Abstract

In a European context, where member states of the European Union share a common language policy, multilingualism and foreign language (FL) learning are strongly promoted. The goal is that citizens learn two FLs in addition to their first language(s) (L1). However, it is unclear to what extent the multilingual policy is relevant in people’s lives, at a time when the English language is established as a lingua franca. This survey-based study contributes insights into the relevance of the EU multilingual policy in an intra-European migration context, by focusing on Swedish migrants (n = 199) in France, who are L1 speakers of Swedish. We investigated the perceived importance of skills in FL French, FL English, and L1 Swedish, for professional and personal life. The quantitative analyses showed that participants perceive skills in French and in English to be equally important for professional life, whereas skills in Swedish were perceived to be less important. For personal life, skills in French were perceived as the most important, followed by skills in English, and then Swedish. In conclusion, the European multilingual language policy appears to be reflected in Europeans’ lives, at least in the case of Swedish migrants in France.

1. Background

The value of language skills is continuously debated in a European context where member states of the European Union (EU) share a common language policy. The language policy promotes linguistic diversity and multilingualism among EU citizens (European Commission n.d.a). With respect to foreign language (FL) learning, the EU objective is that citizens learn two FLs in addition to their first language (L1). Multilingualism is not only assumed to increase mobility and intercultural contact as well as educational and professional opportunities, but is also identified as a key competence for lifelong learning. Key competencies include “knowledge, skills, and attitudes needed by all for personal fulfillment and development, employability, social inclusion, and active citizenship” (European Commission n.d.b). There are in other words—to say the least—strong assumptions regarding the value and necessity of multilingualism for the individual European citizen. However, some argue that there is a discrepancy between EU language policy and “the reality on the ground” (Seidlhofer 2020, p. 390). While multilingualism and FL learning are promoted and implemented in a top-down fashion, the English language has established itself as a lingua franca in the European context, in a bottom-up fashion (e.g., De Swaan 2002, 2004; Ferguson 2018; Seidlhofer 2020; Wright 2009). According to several scholars, English has become the main medium of communication in the European Union on various levels in people’s lives and in society (De Swaan 2002; Seidlhofer 2020; Wright 2009). English has entered Europeans’ everyday lives through a number of channels, including social media, online gaming, popular culture, and science (e.g., Seidlhofer 2020). Additionally, English is by far the most studied FL in EU member states. In a clear majority of EU member states, over 90% of lower secondary school pupils study English (Eurydice 2017), and there is a growing trend in non-English speaking countries to teach bachelor’s and master’s programs exclusively in English (e.g., Murata 2019). Furthermore, English is the lingua franca in many people’s professional lives as a result of the globalization process of national economies (see, e.g., Gerritsen and Nickerson 2009; Sherman and Nekvapil 2018). Finally, the increased movement of citizens within Europe is argued to help explain the widespread use of English as a lingua franca. With increased mobility comes an increased number of contact situations between speakers with different L1s, which accentuate the need for a common means of communication (e.g., Seidlhofer 2020).

In view of this apparent contradiction between multilingual policy and reality, the obvious questions are: How relevant is the EU multilingual policy in Europeans’ lives? Are FL skills in English enough to live a life in a European context today? These questions have not yet been thoroughly addressed. It seems crucial to make sure that educational policy aligns with reality—so that education prepares its young citizens in relevant ways (cf. Coulmas 1992)—yet, several scholars however point out the unwillingness to debate this discrepancy (e.g., De Swaan 2004; Seidlhofer 2020; Wright 2009). For example, in 2009, Wright (2009) discussed “the unresolved clash between top-down policy and bottom-up practice, and the unacknowledged language problems this causes in both the European institutions and the wider world” (p. 97). In 2020, Seidlhofer (2020) argued that “The discrepancy between the ideal and the real has been largely ignored by both policymakers and the academic mainstream, and only fairly recently have there been signs of any serious debate on this important issue” (p. 394). To date, little is known about the importance of skills in multiple languages in European citizens’ lives. This study begins to fill this gap and aims to contribute knowledge about the relevance of EU multilingual language policy (L1 + 2 FLs). It does so by providing data “from the ground”, i.e., by investigating how important language skills are perceived to be from the perspective of European citizens themselves. The study takes the case of Swedish migrants1 in France and investigates to what extent they perceive skills to be important in FL French (the language of the host country), FL English, and L1 Swedish, in their professional and personal life in France.

The reason for choosing a migration context is that language is an inevitable aspect of the migration experience. If the multilingual policy (i.e., skills in two FLs in addition to the L1, whereof one FL is typically English) is relevant, we believe that the perceived importance of skills in different languages should be revealed in a migratory setting where English is not the official language, and where adults need to set up a new life with all the responsibilities that come with such a project. Considering the framework of analysis, the Swedish population is interesting to study, given that Swedes are known to be among the most proficient FL users of English in Europe (European Commission 2012). In 2014–2015, there were approximately 30,000 Swedish migrants in France (Svenskar i Världen 2015). Typically, Swedes migrate to France out of their free will, because of an attraction to, or interest in, the host culture and or language (see Forsberg Lundell and Bartning 2015), and may therefore be characterized as “lifestyle migrants” (Benson and O’Reilly 2009) or “cultural migrants” (Forsberg Lundell and Bartning 2015). While some stay long-term in France, others stay for a limited period of time. France is a linguistically interesting context to analyze because it presents a contradiction between mono- and multilingual ideals (see Section 3). Nevertheless, attitudes towards the English language are generally positive among the French people (European Commission 2012), and the nation has become increasingly globalized over the last decades (KOF Swiss Economic Institute n.d.). This has assumingly strengthened the status of English as a lingua franca also on French territory, as in the rest of Europe (see, e.g., Seidlhofer 2020). Before presenting the study, we will provide a literature review, followed by a presentation of the French context.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Underpinnings

