Abstract

Although verb clusters in Continental West Germanic varieties are a well-researched topic, their derivation and the possible functions of their variants are still not yet fully understood. Both issues are discussed in the present paper, which is based on the translations of 46 English, Spanish, or Portuguese stimulus sentences by 321 North and South American speakers of Mennonite Low German. In order to analyze the variation in clause-final two-verb clusters, we focus on three structural factors, namely (i) the auxiliary verb, (ii) the structural link between the auxiliary verb and the main verb, and (iii) the type of the subordinate clause in which the cluster occurs. Regarding the first and the second factor, we will employ the cartographic approach in order to explain the impact of different auxiliary verbs. Regarding the third factor, it is somewhat surprising that the potential effect of the subordinate clause on the distribution of different cluster variants has received little attention in the research literature. Clause type will be shown to have such an effect and, therefore, we will assume that the speakers of MLG use different variants deliberately to indicate different degrees of clausal integration.

1. Introduction

An important aim of this paper is to relate the theoretical insights of the cartographic approach to the variation in clause-final two-verb clusters found in real production data. In doing so, we follow a desideratum mentioned by Boeckx (2011, p. 205): “There is indeed very little substantive discussion of the issue of linguistic variation in the context of the Minimalist Program”. In addition to the frequent lack of a substantive discussion, the equally frequent lack of a reliable and sufficiently large empirical base in studies within the generative framework is problematic (cf., e.g., Adli et al., 2015, pp. 12–17 and the literature cited therein). Rizzi (in Quarezemin, 2020, p. 6) mentions the potential risks of this state of affairs: “[I]n the absence of such a constant enrichment and exchange with the empirical dimension, the theoretical work risks to become sterile, and not raise enough interest in the scientific community”.

We will attempt to raise this interest by studying the linguistic behavior of 321 Mennonite informants from six communities in the Americas. Between 1999 and 2002, each of them was asked to translate 46 English, Spanish, or Portuguese stimulus sentences into Mennonite Low German (henceforth MLG). The resulting dataset, which is available online (cf. Kaufmann, 2018), contains approximately 14,500 tokens.1 About 4500 of these tokens contain clause-final two-verb clusters in subordinate clauses. Due to this robust number and due to the comparability of the stimulus sentences, advanced statistical analyses can be applied (cf. Section 4). In most empirical aspects, the present paper draws on Kaufmann’s habilitation thesis (cf. Kaufmann, 2016); however, the application of the cartographic approach is novel, not only in comparison to Kaufmann (2016) but also in comparison to the discussion of verb clusters in general (cf. Kaufmann, 2023, pp. 377–385 for a first attempt). The cartographic approach has been chosen because it combines the analysis of different structural positions within the split IP domain (in our case embodied by the different auxiliary verbs) with different serialization patterns (in our case embodied by the different cluster variants). Wiltschko (2014, p. 11) calls this the “[u]niversality of linearization and categorization”.

The paper is organized as follows: while Section 2.1 provides a historical sketch of the Mennonite communities in the Americas, Section 2.2 presents a brief introduction to the method of data elicitation. Section 3.1 then discusses the role of verb projection raising (henceforth v-p-r) and scrambling in the derivation of clause-final two-verb clusters, whereupon Section 3.2 introduces the three structural factors we consider crucial for the variation between the different cluster variants. In this section, we also discuss the use of the cartographic approach and present four crucial hypotheses. Section 4 then statistically analyzes the relevant tokens in order to verify these hypotheses. Section 5 provides a brief conclusion.

2. Mennonites in the Americas

2.1. A Brief Historical Sketch

The origins of the Mennonites in the Americas can be traced back to Eastern Holland, Friesland, Flanders, and what is now Northwestern Germany. Anabaptist communities formed in these regions during the Reformation. Because of religious persecution, many of these Anabaptists emigrated to West and East Prussia in the 16th century. There, a koiné was formed from the Continental West Germanic varieties the Mennonites had brought with them and the local varieties of Low German. In addition, the Mennonites began to use Standard German (henceforth StG) instead of Dutch for official purposes such as worship and education. When the Prussian government imposed stricter rules in the 18th century, many Mennonites accepted an invitation by Catherine II to settle in the recently conquered territories of “New Russia” (today Ukraine!). The first settlers arrived in 1789 and founded the colony Chortitza. In 1803, a second colony was founded and named Molotchna. Due to the different periods of emigration, the slightly different geographic origins, and the different social backgrounds of the emigrants, two MLG varieties developed, one in Chortitza and one in Molotchna, with the Molotchna variety enjoying more prestige (cf. Siemens, 2012, pp. 30–70 for a detailed discussion).

At the end of the 19th century, Russian officials introduced laws to ensure a certain degree of integration, prompting the more conservative Mennonites from Chortitza in particular to emigrate to Canada around 1870. During and after World War I, the situation of German-speaking immigrants also became difficult in Canada. Once again, the more conservative members did not yield to outside pressure and moved to either Mexico, where most of them settled in the state of Chihuahua (the region of Ciudad Cuauhtémoc; today approximately 40,000 people with a Mennonite background; 103 Mennonites took part in the translation task), or to Paraguay, where they set up the colony of Menno (9000 people; 44 informants). Mennonites from Mexico founded various daughter colonies in Belize and one in Seminole, Texas (4000 people; 73 informants). Mennonites from both Mexico and Menno also founded several daughter colonies in the region of Santa Cruz de la Sierra in Bolivia (50,000 people; eight informants with a Menno background).

The Mennonites who stayed in Russia in 1870 modernized their school system and placed more emphasis on StG. Due to their economic success, these Mennonites faced severe persecution when Stalin gained power in 1927. Because of these unfavorable prospects, many Mennonites, most of them from Molotchna and its daughter colonies, attempted to leave the Soviet Union and, in 1930, some succeeded in emigrating to Canada, Paraguay (colony of Fernheim; 4000 people; 37 informants), and Brazil (Colônia Nova in Rio Grande do Sul; 1000 people; 56 informants).

These different migration paths have resulted in different language repertoires. In addition to MLG and StG, the repertoires normally include the majority language of each community’s home country and, quite often, English as an international language. The heritage language MLG is still the unrivaled in-group language in Mexico, Bolivia, and the Paraguayan colony of Menno. It is weakest in the United States and Brazil, the two communities where competence in the majority language, English and Portuguese, respectively, is strongest. Aside from this, there are some families in the Paraguayan colony of Fernheim that use StG instead of MLG at home. Today, both Paraguayan communities, not only the Molotchna-based one in Fernheim, benefit from their modern school system, in which StG is not only taught as a subject but is also used as a language of instruction. Thus, in Paraguay, and to a lesser extent in Brazil, StG can still be seen as a roofing variety (Dachsprache) that exerts a certain influence on MLG. Admittedly, most Mennonite schools in the Chortitza-based communities in the USA, Mexico, and Bolivia also use and teach StG, but their StG must be considered a mere hagiolect that hardly influences the respective MLG varieties.

Of the 321 informants, 192 claim MLG to be their dominant language (59.8%). Another 29 informants indicate having comparable knowledge of MLG and one of the majority languages (9%; 10 in Brazil; 10 in the USA), and twelve do so with respect to MLG and StG (3.7%; 9 in Paraguay). One Paraguayan informant indicates having comparable knowledge of MLG, StG, and Spanish. In contrast, seventy informants claim one of the majority languages to be their dominant language (21.8%; 39 in the USA; 19 in Brazil); 17 attribute this status to StG (5.4%; 16 in Paraguay). Importantly, the 87 informants with a dominant language other than MLG still speak their heritage language (very) well. On average, they reach 9.9 out of 14 possible points for their competence in MLG.2

2.2. Data Elicitation

With a few exceptions, the sentences were presented in the respective majority language. Only 19 of the 184 Mexican and Paraguayan informants preferred English over Spanish, mostly because they had spent some time in Mennonite communities in Canada and/or the United States. Importantly, the different stimulus languages had no measurable effect on the distribution of the cluster variants. In any case, the three languages do not differ too much with regard to their verb syntax. They are all SVO, and neither of them shows a marked difference between root and subordinate clauses. Moreover, the fact that English, Spanish, or Portuguese were used as stimulus languages rather than StG not only allowed more Mennonites to participate but also greatly reduced possible priming effects. The stimulus sentences were read to the informants one by one, and the informants translated them immediately, without the help of a written version. Crucially, 16 of the stimulus sentences were modeled to elicit clause-final clusters with one finite and one non-finite verb (either a modal verb with a bare infinitive or a temporal auxiliary with a past participle). These sentences represent four sentence compounds with complement clauses, four with causal clauses, four with conditional clauses, and four with relative clauses (cf. Kaufmann, 2016, pp. 19–42 for detailed information on all stimulus sentences). Apart from this, the translations of many stimulus sentences that aimed at eliciting subordinate clauses with one verb actually produced two verbs due to the appearance of either the optional irrealis/aspectual auxiliary dune (‘do’; cf., e.g., (8a) and (19), respectively) or the inchoative auxiliary woare(n) (‘will’), an optional marker for future tense (cf., e.g., (8b)). Just like modal verbs, these auxiliaries govern a bare infinitive.

