Abstract

While speakers of German have adopted many loanwords from other languages throughout history, recent diversification of language use in Germany is mainly driven by the global mobility of English. Previous research has therefore focused on various domains in which English linguistic resources are used, particularly in traditional media and social media communication. Furthermore, many studies on social media communication have also examined English language internet memes more broadly. Despite this plethora of research, little attention has been paid to how English is used in internet memes and reels produced by professional journalists in Germany. Playing a significant role in communication amongst young people, internet memes and reels are used by many German youth media organisations. In particular for youth radio stations in Germany, which have become multimedia outlets, online communication via Instagram is vital for their audience interaction. This paper examines the use of English linguistic resources in a professionally produced Instagram corpus of internet meme and reel captions produced by journalists working for one of the largest youth radio stations in Germany. Data for the analysis of Instagram content were collected as part of the larger ethnographic research project CIDoRA (funded by the European Union). For this project, a mixed methods approach was applied. Methods of data collection and analysis include linguistic ethnography both at the youth radio station and on the station’s Instagram profile page, informal interviews and 20 semi-structured interviews with journalists, and a quantitative and qualitative analysis of 980 meme and reel captions produced for the station’s Instagram profile. Since the youth radio station’s Instagram profile functions as a means of the station’s online self-advertisement, the analysis of this article also draws on a previous study by the researcher. This study analysed possible facilitating factors for the use of catachrestic and non-catachrestic anglicisms in radio station imaging (radio self-advertisement) of six German adult contemporary radio stations. The article therefore includes an analysis of the possible facilitating factors lexical field, brevity of expression, diachronic development of the pragmatic value of lexical items and semantic reasons for the use of English in Instagram content. It thereby explores the differences in anglicism use between these two media formats (radio broadcasting and social media communication) and whether possible facilitating factors for the use of English in adult contemporary radio station imaging are also facilitating factors for the use of English in meme and reel captions produced by the youth radio station.

Keywords:

English; German; social media; linguistic diversity; Instagram; memes; reels; linguistic ethnography; corpus analysis 1. Introduction

English linguistic resources, also known as anglicisms, are frequently used in countries where English does not hold an official status. Although speakers of German have adopted many loanwords from other languages throughout history including from Latin, Greek and French, recent diversification of language use in Germany is mainly driven by the global mobility of English (see Mair, 2024). This diffusion of English is intrinsically linked to global cultural flows, which, according to Appadurai (1996), are objects in motion due to accelerated globalisation (i.e., people and ideologies, technologies and media messages) mobilised across several scapes: media-, techno-, ideo-, ethno- and financescapes. As part of this cultural mobility, English language resources also become mobilised in linguascapes (Pennycook, 2003). Previous research on English in German has therefore focused on various domains in which English words and phrases are used, particularly in traditional mass media and social media communication (amongst others, Coats, 2019; Fiedler, 2022; Plümer, 2000; Schaefer, 2024). Furthermore, many studies on social media communication were also undertaken in relation to English language internet memes more broadly (amongst others, Greene & Schmid, 2024; Lou, 2017; Spilioti, 2020; Zenner & Geeraerts, 2018). Despite this plethora of research and the recent socio-pragmatic turn in language contact studies (see Zenner et al., 2019), little attention has been paid to journalistic practices and the reasons behind the scenes of media content production that lead to the use of English in professional media products such as internet memes1 and Instagram reels2. Playing a significant role in communication amongst young people, internet memes and reels are used by many German youth media organisations. For German youth radio stations in particular, which have become multimedia outlets, online communication via Instagram is vital for their target audience interaction and for staying up to date with the latest trends in their youth community.

This paper examines the use of English linguistic resources in an Instagram corpus of internet meme and reel captions produced by journalists working in the online team of one of the largest youth radio stations in Germany. Data for the analysis of Instagram content were collected as part of the larger, ongoing ethnographic research project CIDoRA (Community, Identity and Diversity in German Youth Radio; funded by the European Union). For this project, a mixed methods approach was applied for a thorough investigation of youth radio journalists’ representations of ethnic and linguistic diversity in their content. Methods of data collection and analysis include linguistic ethnography both at the youth radio station and on the station’s Instagram profile page, informal interviews (i.e., untaped situational conversations) and 20 semi-structured interviews with journalists, and a quantitative and qualitative analysis of 980 meme and reel captions produced for the station’s Instagram profile.

Since the youth radio station’s Instagram profile functions as a means of the station’s online self-advertisement, the analysis of this article also draws on a previous study by the researcher (Schaefer, 2019). This study analysed possible facilitating factors for the use of catachrestic and non-catachrestic anglicisms in radio station imaging (radio self-advertisement) of six German adult contemporary radio stations.3,4 The present paper therefore includes an analysis of the possible facilitating factors lexical field, brevity of expression, semantic reasons, and diachronic development of the pragmatic value of lexical items for the use of English in Instagram content. It thereby explores the differences in anglicism use between these two media formats (radio broadcasting and social media communication) and whether possible facilitating factors for the use of English in adult contemporary radio station imaging are also facilitating factors for the use of English in meme and reel captions produced by the youth radio station.

Section 2 provides a brief overview of the characteristics of social media language used by the youth radio journalists on Instagram. The discussion is based on online ethnography on the station’s Instagram page and examples from the Instagram corpus. This section is then followed by the methodology (Section 3), which explains the mixed methods approach applied in this study and how anglicisms were detected and counted in the online corpus. Section 4 outlines each possible facilitating factor for the use of English and how these categories are applied in the context of meme and reel captions. The results section then presents the findings of the study for each possible facilitating factor. It gives examples from the online corpus and insights from ethnographic observation and interviews with journalists working for the youth radio station.

2. Characteristics of Language Used in Journalistically Produced Instagram Content

Instagram is a social media platform where users mainly create, share, and comment on content within their network. Content that can be shared amongst users are images, videos, and text. It is a social media platform which is very popular amongst German youth and is preferred to other more traditional platforms such as Facebook and X (formerly Twitter) (Feierabend et al., 2024). The linguistic ethnographic fieldwork conducted as part of this study has shown that, for the youth radio station under investigation, Instagram is an opportunity to connect with its community, share information with its audience, and present and maintain its station image multimodally. However, in comparison to station imaging materials of German adult contemporary radio stations, where a station promotes its music playlist, services, and the radio hosts and presenters, the participating youth radio station’s strategy on Instagram is even more personality driven. In their Instagram content, the youth radio journalists focus mainly on two male characters and one female character to promote the station’s events, bring the audience closer to celebrities and provide information mainly through entertainment. This is achieved in the form of memes, meme reels, and reels. Memes produced by the youth radio station mostly take the form of image macros (see Zappavigna, 2012), which contain either an image or a short video (meme reels) combined with a rather short (humorous or sarcastic) textual element also called caption. These captions are usually no longer than one to three short sentences and together with the semiotic information of the image or short video convey the overall message of the meme. The images and video clips used for memes and meme reels of the youth radio station are usually adopted from previous memes that went viral on social media platforms and often feature celebrities, including movie stars, singers, and politicians. At times, the station’s online journalists also appear as characters in memes, which is a particular example of how the station makes use of the social bonding potential attributed to memes (Newton et al., 2022). This also applies to reels produced by the station, which are short videos that either show challenges (members of the online newsroom compete in challenges against each other or celebrities), present short surveys in the form of vox-pops (online journalists conduct short interviews with random members of their target audience in public spaces), or promote festivals supported by the station.5

Like for radio station imaging, the language used in meme and reel captions is kept rather short and for the most part informal. In example (1),6 which is a caption taken from a meme reel starring a popular German news anchor in the studio accidently laughing during her news presentation, this informality is mainly achieved through the use of the informal possessive pronoun deiner, the colloquial term Präsi (clipping of Präsentation + diminutive suffix -i), and the English lexical item Friends.