Asking language users to indicate to what extent they perceive skills in languages x, y, and z to be important is asking them to make an evaluation, to attribute a value. When talking about “value” in a linguistic context, the language economist Grin (2019) reminds us that it is important to consider “at what level or from whose perspective value is being examined” (p. 711). He explains that the value of languages and language skills may be studied or attributed at the level of society or the individual. In the former case, we talk about the “social value”, and in the latter case, about “private” value. This research takes the perspective of the individual and investigates the perceived value of skills in a given language, in professional and personal life, and is thus concerned with the private value of language skills. In this context, it is important to clarify that we do not imply that a given language would be inherently more valuable than another, but what is at stake here, is the value that the “possession of a language” (Coulmas 1992, p. 57), i.e., skills in a language, is perceived to have. Naturally, the value of skills in a given language will vary between individuals (Grin 2019) just like linguistic needs vary between individuals (Krumm 2012). Furthermore, languages can be considered valuable for a number of reasons (Coulmas 1992). To better understand what criteria tend to be involved when people attribute value to skills in a given language, we will turn to sociolinguistic and multilingual literature. Sociolinguistic theorizing of the “value” of language is directly influenced by economic theory and terminology, and often draws on the sociologist Bourdieu’s conception of the “linguistic marketplace” where languages are valued to different extents and possess different “symbolic capital” (Bourdieu 1991).

Scholars describe people as rather rational when attributing value to skills in a given language. One of the primary criteria is assumed to be a language’s functional potential in a given setting (Coulmas 1992; De Swaan 2002). The functional potential is linked to the perceived utility of the language, primarily determined based on the number of speakers that skills in a given language enable an individual to interact with, but also on the number of domains that the language is used for, such as administration, science, commerce, religion, etc. (Coulmas 1992). Naturally, the functional potential of a given language is heavily context-related (Coulmas 1992). Interestingly, it is assumed that there is a limit to the functional potential of a language, at least from a labor market point of view, where the offer and demand principle governs (cf. Coulmas 1992). By this logic, skills in language x may become banal with time, and changes in the economy may lead to the need for skills in a language that is only known by a minority (Coulmas 1992; Grin 2019). For example, some predict that the competitive advantage that English language skills have historically presented will recede, as skills in English are becoming more and more taken for granted (see, e.g., Graddol 2006, p. 15). The value of skills in a given language may also be determined based on cultural or aesthetic criteria (Coulmas 1992; Lehmann 2006). For example, skills in a given language may be valued because of its link to a literary and cultural tradition, to a religion, or because of the aesthetical experience it offers, if the language is judged particularly beautiful by an individual. Furthermore, the literature suggests that attributing value to skills in a given language may be tied to individuals’ ideologies. For example, some individuals who have migrated view skills in the host language (HL) as a vital part of the integration process, as a key to understanding the host culture, and as an essential aspect of citizenship (see Forsberg Lundell et al. 2022). Finally, the value of skills in a given language may also be attributed based on emotional or identity-based criteria. This is supported by multilingual research, which has shown that different languages are experienced to allow for different levels of self-expression and that for some multilinguals, switching to another language provokes a sense of “feeling different” (e.g., Dewaele 2016). In general, the L1 tends to evoke stronger emotional reactions and be perceived as more emotional than FLs (Dewaele 2010; Dewaele and Pavlenko 2001–2003; Harris 2004; Harris et al. 2003). However, an FL may become more emotionally significant through life events or through social relationships experienced in the FL, if these involve strong emotions (e.g., De Leersnyder et al. 2011). In the case of migration, Krumm (2012) argues that the L1 is typically perceived as particularly valuable to migrants, on the basis that the L1 would constitute an essential component of their identity, and a link to their origin and the lives they left behind when migrating. However, others point out that some individuals abandon their L1 because “they have higher expectations of a different language” (De Swaan 2004, p. 568). Finally, research suggests that some individuals value skills in multiple languages since “being multilingual” is a valued aspect of their identity, just like others value skills in the English language because of their “international posture”, i.e., their interest in an international lifestyle in which English language skills are an integral part (e.g., Henry 2017; Yashima 2002). Languages and language skills may thus be attributed value for a variety of reasons.

Valuing skills in language x does not, however, necessarily imply valuing skills in another, or in several other languages less. In fact, there is substantial evidence from the literature that different languages fill different functions in a multilingual individual’s life (see, e.g., Hlavac 2013). Such observations are at the heart of Grosjean’s (1997, 2016) “complementarity principle”, according to which individuals typically learn and use their languages for “different purposes, in different domains of life, with different people” (Grosjean 1997, p. 165). The principle holds that “different aspects of life often require different languages” (Grosjean 1997, p. 165). The principle, however, does not assume an internal value hierarchy.

2.2. Previous Research

To date, there is relatively little research in a European context that investigates citizens’ perceived importance of skills in different languages in adult Europeans’ lives.

There is, however, a quite extensive body of research on European school students’ attitudes towards FL learning. One of the purposes of this research has been to understand the impact of the global spread of English as a lingua franca on younger Europeans’ attitudes towards the learning of languages other than English (LOTEs) (e.g., Busse 2017; Dörnyei et al. 2006). In general, it is found that the perceived global status of English appears to affect attitudes to LOTE learning negatively. For example, in a Hungarian context, Dörnyei et al. (2006) used a survey to investigate 13,391 adolescents’ FL learning motivation at three points in time (1993, 1999, 2004). The questionnaire evaluated the participants’ motivation to learn English, French, German, Russian, and Italian, which were commonly taught languages at the time of the study. The findings revealed that while English maintained its top rank in among the five languages over the years of the study, there was a general decline in motivations to learn LOTEs, Hungary’s traditional lingua franca German included. The authors conclude that the Englishization process impedes the learning of LOTEs (p. 143). Busse (2017) explored attitudes toward English and other European languages among 2255 secondary school students in Bulgaria, Germany, the Netherlands, and Spain (aged 14–18 years). The author observed that school students across the four research contexts all believed that the English language would be particularly important to their future lives, especially for the professional domain. Skills in other European FLs were perceived as less important and useful. In sum, as far as the quoted studies are concerned, English is perceived as a valuable world language by the younger generation in several European countries, and this perception tends to affect attitudes toward LOTEs negatively. The above-mentioned studies were conducted in an FL learning context. Interestingly, another tendency was found in a Catalan–Spanish migration context, where Ianos et al. (2017) investigated language attitudes among 72 secondary students of immigrant origin (both European and non-European). Overall, they found that participants generally held favorable attitudes towards all three languages and that these were relatively stable over the two years of the study, with the exception of attitudes towards Catalan, which became more favorable. The positive attitudes towards English were assumed to be due to its status as a lingua franca, and the positive attitudes towards Spanish and Catalan were assumed to be due to their official status in the bilingual education context of the study.