3. Verb Clusters in Mennonite Low German

3.1. The Role of Verb Projection Raising and Scrambling

Due to constraints of space, we will not be able to offer exhaustive discussions for our basic assumptions (cf. Kaufmann, 2016, pp. 43–63 for this). However, we will illustrate these assumptions by means of the translations in (1a–c).

| stimulus <15> | Portuguese: Se ele tiver que vender a casa agora, ele vai ficar muito triste. | |||||||||||

| Spanish: Si tiene que vender la casa ahora, se va a poner muy triste. | ||||||||||||

| English: If he has to sell the house now, he will be very sorry. | ||||||||||||

| (1) | a. | wann | dei | nü | dat | Hüs | verköpe | mut | ||||

| if | he | now-ADV | [the | house]-ObjDP | sell-V2 | must-V1 | ||||||

| [0.5] | dann | wird | dei | sehr | trürig3 | |||||||

| [0.5] | turns | he | very | sad | ||||||||

| (Bra-59; f/56/MLG)4 | ||||||||||||

| b. | wann | hei | nü | mut | dat | Hüs | verköpe | |||||

| if | he | now-ADV | must-V1 | [the | house]-ObjDP | sell-V2 | ||||||

| wird | hei- | ihm | dat | sehr | leid | sene | ||||||

| will | him | that | very | sorry | be | |||||||

| (Men-43; m/27/MLG) | ||||||||||||

| c. | wann | hei | nü | dat | Hüs | mut | verköpe | |||||

| if | he | now-Adv | [the | house]-ObjDP | must-V1 | sell-V2 | ||||||

| dann | wird | hei | sehr | trürig | sene | |||||||

| will | he | very | sad | be | ||||||||

| (Bra-60; f/40/MLG) | ||||||||||||

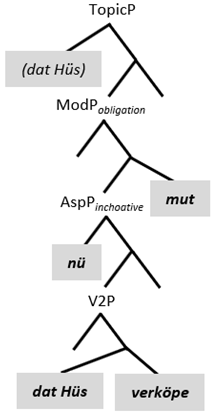

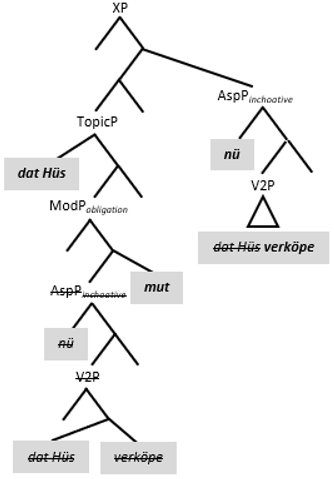

The three translations contain the modal verb mute(n) (“must”) and the main verb verköpe(n)5 (“sell”). In (1a), the ObjDP dat Hüs (“the house”) precedes the main verb verköpe, labeled V2, which in turn precedes the finite modal verb mut, labeled V1. Thus, this construction shows a strictly left-branching sequence ObjDP-V2-V1, i.e., V1 governs V2 to the left and V2 governs the ObjDP to the left. We will call this sequence the NR variant (non-raising variant) because we assume that the V2P (dat Hüs verköpe) remains in its base position. The tree in (2), which only displays the relevant phrases in the IP and the VP domain, presents the structure of (1a) (phonetically realized elements appear in bold).

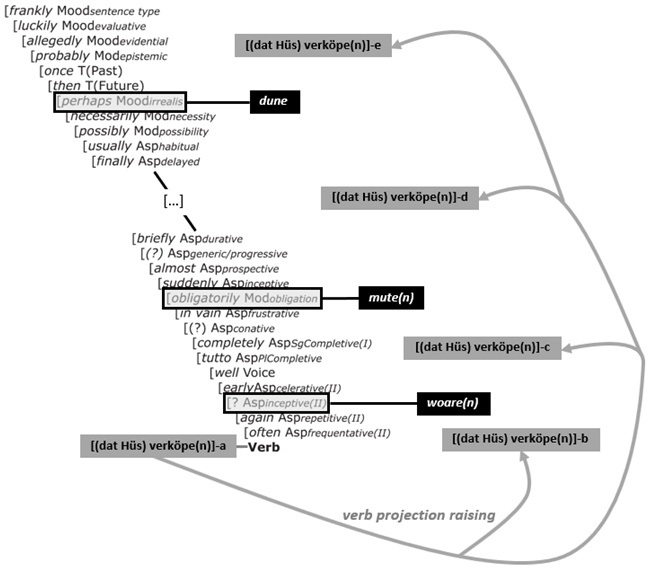

| (2) Structural representation of the NR variant in (1a). |

|

The tree demonstrates our conviction that the VP domain and the IP domain of MLG are head-final. The question of whether the modal verb is base-generated in ModPobligation by external merge or has moved there by feature-driven internal merge from a base-generated position in a V1P is irrelevant to our discussion.6 The inchoative phrase with the adverb nü7 in its specifier position is a rather low functional phrase, even lower than ModPobligation (cf. the scheme in (7)), so the ObjDP dat Hüs (“the house”) in (1a) is either realized in its base position (as the sister of verköpe “sell”, as illustrated) or it has been scrambled string-vacuously to a very low topic phrase by internal merge (not present in (2); cf. Belletti, 2004, p. 17 for IP internal focus and topic positions). When the ObjDP dat Hüs is scrambled to a higher topic position (visualized in brackets in (2)), it is serialized to the left of the adverb,8 and this sequence is actually more frequent (cf. Table 1).

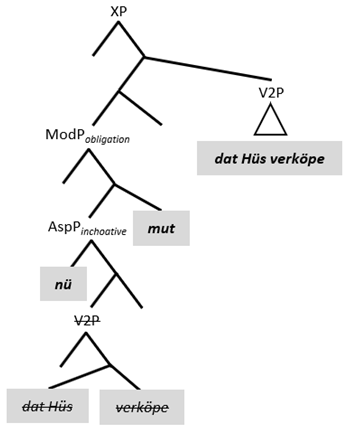

The cluster variants in (1b+c) take (2) as their base. For (1b), we assume v-p-r of the V2P dat Hüs verköpe (“sell the house”). This rightward movement leads to the partially right-branching sequence V1-ObjDP-V2. The tree in (3) demonstrates this variant, which we will call the VPR variant (verb projection raising variant). This is its traditional name, as, just as we do, many researchers have taken (and some still take) it for granted that the entire V2P is raised (cf., e.g., Vanden Wyngaerd, 1989, p. 436; Broekhuis & den Besten, 1989; Penner, 1990; Wurmbrand, 2001, pp. 120–121).

| (3) Structural representation of the VPR variant in (1b). |

|

As before, phonetically realized copies are shown in bold. Unrealized copies are crossed out. In order to obtain the correct superficial sequence, V2P has to be adjoined to a phrase higher up than mut in ModPobligation. We have labeled this phrase XP. Admittedly, by considering adjunction as a derivational option, we create multiple X’ levels, which may be considered problematic in the current generative framework (cf., e.g., Rizzi, 2013, p. 198). However, as v-p-r seems to be, at least partly, a parsing-driven mechanism (cf., e.g., Bach et al., 1987; Haider, 2010, pp. 338–339) which does not affect the semantics of the clause (cf. Wurmbrand, 2017, p. 27), we do not assume it to take place in the narrow syntax but shortly before or after spell-out and, in that sphere, derivational rules may work differently.

Importantly, the preverbal position of the adverb nü makes it clear that (1b) is not a verb-second clause, i.e., the finite verb is in the IP domain; it has not moved to the CP domain as in an unintroduced root clause. Many other translations, however, superficially serialize the finite auxiliary in the second position, i.e., after the introductory element and the SubjDP (cf., e.g., (6) and (8b)). Although we are sure that this position is only superficially and not structurally verb-second, we will see in Section 4.4 that these apparent verb-second clauses may serve as an indicator of a low degree of clausal integration.

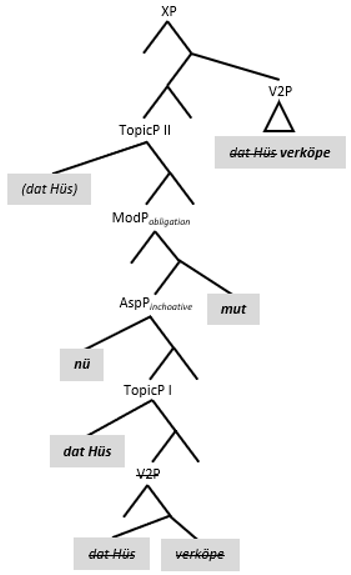

The cluster sequence ObjDP-V1-V2 in (1c) is traditionally called the VR variant (verb raising variant). This label stems from the conviction that on the surface—and in our opinion, only on the surface—the main verb verköpe (“sell”) seems to have moved to the right of mut on its own. However, just like Broekhuis and den Besten, (1989) and Penner, (1990)9, we assume that (1c) is a case of remnant movement, i.e., as in (1b), the entire V2P raises, but unlike in (1b), the ObjDP dat Hüs (“the house”) has been scrambled out of V2P before v-p-r. Wurmbrand’s (2017, p. 78) analysis with respect to the definiteness and the type of internal complement in clauses with the V(P)R variants supports this view:

[…] the final two categories that have to be distinguished in VPR constructions are, on the one hand, indefinite (weak) noun phrases and prepositional phrase [sic], and definite (strong) noun phrases on the other hand. While the phrases of the former type are allowed to occur within a verb cluster in Swiss German, West Flemish, and (at least for some speakers) in Afrikaans and German, the latter are only allowed to separate the verbs of a cluster in Swiss German and West Flemish.

