal word orders, with the verb-medial pattern being more frequent (Rashel 2009, p. 160; Wright 2009, pp. 49–50), and crucially also alternation between preverbal (29a) and postverbal locational adverbials (29b). At the same time, Karenic languages consistently place locational adverbials after verbs (30) in accordance with their predominant verb-medial basic word order.

In any case, Chinese languages with verb-medial basic word order are homogenous in that they use both prepositions and postpositions. As discussed in Section 2.3, both are the results of grammaticalisation from locational or directional verbs to prepositions and relational nouns to postpositions, respectively, from the verb lã5-4 ‘to stay’ and the noun lai4 (<lai4pak7) ‘inside’, as shown in the Min example (31).

A similar phenomenon is also reported for Karenic, such as Eastern Pwo Karen lə́ dàʊ phə̀ɴ [LOC room inside] ‘in the room’ in (20), and Caijia tɯ21 tv̩24 tv̩33 [at yard upside] ‘in the yard’ (Lü 2022, p. 47). The observation from Chinese, Karenic and Caijia clearly points to a correlation between the verb-medial basic word order and prepositions (as discussed in Greenberg 1963; Dryer 1992a). At the same time, the tendency that relational nouns always follow the content noun also correlates with the general head-final tendency of noun compounding (as discussed in Section 4.1). In the northwestern Chinese languages, Tangwang and Wutun, meanwhile, postpositions are the only option because verbs always occur in clause-final position and cannot precede any adpositional phrases. In any case, the verb-final Zhoutun also marginally uses prepositions, e.g., iũ xuɤthã [along riverbank] ‘along the riverbank’ and iũ kɤ lu [along this road] ‘along this road’ (Zhou 2022, p. 106).

| Yichun Gan | ||||||||

| (28) | ȵi34 | ʦhoe213 | ko34 | xau42 | ko | tʰai213-21xoʔ | tʰuʔɕy34 | a. |

| 2sg | [loc | so | good | link | university] | study | intj | |

| ‘You are studying at such a good university!’ (Li 2018, p. 72) | ||||||||

| Hkongso (Mruic) | |||||||

| (29) | a. | pələŋkrum˦˨ | tʰaŋ˦˨ | hai˥ | aŋ˧ | ɬoi˧ | ra˦˨ |

| [Paletwa | side | from] | 1sg | return | come | ||

| ‘I come back from Paletwa.’ | |||||||

| b. | va˥ | kəjɨ˧ | ləmuk˧ | nam˦˨ | tʰaŋ˧ | ||

| bird | fly | [sky | village | at] | |||

| ‘The bird is flying in the sky.’ (Wright 2009, p. 63) | |||||||

| Kayan Lahta (Karenic) | |||||||

| (30) | ka˩jaŋʔ˥ | lwaŋ˩ | ɲɨ˧ | teɨŋ˥ | ba˩ | də˧ | tu˩ |

| Kayan | go | get | porcupine | clf | [in | forest] | |

| ‘The Kayan got a porcupine in the forest.’ (Naw 2013, p. 79) | |||||||

| Hui’an Min | ||||

| (31) | kau3 | lã5-4 | tshu5-3-lai4 | khun5 |

| dog | [at | house-inside] | sleep | |

| ‘The dog sleeps in the house.’ (modified from Chen 2020, p. 262) | ||||

In terms of verb morphology, word order of the modal auxiliary is surveyed by looking at the position of an ability verb ‘to be able’. Most Chinese languages head-initially place an ability verb such as 可以 before the main verb (32a), but some languages also head-finally use the postverbal auxiliary 得 ‘to get’ for ability as in (32b).