With respect to Europeans’ perceptions concerning the importance of language skills in their adult lives, research is, however, scarce. To the best of our knowledge, there is no study that quantitatively investigates Europeans’ perceptions of the importance of skills in different languages in a migratory context. There are some qualitative studies with other research purposes, but which nonetheless touch upon the issue of language proficiency, and include intra-European migrants who have migrated to host countries where English is not an official language (Forsberg Lundell and Arvidsson 2021; Forsberg Lundell et al. 2022; Olsson 2018). In general, these studies suggest that migrants’ perceptions of the importance of language skills may vary not only depending on the particular linguistic market of the host country, but also across different domains of life. For some, skills in a given language were perceived to be crucial in the professional domain of life, whereas skills in another language were important in the personal domain, for example, to maintain relationships. Particularly informative are the perceptions revealed in the interview-based study by Forsberg Lundell and Arvidsson (2021), since it also included Swedish migrants in France. The aim of the study was to understand what factors promote adult second language learning. During the interviews, participants were asked how important skills in French had been to them when establishing a life in the host country, France. A quite contradictory picture appeared. Whereas some participants affirmed that French language skills had been crucial for them to integrate into French society and to obtain well-being on a personal and professional level, others reported that French language skills were of a minor, if of any, importance, both for professional and personal life, where skills in L1 Swedish and FL English were sufficient. The study thus revealed contradictory perceptions regarding the perceived value of language skills among Swedish migrants in France. However, to better understand the relevance of the EU multilingual policy, a quantitative approach is needed. This study quantitatively explores the relative importance of skills in different languages as perceived by Swedish migrants in France. By investigating a large number of individuals’ subjective evaluations, we seek to discern a more general indication of the importance (or lack thereof) of becoming multilingual as a migrant in today’s Europe. It should be pointed out that the study does not investigate migrants’ proficiency levels in these languages, nor their patterns of use of these languages, but seeks to understand how important they perceive skills in different languages to be, to them, in their lives as European citizens in a European migration context—Swedes in France. This study investigates migrants’ perceptions of how important skills are in FL French (the host language), FL English, and L1 Swedish. Before presenting the study, we present the French context.

3. The Research Context: France

Metropolitan France2, with just over 67 million inhabitants, is the second most populated country in Europe (Eurostat 2020). Of this population, 10.2% are immigrants, i.e., 6.8 million (L’Institut National de la Statistique et des Études Économiques 2021). The country’s membership in the EU has facilitated the influx of migration from other European member states. Among the other EU member states, France had the fourth highest inflow of migrants coming from other EU countries in 2019 (Mooyaart and de Valk 2021). The immigration flows have added to the linguistic diversity in France. According to a national survey conducted in 1998, there were around 400 languages were represented on French soil (Héran et al. 2002). Yet, French is the official language of the country (Ministère de la Culture n.d.). Historically, efforts have been made to preserve and promote French through language policy, including legislation and national educational objectives. For example, as a response to the increasingly dominating role of English as a global language, the Toubon law was passed in 1994 (République Française 2021). This law mandates that French is used in the workplace, commerce, public meetings, education, and audio–visual media. Additionally, in 2016, a law was passed mandating that immigrants (from non-EU countries) who wish to stay long-term in France sign a republican integration contract (Ministère de l’Intérieure 2019). Through this contract, they commit to an integration process for a duration of five years, including learning French, which is stated to be key to integration into French society (Ministère de l’Intérieure 2019; République Française n.d.). While progress in the French language is not formally tested, HL proficiency is a formal requirement to become a French citizen. In order to be eligible to apply, candidates need to prove they have attained the B1 level in spoken and written French, according to the CEFR scale (Council of Europe n.d.; Ministère de l’Intérieure 2020). Not all immigrants, however, choose to apply for citizenship.

While the above-mentioned policies aim to promote and conserve the French language, other policies aim to promote FL learning. In line with the European language policy, the French school system imposes on its pupils the study of two FLs in addition to their mother tongue (Minstère de L’éducation Nationale, de la Jeunesse et des Sports n.d.). A first FL is introduced in primary school, and a second FL in secondary school, where English is obligatory (Minstère de L’éducation Nationale, de la Jeunesse et des Sports n.d.). The English language thus has a particular status as an FL, which is also reflected in the Eurobarometer (European Commission 2012), a survey on Europeans’ language skills and attitudes towards language learning. The survey reveals that most French respondents perceive English (79%) and Spanish (33%) to be the most useful for their personal development other than their mother tongue (European Commission 2012). Additionally, when asked, in the same survey, to name the two languages they believed to be the most useful for their children to learn, 92% of the French respondents named English, 28% named Spanish, and 28% Chinese (European Commission 2012). Considering English proficiency, 39% of the population of France report speaking English well enough to have a conversation (European Commission 2012). Regarding English language use, 57% reported using English “occasionally” (rather than “every day/almost every day” or “often but not on a daily basis”) (European Commission 2012). Such positive attitudes were confirmed in a recent survey study, where Walsh (2015) found that the 401 French respondents generally perceived English proficiency as “important and necessary” (p. 40). To the best of our knowledge, no recent study investigated English in the workplace, although between 1994–1999, data collected through the European Community Household Panel (ECHP) indicated that 11.7% of the French use English at work (Williams 2011). As France has become more and more globalized over the last 20–30 years (KOF Swiss Economic Institute n.d.), the frequency of use of English at work may have increased.

The Study

The study seeks to respond to the following research questions:

- (1)

- To what extent are skills in French, English, and Swedish perceived to be important for professional life among Swedish migrants in France?