Faced with this distribution, one can conclude that “definite (strong) noun phrases” are scrambled more often than “indefinite (weak) noun phrases” since they can appear within a verb cluster in fewer Continental West Germanic varieties. A similar relationship between the indefiniteness of a phrase and its reluctance to move is found in Broekhuis (2007, p. 121), who states for Dutch that “non-specific, indefinite noun phrases never shift, which is due to the fact that they are necessarily part of the focus of the clause”. In more technical terms, Biskup (2007, p. 122) writes: “In Biskup (2006a, 2006b) I argue that scrambling gives rise to specificity, which can be partitive, epistemic or generic, and that scrambling is driven by a Specificity-feature”. If there are indeed features involved, then scrambling must be considered part of the narrow syntax, a view shared by Roberts (2010, p. 48) with regard to object shift: “If we follow Chomsky (2001, p. 15) in assuming that ‘surface semantic effects are restricted to narrow syntax’, and take the specificity effect associated with clitic movement and object shift to be such a surface semantic effect, then this movement must take place in the narrow syntax”.

In Section 4.4, we will demonstrate that both ObjPPs and the (in)definiteness of the ObjDP/PP have an influence on the raised variants in MLG (cf. also Kaufmann, 2016, pp. 97–100, 202–209 for additional signs of scrambling such as cluster-internal floating quantifiers and cluster-internal stranded prepositions). Having said this, the tree in (4) illustrates the VR variant in (1c), in which the ObjDP dat Hüs has been scrambled out of V2P and is realized in a low topical phrase (TopicP I). This low position causes its serialization to the right of nü (“now”). Again, the more frequent serialization is dat Hüs nü. To account for this sequence, we have to assume a phrase such as TopicP II (with the ObjDP in brackets) to be located above the inchoative phrase with nü.

| (4) Structural representation of the VR variant in (1c). |

|

In our view, the best way to describe the different cluster variants in MLG is to assume that they are but a superficial epiphenomenon of two unrelated syntactic mechanisms, namely v-p-r and scrambling. Assuming that these phenomena are independent of each other may help explain the speaker’s ability to use them for functional purposes. For example, by applying v-p-r but avoiding scrambling, a speaker can create a subordinate clause that closely resembles a root clause (cf. Section 4.4). In this way, the concentration of the V(P)R variants and, in particular, of the VPR variant in strongly disintegrated subordinate clauses may help answer a question posed by Wurmbrand (2017, p. 93): “But what still appears to be an open question is the question of why the elements of a verb cluster are inverted in certain languages and constructions”.

3.2. Structural Factors in the Variation of Two-Verb Clusters

We will now introduce the structural factors that we believe account for much of the variation in clause-final two-verb clusters. These factors are (i) the auxiliary verb, (ii) the structural link between the auxiliary verb and the main verb, and (iii) the type of subordinate clause in which the cluster occurs.

3.2.1. Auxiliary Verbs and Adverbs in the Cartographic Approach

Many researchers have pointed out that the auxiliary verb is fundamental in explaining the different serialization patterns in verb clusters (cf., e.g., Zwart, 1996, p. 233; Lötscher, 1978, p. 10; Barbiers, 2005, pp. 248–255). The innovative aspect of our approach is that we relate this variation to Rizzi and Cinque’s (2016) functional hierarchy in the split IP domain (cf. also Cinque, 1999, 2004; Shlonsky, 2010). Cinque’s (1999) seminal work analyzed the serialization patterns of different types of adverbs in Italian and other languages and claimed that each adverb is located in the specifier position of a functional phrase and that these phrases are localized in a hierarchical order in the IP domain. Rizzi (2004, p. 4) describes this domain (and the split CP domain) as follows:

If overt morphological richness is a superficial trait of variation and a fundamental assumption of uniformity is followed […] then it is reasonable to expect that clauses should be formed by a constant system of functional heads in all languages, each projecting a subtree occurring in a fixed syntactic hierarchy, irrespective of the actual morphological manifestation of the head (as an affix, as an autonomous function word, or as nothing at all).

While adverbs are supposed to occupy the specifier position of the respective phrase, function words (e.g., auxiliary verbs) occupy their head position. Let us now see if we can find supporting evidence for both these claims in the MLG dataset. With respect to adverbs, we can analyze two preposed conditional clauses. While stimulus sentence <15> with an inchoative nü (“now”) has already been introduced in (1a-c), stimulus sentence <17> features the evidential adverb wirklich (“really”). Two serialization patterns can be seen in (5a+b):

| stimulus <17> | Portuguese: Se ele realmente matou o homem, ninguém pode ajudar ele. | |||||||

| English: If he really killed the man, nobody can help him. | ||||||||

| (5) | a. | wann | hei | wirklich | den | Mensch | todgemaakt | haft |

| if | he | really-ADV | [the | man]-ObjDP | killed-V2 | has-V1 | ||

| dann | [0.7] | kaun | keiner | ihm | helpe | |||

| [0.7] | can | nobody | him | help | ||||

| (Bra-22; m/37/MLG+Port) | ||||||||

| b. | wann | hei | den | Mensch | wirklich | umgebracht | haft | |

| if | he | [the | man]-ObjDP | really-ADV | killed-V2 | has-V1 | ||

| kaun | ihm | keiner | helpe | |||||

| can | him | nobody | help | |||||

| (Bra-20; f/50/MLG) | ||||||||

Unlike with the different positions of nü in (1a–c), there may be a scopal difference between the different positions of wirklich. However, the differences between the evidential adverb in (5a) (Zifonun et al., 1997, p. 1126 call wirklich in StG an assertive sentence adverb) and the adverb in (5b), which could be read as a manner adverb, seem to be rather marginal, at least for sentence <17>.10 In any case, (6) shows that there can be little doubt about the informants’ preferred interpretation. This translation represents a total of five tokens.

| stimulus <17> | Spanish: Si realmente mató al hombre, nadie lo puede ayudar. | ||||||||||

| English: If he really killed the man, nobody can help him. | |||||||||||

| (6) | wann | dat | wirklich | is | dat | hei | haf | den | Mensch | ||

| if | it | really-ADV | is | that | he | has-V1 | [the | man]-ObjDP | |||

| todgemeak | nad- | keiner | kaun | ihn | helpen | ||||||

| killed-V2 | nobody | can | him | help | |||||||

| ‘If it is true that he killed the man, nobody can help him.’ | |||||||||||

| (Mex-67; m/16/MLG) | |||||||||||

The translation begins with wann dat wirklich is (“if it is true”), which marks the evidential status of the entire sentence compound. This conditional clause is followed by a second subordinate clause containing the proposition of the protasis of the stimulus sentence. It is beyond doubt that wirklich in (6) has scope over this proposition and must be read as an evidential adverb.

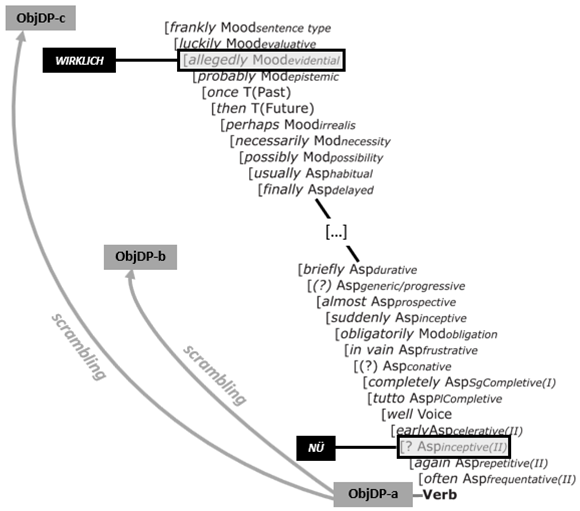

Let us now in (7) (next page) visualize the positional difference between nü and wirklich using the scheme in Shlonsky (2010, pp. 422–423). This scheme demonstrates the position of core functional phrases, illustrating them with prototypical adverbs. The scheme contains mostly mood, mod(al), t(ense), and asp(ect) phrases.11

| (7) Illustration of two adverbs and two instances of scrambled ObjDPs in the split IP domain (based on Shlonsky’s (2010, pp. 422–423) reduced scheme). |

|

The difference in height between Moodevidential and Aspinceptive(II),12 which we can assume to be close to an unrepresented phrase for inchoative aspect, is huge. Importantly, (7) only shows the upper and lower parts of Shlonsky’s scheme (cf. the sign […]), i.e., the distance between the two phrases is even bigger than it appears. In any case, visible scrambling of an ObjDP such as dat Hüs (“the house”) in sentence <15> can be easily detected in the case of low nü (“now”) (cf. ObjDP-b), while the ObjDP den Mensch (“the man”) in sentence <17> needs to scramble to a very high position in order to appear in front of wirklich (“really”) (cf. ObjDP-c). Table 1 now compares conditional clauses with a modal verb and nü (or vondaag “today”) in sentence <15> with conditional clauses with the temporal auxiliary han (“have”) and wirklich (or ap iernst “in seriousness”) in sentence <17>. Only tokens with the NR variant are considered.

Table 1.