- (1)

- Wenn während deiner Präsi deineFriends in der letzten Reihe sitzen.(When during your presentation yourfriends are sitting in the back row.)

Furthermore, similar to language used in on-air station imaging content, language used on the youth radio station’s Instagram profile page shows characteristics of advertising language, particularly in the captions of the station’s reels. These reel captions often contain salient English resources and consist of single catchwords or short, headline-like phrases that are supplemented or contextualised by a subheading. In example (2), three anglicisms are used in the caption of a reel thumbnail that shows a female journalist interviewing an audience member at a festival. In particular, the English lexical item Rizz appears as salient here due to the double consonant [z] in word-final position, which does not conform to German orthographic conventions. Furthermore, both memes and reels are often branded with the station’s name, either as part of the name of an event or activity organised by the station or in the form of the station’s logo. This becomes evident in the reel caption shown in example (3), which is part of a thumbnail that pictures the stage of an open-air concert with artists performing and a large crowd cheering and waving at the artists.

- (2)

- Flirten mit RizzFestival Edition(Flirting with rizzFestival edition)

- (3)

- Radio X FestivalCountdown(Radio X festivalCountdown)7

From online ethnography on the station’s Instagram profile, it also became evident that certain English catchwords or phrases are repeatedly used in meme captions (see example (4)). This can also mostly be attributed to the nature of memes, where the recycling of popular phrases constitutes a core element of the discursive creation and comprehension process of a meme (Shifman, 2014; Zenner & Geeraerts, 2018). One of the most frequent English-based memes that occurred in the corpus followed the pattern [NOUN or NOUN PHRASE] be like: [X], where the closing element [X] provides the punchline, mostly through a combination of text and other semiotic means, such as images or short videos. Be like was used in example (4) as part of a meme with the viral image of a three-headed dragon, a funny drawing of the film monster King Ghidorah from the movie Godzilla: King of the Monsters.8 In addition, repetition also frequently includes multiword codeswitches into English, which are mostly taken from popular movies or song lyrics. Multiword codeswitches are full sentences or phrases from a source language (English) used within a stretch of discourse in a receptor language (German). The codeswitch “It’s been 84 years” in example (5) was taken from James Cameron’s 1997 production Titanic and is frequently used in memes along with an image of the elderly female character Rose to exaggerate a period of time that has passed while waiting for a particular event to happen.

- (4)

- Kostüme an Fastnacht be like:Meine Friends: Aang aus Avatar, Geralt aus The WitcherIch: Badewanne(Costumes for carnival be like:My friends: Aang from Avatar, Geralt from The WitcherMe: Bathtub)

- (5)

- POV: Du suchst einen Therapieplatz und bekommst sogar einenIt’s been 84 years.(POV: You look for therapy treatment and you’re actually offered a placeIt’s been 84 years.)

Furthermore, German derivates of widespread English memes such as Me, when [X] or Me [X], Also me [X] occur frequently throughout the corpus, as shown in examples (6) and (7). Personal and possessive pronouns used in captions of memes and meme reels are almost exclusively in first or second person (using the informal pronoun du). This way, the station directly addresses its target audience, expresses social proximity and creates a sense of in-group identity by adopting a personal point of view when referring to shared experiences of young Instagram users. Such is the case in examples (6) and (7). The image that was used as part of the meme for example (6) is the popular crying Boo driving image, a photo composition based on the little girl character Boo in the movie Monsters, Inc. by Pixar Animations. For example (7), the meme included an image which pictured a singer running excitedly across the stage of an award event with a smartphone in her hand.

- (6)

- Meine BFF und ich, wie wir mit jeweils 10 Fehlerpunkten9 und bodenlos viel Glück in der Prüfung durch die Gegend fahren:(My BFF and me, when we are driving around with 10 error points each and a lot of luck in the test:)

- (7)

- Ich, sobald meine Katze irgendwas Süßes macht:(Me, when my cat does something cute:)

Lastly, abbreviations are also frequently used in meme (example 8) and reel captions (example 9) produced by the station (see also Section 5.3). The acronym FOMO (fear of missing out) was used in example (8) as part of a meme featuring an ice-cream cone and a swimming pool. The abbreviation POV in example (9) was used in the caption of a reel thumbnail which shows a still of a video published by German Chancellor Olaf Scholz in which he answers questions of the public on his favourite things (e.g., soccer clubs, pets, favourite movie).

- (8)

- Warum FOMO bei gutem Wetter besonders kickt(Why FOMO kicks particularly well in good weather)

- (9)

- POV: Du hast ein Date mit einem People Pleaser(POV: You have a date with a people pleaser)

3. Methodology

This paper is based on a mixed methods approach applied as part of a larger linguistic ethnographic research project. The first two subsections discuss the ethnographic framework of the larger research project, and the final subsection outlines the corpus-based part of the study, the identification and quantitative analysis of anglicisms. To contextualise the quantitative corpus-linguistic results of anglicisms in youth radio Instagram content, the paper also draws on the findings of a previous study by the researcher which analysed possible factors facilitating the use of English in radio station imaging content produced by six German adult contemporary stations (Schaefer, 2019). Based on Winter-Froemel et al.’s (2014) study of possible facilitating factors in print media, the study on radio station imaging materials focused on word length, lexical field and pragmatic and semantic reasons. In addition, it analysed diachronic development of the pragmatic value of anglicisms, which turned out to be relevant in the context of radio language. The findings of the radio station imaging study showed that while some facilitating factors, such as brevity of expression and pragmatic value, are meaningful for radio language, comprehension by the target audience is overriding for the use of catachrestic and non-catachrestic anglicisms in radio imaging materials (Schaefer, 2019, 2024).

3.1. Linguistic Ethnography at the Youth Radio Station and Online Ethnography on the Station’s Instagram Profile

Most reasons for the use of English and the functions of anglicisms in media texts have so far mainly been described based on analyses of the final product of journalistic work—published media messages. The ethnographic fieldwork and qualitative interviews undertaken for this study therefore provide novel insights into the choices that journalists make when using English words and phrases for meme and reel captions from the perspective of the actual language users behind the scenes of online content production.

The paper draws on linguistic ethnographic fieldnotes taken at one of the largest youth radio stations in Germany, which broadcasts for a large urban area. Linguistic ethnography was undertaken for 4 weeks during weekdays for a pilot study in April 2023 conducted through the University of Nottingham and between mid-October 2023 and May 2024 conducted for the CIDoRa project through the University of Limerick. Fieldwork for the pilot study included general newsroom observation, of which 2 weeks were spent specifically with the online team. For the larger project, fieldwork included 24 days of general newsroom observation over a period of 7 weeks (up to 8 h per day, during weekdays). The researcher was given access to daily working routines and newsroom practices at the station, observed on-air and online content production and participated in daily briefings and feedback sessions for journalists held by the responsible duty editor. Newsroom observation was then followed by 48 days of individual observation of journalists, including presenters and radio hosts (up to 8 h per day, during weekdays). Individual observation of journalists at the station involved 17 journalists, of which two also worked for the online channels of the station (i.e., in the production of Instagram content). In addition, informal interviews with journalists after gathering information, writing and producing broadcasts and digital content allowed the researcher to obtain unprecedented insights into journalists’ linguistic choices and practices around the use of English in their content. Since it became clear to the researcher during the pilot study that many members of the online team frequently or exclusively worked remotely, their work and interactions during content production for Instagram was mainly observed by the researcher on the online team’s internal MS Teams channel (from mid-Oct 2023 to May 2024).10

Online ethnography on the station’s Instagram page for the present paper was undertaken from April to May 2023 and from October 2023 to early January 2025. A total of 980 memes, meme reels and reels were collected from the station’s Instagram page during this time. This includes the quantitative and qualitative analysis of meme and reel captions as posted on the station’s Instagram profile page (see Section 3.3).

