Abstract

Accurate perception of deformable objects on the lunar surface is essential for autonomous construction and in situ resource utilization (ISRU) missions. However, the lack of representative lunar imagery limits the development of data-driven models for pose estimation and manipulation. We present SynBag 1.0, a large-scale synthetic dataset designed for training and benchmarking six-degree-of-freedom (6-DoF) pose estimation algorithms on regolith-filled construction bags. SynBag 1.0 employs rigid-body representations of bag meshes designed to approximate deformable structures with varied levels of feature richness. The dataset was generated using a novel framework titled MoonBot Studio, built in Unreal Engine 5 with physically consistent lunar lighting, low-gravity dynamics, and dynamic dust occlusion modeled through Niagara particle systems. SynBag 1.0 contains approximately 180,000 labeled samples, including RGB images, dense depth maps, instance segmentation masks, and ground-truth 6-DoF poses in a near-BOP format. To verify dataset usability and annotation consistency, we perform zero-shot 6-DoF pose estimation using a state-of-the-art model on a representative subset of the dataset. Variations span solar azimuth, camera height, elevation, dust state, surface degradation, occlusion level, and terrain type. SynBag 1.0 establishes one of the first open, physically grounded datasets for 6-DoF-object perception in lunar construction and provides a scalable basis for future datasets incorporating soft-body simulation and robotic grasping.

1. Introduction

In recent years, there has been renewed interest in a return to, and permanent settlement on, the moon. Space agencies around the world, in particular NASA and CSA, have announced goals to establish a permanent or semi-permanent presence on the moon within the next ten years. However, the lunar surface is a harsh environment with temperature swings from approximately −173 °C to +127 °C experienced between lunar night and lunar day [1], continuous exposure to solar and cosmic radiation, and micro-meteor bombardment [2,3]. This hazardous nature makes the use of artificial intelligence and robotic automation key components, as human presence in the open will need to be minimized. As such, any long-term presence on the moon will require the construction of robust shelters that can withstand lunar environmental conditions [4].

The ability to exploit lunar resources in situ for the construction of a lunar base, rather than relying on constant transportation of materials from Earth, is critical to enabling a long-term lunar presence. MDA Space is leading an international consortium of researchers to address the problem of the construction of semi-permanent lunar structures using sandbags filled with lunar regolith [5,6].

Regolith [7] is a dusty substance made of pulverized fragments of lunar rock that covers most of the surface of the moon. Regolith thickness varies significantly by region (e.g., several meters in mare regions and up to 10 m in highlands) [8]. As such, there is an ample quantity for use in construction projects. The use of regolith in sandbags is preferred over other forms of in situ resource exploitation, in particular, 3D printing or the manufacture of local concrete, as the scarcity of easily exploitable surface water makes any fluid extrusion process impractical.

Lunar construction is expected to deploy the use of autonomous or semi-autonomous mobile robots for the filling, manipulation, and placement of these regolith bags [4]. One of the main problems in such a construction project will be the grasping of the bags. A typical robotics grasping application must identify the object of interest, identify the object’s pose, i.e., its position and orientation relative to the robot, then plan a grasp strategy that will immobilize the object and allow the robot to support it [9]. Grasping and manipulation of rigid bodies is well understood and often exploited by industrial robots in the literature and practice. However, a bag of sand is considered a deformable object, and the grasping of deformable objects is much more complex and less understood in the literature. There has been significant success in modeling cloth and rope-like objects, which can be modeled in one or two dimensions, but the sandbag is a fully three-dimensional object. Additionally, unlike soft tissues, often modeled in medical applications [10], the sandbag will only experience a small amount of elastic deformation and will mainly undergo plastic deformation and adopt a new shape.

The problem of grasping regolith bags on the moon is further complicated by low gravity and harsh lighting conditions. Although the regolith bag can be expected to deform under the influence of gravity, depending on how it is placed, it will sag in strange ways. This is due to significantly lower lunar gravity compared to Earth’s gravity, and because the absence of erosion means that the lunar regolith is characterized by sharp crystalline shards that do not interact with each other in the same way as neatly rounded Earth grains of sand [11]. Secondly, as the Moon has no atmosphere, there is no Rayleigh or Mie scattering, with direct sunlight being the only significant natural source of illumination. As a result, the lunar surface experiences extreme lighting contrasts. At low solar elevation angles, objects cast pitch-black shadows with near-zero visibility in shaded regions, while at higher solar elevations, the absence of diffuse light causes scenes to appear flat and washed out, with little perceptual depth.

A survey of recent results in grasping deformable objects suggests that modern deep neural networks, trained on synthetic data sets, provide a promising solution [12,13]. The use of synthetic data sets and learning through domain adaptation [14] are especially important in the context of our problem because the unique conditions on the moon mean that it is not only difficult and time-consuming, but impossible for us to create a representative terrestrial data set.

Motivated by these challenges in replicating lunar conditions and the lack of suitable real-world or synthetic datasets, we present a photorealistic lunar simulation environment built using Unreal Engine 5. This framework, named MoonBot Studio, provides an automated pipeline for generating large-scale synthetic datasets for robotic perception in lunar environments. Using this framework, we generate the SynBag 1.0 dataset to train and evaluate 6-DoF pose estimation models for deformable construction materials. We further benchmark state-of-the-art object pose estimation approaches on the dataset to assess their robustness under lunar lighting, dust, and surface degradation conditions. MoonBot Studio is presented as a general-purpose framework for photorealistic lunar data generation, while SynBag 1.0 represents its first concrete dataset instantiation, focused on instance-level 6-DoF pose estimation of regolith bags under lunar illumination conditions. The SynBag dataset is publicly available via the DOI provided in the Data Availability Statement. The MoonBot Studio framework is intended to be released as open-source.

2. Related Works

2.1. Synthetic Datasets for Object Detection and Pose Estimation

Several large-scale synthetic datasets have been developed to advance research in object detection and six-degree-of-freedom (6-DoF) pose estimation, particularly for terrestrial or indoor environments. The Falling Things dataset, introduced by NVIDIA Research, provides approximately 60,000 annotated RGB images with corresponding 3D pose labels for household objects rendered in realistic indoor backgrounds [15]. This dataset demonstrated the potential of high-fidelity rendering for data-driven perception tasks; however, its focus on household scenes and Earth-like illumination limits its applicability for training models intended for extraterrestrial robotic operations.

More recently, the Synthetica framework proposed a scalable synthetic data generation approach using NVIDIA Omniverse Isaac Sim to produce over 2.7 million photorealistic images for training detection transformers in industrial settings [16]. While this work demonstrated strong sim-to-real transfer performance in structured manufacturing environments, the generated data primarily depicts rigid industrial or household objects. Consequently, it lacks the physical and visual properties characteristic of lunar environments, such as low gravity, regolith surfaces, and extreme lighting contrasts.

2.2. Synthetic Simulators for Lunar Robotics

Among existing simulation frameworks for planetary robotics, the OmniLRS (Omnidirectional Lunar Robotics Simulator) is the most comparable to our work. Developed by researchers at Tohoku University’s Space Robotics Laboratory, OmniLRS builds on NVIDIA Isaac Sim to create a photorealistic digital twin of lunar analog environments, including both indoor facilities such as Lunalab and procedurally generated outdoor terrains [17]. The simulator includes ROS integration, procedural terrain generation, and automated annotation of RGB images, 2D bounding boxes, and instance segmentation masks through the Isaac Replicator pipeline. Its primary application is rock detection and instance segmentation, where models trained on synthetic data are compared against real-world imagery from the analog lab. While OmniLRS demonstrates strong visual realism and valuable sim-to-real transfer for 2D perception tasks, it does not report or release ground-truth 6-DoF object pose annotations in a BOP-style format, and it is not presented as a dataset for RGB-D pose estimation benchmarking. Consequently, it is not directly suited for evaluating or training models for pose estimation or manipulation.

Our framework, MoonBot Studio, extends beyond 2D vision by targeting large-scale, physically consistent data generation for 6-DoF object pose estimation under lunar conditions. We use Unreal Engine 5.5.4 (Epic Games, Cary, NC, USA) for photorealistic rendering with adjustable gravity and physically based lighting, producing RGB images, YOLO-formatted bounding boxes, instance segmentation masks, and dense depth maps. In addition, we generate full ground-truth 6-DoF object annotations in a near-BOP format to enable benchmarking of state-of-the-art pose estimation algorithms and to support future work on object grasping in lunar construction contexts. Our simulator also introduces visual and material realism effects not addressed by OmniLRS, including dynamic dust occlusion from rover motion and gradual regolith staining that degrades the bag’s appearance over time. These features collectively make MoonBot Studio one of the first open frameworks for scalable, physically grounded 6-DoF dataset generation and perception benchmarking for deformable lunar construction materials.

In addition to OmniLRS, several high-fidelity lunar simulation frameworks have been developed to support mission planning and perception research. NASA’s Digital Lunar Exploration Sites Unreal Simulation Tool (DUST) [18] is among the most advanced Unreal Engine–based systems designed for modeling surface lighting, topography, and terrain curvature at the lunar south pole. Although DUST is not open source, its pipeline leverages NASA’s SPICE kernels for Sun–Earth positioning and incorporates Digital Elevation Models (DEMs) from the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter to reconstruct realistic lunar landscapes. Its methodological use of DEM data inspired our own approach to heightmap generation and curvature correction within Unreal Engine.

Similarly, the LunarSim environment by Pieczyński et al. [19] employs Unity and ROS 2 integration to simulate lunar surface operations for computer vision and SLAM applications. LunarSim provides procedural illumination control and ROS-based synchronization for perception tasks, but lacks direct access to its scene generation source code or datasets. NASA’s VIPER simulation platform [20], developed for the Volatiles Investigating Polar Exploration Rover, likewise integrates realistic physics and lighting for mission rehearsal but remains closed to external research use.

While these frameworks demonstrate impressive photorealism and physics fidelity, their closed or proprietary implementations limit accessibility for dataset generation and algorithm benchmarking. In contrast, MoonBot Studio offers a fully open and modular Unreal Engine–based solution focused on generating scalable, labeled datasets for 6-DoF pose estimation and deformable-object perception under realistic lunar conditions.

2.3. Synthetic Data Generation in Other Domains

The recent adoption of modern game engines for dataset creation extends beyond robotics. UnrealVision [21], a system developed by Thinh Lu at San José State University, utilizes Unreal Engine 5 to generate annotated datasets for human-pose estimation and behavior analysis. The system automates camera placement, scenario generation, and annotation workflows to efficiently produce labeled training data for YOLO-based pose models. Similarly, the work by Khullar et al. on Synthetic Data Generation for Bridging the Sim2Real Gap in a Production Environment [22] applies Omniverse-based rendering to industrial robotics tasks. Although these frameworks highlight the advantages of synthetic data for vision-based learning, their scenes remain Earth-bound and rigid, lacking the physical realism and environmental complexity of lunar construction scenarios.

Overall, while existing synthetic datasets have advanced object detection and pose estimation in Earth-like environments, none incorporate the combined effects of low gravity, single-source illumination, dust occlusion, and material surface degradation characteristic of the lunar surface. Table 1 summarizes existing lunar simulation frameworks and datasets, highlighting that prior open tools either lack dense depth and 6-DoF pose ground truth or are not available for open dataset generation and benchmarking. To our knowledge, no prior open-source framework enables the large-scale generation of labeled data for the pose detection of construction materials under lunar conditions. To address this gap, we introduce the MoonBot Studio framework for photorealistic image and pose data generation of regolith-filled bags alongside the SynBag 1.0 dataset. This dataset serves as a foundation for benchmarking state-of-the-art 6-DoF pose estimation algorithms and advancing perception research in lunar robotics.

Table 1.

Comparison of lunar simulation frameworks and dataset capabilities.

3. Dataset Generation Methodology

3.1. Lunar Environment Modeling and Scene Composition

To construct a physically accurate and visually consistent lunar surface for dataset generation, we developed a custom terrain using topographic data from NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) Laser Altimeter (LOLA) and the SELENE Terrain Model fusion dataset, SLDEM2015 [23]. This digital elevation model (DEM), produced by NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, provides a global lunar topography map with a spatial resolution of approximately 118.45 m per pixel and a vertical accuracy of about 3–4 m. The dataset was downloaded as a GeoTIFF file and processed using the Geospatial Data Abstraction Library (GDAL). Elevation values ranging from to were linearly scaled and converted to a 16-bit PNG heightmap for compatibility with Unreal Engine 5’s Landscape mode. This heightmap was then imported to generate the base lunar terrain geometry.

For surface appearance, a custom Lunar Surface Material was developed using physically based rendering principles. A desaturated “Desert Sand” texture was adapted to approximate the gray albedo of lunar regolith, with additional maps for normal, roughness, and ambient occlusion. This albedo selection represents a fixed intrinsic surface property of the terrain and remains constant across all scenes. In contrast, surface staining applied to regolith bags (Section 3.4) models appearance-level contamination due to dust and regolith coverage and does not modify the underlying material albedo.