- (2)

- To what extent are skills in French, English, and Swedish perceived to be important for personal life among Swedish migrants in France?

4. Methodology

The study includes Swedish migrants in France and draws on data generated through an online survey (see Section 4.3).

4.1. Sampling and Procedure

Participants were recruited using convenience and snowball methods. An invitation to fill out a web survey was posted, in Swedish, on various Social Network groups for Swedish expats in France, and were sent to a number of Swedish associations, organization, institutions, and institutes. The title and the content revealed that the research concerned Swedes in France and anyone who self-identified as Swedish was welcome to take the survey. In the invitation, the stated criteria for participation were that participants should (a) be at least 18 years old, (b) have moved to the host country at 18 years of age or later, and (c) be residing in the host country. The invitation contained the link to the online survey as well as the encouragement to spread the call for participants within their own networks. The survey was administered in Swedish and was available online between mid-September and late October 2021 and took between five and 10 min to fill out. In total, 215 responded to the survey, but we excluded those who had French as their L1 (n = 5), those who had English as their L1 (n = 3), those who reported having first migrated to France before the age of 18 (n = 11), and one person who reported not living in France any longer (n = 1).

4.2. Participants

The final sample of 199 participants had a mean age of 53.3 (SD = 15.6). Among them, 47 were men and 150 were female (2 participants did not state their gender). The average age of (first) arrival in France was 37.7 (SD = 17.1; range: 18–76) and the mean length of residence was 11.9 (SD = 11.9; range: 0.04–56.9 years). Swedish was the (or one of the) L1(s) of all participants and they were all FL users of French and English. Additional L1s represented in the sample were Spanish (n = 1), Italian (n = 1), Other language(s) (n = 13). Additional FLs represented in the sample were Spanish (n = 61), Italian (n = 34), Portuguese (n = 9), and “Other language(s)” (n = 33). As Table 1 shows, the participants were spread out in France. Table 1 contains information about the participants’ place of residence and Table 2 contains an overview of the participants’ professional or other activities. The participants had the possibility of selecting more than one option for the information in both Table 1 and Table 2, if more than one option applied to them. This explains why the total exceeds the number of participants.

Table 1.

Distribution of participants’ place of residence.

Table 2.

Participants’ professional or other activities.

4.3. Instrument

The online survey was created using the survey tool Survey & Report. First, the participants filled out a socio-biographic section (e.g., language repertoire, age, gender, age at first immigration, length of residence, and employment (or other) status). Participants were then asked to indicate how important they perceived French, English, and Swedish language proficiency to be a) in their personal life, and b) in their professional life, on a scale from 1–7 (1 = not important at all, 7 = very important). The wording of the questions was the following: How important do you perceive knowing language x to be in your personal life? How important do you perceive knowing language x to be in your professional life? These two questions were repeated for each of the focal languages of French, English, and Swedish. These ratings constitute the data of this study. With the purpose of obtaining as many survey responses as possible, we did not ask any mandatory open follow-up questions about the perceived importance ratings, although we did inform the respondents that they had the possibility of commenting on each of their ratings by typing their comments in a text box placed underneath each rating scale. Respondents could thus skip a question if they were uncertain of the content or unwilling to provide a response. With respect to “professional life”, the participants were asked to choose the response option “I do not work” in case this applied to them, meaning that only professionally active participants shared their perceptions regarding the professional domain. The survey also generated additional data to be used to investigate other research questions, which are outside the scope of the present study.

4.4. Data Analysis

The respondents’ ratings of the perceived importance of French, English, and Swedish skills in their professional and personal life were analyzed quantitatively. In order to investigate the relative importance of perceived skills in each language, we used box plots, violin plots, and computed mean differences between the ratings of each language together with the corresponding confidence intervals. The analyses were conducted using the statistical software R version 4.1.0 (R Core Team 2021). We follow recent recommendations from the American Statistical Association to stop significance testing (for arguments against significance testing, see Wasserstein et al. 2019; Wasserstein and Lazar 2016). In line with these recommendations, we opted to not include any p-values but instead to focus on making our results meaningful and making the uncertainty in the data understandable.

The analysis concerning professional life is based on ratings obtained from 119 respondents for French, 120 respondents for English, and 119 for Swedish There was thus one participant who only rated the perceived importance of English in professional life, but the participant’s rating was still used in Figures and analyses. The quantitative analysis concerning personal life is based on responses obtained from 199 participants, i.e., the totality of the sample. See Table 3 for the number of participants who rated each language in the two settings. As specified under Section 4.3, only professionally active participants provided ratings for professional life, which is why the number of observations differs between the professional and the personal domain.

Table 3.

The number of participants (n), mean, standard deviation (SD), median, and interquartile range (IQR) for the perceived importance of skills in French, English, and Swedish. The statistics are presented first for professional life and then for personal life. The minimum value of the scale was 1 and the maximum was 7.

5. Results

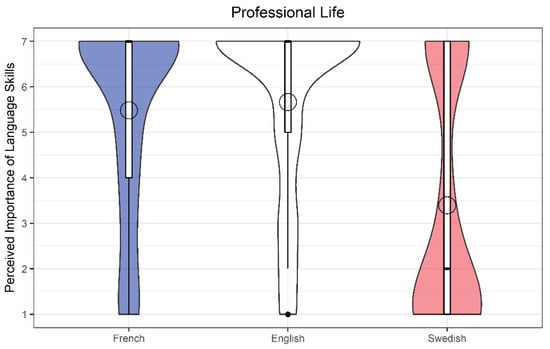

5.1. Perceived Importance of Skills in French, English, and Swedish for Professional Life

The quantitative analysis indicates that FL skills in French and in English are perceived to be about equally important for professional life, whereas skills in L1 Swedish are perceived to be less important (see Table 3 for descriptive statistics). As can be seen in Figure 1, there were no striking differences when comparing French and English. This was also apparent when comparing the mean difference between the ratings. Namely, the mean difference between the perceived importance of skills in English was only 0.22 (95% CI [−0.34, 0.77]) scale steps higher than for skills in French. The confidence interval also indicates that it is unlikely that the population difference is much larger than in the sample. Furthermore, as Figure 1 also shows, the perceived importance of skills in Swedish was rated as less important than the perceived importance of skills in both French (Mean difference = 2.05, 95% CI [1.33, 2.78]) and English (Mean difference = 2.29, 95% CI [1.71, 2.87]). Moreover, by inspecting the plots in Figure 1, we can also conclude that the large majority of the migrants rated skills in French and in English as highly important to their professional life, with only a few participants using any of the lower scale steps. Meanwhile, for the perceived importance of skills in Swedish, the distribution of the rating is rather bimodal considering that the majority perceived Swedish language skills as unimportant to their professional life, but nonetheless, a smaller, but still substantial, part of the immigrants rated Swedish language skills as highly important. In sum, in a professional setting, it is about as common for the Swedish migrants in France to perceive that FL skills in French and in English are highly important, but it is less common for skills in their L1 (Swedish) to be perceived as important.