3.2. Qualitative Interviews

As part of the larger CIDoRa project, 20 interviews were conducted face-to-face or online via MS Teams with journalists who participated in newsroom observation. Four of the interviewees worked in editorial positions (one specifically for online communication), ten journalists as radio hosts (two of these journalists were also employed as news presenters and one interviewee in the online Instagram team), two journalists as station imaging producers, one journalist as a podcast producer, one interviewee as a news presenter, one journalist in the radio station’s marketing section, and one interviewee worked in the music playlist production team. Interviews were approximately one hour in length and conducted with each journalist individually. All questions were asked in a semi-structured format, which means that while questions were prepared prior to the interviews, they only served as guidance and thereby allowed for flexibility and conversations to evolve with journalists. This qualitative interviewing method is useful for examining personal motivations, experiences and opinions on the use of English in media content production and to obtain further insights into the use of anglicisms in meme and reel captions by journalists as part of their daily online content production routines.11 Questions asked by the researcher related to the journalists’ work routines and practices of writing content and their attitudes towards using English.

Journalists were selected by the researcher based on their functions at the youth radio station and their availability and willingness to participate in the study. All journalists were between 18 and 40 years of age, and written informed consent for observation and interviews was obtained from all participants.

3.3. Identification and Quantitative Analysis of Anglicisms

Instagram data collected during online ethnography resulted in a corpus of approximately 12,200 tokens. This corpus is comparable in size with the corpus of the researcher’s previous radio station imaging study, for which English lexical items were searched in a corpus of 14,900 tokens. For analysing linguistic diversity in the form of English in meme and reel captions produced by the youth radio station, the researcher applies a definition of anglicisms that aims to closely resemble the actual language users’ language perceptions. This means that only word forms that appear as of English origin to speakers who have no background in linguistics but deal frequently with English at their workplace are considered in this paper. For the identification of anglicisms, the Instagram corpus was therefore manually searched by means of a synchronic analysis (see Onysko, 2007) to identify words that formally resemble or seem to be related to English lexical forms. As part of this first step, words that are graphemically or phonologically marked and therefore deviate from German spelling and/or pronunciation conventions were categorised as anglicisms. For the remaining word forms that were unmarked but showed considerable resemblance to English, several reference works were used for the detection and verification of anglicisms by means of etymological information. These included the Duden online (Dudenverlag, n.d.), the DWDS (Berlin-Brandenburgische Akademie der Wissenschaften, n.d.) and the German etymological dictionary KLUGE (Kluge & Seebold, 2011). As part of this step, English borrowings that are orthographically assimilated in German beyond changes in capitalisation (e.g., G. Streik vs. E. strike; G. Tipp vs. E. tip) were excluded because of their inconspicuous appearance. In a similar vein, other types of lexical items, such as loan translations or internationalisms that were borrowed into German through English, were excluded from the analysis. Proper nouns were also not considered as anglicisms in the analysis (in line with Onysko, 2007). For further examination, all anglicisms identified in the Instagram corpus were categorised according to Onysko’s (2007) typology of core anglicisms. These are borrowings, pseudo- and hybrid anglicisms, and codeswitches. Borrowings are English lexical items that are transferred as units of form and meaning from the source language (English) to the receptor language (German) and often undergo assimilation, such as capitalisation, in German. Examples from the online corpus include the anglicisms Club, Song and chillen (to chill).12 Pseudo-anglicisms are formed within German using English lexical material, and their meanings are therefore unknown to L1 speakers of English, such as in the case of the anglicisms Handy (mobile phone) and Oldtimer (vintage car). Hybrid anglicisms contain both German and borrowed English lexical material joined in a process of word formation, such as Streaming-Dienst (streaming service) and Baby-Nilpferd (baby hippopotamus). Additional criteria for determining the establishedness of an anglicism and for distinguishing between incipient borrowings and single-word codeswitches were adopted from the researcher’s previous work on these topics (for a detailed discussion, see Schaefer, 2021).13 This involved checking lexical items for usage and frequency in the ZDL Regionalkorpus (DWDS), the Neologismenwörterbuch of the IDS (Leibniz-Institut für Deutsche Sprache, 2006ff), and the German Web 2020 (deTenTen20) corpus available on Sketch Engine (https://www.sketchengine.eu, accessed on 10 January 2025). For the two language corpora of the DWDS and Sketch Engine, thresholds were determined for considering an anglicism as either established or novel (for the ZDL Regionalkorpus, 96 tokens and for the German Web 2020 (deTenTen20) corpus, 141 tokens).14,15

For the quantitative analysis of all anglicisms found in the Instagram corpus, core anglicisms excluding multiword codeswitches were counted as lexemes in types and tokens. English lexical items were counted as units of meaning, which means that compound nouns were counted as one token in the quantitative analysis. Since the study is designed as a corpus-assisted ethnographic study, only descriptive statistics are used to support the qualitative findings.

4. Possible Facilitating Factors

4.1. Pragmatic Markedness and Diachronic Development of Anglicisms

The use of anglicisms in media messages is often associated with achieving specific communicative goals (see Schaefer, 2021). Therefore, all anglicisms identified in the corpus were analysed for their pragmatic value. For this analysis, Onysko and Winter-Froemel’s (2011) distinction between catachrestic and non-catachrestic loanwords was applied, which is based on Levinson’s (2000) theory of presumptive meanings. This categorisation essentially distinguishes between loanwords that function as unmarked, standard terms (catachrestic loans bearing I-implicatures) and loanwords that have near-equivalents in the receptor language and therefore adopt additional pragmatic value (non-catachrestic loans bearing M-implicatures). For the catachrestic/non-catachrestic analysis, base anglicisms were extracted from all compounds and hybrid anglicisms (see Onysko & Winter-Froemel, 2011; Schaefer, 2019). Each English element of an English–English compound was therefore listed as an individual occurrence. For the determination of German near-equivalents for each of the non-catachrestic base anglicisms, the Duden online and the DWDS were used to identify German lexical items that would have provided a suitable alternative in context. In addition, the German near-equivalents’ acceptability in contemporary German was verified by the researcher, who is an L1 speaker of German.

Furthermore, according to Onysko and Winter-Froemel (2011), some non-catachrestic anglicisms undergo a diachronic evolution. In this process, anglicisms can partly lose their markedness (M-implicatures), become pragmatically unmarked like their German equivalents (sharing I-implicatures) and function as default terms in German. Each non-catachrestic anglicism was therefore also tested for such a possible diachronic development. Examples of non-catachrestic anglicisms that have undergone a diachronic evolution from pragmatically marked to unmarked cases are Hobby, Trainer and cool (for further examples see Table S1 in the Supplementary Materials).

4.2. Lexical Fields of Anglicisms

All anglicism lexemes found in the Instagram corpus were additionally categorised into lexical fields according to the context in which each anglicism token was used. Since linguistic and cultural resources are jointly mobilised in global cultural flows (see Appadurai, 1996), an analysis of lexical fields of English linguistic resources allows for insights into how cultural flows have an impact on the station’s content choice and language use on Instagram. In addition, the analysis of lexical fields shows how the youth radio station positions itself within these global cultural currents, as the mass media are themselves part of global cultural flows. In particular, it allows to investigate which cultural domains the station draws on to create its station image on Instagram and how the use of anglicisms contributes to this. Therefore, the analysis of lexical fields in this paper does not intend to make quantitative statements about the average frequency of anglicisms in each lexical field (i.e., the number of anglicisms measured against the total word count for the individual fields). Instead, it aims to explore the number of cases in which global cultural and linguistic flows are weaved into the station’s online content.