Paternicò and Arcodia (2023) discuss variation between the use of 得 in preverbal and postverbal position and show that the postverbal use is predominant in Cantonese with more versatile modal functions than in Mandarin, in which the postverbal use of 得 is declining, whereas the preverbal use remains common.

| Cantonese | ||||||||

| (32) | a. | lei5 | ho2 ji5 | daap3 | baa31si2 | heoi3 | man4 faa3 | zung1sam1 |

| 2sg | [can | catch] | bus | go | culture | centre | ||

| ‘You can take a bus (to get) to the Cultural Centre.’ | ||||||||

| b. | li1 | di1 | zi1 liu2 | m4 | seon3 | dak1 | gwo3 | |

| this | pl | information | [neg | believe | get] | pass | ||

| ‘These figures are not worth believing.’ (Matthews and Yip 2011, pp. 265, 278) | ||||||||

At the same time, northwestern Chinese languages place the suffixed ability verb clause-finally as predicate, similarly to verb-final Tibeto-Burman languages, as given in (33) and (34).

However, we find deviation in Mruic languages which place the ability verb before the main verb, as shown in (35). This pattern is similar to the use of preverbal 可以 ‘to be able’ in Chinese languages, as in the Cantonese form ho2 ji5 in (32a).

| Zhoutun | |||||

| (33) | tɤ | ŋɤ | tʂɯthũxua | itiãtiã | ʂuɤ=lɛ=lɔ. |

| part | 1sg | Zhoutun.vernacular | little | [speak=able=pfv] | |

| ‘I can speak a little Zhoutun vernacular.’ (Zhou 2022, p. 39) | |||||

| Bulu Puroik (Kho-Bwa) | |||||

| (34) | aʦɨ̀ | sã̀ʤo | apʰɔ̀ | ba-hí-rjaò-ʧa | ... |

| grandchild | Sanʤo | male | [neg-speak-able-pfv] | ||

| ‘Grandsons Sanʤo’s father doesn’t know to speak [Puroik] …’ (Lieberherr 2017, p. 188) | |||||

| Hkongso (Mruic) | |||||||||

| (35) | mu˥mai˦˨ | maʔ˥ | nin˥ | aŋ˦˨ | kəcəʔ˧ | aŋ˥ | no˧ | hai˧ | au˥ |

| cloud | subj | cover | 1sg | if | 1sg | [neg | able | shine] | |

| ‘If the clouds cover me, I cannot shine.’ (Wright 2009, p. 81) | |||||||||

Another feature related to verb morphology is negator, the order of which is predominantly preverbal in most Chinese languages as in (32b) and (36), as opposed to Tangwang and Zhoutun which also use postverbal negators in some contexts as in (37).

Although preverbal negators tend to be more common across Tibeto-Burman and the world’s languages (see Dahl 1979; Dryer 2013), there are also languages which only use postverbal negators as indicated in Supplementary Material B, such as in (38).

At the same time, some Tibeto-Burman languages may also use circumflexive negators, being on both sides of the negated verb (39). This type of language is assigned with 0.5 in Supplementary Material B.

As for negation, we also test whether negators and their order vary between main and subordinate clauses. This observation is a secondary finding which will be discussed in more detail with a diachronic analysis in Section 5.2.

| Linxia Jin | ||||||||

| (36) | tɕin11 zəʔ2 | pəʔ2 | xa35 | y42 | lie11, | t’iæ11 | tɕ’11 | lie11-21! |

| today | [neg | fall] | rain | part | sky | clear | part | |

| ‘Today it does not rain, it is sunny!’ (Wang 2007, p. 248) | ||||||||

| Zhoutun | ||||||

| (37) | tha | i=kɤ | ɻɤ̃ | sã=tɕĩ | xuɤ=pu=xɑ̃ | a. |

| 1sg | one=clf | person | three=jin | [drink=neg=down] | part | |

| ‘I cannot drink up three jin (of wine) alone.’ (Zhou 2022, p. 75) | ||||||

| Northern Tujia (Burmo-Qiangic) | |||||

| (38) | lai4 | nga2 | re2 | hu3 | ta1 |

| today | 1sg | wine | [drink | neg] | |

| ‘I will not drink any wine today.’ (Brassett et al. 2006, p. 132) | |||||

| Lepcha (Himalayish) | ||||||||

| (39) | hó | hryóp-pung | ʔân | mák-kung | gang-lá | taʔyu | ʔáre | ma-thop-ne |

| 2sg | cry-ptcp | and | die-ptcp | if-also | girl | this | [neg-get-neg] | |

| ‘Even if you cry or die, you won’t get this girl.’ (Plaisier 2006, p. 136) | ||||||||