To eliminate the repeating tiling artifacts typical of UV-mapped textures on large terrains, all texture layers were projected using Unreal’s WorldAlignedTexture node, enabling seamless mapping in world coordinates. Macro- and micro-scale variation was further introduced through an imperfection mask derived from an AmbientCG texture, applied as a color-channel mask with sRGB disabled to preserve raw scalar data. This combination of world-aligned projection and low-frequency modulation produces natural surface heterogeneity without visible repetition.

Lighting was configured to reproduce the single-source illumination of the lunar surface. A directional light was used to represent the Sun, with adjustable azimuth and elevation to emulate varying solar incidence angles. A SkyAtmosphere actor was added with Rayleigh and Mie scattering coefficients set to zero, resulting in a black sky consistent with the Moon’s lack of atmosphere. A global PostProcessVolume (set to infinite extent and unbound) was used to manually control camera exposure and contrast, preventing Unreal Engine’s automatic tone-mapping from artificially brightening shadowed areas.

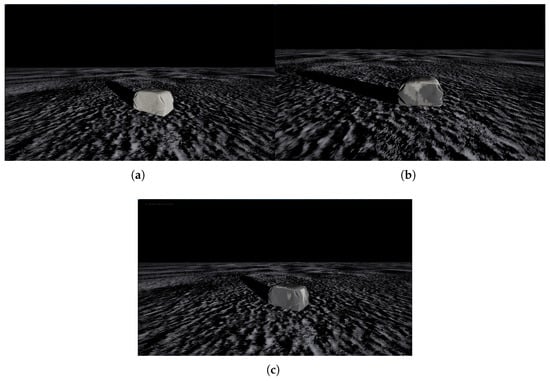

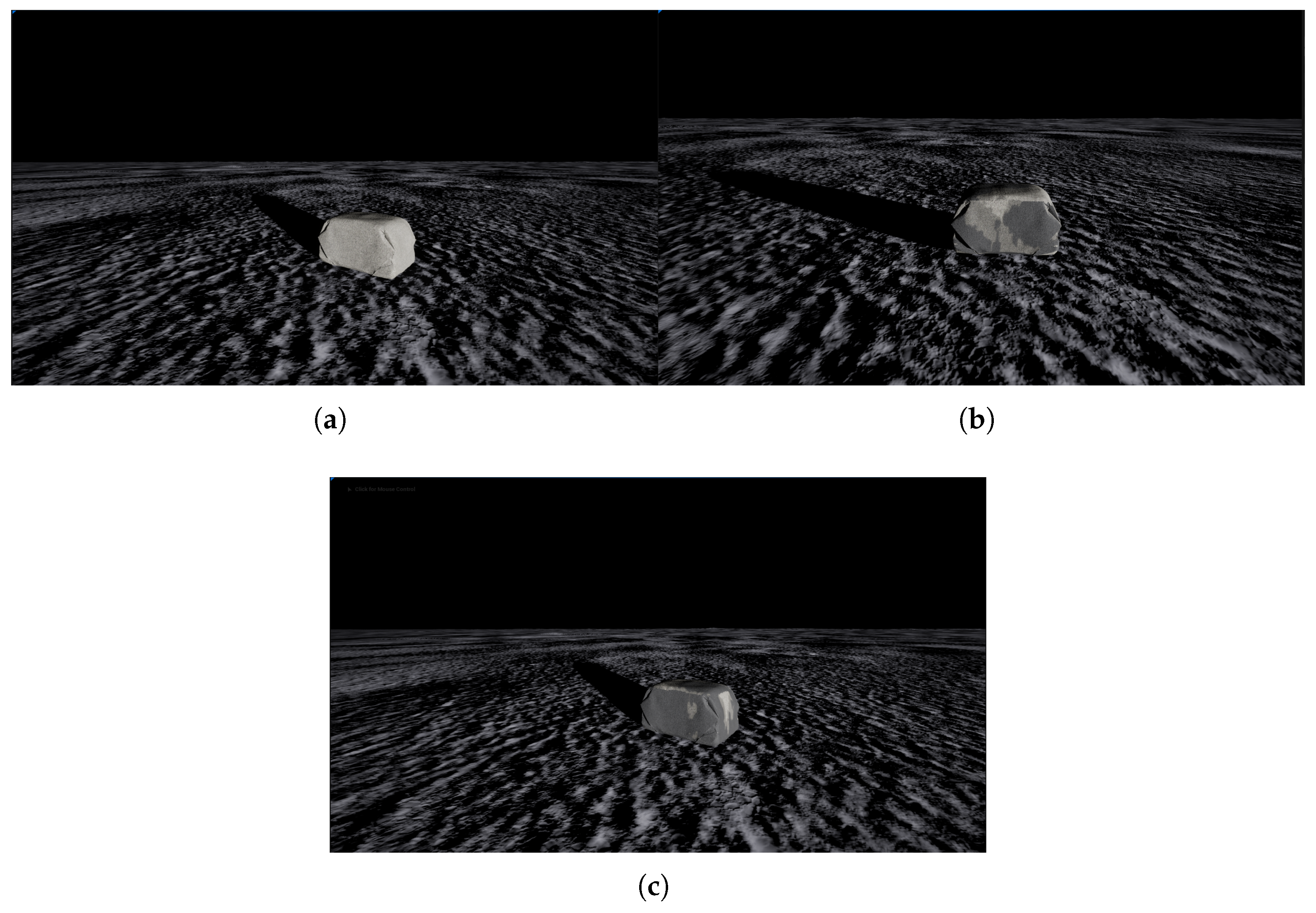

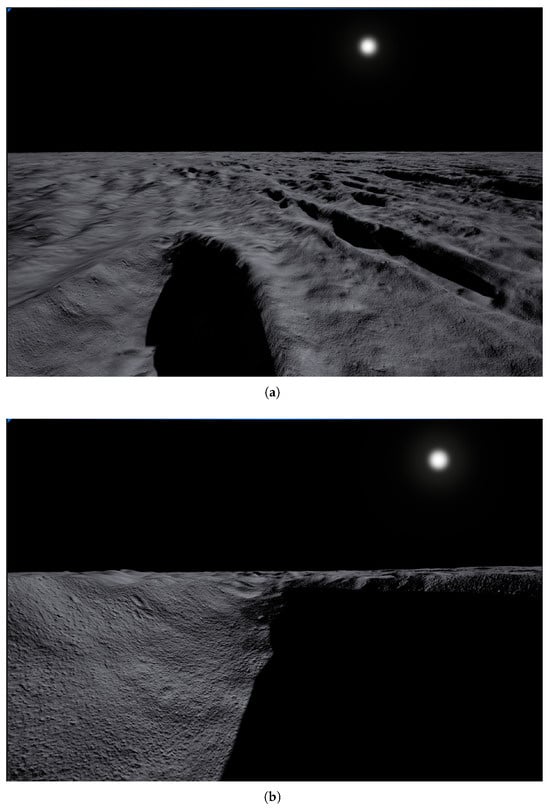

The resulting environment achieves photometric and geometric realism suitable for perception benchmarking. Figure 1 illustrates the simulated lunar surface from an orbiting camera viewpoint in a cratered lunar terrain region, highlighting the stark lighting contrast produced by single-source illumination at low solar elevation angles. The terrain geometry is derived from the global SLDEM2015 DEM [23], and the crater scene represents a cropped region used to highlight shadowing effects.

Figure 1.

(a) DEM-based lunar terrain as seen from an orbit camera viewpoint in MoonBot Studio. (b) Extreme lighting contrast caused by crater shadow at low solar elevation angle.

3.2. Dust Occlusion Simulation

To simulate the transient dust plumes expected during lunar surface operations, a custom Niagara particle system (NS_LunarDustZone) was developed in Unreal Engine 5. This system combines two emitters to represent both granular ejecta and the diffuse dust cloud that forms upon disturbance of the regolith surface.

The first emitter generates small particulate fragments using a granite rock mesh sourced from the FAB asset repository. The mesh is rendered through a Mesh Renderer module, with particle scaling randomized between 1% and 2% of the mesh’s original dimensions (Mesh Scale Min = 0.01; Mesh Scale Max = 0.02). This corresponds to particle diameters of roughly 1–2 cm, comparable to the coarse fraction of lunar regolith as reported in Apollo sample analyses. The emitter launches these particles upward in a cone with an axis of and a half-angle of 45°, at a mean velocity of 50 cm·s−1. Gravity was applied at –162 cm·s−1, equivalent to lunar surface gravity (–1.62 m·s−1), with collisions enabled through CPU ray tracing. A coefficient of restitution of 0.4 and a friction coefficient of 0.6 were used, drawn, respectively, from Khademian et al. [24] and the NASA (1970) report Basic and Mechanical Properties of the Lunar Soil Estimated from Surveyor Touchdown Data [25]. The emitter loops indefinitely at two-second intervals to maintain a continuous regolith disturbance effect.

The second emitter represents the fine dust cloud. It spawns particles within a box-shaped volume (70 × 200 × 50 cm) using a Box/Plane shape primitive. Particles are emitted upward in a cone (axis = (1, 0, 500), angle = 45°) with an initial velocity of 70 cm·s−1 and a vertical position offset of –170 cm, ensuring that only the wispy upper portion of the dust layer remains visible within the camera frame. Alpha fading is applied using a Scale Color module, where the RGB component remains constant (1, 1, 1) and the alpha follows a float-curve function that rises rapidly and then decays over the particle’s normalized lifetime. The particle lifetime was set to 5 s, resulting in a short-lived, semi-transparent haze. This emitter uses the M_Smoke material from the Realistic VFX Pack to approximate the diffuse scattering properties of fine lunar dust suspended in low-gravity conditions.

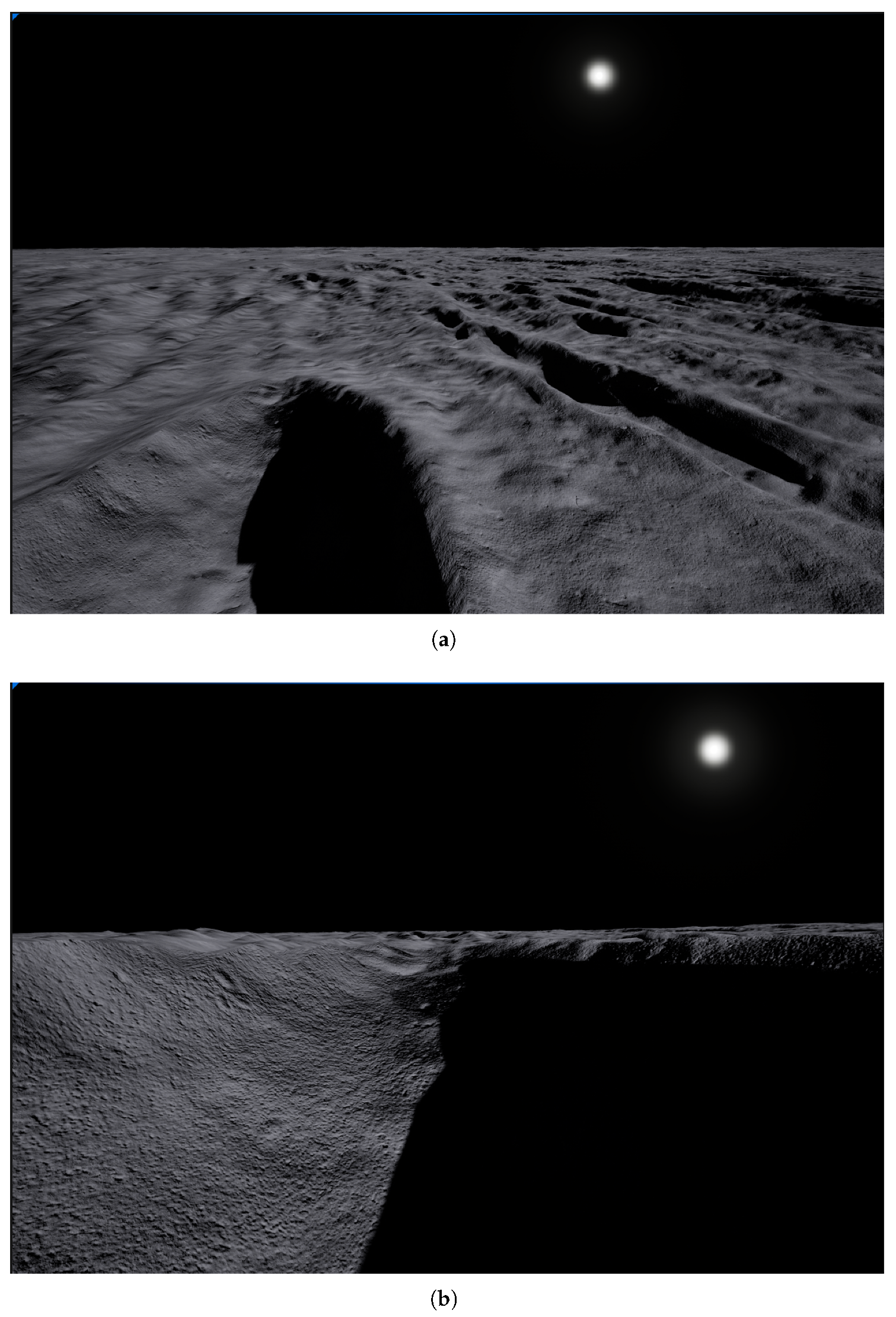

Together, these two emitters provide a visually and physically grounded approximation of regolith agitation and dust occlusion under lunar gravity, as shown in Figure 2, allowing pose estimation algorithms trained on the dataset to be evaluated for robustness against partial visibility and volumetric scattering effects.