The list of lexical fields used for this paper is based on a list of lexical fields developed by Busse (1993) and further refined by the researcher in previous studies on anglicisms in radio language (see Schaefer, 2019, 2024). A total of 19 lexical fields were used to categorise anglicisms accordingly. In line with Winter-Froemel et al. (2014), if an anglicism lexeme showed tokens in two different categories or more, it was categorised in the lexical field of General Language. Lexical fields were examined based on anglicism lexemes rather than bases to make the online data comparable to an extended version of the station imaging paper’s original analysis that avoids the issue that many anglicism bases end up in the field of General Language due to the extensive use of compound nouns in German (see Schaefer, 2024). Examples of anglicisms in their lexical fields include Song (Music/Dance), Chat (Media/Communication/Entertainment)16 and Interview (Journalism).

4.3. Brevity of Expression

To examine whether brevity of expression is a facilitating factor for the use of English lexical items in the youth radio station’s Instagram content, all anglicism bases were considered for analysis. The in-depth examination of each token’s actual use in the corpus allowed the possible difference in length (in number of syllables) between anglicisms and their semantic near-equivalents to be measured in context. All anglicism types and tokens were then coded as either shorter, equal or longer. Pairs of near-equivalents where the anglicism is shorter than their German near-equivalent include the interjection hey versus hallo, the noun News versus Nachrichten, and the verb skippen (to skip) versus auslassen (for further examples see Table S1).

4.4. Semantic Reasons for the Use of Anglicisms

Previous research into English in German media has seldom investigated the use of English from the perspective of the actual language users and given insights into the language worlds and daily working routines of journalists when producing content (cf. amongst others Fiedler, 2022; Knospe, 2015). To investigate semantic reasons for the use of English linguistic resources by the youth radio journalists, the paper mainly draws on ethnographic observation and qualitative interviews. It thereby also gives insights into whether the use of English underlies the same semantic functions in the youth radio station’s online content as in adult contemporary radio station imaging (see Schaefer, 2019). In this context, several stylistic affordances that have been ascribed to anglicisms by previous research, such as conveying a sense of modernity or offering lexical variation, will be explored (cf. Gerritsen et al., 2007; Onysko, 2004; Pfitzner, 1978; Piller, 2003).

5. Results and Discussion

This section presents the combined linguistic ethnographic and corpus linguistic results for the use of English words and phrases in the youth radio station’s meme and reel captions. In addition, it compares the findings for Instagram content with the results of the previous study by the researcher on facilitating factors for the use of English in adult contemporary radio station imaging.

First, the findings for pragmatic markedness of borrowings and for the analysis of diachronic development in memes and reels are discussed and then compared to adult contemporary radio imaging. This also includes the results for the overall catachrestic/non-catachrestic analysis. Following the findings for lexical fields in which anglicisms appeared (see Section 5.2), the role that brevity of expression plays for the use of anglicisms in the Instagram content of the youth radio station is outlined, and the findings are then compared to radio station imaging of adult contemporary stations in Section 5.3. To contextualise and provide an in-depth interpretation of the overall quantitative findings of the analysis of Instagram content, the results section then presents further insights from ethnographic fieldwork and interviews with youth radio journalists on their use of English linguistic resources behind the scenes (see Section 5.4). It thereby also explores semantic reasons for the use of English words and phrases from the perspective of the youth radio journalists.

5.1. Pragmatic Markedness of Borrowings and Diachronic Development

Before moving on to discussing whether and how the pragmatic characteristics of English loanwords are relevant for their use in the youth radio station’s online communication, this section will first give a brief overview of the overall frequency of anglicisms in the Instagram corpus. The sample of 980 memes, meme reels and reels contained a total of approximately 12,200 tokens of text in their captions, in which 372 anglicism lexemes (amounting to 650 tokens)17 and 65 multiword codeswitches were identified. This results in an overall frequency of 5.34 anglicisms (units of meaning) per 100 words, which is higher than the anglicism frequencies found in other recent studies on the use of English in online data. Coats (2019), for example, determined an average of 1.50% of anglicisms in his corpus of random Twitter messages. Since his analysis was for illustration purposes only and based on a list of anglicism types that included lexical items that would not qualify as anglicisms in the present paper (such as Sport and Video), the difference in frequency may even be more pronounced. In relation to traditional media, the researcher’s study on anglicism use in adult contemporary radio showed that station imaging materials contained the highest density of English lexical items of all radio genres and featured an average of 5.41 anglicism units per 100 words (see Schaefer, 2024). The comparison of these results indicates that the high number of English lexical items found in the Instagram corpus is not exclusively due to the fact that online communication is analysed, but that the professional setting and promotional motivations of the station additionally seem to play an important role in the frequent usage of English in its online content (see also Section 5.4).

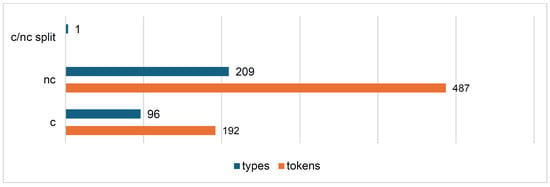

In terms of pragmatic value, 209 out of the 306 anglicism base types identified in the Instagram corpus show non-catachrestic features, and 96 types show catachrestic features.18 The lexical item live was found to occur in the form of both catachrestic and non-catachrestic tokens depending on the context of usage and was therefore categorised as a split item (for a more detailed discussion see Schaefer, 2019). Figure 1 depicts the predominance of non-catachrestic types in the Instagram content (nc 68.3%; c 31.4%), which is similar to the results for adult contemporary radio’s station imaging (nc 66.7%; c 31.4%). In terms of repetitive usage of catachrestic and non-catachrestic anglicisms, however, the radio station imaging corpus showed a higher rate of repetition for non-catachrestic types (nc: 10.54 tokens/type; c: 2.24 tokens/type) than the Instagram corpus (nc: 2.32 tokens/type; c: 1.98 tokens/type). From ethnographic observation and informal interviews with journalists at the youth radio station, it became evident that images and videos are frequently used by the station on social media as eye catchers for image-building purposes, whereas on radio, which is auditory only and where people tune in at different times, repetition is a key component of programming strategies and therefore generally more common than in other media. This is also in line with the findings of the researcher’s previous study on the use of anglicisms in adult contemporary radio station imaging, where non-catachrestic anglicisms were used repetitively by journalists on radio for attracting attention through their pragmatic markedness and for creating their station image (Schaefer, 2019).

Figure 1.

Pragmatic value of English lexical items in types and tokens.

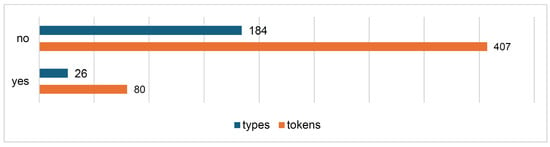

The analysis of the use of non-catachrestic anglicisms in the Instagram corpus that show diachronic development from bearing M- to I-implicatures (see Figure 2) also indicates that a loss of additional pragmatic value does not seem to constrain an anglicism’s use online. While 12.4% of the non-catachrestic anglicism bases in the online corpus show a diachronic evolution in terms of pragmatic value and have therefore lost their pragmatic markedness, these types contribute 16.4% of all non-catachrestic tokens found in the online corpus. This contrasts with the adult contemporary station imaging corpus, where results indicated quite the reverse. While non-catachrestic anglicisms with diachronic development amounted to 20.0% of non-catachrestic types in on-air imaging, these lexical items only amounted to 8.3% of all non-catachrestic tokens.

Figure 2.

Numbers of non-catachrestic English lexical items in the Instagram corpus that show and do not show a diachronic evolution of pragmatic markedness.