Figure 1.

Violin plots overlaid with box plots and means (circles) illustrating the distribution of the perceived importance of skills in each language in professional life. The width of the violin plots represents the proportion of the ratings at each level.

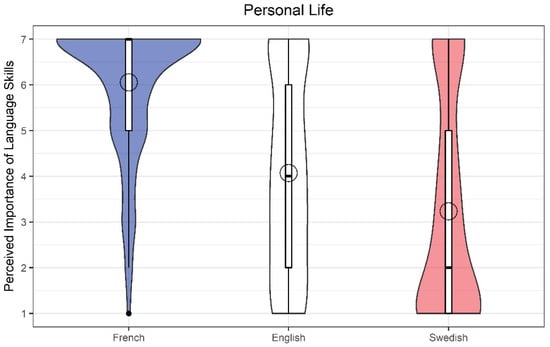

5.2. Perceived Importance of Skills in French, English, and Swedish for Personal Life

When the participants rated the perceived importance of language skills in a personal setting, French language skills were clearly the most important, followed by English language skills, and then skills in Swedish. This is evident both by inspecting Figure 2 and the mean differences. The mean difference in ratings between the perceived importance of skills in French and English was 1.98 (95% CI [1.57, 2.40]), and the mean difference between the perceived importance of skills in French and Swedish was 2.82 (95% CI [2.43, 3.21]). In other words, the observed differences are fairly substantial. However, the mean difference between ratings concerning skills in English and Swedish is smaller (M = 0.83, 95% CI [0.43, 1.24]). While the differences give some idea of the relative perceived importance of skills in each of the languages, the plots in Figure 2 give a more detailed picture. By inspecting Figure 2, we conclude, again, that the large majority of the Swedish migrants rated French language skills as highly important to their personal life. Meanwhile, the ratings were fairly evenly distributed across the scale for skills in English. Finally, similar to Swedish language skills in professional life, the distribution of responses was somewhat bimodal for Swedish language skills in personal life. The figure indicates that in general the participants either rated skills in Swedish as unimportant or highly important, while fewer used the middle of the scale. However, the majority still judged Swedish language skills as unimportant. In sum, skills in the HL French were perceived as most important for personal life, followed by skills in English and then in L1 Swedish. However, there was a large variation in how important English and Swedish language skills were perceived by the Swedish migrants.

Figure 2.

Violin plots overlaid with box plots and means (circles) illustrating the distribution of the perceived importance of each language in personal life. The width of the violin plots represents the proportion of the ratings at each level.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

This study investigates the relevance of the European multilingual policy by exploring Swedish migrants’ perceptions of the importance of language skills in three languages in their personal and professional life in the host country France. This was investigated using an online survey, in which participants were asked to indicate how important they perceived skills to be in French (FL), English (FL), and Swedish (L1), along a 7-point scale ranging from “not important at all” to “very important”. They made these ratings both for their professional and personal life separately. In this section, we will discuss the results pertaining to each research question before discussing the study’s limitations and drawing some tentative conclusions.

The first research question concerned the participants’ professional life. We found that FL skills in English and French were perceived to be of similar importance for their professional life, while L1 Swedish skills were perceived to be less important. The perceived importance of skills in the HL French indicates that French language skills are highly valued in the linguistic market in France and that French holds a functional potential in this context (cf. Coulmas 1992). These findings are not surprising if one considers the descriptive data of the participants’ professional activities, which indeed shows that a large proportion of the professionally active sample works for a French business or institution, or works in French under other forms. The perception of skills in the HL French as crucial for professional integration was expressed by certain Swedes who migrated to France as adults in previous research (Forsberg Lundell and Arvidsson 2021). This perception appears to be generalizable to a larger population of Swedish migrants in France.

The high value attributed to French language skills does however not seem to reduce the value attributed to skills in English. More than half of the sample used the highest value on the rating scale when sharing their perceptions regarding the importance of skills in both French and English. This suggests that FL skills both in French and English fill a vital function in the professional domain of a large proportion of Swedish migrants’ lives in France. In light of the attempts from the French government to reduce the influence of English (République Française 2021), it is interesting to find that English language skills are generally perceived as very important in the professional lives of Swedish migrants in France. This may certainly be the result of the increased globalization that France has gone through over the last two to three decades (KOF Swiss Economic Institute n.d.). A relatively large number of the participants reported working in an international environment. There are several sources indicating that English is used as a lingua franca in such environments (see, e.g., Gerritsen and Nickerson 2009; Sherman and Nekvapil 2018) and this study suggests that this is also the case in France. Such an interpretation is in line with accounts of the frequent English use at work among Swedish migrants in France (Forsberg Lundell and Arvidsson 2021). It is possible that the Swedes’ strong skills in English as an FL compared to other Europeans constitute an advantage as they enter the labor market in France where skills in the English language may still constitute a competitive advantage (cf. Graddol 2006).