Lastly, we also investigate word order in complex clauses, focusing on reported speech in which the order of the complement clause depends on the placement of a speech verb ‘to say’. In Chinese languages with the verb-medial basic word order, the complement clause always follows the speech verb, while the verb-final Chinese and Tibeto-Burman languages naturally place the complement clause before the speech verb, as contrasted in (40) and (41).

| Dancun Taishanese | ||||||||

| (40) | ni33 | kɔŋ55 | k’ui33 | hiɛŋ33 | ŋɔi33 | tiu32 | lɔi22 | lɔ55 |

| 2sg | say | 3sg | listen | [1sg | at.once | come | part] | |

| ‘You tell him that I am coming right away.’ (Yue-Hashimoto 2005, p. 392) | ||||||||

| Tangam (Macro-Tani) | |||||

| (41) | ami=de | kutuk=de | to-ma(ŋ)-ne=do | en-la | keta-duŋ |

| person=anap | [frog=anap | exist-neg-nmlz:subj=quot] | say-nf | look-ipfv | |

| ‘The man looked [into the hole in the tree], thinking that the frog might be in there.’ (Post 2017, p. 125) | |||||

At the same time, there are also verb-final languages such as Bangru, which besides the preverbal complement clause (42a) also allows the postverbal complement clause (42b).

Interestingly, when the complement part is built on a non-finite verb, it always precedes the speech verb ‘to say’ as in (42c), revealing the original head-final pattern at a deeper syntactic level (see Devi and Ramya 2017, p. 48, and further discussion on subordinate clauses in Section 5.2).

| Bangru (Miji) | |||||||||

| (42) | a. | madhu | ravi-ya | miavi | teacher | té-ro | |||

| Madhu | [Raviya-acc | good | teacher] | say-pst | |||||

| ‘Madhu said that Ravi is a good teacher.’ | |||||||||

| b. | mari | té-ro | iya-ga | maɲia | čo | mia | engineer-ro | ||

| Mary | say-pst | [3sg-gen | mother | det | good | engineer-pst] | |||

| ‘Mary said that her mother is a good engineer.’ | |||||||||

| c. | madhu | ravi-ya | bajar | liadi | ka | té-ro | |||

| Madhu | Raviya-acc | [market | go | to] | say-pst | ||||

| ‘Madhu told Raviya to go to the market.’ (Devi and Ramya 2017, p. 48) | |||||||||

5. Discussion of Methodological Issues in the Reconstruction of Protolanguage Syntax

This section aims to highlight four main issues arising from the present study which can contribute to a more general understanding and discussion of reconstructing and explaining syntactic changes. Visualisation of quantified data will also be presented to support arguments made on the basis of the data discussed hitherto.

5.1. Internal Explanation for the Head-Initial Noun Phrase Structures: Adjectives, Gender Specifiers and Quantifiers

The investigation of word order in noun modification has shown deviation among different constructions in Chinese and Tibeto-Burman languages. On the one hand, modifying nouns and possessors are consistently placed before head nouns, maintaining a canonical head-final pattern in Sino-Tibetan at deeper syntactic levels. On the other hand, some other modifiers such as quantifiers and adjectives are consistently prenominal in Chinese but more frequently postnominal in other Tibeto-Burman languages contrary to the Greenbergian word order correlations expected from verb-final languages. The reason for the latter may be due to a similar mechanism which is responsible for head-initial structures emerging in southern Chinese languages as discussed in Section 4.1. Therefore, we are particularly interested in the features which show deviation from expected typology, i.e., adjectives, gender specifiers and quantifiers. In this section, we will use evidence from Chinese languages as an explanatory tool for what could have happened in Tibeto-Burman at much earlier stages.