Figure 2.

Dust Plume Effect close up.

3.3. Bag Mesh Modeling and Variants

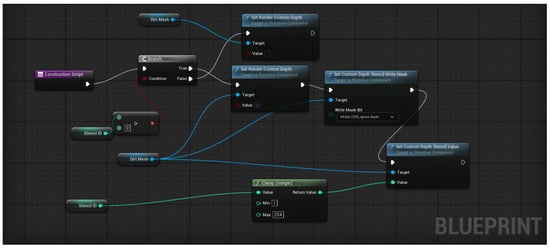

3.3.1. Blueprint Integration and Custom Depth Setup

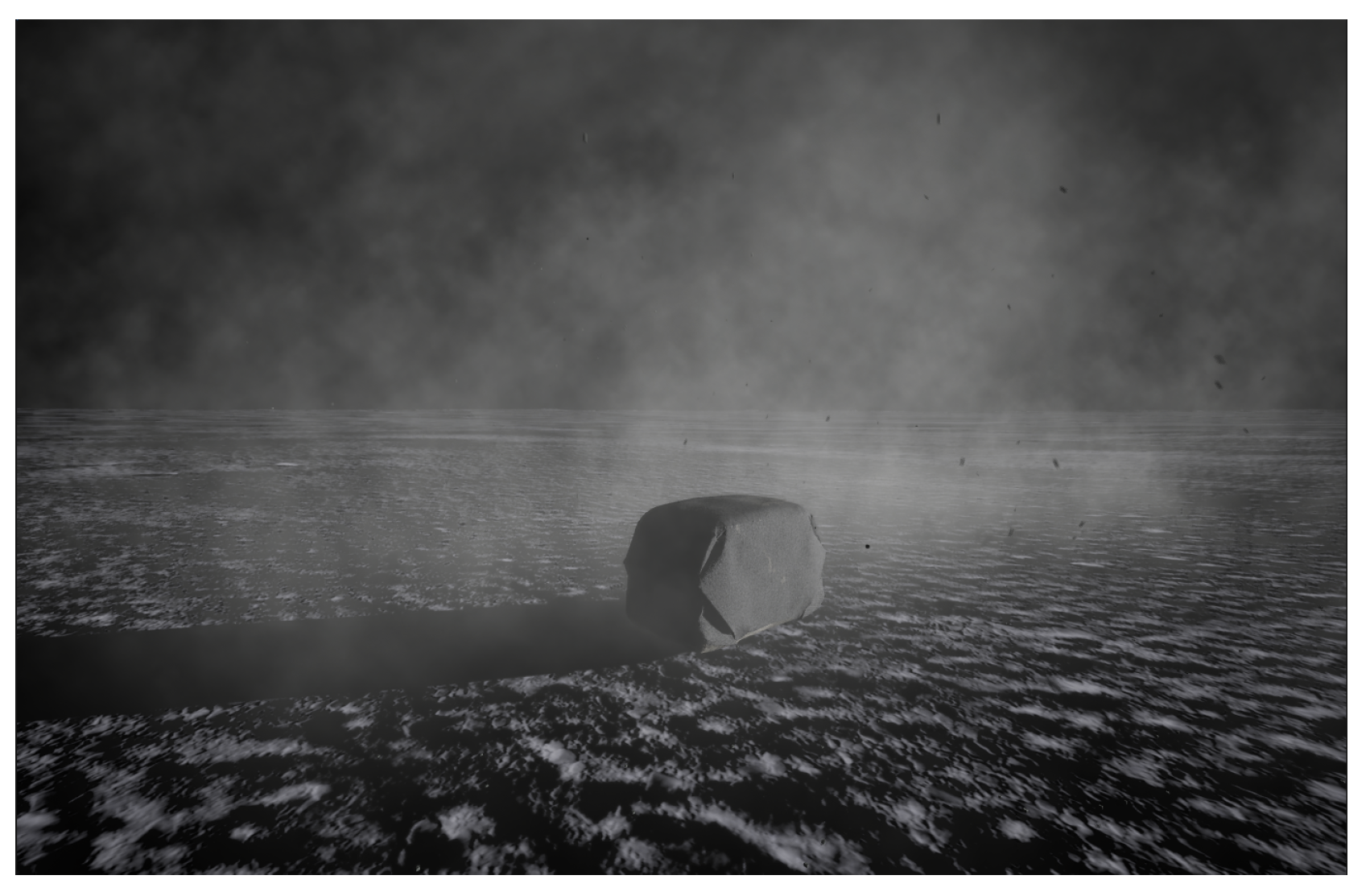

To enable flexible integration of different bag geometries into the dataset generation pipeline, a modular Unreal Engine 5 Blueprint system was developed. Unreal Engine 5’s Blueprint system is a node-based visual scripting environment for procedural scene logic. The Blueprint developed serves as the core interface for all regolith bag assets, allowing any newly modeled mesh, whether from Blender or other 3D design tools, to be automatically incorporated into the simulation environment without additional manual setup.

The Blueprint’s Construction Script (Figure 3) initializes key rendering and segmentation parameters used throughout the data generation process. Specifically, each bag instance is assigned a unique Stencil ID, which is clamped between predefined limits (1–255) and applied through Unreal’s Custom Depth Stencil Buffer. This enables per-instance segmentation and supports later stages of automated ground-truth generation for 2D masks, depth maps, and object-level annotations. The Blueprint also ensures that Custom Depth Rendering is enabled for each mesh, making every bag instance visible to the segmentation and depth capture passes executed in the automated data generation pipeline.

Figure 3.

Unreal Engine 5 Blueprint Construction Graph for Bag Actor.

This modular design allows researchers to replace or modify bag meshes dynamically, whether rigid or deformable, while maintaining consistent data annotation behavior. Subsequent subsections expand on how this Blueprint framework integrates with the dynamic bag surface degradation system and the automated data generation process, where the assigned stencil values are used to render and extract object-level labels.

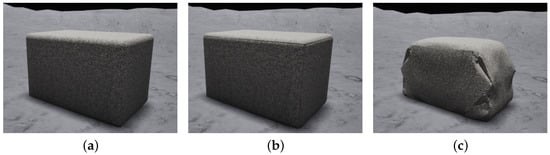

3.3.2. 3D Mesh Design and Rendering

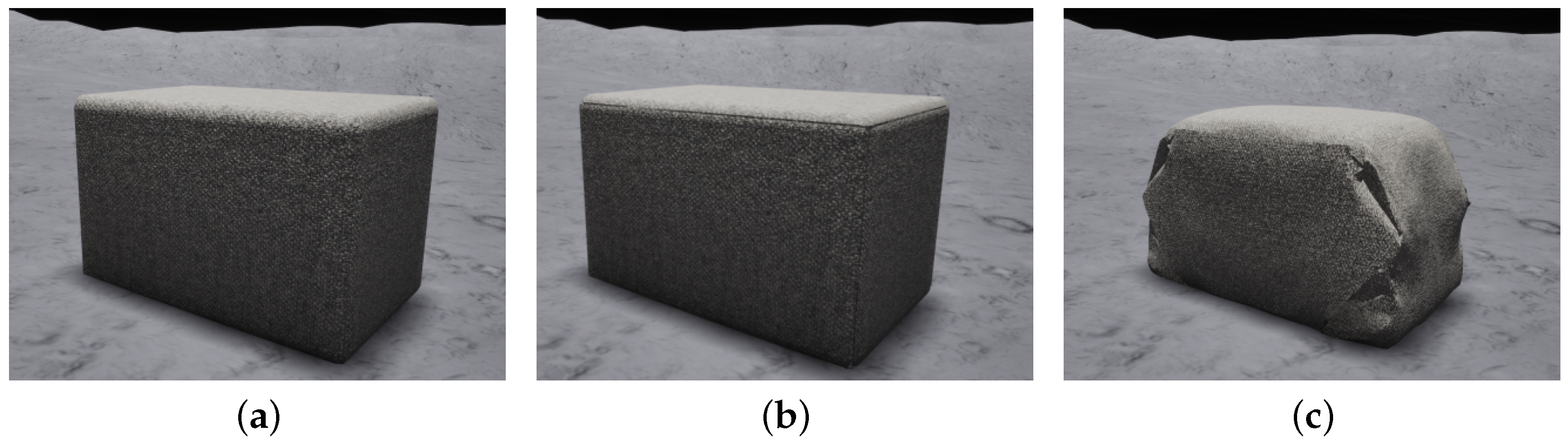

As shown in Figure 4, the sandbag meshes increase in geometric feature richness. Sandbag-01 is a simple cuboid with minimal surface detail. Sandbag-02 introduces stitched seams along the edges that add visual features, and Sandbag-03 includes folded ends and a more realistic-looking surface. These mesh variants are used to evaluate how increasing geometric and feature richness influences performance when the dataset is used for downstream computer vision tasks.

Figure 4.

Sandbag mesh variants with increasing geometric feature richness. (a) Sandbag-01: Cuboid, (b) Sandbag-02: Cuboid with seams, (c) Sandbag-03: Folded ends.