Skills in the Swedish language were generally perceived to be considerably less important in Swedish migrants’ professional life in France in comparison with skills in French and English. This is not surprising per se, although what is somewhat surprising is that the distribution of the ratings was slightly bimodal, suggesting that for some individuals, Swedish language skills were indeed perceived to be very important. Likely, these were the participants who reported working for a Swedish business or institution, or in an international environment under other conditions. It is of course also possible that some of the French businesses and/or institutions where the participants reported working have ties with Sweden. In such a case, the Swedish migrants’ L1 skills in Sweden certainly constitute a competitive advantage in the French labor market, where Swedish is a minority language. This would illustrate language economists’ and sociolinguists’ assumptions that a language known only by a few can become an asset in the linguistic market, and can therefore take on a strong value to the individual who possesses skills in that language (cf., e.g., Coulmas 1992; Grin 2019).

In the respondents’ personal life, response patterns are different. Here, they perceive skills in French to be the most important, followed by skills in English and then Swedish. In other words, in these migrants’ personal lives, French language skills prevail over English and Swedish. The data do not tell us in what ways skills in French are important in these respondents’ personal lives, but it is likely that the French language has a functional value also here, in that communicative functions linked to administration, commerce and public media are carried out in the official language French in France (République Française 2021). The functional value may also include access to social circles. Such an interpretation is in line with findings from qualitative research including Swedish migrants in France, where certain participants expressed a perceived necessity to know French in order to integrate into French-speaking social circles (Forsberg Lundell and Arvidsson 2021). Furthermore, the value attributions to skills in French in participants’ personal lives may be based on aesthetic and cultural values (cf. Coulmas 1992). This interpretation aligns with observations made by Forsberg Lundell and Bartning (2015), who find that a common feature among Swedes who chose to migrate to France is their attachment to the French language as such, and to the French culture.

There was a relatively large spread of perceptions regarding the importance of skills in English and Swedish for personal life in the sample. Such variation may reflect differences in how migrants socialize, be it mainly with HL speakers, as some Swedes in France have previously reported (Forsberg Lundell and Arvidsson 2021), or, with other expats and co-nationals, as seen among other Swedes, both in France and in Spain (cf. Forsberg Lundell and Arvidsson 2021; Olsson 2018). This variation could certainly also reflect variation in patterns of contact with family at home, or in personal interests and preferences with respect to the language used for media and culture consumption. Finally, that a relatively large proportion of participants perceived Swedish to be of little importance in their personal lives indicates that their L1 proficiency is not as functional in the given context (cf. Coulmas 1992), and that, for the majority, life in France is managed through other languages.

It is interesting to note that skills in L1 Swedish are rated as the least important in the migrants’ personal lives, even less so than in their professional lives, in light of the assumption often put forth in the literature, namely that migrants perceive their L1 as particularly valuable for emotional or identity-related reasons (cf. Krumm 2012). Although this finding in no way needs to imply that these participants have abandoned their L1, the observation nuances such an assumption, and aligns with De Swaan’s (2004) statement that some migrants, as they come to a new country, may simply have “higher expectations of a different language” (p. 568).

That skills in French and English were perceived to be more important in the Swedish migrants’ personal lives may to a certain extent reflect what languages they use in their social life, where tying bonds in French and/or English may have led them to develop strong emotional bonds to these languages. Such an interpretation is in line with empirical research among multilinguals and the effects of affective socialization in the FL (e.g., De Leersnyder et al. 2011).

Taken together, the Swedish migrants in France appear to attribute value to skills in all three included languages (L1 Swedish, FL English, FL French) although to varying extents. This indicates that the included languages fill different functions in the lives of the Swedish migrants and align well with the complementarity principle (Grosjean 1997, 2016). It is clear from the data set in the study that value attributions are not mutually exclusive—perceiving skills in language x as important does not exclude perceiving skills in language y or z as important. This observation also aligns well with the complementarity principle (Grosjean 1997, 2016), which does not hold that languages are ranked in the individual’s mind, but rather distributed—often unequally—across various domains of life. Among the three languages, the largest variation in ratings was found for skills in Swedish and English. These variations may well indicate that linguistic needs differ between migrants and that such needs are context-dependent, as previously suggested by Krumm (2012).

Although the perceptions reported in this study come from adult Europeans in a migration context, it is intriguing to note the discrepancy between these and the perception that English is more useful than other FLs, which has appeared to be widespread among school students in different FL contexts in Europe (e.g., Busse 2017; Dörnyei et al. 2006). That the school students simply are not adult migrants in a foreign country clearly helps explain this discrepancy, yet, it nonetheless invites a reflection on how context and real-life needs may shape the individual’s perceptions regarding the value of language skills. It is possible that the participants in this study had other perceptions prior to their emigration to France. That language perceptions and attitudes may fluctuate has been evidenced in previous longitudinal language attitude research (e.g., Ianos et al. 2017).

Based on the present study, we suggest the following approaches to better understand the relevance of the current European multilingual language policy in Europeans’ lives. First, while the present study yields insights into the perceived value of skills in French, English, and Swedish, it does not provide any further information on what circumstances and factors that influence perceptions regarding the value of language skills. Future studies could investigate the explanatory value of biographic and demographic variables, and other individual factors such as frequency and domain of use of language x, y and z, proficiency level in language x, y and z, language learning motivation, and perceived pressure to learn a given FL.

Second, the present study only included one case of migrants, in one migration context. To further understand the role of language proficiency in a European setting, future research could replicate the current study, with Swedish migrants in another European host country. This would allow the exploration of the extent to which the findings are contextually bound. Additionally, the study could be replicated with another migration population in France, to explore to what extent population characteristics such as migration motive or level of English language proficiency influence perceptions. Finally, it would be interesting to repeat the study in other countries with less monolingually oriented language policy and stronger status for English, such as Sweden. Additionally, the study could be replicated in a population with generally weaker English proficiency, since this may affect the perceived need for language skills.

The study has its limitations. The most evident limitation relates to the convenience sampling method. There may be a bias that could have influenced the results. It is possible that those who value languages and language learning believe it is more important to contribute to research on this than migrants who either have little interest in languages and language learning or who simply do not need it in their lives abroad. Additionally, one limitation pertains to the wording used to elicit information regarding participants’ perceptions. We asked the participants to rate the importance of skills in each language separately. To find out to what extent skills in English (in addition to the L1) are sufficient in today’s Europe, it would be informative to include Likert-scale items targeting experiences through explicit statements such as “It is sufficient to know English to get a job in France.” Finally, some of the participants may have arrived in France right before the pandemic COVID-19 broke out, and this may have affected their ratings.