In sum, these data indicate that the focus on using pragmatically marked terms is not as pronounced in the creation of Instagram content as in the case of on-air station imaging (see also Section 5.4). Rather, the terms frequently used on Instagram are closely related to topics and issues within the lifeworlds of the targeted audience (e.g., social media and relationships) and, as confirmed by the journalists in informal interviews, also adopted from previously popular memes in the young audience’s bubble. Amongst the most frequent non-catachrestic terms in the Instagram corpus that have lost their pragmatic markedness are Club, Handy, Stress and Single. The lesser repetition of pragmatically marked anglicism bases in the online corpus can also be attributed to the medium and its characteristics. Due to the visual and/or audio-visual component and the non-transient nature of online communication, repetition does not seem to be as relevant as in radio station imaging, where repetition is key for on-air promotion due to radio’s function as a background medium. In line with the differences in the repetitive use of anglicisms between the two corpora, the number of different types of English lexical items in the corpus of Instagram content also appears as striking. The anglicism lexemes identified contained 306 different anglicism bases, whereas the corpus of adult contemporary radio station imaging materials only contained 102 different types of anglicism bases (Schaefer, 2019). This means that the language used on the youth radio station’s Instagram page shows more variation, which seems to be again due to the number of different topics discussed online. In the following section, the analysis of lexical fields outlines which topical areas are relevant for the use of English in the station’s online content.

5.2. Lexical Fields of Anglicisms on Instagram

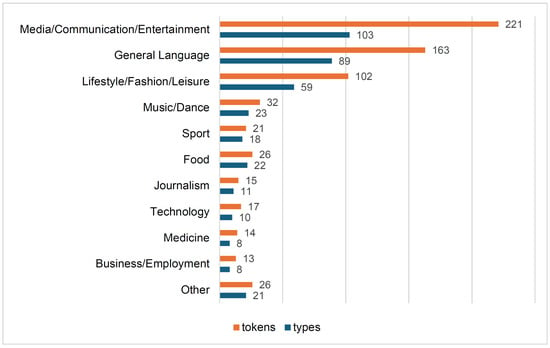

Most of the anglicisms found in the Instagram corpus were categorised into the lexical fields Media/Communication/Entertainment, General Language and Lifestyle/Fashion/Leisure (see Figure 3). Anglicisms in these lexical fields encompass many terms that are related to the interests and concerns of the station’s target audience and are part of their adolescent lifeworlds. Themes that regularly occurred throughout the corpus are social media trends, relationships, partying, work or study related issues, and financial difficulties. The particular prominence of anglicisms from the field of Media/Communication/Entertainment (28% of all anglicism lexemes; 34% of all tokens) shows that English mobile resources that emerge from cultural flows of global social media trends and media and entertainment consumption patterns play an important role in the station’s Instagram content. Besides General Language, the field of Media/Communication/Entertainment also featured the highest number of incipient borrowings. These also mostly relate to social media phenomena and trends, such as Rawdogging (travelling by plane without consuming any food, drink or entertainment) or creating and sharing Wrapped[s] (analytical summaries of users’ activities on streaming or social media platforms). Another significant part of the lexemes categorised in Media/Communication/Entertainment is related to the station’s coverage of music festivals that are attended by their target audience. The base anglicism Festival appears in 11 different anglicism lexemes, which together amount to 55 tokens.

Figure 3.

Overall distribution of English lexical items across lexical fields.

Due to the large variation of anglicism lexemes in the corpus (the type–token ratio for anglicism lexemes is 0.572, which means that on average there are less than two tokens per lexeme), only a small number of the English lexical items emerged as particularly salient in terms of frequency. Examples from the lexical field of Media/Communication/Entertainment that were particularly salient in terms of frequency related to social media phenomena. This includes the anglicisms Blind Ranking (23 tokens) and POV (21 tokens), which are used as catchwords in captions of repeatedly occurring categories of reels or memes.

In addition, the corpus also featured a number of English lexical items related to Camping at large festivals, which shows that the topic of attending festivals is also linked to the use of anglicisms related to cultural flows in the area of Lifestyle/Fashion/Leisure. For the lexical fields of General Language and Lifestyle/Fashion/Leisure, it was also noticeable that a range of English nouns were used to refer to people who are family members or social contacts, or to refer to people by means of their relationship status. More frequent examples include the anglicisms Friends, BFF, Crush and Dad. In a study of social media messages, Zenner et al. (2023) have shown that the use of English kinship terms and other person-reference nouns is also a feature of Dutch youth language. The use of these lexical items in the Instagram corpus therefore seems to be connected to wider cultural flows associated with social media communication. In addition, the adoption of core lexical items such as kinship terms also serves as an indicator of the increasing intensity of the use of English lexical items within German (see Onysko, 2007), which is in line with the progressive nature of youth language.

Besides those anglicisms categorised in the three top lexical fields, which together amount to 67% of all lexemes and 75% of all tokens, the use of English lexical items from other lexical fields was rather limited. Against the background that the Instagram content analysed represents the online appearance of the youth radio station, the low figures for the lexical field Music/Dance are rather unexpected. The only anglicism base that appears in considerable frequency in this category is Song (13 tokens). When one examines the station’s profile page on Instagram more closely, it additionally becomes evident that there is very little mention of the station’s radio offers. According to the online editor-in-chief, the online content of the station is not meant to provide a platform for promoting their radio programme. The station targets an even younger audience on Instagram that would only listen to the radio in the car with their parents but does not view the radio as a means of attaining information. One of the journalists working for the online team even explained to the researcher in an informal interview that many of their online followers are not aware that they are actually also a radio station. In comparison to the Instagram data, the adult contemporary station imaging corpus showed the highest number of tokens in the lexical fields of Music/Dance and Journalism. This was due to the repetitive use of non-catachrestic anglicisms in these fields for promoting the image, music and services of the adult contemporary radio stations (Schaefer, 2024).

Due to the online context in which anglicisms are used by the youth radio station on Instagram, the fact that a considerable amount of anglicisms can be categorised in the field of Media/Communication/Entertainment is not surprising. When taking a closer look into the distribution of catachrestic and non-catachrestic anglicism bases across lexemes in each lexical field in the Instagram data, however, it becomes evident that the field Media/Communication/Entertainment shows different tendencies than the other two top-ranking fields. Amongst the anglicism lexemes assigned to Media/Communication/Entertainment, more than half of all types and tokens contain catachrestic English bases (see Table 1). A considerable number of these lexemes containing catachrestic anglicism bases (43 types) are media- and social media-related terms. Examples include Deepfake and Oversharing. This indicates, on the one hand, that journalists have no other choice but to use these English terms when they refer to topics of global social media culture since catachrestic loanwords do not feature near-equivalents in German, which was also confirmed by some of the interviewees and the researcher’s ethnographic observations. On the other hand, the use of these catachrestic lexical items seems to be beneficial for the station’s image building. Since such anglicisms have been adopted from global cultural flows of the mediascape as units of concept (signifier) and word form (signified) without a prior concept in German, their use, as became evident from newsroom observation, allows journalists to express their content’s connection to global cultural flows on a conceptual level and—in particular in the context of catachrestic incipient borrowings—to current trends.

Table 1.

Number of anglicism lexemes in each lexical field that contain catachrestic/non-catachrestic anglicism bases.

5.3. Brevity of Expression

The results of the analysis of word length of non-catachrestic anglicisms and their possible German near-equivalents in the Instagram corpus are somewhat ambiguous. On the one hand, the results closely resemble those attained for adult contemporary radio station imaging in relation to types of base anglicisms. There are only a few anglicism types that are longer than their German near-equivalents, and there are considerably more terms that are shorter than their near-equivalents as there are terms that are equal in length (see Table 2). Like in the case of radio station imaging, this indicates that economy of expression might be relevant for the use of English lexical items online. In addition, abbreviations such as POV (as can be seen in examples (5) and (9)) were more frequently used amongst anglicism bases than in radio station imaging materials (for station imaging, 6 types and 17 tokens; for Instagram, 23 types and 60 tokens) (Schaefer, 2019). Further examples of abbreviations found in memes include the anglicisms BFF (best friends forever; see example (6)), FOMO (fear of missing out; see example (8)) and DM (direct message). According to one of the journalists working in the production of online content, abbreviations are not only a feature of social media jargon but also a significant feature of youth language of the Generation Z:

Also ich glaub Millennial Leute, die sind sehr in diesem Denglisch drin und so … äm … und Gen Z ist schon wieder in so Kürzeln drin.