Distribution of the sequences adverb–ObjDP and ObjDP–adverb in the conditional clauses of sentences <15> and <17> (only tokens with the NR variant).

Table 1.

Distribution of the sequences adverb–ObjDP and ObjDP–adverb in the conditional clauses of sentences <15> and <17> (only tokens with the NR variant).

| sentence <15> nü (vondaag) | sentence <17> wirklich (ap iernst) | |

| n (tokens) | 104 | 138 |

| adverb-ObjDP | 14 | 123 |

| 13.5% | 89.1% | |

| χ2(1, n = 242) = 138.2; p < 0.001 ***/Phi: 0.76/0 cells with less than 5 expected tokens | ||

| ObjDP-adverb | 90 | 15 |

| 86.5% | 10.9% | |

The unmarked sequence for sentence <15> is ObjDP–adverb, strongly suggesting that the inchoative adverb nü (“now”) occupies a low position.13 Unlike this—and this difference is highly significant14—the unmarked sequence in sentence <17> is adverb–ObjDP, as in (5a), strongly suggesting that the evidential adverb wirklich (“really”) occupies a high position.

With regard to the position of the auxiliary verb, sentence <15> offers another illuminative type of variation. Five informants did not translate this sentence with the intended modal verb expressing deontic obligation (208 times mute(n) “must”; 39 times solle(n) “should”15) but with dune (“do”), as in (8a). Here, dune, a multifunctional auxiliary in MLG (cf. Postma, 2019, p. 149 for the comparable multifunctionality of the Pomerano cognate daua), could be said to be a conditional marker, or—in a somewhat loose sense (sentence <15> is not counterfactual)—an irrealis marker.16 Even more informants, 18 to be precise, translated the clause with woare(n) (“will”), as in (8b), an optional future tense marker, whose inchoative nature fits the presence of the inchoative adverb nü (“now”, cf. Leiss, 1992, pp. 214–215 for the fact that the characterization as inchoative fits the StG cognate werden both as a main and an auxiliary verb).17

| stimulus <15> | Spanish: Si tiene que vender la casa ahora, se va a poner muy triste. | |||||||||

| English: If he has to sell the house now, he will be very sorry. | ||||||||||

| (8) | a. | wann | hei | dat | Hüs | vondaag | verköpen | dät | ||

| if | he | [the | house]-ObjDP | today-ADV | sell-V2 | does-V1 | ||||

| dann | is | dei | trürig | |||||||

| be | he | Ø | sad | |||||||

| (Mex-107; m/38/MLG) | ||||||||||

| b. | wann | hei | wird | dat | Hüs | nü | fuats | verköpe | ||

| if | he | will-V1 | [the | house]-ObjDP | now-ADV | sell-V2 | ||||

| dat | wird | ihm | sehr | leid | were | |||||

| this | will | him | very | sorry | become | |||||

| (Fern-35; f/57/MLG+StG) | ||||||||||

Thanks to this variation, we can verify the existence of a potential relationship between the structural height of different auxiliary verbs and the share of the V(P)R variants in the same stimulus sentence, meaning that we do not have to worry too much about further interfering factors. Once again, we will use Shlonsky’s (2010, pp. 422–423) reduced scheme. This time, we have added the three auxiliary verbs found in sentence <15> and four possible adjunction sites of V2P after v-p-r.

| (9) Illustration of three auxiliary verbs and four instances of the raised V2P in the split IP domain (based on Shlonsky’s (2010, pp. 422–423) reduced scheme). |

|

The phrase Moodirrealis (dune) is very high, much higher than Aspinceptive(II), a phrase we have assumed to be close to the unrepresented phrase Aspinchoative headed by woare(n) (“will”; cf. Note 12). The third relevant phrase Modobligation (mute(n)) occupies an intermediate position.18 With regard to the different positions of a raised V2P, (9) shows that in verb clusters with woare(n), the right-branching V(P)R variants can be derived by [(dat Hüs) verköpe(n)]-c/d/e. As for mute(n), visible v-p-r only occurs in cases d/e, while for dune, it only occurs in case e. With regard to case b, v-p-r will apply string-vacuously for all auxiliaries. The fact that we assume that it is possible for v-p-r to end up in so many different positions is not as problematic as it might seem. Remember that we consider v-p-r to be a case of adjunction, a type of movement that enjoys much more freedom than adverbs and auxiliary verbs in the spine of the split IP domain. Precisely to show that the sequence of adverbs cannot be a consequence of adjunction, Shlonsky (2010, p. 421) writes: “Adjunctions to maximal projections typically do not show such rigid ordering constraints […]”. In any case, judging from (9), we would expect that clusters with dune should lead to very few instances of the V(P)R variants, while clusters with woare(n) should induce very many such instances. Table 2 shows the respective shares for the visibly right-branching V(P)R variants and the NR variant. This latter variant will inevitably contain a certain number of tokens in which v-p-r has occurred string-vacuously (cf., e.g., case b in (9)).

Table 2.

Distribution of the NR variant and the V(P)R variants in sentence <15> depending on different auxiliary verbs.

There is only one token of the NR variant with the auxiliary woare(n) (5.6%), but four of the five tokens with dune feature the NR variant (80%). As expected, translations with mute(n), which expresses deontic obligation and is located between the phrases headed by dune and woare(n), show an intermediate share of 45.7%. Given the highly significant distribution in Table 2, our first hypothesis regarding the effect of auxiliary verbs on the serialization patterns in two-verb clusters can be formulated as follows:

(10) Hypothesis I:

The higher up in the split IP domain an auxiliary verb is located, the fewer cases of v-p-r will be visible. Thus, a high structural position should correlate with a low share of the raised V(P)R variants.

Importantly, although the tokens in Table 2 come from the same stimulus sentence, this analysis is merely monofactorial, i.e., it does not consider other possible influences (cf. Section 4 for this) such as informant-related factors like age, gender, the language competences, and in particular, the possible impact of the structural link between the auxiliary verb and the main verb, the topic of the next section.

3.2.2. The Structural Link between the Auxiliary Verb and the Main Verb

We assume that the fundamental possibility of v-p-r strongly depends on the structural link between the auxiliary verb and the main verb. Thus, the second hypothesis is as follows:

(11) Hypothesis II:

If the structural link between the auxiliary verb and the main verb is strong, as in the case of the auxiliary dune (“do”), v-p-r is inhibited more frequently than in a verb cluster with a weaker link as, for example, in the case of modal verbs.

One way to evaluate the strength of this link is to see if the two verbs are mutually dependent in order to ensure a correct interpretation. Modal verbs, for example, do not influence the meaning of the main verb they govern, while this is quite different in the case of the temporal auxiliary in the present perfect tense. With respect to this tense in StG, Grewendorf (1995, p. 83) and Musan (2002, p. 40) are convinced that the temporal auxiliary in the present tense and the past participle of the main verb must co-act in order to transmit the notion of anteriority.

The importance of this link can also be seen by comparing sentence <3> Don’t you see that I am turning on the light, in which many informants inserted the progressive auxiliary dune, with sentence <5> Henry doesn’t know that he can leave the country, in which most translations include the dynamic modal verb könne(n) (“can”). Shlonsky’s scheme in (7) and (9) locates the phrase Modpossibility much higher than the phrase Aspgeneric/progressive (note once again the missing phrases indicated by […]). Therefore, if only the location of the auxiliary verb in the split IP domain was decisive, we would expect more instances of the V(P)R variants with low dune than with high könne(n). This, however, is not the case. In the complement clauses with könne(n), we find 53.4% of instances of the V(P)R variants (95 of 178 relevant tokens), while in the complement clauses with dune, only 29.8% of the translations feature the V(P)R variants (28 of 94 relevant tokens). Therefore, contrary to the first hypothesis in (10), dune does not co-occur with more instances of the V(P)R variants, even though it is localized much lower than könne(n) in the split IP domain.

One reason for this unexpected result may be the fact that dune is an all-purpose auxiliary.19 This multifunctionality is probably a consequence of the fact that even the semantics of dune as a main verb is rather unspecific. Dune, therefore, lends itself to all kinds of grammaticalization processes, for example, the shift to an aspectual or irrealis auxiliary or even as a semantically even emptier verbal host for the integration of loan verbs (cf., e.g., Kaufmann, 2023, pp. 353–355). However, such an all-purpose auxiliary comes with a serious disadvantage, namely the fact that the hearer has to parse the whole clause in order to specify its meaning. In particular, its interpretation depends on certain adverbs such as the habitual always, as in the stimulus sentence <34> This is the man who is always staring at my house (cf. (19)) or, when coding the progressive aspect, on the meaning of the main verb, as with the achievement verb to turn on in the just analyzed stimulus sentence <3> Don’t you see that I am turning on the light. This dependency is the reason why we assume that the structural link between dune and the main verb is very strong and why the NR variant with the sequence main verb–dune is very frequent. If finite dune appeared earlier in the clause—and this would be the case in the V(P)R variants—the hearer may have trouble identifying its meaning.