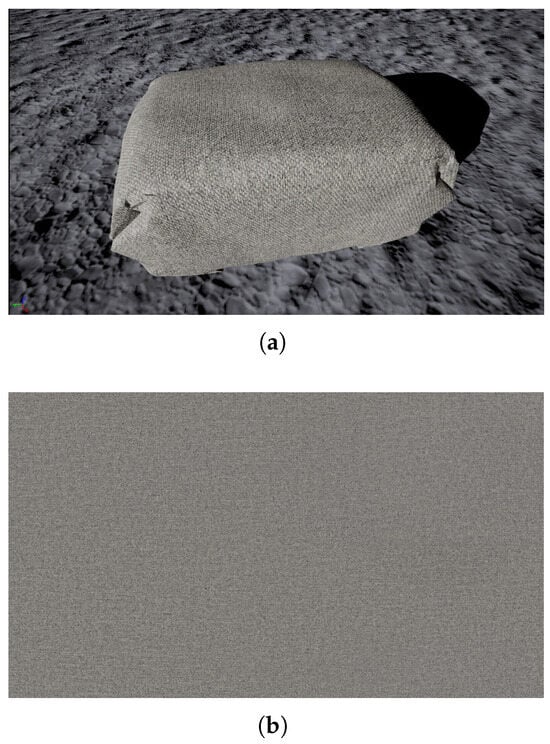

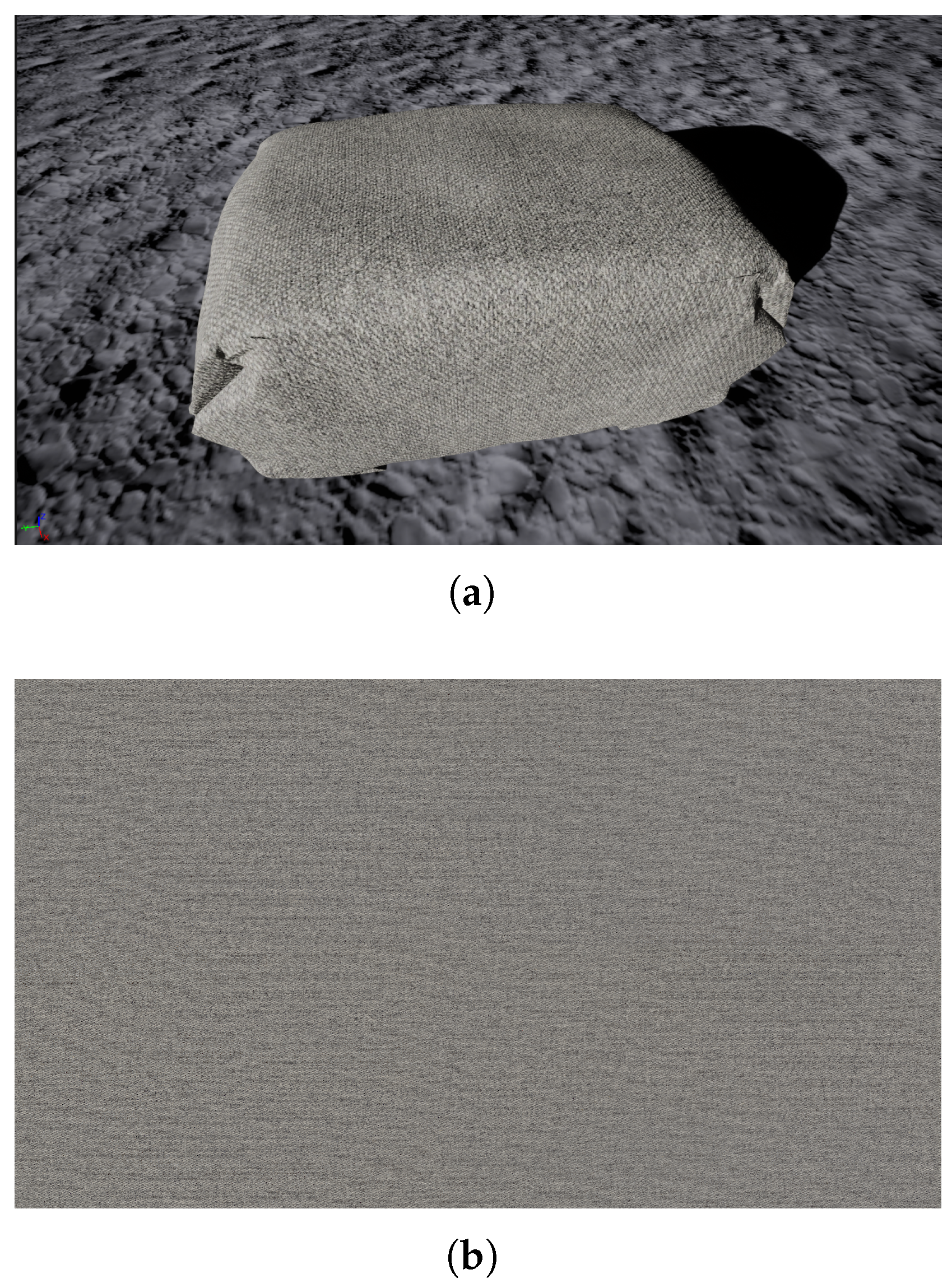

The regolith bag surface was modeled using a tightly woven fabric texture to approximate early conceptual prototypes of the regolith construction unit (RCU) cloth currently under development through industry collaboration. The selected texture exhibits a fine, uniform weave pattern with minimal high-frequency visual features, which aligns with the expected design goal of producing durable, tightly packed bags with limited surface irregularity. The weave is assumed to have low porosity and sufficient thickness to maintain structural rigidity when filled with regolith, consistent with early design discussions. A wool-based material from the Fab asset library was chosen as a visually similar proxy due to its consistent fiber structure and near-featureless reflectance properties.

Figure 5 presents a close-up rendering of the bag mesh with the applied material, alongside the base color texture used for the fabric. The texture resolution (8192 px/m) ensures that weave details remain consistent across viewing distances while avoiding exaggerated visual features that could bias pose estimation models. Material properties were defined using physically based rendering parameters, with ambient occlusion, base color, normal, and roughness maps derived directly from the texture set. Metallic values were set to zero to reflect the non-metallic nature of woven cloth.

The primary objective of this texture selection was not to replicate the exact fiber composition of a finalized RCU material, but rather to provide a realistic, low-contrast fabric surface that minimizes artificial visual cues while preserving plausible appearance under single-source lunar illumination. This design choice ensures that the generated dataset supports the development of pose estimation models that generalize across lunar geometric and lighting conditions, rather than encouraging reliance on distinctive texture patterns.

Figure 5.

(a) Close-up of bag with folded ends at “Clean” stain level as defined in Table 2. (b) Close-up of the base fabric texture used for the bag material, showing the tightly woven, low-porosity surface designed to minimize high-frequency visual features.

Table 2.

Dirt parameter configurations used to generate varying levels of surface contamination in the dataset.

Figure 5.

(a) Close-up of bag with folded ends at “Clean” stain level as defined in Table 2. (b) Close-up of the base fabric texture used for the bag material, showing the tightly woven, low-porosity surface designed to minimize high-frequency visual features.

3.4. Dynamic Bag Surface Staining

3.4.1. Motivation

During lunar construction operations, regolith-filled bags are expected to undergo repeated handling, dragging, and contact with the surface, resulting in visible surface staining and contamination. Although SynBag 1.0 represents bags as rigid bodies, modeling this appearance-level degradation is important for training robust vision systems, particularly under extreme lunar lighting, where subtle texture variations can significantly influence perception. To address this, we implemented a surface degradation algorithm that generates randomized dirt patterns on bag surfaces while remaining computationally efficient and scalable for large-scale synthetic dataset generation.

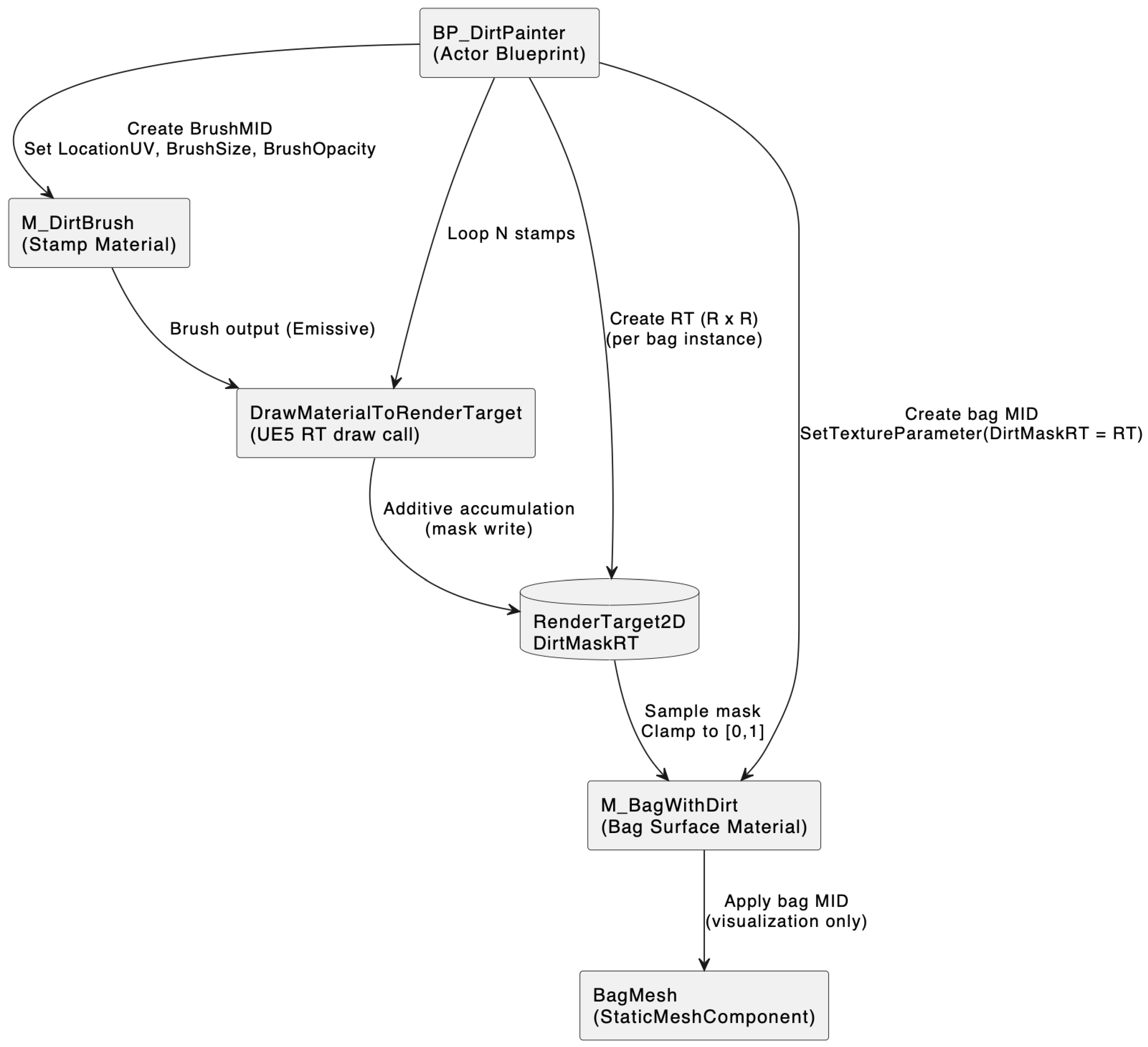

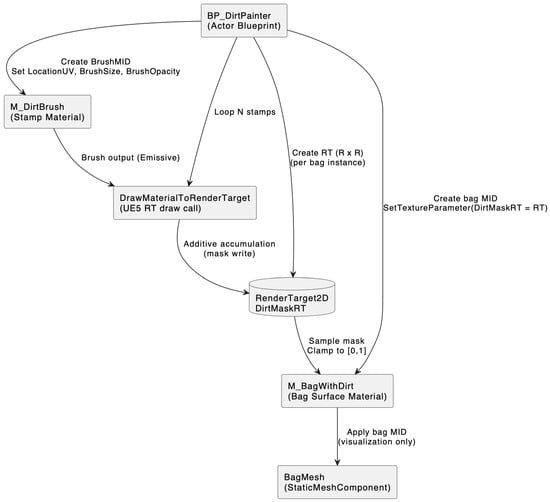

3.4.2. Overview of the Dirt Painting Algorithm

The surface degradation was implemented using a render-target-based mask painting approach. For each bag instance, a per-instance 2D render target is allocated at initialization to store a dirt coverage mask. Dirt patterns are generated by repeatedly stamping a brush material into this render target at randomly sampled UV coordinates. The resulting grayscale mask is then sampled by the bag’s surface material to blend between a clean and dirt-tinted appearance. This design cleanly separates mask generation from appearance application: a dedicated brush material (M_DirtBrush) is responsible solely for writing dirt stamps into the render target, while the bag material (M_BagWithDirt) interprets the final mask to modify the rendered surface.

Let define the UV coordinate space of the dirt mask render target. The dirt mask is generated by accumulating N contributions:

where is a fixed grayscale splat texture, is stamp opacity, is the brush size, and is an affine transform that recenters and rescales coordinates around a randomly generated stamp center :

Operationally, each stamp is rendered by evaluating the brush material once and drawing it into the render target using Unreal Engine’s DrawMaterialToRenderTarget function. The brush material computes the local UV coordinate and clamps it component-wise to , samples a single splat texture, and outputs the sampled red channel through the emissive output. The material uses additive blending, so successive stamps accumulate rather than overwrite, naturally producing higher mask values in regions of overlap. The render target is initialized empty with per-instance allocation at begin play. The splat texture used for stamping is sourced from a commercially available Unreal Engine Marketplace asset originally intended for liquid effects [26].

3.4.3. Bag Material Application

The bag surface material (M_BagWithDirt) samples the generated render target via the texture parameter DirtMaskRT. The sampled grayscale value is clamped to and used directly as the blend weight in a linear interpolation between the clean bag texture and a dirt-tinted variant. Specifically, the dirt-tinted branch is formed by multiplying the clamped mask value by a user-defined DirtColour parameter, while the same clamped value serves as the interpolation coefficient. The output of this interpolation is connected to the Base Color input of the material. This formulation ensures that dirt intensity increases smoothly with accumulated mask overlap while remaining completely appearance-based. No physical deformation is modeled at this stage. As shown in Figure 6, the BP_DirtPainter actor orchestrates mask generation by repeatedly drawing a stamp material into a per-instance render target.

Figure 6.

System level diagram of the procedural dirt painting pipeline used for surface degradation in SynBag 1.0. A Blueprint actor (BP_DirtPainter) orchestrates mask generation by repeatedly drawing a stamp material (M_DirtBrush) into a per-instance render target. The accumulated grayscale mask (DirtMaskRT) is then sampled by the bag surface material (M_BagWithDirt) to modulate the appearance before being applied to the bag mesh.

3.4.4. Blueprint Integration

Mask generation is orchestrated by a Blueprint actor (BP_DirtPainter). At the beginning of play, the Blueprint allocates the dirt mask render target, creates dynamic material instances for the bag material and the brush material, and assigns the render target to the bag material’s DirtMaskRT parameter. A loop is then executed for N iterations, where each iteration samples a random stamp center , applies user-defined brush size and opacity parameters to the brush material instance, and issues a DrawMaterialToRenderTarget call. After completion, the bag mesh component is assigned the updated bag material instance. The mesh component plays no role in mask generation and serves only as the visual target for the material.

3.4.5. Parameterization and Dataset Variation

To support randomization and controlled appearance variation within the bags, the dirt painting algorithm exposes several high-level parameters that can then be varied across dataset configurations. These parameters control the density, spatial extent, and visual prominence of dirt accumulation. These parameters are the number of stamps (seeds), brush size, and brush opacity. This parameterization enables systematic exploration of surface appearance degradation while maintaining reproducibility and a low computational overhead. In the current dataset release, both brush size and brush opacity are held constant, with the variation achieved by adjusting the number of stamps. The visual effects caused by differing parameter combinations are shown in Table 2 and Figure 7.