(Well, I think millennial people are very much into this Denglisch and so on … em … and Gen Z is already into such abbreviations again.)

Table 2.

Length of non-catachrestic anglicism bases compared to German near-equivalents (measured in syllables).

When we consider the token frequency of anglicisms coded for length, however, it seems that anglicisms which are equal in length are on average used more repetitively (the type–token ratios are: shorter 0.513; equal 0.342; longer 0.472). For the adult contemporary radio station imaging corpus, quite the opposite was evident, with shorter anglicism bases showing a higher number of tokens than anglicisms of equal length.19 One possible reason for this is that spoken language on air needs to be catchier and therefore shorter to keep up listener attention and interest (Schaefer, 2024). In addition, according to the youth radio journalists, brevity of expression is more relevant in the context of the strict time constraints of radio broadcasting than in online content, where there are lesser space constraints.

In summary, the ethnographic findings and corpus data indicate that length does not necessarily seem to be a decisive factor for the use of English in the youth radio station’s Instagram content production. Like in the case of pragmatic markedness, it rather seems to be important to journalists to adhere to the online jargon of their community (see Section 5.4). The few notable exceptions of anglicisms in the Instagram corpus that are longer than their German near-equivalents additionally support the interpretation that youth and social media jargon are the dominant shaping factors in the data analysed. Examples of non-catachrestic expressions that are longer than their German counterparts are the quotative be like (which is also used to refer to mental states and emotions in the corpus) and Expectation (which featured as part of a widely known meme format that satirically contrasts an imaginative or desired state with the more unpleasant Reality).

5.4. Semantic Reasons for and Journalists’ Perspectives on the Use of English

Looking behind the scenes at media content production, the newsroom observation at the youth radio station has additionally revealed that journalists also use English linguistic resources frequently in their daily informal conversations at the workplace. Anglicisms are mainly used as part of expressing in-group youth identity20 and being up to date with the latest social media trends, which shapes journalists’ online and on-air content production. According to a journalist:

Und dann wird es [die Verwendung von Anglizismen] aber halt unterstützt dadurch, dass wir das auch im Sender schon viel benutzen. Also ich benutze die auch einfach viel, ich hab mich jetzt auch schon drauf eingestellt. Man ist einfach auch in nem jungen Kosmos bei Radio X, und deswegen ist das jetzt nicht erzwungen. Auch wenn ich mich mit Kolleginnen und Kollegen unterhalte, dann benutze ich die Wörter.

And he continued:(And then it [the use of anglicisms] is also supported by the fact that we also use it a lot at the station. Well, I just use it a lot, I’ve already adapted to it. You’re simply in a young cosmos at Radio X, so it’s not forced. Even when I’m talking to colleagues, I use these words.)

Viele Kollegen gerade aus der Onlineredaktion benutzen noch 10-mal mehr Anglizismen, die ich dann auch nicht mehr benutze.

According to the researcher’s observations, journalists work very interactively in the online newsroom and most of the time develop their ideas collectively through conversations. This usually includes anglicisms from the latest social media trends, which they later apply in their memes. Using anglicisms for the purpose of expressing modernity and internationalism has been explored by many previous studies, particularly in the context of advertising (Gerritsen et al., 2007; Onysko, 2004; Piller, 2003; Hornikx & van Meurs, 2020; Kelly-Holmes, 2005). While the results for adult contemporary station imaging revealed that not all adult contemporary radio journalists agreed that they use anglicisms for reasons of expressing modernity (Schaefer, 2019), the qualitative interviews and linguistic ethnographic fieldwork at the youth radio station have shown that using English particularly beyond established loanwords is a phenomenon of German youth culture and of expressing modernity. A host explained:(Many colleagues in the online team use 10 times more anglicisms, which I wouldn’t be using.)

Ich würde sagen, dass viele Menschen jetzt auch viel besser Englisch sprechen als früher vielleicht noch und … ja, ich glaub einfach, […] man ist so weltoffener, man ist viel vernetzter weltweit. Also ist es ja auch wichtig die Begriffe zu benutzen und ich würde schon sagen, natürlich ist ja Sprache auch so n bisschen Ausdruck von der Jugendkultur. […] Der Jugend is [Englisch] schon wichtig auch so bisschen zur Identifikation. […] Ich glaube, man will halt da zeigen, dass man so ein bisschen weltoffen ist, international unterwegs ist, dass man weltweit gerne mit Menschen auch in Kontakt tritt … also man konsumiert nicht nur Dinge mehr aus dem eigenen Land oder aus dem eigenen Umkreis, sondern die Kreise sind viel weiter in denen man sich bewegt durch das Internet auch, würde ich sagen, und da braucht man ja auch Englisch.

In line with the journalist’s statement regarding a greater competence of English amongst German youth, a more extensive use of English is also evident in the Instagram corpus, which contained more complex syntactic structures of English and novel anglicisms than the adult contemporary station imaging corpus. The online corpus contained 45 novel anglicism types amounting to 114 tokens, including the anglicisms be like (18 tokens), Blind Ranking (23 tokens) and Hottake (10 tokens). In addition, amongst the 12 top lexemes in terms of frequency, 5 types in the online corpus constitute incipient borrowings such as Friends (12 tokens) and Crush (7 tokens). In contrast, novel anglicisms in the radio station imaging corpus only showed 2 types and 2 tokens. Furthermore, the online corpus also contained 53 types of multiword codeswitches resulting in 65 tokens of these occurrences as opposed to the station imaging corpus, which contained no multiword codeswitches at all. As can be taken from the corpus analysis, while many novel anglicisms and multiword codeswitches are often not explained or translated in meme and reel captions, such unestablished anglicisms—according to most interviewees—are nevertheless very much known to their Instagram community and would otherwise not be used by journalists without a translation. While multiword codeswitches require a certain degree of proficiency in English, all codeswitches found in the online corpus either, as outlined before, are related to popular movie scenes or are commonly known to the station’s audience from other memes or song lyrics, such as in the following example.(I would say that many people now speak English much better than they used to and … yes, I just think [...] people are much more cosmopolitan, much more networked worldwide. That’s why it’s important to use the terms, and I would say language is, of course, somehow an expression of youth culture. [...] It [English] is important for young people for their identity. […] I think one wants to show that one is a bit cosmopolitan and international, that one likes to get in touch with people around the world ... so one no longer only consumes things from one’s own country or locality, but the circles in which one moves are much wider thanks to the internet, I would say, and that’s where you need English.)

- (10)

- I just wanna be part of your symphony.

Example (10) is a frequently used codeswitch in memes in analogy to the 2017 song Symphony by Clean Bandit and Zara Larsson. Constructing internet memes with this codeswitch is a social media trend where people upload images and videos with rainbows and dolphins along with a text overlay or the chorus of the song. In addition, like for adult contemporary radio (Schaefer, 2024), comprehension, as the researcher was told by one of the youth radio journalists, is also important for the production of memes and reels, and journalists are careful not to use a term that is key to understanding a message but may not be understood. According to one of the online journalists:

Heute wollte ich Prediction benutzen für die Bundesliga-Prediction und ich finde dieses Wort, das sage ich auch wirklich, weil Vorhersage finde ich ein blödes Wort, also passt überhaupt nicht zu dem, was es ist. […] Habe es nicht genommen, weil gibt halt schon viele, die mit Vorhersage mehr anfangen können als mit Prediction.

(Today I wanted to use Prediction for the Bundesliga prediction, and I find this word, which I really use because I find Vorhersage a stupid word, so it doesn’t fit at all with what it is. […] I didn’t use it because to many people Vorhersage says more than Prediction.)