Admittedly, our reasoning so far does not provide a feasible way to accurately measure the strength of the link between the auxiliary and the main verb, and unfortunately, we will not be able to offer a definitive conclusion in this respect. However, another aspect of verb clusters may at least partly address this conundrum, namely the different morphological forms of the main verb as either a past participle (in the case of the temporal auxiliary han “have”) or a bare infinitive (in all other cases of the MLG dataset). One could assume, as Barbiers (2005, p. 262—Note 18) and von Stechow (1990, pp. 149–150) do, that at least modal verbs selecting a bare infinitive and temporal auxiliaries selecting a past participle are constructed identically and coherently, which means that they all embed a bare V2P. However, opinions differ with regard to different morphological expressions. For example, Ramchand and Svenonius (2014, p. 158) write: “The novelty here comes from actually attempting to line up auxiliary ordering with these zones in an explicit way, placing the progressive participle within the VP domain and the perfect participle outside of it”. Moreover, even the same morphological expression does not guarantee structural identity (cf., e.g., Wurmbrand, 2001). A bare infinitive governed by aspectual dune (“do”) may be of a very different nature than a bare infinitive governed by modal verbs. Ramchand and Svenonius (2014, p. 159) confirm this assumption: “Both the modal and the perfect auxiliary introduce topic situations which are anchored to the utterance time, and which are distinguishable in principle from the VP event […]”, while “[i]n the progressive […], the event run time and the tense specification of the progressive auxiliary cannot be so distinguished”. The fact that they group together the modal verbs and the perfect auxiliary and contrast this class with an aspectual marker for which the event time and the tense specification cannot be distinguished may explain the role of dune as the most v-p-r-hostile auxiliary (cf. Table 4). After all, this unique “semantic” congruence can be seen as an indication of a very strong link between this auxiliary and the main verb.

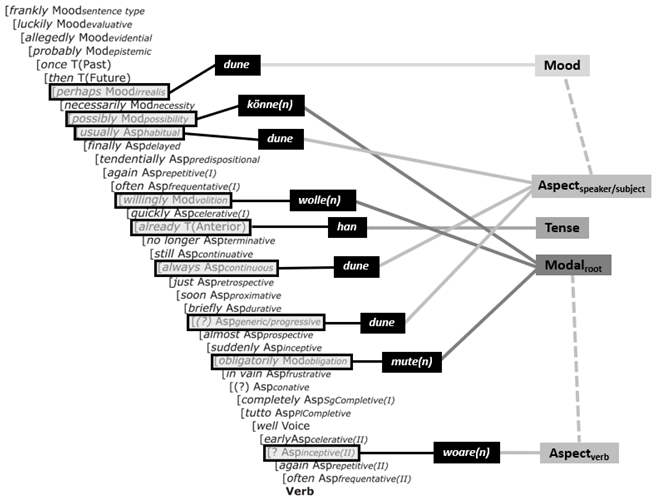

In conclusion, if we assume that there exist different types of links between the auxiliary and the main verbs, we must distinguish different classes of auxiliary verbs. Only after such a distinction has been made should we focus on the relative position of individual members of these classes in the split IP domain. To illustrate this, we propose a potential classification of the nine auxiliary verbs in the MLG dataset in Shlonsky’s now complete scheme in (12).

| (12) Five possible classes of auxiliary verbs in the IP domain (based on Shlonsky’s (2010, pp. 422–423) complete scheme). |

|

Let us start out by discussing some general facts about the split IP domain. One way to understand this domain is to think of its higher functional phrases as more speaker-related or more related to the subject of the clause and its lower phrases as more verb-related or simply as less speaker-/subject-related (cf. also Wiltschko’s (2014) organization of universal categories in a universal spine). In (12), the sphere of mood is highest, followed by the sphere of epistemic modals, for which we unfortunately have no relevant data. Both of these spheres are strongly speaker-related. The next sphere is the tense sphere, which contains T(Past) and T(Future). From there, the scheme roughly mirrors the TMA approach (tense–mood–aspect). All root modals are below the tense phrases, with the exception of T(Anterior), and the majority although not all of the aspect phrases are lower than the modal phrases.

What makes the aspectual sphere somewhat problematic, at least on first sight, is the huge range from the very high habitual aspect to the very low frequentative aspect. However, this spread becomes comprehensible once we realize that the higher aspect phrases are more speaker-oriented, while the lower aspect phrases are more verb-oriented (bordering on the category Verb with the truly verbal sphere of Aktionsart or inner aspect; cf., e.g., MacDonald, 2008). For example, with respect to the continuous/progressive aspect, which is closer to the speaker’s end of the IP domain than the inchoative aspect, here represented by Aspinceptive(ii), it is the speaker who decides whether s/he wants to adopt an internal or an external point of view with regard to the state/event described. In contrast, the inchoative meaning of woare(n) (“will”) does not depend at all on the speaker’s point of view. Finding habitual aspect highest in (12) should not surprise us either, since in this case, the speaker is simply emphasizing the habitual occurrence of an event, abstracting from any single event and not immersing herself/himself in the described event, as is the case with the progressive aspect.

As for the modal verbs, the modal possibility often describes a characteristic/capability of the subject of the clause, which may or may not be identical with the speaker. Therefore, it makes sense to situate this phrase in the higher speaker-/subject-related sphere (cf., e.g., stimulus sentence <16>, as in (22a–c)). In contrast, the cause of or source for an obligation is something/someone that is almost always outside the speaker’s/subject’s influence (cf. stimulus sentence <15>, as in (1a–c)). The existence of such an external source justifies a position far away from the upper regions of the IP domain. The intermediate position of wolle(n) (“want to”) can be explained by the fact that it is more subject-oriented than mute(n) (“must”) but also less subject-oriented than könne(n) (“can”). After all, the subject’s mental and physical capabilities are generally more subject-defining than his or her often short-lived desires.

Regarding the temporal auxiliary han (“have”), it is important to note that we did not locate it in the high tense phrase T(Past). There are two reasons for this; first, we must not forget that han occurs with present tense morphology in the present perfect tense, a fact that strongly contradicts its localization in T(Past). Second, as in StG, there still seems to be a certain aspectual touch to the present perfect tense in MLG, which distinguishes it from the past tense and makes its positioning in T(Anteriority) more appropriate. In any case, T(Anteriority) appears in the predominantly aspectual sphere of (12). Regarding its structural link, we have already mentioned in Section 3.2.2 that han can only code anteriority in combination with the past participle of the main verb. However, although the results of Table 4 suggest that this link is strong, it does not seem to be as strong as the link of aspectual dune, as the V(P)R variants are much less frequent with dune than with han.

With regard to the classes of auxiliary verbs in (12), we still have to see whether it makes sense to separate irrealis dune (Mood) from aspectual dune or to separate woare(n) (“will”; Aspectverb) from the modal verbs (cf. the dashed lines in (12) and Section 4.3 for a discussion). At this point, we only claim that both han and dune are more strongly linked to their respective main verbs than modal verbs. Within each of these classes, however, we expect differences in the shares of visible v-p-r according to the position of the individual members in the split IP domain. Since Kaufmann (2023, pp. 377–385) has already shown that the different positions of aspectual phrases do indeed account for part of the variation in the MLG two-verb clusters headed by dune (“do”), this seems to be a viable approach.

3.2.3. Clause Type

The third structural factor concerns the degree of integration of the subordinate clause into the matrix clause. Apart from Kaufmann (2003, 2007, 2016), serious consideration has never been given to the potential influence of this factor on verb clusters. Though De Sutter (2009, p. 234) mentions possible effects of “clause type (root vs. embedded clause), the nature of the conjunction (in case of an embedded clause) and verb tense”, he neither offers a real discussion of these factors nor does he point to any pertinent publication. In any case, v-p-r to a high position in the higher IP domain or the CP domain will almost always cause a right-branching sequence (the V(P)R variants). However, in strongly integrated subordinate clauses, such high positions may simply not be available. Hopp and Putnam (2015, p. 207), who relate clause type to the verbal position in subordinate clauses, write: “In our approach, the subordinate clauses in MSG [Moundridge Schweitzer German] that continue to exhibit verb-final ordering lack illocutionary force (e.g., [-Force]), and as a result do not license an extended CP-layer […]”. Although we see the causality the other way around, with the lack of an extended CP-layer (and/or IP-layer) inhibiting the VPR variants, Hopp and Putnam (2015, pp. 195–196) also induce v-p-r as a possible factor for verb-second clauses. In this respect, it is important to realize that it is especially subordinate clauses with the VPR variant that share some crucial features with unintroduced root clauses: (i) their verbs appear discontinuously in a V1-V2-sequence and (ii) their finite verb often appears, at least superficially, in second position (cf. (6) and (8b)). Strikingly, this second similarity resembles the variation in Danish subordinate clauses with adverbs (cf., e.g., Christensen & Jensen, 2022; Christensen et al., 2020), which appear either with the sequence adverb–verb or with the sequence verb–adverb, the latter resembling the sequence in Danish root clauses, which are, just like in StG, verb-second clauses. Thus, the third hypothesis can be formulated as follows:

(13) Hypothesis III:

More integrated subordinate clauses provide less structural space for adjunction in the IP and the CP domain. Therefore, we expect to see fewer instances of the raised V(P)R variants in more integrated clauses.

Crucially, because of the possible functional side of the different cluster variants, we have to formulate a fourth hypothesis:

(14) Hypothesis IV:

Since the V(P)R variants share some linearization features with unintroduced root clauses (e.g., V1 precedes V2), some Mennonites may have begun to refrain from scrambling the ObjDP out of V2P in order to further strengthen this similarity by producing the VPR variant with the superficial sequence V1-ObjDP-V2. With this, they may have started to indicate structural integration by their choice of particular cluster variants.