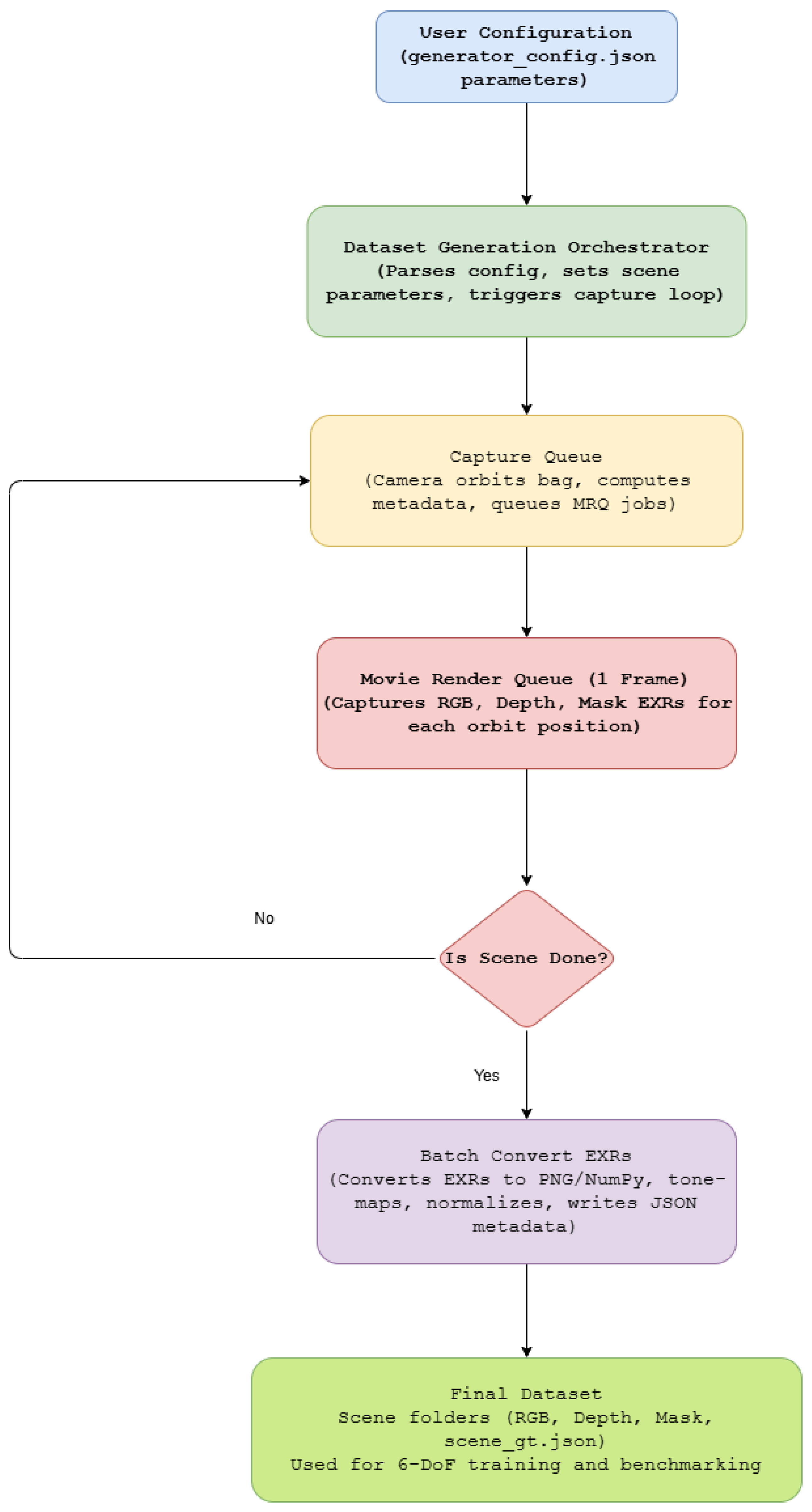

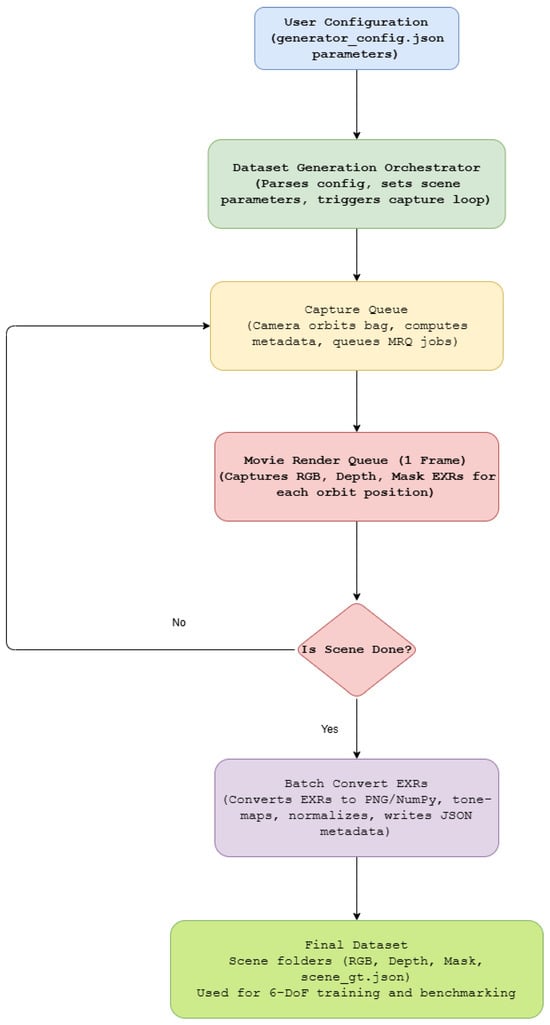

3.5. Automated Data Generation Pipeline

To ensure scalable and reproducible dataset generation, a modular automation framework was implemented in Python using the experimental Python API available in Unreal Engine 5.5 (Epic Games, Cary, NC, USA). The framework is structured around a primary orchestration layer that coordinates scene variation, rendering, and metadata export across multiple modules. All configuration parameters are specified through a JSON configuration file, enabling experiment reproducibility and flexible parameter sweeps without requiring code modification.

3.5.1. System Architecture

The data generation pipeline is orchestrated through a configuration-driven control layer that sequentially iterates over predefined scene, illumination, and viewpoint parameters. A preset lunar environment is used as the base scene, containing regolith bag instances and optional atmospheric dust effects. For each parameter configuration, the pipeline automatically updates lighting conditions and camera motion, and executes a synchronized capture of RGB, depth, and segmentation outputs together with associated pose metadata. This design enables large-scale automated data generation under diverse geometric and illumination conditions with minimal human intervention.

The framework is structured around three conceptual modules:

- Capture Orchestration Modulecoordinates camera motion and capture scheduling. The camera orbits the designated target object at controlled angular increments, and for each orbit position, triggers a render pass that outputs aligned RGB, depth, and instance mask images. Per-frame metadata is computed alongside rendering, including camera intrinsics, object-to-camera poses, bounding box annotations, reference pixels on the target object, and corresponding depth estimates. An optional settling interval is supported to allow physically simulated assets to stabilize prior to capture, enabling future integration of plastic deformability and dynamic effects.

- Rendering Interface Module manages interaction with Unreal Engine’s Movie Render Queue. It configures per-frame render jobs, binds the active camera to short capture sequences, applies required post-processing passes for depth and instance segmentation, and ensures high-precision EXR output. Render jobs are isolated to per-sample directories to prevent data collisions, and a configurable warm-up phase ensures that lighting and particle systems reach a steady state prior to capture.

- Utility and Synchronization Module handles configuration parsing, deterministic random seeding, and execution scheduling to ensure reliable sequential operation. This layer enforces synchronization between capture events and rendering completion, preventing conflicts during large batch generation.

Following rendering, captured outputs are automatically organized according to the BOP (Benchmark for 6D Object Pose Estimation) directory structure. Each frame is paired with a JSON metadata entry storing the associated pose and annotation information. The pipeline additionally records throughput statistics at the batch level, enabling comparative evaluation of dataset generation performance across different hardware configurations.

3.5.2. EXR Post–Processing

Following data capture, a batch post–processing stage traverses the rendered output and materializes training–ready derivatives while preserving file stems and directory structure. The following modalities are produced:

- RGB: Linear HDR EXR images are tone–mapped using a Reinhard operator and written to 8–bit PNG format for training and qualitative inspection.

- Depth: SceneDepthWorldUnits is read as float32 metric depth in meters, sanitized to remove invalid or saturated values, and exported in three complementary representations: (i) float32 NumPy arrays in meters for learning–based pipelines, (ii) 16–bit PNG images in millimeters for compatibility with classical pose estimation frameworks, and (iii) an 8–bit preview PNG with robust normalization for rapid visual inspection.

- Masks: The raw CustomStencil EXR is quantized to a single–channel 8–bit instance ID map, with an optional colorized visualization PNG produced for debugging and verification.

3.5.3. Minimal User Setup

Scene Configuration

Scene definition in the proposed framework is intentionally lightweight, requiring only the specification of object instances and a reference target for viewpoint sampling. Each scene consists of one or more regolith bag instances arranged in either single-object or stacked configurations. One instance is designated as the orbit target, serving as the reference object for camera motion. A virtual camera is positioned relative to this target at a fixed radius, while azimuth and height variations are applied automatically according to predefined scene parameters.

Configuration Interface

The dataset generation process is driven by a centralized configuration interface that enables large-scale parameter sweeps while ensuring experimental reproducibility. Scene-independent parameters define output structure, object and camera identifiers, and scene indexing, while scene-specific parameters control illumination and viewpoint sampling, including solar azimuth, solar elevation, and camera height above the target object. An optional settling interval is supported to accommodate transient effects such as dust dynamics and, in future extensions, physically based deformability.

The modular structure of the pipeline allows individual components, such as the renderer, camera controller, or deformation solver, to be replaced or extended without modifying the orchestration logic. This design supports long-term maintainability and facilitates the reuse of the framework for future synthetic data generation campaigns. Figure 8 illustrates the end-to-end pipeline from configuration specification to post-processing.

Figure 8.

Automated data generation workflow implemented in MoonBot Studio. The process begins with user-defined configuration parameters, followed by scene orchestration, frame capture, EXR rendering, and batch conversion to structured RGB, depth, and mask datasets for 6-DoF pose estimation benchmarking.

3.6. Pose Estimation Benchmarking Framework

We perform an initial pose estimation benchmark using FoundationPose [27], a recent state-of-the-art method designed for unseen-object 6-DoF pose estimation. FoundationPose directly estimates object pose using a CAD model or a small set of reference images, given an RGB frame along with its corresponding depth map and instance segmentation mask.

Although FoundationPose is primarily designed for generalization and can estimate poses for novel objects without retraining, results reported on the BOP benchmark [28] indicate that the method can also achieve state-of-the-art accuracy on instance-level pose estimation tasks when the target object is included during training. This makes FoundationPose a suitable baseline for evaluating both zero-shot detection and the suitability of the SynBag dataset for pose estimation.

In SynBag 1.0, FoundationPose is utilised in unseen-object mode (zero-shot). We provide only the mesh for each sandbag variant, without any task-specific fine-tuning. This setting evaluates how well FoundationPose generalizes to low-texture deformable sandbags.