On top of achieving comprehensibility, it became further evident from observation in the online and radio newsrooms of the youth radio station that journalists are specifically chosen to have the same age and interest as the main targeted audience members. It therefore seldom occurs that audience members complain about their use of anglicisms, and if so, complaints usually originate from people who are older than their actual targeted audience. According to a host:

Wir hatten gestern einen Call-in, der hieß „Was sind underrated Orte in X und X?“ und ich finde also ein deutsches Wort dafür ... also ich finde underrated drückt genau das aus, was ich gerne sagen will. Ich würde sagen, jeder in unserer Zielgruppe versteht, was ich mit underrated meine. Ich hab das natürlich nochmal erklärt, ich hab gesagt, „Orte an die wir unbedingt mal hin gehen müssen, die vielleicht nicht jeder kennt“ und so. Trotzdem wurde sich darüber aufgeregt, dass ich das gesagt hab … per WhatsApp. […] Ich würde aber sagen, vom Namen her war es wahrscheinlich auch eine eher ältere Person. […] Und ich würde behaupten, dass wir bei uns auch mehr Leute so [mit Englisch] erreichen.

(We had a call-in yesterday that went like “What are underrated places in X and X?”, and I find a German word for it ... I think that underrated expresses exactly what I want to say. I would say that everyone in our target group understands what I mean by underrated. Of course, I explained it again, I said “places we absolutely have to go to that perhaps not everyone knows about”. Nevertheless, someone got upset that I said that … via WhatsApp. […] I would say that according to the name it was more of an older person. […] And I would say that we also reach more people that way [using English].)

As stated in Section 5.1, most anglicism types used in the online corpus are marked. The interviews with journalists further revealed that non-catachrestic anglicisms are used online because they carry specific meanings and additional pragmatic effects and often bring it straight to the point (Pfitzner, 1978; Schaefer, 2024). However, as also became evident from the interviews with the youth radio journalists, markedness of an anglicism does not necessarily mean that a word makes it into their online content. The most frequently used pragmatically marked anglicism in the adult contemporary radio station imaging corpus was Hit (Schaefer, 2019, 2024). For adult contemporary radio journalists, Hit was regarded as the more appropriate term to describe rock and pop music than Lied, which according to them is much more likely to be associated with a children’s song. The quantitative analysis of anglicisms in the youth radio station’s online corpus, however, showed that Hit occurred not once in the corpus. According to one of the online journalists:

Na, wer sagt denn noch zu nem Song Hit? Also jeder Song, der auf TikTok viral geht, ist dann ein Hit und äh, das ist einfach nur ein Song. Wir nehmen viral. Song ist viral gegangen. Weil aus der Betrachtung dessen, dass die auf TikTok erfolgreich sind und dann ins Radio kommen. Die [Adult Contemporary Sender] nehmen ja Hit und sagen, „wir sagen euch, was die coolen Sachen sind“ und das passt auch zur Zielgruppe. Aber wir gucken halt ins Internet was cool ist.

From this journalist’s statement, it again becomes evident that whether an anglicism is chosen often does not depend on whether it bears additional pragmatic meaning but rather on whether it is regarded as used in the youth radio station’s online community. In this context, the newsroom observation at the station revealed that conveying modernity (see also Gerritsen et al., 2007; Piller, 2003), as stated above, is not necessarily achieved through the use of established pragmatically marked anglicisms but much more through the use of novel anglicisms and multiword codeswitches.(Well, who would still say Hit to a song? So, every song that goes viral on TikTok is then a Hit and em, that’s just a song. We say viral. The song has gone viral. Because from the point of view that they are successful on TikTok and then are played on radio. They [adult contemporary radio stations] use Hit and say “we tell you what the cool stuff is” and that fits the target group. But we look on the internet to see what’s cool.)

Concerning other semantic reasons, the use of anglicisms along their German near-equivalents for achieving lexical variation has been identified by previous research as a frequent function of anglicisms (see also Onysko, 2004; Pfitzner, 1978). Variation, however, seems to be only partially relevant in the context of the station’s online content. While for radio station imaging, journalists used anglicisms for variation purposes within one or between station imaging elements to sound attractive to the listener (Schaefer, 2019, 2024), only some anglicisms are used interchangeably in the online corpus. One example of this is the anglicism Weekend, which is used interchangeably with the abbreviation WE or German Wochenende. Most anglicisms therefore appear exclusively without their German counterpart, such as the loanword Story (where no token was found for its near-equivalent Geschichte). This indicates that for some non-catachrestic anglicisms, the German counterpart appears as inappropriate to use for addressing the youth radio station’s online community.

6. Conclusions

This paper has set out to examine the use of English linguistic resources in a professionally produced Instagram corpus of internet meme and reel captions as part of a larger ethnographic research project on representations of ethnic and linguistic diversity in German youth radio. The findings of the study present ethnographic insights gained from behind the scenes of media content production at one of the largest youth radio stations in Germany and interview statements by youth radio journalists on their use of English linguistic resources. Furthermore, an analysis of whether factors facilitating the use of anglicisms identified in a previous study by the researcher on the use of English in adult contemporary radio station imaging are also factors facilitating the use of English in professional produced Instagram content was conducted. While the quantitative analysis only gave limited insights into the use of English in the Instagram corpus, the ethnographic observations and interviews with the youth radio journalists gave unprecedented insights into journalists’ language worlds and practices of using English linguistic resources.

For the possible facilitating factor of diachronic development, the analysis of anglicisms found in the Instagram corpus shows that pragmatic markedness of an anglicism when used online does not seem to be as relevant as in adult contemporary on-air station imaging. While most non-catachrestic anglicism types are pragmatically marked in the Instagram corpus, those terms that have lost their markedness show above-average token frequencies. In contrast, for radio station imaging, a loss of pragmatic markedness was found to be a constraining factor for the use of anglicisms on air. This difference is mainly due to the characteristics of social media language and the language used in radio station imaging, where the latter focuses more on the promotion of the station’s music format and playlist through the repetitive use of pragmatically marked words. In addition, whether an anglicism is chosen in the youth radio station’s online communication often does not depend on whether it bears additional pragmatic meaning but on whether it is regarded as used in the youth radio station’s online community.

For brevity of expression, the findings show that—while most anglicism types are shorter than their German near-equivalents—there seems to be no particular focus on using shorter anglicisms repeatedly to create catchy language, as was the case for station imaging. Shortness of an anglicism is therefore not necessarily a decisive factor for the use of English in online content production. Like in the case of pragmatic markedness, as became evident from ethnographic fieldwork, it rather is important to the interviewees to adhere to the online jargon of their community.

The findings for lexical field showed that the field of Media/Communication/Entertainment contained the highest number of anglicisms, which is not surprising and mainly due to the online context in which the anglicisms are used. Taking a closer look at the distribution of anglicisms in the three top lexical fields, however, showed that Media/Communication/Entertainment indicates different tendencies than the other two top-ranking fields. More than half of the anglicism lexemes (types and tokens) in this lexical field contain catachrestic English bases, and a considerable number of these lexemes are media- and social media-related terms. On the one hand, as also confirmed by some of the interviewees and the researcher’s ethnographic observations, this shows that journalists have no other choice but to use these English words when they refer to topics of global social media culture; on the other hand, the use of these catachrestic lexical items is beneficial for the station’s image building. Many of the catachrestic anglicisms in the corpus are adopted from the mediascape as units of novel concept and novel word form, allowing journalists to show their content’s connection to global cultural flows and current trends on a conceptual level.