To conclude, the study was carried out in an EU context, where a discrepancy is identified between the multilingual policy that promotes FL learning and Europeans’ real-life needs for skills in multiple languages, in a time when English increasingly functions as a lingua franca (De Swaan 2002, 2004; Seidlhofer 2020; Wright 2009). The study contributes insights into the relevance of the EU multilingual policy by providing evidence from “the ground” (Seidlhofer 2020, p. 390). Specifically, the study contributes in two important ways. First, it provides further evidence for the status of English as a global language in a European context. We found that the Swedish migrants in France perceive English skills to be as important as French language skills in a professional context. These findings imply that English skills have a prominent role in an intra-European migration context, and lend support to Seidlhofer’s (2020) statement that English “forms an integral part of the professional lives of a growing number of Europeans” (p. 392). However, this is not to the exclusion of a need for skills in the HL, suggesting that the migrants’ reality in the host country is indeed multilingual. Seidlhofer’s (2020) statement that “English in Europe is firmly established as a language of wider communication, enabling people to link up about common interests, needs and concerns across languages and communities” (p. 392) may be valid in certain contexts, but in the present research context including the given population, it does not seem to be the case that English is favored over the HL French, in the everyday lives of Swedes in France.

Second, the study provides evidence that perceptions regarding the importance of language skills for professional life differ from those in personal life. Perceptions regarding the importance of language skills differed between the professional and the personal sphere of the Swedes’ lives in France. These findings suggest that different domains of European migrants’ lives require different sets of language skills. Lastly, the EU multilingual language policy appears to be relevant in Europeans’ professional and personal lives, at least in the case of Swedish migrants in France.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.A.; methodology, K.A.; formal analysis, A.J.; writing—original draft preparation, K.A. and A.J.; writing—review and editing, K.A. and A.J.; visualization, A.J.; project administration, K.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their relevant comments and valuable advice.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | A “migrant” is here understood as “any person who is moving or has moved across an international border or within a State away from his/her habitual place of residence, regardless of (1) the person’s legal status; (2) whether the movement is voluntary or involuntary; (3) what the causes for the movement are; or (4) what the length of the stay is” (UN Migration Agency n.d.). |

| 2 | “Metropolitan France is the part of France (FR) located in Europe, including the island of Corsica.” (Eurostat 2013). |

References

- Benson, Michaela, and Karen O’Reilly. 2009. Migration and the search for a better way of life: A critical exploration of lifestyle migration. The Sociological Review 57: 608–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1991. Language and Symbolic Power. Cambrdige: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Busse, Vera. 2017. Plurilingualism in Europe: Exploring attitudes toward English and other European languages among adolescents in Bulgaria, Germany, the Netherlands, and Spain. The Modern Language Journal 101: 566–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulmas, Florian. 1992. Language and Economy. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. n.d. Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR). Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/common-european-framework-reference-languages/level-descriptions (accessed on 8 December 2021).

- De Leersnyder, Jozefien, Batja Mesquita, and Heejung S. Kim. 2011. Where do my emotions belong? A study of immigrants’ emotional acculturation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 37: 451–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Swaan, Abram. 2002. Words of the World: The Global Language System. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- De Swaan, Abram. 2004. Endangered languages, sociolinguistics, and linguistic sentimentalism. European Review 12: 567–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewaele, Jean-Marc. 2010. Emotions in Multiple Languages. Basingstoke: Palgrave-MacMillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewaele, Jean-Marc. 2016. Why do so many bi- and multilinguals feel different when switching languages? International Journal of Multilingualism 13: 92–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewaele, Jean-Marc, and Aneta Pavlenko. 2001–2003. Web Questionnaire ‘Bilingualism and Emotions’. London: University of London. [Google Scholar]

- Dörnyei, Zoltán, Kata Csizér, and Nóra Németh. 2006. Motivation, Language Attitudes and Language Globalisation: A Hungarian Perspective. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. 2012. Europeans and Their Languages: The Special Eurobarometer. 386. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/f551bd64-8615-4781-9be1-c592217dad83 (accessed on 4 November 2021).

- European Commission. n.d.a. About Multilingualism Policy. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/education/policies/multilingualism/about-multilingualism-policy_en (accessed on 8 December 2021).

- European Commission. n.d.b. European Education Area. “Council Recommendation on Key Competences for Lifelong Learning”. Available online: https://education.ec.europa.eu/focus-topics/improving-quality/key-competences (accessed on 31 August 2022).

- Eurostat. 2013. Glossary: Metropolitan France. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Glossary:Metropolitan_France (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Eurostat. 2020. EU Population in 2020: Almost 448 Million. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu (accessed on 6 December 2021).

- Eurydice. 2017. Key Data on Teaching Languages at School in Europe 2017 Edition. Available online: https://www.eurydice.si/publikacije/Key-Data-on-Teaching-Languages-at-School-in-Europe-2017-EN.pdf?_t=1554834232 (accessed on 25 September 2022).

- Ferguson, Gibson. 2018. European language policy and English as a lingua franca: A critique of Van Parijs’s ‘linguistic justice’. In Using English as a Lingua Franca in Education in Europe. Edited by Zoi Tatsioka, Barbara Seidlhofer, Nicos C. Sifakis and Gibson Ferguson. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 28–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsberg Lundell, Fanny, and Klara Arvidsson. 2021. Understanding high performance in late second language (L2) acquisition—What is the secret? A contrasting case study in L2 French. Languages 6: 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsberg Lundell, Fanny, and Inge Bartning. 2015. Cultural Migrants and Optimal Language Acquisition. Bristol: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Forsberg Lundell, Fanny, Klara Arvidsson, and Marie-Eve Bouchard. 2022. Language ideologies and second language acquisition: The case of French long-term residents in Sweden. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerritsen, Marinel, and Catherine Nickerson. 2009. BELF: Business English as a lingua franca. In Handbook of Business Discourse. Edited by Francesca Bargiela-Chiappini. Edingburgh: Edinburgh University Press, pp. 180–92. [Google Scholar]