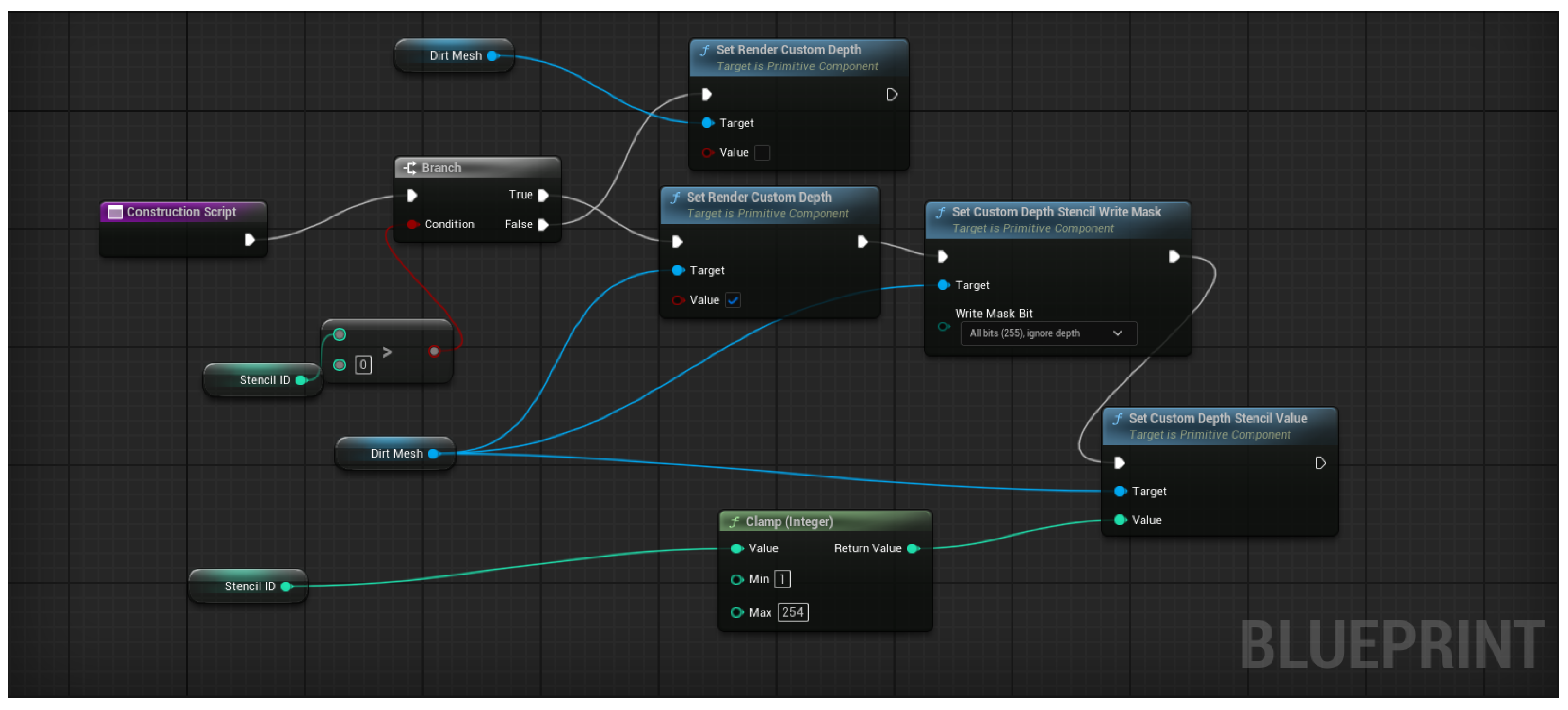

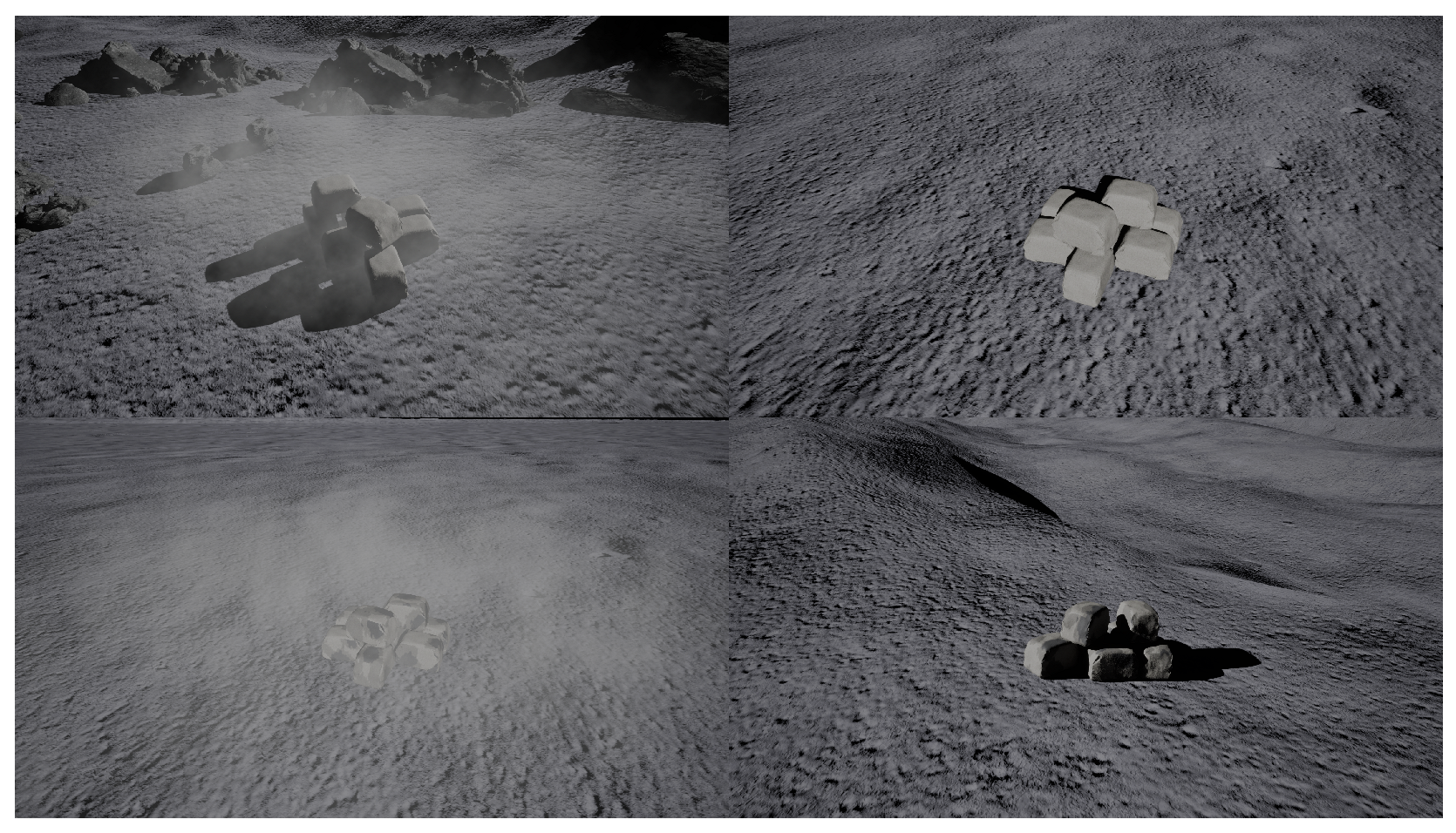

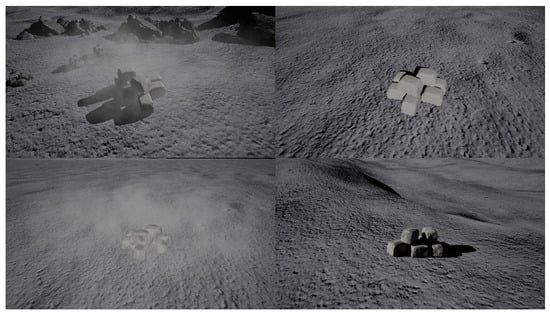

To evaluate whether the simulated dataset is suitable for reliable 6D pose estimation, we conduct a series of experiments across multiple sandbag variants with varying levels of geometric and visual feature richness, as described in the 3D mesh design section. The bags are placed in diverse environments, including flat terrain, hilly terrain, and rocky lunar scenes, and evaluated across a range of camera viewpoints. In addition, we systematically apply visual perturbations such as dirt accumulation and dust clouds. These various conditions test the robustness of pose estimation under conditions representative of realistic planetary surface conditions. Examples of these environments and perturbations are shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Examples of simulated sandbag scenes across different conditions: (top left) dust cloud and rocky environment; (top right) flat plains; (bottom left) dust and dirty sandbags; (bottom right) dirty sandbags on hilly terrain.

In our simulation pipeline, 2D instance segmentation masks are obtained directly from the renderer, providing pixel-accurate instance masks. However, in a real-world deployment, these masks must be generated using trained segmentation models. This highlights the value of a data set generation pipeline capable of producing large-scale labeled training data for downstream perception tasks. In practice, the rendered SynBag images and masks can be used to train a 2D instance segmentation network, such as a YOLO-based segmentation models [29], where the output can be used for pose estimation methods such as FoundationPose, as shown.

4. Dataset Description—SynBag 1.0

4.1. Overview and Design Motivation

Object pose estimation remains a central challenge in robotic perception, with modern approaches broadly categorized into three paradigms: instance-level, category-level, and unseen object pose estimation [30]. Instance-level methods rely on training data containing the exact 3D or CAD models of the objects to be recognized at inference time. These approaches achieve high precision when object geometry is known, but degrade when exposed to unseen objects or variations in texture. Category-level methods overcome this limitation by learning shared geometric and semantic representations across object categories, allowing the pose of novel instances (e.g., a different mug of the same class) to be inferred. Finally, unseen object pose estimation methods generalize beyond trained categories by leveraging shape priors or feature-based matching to estimate pose for entirely novel objects.

Given that our dataset includes three candidate regolith bag meshes (featureless, seamed, and folded-end variants), our approach aligns with the instance-level paradigm. These candidate meshes introduce progressively richer geometric features, allowing us to measure pose estimation performance as features become minimal. In doing so, the dataset targets low-texture object perception, a notoriously difficult task that is further complicated on the Moon by stark shadowing and the absence of atmospheric scattering. Each mesh is treated as a distinct known instance with fixed geometry, while environmental factors such as lighting, occlusion, and dust effects are varied to support robust instance-level training and benchmarking. A key objective of SynBag 1.0 is to empirically assess how mesh geometry and minimal visual features affect 6-DoF pose estimation performance; these results are expected to inform the final regolith containment unit design.

Several benchmark datasets have defined the state of instance-level pose estimation, including LINEMOD [31], LINEMOD-Occlusion [32], YCB-Video [33], and T-LESS [34]. These datasets provide annotated RGB-D imagery with known CAD models and ground-truth 6-DoF poses under varying levels of occlusion and lighting. More recent efforts, such as the BOP Challenge [28], standardize evaluation metrics for these datasets and serve as a benchmark for new methods. While these datasets have advanced pose estimation research in industrial and household settings, they are limited to Earth-like conditions with diffuse illumination and rigid objects. SynBag 1.0 extends this paradigm to the lunar domain by introducing photorealistic single-source illumination, surface dust occlusion, and progressive material degradation effects that replicate the harsh visual conditions of lunar construction. Future versions of the dataset will incorporate physically based low-gravity dynamics and plastic deformability to further enhance realism for grasping and manipulation research.

4.2. Dataset Structure and Scenarios

SynBag 1.0’s hierarchical structure was designed to ease interpretability for future users, making explicit the relationship between object geometry, environment, and scene configuration. At the top level, the dataset is divided into training and test splits, followed by subdivisions based on bag mesh geometry and geographic location in the lunar simulation. Each scene directory contains RGB images, depth maps, segmentation masks, and corresponding metadata and ground-truth pose annotations.

A single scene in SynBag corresponds to a fixed physical configuration of regolith bags within a lunar surface environment. Scene-level variation captures changes in object count, surface appearance, and dust effects, while image-level variation captures changes in viewpoint and illumination.

4.2.1. Hierarchical Organization

The dataset follows the structure split/mesh/location/scene. The mesh level groups scenes rendered with one of three candidate regolith bag geometries described in Section 3.3.2.

The location level represents three distinct lunar terrain configurations designed to probe background and surface-induced failure modes in pose estimation. These include (i) a flat terrain with minimal background structure, used to evaluate pose estimation performance under homogeneous and low-clutter conditions; (ii) a hilly terrain, where variations in surface slope and background elevation introduce changes in object orientation and cause the terrain to occupy different regions of the image as the camera orbits the target bag; and (iii) a terrain near a crater with surrounding rocks, which introduces irregular geometry, additional shadowing, and visually similar gray-scale structures in the background. Together, these locations enable evaluation of pose estimation and segmentation robustness as background complexity increases and as the distinction between object and environment becomes less pronounced.

Each scene directory contains per-sample sensor outputs and two metadata files: scene_gt.json (ground truth) and scene_meta.json (descriptive configuration).

The dataset contains the bag mesh files in .fbx format, for use in downstream 6-DoF pose estimation tasks, which require object CAD models.

4.2.2. Scene Scenarios (Object Count, Appearance, and Dust)

In the training split, scenes were generated with 1, 5, or 11 bags to represent increasing clutter and inter-object occlusion. Each scene designates a target bag, defined as the object around which the camera orbits during image capture. Ground-truth poses are provided for all instances in the scene.

Surface appearance was varied using a procedural staining algorithm as described in Section 3.4.2. Training scenes use three stain levels: clean, medium, and heavy, corresponding to 0, 30, and 90 stain seeds, respectively. Each stain configuration was rendered both with and without an active dust cloud. The dust cloud introduces partial occlusion and reduced contrast to emulate visual degradation expected during lunar construction.

The test split uses 8 bags per scene, and two stain levels: clean (0 seeds) and medium (15 seeds). The reduced stain parameterization in the test split provides an intermediate appearance condition while keeping the evaluation set compact.

4.2.3. Illumination and Viewpoint Sampling

Illumination variation is designed to reflect planetary surface operations, where the absence of an atmosphere produces long, high-contrast shadows under low solar elevation angles. At the lunar south pole, solar elevations are often only a few degrees above the horizon, resulting in extended shadowing and extreme photometric contrast that significantly impacts robotic perception [35,36].

In the training split, solar elevation angles of 5°, 8°, 12°, 18°, and 22° above the horizon are used. Two solar azimuth angles, 120° and 210°, are selected to produce distinct shadow profiles separated by approximately 90°.

For each scene, the camera orbits the target bag and captures 36 views in 10° azimuth increments, covering a full 360° orbit to sample diverse object viewpoints and relative camera-object poses. This orbit is repeated at camera heights of 20 cm, 50 cm, and 90 cm above the target bag in the training split.

In the test split, illumination and viewpoint parameters are fixed to a solar elevation of 30°, solar azimuth of 90°, and camera height of 100 cm above the target bag, supporting consistent zero-shot benchmarking under a held-out but physically plausible configuration.