Looking into semantic reasons for the use of anglicisms from the perspective of the youth radio journalists has revealed that while conveying modernity seems to be a facilitating factor for the use of established anglicisms in their content, using novel anglicisms and multiword codeswitches appears to be the most dominant marker of expressing modernity and in-group youth identity with their online community. In this context, while being important for online communication, the comprehensibility of an anglicism is not measurable by a word’s established status in everyday German, like for adult contemporary radio station imaging, but rather by whether it is known to members of their youth community. This is also why journalists are employed who match with the interests and age of their online audience at this youth radio station.

In terms of using English for variation purposes, the results show that only seldom a non-catachrestic anglicism and its German near-equivalent appeared together across the corpus. This contrasts with station imaging, where lexical variation was mentioned by journalists as a welcome feature of anglicisms.

Looking at the overall results, it remains to be said that journalists working in the online newsroom of the youth radio station have mostly different motivations for and attitudes towards the use of English than adult contemporary radio journalists. While most adult contemporary stations invest quite some effort in using pragmatically marked English resources for promoting their music playlist and format in their imaging elements, youth radio journalists use English resources in meme and reel captions that are regarded as trending in their online community. In line with the mission of the station’s Instagram profile page to mainly provide an information service through entertainment to young people, English therefore is mainly used by journalists as a marker for in-group youth identity and for social bonding with their young audience. While for station imaging on adult contemporary radio the listeners are told what is cool by the station and are introduced to the latest hits and trends—which is why one should seemingly listen to it—the youth radio station’s take online is to pick up what already went viral on the internet to connect with their audience on eye-level. Through this approach of positioning itself within its community, the station ultimately promotes itself and its information and entertainment products.

Against the background that the journalists participating in the current study are the next generation of media professionals and will eventually move on to other outlets in their future careers, the data gathered in this study may to some extent provide an indication as to the future trends and developments of the use of English in German media language. For Blommaert (2010), Pennycook (2020) and Canagarajah (2013), one of the trends associated with global cultural mobility is that the socially constructed boundaries between named languages such as English and German will increasingly blur and become less significant. The use of multiword codeswitches on a regular basis in mass media communication is surely only one indicator for such linguistic hybridity and the increased mobility of global Englishes. Since language is a social practice, constantly subject to the ever-changing sociocultural environments in which it is used, future research in this area should engage more closely with the lifeworlds of the actual language users to obtain an emic perspective on their use of English. This could be achieved with larger ethnographic studies that combine mixed methods to explore different media and acknowledge the often hidden language worlds behind the scenes of media content production.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/languages10050096/s1, Table S1: Top 100 list of anglicism bases found in the youth radio station’s Instagram corpus.

Funding

This research was funded by the European Union’s Horizon Europe framework programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions grant 101109963.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Research Ethics Committees of the University of Limerick (reference no. 2023-09-11-AHSS) and the University of Nottingham (reference no. R2223/049).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available due to ethical restrictions and the protection of the identity of participants. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The term meme was coined by Dawkins (1976) to compare the way cultural behaviours and artefacts are passed on with the biological transmission of genes. In its original sense, it relates to any form of cultural activity that is either taught or learned through observation and imitation (e.g., language, music or fashion). Internet memes are considered as “a piece of culture, typically a joke, which gains influence through online transmission” (Davison, 2012, p. 122). In this paper, however, the term meme will be used in its colloquial sense as referring to an individual (humorous or interesting) item of creative output combining image/video and text overlay that is widely spread online. |

| 2 | Reels are short videos posted on a social media website. |

| 3 | Adult contemporary stations mostly play contemporary pop music and target an audience between 25 and 49 years of age. Adult contemporary radio station imaging constitutes short radio elements sung and/or spoken to promote a station’s hosts and presenters, its music and events organised by a station. This includes radio jingles, openers, stingers, claims, a station’s ID and trailers. |

| 4 | As an alternative to distinguishing between necessary and luxury loans, Onysko and Winter-Froemel (2011) draw on Levinson’s (2000) theory of presumptive meanings to develop the classification of catachrestic and non-catachrestic innovations. See also Section 4.1. |

| 5 | The radio station’s Instagram profile page functions as a means of the station’s online self-advertisement contributing to the station’s image. Against this background, Instagram users are first drawn to the actual image of the memes and to the thumbnails of reels and the captions on them. In order to best compare results of the Instagram corpus with the radio station imaging corpus, spoken content of reels and meme reels was therefore not included in the analysis. |

| 6 | For anonymisation purposes of the station and its journalists, memes and reel thumbnails produced by the station cannot be included. |

| 7 | The name of the youth radio station (replaced with the pseudonym Radio X) as well as the names of journalists cannot be disclosed for anonymisation purposes. |

| 8 | Information about viral images used in memes were retrieved from the meme database KnowYourMeme. https://knowyourmeme.com/ (accessed on 26 January 2025). |

| 9 | The word Fehlerpunkte (error points) relates to the German driving test, in which the learner driver can have a maximum of 10 error points to pass the theory part of the test. |

| 10 | Ethical approval for ethnographic research including interviews was given by the Research Ethics Committees of the University of Nottingham and the University of Limerick. |

| 11 | Statements made by interviewees in this paper express their personal opinions only and do hence not necessarily represent the opinion of the station where they are employed. |

| 12 | Glosses are provided for English lexical items that have experienced orthographic assimilation beyond capitalisation of nouns or semantic change in their usage by German speakers. If no glosses are provided, the example terms given closely resemble the original English lexical items in form and meaning. |

| 13 | Based on the proposition that borrowings and single-word codeswitches are the extremes of a continuum of usage (Matras, 2009; Myers-Scotton, 1993), the term incipient borrowings is used in this paper to refer to an intermediate stage between established borrowings and single-word codeswitches. |

| 14 | These threshold values are based on a study by Gottlieb (2015). |

| 15 | Novel anglicisms are English words and phrases that are “not yet commonly accepted as neologisms by speakers of German. An anglicism is regarded as novel and therefore not yet commonly accepted in German … if it (a) is a distinctive combination of word form and meaning not detectable in a common dictionary or even in its more current online version and (b) can only scarcely be found in regularly updated online corpora. Novel anglicisms are therefore not yet part of general language usage by the broader population and include one-offs and ad hoc formations” (Schaefer, 2021, p. 572). |

| 16 | While the lexical field Media/Communication/Entertainment appears rather broad, combining these three categories proved to be useful in the context of radio language in previous studies by the researcher since many anglicisms fit into all three categories simultaneously. Examples from the Instagram corpus of the youth radio station include the anglicisms Influencer and Streaming-Dienst (streaming service). |

| 17 | The anglicism lexemes identified included 258 borrowings, 102 hybrids, 7 pseudo-anglicisms and 5 single-word codeswitches. |

| 18 | A top 100 list of anglicism bases can be found in the Supplementary Materials Table S1. |

| 19 | For non-catachrestic anglicisms that are longer than their near-equivalents, it must be noted that the results of the Instagram and the radio station imaging corpus are largely determined by the repetitive use of one lexical item. In the case of the Instagram data, be like amounted to 18 out of 36 tokens. For adult contemporary radio station imaging, the loanword Service amounted to 50 out of 63 tokens that were longer. |

| 20 | Previous research into loanwords has also shown that loanwords are frequently used to convey in-group identity (see Zenner et al., 2019; Leppänen, 2007). |

References

- Appadurai, A. (1996). Modernity at large: Cultural dimensions of globalization. University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Berlin-Brandenburgische Akademie der Wissenschaften. (n.d.) DWDS—Digitales Wörterbuch der Deutschen Sprache. Available online: https://www.dwds.de/ (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Blommaert, J. (2010). The sociolinguistics of globalization. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Busse, U. (1993). Anglizismen im Duden: Eine Untersuchung zur Darstellung englischen Wortguts in den Ausgaben des Rechtschreibdudens von 1880–1986. Niemeyer. [Google Scholar]

- Canagarajah, S. (2013). Translingual practice: Global Englishes and cosmopolitan relations. Routledge. [Google Scholar]