With the MLG dataset, we can analyze three types of subordinate clauses, namely complement, conditional, and relative clauses. Causal clauses cannot be included, since many informants, especially in the USA and Mexico, have reanalyzed them as structural verb-second clauses20 (cf. Kaufmann, 2016, pp. 286–306 and Christensen & Jensen, 2022, p. 201 for a comparable development in Danish). All complement clauses analyzed represent the extraposed internal complement of the respective matrix construction (a verb or a predicative), i.e., they follow their matrix clause. All conditional clauses precede their matrix clause. The relative clauses appear adjacent to their reference noun, and all of them can be qualified as restrictive rather than appositive (cf., however, Kaufmann, 2016, pp. 30–31 for some problems in deciding this issue).

The question now is which characteristics can be used to distinguish between different degrees of clausal integration. Here, it is important to note that a scalar concept of clausal integration is not new. Fabricius-Hansen (1992, p. 465; cf. also Frey, 2011, p. 72; Reis, 1997; Auer, 1998; Langacker, 2009, p. 328), for example, writes that “[…] it need not be the case that a clause is either subordinate or not subordinate to another clause. Rather, there may be a stronger or weaker, or a more or less pronounced, relationship of subordination between them [translation G.K.]”. One characteristic that defines the relationship of subordination can be broadly called “semantic”. For this, a comment by Reis (1997, p. 126) is crucial:

Subordinate clauses occupy specific phrasal positions in the projection of the head Vb [matrix verb] of Sb [matrix clause] and have specific relations with it (adverbial clauses with the event variable of the head, complement clauses with its theta grid). Thus they are ‘directly licensed’ from Vb (Haider, 1995, p. 262). The base position of the complement clauses results from the assignment conditions of the theta roles: They must be l-marked by Vb or strictly governed by it. Attributive clauses of Sb (relative clauses, comparative clauses, etc.) are characterized by an antecedent in Sb to which they relate in a specific way (restrictive, explicative, etc.). With regard to Vb, Haider calls them ‘indirectly licensed’ […] [translation G.K.].

“Semantically”, the three types of subordinate clauses analyzed in the present paper can be ranked. Complement and conditional clauses are directly licensed by the matrix verb, whereas relative clauses are only indirectly licensed and thus may be considered to be less integrated. Complement clauses are distinguished from adverbial clauses by the fact that, in their base position, they are l-marked or strictly governed by the matrix verb and not only by its event variable. In terms of their “semantic” integration, complement clauses are more integrated than adverbial clauses (cf. also Christensen & Jensen, 2022, p. 196 for the same claim). The “semantic” ranking is as follows (< means less integrated):

| (15) relative clauses < conditional clauses < complement clauses |

Two other characteristics of subordinate clauses are their vertical position in the tree structure and their horizontal position in clausal topology. The higher up in the structural tree the subordinate clause is, the further away from the (verbal core of the) matrix clause it is. Haider’s (2010, p. 225) comment with regard to extraposed relative and complement clauses illustrates this (cf. also Frey’s 2011, p. 71 and Haegeman’s 2012, p. 170 analogous comments with regard to adverbial clauses): “As emphasized above […], extraposed relative clauses precede extraposed argument clauses […]. Therefore it is impossible that extraposed argument clauses are adjoined lower than extraposed relative clauses”. If extraposed complement/argument clauses are adjoined in such a high and disintegrated position, we may assume that they possess more structural space in the higher IP domain and the CP domain, which may then allow for more instances of visible v-p-r. Regarding structure, we can then formulate the following sequence (< again means less integrated):

| (16) extraposed complement clauses < extraposed relative clauses |

With regard to the topological position of the subordinate clause, the subordinate clause must, according to Fabricius-Hansen (1992, p. 467), either occupy the topological prefield, as is the case with the conditional clauses in the MLG dataset, or the topological midfield, or it must be an attributive clause adjacent to its nominal head (the relative clauses in the MLG dataset). Extraposed clauses in the postfield, such as the complement clauses in the MLG dataset, do not belong to Fabricius-Hansen’s category of indisputably subordinate clauses. The potential impact of the topological field in which the subordinate clause occurs is not at all surprising, since several syntactic phenomena demonstrate that the prefield of a German clause is structurally more integrated than its postfield.21 On the one hand, in a declarative clause, the prefield must (almost) always be phonetically realized, regardless of whether this condition is met by an expletive (e.g., es “it” in StG), an adverb, a DP, a PP, or a CP. Conversely, the postfield frequently remains empty. On the other hand, the prefield is usually identified with a strongly integrated specifier position in the CP domain, while the postfield is usually analyzed as a loosely adjoined position (cf., e.g., Sternefeld, 2008, pp. 289–290). With respect to the MLG dataset, we can thus establish the following hierarchy with respect to the topological integration of the subordinate clauses:

| (17) complement clauses in the postfield < conditional clauses in the prefield |

It is difficult to decide how relative clauses should be treated in this respect. They may sometimes be said to be part of the prefield as in (18), but it is often hard to determine whether they are either part of the midfield or, if they have been extraposed string-vacuously, part of the postfield as in (19).

| stimulus <36> | English: The doctor who wants to see my foot is very worried. | |||||||||

| (18) | de:- | de | Doktor | wat | will | min | Fut | sehen | ||

| the | doctor | who | wants-V1 | [my | foot]-ObjDP | see-V2 | ||||

| is | sehr | bekümmert | ||||||||

| is | very | worried | ||||||||

| (USA-6; m/20/Engl>MLG-79%) | ||||||||||

| stimulus <34> | Spanish: Este es el hombre que está siempre mirando mi casa. | |||||||||

| English: This is the man who is always staring at my house. | ||||||||||

| (19) | det | is | de | Maun | wat | immer | no | min | Hüs | |

| this | is | the | man | who | always-ADV | [to | my | house]-ObjPP | ||

| kieken | dät | |||||||||

| look-V2 | does-V1 | |||||||||

| (Mex-81; m/46/Span>MLG-71%) | ||||||||||

One important feature that distinguishes relative clauses from both complement and conditional clauses is the fact that they do not form a constituent themselves but are part of a constituent (cf., e.g., Hilpert, 2013, p. 204 for this). With this in mind, a further hierarchy can be established as follows:

| (20) complement clauses/conditional clauses < relative clauses |

In three of the four hierarchies in (15), (16), (17), and (20), extraposed complement clauses represent the least integrated clause type. Both relative and conditional clauses obtain this position only once (cf. (15) and (20), respectively). Thus, extraposed complement clauses do indeed seem to be the most disintegrated clause type in the MLG dataset. If the third hypothesis in (13) is correct, we expect more tokens of the V(P)R variants (especially the VPR variant) in this clause type. As for the ranking of conditional and relative clauses, we are faced with a tie. We could assign different weights to the four rankings in order to distinguish the two clause types, but this would only be an ad hoc decision. Therefore, we would prefer to trust the statistical analyses outlined in the next section.

4. Large-Scale Statistical Analyses

4.1. The Dataset

The monofactorial analyses in Section 3.2 have provided preliminary support for the claim that the auxiliary verb affects the frequency of v-p-r (cf. Table 2 in Section 3.2.1 and the discussion of sentences <3> and <5> in Section 3.2.2). However, we have not yet provided an analysis of the link between the auxiliary and the main verb nor of the clause type. To fill this gap, we will now carry out a generalized linear mixed model in SPSS (version 29.0.1.0 (171); target distribution and relationship with the linear model; binary logistic regression). The use of such a model instead of a binary logistic regression analysis is necessary because we will introduce both random and fixed factors. The model comprises 4470 tokens of subordinate clauses with clause-final two-verb clusters (1854 tokens with the V(P)R variants). The model binarily contrasts the V(P)R variants (+v-p-r) with the reference category, the NR variant (-visible v-p-r). The 321 informants enter the model as a random factor. Strictly speaking, these informants were not randomly selected, as their selection was based on the indispensable condition of sufficient competence in the majority language. Importantly, however, when asked to participate, very few people refused to do so. On average, each informant contributed 13.9 tokens (ranging from 4 to 23 translations; SD: 3.2). Apart from missing or unusable translations, this rather wide range is due to informants who produced the preterite in stimulus sentences that aimed at translations with the present perfect tense and informants who did not produce (m)any translations with optional dune (“do”) or woare(n) (“will”). Both preferences resulted in translations without a verb cluster.