While these predefined splits are useful for model training and evaluation, the dataset’s hierarchical organization allows future users to define alternative training, validation, and test splits based on mesh type, background geometry, or illumination conditions.

4.2.4. Data Formats

RGB images are stored as 8-bit PNG files for compatibility and storage efficiency. Depth is provided in two complementary representations: (i) a NumPy array storing metric depth in meters for learning-based pipelines, and (ii) a 16-bit PNG storing depth in millimeters for interoperability with pose-estimation inference frameworks that expect integer depth. Segmentation masks are stored as single-channel 8-bit PNG images encoding per-pixel instance identifiers.

4.2.5. Dataset Size

SynBag 1.0 contains 198 scenes in total: 162 training scenes and 36 test scenes. Each training scene contains 1080 samples, yielding 174,960 training samples. Each test scene contains 36 samples, yielding 1296 test samples. In total, SynBag 1.0 contains 176,256 samples, each comprising an RGB image, metric depth (NumPy and 16-bit PNG representations), and an instance segmentation mask, enabling multi-modal training and evaluation of 6-DoF object pose estimation in the lunar environment.

5. Results & Discussion

5.1. Dataset Verification via Downstream Task (Zero-Shot Benchmarking)

Rather than evaluating each annotation modality in isolation, we verify the internal consistency and downstream usability of SynBag 1.0 through a zero-shot 6-DoF pose estimation benchmark.

Successful end-to-end inference requires consistent RGB imagery, aligned depth measurements, correct instance segmentation masks, and accurate camera/object pose metadata. We therefore evaluate a state-of-the-art pose estimation pipeline on the held-out test split in unseen-object mode, where only the mesh is provided and no task-specific fine-tuning is performed.

We emphasize that this benchmark serves as a practical verification of dataset integrity and usability for pose estimation research within the synthetic setting, and does not replace real lunar-analog validation, which remains an important direction for future work.

5.2. Rigid-Body Approximation Impact

SynBag 1.0 models regolith-filled bags as rigid bodies to enable large-scale dataset generation and to isolate perception failure modes arising from lunar illumination, dust occlusion, and surface staining. This modeling choice is additionally informed by early design discussions with an industrial partner (MDA), which suggest that candidate construction bags are expected to be densely packed with regolith, resulting in limited large-scale shape deformation during typical handling and placement.

We nonetheless expect rigid modeling to be most limiting when (i) bags experience strong plastic collapse, (ii) grasps induce localized deformations, or (iii) contact results in non-rigid self-occlusions. In these cases, pose estimation methods relying on a single CAD geometry may experience increased rotational ambiguity and translation drift due to CAD-to-observed shape mismatch. We therefore position SynBag 1.0 as a benchmark for appearance- and environment-driven perception effects, and SynBag 2.0 as the extension targeting physics-driven deformation states via soft-body simulation.

5.3. Performance Evaluation of Pose Estimation Models

The performance of pose estimation is evaluated in the set of simulated environments introduced in the pose estimation benchmarking framework. These experiments span multiple variants of the sandbag mesh, placement locations, and environmental conditions, allowing for the analysis of how geometric complexity, terrain, and visual perturbations affect the accuracy of pose estimation.

For each configuration, a test set is constructed using a full orbital sweep of 36 viewpoints per scene. Each RGB frame is paired with its corresponding depth map and instance segmentation mask. Pose estimation is performed independently on each frame. Quantitative results are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Pose estimation performance across sandbag geometry, placement location, and environmental conditions.

Metrics

The Average Distance of Model Points (ADD) metric measures 6D pose estimation accuracy as the mean Euclidean distance between 3D model points transformed by the predicted pose and the same points transformed by the ground truth pose. While effective for objects with unique geometry, ADD is unsuitable for symmetric objects, as it penalizes rotationally equivalent poses.

To address this, the ADD-S (symmetric ADD) metric computes the distance from each predicted point to its nearest neighbor in the ground truth point cloud, explicitly accounting for object symmetries [30]. This makes ADD-S more appropriate for evaluating pose estimation performance on symmetric sandbags.

Alongside the mean ADD-S and translational error, recall at 10% and 20% ADD-S thresholds is used to quantify the fraction of poses whose ADD-S error falls below the corresponding percentage of the object diameter, which is approximately 400 mm depending on which model is selected.

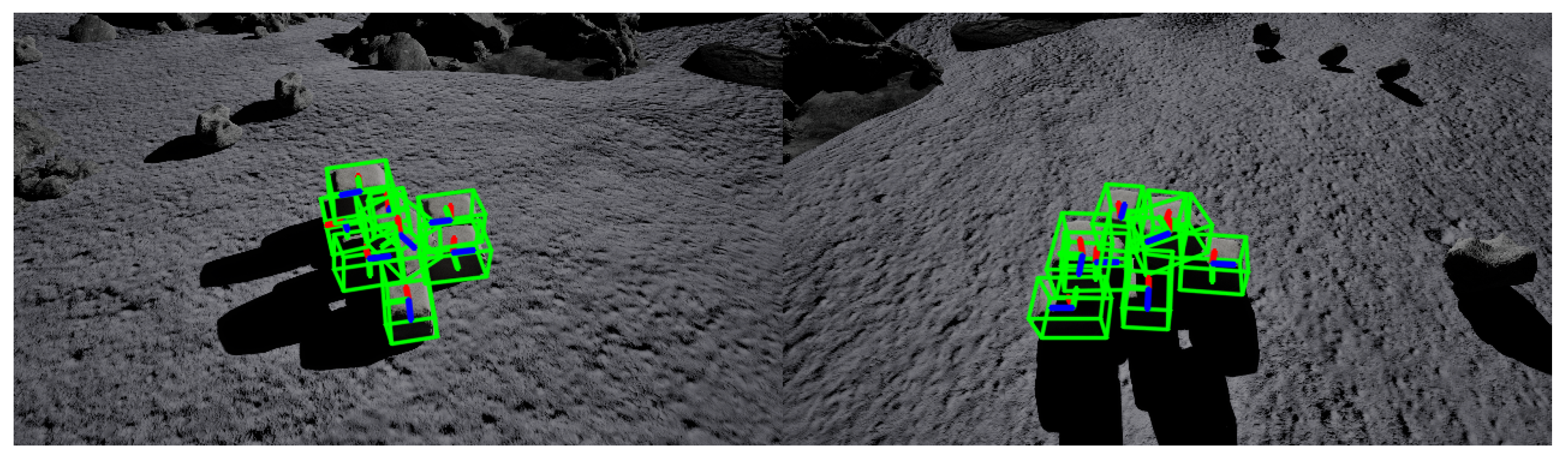

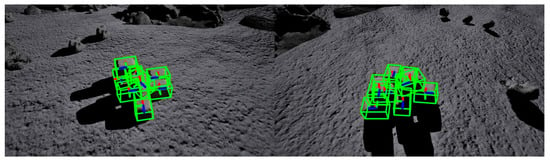

FoundationPose outputs a full 6D object pose for each detected instance, including rotation and translation in the camera frame. The visualization shown in Figure 10 indicates that the estimated poses closely align with the ground truth data.

Figure 10.

Pose estimation visualizations for eight instances of sandbag-03 in rocky terrain. Green wireframe boxes indicate the 3D object poses estimated by FoundationPose, while the red, green, and blue axes denote the object coordinate frame (X, Y, Z) and origin for each instance.

Quantitatively, results in Table 3 show strong performance across the diverse conditions. For the folded end sandbag (sandbag-03), over 90% of instances achieve successful pose estimates under the 20% ADD-S recall threshold. A small performance decrease is observed for the cuboid bags; however, the recall is still sufficiently high, indicating that reliable pose estimation is possible despite geometric simplicity. No significant performance differences are observed between clean and dirty sandbags or between dusty and clear environmental conditions, while scenes containing rocky terrain show a modest improvement in pose accuracy, likely due to increased depth context.

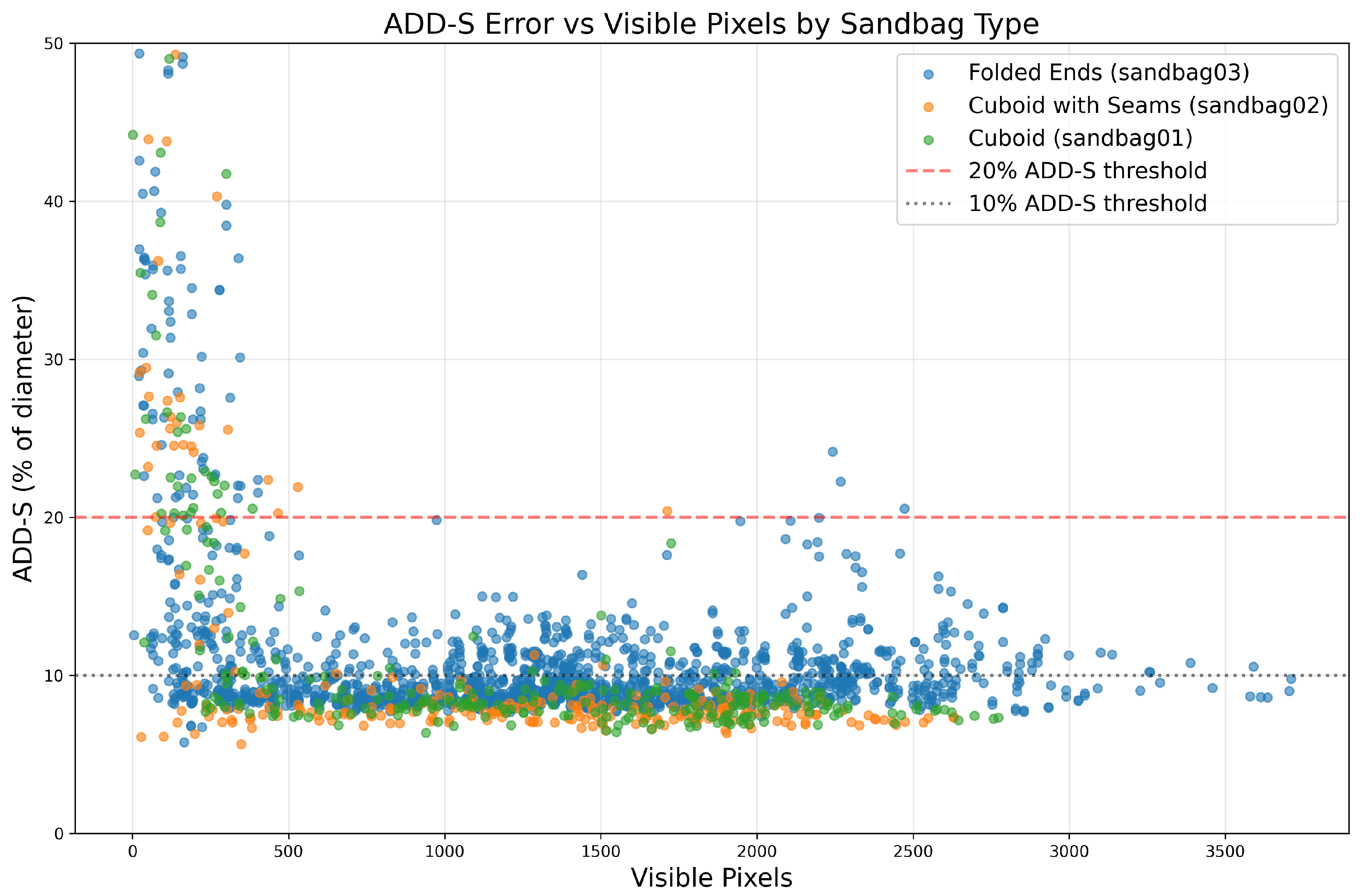

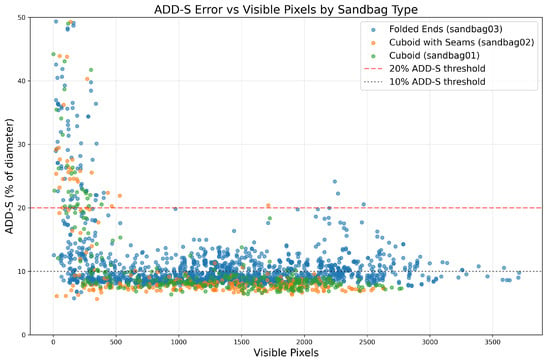

The number of visible pixels and the ADD-S error as a percentage of the object diameter are are summarized in Table 4 and plotted in Figure 11 to show the relationship between occlusion and performance. Sandbags that are more heavily occluded contain fewer pixels in their corresponding instance segmentation masks. Performance degrades for heavily occluded instances with fewer than 500 visible pixels, exhibiting higher ADD-S error and reduced recall, whereas pose accuracy improves and remains stable as object visibility increases.

Table 4.

Pose estimation performance as a function of visible pixel count per instance.

Figure 11.

Relationship between ADD-S error and visible pixel count across sandbag types, illustrating increased error and reduced recall under heavy occlusion.