- Graddol, David. 2006. English Next: Why Global English May Mean the End of ‘English as a Foreign Language. London: British Council. [Google Scholar]

- Grin, François. 2019. Economics and language contact. In Language Contact An International Handbook Volume 1. Edited by Jeroen Darquennes, Joseph C. Salmons and Wim Vandenbussche. Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 707–18. [Google Scholar]

- Grosjean, François. 1997. The bilingual individual. Interpreting 2: 163–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosjean, François. 2016. The Complementarity Principle and its impact on processing, acquisition and dominance. In Language Dominance in Bilinguals: Issues of Operationalization and Measurement. Edited by Carmen Silva-Corvalán and Jeanine Treffers-Daller. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 66–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, Catherine L. 2004. Bilingual speakers in the lab: Psychophysiological measures of emotional reactivity. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 25: 223–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, Catherine L., Ayse Aycicegi, and Jean Berko Gleason. 2003. Taboo words and reprimands elicit greater autonomic reactivity in a first language than in a second language. Applied Psycholinguistics 24: 561–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, Alistair. 2017. L2 motivation and multilingual identities. The Modern Language Journal 101: 548–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Héran, François, Alexandra Filhon, and Christine Deprez. 2002. Transmission des langues en France au XXe siècle. Population & Sociétés 376: 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Hlavac, Jim. 2013. Multilinguals and their sociolinguistic profiles: Observations on language use amongst three vintages of migrants in Melbourne. International Journal of Multilingualism 10: 411–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ianos, Maria-Adelina, Ángel Huguet, Judit Janés, and Cecilio Lapresta. 2017. Can language attitudes be improved? A longitudinal study of immigrant students in Catalonia (Spain). International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 20: 331–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KOF Swiss Economic Institute. n.d. Available online: https://kof.ethz.ch/en/ (accessed on 8 December 2021).

- Krumm, Hans-Jürgen. 2012. Multilingualism, heterogeneity and the monolingual policies of the linguistic integration of migrants. In Migrations: Interdisciplinary Perspectives. Edited by Michi Messer, Renée Schroeder and Ruth Wodak. Vienna: Springer, pp. 43–54. [Google Scholar]

- L’Institut National de la Statistique et des Études Économiques. 2021. L’essentiel sur les immigrés et les étrangers. Available online: https://www.insee.fr/fr/statistiques/3633212 (accessed on 6 December 2021).

- Lehmann, Christian. 2006. On the value of a language. European Review 14: 151–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minstère de l’Intérieur. 2019. Les Chiffres Clés de l’Intégration. Available online: https://www.immigration.interieur.gouv.fr/Info-ressources/Actualites/Focus/Les-chiffres-cles-de-l-immigration-2019-en-28-fiches (accessed on 8 December 2021).

- Ministère de l’Intérieure. 2020. Justificatifs du niveau de connaissance de la langue française. Available online: https://www.immigration.interieur.gouv.fr/Accueil-et-accompagnement/La-nationalite-francaise/Justificatifs-du-niveau-de-connaissance-de-la-langue-francaise (accessed on 8 December 2021).

- Ministère de la Culture. n.d. Promouvoir les langues de France. Available online: https://www.culture.gouv.fr/Thematiques/Langue-francaise-et-langues-de-France/Nos-missions/Promouvoir-les-langues-de-France (accessed on 6 December 2021).

- Minstère de L’éducation Nationale, de la Jeunesse et des Sports. n.d. Les langues vivantes étrangères et régionales. Available online: https://www.education.gouv.fr/les-langues-vivantes-etrangeres-et-regionales-11249 (accessed on 6 December 2021).

- Mooyaart, Jarl, and Helga de Valk. 2021. Intra-EU Migration 2010–2020. The Hague: Netherlands Interdisciplinary Demographic Institute (NIDI-KNAW)/University of Groningen. [Google Scholar]

- Murata, Kumiko. 2019. English-Medium Instruction from an English as a Lingua Franca Perspective. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, Erik. 2018. Guiden till Spaniensverige. Stockholm: Stockholm University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. 2021. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 2 December 2020).

- République Française. 2021. Légifrance. Available online: https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/loda/id/LEGITEXT000005616341/ (accessed on 6 December 2021).

- République Française. n.d. Qu’est-ce que le contrat d’intégration républicaine (CIR)? Available online: https://www.service-public.fr/particuliers/vosdroits/F17048 (accessed on 8 December 2021).

- Seidlhofer, Barbara. 2020. English as a lingua franca in the European context. In The Routledge Handbook of World Englishes. Edited by Andy Kirkpatrick. London: Routledge, pp. 389–407. [Google Scholar]

- Sherman, Tamah, and J. Jiří Nekvapil. 2018. Sociolinguistic perspectives on English in business and commerce. In English in Business and Commerce. Interactions and Policies. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Svenskar i Världen. 2015. Kartläggning av utlandssvenskar 2015. Available online: https://www.sviv.se/opinion/kartlaggning/ (accessed on 6 December 2021).

- UN Migration Agency. n.d. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/global-issues/migration (accessed on 3 November 2021).

- Walsh, Olivia. 2015. Attitudes towards English in France. In Attitudes towards English in Europe. Edited by Linn Andrew, Neil Bermel and Gibson Ferguson. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 27–54. [Google Scholar]

- Wasserstein, Ronald L., and Nicole A. Lazar. 2016. The ASA Statement on p-Values: Context, Process, and Purpose. The American Statistician 70: 129–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasserstein, Ronald, Allen L. Schirm, and Nicole A. Lazar. 2019. Moving to a World beyond “p < 0.05”. The American Statistician 73 (Suppl. S1). : 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, Donald R. 2011. Multiple language usage and earnings in Western Europe. International Journal of Manpower 32: 372–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, Sue. 2009. The elephant in the room: Language issues in the European Union. European Journal of Language Policy 1: 93–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yashima, Tomoko. 2002. Willingness to Communicate in a Second Language: The Japanese EFL Context. The Modern Language Journal 86: 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).