The 4470 tokens come from 29 of the 46 stimulus sentences, with the majority of 2984 tokens (66%) coming from the twelve sentences designed to elicit clause-final two-verb clusters with a temporal auxiliary or a modal verb in complement, conditional, and relative clauses. Since these sentences were carefully designed (cf. Section 2.2), they cannot be considered as a random factor nor can they enter the modal as a fixed factor either, since they are strongly correlated with the crucial factors of auxiliary verb and clause type. On the contrary, the research location enters the model as a fixed factor. Again, the six locations were not randomly selected and therefore should not be considered a random factor. Moreover, the number of six levels is rather small for a random factor. In total, the model contains a binary dependent variable, one random factor, and eight fixed factors. In the following, the fixed factors are listed, with categorical variables being presented with their reference category and the exact number of tokens for each level:

- Categorical variables

- Research location (six variants; reference category Brazil): Brazil (828 tokens); USA (1123 tokens); Mexico (1336 tokens); Bolivia (113 tokens); Menno, Paraguay (569 tokens); Fernheim, Paraguay (501 tokens)

- Gender (two variants; reference category men): men (2481 tokens); women (1989 tokens)

- Clause type (eight variants; reference category ±extraposed relative clause): ±extraposed relative clause (791 tokens); -dislocated relative clause (382 tokens); ±dislocated relative clause with an anaphoric pronoun (221 tokens); conditional clause without dann (735 tokens); conditional clause with dann (946 tokens); disintegrated conditional clause (136 tokens); complement clause without dat (1009 tokens); complement clause with dat (250 tokens)

- Auxiliary verb22 (nine variants; reference category hananterior): hananterior (1527 tokens); woare(n)inchoative (542 tokens); wolle(n)volition (613 tokens); mute(n)obligation (629 tokens); könne(n)possibility (525 tokens); duneconditional (153 tokens); dunehabitual (150 tokens); dunecontinuous (141 tokens); duneprogressive (190 tokens)

- Metric variables

- Age

- Competence in MLG

- Competence in the majority language

- Competence in StG

Before presenting the results of the model, some comments are in order: (i) For 45 of the 321 informants (14%), we do not know the “precise” level of competence in the contact languages (cf. Note 2). However, we do know the dominant language(s) of these informants. In order to not lose their tokens for the model, their language competences were estimated according to the available data of comparable informants, i.e., of informants of the same community and in the same gender and age group. (ii) Six of the 73 informants in the United States and two of the 44 informants in the Paraguayan colony of Menno had lived in the respective research location for less than five years. These informants were pooled with the other members of the respective community. Importantly, excluding these two sets of informants would not change anything substantial with regard to the model’s results. Their inclusion, however, greatly increases its reliability. (iii) We distinguish three types of imperfective aspects (cf. Kaufmann, 2023, pp. 389–393 for a clause-by-clause categorization), namely habitual aspect as in <34> This is the man who is always staring at my house (cf. (19)); continuous aspect as in <4> Can’t you see that I am wearing a new dress?; and progressive aspect as in <32> The stories that he is telling the men are very sad (cf. (23)). Regarding the auxiliary verbs in general, it should not be forgotten that tokens with aspectual/irrealis dune (“do”) are rare in the Paraguayan translations and that the modal verb wolle(n) (“want to”) occurs predominantly in relative clauses (cf. the discussion of sentences <35> and <36> in Section 4.3). These uneven distributions are certainly not ideal for statistical analyses, but most of them cannot be avoided. (iv) So far, we have talked about three clause types, namely complement, conditional, and relative clauses. However, there are some variations in the translations that force us to refine this rather rough division by creating eight instead of three levels for the factor clause type. Regarding complement clauses, many translations include a correlate in the matrix clauses, as in (21b), which unlike (21a) features dat (“it” or “that”).23

| stimulus <5> | Portuguese: O Enrique não sabe que ele pode sair do país. | ||||||||||||

| English: Henry doesn’t know that he can leave the country. | |||||||||||||

| (21) | a. | Heinrich | [1.7] | weit | nich | dat | hei | dat | Land | ||||

| Henry | [1.7] | knows | not | that | he | [the | country]-ObjDP | ||||||

| verlote | kaun | ||||||||||||

| leave-V2 | can-V1 | ||||||||||||

| (Bra-2; m/55/MLG) | |||||||||||||

| b. | Enrique | weit | dat | nich | dat | hei | kaun | ||||||

| Henry | knows | not | that | he | can-V1 | ||||||||

| üt | dem | Land | gone | ||||||||||

| [out | the | country]-ObjPP | go-V2 | ||||||||||

| (Bra-36; f/31/Port>MLG-50%) | |||||||||||||

Due to the fact that the subordinate clause in (21b) is linked to the nominal correlate dat, many linguists see it as a kind of attributive/relative clause rather than a complement clause (cf., e.g., Lehmann, 1984, pp. 325–329; Zimmermann, 2011; Kaufmann, 2016, pp. 362–373 on the formal and semantic similarities of relative and complement clauses). Taking this into account, the question as to whether such a correlate changes the degree of integration of the subordinate clause arises.

A somewhat comparable variation occurs in the translations of conditional sentence compounds, many of which contain the resumptive element dann (“then”; cf. (22b) instead of (22a)). Aside from this, translations such as (22c) contain disintegrated conditional clauses, i.e., clauses that do not occupy the prefield of the matrix clause (SpecCP in structural terms) but rather the pre-prefield (probably a position adjoined to a phrase of the CP domain).

| stimulus <16> | Spanish: Si él puede resolver este problema, es muy inteligente. | |||||||||||||

| English: If he can solve this problem, he is very smart. | ||||||||||||||

| (22) | a. | wann | hei | kaun | dit | Problem | lösen | |||||||

| if | he | can-V1 | [this | problem]-ObjDP | solve-V2 | |||||||||

| is | hei | sehr | klüag | |||||||||||

| is | he | very | smart | |||||||||||

| (Mex-60; f/42/MLG) | ||||||||||||||

| b. | wann | dei | dat: | [0.7] | Problem | kaun | lösen | |||||||

| if | he | [the | [0.7] | problem]-ObjDP | can-V1 | solve-V2 | ||||||||

| dann | is | dei | sehr | klüag | ||||||||||

| is | he | very | smart | |||||||||||

| (Mex-61; m/31/Span>MLG-64%) | ||||||||||||||

| c. | wann | dei | dit | Trouble | kaun | lösen | ||||||||

| if | he | [this | trouble]-ObjDP | can-V1 | solve-V2 | |||||||||

| dei | is | sehr | klüag | |||||||||||

| he | is | very | smart | |||||||||||

| (Mex-41; m/37/MLG) | ||||||||||||||

With respect to relative clauses, there is, in addition to their topological position (cf. (18) and (19)), one more type of variation. Here, (23) is relevant.

| stimulus <32> | Spanish: Las historias que les está contando a los hombres son muy tristes. | |||||||||

| English: The stories that he is telling the men are very sad. | ||||||||||

| (23) | die | Geschichte | wat | dei | de | Mensche | vertahle | dät | ||

| the | stories | that | he | [the | people]-ObjDP | tell-V1 | does-V1 | |||

| die | sin | sehr | trürig | |||||||

| are | very | sad | ||||||||

| (Bol-8; m/20/MLG) | ||||||||||

The translation in (23) features the resumptive anaphoric pronoun die (“they”) that appears after the relative clause. This is a clear case of left dislocation (cf. the discussion in Bousquette et al., 2021), and one may therefore assume that the relative clause and its reference noun are located in the pre-prefield, as was the case with the disintegrated conditional clause in (22c). Bearing this in mind, we have to distinguish three subtypes of relative clauses. Relative clauses as part of the (pre-)prefield, one of which may be dislocated (-dislocated relative clause; ±dislocated relative clause with an anaphoric pronoun), and relative clauses that occur at the end of the sentence compound and may or may not be extraposed into the postfield (±extraposed relative clause).

4.2. Informant-Related Predictors

We are now ready to discuss the results of the model. The predicted distribution of the NR variant and the V(P)R variants versus their actual observed distribution increases from 58.5% to 86.8% when the random effect and the fixed effects are added. The conditional R2 is 0.642, i.e., the random and fixed effects together “explain”24 64.2% of the variation in the dependent variable. The informants (random effect) “explain” 17%.25 With this, the six fixed effects with a significant F-value “explain” 47.2% of the variation (marginal R2 is 0.472). Because of the high number of fixed effects with a significant F-value, we will illustrate the results in two tables, starting with the four informant-related fixed effects in Table 3.

Table 3.

Generalized linear mixed model for visible v-p-r in complement, conditional, and relative clauses (part I: informant-related predictors).

Table 3.

Generalized linear mixed model for visible v-p-r in complement, conditional, and relative clauses (part I: informant-related predictors).

| research location | StG | age | gender |

| F: 28.6 *** | F: 13.9 *** | F: 11.1 *** | F: 6.3 * |

| USA (7.97 ***) Mexico (6.23 ***) Bolivia (3.2 (*)) | women (1.65 *) | ||

| Brazil | men | ||

| Menno (0.31 **) Fernheim (0.27 **) | StG (0.864 ***) | age (0.977 ***) | |

The four fixed effects in Table 3 are ranked by their F-values. The larger this value, the more confident we can be that the predictor in question actually improves the overall fit of the model. The metric variables and the reference categories of the categorical variables are shown in bold. The reference categories are placed in the shaded central line. Variants that do not show a significant difference in effect size to the reference category are located together with them (cf. Table 4 for this). Above the shaded line, the metric variables and the variants of the categorical variables that indicate greater odds for the V(P)R variants (odds ratios greater than 1) than the respective reference category are listed with the precise values of their odds ratio. The odds ratios represent the ratio of the odds of the target variant, in Table 3, the V(P)R variants, occurring in the presence of a certain level of a fixed factor (e.g., being a woman) to the odds of the target variant occurring in the presence of the reference category (in this case, being a man). Below this line, the metric variables and the variants of the categorical variables that indicate smaller odds for the V(P)R variants than the reference category are listed (odds ratios smaller than 1).