6. Future Work

6.1. Plastic Deformability Integration: SynBag 2.0

SynBag 1.0 models all regolith bags as rigid bodies to enable scalable data generation and to isolate visual perception challenges arising from lunar lighting, dust, and surface degradation. An important extension of this work is the incorporation of plastic deformability to more faithfully capture the permanent shape changes exhibited by real regolith-filled construction bags during manipulation.

Future work will integrate the SOFA soft-body physics framework to model plastic deformation effects during grasping, lifting, and placement. Preliminary experiments with Unreal Engine’s Chaos Flesh system indicated that its deformable simulation is limited to elastic behavior, in which objects recover their original shape, making it unsuitable for representing permanent deformation. Ongoing integration between Unreal Engine and SOFA is expected to address this limitation and will form the basis of a subsequent dataset release, SynBag 2.0, featuring physically grounded deformation states for downstream perception and manipulation tasks.

6.2. Texture Deformation and Appearance Variation

As geometric deformability is introduced, future work will focus on updating texture maps to remain consistent with deformed sandbag geometry by including the addition of creases, folds, and indentations. Dirt and regolith accumulation will also be modeled more realistically, with contamination concentrated around grasp locations. Although initial results suggest pose estimation is robust to dirt accumulation, adding these appearance variations will generate a more diverse and realistic dataset to aim to improve model robustness and reduce the sim-to-real gap.

6.3. Interaction-Driven Surface Degradation

While the current approach enables visually realistic surface staining and supports large-scale dataset variation, it models appearance changes at the surface level only. Dirt accumulation is procedurally applied and does not explicitly account for physical contact events, force history, or regolith particle dynamics during manipulation. Future work will explore interaction-driven appearance modeling, where staining and material degradation are informed by contact mechanics and grasp interactions, enabling closer alignment between visual degradation and the physical processes encountered during grasping, placement, and repeated handling.

6.4. Physical Validation in Lunar-Analog Environments

While SynBag 1.0 focuses on synthetic data generation and benchmarking during early system design, an important next step is physical validation using real regolith construction units (RCUs) in controlled lunar-analog environments. As RCU designs mature and physical prototypes become available, future work will include capturing real imagery under single-source illumination, low-elevation lighting geometries, and regolith-dust interaction conditions representative of the lunar surface. These experiments will enable direct sim-to-real evaluation of pose estimation performance, including ADD-S error analysis and failure mode characterization, and will provide quantitative bounds on the transferability of synthetic training data to real lunar construction scenarios.

7. Conclusions

This paper introduced SynBag 1.0, a large-scale synthetic dataset for 6-DoF object pose estimation in lunar construction scenarios, generated using the MoonBot Studio framework. The dataset captures realistic illumination, dust occlusion, and surface variation expected in planetary environments, and its annotation consistency and usability were verified through zero-shot pose estimation on a representative subset. SynBag 1.0 provides a foundation for future research in lunar robotic perception and manipulation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.O.K. and K.A.M.; methodology, O.O.K. and M.A.; software, O.O.K., M.A. and I.R.H.; validation, O.O.K. and M.A.; formal analysis, O.O.K. and M.A.; investigation, O.O.K. and M.A.; resources, K.A.M.; data curation, O.O.K.; writing—original draft preparation, O.O.K., M.A. and I.R.H.; writing—review and editing, O.O.K. and K.A.M.; visualization, O.O.K., M.A. and I.R.H.; supervision, K.A.M.; project administration, O.O.K. and K.A.M.; funding acquisition, K.A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) (Grant No. ALLRP 592529-2023) and industrial partner MDA Space.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data in this work was generated using MoonBot Studio, a custom Unreal Engine 5–based simulation and dataset generation framework developed by our research group. MoonBot Studio enables large-scale photorealistic rendering of lunar environments with controllable lighting, camera placement, and object-level annotation for robotic perception research. The resulting dataset, SynBag 1.0, is archived at Federal Research Data Repository with title “SynBag v1.0: Pose estimation in the lunar environment” and DOI https://doi.org/10.20383/103.01606.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge MDA Space for providing the physical RCU material and early design mockups that informed the mesh modeling and texture design used in this study. The authors also acknowledge the ongoing collaboration and support of the Lunar BRIC partners throughout the course of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Paige, D.; Foote, M.; Greenhagen, B.; Schofield, J.; Calcutt, S.; Vasavada, A.; Preston, D.; Taylor, F.; Allen, C.; Snook, K.; et al. The Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Diviner Lunar Radiometer Experiment. Space Sci. Rev. 2009, 150, 125–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwadron, N.A.; Blake, J.B.; Case, A.W.; Joyce, C.J.; Kasper, J.; Mazur, J.; Petro, N.; Quinn, M.; Porter, J.A.; Smith, C.W.; et al. Does the worsening galactic cosmic radiation environment observed by CRaTER preclude future manned deep space exploration? Space Weather 2014, 12, 622–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiken, G.H.; Vaniman, D.T.; French, B.M. Lunar Sourcebook, A User’s Guide to the Moon; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Raj, A.T.; Qiu, J.; Vilvanathan, V.; Xu, Y.; Asphaug, E.; Thangavelautham, J. Systems Engineering of Using Sandbags for Site Preparation and Shelter Design for a Modular Lunar Base. In Proceedings of the Earth and Space 2022: Space Exploration, Utilization, Engineering, and Construction in Extreme Environments; Dreyer, C.B., Littel, J., Eds.; American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleymani, T.; Trianni, V.; Bonani, M.; Mondada, F.; Dorigo, M. Bio-inspired construction with mobile robots and compliant pockets. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2015, 74, 340–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardiny, H.; Witwicki, S.; Mondada, F. Are Autonomous Mobile Robots Able to Take Over Construction? A Review. Int. J. Robot. Theory Appl. 2015, 4, 10–21. [Google Scholar]

- Kodikara, G.R.L.; McHenry, L.J. Machine learning approaches for classifying lunar soils. Icarus 2020, 345, 113719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shkuratov, Y.G.; Bondarenko, N.V. Regolith Layer Thickness Mapping of the Moon by Radar and Optical Data. Icarus 2001, 149, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, J.; Corrales Ramon, J.A.; Bouzgarrou, B.C.; Mezouar, Y. Robotic Manipulation and Sensing of Deformable Objects in Domestic and Industrial Applications: A Survey. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2018, 37, 688–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Jayakumari, A.; Richter, F.; Li, Y.; Yip, M.C. SuPer Deep: A Surgical Perception Framework for Robotic Tissue Manipulation using Deep Learning for Feature Extraction. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Xi’an, China, 30 May–5 June 2021; pp. 4783–4789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; Yue, Z.; Gou, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, G.; Shi, K.; Zhang, X.; Yang, B. Structure and Formation Mechanism of Lunar Regolith. Space Sci. Technol. 2025, 5, 0219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Varava, A.; Kragic, D. Modeling, learning, perception, and control methods for deformable object manipulation. Sci. Robot. 2021, 6, eabd8803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bousmalis, K.; Irpan, A.; Wohlhart, P.; Bai, Y.; Kelcey, M.; Kalakrishnan, M.; Downs, L.; Ibarz, J.; Pastor, P.; Konolige, K.; et al. Using Simulation and Domain Adaptation to Improve Efficiency of Deep Robotic Grasping. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Brisbane, QLD, Australia, 21–25 May 2018; pp. 4243–4250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahani, A.; Voghoei, S.; Rasheed, K.; Arabnia, H. A Brief Review of Domain Adaptation. In Advances in Data Science and Information Engineering; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 877–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, J.; To, T.; Sundaralingam, B. Falling Things: A Synthetic Dataset for 3D Object Detection and Pose Estimation. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, R.; Liu, J.; Van Wyk, K.; Chao, Y.W.; Lafleche, J.F.; Shkurti, F.; Ratliff, N.; Handa, A. Synthetica: Large-Scale Synthetic Data Generation for Robot Perception. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.21153. [Google Scholar]

- Richard, A.; Kamohara, J.; Uno, K.; Santra, S.; van der Meer, D.; Olivares-Mendez, M.; Yoshida, K. OmniLRS: A Photorealistic Simulator for Lunar Robotics. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Yokohama, Japan, 13–17 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bingham, L.; Kincaid, J.; Weno, B.; Davis, N.; Paddock, E.; Foreman, C. Digital Lunar Exploration Sites Unreal Simulation Tool (DUST). In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Aerospace Conference, Big Sky, MT, USA, 4–11 March 2023; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieczyński, D.; Ptak, B.; Kraft, M.; Drapikowski, P. LunarSim: Lunar Rover Simulator Focused on High Visual Fidelity and ROS 2 Integration for Advanced Computer Vision Algorithm Development. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 12401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, M.; Wong, U.; Furlong, P.M.; Rogg, A.; McMichael, S.; Welsh, T.; Chen, I.; Peters, S.; Gerkey, B.; Quigley, M.; et al. Planetary Rover Simulation for Lunar Exploration Missions. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Aerospace Conference, Big Sky, MT, USA, 2–9 March 2019; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T. UnrealVision: A Synthetic Dataset Generator for Human-Pose Estimation and Behavior Analysis. Master’s Thesis, San José State University, San José, CA, USA, 2024. Master’s Theses No. 5597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawal, P.; Sompura, M.; Hintze, W. Synthetic Data Generation for Bridging the Sim2Real Gap in a Production Environment. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2311.11039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, M.K.; Mazarico, E.; Neumann, G.A.; Zuber, M.T.; Haruyama, J.; Smith, D.E. A new lunar digital elevation model from the Lunar Orbiter Laser Altimeter and SELENE Terrain Camera. Icarus 2016, 273, 346–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khademian, Z.; Kim, E.; Nakagawa, M. Simulation of Lunar Soil with Irregularly Shaped, Crushable Grains: Effects of Grain Shapes on the Mechanical Behaviors. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2019, 124, 1157–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperling, F.B. Basic and Mechanical Properties of the Lunar Soil Estimated from Surveyor Touchdown Data; Contractor Report NASA–CR–109410/JPL–TM–33-443 70N23459; Contract NAS7-100; Acquisition ID 19700014154; Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology: Pasadena, CA, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Risecode. Splash Texture Pack. Fab (Epic Games) Digital Asset Listing. Description: 26 Splash Textures at 4096×4096 Resolution. Available online: https://www.fab.com/listings/29836b11-24ea-47f9-8508-3b0f310576bb (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Wen, B.; Yang, W.; Kautz, J.; Birchfield, S. FoundationPose: Unified 6D Pose Estimation and Tracking of Novel Objects. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2312.08344. [Google Scholar]

- Hodaň, T.; Sundermeyer, M.; Drost, B.; Labbé, Y.; Brachmann, E.; Michel, F.; Rother, C.; Matas, J. BOP Challenge 2020 on 6D Object Localization. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2020 Workshops; Bartoli, A., Fusiello, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 577–594. [Google Scholar]

- Ultralytics. Ultralytics YOLO Segmentation. Technical Documentation Describing YOLO-Based Instance Segmentation Models, Training Procedures, and Inference Pipelines. 2025. Available online: https://docs.ultralytics.com/tasks/segment/ (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Wang, P. Deep Learning-Based Object Pose Estimation: A Comprehensive Survey. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2026, 134, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinterstoisser, S.; Lepetit, V.; Ilic, S.; Holzer, S.; Bradski, G.; Konolige, K.; Navab, N. Model Based Training, Detection and Pose Estimation of Texture-Less 3D Objects in Heavily Cluttered Scenes. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ACCV 2012; Lee, K.M., Matsushita, Y., Rehg, J.M., Hu, Z., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 548–562. [Google Scholar]

- Brachmann, E.; Krull, A.; Michel, F.; Gumhold, S.; Shotton, J.; Rother, C. Learning 6D Object Pose Estimation Using 3D Object Coordinates. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2014; Fleet, D., Pajdla, T., Schiele, B., Tuytelaars, T., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 536–551. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, Y.; Schmidt, T.; Narayanan, V.; Fox, D. PoseCNN: A Convolutional Neural Network for 6D Object Pose Estimation in Cluttered Scenes. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1711.00199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodaň, T.; Haluza, P.; Obdržálek, Š.; Matas, J.; Lourakis, M.; Zabulis, X. T-LESS: An RGB-D Dataset for 6D Pose Estimation of Texture-Less Objects. In Proceedings of the IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Santa Rosa, CA, USA, 24–31 March 2017; pp. 880–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litaker, H.L.J.; Beaton, K.H.; Bekdash, O.S.; Crues, E.Z.; Paddock, E.J.; Rohde, B.A.J.; Reagan, M.L.; Van Velson, C.M.; Everett, S.F. South Pole Lunar Lighting Studies for Driving Exploration on the Lunar Surface. In Proceedings of the 46th International IEEE Aerospace Conference, Big Sky, MT, USA, 1–8 March 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Gläser, P.; Scholten, F.; De Rosa, D.; Marco Figuera, R.; Oberst, J.; Mazarico, E.; Neumann, G.A.; Robinson, M.S. Illumination conditions at the lunar south pole using high resolution digital terrain models from LOLA. Icarus 2014, 243, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.