The research location is the first predictor that we will discuss. In order to understand the differences between the six communities, it is important to recall their different migration paths, which were described in Section 2.1. On the one hand, there are the more conservative communities in Mexico, Bolivia, and the United States, all of which speak the Chortitza variety of MLG. On the other hand, there are more progressive communities in Brazil and Paraguay, all of which speak the Molotchna variety of MLG. Table 3 shows that the odds of a US-American informant producing the V(P)R variants are 7.97 times greater than those of a Brazilian informant, the reference category for this variable. For a Mexican informant, the odds ratio is 6.23. Although the two communities in Paraguay originate from different migration waves, the influence of Fernheim was so strong that today, they behave rather similarly. Compared to a Brazilian informant, their odds of producing the V(P)R variants are 3.23 (Menno; 1:0.31) and 3.71 times smaller (Fernheim; 1:0.27), respectively. Interestingly, the eight Bolivian informants, whose ancestors came from the once conservative community of Menno, turn out to be syntactically more progressive. In comparison to a Brazilian informant, their odds of producing the V(P)R variants are 3.2 times greater, though this difference only represents a statistical tendency (p = 0.064). The intermediate position of the Brazilian Mennonites, who belong to the same migration wave as the progressive Mennonites from Fernheim, may be due to the fact that the anti-German language laws of the so-called Estado Novo (1937–1945) destroyed much of the community school system of German-speaking migrants in Brazil and the once important role of StG along with it.

Crucially, it is not only the research location that shows a significant F-value but also the competence in StG (without any multicollinearity problems26). While the latter effect exclusively concerns the informants’ individual competence in StG, the former effect may also be related to the different roles of StG in the six research communities. Some readers may take issue with the fact that we do not only relate the informants’ competence but also the factor research location to StG. Of course, for this factor, one could also assume that there might be syntactic differences between the two basic MLG varieties (Chortitza and Molotchna). Unfortunately, we have no relevant information about their syntax before the Mennonite migration to the Americas. The idea that the different stimulus languages in the six research locations might have had an influence has already been discarded in Section 2.2. In any case, four more points on the individual competence scale (cf. Note 2) reduce the odds of the V(P)R variants by a factor of 1.79 ((1:0.864)4). Since StG does not allow v-p-r in two-verb clusters, this prestigious variety may thus still be considered an influential roofing variety (Dachsprache) for many speakers of MLG.

Aside from the competence in StG and the research location, both age and gender show significant effect sizes. Ten more years reduce the odds of producing the V(P)R variants by a factor of 1.26 ((1:0.977)10), while the odds of a female informant are 1.65 greater than those of a male informant. One can therefore assume that v-p-r constitutes a linguistic innovation. After all, younger women seem to lead instances of change from below (cf. Labov, 2001, pp. 279–280). Crucially, the level of competence in MLG does not show a significant effect size, strongly suggesting that the odds of the V(P)R variants are not related to language attrition.

4.3. Auxiliary Verbs and their Structural Link to the Main Verb

With regard to the structural factors, both the type of auxiliary verb and the clause type show significant effect sizes. Table 4 summarizes these results.

Table 4.

Generalized linear mixed model for visible v-p-r in complement, conditional, and relative clauses (part II: structural predictors).

Table 4.

Generalized linear mixed model for visible v-p-r in complement, conditional, and relative clauses (part II: structural predictors).

| auxiliary verb | clause type | ||

| F: 96.4 *** | F: 10.5 *** | ||

| woare(n) (18.59 ***) wolle(n) (15.08 ***) mute(n) (14.48 ***) könne(n) (4.16 ***) | complement (+dat) (3.29 ***) disintegrated conditional (2.75 ***) complement (-dat) (2.51 ***) conditional (+dann) (1.42 (*)) | ||

| han | ±extraposed relative −dislocated relative (-der) ±dislocated relative (+der) conditional (-dann) | ||

| dunecontinuous (0.481 *) duneprogressive (0.393 ***) duneconditional (0.167 ***) dunehabitual (0.093 ***) | |||

Regarding the auxiliary verb, the odds of the inchoative auxiliary woare(n) (“will”) co-occurring with the V(P)R variants are 18.59 times greater than the co-occurrence of these variants with the temporal auxiliary han (“have”), the reference category. For the habitual auxiliary dune (“do”), these odds are 10.75 smaller (1:0.093). Crucially, all auxiliaries show significant effect sizes. Regarding the raising behavior of the auxiliary verbs, the very high habitual dune (decreasing odds ratio of 10.75), the very low inchoative woare(n) (increasing odds ratio of 18.59), the high modal könne(n) (“can”) (increasing odds ratio of 4.16), and the low modal mute(n) (“must”; increasing odds ratio of 14.48) behave in line with the first hypothesis in (10). The lower their location in the split IP domain (cf. (12)), the higher their odds ratio. Nevertheless, a one-dimensional look at the scheme in (12) cannot explain all of Table 4’s results. For example, judging by the rather low position of the progressive auxiliary dune (odds ratio of 0.393), which is located 15 phrases lower than Modpossibility, one would have expected its odds ratio for visible v-p-r to be much greater than those of the modal verb könne(n) (odds ratio of 4.16; cf. also the discussion of sentences <3> and <5> in Section 3.2.2), but this is definitely not the case. For this reason, the structural position of the auxiliaries in the split IP domain can be regarded as an important but insufficient factor on its own. The crucial factor in this respect is the grouping of the auxiliary verbs according to their structural link to the main verb (cf. (12)).

In Section 3.2.2, we presented some arguments suggesting that the link between modal verbs and their respective main verbs is weak, and according to the second hypothesis in (11), this weak link should allow for rather unrestricted v-p-r. The results of Table 4 support this hypothesis, as all modal verbs show (very) high values for their odds ratios. If we group woare(n) (“will”) with the modal verbs, a move justified by their functional similarity (cf., e.g., the use of the StG cognate werden as an epistemic modal verb or the discussion of MLG modal verbs below), and if we group the irrealis marker dune with the three aspectual forms of dune, we can now assume the following sequence of the auxiliary classes in (12) (< means weaker structural link):

| (24) Modal verbs (Modalroot)/woare(n) (Aspectverb) < han (Tense) < dune (Mood/Aspectspeaker/subject) |

If this sequence, which is based on Table 4, is correct, we no longer have to worry about the fact that a low functional position like that of progressive dune does not automatically lead to greater odds ratios than the high functional position of modal possibility. We can now explain this difference by pointing to the strong structural link of dune that greatly inhibits v-p-r. What remains to be explained is the internal ordering in the two auxiliary classes with several members. Regarding the category Modal verbs (Modalroot)/woare(n) (Aspectverb), the scheme in (12) suggests the following internal sequence (< means smaller odds ratios for visible v-p-r):

| (25) könne(n)possibility < wolle(n)volition < mute(n)obligation < woare(n)inchoative |

However, the sequence found in Table 4 is as in (26) (unexpected position in bold):

| (26) könne(n)possibility (odds ratio of 4.16) < mute(n)obligation (14.48) < wolle(n)volition (15.08) < woare(n)inchoative (18.59) |

The volitional modal verb wolle(n) (“want to”) is the only verb whose position is unexpected, as it displays the second greatest odds ratio (after very low woare(n)). Assuming that the hierarchy in (12) is universally correct, this result is unexpected, since the volitional phrase is located between the phrases for obligation and possibility. The fact that the odds ratio for visible v-p-r is greater with wolle(n) than with könne(n) (“can”) can therefore be regarded as expected, but the fact that the odds ratio is also slightly greater than with mute(n) (“must”) is unexpected. Seggewiß’s (2012, p. 112) description of one possible meaning of English want to may help solve this conundrum:

In the last two examples [134) so I met Jake at the pub and I said oh you want to read this before you go […]; 135) You don’t want to worry about fat], want to does not refer to the volition of the speaker but to that of the hearer and thereby expresses a recommendation or polite command. In 134), the suggestion or recommendation implied by want to can be substituted by should and in 135), don’t need to would be an appropriate alternative to want to.

A single look at the stimulus sentences <35> and <36>, which are responsible for 523 of the 613 tokens with wolle(n) (85.3%), makes it clear that a possible reading of them is relatable to Seggewiß’s description.

| (27) | a. | stimulus <35> Is this the film you want to show to all your friends? |

| b. | stimulus <36> The doctor who wants to see my foot is very worried. |

One is probably not far off the mark if one assumes some surprise on the part of the speaker of sentence <35>. This person could also have said “I’m not quite sure if it is a good idea to show this film to all your friends” or “You had better not show this film to all your friends”. It is certainly no coincidence that two informants used the obligatory modal verb mute(n) (“must”) instead of expected wolle(n), thus hypothesizing about an external obligation that forces the hearer to act in this way. Similarly, the relative clause of sentence <36> does not represent a typical case of volition. The worried doctor certainly does not want to see the speaker’s foot as part of his personal desires; it is rather the case that s/he is obligated to see a person’s foot as part of his/her job. In line with this assumption, four informants used the modal verb solle(n) (“should”) instead of wolle(n). A further important clue for the behavior of wolle(n) comes from Seggewiß’s (2012, p. 112) summary with regard to want to:

Want to is apparently gaining ground as a modal marker, displaying new modal meanings. It is not only used for the expression of volition but is also beginning to be used as a future marker and as a marker of polite obligations.